Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Ensuring A Stable and Denuclearized Korean Peninsula

Enviado por

Evan KalikowTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Ensuring A Stable and Denuclearized Korean Peninsula

Enviado por

Evan KalikowDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Ensuring a Stable and Denuclearized Korean Peninsula By: Evan Kalikow

Executive Summary With nuclear ambitions and a new leader in Kim Jong-un, North Korea proves to be a cause for concern among states worldwide. China and the United States are particularly affected by the threat of North Korean nuclear weaponry. In order to promote denuclearization and bring stability and peace to the Korean peninsula, it is recommended that the United States lead a set of negotiations in which it eases from its position of denuclearization-above-all-other-issues and works with China to best use the latters leverage over North Korea to promote peace and diminished nuclear weaponry. Background Information The Korean peninsula has been a location of uncertainty and intrigue in international politics for quite some timein particular because of the powerful and often uncooperative North Korean regime. As a state with ambitions to develop a nuclear program, North Korea plays an important role in the international sphere, and policies made with regards to North Korea have the potential to affect many sovereign states. North Koreas nuclear weapon aspirations have caused prominent states to take action. For many years in the past decade, the United States, Japan, China, Russia, and South Korea have engaged with North Korea in Six-Party Talks, which negotiated various forms of aid and diplomatic resources to North Korea in exchange for nuclear destabilization (Cha 2009: 121). However, these discussions ended in July of 2009 after North Korea violated the terms of the talks by issuing three tests of nuclear weapons (Cha 2009: 121-122). With the transfer of power from the late Kim Jong-il to his son Kim Jong-un in December 2011, new opportunities for diplomatic games and denuclearization have arisen. What these opportunities will lead to and how they are shaped will depend on the complex interests of two countries: the China and the United States. China must walk a fine line between supporting North Korea and working to denuclearize the state. China does not want to see North Korea expand its nuclear programin fact, China has potentially more leverage

than the United States to ensure that North Koreas power remains limited, as it provides North Koreans access to necessities such as food, fuel, and medicine and can limit that access if necessary (Shen 2009: 177). In fact, China provides approximately 70 percent of [North Koreas] oil and most of its food assistance and Chinese economic assistance to North Korea accounts for about half of all Chinese foreign aid (Glaser and Billingsley 2012:5). On the other hand, the government of China is terrified that engaging in such preventative measures would destabilize North Korea and cause millions of North Korean refugees to seek asylum within the borders of China (Shen 2009: 177-178). Conversely, the United States is not nearly as integrated with North Korea as is China. The United States, however, is more adamant than China about limiting North Koreas military and nuclear capabilities, as the US has obligations through alliances with Japan and South Korea to help protect the countries from any potential aggression from North Korea (Chanlett-Avery and Rinehart 2012: 4). These competing influences among the two most influential state actors make a potential solution to the North Korean problem difficult, but there are several feasible policy options available for consideration. Option 1: China-Driven Negotiations This policy option would follow the model set by Hui Zhang in his August 2009 article Ending North Koreas Nuclear Ambitions: The Need for Stronger Chinese Action. Zhang suggests that, in the wake of the failure of the Six-Party Talks, it is Chinas responsibility to take a harder stand against a nuclear North Korea because China has the necessary leverage and a more powerful North Korea would work against Chinese interests (Zhang 2009). This would likely be an effective policy plan, as China has the capability to deny necessary resources to North Korea in exchange for cooperation regarding denuclearization. The United States, South Korea, and Japan would support these actions as well, as they would provide for a less nuclear and more stable Korean peninsula. Chinese citizens would also favour such a proposal, as more than two-thirds of [recent survey]

respondents believe Beijing should take stronger actions to constrain Pyongyangs nuclear ambitions (Zhang 2009). However, China may not be willing to suspend (or threaten to suspend) aid to the area, fearing that a sudden end of essential aid programs could cause a diaspora of North Korean refugees to China. Although China has more leverage to negotiate with North Korea than the United States in this issue, it also bares more of the risk. Option 2: US-Driven Negotiations In contrast to the first option would be a policy option placing the United States as the primary decision-maker, as proposed by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). That CSIS report, authored by Bonnie Glaser and Brittany Billingsley, suggests that China has not had any incentive to waver from its policy of giving significant aid to North Korea and that a change in Chinese policy can only come from United States pressure. They argue that, in order for this change to take place, the United States must not relax on its position of holding other issues of negotiation (i.e. peace treaties, aid, normalization, etc.) conditional on denuclearization; otherwise, the negotiation process will not be successful (Glaser and Billingsley 2012: 23). This policy also addresses concerns in the event of the failure or dissolution of North Korea, saying that the United States can assuage Chinese fears of the massive costs it would incur by offering financial support from Japan, South Korea, and the United States itself (Glaser and Billingsley 2012: 23-34). This is a well-reasoned policy that addresses multiple issues regarding the North Korean nuclear situation. It would prove more fruitful than earlier diplomatic discussions; additionally, it would give China more confidence that a denuclearized or more lightly aided North Korea would not fail (or, failing that, that the United States, South Korea, and Japan would assist in the collateral damage of North Korean failure). It is possible, however, that this policy would be difficult to sell to the United States population. The view of the North Korean government among American citizens tends to be negative, and a policy shift away from a denuclearization or

bust approach may not be amenable to the American electorate, especially if such a policy would also allocate funds to give aid to North Korea or China. Option 3: Third Party Negotiations Another potential solution would be for an international organization such as the United Nations to create a situation in which China and the United States would engage in talks with North Korea. Through this arrangement, the UN could set the stage for a negotiation with the caveats that the United States be comfortable deemphasizing denuclearization above all other issues, that China be more willing to use its aid as a bargaining tool, and that North Korea cease provocation through nuclear missile tests. This policy would be beneficial in two ways. First, by having a third party initiate the negotiations, there would be less domestic and international political damage to China and the United States than if either one had made the initial call for discussions. Second, because the UN would back the negotiations, they would have international support, increasing the pressure on the participating states to reach a fair and reasonable agreement. This policy may be too optimistic, though, as it would be difficult for the UN to use its influence to coerce such powerful states into making crucial concessions before negotiations even properly begin. Recommended Policy Of these policy recommendations, Option 2: US-Driven Negotiations is the most likely to be effective and practical and is thus the recommended course of action. Past United States endeavors to negotiate peace with North Korea have ended in frustration, and those experiences have jaded the general American public, causing thoughts of North Korea negotiating primarily to extract concessions from its counterparts while making commitments it does not intend to keep to run prevalent (Pritchard and Tinelli 2010: 9). In order to combat this perception and have North Korea be true to their word, China must be willing to threaten suspension of aid to North Korea. China will only be amenable to such actions if the United States will offer support. China-driven negotiations would work, but

there is no motivation for China to change its strategy without a push from the United States. And while the UN-driven negotiation policy could be effective, its implementation is not nearly as plausible as a US-driven negotiation policy. Thus, the policy of US-driven negotiations has the greatest potential to produce real results and stabilize the Korean peninsula.

References Cha, V (2009) What Do They Really Want?: Obamas North Korea Conundrum, The Washington Quarterly 32 (4), pp. 119-138 Chanlett-Avery, E and Rinehart, I (2012) North Korea: U.S. Relations, Nuclear Diplomacy, and Internal Situation, Congressional Research Service, pp. 1-23 Glaser, B and Billingsley, B (2012) Reordering Chinese Priorities on the Korean Peninsula, Center For Strategic and International Studies, pp. 1-68 Pritchard, C and Tilelli, J (2010) U.S. Policy Toward the Korean Peninsula, Council on Foreign Relations, pp. 1-76 Shen, D (2009) Cooperative Denuclearization toward North Korea, The Washington Quarterly 32 (4), pp. 175-188 Zhang, H (2009) Ending North Korea's Nuclear Ambitions: The Need for Stronger Chinese Action, Arms Control Today, July/August 2009

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- DepEd Form 137-ADocumento2 páginasDepEd Form 137-Akianmiguel84% (116)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Judy Carter - George Irani - Vamık D. Volkan - Regional and Ethnic Conflicts - Perspectives From The Front Lines, Coursesmart Etextbook-Routledge (2008)Documento564 páginasJudy Carter - George Irani - Vamık D. Volkan - Regional and Ethnic Conflicts - Perspectives From The Front Lines, Coursesmart Etextbook-Routledge (2008)abdurakhimovamaftuna672Ainda não há avaliações

- Penn State Journal of International Affairs Spring 2012 Issue 2 Volume 1Documento113 páginasPenn State Journal of International Affairs Spring 2012 Issue 2 Volume 1Evan KalikowAinda não há avaliações

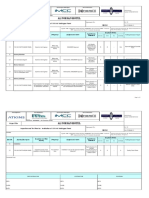

- Itp Installation of 11kv HV Switchgear Rev.00Documento2 páginasItp Installation of 11kv HV Switchgear Rev.00syed fazluddin100% (1)

- Motion For Leave Demurrer) MelgarDocumento11 páginasMotion For Leave Demurrer) MelgarRichard Conrad Foronda Salango100% (2)

- Warlords On The Path of DestructionDocumento31 páginasWarlords On The Path of DestructionEvan KalikowAinda não há avaliações

- Terrorist Organizational Success, Violence, and State SponsorshipDocumento35 páginasTerrorist Organizational Success, Violence, and State SponsorshipEvan KalikowAinda não há avaliações

- Ending The Cuban Embargo - A New Policy For A New AdministrationDocumento40 páginasEnding The Cuban Embargo - A New Policy For A New AdministrationEvan KalikowAinda não há avaliações

- The Evolution of British Eugenic Thought Through Novels and LiteratureDocumento14 páginasThe Evolution of British Eugenic Thought Through Novels and LiteratureEvan KalikowAinda não há avaliações

- The Tactics, Goals, and Outcomes of The Liberation Tigers of Tamil EelamDocumento10 páginasThe Tactics, Goals, and Outcomes of The Liberation Tigers of Tamil EelamEvan Kalikow100% (2)

- The Invasion of Iraq As The Case Against Preemtive Self-DefenseDocumento11 páginasThe Invasion of Iraq As The Case Against Preemtive Self-DefenseEvan KalikowAinda não há avaliações

- Regions of War and PeaceDocumento7 páginasRegions of War and PeaceEvan KalikowAinda não há avaliações

- Cuban Embargo PowerpointDocumento13 páginasCuban Embargo PowerpointEvan KalikowAinda não há avaliações

- Ethnic Party Bans and Territorial Autonomy - Managing Ethnic ConflictDocumento12 páginasEthnic Party Bans and Territorial Autonomy - Managing Ethnic ConflictEvan KalikowAinda não há avaliações

- The Evolution of British Eugenic Thought Through Novels and LiteratureDocumento14 páginasThe Evolution of British Eugenic Thought Through Novels and LiteratureEvan KalikowAinda não há avaliações

- Penn State Journal of International Affairs Fall 2011 Issue 1 Volume 1Documento62 páginasPenn State Journal of International Affairs Fall 2011 Issue 1 Volume 1Evan KalikowAinda não há avaliações

- The Evolution of British Eugenic Thought Through Novels and LiteratureDocumento14 páginasThe Evolution of British Eugenic Thought Through Novels and LiteratureEvan KalikowAinda não há avaliações

- Research Design Paper Research QuestionDocumento13 páginasResearch Design Paper Research QuestionEvan KalikowAinda não há avaliações

- Regions of War and PeaceDocumento6 páginasRegions of War and PeaceEvan KalikowAinda não há avaliações

- Evaluation ArgumentDocumento6 páginasEvaluation ArgumentEvan KalikowAinda não há avaliações

- Personal NarrativeDocumento4 páginasPersonal NarrativeEvan KalikowAinda não há avaliações

- Ending The Cuban Embargo - A New Policy For A New AdministrationDocumento40 páginasEnding The Cuban Embargo - A New Policy For A New AdministrationEvan KalikowAinda não há avaliações

- Argument of DefinitionDocumento4 páginasArgument of DefinitionEvan KalikowAinda não há avaliações

- General and Subsidiary Ledgers ExplainedDocumento57 páginasGeneral and Subsidiary Ledgers ExplainedSavage NicoAinda não há avaliações

- Court Documents Detail How Deputies Found Victim in Franklin County Alleged Murder-SuicideDocumento3 páginasCourt Documents Detail How Deputies Found Victim in Franklin County Alleged Murder-SuicideWSETAinda não há avaliações

- Abner PDSDocumento7 páginasAbner PDSKEICHIE QUIMCOAinda não há avaliações

- f2 Fou Con Sai PL Qa 00002 Project Quality Plan Rev 00Documento52 páginasf2 Fou Con Sai PL Qa 00002 Project Quality Plan Rev 00Firman Indra JayaAinda não há avaliações

- Premiums and WarrantyDocumento8 páginasPremiums and WarrantyMarela Velasquez100% (2)

- PPL Law R13Documento13 páginasPPL Law R13Dhruv JoshiAinda não há avaliações

- Activity 7.rizalDocumento2 páginasActivity 7.rizalBernadeth BerdonAinda não há avaliações

- MC 2021-086 General Guidelines On The International Organization For Standardization ISO Certification of The PNP Office Units Revised 2021Documento10 páginasMC 2021-086 General Guidelines On The International Organization For Standardization ISO Certification of The PNP Office Units Revised 2021Allysa Nicole OrdonezAinda não há avaliações

- ISPS Code Awareness TrainingDocumento57 páginasISPS Code Awareness Trainingdiegocely700615100% (1)

- Bitcoin Wallet PDFDocumento2 páginasBitcoin Wallet PDFLeo LopesAinda não há avaliações

- BatStateU-FO-NSTP-03 - Parent's, Guardian's Consent For NSTP - Rev. 01Documento2 páginasBatStateU-FO-NSTP-03 - Parent's, Guardian's Consent For NSTP - Rev. 01Gleizuly VaughnAinda não há avaliações

- Case Study Report On ZambiaDocumento81 páginasCase Study Report On ZambiaAsep Abdul RahmanAinda não há avaliações

- Business Studies PamphletDocumento28 páginasBusiness Studies PamphletSimushi SimushiAinda não há avaliações

- Test 3 - Part 5Documento4 páginasTest 3 - Part 5hiếu võ100% (1)

- Doctrine of Basic Structure DebateDocumento36 páginasDoctrine of Basic Structure DebateSaurabhAinda não há avaliações

- Term Paper On Police CorruptionDocumento7 páginasTerm Paper On Police Corruptionafdtzvbex100% (1)

- Diplomacy settings and interactionsDocumento31 páginasDiplomacy settings and interactionscaerani429Ainda não há avaliações

- D.A.V. College Trust case analysisDocumento9 páginasD.A.V. College Trust case analysisBHAVYA GUPTAAinda não há avaliações

- Inventory Accounting and ValuationDocumento13 páginasInventory Accounting and Valuationkiema katsutoAinda não há avaliações

- Dyslexia and The BrainDocumento5 páginasDyslexia and The BrainDebbie KlippAinda não há avaliações

- Cignal: Residential Service Application FormDocumento10 páginasCignal: Residential Service Application FormJUDGE MARLON JAY MONEVAAinda não há avaliações

- Active and Passive VoiceDocumento8 páginasActive and Passive Voicejerubaal kaukumangera100% (1)

- UL E483162Cajas EVTDocumento2 páginasUL E483162Cajas EVTYeison Alberto Murillo Guzman0% (1)

- Caram V CaDocumento3 páginasCaram V Caherbs22221473Ainda não há avaliações

- Court of Appeals Upholds Dismissal of Forcible Entry CaseDocumento6 páginasCourt of Appeals Upholds Dismissal of Forcible Entry CaseJoseph Dimalanta DajayAinda não há avaliações

- JMRC Vacancy Circular For DeputationDocumento20 páginasJMRC Vacancy Circular For DeputationSumit AgrawalAinda não há avaliações