Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Nicd NHLS

Enviado por

Neo Mervyn MonahengTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Nicd NHLS

Enviado por

Neo Mervyn MonahengDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Festschrift : Outbreaks in South Africa 2004-2011

Outbreaks in South Africa 2004-2011, the Outbreak Response Unit of the NICD, and the vision of an inspired leader

L Blumberg, G de Jong, J Thomas, BN Archer, A Cengimbo, C Cohen

Lucille Blumberg, Gillian de Jong, Juno Thomas, Brett Archer, Ayanda Cengimbo, Cheryl Cohen Epidemiology Division, National Institute for Communicable Diseases, National Health Laboratory Service, Johannesburg. Correspondence to: Prof L Blumberg, NICD, 1 Modderfontein Road, Sandringham 2192 Johannesburg, E-mail: lucilleb@nicd.ac.za

The Outbreak Response Unit was established in 2004 by Prof Barry Schoub and was envisioned as a comprehensive unit for reporting of suspected communicable disease outbreaks, and for the provision of technical support for outbreak response within South Africa and the region, with special emphasis on optimising the role of the laboratory. The unit has grown in size and broadened in scope and expertise over the past seven years, and has responded to complex, high-profile and large outbreaks, including highly pathogenic influenza A H5N2 affecting ostriches, the new arenavirus (Lujo), cholera, the 2009 influenza pandemic, emergence of rabies in Limpopo province and Rift Valley fever, among many others.

SAJEI South Afr J Epidemiol Infect 2011;26(4)(Part I):195-197

Introduction

This article pays tribute to Prof Barry D Schoub, whose vision as the founding director of the National Institute of Communicable Diseases (NICD) led to the establishment of an Outbreak Response Unit (ORU) within the Epidemiology Division. This decision followed on the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003 and the recognition of the need for a dedicated unit for development of early warning systems, reporting and verification of suspected outbreaks and coordination of responses, particularly laboratory-related, and for providing technical support to partners within the public health sector. In the subsequent years a significant number of communicable disease outbreaks occurred, many of them high profile, both within the southern African region and within the international community. This article will briefly describe a number of key outbreaks and highlight the role of the ORU in building on Prof Schoubs vision

negative.3 The outbreak response activities developed for this outbreak at NICD-NHLS were the basis of future outbreak responses by the NICD-NHLS, including providing of clinical guidelines, establishing systems for screening of suspected cases for laboratory testing, establishing media links and communications, and forming working partnerships with the national and provincial health departments and public health and laboratory institutions internationally.

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAIH5N2), 2004

In 2004, the first outbreak of HPAI (H5N2) in South Africa was reported on two ostrich farms in the Eastern Cape province, with mortality rates of up to 60% among infected ostriches. In contrast to HPAI (H5N1), which had already caused widespread disease in poultry and severe human infections primarily in South-East Asia, little data were available regarding the propensity for HPAI (H5N2) to cause human infection and disease. Prior to the recognition of the cause of the outbreak, farm workers and veterinary and agriculture personnel had extensive exposure to infected birds, with no personal protective equipment. The human health response to this outbreak was conducted in partnership with the provincial departments of health and the equivalent directorate of animal health within the provincial and national departments of agriculture, forestry and fisheries, and was aimed at limiting the potential spread of infection among exposed individuals and determining the risk, if any, of disease in humans from this subtype. The ORU responded by conducting field visits to affected ostrich farms to carry out a serological and clinical survey to establish evidence of transmission of the virus to humans. The key findings were

SARS, 2003

SARS was the first emerging pathogen of the 21st century, with global spread related to travel and high morbidity and mortality in affected persons.1,2 The identification of cases in travellers from South-East Asia, and secondary cases in countries around the world, required that a local outbreak response be initiated. While there were no definite confirmed cases within South Africa, more than 150 suspected cases were screened in accordance with a case definition. Laboratory testing for the putative coronavirus was established in the BSL-4 laboratory in the Special Pathogens Unit at NICDNational Health Laboratory Service (NHLS); all cases tested

South Afr J Epidemiol Infect

195

2011;26(4)(Part I)

Festschrift : Outbreaks in South Africa 2004-2011

that although severe disease in humans was not a problem, human infection was possible, as demonstrated by positive serology for HPAI (H5N2) in two highly exposed individuals who had titres of 1:80 and 1:640, respectively, and one who had evidence of seroconversion; the first evidence of HPAI (H5N2) transmission to humans in South Africa.4 This outbreak was the first time that the ORU had worked together with their counterparts in animal health, and formed the basis of a future close relationship for outbreaks in terms of early communications and outbreak alerts and a One Health approach to outbreak responses. With this outbreak, the unit demonstrated its capacity to link field-based investigations with the specialised laboratory capacities of the NICD-NHLS.

fevers (VHFs) was negative despite this being the most likely diagnosis. The cluster of related cases within a healthcare setting and the key findings of thrombocytopenia and transaminaemia suggested a VHF, despite bleeding not being prominent. Tracing and monitoring of all contacts of known patients for 21 days from last date of contact failed to identify additional cases. A novel and highly pathogenic Arenavirus, the first to be identified in Africa in four decades, was identified through the collaborative efforts of the Special Pathogens Unit of the NICD-NHLS and international scientific partners. It was proposed that the virus be named Lujo, in acknowledgement of association of Lusaka and Johannesburg with its emergence. Occurrence of the outbreak serves as a warning that pathogenic Arenaviruses could be more widely prevalent in Africa than is presently known. The event reinforces the need for strict screening of internationally transferred patients and for maintenance of appropriate infection control precautions at all times. This outbreak again highlighted the importance of a close relationship between the ORU and specialised NICDNHLS laboratories and internal and external stakeholders in responding to complex outbreaks. A model for communication between the NICD-NHLS and health professionals in South Africa, the media and international public health agencies was also established.6

Rabies, 2005

In November 2005, the ORU received reports of fatal encephalitis among children in the Limpopo province. Although these cases followed several months after a major increase in dog rabies was identified, there was no consideration of rabies as the cause, because of low clinical suspicion, the occurrence of atypical clinical presentations and limited clinician experience of rabies. Once rabies was confirmed in an index case, investigations identified 21 confirmed, four probable and five possible human cases between August 2005 and December 2006. The ORU played a critical role in raising the possibility of rabies as the aetiology in these cases, and then facilitating and providing laboratory confirmation. This led directly to the launch of an intensive rabies prevention programme in the province, which included a community awareness programme, healthcare worker training on postexposure prophylaxis (PEP), provision of rabies biologicals, the deployment of rabies vaccines to community clinics, and a major dog vaccination campaign. In the year following on the intensified programme (2006/7), only one human rabies case was identified, in a child with facial bites who developed rabies despite PEP.5

Cholera, 2008/9

In November 2008, a large outbreak of cholera was recognised in Zimbabwe, with subsequent cross-border spread to neighbouring Limpopo province. Further local transmission and contamination of water supplies led to a widespread outbreak affecting all nine provinces; Limpopo and Mpumalanga provinces were worst affected. The ORU maintained a database of all laboratory-confirmed cases notified from NHLS and private laboratories. For the period 15 November 2008 to 30 April 2009, over 12,000 suspected cases and 1,144 laboratory-confirmed cholera cases were reported, along with 57 deaths (case fatality rate of 0.5%). The ORU played an integral role in coordinating the laboratory testing and surveillance during this outbreak, as well as providing epidemiological support and technical assistance to health authorities in the provinces, important in guiding appropriate outbreak responses. Without systems in place for capturing timely and accurate data on clinical cases, this outbreak proved to be the first opportunity to demonstrate the ORUs expanding epidemiological capacities, and to utilise laboratory-based information systems to monitor the magnitude and extent of the outbreak in near-real time. This proved to be a valuable resource for the national and provincial levels of the Department of Health, and one that continues to be utilised to date.7

Lujo (Arenavirus), 2008

In September-October 2008, the ORU and the Special Pathogens Unit (SPU) at the NICD-NHLS partnered with South African health departments and international agencies in the investigation, diagnosis and control of a nosocomial outbreak of infection with a novel Arenavirus affecting five patients, four of whom died. The index case was transferred from Lusaka, Zambia to Johannesburg, South Africa for medical management of an acute progressive febrile illness characterised by encephalopathy, maculopapular rash and marked hepatic dysfunction and thrombocytopenia, but without significant bleeding. There were subsequently three secondary cases and one tertiary case with similar clinicopathology. The source of infection of the index case remains undetermined, but subsequent cases could be linked through likely exposure to blood or tissue fluids during medical evacuation or within the hospital setting. Extensive laboratory testing for the expected range of African viral haemorrhage

Pandemic influenza A(H1N1), 2009

Following the initial reports of human infection with a novel

South Afr J Epidemiol Infect

196

2011;26(4)(Part I)

Festschrift : Outbreaks in South Africa 2004-2011

influenza strain [pandemic influenza A(H1N1) 2009 virus] in the United States and Mexico during April 2009, rapid global transmission was observed. This prompted the WHO to raise the pandemic alert level to the highest phase (6) on 11 June. The ORU formulated guidelines for investigation and clinical management of the pandemic influenza, which were updated as necessary. The Revised Health Workers Handbook on Pandemic Influenza (H1N1) 2009 was endorsed by the national Department of Health and widely distributed to healthcare workers countrywide. The NICD-NHLS took a lead role in laboratory diagnostics, monitoring the extent of disease, and advising on clinical and public health response in South Africa. The ORU initiated surveillance to capture all laboratory-confirmed cases diagnosed by public and private sector laboratories throughout the country, a system that was critical in developing representative laboratory information for communicable disease that has proved invaluable in subsequent outbreaks. Data generated by this collaborative surveillance effort were utilised to provide regular situation reports to inform key stakeholders and international partners about the South African situation and to guide responses. Additionally, the unit conducted investigations into the first 100 laboratory-confirmed cases, as well as all reported fatal cases. As at 15 February 2010, 12,640 cases and 93 deaths had been confirmed in South Africa. Analysis of the fatal cases produced one of the first reports of a possible risk associated with HIV infection (48% of 40 tested), pregnancy (29%), and tuberculosis (10%) in South Africa. These suggested risk factors had particular bearing on influenza vaccination policies in the South African setting.8,9

Conclusions

These outbreaks highlight the role of a specialised and dedicated ORU within the NICD-NHLS, and many of the valuable initiatives and tools developed with subsequent outbreak experience. The role of the laboratory in confirming and guiding outbreak responses and the value of the close working relationship and complementary roles between ORU and the NICD, the NHLS and private and international laboratories deserve special mention. A One Health collaborative has strengthened early responses and improved use of combined resources to manage zoonotic outbreaks. Epidemiological components have added immeasurably to the laboratorybased focus within the NICD-NHLS. Most importantly, the ORU has served well as a technical resource for responses to outbreaks within South Africa and the region.15 Disease outbreaks are acute and can be sensational and fear-provoking, capture media headlines and consume vast resources. Outbreaks test the capacity of many institutions and health providers. We pay tribute to Prof Barry Schoub, as an inspired and visionary leader in creating the ORU and for providing an enabling work environment for the challenges to be met.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the many persons who have been involved in responding to these outbreaks. These include those from partner institutions, reference units and laboratories, both within the NICD-NHLS and private sector, communicable diseases control personnel within local authorities and provincial and national departments of health in South Africa, and the departments of agriculture, forestry and fisheries. A special acknowledgement must go to Profs Robert Swanepoel and Janusz Paweska and all the staff of the Special Pathogens Unit of the NICD-NHLS.

Rift Valley fever, 2008-2011

South Africa experienced its first large epizootic of Rift Valley fever (RVF) in 1950-1951, followed by another in 1974-1976 in which fatal human disease was first reported.10.11 Sporadic, localised outbreaks of RVF in animals occurred in 2008 and 2009, followed by an extensive and geographically widespread outbreak in 2010. There were 25 laboratory-confirmed human cases in 2008 and 2009. All cases were farm workers or veterinarians and reported direct contact with animal tissue. During 2010, a total of 242 laboratory-confirmed human RVF cases with 26 deaths was identified. The ORU worked in close collaboration with the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries and Department of Health throughout the outbreak. The unit developed the Health Workers Guidelines on Rift Valley Fever, collected data on laboratory-confirmed cases, provided regular situation reports to all stakeholders, and participated in training around the country. Control measures focused on health promotion to limit unprotected contact with infected animal tissue; however, ongoing cases continued to occur on farms, because of challenges in compliance with preventive measures.12-14

References

1. Peiris JSM, Yuen KY, Osterhaus ADME, Sthr K. The severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 2431-2441 2. Ksiazek TG, Erdman D, Goldsmith CS, et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 1953-1966 3. NICD, Communicable Diseases Communiqu, May 2003; 2(4) 4. De Jong G, Besselaar T, Paweska J, Schoub B, Blumberg L. Outbreak of avian influenza H5N2 in ostriches in South Africa in 2004: Human health response. Proceedings of the First African Influenza Symposium, Johannesburg, December 2009 5. Cohen C, Sartorius B, Sabeta C, et al. Epidemiology and molecular virus characterization of re-emerging rabies, South Africa. EID 2007; 13(12): 1879-1886 6. Paweska JT, Sewlall NH, Ksiazek TG, et al., and members of the Outbreak Control and Investigation teams. Nosocomial outbreak of novel arenavirus infection, southern Africa. Emerg Infect Dis 2009; 15: 1498-1602 7. Archer BN, Cengimbo A, De Jong GM, Cholera outbreak in South Africa: descriptive epidemiology of laboratory-confirmed cases, 15 November 2008 to 30 April 2009 (abstract).FIDSSA Conference, 2009. South Afr J Epid Infect 2009; 24(3): 44-45 8. Archer BN, Cohen C, Naidoo D, et al. Interim report on pandemic H1N1 influenza virus infections in South Africa, April to October 2009: Epidemiology and factors associated with fatal cases. Euro Surveill 2009; 14(42): 1-5 9. Archer BN, Timothy GA, Cohen C, et al. Introduction of 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) into South Africa: Clinical presentation, epidemiology and transmissibility of the first 100 cases. J Infect Dis Supplement: Influenza in Africa. (In press) 10. McIntosh BM, Russell D, Dos Santos I, Gear JHS. Rift valley fever in humans in South Africa. S Afr Med J 1980; 58: 803-806 11. Van Velden DJJ, Meyer JD, Olivier J, Gear JHS, McIntosh BM. Rift Valley fever affecting humans in South Africa, a clinicopathological study. S Afr Med J 1977; 51: 867 12. Preliminary report on an outbreak of Rift Valley fever, South Africa, February to 3 May 2010. NICD, Communicable Diseases Communiqu, May 2010; 9(5); additional issue (1) 13. Archer BN, Weyer J, Paweska J, et al. Outbreak of Rift Valley fever affecting veterinarians and farmers in South Africa, 2008. S Afr Med J 2011; 101(4): 263-266 14. Blumberg L. Rift Valley fever outbreaks, South Africa 2008-2011: Human health aspects. Proceedings of the One Health Conference, Melbourne, 2011 15. Blumberg L. New culprits and old threats in infectious diseases: the work of disease detectives. AJ Orenstein Memorial lecture, Johannesburg 2009

South Afr J Epidemiol Infect

197

2011;26(4)(Part I)

Você também pode gostar

- A Review On Nanomaterials For Environmental RemediationDocumento35 páginasA Review On Nanomaterials For Environmental RemediationNeo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- Youth Volunteering in Africa The Case of The Au Youth Volunteers CorpsDocumento12 páginasYouth Volunteering in Africa The Case of The Au Youth Volunteers CorpsNeo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- Botha 2 Comparative Aquatic Toxicity of - Gold NanoparticlesDocumento8 páginasBotha 2 Comparative Aquatic Toxicity of - Gold NanoparticlesNeo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- SKEPP 2011 Nanomaterials - in - REACH - Report - 15082011 PDFDocumento239 páginasSKEPP 2011 Nanomaterials - in - REACH - Report - 15082011 PDFNeo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- Gulumian SAJS 2012Documento9 páginasGulumian SAJS 2012Neo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- Ce Foundtn Manual Edited PDFDocumento30 páginasCe Foundtn Manual Edited PDFNeo Mervyn Monaheng67% (6)

- Chap2 Power Point PresentationDocumento74 páginasChap2 Power Point PresentationNeo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- DR McCormick Academic Essay Notes February 2017Documento9 páginasDR McCormick Academic Essay Notes February 2017Neo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- The Blood Covenant: by Mindena SpurlingDocumento33 páginasThe Blood Covenant: by Mindena SpurlingNeo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- Mathematics 1 Tutorials 2017Documento66 páginasMathematics 1 Tutorials 2017Neo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- Practical Manual Converted Final 2017Documento43 páginasPractical Manual Converted Final 2017Neo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocumento15 páginas6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Caps Fet - Life Sciences - GR 10-12 Web - 2636Documento82 páginasCaps Fet - Life Sciences - GR 10-12 Web - 2636Neo Mervyn Monaheng50% (2)

- Joint and by Products 2016Documento20 páginasJoint and by Products 2016Neo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- 2 CytoUserGuide 6.0Documento134 páginas2 CytoUserGuide 6.0Neo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- Class 6 Handout 3 Poster GM CropsDocumento1 páginaClass 6 Handout 3 Poster GM CropsNeo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- Bachelor of CommerceDocumento1 páginaBachelor of CommerceNeo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- The Citizen - Laboratory Scientist Degree Created - 25 OctoberDocumento1 páginaThe Citizen - Laboratory Scientist Degree Created - 25 OctoberNeo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- Acute Promylocytic LeukaemiaDocumento2 páginasAcute Promylocytic LeukaemiaNeo Mervyn Monaheng100% (1)

- Class 1 Handout 2 Topics in Nanobt Poster Biotech TimelineDocumento1 páginaClass 1 Handout 2 Topics in Nanobt Poster Biotech TimelineNeo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- Density Functional TheoryDocumento3 páginasDensity Functional TheoryNeo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- Dr. Johnson Segment 2 Lecture NotesDocumento3 páginasDr. Johnson Segment 2 Lecture NotesNeo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- 9LHDocumento1 página9LHNeo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- Class 1 Handout 3 Topics in Nanobtposter Traditional BiotechDocumento1 páginaClass 1 Handout 3 Topics in Nanobtposter Traditional BiotechNeo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- Developmental Delay (DD) or Intellectual Disability (ID) Testing AlgorithmDocumento1 páginaDevelopmental Delay (DD) or Intellectual Disability (ID) Testing AlgorithmNeo Mervyn Monaheng100% (1)

- (Nicodemus Visits Jesus) : Presented by Sermons 4 Kids Featuring The Art of Henry MartinDocumento10 páginas(Nicodemus Visits Jesus) : Presented by Sermons 4 Kids Featuring The Art of Henry MartinNeo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- CBL ExhibitDocumento1 páginaCBL ExhibitNeo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- Workflow 2Documento3 páginasWorkflow 2Neo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- Ye Are GodsDocumento2 páginasYe Are GodsNeo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- MSC in Clinical Epidemiology Course Outline 2015Documento24 páginasMSC in Clinical Epidemiology Course Outline 2015Neo Mervyn MonahengAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (120)

- Back WagesDocumento24 páginasBack WagesfaisalfarizAinda não há avaliações

- Security Gap Analysis Template: in Place? RatingDocumento6 páginasSecurity Gap Analysis Template: in Place? RatingVIbhishan0% (1)

- Tropical Design Reviewer (With Answers)Documento2 páginasTropical Design Reviewer (With Answers)Sheena Lou Sangalang100% (4)

- Bekic (Ed) - Submerged Heritage 6 Web Final PDFDocumento76 páginasBekic (Ed) - Submerged Heritage 6 Web Final PDFutvrdaAinda não há avaliações

- Makalah Soal Soal UtbkDocumento15 páginasMakalah Soal Soal UtbkAndidwiyuniarti100% (1)

- Due Books List ECEDocumento3 páginasDue Books List ECEMadhumithaAinda não há avaliações

- How To Play Casino - Card Game RulesDocumento1 páginaHow To Play Casino - Card Game RulesNouka VEAinda não há avaliações

- Financial Accounting Theory Craig Deegan Chapter 7Documento9 páginasFinancial Accounting Theory Craig Deegan Chapter 7Sylvia Al-a'maAinda não há avaliações

- MF 2 Capital Budgeting DecisionsDocumento71 páginasMF 2 Capital Budgeting Decisionsarun yadavAinda não há avaliações

- TAX Report WireframeDocumento13 páginasTAX Report WireframeHare KrishnaAinda não há avaliações

- Official Memo: From: To: CCDocumento4 páginasOfficial Memo: From: To: CCrobiAinda não há avaliações

- Jeoparty Fraud Week 2022 EditableDocumento65 páginasJeoparty Fraud Week 2022 EditableRhea SimoneAinda não há avaliações

- Posterior Cranial Fossa Anesthetic ManagementDocumento48 páginasPosterior Cranial Fossa Anesthetic ManagementDivya Rekha KolliAinda não há avaliações

- 1219201571137027Documento5 páginas1219201571137027Nishant SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Snap Fasteners For Clothes-Snap Fasteners For Clothes Manufacturers, Suppliers and Exporters On Alibaba - ComapparelDocumento7 páginasSnap Fasteners For Clothes-Snap Fasteners For Clothes Manufacturers, Suppliers and Exporters On Alibaba - ComapparelLucky ParasharAinda não há avaliações

- 5010XXXXXX9947 04483b98 05may2019 TO 04jun2019 054108434Documento1 página5010XXXXXX9947 04483b98 05may2019 TO 04jun2019 054108434srithika reddy seelamAinda não há avaliações

- Feasibility Study For A Sustainability Based Clothing Start-UpDocumento49 páginasFeasibility Study For A Sustainability Based Clothing Start-UpUtso DasAinda não há avaliações

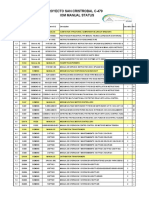

- Proyecto San Cristrobal C-479 Iom Manual StatusDocumento18 páginasProyecto San Cristrobal C-479 Iom Manual StatusAllen Marcelo Ballesteros LópezAinda não há avaliações

- How A Type 4 Multiverse WorksDocumento4 páginasHow A Type 4 Multiverse WorksIdkAinda não há avaliações

- Diffusion Osmosis Enzymes Maths and Write Up Exam QuestionsDocumento9 páginasDiffusion Osmosis Enzymes Maths and Write Up Exam QuestionsArooj AbidAinda não há avaliações

- Burton 1998 Eco Neighbourhoods A Review of ProjectsDocumento20 páginasBurton 1998 Eco Neighbourhoods A Review of ProjectsAthenaMorAinda não há avaliações

- British Council IELTS Online Application SummaryDocumento3 páginasBritish Council IELTS Online Application Summarys_asadeAinda não há avaliações

- The Syllable: The Pulse' or Motor' Theory of Syllable Production Proposed by The Psychologist RDocumento6 páginasThe Syllable: The Pulse' or Motor' Theory of Syllable Production Proposed by The Psychologist RBianca Ciutea100% (1)

- Pr1 m4 Identifying The Inquiry and Stating The ProblemDocumento61 páginasPr1 m4 Identifying The Inquiry and Stating The ProblemaachecheutautautaAinda não há avaliações

- FCI - GST - Manual On Returns and PaymentsDocumento30 páginasFCI - GST - Manual On Returns and PaymentsAmber ChaturvediAinda não há avaliações

- Order of Nine Angles: RealityDocumento20 páginasOrder of Nine Angles: RealityBrett StevensAinda não há avaliações

- NR Serial Surname Given Name Middlename: Republic of The Philippines National Police CommissionDocumento49 páginasNR Serial Surname Given Name Middlename: Republic of The Philippines National Police CommissionKent GallardoAinda não há avaliações

- FINN 400-Applied Corporate Finance-Atif Saeed Chaudhry-Fazal Jawad SeyyedDocumento7 páginasFINN 400-Applied Corporate Finance-Atif Saeed Chaudhry-Fazal Jawad SeyyedYou VeeAinda não há avaliações

- Lae 3333 2 Week Lesson PlanDocumento37 páginasLae 3333 2 Week Lesson Planapi-242598382Ainda não há avaliações

- HSG 9 Tienganh 2019Documento7 páginasHSG 9 Tienganh 2019Bảo HoàngAinda não há avaliações