Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Do Growing Brands Win Younger

Enviado por

quentin3Descrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Do Growing Brands Win Younger

Enviado por

quentin3Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

International Journal of Market Research Vol.

52 Issue 4

FORUM Do growing brands win younger consumers?

Katherine Anderson and Byron Sharp

Ehrenberg-Bass Institute for Marketing Science at the University of South Australia

Are young consumers easier to attract? We shed some light on the presumption that younger consumers are less loyal to brands and more willing than older consumers to try new brands. Analysis of 230 brands from 12 categories revealed a tendency for new and growing brands to skew towards younger consumers. This suggests that younger consumers are slightly easier for brands to attract. The most plausible explanation is that younger consumers are more likely to be new buyers of the category. We therefore caution that our results do not support a marketing strategy strongly targeting younger consumers. If a brand grows, then it is likely to attract a slightly disproportionate number of younger consumers. However, it does not follow that, if it seeks largely to attract younger consumers, it will grow.

Introduction and background

Are young consumers more willing to try different brands? Are they easier targets if you are trying to grow your brand? A colleague in industry had noticed that spirits brands that were growing strongly, like Patron and Grey Goose (UK 2006 data), tended to over-index among younger consumers, while those that were declining tended to over-index among older consumers. We were curious whether this pattern was evident in purchase data from other categories and what plausible explanations there might be. We were particularly intrigued by this pattern because research by Ehrenberg and colleagues has demonstrated that such deviations are uncommon, with rival brands tending to sell to similar types of consumer

Received (in revised form): 21 October 2009

2010 The Market Research Society DOI: 10.2501/S1470785309201387

433

Forum: Do growing brands win younger consumers?

(Hammond et al. 1996; Kennedy & Ehrenberg 2000a, 2000b, 2001a, 2001b; Ehrenberg & Kennedy 2000; Kennedy et al. 2000). However, it seemed plausible that, within the small deviations that do exist between rival brands,1 a systematic pattern might be evident.

Research approach

We analysed purchase data for 230 brands across 12 product categories, looking for a systematic pattern in the data. Categories included coffee, bar confectionery, dog food, beer, spirits, cars, internet service provider, mobile phone provider, health insurance, car insurance, credit cards and financial services. Some of these categories grew, and some declined over the period studied, providing a robust sample. The data were generously provided by the Nielsen Company and TNS. The Nielsen Panorama Survey data described claimed purchase behaviour (penetration) in the Australian market for 2001 and 2006. The TNS Superpanel data described actual purchasing behaviour (volume) in the UK market for 2005 and 2007. By comparing two periods of data, we were able to determine which brands grew (relative to the category), which declined (relative to the category) and which were new to the category, and investigate whether the user profiles of these brands were systematically different. From the raw purchase data (2006/7), the proportion of each brands sales/customers from each age group was calculated the brands age profile. The profile of each brand was compared to the age profile for that product category. The proportion of users younger than 30 for each brand was plotted against brand performance (new brands were assigned a growth rate of 100% for the period). The axis intercepts were calibrated against the categorys performance and user profile (see Figure 1), dividing the scatter plot into quadrants of older and growing, youthful and growing, youthful and declining, and older and declining. The proportion of brand users older than 55 was plotted in the same way for each category. These category charts provided a broad snapshot of the patterns in the data. To quantify how well a brand performed in each age group, index numbers were calculated using the product category profile as the base. The index numbers for each brand were independently assessed by both authors. Brands that skewed towards younger or older consumers were identified and counted. Age was considered in relative rather than absolute

Ehrenberg and Kennedy had previously noted a few systematic differences, e.g. childrens brands skew towards children, Scottish newspapers have more Scottish readers (Kennedy & Ehrenberg 2000a).

1

434

International Journal of Market Research Vol. 52 Issue 4

terms (i.e. younger not young) as the absolute age of new category buyers is dependent on the category, e.g. consumers enter the beer category decades before they enter the market for high-cholesterol margarine. Also, brands that skewed towards a particular age group because of obvious functional differences, like Kinder Surprise or Australian Pensioners Insurance Agency, were removed. The remaining 230 brands were divided into three groups new, growing and declining and patterns within and across each group were identified by the authors.

Results

Figure 1 and Table 1 show the results from one category, coffee. Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between customer base growth and a brands user profile. In the coffee category, new and growing brands tended to have more youthful user profiles, as demonstrated by the clustering of data points in the top-right quadrant. Four of the six brands that grew more than the category between 2001 and 2006 also had more users under the age of 30 than the category. Declining brands tended to have fewer younger users, as demonstrated by the clustering of data points in the bottom-right quadrant. Eight of the ten brands that declined over this

100 Growth % 20016 80 60 40 20 0 20 Older 0 5 Proportion of brand users 1429 years old 10 15 40 20 60 80 R2 = 0.55099 100 Declining 25 30 Youthful 35 Growing

Figure 1 User pro le of co ee brands vs performance (2006)

435

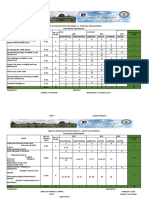

Table 1 User profile of coffee brands

Age groups (years old) Change 20016 (%) 37 3 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 10 7 10 9 11 9 10 9 6 100 515 1599 1179 1674 1591 1865 1584 1657 1513 1005 14 17 18 24 25 29 30 34 35 39 40 44 45 49 50 54 55 59 60 64 65+ 2603 16 100

Category

New

Growing

Declining

436 Users 2006 (000s) 16,475 100 100 26,216 Users 2006 (000s) Change 20016 (%) Brand profiles index numbers 106 99 130 92 93 126 113 114 96 122 81 75 65 87 150 73 156 52 40 80 95 102 68 109 134 94 110 67 67 93 81 96 117 78 84 91 81 102 111 121 102 85 98 81 101 86 96 105 99 90 54 101 86 99 145 109 111 102 131 81 101 104 94 64 75 100 101 166 101 97 109 118 104 87 112 115 94 97 89 71 91 86 111 104 78 73 88 270 126 75 56 78 87 34 67 79 137 116 109 70 91 128 94 85 53 103 74 80 86 115 166 177 82 76 95 107 108 112 112 117 110 93 89 56 57 102 121 146 74 60 94 97 110 104 101 151 101 101 97 107 89 101 138 129 108 69 96 90 91 100 99 121 130 88 115 113 100 116 152 127 112 35 100 59 73 94 96 102 138 136 69 158 120 145 130 91 8 8 11 32 42 52 57 62 70 70 72 72 77 78 432 241 6714 1130 1215 2295 559 579 681 1192 262 310 300 417 209 249 0 0 6240 1225 1368 3364 959 1210 1598 3098 867 1035 1058 1490 892 1120

Category

Users 2001 (000s)

Buyers

Profile (%)

Index base

Brands

Users 2001 (000s)

Riva

Piazza DOro

Nescaf

Lavazza

Forum: Do growing brands win younger consumers?

Vittoria

Moccona

Robert Timms

Harris

Maxwell House

International restaurant

Caf Aurora

Supermarket

Jarrah

Bushells

Melitta

Andronicus

* Users denotes the projected number of category/brand users in Australia based on a sample of n ~ 20,000

International Journal of Market Research Vol. 52 Issue 4

period had fewer users under the age of 30 than the category. The inverse pattern was evident when the proportion of brand users older than 55 was plotted; declining brands tended to have more older users and growing brands tended to have fewer (results not shown). Similarly, as Table 1 details, both the new-to-market brands, Riva and Piazza DOro, skew towards young consumers index numbers across the younger age groups are greater than 100. Similarly, growing brands tend to over-index among consumers younger than 45, the median age of buyers of this category. This skew is more pronounced for brands that grew particularly strongly, like Nescaf and Lavazza. Furthermore, as expected, many of the declining brands over-index among older consumers. While there are some exceptions, such as Caf Aurora, the overall pattern was for new and growing brands to over-index among younger consumers and declining brands to over-index among older consumers, as highlighted by the bold numbers in Table 1. The same procedure was repeated across the other 11 product categories, the results of which are summarised in Table 2. Across the 12 product categories, the new-to-market brands were most likely to skew towards younger consumers (3 to 1 more likely to skew younger than older). Growing brands were also more likely to skew towards younger consumers. In complete contrast, declining brands were more likely to skew towards older consumers. The presence of younger customers appears to be an indicator of brand health, with declining brands tending to have a disproportionate number of older customers and lack of younger customers.

Table 2 Pattern of age skews across 12 categories

Skewed towards Younger consumers Middle-aged consumers Older consumers No skew Total New brands n = 69 (%) 48 7 15 33 100 Growing brands n = 96 (%) 34 15 24 23 100 Declining brands n = 94 (%) 19 14 30 31 100

Discussion

Pervious research has established that brand growth (and decline) is largely driven by customer acquisition (Riebe 2003). Our finding, that growing

437

Forum: Do growing brands win younger consumers?

brands tend to skew towards younger consumers, indicates that younger consumers are slightly more easily acquired. A plausible explanation for our results is that younger buyers account for a disproportionate percentage of those consumers that are available for brands to acquire. Younger consumers are more likely to be new category buyers adopting brands as they establish a repertoire, and therefore represent a disproportionate amount of the consumers available for a brand to acquire. Consequently, younger consumers are more easily attracted, in comparison to older consumers who buy new brands less often because they already have an established repertoire of brands from which they tend to buy. Following Riebes findings, declining brands, which are failing to win many new customers, are not replenishing their customer base with the younger customers needed to offset the ageing of their existing customers, and consequently their brand profile gradually begins to skew older. An alternative, perhaps more salient, interpretation is that young people, by virtue of their youth are less loyal. There is a widespread belief among marketing practitioners that young people are fickle and hence less loyal to brands. For example, Young & Rubicams Simon Silvester contends that, when consumers are young they relish new experiences, are promiscuous in their brand buying and responsive to new ideas, but that as consumers grow older their buying habits ossify and their brand repertoires become fixed (Silvester 2002, 2003). However, our results do not lend credence to this, widely spread, speculation. Across the 12 categories, only 48% of new-to-market brands skewed towards young people, a far lower proportion than would be expected if young people really were more fickle and willing to experiment. Furthermore, new and growing brands tended to skew towards younger buyers, but not necessarily young it depended on when consumers were likely to be entering the category or considering new product varieties. So, for low-cholesterol spreads, growing brands over-index among younger consumers, meaning those aged 4564 years old. It might be easier to attract consumers who are younger than the average buyer of your category, but they may not necessarily be young per se. As for the notion of older consumers being unwilling to try new brands, our results show that this is an exaggeration. None of the skews was extreme and, besides, of the 69 new brands we analysed, 1 in 7 of them skewed towards older demographics, highlighting that older consumers do purchase new brands and that the brand loyalties of older consumers are not completely entrenched. Furthermore, as Table 2 illustrates, 33% of new brands did not skew to any particular age group, instead acquiring

438

International Journal of Market Research Vol. 52 Issue 4

a normal amount of young, middle-aged and old consumers. This is particularly notable as, in most categories, consumers 55-plus account for about 30% of buyers, so a new brand had to acquire quite a few older consumers for it to have even a normal age profile. These results cast doubt on the conventional wisdom that, soon after reaching middle age, consumers fix their brand repertoires and rarely consider new brands. While about two-thirds of brands we studied showed an age skew, it is important to note that these skews were generally small, especially once put into the context of the brands age profile. Take, for example, Nescaf in Table 1, which skewed towards younger consumers. Nescaf has more customers aged 1417 than expected, as signified by the index number of 126. But a mere 3.9% of its customers fall into this demographic, which is only slightly more than would be expected given that 3.1% of category buyers are 1618 years old. As for the other 96.1% of Nescafs customers, they come from all age groups. Consistent with past findings, the dominant pattern in user-profile results is that customer profiles of competing brands are very similar (Hammond et al. 1996; Ehrenberg & Kennedy 2000; Kennedy et al. 2000; Kennedy & Ehrenberg 2000a, 2000b, 2001b). The patterns in the data suggest that young consumers are slightly easier to attract. Not because they are innately less loyal, but because they account for a disproportionate percentage of the consumers available for a brand to acquire in any given year. However, one limitation of our aggregate-level research is that we cant prove this directly. We cant track the behaviour of individuals and see what proportion of category buyers are new to the category, or what proportion of these new category buyers are younger. Further research to confirm our assumptions would be valuable, although we recognise the great difficulties in conducting such research empirically.

Conclusions

Our research indicates that younger consumers are slightly easier for brands to attract. We believe this is because they are more likely to be new to the product category and not yet the established customers of other brands. Younger consumers are more likely to be new to the category and adopting brands to develop a repertoire, so they probably account for a disproportionate percentage of the consumers available for a brand to acquire. This matters because brand growth depends so heavily on acquisition.

439

Forum: Do growing brands win younger consumers?

The results underscore that brand loyalty is alive and well its not easy to change the habitual loyalties of buyers and win them over from other brands, but it is possible. The brand loyalties of older consumers are not completely entrenched or unchangeable. While young consumers may be slightly easier to win as customers, it is difficult for a brand to grow, and near impossible for it to be a big brand without selling to consumers from all age groups.

Implications for strategy

Growing brands should expect that a disproportionate percentage of their new customers will be young, or rather younger than their existing customers. But whether marketers ought to skew their advertising, distribution and sales efforts to younger consumers is an entirely different matter. For new brands that are under time and budgetary pressure to prove their commercial viability, it makes sense to go for the easier targets at least at first. And, for established brands, its important to reach younger consumers who are learning about brands. But we would caution marketers against targeting younger consumers exclusively. Brands that successfully grow are likely to have a base of somewhat younger customers, but this does not mean that targeting younger consumers is the path to growth. No marketing or media strategy should deviate much from the demographic groups that deliver most of the category sales volume.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Andrew Barnett of Highland Distillers (UK), whose work inspired this study.

References

Ehrenberg, A.S.C. & Kennedy, R. (2000) Users of competitive brands seldom differ. Paper presented at the Market Research Society Conference, Brighton, UK, 1517 March. Hammond, K., Ehrenberg, A.S.C. & Goodhardt, G.J. (1996) Market segmentation for competitive brands. European Journal of Marketing, 30, 12, pp. 3949. Kennedy, R. & Ehrenberg, A. (2000a) Brand user profiles seldom differ (Research Report No.7). Adelaide: Ehrenberg-Bass Institute for Marketing Science. Kennedy, R. & Ehrenberg, A. (2000b) The customer profiles of competing brands. Paper presented at the 29th European Marketing Academy Conference, Rotterdam. Erasmus University, 2326 May. Kennedy, R. & Ehrenberg, A. (2001a) Competing retailers generally have the same sorts of shoppers. Journal of Marketing Communications, 7, Special Retail Edition, pp. 18.

440

International Journal of Market Research Vol. 52 Issue 4

Kennedy, R. & Ehrenberg, A. (2001b) There is no brand segmentation. Marketing Insights, Marketing Research, 13, 1, Spring, pp. 47. Kennedy, R., Ehrenberg, A. & Long, S. (2000) Competitive brands user-profiles hardly differ. Paper presented at the Market Research Society Conference, Brighton, UK, 1517 March. Riebe, E. (2003) Normal rates of defection and acquisition and their relationship to market share change. Unpublished PhD, University of South Australia, Adelaide. Silvester, S. (2002) Youre getting old. Admap, 433, pp. 2931. Silvester, S. (2003) The ageing populations threat to innovation. Market Leader, Autumn, 22, pp. 4149.

About the authors

Katherine Anderson is a research associate at the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute for Marketing Science at the University of South Australia, Australia. Byron Sharp is Professor of Marketing Science and director of the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute for Marketing Science at the University of South Australia, Australia. Address correspondence to: Katherine Anderson, Ehrenberg-Bass Institute, University of South Australia, North Terrace, Adelaide SA 5000, GPO Box 2471, Adelaide SA 5001. Email: Katherine.Anderson@UniSA.edu.au

441

Copyright of International Journal of Market Research is the property of World Advertising Research Center Limited and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Você também pode gostar

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- History of Retail in 100 ObjectsDocumento75 páginasHistory of Retail in 100 Objectsquentin3Ainda não há avaliações

- Grit W13Documento60 páginasGrit W13quentin3Ainda não há avaliações

- Web Surveys Versus Other Survey ModesDocumento27 páginasWeb Surveys Versus Other Survey Modesquentin3Ainda não há avaliações

- F JWT Retail-Rebooted Trend-Report 08.16.13Documento44 páginasF JWT Retail-Rebooted Trend-Report 08.16.13quentin3Ainda não há avaliações

- Consumer Choice Behavior Online vs Traditional SupermarketsDocumento24 páginasConsumer Choice Behavior Online vs Traditional Supermarketsquentin3Ainda não há avaliações

- Do Data Characteristics Change AccordingDocumento18 páginasDo Data Characteristics Change Accordingquentin3Ainda não há avaliações

- Measuring Brand PerceptionsDocumento14 páginasMeasuring Brand Perceptionsquentin3Ainda não há avaliações

- Using Known Patterns in Image DataDocumento13 páginasUsing Known Patterns in Image Dataquentin3Ainda não há avaliações

- Why Modeling Averages Is Not Good EnoughDocumento12 páginasWhy Modeling Averages Is Not Good Enoughquentin3Ainda não há avaliações

- It's A Dirichlet WorldDocumento12 páginasIt's A Dirichlet Worldquentin3Ainda não há avaliações

- Predictions in Market Research White Paper 2Documento11 páginasPredictions in Market Research White Paper 2quentin3Ainda não há avaliações

- A New Measure of Brand AttitudinalDocumento23 páginasA New Measure of Brand Attitudinalquentin3Ainda não há avaliações

- What's Not To LikeDocumento9 páginasWhat's Not To Likequentin3Ainda não há avaliações

- Triple JeopardyDocumento9 páginasTriple Jeopardyquentin3Ainda não há avaliações

- Is Once Really EnoughDocumento4 páginasIs Once Really Enoughquentin3Ainda não há avaliações

- Loyalty Limits For Repertoire MarketsDocumento9 páginasLoyalty Limits For Repertoire Marketsquentin3Ainda não há avaliações

- What's Not To LikeDocumento9 páginasWhat's Not To Likequentin3Ainda não há avaliações

- Google ZmotDocumento75 páginasGoogle ZmotJavier Alejandro Lozano HarchaAinda não há avaliações

- WPP MBA Fellowship Program Aug11Documento6 páginasWPP MBA Fellowship Program Aug11quentin3Ainda não há avaliações

- Nielsen Global New Products Report Jan 2013Documento22 páginasNielsen Global New Products Report Jan 2013Ali ShamsheerAinda não há avaliações

- Kaczmirek Survey DesignDocumento7 páginasKaczmirek Survey Designquentin3Ainda não há avaliações

- 1Documento19 páginas1Pei Shi LimAinda não há avaliações

- Infuencing The Online Consumers Behavior - The Web Experience - CONSTANTINIDESDocumento16 páginasInfuencing The Online Consumers Behavior - The Web Experience - CONSTANTINIDESquentin3Ainda não há avaliações

- Infuencing The Online Consumers Behavior - The Web Experience - CONSTANTINIDESDocumento16 páginasInfuencing The Online Consumers Behavior - The Web Experience - CONSTANTINIDESquentin3Ainda não há avaliações

- Online Customer Behaviour - A Review and Agenda For Future Research - CHEUNGDocumento25 páginasOnline Customer Behaviour - A Review and Agenda For Future Research - CHEUNGquentin3Ainda não há avaliações

- 1Documento19 páginas1Pei Shi LimAinda não há avaliações

- QSR 5 3 Konecki-1Documento29 páginasQSR 5 3 Konecki-1quentin3Ainda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- Enhancing Community SafetyDocumento10 páginasEnhancing Community SafetyDianne Mea PelayoAinda não há avaliações

- TNT FinalDocumento34 páginasTNT FinalNatasha PereiraAinda não há avaliações

- Unit - Iv Testing and Maintenance Software Testing FundamentalsDocumento61 páginasUnit - Iv Testing and Maintenance Software Testing Fundamentalslakshmi sAinda não há avaliações

- W8 Pembolehubah Dan Skala PengukuranDocumento38 páginasW8 Pembolehubah Dan Skala PengukuranIlley IbrahimAinda não há avaliações

- Science, Technology, and The Future New Mentalities, NewDocumento1 páginaScience, Technology, and The Future New Mentalities, NewSheena Racuya100% (1)

- Project Report at BajajDocumento59 páginasProject Report at Bajajammu ps100% (2)

- Certificate of Calibration: Customer InformationDocumento2 páginasCertificate of Calibration: Customer InformationSazzath HossainAinda não há avaliações

- Nursing Process in CommunityDocumento8 páginasNursing Process in CommunityFahim Ahmed100% (1)

- General Knowledge & Current Affairs E-BookDocumento1.263 páginasGeneral Knowledge & Current Affairs E-BookQuestionbangAinda não há avaliações

- How To Make Research Paper Chapter 4Documento7 páginasHow To Make Research Paper Chapter 4fvf8zrn0100% (1)

- Readings in The Philippine HistoryDocumento4 páginasReadings in The Philippine HistoryRecil Marie BoragayAinda não há avaliações

- Between Helping Hand and Reality (MOM's TJS) by Yi enDocumento23 páginasBetween Helping Hand and Reality (MOM's TJS) by Yi encyeianAinda não há avaliações

- Cultural Heritage and Indigenous TourismDocumento14 páginasCultural Heritage and Indigenous TourismLuzMary Mendoza RedondoAinda não há avaliações

- Template FMEA5Documento5 páginasTemplate FMEA5Puneet SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Kamrul Hasan PDFDocumento153 páginasKamrul Hasan PDFayshabegumAinda não há avaliações

- Fitness CrazedDocumento5 páginasFitness CrazedLes CanoAinda não há avaliações

- US NRC - Applying Statistics (NUREG-1475)Documento635 páginasUS NRC - Applying Statistics (NUREG-1475)M_RochaAinda não há avaliações

- Andhy Noor Aprila - Instructional Project 4 LPDocumento7 páginasAndhy Noor Aprila - Instructional Project 4 LPapi-549098294Ainda não há avaliações

- Imperative Effectiveness of Locally-Made Acids and Bases On Senior Secondary Chemistry Students' Academic Performance in Rivers StateDocumento14 páginasImperative Effectiveness of Locally-Made Acids and Bases On Senior Secondary Chemistry Students' Academic Performance in Rivers StateCentral Asian StudiesAinda não há avaliações

- Comparative Study of Infrastructure, Teaching and Results in Girls and Boys Secondary SchoolsDocumento48 páginasComparative Study of Infrastructure, Teaching and Results in Girls and Boys Secondary SchoolsimranAinda não há avaliações

- Motivation in Physical Activity Contexts: The Relationship of Perceived Motivational Climate To Intrinsic Motivation and Self-EfficacyDocumento17 páginasMotivation in Physical Activity Contexts: The Relationship of Perceived Motivational Climate To Intrinsic Motivation and Self-EfficacyAndreea GligorAinda não há avaliações

- How To Write An Introduction For A Research Paper PowerpointDocumento6 páginasHow To Write An Introduction For A Research Paper Powerpointefhs1rd0Ainda não há avaliações

- Table of Specification For Grade 12 - Personal Development First Quarter ExaminationDocumento17 páginasTable of Specification For Grade 12 - Personal Development First Quarter ExaminationArgie Joy Marie AmpolAinda não há avaliações

- Nepal Health Research Council Sets National Health Research PrioritiesDocumento15 páginasNepal Health Research Council Sets National Health Research Prioritiesnabin hamalAinda não há avaliações

- Critical ReadingDocumento4 páginasCritical ReadingIccy LaoAinda não há avaliações

- Statistical analysis of public sanitation survey dataDocumento1 páginaStatistical analysis of public sanitation survey dataLara GatbontonAinda não há avaliações

- Patterns of Data Driven Decision Making - Apoorva R Oulkar & Atul MandalDocumento8 páginasPatterns of Data Driven Decision Making - Apoorva R Oulkar & Atul MandalAR OulkarAinda não há avaliações

- ANALYSIS OF LEARNING STRATEGIES AND SPEAKING ABILITYDocumento10 páginasANALYSIS OF LEARNING STRATEGIES AND SPEAKING ABILITYZein AbdurrahmanAinda não há avaliações

- What I Have Learned: Activity 3 My Own Guide in Choosing A CareerDocumento3 páginasWhat I Have Learned: Activity 3 My Own Guide in Choosing A CareerJonrheym RemegiaAinda não há avaliações

- Journal of English For Academic Purposes: Christopher Hill, Susan Khoo, Yi-Chin HsiehDocumento13 páginasJournal of English For Academic Purposes: Christopher Hill, Susan Khoo, Yi-Chin Hsiehshuyu LoAinda não há avaliações