Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Itl

Enviado por

Pritam AnantaDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Itl

Enviado por

Pritam AnantaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

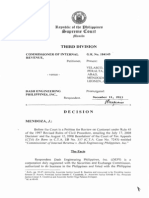

Facts

These appeals/writ petitions raise an important but difficult question concerning the nature of rule or reservation in promotions obtaining in the Railway service and the rule concerning the determination of seniority between general candidates and candidates belonging to reserved classes in the promoted category.The issue is best illustrated by taking the facts in the first of these matters, viz., Union of India and Ors. v. Virpal Singh Chauhan - civil appeal No.9272/95 arising from Special Leave Petition (C) No.6468 of 1987. The appeal is preferred against the judgment of the Central Administrative Tribunal (Allahabad Bench) disposing of Original Application No.647 of 1986 with certain directions. [It was originally filed as a writ petition in the Allahabad High Court which, on the constitution of the Central Administrative Tribunal (Allahabad Bench), was transferred to the Tribunal.] It was filed by, what may be called for the sake of convenience, employees not belonging to any of the reserved categories (hereinafter referred to as "general candidates" - which means open competition candidates). The railway Administration as well as the employees belonging to reserved categories, i.e., Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes were impleaded as respondents. The writ petition/original application came to be filed in the following circumstances. Among the category of Guards in the Railway service, there are four categories, viz., Grade `C' Grade `B' Grade `A' and Grade `A'special. The initial recruitment is made to Grade `C' and they have to ascend rung after rung to go upwards. The promotion from one grade to another in this category is by senioritycum-suitability. In other words, they are "non-selection posts". The rule of reservation is applied not only at the initial stage of appointment to Grade `C' but at every stage of promotion. The percentage reserved for Scheduled Castes is fifteen percent and for Scheduled Tribes 7.5%, a

total of 22.5 percent. To give effect to the rule of reservation, a fortypoint roster was prepared in which certain points were reserved for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes respectively, commensurate with the percentage of reservation in their favour. For Scheduled Castes candidates, the places reserved in the roster were: 1, 8, 14, 22, 28 and 36 and in the case of Scheduled Tribes candidates, they were: 4, 17 and 31. Subsequently, a hundred-point roster has been prepared, again reflecting the aforesaid percentages.

Judgement/Proceedings

In Civil Writ Petition No.1809 of 1972, J.C. Mallik v. Union of India, the allahabad High Court held that the rule of reservation or the forty-point roster, as the case may be, cannot be followed and applied once the representation of Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes in a particular grade, cadre or service, reaches the prescribed level of percentage. In other words, once the quota of 22.5% in favour of Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes is satisfied, the rule of reservation/forty-point roster can no longer be followed and applied. It may be mentioned that this decision has since been referred with approval in the Constitution Bench decision in R.K. Sabharwal v. State of Punjab (1995 (2) S.C.C.745). The other decision of the Allahabad High Court is in Second Appeal No.2745 of 1983 arising from Suit No.308 of 1981, M.P. Dwivedi v. Union of India & Ors. The learned District Judge, whose decision was under appeal in the said second appeal, had decreed the suit filed by the general candidates in the following words: "The defendants- appellants, their agents and servnts are restrained by means of permanent injunction from filling up the posts of higher grade in the category of Guards by way of reservation in favour of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes candidates in excess of fixed by Railway Board. Their claim for declaration to the effect that they are entitled to be promoted to the higher grades in the category of Guards on the strength of their

seniority list prepared by the defendant for Guards Grade-C on their initial grades is also decreed". When the matter came to the High Court, the learned Single Judge, who disposed of the second appeal, held: "After having considered the entireposition I am of the opinion that in thepresent case promotion from grade `A' to`A' Special cannot be made on the basisof reservation so long as Guardsbelonging to Scheduled Castes orScheduled Tribes class in grade 1A'Special are in excess of the percentagereserved for them. The position,however, will always remain fluctuatingand will have to be reviewed by theauthorities from time to time. But theright of Scheduled Castes and ScheduledTribes candidates to promotion merely onthe basis or their seniority-cum-suitability without any reference to reservation will not be barred. As and when percentage of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes guards in grade Scpecial goes down below the requisitepercentage their right to promotion onthe basis of reservation will revive. Subject to this modification the decreefor injunction passed by the Court below is confirmed and the appeals aredismissed." The judgment of the Madhya Pradesh High Court is in G.C. Jain v. Divisional Rail Manager, Central Railway (reported in 1986 (1) S.L.R.588). The passage relied upon by the Tribunal reads thus: "Those SC & ST candidates who have come or been promoted due to reservation quota, having already jumped the queue, cannot be permitted to compete with general candidates for further promotion. They are a special class by themselves and they have only to go tothe reserve quota for further promotion.If the reserve quota is already full inthe next grade, the SC & ST candidates just below that grade in the reservequota will have to wait till vacancyoccurs in the higher grade in thereserve quota. However, we want to make it clear that this will not apply to such SC & ST candidates who on their own in competition with the generalcandidates have atained their present position and not due to reservation,they are entitled to compete further with the general candidates and theywill not be affected for promotion in the general quota even if the reservedquota is full in the next higher grade".

On the basis of the aforesaid decisions and certain circulars of the Railway Board, which will be referred at a later stage, the Tribunal laid down the following principles in Para-26 of its judgment. (We have split up the paragraph into several sub-paras to bring out the several principles distinctly): To clarify the position further we will enunciate the principles ofdetermining seniority in situations as are under dispute here.The basic seniority in grade `C' will be the quiding seniority list forthe cadre of quards.Reservations in promotions would bemade against posts in the grades and not against vacancies. Persons who are promoted by virtueof the application of roster would begiven accelerated promotion but not the seniority.The seniority in a particular gradeamongst the incumbents available for promotion to the next grade will be recast each time new incumbents enter from the lower grade on the basis of the initial grade `C' Guard who gets promoted to grade `B' or from grade `B' to grade `A' and so on will find his position amongst the incumbents of thatgrade on the basis of the original grade `C' seniority.Such persons as are superseded for any reasons other than on account of reservation will be excluded. A personuperseded on account of a punishment or unfitness will count his seniority on the revised basis and not on original grade `C' seniority. The reserved community candidates who are senior not by virtue of reservations but by the position in grade `C' selections which the grade `C' seniority list will automatically take care of, will not wait for reservation percentage to be satisfied for their promotion. They will get promoted in their normal turn irrespective of the percentage of reserved community candidates in the higher grade. Others who get promoted as a result of reservation by jumping the queue will wait for their turn. Reservation will again have to be applied on depletion of the reservation quota in the higher grade to make goodthe shortfalls.

Case comment

The primary question which we are called upon to answer in these five Special Leave Petitions is whether the amended provisions of Article 16(4-A) of the Constitution intended that those belonging to the

Scheduled Castes and Schedule Tribes communities, who had been promoted against reserved quota, would also be entitled to consequential seniority on account of such promotions, or would the catch-up rule prevail. The said question has been the subject matter of different decisions of this Court, but the discordant note was considered and explained by the Constitution Bench in M. Nagarajs case (supra). On account of reservation those who were junior to their seniors, got the benefit of accelerated promotions without any other consideration, including performance. Those who were senior to the persons who were promoted from the reserved category were not overlooked in the matter of promotion on account of any inferiority in their work performance. It is only on account of fortuitous circumstances that juniors who belong to the reserve category were promoted from that category before their seniors could be accommodated. The question relating to reservation in promotional posts fell for the consideration of this Court in Indra Sawhneys case for construction of Article 16(4) of the Constitution relating to the States powers for making provision for reservation of appointments or posts in favour of any backward class of citizens, which in the opinion of the State, was not adequately represented in services under the State. The further question for determination was whether such power extended to promotional posts. This Court answered the questions by holding that Article 16(4) does not permit provision for reservation in the matter of promotion. Further, such rule was to be given effect to only prospectively and would not affect the promotions already made, whether made on regular basis or on any other basis. Accordingly, apart from holding that Article 16(4) does not permit provision for reservation in the matter of promotion, this Court also protected the promotees who had been appointed against

reserved quotas and a direction was also given that wherever reservations are provided in the matter of promotion, such reservation would continue in operation for a period of five years from the date of the judgment. In other words, the right of promotion was protected only for a period of 5 years from the date of the judgment and would cease to have effect thereafter. The matter did not end there. The Constitution (77th Amendment) Act, 1995, came into force on 17th June, 1995. A subsequent question arose in the case of Union of India vs. Virpal Singh Chauhan, [(1995) 6 SCC 684], as to whether the benefit of accelerated promotion through reservation or the roster system would give such promotees seniority over general category promotees who were promoted subsequently. The said question arose in regard to promotion of Railway Guards in nonselection posts by providing concession to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes candidates and it was sought to be contended that the reservation provided was not only at the stage of initial appointment, but at every stage of subsequent promotions. In the said case, the Petitioners, who were general category candidates and the Respondents who were members of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes were in the grade of Guards Grade A in the Northern Railway. On 1st August, 1986, the Chief Controller, Tundla, promoted certain general category candidates on ad-hoc basis to Grade A Special. Within less then three months, however, they were reverted and in their place members of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes were promoted. Complaining of such action as being illegal, arbitrary and unconstitutional, Virpal Singh Chauhan and others moved the High Court, but the petition was transferred to the Central Administrative Tribunal. The Tribunal, inter alia, held that persons who had been promoted by virtue of the application of roster would be given accelerated promotion but not seniority, and that the seniority in a

particular grade amongst the incumbents available for promotion to the next grade would be re-cast each time new incumbents entered from the lower grade on the basis of initial Grade C seniority. This came to be recognized as the catch-up rule. The matter was brought to this Court by the Union of India and this Court confirmed the view taken by the Tribunal. The same view was reiterated in the case of Ajit Singh Janujas case wherein it was held further that by accelerated promotion Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes and Backward Class candidates could not supersede their seniors in the general category by accelerated promotion, simply because that their seniors in the general category had been promoted subsequently. It was observed that balance has to be maintained vis--vis reservation. After the decision rendered in Virpal Singh Chauhans case and in Ajit Singh-Is case, in which the claim of reserved category candidates in promotional posts with consequential seniority was negated, the question surfaced once again in the case of Jagdish Lal & Ors. Vs. State of Hayrana & Ors. [(1997) 6 SCC 538], where a Bench of Three Judges took a different view. Their Lordships held that the recruitment rules had provided for fixation of seniority according to length of continuous service on a post in the service. Interpreting the said provisions, Their Lordships held that in view of the said rules those Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes candidates, who though junior to others in the general category, had got promotion earlier than their seniors in the general category candidates and would, therefore, be entitled to get seniority with reference to the date of their promotion. Their Lordships held that the general candidates by relying on Virpal Singh Chauhans case (supra) and Ajit Singh Janujas case could not derive any benefit therefrom.

This resulted in the vexed question being referred to the Constitution Bench. Of the several cases taken up by the Constitution Bench, we are concerned with the decision rendered in the case of Ram Prasad vs. D.K. Vijay [(1999) 7 SCC 251] and Ajit Singh-II & Ors. Vs. State of Punjab & Ors. [(1999) 7 SCC 209]. Differing with the views expressed in Jagdish Lals case , the Constitution Bench in Ajit Singh-IIs case (supra) affirmed the earlier decision in Virpal Singh Chauhans case (supra) and Ajit Singh Janujas case and overruled the views expressed in Jagdish Lals case (supra). The constitution Bench reiterated the views expressed in Ajit Singh-Is case (supra) that those who had obtained the benefit of accelerated promotion should not be reverted as that would cause hardship to them, but they would not be entitled to claim seniority in the promotional cadre. Quite naturally, the same view was expressed in Ram Prasads case which was also decided on the same day. In the said case, while affirming the decision in Ajit Singh-Is case, this Court directed modification of the seniority lists which had been prepared earlier, to fall in line with the decision rendered in Ajit Singh-Is case (supra) and Virpal Singh Chauhans case (supra). Thereafter, as mentioned hereinbefore, on 4th January, 2002, the Parliament amended the Constitution by the Constitution (85th Amendment) Act, 2001, in order to restore the benefit of consequential seniority to the reserved category candidates with effect from 17th June, 1995. The constitutional validity of both the Constitution Amendment Acts was challenged in this Court in several Writ Petitions, including the Writ Petitions filed by M. Nagaraj and the All India Equality Forum. The Constitution Bench while considering the validity and interpretation as also the implementation of the Constitution (77th, 81st, 82nd and 85th Constitutional Amendment) Acts and the effect thereof on the decisions of this Court in matters relating to promotion in public employment and their application with retrospective effect, answered the reference by

upholding the constitutional validity of the amendments, but with certain conditions. The vital issue which fell for determination was whether by virtue of the implementation of the Constitutional Amendments, the power of Parliament was enlarged to such an extent so as to ignore all constitutional limitations and requirements. Applying the width test and identity test, the Constitution Bench held that firstly it is the width of the power under the impugned amendments introducing amended Articles 16(4-A) and 16(4-B) that had to be tested. Applying the said tests, the Constitution Bench, after referring to the various decisions of this Court on the subject, came to the conclusion that the Court has to be satisfied that the State had exercised its power in making reservation for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes candidates in accordance with the mandate of Article 335 of the Constitution, for which the State concerned would have to place before the Court the requisite quantifiable data in each case and to satisfy the Court that such reservation became necessary on account of inadequacy of representation of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes candidates in a particular class or classes of posts, without affecting the general efficiency of service. The Constitution Bench went on to observe that the Constitutional equality is inherent in the rule of law. However, its reach is limited because its primary concern is not with efficiency of the public law, but with its enforcement and application. The Constitution Bench also observed that the width of the power and the power to amend together with its limitations, would have to be found in the Constitution itself. It was held that the extension of reservation would depend on the facts of each case. In case the reservation was excessive, it would have to be struck down. It was further held that the impugned Constitution Amendments, introducing Article 16(4-A) and 16(4-B), had been inserted and flow from Article 16(4), but they do not alter the structure

of Article 16(4) of the Constitution. They do not wipe out any of the Constitutional requirements such as ceiling limit and the concept of creamy layer on one hand and Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes on the other hand, as was held in Indra Sawhneys case (supra). Ultimately, after the entire exercise, the Constitution Bench held that the State is not bound to make reservation for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes candidates in matters of promotion but if it wished, it could collect quantifiable data touching backwardness of the applicants and inadequacy of representation of that class in public employment for the purpose of compliance with Article 335 of the Constitution. In effect, what has been decided in M. Nagarajs case is part recognition of the views expressed in Virpal Singh Chauhans case, but at the same time upholding the validity of the 77th, 81st, 82nd and 85th amendments on the ground that the concepts of catch-up rule and consequential seniority are judicially evolved concepts and could not be elevated to the status of a constitutional principle so as to place them beyond the amending power of the Parliament. Accordingly, while upholding the validity of the said amendments, the Constitution Bench added that, in any event, the requirement of Articles 16(4-A) and 16(4-B) would have to be maintained and that in order to provide for reservation, if at all, the tests indicated in Article 16(4-A) and 16(4-B) would have to be satisfied, which could only be achieved after an inquiry as to identity. 46. The position after the decision in M. Nagarajs case (supra) is that reservation of posts in promotion is dependent on the inadequacy of representation of members of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes and Backward Classes and subject to the condition of ascertaining as to whether such reservation was at all required. The view of the High Court is based on the decision in M. Nagarajs case as no exercise was undertaken in terms of Article 16(4-A) to acquire

quantifiable data regarding the inadequacy of representation of the Schedule Castes and Scheduled Tribes communities in public services. The Rajasthan High Court has rightly quashed the notifications dated 28.12.2002 and 25.4.2008 issued by the State of Rajasthan providing for consequential seniority and promotion to the members of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes communities and the same does not call for any interference. Accordingly, the claim of Petitioners Suraj Bhan Meena and Sriram Choradia in Special Leave Petition (Civil) No.6385 of 2010 will be subject to the conditions laid down in M. Nagarajs case (supra) and is disposed of accordingly. Consequently, Special Leave Petition (C) Nos. 7716, 7717, 7826 and 7838 of 2010, filed by the State of Rajasthan, are also dismissed.

Conclusion

This case also arises on the question of claim of seniority in higher grade by the reserved candidates who obtained promotion by reservation. Held : Is open to the state to provide that the rule of reservation shall be applied and the roster followed in the matter of promotions to or within a particular category ,the candidate promoted by virtue of rule of reservation shall not be entitled to seniority over his seniors in the feeder category and that as and when a general candidate in the feeder category is promoted ,such general candidate will regain his seniority over the reserved candidate not withstanding the fact that he is promoted subsequent to the reserved candidate .There is no unconstitutionality involved in such a provision.

Você também pode gostar

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Print Application Formuppsc2021Documento3 páginasPrint Application Formuppsc2021Pritam AnantaAinda não há avaliações

- Application Numberdl DilipbhaiyaDocumento1 páginaApplication Numberdl DilipbhaiyaPritam AnantaAinda não há avaliações

- Central Universities Common Entrance Test (Cucet-2020) : Registration SlipDocumento2 páginasCentral Universities Common Entrance Test (Cucet-2020) : Registration SlipPritam AnantaAinda não há avaliações

- Habeas Corpus WritDocumento2 páginasHabeas Corpus WritPritam AnantaAinda não há avaliações

- The Property or Lease Deed Is Executed For A Certain PeriodDocumento2 páginasThe Property or Lease Deed Is Executed For A Certain PeriodPritam AnantaAinda não há avaliações

- 125Documento2 páginas125Pritam AnantaAinda não há avaliações

- Ex Parte DecreeDocumento2 páginasEx Parte DecreePritam AnantaAinda não há avaliações

- Onlinekhanmarket: 2 Indian CultureDocumento8 páginasOnlinekhanmarket: 2 Indian CulturePritam AnantaAinda não há avaliações

- In, The Court of Chief Judicial Magistrate, Gaya - Complaint Case No /2018Documento2 páginasIn, The Court of Chief Judicial Magistrate, Gaya - Complaint Case No /2018Pritam AnantaAinda não há avaliações

- Deed of Dissolution of Partnership FirmDocumento2 páginasDeed of Dissolution of Partnership FirmPritam AnantaAinda não há avaliações

- Central University of South Bihar: Labour and Industrial Law-11Documento4 páginasCentral University of South Bihar: Labour and Industrial Law-11Pritam AnantaAinda não há avaliações

- Central University of South Bihar: Labour and Industrial Law-1Documento4 páginasCentral University of South Bihar: Labour and Industrial Law-1Pritam AnantaAinda não há avaliações

- Central University of South Bihar: School of Law & GovernanceDocumento13 páginasCentral University of South Bihar: School of Law & GovernancePritam AnantaAinda não há avaliações

- FDDI SC Trainee List v1 PDFDocumento44 páginasFDDI SC Trainee List v1 PDFPritam Ananta100% (1)

- Central University of South Bihar: Labour and Industrial Law-1Documento9 páginasCentral University of South Bihar: Labour and Industrial Law-1Pritam AnantaAinda não há avaliações

- CONTENTDocumento1 páginaCONTENTPritam AnantaAinda não há avaliações

- 11 Capital Assets AMD Final For Publishing PDFDocumento64 páginas11 Capital Assets AMD Final For Publishing PDFPritam AnantaAinda não há avaliações

- FDDI SC Trainee List v1 PDFDocumento44 páginasFDDI SC Trainee List v1 PDFPritam Ananta100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- 08 Albay Electric Cooperative Inc Vs MartinezDocumento6 páginas08 Albay Electric Cooperative Inc Vs MartinezEYAinda não há avaliações

- Apr 30 23:59:59 IST 2023 Revanth Naik VankudothDocumento2 páginasApr 30 23:59:59 IST 2023 Revanth Naik VankudothJagadish LavdyaAinda não há avaliações

- Slave Ship JesusDocumento8 páginasSlave Ship Jesusj1ford2002Ainda não há avaliações

- Pressure Vessel CertificationDocumento3 páginasPressure Vessel CertificationYetkin ErdoğanAinda não há avaliações

- Account Summary Contact Us: Ms Angela Munro 201 3159 Shelbourne ST Victoria BC V8T 3A5Documento4 páginasAccount Summary Contact Us: Ms Angela Munro 201 3159 Shelbourne ST Victoria BC V8T 3A5Angela MunroAinda não há avaliações

- The Oecd Principles of Corporate GovernanceDocumento8 páginasThe Oecd Principles of Corporate GovernanceNazifaAinda não há avaliações

- Pre Counseling Notice Jexpo Voclet17Documento2 páginasPre Counseling Notice Jexpo Voclet17Shilak BhaumikAinda não há avaliações

- (ORDER LIST: 592 U.S.) Monday, February 22, 2021Documento39 páginas(ORDER LIST: 592 U.S.) Monday, February 22, 2021RHTAinda não há avaliações

- Commercial Bill: Atlas Honda LimitedDocumento1 páginaCommercial Bill: Atlas Honda LimitedmeheroAinda não há avaliações

- Federal Lawsuit Against Critchlow For Topix DefamationDocumento55 páginasFederal Lawsuit Against Critchlow For Topix DefamationJC PenknifeAinda não há avaliações

- Posting and Preparation of Trial Balance 1Documento33 páginasPosting and Preparation of Trial Balance 1iTs jEnInOAinda não há avaliações

- Payroll Procedures: For Work Within 8 HoursDocumento2 páginasPayroll Procedures: For Work Within 8 HoursMeghan Kaye LiwenAinda não há avaliações

- The Following Payments and Receipts Are Related To Land Land 115625Documento1 páginaThe Following Payments and Receipts Are Related To Land Land 115625M Bilal SaleemAinda não há avaliações

- Test I - TRUE or FALSE (15 Points) : College of Business Management and AccountancyDocumento2 páginasTest I - TRUE or FALSE (15 Points) : College of Business Management and AccountancyJamie Rose AragonesAinda não há avaliações

- Week 9 11 Intro To WorldDocumento15 páginasWeek 9 11 Intro To WorldDrea TheanaAinda não há avaliações

- Basis OF Judicial Clemency AND Reinstatement To The Practice of LawDocumento4 páginasBasis OF Judicial Clemency AND Reinstatement To The Practice of LawPrincess Rosshien HortalAinda não há avaliações

- First Year Phyiscs Ipe Imp Q.bank 2020-2021 - (Hyderad Centres)Documento26 páginasFirst Year Phyiscs Ipe Imp Q.bank 2020-2021 - (Hyderad Centres)Varun Sai SundalamAinda não há avaliações

- Office of The Presiden T: Vivat Holdings PLC) Inter Partes Case No - 3799 OpposerDocumento5 páginasOffice of The Presiden T: Vivat Holdings PLC) Inter Partes Case No - 3799 OpposermarjAinda não há avaliações

- Rohmayati Pertemuan 8Documento5 páginasRohmayati Pertemuan 8Mamah ZhakiecaAinda não há avaliações

- PAS 19 (Revised) Employee BenefitsDocumento35 páginasPAS 19 (Revised) Employee BenefitsReynaldAinda não há avaliações

- ImmunityDocumento3 páginasImmunityEmiaj Francinne MendozaAinda não há avaliações

- Qcourt: 3republic of Tbe LlbilippinesDocumento10 páginasQcourt: 3republic of Tbe LlbilippinesThe Supreme Court Public Information Office100% (1)

- People's History of PakistanDocumento291 páginasPeople's History of PakistanUmer adamAinda não há avaliações

- Lledo V Lledo PDFDocumento5 páginasLledo V Lledo PDFJanica DivinagraciaAinda não há avaliações

- International Protection of HRDocumento706 páginasInternational Protection of HRAlvaro PazAinda não há avaliações

- ChrisDocumento5 páginasChrisDpAinda não há avaliações

- Viktor ChernovDocumento3 páginasViktor ChernovHamidreza MotalebiAinda não há avaliações

- Form - 28Documento2 páginasForm - 28Manoj GuruAinda não há avaliações

- DOX440 Gun Setup Chart Rev 062019Documento4 páginasDOX440 Gun Setup Chart Rev 062019trọng nguyễn vănAinda não há avaliações

- Apostolic Succession and The AnteDocumento10 páginasApostolic Succession and The AnteLITTLEWOLFE100% (2)