Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

The Study of Administration by Woodrow Wilson

Enviado por

Sreekanth ReddyDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

The Study of Administration by Woodrow Wilson

Enviado por

Sreekanth ReddyDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

TeachingAme ricanHistor .

org

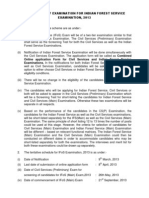

Dcument Librry 1 Audio Lectres 1 Summer lnatts 1 TAH Grnt 1 Lesson Plana I Te Aerican Fonding 1 Mastr o Aerican

Histry end Goverment

Home >Document Librar> Prgressive Era >Woodrow Wilson >The Study of Administrtion

Home >Document Librar> Eecutive Brndl >Woodrow Wilson >The Study of Administrtion

The Study of Administration

Woodrow Wilson

Noverer 1, 1886

An Essay

I suppose that no prctical science is ever studied wher ther is no need to know it. The ver

fact, therfor, that the errnently prctical science of administrtion is finding its way into college

coures in this country would prve that this country needs to kow rr about administrtion,

wer such prof of the fact rquired to mke out a case. It need not be said, however, that we do

not look into college prgrms for prof of this fact. It is a thing alrst taken for grnted arng

us, that the prsent rvemnt called civil serice rfor must, after the accomlishmnt of its firt

purose, expand into effors to imprve, not the personnel only, but also the oranization and

mthods of our govermnt offices: because it is plain that their organizations and mthods need

imrvemnt only less than their personnel. I is the object of administrtive study to discover,

firt, what governmnt can prpery and successfully do, and, secondly, how it can do these prper

things with the utrst possible efficiency and at the least possible cost either of rney or of

enery. On both these points there is obviously mch need of light arng us; and only carful study

can supply that light.

Bfor enterng on that study, however, it is needful:

I. To take som account of what other have done in the sam line; that is to say, of the histor of

the study.

II. To ascertain just what is its subject-mtter.

III. To detemne just what ar the best mthods by which to develop it, and the rst clarfying

political conceptions to car with us into it.

Unless we know and settle these things, we shall set out without char or comass.

I.

The science of adrnistration is the latest frit of that study of the science of politics which was

begun som twenty-two hundrd year ago. It is a birh of our own century, alrst of our own

generation.

Why was it so late in coming? Why did it wait till this too busy century of our to demnd attention

for itself? Adrnistrtion is the rst obvious par of govermnt; it is governmnt in action; it is the

executive, the opertive, the mst visible side of govermnt, and is of course as old as

govermnt itself. I is govermnt in action, and one nght very naturlly expect to find that

govermnt in action had arsted the attention and prvoked the scrtiny of wrters of politics

ver early in the history of systemtic thought.

But such was not the case. No one wrte systemtically of adninistrtion as a brnch of the

science of governmnt until the prsent century had passed its firt youth and had begun to put

forh its charcterstic flower of the systemtic kowledge. Up to our own day all the political

wrter whom we now rad had thought, arued, dogmtized only about the constitution of

govermnt; about the natur of the state, the essence and seat of soverignty, popular power

and kngly prrgative; about the gratest manings lying at the hear of govermnt, and the high

ends set befor the purose of govermnt by mn's nature and mn's aim. The centrl field of

contrvery was that grat field of theory in which mnarhy rde tilt against demcrcy, in which

oligarhy would have built for itself strngholds of prvilege, and in which tyranny sought opporunity

to mke good its claim to rceive subnssion frm all cometitor. Amidst this high warfar of

prnciples, adnnistrtion could commnd no pause for its own considertion. The question was

always: Who shall mke law, and what shall that law be? The other question, how law should be

adnnisterd with enlightenmnt, with equity, with speed, and without frction, was put aside as

"prctical detail" which clers could arnge afer doctor had agred upon prnciples.

That political philosophy took this dirction was of coure no accident, no chance prefernce or

perere whim of political philosopher. The philosophy of any tim is, as Hegel says, "nothing but

the spirit of that tim exprssed in abstract thought"; and political philosophy, lik philosophy of

ever other knd, has only held up the nirror to contemorar affairs. The trouble in eary tims was

almst altogether about the constitution of govermnt; and consequently that was what

engrssed mn's thoughts. Ther was little or no trouble about administrtion,-at least little that

was heeded by adninistrator. The functions of govermnt wer simple, because life itself was

simle. Gvermnt went about impertively and comelled mn, without thought of consulting their

wishes. Ther was no complex system of public rvenues and public debts to puzzle financiers;

ther wer, consequently, no financier to be puzzled. No one who possessed power was long at a

loss how to use it. The grat and only question was: Who shall possess it? Populations wer of

mnageable number; propery was of simple sors. Ther wer plenty of farm, but no stock and

bonds: mr cattle than vested intersts.

I have said that all this was tre of "eary tims"; but it was substantially tre also of comaratively

late tims. One does not have to look back of the last centur for the beginnings of the prsent

comlexities of trde and perlexities of comrial speculation, nor for the porentous birh of

national debts. God Queen Bss, doubtless, thought that the mnopolies of the sixteenth centur

wer har enough to handle without buming her hands; but they are not rmmerd in the

prsence of the giant mnopolies of the nineteenth centur. When Blacktone lamnted that

corporations had no bodies to be kicked and no souls to be damed, he was anticipating the prper

tim for such rgrts by a full centur. The pernnial discords between mster and worn which

now so often disturb industral society began before the Back Dath and the Statute of Laborr;

but never befor our own day did they assum such omnous prportions as they wear now. In bref,

if difficulties of govermntal action ar to be seen gathering in other centuries, they ar to be seen

culmnating in our own.

This is the rason why admnistrative task have nowadays to be so studiously and systemtically

adjusted to carfully tested standars of policy, the rason why we ar having now what we never

had befor, a science of admnistration. The weightier debates of constitutional prnciple ar even

yet by no mans concluded; but they ar no longer of mr irdiate prctical mmnt than

questions of administrtion. It is getting to be harder to run a constitution than to fram one.

Her is Mr. Bgehot's graphic, whimical way of depicting the differnce between the old and the

new in admnistration:

In eary tims, when a despot wishes to govem a distant prvince, he sends down a

satrp on a grnd hore, and other people on little hores; and very little is hear of the

satrp again unless he send back som of the little people to tell what he has been

doing. No grat labour of superntendence is possible. Comn rmur and casual rport

are the soures of intelligence. If it seem cerain that the province is in a bad state,

satrp No. I is rcalled, and satrp No. 2 sent out in his stead. In civilized countres the

process is difernt. You erect a bureau in the prvince you want to govem; you mke

it wrte letter and copy letter; it sends hom eight rpors per diem to the head

burau in St. Petersbur. Nobody does a sum in the prvince without som one doing

the sam sum in the capital, to "check" him, and see that he does it corctly. The

consequence of this is, to thrw on the heads of deparmnts an amunt of rading and

labour which can only be accomlished by the gratest natural aptitude, the mst

efficient training, the mst fir and rgular industry.

(Essay on Sir William Pitt. [All footnotes WW's.])

Ther is scarely a single duty of govermnt which was once simle which is not now comlex;

govermnt once had but a few mster; it now has scors of mster. Majorties formry only

underent governmnt; they now conduct govermnt. Wher govermnt once mght follow the

whim of a cour, it mst now follow the views of a nation.

And those views ar steadily widening to new conceptions of state duty; so that, at the sam tim

that the functions of govermnt ar everday becomng mr complex and dificult, they ar also

vastly multiplying in number. Administrtion is everwher putting its hands to new underakngs.

The utility, cheapness, and success of the govermnt's postal serice, for instance, point towars

the eary establishmnt of govermntal contrl of the telegrph system. Or, even if our govermnt

is not to follow the lead of the govermnts of Europe in buying or building both telegrph and

rilrad lines, no one can doubt that in som way it mst mke itself mster of msterful

cororations. The cration of national commssioner of railroads, in addition to the older state

comssions, involves a ver imorant and delicate exension of administrative functions. Whatever

hold of authorty state or federal govermnts ar to tak upon corportions, ther must follow

cars and rsponsibilities which will rquir not a little wisdom kowledge, and experience. Such

things must be studied in orer to be well done. And these, as I have said, ar only a few of the

door which ar being opened to ofices of govermnt. The idea of the state and the consequent

ideal of its duty ar underoing noteworthy change; and ''the idea of the state is the conscience of

adrnistrtion." Seeing ever day new things which the state ought to do, the next thing is to see

clearly how it ought to do them.

This is why there should be a science of adrnistration which shall seek to strighten the paths of

govermnt, to mke its business less unbusinesslike, to strengthen and purify its organization, and

to crwn its duties with dutifulness. This is one rason why ther is such a science.

But wher has this science grwn up? Surely not on this side the sea. Not much imarial scientific

mthod is to be discered in our adrnistrative practices. The poisonous atmspher of city

govermnt, the croked secrts of state adrnistrtion, the confusion, sinecursm, and corption

ever and again discoverd in the buraux at Washington forbid us to believe that any clear

conceptions of what constitutes good administrtion ar as yet ver widely curnt in the United

States. No; Amrcan writer have hitherto taken no very imporant par in the advancemnt of this

science. I has found its doctor in Eurpe. I is not of our mking; it is a foreign science, speaking

ver little of the language of English or Amrcan principle. It emloys only forign tongues; it utter

none but what ar to our rnds alien ideas. Its aim, its examles, its conditions, ar almst

exclusively grunded in the histories of foreign rces, in the prcedents of forign system, in the

lessons of forign rvolutions. It has been developed by Frnch and Grn prfessor, and is

consequently in all pars adapted to the needs of a comact state, and mde to fit highly

centralized for of govermnt; wheras, to answer our puroses, it mst be adapted, not to a

simle and comact, but to a complex and mltiform state, and mde to fit highly decentrlized

for of govermnt. If we would emloy it, we mst Amricanize it, and that not formlly, in

language mrly, but radically, in thought, prnciple, and aim as well. I mst lear our constitutions

by hear; mst get the buraucratic fever out of its veins; must inhale mch fre Amrcan air.

If an explanation be sought why a science mnifestly so susceptible of being mde useful to all

govermnts alike should have rceived attention firt in Eurpe, wher govermnt has long been a

mnopoly, rther than in England or the United States, wher governmnt has long been a commn

frnchise, the rason will doubtless be found to be twofold: firt, that in Europe, just because

govermnt was independent of popular assent, ther was mr govering to be done; and, second,

that the desir to keep govermnt a mnopoly mde the mnopolists intersted in discoverng the

least iritating mans of govering. They wer, besides, few enough to adopt mans prmtly.

I will be instrctive to look into this mtter a little mr closely. In speakng of Eurpean

govermnts I do not, of coure, include England. She has not rfused to change with the tims.

She has simly temerd the severty of the trnsition frm a polity of arstocrtic privilege to a

system of demcrtic power by slow masurs of constitutional rfor which, without prventing

rvolution, has confined it to paths of peace. But the countres of the continent for a long tim

desperately strggled against all change, and would have divered revolution by softening the

asperities of absolute govermnt. They sought so to perect their mchinery as to destry all

wearng frction, so to sweeten their mthods with consideration for the intersts of the govered

as to placate all hindering hatrd, and so assiduously and opporunely to offer their aid to all classes

of undertakings as to rnder themelves indispensable to the industrious. They did at last give the

people constitutions and the franchise; but even after that they obtained leave to continue

despotic by becoing pateral. They mde themelves too efficient to be dispensed with, too

smothly operative to be noticed, too enlightened to be inconsiderately questioned, too benevolent

to be suspected, too powerul to be coped with. All this has rquird study; and they have closely

studied it.

On this side the sea we, the while, had kown no grat difficulties of govermnt. With a new

country in which ther was rom and rmnertive emloymnt for everybody, with liberl principles

of governmnt and unlimited skll in prctical politics, we wer long exemted frm the need of being

anxiously carful about plans and mthods of administrtion. We have naturally been slow to see

the use or significance of those mny volums of leared rsearh and painstaking exaination into

the ways and mans of conducting govermnt which the prsses of Eurpe have been sending to

our librares. Like a lusty child, govermnt with us has exanded in natur and grwn grat in

statur, but has also becom awkar in mvemnt. The vigor and incrase of its life has been

altogether out of prportion to its skill in living. It has gained strngth, but it has not acquird

depormnt. Grat, therfor, as has been our advantage over the countres of Eurpe in point of

ease and health of constitutional developmnt, now that the tim for mr carful adinistrative

adjustmnts and larer adinistrative kowledge has com to us, we ar at a signal disadvantage

as compard with the transatlantic nations; and this for rasons which I shall try to mke clear.

Judging by the constitutional histores of the chief nations of the mdem word, there my be said

to be thre perods of growth through which governmnt has passed in all the mst highly developed

of exsting system, and thrugh which it prises to pass in all the rst. The firt of these perods

is that of absolute rler, and of an adinistrtive system adapted to absolute rle; the second is

that in which constitutions ar framd to do away with absolute rler and substitute popular

contrl, and in which administrtion is neglected for these higher concers; and the thir is that in

which the sovereign people undertake to develop adinistration under this new constitution which

has brught them into power.

Those govermnts ar now in the lead in adinistrtive practice which had rler still absolute but

also enlightened when those mdem days of political illuination cam in which it was mde evident

to all but the blind that goverors ar prpery only the serants of the govered. In such

govermnts administration has been oranized to subsere the generl weal with the simlicity and

efectiveness vouchsafed only to the underakngs of a single will.

Such was the case in Prssia, for instance, wher adinistration has been mst studied and mst

nearly perected. Frderic the Grat, stern and msterul as was his rle, still sincerly prfessed to

rgar himelf as only the chief serant of the state, to consider his grat office a public trst; and

it was he who, building upon the foundations laid by his father, began to oranize the public serice

of Prssia as in ver earest a serice of the public. His no less absolute successor, Frderic William

III, under the inspirtion of Stein, again, in his tum, advanced the wor still further, planning mny

of the brader strctural featurs which give finess and for to Prssian adrnistration to-day.

Alrst the whole of the adrrble system has been developed by kingly initiative.

Of sirlar orgin was the prctice, if not the plan, of rdem Frnch adrnistration, with its

symtrical divisions of tertor and its ordery gradations of office. The days of the Revolution of

the Constituent Assemly wer days of constitution-writing, but they can harly be called days of

constitution-makng. The rvolution heralded a period of constitutional developmnt, -the entrance

of Frnce upon the second of those perods which I have enumrated,-but it did not itself

inaugurate such a perod. I interrupted and unsettled absolutism, but it did not destroy it. Napoleon

succeeded the rnarhs of Frnce, to exerise a power as unrstricted as they had ever

possessed.

The rcasting of Frnch adrnistration by Napoleon is, therefor, m second examle of the

perecting of civil mchiner by the single will of an absolute rler befor the dawn of a

constitutional era. No corporte, popular will could ever have effected arngemnts such as those

which Napoleon comnded. Arangemnts so simple at the expense of local prjudice, so logical in

their indiffernce to popular choice, rght be decreed by a Constituent Assembly, but could be

established only by the unlirted authority of a despot. The system of the year VIII was rthlessly

thorugh and hearlessly perect. I was, besides, in lare par, a rtur to the despotism that had

been overhrwn.

Arng those nations, on the other hand, which enterd upon a season of constitution-mkng and

popular rfor befor administration had received the imrss of liberl principle, administrtive

imrvemnt has been tary and half-done. Once a nation has emared in the business of

mnufacturng constitutions, it finds it exceedingly difficult to close out that business and open for

the public a burau of skilled, econorcal adrnistration. Ther seem to be no end to the tinkerng

of constitutions. Your ordinary constitution will last you hardly ten year without rpair or

additions; and the tim for adrnistrtive detail coms late.

Her, of coure, our exmples ar England and our own country. In the days of the Angevin kings,

befor constitutional life had taken rot in the Grat Charer, legal and administrtive rfom began

to prceed with sense and vigor under the imulse of Henry II's shrwd, busy, pushing, indomitable

spirt and purose; and kingly initiative seemd destined in England, as elsewher, to shape

govermntal growth at its will. Bt imulsive, erant Richard and weak despicable John wer not

the mn to cary out such schems as their father's. Adrnistrtive developmnt gave place in their

rigns to constitutional strggles; and Parliamnt becam king before any English rnarh had had

the practical genius or the enlightened conscience to devise just and lasting fom for the civil

serice of the state.

The English rce, consequently, has long and successfully studied the ar of curing executive

power to the constant neglect of the art of perfecting executive mthods. It has exerised itself

mch rr in contrlling than in enerizing govermnt. It has been rr concered to rnder

govermnt just and rderte than to mke it facile, well-orerd, and effective. English and

Amrcan political histor has been a histor, not of adrnistrtive developmnt, but of legislative

overight,-not of prgrss in govermntal oranization, but of advance in law-mkng and political

crticism. Consequently, we have rached a tim when administrtive study and cration ar

imeratively necessar to the well-being of our govermnts saddled with the habits of a long perod

of constitution-mking. That perod has practically closed, so far as the establishmnt of essential

prnciples is concered, but we cannot shake off its atmspher. We go on crticizing when we

ought to be crating. We have rached the thir of the periods I have mntioned,-the perod,

namly, when the people have to develop admnistrtion in accorance with the constitutions they

won for themelves in a prvious perod of strggle with absolute power; but we ar not prpard

for the tasks of the new perod.

Such an explanation seem to affor the only escape frm blank astonishmnt at the fact that, in

spite of our vast advantages in point of political libery, and above all in point of practical political

skill and sagacity, so mny nations ar ahead of us in administrtive oranization and admnistrtive

skill. Why, for instance, have we but just begun purfying a civil serice which was rtten full fifty

year ago? To say that slavery divered us is but to rpeat what I have said-that flaws in our

constitution delayed us.

Of course all rasonable prfernce would declar for this English and Amrcan course of politics

rther than for that of any Eurpean countr. We should not like to have had Prssia's histor for

the sake of having Prssia's admnistrtive skill; and Prssia's paricular system of administration

would quite suffocate us. I is better to be untrined and free than to be serile and systemtic.

Still there is no denying that it would be better yet to be both fre in spirt and prficient in

prctice. It is this even mr rasonable prfernce which impels us to discover what ther my be

to hinder or delay us in naturlizing this mch-to-be-desird science of administrtion.

What, then, is ther to prvent?

Well, principally, popular soverignty. It is harer for demcrcy to oranize admnistration than for

mnarhy. The ver completeness of our mst chershed political successes in the past emarsses

us. We have enthrned public opinion; and it is forbidden us to hope durng its rign for any quick

schooling of the soverign in executive experness or in the conditions of perect functional balance

in governmnt. The very fact that we have ralized popular rle in its fullness has mde the task of

organizaing that rle just so mch the mre difficult. In orer to mke any advance at all we must

instrct and persuade a multitudinous mnarh called public opinion,-a mch less feasible

underaking than to influence a single mnarh called a kng. An individual soverign will adopt a

simle plan and car it out dirctly: he will have but one opinion, and he will emody that one

opinion in one comnd. But this other soverign, the people, will have a scor of differng opinions.

They can agre upon nothing simple: advance mst be mde thrugh comromse, by a

comounding of differnces, by a trmng of plans and a supprssion of too strightforar

prnciples. Ther will be a succession of rsolves rnning thrugh a coure of year, a drpping fir

of comnds rnning through the whole gamt of mdifications.

In governmnt, as in virue, the harest of things is to mke prgrss. Forry the reason for this

was that the single peron who was sovereign was generally either selfish, ignornt, tinid, or a

fool,-albeit ther was now and again one who was wise. Nowadays the rason is that the mny, the

people, who ar soverign have no single ear which one can apprach, and ar selfish, ignorant,

tind, stubbor, or foolish with the selfishness, the ignornces, the stubbomnesses, the tindities, or

the follies of severl thousand persons,-albeit there ar hundrds who ar wise. Once the

advantage of the rforr was that the soverign's nind had a definite locality, that it was

contained in one mn's head, and that consequently it could be gotten at; though it was his

disadvantage that the mind leared only reluctantly or only in smll quantities, or was under the

influence of som one who let it lear only the wrng things. Now, on the contrr, the rformr is

bewildered by the fact that the soverign's nnd has no definite locality, but is contained in a voting

mjorty of several nillion heads; and emarssed by the fact that the nind of this soverign also is

under the influence of favortes, who ar none the less favortes in a good old-fashioned sense of

the word because they ar not perons by prconceived opinions; i.e., prjudices which ar not to

be rasoned with because they are not the childrn of rason.

Wherver rgar for public opinion is a first prnciple of govermnt, prctical rfor must be slow

and all refor mst be full of comprnses. For wherver public opinion exsts it mst rle. This is

now an axiom half the word over, and will prsently com to be believed even in Russia. Whoever

would effect a change in a rdern constitutional govermnt mst firt educate his fellow-citizens

to want some change. That done, he mst peruade them to want the paricular change he wants.

He mst firt mke public opinion willing to listen and then see to it that it listen to the rght things.

He mst stir it up to search for an opinion, and then mnage to put the rght opinion in its way.

The firt step is not less difficult than the second. With opinions, possession is rr than nine

points of the law. I is next to impossible to dislodge them. Institutions which one genertion

rgars as only a mkeshift apprximtion to the realization of a principle, the nex genertion

honor as the nearst possible apprximtion to that prnciple, and the next worhips the prnciple

itself. It takes scarely thre genertions for the apotheosis. The grandson accepts his

grndfather's hesitating expermnt as an integrl par of the fixed constitution of natur.

Even if we had clear insight into all the political past, and could for out of perectly instrcted

heads a few steady, infallible, placidly wise mxim of governmnt into which all sound political

doctrne would be ultimtely rsolvable, would the countr act on them? That is the question. The

bulk of mnknd is rgidly unphilosophical, and nowadays the bulk of mnknd votes. A trth mst

becom not only plain but also comrnplace before it will be seen by the people who go to their

wor ver early in the rming; and not to act upon it mst involve grat and pinching

inconveniences befor these sam people will mke up their ninds to act upon it.

And wher is this unphilosophical bulk of mnkind rr mltifarious in its composition than in the

United States? To know the public nind of this country, one mst know the mind, not of Amrcans

of the older stock only, but also of Irshmn, of Gerns, of negres. In order to get a footing for

new doctrne, one mst influence ninds cast in ever ruld of rce, ninds inherting ever bias of

envirnmnt, warped by the histores of a scor of differnt nations, ward or chilled, closed or

expanded by almst every climte of the globe.

So rch, then, for the histor of the study of administrtion, and the peculiary difficult conditions

under which, enterng upon it when we do, we rst underake it. What, now, is the subject-mtter

of this study, and what ar its charcterstic objects?

D.

The field of administrtion is a field of business. It is rmved frm the huny and strife of politics; it

at mst points stands apar even frm the debatable grund of constitutional study. I is a par of

political life only as the mthods of the counting house ar a par of the life of society; only as

mchiner is part of the mnufacturd prduct. Bt it is, at the sam tim, raised ver far above

the dull level of mr technical detail by the fact that thrugh its greater principles it is dirctly

connected with the lasting mxm of political wisdom the pernent trths of political prgress.

The object of administrative study is to rscue executive mthods frm the confusion and costliness

of emirical exermnt and set them upon foundations laid deep in stable principle.

It is for this rason that we rst rgar civil-serice rfor in its present stages as but a prlude

to a fuller adrnistrtive rfor. We ar now rctifying mthods of appointmnt; we must go on to

adjust executive functions mr fitly and to prscribe better mthods of executive organization and

action. Civil-serice rform is thus but a mrl prpartion for what is to follow. It is clearng the

mrl atmsphere of official life by establishing the sanctity of public office as a public trst, and,

by mking serice unpartisan, it is opening the way for mking it businesslike. By sweetening its

mtives it is rnderng it capable of imrving its mthods of work.

Let m expand a little what I have said of the prvince of adrnistration. Most imortant to be

obsered is the trth alrady so much and so forunately insisted upon by our civil-serice

rforrs; namly, that adrnistration lies outside the prper sphere of politics. Administrtive

questions ar not political questions. Although politics sets the task for administrtion, it should not

be sufferd to mnipulate its offices.

This is distinction of high authority; ernent Grn wrters insist upon it as of course. Bluntschli,

for instance, bids us separte administrtion alik frm politics and frm law. Politics, he says, is

state activity "in things grat and univeral", while "adrnistrtion, on the other hand," is "the

activity of the state in individual and smll things. Politics is thus the special prvince of the

statesmn, administrtion of the technical official. " "Policy does nothing without the aid of

adrnistrtion"; but administrtion is not therfor politics. But we do not rquir Germn authorty

for this position; this discrrnation between adrnistrtion and politics is now, happily, too obvious

to need furher discussion.

Ther is another distinction which rst be wored into all our conclusions, which, though but

another side of that between administrtion and politics, is not quite so easy to keep sight of: I

man the distinction between constitutional and adrnistrative questions, between those

govermntal adjustmnts which ar essential to constitutional prnciple and those which ar mrly

instrmntal to the possibly changing purposes of a wisely adapting convenience.

One cannot easily mk clear to ever one just wher administrtion rsides in the varous

departmnts of any practicable govermnt without entering upon pariculars so numrus as to

confuse and distinctions so mnute as to distrct. No lines of demrcation, setting apar

admnistrtive from non-admnistrative functions, can be rn between this and that deparmnt of

govermnt without being rn up hill and down dale, over dizzy heights of distinction and thrugh

dense jungles of statutor enactmnt, hither and thither around "ifs" and "buts," "whens" and

"however," until they becom altogether lost to the comn eye not accustomd to this sor of

sureying, and consequently not acquainted with the use of the theodolite of logical discermnt. A

grat deal of administration goes about incognito to mst of the word, being confounded now with

political "mnagemnt," and again with constitutional prnciple.

Peraps this ease of confusion my explain such utternces as that of Niebuhrs: "Ubery," he says,

"depends incomarbly mr upon admnistrtion than upon constitution." At firt sight this appear

to be largely tre. Apparently facility in the actual exerise of liberty does depend mr upon

admnistrtive arrngemnts than upon constitutional guarantees; although constitutional

guarntees alone secur the exstence of libery. But-upon second thought-is even so mch as this

tre? Libery no mr consists in easy functional mvemnt than intelligence consists in the ease

and vigor with which the lims of a strng mn mve. The prnciples that rle within the mn, or the

constitution, ar the vital sprngs of libery or seritude. Bcause independence and subjection ar

without chains, ar lightened by ever easy-worng device of considerte, pateral govermnt,

they are not therby transford into libery. Libery cannot live apar frm constitutional principle;

and no admnistration, however perfect and liberal its mthods, can give mn mr than a poor

counterfeit of libery if it rst upon illiberal prnciples of govermnt.

A clear view of the difference between the prvince of constitutional law and the prvince of

admnistrtive function ought to leave no room for misconception; and it is possible to nam som

rughly definite crtera upon which such a view can be built. Public admnistration is detailed and

systemtic execution of public law. Ever paricular application of generl law is an act of

admnistrtion. The assessmnt and rising of taxes, for instance, the hanging of a crmnal, the

trnsportation and delivery of the mils, the equipmnt and rcriting of the ar and navy, etc.,

ar all obviously acts of admnistration; but the generl laws which dirct these things to be done

ar as obviously outside of and above administrtion. The brad plans of govermntal action ar

not administrtive; the detailed execution of such plans is admnistrative. Constitutions, therfor,

prperly concer themelves only with those instrmntalities of govermnt which ar to contrl

general law. Our federl constitution obseres this prnciple in saying nothing of even the gratest

of the purly executive offices, and speaking only of that Prsident of the Union who was to shar

the legislative and policy-mkng functions of govermnt, only of those judges of highest

jursdiction who wer to interrt and guard its principles, and not of those who wer mrly to give

utternce to them.

This is not quite the distinction between Will and answerng Ded, because the admnistrtor should

have and does have a will of his own in the choice of mans for accolliishing his work. He is not

and ought not to be a mr passive instrmnt. The distinction is between generl plans and special

mans.

Ther is, indeed, one point at which adrnistrtive studies trnch on constitutional grund-or at

least upon what seem constitutional grund. The study of adrnistrtion, philosophically viewed, is

closely connected with the study of the prper distribution of constitutional authorty. To be

efficient it mst discover the siliest arangemnts by which rsponsibility can be unrstakbly

fixed upon officials; the best way of dividing authorty without halerng it, and rsponsibility

without obscurng it. And this question of the distribution of authority, when taken into the spher

of the higher, the orginating functions of govermnt, it is obviously a central constitutional

question. If administrtive study can discover the best prnciples upon which to base such

distrbution, it will have done constitutional study an invaluable serice. Montesquieu did not, I am

convinced, say the last wor on this head.

To discover the best prnciple for the distribution of authority is of grater importance, possibly,

under a demcratic system where officials sere mny mster, than under other wher they

sere but a few. All soverigns are suspicious of their serants, and the soverign people is no

exception to the rle; but how is its suspicion to be allayed by kowledge? If that suspicion could

but be clarified into wise vigilance, it would be altogether salutary; if that vigilance could be aided

by the unrstakble placing of rsponsibility, it would be altogether beneficent. Suspicion in itself is

never healthful either in the prvate or in the public rnd. Trust is strength in all rlations of life;

and, as it is the office of the constitutional rforr to crate conditions of trstfulness, so it is the

office of the administrtive oranizer to fit adrnistrtion with conditions of clear-cut rsponsibility

which shall insure trstworhiness.

And let m say that lare power and unhallerd discrtion seem to m the indispensable

conditions of rsponsibility. Public attention mst be easily dircted, in each case of good or bad

adrnistrtion, to just the mn desering of prise or blam. Ther is no danger in power, if only it

be not irrsponsible. If it be divided, dealt out in shars to mny, it is obscured; and if it be

obscurd, it is mde irsponsible. But if it be centerd in heads of the serice and in heads of

brnches of the serice, it is easily watched and brught to book. If to kep his office a mn mst

achieve open and honest success, and if at the sam tim he feels himelf entrsted with large

fredom of discretion, the grater his power the less likly is he to abuse it, the mr is he nered

and soberd and elevated by it. The less his power, the mr safely obscur and unnoticed does he

feel his position to be, and the mr radily does he rlapse into rmissness.

Just here we mnifestly emre upon the field of that still larer question,-the prper rlations

between public opinion and adrnistrtion.

To whom is official trstworthiness to be disclosed, and by whom is it to be rwared? Is the official

to look to the public for his med of prise and his push of prmtion, or only to his superor in

office? Ar the people to be called in to settle administrtive discipline as they ar called in to settle

constitutional principles? These questions evidently find their rot in what is undoubtedly the

fundamntal prblem of this whole study. That prblem is: What par shall public opinion take in the

conduct of administrtion?

The rght answer seem to be, that public opinion shall play the par of authortative crtic.

But the method by which its authorty shall be mde to tell? Our peculiar Amrcan difficulty in

oranizing adnnistrtion is not the danger of losing libery, but the danger of not being able or

willing to separate its essentials from its accidents. Our success is mde doubtful by that besetting

err of our, the err of tring to do too mch by vote. Self-governmnt does not consist in

having a hand in everything, any mr than housekeeping consists necessarily in cooking dinner with

one's own hands. The cook mst be trsted with a lare discrtion as to the mnagemnt of the

firs and the ovens.

In those countries in which public opinion has yet to be instrcted in its prvileges, yet to be

accustomd to having its own way, this question as to the prvince of public opinion is mch mr

rady soluble than in this country, wher public opinion is wide awake and quite intent upon having

its own way anyhow. It is pathetic to see a whole book written by a Grn prfessor of political

science for the purpose of saying to his countrymn, "Please try to have an opinion about national

afair"; but a public which is so mdest my at least be expected to be ver docile and

acquiescent in learing what things it has not a rght to think and speak about imeratively. It my

be sluggish, but it will not be mddlesom. It will subnt to be instrcted befor it tries to instrct.

Its political education will com befor its political activity. In tring to instrct our own public

opinion, we ar dealing with a pupil apt to think itself quite suficiently instrcted beforhand.

The prblem is to mke public opinion efficient without sufferng it to be mddlesom. Dirctly

exerised, in the overight of the daily details and in the choice of the daily mans of govermnt,

public criticism is of course a clumy nuisance, a rstic handling delicate mchinery. But as

superntending the grater fores of fortive policy alike in politics and administrtion, public

crticism is altogether safe and beneficent, altogether indispensable. Let administrtive study find

the best mans for giving public crticism this control and for shutting it out frm all other

intererence.

But is the whole duty of adninistrative study done when it has taught the people what sor of

adninistrtion to desir and demnd, and how to get what they demnd? Ought it not to go on to

drll candidates for the public serice?

Ther is an admirble mvemnt towards univeral political education now afoot in this countr. The

tim will soon com when no college of rspectability can affor to do without a well-filled chair of

political science. But the education thus impared will go but a cerain length. It will multiply the

numer of intelligent crtics of govermnt, but it will crate no component body of adnnistrator.

It will prepar the way for the developmnt of a sur-footed understanding of the generl principles

of governmnt, but it will not necessarly foster skill in conducting govermnt. It is an education

which will equip legislators, peraps, but not executive officials. If we ar to imrve public opinion,

which is the mtive power of govermnt, we mst prpar better officials as the apparatus of

govermnt. If we ar to put in new boilers and to mnd the firs which drive our govermntal

mchinery, we must not leave the old wheels and joints and valves and bands to crak and buzz

and clatter on as best they my at bidding of the new fore. We mst put in new rnning pars

wherver ther is the least lack of strngth or adjustmnt. It will be necessary to organize

demcracy by sending up to the cometitive examinations for the civil serice mn definitely

prpard for standing liberl tests as to technical knowledge. A technically schooled civil serice will

prsently have becom indispensable.

I know that a corps of civil serants prpard by a special schooling and drilled, after appointmnt,

into a perfected oranization, with apprprate hierarhy and characterstic discipline, seem to a

grat mny ver thoughtful perons to contain elemnts which night comine to mke an offensive

official class,- a distinct, seni-corporte body with symathies divored frm those of a

prgrssive, fre-spirted people, and with hears narwed to the manness of a bigoted officialism.

Cerainly such a class would be altogether hateful and harul in the United States. Any masur

calculated to produce it would for us be masurs of raction and of folly.

But to fear the cration of a domineerng, illiberl officialism as a rsult of the studies I am her

prposing is to miss altogether the prnciple upon which I wish mst to insist. That principle is, that

adninistrtion in the United States mst be at all points sensitive to public opinion. A body of

thorughly trined officials sering durng good behavior we mst have in any case: that is a plain

business necessity. But the apprhension that such a body will be anything un-Amrican clear

away the mmnt it is asked. What is to constitute good behavior? For that question obviously

cares its own answer on its face. Steady, heary allegiance to the policy of the govermnt they

sere will constitute good behavior. That policy will have no taint of officialism about it. It will not

be the cration of pernent officials, but of statesmn whose rsponsibility to public opinion will be

dirct and inevitable. Breaucrcy can exist only wher the whole serice of the state is rmved

frm the comn political life of the people, its chiefs as well as its rnk and file. Its mtives, its

objects, its policy, its standars, must be buraucratic. It would be difficult to point out any

examles of imudent exclusiveness and aritrrness on the part of officials doing serice under a

chief of deparmnt who rally sered the people, as all our chiefs of departmnts mst be mde to

do. It would be easy, on the other hand, to adduce other instances like that of the influence of

Stein in Prssia, wher the leadership of one statesmn imued with tre public spirt trnsformd

argant and perunctory buraux into public-spirited instrmnts of just govermnt.

The ideal for us is a civil serice culturd and self-sufficient enough to act with sense and vigor,

and yet so intimtely connected with the popular thought, by mans of elections and constant

public counsel, as to find aritrariness of class spirit quite out of the question.

m.

Having thus viewed in som sort the subject-mtter and the objects of this study of adnnistrtion,

what are we to conclude as to the mthods best suited to it-the points of view mst advantageous

for it?

Gvermnt is so near us, so mch a thing of our daily familiar handling, that we can with difficulty

see the need of any philosophical study of it, or the exact points of such study, should be

underaken. We have been on our feet too long to study now the art of walking. We ar a practical

people, mde so apt, so adept in self-govermnt by centuries of experimntal drll that we ar

scarely any longer capable of pereiving the awkwarness of the paricular system we my be

using, just because it is so easy for us to use any system. We do not study the ar of govering:

we gover. Bt mr unschooled genius for affair will not save us frm sad blunder in

adrnistrtion. Though dercrts by long inhertance and repeated choice, we ar still rther crde

dercrats. Old as dercrcy is, its oranization on a basis of rdem ideas and conditions is still an

unaccomplished wor. The dercrtic state has yet to be equipped for caring those enorus

burens of adrnistrtion which the needs of this industral and trading age ar so fast

accumlating. Without comartive studies in govermnt we cannot rid ourselves of the

rsconception that adrnistrtion stands upon an essentially differnt basis in a dercrtic state

frm that on which it stands in a non-dercrtic state.

After such study we could grnt dercracy the sufficient honor of ultimtely detenining by debate

all essential questions affecting the public weal, of basing all strcturs of policy upon the mjor

will; but we would have found but one rle of good adrnistrtion for all govermnts alike. So far

as administrtive functions ar concered, all govermnts have a strng structurl likeness; rr

than that, if they ar to be uniformly useful and efficient, they must have a strng strctural

likeness. A fre mn has the sam bodily orans, the sam executive pars, as the slave, however

difernt my be his rtives, his serices, his energies. Monarhies and dercrcies, rdically

differnt as they ar in other rspects, have in rality mch the sam business to look to.

I is abundantly safe nowadays to insist upon this actual likeness of all govermnts, because these

ar days when abuses of power ar easily exposed and arsted, in countres like our own, by a

bold, aler, inquisitive, detective public thought and a stury popular self-dependence such as never

existed befor. We ar slow to apprciate this; but it is easy to apprciate it. Try to imgine

peronal govermnt in the United States. I is like trying to imgine a national worhip of Zeus. Our

imginations ar too rdem for the feat.

But, besides being safe, it is necessary to see that for all govermnts alike the legitimte ends of

adrnistrtion are the sam, in order not to be frghtened at the idea of looking into forign system

of adrnistrtion for instruction and suggestion; in orer to get rd of the apprhension that we

rght perhance blindly borw somthing incomatible with our prnciples. That mn is blindly astry

who denounces attemts to trnsplant foreign system into this country. It is imossible: they

simly would not grw her. But why should we not use such pars of forign contrvances as we

want, if they be in any way sericeable? We ar in no danger of using them in a forign way. We

borwed rice, but we do not eat it with chopstick. We borwed our whole political language frm

England, but we leave the wors "king" and "lors" out of it. What did we ever orginate, except the

action of the federl govermnt upon individuals and som of the functions of the federl suprm

cour?

We can borw the science of administration with safety and prfit if only we rad all fundamntal

differnces of condition into its essential tenets. We have only to filter it through our constitutions,

only to put it over a slow fir of crticism and distil away its forign gases.

I know that there is a sneaking fear in som conscientiously patrotic rnds that studies of Eurpean

system rght signalize som forign mthods as better than som Amrcan mthods; and the fear

is easily to be undertood. But it would scarely be avowed in just any company.

I is the mr necessar to insist upon thus putting away all prjudices against lookng anywher in

the world but at hor for suggestions in this study, because nowher else in the whole field of

politics, it would seem, can we mke use of the historcal, comarative mthod mr safely than in

this prvince of adrnistration. Perhaps the mr novel the fon we study the better. We shall the

sooner lear the peculiarities of our own mthods. We can never lear either our own weakesses or

our own virues by comarng ourselves with ourelves. We ar too used to the appearnce and

prcedur of our own system to see its tre significance. Peraps even the English system is too

mch like our own to be used to the mst prfit in illustrtion. I is best on the whole to get entirly

away from our own atmspher and to be mst careful in exarning such system as those of

Frnce and Gnny. Seeing our own institutions thrugh such media, we see ourelves as

forigner rght see us wer they to look at us without prconceptions. Of ourelves, so long as we

know only ourelves, we know nothing.

Let it be noted that it is the distinction, alrady drawn, between administration and politics which

mkes the comartive mthod so safe in the field of adrnistrtion. When we study the

adrnistrtive system of Frnce and Gnny, kowing that we are not in searh of political

prnciples, we need not car a pepperor for the constitutional or political reasons which

Frnchmn or Genns give for their prctices when explaining them to us. If I see a mrerus

fellow sharening a knife clevery, I can borw his way of sharening the kife without borwing

his prbable intention to comrt murer with it; and so, if I see a mnarhist dyed in the wool

mnaging a public burau well, I can lear his business mthods without changing one of m

rpublican spots. He my sere his king; I will continue to sere the people; but I should like to

sere m soverign as well as he seres his. By keeping this distinction in view,-that is, by studying

adrnistrtion as a mans of putting our own politics into convenient prctice, as a mans of mking

what is demcratically politic towars all adrnistratively possible towars each,-we ar on perectly

safe grund, and can learn without err what forign system have to teach us. We thus devise an

adjusting weight for our comarative mthod of study. We can thus scrtinize the anatom of

forign govermnts without fear of getting any of their diseases into our veins; dissect alien

system without apprhension of blood-poisoning.

Our own politics must be the touchstone for all theores. The prnciples on which to base a science

of adrnistrtion for Amrca mst be prnciples which have demcratic policy ver mch at hear.

And, to suit Amrcan habit, all generl theores mst, as theores, keep mdestly in the backgrund,

not in open arumnt only, but even in our own minds,-lest opinions satisfactor only to the

standards of the librry should be dogmtically used, as if they mst be quite as satisfactory to the

standards of practical politics as well. Dctrinair devices must be postponed to tested prctices.

Arngemnts not only sanctioned by conclusive experence elsewher but also congenial to

Amrcan habit must be prferd without hesitation to theortical perection. In a wor, steady,

prctical statesmnship must com firt, closet doctrine second. The cosmpolitan what-to-do mst

always be comnded by the Amrcan how-to-do-it.

Our duty is, to supply the best possible life to a federal oranization, to system within system; to

mke town, city, county, state, and federal governmnts live with a like strngth and an equally

assurd healthfulness, keeping each unquestionably its own mster and yet mking all

interependent and co-opertive comining independence with mtual helpfulness. The task is grat

and imorant enough to attrct the best minds.

This interlacing of local self-governmnt with federal self-govermnt is quite a mdem conception.

I is not like the arngemnts of imeral federtion in Grny. Ther local govermnt is not yet,

fully, local sel-govermnt. The buraucrat is everywher busy. His efficiency sprngs out of esprit

de corps, out of car to mke ingrtiating obeisance to the authorty of a superor, or at best, out

of the soil of a sensitive conscience. He seres, not the public, but an irsponsible minister. The

question for us is, how shall our series of govermnts within governmnts be so administerd that

it shall always be to the interst of the public officer to sere, not his superior alone but the

comnity also, with the best efforts of his talents and the soberst serice of his conscience?

How shall such serice be mde to his commnest interst by contributing abundantly to his

sustenance, to his dearst interst by furherng his amition, and to his highest interst by

advancing his honor and establishing his charcter? And how shall this be done alike for the local

part and for the national whole?

If we solve this prblem we shall again pilot the world. There is a tendency-is ther not?- a

tendency as yet dim, but alrady steadily imulsive and cleary destined to prvail, towars, firt

the confedertion of pars of emirs like the Btish, and finally of grat states themelves. Instead

of centralization of power, ther is to be wide union with tolerted divisions of prrgative. This is a

tendency towards the Amrcan type of govermnts joined with govermnts for the puruit of

comn purposes, in honorry equality and honorable subordination. Like principles of civil liberty ar

everwher fosterng like mthods of govermnt; and if comartive studies of the ways and

mans of govermnt should enable us to offer suggestions which will prcticably combine openness

and vigor in the adrnistration of such govermnts with rady docility to all serious, well-sustained

public criticism, they will have apprved themelves worhy to be ranked amng the highest and

mst fritful of the grat deparmnts of political study. That they will issue in such suggestions I

confidently hope.

WOODROW WILSON

UR: http: //www .TeachingAmrcanHistory .er/library /index.asp?doc umntprint =65

Você também pode gostar

- National Development Plan A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionNo EverandNational Development Plan A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionAinda não há avaliações

- PA 201 Introduction - HandoutsDocumento20 páginasPA 201 Introduction - Handoutsrania100% (1)

- Public AdministrationDocumento2 páginasPublic AdministrationElah EspinosaAinda não há avaliações

- What Is Economic DevelopmentDocumento2 páginasWhat Is Economic DevelopmentNna Yd UJAinda não há avaliações

- Approaches To The Study of PADocumento62 páginasApproaches To The Study of PAPrem Chopra100% (1)

- Public Administration Matters EssayDocumento2 páginasPublic Administration Matters EssayAdriana CorinaAinda não há avaliações

- Public AdministrationDocumento4 páginasPublic AdministrationSohil BakshiAinda não há avaliações

- Unit-12 Development StrategiesDocumento13 páginasUnit-12 Development StrategieshercuAinda não há avaliações

- Philippine Administrative System Lecture 5. DR J. RosiniDocumento24 páginasPhilippine Administrative System Lecture 5. DR J. RosiniRichard Daliyong100% (1)

- Government Studies (Pig3571) Introduction To Public AdministrationDocumento21 páginasGovernment Studies (Pig3571) Introduction To Public AdministrationashleykabajaniAinda não há avaliações

- Concept Map #1 - Analyzing Leadership Concepts - Gil OrenseDocumento1 páginaConcept Map #1 - Analyzing Leadership Concepts - Gil OrenseGil OrenseAinda não há avaliações

- Discipline and GrievanceDocumento32 páginasDiscipline and Grievanceranipriyat100% (1)

- Change AgentDocumento3 páginasChange AgentAlamin SheikhAinda não há avaliações

- Classical Theory of OrganisationDocumento4 páginasClassical Theory of Organisationlav RathoreAinda não há avaliações

- Public AdDocumento4 páginasPublic AdGail CariñoAinda não há avaliações

- School of Management Thought-Based On ShafritzDocumento84 páginasSchool of Management Thought-Based On ShafritzAR Rashid100% (1)

- Wilson VisionDocumento3 páginasWilson VisionRahul KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Decision Making Processes For Effective Policy ImplementationDocumento12 páginasDecision Making Processes For Effective Policy ImplementationjazzskyblueAinda não há avaliações

- The Proverbs of AdministrationDocumento5 páginasThe Proverbs of AdministrationAnn Quibedo Tagayuna Caga-ananAinda não há avaliações

- Issues of Development Administration - MidsemDocumento8 páginasIssues of Development Administration - MidsemVictor BrownAinda não há avaliações

- Successful Versus Effective LeaderDocumento3 páginasSuccessful Versus Effective LeaderAbhijit Jadhav100% (1)

- Evolution of Development Administration Reynalyn BarbacenaDocumento12 páginasEvolution of Development Administration Reynalyn BarbacenaShaneBattier100% (1)

- Civil Service CommissionDocumento14 páginasCivil Service CommissionShenette Duriens100% (2)

- Transparency in Phillipines Through Media and CitizensDocumento156 páginasTransparency in Phillipines Through Media and CitizensUltimate Multimedia ConsultAinda não há avaliações

- Scientific ManagementDocumento12 páginasScientific ManagementMohammad Mamunur RashidAinda não há avaliações

- Checks and BalancesDocumento9 páginasChecks and BalancesHumphrey OdchigueAinda não há avaliações

- 04 Personnel Admin Sit RationDocumento292 páginas04 Personnel Admin Sit RationTrivedishanAinda não há avaliações

- SOCIAL System and Organizational CultureDocumento7 páginasSOCIAL System and Organizational CultureRenn TalensAinda não há avaliações

- Approaches and Paradigms of Public AdministrationDocumento32 páginasApproaches and Paradigms of Public AdministrationannAinda não há avaliações

- 1235789370personnel Administration IDocumento111 páginas1235789370personnel Administration IJay-ann Mattel LabraAinda não há avaliações

- Past Paper QuestionsDocumento4 páginasPast Paper QuestionsAmy 786Ainda não há avaliações

- Polytechnic University of The PhilippinesETDSTDocumento7 páginasPolytechnic University of The PhilippinesETDSTmarie deniegaAinda não há avaliações

- Republic Act NO. 9485: "Anti-Red Tape Act of 2007"Documento33 páginasRepublic Act NO. 9485: "Anti-Red Tape Act of 2007"Gil Mae HuelarAinda não há avaliações

- PAD204 AssignmentDocumento11 páginasPAD204 AssignmentCorneynie Reynd GunsinAinda não há avaliações

- The Father of Scientific ManagementDocumento35 páginasThe Father of Scientific ManagementsatkaurchaggarAinda não há avaliações

- Art X Local GovernmentDocumento3 páginasArt X Local GovernmentJoseEdgarNolascoLucesAinda não há avaliações

- The - Napoleonic - PDF Comparative Public AdministrationDocumento15 páginasThe - Napoleonic - PDF Comparative Public AdministrationTanja Lindquist OlsenAinda não há avaliações

- PA 205 Learning Guide 7-14Documento6 páginasPA 205 Learning Guide 7-14Ali HasanieAinda não há avaliações

- Module 2 Intro. To P.A.Documento6 páginasModule 2 Intro. To P.A.Rosalie MarzoAinda não há avaliações

- Questions Theory FinalDocumento7 páginasQuestions Theory FinalMair Angelie BausinAinda não há avaliações

- Review On Woodrow Wilson'S The Study of AdministrationDocumento3 páginasReview On Woodrow Wilson'S The Study of AdministrationJeff Cruz GregorioAinda não há avaliações

- PA203-Theory and Practice of Public AdministrationDocumento36 páginasPA203-Theory and Practice of Public AdministrationRigie Anne GozonAinda não há avaliações

- Development Administration Dt. 7.1.2015Documento69 páginasDevelopment Administration Dt. 7.1.2015Jo Segismundo-JiaoAinda não há avaliações

- ReportDocumento11 páginasReportsadaq13Ainda não há avaliações

- 8 PA116 RA7160 LGU Officials in GeneralDocumento69 páginas8 PA116 RA7160 LGU Officials in GeneralJewel AnggoyAinda não há avaliações

- Toward A Practical and Operational Theory of The Budget For Developing CountriesDocumento13 páginasToward A Practical and Operational Theory of The Budget For Developing CountriesducanesAinda não há avaliações

- Theses PDFDocumento225 páginasTheses PDFWilfred LucasAinda não há avaliações

- G2 Session 3 Personality Dimensions-Influences-editedDocumento25 páginasG2 Session 3 Personality Dimensions-Influences-editedCyrus ArmamentoAinda não há avaliações

- Admin - Reaction PaperDocumento2 páginasAdmin - Reaction PaperLeilani Daguio Marcelino-Recosar0% (1)

- 07 - Stability and ChangeDocumento23 páginas07 - Stability and ChangeFrancois Leann EvangelistaAinda não há avaliações

- Principles of Management 1: Foundations of Planning Lecturer: Dr. Mazen Rohmi Department: Business AdministrationDocumento30 páginasPrinciples of Management 1: Foundations of Planning Lecturer: Dr. Mazen Rohmi Department: Business Administrationhasan jabrAinda não há avaliações

- Phases in The Evolution of Public AdministrationDocumento104 páginasPhases in The Evolution of Public Administrationaubrey rodriguezAinda não há avaliações

- Five Faces of Administrative CultureDocumento5 páginasFive Faces of Administrative CultureMarc Russel HerreraAinda não há avaliações

- Q1. Discuss The Features, Functions and Dysfuntion of BureaucracyDocumento11 páginasQ1. Discuss The Features, Functions and Dysfuntion of BureaucracyAkhil Singh GangwarAinda não há avaliações

- A Paradigmatic View of Public Administration - FullDocumento29 páginasA Paradigmatic View of Public Administration - FullPedro FragaAinda não há avaliações

- Public Administration and Development AdministrationDocumento12 páginasPublic Administration and Development Administrationbeverly villaruelAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction of Public Administration PA 101Documento24 páginasIntroduction of Public Administration PA 101Ray AllenAinda não há avaliações

- Woodrow Wilson Study of Administration 1887 Jstor PDFDocumento27 páginasWoodrow Wilson Study of Administration 1887 Jstor PDFallfree4Ainda não há avaliações

- Early Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldDocumento27 páginasEarly Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The Worldamie29_07Ainda não há avaliações

- Service Allocation of 2013 Batch Civil ServantsDocumento89 páginasService Allocation of 2013 Batch Civil ServantsSreekanth Reddy100% (3)

- Social Reform MovementsDocumento8 páginasSocial Reform MovementsSreekanth ReddyAinda não há avaliações

- Handbook of Climate Change and India OUPDocumento1 páginaHandbook of Climate Change and India OUPSreekanth ReddyAinda não há avaliações

- New Scheme IFSE2013Documento1 páginaNew Scheme IFSE2013Sreekanth ReddyAinda não há avaliações

- Foreign Trade Policy 2009-2014Documento112 páginasForeign Trade Policy 2009-2014shruti_siAinda não há avaliações

- Service Allocation of 2013 Batch Civil ServantsDocumento89 páginasService Allocation of 2013 Batch Civil ServantsSreekanth Reddy100% (3)

- Sino-Indian Relations Contours Across The PLA Intrusion CrisesDocumento6 páginasSino-Indian Relations Contours Across The PLA Intrusion CrisesSreekanth ReddyAinda não há avaliações

- Ultra Mega ProjectDocumento8 páginasUltra Mega ProjectSiddharth ManiAinda não há avaliações

- 11 13 EngDocumento9 páginas11 13 EngPushan Kumar DattaAinda não há avaliações

- IB DefenceOffsetGuidelines 050813Documento6 páginasIB DefenceOffsetGuidelines 050813Sreekanth ReddyAinda não há avaliações

- Gatt 1994Documento2 páginasGatt 1994anirudhsingh0330Ainda não há avaliações

- 2668Documento2 páginas2668Imelda RozaAinda não há avaliações

- Direct and Indirect Effects of Fdi On Current Account: Jože Mencinger EIPF and University of LjubljanaDocumento19 páginasDirect and Indirect Effects of Fdi On Current Account: Jože Mencinger EIPF and University of LjubljanaSreekanth ReddyAinda não há avaliações

- Y V Reddy: Indian Economy - Current Status and Select IssuesDocumento3 páginasY V Reddy: Indian Economy - Current Status and Select IssuesSreekanth ReddyAinda não há avaliações

- Media EthicsDocumento11 páginasMedia EthicsSreekanth Reddy100% (2)

- Sample Paper of Upsc EthicsDocumento2 páginasSample Paper of Upsc EthicsKarakorammKaraAinda não há avaliações

- Indian ReformDocumento34 páginasIndian ReformSreekanth ReddyAinda não há avaliações

- Ethics in The History of Indian PhilosophyDocumento12 páginasEthics in The History of Indian PhilosophySreekanth ReddyAinda não há avaliações

- Union Budget 2011-12: HighlightsDocumento14 páginasUnion Budget 2011-12: HighlightsNDTVAinda não há avaliações

- Gold in The Indian Economic System Y.V.ReddyDocumento11 páginasGold in The Indian Economic System Y.V.ReddySreekanth ReddyAinda não há avaliações

- Importance and Challenges of Ethics PDFDocumento10 páginasImportance and Challenges of Ethics PDFDinesh KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Importance and Challenges of Ethics PDFDocumento10 páginasImportance and Challenges of Ethics PDFDinesh KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Nature and Scope of EthicsDocumento10 páginasNature and Scope of EthicsSreekanth ReddyAinda não há avaliações

- CH 05 PDFDocumento17 páginasCH 05 PDFDrRaanu SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Seabuckthorn @sandeepDocumento3 páginasSeabuckthorn @sandeepSreekanth ReddyAinda não há avaliações

- WHO - Climate Change and Human Health - Risks and Responses - SummaryDocumento28 páginasWHO - Climate Change and Human Health - Risks and Responses - SummarySreekanth ReddyAinda não há avaliações

- Cyber Security PolicyDocumento21 páginasCyber Security PolicyashokndceAinda não há avaliações

- Disaster Management VIII Together Towards A Safer India Part-I @sina @maxiDocumento63 páginasDisaster Management VIII Together Towards A Safer India Part-I @sina @maxiblu_diamond2450% (8)

- BT Brinjal Case StudyDocumento26 páginasBT Brinjal Case StudyVeerendra Singh NagoriaAinda não há avaliações

- Nonalignment 2Documento70 páginasNonalignment 2Ravdeep SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Economic Impact of Margaret ThatcherDocumento4 páginasEconomic Impact of Margaret Thatchertaufeek_irawan7201Ainda não há avaliações

- 309 Manila Railroad Company Vs ParedesDocumento2 páginas309 Manila Railroad Company Vs ParedescyhaaangelaaaAinda não há avaliações

- Tyler - Classificatory Struggles. Class, Culture and Inequality Int Neoliberal TimesDocumento19 páginasTyler - Classificatory Struggles. Class, Culture and Inequality Int Neoliberal TimesGonzalo AssusaAinda não há avaliações

- CLASS - 10th Chapter - 3 (Nationalism in India) - HistoryDocumento3 páginasCLASS - 10th Chapter - 3 (Nationalism in India) - HistorybalaushaAinda não há avaliações

- Cultural - Marxism - Who Stole Our Culture - by William S. Lind-6Documento6 páginasCultural - Marxism - Who Stole Our Culture - by William S. Lind-6Keith Knight100% (2)

- Al FarabiDocumento9 páginasAl Farabinshahg1Ainda não há avaliações

- Retailers' Open Letter To Ontario GovernmentDocumento3 páginasRetailers' Open Letter To Ontario GovernmentCynthiaMcLeodSunAinda não há avaliações

- Gender and SocietyDocumento20 páginasGender and SocietyJanine100% (1)

- Harvard World Mun Rules of ProcedureDocumento13 páginasHarvard World Mun Rules of ProcedureŞeyma OlgunAinda não há avaliações

- Ali vs. Atty. Bubong (A.C. No. 4018. March 8, 2005) : FactsDocumento12 páginasAli vs. Atty. Bubong (A.C. No. 4018. March 8, 2005) : FactsAnonymous 5k7iGyAinda não há avaliações

- Presidential Decree No. 1460: June 11, 1978Documento2 páginasPresidential Decree No. 1460: June 11, 1978terensAinda não há avaliações

- Balfour DeclarationDocumento7 páginasBalfour DeclarationaroosaAinda não há avaliações

- Teks Pidato Heng XinDocumento3 páginasTeks Pidato Heng Xinlim jeeyinAinda não há avaliações

- 2022 Wassce Priv Social Studies Paper 1Documento6 páginas2022 Wassce Priv Social Studies Paper 1nelsonAinda não há avaliações

- The Philippine Commonwealth PeriodDocumento18 páginasThe Philippine Commonwealth PeriodZanjo Seco0% (1)

- RA 8173 Act Granting All Citizens Arm Equal Opportunity To Be Accredited by ComelecDocumento2 páginasRA 8173 Act Granting All Citizens Arm Equal Opportunity To Be Accredited by ComelecAdrianne BenignoAinda não há avaliações

- Namma Kalvi 12th History Minimum Learning Material em 217048Documento37 páginasNamma Kalvi 12th History Minimum Learning Material em 217048Arul kumarAinda não há avaliações

- Important Current Affairs 2019 2020Documento63 páginasImportant Current Affairs 2019 2020studentmgmAinda não há avaliações

- The Excelsior School: The Road Not TakenDocumento5 páginasThe Excelsior School: The Road Not TakenDeependra SilwalAinda não há avaliações

- Notes For PSC 100 FinalDocumento5 páginasNotes For PSC 100 FinalDaniel LopezAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter - V Conclusions and SuggestionsDocumento15 páginasChapter - V Conclusions and SuggestionsVinay Kumar KumarAinda não há avaliações

- BLDocumento11 páginasBLOm Singh IndaAinda não há avaliações

- 2020 05 26 IDN NV UN 001 EnglishDocumento2 páginas2020 05 26 IDN NV UN 001 EnglishRappler100% (2)

- 7-Manila Lodge v. CADocumento3 páginas7-Manila Lodge v. CAImelda Arreglo-Agripa0% (1)

- Fan MemberDocumento6 páginasFan MemberMigration SolutionAinda não há avaliações

- Establishment of Military JusticeDocumento1 páginaEstablishment of Military JusticeEsLebeDeutschlandAinda não há avaliações

- HARIHAR Continues To Bring Incremental Claims of Treason Against First Circuit Judges For Ruling WITHOUT JurisdictionDocumento8 páginasHARIHAR Continues To Bring Incremental Claims of Treason Against First Circuit Judges For Ruling WITHOUT JurisdictionMohan HariharAinda não há avaliações

- Tourism and Cultural ChangeDocumento20 páginasTourism and Cultural ChangePilar Andrea González Quiroz100% (1)

- The Structure and Functions of British Parliament.Documento2 páginasThe Structure and Functions of British Parliament.Лена ДеруноваAinda não há avaliações

- (Omar - Noman) Pakistan A Political and Economic HistoryDocumento181 páginas(Omar - Noman) Pakistan A Political and Economic HistoryumerAinda não há avaliações