Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Public Service Regulations Cases

Enviado por

Jane Paez-De MesaDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Public Service Regulations Cases

Enviado por

Jane Paez-De MesaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

1. Luzon Stevedoring Co. Inc. and Visayan Transportation Co. vs. Public Service Commission 93 Phil. 735 | Tuason, J.

Stevedore

Facts: Petitioners are engaged in the stevedoring or lighterage and harbor towage business. They are also engaged in interisland service which consist of hauling cargoes such as sugar, oil, fertilizer and other commercial commodities. There is no fixed route in the transportation of these cargoes, the same being left at the indication of the owner or shipper of the goods. Petitioners, in their hauling business, serve only a limited portion of the public. The Philippine Shipowners Association complained to the Public Service Commission that petitioners were engaged in the transportation of cargo in the Philippines for hire or compensation without authority or approval of the Commission. The rates petitioners charged resulted in ruinous competition. The Public Service Commission restrained petitioners from further operating their watercraft to transport goods for hire or compensation between points in the Philippines until the commission approves the rates they propose to charge. Issue: Whether the petitioners fall under the definition in Section 13 (b) of the Public Service Law (C.A. Act No. 146)? Held: Yes. It is not necessary under said definition that one holds himself out as serving or willing to serve the public in order to be considered public service. It is not necessary, in order to be a public service, that an organization be dedicated to public use, i.e., ready and willing to serve the public as a class. It is only necessary that it must in some way be impressed with a public interest; and whether the operation of a business is a public utility depends upon whether or not the service rendered by it is of a public character and of public consequence and concern. It can scarcely be denied that the contracts between the owners of the barges and the owners of the cargo at bar were ordinary contracts of transportation and not of lease. Petitioners watercraft was manned entirely by crews in their employ and payroll, and the operation of the said craft was under their direction and control, the customers assuming no responsibility for the goods handled on the barges. C.A. No. 146 clearly declares that an enterprise of any of the kinds therein enumerated is a public service if conducted for hire or compensation even if the operator deals only with a portion of the public or limited clientele. Public utility, even where the term is not defined by statute, is not determined by the number of people actually served. The Public Service Law was enacted not only to protect the public against unreasonable charges and poor, inefficient service, but also to prevent ruinous competition. Just as the legislature may not declare a company or enterprise to be a public utility when it is not inherently such, a public utility may not evade control and supervision of its operation by the government by selecting its customers under the guise of private transactions.

Doctrine: An enterprise of any of the kinds enumerated in the Public Service Law is a public service if conducted for hire or compensation even if the operator deals only with a portion of the public or with limited clientele. 2. San Pablo vs Pantranco South Express, Inc. 153 SCRA 199 F: Pantranco operates passenger buses from Metro Manila to Bicol and Eastern Samar. It wrote to the Maritime Industry Authority (MARINA) requesting authority to lease/purchase MV Black Double to be used in operating a ferryboat service from Matnog, Sorsogon and Allen, Samar that will provide service to co. buses and freight trucks that have to cross the Bernardo Strait. MARINA denied the petition on the ground that the Matnog- Allen run is adequately serviced by the Cardinal Shipping Corp. and Epitacio San Pablo and that market conditions cannot support the entry of additional tonnage. Pantranco acquired the vessel. It then applied to BOT claiming that it can operate a ferry service in connection with its franchise for bus operation in the highway from Pasay City to Tacloban City for the purpose of continuing the highway, which is interrupted by a small body of water, and that the proposed ferry operation is merely a necessary and incidental service to its main service and obligation of transferring passengers from Pasay City to Tacloban City. Accdg. to it, there is no need to obtain a separate CPC to operate a ferry service to cater exclusively to its passenger buses and ferry trucks. Pantranco began operating its ferry service. The BOT held that the ferryboat service is part of Pantranco's CPC and amended Pantranco's CPC to provide so. The two other ferry boat services filed motions for reconsideration. Issue : WON the sea can be considered as a continuation of the highway. WON a land transpo co. can be authorized to operate a ferry service or coastwise or interisland shipping service along its authorized route as an incident to its franchise without the need of filing a separate application for the same. Held : The water transport service between Matnog and Allen is not a ferryboat service but a coastwise or interisland shipping service. Before private respondent may be issued a franchise or CPC for the operation of the said service as a common carrier, it must comply with the usual reqts. of filing an application, payment of the fees, publication, adducing evidence at a hearing and affording the oppositors the opportunity to be heard. Considering the environmental circumstances of the case, the conveyance of passengers from Matnog to Allen is not a ferryboat service but a coastwise or interisland shipping service. Under no circumstances can the sea between Matnog and Allen be considered a continuation of the highway. While a ferryboat service has been considered as a continuation of the highway when crossing rivers or even lakes, which are small body of waters separating the land, however, when as in this case the two terminals are separated by an open sea, it cannot be considered a continuation of the highway. Pantranco must secure a separate CPC for the operation of an interisland or coastwise shipping service. Its CPC cannot be merely amended to include this water service under the guise that it is a mere private ferry service. Pantranco does not deny that it charges its passengers separately

from the charges for the bus trips and issues separate tickets whenever they board the MV Black Double. It cannot pretend that it issued tickets as a private carrier and not as a common carrier. It in fact accepts walk in passengers during the trips. It cannot claim that it is both a private carrier and a common carrier at the same time. In the case of Javellana vs PSC, the Court differentiated between ferry service and interisland or coastwide service. Ferry means service either by barges or rafts, even by motor or steam vessels, between the banks of a river or stream to continue the highway which is interrupted by a body of water, or in some cases, to connect two points on opposite shores of an arm of the sea such as a bay or lake which does not involve too great a distance or too long a time to navigate. But where the line or service involves crossing a body of water which is wide and dangerous with big waves, then such line or service belongs properly to interisland or coastwide trade. 3. Private nature: rights and obligations of parties inter se arising from transactions relating to transportation (a) absent a transportation contract (b) arising from a transportation contract (i) contract of transportation, defined - one whereby a certain person or association of persons obligate themselves to transport persons, things or news from one place to another for a fixed price (ii) contract of transportation, elements 3 LUCILA O. MANZANAL vs. MAURO A. AUSEJO Even on the assumption that it was petitioner's taxicab that was used by the escaping holduppers, there is no evidence that the driver is a co-conspirator in the commission of the offense of robbery. Conspiracy must be proved by clear and convincing evidence. The mere claim that the taxicab was there and probably waiting is not proof of conspiracy in this case as it should be recalled that there were about twelve vehicles that stopped to view the spectacle. Further, it is possible that the dr iver did not act voluntar ily as no person in his r ight senses would defy the wishes of armed passengers. Even on the assumption that the driver had participated voluntarily in the incident, his culpability should not be made a ground for the cancellation of the certificate of petitioner. While an employer may be subsidiarily liable for the employee's civil liability in a criminal action, subsidiary liability presupposes that there was a criminal action. Besides, in order that an employer may be subsidia rily liable, it should be shown that the employee committed the offense in the discharge of his duties. While it is true also that an employer may be primarily liable under Article 2180 of the Civil Code for the acts or omissions of persons for whom one is responsible, this liability extends only to damages caused by his employees acting within the scope of their assigned tasks. Clearly, the act in

question is totally alien to the business of petitioner as an operator and hence, the driver's illicit act is not within the scope of the functions entrusted to him. Moreover, t he action before respondent Commission is neither a criminal prosecution nor an action for quasi-delict. Hence, there is absolutely no ground to hold petitioner liable for the driver's act. Fin a lly, u n d e r Se c ti o n 16 (n ) of t h e Pu b li c Se r v ic e Ac t, t h e power of the Commission to suspend or revoke any certificate received under the provisions of the Act may only be exercised whenever the holder thereof has violated or willfully and contumaciously refused to comply with any order, rule or regulation of the Commission or any provision of the Act. In the absence of showing that there is willful and contumacious violation on the part of petitioner, no certificate of public convenience may be validly revoked. The following are some instances where the cancellation of a certificate of public convenience where held valid: (1) where the holder is a mere dummy (Pecson vs. Pecson, 78 Phil. 522); (2) where the operator ceased operation and placed his buses on storage (Parades vs. Public Service Commission, L-7111, May 30, 1955); and (3) where the operator abandons, totally the service (Collector vs. Buan, L-11438, July 31, 1958; Regodon vs. Public Service Commission, L-11899, Sept. 23, 1958; Paez vs. Marcelo, L-1530, March 30, 1962). None of the willful acts in patent violation of the Public Service Law can be attributed to petitioner herein 4 COGEO-CUBAO vs. CA FACTS: It appears that a certificate of public convenience to operate a jeepney service was ordered to be issued in favor of Lungsod Silangan to ply the Cogeo-Cubao route. On the other hand, Cogeo-Cubao Association was registered as a non-stock, non-profit organization with the main purpose of representing the appellee for whatever contract and/or agreement it will have regarding the ownership of units, and the like, of the members of the Association. Perturbed by appellees Board Resolution No. 9 adopting a Bandera' System under which a member of the cooperative is permitted to queue for passenger at the disputed pathway in exchange for the ticket worth 20 pesos the proceeds of which shall be utilized for Christmas programs of the drivers and other benefits, the Association decided to form a human barricade on and assumed the dispatching of passenger jeepneys. This development as initiated by the Association gave rise to the suit for damages. The Association's Answer contained vehement denials to the insinuation of take over and at the same time raised as a defense the circumstance that the organization was formed not to compete with plaintiff-cooperative. It, however, admitted that it is not authorized to transport passengers. The trial court rendered a decision in favor of respondent Lungsod Corp and ordered. The CA affirmed the findings of the TC except with regard to the award of actual damages. ISSUE:

W/N the petitioner usurped the property right of the respondent which shall entitle the latter to the award of nominal damages? - YES RULING: Under the Public Service Law, a certificate of public convenience is an authorization issued by the Public Service Commission for the operation of public services for which no franchise is required by law. In the instant case, a certificate of public convenience was issued to respondent corporation on to operate a public utility jeepney service on the CogeoCubao route. A certification of public convenience is included in the term "property" in the broad sense of the term. Under the Public Service Law, a certificate of public convenience can be sold by the holder thereof because it has considerable material value and is considered as valuable asset. Although there is no doubt that it is private property, it is affected with a public interest and must be submitted to the control of the government for the common good. Hence, insofar as the interest of the State is involved, a certificate of public convenience does not confer upon the holder any proprietary right or interest or franchise in the route covered thereby and in the public highways. However, with respect to other persons and other public utilities, a certificate of public convenience as property, which represents the right and authority to operate its facilities for public service, cannot be taken or interfered with without due process of law. Appropriate actions may be maintained in courts by the holder of the certificate against those who have not been authorized to operate in competition with the former and those who invade the rights which the former has pursuant to the authority granted by the Public Service Commission. In the case at bar, the trial court found that petitioner association forcibly took over the operation of the jeepney service in the Cogeo-Cubao route without any authorization from the Public Service Commission and in violation of the right of respondent corporation to operate its services in the said route under its certificate of public convenience. These were its findings which were affirmed by the appellate court. It is clear form the facts of this case that petitioner formed a barricade and forcibly took over the motor units and personnel of the respondent corporation. This paralyzed the usual activities and earnings of the latter during the period of ten days and violated the right of respondent Lungsod Corp to conduct its operations thru its authorized officers. No compelling reason exists to justify the reversal of the ruling of the respondent appellate court in the case at bar. Considering the circumstances of the case, the respondent corporation 5. Kilusang Mayo Uno Labor Center vs Garcia 239 SCRA 538 (1994) Facts: The Kilusang Mayo Uno Labor Center (KMU) assails the constitutionality and validity of a memorandum which, among others, authorize provincial bus and jeepney operators to increase or decrease the

prescribed transportation fares without application therefore with the LTFRB, and without hearing and approval thereof by said agency. Issue: Whether or not the absence of notice and hearing and the delegation of authority in the increase or decrease of transportation fares to provincial bus and jeepney operators is illegal? Held: Under Section 16 (c) of the Public Service Act, as amended, the legislature delegated to the defunct Public Service Commission the power of fixing the rates of public services. LTFRB, the existing regulatory body today, is likewise vested with the same under Executive Order 202. The authority given by the LTFRB to the bus operators to set fares over and above the authorized existing fare is illegal and invalid, as it is tantamount to undue delegation of legislative authority. Under the maxim potestas delegate non delegari potest what has been delegated cannot be delegated. The policy allowing provincial bus operators to change and increase their fares would result not only to a chaotic situation but to an anarchic state of affairs. This would leave the riding public at the mercy of transport operators who may increase fares, every hour, every day, every month or every year, whenever it pleases them or whenever they deem it necessary to do so. Furthermore, under the Section 16 (a) of Public Service Act, there must be proper notice and hearing in the fixing of rates, to arrive at a just and reasonable rate acceptable to both the public utility and the public. 6. Francisco Tatad, John Osmena and Rodolfo Biazon, petitioners, vs. Hon. Jesus Garcia, in his capacity as the Secretary of the Department of Transportation & Communications, and EDSA LRT CORPORATION, LTD., respondents. Facts: This is a petition under Rule 65 of the Revised Rules of Court to prohibit respondents from further implementing the Revised and Restated Agreement to Build, Lease and Transfer a Light Rail Transit System for EDSA and the Supplemental Agreement to the same project. Petitioners Francisco Tatad, John Osmena and Rodolfo Biazon are members of the Philippine Senate and are suing in their capacities as Senators and as taxpayers. Respondent Jesus Garcia was then Secretary of the DOTC, while private respondent EDSA LRT CORPORATION, Ltd. is a private corporation organized under the laws of Hongkong. In 1989, DOTC planned to construct a light railway transit line along EDSA, which shall traverse the cities of Pasay, Quezon, Mandaluyong and Makati. The objective is to provide a mass transit system along EDSA and to alleviate the congestion in the metropolis. On March 15, 1990, then DOTC Secretary Oscar Orbos, acting upon a

proposal to construct the EDSA LRT III on a Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) basis, had invited Elijahu Levin from the Eli Levin Enterprises, Inc to send a technical team to discuss the project with the DOTC. On July 9, 1990, RA No. 6957 referred to as the Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) was signed by then President Corazon Aquino. The said Act provides for two schemes for the financing, construction and operation of government projects through private initiative and investment: BOT or Build-Transfer (BT). In accordance with the provisions of RA 6957 and to set the EDSA LRT III project underway, the Prequalification Bids and Awards Committee and the Technical Committee were formed. The prequalification criteria totalling 100% are as follows: a.) Legal aspects 10%; b.) Management/Organizational capability 30%; c.) Financial capability- 30%; and d.) Technical capability 30%. Of the 5 applicants, only the EDSA LRT Consortium met the requirements of garnering at least 21 points per criteria, except for Legal aspects, and obtaining an over-all passing mark of at least 82 points. The Legal aspects referred to provided that the BOT/BT contractor-applicant meet the requirements specified in the Constitution and other pertinent laws. Subsequently, Sec. Orbos was appointed Executive Secretary to the President of the Philippines and was replaced by Nicomedes Prado. The latter recommended the award of the EDSA LRT III project to the sole complying bidder, the EDSA LRT Consortium, and requested for authority to negotiate with the said firm for the contract pursuant to the BOT Law. Authority was granted to proceed with the negotiations. The EDSA LRT Consortium submitted its proposal to DOTC. Finding the proposal to be in compliance with the bid requirements, DOTC and EDSA LRT Corporation, Ltd., in substitution of the EDSA LRT Consortium, entered into an An Agreement to Build, Lease and Transfer a Light Rail Transit System for EDSA under the terms of the BOT Law. Secretary Prado, thereafter, requested presidential approval of the contract. Exec. Sec. Franklin Drilon, who replaced Sec. Orbos, informed Sec. Prado that the President could not grant the requested approval for failure to comply with the requirements of the BOT Law. In view whereof, Sec. Drilon, the DOTC and private respondent renegotiated the agreement. On April 22, 1992, the parties entered into a Revised and Restated Agreement to Build, Lease and Transfer and Light Rail Transit System for EDSA. On May 6, 1992, DOTC, represented by Sec. Jesus Garcia, Sec. Prado and private respondent entered into a Supplemental Agreement to the April Revised Agreement so as to clarify their respective rights and responsibilities. The two agreements were approved by President Fidel Ramos.

According to the agreements, the EDSA LRT III will use light rail vehicles from the Czech and Slovak Federal Republics and will have a maximum carrying capacity of 450,000 passengers a day. The system will have its own power facility. It will also have 13 passenger stations and one depot in 16-hectare government property at North Avenue. Private respondents shall undertake and finance the entire project required for a complete operational light rail transit system. Target completion date is approximately 3 years from the implementation date of the contract. Upon full and partial completion and viability thereof, private respondent shall deliver the use and possession of the completed portion to DOTC which shall operate the same. DOTC shall pay private respondent rentals on aj monthly basis through an Irrevocable Letter of Credit. The rentals shall be determined by an independent and internationally accredited inspection firm to be appointed by the parties. As agreed upon, private respondents capital shall be recovered from the rentals to be paid by the DOTC which, in turn, shall come from the earnings of the EDSA LRT III. After 25 years and DOTC shall have completed payment of the rentals, ownership of the project shall be transferred to the latter for a consideration of only US $1.00. In their petition, petitioners argued that the agreement of April 22, 1992, as amended by the Supplemental Agreement of May 6, 1993, in so far as it grants EDSA LRT COPORTATION, LTD., a foreign corporation, the ownership of EDSA LRT III, a public utility, violates the constitution, and hence, is unconstitutional. They contend that the EDSA LRT III is a public utility, and the ownership and operation thereof is limited by the Constitution to Filipino citizens and domestic corporations, not foreign corporations like private respondent. Issue: Whether or not the EDSA LRT III assumes all the obligations and liabilities of a common carrier. Held: What private respondent owns are the rail tracks, rolling stocks like the coaches, rail stations, terminals and the power plant, not a public utility. While a franchise is needed to operate these facilities to serve the public, they do not by themselves constitute a public utility. What constitutes a public utility is not their ownership but their use to serve the public. Section 11 of Article XII of the Constitution provides: No franchise, certificate or any other form of authorization for the operation of a public utility shall be granted except to citizens of the Philippines or to corporations or associations organized under the laws of the Philippines at least sixty per centum of whose capital is owned by such citizens, nor shall such franchise, certificate or authorization be exclusive character or for a longer period than 50 years. The right to operate a public utility may exist independently and

separately from the ownership of the facilities thereof. One can own said facilities without operating them as a public utility, or conversely, one may operate a public utility without owning the facilities used to serve the public. The devotion of property to serve the public may be done by the owner or by the person in control thereof who may not necessarily be the owner thereof. While private respondent is the owner of the facilities necessary to operate the EDSA LRT III, it admits that it is not enfranchised to operate a public utility. In view of this incapacity, private respondent and DOTC agreed that on completion date, private respondent will immediately deliver possession of the LRT system by of lease for 25 years, during which period DOTC shall operate the same as a common carrier and private respondent shall provide technical maintenance and repair services to DOTC. Since DOTC shall operate the EDSA LRT III, it shall assume all the obligations and liabilities of a common carrier. For this purpose, DOTC shall indemnify and hold harmless private respondent from any losses, damages, injuries or death which may be claimed in the operation or implementation of the system, except losses, damages, injury or death due to defects in the EDSA LRT III on account of the defective condition of equipment or facilities or the defective maintenance of such equipment facilities. Wherefore, the petition is DISMISSED. 7. PAL vs. CAB FACTS GrandAir applied with the Civil Aeronautivcs Board for a Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity for the MLA-CEBU and MLA-DAVAO route. Accordingly, the Chief Hearing Officer of the CAB issued a Notice of Hearing setting the application for initial hearingn and directing GrandAir to serve a copy of the application and corresponding notice to all scheduled Philippine Domestic operators. GrandAir filed its Compliance, and requested for the issuance of a Temporary Operating Permit. PAL, itself the holder of a legislative franchise to operate air transport services, filed an opposition to the application on several grounds which include LACK OF JURISDICTION ON THE PART OF THE BOARD to hear the application until GrandAir has obtained a franchise to operate from Congress. (Other grounds were deficient form and substance of the application; violation of the equal protection clause if application is granted; no urgent need for new service; granting of application would result in ruinous competition.) The Board ruled that it had jurisdiction to hear the application. The Board even granted GrandAir a Temporary Operating License. PALs motion for reconsideration was denied. The Board even granted a 6-month extension to GrandAirs temporary permit.

PAL says: Board acted beyond its powers and jurisdiction: (1) in taking cognizance of GrandAir's application for the issuance of a Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity, and (2) in issuing a temporary operating permit in the meantime. Reasoning of PAL: GrandAir has not been granted and does not possess a legislative franchise to engage in scheduled domestic air transportation. A legislative franchise is necessary before anyone may engage in air transport services, and a franchise may only be granted by Congress. This is the meaning given by the PALupon a reading of Section 11, Article XII, and Section 1, Article VI, of the Constitution. In support of this, PAL presents a 1994 DOJ opinion by Secretary Ordonez where a distinction was made between the franchise to operate and a permit to commence operation. According to the opinion, it is clear that a franchise is the legislative authorization to engage in a business activity or enterprise of a public nature, whereas a certificate of public convenience and necessity is a regulatory measure which constitutes the franchise's authority to commence operations. It is thus logical that the grant of the former should precede the latter. GrandAir argues: The Board has: (1) the authority to hear the application and, (2)can grant temporary operating permits and certificates of public convenience and necessity. GrandAirs reasoning: (1) Section 10 (specifically 10-C1) of RA 776 grants it such authority to issue, deny, amend revise, alter, modify, cancel, suspend or revoke, in whole or in part, upon petitioner-complaint, or upon its own initiative, any temporary operating permit or Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity. (2) Jurisprudence: SC ruled in another PAL vs CAB case (1968) that CAB could, even on its own initiative, grant a temporary operating permit (TOP) even before the presentation of evidence. CA cases which held that CAB can grant not only temporary operating permit (TOP) but also a Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity (CPCN) SC decision in Albano vs Reyes: a) Franchises by Congress are not required before each and every public utility may operate when the law has granted certain administrative agencies the power to grant licenses for or to authorize the operation of certain public utilities; (b) The Constitutional provision in Article XII, Section 11 that the issuance of a franchise, certificate or other form of authorization for the operation of a public utility does not necessarily imply that only Congress has the power to grant such authorization... (3) EO 219: a minimum of 2 operators in each route/ link shall be encouraged. ISSUE W/N Congress, in enacting Republic Act 776, has delegated the authority

to authorize the operation of domestic air transport services to the respondent Board, such that Congressional mandate for the approval of such authority is no longer necessary RULING Yes. The Board has the authority. The trend of modern legislation is to vest the Public Service Commissioner with the power to regulate and control the operation of public services under reasonable rules and regulations, and as a general rule, courts will not interfere with the exercise of that discretion when it is just and reasonable and founded upon a legal right. It is this policy which was pursued by the Court in Albano vs. Reyes (cited above). There is nothing in the law nor in the Constitution, which indicates that a legislative franchise is an indispensable requirement for an entity to operate as a domestic air transport operator. Although Section 11 of Article XII recognizes Congress' control over any franchise, certificate or authority to operate a public utility, it does not mean Congress has exclusive authority to issue the same. Franchises issued by Congress are not required before each and every public utility may operate. In many instances, Congress has seen it fit to delegate this function to government agencies, specialized particularly in their respective areas of public service. Reading Section 10 of RA 776 shows the clear intent of Congress to grant CAB the authority to issue TOP and CPCN. The SC did not agree with PALs argument that granting of a franchise and granting a TOP or CPCN are two different things; and that a grant of franchise from Congress is necessary before the Board can grant either TOP or CPCN. Congress, by giving the respondent Board the power to issue permits for the operation of domestic transport services, has delegated to the said body the authority to determine the capability and competence of a prospective domestic air transport operator to engage in such venture. This is not an instance of transforming the respondent Board into a mini-legislative body, with unbridled authority to choose who should be given authority to operate domestic air transport services. o Congress set specific limitations on the Boards authority in Sec. 4 of the RA776 (Declaration of Policies). o More importantly, under Sec. 12-24 of RA 776, Congress has spelled out the requirements for determining the competency of a prospective operator, as well as the procedure for the processing of the applications. SC dismissed PALs opposition to the hearings set by CAB for GrandAirs application for CPCN.

Você também pode gostar

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Ls Sze L 190800539Documento1 páginaLs Sze L 190800539Mubarak Ali ShinwariAinda não há avaliações

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- FPSO Benchmarking Report 2000Documento66 páginasFPSO Benchmarking Report 2000alan_yaobin8409Ainda não há avaliações

- PDA Repair FormDocumento2 páginasPDA Repair FormVincent TonAinda não há avaliações

- ACCTG102 MidtermQ2 InventoriesDocumento10 páginasACCTG102 MidtermQ2 InventoriesDayan DudosAinda não há avaliações

- Glendale PartnerDocumento94 páginasGlendale PartnerPutri Mulia SariAinda não há avaliações

- BL LlenoDocumento1 páginaBL LlenoAnunnaki Ocampo100% (1)

- SAP EWM Value Added Services Kitting During Picking: Slide 1Documento10 páginasSAP EWM Value Added Services Kitting During Picking: Slide 1kristian yotovAinda não há avaliações

- DEL VAL vs. Del ValDocumento3 páginasDEL VAL vs. Del ValJane Paez-De MesaAinda não há avaliações

- Dnata Cargo - Study MaterialDocumento47 páginasDnata Cargo - Study MaterialKishore Khatri86% (7)

- Ejemplo de MBL OneDocumento3 páginasEjemplo de MBL OneVanessa AnguloAinda não há avaliações

- Ocean Freight Operations Procedure - 2013Documento69 páginasOcean Freight Operations Procedure - 2013krmrpsAinda não há avaliações

- Material Requirement Planning (MRP)Documento26 páginasMaterial Requirement Planning (MRP)ARJUN VAinda não há avaliações

- Sample Memorandum For The Prosecution - Falsification CaseDocumento10 páginasSample Memorandum For The Prosecution - Falsification CaseJane Paez-De MesaAinda não há avaliações

- (Dongyue) Concrete Block Machine CatalogueDocumento16 páginas(Dongyue) Concrete Block Machine Catalogueaacblockmachine100% (1)

- Abella vs. CSCDocumento2 páginasAbella vs. CSCJane Paez-De MesaAinda não há avaliações

- Soliven and FigueroaDocumento4 páginasSoliven and FigueroaJane Paez-De MesaAinda não há avaliações

- De Los Santos vs. IAC and Republic vs. SandiganbayanDocumento3 páginasDe Los Santos vs. IAC and Republic vs. SandiganbayanJane Paez-De MesaAinda não há avaliações

- De Los Santos vs. IAC and Republic vs. SandiganbayanDocumento3 páginasDe Los Santos vs. IAC and Republic vs. SandiganbayanJane Paez-De MesaAinda não há avaliações

- Torts Magic NotesDocumento43 páginasTorts Magic NotesJane Paez-De MesaAinda não há avaliações

- Gevero vs. IACDocumento8 páginasGevero vs. IACJane Paez-De MesaAinda não há avaliações

- Great Pacific Life, Figuracion vs. Consolacion, and Ang Ka YuDocumento2 páginasGreat Pacific Life, Figuracion vs. Consolacion, and Ang Ka YuJane Paez-De MesaAinda não há avaliações

- National DevDocumento2 páginasNational DevJane Paez-De MesaAinda não há avaliações

- National DevDocumento2 páginasNational DevJane Paez-De MesaAinda não há avaliações

- Agitator - 2 PDFDocumento11 páginasAgitator - 2 PDFParth ThakarAinda não há avaliações

- Global Supply Chain Summit Brochure-2018Documento4 páginasGlobal Supply Chain Summit Brochure-2018Chaitanya M MundheAinda não há avaliações

- Loberiano, M. RORO Port Comparative ResearchDocumento12 páginasLoberiano, M. RORO Port Comparative ResearchmhykzloberianoAinda não há avaliações

- RA Marine Approval List 20140318Documento60 páginasRA Marine Approval List 20140318andyhilbertAinda não há avaliações

- Aung Kyaw Moe-Task (5) - Unit (2) Warehouse and InventoryDocumento10 páginasAung Kyaw Moe-Task (5) - Unit (2) Warehouse and InventoryAung Kyaw MoeAinda não há avaliações

- CV Viorica Bode 20180628Documento3 páginasCV Viorica Bode 20180628viosbAinda não há avaliações

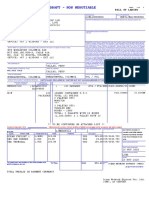

- Letter of Credit ExportDocumento3 páginasLetter of Credit ExportMakrand SableAinda não há avaliações

- ReportDocumento16 páginasReportEnriqueAinda não há avaliações

- Reorder PointDocumento23 páginasReorder PointMary Grace Ramos BalbonaAinda não há avaliações

- Ramayan ICD Prashun Jain Prashant Gupta Global LogicDocumento232 páginasRamayan ICD Prashun Jain Prashant Gupta Global LogicjainAinda não há avaliações

- 80440-Trade in Microsoft Dynamics NAV 2013Documento5 páginas80440-Trade in Microsoft Dynamics NAV 2013amsAinda não há avaliações

- National Air ExpressDocumento1 páginaNational Air ExpressUtkarsh Shrivatava100% (1)

- 20200331103634.rateconDocumento4 páginas20200331103634.rateconMircea MarianAinda não há avaliações

- Damage StabilityDocumento4 páginasDamage StabilityBhushan PawaskarAinda não há avaliações

- Methods of Computing Economic Order QuantityDocumento20 páginasMethods of Computing Economic Order QuantityMyrn de AsisAinda não há avaliações

- Bonny SCM 1Documento30 páginasBonny SCM 1Atikah AAinda não há avaliações

- RoadsDocumento111 páginasRoadsNathar ShaAinda não há avaliações

- Commercial Letter of Credit Application Form: Applicant BeneficiaryDocumento2 páginasCommercial Letter of Credit Application Form: Applicant BeneficiaryUMgAinda não há avaliações