Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

CALI Cash Flow Update 050709

Enviado por

CreditTraderDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

CALI Cash Flow Update 050709

Enviado por

CreditTraderDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

California’s Cash Flow

Crisis: May 2009 Update

MAC TAY LO R • L E G I S L A T I V E A N A L Y S T • MAY 7, 2009

AN LAO REPORT

2 LEGISLATIVE ANALYST’S OFFICE

AN LAO REPORT

SUMMARY

Much Progress Was Made in February... The February budget package addressed a

$40 billion shortfall in California’s finances, thereby helping the state’s dire cash flow situation.

The package also delayed or deferred numerous state payments and allowed over $2 billion of

state special funds to be borrowed by the General Fund on a temporary basis for cash flow pur-

poses. These actions allowed the Controller to end a one-month halt on tax refunds, payments

to local governments, and other payments. The Controller has stated that the state will be able

to pay its bills “in full and on time” through the rest of the 2008‑09 fiscal year. In addition,

passage of the February package led the Treasurer to resume sales of long-term infrastructure

bonds, and recently, this allowed the state to resume funding for thousands of infrastructure

projects that had been halted due to the cash crisis in late 2008.

…But Cash Flow Pressures Are Likely to Reemerge in Summer and Fall 2009. While the

February budget package eased the state’s cash flow crunch considerably, the budget and cash

pressures of recent months have taken their toll. The General Fund’s “cash cushion”—the mon-

ies available to pay state bills at any given time—currently is projected to end 2008‑09 at a

much lower level than normal. Without additional legislative measures to address the state’s fis-

cal difficulties or unprecedented amounts of borrowing from the short-term credit markets, the

state will not be able to pay many of its bills on time for much of its 2009‑10 fiscal year. Dete-

rioration of the state’s economic and revenue picture (such as the $8 billion revenue shortfall

we forecasted in March) or failure of measures in the May 19 special election would increase

the state’s cash flow pressures substantially—potentially increasing the short-term borrowing

requirement to well over $20 billion. California is likely to have difficulty borrowing anywhere

close to the needed amounts from the short-term bond markets based on the state govern-

ment’s own credit.

Prompt Legislative Action Required. Time is of the essence in addressing California’s cash

flow challenges. In our opinion, the greatest near-term threat to state cash flows would be an

inability by state leaders to quickly address California’s budget imbalance. If there were to be

a prolonged impasse, the Treasurer and Controller could be prevented from borrowing suf-

ficient funds to allow the state to pay its bills on time. In such a scenario, the Controller would

have much less flexibility than he did in February (during personal income tax refund season)

to delay non-priority state payments. An inability to borrow sufficient funds by the Controller

and Treasurer could subject many more Californians—including local governments, vendors,

and, perhaps, in some dire scenarios, state employees and many others awaiting payments from

the state—to prolonged payment delays. Payment delays could affect many major state funds

during a prolonged impasse, including the General Fund and special funds, all of which are

funded from liquid resources in the state investment pool. Such payment delays could subject

the already fragile state budget to even more costs (such as penalties and interest).

LEGISLATIVE ANALYST’S OFFICE 3

AN LAO REPORT

The Legislature’s Options to Address the Situation. We advise the Legislature to reduce the

state’s short-term borrowing need to an amount under $10 billion for 2009‑10. (Regular updates

from the administration on the projected cash flow situation, therefore, will be necessary during

the upcoming budget deliberations.) To reduce the borrowing need and limit the state’s interest

costs in 2009‑10, the Legislature has two very difficult options:

➢ Additional actions to increase revenues or decrease expenditures in order to return the

2009‑10 budget to balance.

➢ Additional actions to delay or defer scheduled payments to schools, local governments,

service providers, and others.

Federal Assistance Could Come With “Strings Attached.” We believe it is appropriate for

the Treasurer to explore the possibility of federal assistance—such as a federal loan guaran-

tee—to address this summer and fall’s grim cash outlook. We caution the Legislature, however,

against assuming such federal assistance will be available. By taking prompt actions to reduce

the state’s cash flow borrowing need to under $10 billion for 2009‑10, policymakers would

enhance the ability of the Treasurer and Controller to secure private investment with or without

a federal loan guarantee. Moreover, reducing the state’s cash flow borrowing will involve ac-

tions that improve the state’s medium- and long-term budgetary outlook. These actions would

increase confidence in the bond markets, which are needed to continue providing funds for

infrastructure projects that spur economic activity and long-term growth. Finally, and perhaps

most importantly, we advise the Legislature and other state policymakers to be cautious about

accepting any strings that might be attached to federal assistance. Strings attached to recent

corporate bailouts—as well as federal loan guarantees provided to New York City during its

fiscal crisis three decades ago—have included measures to remove financial and operational

autonomy from executives. We recommend that the Legislature agree to no substantial dimin-

ishment in the role of California’s elected state leaders. In our opinion, the difficult decisions

to balance the state’s budget now are preferable to Californians losing some control over the

state’s finances and priorities to federal officials for years to come.

4 LEGISLATIVE ANALYST’S OFFICE

AN LAO REPORT

INTRODUCTION

In January 2009, we published California’s ➢ California’s cash flow outlook.

Cash Flow Crisis, one of the reports in our

2009‑10 Budget Analysis Series. This report ➢ The Legislature’s options to improve the

provides an update on matters discussed in the cash flow outlook.

January piece. Specifically, this report includes

➢ The possibility of federal assistance for

the following sections:

the state’s cash flow challenges.

➢ A history of the state’s recent cash flow

problems.

HISTORY OF THE STATE’S RECENT

CASH FLOW PROBLEMS

State Must Borrow for Cash Flow Purposes year and monthly cash flow surpluses through

Every Year. In California’s Cash Flow Crisis, much of the second half. To address this regular

we discussed the basic dynamics of the state’s imbalance of receipts and disbursements, the

General Fund cash flows. Specifically, the report state must borrow for cash flow purposes each

described how the state

generally disburses the

Figure 1

majority of General

Fund dollars in the first

Cash Flow Deficits Mark the First Half

Of the General Fund’s Fiscal Year

half of the fiscal year

(that is, between July 2007-08 (In Billions)

and December), while it $18

collects the majority of Receipts

16

Disbursements

General Fund receipts

14 Cash Deficit

in the second half of

Cash Surplus

the fiscal year (between 12

January and June). 10

As shown in Figure 1

8

(which uses 2007‑08

monthly cash flows as 6

a typical example), this 4

means that the state rou-

2

tinely runs monthly cash

flow deficits through

the first half of the fiscal Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun

LEGISLATIVE ANALYST’S OFFICE 5

AN LAO REPORT

year: first, from internally borrowable resources see our 2009‑10 Budget Analysis Series report

(principally, several hundred “special funds” in entitled The Fiscal Outlook Under the February

the state treasury) and second, from external Budget Package.) By their nature, revenue in-

private investors. creases, spending cuts, and other budget-balanc-

“Double Whammy” of Weak Revenues and ing actions help the state’s cash situation by put-

Credit Crisis Hurt State’s Cash Position. As we ting or leaving more money in the state’s coffers.

described in our January 2009 report, weakening In addition to these budgetary actions, the Leg-

state revenues and limited access to the credit islature approved a bill—Chapter 9, Statutes of

markets in the first half of 2008‑09 reduced the 2009‑10 Third Extraordinary Session (AB 13xxx,

state’s resources to address cash flow deficits. At Evans)—to make additional, substantial changes

the end of 2008, state officials halted funding for to the state’s cash management practices. This

thousands of infrastructure projects in order to bill was in addition to similar cash management

conserve state cash resources. Projections at the legislation passed as part of the original 2008‑09

time indicated that, absent action by the Legisla- budget package in September 2008.

ture or the Controller to conserve cash, available The cash management actions enacted by

resources to fund normal state operations—also the Legislature have played a key role in help-

known as the state’s cash cushion—would be ex- ing the state meet its priority payments on time

hausted by the end of February 2009. (The Con- through 2008‑09. In total, since the beginning of

troller typically aims to have a minimum $2.5 bil- the fiscal year, the Legislature has added funds

lion cash cushion in state accounts at any given with over $6 billion of balances to the list of state

time.) At the beginning of February 2009, the accounts able to be borrowed by the General

Controller used his authority to begin delaying Fund temporarily for cash flow purposes. The

certain state payments deemed to be of a lower Legislature also has deferred several billion dol-

priority under state law, including many vendor lars of payments to later in the 2008‑09 and

payments, payments to local governments, and 2009‑10 fiscal years. In addition, through its en-

tax refunds to individuals and corporations. By actment of legislation in March 2009, the Legis-

delaying about $3 billion of payments in Febru- lature allowed the state to take immediate receipt

ary, the Controller was able to conserve the cash of $1.5 billion of federal stimulus funds for Medi-

cushion to make other “priority payments” of the Cal, which directly benefits the General Fund.

state (such as payments for schools, debt service, In May 2009, the state will draw down nearly

and state payroll) on time. $800 million of federal stimulus funds available

Legislative Actions Have Eased Cash Crunch to cover costs of the state prison system on an

During Second Half of 2008‑09. The budget expedited basis, thereby reducing General Fund

package approved by the Legislature on February expenditures. Enactment of the February budget

19 and signed by the Governor on February 20 package also helped the Treasurer to execute

addresses a $40 billion budget shortfall with a an additional $500 million cash flow borrow-

combination of temporary tax increases, spend- ing with The Golden 1 Credit Union and restart

ing cuts, borrowing, and federal stimulus funds. long-term infrastructure bond sales. Two huge

(For more information on the budget package, and extraordinarily successful long-term bond

6 LEGISLATIVE ANALYST’S OFFICE

AN LAO REPORT

sales in March 2009 Figure 2

and April 2009 raised

Controller: February Budget Package Eased

over $13 billion for state

2008-09 Cash Crunch

projects and allowed

Estimated State “Cash Cushion” (In Billions)a

the administration to

$6

end the state project

“funding freeze” that

4

had been instituted in Estimates as of March 31

late 2008 due to the 2

cash crisis.

Controller Was 0

Able to End Previ‑

ously Instituted Delay -2

of Certain State Pay‑ Estimates Before February Budget Package

ments. Due to all of the -4

cash flow and budget-

-6

ary changes described April May June

above, the Controller aEstimates are for the lowest amount of cash cushion available to pay state bills on any day during the

was able to end the months listed.

delay of non-priority

state payments. On the February budget package and on March 31,

March 31, 2009, the Controller stated that the when he was able to make this statement. The

state government had sufficient cash resources to dramatically improved March 31 figures reflect

“meet all of our obligations in full and on time” (1) enactment of the February budget package,

through the rest of 2008‑09. Figure 2 shows the (2) completion of the $500 million short-term

Controller’s estimates of the state’s cash cush- Golden 1 cash flow borrowing, and (3) the accel-

ion in late 2008‑09 both before enactment of erated receipt of Medi-Cal stimulus funds.

CALIFORNIA’S CASH FLOW OUTLOOK

Administration Projections Indicate a New lion of extra disbursements in the forecast for

Cash Crisis May Lie Ahead. In early March 2009, “unanticipated cash risks” through the end of

the Department of Finance (DOF) prepared an 2008‑09, DOF indicated that the budget pack-

estimate of how the various measures associated age had practically eliminated the cash crunch in

with the package (including the tax increases, the current fiscal year. The DOF forecast, how-

spending reductions, payment deferrals, and ever, indicated the possibility of severe cash flow

newly authorized borrowable funds) affected pressures reemerging as soon as July 2009 and

the state’s cash flow outlook through the end persisting through much of 2009‑10.

of 2009‑10. Even after including about $1 bil-

LEGISLATIVE ANALYST’S OFFICE 7

AN LAO REPORT

Severely Weakened Cash Cushion at the taken various budgetary and cash management

End of 2008‑09 Is Expected to be a Key Prob‑ actions such as these, the state’s cash cushion

lem. The key problem identified in the DOF would have been zero at the end of 2008‑09.

forecast is the likelihood of a severely weak- Potentially Unprecedented Short-Term

ened state cash cushion at the conclusion of the Borrowing May Be Required in 2009‑10. A

2008‑09 fiscal year. While the budget package weakened cash cushion on June 30 is a problem

allows the state, in the Controller’s view, to meet because of the basic dynamics of the state’s Gen-

its budgeted obligations on time through the rest eral Fund cash flows displayed earlier in Figure 1.

of 2008‑09, the DOF forecast shows that the state The state disburses the bulk of its General Fund

cash cushion would be $6.9 billion on June 30. expenditures during the first half of the fiscal

This is much less than the state typically has in its year, but collects most of its receipts later. This

cash cushion at the end of a fiscal year—indica- means that several months at the beginning of

tive of the fact that the state will most certainly the fiscal year have monthly cash flow deficits—

end the 2008‑09 fiscal year with a budgetary that is, months when monthly General Fund

deficit. (The February budget plan anticipated receipts are less than monthly General Fund

there being an operating surplus in 2009‑10 to disbursements. While the DOF’s March 2009

address the 2008‑09 budget deficit and build forecast projects a cash cushion of $6.9 billion

up a reserve account.) Figure 3 shows that the (consisting entirely of borrowable special fund

expected fiscal year-end cash cushion at June 30, balances—with no available General Fund bal-

2009, is roughly one-

half of the cash cushion Figure 3

the state had one year

2008-09 Year-End Cash Cushion to Be

before and only about

Much Lower Than in Prior Years

one-third of the amount

(In Billions)

of three years ago. To

$25

put these figures in per-

spective, note that the

year-end cash cushion 20

for 2008‑09 reflects

the Legislature’s actions 15

over the past year to

add several billion dol-

10

lars of funds to that cash

cushion in the form

5

of new special funds

eligible to be borrowed

by the General Fund

2005-06 2006-07 2007-08 2008-09a

for cash flow purposes.

aDepartment of Finance cash flow forecast as of March 2009. Based on assumptions in 2009-10 budget

Had the Legislature not package.

8 LEGISLATIVE ANALYST’S OFFICE

AN LAO REPORT

ance) as of June 30, 2009, the forecast indicates anticipation warrants (RAWs)—are described in

that the General Fund is expected to have a the nearby box.

monthly cash flow deficit of $7.9 billion in July A huge concern is that monthly cash flow

2009 alone. The estimated cash flow deficit in deficits of varying amounts are expected un-

that month is so great that DOF estimates the der the February budget package every month

cash cushion will be depleted under the Febru- between July 2009 and November 2009. These

ary budget package unless the Controller delays five consecutive months of monthly cash flow

state payments once again as he did in February deficits mean that, under the DOF forecast, the

or the state borrows funds from private investors. state would need to borrow amounts that could

The state borrows on a short-term basis from grow to well over $13 billion by about October—

the credit markets virtually every year by issuing probably through issuance of RANs or RAWs—

revenue anticipation notes (RANs). These notes, in order to pay all bills on time and maintain

along with a related borrowing source—revenue the state’s traditional minimum cash cushion

Revenue Anticipation Notes (RANs) and Revenue

Anticipation Warrants (RAWs)

RANs. The state’s most commonly used device for external cash flow borrowing is the

RAN—a low-cost, short-term financing tool. Typically issued early in the fiscal year, RANs must

be repaid prior to the end of the fiscal year of issuance (usually in April, May, or June). Unlike

most of the state’s long-term infrastructure bonds, RANs are not state general obligations. The

RANs are secured by money in the General Fund that is available after providing funds for the

state’s “priority payments,” such as payments to schools, general obligation debt service, and

state employee payroll, among other payments. The State Treasurer’s office works with financial

firms to issue RANs almost every year. The state has sold $5.5 billion of RANs to investors dur-

ing 2008‑09.

RAWs. The state has issued RAWs for cash flow relief occasionally since these securities

were created during the severe state budget crisis of the early 1930s. The main reason that the

state resorts to RAWs is that they can be repaid in a subsequent fiscal year after their issuance.

In fact, one California RAW issued in July 1994 matured 21 months later. The ability to have a

later maturity date means the state can borrow for cash flow purposes even if the state’s cash

outlook is challenging in the near term. Because of this longer maturity schedule and the fact

that RAWs typically are issued when the state faces challenging budget times, they generally are

more costly—with higher interest and other issuance costs—than RANs. The state’s $7 billion

of RAWs in 1994, for example, resulted in interest and other issuance costs of over $400 mil-

lion, and the $11 billion of RAWs in 2003 resulted in over $260 million of costs. The State

Controller’s office works with financial firms to issue RAWs.

LEGISLATIVE ANALYST’S OFFICE 9

AN LAO REPORT

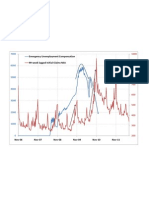

of $2.5 billion. Figure 4 summarizes DOF’s ported that, through the end of March, amounts

March 2009 cash flow forecast by showing in borrowable special funds were running about

the expected end-of-month state cash cushion $2 billion higher than forecast. (It is not known

throughout 2009‑10 before considering any bor- whether this will be a sustained trend.) In ad-

rowing from private investors. The forecast shows dition, as described earlier, about $800 million

the state’s accumulated cash deficit—illustrated of federal stimulus moneys for corrections was

in Figure 4 as the “negative cash cushion”— received earlier this month—over one year in

would reach $10 billion to $11 billion for much advance of its expected date of receipt based

of the middle part of 2009‑10. The state, there- on the DOF March forecast. (While legislative

fore, might need to borrow over $13 billion from action allowed the state to expedite receipt of

investors in order to pay all currently budgeted certain Medi-Cal funds from the federal gov-

bills on time and maintain the target minimum ernment, this already was factored in DOF’s

$2.5 billion cash cushion described above. 2009‑10 cash flow forecast.) On the other hand,

Some Negative Signs Have Emerged Since more than offsetting these positive develop-

the March Cash Forecast. Figure 5 lists several ments has been a variety of negative economic

developments for the state’s cash flow situation and state revenue data, which led our office to

that have emerged since DOF completed its fore- project in March 2009 that General Fund rev-

cast in March. Some of these developments have enues in 2009‑10 would be about $8 billion

been good news. For example, the Controller re- below those assumed in the February budget

package and DOF’s

Figure 4

March cash forecast.

(Because of the timing

March 2009 Forecast Projected Huge Deficit in the

of state receipts, a loss

State’s Cash Cushion Through Much of 2009-10a

of $8 billion in annual

(In Billions)

revenues does not nec-

$4

essarily mean the state

2 needs to borrow the

same $8 billion to keep

0

paying bills on time in

-2 each month.) Net state

receipts of personal

-4

income and corporate

-6 tax payments in April

-8 2009 also were weaker

than expected—adding

-10

to poor February and

-12 March revenue collec-

July September November January March May

tions. After considering

aThis figure shows the projected amounts in the state’s cash cushion on the last day of each month based on

the February budget package before consideration of any short-term borrowing from private investors. these developments and

10 LEGISLATIVE ANALYST’S OFFICE

AN LAO REPORT

assuming that higher amounts in borrowable ➢ First, this would be an unprecedented

special funds persist, we can make a rough esti- amount of short-term borrowing for the

mate that the state’s borrowing requirement from state. State short-term borrowing reached

private investors in 2009‑10 may be somewhere a peak of just under $14 billion—raised

around $17 billion—or $4 billion higher than through issuance of both RANs and

forecast by DOF in March. Further projected RAWs—during 2003‑04, but this oc-

revenue declines or expenditure increases could curred during a period of relatively easy

add to this borrowing need, including the voters’ credit availability. Then, liquidity in the

possible rejection of Propositions 1C, 1D, and 1E short-term credit markets was healthy

on the May 19 ballot. As shown in Figure 5, re- (unlike in recent months) and credit stan-

jection of these measures could cause the state’s dards of investors and banks were less

2009‑10 investor borrowing requirement to swell restrictive than they are now.

to around $23 billion.

Borrowing Well Over $13 Billion on the ➢ Second, the amount of borrowing as

State’s Own Credit May Not Be Possible. Of- a percentage of state receipts—over

ficials of the administration, the Treasurer’s office, 13 percent for a $13 billion short-term

and the Controller’s office meet regularly with borrowing—is at least double the maxi-

representatives of financial institutions and insti- mum typically recommended by mu-

tutional investors in the municipal credit markets. nicipal bond market credit experts. This

Despite the state’s recent means it is likely that RAWs or RANs

successes issuing bonds

in the long-term credit Figure 5

markets, the major finan- State’s 2009-10 Short-Term Borrowing Need

cial institutions reported- (In Billions)

ly have indicated to state

Administration's March Cash Forecast $13

officials that California

will have difficulty bor- Known developments since March cash forecast

Higher amounts in borrowable special funds (as of March 31) -$2

rowing $13 billion from Expedited receipt of federal stimulus funds for corrections -1

the short-term markets Lower revenue receipts from February to April 2009 3

Possible need based on LAO's forecast of lower 2009-10 revenues a 4

based on its own credit

Subtotal ($4)

in 2009‑10—let alone

Rough Estimate Based on Known Developments Since March $17

the much larger amount

of around $23 billion dis- Effect if Propositions 1C, 1D, and 1E Are Rejected by Voters $6

cussed in Figure 5. There Rough Estimate if Proposition are Rejected by Voters $23

a In a March 2009 report we forecast that General Fund revenues would be $8 billion below the

are various reasons why

February budget package forecast in 2009-10. Because some of this difference affects state receipts

the state may have dif- in April through June 2010, when state cash flows are relatively strong, this difference would not likely

result in an $8 billion increase in the state's needed borrowing from short-term investors. Instead, the

ficulty borrowing such decrease in revenues should result in a smaller increase in the state's borrowing need. We show

$4 billion here as a very rough estimate.

large amounts:

LEGISLATIVE ANALYST’S OFFICE 11

AN LAO REPORT

totaling over $13 billion would have a such as money market funds—have

poor credit rating. With weakened banks stricter credit standards than ever before,

and other financial institutions limited in and they may be reluctant to purchase

their ability to offer credit enhancement RANs or RAWs with a low rating. Even

(essentially, a type of bond insurance) to if investors did purchase the securities,

the state’s RAWs or RANs, a low rating state interest costs for borrowing may

will mean that major segments of the exceed budgeted amounts—potentially

short-term investor market will be unable by as much as hundreds of millions of

or unwilling to participate in the state’s dollars—as the administration warned

2009‑10 cash flow borrowing. With fresh the Legislature in a budget letter submit-

memories of their own liquidity crisis last ted in early April 2009.

year, major short-term market investors—

RECOMMENDATIONS AND OPTIONS

FOR THE LEGISLATURE

In this section, we address ways that the we recommend that the Legislature focus in the

Legislature can address the state’s cash flow coming weeks on a goal of reducing the state’s

crisis. First, we discuss broad goals concerning cash flow borrowing need for 2009‑10 to some-

state cash flows for the Legislature to consider in where below $10 billion. In any scenario, this

its upcoming budget deliberations. Second, we will make it easier for state officials to execute the

discuss specific options that the Legislature may state’s cash flow borrowing. To accomplish this

need to consider to achieve these goals. Third, goal, the Legislature will need to ask the admin-

we discuss the important issue of timing: when istration for regular updates on projected cash

the Legislature needs to take action to provide flows during its upcoming budget deliberations.

the greatest possible assurance that the state can Reducing Short-Term Borrowing Need Be‑

continue paying its bills on time. low $10 Billion Means More Difficult Choices.

Just as the Legislature faced difficult choices earli-

Broad Goals for the Legislature er in 2008‑09 to balance the budget and address

Concerning State Cash Flows the cash flow crisis, even more difficult choices

Recommended Legislative Goal: Reducing remain for returning the budget to balance and

State’s Need for Short-Term Borrowing. While reducing the 2009‑10 cash flow borrowing need

the state’s recent success in selling long-term below $10 billion. The options for the Legislature

infrastructure bonds and resuming funding of to accomplish this fit into two general categories:

voter-approved projects is a positive sign, we are ➢ Budgetary actions to increase revenues

concerned about the potential difficulty and high or decrease expenditures of the General

costs involved in borrowing $13 billion or more Fund or other state funds available for

for cash flow needs in 2009‑10. Accordingly, cash flow borrowing.

12 LEGISLATIVE ANALYST’S OFFICE

AN LAO REPORT

➢ Cash flow actions to delay budgeted mental entities cope with additional payment

state payments or accelerate receipt of delays.

revenues from either the General Fund or Accelerating Issuance of Lottery Securitiza‑

borrowable special funds. tion Bonds May Prove Beneficial. The DOF cash

projections assume that the state receives $5 bil-

Returning the Budget to Balance Would

lion of lottery securitization proceeds—con-

Help the Cash Flow Situation. By their nature,

tingent upon voter approval of Proposition 1C

actions to increase state revenues or decrease

in May 2009—in March 2010. To ease the fall

expenditures help the cash flow situation, there-

2009 cash crunch somewhat, we recommend

by reducing the required borrowing from short-

that the Legislature encourage the administra-

term credit markets. Accordingly, we recommend

tion, which would control the lottery borrowing

that the Legislature focus first on addressing the

process under Proposition 1C, to pursue issuing

budget deficit. However, because budgetary

some or all of the lottery securitization bonds by

balancing actions will not necessarily deliver

October 2009. The lottery borrowing—a long-

their full benefit in the opening months of the

term bond market offering—would reduce the

fiscal year—when the state’s cash flow problems

need for issuance of short-term state obligations

are the greatest—balancing the budget alone

by the Treasurer or Controller by perhaps a few

may not solve the state’s cash flow difficulties.

billion dollars in the fall. Reducing the size of

Additional actions to defer payments or acceler-

these short-term obligations would make it easier

ate state receipts during the fiscal year may be

for state officials to market securities to short-

necessary.

term investors.

Specific Options for the Legislature to “Trigger Legislation” May Be Required. In

Achieve These Goals our January report on the cash flow crisis, we

discussed the possibility that so-called trigger leg-

Beyond the very difficult choices for the

islation might be needed to facilitate the sale of

Legislature in returning the 2009‑10 state budget

RAWs by the Controller. In the past, trigger leg-

to balance, there are some particular options that

islation—such as Chapter 135, Statutes of 1994

lawmakers may need to consider to address the

(SB 1230, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Re-

state’s cash flow challenge.

view)—has helped the state sell short-term cash

Additional Payment Deferrals May Be Nec‑

flow instruments by providing greater assurances

essary. Because state payments to schools rep-

to potential investors. Chapter 135 required the

resent a large portion of General Fund disburse-

state to reduce most categories of expenditures

ments in cash flow deficit months like July and

at the time if cash flow projections showed that

October, additional measures to delay scheduled

timely payment of RAWs was threatened. Given

state payments to schools may be necessary. De-

the need to preserve the Legislature’s consti-

ferrals of scheduled payments for various other

tutional prerogatives over the state budget, we

programs also may be required. To the extent

would be reluctant to recommend passage of

that federal stimulus funds are available to school

trigger legislation that ceded to the Governor the

districts and other local governments by early in

ability to determine which revenues were in-

the 2009‑10 fiscal year, this may help govern-

LEGISLATIVE ANALYST’S OFFICE 13

AN LAO REPORT

creased or expenditures decreased to provide as- and address the state’s budgetary and cash flow

surances to investors of timely RAW repayment. difficulties, private investors may be unwilling

Instead, assuming such legislation proves neces- to lend the state such large sums. Therefore,

sary, we advise the Legislature—as it did in the legislative actions to return the budget to bal-

February budget package in constructing a rev- ance and address the state’s cash flow challenges

enue and expenditure trigger tied to the receipt may be required before the Treasurer and Con-

of federal stimulus moneys—to specify which troller can issue the required amount of RANs

expenditures would be decreased and revenues or RAWs. Accordingly, in our view, the most

increased in any RAW trigger legislation. significant near-term threat to the state’s cash

flows is a prolonged legislative impasse in ad-

Action by Late June or Early dressing California’s budget difficulties after the

July at the Latest Is Needed May Revision. The Controller and Treasurer will

Time Is of the Essence in Addressing Cash have the greatest ability to issue sufficient RANs

Flow Problems. Addressing the state’s cash flow and RAWs in a timely fashion if the Legislature

challenges is inherently a matter of timing. For restores the budget to balance and takes action

the state to have sufficient funds to make General to reduce the state’s short-term borrowing need

Fund and special fund payments on time, access by late June 2009 or early July 2009 at the latest.

to sufficient borrowed funds—from both internal By taking action on this timeline, the Legislature

sources and private investors—is needed by a would allow state officials to begin to access the

given date. The DOF projections under the terms short-term credit markets in early or mid-July. In

of the February budget package show that the any event, the earlier the Legislature takes action

state will need to begin borrowing from private after the special election to address the state’s

investors in the short-term credit markets in July. budget and cash problems, the less likely that

Under this package, a total of well over $13 bil- the Controller will have to resume delaying state

lion in private borrowing likely would need to payments in order to preserve cash for timely

be completed by October. As discussed earlier, disbursement of priority payments, such as pay-

the state may face a major new budgetary gap ments to schools and bondholders.

that will also worsen the state’s cash situation.

Absent legislative actions to rebalance the budget

THE POSSIBILITY OF FEDERAL ASSISTANCE

Treasurer Exploring Federal Assistance, cess the short-term debt markets. We believe that

Such as a Federal Guarantee for RANs or it is appropriate for the Treasurer to explore these

RAWs. Given the possible difficulty for the state options with federal officials. Among the options

marketing a vast amount of short-term notes or for possible federal assistance are:

warrants, the Treasurer’s office has indicated that ➢ A federal guarantee of the state’s short-

it is exploring potential federal assistance for the term cash flow borrowing.

state (and other public entities) that need to ac-

14 LEGISLATIVE ANALYST’S OFFICE

AN LAO REPORT

➢ A federal commitment to purchase the debt obligations would. Nevertheless, the fed-

state’s RANs or RAWs from investors eral government also could insist on a binding,

in certain circumstances, perhaps using multiyear budget balancing plan from the state

funds of the Troubled Assets Relief Pro- or the ability to assume some sort of operational

gram approved by Congress in 2008. control or oversight of state operations in certain

cases. For example, the New York City guarantee

➢ Accelerated receipt of federal stimulus act required the city to submit to the Secretary

moneys that offset state General Fund of the Treasury a plan for balancing its budget

expenditures, which could reduce the within roughly four years and mandated that

state’s need for cash flow borrowing in an independent fiscal monitor “demonstrate to

2009‑10. the satisfaction of the secretary that it has the

Recently, the U.S. government has assisted vari- authority to control the city’s fiscal affairs dur-

ous financial institutions and corporate entities ing the entire period in which federal guarantees

facing insolvency. In addition, there is precedent are outstanding.” The state-created fiscal control

for a federal guarantee of a public entity facing board that oversaw New York City’s finances

serious financial difficulties. In 1978, the Con- remains in existence to this day, although many

gress passed and President Carter signed the of its powers under state law have expired. In

New York City Loan Guarantee Act, a response short, the Legislature and policymakers should

to the city’s severe fiscal crisis at the time. A expect that there would be strings attached to

properly structured federal loan guarantee of federal assistance. While the severe nature of the

this type would allow the state relatively simple state’s cash flow problems necessitate consider‑

access to the bond markets. Such bond market ing an offer of federal aid, we recommend that

access would be based on the U.S. government’s the Legislature be very cautious about accepting

full faith and credit. A guarantee may require ap- federal aid with strings attached that undermine

proval by the Congress in a bill, which would be the ability of this Legislature or future Legislatures

subject to approval or veto by the President. to set the state’s fiscal and policy priorities. We

Recommend That Legislature and Policy‑ recommend that the Legislature agree to no sub-

makers Be Cautious About Strings Attached to stantial diminishment of the role of California’s

Federal Assistance. Given recent experience, elected state leaders. In our opinion, the difficult

it is likely that any substantial federal assistance decisions to balance the state’s budget now are

for California’s cash flow problems would come preferable to Californians losing some control

with conditions. Recent federal bailouts of pri- over the state’s finances and priorities to federal

vate entities have involved those entities losing officials for years to come.

at least some operational autonomy to federal Legislature Should Not Assume Federal As‑

officials. At the very least, as occurred with sistance Will Be Forthcoming. We recommend

New York City’s loan guarantees in the 1970s, that the Legislature not proceed with the assump-

the federal government likely would charge the tion that federal assistance will be forthcoming to

state a fee for a federal loan guarantee—just deal with this summer and fall’s state cash flow

as a bank or bond insurer guaranteeing state problems. By beginning to address the state’s

LEGISLATIVE ANALYST’S OFFICE 15

AN LAO REPORT

budget and cash flow challenges immediately prompt actions to return the budget to balance

after the May special election, the Legislature and reduce the cash flow problem may help

will give the Treasurer and Controller the greatest convince federal officials that temporary assis-

range of options to address the state’s expected tance to the state is justified.

cash flow challenges. Moreover, the Legislature’s

CONCLUSION

While the February budget package and ➢ Act quickly—by late June or early July at

earlier legislative decisions have helped ease the the latest—to address the state’s budget

state’s cash crunch during 2008‑09, major chal- and cash flow challenges in order to help

lenges for the state’s cash flows loom in the sum- the Controller and Treasurer access the

mer and fall of 2009. In our opinion, the greatest short-term bond markets beginning in

near-term threat to the state paying its budgeted July.

bills on time would be a prolonged impasse by

the state in addressing California’s budgetary ➢ Consider additional cash management

and cash flow challenges after the May special measures, including possible additional

election. Moreover, we recommend that the delays in scheduled payments and accel-

Legislature not proceed with the assumption that eration of receipt of lottery securitization

federal assistance will be available to help the proceeds.

state address its cash flow crisis. Accordingly, we

➢ Be very cautious about accepting fed-

recommend that the Legislature:

eral assistance for the state’s cash-flow

➢ Focus in the coming weeks on reducing problems, especially given the strings that

the state’s cash flow borrowing need for may be attached to such aid.

2009‑10 to somewhere below $10 billion.

LAO Publications

This report was prepared by Jason Dickerson, and reviewed by Michael Cohen. The Legislative Analyst’s Office

(LAO) is a nonpartisan office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature.

To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as an E-mail subscription service,

are available on the LAO’s Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000,

Sacramento, CA 95814.

16 LEGISLATIVE ANALYST’S OFFICE

Você também pode gostar

- Weaponization Committee: HOW A "CYBERSECURITY" AGENCY COLLUDED WITH BIG TECH AND "DISINFORMATION" PARTNERS TO CENSOR AMERICANSDocumento37 páginasWeaponization Committee: HOW A "CYBERSECURITY" AGENCY COLLUDED WITH BIG TECH AND "DISINFORMATION" PARTNERS TO CENSOR AMERICANSJim Hoft100% (2)

- China and the US Foreign Debt Crisis: Does China Own the USA?No EverandChina and the US Foreign Debt Crisis: Does China Own the USA?Ainda não há avaliações

- Fifth Circuit Decision Against FDA in Apter CaseDocumento24 páginasFifth Circuit Decision Against FDA in Apter CaseAssociation of American Physicians and Surgeons100% (1)

- German Specification BGR181 (English Version) - Acceptance Criteria For Floorings R Rating As Per DIN 51130Documento26 páginasGerman Specification BGR181 (English Version) - Acceptance Criteria For Floorings R Rating As Per DIN 51130Ankur Singh ANULAB100% (2)

- Budget of the U.S. Government: A New Foundation for American Greatness: Fiscal Year 2018No EverandBudget of the U.S. Government: A New Foundation for American Greatness: Fiscal Year 2018Ainda não há avaliações

- KhanIzh - FGI Life - Offer Letter - V1 - Signed - 20220113154558Documento6 páginasKhanIzh - FGI Life - Offer Letter - V1 - Signed - 20220113154558Izharul HaqueAinda não há avaliações

- Ainsworth, The One-Year-Old Task of The Strange SituationDocumento20 páginasAinsworth, The One-Year-Old Task of The Strange SituationliliaAinda não há avaliações

- Understanding California's Fiscal Recovery: Primary Credit AnalystDocumento6 páginasUnderstanding California's Fiscal Recovery: Primary Credit Analystapi-227433089Ainda não há avaliações

- NY CashflowcrunchDocumento8 páginasNY CashflowcrunchZerohedgeAinda não há avaliações

- California's Fiscal Outlook: The 2011-12 BudgetDocumento45 páginasCalifornia's Fiscal Outlook: The 2011-12 BudgetRichard Costigan IIIAinda não há avaliações

- The FY2011 Federal BudgetDocumento24 páginasThe FY2011 Federal BudgetromulusxAinda não há avaliações

- OND Choeneck ING PLLC: MemorandumDocumento17 páginasOND Choeneck ING PLLC: MemorandumrkarlinAinda não há avaliações

- Implications For New York State of A Federal Government ShutdownDocumento4 páginasImplications For New York State of A Federal Government ShutdownElizabeth BenjaminAinda não há avaliações

- 2011 Quick StartDocumento24 páginas2011 Quick StartNick ReismanAinda não há avaliações

- New York State: Financial Plan For Fiscal Year 2012 First Quarterly UpdateDocumento28 páginasNew York State: Financial Plan For Fiscal Year 2012 First Quarterly UpdateNick ReismanAinda não há avaliações

- Usa Debt Crisis Republicans ViewDocumento6 páginasUsa Debt Crisis Republicans ViewAmit Kumar RoyAinda não há avaliações

- Enacted Budget Report 2020-21Documento22 páginasEnacted Budget Report 2020-21Luke ParsnowAinda não há avaliações

- The Debt Limit: History and Recent Increases: D. Andrew AustinDocumento27 páginasThe Debt Limit: History and Recent Increases: D. Andrew AustinGaryAinda não há avaliações

- Budget Response FY 2012 FINALDocumento17 páginasBudget Response FY 2012 FINALCeleste KatzAinda não há avaliações

- Nys Go Report 1109Documento5 páginasNys Go Report 1109jspectorAinda não há avaliações

- New York's Deficit Shuffle: April 2010Documento23 páginasNew York's Deficit Shuffle: April 2010Casey SeilerAinda não há avaliações

- Tentative Budget - Final Friday Nov 12 RevDocumento111 páginasTentative Budget - Final Friday Nov 12 RevAlfonso RobinsonAinda não há avaliações

- Budget Law SonDocumento16 páginasBudget Law SonObrabotka FotografiyAinda não há avaliações

- Research DocumentDocumento4 páginasResearch DocumentRachel E. Stassen-BergerAinda não há avaliações

- Focus Colorado: Economic and Revenue Forecast: Colorado Legislative Council Staff Economics Section September 20, 2010Documento72 páginasFocus Colorado: Economic and Revenue Forecast: Colorado Legislative Council Staff Economics Section September 20, 2010Circuit MediaAinda não há avaliações

- Extending The State Fiscal Relief Provisions of The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA)Documento8 páginasExtending The State Fiscal Relief Provisions of The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA)Public Policy and Education Fund of NYAinda não há avaliações

- Attacking The Fiscal Crisis - What The States Have Taught Us About The Way ForwardDocumento7 páginasAttacking The Fiscal Crisis - What The States Have Taught Us About The Way ForwardDamian PanaitescuAinda não há avaliações

- Solomon Island: Letter of Intent, Memorandum of Economic andDocumento19 páginasSolomon Island: Letter of Intent, Memorandum of Economic andkurukuru12Ainda não há avaliações

- Distribution of Spending: Why Study Public Finance?Documento1 páginaDistribution of Spending: Why Study Public Finance?penelopegerhardAinda não há avaliações

- Commission of Inquiry Report 4 - 4Documento8 páginasCommission of Inquiry Report 4 - 4michael_olson6605Ainda não há avaliações

- Chicag o Fed Letter: How Much Debt Does The U.S. Government Owe?Documento4 páginasChicag o Fed Letter: How Much Debt Does The U.S. Government Owe?TBP_Think_TankAinda não há avaliações

- Current Status of The State Fiscal Year 2010-11 Budget: Executive SummaryDocumento8 páginasCurrent Status of The State Fiscal Year 2010-11 Budget: Executive SummaryrkarlinAinda não há avaliações

- 2008 GAO Audit ReportDocumento24 páginas2008 GAO Audit ReportkaligelisAinda não há avaliações

- Finance AccountsDocumento5 páginasFinance Accountsravi yadavaAinda não há avaliações

- A DECADE OF SQUANDERED OPPORTUNITY by JM MinorDocumento55 páginasA DECADE OF SQUANDERED OPPORTUNITY by JM MinorDesmond Sullivan100% (1)

- 2016 17 Enacted Budget FinplanDocumento47 páginas2016 17 Enacted Budget FinplanMatthew HamiltonAinda não há avaliações

- Report On The State Fiscal Year 2014 - 15 Enacted Budget Financial Plan and The Capital Program and Financing PlanDocumento37 páginasReport On The State Fiscal Year 2014 - 15 Enacted Budget Financial Plan and The Capital Program and Financing PlanRick KarlinAinda não há avaliações

- Budget Overview 2014Documento44 páginasBudget Overview 2014Juan FordAinda não há avaliações

- List of Statements in Finance Account: Volume-I: Summarised Statements 1 2Documento8 páginasList of Statements in Finance Account: Volume-I: Summarised Statements 1 2ARAVIND KAinda não há avaliações

- The $21 Billion State Budget: South Carolina's Three Spending CategoriesDocumento25 páginasThe $21 Billion State Budget: South Carolina's Three Spending CategoriesSteve CouncilAinda não há avaliações

- El2010 20Documento4 páginasEl2010 20arborjimbAinda não há avaliações

- Debt Limit Analysis: AU GUST 2017Documento63 páginasDebt Limit Analysis: AU GUST 2017National Press FoundationAinda não há avaliações

- Governor Withholding ReportDocumento4 páginasGovernor Withholding ReportColumbia Daily TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- 13 TH FC MemorandumDocumento141 páginas13 TH FC Memorandumatikbarbhuiya1432Ainda não há avaliações

- 2014-15 Financial Plan Enacted BudgetDocumento37 páginas2014-15 Financial Plan Enacted BudgetjspectorAinda não há avaliações

- Office of The State Comptroller: Executive SummaryDocumento5 páginasOffice of The State Comptroller: Executive SummaryCeleste KatzAinda não há avaliações

- Sovereigns: U.S. Public Finances - Overview and OutlookDocumento15 páginasSovereigns: U.S. Public Finances - Overview and OutlookchanduAinda não há avaliações

- Macroeconomics Effects of Structural Fiscal Policy Changes in ColombiaDocumento44 páginasMacroeconomics Effects of Structural Fiscal Policy Changes in ColombiaAndres ZapataAinda não há avaliações

- Do Budget Deficits Cause in Ation?: by Keith SillDocumento8 páginasDo Budget Deficits Cause in Ation?: by Keith SillluminaAinda não há avaliações

- Timing The US Melt Down and RebirthDocumento10 páginasTiming The US Melt Down and RebirthchartcruzerAinda não há avaliações

- State Budget Shortfalls 2010Documento10 páginasState Budget Shortfalls 2010Nathan MartinAinda não há avaliações

- Quick Start Report - 2011-12 - Final 11.5.10Documento50 páginasQuick Start Report - 2011-12 - Final 11.5.10New York SenateAinda não há avaliações

- 2010 Albany BudgetDocumento187 páginas2010 Albany BudgettulocalpoliticsAinda não há avaliações

- 2016 17 Enacted Budget Report PDFDocumento74 páginas2016 17 Enacted Budget Report PDFNick ReismanAinda não há avaliações

- Federal DebtDocumento14 páginasFederal Debtabhimehta90Ainda não há avaliações

- 3rd World CrisisDocumento7 páginas3rd World CrisisD Attitude KidAinda não há avaliações

- Comentario PR Breckinridge Marzo 2012 NotiCelDocumento6 páginasComentario PR Breckinridge Marzo 2012 NotiCelnoticelmesaAinda não há avaliações

- 2011 EUA Crise Teto Da DívidaDocumento12 páginas2011 EUA Crise Teto Da DívidaGabriel LaguerraAinda não há avaliações

- Measures To Enhance Zimbabwe's SpaceDocumento26 páginasMeasures To Enhance Zimbabwe's SpaceBhea BañezAinda não há avaliações

- Macro 7Documento12 páginasMacro 7Àlex SolàAinda não há avaliações

- HIM2016Q3NPDocumento7 páginasHIM2016Q3NPlovehonor0519Ainda não há avaliações

- DC Cuts: How the Federal Budget Went from a Surplus to a Trillion Dollar Deficit in 10 YearsNo EverandDC Cuts: How the Federal Budget Went from a Surplus to a Trillion Dollar Deficit in 10 YearsAinda não há avaliações

- Reynolds Public Health Proclamation - 2020.04.06Documento5 páginasReynolds Public Health Proclamation - 2020.04.06Shane Vander HartAinda não há avaliações

- USD TLGP MaturitiesDocumento1 páginaUSD TLGP MaturitiesCreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- IG Fundamentals Q22010Documento1 páginaIG Fundamentals Q22010CreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- SPX Now and ThenDocumento1 páginaSPX Now and ThenCreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- Credit ContractionDocumento1 páginaCredit ContractionCreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- IG-HY Vs Stocks Relative-ValueDocumento1 páginaIG-HY Vs Stocks Relative-ValueCreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- HY-IG Vs StocksDocumento1 páginaHY-IG Vs StocksCreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- SPL 20101019Documento1 páginaSPL 20101019CreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- HY Vs IG DurationDocumento1 páginaHY Vs IG DurationCreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- EUC and 99-Week-Lagged Initial ClaimsDocumento1 páginaEUC and 99-Week-Lagged Initial ClaimsCreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- CDR Csa 201007Documento1 páginaCDR Csa 201007CreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- IG Over TSYDocumento1 páginaIG Over TSYCreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- HY-IG Vs EquityDocumento1 páginaHY-IG Vs EquityCreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- EUR Vs GDP-Weighted CDSDocumento1 páginaEUR Vs GDP-Weighted CDSCreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- C&I Loans + ABCP - Aggregate CreditDocumento1 páginaC&I Loans + ABCP - Aggregate CreditCreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- CDR Csa Aug2010Documento1 páginaCDR Csa Aug2010CreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- CDR Csa Scatter Aug10Documento1 páginaCDR Csa Scatter Aug10CreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- FSB30 IntrinsicsDocumento1 páginaFSB30 IntrinsicsCreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- IG Range CompressionDocumento1 páginaIG Range CompressionCreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- CDR Csa 20100813Documento1 páginaCDR Csa 20100813CreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- IG Weekly RangeDocumento1 páginaIG Weekly RangeCreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- Exchange Rate Regime Analysis For The Chinese YuanDocumento10 páginasExchange Rate Regime Analysis For The Chinese YuanCreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- Spread Leverage ComparisonDocumento1 páginaSpread Leverage ComparisonCreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- CDR Csa 20100716Documento1 páginaCDR Csa 20100716CreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- IG Vs TSY CycleDocumento1 páginaIG Vs TSY CycleCreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- JUN Roll by SectorDocumento1 páginaJUN Roll by SectorCreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- Implied CorrelationDocumento1 páginaImplied CorrelationCreditTraderAinda não há avaliações

- Espiritualidad AFPP - 2018 PDFDocumento5 páginasEspiritualidad AFPP - 2018 PDFEsteban OrellanaAinda não há avaliações

- Final Manuscript GROUP2Documento102 páginasFinal Manuscript GROUP222102279Ainda não há avaliações

- Umur Ekonomis Mesin RevDocumento3 páginasUmur Ekonomis Mesin Revrazali akhmadAinda não há avaliações

- Qi Gong & Meditation - Shaolin Temple UKDocumento5 páginasQi Gong & Meditation - Shaolin Temple UKBhuvnesh TenguriaAinda não há avaliações

- Posi LokDocumento24 páginasPosi LokMarcel Baque100% (1)

- DSM-5 Personality Disorders PDFDocumento2 páginasDSM-5 Personality Disorders PDFIqbal Baryar0% (1)

- Buddahism ReportDocumento36 páginasBuddahism Reportlaica andalAinda não há avaliações

- Community Medicine DissertationDocumento7 páginasCommunity Medicine DissertationCollegePaperGhostWriterSterlingHeights100% (1)

- Just Another RantDocumento6 páginasJust Another RantJuan Manuel VargasAinda não há avaliações

- High School Students' Attributions About Success and Failure in Physics.Documento6 páginasHigh School Students' Attributions About Success and Failure in Physics.Zeynep Tuğba KahyaoğluAinda não há avaliações

- W2 - Fundementals of SepDocumento36 páginasW2 - Fundementals of Sephairen jegerAinda não há avaliações

- Environmental Product Declaration: Plasterboard Knauf Diamant GKFIDocumento11 páginasEnvironmental Product Declaration: Plasterboard Knauf Diamant GKFIIoana CAinda não há avaliações

- The Integration of Technology Into Pharmacy Education and PracticeDocumento6 páginasThe Integration of Technology Into Pharmacy Education and PracticeAjit ThoratAinda não há avaliações

- Quality Assurance Kamera GammaDocumento43 páginasQuality Assurance Kamera GammawiendaintanAinda não há avaliações

- Indiana Administrative CodeDocumento176 páginasIndiana Administrative CodeMd Mamunur RashidAinda não há avaliações

- Soal 2-3ADocumento5 páginasSoal 2-3Atrinanda ajiAinda não há avaliações

- Owner'S Manual: Explosion-Proof Motor Mf07, Mf10, Mf13Documento18 páginasOwner'S Manual: Explosion-Proof Motor Mf07, Mf10, Mf13mediacampaigncc24Ainda não há avaliações

- Calculation Condensation StudentDocumento7 páginasCalculation Condensation StudentHans PeterAinda não há avaliações

- CRM McDonalds ScribdDocumento9 páginasCRM McDonalds ScribdArun SanalAinda não há avaliações

- Management of Developing DentitionDocumento51 páginasManagement of Developing Dentitionahmed alshaariAinda não há avaliações

- Product Sheet - Parsys Cloud - Parsys TelemedicineDocumento10 páginasProduct Sheet - Parsys Cloud - Parsys TelemedicineChristian Lezama Cuellar100% (1)

- BARCODESDocumento7 páginasBARCODESChitPerRhosAinda não há avaliações

- FINALE Final Chapter1 PhoebeKatesMDelicanaPR-IIeditedphoebe 1Documento67 páginasFINALE Final Chapter1 PhoebeKatesMDelicanaPR-IIeditedphoebe 1Jane ParkAinda não há avaliações

- Wa0016Documento3 páginasWa0016Vinay DahiyaAinda não há avaliações

- Marine Advisory 03-22 LRITDocumento2 páginasMarine Advisory 03-22 LRITNikos StratisAinda não há avaliações

- Faculty Based Bank Written PDFDocumento85 páginasFaculty Based Bank Written PDFTamim HossainAinda não há avaliações

- 2022.08.09 Rickenbacker ComprehensiveDocumento180 páginas2022.08.09 Rickenbacker ComprehensiveTony WintonAinda não há avaliações