Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Identification and Control of Fungi Associated With The Post-Harvest Rot of Solenostemon Rotundifolius (Poir) J.K. Morton in Adamawa State of Nigeria.

Enviado por

Alexander DeckerTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Identification and Control of Fungi Associated With The Post-Harvest Rot of Solenostemon Rotundifolius (Poir) J.K. Morton in Adamawa State of Nigeria.

Enviado por

Alexander DeckerDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare ISSN 2224-3208 208 (Paper) ISSN 2225-093X 2225 (Online) Vol.3, No.

5, 2013

www.iiste.org

Identification and control of Fungi associated with the post-harvest post rot of Solenostemon rotundifolius (Poir)J.K. Morton in Adamawa State of Nigeria.

Aisha Mohammed1 Ishaku Bajon Chimbekujwo2*and Basiri Bristone2 1.Department Department of Biological Sciences, Federal College of Education, Education, Adamawa State. 2.Department Department of Plant Sciences, Modibbo Adama University of Technology, P.M.B. 2076, Yola, Adamawa State; Nigeria. *Chimbe2007@yahoo.com Abstract Investigation into the fungi associated with the post-harvest rot of Solenostemon rotundifolius (Poir).J.K.Morton, Hausa Potato was carried out in the teaching and research laboratory of the Department of Biological sciences of the University. Completely Randomized Design (CRD) was used and the data obtained were analyzed using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and the means that were significant were separated using the Least Significant Difference (LSD). Four fungi Aspergillus niger, Fusarium oxysporum, Penicillum expansum and Rhizopus stolonifer were consistently onsistently isolated identified in pure cultures from the diseased tubers collected from the two markets in Yola. Mean percentage incidence showed that A. niger was the most prevalent with 19.69% followed by F. oxysporum 16.47%, R. stolonifer 14.38% and P. expansum 12.81%. The efficacy of Wood ash, saw dust and guinea corn chaff as control material against fungal rot development was used. The three plant materials reduced the rot caused by the three organisms. Key words: Solenostemon rotundifolius, Aspergi Aspergillus llus niger, Fusarium oxysporum, Penicillium expansum and Rhizopus stolonifer. 1. Introduction Hausa potato [Solenostemon rotundifolius (Poir.)] J. K. Morton, (Hausa name-Tumuku), a root tuber and a dicotyledonous annual herb belonging to the family Labiaceae (Schippers, 2002), originated from tropical Africa (Tindall, 1983). It is currently cultivated in many African countries (Ghana and Nigeria) as a supplement in family menus (Jada et al., 2007). The plant grows on well drained loamy or sandy loam soil and on ridges (Schippers, 2002), producing tubers (Blench, 1997) that contain 75% water, 1.4% protein, 0.5% fat, 21% carbohydrate, 0.1% fibre, 1% ash, 17mg calcium, 6 mg iron, 0.05 mg thiamine, 0.02 mg riboflavin, 1 mg niacin, 1 mg ascorbic acid (Grubben and Denton, enton, 2004). They are boiled, baked, fried or roasted and eaten as snack or cooked with spices in various combinations with other foods such as beans and cook vegetables (Grubben and Denton, 2004). The most serious causes of post-harvest harvest loss in tropical tropical root crops are pests and diseases due to fungi (FAO,1990) and as a result of harvesting and post - harvest handling techniques ( Mustapha and Yahya, 2006) with resultant 10 10-30% reduction in tuber quality (Muktar and Abdullahi, 2004, Kehinde and Kadiri 20 2006 and Basiri et al., 2011). Infection of the tubers present economic loss associated with discoloration on the crops, change in flavour, thereby giving off unpleasant odour (Cockerell et al. 1971) and production mycotoxins harmful to human and livestock (Oguntade ( and Adekunle, 2010). Although the use of synthetic fungicides have been proved effective in controlling some phytopathogens, chemical control leads to environmental hazards associated with high cost and inaccessibility to indigenous farmers (Ebele, le, 2011). Ijato (2011) reported that plant parts, powders of plant parts, ash, aqueous extracts which are environmentally non-hazardous, hazardous, locally available and can be cheaply maintained are suitable alternatives to the expensive synthetic fungicides. Mann (2012) reported the control of infectious diseases using Anogeissus leiocarpus and Terminalia avicenniodes. This paper is aimed at identification and control of the fungi associated with the post-harvest rot of Solenostemon rotundifolius.

136

Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare ISSN 2224-3208 208 (Paper) ISSN 2225-093X 2225 (Online) Vol.3, No.5, 2013

www.iiste.org

2. Materials and Methods 2.1 Collection of Samples A total of three thousand and two hundred (1200) samples of Solenostemon rotundifolius (both healthy and diseased) were collected from Yola town and Jimeta markets of Adamawa state. Located between latitude 911 to 919N and longitude 1220 to 1230E. Samples of Solenostemon rotundifolius tubers were collected from different selling points randomly in the markets. Both wounded and non-wounded non wounded ones were taken to the laboratory for studies. The diseased tubers s were incubated in sterilized desiccators for the development of rot. Sixteen medium medium-sized clay pots (25x20x19cm) were purchased from Yola market for the storage of the tubers. 2.2 Collection and Preparation of plant materials Guinea corn (Sorghum bicolor) chaff was purchased from Yola market, sawdust was obtained free from a carpenter at Jimeta and wood ash was obtained from domestic burnt wood of Anogeissus leiocarpus. Five hundred grammes of each of the plant materials in four replicates were placed in into to sterile polythene bags and taken to the laboratory. 2.3 Isolation and Identification of Fungi Portion of the diseased tubers of Solenostemon rotundifolius was cut into small pieces into sterile Petri dishes with a sterile scissors which was flamed over and dipped inside methylated spirit (Thomas, 1979). The cut pieces were surface sterilized with 0.01% mercuric chloride for 30 seconds and rinsed in five changes of sterile distilled water and blotted dry with sterile Whatman No. 1 filter papers. Cut piec pieces es were plated aseptically in 9 cm2 Petri dishes containing solidified potato dextrose agar (PDA). Solidified plates were incubated at room temperature (2830 (28 oC) for 4 days. Fungal colonies that grew from the incubated plates were similarly sub-cultured sub cultured on fresh PDA plates and incubated at 2830oC for 4 days until pure cultures were obtained. 2.4 Identification of Isolated Fungi Microscopic examination was carried out after examining the colony characteristics (Frazier, 1978), while the morphological and cultural characteristics were observed under the microscope and compared with the structures in Alexopoulus and Mius (1986) and Snowdon (1990). 2.5 Pathogenicity Tests Healthy Solenostemon rotundifolius tubers were inoculated with pure cultures of the isolates iso after being surface sterilized with 0.01% HgCl2 for one minute and washed in five changes of sterile distilled water. A 2mm diameter cork borer was driven to a depth of about 2mm into the healthy tubers and the bored tissue removed. Then 2mm diameter disc of the culture was cut and placed in the hole and the removed tissue was put back in place. The wound was sealed with sterile vesper prepared from wax and Vaseline. The control was set up in the same manner except that sterile agar was used instead of the isolate. For each isolate four tubers of Solenostemon rotundifolius were inoculated and four controls were set up. The inoculated tubers were placed in desiccators and incubated at 30oC under aseptic conditions as adopted by Chimbekujwo (1994) and Basiri B et al. (2011). Regular observations were made and isolation of any pathogenic organism was done for comparison with the original isolates. All experiments were conducted in the laboratory using Completely Randomized Design (CRD) as described by Gomez Gome and Gomez (1984). All the experiments were replicated four times. Data collected were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA), while the means that were significant were separated by least significant difference (LSD) at 1% probability level (P<0.01). 2.6 Assessing the efficacy of guinea corn chaff, saw dust, and wood ash in the control of Solenostemon rotundifolius tuber rot. Eighty healthy hausa potato tubers were placed in 25 cm diameter clay pots , labeled as A,B,C and D after being surface sterilized with 0.01% HgCl2 for one minute, washed in five changes of sterile distilled water and left to dry. Tubers in A were covered with guinea corn chaff, B with saw dust, C with wood ash and D served as control (untreated). Five hundred grammes of each o of f the treatment material were used and all the pots were arranged in a completely randomized design with four replications at room temperature. One tuber from each of the experimental pots was randomly selected and inoculated with one of the fungal isolates. isolates. Disease incidence (%) of Solenostemon rotundifolius was determined after four months of storage at room temperature using the formula as described by Tarr (1981). Disease incidence = number of diseased samples total number of samples examined x10 x100 Results

3.

137

Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare ISSN 2224-3208 208 (Paper) ISSN 2225-093X 2225 (Online) Vol.3, No.5, 2013

www.iiste.org

The fungi isolated from diseased tubers of Solenostemon rotundifolius were identified as Aspergillus niger, Fusarium oxysporum, Penicillium expansum and Rhizopus stolonifer. Aspergillus niger was found to be responsible for about 19.69% of rots s observed, followed by Fusarium oxysporum, 16.47%, Rhizopus stolonifer 14.38% and Penicillium expansum 12.81% (Table 1). Pathogenicity tests of the isolates revealed that A. niger, F. oxysporum, P. expansum and R. stolonifer caused rot as inoculated hausa hausa potato tubers developed rot symptoms similar to natural diseased tubers. A. niger had the highest mean rot diameter of 22.35mm while P. expansum had the lowest 15.25mm (Table 2). The preservatives (guinea corn chaff, saw dust, and wood ash) significantly significantly (P<0.01) controlled rot of the inoculated Solenostemon rotundifolius tubers compared to the control (Table 3). The highest disease incidence of 7.81% was recorded in the control, while the lowest incidence of 1.56% was recorded in tubers treated with wood wo ash, which also has remarkable reduced effects of the incidence of Penicillium expansum, and Rhizopus stolonifer. However, Aspergillus niger appeared to be less sensitive to the preservatives compared to the other fungal pathogens. 4. Discussion The results sults of the study showed that four fungi viz; Aspergillus niger, Fusarium oxysporum, Penicillium expansum and Rhizopus stolonifer, were isolated from infected Solenostemon rotundifolius tubers in the study area. Out of these, A. niger was responsible for about 19.69% of rots observed, the least was P. expansum 12.81%. Muktar and Abdullahi (2004) and Umar et al. (2010) who studied the prevalence of A. niger from Irish potatoes and maize seeds respectively reported the same result. The identified isolates have have been found as common post-harvest post fungi (Mustapha and Yahya, 2006, Naureen et al., 2009 and Ebele, 2011) and earlier reported to be responsible for rot of many root and tuber crops in Nigeria (Oduro et al., 1990). The significant reduction in disease incidence in observed in the tubers inoculated with the fungal isolates and treated with the different preservatives may be due to inhibitory effects on the fungi which might have caused reduction in the mycelial growth of the isolates. 5. Conclusion The findings ings of this study have shown that Aspergillus niger, Fusarium oxysporum, Penicillium expansum and Rhizopus stolonifer were responsible for the rot of Solenostemon rotundifolius tubers. Saw dust and wood ash which have fungicidal properties are good mediums mediu for storing Solenostemon rotundifolius tubers and serve as alternative methods of reducing human exposure to toxins produced by pathogens such as mycotoxins, aflatoxins thus minimizing post-harvest harvest losses. 6. References Alexopoulus, C.I. and Mius C.W. (1986). An Introductory Mycology (Revised edition) New York, John Wiley and Sans, Pp204-340. Basiri, B., Chimbekujwo, I. B. and Pukuma, M. S. (2011). Control of Post Harvest Fungal Rot of Sweet Potato [Ipomoea batatas (Linn.) Lam.] In Yola, Adamawa State of Nigeria. Biological and Environmental Sciences Journal for the Tropics. 8 (1): 129-132. 132. Blench, R.M. (1997). A Neglected Species, Livelihoods and Biodiversity in Difficult Areas: How should the Public Sector Respond. National Resources Bricking Paper 25. London Over Seas Development Institute. Pp2. Chimbekujwo, I. B. (1994). Two Post Harvest Fungal Infections of Carica papaya L. Fruits in Ibadan. Journal of Technology and Development 4:21-29. 4:21 Cockerell, I.B., Francis, B. and Haliday, D. (1971). Change Change in Nutritive value of concentrated Feeding stuff during Storage. Proc. Centre Govt. Dev. Feed Resources pp181 192. Ebele, M.L. (2011). Evaluation of Some Aqueous Plant Extracts Used in the Control of Pawpaw Fruit (Carica papaya L.) Rot Fungi. Journal al of Applied Biosciences. 37:2419-2424. Food and Agricultural Organisation (1990). Storage and Processing of Roots and Tubers in the Tropics. Francais Frazier, W. C. (1978). Food Microbiology, USA, Tata Mcgraw Hill Co. Inc. pp.20-40. Frazier, W. C. (1978). Food Microbiology, USA, Tata Mcgraw Hill Co. inc. pp.20-40 Gomez, K. A. and Gomez, A.A. (1984). Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research 2nd Edition John Wiley and Sons. Pp 680. Grubben, G. J. H. and Denton, O. A. (2004). Plant Resources of Tropical Africa 2, Vegetables, Prota Foundation, Wageningen, Netherlands Back Huys. Publishers, leiden, Netherlands/CTA. Wageningen Netherlands. Pp.668. Ijato, J.Y. (2011). Inhibitory Effects of Indigenous Plant Extracts (Zingiber officinale and Ocimum gratissimum)

138

Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare ISSN 2224-3208 208 (Paper) ISSN 2225-093X 2225 (Online) Vol.3, No.5, 2013

www.iiste.org

on Post- Harvest yam (Dioscorea rotundata Poir.) rot, in vitro. Journal of American Science. 7(1):43-47. Jada, M. Y., Bello, D., Leuro, J. and Jakusko, B. B. (2007). Responses of some Hausa potato Solenostemon rotcardifollices (Poir. J.K. Morton) orton) Cultivars to Root-knot Root Nematode Meloidogyne javanica (Treub) Chitwood in Nigeria. International Journal of Agriculture and Biology. 9 (4):665-668. Kehinde, I.A. and Kadiri, M. (2006). Post PostHarvest Spoilage Fungi of Sweet Potato.Biological and Environmental ironmental Sciences Journal for the Tropics 3(2):158-159. Mann, A. (2012). Evaluation of Antimicrobial Activity of Anogeissus leiocarpus and Terminalia avicennioides against Infectious Diseases Prevalent in Hospital Environments in Niger. Journal of Microbiology Micr Research. 2(1): 6-10. Mukhtar, M. D. and Abdullahi, A. F. (2004). A Study on the Predominant Spoilage Fungi in Irish Potato Sold at Yankaba and Rimi Markets in Kano Metropolis. Biological and Environmental Sciences Journal for the Tropics. 1(1): 51-58. Mustapha, Y. and Yahaya, S. M. (2006). Isolation and Identification of Post Post-Harvest Harvest Fungi Associated with Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) and Pepper (Capsicum annum) Samples from some Selected Irrigation Sites in Kano State. Biological and Envi Environmental Sciences Journal for the Tropics 3 (3): 139-141. Naureen, F., Batool, H., Sultana, V., Ara, J., Syed, E. (2009). Prevalence of Post Post-Harvest Harvest Rot of Vegetables and Fruits in Karachi. Pakistan Journal of Botany 41(6): 3185-3190 Oduro, K. A., Adimora, ra, L. O. and Ubani, C. (1990). Prospects for Traditional and Cultural Practices in Integrated Pest Management of Some Root Crop Disease in River State, Nigeria. In S.K Halu and E.E. Caveness (eds) Integrated Pest Management for Tropical Root Tuber Crops Pp 185-187. Oguntade, T. O. and Adekunle, A.A. (2010). Preservation of Seeds against Fungi using Wood Wood- ash of some Tropical Forest Trees in Nigeria. African Journal of Microbiology Research 4(4):279-288. Schippers, R. (2002). African Indigenous Vegetables. Vegetables. An over view of the cultivated Species Ayles Ford. Nr international pp214. Snowdon, A.C. (1990). A Colour Atlas of Post-Harvest Post Harvest Diseases and Disorders of Fruits and Vegetables. Cambridge University Press. Pp. 128-140. Tarr, S.A.W. (1981). The Principles les of Plant Pathology. London; Macmillan Press. 632pp. Thomas, G.A. (1979). Medical Microbiology. London; Macmillan Publishers pp 403. Tindall, H.D. (1983). Vegetables in the Tropics. London The Macimillan Press. LTD. Pp. 508508 511. Umar, R. A.; Mohammed, S. Mohammed, B. and Usman, A. (2010). Nutrient composition of the leaves of calabash (Lagenaria siceraria). Biological and Environmental Sciences Journal for Tropics 7(3): 88-92.

139

Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare ISSN 2224-3208 208 (Paper) ISSN 2225-093X 2225 (Online) Vol.3, No.5, 2013

www.iiste.org

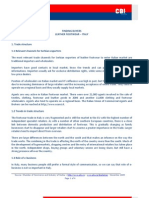

Table 1: Percentage Incidence of Solenostemon rotundifolius Tuber Rot from m two Markets in Yola Organisms isolated Percentage Incidence of Isolation Yola Town Market Jimeta Market Total Isolation Aspergillus niger 350 (10.94%) 280 (8.75%) 8.75%) 19.69% 275 (8.59%) 252 (7.88%) 16.47% Fusarium oxysporum Penicillium expansum 210 (6.56%) 200 (6.25%) 12.81% Rhizopus stolonifer 240 (7.50%) 220 (6.88%) 14.38% Non- infected 573(17.91%) 600 (18.75%) 36.66 %

Totals

1648 (51.50 %)

1552 (48.51 %)

100.00%

Table: 2 Pathogenicity Test Showing rot Development of Solenostemon rotundifolius Tubers Incubated Incuba at 300C Isolated fungi Mean diameter of rot (mm) Aspergillus niger 22.35 Fusarium oxysporum 21.50 Penicillium expansum 15.25 Rhizopus stolonifer 18.02 Control 0.00 Table 3: Mean rot percentage on Inoculated Solenostemon rotundifolius tubers for four months storage period. Treatment Aspergillus Fusarium Penicillium Rhizopus niger oxysporum expansum stolonifer Saw dust 4.14 3.43 2.19 3.51 Guinea corn chaff 5.62 4.76 3.43 4.06 Wood ash 3.17 2.26 1.56 1.87 Control 7.81 5.93 4.06 5.93 Mean 5.18 4.10 2.81 3.84 Pro. F 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 SE 1.53 1.28 0.80 1.26 LSD 0.87 0.80 0.63 0.79

140

This academic article was published by The International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE). The IISTE is a pioneer in the Open Access Publishing service based in the U.S. and Europe. The aim of the institute is Accelerating Global Knowledge Sharing. More information about the publisher can be found in the IISTEs homepage: http://www.iiste.org CALL FOR PAPERS The IISTE is currently hosting more than 30 peer-reviewed academic journals and collaborating with academic institutions around the world. Theres no deadline for submission. Prospective authors of IISTE journals can find the submission instruction on the following page: http://www.iiste.org/Journals/ The IISTE editorial team promises to the review and publish all the qualified submissions in a fast manner. All the journals articles are available online to the readers all over the world without financial, legal, or technical barriers other than those inseparable from gaining access to the internet itself. Printed version of the journals is also available upon request of readers and authors. IISTE Knowledge Sharing Partners EBSCO, Index Copernicus, Ulrich's Periodicals Directory, JournalTOCS, PKP Open Archives Harvester, Bielefeld Academic Search Engine, Elektronische Zeitschriftenbibliothek EZB, Open J-Gate, OCLC WorldCat, Universe Digtial Library , NewJour, Google Scholar

Você também pode gostar

- Sources of Microbial Contamination in TC LabDocumento6 páginasSources of Microbial Contamination in TC LabLau Shin YeeAinda não há avaliações

- Management of Root-Knot Nematodes (Meloidogyne Spp) on Tomato using Antagonistic PlantsDocumento5 páginasManagement of Root-Knot Nematodes (Meloidogyne Spp) on Tomato using Antagonistic PlantsTesleem BelloAinda não há avaliações

- Effect Aqueous Extract of Xanthium Strumarium L Andtrichoderma Viride Against Rhizctonia SolaniDocumento6 páginasEffect Aqueous Extract of Xanthium Strumarium L Andtrichoderma Viride Against Rhizctonia SolaniTJPRC PublicationsAinda não há avaliações

- Isolation, Identification and Characterization of Phyllosphere Fungi From VegetablesDocumento6 páginasIsolation, Identification and Characterization of Phyllosphere Fungi From VegetablesInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyAinda não há avaliações

- M.Razia and S.SivaramakrishnanDocumento7 páginasM.Razia and S.SivaramakrishnanAli GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- Bacterial control of pathogenic fungi from wild plantsDocumento10 páginasBacterial control of pathogenic fungi from wild plantsJawad Khan KakarAinda não há avaliações

- Plant extracts inhibit yam rot fungiDocumento5 páginasPlant extracts inhibit yam rot fungiFrancis SurveyorAinda não há avaliações

- Food Control: Nuhu Bala Adamu, James Yazah Adamu, Dauda MohammedDocumento4 páginasFood Control: Nuhu Bala Adamu, James Yazah Adamu, Dauda MohammedNur Afiqah ZaidiAinda não há avaliações

- Pinot Et Al-2011-Journal of Applied MicrobiologyDocumento9 páginasPinot Et Al-2011-Journal of Applied Microbiologydr Alex stanAinda não há avaliações

- Preliminary Study of Endophytic Fungi in Timothy (Phleum Pratense) in EstoniaDocumento9 páginasPreliminary Study of Endophytic Fungi in Timothy (Phleum Pratense) in EstoniaBellis KullmanAinda não há avaliações

- Identification of Fungal Pathogens Causing Spoilage of Oranges in KanoDocumento3 páginasIdentification of Fungal Pathogens Causing Spoilage of Oranges in KanohughAinda não há avaliações

- Screening of Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Secondary Metabolites From Endophytic Fungi Isolated From Wheat (Triticum Durum)Documento9 páginasScreening of Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Secondary Metabolites From Endophytic Fungi Isolated From Wheat (Triticum Durum)Hiranda WildayaniAinda não há avaliações

- Merging Biotechnology With Biological Control: Banana Musa Tissue Culture Plants Enhanced by Endophytic FungiDocumento7 páginasMerging Biotechnology With Biological Control: Banana Musa Tissue Culture Plants Enhanced by Endophytic FungiAkash DoiphodeAinda não há avaliações

- Evaluation of Some Indigenous Plant Extracts Against Pulse Beetle, Callosobruchus Chinensis L. (Bruchidae: Coleoptera) in Stored Green Gram Vigna Radiata L.)Documento9 páginasEvaluation of Some Indigenous Plant Extracts Against Pulse Beetle, Callosobruchus Chinensis L. (Bruchidae: Coleoptera) in Stored Green Gram Vigna Radiata L.)Md Abdul AhadAinda não há avaliações

- Effect of Seed Treatment On Seedling Health of Chili: M. Z. Alam, I. Hamim, M. A. Ali, and M. AshrafuzzamanDocumento5 páginasEffect of Seed Treatment On Seedling Health of Chili: M. Z. Alam, I. Hamim, M. A. Ali, and M. Ashrafuzzamanyasir majeedAinda não há avaliações

- Some in Vitro Observations On The Biological Control of Sclerotium Rolfsii, A Serious Pathogen of Various Agricultural Crop PlantsDocumento8 páginasSome in Vitro Observations On The Biological Control of Sclerotium Rolfsii, A Serious Pathogen of Various Agricultural Crop PlantsInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- tmp38B1 TMPDocumento15 páginastmp38B1 TMPFrontiersAinda não há avaliações

- Isolation and Characterization of Fungi Associated With Spoiled TomatoesDocumento5 páginasIsolation and Characterization of Fungi Associated With Spoiled TomatoesJimoh JamalAinda não há avaliações

- 6.new Pyran of An Endophytic Fungus Fusarium Sp. Isolated BrotowaliDocumento7 páginas6.new Pyran of An Endophytic Fungus Fusarium Sp. Isolated BrotowaliBritish PropolisAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal Mikro 2Documento5 páginasJurnal Mikro 2Juju JuntakAinda não há avaliações

- Biology of LifeDocumento7 páginasBiology of LifeDrizzy MarkAinda não há avaliações

- 278Documento4 páginas278Amelia_KharismayantiAinda não há avaliações

- Toppo and Nail 2015Documento9 páginasToppo and Nail 2015Alan Rivera IbarraAinda não há avaliações

- E 0242024Documento5 páginasE 0242024International Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Diversidad de Hongos Que Destruyen Nematodos en Taita Taveta, KeniaDocumento6 páginasDiversidad de Hongos Que Destruyen Nematodos en Taita Taveta, KeniaPaola LopezAinda não há avaliações

- Trametesss PDFDocumento11 páginasTrametesss PDFwardah arumsariAinda não há avaliações

- Agent Biology-The Potency of Endofit Fungi in Cocoa AsDocumento6 páginasAgent Biology-The Potency of Endofit Fungi in Cocoa Asglenzi fizulmiAinda não há avaliações

- 5 PDFDocumento8 páginas5 PDFRobertAinda não há avaliações

- Fungal Isolates of Groundnut SeedsDocumento14 páginasFungal Isolates of Groundnut SeedsJimoh hairiyahAinda não há avaliações

- Ban Dot AnDocumento8 páginasBan Dot AnMaria Ina Dulce SAinda não há avaliações

- tmpEAC2 TMPDocumento11 páginastmpEAC2 TMPFrontiersAinda não há avaliações

- Isolation and Identification of Phytopathogenic Bacteria in Vegetable Crops in West Africa (Côte D'ivoire)Documento11 páginasIsolation and Identification of Phytopathogenic Bacteria in Vegetable Crops in West Africa (Côte D'ivoire)dawit gAinda não há avaliações

- JPAM Vol 15 Issue1 P 232-239Documento8 páginasJPAM Vol 15 Issue1 P 232-239Jefri Nur HidayatAinda não há avaliações

- Effect of Some Crude Plant Extracts On GROWTH OF Colletotrichum Capsici (Synd) Butler & Bisby, CAUSAL Agent of Pepper AnthracnoseDocumento7 páginasEffect of Some Crude Plant Extracts On GROWTH OF Colletotrichum Capsici (Synd) Butler & Bisby, CAUSAL Agent of Pepper AnthracnoseAbbe Cche DheAinda não há avaliações

- AjayiandOyedele-EVALUATIONOFAlliumsativumA LinnCRUDEEXTRACTSANDTrichodermaasperellumDocumento8 páginasAjayiandOyedele-EVALUATIONOFAlliumsativumA LinnCRUDEEXTRACTSANDTrichodermaasperellumAjoke AdegayeAinda não há avaliações

- M.P.prasad and Sunayana DagarDocumento11 páginasM.P.prasad and Sunayana DagarAbhishek SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Mycoendophytes As Pest Control Agents, Using Culture Filtrates, Against Green Apple Aphid (Hemiptera, Aphididae)Documento11 páginasMycoendophytes As Pest Control Agents, Using Culture Filtrates, Against Green Apple Aphid (Hemiptera, Aphididae)Cedrus CedrusAinda não há avaliações

- Evaluation of Efficacy of Different Grain Protectants AgainstDocumento8 páginasEvaluation of Efficacy of Different Grain Protectants AgainstPalash MondalAinda não há avaliações

- Evaluation of The Prophylactic Activity of Ethanolic Extract of Ricinus Communis L. Against Plasmodium Berghei in MiceDocumento11 páginasEvaluation of The Prophylactic Activity of Ethanolic Extract of Ricinus Communis L. Against Plasmodium Berghei in MiceUMYU Journal of Microbiology Research (UJMR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Fusarium Pallidoro - A New Biofertilizer PDFDocumento8 páginasFusarium Pallidoro - A New Biofertilizer PDFPaulino Alfonso SuarezAinda não há avaliações

- Inventarisasi Dan Identifikasi Hama Dan Penyakit Utama Tanaman Jagung (Zea Mays L.), Yustina M. S. W. Pu'u, Sri WahyuniDocumento11 páginasInventarisasi Dan Identifikasi Hama Dan Penyakit Utama Tanaman Jagung (Zea Mays L.), Yustina M. S. W. Pu'u, Sri WahyuniJefri DwiAinda não há avaliações

- Mycoflora of Stored Parkia Biglobosa (Jacq.) R.br. Ex G.don (LocustDocumento6 páginasMycoflora of Stored Parkia Biglobosa (Jacq.) R.br. Ex G.don (LocustNahum TimothyAinda não há avaliações

- 5 PaperDocumento6 páginas5 PaperDr. Nilesh Baburao JawalkarAinda não há avaliações

- Field Attractants For Pachnoda Interrupta Selected by Means of GC-EAD and Single Sensillum ScreeningDocumento14 páginasField Attractants For Pachnoda Interrupta Selected by Means of GC-EAD and Single Sensillum Screening10sgAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal Spoilage Guava Fruit - Mikpang PDFDocumento6 páginasJurnal Spoilage Guava Fruit - Mikpang PDFdellavencaAinda não há avaliações

- Pyriforme, Arimillaria Tabescens and Agaricus Bisporus Available in TheDocumento10 páginasPyriforme, Arimillaria Tabescens and Agaricus Bisporus Available in TheChandran MuthiahAinda não há avaliações

- Identification of Antimicrobial Properties of Cashew, Anacardium Occidentale L. (Family Anacardiaceae) Agedah, C E Bawo, D D S Nyananyo, B LDocumento3 páginasIdentification of Antimicrobial Properties of Cashew, Anacardium Occidentale L. (Family Anacardiaceae) Agedah, C E Bawo, D D S Nyananyo, B LglornumrAinda não há avaliações

- White RootDocumento8 páginasWhite RootMuhd Nur Fikri ZulkifliAinda não há avaliações

- Evaluation of Compost Fortified With Trichoderma Spp. Isolates As Biological Agents Against Broomrape of Chamomile HerbsDocumento8 páginasEvaluation of Compost Fortified With Trichoderma Spp. Isolates As Biological Agents Against Broomrape of Chamomile HerbsAhmed SahabAinda não há avaliações

- Keyword: Persea Americana, Antiproliferative Activity, Apoptotic Effect, Flow Cytometer, Proximate Analysis AbstractDocumento6 páginasKeyword: Persea Americana, Antiproliferative Activity, Apoptotic Effect, Flow Cytometer, Proximate Analysis Abstractgusti ningsihAinda não há avaliações

- Parasites of Edible VegetablesDocumento12 páginasParasites of Edible VegetablesVictor VinesAinda não há avaliações

- Micorriza en ChileDocumento7 páginasMicorriza en ChileEZEQUIELSOLIAinda não há avaliações

- Magifera PDFDocumento5 páginasMagifera PDFNguyen Thi Ai LanAinda não há avaliações

- (46-51) Effect of Plant Extracts On Post Flowering Insect Pests and Grain Yield of Cowpea (Vigna Unguiculata (L.) Walp.) in Maiduguri Semi Arid Zone of NigeriaDocumento7 páginas(46-51) Effect of Plant Extracts On Post Flowering Insect Pests and Grain Yield of Cowpea (Vigna Unguiculata (L.) Walp.) in Maiduguri Semi Arid Zone of NigeriaAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Sensitivity of Colletotrichum Species Responsible For Banana Anthracnose Disease To Some Fungicides Used in Postharvest Treatments in Côte D'ivoireDocumento6 páginasSensitivity of Colletotrichum Species Responsible For Banana Anthracnose Disease To Some Fungicides Used in Postharvest Treatments in Côte D'ivoireIJEAB JournalAinda não há avaliações

- Control of Whiteflies and AphidDocumento6 páginasControl of Whiteflies and Aphidsures108Ainda não há avaliações

- p1 Research PaperDocumento19 páginasp1 Research PaperChandran MuthiahAinda não há avaliações

- Studebaker EffectsInsecticidesOrius 2003Documento9 páginasStudebaker EffectsInsecticidesOrius 2003Hasan Ali KüçükAinda não há avaliações

- Methods For Isolation of Entomopathogenic Fungi From The Soil EnvironmentDocumento18 páginasMethods For Isolation of Entomopathogenic Fungi From The Soil Environmenttito cuadrosAinda não há avaliações

- Asymptotic Properties of Bayes Factor in One - Way Repeated Measurements ModelDocumento17 páginasAsymptotic Properties of Bayes Factor in One - Way Repeated Measurements ModelAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Availability, Accessibility and Use of Information Resources and Services Among Information Seekers of Lafia Public Library in Nasarawa StateDocumento13 páginasAvailability, Accessibility and Use of Information Resources and Services Among Information Seekers of Lafia Public Library in Nasarawa StateAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Assessment of Relationships Between Students' Counselling NeedsDocumento17 páginasAssessment of Relationships Between Students' Counselling NeedsAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Attitude of Muslim Female Students Towards Entrepreneurship - A Study On University Students in BangladeshDocumento12 páginasAttitude of Muslim Female Students Towards Entrepreneurship - A Study On University Students in BangladeshAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Assessment of The Skills Possessed by The Teachers of Metalwork in The Use of Computer Numerically Controlled Machine Tools in Technical Colleges in Oyo StateDocumento8 páginasAssessment of The Skills Possessed by The Teachers of Metalwork in The Use of Computer Numerically Controlled Machine Tools in Technical Colleges in Oyo StateAlexander Decker100% (1)

- Assessment of Some Micronutrient (ZN and Cu) Status of Fadama Soils Under Cultivation in Bauchi, NigeriaDocumento7 páginasAssessment of Some Micronutrient (ZN and Cu) Status of Fadama Soils Under Cultivation in Bauchi, NigeriaAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Concerning Food Safety Among Restaurant Workers in Putrajaya, MalaysiaDocumento10 páginasAssessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Concerning Food Safety Among Restaurant Workers in Putrajaya, MalaysiaAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Assessment of Housing Conditions For A Developing Urban Slum Using Geospatial AnalysisDocumento17 páginasAssessment of Housing Conditions For A Developing Urban Slum Using Geospatial AnalysisAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Assessment of The Practicum Training Program of B.S. Tourism in Selected UniversitiesDocumento9 páginasAssessment of The Practicum Training Program of B.S. Tourism in Selected UniversitiesAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Availability and Use of Instructional Materials and FacilitiesDocumento8 páginasAvailability and Use of Instructional Materials and FacilitiesAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Assessment of Teachers' and Principals' Opinion On Causes of LowDocumento15 páginasAssessment of Teachers' and Principals' Opinion On Causes of LowAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Barriers To Meeting The Primary Health Care Information NeedsDocumento8 páginasBarriers To Meeting The Primary Health Care Information NeedsAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Applying Multiple Streams Theoretical Framework To College Matriculation Policy Reform For Children of Migrant Workers in ChinaDocumento13 páginasApplying Multiple Streams Theoretical Framework To College Matriculation Policy Reform For Children of Migrant Workers in ChinaAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Are Graduates From The Public Authority For Applied Education and Training in Kuwaiti Meeting Industrial RequirementsDocumento10 páginasAre Graduates From The Public Authority For Applied Education and Training in Kuwaiti Meeting Industrial RequirementsAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Assessment of Survivors' Perceptions of Crises and Retrenchments in The Nigeria Banking SectorDocumento12 páginasAssessment of Survivors' Perceptions of Crises and Retrenchments in The Nigeria Banking SectorAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Analysis The Performance of Life Insurance in Private InsuranceDocumento10 páginasAnalysis The Performance of Life Insurance in Private InsuranceAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Assessment of Productive and Reproductive Performances of CrossDocumento5 páginasAssessment of Productive and Reproductive Performances of CrossAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Assessing The Effect of Liquidity On Profitability of Commercial Banks in KenyaDocumento10 páginasAssessing The Effect of Liquidity On Profitability of Commercial Banks in KenyaAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Antioxidant Properties of Phenolic Extracts of African Mistletoes (Loranthus Begwensis L.) From Kolanut and Breadfruit TreesDocumento8 páginasAntioxidant Properties of Phenolic Extracts of African Mistletoes (Loranthus Begwensis L.) From Kolanut and Breadfruit TreesAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Assessment in Primary School Mathematics Classrooms in NigeriaDocumento8 páginasAssessment in Primary School Mathematics Classrooms in NigeriaAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Antibiotic Resistance and Molecular CharacterizationDocumento12 páginasAntibiotic Resistance and Molecular CharacterizationAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Application of The Diagnostic Capability of SERVQUAL Model To An Estimation of Service Quality Gaps in Nigeria GSM IndustryDocumento14 páginasApplication of The Diagnostic Capability of SERVQUAL Model To An Estimation of Service Quality Gaps in Nigeria GSM IndustryAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Application of Panel Data To The Effect of Five (5) World Development Indicators (WDI) On GDP Per Capita of Twenty (20) African Union (AU) Countries (1981-2011)Documento10 páginasApplication of Panel Data To The Effect of Five (5) World Development Indicators (WDI) On GDP Per Capita of Twenty (20) African Union (AU) Countries (1981-2011)Alexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Assessment of Factors Responsible For Organizational PoliticsDocumento7 páginasAssessment of Factors Responsible For Organizational PoliticsAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- An Investigation of The Impact of Emotional Intelligence On Job Performance Through The Mediating Effect of Organizational Commitment-An Empirical Study of Banking Sector of PakistanDocumento10 páginasAn Investigation of The Impact of Emotional Intelligence On Job Performance Through The Mediating Effect of Organizational Commitment-An Empirical Study of Banking Sector of PakistanAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Assessment For The Improvement of Teaching and Learning of Christian Religious Knowledge in Secondary Schools in Awgu Education Zone, Enugu State, NigeriaDocumento11 páginasAssessment For The Improvement of Teaching and Learning of Christian Religious Knowledge in Secondary Schools in Awgu Education Zone, Enugu State, NigeriaAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Analysis of Teachers Motivation On The Overall Performance ofDocumento16 páginasAnalysis of Teachers Motivation On The Overall Performance ofAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Analyzing The Economic Consequences of An Epidemic Outbreak-Experience From The 2014 Ebola Outbreak in West AfricaDocumento9 páginasAnalyzing The Economic Consequences of An Epidemic Outbreak-Experience From The 2014 Ebola Outbreak in West AfricaAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Analysis of Frauds in Banks Nigeria's ExperienceDocumento12 páginasAnalysis of Frauds in Banks Nigeria's ExperienceAlexander DeckerAinda não há avaliações

- Assess White PaperDocumento6 páginasAssess White PaperCristian ColicoAinda não há avaliações

- 2022 Australian Grand Prix - Race Director's Event NotesDocumento5 páginas2022 Australian Grand Prix - Race Director's Event NotesEduard De Ribot SanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Topographic Map of New WaverlyDocumento1 páginaTopographic Map of New WaverlyHistoricalMapsAinda não há avaliações

- Training Manual W Appendix 3-20-14 RsDocumento193 páginasTraining Manual W Appendix 3-20-14 RsZakir Ullah100% (5)

- DCIT 21 & ITECH 50 (John Zedrick Iglesia)Documento3 páginasDCIT 21 & ITECH 50 (John Zedrick Iglesia)Zed Deguzman100% (1)

- Essay 'Why Alice Remain Popular?'Documento3 páginasEssay 'Why Alice Remain Popular?'Syamil AdzmanAinda não há avaliações

- Nipas Act, Ipra, LGC - Atty. Mayo-AndaDocumento131 páginasNipas Act, Ipra, LGC - Atty. Mayo-AndaKing Bangngay100% (1)

- Semi Detailed LP in Math 8 Inductive Reasoning by Jhon Edward G. Seballos San Roque NHS BulalacaoDocumento3 páginasSemi Detailed LP in Math 8 Inductive Reasoning by Jhon Edward G. Seballos San Roque NHS BulalacaoRuth Matriano100% (2)

- 33 - The Passive Acoustic Effect of Turbo-CompressorsDocumento10 páginas33 - The Passive Acoustic Effect of Turbo-CompressorsSindhu R ShekharAinda não há avaliações

- Parallel Merge Sort With MPIDocumento12 páginasParallel Merge Sort With MPIIrsa kanwallAinda não há avaliações

- The Contemporary Contrabass. by Bertram TuretzkyDocumento5 páginasThe Contemporary Contrabass. by Bertram TuretzkydoublepazzAinda não há avaliações

- Math 20-2 Unit Plan (Statistics)Documento4 páginasMath 20-2 Unit Plan (Statistics)api-290174387Ainda não há avaliações

- Mamzelle Aurélie's RegretDocumento3 páginasMamzelle Aurélie's RegretDarell AgustinAinda não há avaliações

- Class XII PHY - EDDocumento7 páginasClass XII PHY - EDsampoornaswayamAinda não há avaliações

- Family Values, Livelihood Resources and PracticesDocumento285 páginasFamily Values, Livelihood Resources and PracticesRogelio LadieroAinda não há avaliações

- Hrm-Group 1 - Naturals Ice Cream FinalDocumento23 páginasHrm-Group 1 - Naturals Ice Cream FinalHarsh parasher (PGDM 17-19)Ainda não há avaliações

- Curso de GaitaDocumento24 páginasCurso de GaitaCarlosluz52Ainda não há avaliações

- Model HA-310A: Citizens BandDocumento9 páginasModel HA-310A: Citizens BandluisAinda não há avaliações

- 17-185 Salary-Guide Engineering AustraliaDocumento4 páginas17-185 Salary-Guide Engineering AustraliaAndi Priyo JatmikoAinda não há avaliações

- BIO125 Syllabus Spring 2020Documento3 páginasBIO125 Syllabus Spring 2020Joncarlo EsquivelAinda não há avaliações

- Project Report: "Attendance Management System"Documento9 páginasProject Report: "Attendance Management System"SatendraSinghAinda não há avaliações

- Eye Floaters Cure - Natural Treatment For Eye FloatersDocumento34 páginasEye Floaters Cure - Natural Treatment For Eye FloatersVilluri Venkata Kannaapparao50% (2)

- Job - RFP - Icheck Connect Beta TestingDocumento10 páginasJob - RFP - Icheck Connect Beta TestingWaqar MemonAinda não há avaliações

- Guidance On The Design Assessment and Strengthening of Masonry Parapets On Highway StructuresDocumento93 páginasGuidance On The Design Assessment and Strengthening of Masonry Parapets On Highway Structuresalan_jalil9365Ainda não há avaliações

- GE Oil & Gas Emails Discuss Earthing Cable SpecificationsDocumento6 páginasGE Oil & Gas Emails Discuss Earthing Cable Specificationsvinsensius rasaAinda não há avaliações

- Camaras PointGreyDocumento11 páginasCamaras PointGreyGary KasparovAinda não há avaliações

- Speaking Topics b1Documento3 páginasSpeaking Topics b1Do HoaAinda não há avaliações

- Event Driven Dynamic Systems: Bujor PăvăloiuDocumento35 páginasEvent Driven Dynamic Systems: Bujor Păvăloiuezeasor arinzeAinda não há avaliações

- Finding Buyers Leather Footwear - Italy2Documento5 páginasFinding Buyers Leather Footwear - Italy2Rohit KhareAinda não há avaliações

- 6 Grade English Language Arts and Reading Pre APDocumento3 páginas6 Grade English Language Arts and Reading Pre APapi-291598026Ainda não há avaliações