Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

From War Heroes To Sporting Heroes

Enviado por

John SteffDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

From War Heroes To Sporting Heroes

Enviado por

John SteffDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

From War Heroes to Sporting Heroes: A Brief Study of the Transformation of the War Hero into a Sporting Hero

in Iliad 22 and 23.

James Duncan Stratford Book 23 of Homers Iliad, written in the 8th century BCE, is the first literary account of ancient sporting practices.1 The focus of book 23 is the funeral games sponsored by Achilleus to honour his dead companion Patroklos. Until Book 23 each of these activities has been connected solely with battle. The participants also are all, without exception, warriors. There is one obvious difference, however, between this honorary competition and the conflicts that precede it. The object of the competition for the victor is not to kill the opponent but rather to outperform him in a particular skill.2 In this paper I suggest that the funeral games and Achilleus hunting of Hector which directly proceed them, signal a shift in emphasis away from the deadly field of battle toward the somewhat less deadly but just as value-laden arena of sport. In doing so it is my purpose to look at the movement from war to ritualised combat in early sport as a reaction to war itself and to stimulate speculation on the turning away from the military establishment in favour of organised sport in modern Australian culture. For the best part of the first 22 books of the Iliad the audience witnesses vast swathes of narrative devoted to vivid descriptions of mortal combat involving both the princes and the faceless masses they lead. During the siege of Troy a range of weapons and techniques are employed by the warriors with varying degrees of success. In warfare as in sport a warrior is more likely to succeed if he has mastered a number of weapons or fighting skills. The aristeia (duel) between Achilleus and Hector is a prime example of multi-skilled warriors as we watch them progressively move from one form of combat to the next and is told by Homer over 159 lines from 22.136 to 22.327. The first 114 of those (22.136-250) are dedicated to the chase (or race) three times around the walls of Troy, followed by a spear attack (22.270293). Over the final 22 lines (22.305-327) Hector unsuccessfully charges Achilleus with his sword. It is significant that each change in the action is precipitated by the intervention of the gods. It is Athene, in the guise of Deiphobos who materialises to convinces Hector to stop running and face Achilleus in combat (22.225-47) and it is the same Dephobos who conveniently disappears when Hector needs his spear (22.293-295), forcing 3 Hector to rely on his sword a poor match for Achilleus infamous ash spear. A brief analysis of some of the main features of the Hector versus Achilleus showdown indicates that there are some important structural similarities between it and the funeral games, which come shortly after them. In the light of such similarities it is possible to view the aristeia of book 22 as a deliberate build up to the funeral games of book 23. Homer in fact explicitly compares the events to one another: 5

From War Heroes to Sporting Heroes

it was a great man who fled, but far better he who pursued him rapidly, since here was no festal beast, no ox-hide they strove for, for these are the prizes that are given men for their running. No they ran for the life of Hector, breaker of horses. As when about the turnposts racing single-foot horses run at full speed, when a great prize is laid up for the winning, a tripod or a woman, in games for a mans funeral ( II. 22.158-65).4 The essentially competitive nature of combat is referred to on a second instance during the chase: But brilliant Achilleus kept shaking his head at his own people and would not let them throw their bitter projectiles at Hector for fear the thrower might win the glory, and himself come second ( II. 22.205-8). Of course it would be absurd in such a contest for the honours to fall to any random participant, especially one of the hoi poloi (the masses). The honour of Hectors death must and will fall to one man and one man alone, Achilleus. Interference in such a contest would be completely inappropriate, except if it comes from Olympians, which of course it does. It is also important to remember that these warriors are meant to be the best of the Achaian and Trojan forces and yet now with the focus on them we are made aware of their own limitations; each is as capable of missing their target as the other. After all Achilleus and Hector are more or less equally matched warriors. The deciding factor is not, therefore, a matter of who is the better one but who receives the heavier allotment of the weights of Death on the golden scales of Zeus (22.208-13). Funeral games in Ancient Greece appear in both the literary and archaeological record to be held exclusively for particular warriors who had died in combat. The games were designed to celebrate the various acts of warfare in general and to recall the final combat of the dead warrior in particular.5 In the funeral games for Patroklos sponsored by Achilleus in book 23 of Homers epic poem the Illiad there were eight events. They included a horse race, boxing and wrestling matches, a foot race, spear competition, a throwing competition and an archery contest. It would be pointing out the obvious to explain how each of these activities was derived from warfare. On the battlefield skills must be learnt by necessity. In funeral games participants are able to choose which, if any, of the events they will compete in, competitors are able to specialise. On the battlefield no such specialisation is possible. Of course which event is chosen will be determined by which skill the warrior feels most confident in and we can safely assume that the warriors that contest in each of the events would normally be exemplars in that form of combat on the battlefield. One such man is the boxer Epeios. Whilst being supremely confident of victory in the match it is interesting to note that he does not regard himself as a great warrior: I say no other of the Achaians will beat me at boxing and lead off the jenny. I claim that I am the champion. Is it not enough that I fall short in battle? Since it could not be ever, that a man could be a master in every endeavour (II. 23. 668-671). For Epeios and the rest of Patroklos comrades, the funeral games are an attempt to recall the 6

ASSH Bulletin # 36, August 2002

final combat of the warrior, in which his loss resulted from being outperformed in a particular skill. Homers funeral games clearly present an opportunity for warriors who excel in particular skills to gain honours they would not be able to win in combat. Likewise, where on the battlefield a victory normally results in the death of the loser, in Patroklos games all the losers are honoured with a prize of their own. In fact, the number of contestants is limited to the number of prizes on offer.6 Those who elect themselves to compete do so because they know that they are among the best. The funeral games of Iliad 23 are both derived from war and celebrate exclusively the death of some participants in war, namely the promachoi (those who fight at the forefront). However, the skilful and egalitarian nature of competition celebrates the virtuosity of the specialist who might be disadvantaged in the chaos of battle. At the same time the redistribution of honours deprives, at least temporarily, the act of war of its ability to make or break the reputations of its victors and victims. The way in which honours are distributed to the living contestants in the funeral games has direct repercussions on the way the dead warrior can be perceived by their community. Patroklos, in his own combat, was clearly the looser, but this is not to say that as a warrior he was an inferior warrior on all counts and unworthy of honours, when in fact the opposite is true. Nonetheless, Patroklos defeat and death in battle presents a problem for those celebrating his life and his status as a great warrior. Redfield asserts that the games are an opportunity to restore and even reaffirm the status of the fallen warrior whilst simultaneously purifying the dead heros sullied reputation. In funeral games, therefore, the heros community celebrate the death of the victim of combat by enacting conflicts in which the loser is not a victim. Thus they purify the impurity latent in the status of the victim, not by reforming the situation (which is beyond their power), but by denying the 7 signifying power of the heros final combat. Thus Patroklos is honoured as a fine warrior, even if not a victorious one in his final combat. It is important that this act of reclaiming a warriors honour takes place not as a revenge killing, although Achilleus has already done this, rather it takes place within the confines of the community. In doing so, the power of the battlefield is substituted and even denied in favour of that of the polis. Ultimately it is the polis and its inhabitants (the warriors community) that have the power to confirm or deny ones place within it. The critical difference between the contests in the games and on the battlefield is the presence or absence of death. The games replicate combat in most ways. The activities and the participants are the same (except for the enemy of course). The honoured contestants win horses, women, armour, cups and tripods, just as they would in battle. There are disputes over the calling of the various events and the distribution of the prizes. In the discourse of the funeral games even the gods play a part, to ensure the events transpire to their satisfaction. Indeed the games are also violent and accidents do occur in which contestants are hurt, some participants like Epeios even 7

From War Heroes to Sporting Heroes

threaten others with death should they loose. It is the absence of death, or at least intentional death, and the practice of distributing prizes to all contestants which transforms an elaborate contest into a ritual which celebrates the warriors participation in battle, without glorifying death itself. Nevertheless the funeral games take place as part of the celebration of death in combat. Although relatively harmless, these sports were not removed from the idea or even the presence of death altogether. By contrast, their enactment is held in the shadow of the funeral pyre as the crowning glory of the funeral rituals, for the very purpose of celebrating the glorious life (and death) of the hero. Taking place just after the burning of the pyre we can almost smell the ash lingering in the air which the competitors inhale, yet Homer implies that the sports have significance over the older markers of death. Within the narrative of Patroklos games Homer, via the wise old Nestor, subtly questions the ability of physical memorials to honour the dead over time. Just before the great chariot race the old Nestor takes the younger Antilochos aside to impart some of the wisdom of his years, Most of his monologue is concerned with practical advice such as when to hold the horses back and when to let them go. There is one very interesting remark concerning the corner marker which is worthy of consideration. I will give you a clear mark and you will not fail to notice it. There is a dry stump standing up from the ground about six feet, oak, it may be, or pine, and not rotted away by rain-water, and two white stones are leaned against it, one on either side, at the joining place of the ways, and there is smooth driving around it. Either it is the grave-mark of someone who died long ago, or it was set as a racing goal by men living before our time ( II 23: 326332). What is striking about this is Nestors uncertainty concerning the origins of the marker. Nestor is certain that Antilochos wont miss the marker, but its significance is not clear even for a stationary and learned bystander. If it was just an old weathered tree stump, no meaning has been lost. However, if it was a grave-marker, the sign, which the marker definitely is, it has lost all connection with its intended referent. So, if there was anyone buried under the marker, their death and any importance connected to it have been almost completely lost. Now their death is ultimately and utterly meaningless. In the light of the present argument, there would appear to be little point to death when there is no certainty that the symbols created to honour the dead cannot be mistaken for mere anomalies of nature. Ultimately it is much more fruitful, or at least lest wasteful, to participate in non-lethal competition. Over the last one hundred years it is possible to see two divergent but connected movements in Australian culture. On the one hand, arguably ever since the First World War, the cost of war in terms of human life has been a major issue, climaxing during the Vietnam War. There are many indicators of this shift in modern society, just as there were in Classical Greece. Literary 8

ASSH Bulletin # 36, August 2002

sources and the visual arts, public and private patronage of the respective establishments and the infrastructure that supports them all indicate a change in Australian societys attitude toward war. In Australia at least, the sporting arena has become the new breeding ground of popular heroes. However, modern sport has borrowed, just as ancient sport did, much of the internal and even external mechanisms from the military. Whilst sporting acts no longer resemble modern combat to the same degree (your average soldier would find limited use for a drop-kick or a 8 torpedo), the emphases on training and strategy, the distribution of honours like the Brownlow medal, clearly have their origins in warfare. It is also interesting to look at the language and code-specific terminology used in sport. Words like captain, elimination match and the more recent blood rule adopted by the AFL. Intense competition draws upon the most intense competition of all that in which two warriors set to kill one another. However, just as we saw with Patroklos funeral games, the parallel to combat is there, but crucially, death is not. Just as Nestor questions the significance of the marker in the Iliad, we also question the value of deadly combat and, like Epeios, prefer to carry off our honours in life rather than in death. One contemporary Australian film (relative to Homer at least) in which sport appears in apposition to warfare is Peter Weirs film Gallipoli (1981).9 The story follows the lives of two promising young sprinters, Archy Hamilton (Mark Lee) and Frank Dunne (Mel Gibson) from Western Australia who enlist to fight in the Australian army in 1915. Weirs narrative follows the classic heroic journey paradigm: the hero is called to face a little known and normally dangerous force in a far away land. Unlike Homers treatment of Patroklos funeral games, Weir does not attempt to connect running as a skill to war, although its applicability (and futility) is clear in the mass infantry charges. What is significant about this film, for the purposes of this paper, is the way in which the challenge of warfare is likened to the challenge of sporting competition and that the warrior is remembered as an athlete. In the final scene, a charge on the Turkish machine guns, Archy invokes the training mantra of his running coach, as a means of overcoming his own fear as he prepares to charge the Turkish trenches. What are your legs? Springs, Steel springs. What are you going to do with them? Hurl me down the track. How fast can you run? As fast as a leopard. How fast are you going to run? As fast as a leopard. Then lets see you do it. The charge is treated by Weir as Archys final race and the film ends when he is shot by an enemy machine gun. At that same moment the runner appears as the classic sprinter lunging for the finishing line. In this image the two heroic models of the warrior and the athlete are seamlessly superimposed upon one another. Unlike his last race in Western Australia, aptly titled The Gift, Archy gains no special honours at Gallipoli, instead he dies as one of the many, distinguished and possibly only remembered by his sporting honours. In this way Weir rewrites the funeral games of the Iliad.

From War Heroes to Sporting Heroes

NOTES:

1. Stephen G Miller, Arete: Greek Sports from the Ancient Sources, University of California Press, Los Angeles, Berkeley and Oxford, 1991, pp. 1-16. All quotes from the Iliad are taken from Richmond Lattimore (trans.), The Iliad of Homer, Chicago University Press, Chicago and London, 1961. 2. Of course on the battlefield, to outperform your enemy would usually result in victory and the enemys death. The designation of the participants in this event as exclusively male is simply because there are no women participating in battle and consequently in the funeral games either. That is not to say that immortal women didnt have their share of influence, just as they do in the main battle narrative of the Iliad. Athene, for one, intervenes in the chariot race to assist Diomedes by giving him his whip which had been dashed from his hands by the god Apollo. Directly after this she smashes the yoke of Eumelos chariot and causes a gruesome and potentially fatal crash. (23.382. ff.). 3. The name Dephobos seems to be a clear pun here as it can be translated from the Greek as fear (phobos) of the gods (dei). Definitely in this instance Hector should be afraid of the goddess Athene. 4. All quotations from the Iliad, unless otherwise cited, are from Richmond Lattimore, The Iliad of Homer, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 1951. 5. James M Redfield, Nature and Culture in the Iliad: the Tragedy of Hector, Duke University Press, Durham and London, 1994, p. 204. 6. Redfield, Nature and Culture in the Iliad, p. 206. 7. Redfield, Nature and Culture in the Iliad, p. 210. 8. Two types of kicks in Australian Rules football. 9. Gallipoli, 1981, (Peter Weir, Director).

10

Você também pode gostar

- Iliad Script - TypedDocumento15 páginasIliad Script - TypedJuliene De Los Santos100% (4)

- Greek Mythology A-ZDocumento16 páginasGreek Mythology A-ZJohn Edsel100% (3)

- Eusebius and The Jewish Authors 2006Documento360 páginasEusebius and The Jewish Authors 2006John Steff100% (3)

- Eusebius and The Jewish Authors 2006Documento360 páginasEusebius and The Jewish Authors 2006John Steff100% (3)

- Boddy, K. (2008) Boxing A Cultural HistoryDocumento480 páginasBoddy, K. (2008) Boxing A Cultural HistoryStokely1979100% (1)

- Illiad Summary With TaoDocumento9 páginasIlliad Summary With TaoChester CuarentasAinda não há avaliações

- About Where Troy Once StoodDocumento29 páginasAbout Where Troy Once StoodAdrian Bahrim100% (1)

- Carter - Gladiatorial Combat The Rules of Engagement 2006-2007 (p.107)Documento19 páginasCarter - Gladiatorial Combat The Rules of Engagement 2006-2007 (p.107)Martino Colonna-PretiAinda não há avaliações

- Semitic PapyrologyDocumento302 páginasSemitic PapyrologyJohn Steff100% (1)

- Pythagorean Philolaus'Pyrocentric UniverseDocumento15 páginasPythagorean Philolaus'Pyrocentric UniverseJohn Steff50% (2)

- The Heroic Code in BeowulfDocumento4 páginasThe Heroic Code in BeowulfBeowulf Odin Son100% (1)

- Debate (Hector Is A Better Leader Than Achilles in The Book The Iliad by Homer)Documento4 páginasDebate (Hector Is A Better Leader Than Achilles in The Book The Iliad by Homer)Syed Anwer ShahAinda não há avaliações

- Homer and HerodotusDocumento4 páginasHomer and HerodotusJudith UmesiAinda não há avaliações

- The Odyssey and IliadDocumento6 páginasThe Odyssey and IliadJulia Drechsel100% (1)

- Justification of War in Ancient GreeceDocumento98 páginasJustification of War in Ancient GreeceNikolaos KazanasAinda não há avaliações

- English 10Documento3 páginasEnglish 10Paul Pabilico PorrasAinda não há avaliações

- Submission Fighting and The Rules of Ancient Greek Wrestling (Pale) - Christopher MillerDocumento38 páginasSubmission Fighting and The Rules of Ancient Greek Wrestling (Pale) - Christopher Millerchef_samuraiAinda não há avaliações

- The Planetary Theory of Ibn al-Shatir: Reduction of the Geometric Models to Numerical TablesDocumento9 páginasThe Planetary Theory of Ibn al-Shatir: Reduction of the Geometric Models to Numerical TablesJohn SteffAinda não há avaliações

- Chronology of The Aramaic Papyri From ElephantineDocumento5 páginasChronology of The Aramaic Papyri From ElephantineJohn SteffAinda não há avaliações

- Brawl: A Behind-the-Scenes Look at Mixed Martial Arts CompetitionNo EverandBrawl: A Behind-the-Scenes Look at Mixed Martial Arts CompetitionNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1)

- Quick Starter - TroyDocumento37 páginasQuick Starter - TroyBrlien AlAinda não há avaliações

- From War Heroes To Sporting Heroes PDFDocumento6 páginasFrom War Heroes To Sporting Heroes PDFJohn1 SteffAinda não há avaliações

- The Homeric Hero RevisedDocumento2 páginasThe Homeric Hero Revisedapi-309870284Ainda não há avaliações

- Swift Lyric - Visions - Epic - Combat - Spectacle - War - Archaic - Personal - SongDocumento17 páginasSwift Lyric - Visions - Epic - Combat - Spectacle - War - Archaic - Personal - SongSofía IrinaAinda não há avaliações

- Contest in Western DramaDocumento1 páginaContest in Western DramaDenise NajmanovichAinda não há avaliações

- Race in Armor Race With Shields The Orig PDFDocumento23 páginasRace in Armor Race With Shields The Orig PDFVoislavAinda não há avaliações

- Iliad Common Essay QuestionsDocumento8 páginasIliad Common Essay QuestionsJohn Kenneath SalcedoAinda não há avaliações

- Greek Culture EssayDocumento4 páginasGreek Culture EssayStar AragonAinda não há avaliações

- Fair and Foul Play in the Funeral Games of the IliadDocumento10 páginasFair and Foul Play in the Funeral Games of the IliadJohn SteffAinda não há avaliações

- The Pursuit of Honor and Glory in Homer's Epic Poem The IliadDocumento4 páginasThe Pursuit of Honor and Glory in Homer's Epic Poem The IliadJay Barrera100% (1)

- Odyssey: Form The Foundation ofDocumento6 páginasOdyssey: Form The Foundation ofArenz Rubi Tolentino IglesiasAinda não há avaliações

- Clashes of The Individual and The Individual As The Army. The Obvious Examples Are AchillesDocumento2 páginasClashes of The Individual and The Individual As The Army. The Obvious Examples Are AchillesLogan DwyerAinda não há avaliações

- Jenna Peon HUM 220 09/30/2012Documento4 páginasJenna Peon HUM 220 09/30/2012jenna_peon8046Ainda não há avaliações

- The Fight With Death by The Hector in The IliadDocumento2 páginasThe Fight With Death by The Hector in The Iliadajaweria51Ainda não há avaliações

- Honour Thy Ancestors: Deathwatch RelicsDocumento2 páginasHonour Thy Ancestors: Deathwatch Relicsfleabag8194Ainda não há avaliações

- The Iliad by Homer The Epic Poem.Documento4 páginasThe Iliad by Homer The Epic Poem.cornejababylynneAinda não há avaliações

- Thomas Conlan - The Culture of Force & Farce, 14th Century Japanese Warfare (1999)Documento23 páginasThomas Conlan - The Culture of Force & Farce, 14th Century Japanese Warfare (1999)Thomas JohnsonAinda não há avaliações

- verweij2007_CititDocumento13 páginasverweij2007_CititproiectepsihologiceAinda não há avaliações

- Achilles or Hector?: Johnny HalliburtonDocumento6 páginasAchilles or Hector?: Johnny HalliburtonjohnnyAinda não há avaliações

- 2543 Journal SampleDocumento2 páginas2543 Journal SampleZyzel SoonAinda não há avaliações

- The World of Wrestling by Roland BarthesDocumento4 páginasThe World of Wrestling by Roland BarthesSuvratha JohnAinda não há avaliações

- 14 Years Old Boy's EssayDocumento1 página14 Years Old Boy's EssayarmidaAinda não há avaliações

- IliadDocumento2 páginasIliadAura GaheraAinda não há avaliações

- The Epic Features of The IliadDocumento4 páginasThe Epic Features of The IliadmimAinda não há avaliações

- Duh PobedeDocumento13 páginasDuh PobedeGoca JarakovicAinda não há avaliações

- G. B. Shaw's War Antipathy in Arms and The Man and Major BarbaraDocumento7 páginasG. B. Shaw's War Antipathy in Arms and The Man and Major BarbaraIJELS Research JournalAinda não há avaliações

- Achilles vs Hector: Exploring the True Heroes of Homer's IliadDocumento9 páginasAchilles vs Hector: Exploring the True Heroes of Homer's IliadNatasha Marsalli100% (1)

- Cla 135 Term PaperDocumento7 páginasCla 135 Term Paperapi-302419304Ainda não há avaliações

- The World of WrestlingDocumento3 páginasThe World of WrestlingZyzz BirdAinda não há avaliações

- An Epic Poem About The Trojan War, AnalysisDocumento3 páginasAn Epic Poem About The Trojan War, AnalysisAngel O Cordoba RromAinda não há avaliações

- Barthes 1957 The World of Wrestling, in Mythologies PDFDocumento4 páginasBarthes 1957 The World of Wrestling, in Mythologies PDFJesse StockerAinda não há avaliações

- Nagy 24 Hours, ReviewDocumento4 páginasNagy 24 Hours, ReviewRasmus TvergaardAinda não há avaliações

- Roman Gladiator GamesDocumento2 páginasRoman Gladiator GamesAnonymous ToHeyBoEbX100% (1)

- Reflections on Homer's Iliad and Odyssey - Insight into these epic tales of war, heroism, and adventureDocumento16 páginasReflections on Homer's Iliad and Odyssey - Insight into these epic tales of war, heroism, and adventureCyrus Buladaco GinosAinda não há avaliações

- Patchwork 2021 Issue 7 BockajDocumento13 páginasPatchwork 2021 Issue 7 BockajNećeš SadaAinda não há avaliações

- The Progression of "Heroes" in Literature Since Classical TimesDocumento2 páginasThe Progression of "Heroes" in Literature Since Classical TimesRachael MachadoAinda não há avaliações

- Analysis of IliadDocumento3 páginasAnalysis of IliadMinKyong KimAinda não há avaliações

- War and PlayDocumento11 páginasWar and PlayLloyd AmoahAinda não há avaliações

- Battle: Understanding Conflict from Hastings to HelmandNo EverandBattle: Understanding Conflict from Hastings to HelmandAinda não há avaliações

- Hector's Struggle with Cognitive Dissonance in Homer's IliadDocumento8 páginasHector's Struggle with Cognitive Dissonance in Homer's IliadAman Alvi100% (1)

- Wright 2007Documento21 páginasWright 2007F1 pdfAinda não há avaliações

- Martial's Gladiator Poem AnalyzedDocumento10 páginasMartial's Gladiator Poem Analyzedreham el kassasAinda não há avaliações

- Sophocles MoralityDocumento17 páginasSophocles MoralityJames GiraldoAinda não há avaliações

- ChebbyDocumento2 páginasChebbyKanad Prajna DasAinda não há avaliações

- Time and Arete in HomerDocumento16 páginasTime and Arete in HomerJulia ViglioccoAinda não há avaliações

- Eshekova L EssayDocumento4 páginasEshekova L Essaynurhan.ibraimovAinda não há avaliações

- 0 IntroductionDocumento7 páginas0 IntroductionAC16Ainda não há avaliações

- 30 Marker Warfare IliadDocumento3 páginas30 Marker Warfare Iliadcara chandlerAinda não há avaliações

- Zeph Babel 3Documento98 páginasZeph Babel 3John SteffAinda não há avaliações

- New Foundations in The History of AstronomyDocumento5 páginasNew Foundations in The History of AstronomyJohn SteffAinda não há avaliações

- Homeric Pun From Abu SimbelDocumento4 páginasHomeric Pun From Abu SimbelJohn SteffAinda não há avaliações

- IslamDocumento225 páginasIslamfreewakedAinda não há avaliações

- Planetary Distances As A Test For The Copernican TheoryDocumento4 páginasPlanetary Distances As A Test For The Copernican TheoryJohn SteffAinda não há avaliações

- Correspondence Truth and Scientific RealismDocumento21 páginasCorrespondence Truth and Scientific RealismJohn SteffAinda não há avaliações

- New Customer? Start HereDocumento2 páginasNew Customer? Start HereJohn SteffAinda não há avaliações

- ΑΡΙΣΤΑΡΧΟΣ ΚΑΙ ΗΛΙΟΚΕΝΤΡΙΣΜΟΣ 2Documento0 páginaΑΡΙΣΤΑΡΧΟΣ ΚΑΙ ΗΛΙΟΚΕΝΤΡΙΣΜΟΣ 2John SteffAinda não há avaliações

- Aristarchus and Copernicus-PetrakisDocumento3 páginasAristarchus and Copernicus-PetrakisJohn SteffAinda não há avaliações

- Methodological Rules, Rationality, and TruthDocumento11 páginasMethodological Rules, Rationality, and TruthJohn SteffAinda não há avaliações

- To Believe in BeliefDocumento19 páginasTo Believe in BeliefJohn SteffAinda não há avaliações

- Kitrom - History of European IdeasDocumento16 páginasKitrom - History of European IdeasJohn SteffAinda não há avaliações

- Structural Realism, ScientificDocumento23 páginasStructural Realism, ScientificJohn SteffAinda não há avaliações

- From Rum Millet To Greek NationDocumento38 páginasFrom Rum Millet To Greek NationJohn SteffAinda não há avaliações

- Roman Slave LawDocumento19 páginasRoman Slave LawJohn SteffAinda não há avaliações

- Vetus Latina EstherDocumento3 páginasVetus Latina EstherJohn SteffAinda não há avaliações

- SkouroliakouDocumento42 páginasSkouroliakouJohn SteffAinda não há avaliações

- The Bible Book of LamentationsDocumento3 páginasThe Bible Book of LamentationsJohn SteffAinda não há avaliações

- Inclusion and Exclusion in The CosmopolisDocumento11 páginasInclusion and Exclusion in The CosmopolisJohn SteffAinda não há avaliações

- Ancient Measurements of The Sun and MoonDocumento10 páginasAncient Measurements of The Sun and MoonJohn SteffAinda não há avaliações

- Realism and InevitabilityDocumento10 páginasRealism and InevitabilityJohn SteffAinda não há avaliações

- Ascetic ExegeteDocumento6 páginasAscetic ExegeteJohn SteffAinda não há avaliações

- Metaxas Argentina 3Documento10 páginasMetaxas Argentina 3John SteffAinda não há avaliações

- Pedrick SUPPLICATION PDFDocumento17 páginasPedrick SUPPLICATION PDFJulián Bértola100% (1)

- World Literature Reviewer 1Documento8 páginasWorld Literature Reviewer 1Irish CruzadaAinda não há avaliações

- The Progression of "Heroes" in Literature Since Classical TimesDocumento2 páginasThe Progression of "Heroes" in Literature Since Classical TimesRachael MachadoAinda não há avaliações

- Comparison of Book Iliad and The Film TroyDocumento3 páginasComparison of Book Iliad and The Film Troydawn14100% (4)

- Ancient Greek Literature: From Homer to SapphoDocumento39 páginasAncient Greek Literature: From Homer to SapphoMar ClarkAinda não há avaliações

- Academic Reading TEAMDocumento24 páginasAcademic Reading TEAMBibi LalisaAinda não há avaliações

- The Sacrificial Victor in AeneidDocumento277 páginasThe Sacrificial Victor in AeneidMladen Toković100% (2)

- The Embassy and The Duals of Iliad PDFDocumento14 páginasThe Embassy and The Duals of Iliad PDFAlvah GoldbookAinda não há avaliações

- Homeric StyleDocumento13 páginasHomeric StyleSunny FerdaushAinda não há avaliações

- Internecine Iliad, Othering Odyssey: Ancient Greek Epics Explore War & IdentityDocumento3 páginasInternecine Iliad, Othering Odyssey: Ancient Greek Epics Explore War & IdentityKay BonaventeAinda não há avaliações

- The IliadDocumento33 páginasThe IliadAndre Maurice ReyAinda não há avaliações

- Iliad Books 21 - 24: The Last Stand Ian, Nicky, Alex, and AdinaDocumento24 páginasIliad Books 21 - 24: The Last Stand Ian, Nicky, Alex, and AdinaIan ConnollyAinda não há avaliações

- Helen's Necklace Sparks a WarDocumento10 páginasHelen's Necklace Sparks a WarRamisa NawarAinda não há avaliações

- LanglitDocumento8 páginasLanglitSeroma LGAinda não há avaliações

- Herodotus' Histories: A Personal Odyssey Through Four Decades of ScholarshipDocumento13 páginasHerodotus' Histories: A Personal Odyssey Through Four Decades of ScholarshipAnonymous Jj8TqcVDTy100% (1)

- Achilles and Patroclus Are LoversDocumento5 páginasAchilles and Patroclus Are LoversAna Carmela Salazar LaraAinda não há avaliações

- Sophocles MoralityDocumento17 páginasSophocles MoralityJames GiraldoAinda não há avaliações

- How Leaders Respond to Divided Societies in Invictus and RansomDocumento3 páginasHow Leaders Respond to Divided Societies in Invictus and RansomLevi LiuAinda não há avaliações

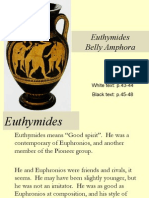

- EuthymidesDocumento25 páginasEuthymidessudsnzAinda não há avaliações

- The Placement of 'Book Divisions' in The IliadDocumento14 páginasThe Placement of 'Book Divisions' in The IliadanimumbraAinda não há avaliações

- MemnonDocumento23 páginasMemnonStavros GirgenisAinda não há avaliações

- The Adventures of Ulysses - LambDocumento183 páginasThe Adventures of Ulysses - LambJose Miguel Lizano SeguraAinda não há avaliações

- Reflection - TroyDocumento3 páginasReflection - TroyEnaid Ronquillo100% (1)