Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

BCAS v12n03

Enviado por

Len Holloway0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

311 visualizações78 páginasBulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars - Critical Asian Studies

Direitos autorais

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoBulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars - Critical Asian Studies

Direitos autorais:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

311 visualizações78 páginasBCAS v12n03

Enviado por

Len HollowayBulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars - Critical Asian Studies

Direitos autorais:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 78

Back issues of BCAS publications published on this site are

intended for non-commercial use only. Photographs and

other graphics that appear in articles are expressly not to be

reproduced other than for personal use. All rights reserved.

CONTENTS

Vol. 12, No. 3: JulySeptember 1980

Robin Broad - Our Children are Being Kidnapped

Jose Maria Sison - The Guerilla Is Like a Poet / Poem

Robert B. Stauffer - Philippine Normalization: The Politics of

Form

Robert L. Youngblood - The Protestant Church in the Philippines

New Society

Craig G. Sharlin - A Filmmaker and His Film / Cinema Review

Charles W. Lindsey - Marcos and Martial Law in the Philippines by

D.A. Rosenberg / A Review Essay

Rob Steven - The Japanese Working Class

Nini Jensen - Nakane Chie and Japanese Society / A Review Essay

Ronald Suleski - Ameyuki-san no uta by Yamazaki Tomoko / A

Review

Kenzaburo Oe - A Strange Job / Short Story translated by Ruth

Adler

BCAS/Critical AsianStudies

www.bcasnet.org

CCAS Statement of Purpose

Critical Asian Studies continues to be inspired by the statement of purpose

formulated in 1969 by its parent organization, the Committee of Concerned

Asian Scholars (CCAS). CCAS ceased to exist as an organization in 1979,

but the BCAS board decided in 1993 that the CCAS Statement of Purpose

should be published in our journal at least once a year.

We first came together in opposition to the brutal aggression of

the United States in Vietnam and to the complicity or silence of

our profession with regard to that policy. Those in the field of

Asian studies bear responsibility for the consequences of their

research and the political posture of their profession. We are

concerned about the present unwillingness of specialists to speak

out against the implications of an Asian policy committed to en-

suring American domination of much of Asia. We reject the le-

gitimacy of this aim, and attempt to change this policy. We

recognize that the present structure of the profession has often

perverted scholarship and alienated many people in the field.

The Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars seeks to develop a

humane and knowledgeable understanding of Asian societies

and their efforts to maintain cultural integrity and to confront

such problems as poverty, oppression, and imperialism. We real-

ize that to be students of other peoples, we must first understand

our relations to them.

CCAS wishes to create alternatives to the prevailing trends in

scholarship on Asia, which too often spring from a parochial

cultural perspective and serve selfish interests and expansion-

ism. Our organization is designed to function as a catalyst, a

communications network for both Asian and Western scholars, a

provider of central resources for local chapters, and a commu-

nity for the development of anti-imperialist research.

Passed, 2830 March 1969

Boston, Massachusetts

Vol. 12, No. 3/July-Sept., 1980

Contents

Robin Broad 2

Jose Maria Sison 9

Robert B. Stauffer 10

Robert L. Youngblood 19

Craig G. Scharlin 30

Charles W. Lindsey 33

Rob Stel'en 3g

Nini JellSen 60

Ronald Suleski 66

de 68

Correspondence

Address all correspondence to:

BCAS, P.O. Box W

Charlemont, MA 01339

The Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars is published quar

terly. Second class postage paid at Shelburne Falls, MA 01370.

Publisher: Bryant Avery. Copyright by Bulletin of Con

cerned Asian Scholars, Inc., 1980. ISSN No. 0007-4810,

Typesetting: Typeset (Berkeley, CA). Printing: Valley Printing

Co. (West Springfield, MA).

Postmaster: Send Form 3579 to BCAS, Box W, Charlemont,

MA 01339.

"Our Children Are Being Kidnapped"

"The Guerilla Is Like a Poet"/poem,

Philippine" Normalization": The Politics of Form,

The Protestant Church in the

Philippines' New Society

. "A Filmmaker and His Film"/cinema review.

Marcos and Martial Law in the Philippines

ed. by D. A. Rosenberg/review essay.

The Japanese Working Class

Nakane Chie and Japanese Society/

review essay.

Ameyuki-san no Uta by Yamazaki

Tomoko/review.

"A Strange Job" /short storr trallSlated by

Ruth Adler. . .

The Bulletin ofConcerned Asian Scholars is distributed to

bookstores in the U.S.A. by Carrier Pigeon, a national

distributor of radical and feminist books and maga

zines. If you know of stores that should sell the Bulletin,

ask them to write to Carrier Pigeon, 75 Kneeland St.,

Room 309, Boston, Mass. 02111 U.S.A.

"Our Children Are Being Kidnapped!"

by Robin Broad

The people of Bukidnon* are talking. They whisper their

stories to me-in jeepneys riding, in rivers bathing, in fields

plowing. One story is repeated time and time again. It becomes

their theme: "Our children are being kidnapped," they say.

"Each night during the full moon, some disappear. We hear

jeeps, company jeeps, driving slowly down the road. And,

afterwards, children are missing."

"Why?" I ask each teller. "Why is this happening?"

Different lips mouth similar answers. "It is that big corpor

ation building here," they reply. "It has built bridges that have

killed mermaids," continues one. "It has built buildings that

have disturbed the tree spirits," says another. "Its development

has angered the gods of nature, and so, in return, they demand

human sacrifices from the company owners. They ask for our

children." Sometimes it is Imelda, President Marcos' wife, who

is said to make the contract with the angered mermaids. Some

times the Japanese businessmen, sometimes the American cor

porate owners, sometimes the rich and powerful Filipino fami

lies.

One hears the story whispered over and over again.

Throughout Bukidnon, at each site of a large corporation, at

each big development venture. The story begins to swim in

one's head. Always there. Always the background script for

what one sees happening in Bukidnon.

Is the tale true? On a literal level, perhaps not. But on a

mythical level, undoubtedly so. The people of Bukidnon are

wise. They see what is occurring around them. They see the

destruction that corporations leave in their wake-the ecologi

cal and the human damage. They see the tremendous costs

associated with this form of development. They see the harm to

their land, to their families, to their whole way of life.

The story of sacrifices, of blood offerings, stands as their

theme.

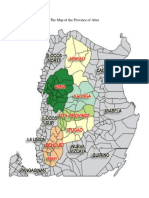

*The province of Bukidnon is located on the island of Mindanao, the southern

most and largest island in the Philippines.

Member of cultural minurity of Bukidnan. Mindanao-dre"cd for

PANAMIN touri,t ,how Photo by R. Broad.

Take one case, that of Del Monte's local affiliate, the

Philippine Packing Corporation (PPC):

In the 1920s, Del Monte's Hawaiian plantation seemed

threatened by a plague of insects, and it sought the security of

greener pastures elsewhere. In 1926, Del Monte began its pine

apple plantation on about 10,000 hectares of land in Manolo

Fortich, Bukidnon. Within four years, a cannery was opened

nineteen miles away in Cagayan de Oro.

The terms of the plantation lease could not have been more

inviting. Although by Philippine law a private corporation may

~ w n only 1,024 hectares, the National Development corpora

tIOn (NDC) was formed by the Philippine government to hold

public agricultural land in excess of this amount for the corpora

tion. PPe's lease with NDC, signed first in 1938 and later

renewed in 1958 for thirty more years, required it to pay a

nominal rental fee, based on the value of raw pineapple pro

duced. Most of PPe's profit, however, is made on its canned

goods, not on the raw pineapple. Moreover, the price pegged for

this computation is 12 pesos* per ton- the 1938 value.

PPC grew. And grew. And grew. By the 1970s, it stood as

the largest food company in the Philippines and as the number

one exporter of pineapples and bananas, two of the Philippines'

top ten foreign exchange earners. Its plantations now yield

tropical fruits, tomatoes, cucumbers, and asparagus, as well as

2

bananas and pineapples. Eight hundred hectares of land in land speculator who had never seen the piece of land he claimed

central Bukidnon grow PPC rice on what is considered to be one as his own,

of the most successful largescale rice growing operations in the

Philippines. ** One of the country's biggest cattle feedlots be

longs to ppe.

With all this, by 1974, PPC, the 37th largest foreign

controlled corporation in the Philippines, was looking to expand

out from its original plantation. PPC's goal was the 14,000

hectares of the Pontian Plain in the municipality of Sumilao,

Bukidnon. The plain, lying just east of the original plantation,

had been partially under ranch lease, but, by the sixties, was

subdivided and released for agriculture. PPC moved in quickly.

The land survey commenced in 1974, and in 1976 the corpora

tion launched operations. A road to the area was started, and

planting began. By 1978, 6,000 of the 14,000 hectares were

PPC's; two thirds of this were already planted with pineapples,

tomatoes and papaya.

PPC seemed set on even further growth.

At the same time, the Pontian Plain remains the site of 5

barrios (Vista Villa, Ocasian, Puntian, San Roque, and Kulase)

with a population of371 families, 80 percent of whom are native

Bukidnons, one of the cultural minorities. t The families claim

the very land on which PPC workers are planting their pineapple

suckers: 371 families, 2259 individuals.

These are the statistics, the bare facts. Figures are im

portant to the story, but they miss much. The real story is a story

of the natives and their fight against this growth, against a type

of development that refuses to consider them as more than mere

statistics. These are families like yours and mine. That man who

works his land-he is a man like your father. His hands callous

like yours and mine do. That crying child sheds tears like you

and I. That woman-she is a mother with all the fears, the

worries, the love that your mother had.

It is a story of people like Carlito Sumagpi.

A horse stops outside the house in San Roque. A man,

young. and slender, walks inside. He looks directly into our

faces. "How can you help me?" he asks.

This, Carlito Sumagpi. Carlito who has been farming six

hectares of land in San Roque under tax declaration since 1966.

It was his hands that toiled over the two hills of jackfruit, the

fifty hills of bananas, the one marange, four avocados, and corn

and abaca. This, his cultivation, his life since 1966.

Carlito knew enough to apply to the Bureau of Lands for a

title, and he did so repeatedly. His first attempt was turned

down. At 17, he was too young to be a titled land owner. But

once he was no longer too young, the rejections still came. And

PANAMIN (Presidential Assistant on National Minorities),t

supposedly set up to aid natives like Carlito, was no help either.

In the meantime, the land was titled in 1975 to Ramon Gaspar of

Kisolon, Sumilao, who in turn leased it to ppe. Ramon Gaspar?

"A notorious land speculator;' comes the answer from a mem

ber ofthe Kisolon Sangguniang Bayan. A land speculator whose

lawyer just happened to be the very lawyer employed by ppe. A

* At the time of writing (1979), US $1 = 7 pesos approximately.

** This is in keeping with the Corporate Farming decree, issued on May 27,

1974, requiring corporations with 500 or more employees to grow or purchase

Carlito fought. He filed protest after protest with the Ma

laybalay Bureau of Lands, always receiving promises of action,

but, in reality, always finding inaction.

PPC waited until January 14, 1978, to move on its claim,

On that day, Max Magdaleno, a PPC canvasser, and two secur

ity guards came to Carlito' s field to begin the pineapple cultiva

tion on four hectares, Carlito approached them, questioning.

"PPC orders," was the reply. Carlito begged them to stop, to

wait for a Bureau of lands decision on his protest. "PPC or

ders," was the reply.

Carlito plowed off his own land.

"How can you help me?" he repeats. We walk to his field,

to see the land that he plowed only to have it replowed by PPC,

to see his house, his fruit trees, his corn plants. He stops in front

of a patch of green onion plants. "Take them!" he says dis

gustedly to some of the barrio girls who have accompanied us.

He points to the onions. "You might as well take them."

These are now PPC fields, these four hectares. PPC's, by

matter of force.

Carlito talks of using force to retake what is his, of planting

corn in the PPC furrows. PPC, however, lets it be known that it

has put chemicals in the soil that will kill the corn seed. Corn

seed is precious. And so the four hectares sit, waiting for

pineapple suckers to be planted.

Yes, PPC has offered to pay Carlito for his "improve

ments" (house, fruit trees, and the like). A thousand pesos or so

for all his sweat. Carlito snickers. It is his land he wants, not the

money. "If I have land, I can always take care of myself."

Carlito's land-his child-has been kidnapped.

As has the land of others. The statistic of 2259 indi viduals

in the PPC expansion area doesn't tell much. But with each, one

finds another tale of exploitation.

You people, you there behind the statistics, you come to

tell your stories.

Wilfred Marquez, you who have returned to your farm in

Vista Villa only to be held at gunpoint by PPC guards and

charged with the theft of your own corn. It is PPC land now, my

friend. It has been taken. And should you try to return again,

you will be shot. Are you content now with your job as a

part-time laborer at PPC? You, who labor on their land, while

their pineapples grow on yours.

You, Mr. Jeremis, man of twenty-two, you who have

toiled at San Roque for the past eight years of your youth. Where

is your house now? Carried off by PPC personnel so they could

cultivate your land, was it? After all, PPC did lease those six

hectares from a land speculator, and they did pay you 1,500

pesos for your improvements. What more could you want, my

friend?

Alena Listohan, you young orphan, you who inherited four

hectares of the plain from your parents. What has happened to

your inheritance now? How did Vicente Cadigan, PPC security

guard, obtain the Bureau of Lands title to your land, your

t Approximately two-fifths of the Mindanao-Sulu population of over 10 million

belong to the cultural minorities.

enough rice to feed their employees. Companies like PPC are finding that this

:;: PANAMIN is headed by Manuel Elizalde. a member of one of the live

can indeed be profitable.

wealthiest families in the Phi lippines.

3

parents' one gift? Ah, Alena, driven off your land to watch

pineapples planted in your wake.

You, Julianna Pasuelo, were you surprised when you re

turned from visiting your daughter that day, when you returned

to discover that the com you had planted on the three hectares

you rented from the farmer Sumanghid was no more, and that in

its place was brown soil, freshly plowed by PPC? Didn't the 500

pesos the farmer gave you soothe you? You, my friend, do you

think the farmer should have warned you in advance that he was

renting the land that was your life?

Sergio Paelden, you whose thirty years were ended by the

shots of three Sumilao policemen. Why were you walking

towards the municipal hall that day? Why did you clutch a bolo

(knife) in one hand and a plastic bag with your land papers in the

other'? Could it be that you were angry, my friend, angry

because your land at San Roque had just been leased to PPC by

another person?

You, farmers of Vista Villa, you whose com was trampled

by 400 head of PPC cattle. You had refused to lease the land to

PPC. And so PPC fenced its cattle nearby, and the cattle "es

caped" to wreck your crops. You, do you believe that a com

pany like PPC doesn't know enough to use steel bars for its

fences? Angered, you filed a complaint against PPC and the

absentee landlord, Jose Neri, charging harassment and unfair

labor practices. You three farmers, did you begin to feel help

less and powerless in your fight against PPC? Is that why you

eventually dropped the complaint and accepted the consolation

prize of 3,000 pesos and job promises that PPC offered you?

You, my friends, are you content, or do you miss the land that is

yours?

You, Fedal Suminao, you who have plowed your six

hectares since 1946. You who keep plowing, waiting, expecting

PPC to pounce. You, one of the ten men from San Roque who

say they will stand up to ppc. Ten against the power of a

multinational corporation intent on expansion. Ten who, like

Carlito, are kept alive by their land, not by money.

You, who live on the land, who as tillers ofthe land should

own the land. While instead Bureau of Lands hands out the land

titles under Free Patent or Homestead applications to others,

others who have never even seen that land- to Tirso Pimentel,

for instance, the Provincial Land Assessor, or to Jaime Pilotion

and Cadigal, PPC employees, or to persons working for the

Lims, those land speculators from Cagayan de Oro City. You

farmers to whom PPC offers to pay only for "improvements,"

if they offer to pay you anything at all before they push you out.

How much can you take, my friends? How much before you

explode?

On October 21, 1975, Higinio P. Sunico, the Chief of the

Land Management Division of the Bureau of Lands in Manila,

wrote a letter to the Sumilao "Sangguniang Bayan" (elected

assembly). From Manila, came the words:

According to investi{?ation ... about 70% o/lands in San

Roque are left abandoned; most ofthe lots are applied for by

absentee applicants; the abandoned lots are presently oc

cupied by persons other than the applicants; and some lots

are titled but unattended by the owners.

The letter continues, ending with a recommendation that:

. . . applications filed by absentee applicants be cancelled

and the lands covered thereby be allocated to the actual

occupants. Steps are now being taken by this Office to cancel

those applications accordingly. Regarding the entry and

occupation by some people on abandoned lots without the

consent and knowledge of the owners thereof. it is informed

that such act may be subject to further court litigation.

The words sound good. But they remain merely words,

like the words of various resolutions by the Sangguniang Bayan

itself.

On February 26, 1976, for instance, the Provincial Sang

guniang Bayan of Malaybalay passed a resolution ordering PPC

to ' 'temporarily suspend fencing of their rented lots and to pull

out temporarily existing fences giving way to the occupants to

cultivate in the meantime pending settlement of the conflict. "

Words.

On March 25, 1976, Felix Dela Cerna introduced a resolu

tion to Ferdinand Marcos in the Municipal Sangguniang Bayan

of Sumilao. The resolution was to decree capital punishment for

land speculation. The resolution passed, but the penalty was

changed from "capital punishment" to "a stiff penalty."

Words.

On April 20, 1976, the sixty families of the Barrio Pontian

condemned the Municipal Sangguniang Bayan for not imple

menting the resolution it had passed to limit PPe's expansion

area to 5,000 hectares. The people had come to know the futility

of such words, the meaninglessness of such promises. "Mayor

Sumbalan [of Sumilaol has connections with PPC," they whis

per. "There will always be words and no action."

Words can soothe a population for only so long.

The pressures on the small farmers of Sumilao are great.

They are pushed. They are shoved. Those who refuse to move

face the threat of having their rights-of-way cut off by PPC.

Those who continue to try to get land titles through Bureau of

Lands are told they must wait, or that they have no witnesses, or

that they are lacking the proper forms, or that their lands have

already been applied for, and, eventually, that they will be given

titles only if they promise to lease to ppc. And there in the title

of the land it says just that: I am the tiller and occupant of this

land provided I lease to Philippine Packing Company.

What about those who finally sign the lease, the Crop

Producer and Grower's Agreement? Their signature is affixed to

a ten page document of such intricate English that it is highly

unlikely that any know what they are signing. PPC can afford

the best legal minds, and the Crop Producer and Grower's

Agreement is testimony to their brilliance. In 25 paragraphs, the

lawyers produce what is in effect a lO-year lease, with PPC

maintaining the sole option to extend for another 16 years. The

lease does permit the farmer to grow the pineapple himself and

sell it to PPC for a share in the profit-provided he can meet all

of PPe's specifications. It is, however, the "producer" (PPC)

that "shall be the sole judge as to the amount and suitability of

equipment and labor and materials necessary and other im

provements required for an efficient and economical agricul

tural operation." And what small farmer has the capital or the

experience to do this? Who has the money to build a road if PPC

says it is needed? Who can afford the high-priced fertilizers PPC

deems necessary?

4

Should the grower discover he cannot meet these specifica

tions, he is directed to a letter that is attached to the Agreement.

There he signs a statement saying that the Agreement has' 'just"

been concluded "but due to the technical ability involved to

grow these crops and the sizeable amount of finances and

equipment needed, I cannot comply and meet this particular

condition. In view of this, I am giving the Company or your

representative the absolute authority to take over the entire

area ...

"

Clearly, PPC expects this letter to be signed. "Do you ever

buy pineapples from individual farmers?" I ask Henry Reyes of

the PPC Research Department. "Oh, no," he laughs. "Ba

nanas sometimes, but never pineapples. They don't have the

technical expertise." "What about this profit sharing?" I ask

Angel lavellana, a top PPC executive. "Oh that," he laughs.

"That's just for legal purposes. No farmer would understand

those terms. In fact, when we talk to them about the agreement

in the local dialect, we use the word that means lease. We're

really renting the land."

Without any real profit sharing, the people are given little

for their land. Two hundred pesos per year per hectare of arable

land, and 2 pesos per hectare of nonarable land is the price the

contract eventually sets. PPC, of course, is the sole judge of

what is defined as arable and what nonarable. And so, in San

Roque, one can see slightly sloping lots that have been classified

as nonarable, supposedly to be used as rights-of-way, but,

indeed, planted with just as many pineapple suckers as adjacent

flat areas classified as arable.

Again and again in the Agreement, the producer is given

the sole right to judge. The grower's books may be subject to an

audit by the producer's representatives. The producer's books

are completely restricted from the growers. The producer has

the right to terminate the contract at the end of any cycle.

Moreover, should "regulations or restrictions of any govern

mental authority" bind him, the producer may "be excused

from performance by reason of inability to perform:' The cards

are all stacked in favor of the producer. The grower gets little

except the right to continue paying the property taxes. And yet,

either not knowing better or not seeing himself as having any

other choices, he, the owner and tiller, signs.

But he does not merely sign the Agreement and the cover

letter. He also signs the bottom of eight blank pages. These are

for a map of your land, he is told by the representatives of the

company. The blank pages are perplexing. Why not have the

map drawn before the paper is signed? Why must it be a true

signature and not just a label by PPC? Why must it be signed at

the bottom of the page, and not at the top? The farmers, not

knowing better, sign, sign without questioning. Will the pages

be filled with lease extensions in later years? One can only wait

to see. "Not only have you just signed your land away,"

explains a local priest, "but you have signed away your wife

and seven children. "

Yes, your children are being sacrificed.

And you are being turned out from your land to join a

population of landless agricultural laborers.

Another family wants to tell tales of PPC and its land

grabbing expansion. Another Bukidnon farmer, trying to feed

his family from the Pontian Plains.

I go to the house to talk, to hear the story. It is night, the

dark, quiet night that those with electricity will never know. We

sit and drink coffee and eat rice cakes. Around us, the children

play. We sit and talk, But this time everything about PPC is

described as being wonderful. This time, there seem to be few

problems, few irregularities. This time, PPC seems the farmers'

friend.

I rise to leave. The farmer motions to a teenage boy who

comes toward me. "This is my nephew," the farmer says. "He

is visiting us. His father works for ppc."

The pieces fall into place. The people are scared. They

know PPe's power. They know it all too well. And they are

scared, some of them. Understandably, they are scared.

The PPC officials sit at their desks in a compound of white

buildings behind a tall fence at Camp Phillips, Manolo Fortich. I

pass through the gate and by the unifonned security guards.

Today I will be given an official tour of the PPC grounds. "Only

San ROljue. Bukidnan: subsistence farm in area "here DelMonte is

expanding (Broad).

because you're a young and beautiful girl-and negotiable,"

one of the secretaries confides to me. "You know, they

wouldn't do this if you were a boy. "

The Red Ford pickUp truck takes me first to the pride of the

PPC executives-Cawayanon, the executive compound. Large

suburban-type houses painted pretty colors sit behind plush

green lawns. One or two cars are parked in each driveway. We

pass the homes slowly. My guide is the most talkative here.

"This is Mr. Moran's house ... This is Mr. lavellana's house

. . . This is. . ." We stop at the clubhouse to watch the golfers

tee off. And back again past the homes. "This is Mr. Javellana's

house," my guide reminds me. "This is Mr. Moran's house

. . . This is ... " The compound is tightly guarded. It is

undoubtedly supposed to be the highlight of my tour.

We drive more quickly through the other housing areas. At

each, the buildings get smaller and smaller. The fancy exteriors

fade to weathered wood. The lawns disappear. Driveways be

come fewer. Cars are not to be seen. Electlic lines are no more.

5

The homes stand in neat rows, as if on graph paper, closer and

closer together. One can guess the level of the workers in each

compound. Here, the supervisors. Here, the office staffs. Here,

the drivers. Here, the field laborers.

The truck turns onto the grid of dirt roads that pass through

the plantation-through pineapple plants as well as papaya,

tomatoes, and other vegetables. The workers are in big straw

hats and netted masks, their faces hidden. They stoop over,

weeding, picking, checking. "Progre'ss," my guide notes suc

cinctly. He points to the line of workers, throwing the picked

pineapple from one to the other until it reaches the truck bed.

And then he points to another set of workers who follow a large

vehicle with wide wings of conveyor belts. The boom harvester,

PPe's newest joy. The workers bend over, plucking the pine

apple, placing it on the conveyor. No more tossing back and

forth from one to another. Mechanization. Speed. "Progress."

It is hot in the truck, much hotter outdoors. I look up to the

noonday sun. I watch them, bending over time and time agai.n.

The more fortunate receiving the minimum wage, I. II pesos an

hour. And only that for fulltime workers. Most of those outside

sweating receive the pay of the casual worker, less than 7 pesos

a day. But they and their families still have to live, a cost the

National Economic Development Authority (NEDA)* esti

mated in 1976 to be 45 pesos per day for a family of six.

My guide looks at his watch. "Too late," he notes. We do

not have time to travel through the pineapple plants to San

Roque, to the site of the expansion area. "Too bad," he says.

"The sunset is beautiful there."

You do not really want to talk to the workers, " the parish

priest at Camp Phillips has told me . 'They are biased. They will

not tell you the truth. If you want to know the facts, you must go

to the PPC office. "

The executives sit there, behind their desks, sit there

amidst all kinds of bound volumes filled with information that

they clearly have been instructed not to divulge to outsiders.

"How many workers do you have here at the plantation?"

I ask Angel Javellana who is in charge of the expansion program

in Sumilao.

Mr. Javellana, dressed all in white, smiles from behind his

desk, and explains that he's not very good at remembering

figures. The books remain closed. Both cattle and people are

under his domain, and he confesses, "I forget if I'm counting

heads of cattle or people. "

"How many hectares do you have here at the plantation?"

I ask time and time again.

It is a secret-highly confidential information. The figures

stay hidden within the pages ofthose books. "Oh, I don't really

know, maybe about 5,000 hectares," offers lavellana . , 11,000

arable hectares," says Marcelino Chan, Senior Department

Head of the Research and Development Division. "12,000

hectares owned and 4,000 more leased," guesses Henry Reyes,

one of the men in Chan's department.

And the expansion area?

"About 1,000 more hectares of arable land," Reyes says.

"I'm not good at statistics," Javellana repeats. "Maybe about

4,000 more hectares." He goes to a map on the wall to point out

the Ponti an Plain area, and explains to me why the whole

landgrabbing story is false. As he sees it, if his company were

* NEDA is the highest economic planning body in the Philippines.

really landgrabbing it would already control the whole contigu

ous area. But it doesn't. There are still individual farmers

scattered here and there. Point proven: PPC is not landgrabbing.

Wage levels?

., Most people are in the bracket above two pesos an hour, "

Reyes summarizes, after explaining the three categories of

workers-fulltime regulars whose base pay, as of April 16,

1978, is 1.64 pesos per hour, intermittent regulars whose base

pay is 1.50 pesos per hour, and seasonal regulars whose base

pay is 1.25 pesos per hour. No mention of the nonregular labor,

the casual workers, who make up 3,000 of the 5,000 plantation

workers. Three-fifths of the labor force, three-fifths whom PPC

executives find so easy to dismiss from their minds.

As Javellana sees it, the base pay for the regular workers is

1.54 pesos per hour. He explains that the base wage must be

negotiated with the union. "Don't say this too loudly, " he adds,

explaining one aspect of the labor situation in the Philippines

that is beneficial to PPC, "but, unlike the United States, we

don't have to negotiate anymore than this [the base pay]."*

The subject of wages is quickly changed. After all, what

are mere monetary wages that do not take into account all the

nonmonetary benefits for which a worker at PPC is eligible?

J avellana expounds on these: housing. . free water ... power

allowance ... subsidized schooling ... hospital (free up to a

certain point) ... pension....

"Do all workers get housing?" I question.

No, it turns out. Not really. PPC, you understand, has

expanded and a shortage of housing has resulted from this

growth. "Sound investment policy," Javellana explains. It just

would not be economically wise to put too much money into

new housing all at once. So, for example, only 24 homes in the

supervisors' compound are available for 45 eligible families.

Those left out will be given housing in the next lower' level

enclave. And the extra from there will be placed back one more

level. And so on, until it is the bottom segment of laborers who

are left without housing. "Many of them do not want to live here

anyway," Javellana offers. "They like to live in their own

barrios where they have always lived." Problem solved in his

mind. But what of the inequality of salary that thus results? The

lowest paid get the least benefits-no housing, no free water,

no power allowance.

What of legal arrangements with the Philippine

government?

Each man mentions the Laurel-Langley Agreement, the

Parity Agreement, which gives Americans the right to own land

in the Philippines. ("They gave us our independence and we

gave them this in return," goes the saying.) "It's just expired, I

think," says Reyes, "but (there are) exceptions for some com

panies, of course."

And the lease agreement with NDC that expires in 1988?

Javellana chuckles. He's not worried about that one. After

all, 'TII be retired by then. "

* A study by the accounting finn Sycip, Gorres, Velayo and Company com

pares the cost of labor throughout Southeast Asia. In almost every occupational

classification. the wages in the Philippines were the lowest. This low level of

wages has undoubtedly been strengthened by General Order #5 of 1972 which

prohibits strikes, assemblies, and collective bargaining.

6

Philippine Packing office again. Once more inside the tall, In March of 1978, it happens. Javellana and six others*

w'ell-guarded fences. To another desk in another department. come to San Roque. There is an air of temerity in the group of

"Asparagus," says the man behind this desk to me. He farmers who await them. Some Tanduay rum has flowed. Some

shame is put away. Some feeling of powerlessness leaves.

Together, there can be strength, even against ppc. The group

from Sumilao is ready.

"We demand to know your connections with the Bureau of

Land," says one of the 25 San Roque residents present. He

laughs aloud.

"And Carlito. We demand justice for Carlito." lavellana

looks to Carlito, asking his yield per hectare. "One kaban,"

Carlito answers honestly. He is promised compensation for that.

But money was not what Carlita Sumagpi wanted.

More demands come. "JavelIana's lips kept trembling,"

one observer tells me. Is it true? It does not matter really. All

that is important is that in the people's eyes they were trembling.

The people grew in stature and strength in their own view

grew enough to make a PPC official's lips tremble.

"It is an American company," Javellana repeats over and

over again, as if wiping away all blame.

Results of the confrontation? Answers to the petition the

people presented to the PPC representatives that day? As yet,

there is little in terms of concessions by PPC. But promises of

more confrontations. And the roots of solidarity among the

farmers of San Roque.

Outside the window, the barrio people weed the com. One

man sings a beautiful Visayan song, "Ngano?" "Why are my

people suffering?" it asks. He sings, seemingly to himself, but

really to the others.

He sings. And then there is silence.

"How do we get united?" he asks the people around him.

"In heaven," answers an old woman, bent over, hacking

at the weeds.

"But how do we get to heaven?" he asks.

There is silence. The people move about the rows ofthe tall

plants. Looking to each other. Silently.

"No," the man continues. "It has to be here. It must be

through acts here. "

There is silence. And then it is strains of "Ngano?" that

again fill the air. But this time, he does not sing alone.

Another man. Another pair of tattered pants. Another

"Bukidnon My Home" t-shirt. Another pair of calloused

palms, of muscular arms. Another pair of mud-stained feet.

* Included in the PPC contingent were Villanoy, the assistant to Javellana in the

Sumilao expansion program; Macaranas, in ~ h a r g e of feed operations; Abella,

the Barrio Development head; Magdaleno, an ex-barrio captain; and the canvas

ser and security guard from Vista Villa.

,

Dole

....

I

looks at me seriously, solemnly, and explains his dilemma. It

seems that PPC has begun to grow asparagus for the local

market. But, somehow, Taiwan asparagus is being imported to

the Philippines and sold more cheaply. "Smuggled in illeg

ally, " he suggests.

He continues, for this is only part of the asparagus prob

lem. "Filipinos do not yet eat asparagus very much." He looks

to future advertising campaigns to change this unhappy fact.

1 "Indeed," he muses, "Why shouldn't they eat asparagus every

d

ay.

?"

We talk further of advertising and of the awards PPC has

won for its past advertising campaigns. He points to an ad

posted on the cabinet door-a blonde-haired, dungaree-clad

woman lounging amidst the green; a Del Monte insignia in the

lower corner. He smiles. Perhaps there is hope for the aspara

gus market yet.

PPC's other markets present little problem. In fact, at 33.4

percent, its profit rate is extraordinary. The bulk of its money is

not made in the local markets but on its exports. Fresh pineapple

is shipped to Japan, while most of the canned product ends up in

Europe or the United States. Two out of every three cans of

pineapple in the United States are from the Philippines. And

what of the IO percent of PPC's goods that are sold locally?

Well, Del Monte appears to have few problems here either.

After all, those cans on the local shelves include the ones that

would not meet foreign health standards.

I

I

Still another family.

The father sits beside me. A man of some twenty-nine

years. Of dark skin. Dark penetrating eyes. He sits there,

I

wrapped in Muslim cloth, wrapped against the cool mountain

air. A Bukidnon like Carlita. A Bukidnon like the majority of.

the people who are being pushed by ppc.

"I am teaching my daughter irreverence," he tells me.

I look at him silently, questioningly.

"I can give her little," he continues. "I am poor. My

people are poor. But my heritage, my culture, must survive.

And so I give her irreverence. Because my people have been too

filled with shame to fight. They have felt too inferior to other

peoples to push back. And so I teach my daughter irreverence.

So she will stand up and fight for what is hers and what is ours."

The people of San Roque become angry. With anger comes

more boldness. They demand a confrontation with PPC officials

in charge of the expansion area, demand that these officials

come to San Roque to hear what they, the people, have to say.

D61e

CONTAINS CRUSHED PINEAPPlE AND PINEAPPlE JUICE

DISTRIBUTED BY CASTLE I COOKE FOODS

SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94111

ADIVISION OF CASTLE COOKE INC. !

HONOLULU. HAWAII 9lI802

PACKED AT DOLE PHllIPI'INES INC.

POLOMOL OK. SOUTH COTABATO

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES

pqODUCT OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES

7

NUTRITION INFORMATION

PER SERVING SIZE 1CUP WITH JUICE; CONTAINS APPROX I SERVING.

CAlORIES 140 CARBOHYDRATES 35 GRAMS

PROTEIN 1GRAM FAT . 1GRAM

PERCENTAGE OF U.S RECOMMENDED DAILY AlLOWANCES (U.S. RDA) a

PROTEIN .. * RIBOFLAVIN 1%

VITAMIN A 1'1, NIACIN 2%

VirAMIN C 10% CALCIUM 1%

THIAMIN . 10% IRON .. '. 4%

*CONTAINS LESS THAN 2% OF THE U.S. ROA OF THIS NUTRIENT.

Another set of eyes filled with frustration and fatigue, flashing

with anger as his words begin.

"We, the people, give them a whole full platter," he says

of the encroaching corporation. "We serve them a full platter,

heaping full, for them to feast on. And what do we get in return?

One small measly teaspoonful. "

This time, the teaspoonful of which he talks is given not by

PPC, but by another of the agribusinesses invading the cultural

minorities of Bukidnon. That is, PPC is not an isolated case.

Unfortunately, there are others who repeat the saga of ppe.

The man talks of the Construction and Development Cor

poration of the Philippines (CDCP). In 1974, CDCP bought an

old ranch in Don Carlos, Bukidnon. The government changed

the lease from a pasture lease to an agricultural one, and CDCP

began growing rice and com under the Corporate Farming

program. It also kept livestock, and, by 1976, was growing

sugar for the nearby Bukidnon Sugar Corporation (BUSCO).

Like PPC, CDCP soon began to itch for expansion. It

increased its holdings to 4,000 hectares. This next year another

1,000 hectares is to be added. The expansion program hit

Maraymaray, a barrio of 80 families and 2,000 hectares. And

there, one sees the landgrabbing tactics of these big develop

ment ventures at work once more. It was the barrio captains that

COCP bought off to canvas the people and convince them to

leave their land. After all, they were told, it is useless to stay:

COCP will control all rights-of-way; you farmers will need a

pass to go through; you just won't be able to continue farming

here.

Not surprisingly, CDCP was able to acquire much of

Maraymaray. Its renting price was between 200 pesos and 250

pesos for the first year, with the promise of a yearly increase.

Most people, however, opted to sell the land-at CDCP's price

of 1,500 pesos per hectare for titled land and 1,000 pesos per

hectare of land untitled but under tax declaration-rather than

rent. Like PPe's Crop Producer and Grower's Agreement,

CDCP's conditions of rent made the people uneasy. The com

pany appeared to be given all the power. For example, ifCOCP

chose to install improvements on the rented land, it seemed

virtually impossible for the farmer to get out of the rental

agreement.

And so they sold. Except for twenty families, twenty who

will stand up and fight for what is rightfully theirs.

There is also talk of the San Miguel Corporation* coming

into Sumilao to grow coffee, although some say it is being

scared off by what it sees happening nearby at PCe's expansion

area. San Miguel has, nonetheless, already acquired 200 hec

tares. Estimations are that the company needs a total of 2,000

hectares before its operations would be profitable. It seems that

San Miguel is impressed with the success of PPe's leasing

contract, and would like to use something similar. In fact, word

has it that San Miguel is trying to get its hands on a copy of that

very Crop Producer and Grower's Agreement so it too can profit

from the legal minds at PPC.

A $48 million sugar mill with about 23,000 hectares for

milling contracts has also made its way into Bukidnon. This is

the Bukidnon Sugar Corporation (BUSCO), supposedly owned

by Robert Benedicto, although it is rumored that behind

Benedicto is Marcos himself. With BUSCO comes one more

national development project that is depriving the cultural mi

norities, this time the Manobos of southern Bukidnon, of their

lands.

In March 1976, twenty-five Manobo families were evicted

and brought to the Quezon parish school. Theirs is a story of a

weary fight against the powers of large corporations. The farm

ers had long lived in Barrio Butong in Quezon. Some were born

on those lands; others had tilled the soil for over 20 years. The

land. they thought. was theirs.

And yet, in 1974, the court, terming the Manobos squatters

on ranchland, decided in favor of the rancher Escano. The court

argued that the land, as forest land under special use, was

properly leased for pasture purposes, not agricultural. The rea

soning is intriguing-especially in light of the fact that Escano

turned around and sold the land to BUSCO for its sugar cane.

The 25 families stayed. They were not to be moved so

easily-at least not until they were given a place for resettle

ment. Even as BUSCO moved in, they stayed. They stayed

amidst constant harassment by BUSCO security guards as well

as by the local PCs (Philippine Constabulary). They stayed,

moving to their roofs when their doors and windows were nailed

shut. They stayed-until they were informed of an agreement

between Governor Lopez, the PC, and BUSCO that their

houses would not be destroyed until each family was resettled

on six hectares of land, with a house and a carabao. Only then

did they sign.

Words again. Mere words and promises. Easily broken.

On March 17 and 18, 1976, their homes were demolished

by the sheriff and 12 armed men. And the people, those 25

families? No six hectares. No home. No carabao. Only the

ground to sleep on during that cold, windy, rainy night, and, the

next day, the Quezon parish school.

Their neighbors, 40 more Manobo families, tell a similar

story. BUSCO had purchased their ancestral lands from Escano.

110 110. Panay hland: three U.s. ,oda companies compete atop old

Spani,h huilding. In ttlreground. a jeepney

* In 1976, SMC ranked fourth among Philippine corporations in net sales.

8

"The Guerilla Is Like a Poet"

by Jose Maria Sison*

The guerilla is like a poet

Keen to the rustle of leaves

The break of twigs

The ripples of the river

The smell of fire

And the ashes of departure.

The guerilla is like a poet.

He has merged with the trees

The bushes and the rocks

Ambiguous but precise

Well-versed on the law of motion

And the master of myriad of images.

The guerilla is like a poet

Enrhymed with nature

The subtle rhythm of the greenery

The outer silence, the outer innocence

The steel tensile in-grace

That ensnares the enemy.

The guerilla is like a poet.

He moves with the green brown multitude

In bush burning with red flowers

That crown and hearten all

Swarming the terrain as a flood

Marching at last against the stronghold.

An endless movement of strength

Behold the protracted theme:

The people's epic, the people's war.

* Sison is a Filipino poet and historian who has been detained. tortured and held

incommunicado since November 1977. This poem was supplied by the Philip

pine Research Center in Connecticut, U.S.A.

il

And once more, the company brought with it harassment and

destruction. This time, however, it was the PANAMIN main

office that sent,the orders to have the Manobos taken off their

land. PANAMIN, the supposed friend of the cultural minor

ities, ordered their evacuation. And so they were trucked in a

BUSCO vehicle like cattle, and dumped at the Quezon public

school and Catholic chapel. Dumped and left there. With little

food, little medicine, little shelter. It was there they lived for one

month. One long month.

Their promised resettlement did eventually come. They

were squeezed into the Dalurong PANAMIN reservation, a

1,300 hectare area which accommodated 200 families and was

to accommodate an increasing number of evicted Manobos.

Here again, BUSCO is the winner. PANAMIN plans for Dalu

rong include having the Manobos plant sugar cane on the sur

plus land (What surplus land? one wonders.)-and sell it to

BUSCO.

Justice?

Your lands, lands of years of life and death, grabbed by

BUSCO. And you, left to live and die in strange, new lands

while growing cane to feed the very mill that destroyed you.

1-alml), In San RllljUe I Broad I.

Rufo (" Dodong" ) Honongan, leader of the farmers at San

Roque, sits on the wooden bench there in the kitchen. His feet

are bare. His pants ragged. His face and arms deep brown from

the Bukidnon sun. A half-empty bottle of Tanduay stands in the

center of the table, stands in the middle of the five of us.

He looks at me. Our eyes meet and lock. "We will win, "

he says in slow, carefully enunciated English. His eyes flash.

His smile widens. It is a grim but sure smile. "We must win for

our children. "

There is silence.

He takes a gulp from his glass.

It is his voice that breaks the hush. "I will die for my

children's future. " He fingers the glass, but does not lift it to his

mouth.

The voices seem to explode.

No, we will not allow the sacrifice of our children-of our

land-and of our heritage-and of our very existence-to

continue.

Our children are being kidnapped.

We must fight for them.

9

j

Philippine "Normalization":

The Politics of Form

by Robert B. Stauffer

Third World nations, on the whole, have amply demon

strated that they cannot produce the ambiance for the democratic

institutions they inherited from their former imperial rulers. In

such poor nations, class cleavages are widening as a result of

structurally conservative development policies adopted by the

ruling elites in collusion with the First World. Elite attempts to

limit "politics" to the symbolic level, safely played out in

institutions largely insulated from any popular sharing in power,

have been frequently repudiated. Popular demands for struc

tural change in these countries have induced national elites to

dismantle representative institutions and to tum to more coer

cive methods of control.

There is mounting awareness of the unqualified horror of

Third World political repression, its massive, quantitative toll,

and the central role played by the United States in creating the

instrumentalities for destroying mass participation in politics

and for supporting such regimes. That awareness has led to

increasing public and private pressure, for a sharp break with

such practices.

As the linchpin in a global system that denies the right of

politics to those at the bottom and brutally represses attempts to

mobilize people for substantive change, the United States has

faced a formidable task. How could it fashion a global policy to

recapture something of its post-Vietnam "lost claim" to moral

leadership in the world and yet not weaken the repressive

regimes in the Third World that were the base of the capitalist

world economy? The answer provided by Carter has been sim

ply to reproduce on the world level a symbolic politics similar to

that utilized within the United States. Employ an untarnished

ideal-human rights in this case-as symbolic proof of

America's commitment to a new order in the Third World,

while making certain it would not be used to alter the structures

and uses of power internally and trans nationally .

The record of the American government's cynical attempt

to capture an emerging world public opinion of human rights for

its own use is still being written, even though many are becom

ing conscious of the blatant hypocrisy underlying its applica

tion.

2

Hopefully the American attempt will fail, since the revul

sion against political repression based on government-sanc

tioned terror is global, touching countless people. Victories in

narrow, specific areas-as in the winding down of murder by

"death squads" in Brazil's current "decompression" period,

or in the freeing of many political prisoners in Indonesia-may

blunt the edge of the human rights movement, especially since

so much of the movement is based on a narrow definition of

those rights. The prevailing definition carefully omits the

economic and social dimensions, and settles for an absence of

certain actions without demanding the presence of others.

The Phillippine campaign to "normalize" politics seems

to fit within the American attempt to regain the initiative at the

global level by seizing on a moral issue-human rights-and

using it in a highly selective and symbolic manner. In its

Philippine form, "normalization" seems to stress the purely

formal aspects of politics, to give less attention to human rights

issues associated with political prisoners (except to make much

of those released even as others are newly imprisoned). The

United States reinforces that form by not applying sanctions

despite the violations of the rights of political prisoners in the

Philippines.

This largely symbolic approach seems already to have

failed to convince the foreign media that anything significant

has been changed in the Philippines. Even less convinced are the

Filipinos who have had to live with the cascading economic

crises that have been their lot for the past several years, and with

the mounting evidence of a deepening corrosion in the New

Society brought on by the arrogance of power, the corruption of

the First Family, the militarization of society, etc. With open

talk about civil war commonplace, normalization can scarcely

be viewed a success.

Philippine Setting

For the past three years there has been talk in the Philippine

mass media about "normalizing" politics.

3

While there has

been almost no public discussion of what normalization would

look like when completed, each new modification in political

structure and practice is presented as a further step in the process

10

of achieving nonnalcy. A new referendum, an election, an

opening of a powerless assembly, a release of a group of

political prisoners, a shift to a greater use ofcivil courts for trials

of detainees-each is presented as a major step towards nonnal

ization. It is almost as if the process has become the goal, a sort

of Holy Grail component in the politics of the New Society; its

leader, meanwhile, makes the search for nonnalcy a major

theme in his articulation of public policy.

Any analysis of the Philippine attempt at nonnalization

must begin with a brief overview of the current political system

that is, putatively, being transcended. 4 It is a regime that fills the

mass media with messages of hope and accomplishment while

holding finn to the use of repression as an appropriate tool for

ruling;5 it is a regime that constantly proclaims its legality and

its adherence to constitutionalism and also simultaneously gov

erns on the basis of a myriad of presidential proclamations,

orders, decrees, etc., large numbers of which are not published

or are kept secret. 6 It is a regime committed to an ever increasing

rationalization of the associational life of the private sector

through corporatism, and, more importantly, to "develop

ment" above everything else. 7

This commitment to development is so overriding and so in

accord with the developmental models pushed by the regime's

transnational allies (the international aid dispensers, the foreign

banking community, and the multinational corporations) that

much of what has just been attributed to the regime has been

justified in its name. The demands of the foreign participants in

any Third World nation seeking rapid development are extreme

ly high and are well known. They demand political stability, a

favorable "investment climate," "liberalization" of the eco

nomy, etc. The internal consequences of the demands are also

becoming better known. To produce a "package" internally

that will "sell" externally, a Third World nation will, if it had

experienced a relatively open politics earlier, have to enforce

depoliticization on the public. This is necessary for at least two

central reasons. (I) Since all the externally-generated develop

ment models assume a conflict-free environment within which

experts decide on priorities for development, any previous

public involvement in affecting the outcomes of such decisions

must be ended. (2) Since the development model generated by

the transnational development community dispenses costs and

benefits in a grossly asymmetrical manner, depoliticization is

absolutely necessary to keep those who receive only "costs"

from demanding justice.

The regime-type that results from this confluence of de

velopmental interests has long been discussed, especially

among those concerned with Latin America. This discussion

has produced a number of definitions for the type, two of

which- "bureaucratic-authoritarianism"

8

and "associated

dependent development"9- capture the main meanings. More

recently the same phenomenon in Asia has bt<en subjected to

analysis, with considerable agreement among the various au

thors on the broad outlines of the type. 10 The discussion of the

Asian variant has, let it be noted, led to greater analytical clarity

and to an alternative description of the type: "repressive

developmentalist regimes." 1 1 All the authors agree that the

Philippines under martial law falls centrally within the ideal

type.

What then can nonnalization mean in a regime that can best

I be typed as "repressive-developmentalist?" All indications

point to a continuing absolute commitment to developmental-

ism despite the costs 12 and to mounting tensions generated by

both the successes and the failures of the attempt. In the face of

these fonnidable constraints, one can only marvel at Marcos'

brilliant political maneuvering.

13

In fact, one is reminded of

Churchill's version of an old saying: "Dictators ride to and fro

upon tigers which they dare not dismount. " The breathtakingly

swift overthrow of the Shah of Iran and of Somoza in Nicaragua

is vivid testimony to the existential reality behind this conven

tional wisdom, but even the transfonnations in recent years in

Greek, Spanish, and Portuguese regimes discount the notion

that an incumbent authoritarian leader is likely to survive the

process of system transfonnation to a more open politics. 14

As already implied, there are, of course, other short-tenn

solutions to the nonnalization dilemma. One can seek outside

confinnation that the regime is acceptable, nonnal, even demo

cratic. 15 This sort of confinnation is relatively easily obtained

by favored client states under conditions of crisis. At the very

height of the Carter human rights campaign, for example, his

chief spokesman, lody Powell, suggested the infinite flexibility

of that concept by tenning the murderous Mobutu regime of

Zaire" a moderate government. " 16 Moreover, since the OECD

nations have long had warm, close relations with selected Third

World nations, the overwhelming majority of which are at best

authoritarian polities, nonnalcy becomes an even more mooted

issue.

Whenever asked when he will lift martial law, Marcos

has just restated his intention to do so. Pressured by

the opposition late in 1979, he promised that "after 18

months, if the economic crisis has not worsened, I will

consider the matter of lifting martial law."

Another short-tenn solution is to carry out a campaign of

minor, cosmetic changes within the system and to label them as

marking major advances in nonnalization and democratization.

This seems to have been done in the Philippines. In examining

these changes in detail, let us begin by looking at the question of

nonnalization in the Philippines as articulated by Marcos and

others.

Philippine Normalization: The Marcos Position

In his many speeches as a senator, later as the president,

and still later in his books, Marcos has talked at length about

democracy. During much of the martial law era-imposed

September 21, 1972-he argued that his move to "crisis gov

~ r n m e n t " advanced democracy as did the new participatory

institutions he created to replace those overthrown. Critics at

home and abroad insistently refused to buy the argument, how

ever, that "voting" in national martial law referenda in which

there were no alternatives constituted the exercise of democratic

citizenship. Likewise voting for the membership in the new

barrio-level Barangay Assemblies hardly seemed like the exer

cise of democracy when the effective leadership at the local

government level remained in the hands of officials who owed

their positions to Marcos and were tightly controlled through

several central government administrative agencies.

II

1

I

Unable to convince his critics that his existing set of martial

law institutions represented a satisfactory "democratic" system,

Marcos began in late 1976 to admit the failure by talking about

nonnalization, always in a framework that implicitly admitted

the gap between his martial law rhetoric and reality.

Talk about nonnalization became commonplace in 1977.

continued through 1978 and 1979, and can be expected to

remain on the Marcos agenda in the immediate future. During

the early part of this period emphasis was placed on the creation

of a new national assembly; since the 1978 national elections

more attention has been given the question of local elections and

the lifting of martial law .

The latter two issues illustrate the rich manipulatory pos

sibilities inherent in nonnalization. Marcos repeatedly stated his

willingness to hold local elections, and often promised them for

relatively specific dates only to alter those dates later under one

or another escape clause he provided himself. 17

On one occasion in 1978 he gave a somewhat more candid

explanation for not holding these elections. After stating that he

had no intention of calling local elections immediately, he went

on to say:

We have not recovered from the divisiveness of the last one.

To speak of local elections now is to invite disaster. For it

would guarantee the rechanneling of the energies ofthe IBP

As many in the opposition have pointed out, the lifting

of martial law in itself will not bring profound changes.

It will also be necessary to dismantle the complex maze

of presidential rules that have restructured the Philip

pine polity.

(Interim Batasang Pambansa) members and of the citizenry

towards factionalism and petty party or group conflicts.

Members of the IBP and our citizenry would be more in

terested in the victory of their local political organizations

than in the task ofthe IBP. 18

This view of politics, if adherred to strictly, would, of

course, preclude there ever being local elections-or national

for that matter. To expect elections to take place without '"fac

tionalism" and party and group conflict is to hold to a view of

politics that may well accord with authoritarianism, but not with

democracy. 19 In another speech at about the same time Marcos

revealed more of his view of politics when he complained about

the 1978 election campaign in these words: '"It has compelled

the First Lady and me to move into the hustings to protect not

only the good name of our family-not only the President, the

First Lady, and our children- but also the entire government. "

After making clear his disapproval of having been forced to

defend his policies publicly, he went on to say: " ... [Hjow can

you now stand up before any other country and say that our

people are politically mature and that we are democratic and

that we conduct our politics with dignity if not elegance?"

(emphasis added). 20

Anxious that the form of Philippine elections should pre

sent a proper picture of dignity and elegance for foreign view

ers, Marcos indicated in 1978 that he would remove all local

officials whose constituencies had lost trust in them and who

had revealed themselves as inefficacious. Only after he had

replaced them would he consider holding local elections. More

over, he went on to state that" ... even more important to

political nonnalization than the mere calling of elections, is the

strengthening of the structure and administration of local gov

ernment. "21 Local elections were finally held (January 30.

1980), dramatically called the end of December, 1979 nearly a

full year before any previously mentioned date. Much of the

opposition boycotted the elections or were prevented by Marcos

from fielding slates of candidates. Consequently the local elec

tions produced a 98% victory for his Kilusang ng Bagong

Lipunan (New Society Movement-KBL), but not the digni

fied and elegant form of electoral democracy that he seems to

need. Rather, the elections produced widespread charges of

vote-buying, ballot box stuffing, intimidation, violence, and

corruption. 22

Whenever asked when he will lift marital law , Marcos has

just restated his intention to do so. Pressured by the opposition

late in 1979, he promised that "after 18 months, iftheeconomic

crisis has not worsened, I will consider the matter of lifting

martial law." 23 He added that he also needed martial law

powers' to complete the "cleanup" of the government and to

"find a peaceful solution to the Mindanao secessionist prob

lem," issues that should provide sufficient cover for an endless

delay in fulfilling his promise.

As many in the opposition have pointed out, the lifting of

martial law in itself will not bring profound changes. It will also

be necessary to dismantle the complex maze of presidential

rules that have restructured the Philippine polity. If Marcos

retains his presidential powers' 'for life," as he apparently will,

he will have complete authority to reimpose similar constraints

in the future. Moreover, the whole repressive machinery of the

"intelligence community" has been expanded under martial

law-there are now some seven civil and military intelligence

networks currently keeping tab on Filipinos

24

-and can be

expected to continue after the fonn of civil society has been

restored.

False Starts

Before examining in more detail what Marcos says he

thinks the nonnalization of politics in the future should entail,

let us review the various false starts. He sought a suitable

representative form through which an assembly could share

those legislative powers he saw fit to confer on them. His initial

plan, incorporated in the constitution of 1973 that was accepted

in open voting by hastily convened citizens' assemblies, was to

generate an interim legislature made up of two groups: a) those

members of the abrogated Philippine congress who would af

finn leyalty to the new constitution and agree to serve in an

interim National Assembly; and b) all those in the Constitutional

Convention who voted affirmatively for the final version of the

document. Marcos soon discarded these plans, perhaps remem

bering the heavy political costs he had had to pay to manipulate

the Constitutional Convention delegates prior to martial law . He

also may have pondered the fact that non-overlapping member

ships would have made for a very large legislative body. After

12

toying for a time (1973-1975) with the possibility of building a

national structure directly on his newly created Barangay as

semblies, he moved to create a complex structure of local

councils-Sangguniangs-culminating through successive

levels in a national federation and holding several huge national

meetings to discuss the question of national representative

bodies. At almost the same time Marcos created a Legislative

Advisory Council, made up of ex-officio officers and others

appointed by himself. Within a month of creating that council

(in September 1976), he held a national referendum largely to

amend the constitution to provide for a type of interim national

assembly other than the one provided for in the constitution. 25

Once that amendment had been passed and elections announced,

the main question of normalization was whether or not Marcos

would permit an opposition to contest the election. Subsequent

Iy, everyone wondered whether the Interim Batasang Pamban

sa (IBP) created by that election would tum out to be more than a

hollow shell ensconsced as it was by the summer of 1978 in an

elegant new parliament building, richly outfitted with all the

trappings of wealth and power.

The answer to the first question is now well known. Limit

ed campaigning by the opposition was permitted by Marcos in

Manila and in one or two other major cities. When the elections

-at least in Manila-clearly threatened to expose the total

rejection of urban Filipinos of the New Society, the martial law

regime resorted to massive fraud to assure the victory of its

(KBL) slate.

26

Immediately after the election the opposition

was crushed through mass arrests and other forms of repression,

although a handful of non-KBL assemblymen from southern

districts does sit in the IBP.

The answer to the second question cannot be as final

because the Interim Batasang Pambansa is only now finishing

its second year of life. Marcos views its existence as proof that

normalization has been almost completed. As he stated in his

address at its opening in June 1978: "Today, we manifest in

formal form a shift from authoritarianism to liberalism against

the trend of history which claims the irreversibility of the drive

towards authoritarianism and centralism."27 He went on to talk

about the continuing' 'normalization of our political life; , and

noted that "perhaps most important ... this Assembly is itself

a manifestation of it." 28 Later in the same speech he expressed

the view that" [W]e face in this Assembly the culmination of the

challenges and trials that had engaged our historic congresses of

the past, the fateful test of our national capacity for making

constitutional democracy our unfailing instrument to national

vitality and progress. "29

In the same address, however, Marcos made clear to the

IBP assemblymen that he alone had the ultimate power, that his

power did not flow from a political party with a majoritarian

mandate to rule. As he phrased it, " ... by their generosity, our

people have given me a direct constitutional mandate, "30 a

permanent life grant that, as a result of a plebiscitary referen

dum, "vests in the incumbent President and Prime Minister the

continuing power to legislate." Marcos saw fit to include the

point in his welcoming speech to the Assembly members. He

continued by saying he hoped that he would not have "to

deprive the Interim Batasang Pambansa the opportunity to

discharge its legislative authority," but that he would use his

"standby powers to effect necessary and urgent legislation"

should the legislature not act in an "alert and competent"

fashion. The "principle of standby powers for the presidency"

was immediately repeated and tied with the need to "secure

stability of government. " That requisite, in tum, was immedi

ately linked with a warning that" ... it is hardly the intent of

our people that the sharing of power diffuse the national will to

develop and modernize. "31 Armed with a continuing commit

ment to developmentalism-with all the power that ideology

gives to the executive branch, backed up by its technocrats, and

at the expense of the legislative-and clothed in constitutional

legal isms designed to give credence to his claim that he per

manently holds ultimate power in the Philippine political sys

tem, Marcos opened the New Society's first legislature.

To date the record of the Interim Batasanf Pambansa is not

impressive. Long periods of time have been spent in organiza

tional squabbles; more has been spent over matters of pay and

travel allowances. Since the planned IBP Record has not yet

been published, only newspaper accounts of the work of the

Assembly are available to evaluate its work. One summary of

laws passed at the end of the first regular session suggests

that not a single item of any significance survived: only bills

changing the name of a town or creating a new one, or making a

change in licensing regulations-tasks that might well have

been accomplished administratively without overstepping the

boundaries of regulatory competence- were signed into law. 32

Moreover, the flow of presidential decrees, orders, proclama

tions, etc., continues. 33

What the short-term experience suggests is that Marcos has

created a legislature more in keeping with those found in other

Third World nations committed to the same developmental

strategy. Like the congress of Brazil, the IBP can be expected to

playa "legitimating role for the regime, "34 and to be well-paid

and extravagantly housed and provisioned as part of the bargain.

Normalizing the regime includes the vitally important poli

tical act of defining what the new normalcy will be. Marcos has

made it clear that the new normalcy will include a legislature

that, while democratic inform, will, like the elections, be safely

under authoritarian controls. As one of the handful of opposition