Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Tobacco 12 Effort Education

Enviado por

Eliza DNDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Tobacco 12 Effort Education

Enviado por

Eliza DNDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Association Report

Tobacco Control and Prevention Effort in Dental Education

Richard G. Weaver, D.D.S.; Lynn Whittaker, M.A.; Richard W. Valachovic, D.M.D., M.P.H.; Angela Broom, J.D.

Dr. Weaver is Associate Director, Center for Educational Policy and Research; Ms. Whittaker is Managing Editor; Dr. Valachovic is Executive Director; and Ms. Broom is Associate Executive Director and General Counsel, all at the American Dental Education Association. Direct correspondence to Angela Broom, American Dental Education Association, 1625 Massachusetts Ave., NW, Washington, DC 20036; 202-667-9433 phone; 202-667-0642 fax; brooma@adea.org.

or decades, public health advocates have been sending a clear message: tobacco use in any form is harmful. The adverse health effects of tobacco use have been thoroughly documented, including the fact that tobacco-related mortality may be the most preventable cause of death in America today. Experts say that one person dies from oral cancer every hour, and thats only one affected area. Nevertheless, more people start and others continue to use tobacco every day, harming themselves and those around them. A complex web of motivations and addictions drives each individual who refuses to heed the warnings, but the question for the health professions is this: What concrete steps can we take to help smokers and other tobacco users quit and to discourage nonusers from ever starting? Members of the dental profession have been pondering this question for a long time, for they are responsible for the oral health of their patients and, every day, they see dramatic evidence of the damage tobacco does. They know that more than 90 percent of cancers affecting the mouth, tongue, lips, throat, larynx, and pharynx are attributed to tobacco use; the use of tobacco products is the greatest preventable contributor to oral and pharyngeal cancers and the suffering and death these cancers cause; the odds of beating oral cancer increase dramatically with early detection: more than 81 percent diagnosed early have a five-year survival rate, while only 21 percent diagnosed with advanced oral cancer are alive five years later; and

aside from cancer, tobacco use raises the likelihood of periodontal disease, can cause halitosis, reduced ability to taste, staining of the teeth, gingival pigmentation, and oral mucosal lesions, and increases the risk of fetal abnormalities among women who smoke during pregnancy. Unlike dental professionals, the general public knows very little about the risks of oral cancer, and most early signs are difficult for a layperson to detect. However, more than 50 percent of smokers see a dentist each year. These elements make it clear that dentists and dental educators have significant opportunities to bring about positive change in this vital area of public health. As a result, the American Dental Education Association (ADEA), with funding support from the American Legacy Foundation, launched a Tobacco Control Project in June 2001. This initiative is meant to assist dental academic institutions as they train dental students in tobacco prevention and cessation and provide smoking cessation counseling to patients in their clinics. In support of that goal, this report presents information from a survey the Association conducted in August 2001 about tobacco prevention and cessation in the fifty-four dental academic institutions in the United States. It provides an overview of what those institutions have accomplished to help reduce tobacco use among the American public and examines what else they can achieve if existing barriers are removed.

426

Journal of Dental Education Volume 66, No. 3

Dental Educators Accomplishments in Tobacco Intervention

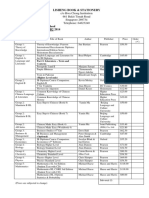

Tobacco control intervention takes two forms: preventing individuals from starting to smoke or use other tobacco products, and helping current users to stop. The ADEA survey demonstrates that dental educators believe they have a role in both prevention which involves patient educationand cessation which involves counseling. Fulfilling these roles means, primarily, making sure that when students at those schools graduate and go on to professional practice, they do so with the knowledge and confidence they need to educate and counsel their patients. The commitment of schools to this aspect of educating their students is an impressive accomplishment. Currently, forty-five of the fifty-four schools surveyed report that they include instruction in tobacco prevention in their curricula, and forty-four include instruction in tobacco cessation. Furthermore, forty-one of the schools say that they provide materials to their students on tobacco control, use, prevention, and cessation. The scope of this effort is not quite as widespread as other more basic tobacco-related aspects of the dental curriculum. Detection of tobacco-related pathology like oral cancer is included in the curriculum of all but one school, for example, and treatment of tobacco-related pathology in all but three. Still, the scope of prevention and cessation instruction is notablespanning the scope of the educational experience. Schools reported in the survey that they provide tobacco prevention and cessation information in many parts of the curriculum, ranging from oral medicine, to oral pathology, to prevention, to diagnosis and treatment planning. The dental schools commitment to prevention and cessation is also evident in their practices toward patients who attend their clinics. Fifty-two of the fifty-four say they include tobacco use evaluation in their patient history and examination process. Fifty-one schools say they make referrals for patients with tobacco-related pathology. These are also significant accomplishments. Clearly, the schools are devoting a great deal of effort to informing their students and patients about tobacco-cessation medications. Forty-one schools say they provide information on both the nicotine patch

and nicotine gum; twenty-seven do so on the nicotine inhaler; twenty-five on nicotine nasal spray; twenty-seven on Bupropion SR; ten on Clonidine; and seven on Nortiptyline. In yet another significant accomplishment, the survey reveals that many schools of dental medicine have entered into cooperative programs in several venues that promote tobacco control. Twenty-six schools say they have participated in programs that are focused on oral cancer, and twenty-five have participated in community-based programs. Twenty report participating in multidisciplinary programs, while eleven have done so as part of a consortium. Finally, schools report that they are using a wide variety of means to evaluate their tobacco program/ course offerings. Some use the usual curriculum review process, including evaluations by students, faculty, course directors, and in some cases by a curriculum committee. Some also survey patients in their clinics, and at least one has conducted a survey of its postgraduates. The students who have taken the courses are evaluated in a variety of ways to make sure they are benefiting from the instruction; these methods of evaluation range from written examinations, group papers, and presentations to clinical assessments and online quizzes.

Barriers to Expanded Efforts

For all of the schools accomplishments in preparing students to intervene in their patients tobacco use and to implement tobacco programs in their clinics, the need and the opportunity to do more are apparent. The ADEA survey also helped to identify the barriers schools face to expanding their efforts and provide clues about what is needed to remove those barriers. Regarding schools willingness to provide patient counseling on tobacco use and cessation in clinics, several factors were named as important. Thirtysix of the schools said time constraints were a significant factor in providing this service, but thirtythree said lack of training was also important and twenty-three identified lack of reimbursement as a factor. Patient sensitivities were mentioned as a factor by only fourteen schools. In the option for Other reasons provided in the survey, schools mentioned several factors as having an impact on the willingness to provide counseling. These included Student/ faculty perceived ability to be successful, Patient

March 2002

Journal of Dental Education

427

understanding that dentists can provide cessation and counseling, Faculty resources, Curriculum constraints, Patient resources, Student priorities, and Lack of faculty reinforcement. Regarding the preparation of students, schools said that the primary factor affecting tobacco training in their course offerings was Allotting course time. This factor was identified by forty-two of the fifty-four schools. Another eleven schools selected Lack of materials as a factor. Only four named Student disinterest. This last item is particularly important as it demonstrates clearly that students want to receive tobacco training. Two additional areas appear to be barriers to schools programs. The first was revealed in the survey questions regarding faculty training. An overwhelming fifty of the fifty-four schools answered yes to the question Is there a need for faculty training on cessation techniques? Nearly as many schoolsforty-nine of the fifty-foursaid they had a need for faculty training on tobacco prevention techniques as well. And thirty-nine schools also said they needed faculty training on the oral health risks to patients who use tobacco products. Considering the key role the schools faculty play in teaching students about tobacco cessation, prevention, and risks, the need for additional faculty preparation in these areas appears to be acute. A second, and related, key barrier is related to funding needs. Only seventeen of the schools responded that they had ever applied for a grant to develop a substance abuse curriculum, all of which included tobacco prevention and cessation. Only eleven of the seventeen received funding. Most dramatically, forty-nine of the fifty-four schools said they would be interested in applying for tobacco prevention and cessation funding. It is equally revealing, however, that only twenty-seven of those said they were aware of available sources of funding. Finally, the survey reveals that schools do not appear to be doing as much as they could to help redress the racial and ethnic disparity in oral healthcare as it pertains to tobacco use. While 38 percent of whites are diagnosed early with oral cancers, when it is most treatable, for example, only 19 percent of blacks receive an early diagnosis. As a result, oral cancer is the seventh most common cancer in white males, but the fourth most common cancer among black men. In spite of these disparities and the commitment of the dental profession to providing equal access to trained professionals for people

of all racial and ethnic groups, only eleven of the fifty-four dental schools reported in the survey that they include in their tobacco control curriculum material that is focused on specific ethnic/racial groups. In fact, training for working with any particular group appears to be limited: only eleven of the schools say that they include gender-specific training, and thirteen say they include training in multigenerational patients (pediatric vs. geriatric).

Action Steps to Help Overcome the Barriers

The accomplishments of dental academic institutions regarding tobacco programs are impressive, as the survey has shown. Yet, the need for dental professionals to play a larger role in addressing tobaccorelated aspects of public health is significant. Dental faculty and students have shown a strong desire to improve their ability to do so, just as schools have demonstrated a clear interest in having their instructors trained and expanding their course offerings. To help them do so, attention must be paid to removing whatever barriers remain. Regarding preparation of students, one of the primary barriers is time constraints in the curriculum. Trying to fit more and more content into an already crowded curriculum is a persistent challenge in every type of professional training, indeed in every aspect of education, and will not be resolved easily. But two action steps may help: 1. Provide schools with examples of how other schools have successfully addressed the problem. These examples can serve as models to follow and will provide ideas that may be applied or adapted for use in their own schools. 2. Continue to emphasize the importance of making a place in the curriculum for tobacco-related education. As dental educators are reminded of the key role of their profession in addressing this public health problem, they will appreciate that the extra effort involved is worthwhile. Another primary barrier involves the need identified by schools for training to prepare faculty to teach students about oral health risks of tobacco as well as prevention and cessation techniques. This is the critical first link in the educational chain that starts with the faculty and moves on to students and, finally, the patients those students attend to when they

428

Journal of Dental Education Volume 66, No. 3

become new dentists. Two action steps are needed to assist dental schools in getting their faculty up to speed in these areas: 3. Provide schools with examples of how other schools have successfully addressed the problem. As with the curriculum barrier, examples can serve as models or at least sources of ideas. 4. Encourage cooperative means for faculty development across the profession. These might include workshops at annual professional conventions, special training conferences held at a school with experience and expertise in the topic, collaborative efforts involving several schools in a region, or web-based or other electronic training programs. With the finances of all schools already strained, adding new training and curriculum content may well require funds that schools simply dont have. An additional action step can help with this barrier: 5. Provide assistance to schools in identifying sources of funding and preparing grant applications for funds to support new curricular and training needs.

And finally, as schools are being encouraged to do more to help ensure equal access to dental care and tobacco control for all racial and ethnic groups and to provide care in a way that is sensitive to the needs of different genders, ages, and racial and ethnic groups, a final action step is advisable: 6. Help dental schools better prepare their students to serve their patients in all possible groups by including training focused on these areas in the curriculum. Models of successful programs can help, as can training modules. Working together, the entire dental education community can make a difference in reducing tobacco use among the American public and ultimately in saving lives.

Acknowledgments

ADEA expresses deep appreciation to GlaxoSmithKline Corporation for its generous sponsorship of the printing and wider dissemination of this report to the dental education community. We also thank the American Legacy Foundation for a grant making the survey of all U.S. dental schools possible.

March 2002

Journal of Dental Education

429

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Radiological Patterns of Lung Involvement in Inflammatory Bowel Disease.Documento10 páginasRadiological Patterns of Lung Involvement in Inflammatory Bowel Disease.Eliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Supplementary File Survey Question Response OptionsDocumento3 páginasSupplementary File Survey Question Response OptionsEliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- 2018 Korean Clinical Imaging Guideline For HemoptysisDocumento6 páginas2018 Korean Clinical Imaging Guideline For HemoptysisEliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Smoking Resumption After Heart or Lung TransplantationDocumento10 páginasSmoking Resumption After Heart or Lung TransplantationEliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Health Risks and How To Quit (PDQ®)Documento20 páginasHealth Risks and How To Quit (PDQ®)Eliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Treatments For ConstipationDocumento27 páginasTreatments For ConstipationEliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Acs 33 233Documento8 páginasAcs 33 233Eliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Dental Public Health MSCDocumento4 páginasDental Public Health MSCEliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- Orh cdh21-4 P1to11Documento11 páginasOrh cdh21-4 P1to11Eliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- Interdisciplinary Culture FinalDocumento3 páginasInterdisciplinary Culture FinalEliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- Modified Reasons For Smoking ScalDocumento7 páginasModified Reasons For Smoking ScalEliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Oral Health Inequalities PolicyDocumento13 páginasOral Health Inequalities PolicyEliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- 2008 NOHC - JPHDSupplementDocumento62 páginas2008 NOHC - JPHDSupplementEliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Understanding Inequalities of Maternal Smoking-Bridging The Gap With Adapted Intervention StrategiesDocumento16 páginasUnderstanding Inequalities of Maternal Smoking-Bridging The Gap With Adapted Intervention StrategiesEliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- Alpha Amylase StressDocumento10 páginasAlpha Amylase StressEliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- An Updated Review of Case-Control Studies of Lung Cancer and Indoor Radon-Is Indoor Radon The Risk Factor For Lung Cancer?Documento9 páginasAn Updated Review of Case-Control Studies of Lung Cancer and Indoor Radon-Is Indoor Radon The Risk Factor For Lung Cancer?Eliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- Optimal Management of Collagenous Colitis A Review 021016Documento9 páginasOptimal Management of Collagenous Colitis A Review 021016Eliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 10global Hazards of Tobacco and The Benefits of Smoking Cessation and Tobacco TaxesDocumento363 páginasChapter 10global Hazards of Tobacco and The Benefits of Smoking Cessation and Tobacco TaxesEliza DN100% (1)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- InTech-Physiological Response As Biomarkers of Adverse Effects of The Psychosocial Work EnvironmentDocumento17 páginasInTech-Physiological Response As Biomarkers of Adverse Effects of The Psychosocial Work EnvironmentEliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Wirth Et Al 2011 PnecDocumento10 páginasWirth Et Al 2011 PnecEliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- Scand J Work Environ Health:310-318 Doi:10.5271/sjweh.3334: Original ArticleDocumento10 páginasScand J Work Environ Health:310-318 Doi:10.5271/sjweh.3334: Original ArticleEliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- DambrunRicardetal2012 MeasuringHappinessDocumento11 páginasDambrunRicardetal2012 MeasuringHappinessEliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- Hansen Review CortisolDocumento12 páginasHansen Review CortisolEliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- Nater & Rohleder-sAA & SNS-PNEC 09Documento11 páginasNater & Rohleder-sAA & SNS-PNEC 09Eliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- KoreaDocumento7 páginasKoreaEliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- PerfectionismDocumento7 páginasPerfectionismEliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- Cognitiive Emotion RegulationDocumento6 páginasCognitiive Emotion RegulationEliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- Amilaza FearDocumento3 páginasAmilaza FearEliza DNAinda não há avaliações

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Res Gaz11 A21Documento952 páginasRes Gaz11 A21UsamaAinda não há avaliações

- DLP On TimeDocumento6 páginasDLP On Timeshiela mae zolina100% (2)

- Assessment StrategiesDocumento11 páginasAssessment StrategiesPinky Mariel Mangaya100% (1)

- Course Outline in Grade 2 MapehDocumento3 páginasCourse Outline in Grade 2 MapehRoselyn GutasAinda não há avaliações

- Standard Six Reading Program RationaleDocumento1 páginaStandard Six Reading Program Rationaleapi-278580587Ainda não há avaliações

- Handout - Global Education and Global TeacherDocumento3 páginasHandout - Global Education and Global TeacherJuan Patricayo100% (1)

- Basta Mao NaniDocumento20 páginasBasta Mao NaniJim Ashter Laude SalogaolAinda não há avaliações

- What Makes Continuing Education Effective PerspectDocumento6 páginasWhat Makes Continuing Education Effective PerspecttestAinda não há avaliações

- 15-Item Quiz BeeDocumento5 páginas15-Item Quiz BeeKRISTINE NICOLLE DANAAinda não há avaliações

- 1968 Patchogue-Medford High Yearbook - Part 3 - Senior Memories and Ads, Also Entire 1967-68 Class Roster Including Non-GradsDocumento76 páginas1968 Patchogue-Medford High Yearbook - Part 3 - Senior Memories and Ads, Also Entire 1967-68 Class Roster Including Non-GradsJoseph ReinckensAinda não há avaliações

- AFMS NEET PG 20 NotificationDocumento20 páginasAFMS NEET PG 20 NotificationSuryaAinda não há avaliações

- Solving Problems Involving Systems of Linear InequalitiesDocumento11 páginasSolving Problems Involving Systems of Linear InequalitieskiahjessieAinda não há avaliações

- ANC12086 Pallvi SHARMA - BSBADM504 - Assessment Task 2Documento3 páginasANC12086 Pallvi SHARMA - BSBADM504 - Assessment Task 2Anzel AnzelAinda não há avaliações

- The Coddling of The American MindDocumento12 páginasThe Coddling of The American MindChristopher Paquette97% (32)

- Going Commercial For A Cause: Budget Benefits For Notre DameDocumento8 páginasGoing Commercial For A Cause: Budget Benefits For Notre Damethe University of Notre Dame AustraliaAinda não há avaliações

- Category 5 4 3 2 1: Graffiti Wall Group GraphicDocumento1 páginaCategory 5 4 3 2 1: Graffiti Wall Group GraphiccarofrancoeAinda não há avaliações

- Reading MathematicsDocumento110 páginasReading MathematicsLaili LeliAinda não há avaliações

- Cuban Government Scholarships 2024Documento2 páginasCuban Government Scholarships 2024முஹம்மது றினோஸ்Ainda não há avaliações

- Strategy NotebookDocumento17 páginasStrategy Notebookapi-548153301Ainda não há avaliações

- Least Learned Grade 6Documento3 páginasLeast Learned Grade 6Danilo Landicho jrAinda não há avaliações

- CNF DLL Week 5 q2Documento5 páginasCNF DLL Week 5 q2Bethel MedalleAinda não há avaliações

- Letter of Recommendation: .e&'hTCDocumento1 páginaLetter of Recommendation: .e&'hTCget0% (1)

- Resume - Valerie Esmeralda Krisni - Dec 2019 PDFDocumento1 páginaResume - Valerie Esmeralda Krisni - Dec 2019 PDFValerie EsmeraldaAinda não há avaliações

- Ideas-Better-World Certificate of Achievement 3z5595bDocumento2 páginasIdeas-Better-World Certificate of Achievement 3z5595bYannah HidalgoAinda não há avaliações

- Structure and Arrangement of History RoomDocumento2 páginasStructure and Arrangement of History RoomBhakti Joshi KhandekarAinda não há avaliações

- 2014 Ib2Documento2 páginas2014 Ib2sajchistoryAinda não há avaliações

- The Level 2 of Training EvaluationDocumento7 páginasThe Level 2 of Training EvaluationAwab Sibtain67% (3)

- Abdul HalimDocumento4 páginasAbdul HalimAnita CeceAinda não há avaliações

- Oxford Sociology DictionaryDocumento2 páginasOxford Sociology DictionaryTanvi MishraAinda não há avaliações

- Management A Practical Introduction 9E 9Th Edition Angelo Kinicki Download PDF ChapterDocumento51 páginasManagement A Practical Introduction 9E 9Th Edition Angelo Kinicki Download PDF Chapterandre.trowbridge312100% (9)