Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Media Contribution To Peace Building in War

Enviado por

Juan David CárdenasDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Media Contribution To Peace Building in War

Enviado por

Juan David CárdenasDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

1

Wilhelm Kempf

Media contribution to peace building in war torn societies

Abstract

Since the end of the Cold War, several military conflicts, some of which had been going on for decades, have successfully been resolved. Yet, the mere ratification of a peace treaty does not solve the problem of how to repair, materially, socially, humanly, war-torn societies. Without systematic efforts of peacebuilding, conflicts might endure, and there is always the danger that violence might break out again. The present paper focusses on the role of the media in these times of transition from war to peace. Based on empirical research on the news coverage of the Gulf War and the Bosnia conflict in American and European media, the paper aims at finding out whether and how the media may support the transition from war culture to peace culture. Such an attempt might involve each of the following aspects: deescalation-oriented conflict coverage, strengthening of the civil society and demolition of stereotypes and prejudice. Special emphasis will be given to means by which a peace process itself, and even its disturbances and crises can be depicted in a way that supports the reconciliation of the former war parties, and that does not fall back into the logic of polarization.

1. Media contribution to war culture 1.1 Social psychological aspects of war culture War culture is characterized by dualistic thinking and the polarities it generates. To strengthen the peace process means to undermine these polarities. The question is how to do it. One way Interiano (1996) forsees this is to acknowledge that no one has the absolute standards of truth, since truth is highly relative and gives way to a variety of interpretations.

The autonomous process of conflict Each conflict involves three modes of reality. The contrary "subjective realities" that the conflict has for each of the parties involved, which result from their own entanglement in the conflict, and a - so to speak - "objective reality" which can be seen from outside of the conflict only. While each of the parties tends to believe in the justification of its own goals, intentions and actions which they fear to be threatened by the opponent, an inspection of the conflict from outside may unveal how these feelings of justification and threat interact with each other and transform the conflict into an autonomous process (cf. Figure 1) in which each of the parties believe to defend itself against a dangerous aggressor (Kempf, 1993). In order to break this autonomous process, it is essential that the parties learn to be critical about their own view of the conflict, and to enter into a process of role taking. The more a conflict has ecalated, the more diffult this becomes, however. Intractable conflicts are demanding, stressful, painful, exhausting and costly both in human and material terms. This requires that society members develop conditions which enable successful coping. One type of the conditions which war culture provides is a psychological infrastructure which consists, for example, of devotion to the own side and its leadership, maintenance to its objectives, high motivation

to contribute, endurance and readiness for personal sacrifice. Bar-Tal (1996) proposed that societal beliefs fulfill an important role in the formation of these psychological conditions. They are part of society's ethos, and construct society members' view of the conflict and motivate them to act on behalf of the society and to harm the enemy. According to Bar-Tal, these societal beliefs include: 1. Beliefs about the justness of one's own goals. 2. Beliefs about security. 3. Beliefs of positive self image. 4. Beliefs of own victimization. 5. Beliefs of delegitimizing the opponent. 6. Beliefs of patriotism. 7. Beliefs of unity. 8. Beliefs of peace as the ultimate desire of the society. According to Bar-Tal it can be assumed, that these societal beliefs can be found in any society engaged in intractable conflict, especially those that successfully cope with it. These beliefs are far from being sufficient to win a conflict. Other conditions of military, political and economic nature must also be fulfilled. But these conditions are necessary for enduring the intractable conflict. Any warfaring nation, therefore, tries to produce, and maintain these beliefs by means of propaganda which aim at maximizing the citizens' willingness for war by means of persuasion, or, as Lasswell (1927) puts it: "Civilian unity is not achieved by the regimentation of muscles. It is achieved by a repetition of ideas rather than movements. The civilian mind is standardized by news not by drills. Propaganda is the method by which this process is aided and abetted." 1.2 Principles of propaganda

In his book "The Ancient Foe", Luostarinen (1986) developed an analytical model of war propaganda, designed to analyse the content of propaganda and to compare propaganda in different wars. According to Luostarinen, both restrictive and supportive methods of information control are used to get people to strongly and personally identify themselves with the goals of war. 1. Restrictive methods try to minimize all information which could cause negative effects on the fighting spirit. This is handled by cencorship. 2. Supportive methods try to maximize all information with a positive effect. This is handled by fabrication, selection and exaggeration of information. Though truth is only raw material for the propagandist (and if you have to lie, that is only a technical and operational question, not a moral one), it is better if no lies are needed. This can be achieved if the propagandist succeeds to manipulate the audience's entanglement into the topic of propaganda in order to influence its interpretations in a way that is apt to

reorganize its hierarchy of values so that winning the war is on the top, and all other values - for instance the truth, ethical considerations and individual rights - are only subservient to this goal. In order to get people entangled in the conflict, war propaganda produces incentives for social identification with the own side's political elite, soldiers and victims of war. These incentives for identification also tell us how our community, group or society is created, what it stands for, how it differs from other groups and what its aim is in the future. In order to establish identification with the own side's belligerents, three levels of manipulative measures are put into action: - On the level of the conflict context, propaganda tells us the roots of the conflict, why it was unavoidable, what we are defending and why the enemy did attack. - The level of day-to-day events contains classical propaganda material like description of battles, expressions of support coming from other countries, heroic stories and stories of atrocity. - The level of myths, finally, contains material about the logic of history, about the meaning of life, about the value of the individual life, etc. Any successful propaganda is a coherent construction with tight links between the different levels. A typical pattern of war propaganda might be that single day to day stories are selected and written in a way that fits into the conflict context which supports the suggested identification and which enforces the myths. Myths, as we know, are told in the form of concrete stories, and the order of the elements in the story tells the myths. 1.3 Logic of conflict escalation

Though still existent, traditional state propaganda as characteristic during the World Wars (cf. Lasswell, 1927; Knightly, 1975) has been partly delegated to professional PRagencies in recent conflicts (cf. Kunczik, 1990; McArthur, 1993). But, even if no systematic propaganda takes place, the way media operate, reporting on war and violence, often makes them support those societal beliefs that maintain and escalate intractable conflicts, and thus serve as catalysts to unleash violence rather than to contribute to deescalation and to constructive, nonviolent conflict transformation (cf. Galtung, 1997). 1. In order to make news stories more thrilling and the conflict more easily to be understood by the audience, media tend to black and white painting and to portray the conflict as a zero-sum-game between "good and evil". 2. Journalists usually share the beliefs of the society they belong to, and - in particular - those societal beliefs which enable the society to cope with intractable conflict.

3. These beliefs are not just the outcome of propaganda, but result from psychological processes that take place whenever a conflict is conceptualized as a competitive (win-lose-model) rather than a cooperative (win-win-model) process (cf. Deutsch, 1976, Kempf, 1996a). In every conflict (cf. Figure 2) there are own rights and intentions, and there are actions of an opponent that interfere with them and are experienced as threat. At the same time, as some of our actions interfere with his rights and intentions, the opponent experiences to be threatened as well. Still, there is some kind of common ground, there are common rights and intentions and a common benefit resulting from the relationship between the two parties, which may give reason for mutual trust. So far, any conflict is open to be conceptualized either as a cooperative or as a competitive process. Yet systematic divergence of perspectives makes it difficult for the parties in a conflict to come to a complete view on the conflict (cf. Figure 3). The parties' perspectives focus on their own rights and intentions and the threat by the other's actions, which at the same time - seem to threaten common rights and intentions and the common benefit as well.

The next step of escalation will result if the conflict is interpreted as a competitive process (cf. Figure 4). In this case, common rights and intentions as well as the common benefit that stems from the parties' mutual relationship tend to get out of sight. Mutual trust gets lost. Perception of the conflict is reduced to perception of one's own rights and intentions and their being threatened by the opponent. In case of further escalation from competition to struggle (cf. Figure 5), the opponent's rights are denied and his intentions are demonized. Own actions that interfere with the opponent's rights and intentions are justified, and one's own strength is emphasized. As a counterpart to the perceived threat by the opponent, confidence in one's own victory and in the prevailing of one's own rights and intentions emerges. At the same time, these own rights and intentions tend to be idealized. Actions by the opponent, that interfere with them, are condemned, and his dangerousness is underlined. The threat imposed to the opponent is denied. The opponent's attacks appear as unjustified and bring about mistrust against him.

Finally, further escalation to warfare reduces the perception of the conflict to military logic (cf. Figure 6): Peaceful alternatives are refuted, mistrust against the enemy is stimulated. Common interests that might be the basis for nonviolent, constructive conflict resolution are denied, and so are possibilities of cooperation with the enemy. (Justified) indignation with the war is conversed into (self-righteous) indignation with the enemy: the common suffering that the war brings about, as well as the common benefit that a peaceful conflict resolution could entail, cannot be seen any more. 1.4 The role of the media

From social psychology, we also know that escalated conflicts affect the rank order within a group or society. Those, who are outstanding for their fighting spirit, gain influence. Willingness to compromise and attempts at mediation are regarded as betrayal (Deutsch, 1976). This process of social commitment to antagonism affects the journalists' work in serveral ways: 1. Since journalists are members of the society themselves, they are under pressure to adopt an antagonistic view of the conflict in order to maintain their own social status and influence, and 2. since journalism has a strong bias towards elites, both, as sources of information and as subjects of coverage (cf. Galtung, 1998), a good deal of the information on which journalistic work is based, is not mere facts, but facts which are already interpreted in an antagonistic way - and most of the newsstories are stories about those who are on the forefront of antagonism. Accordingly, it is no surprise if the media coverage is victim to the same systematic distortions of conflict perception as the rest of the society. As comparative studies of the Gulf War coverage (cf. Kempf, 1996b, 1997, 1998; Elfner, 1998; Kempf, Reimann & Luostarinen, 1998; Kempf & Reimann, in preparation) and the coverage of the Bosnia conflict (Kempf, in preparation) in American and European media have shown, it is not only the warfaring nations, whose media are susceptible to such distortions. The more a society is involved in the conflict itself and the closer it is to the conflict region (on historical, political, economical or ideological terms), however, the more escalationoriented will its media cover the conflict. 2. Media contribution to peace building Once a ceasefire or peace treaty is settled, this antagonistic bias of the media becomes counterproductive. Unfortunately, however, even the most powerful political leaders cannot just switch to a cooperative strategy without taking the risk to loose power (or even their lives). The societal beliefs which

10

helped the society to endure intractible conflict still prevail and the transition from war culture to peace culture calls for a gradual process of strengthening the civil society, and demolishing stereotypes and prejudice. This cannot be achieved by simply spreading a new ideology which is determined by harmony and cooperative ideals, however. As the survival of ethnic antagonism in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union shows, not even totalitarian regimes have the power to do so. If stereotypes and prejudice are suppressed only, they will prevail under cover and return to the surface of social life as soon as they are given the slightest chance. 2.1 Deconstruction of the antagonism between good and evil

The societal beliefs which help a society to cope with intractible conflict are not just an ideology which is imposed on society from outside or by its political leaders. They result from a long history of experience with concrete conflicts at a high level of escalation and

11

can be understood as a generalized interpretation of such conflicts. In particular, this is the case with those societal beliefs, which construct the conflict as intractible: beliefs about justness, security, positive self image, own victimization and delegitimation of the opponent. The idealization of own rights and goals in a multitude of concrete conflicts gradually unfolds into a general rational of justification which sets the unconditional justness of own goals as an axiom and justifies their crucial importance (cf. Figure 7).

12

The repeated construction of conflicts as zero-sum games, the resulting experience of threat, the designation of force as an appropriate means to conflict resolution, the emphasis on military values and the confidence to win, as well as the mistrust against the enemy, refusal to admit mutual cooperation and rejection of peaceful alternatives link personal and national security together and outline the confrontative strategy as the only means how personal safety and national survival can be achieved (cf. Figure 8).

13

Idealization of own rights and goals, justification of own side's actions and underlining the own correctness, as well as emphasis on own strength in a multitude of concrete conflicts provide the concrete "facts" on which a positive self image can build, attributing positive traits, values and behavior to the own society (cf. Figure 9).

14

Repeated condemnation of the opponent's actions that violate our rights and goals, emphasis on his dangerousness and the transformation of indignation with the war into indignation with the enemy are condensed into a syndrome of own victimization, which provides the moral incentive to seek justice and to oppose the enemy, and which allows to mobilize moral, political and material support of the international community (cf. Figure 10).

15

The denial of the opponent's rights, demonisation of his intentions, condemnation of his actions and emphasis on his dangerousness in a multitude of concrete conflicts unfold into a general rational of deligitimizing the opponent, which explains the causes of the conflict's outbreak, its continuation and the violence of the opponent, as well as it justifies own hostile acts by dehumanization of the enemy and categorizing him "into extreme negative social categories which are excluded from human groups that are considered as acting within limits of acceptable norms and/or values" (Bar-Tal, 1989, p.170) (cf. Figure 11). Once, these beliefs have emerged in a society, they provide a framework that interprets literally every interaction with the opponent as another scene in the big drama of antagonism

16

between good and evil. And once an event has been interpreted in this way, it seemingly gives proof to the stereotypes and prejudice that created this interpretation. There is no way out of this vicious circle, but if we learn to accept facts before they are interpreted (Martin-Bar, 1991). If we accomplish this, even conflicts that prevail after a peace treaty or that arise during the peace process can provide experiences that gradually demolish prejudices and transform war culture into a more constructive social contract between the former enemies. The first rule for journalism which tries to facilitate such a process of social learning will be to mistrust the plausible on each of the four levels of 1. Conceptualization of the conflict, 2. Evaluation of the conflict parties' rights and intentions, 3. Evaluation of their actions, and 4. Emotional involvement in the conflict (cf. Figure 12).

17

The second rule will be to investigate the facts behind the plausible: 1. War culture tends to reduce the conflict to two parties, fighting for one goal (which is to win) and has a general sero-sum orientation that excludes constructive transformation of the conflict. The real conflict, usually, is not this simple: there are several parties involved, several goals and a multitude of issues, and there is always the possibility of an outcome that might serve the interests of all parties. Deescalation oriented conflict coverage thus has to explore the conflict formation, and to investigate causes and possible outcomes of the conflict, that might be found anywhere, and not just in the closed space of the conflict arena (cf. Galtung, 1998). 2. In order to come to a realistic evaluation of the conflict parties' rights, their intentions and actions, deescalation oriented coverage of conflicts must give voice to all parties and apply empathy and understanding regardless of any distinction between "us" and "them". At the same time it has to expose untruth on all sides and not just "their" cover-ups and "their" propaganda-lies. 3. On the level of emotional involvement, this will be a first step towards reducing own feelings of threat and thus decrease the level of stress that the society is exposed to. And, as we learn that it is not only "us" whose goals, rights and values are threatened, it is also a first step towards seeing "us" and "them" on a more equal basis. Deescalation oriented conflict coverage - as described in Figure 12 - will not yet release the society from the burden of war culture, nor will it transform the conflict into a cooperative process. But it is a first step away from seing "them" as the problem and from focusing on the question who prevails in war. And, if the media manage to implement such a less biased perception of the conflict, the maintainance of the societal beliefs about justness of own goals, positive self image, own victimization and deligitimizing the enemy will become less urgent for the society in order to cope with the conflict. As the exploration of the conflict formation draws a more complex picture of the conflict it does not yet release the society from being confronted with a seemingly unsolvable problem, but it might give rise to the idea that the simple solution that is offered by war and military logic is no solution at all. 2.2 Counterbalancing war and military logic

As the societal beliefs about security are put to the test, journalism must take care that their deconstruction will not leave a vacuum. Transformation of war culture into peace culture requires an active search for peaceful alternatives which is orthogonal to the antagonism between "us" and "them".

18

In order to accomplish this, solution oriented conflict coverage (cf. Figure 13), must replace the antagonistic understanding of peace as victory + cease-fire by a cooperative concept of peace as nonviolence + creativity. As a consequence, journalism has to change its focus in two aspects (cf. Galtung, 1998): - Traditional jounalism is more or less reactive, it heads to the conflict arena after violence has broken out and reports about those, who act in the conflict arena, mainly political and military lites. - Solution oriented journalism must report about conflicts before violence occurs and report about all segments of the society whose creativity might contribute to a peaceful transformation of the conflict. Accross to the distinction between "us" and "them", solution oriented coverage of conflicts will focus on shared interests of the war parties and on the benefit, that all sides could gain from ending war or violence. It will make the price visible, that all sides have to pay for war - even in case of victory. Giving voice to the voiceless, it will focus on suffering all over and also on the invisible effects of violence: trauma and glory, damage to structure and culture.

19

It will humanize all sides, but also give name to all evildoers. And it will redirect the indignation with the enemy against war and violence itself. Giving voice to the anti-war opposition, focusing not only on lite-mediators, but on peace-makers on the grassroot level also, high-lighting peace initiatives and signals of peace readiness, it will open perspectives for reconciliation.

20

2.3

Coverage of reconstruction and reconciliation

As journalism follows these guidelines, the conflict formation will become even more complex, but the society will gradually accumulate experience with alternatives to violence also. The importance of own goals and values will become less crucial and shared interests will come to the fore. The links between security and force will loosen, and open up a path on which's end - our positive self image will be based on more cooperative values, - victimization will no more draw a dividing line that seperates the parties, but a common memory that unifies them, and - yesterdays' deligitimized enemy will be seen as our own mirror image with comparable experiences of trauma and suffering. But the road to peace culture is long and stony. And in order to get there, there is a need that the processes of reconstruction and reconciliation are accompanied by the media as well. Maybe, this is one of the most crucial deficits of modern journalism: wherever violence breaks out, crowds of journalists head to the conflict arena, but us soon as violence is over, they lose interest and leave for another war, returning only if the old one flares up again. Stories of violence are regarded as "thrilling" while reconstruction and reconciliation are simply "no news". In this regard, journalists have to learn a lot, and once more it includes to redirect their attention from lites to ordinary people. - Do doubt, it is boring to read about political leaders shaking hands, signing contracts, or giving endless speeches filled with phrases of cooperation and mutual respect that nobody beliefs as long as war culture is still virolent. - But there is nothing more thrilling than to learn, how ordinary people, having suffered the atrocities of war, can manage to jump over their own shadow and try a new start. To the same degree that war culture still prevails, projects of reconstruction and iniciatives of reconciliation that really bring people together, are not acting in a space of harmony. - There is still the fears and uncertainties of those who are involved in the projects, and - to the same degree as war-culture still prevails, cooperation with the former enemy, might be regarded as betrayal and lack of patriotism by those who stay behind. At an early stage of the peace process the societal beliefs of patriotism, which generate attachment to the society or nation by propagating loyalty, love, care and sacrifice are likely to become an issue of conflicts within the society itself. If the media manage to cover these conflicts, following the same guidelines of orientation towards deescalation and resolution of conflicts as described before, they might

21

contribute to a public discourse, however, which gradually changes the beliefs of patriotism: - not in the direction of unloyality, or lack of love, care or sacrifice, - but towards a more constructive interpretation of national identity, which is not so much dominated by demarcation from others but by being included as equal partners within the international community. As the media give attention to these internal conflicts, they directly counteract the societal beliefs of unity, which refer to the importance of ignoring internal conflicts and disagreements in order to unite the forces in the face of the external threat. They reconstruct society as more pluralistic and thus add to the insight according to which societal life needs to be guided by democratic principles rather than camp mentality.

22

2.4

Resolving double-bind

The societal beliefs that must be deconstructed in order to manage the transition from war culture to peace culture include fundamental contradictions. First of all, the contradiction between - beliefs about security to be achieved by enduring antagonism and confronting the enemy, and - beliefs about peace as the ultimate desire of society. Second, the immanent contradiction on which enduring antagonism is based itself, and which - stimulates the society members' fighting spirit by portraying the enemy as dangerous and inhuman as possible, and - at the same time describes him as undangerous and human as necessary so that the members of society do not lose courage, are certain of victory, and do not get scared by the perspective of possible defeat. A prominent example of these immanent contradictions is the Cold War logic that legitimated the stationing of medium-range missiles and cruise missiles in Western Germany during the early eightees. Stressing the need to deter the "inhumanitarian Sovjet Union" from war, it simultaneously referred to the goodwill of the Sovjet Union (which was supposed to be interested in protecting Europe from destruction) as the only security guarantee which would prevent the nuclear armament race from resulting in the destruction of Central Europe (cf. Kempf, 1986). Contradictions like this are typical of war culture and interveave propaganda and traditional war reporting on all levels from the explanation of the logic of history (cf. Kempf, Reimann & Luostarinen, 1998) via the explanation of the conflict sources (cf. Elfner, 1998) and the evaluation of alternatives to violence (cf. Reimann, 1997a; Kempf & Reimann, in preparation) down to the coverage of day to day atrocities (cf. Kempf, Reimann & Luostarinen, 1996). War culture thus places the members of the society into a permanent double-bind situation, where they have to cope with contradictory messages and lack the chance either to react to both of the messages, or to withdraw from the situation. As a result of emotional involvement with both contradictory messages it becomes extremely difficult to query either of them. If society members have no access to independent information, they have no other chance than to believe the conclusions they are told by their political leaders or to withdraw into selective inattendance, prejudice or evasive sceptizism etc. - all of which are consequences that serve the goals of psychological warfare by paralysing the capacity for resistance against the war (cf. Kempf, 1992). Resolving this double bind situation by making the contradictions transparent that war culture produces is one of the most urgent tasks that journalism has to fulfil. It is one of the most difficult tasks also and can only be accomplished

23

by independent journalism which is not attached to either side in the conflict but only to peace and creativity. The local journalist, who reports from within a society that is involved in intractible conflict will not be able to do so without an analysis of - the societal beliefs that constitute war culture, and - the contradictions it generates. To make such an analysis available would be an important task for the international media, if only they could give up their habit of - either showing no interest in a the conflict at all, - or putting the question who are the "good" and who the "bad guys" and then to take sides and head for international intervention.

24

References

Bar-Tal, D., 1989. Delegitimization: the extreme case of stereotyping and prejudice. In: Bar-Tal, D., Graumann, C., Kuglanski, A.W., Stroebe, W. (Eds.). Stereotyping and prejudice: Changing conceptions. New York: Springer. Bar-Tal, D., 1996. Societal beliefs in times of intractable conflict: The Israeli case. Manuscript submitted for publication. Deutsch, M. 1976. Konfliktregelung. Mnchen: Reinhardt. Elfner, P., 1998. Darstellung der Konfliktursachen im Golfkrieg. Eine medienpsychologische Vergleichsstudie von Sddeutscher Zeitung und Washington Post. Universitt Konstanz: Psychol. Diplomarbeit. Galtung, J., 1997. Kriegsbilder und Bilder vom Frieden, oder: Wie wirkt diese Berichterstattung auf Konfliktrealitt und Konfliktbearbeitung. In: Callie, J. (Ed.). Das erste Opfer eines Krieges ist die Wahrheit, oder: Die Medien zwischen Kriegsberichterstattung und Friedensberichterstattung. Loccumer Protokolle 69/95. Galtung, J., 1998. Friedensjournalismus: Warum, was, wer, wo, wann? In: Kempf, W., Schmidt-Regener, I. (Eds.). Krieg, Nationalismus, Rassismus und die Medien. Mnster: Lit. Interiano, C., 1996. Comunicacion, Periodismo y Paz en Guatemala. Guatemala: Universidad de San Carlos. Kempf, W., 1986. Emotionalitt und Antiintellektualismus als Problem der Friedensbewegung? In: Evers, T., Kempf, W., Valtink, E. (Eds.). Sozialpsychologie des Friedens. Evangelische Akademie Hofgeismar: Protokoll 229/1986. Kempf, W., 1992. Guerra y medios de comunicacion: ruptura de lmites entre poltica informativa y tortura psicolgica. In: Riquelme, H. (Ed.). Otras realidades otras vas de acceso. Psicologa y psiquiatra transcultural en Amrica Latina. Caracas, Venezuela: Editorial Nueva Sociedad. Kempf, W., 1993. Konflikteskalation durch autonome Prozesse. In: Kempf, W., Frindte, W., Sommer, G., Spreiter, M. (Eds.). Gewaltfreie Konfliktlsungen. Heidelberg: Asanger. Kempf, W. 1996a Konfliktberichterstattung zwischen Eskalation und Deeskalation. Ein sozialpsychologisches Modell. Wissenschaft und Frieden, 2/96: 51-54. Kempf, W. 1996b. Gulf War revisited. A comparative study of the Gulf War coverage in American and European media. Diskussionsbeitrge der Projektgruppe Friedensforschung Konstanz Nr. 34/1996. Online: http://www.uni-konstanz.de/ ZE/Bib/vv/wra/kempf/psyclist.htm Kempf, W., 1997. Media coverage of third party peace initiatives - a case of peace journalism? Diskussionsbeitrge der Projektgruppe Friedensforschung Konstanz Nr. 37/1997. Online: http://www.unikonstanz.de/ ZE/Bib/vv/wra/kempf/psyclist.htm Kempf, W., 1998. News media and conflict escalation - a comparative study of the Gulf War coverage in American and European media. In: Nohrstedt, S.A., Ottosen, R. (Ed). Journalism in the New World Order. Vol. I. Gulf War, National News Discourses and Globalization. London: Sage (in print). Kempf, W., in preparation. Escalation and deescalation oriented elements in the coverage of the Bosnia conflict. In: Kempf, W., Luostarinen, H. (Eds.). Journalism in the New World Order. Vol. II. Studying war and the media. London: Sage (forthcoming). Kempf, W., Reimann, M., in preparation. The presentation of alternative ways to settle the Gulf conflict in German, Norwegian and Finnish media. In: Kempf, W., Luostarinen, H. (Eds.). Journalism in the New World Order. Vol. II. Studying war and the media. London: Sage (forthcoming). Kempf, W., Reimann, M., Luostarinen, H., 1996. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse von Kriegspropaganda und Kritischem Friedensjournalismus. Diskussionsbeitrge der Projektgruppe Friedensforschung Konstanz, Nr. 32. Online: http://www.uni-konstanz.de/ZE/Bib/vv/wra/kempf/psyclist.htm

25

Kempf, W., Reimann, M., Luostarinen, H., 1998. New World Order rhetorics in American and European media. In: Nohrstedt, S.A., Ottosen, R. (Ed). Journalism in the New World Order. Vol. I. Gulf War, National News Discourses and Globalization. London: Sage (in print). Knightley, P. 1975. The first casuality. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Kunczik, M., 1990. Die manipulierte Meinung. Nationale Image-Politik und internationale Public Relations. Kln: Bhlau. Lasswell, H.D., 1927. Propaganda Technique in the World War. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Luostarinen, H., 1986. Perivihollinen (The Ancient Foe). Tampere: Vastapaino. MacArthur, J.R., 1993. Die Schlacht der Lgen. Mnchen: dtv. Martin-Bar, I., 1991. Die psychischen Wunden der Gewalt. In: Kempf, W. (Ed.). Verdeckte Gewalt. Psychosoziale Folgen der Kriegsfhrung niedriger Intensitt in Zentralamerika. Hamburg: Argument. Reimann, M., 1997a. Alternative Konfliktlsungsoptionen im Golfkrieg. Eine qualitative Inhaltsanalyse deutscher Medien (1990-1993). Diskussionsbeitrge der Projektgruppe Friedensforschung Konstanz, Nr. 36/1997. Online: http:// www.unikonstanz.de/ZE/Bib/vv/wra/kempf/psyclist.htm Reimann, M., 1997b. Two-sided messages and double bind communication in war reporting. Diskussionsbeitrge der Projektgruppe Friedensforschung Konstanz, Nr. 38/1997. Online: http://www.unikonstanz.de/ZE/Bib/vv/wra/kempf/ psyclist.htm

Você também pode gostar

- Citizen Journalism, Editorial Writing, Cartooning and Media BroadcastingDocumento19 páginasCitizen Journalism, Editorial Writing, Cartooning and Media BroadcastingClark Dominic L AlipasaAinda não há avaliações

- Group Conflicts and Group Decision MakingDocumento7 páginasGroup Conflicts and Group Decision MakingPrathamesh DeoAinda não há avaliações

- War Propaganda and The Media - Anup ShahDocumento12 páginasWar Propaganda and The Media - Anup ShahGennara AlfonsoAinda não há avaliações

- How To Contact The MediaDocumento5 páginasHow To Contact The MediagebbiepressAinda não há avaliações

- Media Framing and Social Movement MobilizationDocumento44 páginasMedia Framing and Social Movement MobilizationAnastasiia GnatenkoAinda não há avaliações

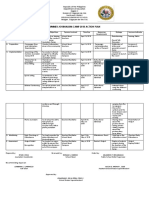

- Action Plan and Journalism Training MatrixDocumento5 páginasAction Plan and Journalism Training Matrixryeroe100% (2)

- Powering to Peace: Integrated Civil Resistance and Peacebuilding StrategiesNo EverandPowering to Peace: Integrated Civil Resistance and Peacebuilding StrategiesAinda não há avaliações

- Sample Session GuideDocumento6 páginasSample Session GuideANA LYN NANOL100% (1)

- ConflictDocumento20 páginasConflictEno G. Odia100% (1)

- Masters of AdvertisingDocumento348 páginasMasters of AdvertisingWilliam TsediAinda não há avaliações

- Conceptualizing Peace & Conflict CyclesDocumento18 páginasConceptualizing Peace & Conflict CyclesPrincess Oria-ArebunAinda não há avaliações

- Journalism & Professional EthicsDocumento11 páginasJournalism & Professional EthicsBlunch4EvaAinda não há avaliações

- Campus Journalism SyllabusDocumento7 páginasCampus Journalism SyllabusAisa karatuanAinda não há avaliações

- Marin, Micah Daniella: TH TH THDocumento4 páginasMarin, Micah Daniella: TH TH THMicah MarinAinda não há avaliações

- War & PeaceDocumento11 páginasWar & PeaceAhmad NaqiuddinAinda não há avaliações

- Assessing The Impact of Coherence-Creating Groups On The Lebanon War - John L DaviesDocumento12 páginasAssessing The Impact of Coherence-Creating Groups On The Lebanon War - John L DaviesAMTRAinda não há avaliações

- Kiss - Strategic Communications enDocumento23 páginasKiss - Strategic Communications enpeterakissAinda não há avaliações

- Kempf 2008 Peace JournalismDocumento8 páginasKempf 2008 Peace Journalismtamar3Ainda não há avaliações

- Media and PeacebuildingDocumento23 páginasMedia and Peacebuildingayoub addiAinda não há avaliações

- Media Ethics and Conflict Reporting - Indo-Pak Conflict and TheDocumento9 páginasMedia Ethics and Conflict Reporting - Indo-Pak Conflict and TheAnil MishraAinda não há avaliações

- Kriesberg - Sociology of Social ConflictsDocumento203 páginasKriesberg - Sociology of Social Conflictsannamar07100% (1)

- Conflict Reporting and Peace Journalism: in Search of A New Model: Lessons From The Nigerian Niger-Delta CrisisDocumento22 páginasConflict Reporting and Peace Journalism: in Search of A New Model: Lessons From The Nigerian Niger-Delta CrisisAnthony Sasu AyisaduAinda não há avaliações

- MALUYA, Gwyneth Assignment#2Documento3 páginasMALUYA, Gwyneth Assignment#2Maluya GwynethAinda não há avaliações

- Three Pillars of Counterinsurgency DoctrineDocumento8 páginasThree Pillars of Counterinsurgency DoctrineAsfandyar DurraniAinda não há avaliações

- Media - Peace Journalism - War JournalismDocumento21 páginasMedia - Peace Journalism - War JournalismNasima JuiAinda não há avaliações

- Thinking About Peace Today Allen FoxDocumento23 páginasThinking About Peace Today Allen FoxAuteurphiliaAinda não há avaliações

- Peace and ConflictDocumento21 páginasPeace and ConflictMuhammad AuwalAinda não há avaliações

- Types & Levels of ConflictDocumento11 páginasTypes & Levels of ConflictNeelakshi TomarAinda não há avaliações

- PEACE RESEARCH MOVEMENTSDocumento15 páginasPEACE RESEARCH MOVEMENTSHarsheen SidanaAinda não há avaliações

- Course Title: Issues in Peace and Conflict Course Code: GSP 202 Continuous Assessment Questions Answer All The QuestionsDocumento10 páginasCourse Title: Issues in Peace and Conflict Course Code: GSP 202 Continuous Assessment Questions Answer All The QuestionsHenry OssaiAinda não há avaliações

- Unit Peace Research and Peace Movements: StructureDocumento17 páginasUnit Peace Research and Peace Movements: StructureNeha GautamAinda não há avaliações

- Conflict Management Methods GuideDocumento8 páginasConflict Management Methods GuideFranz JosephAinda não há avaliações

- Understanding Assumptions in Conflict ResolutionDocumento15 páginasUnderstanding Assumptions in Conflict ResolutionClaudia WPAinda não há avaliações

- EJC111753Documento5 páginasEJC111753princess catherine PabellanoAinda não há avaliações

- Invention of Peace:: Reflections On War and International OrderDocumento23 páginasInvention of Peace:: Reflections On War and International OrderShan Brave TupasAinda não há avaliações

- The Logic of Violence in Civil War: Theory and Preliminary ResultsDocumento46 páginasThe Logic of Violence in Civil War: Theory and Preliminary ResultsMaría Angélica NietoAinda não há avaliações

- Small Wars Journal: Azriel PeskowitzDocumento13 páginasSmall Wars Journal: Azriel PeskowitzbfishmanAinda não há avaliações

- Feud and Internal War - Legal AspectsDocumento4 páginasFeud and Internal War - Legal AspectsJacobin ParcelleAinda não há avaliações

- Exam NaomieDocumento7 páginasExam NaomieJob SitatiAinda não há avaliações

- Countering Asymmetrical Warfare in The 21st Century: A Grand Strategic VisionDocumento9 páginasCountering Asymmetrical Warfare in The 21st Century: A Grand Strategic VisionWaleed Bin Mosam KhattakAinda não há avaliações

- The Nature of Peace and Its Implications ForDocumento7 páginasThe Nature of Peace and Its Implications ForMamush kasimoAinda não há avaliações

- Essays on Civil War, Inequality and UnderdevelopmentNo EverandEssays on Civil War, Inequality and UnderdevelopmentAinda não há avaliações

- Week3 - The Concept of CRDocumento29 páginasWeek3 - The Concept of CRİrem ÇakırAinda não há avaliações

- Techo Sen School of Government and International Relations Ph.D. in International RelationsDocumento10 páginasTecho Sen School of Government and International Relations Ph.D. in International RelationsMatta KongAinda não há avaliações

- Who Collective ViolenceDocumento28 páginasWho Collective ViolenceZoha khanamAinda não há avaliações

- A Criticism of Realism Theory of International Politics Politics EssayDocumento5 páginasA Criticism of Realism Theory of International Politics Politics Essayain_94Ainda não há avaliações

- Causesofwar 151021094306 Lva1 App6892Documento26 páginasCausesofwar 151021094306 Lva1 App6892Anne Mel BariquitAinda não há avaliações

- Internationa L Relations: Saint Patrick's SchoolDocumento11 páginasInternationa L Relations: Saint Patrick's Schooldante fioraniAinda não há avaliações

- Conflict and DevelopmentDocumento11 páginasConflict and DevelopmentWeleilakeba Sala LeiAinda não há avaliações

- Nancy,+2.4 Fifth-Generation+WarfareDocumento14 páginasNancy,+2.4 Fifth-Generation+WarfareRhey XDAinda não há avaliações

- War and Peace International RelationsDocumento4 páginasWar and Peace International RelationsBelle Reese PardilloAinda não há avaliações

- Media's Role in Conflict: War vs Peace JournalismDocumento2 páginasMedia's Role in Conflict: War vs Peace JournalismReen SFAinda não há avaliações

- Collective Violence and Group Solidarity - Evidence From A Feuding Society Author(s) - Roger V. GouldDocumento26 páginasCollective Violence and Group Solidarity - Evidence From A Feuding Society Author(s) - Roger V. GouldnandirewaAinda não há avaliações

- Reconciliation As A Foundation of Culture of Peace: Daniel Bar-TalDocumento2 páginasReconciliation As A Foundation of Culture of Peace: Daniel Bar-TalDDiego HHernandezAinda não há avaliações

- Types of modern conflicts and resolution optionsDocumento3 páginasTypes of modern conflicts and resolution optionsAlice CooperAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 11 Conflict Management and Conflict Resolution: StructureDocumento8 páginasUnit 11 Conflict Management and Conflict Resolution: StructuremireilleAinda não há avaliações

- 1.introduction To ConflictDocumento15 páginas1.introduction To ConflicttamaraAinda não há avaliações

- Conceptualizing War, Terrorism and International RelationsDocumento10 páginasConceptualizing War, Terrorism and International RelationsAyatullah TahsanAinda não há avaliações

- 20092010HumanSecurityReport Part1 CausesOfPeaceDocumento92 páginas20092010HumanSecurityReport Part1 CausesOfPeaceRazvan DanielAinda não há avaliações

- Complete GST 202 Note (Afolabi Abdulahi Olajide y X)Documento70 páginasComplete GST 202 Note (Afolabi Abdulahi Olajide y X)israelkolawole599Ainda não há avaliações

- Possible and Impossible Solutions To Ethnic Civil WarsDocumento41 páginasPossible and Impossible Solutions To Ethnic Civil WarsElizabethAinda não há avaliações

- GST 211 Federal UniversityDocumento29 páginasGST 211 Federal Universityjohn peter100% (1)

- An Overview of International ConflictDocumento20 páginasAn Overview of International Conflictdanalexandru2Ainda não há avaliações

- Lesson 1 - Key Concepts of Conflict-Sensitive JournalismDocumento6 páginasLesson 1 - Key Concepts of Conflict-Sensitive JournalismCha D.CAinda não há avaliações

- Ethiopia Conflict Profile: Political, Religious, Ethnic IssuesDocumento20 páginasEthiopia Conflict Profile: Political, Religious, Ethnic IssuesTadege TeshomeAinda não há avaliações

- Violent Peace: Militarized Interstate Bargaining in Latin AmericaNo EverandViolent Peace: Militarized Interstate Bargaining in Latin AmericaAinda não há avaliações

- Glosario de Formas de ProtestaDocumento17 páginasGlosario de Formas de ProtestaJuan David CárdenasAinda não há avaliações

- Social Movements: Ritual, Space and MediaDocumento17 páginasSocial Movements: Ritual, Space and MediaJuan David CárdenasAinda não há avaliações

- Alexa Robertson (Editor) - Screening Protest - Visual Narratives of Dissent Across Time, Space and Genre (2018, Routledge) - Libgen - LiDocumento283 páginasAlexa Robertson (Editor) - Screening Protest - Visual Narratives of Dissent Across Time, Space and Genre (2018, Routledge) - Libgen - LiJuan David CárdenasAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter Six - Memory Social Media Bartoletti-With-Cover-PageDocumento25 páginasChapter Six - Memory Social Media Bartoletti-With-Cover-PageJuan David CárdenasAinda não há avaliações

- The Interdependency of Mass Media and Social MovemDocumento29 páginasThe Interdependency of Mass Media and Social MovemJuan David CárdenasAinda não há avaliações

- Colombia Otros 100 Años de Soledad-James RobinsonDocumento6 páginasColombia Otros 100 Años de Soledad-James RobinsonJuan David Cárdenas100% (1)

- WV6 Official Questionnaire v4 June2012Documento21 páginasWV6 Official Questionnaire v4 June2012Juan David CárdenasAinda não há avaliações

- Publicidad Politica y PersuasionDocumento27 páginasPublicidad Politica y PersuasionJuan David CárdenasAinda não há avaliações

- City BrandingDocumento13 páginasCity BrandingJuan David CárdenasAinda não há avaliações

- Comunicacion Politica y TelevisionDocumento8 páginasComunicacion Politica y TelevisionJuan David CárdenasAinda não há avaliações

- 423202Documento14 páginas423202Juan David CárdenasAinda não há avaliações

- PDFSig QFormal RepDocumento1 páginaPDFSig QFormal RepcarloschmAinda não há avaliações

- Escala Traducida SwansonDocumento1 páginaEscala Traducida SwansonJuan David CárdenasAinda não há avaliações

- Television - Pierre BourdieuDocumento16 páginasTelevision - Pierre BourdieuJørn BoisenAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 2 - Reading MaterialDocumento14 páginasChapter 2 - Reading MaterialPRINCESS JOY BUSTILLOAinda não há avaliações

- Ethical Issues in Journalism and The Media PDFDocumento2 páginasEthical Issues in Journalism and The Media PDFVijay100% (1)

- Russian Federation Anti-Gay-LawsDocumento129 páginasRussian Federation Anti-Gay-LawsTheBladi11Ainda não há avaliações

- DSPC 2023 MemoDocumento16 páginasDSPC 2023 MemoPaulo MoralesAinda não há avaliações

- Professional Ethics and ResponsibilitiesDocumento21 páginasProfessional Ethics and ResponsibilitiesJohn Donnovan CalingAinda não há avaliações

- News and News Sources n3Documento21 páginasNews and News Sources n3Trisha YadavAinda não há avaliações

- Content Analysis of Newspapers & Periodicals FormatsDocumento2 páginasContent Analysis of Newspapers & Periodicals FormatsshainaAinda não há avaliações

- Source of News in Journalism Radio, TV, Newspapers & MagazinesDocumento12 páginasSource of News in Journalism Radio, TV, Newspapers & MagazinesRaquel LimboAinda não há avaliações

- Writing and Reporting For The Media Workbook 12Th Edition Full ChapterDocumento32 páginasWriting and Reporting For The Media Workbook 12Th Edition Full Chapterdorothy.todd224100% (23)

- Literature ReviewDocumento8 páginasLiterature ReviewR. YashwanthiniAinda não há avaliações

- English Language Newspapers and Magazines in UkraineDocumento11 páginasEnglish Language Newspapers and Magazines in UkraineАліна Андріївна ЩербінінаAinda não há avaliações

- 2004 - Complete Narrative ReportDocumento40 páginas2004 - Complete Narrative Reportapi-3718467100% (1)

- The Importance of Radio: Read The Text Very CarefullyDocumento6 páginasThe Importance of Radio: Read The Text Very CarefullyDaniela FerreiraAinda não há avaliações

- BA (Hons.) Journalism Syllabus 2011Documento71 páginasBA (Hons.) Journalism Syllabus 2011Nupur BhutaniAinda não há avaliações

- Unisite Subdivision, Del Pilar, City of San Fernando, 2000 Pampanga, PhilippinesDocumento15 páginasUnisite Subdivision, Del Pilar, City of San Fernando, 2000 Pampanga, PhilippinesCris RealAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 1Documento16 páginasUnit 1Arshpreet KaurAinda não há avaliações

- New Final Mass Communication and Journalism in IndiaDocumento103 páginasNew Final Mass Communication and Journalism in IndiaNSDC AddonsAinda não há avaliações

- Finding Reasons Why Research Is Important Seems Like A NoDocumento8 páginasFinding Reasons Why Research Is Important Seems Like A NoPaul John Garcia RaciAinda não há avaliações

- Globalization Impact On Online JournalismDocumento12 páginasGlobalization Impact On Online Journalismismail_su61100% (1)

- GOMES ITANIA Testemunha Vivência e As Atuações Do Repórter Na TV BrasileiraDocumento18 páginasGOMES ITANIA Testemunha Vivência e As Atuações Do Repórter Na TV BrasileiraElton AntunesAinda não há avaliações

- Music, Journalism, and The Study of Cultural Change: February 2012Documento10 páginasMusic, Journalism, and The Study of Cultural Change: February 2012Fernando Alayo OrbegozoAinda não há avaliações

- Newspaper VocabularyDocumento6 páginasNewspaper VocabularyClifford FloresAinda não há avaliações