Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Applying A Cognitive Behavioral Model of Health Anxiety in A Cancer Genetics Service

Enviado por

allura329Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Applying A Cognitive Behavioral Model of Health Anxiety in A Cancer Genetics Service

Enviado por

allura329Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

_______________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

Report nformation from ProQuest

May 02 2013 21:50

_______________________________________________________________

02 May 2013 ProQuest

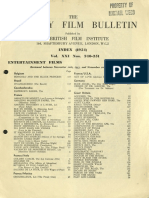

Table of contents

1. Applying a cognitive behavioral model of health anxiety in a cancer genetics service................................ 1

Bibliography...................................................................................................................................................... 25

02 May 2013 ii ProQuest

Document 1 of 1

Applying a cognitive behavioral model of health anxiety in a cancer genetics service.

Author: Rimes, Katharine A.;

1

; Salkovskis, Paul M.;

2

; Jones, Linda;

3

; Lucassen, Anneke M.;

4

;

1

Department

of Psychological Medicine, King's College London, nstitute of Psychiatry, London, United Kingdom

k.rimes@iop.kcl.ac.uk;

2

Department of Psychology, King's College London, nstitute of Psychiatry, London,

United Kingdom;

3

Genetics Service, Carmarthenshire National Health Service Trust, United Kingdom;

4

Wessex Clinical Genetics Service, Southampton, United Kingdom

Publication info: Health Psychology 25. 2 (Mar 2006): 171-180.

ProQuest document link

Abstract: A cognitive-behavioral model of health anxiety was used to investigate reactions to genetic counseling

for cancer. Participants (N = 218) were asked to complete a questionnaire beforehand and 6 months later.

There was an overall decrease in levels of cancer-related anxiety, although 24% of participants showed

increased cancer-related anxiety at follow-up. People who had a general tendency to worry about their health

reported more cancer-related anxiety than those who did not at both time points. This health-anxious group also

showed a postcounseling anxiety reduction, whereas the others showed no significant change. Participants with

breast or ovarian cancer in their family were more anxious than participants with colon cancer in their family.

Preexisting beliefs were significant predictors of anxiety, consistent with a cognitive-behavioral approach.

(PsycNFO Database Record (c) 2012 APA, all rights reserved)(journal abstract)

Links: Linking Service

Full text:

Contents

Abstract

Methods

Participants

Procedure

Measures

Beliefs and feelings about cancer

General mood ratings

Demographic and medical/family history

Additional postcounseling measures

Statistical Analysis

Results

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Sample

Characteristics of People Who Did Not Return the Follow-up Questionnaire

mpact of Genetic Counseling

Accuracy of risk perceptions

Anxiety about developing cancer

Comparison of Anxiety and Beliefs About Cancer in People With Family Histories of Breast and/or Ovarian or

Colon Cancer

General group differences

02 May 2013 Page 1 of 25 ProQuest

Did people who tended to worry about their health report more negative cancer-related beliefs and anxiety and

respond particularly negatively to "increased risk information?

Prediction of Anxiety and Beliefs

Prediction of anxiety and beliefs from medical/family history variables

Prediction of beliefs and anxiety from variables derived from the CB model

Discussion

Show less

Figures and Tables

Figure 1

Table 1

Table 2

Table 3

Table 4

Table 5

Table 6

Show less AbstractA cognitive-behavioral model of health anxiety was used to investigate reactions to genetic

counseling for cancer. Participants (N = 218) were asked to complete a questionnaire beforehand and 6

months later. There was an overall decrease in levels of cancer-related anxiety, although 24% of participants

showed increased cancer-related anxiety at follow-up. People who had a general tendency to worry about their

health reported more cancer-related anxiety than those who did not at both time points. This health-anxious

group also showed a postcounseling anxiety reduction, whereas the others showed no significant change.

Participants with breast or ovarian cancer in their family were more anxious than participants with colon cancer

in their family. Preexisting beliefs were significant predictors of anxiety, consistent with a cognitive-behavioral

approach. The importance of genetic susceptibility to certain cancers has led to an increase in the demand for

genetic counseling by specialist genetic services, particularly from members of families with a history of breast

and/or ovarian cancer or colon cancer (Ravine &Sampson, 2001). Genetic counseling is "the process by which

patients or relatives at risk of a disorder that may be hereditary are advised of the consequences of the

disorder, the probability of developing or transmitting it and of the ways in which this may be prevented, avoided

or ameliorated (Harper, 1998, p. 3). However, providing patients with such information does not necessarily

ensure that they will interpret or recall it correctly (Watson et al., 1998). Furthermore, although genetic

counseling may bring reassurance to some individuals, it also has the potential to cause psychological distress.

Therefore, the U.K. Department of Health (1996) has recommended that psychological support be part of the

genetic counseling process, and assessment of the psychological impact of these services has been advocated.

Relatively little is known about how different people react to genetic counseling or how adverse reactions should

be handled.There is evidence that a significant minority of individuals with a family history of cancer experience

high levels of psychological distress (e.g., Kash, Holland, Halper, &Miller, 1992; Lerman et al., 1993). Some

studies have found that genetic counseling is associated with decreases in overall levels of distress (e.g., Keller

et al., 2002), whereas others have found no significant change (e.g., Hopwood, Shenton, Lalloo, Evans,

&Howell, 2001). Prospective studies have found some evidence that individuals' risk perceptions tend to

become somewhat more accurate after genetic counseling although this has not been confirmed in randomized

controlled trials (Braithwaite, Emery, Walter, Provost, &Sutton, 2004; Meiser &Halliday, 2002). Those

02 May 2013 Page 2 of 25 ProQuest

conducting previous research have generally failed to examine the impact of genetic counseling on other

cancer-related beliefs or to compare reactions of people being counseled for different types of cancer.Even if a

sample as a whole shows a decrease or no significant change on measures of distress after genetic counseling,

particular individuals may experience substantial increases in distress. As the demand for genetic counseling

and testing increases, psychological support will need to be focused on those at high risk for experiencing

adverse psychological effects (Grosfeld, Lips, Beemer, &ten Kroode, 2000). A few researchers have conducted

studies on precounseling predictors of postcounseling distress. They have generally found that scores on a

precounseling measure of distress can predict postcounseling scores on the same measure (Cull et al., 1999;

Lerman et al., 1996). Precounseling risk perceptions can also predict postcounseling distress (Ritvo et al., 2000

). Sociodemographic variables generally predict little or no variance in postcounseling distress.Few authors of

published studies have reported using a psychological model to guide their search for precounseling predictors

of distress or risk perceptions in people undergoing genetic counseling. A notable exception is the use of

Miller's (1987) monitoring/blunting model. One study (Lerman et al., 1996) found that women with a family

history of breast cancer who had a monitoring coping style showed increases in general distress from baseline

to follow-up, although there was no impact on cancer-specific distress. However, a number of studies have

failed to find any association between scores on the monitoring scale and risk perceptions or distress (e.g.,

Audrain et al., 1997; Cull et al., 1999).t has been suggested that applying a cognitive-behavioral (CB) approach

to the understanding of reactions to genetic screening may be fruitful (Salkovskis &Rimes, 1997). One of the

most commonly observed psychological problems is anxiety about developing the condition in question. A CB

approach to health anxiety (Warwick &Salkovskis, 1990) suggests that the extent to which people are likely to

make particularly negative interpretations of health information, and therefore to experience excessive anxiety,

is determined partly by their preexisting general beliefs about health, their specific beliefs about the disease in

question, and the extent to which their interpretations trigger maintaining factors such as checking or

reassurance-seeking behaviors. At least four aspects of their specific beliefs about the illness are thought to be

central to the perception of threat and hence to the anxiety reaction: (a) how likely they perceive the illness to

be, (b) how severe the negative consequences of the illness would be, (c) how well they think they would cope if

they developed the illness, and (d) how much external help might be available (e.g., how treatable a condition

might be). This CB model of health anxiety has been successfully applied to the prediction of individual

differences in psychological reactions to a nongenetic type of health assessmentbone density screening for

osteoporosis (Rimes &Salkovskis, 2002). For example, it was found that greater anxiety about osteoporosis

after bone density screening was associated with more negative prescanning beliefs about the likelihood of

developing osteoporosis, how serious it is to have low bone density, how well one would cope if one had

osteoporosis, the likelihood of successful treatment, and preexisting tendencies to worry about one's health and

to avoid illness-related matters. Several of these factors were stronger predictors of anxiety than the scanning

result itself.The main aims of the present study were

to investigate the impact of genetic counseling on anxiety about cancer and cancer-related beliefs 6 months

after counseling,

to investigate whether people who tended to worry about their health would show greater distress and more

negative cancer-related beliefs before counseling and would show more negative reactions to the information

they received, and

02 May 2013 Page 3 of 25 ProQuest

to investigate whether precounseling beliefs about the cancer, derived from a CB approach to health anxiety,

would be predictive of anxiety about cancer. t was hypothesized that preexisting beliefs would be a better

predictor of postcounseling anxiety about cancer than participants' calculated lifetime risk of cancer.

A further aim was to compare the psychological effects of genetic counseling on participants from families with

breast and/or ovarian cancer with people from families with colon cancer. Previously published studies have not

compared the effects of genetic counseling on patients with different types of familial cancer. People have

different beliefs and levels of anxiety about the various types of cancer (e.g., Wroe, Salkovskis &Rimes, 1998),

and the CB model would suggest that the impact of genetic counseling would therefore also vary in relation to

these preexisting beliefs and anxiety. Thus, it would not be appropriate to simply assume that reactions to

genetic counseling for different forms of cancer are similar. f group differences were found, this information may

also be helpful for genetic counselors, who often have to counsel people with different types of cancer in their

family backgrounds. Therefore, in the present study, we compared the reactions of people with family histories

of colon or breast and/or ovarian cancer, which were the two most common types of family cancer history in this

sample. Methods ParticipantsParticipants were 218 people referred to the Oxford Regional Genetics Service,

Churchill Hospital, Oxford, United Kingdom. All patients referred to the clinic were sent the psychological

questions together with the standard preclinic-visit questionnaire, so everyone who pursued their referral

participated in at least the first part of this study. Participants were included if they were 18 years or older and

had a family history but not personal history of cancer. ProcedureEveryone referred to the clinic was sent a

preclinic-visit questionnaire about family/medical history in order for us to calculate their lifetime risk of cancer.

For those from families with breast and/or ovarian cancer, the risk figures were derived by interpolating the

Claus data set (Claus, Risch, &Thompson, 1994) using the program Cyrillic (version 2.1; Cyrillic Software,

Oxfordshire, United Kingdom, 1999). For those from families with colon cancer, the probability of a dominantly

inherited cancer-predisposing gene was calculated using Bayes's theorem. The probability of developing cancer

was calculated using the population prevalence of cancer and the penetrance of known hereditary nonpolyposis

colorectal cancer (HNPCC) genes.People who were calculated to have a "low additional risk (i.e., at or near

population risk) were sent a letter informing them that their risk had been calculated and that the chances of the

cancers in their family being determined by a major inherited genetic component were very low. These letters

contained information about genetic influences on cancer; population rates of cancer; recommendations, where

appropriate, regarding health behaviors; and an explanation of why frequent screening was not necessary in

their case. Patients were told that they could contact the service if they had further questions. n this sample,

28% (n = 61) were sent a letter rather than being seen in clinic. ndividuals were seen in clinic by a specialist

genetics nurse or physician if their calculated risk was not low or if further information was needed. For those

who were seen in clinic (n = 157; 72%), the genetic consultation included information about genetic influences

on cancer; population rates of cancer; and recommendations regarding health behaviors, surveillance

measures, and genetic testing, as appropriate. For both the individuals seen in clinic and those receiving the

"low-risk letter, sometimes an absolute risk figure (e.g., lifetime risk of 20%) was provided, but more commonly

their risk was discussed in relation to the general population risk. A letter summarizing the content of the

consultation was sent afterward. (When discussing the present study, we will use the phrase "genetic

counseling to refer to both the face-to-face consultation and the letter sent to some of those at low risk).Follow-

up questionnaires were posted 6 months after the time when the participants was either seen in clinic or sent

the letter providing their risk information. One reminder was sent to those who did not reply (n = 106, 48.6%).

02 May 2013 Page 4 of 25 ProQuest

Of those participants who were sent reminders, 46 subsequently returned their questionnaires. These

individuals did not report significantly different levels of postcounseling anxiety than those who returned their

questionnaire unprompted, t (150) = 0.6. Measures Beliefs and feelings about cancerVisual analogue scales

(0100) were used, similar to those used in a study of the prediction of responses to bone density screening (

Rimes &Salkovskis, 2002). The scales are used to assess feelings and beliefs about the type of cancer that

occurred in the participants' families: anxiety about this cancer, need for reassurance and beliefs about their risk

for this type of cancer, likelihood that they would be able to prevent it, how bad it would be if they developed this

cancer, how well they would cope if they developed this cancer, and how likely it is that the cancer would be

successfully treated if they were to develop it. For ratings of the likelihood of developing cancer, participants

were asked to report their "feelings rather than what [they thought] a 'rational' or 'correct' response would be.

This question was based on the assumption that people's feelings about their risk would show a greater

association to their anxiety than what they might regard as a "rational response in which they did not really

believe. Risk perceptions assessed in this way had been found to be highly predictive of reactions to a different

type of health screening in a previous study (Rimes &Salkovskis, 2002). For all the scales, a higher score

indicated greater concern or more negative beliefs. General mood ratingsParticipants were asked to rate how

much they worry about their health in general and their current mood (sadness/low mood, anxiety) using visual

analogue scales as described earlier. The current mood measures have been used in previous research into

psychological aspects of health screening (e.g., Rimes &Salkovskis, 2002; Rimes, Salkovskis, &Shipman, 1999

; Wroe, Salkovskis, &Rimes, 2000). They have shown good sensitivity to change in mood over time; for

example, ratings on these measures increase immediately after a "high-risk result from bone mineral density

screening for osteoporosis (Rimes et al., 1999). The measure of a tendency to worry about one's health in

general was devised for this study because there was no space to include the full health anxiety questionnaire

used in our previous research. Demographic and medical/family historyDemographic and medical/family history

information was taken from the standard clinical questionnaire that participants were asked to complete by the

genetics clinic. Additional postcounseling measuresTwo additional questions were asked at follow-up: The first

was "Do you feel more or less worried about developing this condition since being referred to the genetics

clinic? Responses on a 7-point scale ranged from much less worried to much more worried . The second

question was "Compared with the 'average person,' how much 'at risk' do you feel for developing this condition

in the future? Responses on the 7-point scale ranged from much less at risk to much more at risk . Statistical

AnalysisChi-square analyses and independent t tests were used to compare the characteristics of participants

from families with breast and/or ovarian or colon cancer. People from families with histories of breast or ovarian

cancer were combined because some genes (breast cancer genes 1 and 2, or BRCA1 and BRCA2) have been

identified as ones that increase one's vulnerability to both these forms of cancer. People were excluded if they

had both colon cancer and breast or ovarian cancer in their family. Repeated measures analyses of variance

(ANOVAs) were used to compare the two groups in terms of the psychological variables before and after

counseling.To investigate responses of those with high and low levels of preexisting general health worry, we

created two dichotomous variables to represent high and low levels of general health worry and high and low

calculated risk of cancer. Cutoff scores (general worry <25 vs. general worry 30; calculated risk <11.9% vs.

calculated risk >12) were chosen to give similar sized groups. ANOVAs were used to examine change over time

in the psychological variables, with health worry and calculated risk as grouping variables.Multiple regression

analyses were performed to investigate predictors of anxiety and cancer-related beliefs. n cases in which

02 May 2013 Page 5 of 25 ProQuest

variables were selected according to the CB model, standard (simultaneous) multiple regression analysis was

used. For exploratory analyses looking at whether medical/family history variables were associated with anxiety

and beliefs, stepwise regression methods were used. A variable was entered if the significance level of its F

was less than 0.05 and was removed if the significance level of F was greater than 0.1. For a number of the

participants, a full family history was not available, so analyses involving these variables typically involved a

smaller number of participants. Gender was not included in these analyses because it would be confounded

with a history of breast and/or ovarian cancer. Results Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of the

SampleThe sample contained 189 women (86.7%) and 29 men (13.3%). The mean age of the participants was

39.4 years (SD = 9.9). Participants were not routinely questioned about ethnicity except whether they or

members of their immediate family were Jewish, because Jews of Ashkenazi descent may have elevated risk

for certain types of cancers. Of the 147 participants for whom data was available, 3 (2.0%) said that they or

someone in their immediate family was Jewish. n keeping with the community that the genetics clinic serves,

the majority of the participants were of Caucasian origin.Of those participants for whom the data were available,

the family histories were as follows: 68.8% with breast and/or ovarian cancer, 24.2% with colon cancer, 2.5%

with both breast and/or ovarian and colon cancer, <1% with prostate cancer, <1% with lung cancer, and 3.2%

with three or more different cancers. For some of the analyses described below, participants with family

histories of breast and/or ovarian cancer were compared with participants with colon cancer in their family.

Participants with family histories of breast and/or ovarian cancer were all women, whereas 45% of those with

colon cancer family histories were women. The participants in the breast and/or ovarian group were significantly

younger, t (144) = ~2.7, p <.05, than those in the colon cancer group, (M = 39.4, SD = 9.0, and M = 44.2,

SD = 10.9, respectively). There was no significant difference, t (142) = 0.3, in the calculated lifetime risk of

cancer for the individuals with breast and/or ovarian or colon cancer family histories (M = 16.2, SD = 9.7, and

M = 14.3, SD = 10.7, respectively). As would be expected, people from families with breast cancer were

significantly more likely to have a same-gender parent who had had cancer,

2

(1, N = 155) = 3.9, p <.05, had

more relatives of the same gender as themselves with cancer, t (153) = 2.4, p <.05, and had a greater

proportion of same-gender relatives with cancer, t (153) = 2.9, p <.005. There were no significant differences

between the two groups regarding the number or proportion of relatives who had had cancer, the number or

proportion of cancers on the most affected side of the family, the number of parents who had had cancer,

whether they had had a parent with cancer who had died, the number of siblings who had had cancer, the

youngest age of cancer onset in the family, or whether they had had a previous major illness. Characteristics of

People Who Did Not Return the Follow-up QuestionnaireCompared with those who returned the follow-up

questionnaire, people who did not return the questionnaire (29.8%) were significantly younger and had

significantly higher precounseling ratings of anxiety about cancer, belief in the likelihood that they would develop

cancer, need for reassurance, and general anxiety; see Table 1. There was a nonsignificant trend for them to

have a higher calculated lifetime risk of cancer, t (213) = 2.0, p = .084.

02 May 2013 Page 6 of 25 ProQuest

02 May 2013 Page 7 of 25 ProQuest

Enlarge this mage.

Characteristics of Participants Who Did and Did Not Return the Follow-Up Questionnaire mpact of Genetic

Counseling Accuracy of risk perceptionsCorrelations between risk beliefs and calculated risk were r = .15 (p =

.064) before counseling and r = .23 (p <.05) 6 months afterward for the 150 participants who reported their risk

perceptions at both time points. Using Williams's (1959) revision of Hotelling's formula for testing the difference

between two nonindependent correlations, it was found that there was no significant difference between the

correlations for perceived risk and calculated risk before and after genetic counseling, t (147) = ~0.735. The

extent to which participants under- or overestimated their risk is shown in Table 2. The mean amount of

discrepancy (in either direction) between risk beliefs and calculated risk before the counseling was 41.2 (SD =

22.5) and 6 months after the counseling was 34.3 (SD = 22.1). A paired t test indicated that this represented a

significant improvement in accuracy of risk beliefs after counseling, t (152) = 4.0, p <.0005.

Enlarge this mage.

Accuracy of Risk Perceptions Before and After Counseling (n = 150) Anxiety about developing cancerThose

who completed questionnaires at both points showed an overall decrease in anxiety about developing cancer,

t (148) = 4.8, p <.0005, Cohen's d = 0.33, with a precounseling mean of 48.2 (SD = 25.9) and a

postcounseling mean of 39.8 (SD = 25.6). However, 24.2% (36/149) of the sample had higher ratings of

cancer-related anxiety after counseling than before counseling (increase ranging from 5 to 45 points).

Comparison of Anxiety and Beliefs About Cancer in People With Family Histories of Breast and/or Ovarian or

Colon Cancer General group differencesFor most variables, there was a main effect of cancer type, with the

colon cancer group reporting lower levels of anxiety about cancer (Cohen's d = 0.43), general anxiety (Cohen's

d = 0.48), sadness/low mood (Cohen's d = 0.47), and need for reassurance (Cohen's d = 0.42). n addition,

the colon cancer group reported less negative beliefs about the likelihood of developing cancer in the near

future (Cohen's d = 0.53), likelihood of developing cancer at any point in the future (Cohen's d = 0.63), how

bad it would be to develop cancer (Cohen's d = 0.53), how well they would cope if they developed cancer

02 May 2013 Page 8 of 25 ProQuest

(Cohen's d = 0.41), and the likelihood of successful treatment (Cohen's d = 0.42). There were main effects of

time for several variables, with participants reporting lower levels of anxiety about developing cancer (Cohen's

d = 0.34) and general anxiety (Cohen's d = 0.30), lower perceived likelihood of developing cancer in the near

future (Cohen's d = 0.22) and at any point in the future (Cohen's d = 0.29), and lower need for reassurance

(Cohen's d = 0.63) at the 6-month follow-up (see Table 3 for means, standard deviations, and F values).

02 May 2013 Page 9 of 25 ProQuest

02 May 2013 Page 10 of 25 ProQuest

Enlarge this mage.

Changes in Beliefs and Distress Levels in People With Family Histories of Breast and/or Ovarian and Colon

CancerTo check that the group differences were not simply a result of the significant difference in age between

the two groups, we removed the 21 youngest participants from the breast cancer families and the two oldest

participants from the colon cancer families so that the two groups were matched for age (n = 87 and n = 36,

respectively). The ANOVAs were repeated, and the same patterns of results were found, although some effects

were slightly weaker or stronger than in the original analyses.Because the group differences may have resulted

from the fact that all participants in the breast cancer group were women whereas participants in the colon

cancer group were both men and women, we conducted exploratory analyses in which the ANOVAs were

repeated using only the 16 female colon cancer participants. Still significant group differences were found on

feelings concerning the likelihood of developing cancer and how bad it would be if one developed cancer, and

there were nonsignificant trends (.05 <p <.125) in the same direction for anxiety about cancer and the likelihood

of treatment success. The group differences concerning the need for reassurance or one's ability to cope if one

developed cancer were no longer significant. However, these results should be viewed with caution because of

the small number of female participants in the colon cancer group (n = 16) compared with the number in the

breast and/or ovarian group (n = 107). Did people who tended to worry about their health report more negative

cancer-related beliefs and anxiety and respond particularly negatively to "increased risk information?Contrary

to the prediction that people with a general tendency to worry about their health (high health-anxiety group)

would react particularly negatively to being told that they were at increased risk for cancer, there were no

significant Health Anxiety Risk Time interactions (all F s <2.5; see Table 4 for means, standard deviations,

and significant effects for all analyses in this section). There were significant Health Anxiety Time interactions

for anxiety about developing cancer, likelihood of developing cancer in the near future, need for reassurance,

how bad it would be if one developed cancer, and general state anxiety as well as a nonsignificant trend for

likelihood of developing cancer at any point in the future, F (1, 142) = 2.9, p = .089). Paired and independent t

tests were used to investigate these effects further, with alpha levels set at p <.025. These indicated that the

high health-anxiety group showed a significant reduction in anxiety about cancer after counseling (Cohen's d =

0.56), whereas the low health-anxiety group showed no significant change (Cohen's d = 0.13); see Figure 1a.

However, participants in the high health-anxiety group were significantly more anxious than the low health-

anxiety group at both time points (Cohen's d = 1.10 before counseling and 0.62 afterward). The same pattern

of results was shown for general state anxiety (Cohen's d = 0.50 for the change in the high health-anxiety

group, 0.14 for the change in the low health-anxiety group, 1.07 for group differences before counseling, and

0.73 afterward), perceived likelihood of developing cancer in the near future (Cohen's d = 0.39, 0.02, 0.74, and

0.35, respectively), and perceived likelihood of developing cancer at any point in the future (Cohen's d = 0.44,

0.18, 0.73, and 0.43, respectively; see Figure 1b). The high health-anxiety group had higher ratings of need for

reassurance both time points (Cohen's d = 1.08 before counseling and 0.59 afterward); both groups showed a

significant decrease by the follow-up (Cohen's d = 0.92 for the high health-anxiety group and 0.40 for the low

health-anxiety group), although the decrease was significantly larger in the high health-anxiety group.

02 May 2013 Page 11 of 25 ProQuest

Enlarge this mage.

Graphs depicting (a) anxiety about developing cancer in people with high and low levels of health anxiety and

calculated risk, measured before genetic counseling and 6 months later and (b) perceived likelihood of

developing cancer at any point in the future in people with high and low levels of health anxiety and calculated

risk

02 May 2013 Page 12 of 25 ProQuest

Enlarge this mage.

Graphs depicting (a) anxiety about developing cancer in people with high and low levels of health anxiety and

calculated risk, measured before genetic counseling and 6 months later and (b) perceived likelihood of

developing cancer at any point in the future in people with high and low levels of health anxiety and calculated

risk

02 May 2013 Page 13 of 25 ProQuest

02 May 2013 Page 14 of 25 ProQuest

Enlarge this mage.

Distress and Beliefs in People With Low and High Levels of Health Anxiety and Low and High Calculated Risk

for CancerFor beliefs about how bad it would be if they developed cancer, the high health-anxiety group had

more negative ratings at both time points (Cohen's d = 0.89 before counseling, 0.54 after), although the low

health-anxiety group's ratings became significantly more negative by the 6-month follow-up (Cohen's d = 0.24)

whereas the high health-anxiety group showed no significant change over time (Cohen's d = 0.07). The high

health-anxiety group also reported greater sadness/low mood (Cohen's d = 1.01) and more negative beliefs

about how they would cope if they developed cancer (Cohen's d = 0.60), but there was no interaction with time

for these variables.There were main effects of risk group for perceived likelihood of developing cancer at any

point in time (Cohen's d = 0.35) and for perceived risk compared with "the average person (Cohen's d = 0.47),

indicating that those with greater calculated lifetime risk had higher risk perceptions. No interactions between

risk group and time were found, indicating that those with lower and higher risk did not respond significantly

differently to genetic counseling. Prediction of Anxiety and Beliefs Prediction of anxiety and beliefs from

medical/family history variablesHigher pre- and postcounseling ratings of the likelihood developing of cancer at

any point in the future were predicted by younger age but by no other medical/family history variables.

Significant predictors of more negative beliefs about how bad it would be to develop cancer were having had a

parent dying of cancer, which entered the regression equation first, followed by having had a previous major

illness. None of the medical/family history variables were significant of predictors of pre- or postcounseling

anxiety about developing cancer. See Table 5 for details of these results.

02 May 2013 Page 15 of 25 ProQuest

02 May 2013 Page 16 of 25 ProQuest

Enlarge this mage.

Stepwise Multiple Regression Analyses Predicting Anxiety and Beliefs by Medical and Family History Variables

Prediction of beliefs and anxiety from variables derived from the CB modelPostcounseling beliefs about the

likelihood of cancer at any point in the future were significantly predicted by precounseling likelihood beliefs. n

the prediction of precounseling levels of anxiety about developing cancer, the following precounseling beliefs

entered as significant predictors: beliefs about the likelihood of developing cancer at any point in the future, the

likelihood of developing cancer in the near future, how bad it would be if one developed cancer, and the general

tendency to worry about one's health. Greater postcounseling anxiety about developing cancer was predicted

by higher precounseling ratings of the likelihood of developing cancer at any point in the future, more negative

beliefs about one's ability to cope if one developed cancer, and a general tendency to worry about one's health.

See Table 6 for details of these results.

02 May 2013 Page 17 of 25 ProQuest

02 May 2013 Page 18 of 25 ProQuest

Enlarge this mage.

Multiple Regression Analyses Predicting Anxiety and Beliefs From Other Psychological Variables Discussion

Six months after genetic counseling, there was an overall decrease in anxiety about cancer, although a

significant minority of participants showed higher levels of anxiety afterward. Factors influencing the impact of

the counseling included beliefs about cancer, a preexisting tendency to worry about one's health, and the type

of cancer in the family. As predicted, participants' precounseling beliefs were more important predictors of

distress after genetic counseling than the individuals' calculated risk of cancer. Precounseling beliefs were

influenced in part by the participants' previous experiences of illness.The reduction in anxiety about developing

cancer found in the present study is consistent with the findings of some previous studies of cancer-specific

distress (e.g., Bish et al., 2002) although most have found that postcounseling changes are not significant,

especially in the longer term (Braithwaite et al., 2004). Overall group changes can conceal important individual

variations, and in this case, 24% showed an increase in anxiety about developing cancer at the 6-month point

after counseling. The clinical significance of this level of increase is not known, but the issue requires further

investigation in case some individuals require further advice or help.The extent to which medical/family history

variables were predictive of beliefs and anxiety about cancer were investigated in exploratory analyses. These

showed that having had a parent who had died of cancer and having had a previous major illness were both

significant predictors of beliefs about how bad it would be to develop cancer. This indicates that people's

previous experience of illness, either in themselves and others, seems to affect their beliefs about the

consequences that cancer would have for them. (However, the findings of these exploratory analyses require

replication because stepwise multiple regression methods were used, which are more likely to be affected by

chance differences within a single sample). n contrast, beliefs about the likelihood of developing cancer were

not predicted by any of the medical/family history variables that might be expected to influence risk perceptions,

such as the person's "actual (calculated) risk, the number of people in one's family who have had cancer, the

proportion of relatives on the affected side of the family who have had cancer, or having had a sibling with

cancer. Only younger age predicted higher pre- and postcounseling ratings of the likelihood of developing

cancer at any point in the future. Furthermore, none of the medical/family history variables were predictors of

pre- or postcounseling anxiety about developing cancer. This finding may be important information for people

who are training to become genetic counselors to bear in mind. t suggests that one should not make any

assumptions about patients' risk perceptions or the level of anxiety about cancer on the basis of their actual risk

or the facts about their family history.The finding that perceived risk before genetic counseling was significantly

associated with anxiety is consistent with the results of previous studies (e.g., Hopwood et al., 2001; Julian-

Reynier et al., 1999). n the present study, we also examined other beliefs as predictors of anxiety, derived from

a CB model of health anxiety. As expected, beliefs about how negative the consequences of cancer would be

and how well one would cope with cancer were both significant predictors of anxiety. However, relatively

positive beliefs about the likelihood of successful prevention and treatment were not predictive of lower levels of

anxiety, perhaps because the prevention and treatment of cancer can involve methods that are themselves

anxiety-provoking.People with family histories of colon cancer reported significantly lower levels of distress than

people with family histories of breast and/or ovarian cancer, despite no significant group difference in objective

risk. According to cognitive models of anxiety, this is because the colon cancer group had less negative cancer-

related beliefs (i.e., about likelihood, negative consequences, coping ability, and treatment). Factors that may

02 May 2013 Page 19 of 25 ProQuest

contribute to the group differences in such beliefs are the higher level of mass media attention to breast cancer

or the fact that people are more likely to have known people outside their family with breast cancer because it is

more common in the general population.Participants' general tendency to worry about their health also

predicted cancer-related anxiety before and after counseling. However, contrary to expectations, the more

highly health-anxious individuals showed a significant decrease in anxiety at follow-up, whereas those who did

not tend to worry about their health showed no significant change over time. This finding is probably due to the

fact that risk perceptions were reduced significantly in the high health-anxiety group but not in the low health-

anxiety group, perhaps because the high health-anxiety group had previously been overestimating their risk to a

much greater degree.One possible reason for the difference in these findings from those in a previous study of

bone density screening for osteoporosis (Rimes &Salkovskis, 2002), in which health-anxious individuals showed

an increase in anxiety after a high-risk result, is that many of the participants in the osteoporosis study were

volunteering for screening not because they already perceived themselves to be at risk but simply in order to

help research. When those participants were given high-risk information, it was often a surprise and resulted in

an increase in their risk perceptions. n contrast, participants in the present study were already aware of their

increased risk because of their family history and generally overestimated their risk beforehand. Here, they

received new information showing that their risk was usually much lower than their preexisting risk beliefs.

Furthermore, these patients were already in a state of uncertainty about their risk, and the genetic counseling

may have helped to reduce the ambiguity. This point highlights the importance of taking into account the

person's preexisting risk perceptions and state of uncertainty when attempting to understand reactions to health

screening. These factors are likely to differ in population-based screening compared with high-risk population

screening.Although the accuracy of risk perceptions increased slightly, both groups were still generally

overestimating their risk of cancer after counseling, as has been found in other studies. Participants' actual risk

status was not predictive of how they respondedthere was no evidence of greater reductions in risk

perceptions in those who were told that they were at lower risk. n contrast, precounseling risk perceptions were

a strong predictor of postcounseling risk perceptions. This finding indicates that to achieve more accurate risk

perceptions after genetic counseling, it may be necessary to identify and correct the bases for individuals'

preexisting idiosyncratic beliefs, in addition to providing information about their calculated risk. Similarly, to

reduce anxiety about cancer, it may be helpful to address other negative idiosyncratic beliefs, for example,

about one's ability to cope if one developed cancer. Questionnaires such as the one used in the present study

could be used to identify which individuals may be vulnerable to experiencing persistent distress and which of

their beliefs are particularly negative (e.g., risk of cancer, consequences, treatment, one's coping ability, and so

on). The genetic counselor would then need to elicit the precise content and reasons for the individual's beliefs

within the session in order to modify them effectively.An important previous study identifying precounseling

predictors of postcounseling cancer-specific distress found that postcounseling scores on the mpact of Event

Scale (ES; Horowitz, Wilner, &Alvarez, 1979) were predicted by baseline ES scores and that only the less

educated women showed a significant decrease in ES scores (Lerman et al., 1996). Using measures of

precounseling beliefs as predictors of distress, as we did in the present study, means that elevated scores

indicate not only that intervention may be required but the nature of that interventionthat is, which

dysfunctional beliefs need to be addressed. Future studies should combine these approaches, using belief

questionnaires together with well-validated measures of symptoms and sociodemographic variables.

Participants who returned their follow-up questionnaires were less anxious and felt less at risk of cancer before

02 May 2013 Page 20 of 25 ProQuest

counseling than those who did not return the second questionnaire. This finding means that the negative effects

of genetic counseling were probably underestimated in the study. A further limitation is that postcounseling

assessments were only taken at 6 months, and immediate or longer term reactions may have shown a different

pattern of results. The fact that the patients were all seen within a single clinic may also limit the generalizability

of the results. Furthermore, the ethnicity, education level, and social class of the participants were not

assessed, which makes it more difficult to compare these results with those of other studies that may have had

different participant profiles.The questionnaire measures were adapted from measures in a previous study

examining responses to health screening (Rimes &Salkovskis, 2002). Although it would have been preferable to

use well-validated measures, no such measures were available at the time of the study that were brief enough

for use in that context. Similar measures have been shown to be predictive of responses to health screening

and have good correlations with longer measures of health anxiety (Rimes &Salkovskis, 2002). However, in

future research, it will be important to replicate the findings using better validated questionnaires.n services

such as the one studied in the present study, genetic information is offered in a range of ways, varying from

letters about genetic risk and other relevant issues sent to those at obviously low risk to face-to-face counseling

provided to those at ambiguous or high risk. n the present study, we wished to evaluate all of those referred to

the service, that is, those at all levels of risk, so the intervention inevitably contained this range of components.

The applicability of this research to routine clinical practice is strengthened by the study's setting and

methodology.The CB model of health anxiety focuses primarily on the perception of threat (including but not

confined to risk) and the associated emotional responses. ntegral to this theory are behavioral responses in the

form of safety-seeking behaviors, ranging from avoidance of threatening medical information to excessive

reassurance-seeking behaviors. However, the specific prediction of medically important behaviors (e.g.,

preventive and surveillance behaviors) is outside the focus of this model and may well be best viewed from

another perspective. For example, the association between anxiety and health-related behavior change has

been found to be weak and inconsistent in the context of health screening decision-making research (e.g.,

Wroe et al., 1998, 2000), in which another cognitive theory (the modified subjective expected utility theory) may

provide a better account of behavior change.n conclusion, although genetic counseling was associated with an

overall decrease in anxiety about developing cancer, most people continued to overestimate their risk for the

disease and some became more distressed. As predicted by a CB model of health anxiety, individuals'

preexisting beliefs about cancer were significant predictors of distress and risk perceptions after genetic

counseling. t is possible that genetic counseling would result in a greater accuracy in risk perceptions and

larger reductions in anxiety if the bases for these idiosyncratic beliefs were addressed within the consultation. A

CB model of health anxiety has now been shown to be useful in understanding and predicting reactions to two

types of health screeningbone density screening for osteoporosis and genetic counseling for cancer. Further

research is needed to investigate whether it is also useful in predicting reactions to other types of health

screening.

References

1. Audrain, J., Schwartz, M. D., Lerman, C., Hughes, C., Peshkin, B. N., & Biesecker, B. (1997). Annals of

Behavioral Medicine.

2. Bish, A., Sutton, S., Jacobs, C., Leven, S., Ramirez, A., & Hodgson, S. (2002). British Journal of Cancer.

3. Braithwaite, D., Emery, J., Walter, F., Prevost, A. T., & Sutton, S. (2004). Journal of the National Cancer

02 May 2013 Page 21 of 25 ProQuest

nstitute.

4. Claus, E. B., Risch, N., & Thompson, W. D. (1994). Cancer.

5. Cull, A., Anderson, E. D. C., Campbell, S., Mackay, J., Smyth, E., & Steel, M. (1999). British Journal of

Cancer.

6. Grosfeld, F. J. M., Lips, C. J. M., Beemer, F. A., & ten Kroode, H. F. J. (2000). Journal of Genetic

Counseling.

7. Harper, P. (1998). Practical genetic counselling. Oxford, England: Butterworth-Heinemann.

8. Hopwood, P., Shenton, A., Lalloo, F., Evans, D. G., & Howell, A. (2001). Journal of Medical Genetics.

9. Horowitz, M., Wilner, N., & Alvarez, W. (1979). Psychosomatic Medicine.

10. Julian-Reynier, C., Eisinger, F., Chabal, F., Aurrean, Y., Bignon, Y-J., & Machelard-

Roumagnac, M. (1999). Psychology and Health.

11. Kash, K. M., Holland, J. C., Halper, M. S., & Miller, D. G. (1992). Journal of the National Cancer nstitute.

12. Keller, M., Jost, R., Haunstetter, C. M., Kienle, P., Knaebel, H. P., & Gebert, J. (2002). Genetic Testing.

13. Lerman, C., Daly, M., Sands, C., Balshem, A., Lustbader, E., & Heggan, T. (1993). Journal of the

National Cancer nstitute.

14. Lerman, C., Schwartz, M. D., Miller, S. M., Daly, M., Sands, C., & Rimer, B. K. (1996). Health

Psychology.

15. Meiser, B., & Halliday, J. L. (2002). Social Science and Medicine.

16. Miller, S. M. (1987). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

17. Ravine, D., & Sampson, J. (2001). British Medical Journal.

18. Rimes, K. A., & Salkovskis, P. M. (2002). Behaviour Research and Therapy.

19. Rimes, K. A., Salkovskis, P. M., & Shipman, A. J. (1999). Psychology and Health.

20. Ritvo, P., Robinson, G., rvine, J., Brown, L., Matthew, A., & Murphy, K. J. (2000). Patient Education and

Counseling.

21. Salkovskis, P. M., & Rimes, K. A. (1997). Journal of Psychosomatic Research.

22. (1996). Genetics and cancer services. Report of a working group for the Chief Medical Officer.

London: Author.

23. Warwick, H. M. C., & Salkovskis, P. M. (1990). Behaviour Research and Therapy.

24. Watson, M., Duvivier, V., Wade

Walsh, M., Ashley, S., Davidson, J., & Papaikonomou, M. (1998). Journal of Medical Genetics.

25. Williams, E. J. (1959). Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B.

26. Wroe, A. L., Salkovskis, P. M., & Rimes, K. A. (1998). Behaviour Research &Therapy.

27. Wroe, A. L., Salkovskis, P. M., & Rimes, K. A. (2000). Health Psychology.

Show less

Address for Correspondence:Katharine Rimes, Department of Psychological Medicine, Section of General

Hospital Psychiatry (P062), King's College London, nstitute of Psychiatry, Weston Education Centre (3rd

Floor), 10 Cutcombe Road, London, United Kingdom SE5 9RJ

Email:k.rimes@iop.kcl.ac.uk

2006 American Psychological Association

02 May 2013 Page 22 of 25 ProQuest

Subject: Anxiety (major); Cognitive Therapy (major); Genetic Counseling (major); Neoplasms (major); Risk

Perception (major); Genetics; Health

Classification: 3293: Cancer; 3311: Cognitive Therapy

Age: Adulthood (18 yrs & older)

Population: Human, Male, Female

Location: United Kingdom

dentifier (keyword): cognitive-behavioral model, health anxiety, risk perceptions, genetic counseling, cancer

Test and measure: Visual Analogue Scale

Methodology: Empirical Study, Followup Study, Quantitative Study

Author e-mail address: k.rimes@iop.kcl.ac.uk

Contact individual: Rimes, Katharine A., Department of Psychological Medicine, Section of General Hospital

Psychiatry (P062), King's College London, nstitute of Psychiatry, Weston Education Centre, 10 Cutcombe

Road,; (3rd Floor), London, SE5 9RJ, United Kingdom,; k.rimes@iop.kcl.ac.uk

Publication title: Health Psychology

Volume: 25

ssue: 2

Pages: 171-180

Publication date: Mar 2006

Format covered: Electronic

Publisher: American Psychological Association

Country of publication: United States

SSN: 0278-6133

eSSN: 1930-7810

Peer reviewed: Yes

Language: English

Document type: Journal, Journal Article, Peer Reviewed Journal

Number of references: 27

DO: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.25.2.171

Release date: 27 Mar 2006 (PsycNFO); 10 Jul 2006 (PsycARTCLES)

Correction date: 02 Nov 2009 (PsycNFO)

Accession number: 2006-03515-005

PubMed D: 16569108

ProQuest document D: 614445369

Document URL:

https://fgul.idm.oclc.org/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/614445369?accountid=10868

02 May 2013 Page 23 of 25 ProQuest

Copyright: American Psychological Association 2006

Database: PsycARTCLES

02 May 2013 Page 24 of 25 ProQuest

Bibliography

Citation style: APA 6th - American Psychological Association, 6th Edition

Rimes, K. A., Salkovskis, P. M., Jones, L., & Lucassen, A. M. (2006). Applying a cognitive behavioral model of

health anxiety in a cancer genetics service. Health Psychology, 25(2), 171-180.

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.25.2.171

_______________________________________________________________

Contact ProQuest

Copyright 2012 ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. - Terms and Conditions

02 May 2013 Page 25 of 25 ProQuest

Você também pode gostar

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Aporte Al IPSS Del Empleador Por TrabajadorDocumento4 páginasAporte Al IPSS Del Empleador Por Trabajadorvagonet21Ainda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- CABE Space - A Guide To Producing Park and Green Space Management PlansDocumento48 páginasCABE Space - A Guide To Producing Park and Green Space Management PlansbenconnolleyAinda não há avaliações

- Real Number System.Documento7 páginasReal Number System.samuel1436Ainda não há avaliações

- The Perception of Veggie Nilupak To Selected Grade 11 Students of Fort Bonifacio High SchoolDocumento4 páginasThe Perception of Veggie Nilupak To Selected Grade 11 Students of Fort Bonifacio High SchoolSabrina EleAinda não há avaliações

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Case DigestsDocumento12 páginasCase DigestsHusni B. SaripAinda não há avaliações

- Abdukes App PaoerDocumento49 páginasAbdukes App PaoerAbdulkerim ReferaAinda não há avaliações

- Monthly Film Bulletin: 1T1IcqDocumento12 páginasMonthly Film Bulletin: 1T1IcqAlfred_HitzkopfAinda não há avaliações

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- MBA Advantage LRDocumento304 páginasMBA Advantage LRAdam WittAinda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- IHE ITI Suppl XDS Metadata UpdateDocumento76 páginasIHE ITI Suppl XDS Metadata UpdateamAinda não há avaliações

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Ezra Pound - PersonaeDocumento34 páginasEzra Pound - PersonaedanielrdzambranoAinda não há avaliações

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Axe in Pakistan PDFDocumento22 páginasAxe in Pakistan PDFAdarsh BansalAinda não há avaliações

- PDF - 6 - 2852 COMMERCE-w-2022Documento13 páginasPDF - 6 - 2852 COMMERCE-w-2022Anurag DwivediAinda não há avaliações

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- 2.peace Treaties With Defeated PowersDocumento13 páginas2.peace Treaties With Defeated PowersTENDAI MAVHIZAAinda não há avaliações

- Al-Arafah Islami Bank Limited: Prepared For: Prepared By: MavericksDocumento18 páginasAl-Arafah Islami Bank Limited: Prepared For: Prepared By: MavericksToabur RahmanAinda não há avaliações

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- Farewell Address WorksheetDocumento3 páginasFarewell Address Worksheetapi-261464658Ainda não há avaliações

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- Swot Analysis of PiramalDocumento5 páginasSwot Analysis of PiramalPalak NarangAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson Plan Design: Ccss - Ela-Literacy - Rf.2.3Documento6 páginasLesson Plan Design: Ccss - Ela-Literacy - Rf.2.3api-323520361Ainda não há avaliações

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- MLOG GX CMXA75 v4.05 322985e0 UM-EN PDFDocumento342 páginasMLOG GX CMXA75 v4.05 322985e0 UM-EN PDFGandalf cimarillonAinda não há avaliações

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Fish Immune System and Vaccines-Springer (2022) - 1Documento293 páginasFish Immune System and Vaccines-Springer (2022) - 1Rodolfo Velazco100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Chapter 1Documento25 páginasChapter 1Aditya PardasaneyAinda não há avaliações

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Science 7 Las 1Documento4 páginasScience 7 Las 1Paris AtiaganAinda não há avaliações

- Lecture 1. Introducing Second Language AcquisitionDocumento18 páginasLecture 1. Introducing Second Language AcquisitionДиляра КаримоваAinda não há avaliações

- Raro V ECC & GSISDocumento52 páginasRaro V ECC & GSISTricia SibalAinda não há avaliações

- Kinematic Tool-Path Smoothing For 6-Axis Industrial Machining RobotsDocumento10 páginasKinematic Tool-Path Smoothing For 6-Axis Industrial Machining RobotsToniolo LucaAinda não há avaliações

- Automatic Water Level Indicator and Controller by Using ARDUINODocumento10 páginasAutomatic Water Level Indicator and Controller by Using ARDUINOSounds of PeaceAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson 20 PerdevDocumento7 páginasLesson 20 PerdevIvan Joshua RemosAinda não há avaliações

- FABM 1-Answer Sheet-Q1 - Summative TestDocumento2 páginasFABM 1-Answer Sheet-Q1 - Summative TestFlorante De Leon100% (2)

- Trabajos de InglésDocumento6 páginasTrabajos de Inglésliztmmm35Ainda não há avaliações

- Panama Canal - FinalDocumento25 páginasPanama Canal - FinalTeeksh Nagwanshi50% (2)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Evolve Instagram Marketing Guide - From Zero To 10k PDFDocumento132 páginasEvolve Instagram Marketing Guide - From Zero To 10k PDFAnjit Malviya100% (2)