Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

London Residents

Enviado por

donatelojDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

London Residents

Enviado por

donatelojDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Journal of Sport & Tourism Vol. 15, No. 4, November 2010, pp.

337 357

Residents Perceptions of Environmental and Security Issues at the 2012 London Olympic Games

Maria Konstantaki & Eugenia Wickens

Staging a mega sport event such as the Olympic Games has been traditionally viewed as a golden opportunity for urban regeneration and economic development. Research into residents perceptions of environmental impacts and security risks at Olympic Games is limited. This paper discusses residents perceptions of environmental and security issues associated with the London 2012 Olympic Games. The study used a purposive sample of local residents (n 100) of which 50% were in the age range of 18 34 years (Group A) and 50% were 35 55 years or over (Group B). Forty-two per cent of Group A and 28% of Group B lived in London. Data were collected through self-administered questionnaires. Findings showed that the majority of respondents in both groups overwhelmingly supported the 2012 Games and were lled with a sense of national pride and excitement for London being the host city. However, ndings also demonstrated differences between the age groups in their perceptions of the environmental impacts of the 2012 Games. Group B expressed consistently more negative attitudes compared with Group A with regards to pollution, trafc congestion and parking availability. Both groups were equally concerned about the inadequacies of the transport system. Group B respondents also perceived increased security risks during the Games that could negatively affect attendance at the Games. Both groups showed a lack of condence that security would be ensured at the Games. These ndings contradict planned environmental and security initiatives that are currently underway and indicate that 2012 stakeholders need to improve communication and public consultation to raise public awareness and instil condence. Keywords: 2012 London Olympics; Environmental and Security Issues; Age-related Perspectives

Maria Konstantaki and Eugenia Wickens are at the School of Management, Buckinghamshire New University, Queen Alexandra Road, High Wycombe HP11 2JZ, UK. Correspondence to: Maria Konstantaki, School of Management, Buckinghamshire New University, Queen Alexandra Road, High Wycombe HP11 2JZ, UK. Email: Maria.konstantaki@bucks.ac.uk ISSN 1477-5085 (print)/ISSN 1029-5399 (online) # 2010 Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/14775085.2010.533921

338

M. Konstantaki & E. Wickens

Introduction The Olympic Games are regarded as the worlds most prestigious sporting occasion and they have evolved into a major international event with great economic, cultural, political and social importance (Girginov & Parry, 2005). The Olympic Games are also seen as panacea for economic growth and as a signicant catalyst for urban regeneration (Jones & Stokes, 2003). It is not surprising that host cities invest considerably on improving sporting facilities and supporting infrastructure to enhance the potential for purported economic prots although Olympic-related investments are often based on predictions that economic growth will result from the inux of thousands of visitors to the host city and the creation of thousands of new jobs (Ritchie & Smith, 1991). Nevertheless, economic growth following the Games is not guaranteed (Mules & Faulkner, 1996) and there have been examples of the Olympic Games bringing about economic havoc rather than prosperity and afuence to the host city. Conversely, little attention is paid to careful consumption of the natural environment in preparation of Olympic Games. Historically, studies on sport tourism events tend to focus on economic impacts and generally neglect environmental dimensions (Kim & Petrick, 2005). A wellmanaged environmental programme linked to a mega events sporting and multicultural investment can bring a handsome dividend to a host city and its greater region (Dodouras & James, 2002) even though until now impacts of sport tourism on the environment have been shown to be negative (Standeven & deKnop, 1999). Environmental destruction arising from construction of Olympic facilities and refurbishment of transport systems can lead to degradation of the physical and biological environment by causing air, water, soil and visual pollution (Cashman, 2002). Security is another dimension of sport events that has gained attention in recent years. The globalization of the Olympic Games as a major sporting event has meant that they can often act as target for terrorism (Essex & Chalkley, 1998). The terrorist attack of 11 September 2001 in the United States resulted in a steep increase in security spending in preparation to host the 2002 Salt Lake City Winter Games and the 2004 Athens Summer Olympic Games, while the Munich Olympics massacre of 1972 and the Atlanta Olympics bombing of 1996 have been recorded as grim markers in Olympic history (Matheson & Baade, 2004). Other terrorist attacks such as the Bali (2002), Madrid (2004) and London (2005) bombings have heightened public concern about terrorism threats and perception of risk for sport events (Taylor & Toohey, 2007). Residents perceptions are overlooked although they are often directly impacted by sport events, especially when they reside in close proximity to the event location (Bob & Swart, 2009). Key studies that have investigated residents perceptions of sport events (Deccio & Baloglu, 2002; Fredline & Faulkner, 2000; Ritchie & Adair, 2004; Ritchie et al., 2009) focused predominantly on the socio-economic impact of the event. The purpose of this paper is to discuss residents perceptions of key environmental and security issues associated with hosting the 2012 Olympic Games in London. Even though the literature is fairly rich in studies of economic impacts of mega sport events,

Journal of Sport & Tourism

339

such as the Olympic Games, few studies have focused on investigating the environmental and security aspects. In particular, fewer studies have focused on exploring residents perceptions of these topical issues of the Olympic Games, which is contrary to calls for environmental sustainability and event security often reported in the literature. In addition, there have been no published investigations that have combined these two very important aspects of the Olympic Games in one study. The rationale for exploring these two aspects in one study is to provide insight into residents perceptions of environmental and security issues in the run up to the London 2012 Olympic Games that might be useful to event organizers in targeting the areas of public concern within planned initiatives for environmentally friendly and secure Games. A review of the literature on resident perceptions of sport events is provided. The perceptions of residents of key environmental and security issues associated with the London 2012 Olympic Games are discussed alongside implications for planning initiatives.

Literature Review Residents Perceptions of Sport Tourism Previous research has highlighted that resident perceptions of sport tourism are generally negative and that this negativity is proportional to residents proximity to concentrations of sport tourism activity where event-related construction takes place (Standeven & deKnop, 1999). Sporting events have, albeit differentially, impacts upon the community within which they are held (Ohmann et al., 2006). Community support is essential for the success of a sporting event. However, it has been shown to be dependent on the perceived benets and costs associated with the event (Deccio & Baloglu, 2002). The benets or positive impacts of sport tourism include provision of a community facility, job creation (Hall, 2004), and the promotion of the area for tourism, whereas central to the negative impacts are more drunken driving, trafc problems, and increased noise (Mason & Cheyne, 2000). Residents are seriously concerned about environmental pollution and congestion associated with sport event-related developments (Tatoglu & Erdal, 2002) and they often feel disenfranchised by the planning process which may result in forming negative perceptions toward the event (Fredline & Faulkner, 2002). In order for residents to tolerate the inconveniences associated with hosting a sport event (such as queuing for services, sharing local facilities, overcrowding, trafc congestion, and route disruption), the perceived rewards should equal their willingness to carry the infrastructure costs, extending friendliness, courtesy and hospitality to tourists (Waitt, 2003). Residents opinions are inuenced by exposure to a variety of information sources (Baloglu & McClearly, 1999). Even though event-related publicity helps increase the residents familiarity with the sport tourism event, it can also act as platform for shaping a positive or negative attitude (Chon, 1992). Other factors that have been implicated with shaping residents attitudes towards sport tourism development include gender, age (Johnson et al., 1994; Mason & Cheyne, 2000; Tomljenovic &

340

M. Konstantaki & E. Wickens

Faulkner, 2000; Kim & Petrick, 2005), social status (Ritchie et al., 2009), and education, occupation and income (Waitt, 2003). Even though some of these studies suggested that the differences in attitudes can be best attributed to the heterogeneity of urban communities rather than demographic variables. Residents support of a sport tourism event in the years running up to the event has been investigated in a few studies. Mihalik & Simonetta (1999) monitored the perceptions of residents of Georgia regarding the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games for four years prior to the event. It was reported that, over time, Georgia resident support remained strong, projected attendance decreased greatly, the intangible benets were ranked greater than the economic issues, and the top perceived negative consequences dealt with law-enforcement issues. Deccio & Baloglu (2002) examined non-host community residents perceptions of the spillover effects of the 2002 Winter Olympic Games. Findings indicated that environmentally conscious residents do not support the Olympics, whereas those who are economically dependent on tourism or participate in outdoor activities generally support them. The study concluded that, overall, most residents indicated that they do not support or oppose the event but do encourage promotion of the area during the Olympics and would be willing to support their rural community activities during the mega event. Gursoy & Kendall (2006) developed and tested a structural model to assess key factors on residents perceptions of the impacts of the 2002 Winter Olympics as a mega tourism event and how these perceptions affect their support. It was concluded that community support for mega events is affected directly and/or indirectly by ve interrelated determinants of support: the level of community concern, eco-centric values, community attachment, perceived benets, and perceived costs, and that support relies heavily on perceived benets rather than costs. Ritchie et al. (2009) investigated non-host city resident perspectives of the 2012 London Olympic Games. Findings showed that generally residents were supportive of hosting the event in the local area but were concerned over perceived trafc congestion, parking issues and potential increases in the cost of living. Residents perceptions are crucial in assisting tourism planners with selection of developments that aim to minimize negative impacts (Gursoy et al., 2002). In preparation for the 2012 Olympic Games, developmental projects aim directly to affect the well-being of the local community. Therefore, residents opinions should form an integral part of the strategic planning development of the London 2012 Olympic Games. In what follows, the paper discusses the environmental and security impacts of the Olympic Games. Environmental Impacts of the Olympic Games Olympic projects are bound to intervene with nature and to produce changes in the environment (Girginov & Parry, 2005). In some cases, these changes (or environmental impacts) have been shown to be positive. Deccio & Baloglu (2002) noted that mega sport events can help preserve the physical environment and local heritage, which otherwise might not have happened if the mega event was not held. The hosting of a mega event may also be part of a larger urban regeneration programme, such as

Journal of Sport & Tourism

341

that experienced in Manchester for the 2002 Commonwealth Games or Barcelona for the 1992 Olympic Games. In both instances the hosting of the mega sport event was tied to major regeneration, canal or waterfront development, development of tourist attractions, shopping and dining facilities as well as improvements in transport infrastructure (Ritchie et al., 2009). The Sydney 2000 Olympic Games were another example of environmentally viable Games. The positive environmental impact of the Sydney Olympics was mainly attributed to careful planning by the Sydney Organising Committee for the Olympic Games (SOCOG) that was based on the principles adopted at the United Nations Earth Summit in Rio, Brazil, in 1992. Sydney Olympic projects incorporated energy and water conservation, waste avoidance and minimization, protection of human health (through appropriate standards of air, water, soil quality) and protection of signicant natural environments (Standeven & deKnop, 1999). Conversely, other researchers have reported negative environmental impacts of Olympic Games. The 1992 Winter Olympic Games in Albertville will remain in history as the Games with the most destructive impact on the natural environment. These Games were highly regionalised with competition venues in 13 Alpine communities spread over 1657 km, which necessitated an ambitious construction programme comprising sports facilities, hotels and roads. However, the accomplishment of these projects was conducted without due consideration for conservation of the natural environment. Sadly, it resulted in irreversible losses of massive forest areas and disturbance of wildlife (Girginov & Parry, 2005). Another example of Olympic Games that brought about damage to the natural environment is the 2004 Athens Summer Olympic Games. Construction of Olympic facilities for these games did not account for environmental aspects and resulted in careless destruction of open spaces that should have been kept as green spaces (Reyes, 2005). Other negative environmental impacts often reported in previous studies are associated with environmental pollution caused by trafc congestion during the construction of facilities in preparation of a mega sport event (Mihalik & Cummings, 1995; Fredline, 2004), parking problems during the event (Ritchie et al., 2009), and trafc congestion generated during refurbishing the transport infrastructure (Cashman, 2002). What is important to realise is that apart from the negative impact to the environment, pollution and congestion have a knock on effect on the well-being of local residents (Tatoglu & Erdal, 2002) whose support is of paramount importance for the success of an Olympic Games. In addition, environmental pollution may also act as a deterrent for visitors (Pyo et al., 1991) as has been reported for the city of Los Angeles that lost tourist visits during the 1984 Summer Olympic Games. The 1992 Winter Olympic Games environmental disaster signalled the need for an Olympic Games environmental policy. In 1996 the International Olympic Committee (IOC) established the Sport and Environment Commission that has since made environmental initiatives a standard requirement for Olympic Games organisers (Girginov & Parry, 2005). Even though there have been examples of environmentally friendly Olympic Games, it appears that environmental initiatives do not always

342

M. Konstantaki & E. Wickens

materialise according to plan. Following Londons winning bid to host the 2012 Games, the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) commissioned an assessment of the environmental impact of the London Games. Findings showed that, during the construction phase, deterioration of air quality, increased soil and ground water contamination, and disruption to existing ecosystems are to be anticipated, whereas during the Games, the transport movements of hundreds of thousands of athletes, ofcials, media, and spectators will cause congestion and pollution (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2005). However, this study was based on assessment of planning applications and therefore it does not reect residents perceptions of these key environmental issues. According to ARUP (2002), London will accommodate approximately 112 500 people for the duration of the 2012 Olympic Games, including 15 000 athletes, 7500 coaches, 20 000 journalists, 7000 sponsors and 63 000 operational personnel, whereas an estimated 9 million spectators are expected to attend the Games. London 2012 (2007) has announced that the transport needs of such huge numbers of visitors are to be served by an enhanced transport system for London that will deliver up to 240 000 people an hour to the Olympic Park by tube, train and bus, and via park-and-ride schemes making the 2012 Olympic Games the greenest Games in Olympic history. Contrary to the views of the organisers, there is evidence that Londoners have expressed concerns about the efciency of the new transport system, as well as concerns about the inconvenience to their daily lives such transport movements will create (BBC Sport, 2007). The magnitude of residents concerns about transportation needs to be explored further. In the published literature, environmental concerns about the 2012 Olympic Games have been identied by non-host city residents (Ritchie et al., 2009). This study provided useful insight into the perceptions of residents of two towns (Weymouth and Portland) in the south coast of England where sailing events are to be held. However, the views of residents who reside in London or in close proximity to the host city have not been investigated. To our knowledge, there are currently no published studies that have investigated the perceptions of local residents on the key environmental issues surrounding the 2012 London Olympic Games. Security Risks at the Olympic Games In recent years, the legacy of terrorist attacks attempted at Olympic Games (Munich 1972, Atlanta 1996) and at other non-event-related locations around the world has resulted in heightened attention to safety and risk-management strategies for sport events (Taylor & Toohey, 2007). To this effect, corporate spending has increased manifold to account for elaborate security checks during an Olympic Games (Hyman, 2002). It has been reported that the Salt Lake Olympic Committee received additional funds from the federal government and law agencies and enforcers were involved in the planning of security in preparation to host the 2002 Winter Games (Berta, 2001). In Sydney, in preparation for the 2000 Olympic Games, the New South Wales Government introduced special legislation that gave security forces the power to search

Journal of Sport & Tourism

343

citizens in the central district and to tap phones as a measure to enhance security (Chalip, 2002). In addition, an Olympic Intelligence Centre was created within the Organising Committee with the aid of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) that provided intelligence-based risk management identifying and prioritising all Games-related risks (Toohey, 2001). The 2004 Athens Summer Olympic Games were the rst to be held since the terrorist attack of 11 September 2001. Reyes (2005) reported that Athens was prepared as a potential battleground for the War on Terror with Patriot missiles, ghter planes and US battleships all on standby, whereas a bewildering array of security technologies (e.g. closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras, chemical sensors and a vast computer surveillance network) was also put in place. The Organising Committee for the 2004 Athens Olympic Games also ensured that stringent security checks were imposed during the games by US security stakeholders to alleviate growing concerns about international terrorism (Ford, 2005). The original gure for security expenditure that the Greeks put in their bid to host the 2004 Summer Games long before 11 September was US$122 million, but the gure wound up topping US$1.8 billion in contrast to Atlantas security tab of a paltry US$150 million (Cohn, 2005). Similarly, in preparation to host the 2008 Olympic Games, Beijing announced its plans for security maintenance that included security headquarters in every stadium and counterterrorist training for police units (Livingstone, 2007). There have been few studies that have investigated perceptions of visitors and spectators of security risks at sport events. Toohey et al. (2003) investigated the perceptions of visitors on security measures during the 2002 FIFA World Cup. Findings showed that dedicated sport tourists will travel to the event location regardless of perceived security risks and are appreciative of the security measures put in place as long as they do not detract sport tourists from enjoying the event. Nevertheless, this study did not include any respondents who decided not to attend the World Cup because of security risks. In another study, Taylor & Toohey (2007) explored spectators perceptions of terrorism threats at the 2004 Athens Olympic Games. Findings indicated that attendees who reported being fearful or feeling unsafe at the Games displayed increased risk estimates and associated concerns, whilst respondents expressing deance and anger produced opposite reactions with male respondents having less pessimistic risk perceptions than females. Also, Greek respondents reported fewer concerns for safety but greater awareness of the security measures. Miller et al. (2008) investigated spectator perceptions of security at the American Super Bowl after 9/11. Findings were similar to those reported by Toohey et al. (2003) in that 72% of respondents agreed that they would not change their travel plans even if the Department of Homeland Security raised the terrorist threat to red, whilst 96% perceived a strong likelihood that a terrorist attack would be attempted at the Super Bowl within ve years. These studies provided insight into perceptions of spectators and visitors and implications were made for event organisers. Security at the 2012 London Olympic Games is an issue of concern for the entire UK population. London has long lived under the spectre of terrorist threats from the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and has had a head start where security is concerned

344

M. Konstantaki & E. Wickens

boasting a surveillance network of 500 000 closed-circuit cameras already in place (Cohn, 2005). However, security became the epicentre of attention since the terrorist attack on Londons transport system on 7 July 2005 just two days after London won the bid to host the 2012 Summer Olympic Games. This attack, which claimed 56 lives, forced the Games organizers to take a fresh look at their plans for securing the city of 7.4 million people, and security experts stated that the original security budget of 200 million was far too low (Cohn, 2005). In 2007, the British government announced that the Olympic security budget had risen to triple its original estimate (Bignel, 2008). Yet in September 2008 it was announced that the London Olympics budget would break through the 10 billion barrier because ofcials had vastly underestimated the cost of protecting the event from terrorists (Bignel, 2008). This budget is considerably higher compared with the US$1.8 billion security budget that Greece allocated on security during the 2004 Athens Olympic Games (Miller, 2005). The London 2012 Organising Committee and the Olympic Delivery Authority have announced that security is to be built into the designs for the Olympic Park and venues and that dedicated intelligence units within the Police and the British Security Industry Association including a security steering group within the Home Ofce are in place (London 2012, 2007). In November 2009, Security Minister Lord West stated that the British government was viewing the potential threat at the 2012 Games as substantial instead of the previously advertised level of severe. It appears that the British government and the London Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games (LOCOG) have taken steps to ensure security measures for the 2012 Games and assessments of the risks of a disruption to the event, be it terrorism, a natural disaster, or an unruly fan, are already taking place (Cohn, 2005). These initiatives would benet from residents perceptions of security at the 2012 Olympic Games, which could offer vital insight for further planning and development. To our knowledge, there have been no published investigations of residents perceptions on security issues associated with the London 2012 Olympic Games. Therefore, the secondary aim of this study was to investigate residents perceptions of security risks at the London 2012 Olympic Games. Methods The research approach employed in this study involved the following steps. First, an extensive review of the literature was conducted to investigate residents perceptions of sport tourism and the environmental and security impacts of mega sport events in order to build the theoretical framework upon which to base the study. Second, content analysis of Olympic Games Impact Study (OGIS; PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2005), the Tourism Strategy for the 2012 Games (DCMS, 2007) and the BMRB Report Olympic Legacy Research (Smyth et al., 2007) was carried out to identify key environmental and security aspects at the 2012 London Olympic Games. Content analysis of the OGIS identied negative environmental impacts (transport, congestion, pollution and problematic parking) during the construction process and predicted positive impacts on the same areas during and after the Games (pp. 16 19).

Journal of Sport & Tourism

345

Content analysis of the Tourism Strategy for 2012 identied the issues of transport and security (p. 11) and a section on sustainable tourism where reducing the impact of visitor travel on the environment and creating green games is discussed (p. 15). Content analysis of the Olympic Legacy Research Report showed that one of the most important aims of Olympic Games delivery was environmentally friendly building development (p. 11) and that peoples second highest interest in the Games was linked to environmental issues (p. 14). Security concerns and related issues such as crime, terrorist activity and attendance levels at the Games have been identied in previous research by Toohey (2001), Toohey et al. (2003), Taylor & Toohey (2007), Ritchie et al. (2009) and Bob & Swart (2009). Third, this information was used to guide the design of the study instrument which formed the main method of data collection for the study and is described in the next section. The Study Instrument The study instrument employed a survey questionnaire. The design of the questionnaire was inuenced by literature suggesting that demographic characteristics constitute factors that inuence residents perceptions. Therefore, the rst section was designed to investigate respondents demographic characteristics (age, gender, occupation and levels of education). The second section of the survey investigated respondents awareness of 2012-related publicity in terms of planned initiatives discussed on radio and television programmes or publicised in newspapers, magazines and internet websites. The third section of the survey included questions on respondents perceptions of environmental pollution, congestion, public transportation, whereas the fourth section was designed to investigate views on security risks such as crime and terrorist actions in relation to the 2012 Games. In addition, respondents were asked to provide their views on the meaning of the London 2012 Olympic Games. A combination of multiple-choice closed-ended questions with scaled format and two open-ended questions were employed to elicit a range of representative responses. This design was adopted to allow respondents to produce standard responses and also express their views (Morrow et al., 2005). Respondents opinions of the environmental and security issues of the 2012 Olympic Games were assessed using an eight-item scale. Respondents were asked to rate their level of agreement or disagreement with each statement presented on a ve-point Likert type scale (1 Strongly disagree, 2 Disagree, 3 Neutral, 4 Agree, 5 Strongly agree). The use of a Likert-type scale in tourism research has been advocated due to its high validity (Ko & Stewart, 2002). Questionnaire Reliability and Validity To ensure the reliability of the questionnaire items, estimate stability reliability and exclude bias (Morrow et al., 2005), the researchers administered the questionnaire to the same group of respondents on two occasions spaced three weeks apart. This process formed part of the pilot study. Reliability analysis of the scale produced an alpha coefcient of 0.86 showing that the scale was reliable for the sample. The

346

M. Konstantaki & E. Wickens

wording of the questions was also checked to eliminate the possibility of respondents misinterpreting the questions. The validity of the questionnaire was assessed using a convenience sample of ve researchers, under survey conditions, to check the structure, wording and design of the questions for any source of bias and whether they relate to the theoretical construct of the study. The aim of the research was also explained to all respondents immediately prior to administering the questionnaire and the anonymity of responses was emphasised (Morrow et al., 2005). Study Area and Population Sample The surveyed population was selected from the town of High Wycombe which is located approximately 50 km west of London in the South East region of England. High Wycombe is the biggest town in the county of Buckinghamshire and one of the neighbouring towns to the host city of London. Buckinghamshire is heavily involved with the 2012 Olympic Games. This is evident from the wide range of Olympic-related activities that have taken place in the county since London won the bid to host the 2012 Games including conferences, courses, coach education seminars, sports ambassador schemes and several community projects (see http:// www.Bucks2012.com) led by the Bucks Sport Partnership in collaboration with LOCOG. Just a few miles west of High Wycombe is Stoke Mandeville Stadium, the birthplace of Paralympic sport, that will be home to the 2012 Paralympic Games and where the London 2012 ofcial mascots, Wenlock and Mandeville (named after the stadium), were launched in June 2010. The Olympic Lodge at Stoke Mandeville Stadium is a facility that has been developed to be used as a training centre for athletes in the run up and during the 2012 Games. Also, a team of academics from Buckinghamshire New University in High Wycombe is involved in the Bucks 2012 Steering Group. Therefore, the town of High Wycombe is central, or in close proximity, to many Olympic-related developments. It is anticipated that a population sample from this area would show high levels of awareness of 2012 Olympic issues and/or would have an interest of getting involved with business opportunities, volunteering or seeking employment at the Games. The survey was carried out during March and April 2008. The surveyed population comprised a convenience sample of 100 respondents of which 50 were young individuals (Group A; age range 18 34 years) and 50 were older participants (Group B; 3555 years). Even though this sample size might be considered small for drawing inferences or making generalisations about the population of High Wycombe, the focus of this research was to highlight differences or similarities in perceptions of young and older respondents using both quantitative and qualitative data from the survey. To this effect, the sample size was deemed appropriate to carry out the intended comparisons. One-third of the surveyed population lived or worked in London. Group A comprised 22.0% females and 88.0% males, of which 70.0% were students and 30.0% were in full-time employment. Group B consisted of 26.6% females and 73.4% males, of which 94.0% were in full-time employment and 6.0% were in part-time employment. All participants were briefed about the purpose of the study

Journal of Sport & Tourism

347

before completing the survey questionnaire. The authors recognise that a limitation in the sample of respondents was the considerably lower number of females compared with males which does not allow for gender comparisons within the research. However, gender is one factor that has been shown to inuence perceptions of residents toward sport tourism. Other factors such as age, socio-economic status and educational background also play an important role in shaping residents perceptions of sport events (Waitt, 2003; Ritchie et al., 2009) and these factors were investigated in the present study. Data Analysis Numerical data from the closed-ended questions were analysed via descriptive statistics using SPSS version 13.0. The mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for each question. The differences in the responses between the two age groups were assessed using paired t-tests. The level of statistical signicance was set at p , 0.05. Open-ended questions were analysed to identify data units (statements and sentences) and cluster them into common themes, utilising thematic analysis (Biddle et al., 2001). For this technique, similar data units were grouped together into rst-order (raw) themes and separated away from units with different meaning (positive versus negative themes). Direct quotes from the respondents were used to map the different themes. The frequency count of each theme was calculated to identify its importance compared with other themes in the same thematic group. The themes with the higher frequencies were selected as representative themes. Results The vast majority of respondents in both groups were male (Group A: 84.0%, Group B: 70.0%). Ninety-two per cent of respondents in Group A were between the ages of 18 and 24 years, whereas 64% or respondents in Group B were in the age range of 35 44 years. The majority of respondents in Group B (72.0%) and 58.0% of respondents in Group A resided in Buckinghamshire. Forty-two per cent of the young respondents and 28.0% of the older respondents lived in London. Seventy per cent of respondents in Group A were full-time students, whereas 94.0% of respondents in Group B were employed full-time. With regard to educational background, 64.0% of the young respondents had completed A-levels whereas 36.0% were university graduates. From the older respondents, 90.0% had a university degree and 10.0% possessed a postgraduate qualication. Both groups of respondents were equally aware of 2012related radio and television programmes (34.0% and 38.0% in Groups A and B, respectively), whereas both groups were least aware of posters on London buses and the Underground. The demographic prole of respondents is shown in Table 1. Thematic analysis revealed that the majority of respondents across both age groups supported the London 2012 Olympic Games. Support for the Games was stronger in the younger (94.0%) compared with the older (67.0%) age group. The reasons for which respondents in this study supported the Games centred around perceived

348

M. Konstantaki & E. Wickens Demographic prole of the population sample

Group A (18 29 years) Frequency (n) .0% 42 8 46 4 21 29 35 15 32 18 17 14 9 4 84.0 16.0 92.0 8.0 42.0 58.0 70.0 30.0 64.0 36.0 34.0 28.0 18.0 8.0 Group B (30 55 years) Frequency (n) .0% 35 15 6 32 12 14 36 47 3 45 5 19 7 16 8 70.0 30.0 12.0 64.0 24 28.0 72.0 94.0 6.0 90.0 10.0 38.0 14.0 32.0 16.0

Table 1

Demographic Variables Gender Male Female Age (years) 18 29 30 34 35 44 45 54 55 and over Residence London Buckinghamshire Occupation Full-time student Employed full-time Employed part-time Education A-levels University degree Postgraduate qualication Publicity awareness Radio/television programmes Websites Press Posters

benets of the Games even though these differed between the groups. The younger respondents supported the 2012 Games because they viewed them as a platform for generating new employment opportunities, improving the existing sporting and transportation facilities and an opportunity to boost the UK sporting prole. Some direct quotes of the young respondents included: The 2012 Olympic Games will help raise the prole of sporting events in the United Kingdom and will help with future bids for other sporting events such as the World Cup; I think the 2012 Games will be good for the economy and I would like a job there; and We need a big development for sport and the 2012 Olympics will create more facilities. The older respondents supported the 2012 Games because they perceived them as an opportunity to boost the UK economy, regenerate deprived areas, and ll the nation with pride and excitement. Older respondents stated: The 2012 Olympics are an excellent opportunity to strengthen the economy, enhance local resources and demonstrate to the world that the United Kingdom is capable of hosting this event. I think the spin offs will be

Journal of Sport & Tourism

349

tremendous!; The London Olympics will emphasize the importance of sport in the society; and The Games should bring improvements in transport and jobs to greater London. The percentage of respondents who were non-supporters of the 2012 Games was greater in the older (33.0%) compared with the younger (6.0%) age group. The ndings for residents support and non-support of the Games are presented in Figure 1. There were signicant differences between the age groups with regards to environmental pollution caused by event construction ( p 0.02), long-term environmental damage ( p 0.03) and parking problems during the Games ( p 0.04), whereas there were no differences between the groups on the issue of congestion ( p 0.08)

Figure 1 Respondents views on the meaning of the London 2012 Olympic Games to them. Frequency per cent of responses; a 33.0%, b 25.0%, c 13.0%, d 5.0% and e 4.0%.

350

M. Konstantaki & E. Wickens Resident perceptions of the environmental impact of the London 2012 Olympic

Group A (mean + SD) 3.27 + 1.30 3.33 + 1.22 2.66 + 1.02 1.78 + 0.89 1.66 + 1.41 Group B (mean + SD) 4.67 + 1.06a 4.18 + 0.98 3.8 + 1.11a 2.56 + 1.02a 1.62 + 1.14 Group A + B (mean + SD) 3.98 + 1.18b 3.75 + 1.1 3.23 + 1.06 2.17 + 0.95 1.64 + 1.27b A vs B (r) 0.94 0.67 0.52 0.83 0.98

Table 2 Games

Items

Construction of 2012 Olympic facilities will increase pollution Trafc congestion will increase during the London 2012 Games Londons urban environment will be negatively affected long-term Parking facilities will be adequate during the London 2012 Games Public transport will be adequate during the London 2012 Games

Note: aDifference between A and B; bdifference of A + B from neutral point 3; signicant at p , 0.05.

and transport ( p 0.06). Signicant correlations were identied in the perceptions of young and older respondents on the items of construction-related pollution (r 0.94) and transportation (r 0.98). The older residents in this study were more concerned with the short- and long-term environmental impacts of the Olympic Games on the city of London. The results also showed that when the mean was calculated for both groups (A plus B) signicant differences were only identied for constructionrelated pollution and transport from the neutral point 3 on the scale. The ndings of residents perceptions of environmental issues associated with the 2012 Olympics are shown in Table 2. Signicant differences were identied between the age groups on the issues of terrorist activity ( p 0.04) and attendance at the Olympics ( p 0.03), whereas there were no signicant differences between the age groups on the issues of increase in petty crime during the 2012 Olympics ( p 0.61) and LOCOGs ability to ensure security at the Games ( p 0.83). Signicant positive relationships were identied between the groups on the opinions of increases in petty crime (r 0.93) and LOCOGs ability to ensure security at the Games (r 0.89) which shows high agreement on these items between the groups. Inverse linear relationships were identied between the groups on the issues of terrorist activity (r 0.68) and attendance at the Games (r 0.57) which shows disagreement between the groups. When the mean of both groups was calculated signicant differences were identied between the group mean and the neutral point 3 on the scale for petty crime at the Games ( p 0.02). The ndings of residents perceptions on security risks associated with the 2012 Olympics are shown in Table 3.

Discussion The ndings of this study demonstrated that there were differences in residents perceptions of environmental and security issues at the 2012 London Olympic Games

Journal of Sport & Tourism Table 3

Items Petty crime will increase during the 2012 Olympics The London 2012 Olympics will attract terrorist activity Attendance at the 2012 Olympics will be low due to security risks LOCOG will ensure security at the 2012 Games

351

Residents perceptions of security risks at the London 2012 Olympic Games

Group A Group B Group A + B A vs B (mean + SD) (mean + SD) (mean + SD) (r) 4.10 + 0.64 3.22 + 1.30 3.62 + 0.82 3.33 + 1.13 4.28 + 0.73 4.42 + 0.50a 4.26 + 0.69 a 2.93 + 1.18 4.18 + 0.65b 3.96 + 0.98 3.74 + 0.81 3.05 + 1.03 0.93 0.68 0.57 0.89

Note: aDifference between A and B; bdifference of A + B from neutral point 3; signicant at p , 0.05.

between the age groups. Older residents possessed higher levels of education and socio-economic status compared with the young respondents and showed greater levels of concern and scepticism about these issues. These ndings conrm those of previous studies that have identied age as one of the factors that drives residents opinions (Mason & Cheyne, 2000; Tomljenovic & Faulkner, 2000; Johnson et al., 1994) and other studies that have linked higher levels of education (Fredline & Faulkner, 2000) and socio-economic status to residents negative predispositions toward an Olympic event (Waitt, 2003; Ritchie et al., 2009). Even though the population sample in this study was relatively small to make any generalisations it appears that older, educated and nancially secure individuals are more apprehensive with their feelings toward the London 2012 Olympics. It appears young respondents are more optimistic about an Olympic event mainly due to expectations of new employment opportunities. In this study, young respondents were on average more supportive of the Games compared with older residents. Similar ndings have been reported by Smyth et al. (2007) who showed that 90.0% of those aged 2434 years expressed enthusiasm about London being the host city whereas those aged 65 years and over were less positive about the 2012 Games. The reasons for supporting the Games were different between the age groups in this study. The young respondents supported the 2012 Games for the new employment opportunities they will generate, the improvements in sporting and transportation facilities and because they will raise the national sporting prole. The older respondents perceived the Games as an opportunity to improve the UK economy, regenerate deprived areas and ll the nation with pride and excitement. These results agree with those stated by Gursoy & Kendall (2006) who proposed that residents support relies heavily on perceived benets. This study was conducted four years prior to the London 2012 Olympics and showed strong resident support for the 2012 Games. This nding concurs with those stated previously for resident support by Mihalik (2000) four years prior to the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, by Bob & Swart (2009) two years prior to the 2010 FIFA World Cup, and by Ritchie et al. (2009) ve years prior to the 2012 London Olympics.

352

M. Konstantaki & E. Wickens

Another notable nding in this study was that the percentage of respondents who were non-supporters of the 2012 Games was greater in the older compared with the younger age group. This nding coincides with that stated by Smyth et al. (2007) where the percentage of ignorers, i.e. those neither interested nor pleased about London hosting the Games was higher among older people. In this study, there were also differences in the reasons provided by each group for not supporting the 2012 Games. Young respondents stated that they did not support the 2012 Games because of perceived increases in prices for goods and travel and because they could not link the Games with immediate employment, whereas older respondents stated the increases in taxation, the negative impact to the environment and the possibility that the Games might attract terrorist activity. Several researchers have reported that environmentally conscious residents do not support the Olympic Games (Mason & Cheyne, 2000; Deccio & Baloglu, 2002; Ritchie et al., 2009) and that those residents who are negatively predisposed to an Olympic event are concerned about security issues (Mihalik & Simonetta, 1999). There were differences in the perceptions of young and older residents on environmental issues at the 2012 Games such as pollution caused by event construction, longterm environmental damage and parking problems with older residents showing consistently more negative attitudes. This nding agrees with those stated previously by Fredline & Faulkner (2000) who found that residents with average age of 53.5 years are those who tend to associate the Olympics with noise, trafc, disruption and reduced quality of life. Similarly, Ritchie et al. (2009) stated that those aged between 18 and 25 years are more likely to agree with the positive social impacts of a mega sport event compared with those aged between 46 and 65 years of age who perceive mostly negative environmental impacts. Our study was conducted four years prior to the London 2012 Olympic Games and our ndings on residents concerns about trafc congestion compare well with those reported in other studies that have been conducted several years prior to mega sport events (Mihalik, 2000; Bob & Swart, 2009). Surprisingly both groups in this study demonstrated negative attitudes toward transportation which shows that this is indeed a matter of great concern irrespective of age. Respondents felt it is unlikely that the planned improvements in transport infrastructure will be adequate in creating a safe and effective transport system for the 2012 Olympic Games. Ritchie et al. (2009) in their study of resident perceptions of transportation at the 2012 Olympic venues of Portland and Weymouth also reported similar concerns. These ndings contrast LOCOGs planned developments to improve the transport infrastructure that are currently underway. However, there is evidence that the British government has previously managed to update successfully Manchesters transport system in preparation for the 2002 Manchester Commonwealth Games (DCMS, 2002). Residents perceptions of security issues in this study showed differences between the age groups. Older residents were more concerned about the Games attracting terrorist activity and that attendance at the Games would be low because of security risks compared with the young respondents. Concerns about security have been identied in the run up to 2004 Athens Olympic Games (Ford, 2005) and the American Super

Journal of Sport & Tourism

353

Bowl (Miller et al., 2008). Mihalik & Simoneta (1999) noted that projected attendance at the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games would decrease progressively throughout the four years leading up to the event, although they did not relate this nding to concerns about security at the time. Another study that assessed perceptions of attendees at the 2004 Olympics reported a relationship between being fearful or feeling unsafe at the Games and concerns about security risks (Taylor & Toohey, 2007). Both groups in this study were equally concerned about increases in petty crime during the Games. Residents concerns about crime at an Olympic event have been previously reported by Ritchie & Aitken (1985) in their Olympulse II research of the 1988 Winter Olympic Games, by Mihalik (2000) in his study of the Atlanta 1996 Olympics, and more recently by Bob & Swart (2009) in their study of the 2010 FIFA World Cup. There were no differences between the groups on LOCOGs ability to ensure security at the Games. However, young respondents appeared to be mostly neutral, whereas mature respondents mostly disagreed with this statement. This nding shows that mature residents are concerned that LOCOG will not be able to ensure the security of visitors and spectators at the 2012 Olympics. The importance of implementing security measures to ensure a safe Olympic games has been highlighted previously by Hyman (2002) and Chalip (2002) and LOCOG has undertaken a number of risk assessments to ensure security arrangements at the 2012 Games including increasing the security budget to 600 million in 2007 (BBC Sport, 2007), creating intelligence units and a security steering group (London 2012, 2007). Conclusion and Implications The ndings of this study showed that the majority of respondents in both age groups supported the London 2012 Olympic Games and were relatively aware of 2012-related publicity, however there were notable differences between the groups in their perceptions of environmental impacts and security risks. Overall, the young respondents demonstrated more positive attitudes compared with older respondents. The younger respondents supported the 2012 Games in anticipation of new employment opportunities, whereas the older group associated the Games with national pride and excitement. In spite of their support for the event, it appears that the older respondents in this study view it with more scepticism when considering environmental and security issues compared with their younger counterparts. The perceptions of respondents in this study about transportation are not encouraging, which is disappointing given the recent developments in transport modes (Purnell, 2007). Heathrow Airport Terminal 5 and the new Eurostar terminal at St. Pancras in London are already operational and there are concrete plans to improve inbound transport with the Mayor of London taking forward a ve-year, 10 billion investment programme to improve rail, tube and the Docklands Light Railway (Purnell, 2007). It is evident that the British government is taking serious steps in materialising the renovation of London transport given its high priority in view of the Olympic time scales. It might be the case that the respondents in this study were not aware of such developments even though they were aware of other

354

M. Konstantaki & E. Wickens

publicity relating to the 2012 Olympic Games. Certainly, such plans need to be disseminated to the wider public through media exposure or other plausible means to raise awareness of developments and dissipate false or inaccurate perceptions. The most preferred publicity method for both groups of respondents in this study was radio and televised programmes. It might be useful to increase the dissemination of information through these routes in the run up to the London 2012 Olympic Games. Even though our ndings are in agreement with ndings of previous studies, they are surprising given the planning undertaken by the British government and 2012 stakeholders to ensure environmental sustainability and security at the London 2012 Olympic Games. It may have been the case that respondents were not fully aware of the magnitude of developments taking place in the run up to the Olympic Games, since there is limited consultation with the public and involvement in the different phases of initiative implementation. This is not a one-off phenomenon. Smyth et al. (2007) stated that only 37.0% of the surveyed population were aware of environmentally friendly building developments and concluded that people perhaps need more inspiration, belief and knowledge about other aims that the Games will achieve besides job creation, business opportunities and young peoples involvement in the community. Bob & Swart (2009) also reported little public awareness and participation in the planning process of stadia development for the 2010 FIFAWorld Cup. Environmental and security initiatives relating to the 2012 Olympic Games are publicised in the 2012 website and appear in press releases (Bignel, 2008). However, the ndings of this study indicate that greater effort needs to be made to educate the public and keep them abreast of developments so that to dispel fears, misconceptions and instil positive attitudes. The ndings of this study call for consideration by the 2012 London Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games (LOGOC), the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), and other stakeholders involved in environmental and security planning. Even though the perceptions of this population cannot be directly generalised to reect perceptions of the people in Buckinghamshire, they can serve as a case study upon which further research can be based.

References

ARUP (2002). London Olympics 2012: costs and benets summary. ARUP and Insignia Richard Ellis. Retrieved May 21 2002 from http://www.arup.com/_assets/_download/download368.pdf/. Baloglu, S., & McClearly, K.W. (1999). A model of destination image formation. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(4), 868897. BBC Sport. (2005). BBC Sport: 2012 London Olympics. July 6 2005. Berta, D. (2001). Salt Lake ramps up Olympics security in wake of terror attacks. Nations Restaurant News, October 15 2001. Retrieved from http://ndarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m3190/is_/ai_ 79210879/. Biddle, S., Markland, D., Gilbourne, D., Chatzisarantis, N., & Sparkes, A. (2001). Research methods in sport and exercise psychology: quantitative and qualitative issues. Journal of Sports Sciences, 19, 777809. Bignel, P. (2008). Security bill for Londons 2012 Olympics to hit 1.5bn triple the original estimate. Independent on Sunday September 8 2008.

Journal of Sport & Tourism

355

Bob, U., & Swart, K. (2009). Resident perceptions of the 2010 FIFA Soccer World Cup Stadia development in Cape Town. Urban Forum, 20, 4759. Cashman, R. (2002). Global games: from the ancient games to the Sydney Olympics. Sporting Traditions, 19(1), 7584. Chalip, L.H. (2002). Using the Olympics to optimise tourism benets. Paper presented as part of a `s Ol `mpics, Universitat Auto ` nseries of university lectures on the Olympics, Centre dEstud oma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. Retrieved from http://olympicstudies.uab.es/lectures/ web/pdf/. Chon, K.S. (1992). The role of destination image in tourism: an extension. Tourist Review, 2, 27. Cohn, L. (2005). For London, what price for Olympic security? After the bombings, Londons estimate for the 2012 games seems way too low. Business Week, August 15. Deccio, C., & Baloglu, S. (2002). Non-host community resident reactions to the 2002 Winter Olympics: the spillover impacts. Journal of Travel Research, 41(1), 4656. Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) (2002). Revisiting the Manchester 2002 Commonwealth Games: government response to the 5th Report from the DCMS Select Committee Session. Norwich: TSO. Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) (2007). Winning: a tourism strategy for 2012 and beyond, Executive Summary, September 2007/PP1066. London: DCMS. Dodouras, S., & James, P. The sustainability impacts of mega-sport events. Paper presented at the International Association for Impact Assessment Conference (IAIA), The Hague, the Netherlands, June 18, 2002. Retrieved from http://www.els.salford.ac.uk/urbannature/ research/. Essex, S., & Chalkley, B. (1998). Olympic Games: catalyst for urban change. Leisure Studies, 17, 187206. Ford, J.T. (2005). Olympic security: US support to Athens Games provides lessons for future Olympics: GAO-05-547. Retrieved from http://www.gao.gov/highlights/d0554high.pdf/. Fredline, E. (2004). Host community reactions to motorsports events: the perception of impact on quality of life. In B.B.W. Ritchie & D. Adair (Eds.), Sport tourism: interrelationships, impacts and issues. Clevedon Hall: Channel View. Fredline, E., & Faulkner, B. (2000). Community perceptions of the impacts of events. In J. Allen, R. Harris, L.K. Jago & A.J. Veal (Eds.), Events beyond 2000: setting the agenda. Proceedings of conference on Event Evaluation, Research and Education, pp. 6672. Sydney: Australian Centre for Event Management. Retrieved from http://www.business.uts.edu.au/acem/pdfs/ Events2000_nal/. Fredline, E., & Faulkner, B. (2002). Variations in residents reactions to major motorsport events Why residents perceive the impacts of events differently. Event Management, 7(2), 115 126. Girginov, V., & Parry, J. (2005). The Olympic Games explained: a student guide to the evolution of the modern Olympic Games. London: Routledge. Gursoy, D., & Kendall, K.W. (2006). Hosting mega events: modelling locals support. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(3), 603623. Gursoy, D., Jurowski, C., & Uysal, M. (2002). Resident attitudes: a structural modelling approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(1), 79105. Hall, C.M. (2004). Sport tourism and urban regeneration. In B.W. Ritchie & D. Adair (Eds.), Sport tourism: interrelationships, impacts and issues. Clevedon Hall: Channel View. Johnson, J., Snepenger, D., & Akis, S. (1994). Residents perceptions of tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research, 21(3), 629637. Jones, M., & Stokes, T. (2003). The Commonwealth Games and urban regeneration: an investigation into training initiatives and partnerships and their effects on disadvantaged groups in East Manchester. Managing Leisure, 8, 198211. Kim, S., & Petrick, J. (2005). Residents perceptions on impacts of the FIFA 2002 World Cup: the case of Seoul as the host city. Tourism Management, 26, 3538.

356

M. Konstantaki & E. Wickens

Ko, D.W., & Stewart, W.P. (2002). A structural equation model of residents attitudes for tourism development. Tourism Management, 23(5), 521530. Livingstone, K. (2007). The 2012 Olympic Games and crime, policing and emergencies. Retrieved from http://www.london.gov.uk/mayor/olympics/benets-crime.jsp/. London 2012 (2007). Environmental sustainability. Retrieved from http://www.london2012.com/ making-it-happen/sustainability/environmental-monitoring/index.php/. Mason, P., & Cheyne, J. (2000). Residents attitudes to proposed tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research, 27(2), 391411. Matheson, V.A., & Baade, R.A. (2004). Mega-sporting events in developing nations: playing the way to prosperity? Faculty Research Working Series Paper No. 04-04. Worcester, MA: Department of Economics, College of the Holy Cross. Retrieved from http://academics.holycross.edu/les/ econ_accounting/Matheson_Prosperity.pdf/. Mihalik, B.J. (2000). Host population perceptions of the 1996 Atlanta Olympics: attendance, support, benets and liabilities. In J. Allen, R. Harris, L.K. Jago & A.J. Veal (Eds.), Events beyond 2000: setting the agenda, Proceedings of Conference on Event Evaluation, Research and Education, pp. 134138. Sydney: Australian Centre for Event Management. Retrieved from http://www.business.uts.edu.au/acem/pdfs/Events2000_nalversion.pdf/. Mihalik, B.J., & Cummings, P. (1995). Host perceptions of the 1996 Atlanta Olympics: support, attendance, benets and liabilities. Travel and Tourism Research Association 26th Annual Proceedings, pp. 397 400. Mihalik, B.J., & Simonetta, L. (1999). A midterm assessment of the host populations perceptions of the 1996 Summer Olympics: support, attendance, benets, and liabilities. Journal of Travel Research, 37(3), 244248. Miller, J., Veltri, F., & Gillentine, A. (2008). Spectator perceptions of security at the Super Bowl after 9/11: implications for sport facility managers. Smart Journal, 4(2), 1625. Miller, J.W. (2005). Tab for 2004 Summer Olympics weighs heavily on Greece. Wall Street Journal Eastern Edition, 245(92), B1B2. Morrow, J.R., Jackson, A.W., Disch, J.G., & Mood, D.P. (2005). Measurement and evaluation in human performance (3rd ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Mules, T., & Faulkner, B. (1996). An economic perspective on special events. Tourism Economics, 2(2), 107117. Ohmann, S., Jones, I., & Wilkes, K. (2006). The perceived social impacts of the 2006 Football World Cup on Munich residents. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 11(2), 129152. PricewaterhouseCoopers (2005). Olympic Games impact study. Final Report. London: Government and Public Sector prepared for the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). Retrieved from http://www.culture.gov.uk/reference_library/pub/. Purnell, J. (2007). Winning: a tourism strategy for 2012 and beyond. Executive Summary prepared for the DCMS, Visit Britain and Visit London. September 2007/PP1066. London. Retrieved from http://www.culture.gov.uk/what_we_do/. Pyo, S., Cook, R., & Howell, R.L. (1991). Summer Olympic tourist market. In S. Medlik (Ed.), Managing tourism, pp. 191198. London: Butterworth-Heinemann. Reyes, O. (2005). The Olympics and the City. The Olympics and the City. Red Pepper Magazine. April 1. Retrieved from http://www.redpepper.org.uk/article555.html/. Ritchie, B.W., & Adair, D. (2004). Sport tourism: interrelationships, impacts and issues. Clevedon Hall: Channel View. Ritchie, B.W., Shipway, R., & Cleeve, B. (2009). Resident perceptions of mega-sporting events: a non-host city perspective of the 2012 London Olympic Games. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 14(2/3), 143167. Ritchie, J.R. B., & Aitken, C.E. (1985). Olympulse II evolving resident attitudes toward the 1988 Olympic Winter Games. Journal of Travel Research, 23(3), 2833.

Journal of Sport & Tourism

357

Ritchie, J.R. B., & Smith, B.H. (1991). The impact of a mega-event on host region awareness: a longitudinal study. Journal of Travel Research, 30(1), 310. Smyth, J., Mason, J. & Gilby, N. (2007). Olympic legacy research. Quantitative report prepared for COI and DCMS. London: British Market Research Bureau (BMRB) Sport. Retrieved from http://www.culture.gov.uk/images/publications/researchreport.pdf/. Standeven, J., & deKnop, P. (1999). Sport tourism. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Tatoglu, E., & Erdal, F. (2002). Resident attitudes toward tourism impacts: the case of Kusadasi in Turkey. International Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Administration, 3(3), 79100. Taylor, T., & Toohey, K. (2007). Perceptions of terrorism threats at the 2004 Olympic Games: implications for sport events. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 12(2), 99114. Tomljenovic, R., & Faulkner, B. (2000). Tourism and older residents in a sunbelt resort. Annals of Tourism Research, 27(1), 93114. Toohey, K. (Ed.). (2001). The Ofcial Report of the Games of the XXVII Olympiad. Sydney: SOCOG. Toohey, K., Taylor, T., & Choong-Ki, L. (2003). The FIFA World Cup 2002: The effects of terrorism on sport tourists. Journal of Sport and Tourism, 8(3), 167185. Waitt, G. (2003). The social impacts of the Sydney Olympics. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(1), 194215.

Você também pode gostar

- Train 400/800 Runner Aerobic & AnaerobicDocumento20 páginasTrain 400/800 Runner Aerobic & AnaerobicCoachJDutch50% (2)

- ISL (Indian Super League)Documento3 páginasISL (Indian Super League)gvspavanAinda não há avaliações

- 39 - Buckling & Wellhead Load After CementingDocumento2 páginas39 - Buckling & Wellhead Load After CementingAbdul Hameed OmarAinda não há avaliações

- Woody 400 M HurdlesDocumento24 páginasWoody 400 M HurdlesAnonymous 45e6vn100% (2)

- Driver Stats: Meaning and EffectsDocumento2 páginasDriver Stats: Meaning and Effectstmüntzer50% (2)

- Legacy Sports MegaEventsDocumento13 páginasLegacy Sports MegaEventsTonyCalUSM100% (2)

- Buy Sell TargetDocumento5 páginasBuy Sell TargetSuresh Ram R100% (1)

- 80 Hurdle Trainig WorkoutDocumento2 páginas80 Hurdle Trainig WorkoutNixon Ernest100% (1)

- Liverpool FC History: From Founding in 1892 to European Domination Under PaisleyDocumento21 páginasLiverpool FC History: From Founding in 1892 to European Domination Under PaisleyRobert GeorgeAinda não há avaliações

- Marathon ProposalDocumento2 páginasMarathon ProposalThilagavathiAinda não há avaliações

- Visitor Safety in Urban Tourism Environments: The Case of Auckland, New ZealandDocumento10 páginasVisitor Safety in Urban Tourism Environments: The Case of Auckland, New ZealandLogeswaran TangavelloAinda não há avaliações

- Volunteers and Mega Sporting Events Developing ADocumento13 páginasVolunteers and Mega Sporting Events Developing Aaleestudiando01Ainda não há avaliações

- Hinch 2016Documento12 páginasHinch 2016lip sAinda não há avaliações

- Kenyon 2017Documento18 páginasKenyon 2017Ayeshy gulAinda não há avaliações

- Sustainability 05 03581Documento20 páginasSustainability 05 03581MD ASAD KHANAinda não há avaliações

- Environmental Sustainability of Olympic Games: June 2018Documento12 páginasEnvironmental Sustainability of Olympic Games: June 2018goncalopesAinda não há avaliações

- Mega Events Economic Impact FIFA 2002 30.10.Documento9 páginasMega Events Economic Impact FIFA 2002 30.10.LukaAinda não há avaliações

- Sport Tourism Impact On Local Communities 1 - LibreDocumento11 páginasSport Tourism Impact On Local Communities 1 - LibreEdmond-Cristian PopaAinda não há avaliações

- CashmanDocumento16 páginasCashmanprongmx100% (1)

- Perception Towards Climate Change ItDocumento4 páginasPerception Towards Climate Change Itpaul abitonaAinda não há avaliações

- Sociology: Towards A Sociological Analysis of London 2012Documento17 páginasSociology: Towards A Sociological Analysis of London 2012Guilherme Ferreira SantosAinda não há avaliações

- P304616 - JanCohort - Kevin O'HanlonDocumento12 páginasP304616 - JanCohort - Kevin O'Hanlonlucas salmon hernandezAinda não há avaliações

- Considering Legacy As A Multi-Dimensional ConstructDocumento15 páginasConsidering Legacy As A Multi-Dimensional ConstructLasan Formatações AbntAinda não há avaliações

- Sport Management Review: James Andrew Kenyon, Guillaume BodetDocumento18 páginasSport Management Review: James Andrew Kenyon, Guillaume BodetHAO HO VANAinda não há avaliações

- Impacts of Sport Tourism in The Urban Regeneration of Host Cities (The Case of Sheffield)Documento15 páginasImpacts of Sport Tourism in The Urban Regeneration of Host Cities (The Case of Sheffield)Jobi W. OlukoyaAinda não há avaliações

- A Framework For Monitoring During The Planning Stage For A Sports Mega EventDocumento19 páginasA Framework For Monitoring During The Planning Stage For A Sports Mega EventZoe SiuAinda não há avaliações

- Tourism Management Perspectives: A B C ADocumento3 páginasTourism Management Perspectives: A B C APika SeptianiAinda não há avaliações

- Royal Institute of International Affairs, Oxford University Press International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-)Documento18 páginasRoyal Institute of International Affairs, Oxford University Press International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-)Sysy DianitaaAinda não há avaliações

- Tour Lit RevDocumento28 páginasTour Lit Revhtineza18Ainda não há avaliações

- LIS 2022 New 1-208-214Documento7 páginasLIS 2022 New 1-208-214Lppm Politeknik JambiAinda não há avaliações

- Assessing Environmental Pollution Risk from Tourism in Shahrood CountyDocumento11 páginasAssessing Environmental Pollution Risk from Tourism in Shahrood CountySHOEB AHMEDAinda não há avaliações

- TR 10 2019 0424Documento5 páginasTR 10 2019 0424Yoki AfriandyAinda não há avaliações

- Effects of Tourism on Environment, Society and EconomyDocumento9 páginasEffects of Tourism on Environment, Society and EconomyIzzat AmarAinda não há avaliações

- 1.1 The Impacts Generated From Hosting Major EventsDocumento5 páginas1.1 The Impacts Generated From Hosting Major Eventssurbhi kumariAinda não há avaliações

- Cherubini IasevoliDocumento17 páginasCherubini IasevoliCucu BauAinda não há avaliações

- Urban Strategies and Post-Event Legacy: The Cases of Summer Olympic CitiesDocumento25 páginasUrban Strategies and Post-Event Legacy: The Cases of Summer Olympic Citiestux52003Ainda não há avaliações

- Adventure Tourism Research GuideDocumento20 páginasAdventure Tourism Research Guidejfk100Ainda não há avaliações

- An Empirical Model of Attendance Factors at Major Sporting EventsDocumento7 páginasAn Empirical Model of Attendance Factors at Major Sporting EventsIoanna DarmarakiAinda não há avaliações

- Olympics DissertationDocumento5 páginasOlympics DissertationBestOnlinePaperWritingServiceUK100% (1)

- Frame WorkDocumento8 páginasFrame WorkMohammed Rasoul TarawnehAinda não há avaliações

- Final Version Lotte Drost Bachelor ProjectDocumento20 páginasFinal Version Lotte Drost Bachelor ProjectSeducatorulAinda não há avaliações

- Clarke 2016 From Maladaption To AdaptionDocumento12 páginasClarke 2016 From Maladaption To AdaptionJonathan ClarkeAinda não há avaliações

- Economic Impact of The Sydney Olympic Games: January 1998Documento28 páginasEconomic Impact of The Sydney Olympic Games: January 1998SashaFierce Los A&AAinda não há avaliações

- Roles and Functions of FestivalsDocumento5 páginasRoles and Functions of FestivalsCristina Rodica100% (1)

- Olympics CFPDocumento1 páginaOlympics CFPFórum de Desenvolvimento do RioAinda não há avaliações

- Mega Sporting Events DissertationDocumento6 páginasMega Sporting Events DissertationNeedHelpWithPaperErie100% (1)

- Assessing The Olympic Games The Economic Impact AnDocumento35 páginasAssessing The Olympic Games The Economic Impact AnPhikkipAinda não há avaliações

- Sports Events and Risk Management inDocumento33 páginasSports Events and Risk Management inAnna Krawontka0% (1)

- Exploring The Covid-19 Pandemic As A Catalyst For: Event Management, Vol. 24, Pp. 537-552Documento17 páginasExploring The Covid-19 Pandemic As A Catalyst For: Event Management, Vol. 24, Pp. 537-552Hany A AzizAinda não há avaliações

- Olympic Infrastructure-Global Problems of Local Communities On The Example of Rio 2016, Pyeongchang 2018, and Krakow 2023Documento19 páginasOlympic Infrastructure-Global Problems of Local Communities On The Example of Rio 2016, Pyeongchang 2018, and Krakow 2023SHERELYN ROBLESAinda não há avaliações

- Unethical Hotel Practices That Cause Consumer BoycottsDocumento9 páginasUnethical Hotel Practices That Cause Consumer BoycottsAru BhartiAinda não há avaliações

- Benefits of Hosting The OlympicsDocumento9 páginasBenefits of Hosting The Olympicsapi-282770615100% (1)

- APJIHT RiskIssuesof29thSEAGamesDocumento17 páginasAPJIHT RiskIssuesof29thSEAGamesYiwobipAinda não há avaliações

- Sustainable Development - 2008 - Timur - Sustainable Tourism Development How Do Destination Stakeholders PerceiveDocumento13 páginasSustainable Development - 2008 - Timur - Sustainable Tourism Development How Do Destination Stakeholders PerceiveMaryam KhaliqAinda não há avaliações

- Harris and BusbyDocumento3 páginasHarris and BusbyCam LembergAinda não há avaliações

- Media and the Political Economy of SportDocumento37 páginasMedia and the Political Economy of SportKaplan GenadiAinda não há avaliações

- MPRA Paper 37506Documento29 páginasMPRA Paper 37506Geraldz Brenzon AgustinAinda não há avaliações

- 2-3-Leveraging Accessible TourismDocumento15 páginas2-3-Leveraging Accessible TourismMahmoud AhmedAinda não há avaliações

- Tourism Industry in East AfricaDocumento14 páginasTourism Industry in East AfricaMERLIN UGAinda não há avaliações

- Literature Review Chapter - 2Documento20 páginasLiterature Review Chapter - 2Revathy seetharamanAinda não há avaliações

- Cape Town and The Two Oceans Marathon - The Impact of Sport TourismDocumento12 páginasCape Town and The Two Oceans Marathon - The Impact of Sport TourismEdmur Antonio StoppaAinda não há avaliações

- To What Extent Does New York City Need To Adapt To Climate ChangeDocumento10 páginasTo What Extent Does New York City Need To Adapt To Climate ChangeKrish BabuAinda não há avaliações

- The Commonwealth GamesDocumento10 páginasThe Commonwealth GamesSandeep ParmarAinda não há avaliações

- Jennings 2008 Olympic RiskDocumento10 páginasJennings 2008 Olympic RiskSANTOSH KEKANEAinda não há avaliações

- 581-Article Text-1948-1-10-20221112Documento12 páginas581-Article Text-1948-1-10-20221112lkspecAinda não há avaliações

- Cultural Differences in Travel Risk PerceptionDocumento20 páginasCultural Differences in Travel Risk PerceptionEsther Charlotte Williams100% (2)

- Ethical Orientation and Awareness of Tourism StudentsDocumento43 páginasEthical Orientation and Awareness of Tourism StudentsKikoTVAinda não há avaliações

- Review of LiteratureDocumento12 páginasReview of LiteratureIan HenleyAinda não há avaliações

- Tourism Enterprise: Developments, Management and SustainabilityNo EverandTourism Enterprise: Developments, Management and SustainabilityAinda não há avaliações

- City Development VisionsDocumento16 páginasCity Development VisionsdonatelojAinda não há avaliações

- Jennings R R LondonRiskDocumento6 páginasJennings R R LondonRiskNermino KaradžaAinda não há avaliações

- Jajce FinalDocumento20 páginasJajce FinaldonatelojAinda não há avaliações

- City Development VisionsDocumento16 páginasCity Development VisionsdonatelojAinda não há avaliações

- Nra Ssusa 201206Documento44 páginasNra Ssusa 201206whi7efea7herAinda não há avaliações

- AthleticsDocumento37 páginasAthleticsapi-234545368100% (1)

- Sports Reporter: and Captures The Triple Crown Shoot-OutDocumento8 páginasSports Reporter: and Captures The Triple Crown Shoot-OutSportsReporterAinda não há avaliações

- BADMINTON Was Invented Long Ago A Form of Sport Played in Ancient Greece andDocumento5 páginasBADMINTON Was Invented Long Ago A Form of Sport Played in Ancient Greece andjanelaroxan100% (1)

- ABC2000b-Click To StartDocumento138 páginasABC2000b-Click To StartpautracAinda não há avaliações

- Arcadia Invitational Heat SheetsDocumento25 páginasArcadia Invitational Heat SheetsILMilesplitAinda não há avaliações

- Women's World Chess Championship - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia PDFDocumento5 páginasWomen's World Chess Championship - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia PDFVBuga84Ainda não há avaliações

- NCHSAA 2A Midwest Regional - Preliminary Entry ListDocumento13 páginasNCHSAA 2A Midwest Regional - Preliminary Entry ListJosh PardueAinda não há avaliações

- Asian GamesDocumento17 páginasAsian Gamesamanblr12Ainda não há avaliações

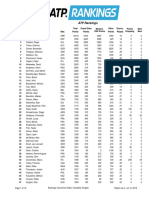

- ATP Tennis Player Rankings as of July 15, 2019Documento15 páginasATP Tennis Player Rankings as of July 15, 2019AlbertoAinda não há avaliações

- 2014 St. Kitts and Nevis Carifta Trials ResultsDocumento4 páginas2014 St. Kitts and Nevis Carifta Trials Resultsscotty_hanley5303Ainda não há avaliações

- Badminton Dec2005Documento48 páginasBadminton Dec2005Stephane HoAinda não há avaliações

- Perf ListDocumento21 páginasPerf ListcoachkinneyAinda não há avaliações

- 2012-2013 DMA RanksDocumento5 páginas2012-2013 DMA RanksAdweekAinda não há avaliações

- The Modern Olympic GamesDocumento5 páginasThe Modern Olympic GamesThijs SmetAinda não há avaliações

- Questions On Fifa World Cup FootballDocumento2 páginasQuestions On Fifa World Cup Footballrs0728Ainda não há avaliações

- Peter Hargitay ReportDocumento16 páginasPeter Hargitay ReportEmanuel RAinda não há avaliações

- Justine Salata Resume PDFDocumento1 páginaJustine Salata Resume PDFapi-301937108Ainda não há avaliações

- Kedudukan Atletik Lumba Jauh dan LompatDocumento4 páginasKedudukan Atletik Lumba Jauh dan LompatMuhammad Al-FatehAinda não há avaliações

- Strong Man Criteria and CareDocumento8 páginasStrong Man Criteria and CareAkash KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 9Documento12 páginasUnit 9Abdou RamziAinda não há avaliações