Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Indus Valley Civilization

Enviado por

Mitchell JohnsDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Indus Valley Civilization

Enviado por

Mitchell JohnsDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 1 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.

doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

Chapter 1 Indus Valley Civilisation This chapter will briefly describe the discovery of the Indus Valley Civilisations, its extent, the history of the region from the preHarappan to post Harappan times, some of the more important sites and the main distinctive features of this culture. Discovery What follows, therefore, is a brief account of the discovery of the Indus Valley Civilisation. In 1827 Charles Masson, a rather colourful character was the first recorded European to visit Harappa on his way to the Punjab after deserting the army of the British East India Company. Four years later, another soldier and explorer Sir Alexander Burnes visited Harappa after mapping the Indus River. The activities and reports of these early explorers eventually came to the attention of Sir Alexander Cunningham the first director of the Archaeological Survey of India. He visited the site twice, once in 1853 and later in 1856. However by the time of his second visit much damage had been done from the removal of bricks used to build the bed for the Lahore-Multan railway in what is now Pakistan. He concluded that the material was related to the ruins of nearby 7th Century AD Buddhist Temples. Some minor excavation followed with some pottery, carved shell and a seal depicting either a one horned bovine animal, or the side-profile (Marshall 1931: 68) of a more probable two-horned animal with only one horn showing- one of the so-called unicorn seals. No more work was carried out until the early 1920s. The first real indications that there was a civilisation rivalling that of Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt came during trial excavations during which Sir John Marshall, the second director general appointed R.Sahni at Harappa in 1921 and at Mohenjo-daro- D. R. Bhandarkar in 1911 followed later by R.D.Banerjee in 1922 (Possehl 1999: 47-62). Later excavations have shown that this culture encompassed many other rivers and extended to a wide area over what are now modern North Western India and Eastern Pakistan. Satellite imaging (BBC, 2002) has also revealed previously thought mythical Saraswati River flowed along side of some the settlements of this culture. Its mature, developed period lasted for only about 500 years between c. 2400 1900 BC. Later the culture became known as the Harappan Civilisation in order to de-emphasise what early archaeologist thought was a civilisation solely geographically linked to the Indus River and also to remove the false assumption that the Indus Valley Civilisation was a superior, non-Indian culture. Today, the terms Indus Valley Civilisation or Harappan Civilisation are interchangeable and largely free of imperialist or anti-imperialist sentiment. Extent Wider excavation in India, that started after the independence of India and Pakistan and still continues sporadically today, revealed that there are, at the current count, possibly over a thousand Harappan, or at least Harappan related unconfirmed sites (Possehl 1999: 727-835) spanning modern Pakistan and North West India and other major rivers, deltas and coastal areas. The major rivers included the Indus, Saraswati, Hakra-Ghaggar and their tributaries. This makes it the most geographically extensive of all ancient civilisations thus discovered. Far larger, in fact, than both Egypt and Mesopotamia together- approximately 1,300,000 square miles

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 2 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

(2,092,147 Square kilometres). MESOPOTAMIA */

/* NEED AREAS OF EGYPT AND

The following satellite photograph (Harappa.com 1996-2001: harmap1.jpg) shows an overlay of the range of the Indus Valley Civilisation.

And this map (Harappa.com 1996-2001: oldworld.jpg) shows the geographical extent of the Harappan Civilisation compared to other Old World Civilisations.

A Brief History First, we should look at the general place of Harappan culture within the larger context of the Old World Civilisations and what events were taking place elsewhere to gain some kind of historical perspective-

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 3 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

Indus Civilisation in the Chronology of Old World Civilisations *3200 BC Menes and the First Dynasty of his successors the pharaohs in Egypt. **3200 BC Indus Valley Civilisation starts. *2500 BC The Egyptian Pyramids built. **2300-2000 BC Cultural exchange between the Indus Valley civilisation and Mesopotamia (present day Iraq) is especially prominent *2000 BC The Code of Laws of Hammurabi in Babylonia in the Valley of the Tigris and Euphrates. **1600-1500 BC Aryan invasion of Indus Valley (this theory has now been largely abandoned). **1600-1000 BC Early Vedic Period **1550 BC Writing disappears with destruction (now thought to be a gradual disintegration) of Indus Valley Civilisation. (*worldhistorychart.com, **Evan evansville.edu, Mathur 2004) And within this brief time-span we look at the Harappan Culture itselfA Brief 7000 BC 6000 BC 4000 BC 3200 BC 2400 BC 2500 BC 1900 BC and Very Approximate Chronology of The Harappan Civilisation Pre-Harappan Baluchistan Large farming villages on the Indus Plain Fortification of larger communities The Early Indus period begins Harappan cities established The Mature Harappan period Decline is seen in many aspects of the archaeology

We will now briefly discuss each major period, from what came before, what were the main landmarks of the Harappan civilisation and what happened after its presumed fall as, to date, no evidence has yet been found of its continuation into the historical period. Pre-Indus c.9000 BC marked the end of the Ice Age and the beginning of the current Holocene epoch. Hunter-gatherers in this region did not practice cultivation or build permanent settlements and all that they have left behind are a few scattered microliths. This is very different from the rest of Western Asia where we see village-based hunter-gatherers. There seemed no gradual transition from the Palaeolithic to the Neolithic (Mithen 2003: 408). It is possible of course that the evidence for this transitional period is yet to be uncovered. At around 8000 BC the first peoples arrive on the Indus plains from, perhaps, the Bolan Pass from Western Asia. They settle to become small farmers and this is the precursor for the first agricultural settlements. From c.7000 to c.4500 we see settlers at the Bolan Pass arrive and over the next few thousand years develop an agricultural village called Mehrgarh- the first such village in South Asia. The Rise The rise seems to have occurred for the most obvious of reasons- good farming land. Along with many small rivers, the huge Indus and

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 4 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

Saraswati rivers flowed through the land creating fertile alluvial plains from yearly silt deposition. There were also dense forests which along with smaller animals were also large enough to sustain elephants, water buffalo, rhinoceros, various deer species, pigs, humped cattle and tigers to predate on them. Along with this bountiful environment, however, the peoples of this region would have to contend with the yearly inundation/drought cycles; necessity being the mother of invention- they eventually did this by becoming experts in the control of water (NHK 2000). The Fall Various theories accounting for the eventual collapse of the Indus Valley Civilisation have been put forward over the years. Everything from invaders from the north- the Aryan invasion theory of Friedrich Max Mller- now out of favour, to over-exploitation of natural resources leading to erosion and poisoning of the land by rising salt levels through over-irrigation. Other environmental catastrophes such as the demise of the Saraswati, the changing course of other rivers and climactic change might also have been a factor. The Aryan invasion theory has, in fact, been used by some scholars to tie in events of the Sanskrit Rg Veda that supposedly documented this invasion. There is no real evidence pointing to this, however and this seems be the product of trying to make a religious text fit the archaeology. Biblical scholars have tried to do the same for years with the archaeology of the Near East and while the Bible is a valuable historical document, it is also a story and not completely composed of fact. Another problem with using religious texts is that the chronologies of these documents have not been fully worked out. Also there is some component of nationalism with both sides of the border competing to be more Harappan than the other. Most scholars today seem to attribute a combination of environmental factors to the slow decline. Whatever the case, and we will probably never be completely sure, this decline can be seen c.1900 BC. Structures become poorly constructed with heavy re-use of material, which indicates a shortage of natural resources such as clay for bricks and timber for building frames. Pottery styles start to diverge greatly and within a few hundred years the culture had virtually disappeared. Post Indus A gradual geographical migration took place south east towards the more fertile Gangetic plain. One should remember, however, that perhaps the civilisation did not end and possibly did influence the development of early Hinduism. For instance, there seems to be a clear delineation in the location of areas set aside for specific crafts in the Harappan cities. This seems reminiscent, though by no means conclusive, of the caste system (Scarre and Fagan 2003: 159) of the later historic period. Representative Sites of the Pre-Harappan, Harappan and Post Harappan Periods The following map shows the main socio-economic and cultural flows as well as the important sites of the Harappan culture (Harappa.com 1996-2001: indusmap.gif)-

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 5 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

Pre-Harappan First Evidence of Agriculture- Mehrgarh c.7000 to 4500 BC (Harappa.com 1996-2001 and DAndrea 2004: Mehrgarhmap.jpg)

Mehrgarh, a Neolithic farming village first excavated by a French team led by Jean-Francois Jarrige in 1974 (Chakrabarti 1999: 120-126) was an important location as it is in the Bolan Pass at the top of

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 6 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

the Kaachi Plain where the Iranian Plateau meets the Indus floodplain and many ancient trade routes intersect here. The site is spread over about 200 hectares on the fertile banks of the Bolan river. It is situated in the Baluchistan area in modern day Pakistan. Mehrgarh supported a population of around one hundred on the fertile Bolan river plain. The occupants constructed rectangular clay/chaff mud-brick buildings and storage rooms as can be seen in the following photograph (Jarrige: . Mehrgarh neo.jpg)-

Annual flooding of the Bolan river made the river banks rich in the clay used for bricks and spread fertile silts onto the floodplain so that crops could be cultivated successfully. This site, in fact, shows the first evidence of agriculture in South Asia- both domesticated live-stock was raised and plant varieties were cultivated here. From analysis of the chaff in the bricks we know that the inhabitants grew wheat and barley. Zooarchaeological evidence from early levels show large numbers of non-domesticated species, this changes in later levels where domestic species are more prevalent. Remains of domestic live-stock include cows, sheep and goats. This site is, in fact, one of many in Baluchistan. Though none are as elaborate as Mehrgarh, they do indicate a move towards village dwellings that was to precede the sophistication of the nearby Harappan Civilisation. Art from Mehrgarh ahs been compared to Harappan art, which lends credence to the idea of the gradual emergence of Harappan society from the wellspring of earlier cultures as is evidenced from the following figurine from Period VI c 3000 BC at Mehrgarh (Helmes: mehrgarh1.jpg)

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 7 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

One should finally note that though Mehrgarh started as a pre-Indus site, it was still occupied well into the Harappan age. Jarriges excavations have, to date revealed several levels of occupation. Some radio carbon work was also completed by French teams (Jarrige 1978, Lechevallier 1984 and Mathur 2004: RC Dates For Mehrgarh)RC Dates c.7000/c. 6500 to c.6000 BC Period Ia Site MR3 Structures Mud brick houses Storerooms, cemeteries, open areas ,, ,, ,, Artefacts Unbaked clay figures, pre-ceramic

,, ,, Mid point c.5500 BC

Ib Ic IIa

,, ,, MR4

Mid point c.5000 BC Mid point c. 4500 BC

Iib Iic III

,, ,, ,,

,, ,, ,,

,, ,, Straw reinforced pottery and polished plain red pottery, first cylinder seal ,, ,, Painted pottery with animal designs and first evidence of copper smelting Painted pottery with geometric decoration and terracota female figurines Painted pottery with white pigment, first grey-ware and human figurines

IV

,,

,,

,,

,, AlsoPottery firing area and

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 8 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

VI

,,

childrens cemetery ,,

VII Kot Diji phase VIII (In Sibiri , just S. of Mehrga rh)

,,

,, AlsoLarge platform

,,

Cemetery, domestic structures. Open areas

Painted pottery- blackon-grey ware, Quetta red-ware, Nal polychrome and compartmented stamp seals. Painted pottery- blackon-grey ware, late Quetta ware, Kot Diji ware , male and female figurines Central Asian pottery, shaft-hole bronze axe and cylinder seal.

The Kulli Complex 2500-2000 BC- Nindowari This culture located in the Kolwa, Makran and southern Kalat in Pakistan was excavated initially by Sir Marc Aurel Stein in the early 1900s. Sites consisted of rows of houses built of massive stone blocks along a grid-like pattern of streets. Again, as in the case of the Indus cities, the layout seems planned. Nindowari is in south Balochistan and was discovered by B. deCardi and later excavated by J.F. Jarrige and J.M.Casal. The site has a central mound rising c.80 ft above the Porali River (Hirst, 2004). As with other Kulli complex sites it featured monumental structures and massive public buildings Although generally contemporary with the Harappan Civilisation, it is not clear whether it was an upland extension of Harappan style cities or a culture in its own right. (Hirst, 2004). It remained a viable city into the main period of Harappan development from c.2500 BC and ends at c.2000 BC, just before the demise of the Harappan age at c. 1900 BC. As well as monumental structures we find artefacts including red-ware pottery and terracotta figurines such as these 6.6 cm tall turkeylike avian busts from Nindowari c 2300-2000 BC (BC Galleries 2004: e1258.jpg)-

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 9 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

And this red ware pottery cup with designs in dark brown pigment also from Nindowari c mid-late 3rd millennium BC Diameter 9.5 x Height 6 cm (BC Galleries 2004: e1188.jpg)-

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 10 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

Early Harappan Kot Diji late 4th Early 3rd Millennium BC c.3000 BC- c.2500 BC (Harappa.com 1996-2001 and Mathur 2004: KotDiji.jpg)

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 11 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

When Mortimer Wheeler published his book Civilisations of the Indus Valley and Beyond in 1966 Kot Diji was thought to be a pre-Indus site (Wheeler 1966: 86). Subsequent excavation by has shown this to be both pre-Harappan with a gradual evolution towards ...characteristic Harappan forms... (Allchin and Allchin 1982: 145). In other aspects the site is quite remarkable. The perimeter wall is particularly heavily built. Theories include its use as defence against violent seasonal floods or perhaps protection against attack by enemies. Interestingly, at the end of the early period there is evidence of two major fires, after this the material culture becomes predominantly Harappan in character. Conquest or simply starting anew? The main periods at are shown below (British Museum Teaching Resources 2004: Periods at Kot Diji)3180 2880 2520 (2nd great fire) 2700 Above RC approx. dates Kot Diji Defence walls (45m high)lower course is limestone rubble while upper course is of mud brick Located in agricultural ly productive land Defence walls probably for floods Wheel made pottery; copper

Mature Harappan Period

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 12 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

Harappa c.2600 1800 BC (Harappa.com 1996-2001 and Mathur 2004: Harappa.jpg)

Harappa is the second largest site of the Harappan Civilisation. It is a good site to examine, even somewhat briefly, as it has been excavated over many years. A conglomeration of American universities continues excavation to the present day. It had an estimated population of around 23,500 and was 150 hectare size. Its planned appearance is consistent with the general Indus scheme of citadel mound, lower town and surrounding walls, just like the largest city Mohenjo-daro. The citadel had square towers and bastions. There appears to have also been a granary with areas for threshing. For construction of housing- building material included burnt bricks for drains, wells and bath rooms, large sun dried bricks (28 x 14 x7 cm) for filling, mostly in the ratio we mentioned earlier 4:2:1. Timber was used to build flat roofs and frames. There were five basic house types- single room tenements, houses with courtyards and up to 12 rooms, great houses with several dozen rooms and several courtyards. Most of the larger dwellings had private wells. Hearths are common in rooms. Every house had a bath room with waste water chutes leading to drainage channels. There were brick stairways that connected to the upper floors. Houses were built with a perimeter wall and adjacent houses were separated by a narrow strip of land. The following shows the site plan for Harappa (Harappa.com 1996-2001: harappamap.gif)-

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 13 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

Excavations at Harappa Site Dates Harappa c.1856-? Harappa 1921-1929 Harappa 1940 Harappa 1986 Harappa 1987 Harappa 1988 Harappa 1989 Harappa 1990 Harappa 1992 Harappa 1993 Harappa 1995-1998 Harappa 2000-2001

Excavated By Sir John Cunningham Daya Ram Sahni and Madho Vats Harappan Research Project Harappan Research Project Harappan Research Project Harappan Research Project Harappan Research Project Harappan Research Project Harappan Research Project Harappan Research Project Harappan Research Project

(HARP) (HARP) (HARP) (HARP) (HARP) (HARP) (HARP) (HARP) (HARP)

Later, more extensive digging at Harappa revealed an entire sequence that spans the whole history of the Indus Valley Civilisation. Even though it is much less visually impressive than Mohenjo-Daro, it is for this reason that it is one of the most important sites today. The major periods of development at Harappa (Kenoyer and Meadow 2001)Period Period 1 Period 2 Period 3A Era Ravi aspect of the Hakra Phase Kot Diji (Early Harappa) Phase Harappa Phase A Years 3300 BC - c. 2800 BC c. 2800 BC - c. 2600 BC c. 2600 BC - c. 2450 BC

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 14 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

Period 3B Period 3C Period 4 Period 5

Harappa Phase B Harappa Phase C Harappa/Late Harappa Transitional Late Harappa Phase

c. 2450 BC - c. 2200 BC 2200 BC - c. 1900 BC c. 1900 BC - c. 1800 BC(?) c. 1800 BC (?) - < 1300 BC

Mohenjo-daro 2600 1900 (Harappa.com 1996-2001 and Mathur 2004: Mohenjodaro.jpg)

Mohenjo-daro is the largest of all the cities found so far. Estimates of population range from 35-41,000 and occupied roughly 200 hectares. It was built in the classic Harappan style like Harappa, though it was larger. Like Harappa it has the covered drains and sophisticated use of engineering for the control of water (Harappa.com 1996-2001: mohdrain.jpg)-

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 15 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

and neatly built houses (Harappa.com 1996-2001: mohhouse.jpg)-

It also had the same general layout as can be seen in this plan (Weaver 1966)-

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 16 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

Sir Mortimer Wheeler excavated this site extensively during the 1950s and 60s. Based on the information he had at the time and his background in Roman archaeology in the United Kingdom he made a number of assumptions, some have turned out to be correct, others not so. But many of the errors made by early Harappan archaeologists are understandable given the lack of knowledge of transitionary and early sites like Mehrgarh and Kot Diji. Interesting features of this site include a rather mysterious structure. This brick structure sealed with bitumen is 12 x 7 x 3 metres. Due to its swimming pool like appearance it is known as the "great bath". There have been various theories as to what the original purpose of the structure was- recreation, hygiene, ritual purification, however, like some much else in this unique culture, its definite function is still unknown (Harappa.com 1996-2001: greatbath.jpg)-

Excavations at Mohenjo-daro Mohenjo-daro 1922 Mohenjo-daro 1922-1927 Mohenjo-daro 1922-1923 Mohenjo-daro 1927-1931 Mohenjo-daro 1932-1934 Mohenjo-daro 1950 Mohenjo-daro 1965 Mohenjo-daro 1968 Mohenjo-daro 1986

R.D. Bannerjee Sir John Marshall Vats and Banerjee Mackay Q.M. Moneer and K.N. Puri Sir Mortimer Wheeler George F. Dales Sir Mortimer Wheeler George F. Dales and Jonathan M. Kenoyer

Lothal 2100 - 1900 BC (Harappa.com 1996-2001: Lothalmap.jpg)

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 17 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

Lothal is thought to be a port city of the Harappan Civilisation , as can be seen from the satellite photograph, it lies within access of the Arabian Sea via the Gulf of Khambat (WWF: im1403a_lg.jpg)-

The town is located near a tributary of the Sabarmati river, east of the said main river. Lothal is unique in that here we see a good evidence of a Harappan port city. It differs somewhat from the classic Harappan layout due to this theorised function. There is a large, thick surrounding wall probably built as a defence against flood. What really marks it out is the 217 x 37 x 4.5 m dockyard, connected by a series of artificial channels. Heavy pierced stones of a type still used as anchors by local fishermen have also been found just outside the dock area which adds credence to the dock theory (Allchin and Allchin 1982: 173) as does nearby storage structure foundations and what looks like a wharf area. However, like so much with Harappan

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 18 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

structure, there is an alternative theory. According to another researcher, it could have been a fresh water reservoir given the salinity of the nearby river (Leshnik 1979: 203-212). The proposed dock can be seen in the site plan below (Rao 1979: maplothal.jpg)-

And here is Lothal again, somewhat artistically portrayed in this painting as envisaged by the Archaeological Survey of India (Harappa.com 1996-2001: 1.jpg)-

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 19 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

It must be said ,however, that the site was located ideally for trade along the western coastal area of the Harappan civilisation. It was ideally placed as a port for ships plying both inland and coastal trade. It was also ideally placed with access to the Arabian Sea and towards the Mesopotamian sphere of influence for purposes of trade of which there is a great deal of evidence. We will look at Lothal in far greater detail in a later chapter. The main period of this site is shown below (British Museum Teaching Resources 2004: P Periods at Lothal)2100-1900 BC Lothal Trading station and dock. Centre of carnelian bead manufacture Dock is a rectangle basin with a spillway and locking device to control the inflow of tidal wave and permit automatic de-silting of the channels. Raised platforms with ventilating channels were probably granaries or warehouses. Specialist workshopscopper, gold and beads.

Distinctive Features of Harappan Civilisation Town Planning Subsequent larger scale excavations at Mohenjo-daro and Harappa revealed a similarity in town planning (Wheeler 1966: 19). Cities seemed to share uniformity in layout making the civilisation unique amongst the earliest societies. The layout of the towns generally comprised of a monumental citadel within a walled lower town with individual dwellings or houses. Another unique feature of this society was mastery of the use of water. Highly efficient covered drainage systems removed sewage from housing, reservoirs supplied fresh water, irrigation systems helped to grow crops and seated toilets lay above waste chutes which acted as a flush system- all thousands of years before Rome. Of more particular interest in the context of this thesis is the site at Lothal which included a dock. We will expand on this a little later in this chapter, then look at the site in much greater detail in a later chapter. Typology of Artefacts The shared typology of the civilisations artefacts including beadwork, pottery, clay and bronze statuary- both crude and fine, toys, stone, copper and bronze tools mark it as a distinct culture sharing a distinct time-span. This is particularly the case for the Mature period. It could be described succinctly as a sophisticated chalcolithic ceramic culture, i.e. they planned their cities, made pottery, could cast copper and bronze, yet still worked with stone tools too. The types of artefacts found were so distinct, in fact, that early excavators, used the type fossil technique borrowed from palaeontology and applied it to archaeology in order to identify other Indus sites. This inevitably led to some mistakes. It gave the impression of the Indus Civilisation rising from nowhere and in isolation and then disappearing. We now know this to be untrue from the work on Baluchistan archaeology, Mehrgarh, Kulli Complex and Kot Diji sites. At the time, however, at the time it was a novel application of a technique borrowed from another branch of science.

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 20 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

Standards, Measurements and Weights The Indus Civilisation adopted precise standards of measurement. In building. Larger bricks were in the ratio of 4:2:1. There was also a standardised system of weights , as is illustrated below Harappa.com 1996-2001: Indusweights.jpg)-

which would be essential for mass commerce and trade- Weights were based on units of .05, 0.1, 1.2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200 and 500, with each unit weighing approximately 28 grams, similar to the English ounce or Greek uncia. (Mulchandani 1998: par 28) Writing A written pictographic language also existed as is evidenced by the Indus scripts written on clay seals. We see rectangular Harappan seals in the Indus region, round Harappan seals in Bahrain and one combination Harappan script/Akkadian illustration cylinder seal in Mesopotamia, which is further evidence of intercultural contact. The scripts appeared as early as c.3300-2800 BC in the Ravi Phase (Kenoyer and Meadow 2001: Table 1) at Harappa. We can assume with some degree of confidence that these were used in trade to mark ownership. However, the Indus seals are not extensive, there is no Rosetta stone-like object and it is different to any other known language. However, more recent work in some of the many c.80,000 grave mounds in Bahrain at present hopes to uncover such an artefact. This enigmatic script remains decipherable to this day, despite the efforts of notable scholars as Asko Parpola, Iravatham Mahadevan and many others. The language of the writing has been variously theorised at various times to be proto-Indo-European, proto-Indo-Aryan or Dravidian. It is now thought to be logo syllabic (D'Andrea, 2003: 23), i.e. a mixture of symbols- some representing words others represent sounds and boustrophedon in style (D'Andrea, 2003: slide 34), i.e. each line alternates in direction and is written with mirrored letters on the lines going backwards.

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 21 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

Intriguingly we do have a seal that contains both Akkadian art and Indus pictographs found in Afghanistan (Schoyen Collection 2004: ms2645.jpg)-

which is surely more evidence of intercultural links between the old world civilisations- in this case Mesopotamia and the Harappan Civilisation. Trade Imports included gold from lower peninsula India, e.g. Karnataka, silver from Afghanistan and Iran, copper from Rajasthan, lapis lazuli from N.E. Afghanistan and turquoise from central Asia or Iran. Further proofs of intercultural trade are seals from the Persian Gulf and Mesopotamia. Exports probably included manufactured items such as faience beads. These are decorative tin-plated terracotta beads and worked copper, gold, carnelian and pottery. From Sumerian texts Dilmun would seem to be the modern Bahrain and may have served as a link to the Indus Valley Civilisation which Akkadian texts may refer to as Meluhha (Allchin and Allchin 1982: 188). Lothal with its sophisticated dock structure, sheltered location, access to both inland deltas and the Gulf of Khambat and, thence, the Arabian Sea, the Gulf of Oman and the Persian Gulf was ideally placed to trade with other Indus cities as well as along the coast all the way to either Bahrain or further into the heart of Mesopotamia. As well as the simple carts and given that Lothal perhaps possessed an elaborate dock, one could assume that some form of small ship or large boat may have been used for carrying trade goods. Perhaps an idea of what one of these early ships looked like can be deduced from the following artefacts. First we have this Moulded tablet illustrating a boat from, Mohenjo-daro (Harrapa.com 1996-2001: Industablet.jpg)-

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 22 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

As well as this toy boat from Harappa (Harappa.com 19962001:Industoyboat.jpg)-

And these types of vessels are still used locally today (Harappa.com 1996-2001: bullockcart.jpg)-

In 1978 the Norwegian anthropologist Thor Heyerdahl built the reed boat Tigris, which he sailed from the Tigris to the Indus delta in Pakistan and on to Africa. He was trying to prove the possibility of Mesopotamian-Indus migration; this theory has now largely been discounted as there is no reason to think that the Indus Civilisation was not purely indigenous. However, it did prove that vast sea journeys in small boats were possible. By the time of the mature Indus period the boats were probably even more sea-worthy than Heyerdahls vessel. Even without the other archaeological evidence that confirms the presence of intercultural trade, the fact that the Harappans possessed such viable marine technology, made trade and cross-cultural contact between the two civilisations a virtual certainty. The following is a picture of Thor Heyerdhals vessel, the Tigris (Blair, Betty and Storfjell 2003: 111_367_thor_tigris_ba.jpg)-

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 23 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

A brief aside concerning overland trade- at the time, the main pack animals of the Indus region was the onager- Equus hemionus, the assEquus asinus. The bones of an onager have been found at Surkotada and those of an ass at Kalibangan. There have been claims that the horse- Equus caballus was also present as there are terracotta figurines of horses found at Lothal. Many of the largest Indus sites, including Mohenjo-daro and Harappa have camel bones, but whether they are Dromedaries- Camelus dromedarius or BactrianCamelus bactranus is still in question. (Possehl 1999: 185-186). Bullock carts would have been used for very short transportation and general agricultural use. Major overland trade routes included the Bulichistan/Bolan pass route onto the Iranian plateau and the Chiba Pass into Afghanistan. Most of the evidence for the use of these animals is assumed from modern practices of todays population. For instance, the same type of bullock carts that the Harappans used (see Industoycarts.jpg later in text) is used in the region today and is indeed pulled by bullocks. Thus, similar assumptions have been made about pack animals. More convincingly, however, we find pre-Indus evidence from c.3,000 BC in peninsular India of anchylosis (stiffening) of the hock joints in cattle. This is most commonly associated with livestock that have been used as pack or draft animals (Hutchinson 1976: 131). Industry Industrial produce included ceramics, the beads we discussed earlier, flint making and some copper and bronze smelting. Cotton textiles were also known to have been produced from scraps found at Mohenjodaro (Allchin and Allchin 1982: 191). Religion/Burial The Priest King bust- variously described as brutal (Marshall Cavendish 1969: 18) or meditative. There is no indication that this is a religious artefact. Scholars have debated on whether this is a deity, priest or important personage. Whatever the case, the bust is finely carved and obviously of some importance and value to the maker. Priest King from Harappa (Harappa.com 1996-2001: priestking.jpg)-

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 24 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

Fire-altars that could be associated with Hinduism have been found at Kalibangan (Allchin and Allchin 1982: 183). Some other researchers also ascribe traces of fire-pits to ritual as is the case for the site of Rakhigarhi (Dhavalikar and Atre 1989). The Great Bath at Mohenjo-daro is thought to be a feature of ceremonial bathing which is an aspect of Hinduism. The Great Bath at Mohenjo-daro (Unknown 2004: bath.jpg)-

The bath has also been included in the following axonometric reconstruction which shows how it may have originally looked (Weaver 1966: see Wheeler 1966: 16)-

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 25 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

We also find a seal with a man, shaman or priest in what looks to be a Yogic position (Harappa.com 1996-2001: yogiseal.jpg)-

Despite the presence of these, perhaps, proto-Shivaic figures in the art, one should point out that all the above connections to Hinduism are purely conjecture at this point. In addition a word of caution should be added in that are, so-called Yogic forms in many different cultures. One of the more famous examples is Celtic representation of the Celtic god Cernunnos in a similar Yogic position depicted on a panel of the Gundestrup cauldron (National Museet / National Museum of Denmark 2001: DkGundestrupCauldron2.jpg)-

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 26 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

The cauldron was found in a dried peat bog at Raevmose, Jutland in Denmark. It was possibly booty or a traded item from the the British Celts. However, similarity in form does not imply a similarity in the deeper meaning. In fact, there are many symbols, art, and technology that have arisen separately in many different cultures. Many of these similarities could be ascribed to parallel though separate cultural evolution. Take for instance the parallel evolution of pyramidal structures in South America, Mesopotamia and Egypt. There were also burials that, of course, are not part of Hindu tradition. Grave goods are also present in a number of graves. At Harappa there is a burial of a woman and infant together with some graves goods. Burial of woman and infant, Harappa (Harappa.com 19962005: Indusfemaleburial.jpg)-

Agriculture Crops Rice, mustard, castor, cotton, kodom (a variety of millet) and gram have wild relatives in India, thus its domesticated counterparts are probably of wholly Indian origin (Hutchinson 1976: 129-130). Cotton, quite possibly could have been used for trade as some woven and dyed cotton cloth has been found at Mohenjo-daro. Craft workshops, including dyers shops, have also been found at Mohenjo-daro, so we could assume that finished textile products were wholly domestically produced (Allchin and Allchin 1982: 179).

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 27 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

Most importantly wheat and barley, but also to a lesser extent- peas, chick peas and lentils grow wild in West Asia, but have been grown domestically in India from before earliest records, so we could say that they were probably introduced as wild species from West Asia (Hutchinson 1976: 130). Wheat and barley would have been fertilised by alluvial silt and watered via the rather singular Harappan irrigation systems to make use of the seasonal deluges preceding the regular droughts. Sorghum, millet and sesame, in the absence of any wild domestic varieties must be regarded as being introduced to India from Africa (Hutchinson 1976: 130). Live Stock Wild ancestors of sheep, goats and cattle were already being used by man from evidence found in the caves at Aq Kupruk in the Hindu Kushthe mountains that separate Pakistan from Afghanistan, as early as 16, 000 years ago. This would strongly indicate that even by preIndus times sheep, goats and cattle were already long domesticated (Allchin and Allchin 1982: 97). Evidence /*WHAT EVIDENCE*/ from the seals and animals remains at various sites that other animals were hunted. Art Following on from discussing cotton in agriculture, Bridget and Raymond Allchin of Cambridge speculate that perhaps part of the reason why so little of the Harappan culture is left to us is that they may have expressed artistically in their use of textiles/*REFERENCE YET TO BE CONFIRMED*/. As well as the priest king bust, there are other skilfully carved pieces as well as seals, a few beautiful bronzes, such as this, socalled Dancing girl bronze from Mohenjo-daro (Possehl 2002: bgirl.jpg)-

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 28 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

The dancing girl was produced using the lost wax process that is still used by Indian metalworkers today (Scarre and Fagan 2003: 158). There are also numerous clay figurines like this female figurine from Harappa (Harappa.com 1996-2001: Indusgoddess.jpg)-

and toys, in fact, the type of carts depicted in toys below are still used in the region today (Harappa.com 1996-2005: Industoycarts.jpg)-

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 29 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

The Harappans also displayed considerable skill in the previously discussed beadwork, such as this.exquisite little pot from Period 3c of the Harappa Phase, that is- c. 2200-2000 BC. It contained fired steatite beads similar to Ravi phase faience beads. The beads themselves are made from the seed of the Coix lacrymajobi. It was found in excavations at Harappa on Mound E in 1998 (Harappa.com 19962005: 62.jpg)-

The following unicorn seal was excavated by Ernest Mackay at Mohenjo-daro between 1927 and 1931. It is of the late Period IB, c 2000 BC (Harappa.com 1996-2005: 1.jpg). An additional point to make is on the subject of the, so-called, unicorn seals that depict a one-horned bull or water buffalo. It is my opinion that this was simply the Harappans experimenting with the most effective way of leaving a clear and easily discernible impression of the bull clearly in the soft surface material of the seal clay. Much in the same way as the ancient Egyptians would purposefully misrepresent the proportions of the human body in order to more clearly represent three dimensional objects on a two dimensional plane.

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 30 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

Politics and Warfare From the archaeology of several sites we know that some large houses even the smallest dwellings were excellent latrine, bathing and water supply. This greater social equality than other cultures of the

although there are well built with could indicate time. f

Administration centres possibly at Mohenjo-daro and Harappa given that these seem to be the largest sites.. There appears to have been no warfare or, more precisely, no real physical evidence of warfare has been found to date. There is a general scarcity of weapon finds. There also appears to have been little sign of violent death in skeletal remains including the murder remains found in Mohenjo-daro and a more thorough forensic analysis really needs to be completed at this site. It could be that geographical isolation could have helped achieve this, but this does not explain a lack of internecine conflict. This has led some researchers to the assumption that the Harappans were a peaceful people. More work needs to be completed in this area before any firmer conclusions can be reached. Factors that could conflict with this view are the heavily built defensive walls of the sites, though whether this was for defence against floods or more human enemies is debatable. Also there are the burnt levels at Kot Diji that may one day disprove this supposed lack of violent conflict. Conclusions We can say that the rise of the Harappans was a gradual development from pastoral nomads to farming villages in Baluchistan, spreading to the Indus plain and ending in the refinement of Harappan cities. Uniquely among Old World Civilisations towns were planned to a similar formula that included a surrounding wall, a citadel, granaries, housing and sophisticated water control systems. This

(C)Roy Mathur, University of York, UK 14/12/05 2:11 PM, Page 31 of 31 C:\Documents and Settings\Roy\My Documents\data\projects\phd\thesis\chapter 1\chapter 1.doc From: The Distribution and Development of Indus Civilisation Ports in the Gujarat

only varied in terms of specialised functions, e.g. a port or administration centre. Agriculture was organised with granaries for storage, animals were domesticated as represented on seals and use of irrigation systems widespread. Long distance trade existed as is evidenced from presence of nonlocal material, the Akkadian/Indus intercultural seals and references in Sumerian texts. There was a shared typology of artefacts such as- elaborate beadwork, pottery, statuary (both crude and sophisticated), toys, stone, copper and bronze tools and a common seal script written language. Most evidence suggests that there was no sudden fall, rather a combination of environmental factors was the most likely reason for decline. We are also left with a general consensus of opinion among most scholars that the legacy of the Harappans was to influence the development of early Hindu culture.

Você também pode gostar

- Harappan CivilisationDocumento23 páginasHarappan CivilisationMadhuleena deb roy100% (1)

- Mohenjo - Daro Floods:: A Reply'Documento9 páginasMohenjo - Daro Floods:: A Reply'lou CypherAinda não há avaliações

- Indus Valley CivilisationDocumento72 páginasIndus Valley Civilisationhaley noorAinda não há avaliações

- Study of The Indus Script PDFDocumento39 páginasStudy of The Indus Script PDFparthibanmaniAinda não há avaliações

- Indus Valley Civilisation - WikipediaDocumento41 páginasIndus Valley Civilisation - WikipediaAli AhamadAinda não há avaliações

- Etymology: City"), andDocumento37 páginasEtymology: City"), andDawood AwanAinda não há avaliações

- Ancient India: A Captivating Guide to Ancient Indian History, Starting from the Beginning of the Indus Valley Civilization Through the Invasion of Alexander the Great to the Mauryan EmpireNo EverandAncient India: A Captivating Guide to Ancient Indian History, Starting from the Beginning of the Indus Valley Civilization Through the Invasion of Alexander the Great to the Mauryan EmpireAinda não há avaliações

- Indus Valley Civilization ThesisDocumento6 páginasIndus Valley Civilization Thesisewdgbnief100% (2)

- Ancient India for Kids - Early Civilization and History | Ancient History for Kids | 6th Grade Social StudiesNo EverandAncient India for Kids - Early Civilization and History | Ancient History for Kids | 6th Grade Social StudiesAinda não há avaliações

- 61f36aa2be60120220128040138UG HISTORY - HONS - PART-1 - PAPER-1 - INDUS VALLEY CIVILIZATION - PART-4Documento24 páginas61f36aa2be60120220128040138UG HISTORY - HONS - PART-1 - PAPER-1 - INDUS VALLEY CIVILIZATION - PART-4jasminebrar302Ainda não há avaliações

- Assignment No.1Documento35 páginasAssignment No.1Ali AkbarAinda não há avaliações

- Indus River Valley CivilizationsDocumento4 páginasIndus River Valley CivilizationsM4 TechsAinda não há avaliações

- Indus Valley Civilization: Presented byDocumento21 páginasIndus Valley Civilization: Presented byAravind EcrAinda não há avaliações

- Indian Church HistoryDocumento59 páginasIndian Church HistoryKyaw thant zinAinda não há avaliações

- Indus Valley CivilizationDocumento4 páginasIndus Valley Civilizationsanam azizAinda não há avaliações

- Indus Valley CivilisationDocumento29 páginasIndus Valley CivilisationVibhuti DabrālAinda não há avaliações

- Indus Valley Civilisation - WikipediaDocumento218 páginasIndus Valley Civilisation - WikipediarajasahasurojitsahaAinda não há avaliações

- Study of The Indus Script - Special Lecture-Asko ParpolaDocumento62 páginasStudy of The Indus Script - Special Lecture-Asko ParpolaVeeramani ManiAinda não há avaliações

- TIMELINE - An Analysis of INDUS VALLEY Civilization Evidences, Findings and PapersDocumento11 páginasTIMELINE - An Analysis of INDUS VALLEY Civilization Evidences, Findings and PapersSamrat ChatterjeeAinda não há avaliações

- The Indus Valley CivilisationDocumento3 páginasThe Indus Valley CivilisationTwinkle BarotAinda não há avaliações

- The Harappan CivilizationDocumento6 páginasThe Harappan Civilizationzxcv2010100% (1)

- INDUS VALLEY PPT by VaibhavDocumento20 páginasINDUS VALLEY PPT by Vaibhavsandhaya1830Ainda não há avaliações

- The Indus Valley Civilization Was A Bronze Age CivilizationDocumento3 páginasThe Indus Valley Civilization Was A Bronze Age CivilizationChinmoy TalukdarAinda não há avaliações

- Indus Valley CivilisationDocumento3 páginasIndus Valley CivilisationAmarinder BalAinda não há avaliações

- PrOject On Indus CivilisatiOnDocumento17 páginasPrOject On Indus CivilisatiOnJoyakim DavisAinda não há avaliações

- Indus Valley CivilizationDocumento16 páginasIndus Valley Civilizationcarlosnestor100% (1)

- The Indus Valley Civilisation (Harappan Civilisation) : Dr. Hetalben Dhanabhai SindhavDocumento7 páginasThe Indus Valley Civilisation (Harappan Civilisation) : Dr. Hetalben Dhanabhai SindhavN SHAinda não há avaliações

- Cradle of Indian CultureDocumento8 páginasCradle of Indian CultureicereiAinda não há avaliações

- 2.1.1. Indus Valley CivilizationDocumento17 páginas2.1.1. Indus Valley Civilizationcontrax8Ainda não há avaliações

- Indus Valley CivilizationDocumento2 páginasIndus Valley CivilizationAbdul MajidAinda não há avaliações

- Indus Valley CivilizationDocumento24 páginasIndus Valley CivilizationMarcela Ruggeri0% (1)

- q2n39 PDFDocumento8 páginasq2n39 PDFitharajuAinda não há avaliações

- Harappan CivilizationDocumento66 páginasHarappan CivilizationJnanam33% (3)

- HarappaDocumento5 páginasHarappaayandasmtsAinda não há avaliações

- 1 - The Indus River Valley CivilizationDocumento4 páginas1 - The Indus River Valley CivilizationHira AzharAinda não há avaliações

- Indus Valley CivilizationDocumento6 páginasIndus Valley Civilizationkami9709100% (1)

- The Indus Valley CivilizationDocumento33 páginasThe Indus Valley CivilizationAbhishek Gandhi100% (7)

- What Is History-?: Paleolithic Period/EraDocumento8 páginasWhat Is History-?: Paleolithic Period/EraCecil ThompsonAinda não há avaliações

- Static GK Theory FinalDocumento387 páginasStatic GK Theory FinalRahul NkAinda não há avaliações

- History Book L03Documento18 páginasHistory Book L03ajawaniAinda não há avaliações

- SSH-302 Pakistan Studies: Early CulturesDocumento56 páginasSSH-302 Pakistan Studies: Early Cultureszain malikAinda não há avaliações

- Harappan CivilisationDocumento10 páginasHarappan Civilisationsohamjain100% (1)

- (Sir William Meyer Lectures) K. N. Dikshit - Prehistoric Civilization of The Indus Valley-Indus Publications (1988)Documento87 páginas(Sir William Meyer Lectures) K. N. Dikshit - Prehistoric Civilization of The Indus Valley-Indus Publications (1988)Avni ChauhanAinda não há avaliações

- Gujarat Administrative Services Prelims Full SyllabusDocumento9 páginasGujarat Administrative Services Prelims Full SyllabusAbhishek KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Ancient HistoryDocumento164 páginasAncient Historyrahuldewangan651Ainda não há avaliações

- Indus Valley CivilisationDocumento51 páginasIndus Valley Civilisationplast_adesh100% (1)

- Indus Valley CivilisationDocumento4 páginasIndus Valley CivilisationRohan PandhareAinda não há avaliações

- Histroy of Indus Valley Civilizaton 55Documento25 páginasHistroy of Indus Valley Civilizaton 55Wasil AliAinda não há avaliações

- Indus Valley Civilization Short Note PDFDocumento13 páginasIndus Valley Civilization Short Note PDFGautam krAinda não há avaliações

- Indus Valley CivilizationDocumento69 páginasIndus Valley Civilizationfeeamali1445Ainda não há avaliações

- A Dibur Rahman Human TiesDocumento12 páginasA Dibur Rahman Human Tiesindia cybercafeAinda não há avaliações

- Eli Souza - Breaking News TextDocumento1 páginaEli Souza - Breaking News TextEli SouzaAinda não há avaliações

- The Story of India: ExcerptsDocumento13 páginasThe Story of India: Excerptsjeevesh1980Ainda não há avaliações

- Indus Valley CivilisationDocumento49 páginasIndus Valley CivilisationAishwarya RajaputAinda não há avaliações

- Indus SOCIAL EthinicityDocumento13 páginasIndus SOCIAL EthinicityAli HaiderAinda não há avaliações

- The World Hunt: An Environmental History of the Commodification of AnimalsNo EverandThe World Hunt: An Environmental History of the Commodification of AnimalsNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (2)

- Bunyip of Berkeleys CreekDocumento4 páginasBunyip of Berkeleys CreekMitchell JohnsAinda não há avaliações

- Nathan: The Man Who Rebuked A KingDocumento4 páginasNathan: The Man Who Rebuked A KingMitchell JohnsAinda não há avaliações

- The Achaemenidian Persian ArmyDocumento3 páginasThe Achaemenidian Persian ArmyMitchell JohnsAinda não há avaliações

- Marlowe Society Dido OverviewDocumento54 páginasMarlowe Society Dido OverviewMitchell JohnsAinda não há avaliações

- Dreamtime Aboriginal Culture Fact SheetDocumento3 páginasDreamtime Aboriginal Culture Fact SheetMitchell JohnsAinda não há avaliações

- Norse Mythology Legend of Gods and HeroesDocumento399 páginasNorse Mythology Legend of Gods and HeroesEmisa Rista100% (2)

- ATO Advice For Non-LodgementDocumento1 páginaATO Advice For Non-LodgementMitchell JohnsAinda não há avaliações

- Example Only - WHS Manual - The - Community - Services - Safety - Pack - 4421Documento173 páginasExample Only - WHS Manual - The - Community - Services - Safety - Pack - 4421IshanSaneAinda não há avaliações

- Warhammer Invasion The Card GameDocumento24 páginasWarhammer Invasion The Card GameWilliam RoganAinda não há avaliações

- Arkham Horror Curse of The Dark PharaohDocumento2 páginasArkham Horror Curse of The Dark PharaohMitchell JohnsAinda não há avaliações

- Arkham Horror Innsmouth HorrorDocumento16 páginasArkham Horror Innsmouth HorrorMitchell JohnsAinda não há avaliações

- Arkham Horror Dunwich Horror Rules EnglishDocumento12 páginasArkham Horror Dunwich Horror Rules EnglishMitchell JohnsAinda não há avaliações

- Arkham Horror Kingsport Horror AHKH Rules Eng-1Documento16 páginasArkham Horror Kingsport Horror AHKH Rules Eng-1Mitchell JohnsAinda não há avaliações

- Hip Hop As Subculture PDFDocumento13 páginasHip Hop As Subculture PDFRoberto A. Mendieta VegaAinda não há avaliações

- T B G W: He Lack Oat of The OodsDocumento2 páginasT B G W: He Lack Oat of The OodsMitchell JohnsAinda não há avaliações

- Book of The Dead: in Early Science and PhilosophyDocumento1 páginaBook of The Dead: in Early Science and PhilosophyMitchell JohnsAinda não há avaliações

- Brochure - Digital Banking - New DelhiDocumento4 páginasBrochure - Digital Banking - New Delhiankitgarg13Ainda não há avaliações

- MINIMENTAL, Puntos de Corte ColombianosDocumento5 páginasMINIMENTAL, Puntos de Corte ColombianosCatalina GutiérrezAinda não há avaliações

- Database Management Systems Lab ManualDocumento40 páginasDatabase Management Systems Lab ManualBanumathi JayarajAinda não há avaliações

- Describing LearnersDocumento29 páginasDescribing LearnersSongül Kafa67% (3)

- Sample Midterm ExamDocumento6 páginasSample Midterm ExamRenel AluciljaAinda não há avaliações

- Re CrystallizationDocumento25 páginasRe CrystallizationMarol CerdaAinda não há avaliações

- Zero Power Factor Method or Potier MethodDocumento1 páginaZero Power Factor Method or Potier MethodMarkAlumbroTrangiaAinda não há avaliações

- Analog Electronic CircuitsDocumento2 páginasAnalog Electronic CircuitsFaisal Shahzad KhattakAinda não há avaliações

- Etta Calhoun v. InventHelp Et Al, Class Action Lawsuit Complaint, Eastern District of Pennsylvania (6/1/8)Documento44 páginasEtta Calhoun v. InventHelp Et Al, Class Action Lawsuit Complaint, Eastern District of Pennsylvania (6/1/8)Peter M. HeimlichAinda não há avaliações

- Approved Chemical ListDocumento2 páginasApproved Chemical ListSyed Mansur Alyahya100% (1)

- 576 1 1179 1 10 20181220Documento15 páginas576 1 1179 1 10 20181220Sana MuzaffarAinda não há avaliações

- Case Blue Ribbon Service Electrical Specifications Wiring Schematics Gss 1308 CDocumento22 páginasCase Blue Ribbon Service Electrical Specifications Wiring Schematics Gss 1308 Cjasoncastillo060901jtd100% (132)

- Trudy Scott Amino-AcidsDocumento35 páginasTrudy Scott Amino-AcidsPreeti100% (5)

- Unified Power Quality Conditioner (Upqc) With Pi and Hysteresis Controller For Power Quality Improvement in Distribution SystemsDocumento7 páginasUnified Power Quality Conditioner (Upqc) With Pi and Hysteresis Controller For Power Quality Improvement in Distribution SystemsKANNAN MANIAinda não há avaliações

- Final Presentation BANK OF BARODA 1Documento8 páginasFinal Presentation BANK OF BARODA 1Pooja GoyalAinda não há avaliações

- What Is Folate WPS OfficeDocumento4 páginasWhat Is Folate WPS OfficeMerly Grael LigligenAinda não há avaliações

- Scatchell Jr. V Village of Melrose Park Et Al.Documento48 páginasScatchell Jr. V Village of Melrose Park Et Al.Gianna ScatchellAinda não há avaliações

- VtDA - The Ashen Cults (Vampire Dark Ages) PDFDocumento94 páginasVtDA - The Ashen Cults (Vampire Dark Ages) PDFRafãoAraujo100% (1)

- 206f8JD-Tech MahindraDocumento9 páginas206f8JD-Tech MahindraHarshit AggarwalAinda não há avaliações

- Shielded Metal Arc Welding Summative TestDocumento4 páginasShielded Metal Arc Welding Summative TestFelix MilanAinda não há avaliações

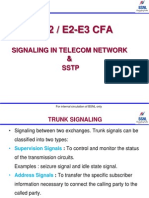

- Signalling in Telecom Network &SSTPDocumento39 páginasSignalling in Telecom Network &SSTPDilan TuderAinda não há avaliações

- Ideal Weight ChartDocumento4 páginasIdeal Weight ChartMarvin Osmar Estrada JuarezAinda não há avaliações

- Theater 10 Syllabus Printed PDFDocumento7 páginasTheater 10 Syllabus Printed PDFJim QuentinAinda não há avaliações

- 9m.2-L.5@i Have A Dream & Literary DevicesDocumento2 páginas9m.2-L.5@i Have A Dream & Literary DevicesMaria BuizonAinda não há avaliações

- OglalaDocumento6 páginasOglalaNandu RaviAinda não há avaliações

- "What Is A Concept Map?" by (Novak & Cañas, 2008)Documento4 páginas"What Is A Concept Map?" by (Novak & Cañas, 2008)WanieAinda não há avaliações

- Thesis FulltextDocumento281 páginasThesis FulltextEvgenia MakantasiAinda não há avaliações

- HW 2Documento2 páginasHW 2Dubu VayerAinda não há avaliações

- The New Definition and Classification of Seizures and EpilepsyDocumento16 páginasThe New Definition and Classification of Seizures and EpilepsynadiafyAinda não há avaliações

- Maths Lowersixth ExamsDocumento2 páginasMaths Lowersixth ExamsAlphonsius WongAinda não há avaliações