Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Tan Chay Heng v. West Coast Life

Enviado por

Sean GalvezDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Tan Chay Heng v. West Coast Life

Enviado por

Sean GalvezDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Tan Chay v.

West Coast Life Insurance 51 Phil 80 1927 SUMMARY: Insurance Law Representation Rescission of an Insurance Contract Whether or not Section 47 is applicable in the case at bar. HELD: No. West Coast was not seeking for the rescission of the insurance contract. In fact, West Coast avers that there was no insurance contract at all because the temporary insurance issued in favor of Tan Ceang was null and void. For West Coast, it was void ab initio because of the fraudulent circumstances attending to it. Therefore, it cannot be subject to rescission. The Supreme Court however remanded the case to the lower court to determine the material allegations made by West Coast against Tan Chay Heng Digest 1 Tan Chay Heng v. West Coast Life 51 Phil 80 Facts: In 1926, Tan Chay Heng sued West Coast on the policy allegedly issued to his uncle, Tan Caeng who died in 1925. He was the sole beneficiary thereof. West Coast refused on the ground that the policy was obtained by Tan Caeng with the help of agents Go Chuilian, Francisco Sanchez and Dr. Locsin of West Coast. West Coast said that it was made to appear that Tan Caeng was single, a merchant, health and not a drug user, when in fact he was married, a laborer, suffering form tuberculosis and addicted to drugs. West Coast now denies liability based on these misrepresentations. Tan Chay contends that West Coast may not rescind the contract because an action for performance has already been filed. Trial court found for Tan Chay holding that an insurer cannot avoid a policy which has been procured by fraud unless he brings an action to rescind it before he is sued thereon. Issue: WON West Coasts action for rescission is therefore barred by the collection suit filed by Tan Chay. Held: NO. Precisely, the defense of West Cast was that through fraud in its execution, the policy is void ab initio, and therefore, no valid contract was ever made. Its action then cannot be fore rescission because an action to rescind is founded upon and presupposes the existence of the contract. Hence, West Coasts defense is not barred by Sec. 47. In the instant case, it will be noted that even in its prayer, the defendant does not seek to have the alleged insurance contract rescinded. It denies that it ever made any contract of insurance on the life of Tan Caeng, or that any such a contract ever existed, and that is the question which it seeks to have litigated by its special defense. In the very nature of things, if the defendant never made or entered into the contract in question, there is no contract to rescind, and, hence, section 47 upon which the lower court based its decision in sustaining the demurrer does not apply. As stated, an action to rescind a contract is founded upon and presupposes the existence of the contract which is sought to be rescinded. If all of the material matters set forth and alleged in the defendant's special plea are true, there was no valid contract of insurance, for the simple reason that the minds of the parties never met and never agreed upon the terms and conditions of the contract. We are clearly of the opinion that, if such matters are known to exist by a preponderance of the evidence, they would constitute a valid defense to plaintiff's cause of action. Upon the question as to whether or not they are or are not true, we do not at this time have or express any opinion, but we are clear that section 47 does not apply to the allegations made in the answer, and that the trial court erred in sustaining the demurrer. RATIO: The plaintiff contends that section 47 of the Insurance Act should be applied, and that when so applied, the company is barred and estopped to plead the matters alleged in its special defense. That section states: Whenever a right to rescind a contract of insurance is given to the insurer by any provision of this chapter, such right must be exercised previous to the commencement of an action on the contract. The defendant contends that section 47 does not apply to this special defense. If in legal effect defendant's special defense is in the nature of an act to rescind "a contract of insurance," then such right must be exercised prior to an action enforce the contract. Defendant denied that if ever issued the policy in question. The word "rescind" has a well defined legal meaning, and as applied to contracts, it presupposes the existence of a contract to rescind. The rescission relates only to the unfulfilled part, and not to the entire agreement, making the party rescinding liable on notes executed pursuant to the contract which matured before the rescission. The rescission is the unmaking of a contract, requiring the same concurrence of wills as that which made it, and nothing short of this will suffice. After a contract has been broken, whether by an inability to perform it, or by rescinding against right or otherwise, the party not in fault may sue the other for the damages suffered, or, if the parties can be placed in status quo, he may, should he prefer, return what he has received and recover in a suit value of what he has paid or done. The latter remedy is termed "rescission." In the instant case, the defendant does not seek to have the alleged insurance contract rescinded. It only denies that it ever made any contract of insurance on the life of Tan Ceang or that any such a contract ever existed. If the defendant never made or entered into the contract

Tan Chay v. West Coast Life Insurance 51 Phil 80 1927 in question, there is no contract to rescind, and, hence, section 47 doesnt apply. As s tated, an action to rescind a contract is founded upon and presupposes the existence of the contract which is sought to be rescinded. If all of the material matters set forth and alleged in the defendant's special plea are true, there was no valid contract of insurance, for the simple reason that the minds of the parties never met and never agreed upon the terms and conditions of the contract. If such matters are known to exist by a preponderance of the evidence, they would constitute a valid defense to plaintiff's cause of action. Upon the question as to whether or not they or are not true, the court couldnt say, but they were sure that section 47 does not apply to the allegations made in the answer.

DIGEST FACTS: STATEMENT OF PETITIONER Plaintiff alleges that he is of age and a resident of Bacolod, Occidental Negros; that the defendant is a foreign insurance corporation duly organized by the laws of the Philippines to engage in the insurance business, its main office of which is in the City of Manila; that in the month of April, 1925, on his application the defendant accepted and approved a life insurance policy of for the sum of P10,000 in which the plaintiff was the sole beneficiary; that the policy was issued upon the payment by the said Tan Ceang of the first year's premium amounting to P936; that in and by its terms, the defendant agreed to pay the plaintiff as beneficiary the amount of the policy upon the receipt of the proofs of the death of the insured while the policy was in force; that without any premium being due or unpaid, Tan Ceang died on May 10, 1925; that in June, 1925, plaintiff submitted the proofs of the death of Tan Ceang with a claim for the payment of the policy which the defendant refused to pay, for which he prays for a corresponding judgment, with legal interest from the date of the policy, and costs. DEFENSE OF INSURER SPECIAL DEFENSE That the insurance policy on the life of Tan Ceang, upon which plaintiff's action is based, was obtained by the plaintiff in confabulation with one Go Chulian, of Bacolod, Negros Occidental; Francisco Sanchez of the same place; and Dr. V. S. Locsin, of La Carlota, Negros Occidental, thru fraud and deceit perpetrated against this defendant in the following manner, to wit: 1. That on or about the 22d day of February, 1925, in the municipality of Pulupandan, Occidental Negros, the present plaintiff and the said Go Chulian, Francisco Sanchez and Dr., V. S. Locsin, conspiring and confederating together for the purpose of defrauding and cheating the defendant in the sum of P10,000, caused one Tan Caeng to sign an application for insurance with the defendant in the sum of P10,000, in which application it was falsely represented to the defendant that the said Tan Ceang was single and was a merchant, and that the plaintiff Tan Chai Heng, the beneficiary, was his nephew, whereas in truth and in fact and as the plaintiff and his said coconspirators well knew, the said Tan Ceang was not single but was legally married to Marcelina Patalita with whom he had several children; and that he was not a merchant but was a mere employee of another Chinaman by the name of Tan Quina from whom he received only a meager salary, and that the present plaintiff was not a nephew of the said Tan Ceang. 2. That on said date, February 22, 1925, the said Tan Ceang was seriously ill, suffering from pulmonary tuberculosis of about three years' duration, which illness was incurable and was well known to the plaintiff and his said coconspirators. 3. That on or about the same date, February 22, 1925, the said Dr. V. S. Locsin, in his capacity as medical examiner for the defendant insurance company, pursuant to the conspiracy above mentioned, prepared and falsified the necessary medical certificate, in which it was made to appear, among other things, that the said Tan Ceang had never used morphine, cocaine or any other drug; that he was then in good health and had never consulted any physician; that he had never spit blood; and that there was no sign of either present or past disease of his lungs; whereas in truth and in fact, as the plaintiff and his said coconspirators well knew, the said Tan Ceang was addicted to morphine, cocaine, and opium and had been convicted and imprisoned therefor, and was then, and for about three year prior thereto had been suffering from pulmonary tuberculosis. 4. That on or about the same date, to wit, February 22, 1925, the plaintiff and his said coconspirators, pursuant to the conspiracy above mentioned, cause a confidential report to the defendant insurance company to be signed by one V. Sy Yock Kian, who was an employee of Go Chulian, in which confidential report, among other things, it was falsely represented to the defendant insurance company that the said Tan Ceang was worth about P40,000, had an annual income of from eight to ten thousand pesos net, had the appearance of good health, and never had tuberculosis; that the plaintiff and his said coconspirators well knew that said representations were false; and that they were made for the purpose of deceiving the defendant and inducing it to accept the said application for insurance. 5. That after the said application for insurance, medical certificate and confidential report had been prepared and falsified, as aforesaid, the plaintiff and his said coconspirators caused the same to be forwarded to the defendant at its office in Manila, the medical certificate thru the said Dr. V. S. Locsin as medical examiner, and said application for insurance and confidential report thru the said Francisco Sanchez in his capacity as one of the agents of the defendant insurance company in the Province of Occidental Negros; that the defendant, believing that the representations made in said document were true, and relying thereon, provisionally accepted

Tan Chay v. West Coast Life Insurance 51 Phil 80 1927 the said application for insurance on the life of Tan Ceang in the sum of P10,000 and issued a temporary policy pending the final approval or disapproval of said application by defendant's home-office in San Francisco, California, where in case of approval a permanent policy was to be issued; that such permanent policy was never delivered to the plaintiff because defendant discovered the fraud before its delivery. 6. That the first agreed annual premium on the insurance in question of P936.50 not having been paid within sixty (60) days after the date of the supposed medical examination of the applicant as required by the regulations of the defendant insurance company, of which regulations the said Francisco Sanchez as agent of the defendant had knowledge, the plaintiff and his said coconspirators in order to secure the delivery to them of said temporary policy, and in accordance with said regulations of the defendant company, caused the said Tan Ceang on April 10, 1925 to sign the following document:

WEST COAST LIFE INSURANCE COMPANY SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA HEALTH CERTIFICATE FOR RE-INSTATEMENT I herewith request the West Coast Life Insurance Company to re-instate Policy No. ............................. issued by it upon my life, the first unpaid premium on which became due .............................., 19................ I certify and state that I am now in good and sound health, that since the date of my examination under the application on which said policy was written, I have had no injury, sickness, impairment of health or symptom thereof, and that since said date I have neither consulted a physician nor made any application for life insurance that has not been granted in exact kind and amount applied for, except: NADA (State fully all exceptions to all above statements. If no exceptions insert "NONE.") I agree that, if said policy re-instated, it shall be only on condition of the truth of the above statements and such re-instatement shall not operate as a waiver on the part of said Company of its right to refuse to accept any future overdue premiums or installments thereof. Witness: (Sgd.) TAN CHAI HENG TAN CAENG Signature of Applicant. "Dated at Palupandan on this 10 day of April, 1925." that the statements and representations contained in the application for reinstatement above set forth with regard to the health and physical condition of the said Tan Ceang were false and known to the plaintiff and his said coconspirators to be false; that the said temporary policy was delivered by defendant to the insured on April 10, 1925, in the belief that said statements and representations were true and in reliance thereon. 7. That on May 10, 1925, that is to say, two months and a half after the supposed medical examination above referred to, and exactly one month after the date of the health certificate for reinstatement above set forth, the said Tan Ceang died in Valladolid, Occidental Negros, of pulmonary tuberculosis, the same illnes from which suffering at the time it is supposed he was examined by Dr. V. S. Locsin, but that the plaintiff and his said coconspirators, pursuant to their conspiracy, caused the said Dr. V. S. Locsin to state falsely in the certificate of death that the said Tan Ceang had died of cerebral hemorrhage. II That the plaintiff Tan Chai Heng, on the dates herein-above mentioned, was, liked V. Sy Yock Kian who signed the confidential report above mentioned, an employee of the said Go Chulian; that the latter was the ringleader of a gang of malefactors, who, during, and for some years previous to the dates above mentioned, were engaged in the illicit enterprise of procuring fraudulent life insurances from the present defendant, similar to the one in question, and which enterprise was capitalized by him by furnishing the funds with which to pay the premium on said fraudulent insurance; that the said Go Chulian was the one who furnished the money with which to pay the first and only annual premium on the insurance here in question, amounting to P936.50; that the said Go Chulian, on August 28, 1926, was convicted by the Court of First Instance of the City of Manila, in criminal case No. 31425 of that court, of the crime of falsification of private documents in connection with an fraudulent insurance, similar to the present, committed against this defendant in the month of September, 1924; that in the same case the said Francisco Sanchez was one of the coaccused of the said Go Chulian but was discharged from the complaint, because he offered himself and was utilized as a state's witness; that there is another civil action now pending against Go Chulian and Sanchez in the Court of First Instance of Manila (civil case No. 28680), in which the present defendant is the plaintiff, for the recovery of the amounts of two insurance policies aggregating P19,000, fraudulently obtained by the said Go Chulian and Sanchez upon the lives of one Tan Deco, who was also suffering from and died of tuberculosis, and one Tan Anso, who was suffering from and died of beriberi. III

Tan Chay v. West Coast Life Insurance 51 Phil 80 1927 That by reason of all the facts above set forth, the temporary policy of insurance on the life of Tan Caeng for the sum of P10,000 upon which the present action is base is null and void. Wherefore, defendant prays that it be absolved from plaintiff's complaint, with costs against the plaintiff. To this special defense, the plaintiff, claiming that it was a cross-complaint, filed a general demurrer upon the ground that it does not state facts sufficient to constitute a cause of defense. After exhaustive arguments and on September 16, 1926, the court rendered the following decision: After considering the demurrer filed by the plaintiff to the special defense contained in the amended answer of the defendant, dated August 31, 1926, without prejudice to writing a more extensive decision, said demurrer is sustained, and the defendant is given a period of five days within which to amend its aforesaid answer. So ordered. To which the defendant duly excepted. As a result of the trial the general issues, the lower court rendered judgment for the plaintiff for P10,000, with legal interest from January 4, 1926, and costs, to which the defendant duly excepted and filed a motion for a new trial, which was overruled. On appeal the defendant assigns the following errors: The trial court erred 1. In sustaining plaintiff's demurrer to the special defense contained in defendant's amended answer. 2. In holding, in effect, that an insurer cannot avoid a policy which had been procured by fraud unless he brings an action to rescind it before he is sued thereon. 3. In rejecting all proofs offered by the defendant during the trial for the purpose of defeating plaintiff's fraudulent claim. 4. In not absolving the defendant from plaintiff's complaint. JOHNS, J.: It will thus be noted that the premium was paid on April 10, 1925, at which time the temporary policy was issued; that the plaintiff's action was commenced on January 4, 1926; that the original answer of the defendant, consisting of a general and specific denial, was filed on February 27, 1926; and that its amended answer was filed on August 31, 1926. Based upon those facts the plaintiff vigorously contended in the lower court and now contends in the court, that section 47 of the Insurance Act should be applied, and that when so applied, defendant is barred and estopped to plead and set forth the matters alleged in its special defense. That section is as follows: Whenever a right to rescind a contract of insurance is given to the insurer by any provision of this chapter, such right must be exercised previous to the commencement of an action on the contract. The defendant contended in the lower court and now contends in this court, that section 47 does not apply to the new matters alleged in the special defense. If in legal effect defendant's special defense is in the nature of an act to rescind "a contract of insurance," then such right must be exercised prior to an action enforce the contract. That is the real question involved in this appeal. Defendant's original answer was a general and specific denial. In other words, it specifically denied that if ever issued the policy in question, or that it ever agreed with Tan Ceang in the even of his death to pay P10,000 to the plaintiff or any one else. In its amended answer the defendant again makes a general and specific denial, and alleges the reasons, the specific facts, and the reasons why it never made or entered into the contract alleged in the complaint, and based upon those alleged facts, defendant contends that it never did enter into any contract of insurance on the life of Tan Caeng. The word "rescind" has a well defined legal meaning, and as applied to contracts, it presupposes the existence of a contract to rescind. In the instant case, it will be noted that even in its prayer, the defendant does not seek to have the alleged insurance contract rescinded. It denies that it ever made any contract of insurance on the life of Tan Ceang or that any such a contract ever existed, and that is the question which it seeks to have litigated by its special defense. In the very nature of things, if the defendant never made or entered into the contract in question, there is no contract to rescind, and, hence, section 47 upon which the lower based its decision in sustaining the demurrer does not apply. As stated, an action to rescind a contract is founded upon and presupposes the existence of the contract which is sought to be rescinded. If all of the material matters set forth and alleged in the defendant's special plea are true, there was no valid contract of insurance, for the simple reason that the minds of the parties never met and never agreed upon the terms and conditions of the contract. We are clearly of the opinion that, if such matters are known to exist by a preponderance of the evidence, they would constitute a valid defense to plaintiff's cause of action. Upon the question as to whether or not they or are not true, we do not at this time have or express any opinion, but we are clear that section 47 does not apply to the allegations made in the answer, and that the trial court erred in sustaining the demurrer. The judgment of the lower court is reversed and the case is remanded for such other and further proceedings as are not inconsistent with this opinion, with costs against the plaintiff. So ordered.

Você também pode gostar

- Development Insurance Corp. v. IACDocumento1 páginaDevelopment Insurance Corp. v. IAClealdeosaAinda não há avaliações

- Edillon v. Manila Bankers Life Insurance Corp.Documento2 páginasEdillon v. Manila Bankers Life Insurance Corp.Jellyn100% (1)

- Planters Product Inc vs. CADocumento2 páginasPlanters Product Inc vs. CAAlexPamintuanAbitanAinda não há avaliações

- Guingon vs. Del MonteDocumento1 páginaGuingon vs. Del MonteCharles Atienza100% (1)

- 135 Capalla V Comelec - EnriquezDocumento4 páginas135 Capalla V Comelec - EnriquezCedric EnriquezAinda não há avaliações

- Great Pacific Life Vs CA - DILOY, BeaDocumento2 páginasGreat Pacific Life Vs CA - DILOY, BeaAddy GuinalAinda não há avaliações

- PhilHome Ass. Corp. vs. CADocumento15 páginasPhilHome Ass. Corp. vs. CAMark De JesusAinda não há avaliações

- Bachrach v. British American InsuranceDocumento3 páginasBachrach v. British American InsuranceDominique PobeAinda não há avaliações

- 11 21Documento34 páginas11 21Anonymous fnlSh4KHIgAinda não há avaliações

- Misamis Lumber V Capital InsuranceDocumento1 páginaMisamis Lumber V Capital InsurancemendozaimeeAinda não há avaliações

- DSR Senator LinesDocumento2 páginasDSR Senator LinesMa RaAinda não há avaliações

- Insurance - Week 4Documento8 páginasInsurance - Week 4Stephanie GriarAinda não há avaliações

- Prudential Guarantee and Assurance Inc., vs. Trans-Asia Shipping Lines Inc, G.R. No. 151890 June 20, 2006 (Full Text and Digest)Documento14 páginasPrudential Guarantee and Assurance Inc., vs. Trans-Asia Shipping Lines Inc, G.R. No. 151890 June 20, 2006 (Full Text and Digest)RhoddickMagrataAinda não há avaliações

- Ang Giok Chip Insurance DigestDocumento2 páginasAng Giok Chip Insurance DigestJul A.0% (1)

- Francisco Jarque vs. Smith Bell & Co.Documento2 páginasFrancisco Jarque vs. Smith Bell & Co.elaine bercenioAinda não há avaliações

- Insurance DigestDocumento16 páginasInsurance DigestDianne MendozaAinda não há avaliações

- TAN Vs CADocumento3 páginasTAN Vs CAMariz GalangAinda não há avaliações

- Spouses CHA v. CADocumento3 páginasSpouses CHA v. CAAnonChie100% (1)

- Mayer Steel Pipe Corporation Vs PDFDocumento1 páginaMayer Steel Pipe Corporation Vs PDFOscar E ValeroAinda não há avaliações

- Lu vs. IAC G.R.70149, Jan. 30, 1989Documento6 páginasLu vs. IAC G.R.70149, Jan. 30, 1989Jiezel BesinAinda não há avaliações

- Sps. Viloria v. Continental AirlinesDocumento2 páginasSps. Viloria v. Continental AirlinesMae Anne SandovalAinda não há avaliações

- Enriquez vs. Sun Life Assurance Company of CanadaDocumento2 páginasEnriquez vs. Sun Life Assurance Company of CanadaEuneun Bustamante100% (1)

- Fortune Insurance and Surety Co. Case DigestDocumento2 páginasFortune Insurance and Surety Co. Case DigestScarlette Joy CooperaAinda não há avaliações

- Calanoc v. CADocumento2 páginasCalanoc v. CARiena MaeAinda não há avaliações

- 14 Lalican v. Insular Life Assurance Co.Documento3 páginas14 Lalican v. Insular Life Assurance Co.Patricia IgnacioAinda não há avaliações

- UNITED POLYRESINS INC v. PINUELADocumento1 páginaUNITED POLYRESINS INC v. PINUELAAfricaEdnaAinda não há avaliações

- Perils of The Sea Perils of The ShipDocumento15 páginasPerils of The Sea Perils of The ShipEd Karell GamboaAinda não há avaliações

- Sun Insurance V CADocumento1 páginaSun Insurance V CAKristina KarenAinda não há avaliações

- Insular Life Vs Ebrado DigestedDocumento1 páginaInsular Life Vs Ebrado DigestedVinz G. VizAinda não há avaliações

- Ang Giok Chip Vs SpringfieldDocumento3 páginasAng Giok Chip Vs SpringfieldimangandaAinda não há avaliações

- Fieldmen's Insurance Co v. Asian SuretyDocumento1 páginaFieldmen's Insurance Co v. Asian SuretyAfricaEdnaAinda não há avaliações

- Great Pacific Life vs. CA Case DigestDocumento3 páginasGreat Pacific Life vs. CA Case DigestLiana Acuba100% (1)

- 300-BDO v. Republic of The Philippines G.R. No. 198756 January 13, 2015Documento24 páginas300-BDO v. Republic of The Philippines G.R. No. 198756 January 13, 2015Jopan SJAinda não há avaliações

- Artex Development Co. Vs Wellington Insurance Co.Documento1 páginaArtex Development Co. Vs Wellington Insurance Co.thornapple25Ainda não há avaliações

- South Sea Surety v. CADocumento1 páginaSouth Sea Surety v. CAAlec VenturaAinda não há avaliações

- 50 - Pioneer Insurance vs. Olivia YapDocumento1 página50 - Pioneer Insurance vs. Olivia YapN.SantosAinda não há avaliações

- 082 UCPB General Insurance Co, Inc. v. Masagana Telmart Inc.Documento2 páginas082 UCPB General Insurance Co, Inc. v. Masagana Telmart Inc.keith105Ainda não há avaliações

- APL v. KlepperDocumento3 páginasAPL v. KlepperJen T. TuazonAinda não há avaliações

- Londres vs. National Life InsuranceDocumento2 páginasLondres vs. National Life InsuranceAnny YanongAinda não há avaliações

- Noda v. Cruz-Arnaldo DigestDocumento2 páginasNoda v. Cruz-Arnaldo DigestFrancis GuinooAinda não há avaliações

- Bayan V ZamoraDocumento30 páginasBayan V ZamoramiemielawAinda não há avaliações

- Villanueva v. Oro - Insurance ProceedsDocumento4 páginasVillanueva v. Oro - Insurance ProceedsLord AumarAinda não há avaliações

- Security Bank v. CuencaDocumento2 páginasSecurity Bank v. Cuencad2015memberAinda não há avaliações

- Argente v. West Coast Life InsuranceDocumento2 páginasArgente v. West Coast Life InsuranceMan2x Salomon100% (1)

- Case No. 32 - Padura V Baldovino - DigestDocumento1 páginaCase No. 32 - Padura V Baldovino - DigestRossette AnaAinda não há avaliações

- Sun Insurance Office, Ltd. vs. Court of AppealsDocumento6 páginasSun Insurance Office, Ltd. vs. Court of AppealsJaja Ordinario Quiachon-AbarcaAinda não há avaliações

- Gulf Resorts Vs Philippine CharterDocumento2 páginasGulf Resorts Vs Philippine CharterAnonymous XsaqDYDAinda não há avaliações

- Republic Vs Del MonteDocumento2 páginasRepublic Vs Del MonteEmmanuel Ortega100% (1)

- Palilieo v. Cosio - Insurance Proceeds 97 PHIL 919 FactsDocumento5 páginasPalilieo v. Cosio - Insurance Proceeds 97 PHIL 919 Factsdeuce scriAinda não há avaliações

- Young Vs Midland Textile Insurance CoDocumento2 páginasYoung Vs Midland Textile Insurance CoMykee NavalAinda não há avaliações

- 6 E.E. Elser, Inc. Vs CA, G.R. No. L-6517 PDFDocumento8 páginas6 E.E. Elser, Inc. Vs CA, G.R. No. L-6517 PDFpa0l0sAinda não há avaliações

- Gaisano vs. Development Insurance and Surety CorporationDocumento12 páginasGaisano vs. Development Insurance and Surety CorporationAaron CarinoAinda não há avaliações

- White Gold Marine Services, Inc. vs. Pioneer Insurance and Surety Corporation DigestDocumento2 páginasWhite Gold Marine Services, Inc. vs. Pioneer Insurance and Surety Corporation DigestAnnaAinda não há avaliações

- Makati Tuscany vs. CADocumento1 páginaMakati Tuscany vs. CAOscar E ValeroAinda não há avaliações

- White Gold vs. PioneerDocumento2 páginasWhite Gold vs. PioneerKokoAinda não há avaliações

- Biagtan vs. Insular LifeDocumento1 páginaBiagtan vs. Insular Lifeerxha ladoAinda não há avaliações

- 62 - DBP Pool of Accredited Insurance Companies v. Radio Mindanao Network, Inc.Documento3 páginas62 - DBP Pool of Accredited Insurance Companies v. Radio Mindanao Network, Inc.Katrina Janine Cabanos-ArceloAinda não há avaliações

- Insular Life Assurance CoDocumento1 páginaInsular Life Assurance CoLDAinda não há avaliações

- Tan Chay Heng v. The West Coast Life Insurance CompanyDocumento3 páginasTan Chay Heng v. The West Coast Life Insurance CompanyMark Evan GarciaAinda não há avaliações

- 073 Tan Chay Heng v. West CoastDocumento3 páginas073 Tan Chay Heng v. West CoastJovelan V. EscañoAinda não há avaliações

- Adiong V ComelecDocumento3 páginasAdiong V ComelecSean GalvezAinda não há avaliações

- in Re - Testate Estate of The Late Gregorio VenturaDocumento2 páginasin Re - Testate Estate of The Late Gregorio VenturaSean GalvezAinda não há avaliações

- Adiong v. ComelecDocumento2 páginasAdiong v. ComelecSean GalvezAinda não há avaliações

- Delfin Tan v. BeneliraoDocumento5 páginasDelfin Tan v. BeneliraoSean GalvezAinda não há avaliações

- Heirs of Magdaleno Ypon v. RicaforteDocumento2 páginasHeirs of Magdaleno Ypon v. RicaforteSean Galvez100% (1)

- Suntay v. SuntayDocumento2 páginasSuntay v. SuntaySean GalvezAinda não há avaliações

- Dela Cruz v. Dela Cruz PDFDocumento3 páginasDela Cruz v. Dela Cruz PDFSean GalvezAinda não há avaliações

- Vargas v. ChuaDocumento2 páginasVargas v. ChuaSean Galvez100% (1)

- Pascual v. CA 2003Documento2 páginasPascual v. CA 2003Sean GalvezAinda não há avaliações

- Benny Sampilo and Honorato Salacup v. CADocumento3 páginasBenny Sampilo and Honorato Salacup v. CASean GalvezAinda não há avaliações

- Franiela v. BanayadDocumento1 páginaFraniela v. BanayadSean GalvezAinda não há avaliações

- In Re Palaganas v. PalaganasDocumento2 páginasIn Re Palaganas v. PalaganasSean GalvezAinda não há avaliações

- Rubi V Prov of MindoroDocumento3 páginasRubi V Prov of MindoroSean GalvezAinda não há avaliações

- People v. GesmundoDocumento3 páginasPeople v. GesmundoSean GalvezAinda não há avaliações

- Samson V DawayDocumento3 páginasSamson V DawaySean GalvezAinda não há avaliações

- Creser v. CADocumento2 páginasCreser v. CASean GalvezAinda não há avaliações

- De Los Santos V MontesaDocumento3 páginasDe Los Santos V MontesaSean GalvezAinda não há avaliações

- Nuguid v. Nuguid DDocumento2 páginasNuguid v. Nuguid DSean GalvezAinda não há avaliações

- Samson V CabanosDocumento3 páginasSamson V CabanosSean GalvezAinda não há avaliações

- In The Matter For The Declaration of William GueDocumento2 páginasIn The Matter For The Declaration of William GueSean GalvezAinda não há avaliações

- De Guzman V Angeles PDFDocumento3 páginasDe Guzman V Angeles PDFSean GalvezAinda não há avaliações

- Guzman V NuDocumento3 páginasGuzman V NuSean GalvezAinda não há avaliações

- Ermita Motel Association V Mayor of ManilaDocumento5 páginasErmita Motel Association V Mayor of ManilaSean GalvezAinda não há avaliações

- People V CayananDocumento1 páginaPeople V CayananSean GalvezAinda não há avaliações

- Tabuena v. SandiganabayanDocumento3 páginasTabuena v. SandiganabayanSean GalvezAinda não há avaliações

- Primer On Business Judgment RuleDocumento6 páginasPrimer On Business Judgment RuleVala Srihitha RaoAinda não há avaliações

- Cri 010 First Periodical Examination Morning ShiftDocumento2 páginasCri 010 First Periodical Examination Morning ShiftMark Rovi ClaritoAinda não há avaliações

- 2017 Bar Political Law Questions and AnswersDocumento8 páginas2017 Bar Political Law Questions and AnswersMark RyeAinda não há avaliações

- Example Exam QsDocumento4 páginasExample Exam QsC Kar HongAinda não há avaliações

- (정책연구2019-14) 대전광역시 자치경찰제 도입 및 시행 방안에 관한 연구Documento153 páginas(정책연구2019-14) 대전광역시 자치경찰제 도입 및 시행 방안에 관한 연구thai2333flamAinda não há avaliações

- Script For Presentation of EvidenceDocumento4 páginasScript For Presentation of EvidenceStewart Paul Torre100% (15)

- Linda Maldonado Santiago v. Nestor Velazquez Garcia, 821 F.2d 822, 1st Cir. (1987)Documento15 páginasLinda Maldonado Santiago v. Nestor Velazquez Garcia, 821 F.2d 822, 1st Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- People V Gacott Jr.Documento2 páginasPeople V Gacott Jr.Ma. Jillian de los TrinosAinda não há avaliações

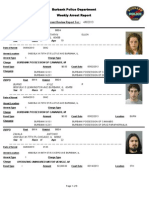

- BBPD Arrests 482013Documento8 páginasBBPD Arrests 482013api-214091549Ainda não há avaliações

- Dar V DecsDocumento3 páginasDar V DecsAdi Lim100% (1)

- Admin Law Attack Outline ChecklistDocumento4 páginasAdmin Law Attack Outline Checklistbillsfan114Ainda não há avaliações

- Dans Vs PeopleDocumento1 páginaDans Vs PeopleEmeAinda não há avaliações

- Writ of Mandamus-Writ of Error-Averment FiledDocumento4 páginasWrit of Mandamus-Writ of Error-Averment FiledYaw Mensah Amun Ra100% (2)

- 2016 (GR 174379, E.I. Dupont de Nemours and Co. v. Francisco)Documento27 páginas2016 (GR 174379, E.I. Dupont de Nemours and Co. v. Francisco)Michael Parreño VillagraciaAinda não há avaliações

- 34.1 Ortigas & Co. vs. Feati Bank DigestDocumento2 páginas34.1 Ortigas & Co. vs. Feati Bank DigestEstel Tabumfama100% (4)

- Edited Final Shape of C.P.C.syllABUSDocumento14 páginasEdited Final Shape of C.P.C.syllABUSRathin BanerjeeAinda não há avaliações

- The Commission On AuditDocumento5 páginasThe Commission On AuditJunDagz100% (1)

- Specific Performance Unaffected by WaiverDocumento5 páginasSpecific Performance Unaffected by WaiverZaza Maisara50% (2)

- Fermin V PeopleDocumento34 páginasFermin V PeopleMp CasAinda não há avaliações

- Criminal ProcedureDocumento17 páginasCriminal ProcedureRobby DelgadoAinda não há avaliações

- Layug Vs ComelecDocumento6 páginasLayug Vs ComelecIvan CubeloAinda não há avaliações

- 16 - People of The Philippines Vs Zaldy Salahuddin and ThreeDocumento2 páginas16 - People of The Philippines Vs Zaldy Salahuddin and Threesoojung jungAinda não há avaliações

- Serona v. CA DigestDocumento1 páginaSerona v. CA DigestJoms TenezaAinda não há avaliações

- Table of PenaltiesDocumento2 páginasTable of PenaltiesEzekiel FernandezAinda não há avaliações

- Pacta Sunt Servanda - Agreements Must Be KeptDocumento3 páginasPacta Sunt Servanda - Agreements Must Be KeptByron Jon TulodAinda não há avaliações

- Willie Yu v. Defensor SantiagoDocumento4 páginasWillie Yu v. Defensor SantiagoBianca TocaloAinda não há avaliações

- Barayuga V Adventis UniversityDocumento3 páginasBarayuga V Adventis UniversityanailabucaAinda não há avaliações

- XANTIPPLE CONERLY vs. ROSWELL PARK CANCER INSTITUTEDocumento18 páginasXANTIPPLE CONERLY vs. ROSWELL PARK CANCER INSTITUTEsconnors13Ainda não há avaliações

- Bail PDFDocumento2 páginasBail PDFSahidul IslamAinda não há avaliações

- Election Law Cases Batch 1Documento10 páginasElection Law Cases Batch 1Darlene GanubAinda não há avaliações