Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Articol Reprezentari Sociale

Enviado por

Eduard StoicaDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Articol Reprezentari Sociale

Enviado por

Eduard StoicaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

AGGRESSIVE BEHAVIOR Volume 20, pages 101-114 (1994)

Social Representations of Aggression in Children

John Archer and Sarah Parker

Department of Psychology, University of Central Lancashire, Preston, Lancashire, United Kingdom

Adult men and women endorse different sets of thoughts, beliefs and emotions ("social representations") about their aggression. Study 1 investigated whether this was also the case for children. A modified version of a questionnaire designed hy Campbell et al. [(1992) Aggressive Behavior 18:95-108] for adults was administered to 8-11 year olds to determine whether they viewed their own aggressive acts in terms of instrumental (male) or expressive (female) representations, as had been found for adults. This was found to he the case, but there were no age differences and no interaction of sex and age. The modified questionnaire showed similar internal consistency to the original, and the effect size for sex was similar to that found for adults. It was noted that the questionnaire is biased toward physical aggression and hence toward an activity compatible with the masculine role. In study 2, the questionnaire was reworded to refer to indirect aggression (which is more characteristic of girls) and presented to suhstantially the same sample. Again, girls showed higher expressive scores than boys, although the sex difference was diminished. This supported the view that there is a general sex difference in reactions to aggressive or hostile acts, independent of their form. However, analysis of individual questionnaire items showed that it was lack of emotional control and subsequent regrets about the act that most clearly distinguished the sexes. It is argued that these differences arise from more general gender role characteristics rather than being specific to aggression. 1994 WUey-Liss, Inc.

Key words: sex differences, social representations, physical aggression, indirect aggression, gender roles

INTRODUCTION

Based on earlier studies by herself and her colleagues, Campbell [1994] set out the hypothesis that men and women have different sets of attitudes toward and attributions

Received for publication August 24, 1993; accepted December 6,1993. Address reprint requests to Prof. JobnArcher, Department of Psycbology, University of Central Lancasbire, Preston, PRl 2HE, Lancasbire, United Kingdom.

1994 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

702

Archer and Parker

for, aggression and anger: men tend to be instrumental and women expressive. These differences were first derived from a form of discourse analysis, by coding conversations between small numbers of men and women concerning anger and aggression [Campbell and Muncer, 1987], and were labeled "social representations" following Moscovici [1984]. Subsequently, they were investigated through a 20-item forced-choice questionnaire, the EXPAGG [Campbell et al., 1992]. This involves 20 items, each containing a statement about aggression followed by two alternative responses, one which is instrumental and the other expressive. The responses describe feelings and thoughts during and after an aggressive act, its immediate cause, its social value, the form it takes, its aims, and its situational influences. Campbell et al. [1992] administered the EXPAGG to 105 psychology undergraduates and found it to be internally consistent. The overall responses, and 12 of the 20 individual items, showed signficant correlations with the respondent's sex. The overall bivariate correlation was 0.463. The researchers concluded that these results confirmed their earlier view derived from the analysis of men's and women's social talk, i.e., that the two sexes show different social representations of aggression, men viewing it in instrumental and women in expressive terms. Thesefindingshave since been replicated with another student sample [Campbell et al., 1993], and among soldiers and student nurses [Campbell and Muncer, 1994]. In the latter study, these two gender-typed occupations showed an even greater association with EXPAGG scores than did sex. The present paper describes two studies which extend this research. Thefirstinvestigates whether school-aged children also show these sex differences in attitudes and beliefs about aggresssion, and if so, whether they change with age during middle childhood. It also investigates the reliability of a revised EXPAGG for children, and its factor strucuture. The second study uses essentially the same sample of children to investigate whether the sex difference in social representations of aggression extends to indirect forms. Campbell et al. [1992] acknowledged that their questionnaire is biased toward physical aggression, which is more characteristic of males than females. Nevertheless, the theory of social representations which gave rise to the scale [Campbell, 1994] holds 1) that the two sexes conceptualize all forms of aggression and anger in different ways and 2) that these different representations are implicated in a causal way in the observed sex differences in aggressive actions. It is, however, possible that the current measure of social representations, the EXPAGG, by concentrating on physical aggression, may simply be capturing an activity which forms a functional part of the masculine role: in childhood, there is an emphasis on status and toughness, withfightingand athletic ability being highly valued [Archer, 1992; see also Lagerspetz et al., 1988]. For the feminine role, on the other hand, recourse to physical aggression has no central function: in childhood, there is more emphasis on close friendship and sharing secrets, hostility being expressed more by indirect verbal means, such as telling secrets, spreading gossip, and ignoring someone. It is therefore plausible to suggest that when physical aggression is used, it is seen as outside this value system and hence is viewed as dysfunctional, i.e., as an unfortunate lapse of control, rather than (as in the case of boys) a necessary means to attaining goals central to gender role aspirations. Recognizing the current limitations of their questionnaire, Campbell et al., [1992] suggested testing the applicability of the instrumental-expressive distinction to verbal

Aggressive Social Representations in Children

103

aggression, so as to dissociate it from the male-valued area of physical aggression. However, verbal aggression typically shows a sex difference in the same direction as physical aggression [e.g., Hyde, 1984,1986; Gladue, 199la,b]. Therefore, a better arena for testing the generality of the social representations theory would be to use indirect aggressionsuch as telling tales and not speaking to someonesince this is characteristic of girls' aggression [Lagerspetz et al., 1988; Bjorkqvist, 1994; Bjorkqvist et al., 1992a; Cairns et al., 1989; Fry, 1992]: as indicated above, it is more central to goals related to their gender role, with its emphasis on intimacy and close friendship. The second study involved a version of the EXPAGG with the same instrumental and expressive alternatives, but referring to items of indirect aggression (getting even) of the sort identified as more commonly used by girls. If such acts still evoke the instrumental alternative more often for males than for females, this would indicate the sort of generality Campbell has claimed for the social representations. If, however, the answers are reversed in line with the sex most closely associated with this form of aggression, it is likely that the answers are more closely linked with the ways in which aggression is expressed within the masculine and feminine roles. STUDY 1: SOCIAL REPRESENTATIONS OF AGGRESSION DURING CHILDHOOD Materials and Methods Participants. These were 206 primary school children, aged 8-11 years, from three classes in each of two primary schools located in Cheshire: 104 were boys (the numbers at the four ages were 22,36,40, and 6, respectively) and 102 were girls (the numbers at the four ages were 21,23,48, and 10, respectively). Questionnaire. This was a form of the questionnaire devised by Campbell et al., [1992] but modified for children. The questionnaire contained items relating to the causes, social value, form, aims, social facilitators, emotions, cognitions, and reputational aspects, connected with acts of aggression by the respondent. Each item was an incomplete statement about aggression, followed by two alternatives, one instrumental and the other expressive. The respondent is asked to tick the one with which he or she agrees. The overall instructions referred to "A few questions asking about how you feel towards anger and fighting." The 20 items are shown in Table I. Several words from the original questionnaire, such as admirable and obnoxious, were replaced by ones with simpler meanings, which had been understood by children of this age in a pilot investigation: an 8-year-old boy and a 10-year-old girl had been asked to explain the meanings of various items related to aggression which appeared on the original questionnaire. Incidentally, it could be argued that the EXPAGG questionnaire is more relevant to children than to adults since it concentrates on physical forms of aggression, which are more common among children than among adults. The modified questionnaire contained 20 items (as did the original) which were similar in format to those used by Campbell et al. [1992]. The questionnaire was scored by assigning 0 to the instrumental alternative and 1 to the expressive one. Procedure. The questionnaires were administered by the class teachers who explained that they concerned how the children felt about anger and fighting, that they should be answered truthfully, and that they were anonymous. The children were seated sepa-

104

Archer and Parker

TABLE 1. Twenty-Item Modified EXPAGG Questionnaire, Showing the Expressive (E) and Instrumental (I) Alternatives for Each Item* 1. I believe my anger comes from (E) losing my self-control (I) being pushed too far by people I don't like [27 vs. 44; x^ = 6.73; P < 0.01] 2. Someone who never behaves angrily (E) has great patience (I) gets trodden on by people [68vs.61;x' = 0.69;NS] 3. In a heated argument, I am most afraid of (E) saying something terrible that I can never take back (I) being out-argued by the other person [56 vs 69; x^ = 4.11;/'< 0.05] 4. In an argument, I would feel more annoyed with myself if (E) I hit another person (I) I cried [54 vs. 68; x^ = 4.64; P < 0.05] 5. If someone challenged me to a fight in public (E) I'd feel proud if I backed away (I) I'd feel cowardly if I backed away [49vs.61;x' = 3.33;NS] 6. When I get to the point of fighting the thing I am most aware of is (E) how upset and shaky I feel (I) how I am really going to teach the other person a lesson [42 vs 63; x^ = 9.42; P < 0.005] 7. I am more likely to hit out (E) when I am alone with the person who is annoying me (I) when another person shows me up in public [54 vs 59; x' = 0.73; NS] 8. During a fight (E) I feel out of control (I) I feel as if I know exactly what I am doing [67 vs 85; x' = 9.52; P < 0.005] 9. The worst thing about fighting is (E) it hurts another person (I) before long the other person gets right back to behaving badly again [71 vs 83; x^ = 4.69; P < 0.05] 10. If no one is there to see an argument that I'm involved in (E) I'm more likely to hit out (I) I'm less likely to hit out [66 vs 68; x' = 0.23; NS] 11. When an argument really heats up, I am most likely to (E)cry (I) lash out at someone [23 vs 62; x' = 26.27; P < 0.001] 12. I am most likely to get into a fight when (E) I've been worried and some little thing pushes me over the edge (I) I feel that another person is trying to make me look like a jerk [28 vs. 44; x' = 5.96 P < 0.02] 13. The best thing about being really cross is (E) it gets my anger out of my system (I) it makes the other person do what I want them to [63vs.70;x^=1.46;NS] 14. If I hit someone and hurt them, I feel (E) guilty

Aggressive Social Representations in Children TABLE I. (continued) (I) as if they were asking for it [65 vs. 82; x' = 8.07; P < 0.005] 15. After I lash out at another person, I would like them to (E) realize how upset they made me and how unhappy I was (I) make sure they never annoy me again [46 vs 74; x' = 16.98; P < 0.001] 16. After a fight, I tend to tell (E) no one except maybe a close friend (I) a lot of friends [77 vs. 89; x' = 5.78; P < 0.02] 17. The day after a fight (E) I can't remember exactly what happened (I) I remember every move I made [38 vs. 48; x' = 2.34; NS] 18. After a fight I feel (E) drained and guilty (I) happy or depressed depending on whether I won or lost [65vs. 71;x'=116;NS] 19. When I tell my friends about a fight I was in, I tend to (E) spend a lot of time excusing what I did (I) make it sound more exciting than it really was [45 vs. 60; x' = 4.99; P < 0.05] 20. I believe that fighting is (E) always wrong (I) necessary to get through to some people [69 vs. 84; x' = 6.91; P < 0.01]

105

*On the line below are the numbers of boys (N = 104) and girls (N = 102) who endorsed the E alternative, together with the associated x^ and P values.

rately, so as to prevent conferring, talking, and copying. The teacher and the second author were available to answer queries and help any children who had difficulties filling in the questionnaire. Detailed and precise instructions were presented on the front page and were read out loud and explained by the form teacher. Each child was also asked to fill in his/her age and sex.

Results

Although based on nominal data, Cronbach's alpha was calculated for the scale so as to compare it with the value reported by Campbell et al. [1992]. The present figure was 0.70, similar to the 0.72 reported in their study. Item 10 showed a zero item-to-whole correlation, and if removed the scale would show an alpha of 0.72. This item concerned being more or less likely to hit out if there was no one there: it may have confounded expressiveness and willingness to use physical violencethe first would be a female characteristic, but the second a male one. Factor analysis (SPSS, varimax rotation) was carried out on the scale, again for the purpose of comparison with previous results. It did not reveal a general instrumentalexpressive factor with significant loadings on most of the items, as Campbell et al. [1992] had found. Instead, there was one main factor, accounting for 17.7% of the variance, and a number of lesser factors accounting for 5-7% each. The Scree method [Cureton and D'Agostino, 1983] indicated that there was only one important factor: it had high loadings (over 0.4) for items 6 (0.56), 8 (0.52), 11 (0.72), 12(0.45), 14(0.48),

706

Archer and Parker

TABLE II. Means and SDs (in Parentheses) for EXPAGG Scores of Boys and Girls, and Associated Effect Sizes, Across the Four Age Groups and Overall Age (years) 11 Overall 10 9 8 Boys Mean SD N Girls Mean SD N Effect size (d) 10.45 (2.52) 22 12.10 (3.16) 21 0.58 10.44 (3.72) 36 14.61 (3.00) 23 1.24 10.15 (3.53) 40 13.06 (3.77) 48 0.80 9.66 (2.94) 6 14.4 (2.72) 10 1.67 10.29 (3.34) 104 13.42 (3.49) 102 0.92

15 (0.40), 18 (0.61), and 20 (0.61). With the exception of the last of these, they can be viewed as measuring lack of control in, and feelings of regret or guilt after, an aggressive situation. We should, however, note that there has been considerable controversy over the validity of factor analysis applied to nominal data [Comrey, 1973; Kim and Mueller, 1978; Richardson, 1989]. A total score was calculated for each respondent (a higher score indicating the expressive alternative). Table II shows the means and standard deviations (SDs) for the boys and girls for the four different ages, and overall. A 2 x 4 analysis of variance (ANOVA) (sex x age) was carried out on the total scores. There was a significant main effect for sex [F( 1,204) = 32.54, P < 0.001 ]. There was no significant effect for age or the age x sex interaction, although the effect sizes are clearly variable across the age categories (Table II). The overall effect size is 0.92, which gives a bivariate correlation of 0.417 [Cohen, 1977, table 2.2.1]. This is slightly smaller than the value of 0.463 found for adults by Campbell et al. [1992]. Campbell et al. [1992] found considerable item-by-item variability in the magnitude of sex differences on the original EXPAGG. We therefore calculated the numbers of boys and girls endorsing the expressive alternative for each item. The results are shown in Table I, together with the associated chi-square and P values. On 19 items, more girls than boys endorsed the expressive alternative and for 13 of these the associated chisquare showed a significant difference {P < 0.05). This compares with 12 items which reached the 0.1 level in the smaller (by a half) sample used by Campbell et al. [1992]. Using these criteria, there were eight items showing significant differences in both studies (4,5,6,11,12,14,15, and 20), six only in the present study (1,3,8,9,16, and 19), three only in the previous one (7, 10, and 13), and three in neither (2, 17, and 18). Items concerning the importance of being shown up in public (5,7, and 10) showed small if anysex differences in the present study, but large ones in the adult sample used by Campbell et al. [1992]. Items loading heavily on factor 1 (see above) tended to be those showing the largest differences between the sexes. In 7/8 cases the chi-square was over 5.0, the exception being item 18; of the 12 items not showing high loadings on factor 1, only two showed a chi-square of over 5.0 (items 1 and 16). As indicated above, factor 1 consisted of items indicating lack of emotional control and regret after the event.

Aggressive Social Representations in Children Discussion

107

Campbell et al. [1992] found that there were sex differences in the social representations of aggression among young adults, males viewing it in more instrumental terms and females in more expressive terms. We found that this was also the case for schoolchildren from 8 to 11 years of age. There were no age differences in these social representations and no interaction of the sex difference with age. We should note that this was not an absolute sex difference, the effect size being around 0.92 for the whole sample, slightly smaller than that found by Campbell et al. [1992] for young adults. It is of a similar magnitude to some of the sex differences in nonverbal behavior [Hall, 1984], but rather larger than sex differences in aggressiveness found in meta-analysis of trait and laboratory measures [Eagly and Steffen, 1986; Hyde, 1986]. It is about the same size as the sex differences in physical aggression, based on self-reports, found by Gladue [1991a,b] for young adults, but smaller than that found for physical aggression among 10-12-year-old children [e.g.. Archer et al., 1988; Lagerspetz et al., 1988]. Although Campbell et al. [1992] applied their findings to explaining why certain variables affect the magnitude of sex differences in aggression, it should be emphasized that the sex differences found by them, and in the present study, were not differences in observed or reported acts of aggression. They were social representations or schemata evoked by cue lines indicating that a hypothetical situation involving the respondent in an aggressive interaction, or more accurately one in which physical aggression was likely. Campbell et al. [1992] found a general factor on which all 16 items showing reasonable item-to-whole correlations loaded, and significant sex differences on 12 items including one not on this factor. In the present study, the items showing the largest sex differences were nearly all located on the main factor, which in this case was more specific: it consisted of those items indicating lack of control in an aggressive situation, together with regret and guilt about it later. A number of items, such as telling friends about it afterward, showed significant (although generally smaller) sex differences, but were not part of the main factor. It was noteworthy that among this younger sample, items indicating the impact of the dispute or fight being in public (5, 6, and 10) showed much smaller sex differences than was the case for the sample of young adults studied by Campbell et al. [1992]. This perhaps indicates that not losing face in a dispute is of lesser importance for prepubertal than for teenaged and adult males [see Campbell, 1986; Daly and Wilson, 1988; Archer, 1994].

STUDY 2: SOCIAL REPRESENTATIONS OF INDIRECT AGGRESSION DURING CHILDHOOD

As indicated in the Introduction, the EXPAGG does have the limitation of being biased toward physical aggression. In order to test its generality, a further study was carried out using the sorts of indirect forms of aggression that have been identified as more characteristic of girls [e.g., Lagerspetz et al., 1988; Bjorkqvist et al., 1992a]. The EXPAGG was recast in these terms by changing the emphasis of the statements from "anger and fighting" to "getting even with someone," and indicating where possible that the means were indirect ones such as telling untruths behind the person's back or deliberately ignoring them [Lagerspetz et al., 1988]. In this way, we kept as close as possible to the definition of indirect aggression given by Bjorkqvist et al. [1992b], as

108

Archer and Parker

TABLE m . Twenty Item INDIRECT AGGRESSION EXPAGG Questionnaire, Showing ttie Expressive (E) and Instrumental (I) Alternatives for Each Item* 1. Wben I tell an untrutb bebind someone's back it comes from (E) losing my self-control (I) being pusbed too feir by tbe person concerned [35 vs. 22; x'= 3.26; NS] 2. Someone wbo never tries to get even (E) has great forgiveness (I) gets trodden on by people [43vs. 38;x^=0.23;NS] 3. In getting my own back, I am most afraid of (E) saying sometbing terrible tbat I can never take back (I) baving someone do tbe same to me [66vs66; x'=0.22;NS] 4. Wben I fall out with sotneone, I would feel more annoyed witb mysetf if (E) I said something to burt tbem (I) I cried [66vs67;x'=0.04;NS] 5. If someone said sometbing nasty about me bebind my back (E) I'd feel proud if I did notbing about it (I) I'd feel cowardly if I did notbing about it [41 vs. 33;x'=0.08;NS] 6. When I get to the point of telling untruths about someone to get at tbem, I atn most aware of (E) bow upset and sbaky I feel (I) bow I am really going to teach tbe otber person a lesson [47 vs. 69; x'= 11.73; P < 0.001] 7. I am more likely to want to get my own back later (E) wben I am alone with the person who is annoying me (I) when another person shows me up in public [45vs. 36;x'=1.01;NS] 8. Wben I bave a falling out with someone (E) I feel out of control (I) I feel as if I know exactly what I am doing [67vs. 78; x'= 4.60;/'< 0.05] 9. The worst thing about getting even witb someone is (E) it hurts the other person (I) before long the other person gets right back to behaving badly again [50vs.55;x'=106;NS] 10. If no one knows what I'm doing (E) I'm more likely to tell an untruth bebind someone's back (I) I'm less likely to tell an untrutb bebind someone's back [56vs. 53;x'=0.00;NS] 11. When I fall out with someone, I am most likely to (E)cry (I) want to get back at them [21 vs 52; x'= 22.45; P < O.OOt] 12. I am most likely to want to get even with someone when (E) I've been worried and some little thing pushes me over tbe edge (I) I feel that another person is trying to make me look like a jerk [38vs.51;x^=4.45;/'<0.05] 13. Tbe best tbing about getting even with someone is (E) it gets my anger out of my system (I) it makes the otber person do wbat I want them to [85vs. 88;x^=l-62;NS] 14. If I say something nasty bebind someone's back and hurt tbem I feel (E) guilty

Aggressive Social Representations in Children

TABLE III, (continued) (I) as if tbey were asking for it [55vs. 80;x'=16.36;/'<0.01] 15. After I get even witb anotber person, I would like tbem to (E) realize bow upset they made me and how unhappy I was (I) make sure they never annoy me again [42 vs. 82; x^= 36.02; P < 0.001] 16. After getting even with someone, I tend to tell (E) no one except maybe a close friend (I) lots of friends [75vs. 86; x'= 5.76;/'< 0.02] 17. The day after getting my own back on someone (E) I can't remember exactly what happened (I) I remember every move I made [42vs.40;x'=0;NS] 18. After trying to get my own back I feel (E) drained and guilty (I) bappy or depressed depending on whether it worked [55vs. 64;x^=2.69;NS] 19. When I tell my friends about how I got even with someone, I try to (E) spend a lot of time excusing what I did (I) make it sound more exciting than it really was [39vs. 56;x'=7.1;/'<0.01] 20. I believe that ignoring someone who has annoyed you is (E) always wrong (I) necessary to get through to some people [40vs.40;x'=0.07;NS]

109

On the line tielow are the numbers of boys (N = 108) and girls (N = 103) wbo endorsed the E altemative, together with the associated x^ and P values.

harm delivered circuitously rather than face-to-face. In doing so, the intention was first to remove the possible male bias associated with anger and fighting and second to introduce a form of hostile responding with which girls could identify.

Materials and Methods

Participants. These were 211 primary school children, aged 8-11 years, from the same two primary schools as in the first study: 193 were the same respondents as in the first case. The study was carried out 6 months later, and an attempt was made to use the same sample, but owing to absences this was only 91% successful. There were 108 boys (the numbers at the four ages were 7, 31, 42, and 28, respectively) and 103 girls (the numbers at the four ages were 5, 32, 27, and 39, respectively). Questionnaire. As indicated above, the 20 items were concerned with getting even or getting one's own back rather than physical aggression and anger. As in the original questionnaire devised by Campbell et al. [1992], each item was an incomplete statement about, in this case, getting even, followed by two alternatives, one instrumental and the other expressive. The respondent was asked to tick the one with which he or she agreed. The 20 items are shown in Table III. As in the first study, several words from the original questionnaire were replaced by ones with simpler meanings, which had been understood by children of this age in a pilot investigation. The questionnaire was scored by assigning 0 to the instrumental altemative and 1 to the expressive one.

110

Archer and Parker

Procedure. The questiotinaires were administered by the class teachers who explained that they concerned how the children felt about getting even with someone by, e.g., ignoring them or telling untruths behind their backs. The children were again seated separately, so as to prevent conferring, talking, and copying. The teacher and the second author were again available to answer queries and to help any children who had difficulties filling in the questionnaires. Precise instructions were given on the front page and were again read out loud and explained by the form teacher. Each child was also asked to fill in his/her age and sex. Results Cronbach's alpha was calculated, while recognizing its limitations for a nominal scale, so as to compare it with the value from the first study and that reported by Campbell et al. [1992]. The present figure was 0.64, rather lower than the previous two. Similarly, factor analysis (SPSS, varimax rotation) was carried out for comparative purposes. Again, it did not reveal a general instrumental-expressive factor with significant loadings on most of the items, as Campbell et al. [1992] had found. As in the first study, the Scree method [Cureton and D'Agostino, 1983] revealed one main factor, this time accounting for 15.4% of the variance, and a number of lesser factors accounting for 5-8% each. The main factor had high loadings for items 6 (0.68), 11 (0.60), 14 (0.67), 15 (0.68), 18 (0.57), and 19 (0.47), and lesser ones for items 8 (0.34) and 9 (0.35). With one exception, these are the same items that loaded on factor 1 in the first study, and they again indicate lack of control in, and regret about, aggressive actions. A total scale score was calculated for each respondent (a higher score indicating the expressive alternative). Table IV shows the means and SDs for the boys and girls for the four different ages, and overall. A 2 x 4 ANOVA (sex x age) was carried out on the total scores. There was a significant main effect for sex [F(l,203df) = 3.9l;P = 0.0495]. There was no significant effect for age or the age x sex interaction, although the effect sizes were clearly variable across the age categories (Table IV). The overall effect size was 0.44, which gave a bivariate correlation of 0.214 [Cohen, 1977, table 2.2.1].This is considerably smaller than the values found in study 1 and for adults by Campbell et al. [1992]. As in the first study, we carried out an item-by-item analysis of the numbers endorsing the expressive alternative for each item. The results are included in Table III. On 16

TABLE IV. Means and SDs (in Parentheses) for INDIRECT AGGRESSION EXPAGG Scores of Boys and Girls, and Associaied Effect Sizes, Across the Four Age Groups and Overall Age (years) 11 Overall 10 9 8 Boys Mean SD N Girls Mean SD N Effect size (d) 10.14 (2,79) 7 10.4 (2.30) 5 0.10 8.81 (2.81) 31 11.03 (3.37) 32 0,72 9.43 (3.69) 42 10.89 (3.57) 27 0.40 9.82 (4.15) 28 10.82 (3.19) 39 0.27 9,40 (3.52) 108 10.88 (3.28) 103 0.44

Aggressive Social Representations in Children

Ul

items, more girls than boys endorsed the expressive altemative, and 8 of these the associated chi-square indicated a significant difference at the 0.05 level. Seven of these eight items coincide with those loading on factor 1 (see above), indicating a lack of emotional control and guilty feelings about getting even. There was no indication that items which mentioned a specific form of indirect aggression, such as telling untruths about someone, were more or less likely to produce a sex difference. Discussion The results of this study showed that altering the questionnaire items to refer to indir^ct forms of aggressiongetting evendid not affect the direction of the instrumentar-expressive response. Girls still scored significantly higher than boys in the expressive direction, but the P value only just reached the 5% level. The effect size was about a half of what it was in the first study and in Campbell's research with adults. In both of these cases, the questionnaire items referred mainly to physical aggression. We can conclude, therefore, that altering the questionnaire statements to involve indirect aggression still evoked expressive responses more frequently in girls than boys, but to a lesser extent. Comparing the scores in the two studies indicates an overall reduction in the girls' endorsement of the expressive altemative, i.e., an increase in their instrumental choices, but not to the extent predicted by the gender role hypothesis outlined earlier. In the first study, the effect size found for the sex difference in the questionnaire scores was comparable with that reported in studies where physical aggression had been measured directly. However, with the INDIRECT AGGRESSION EXPAGG, the overall effect size (d) was considerably lower than, and in the opposite direction to, those reported for comparable items of indirect aggression. Thus d values calculated from table I of Lagerspetz et al. [1988] are 0.98 for "tells untruth behind back" and 1.47 for "acts as if doesn't know." These figures, which are in the direction of higher scores by girls, contrast with a value of 0.44 in the reverse direction in our second study. We therefore have a complete dissociation between the sex difference in the perceived frequency of this type of aggression and the reactions of the two sexes to having committed an act of indirect aggression. In this case, Campbell's suggestion that the different social representations are implicated in a causal way in the observed sex differences in aggressive actions could not apply. Instead, this study provided evidence for a dissociation between 1) the sex difference associated with the type of aggression or hostility portrayed in the lead-in statement and 2) the social representations associated with having committed this type of aggression. The second of these showed consistently that girls were more expressive than boys. Analysis of individual items indicated that the sex difference was largely confined to those items loading on the main factor, indicating loss of emotional control and guilt about the hostile act later. This was consistent with the finding from the first study, where the type of hostile or aggressive act had been very different. A further issue concems the measurement of indirect aggression. Lagerspetz et al. [1988] used a peer nomination method, reasoning that since indirect aggression is a disguised form, it may not be as amenable to investigation by self-reports as is direct aggression. In support of this view, they found low correlations (r = 0.23/0.24) between self and peer ratings of indirect aggression for both boys and girls. In contrast, boys but not girls showed much higher correlations (0.63) between the two types of rating for

772

Archer and Parker

direct aggression. Nevertheless, this should not affect the questionnaire method used in the present study, because it concerned reactions to acts of indirect aggression that had already been carried out and acknowledged. Not only are these reactions apparently independent of the sex-typed nature of the aggressive cues used (see above), but in addition they do not rely on the respondent having to disclose his or her own acts of indirect aggression. GENERAL DISCUSSION The present studies extend previous findings of a sex difference in schemata concerned with having committed an aggressive act, showing first that they apply to children aged 8-11 years of age as well as to young adults and second that they are still found when the subject matter ofthe statements concerns getting even by indirect means. The results also indicate that for both these very different types of aggressive or hostile acts, the sex difference centers around girls more commonly expressing feelings of having lost emotional control and feeling guilty and regretful after the event; boys are more likely to indicate that they are in control and to justify their actions in terms ofthe target person deserving the hostile or aggressive act. The typical girl's response is, of course, likely to be associated with more negative feelings and the typical boy's response with positive ones. One does not have to be a behaviorist to expect the first to be associated with a lesser likelihood of such acts occurring in the future and the second to be associated with a greater likelihood. For physical aggression, this expectation would be consistent with the argument [Campbell, 1994] that social representations play a causal role in maintaining aggression. But it raises problems in the case of indirect aggression. Why should the more negative feelings aroused in girls by having committed this form of aggression be associated with higher reported levels of the aggression itself? The answer probably lies in the disguised nature of indirect aggression. As indicated earlier, information about its frequency is based on peer ratings rather than self-reports (which show low correlations with the peer ratings). Therefore, when children show indirect aggression, they do not necessarily admit or recognize to themselves that they have done so. Presenting them with overt statements asking what they would feel if they had carried out an act of indirect aggression does not evoke greater identification with the situation in girls than in boys. It is therefore predicted that girls will tend to disguise their acts of indirect aggression and only to respond with the feelings identified in study 2 when they have been confronted with the intentional nature of such an act. The identification of emotional control and feelings of guilt as central to girls' feelings about their own aggression and hostility is consistent with findings from adults which indicate that women show greater anxiety about aggressive feelings than men do and that they tend to show more empathy with the victims [Frodi et al., 1977; Eagly and Steffen, 1986]. It is also consistent with the emphasis on avoidance of femininity, toughness, and self-confidence as important components of masculinity [David and Brannon, 1976; Thompson and Pleck, 1986]. Looked at from this perspective, the EXPAGG is picking up major differences between the sexes related to gender role characteristics. Although situations involving aggression provide an important context in which these differences manifest themselves, they may not be restricted to aggression. Future re-

Aggressive Social Representations in Children

113

search could address this issue and the possible links between "social representations" and the different reproductive strategies ofthe two sexes [Daly and Wilson, 1988,1994].

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to Anne Campbell and Paul Pollard for discussion of this research and to the University of Central Lancashire for providing financial support.

REFERENCES

Archer J (1992): Childhood gender roles: Social context and organisation. In McGurk H (ed): "Childhood Social Development: Contemporary Perspectives." Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp 31-61. Archer J (1994): Violence between men. InArcher J (ed): "Male Violence." New York: Routledge, pp 121-139. Archer J, Pearson NA, Westeman KE (1988): Aggressive behaviour of children aged 6-11: Gender differences and their magnitude. British Joumal of Social Psychology 27:371-384. Bjorkqvist K (1994): Sex differences in indirect aggression: A review of recent research. Sex Roles (in press). Bjorkqvist K, Lagerspetz KMJ, Kaukianen A (1992a): Do girls manipulate and boys fight? Developmental trends in regard to direct and indirect aggression. Aggressive Behavior 18:117-127. Bjorkqvist K, Osterman K, Kaukianen A (1992b): The development of direct and indirect aggressive strategies in males and females. In Bjorkqvist K, Niemela P (eds): "Of Mice and Women: Aspects of Female Aggression." San Diego: Academic Press, pp 51-64. Caims RB, Caims BD, Neckerman HJ, Ferguson LL, Gari^py J-L (1989): Growth and aggression. I. Childhood to early adolescence. Developmental Psychology 25:320-330. Campbell A (1986): The streets and violence. In Campbell A, Gibbs JJ (eds): "Violent Transactions: The Limits of Personality." Oxford: Blackwell.pp 115-132. Campbell A (1994): Men and the meaning of violence. In Archer J (ed): "Male Violence." New York: Routledge, pp 332-351. Campbell A, Muncer S (1987): Models of anger and aggression in the social talk of women and men. Journal of the Theory for Social Behavior 17:489-511. Campbell A, Muncer S (1994): Sex differences in aggression: Social representations and social roles. British Joumal of Social Psychology (in press). Campbell A, Muncer S, Coyle E (1992): Social representations of aggression as an explanation of gender differences: A preliminary study. Aggressive Behavior 18:95-108. Campbell A, Muncer S, Gorman B (1993): Gender and social representations of aggression: A communal-agentic analysis. Aggressive Behavior 19:125-135. Cohen J (1977): "Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences." New York: Academic Press. Comrey AL(1973):"AFirst Course inFactor Analysis." New York: Academic Press. Cureton EE, Agostino RB (1983): "Factor Analysis: An Applied Approach." Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Daly M, Wilson M (1988): "Homicide." New York: Aldine de Gruyter. Daly M, Wilson M (1994): Evolutionary psychology of male violence. In Archer J (ed): "Male Violence." New York: Routledge, pp 253-288. David DS, Brannon R (1976): The male sex role: Our culture's blueprint of manhood, and what it's done for us lately. In David DS, Brannon R (ed): "The Forty-Nine Per Cent Majority: The Male Sex Role." Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Eagly AH, Steffen VJ (1986): Gender and aggressive behavior: A meta-analytic review of the social psychological literature. Psychological Bulletin 100:309-330. Froti A, Macaulay G,Thome PR (1977): Are women always less aggressive than men? A review of the experimental literature. Psychological Bulletin 84:634-660. Fry D (1992): Female aggression among the Zapotec of Oaxaca, Mexico. In Bjorkqvist K, Niemela P (eds): "Of Mice and Women: Aspects of Female Aggression," San Diego: Academic Press, pp 187-199. Gladue BA (1991a): Qualitative and quantitative sex differences in self-reported aggressive behavioral characteristics. Psychological Reports 68: 675-684. Gladue BA (1991 b): Aggressive behavioral characteristics, hormones, and sexual orientation

114

Archer and Parker

in men and women. Aggressive Behavior Is indirect aggression typical of females? Gen17:313-326. der differences in aggressiveness in 11- to 12Hall JA (1984): "Non-Verbal Sex Differences." year-old children. Aggressive Behavior Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 14:403-414. Hyde JS (1984): How large are gender differences Moscovici S (1984): The phenomenon of social repin aggression? A developmental meta-analysis. resentations. In Farr R, Moscovici S (eds): "SoDevelopmental Psychology 20:722-736. cial Representations." Cambridge: Cambridge Hyde JS (1986): Gender differences in aggression. In University Press. Hyde JS, Linn MC (eds): "The Psychology of Richardson JTE (1989): Student learning and the Gender: Advances Through Meta-Analysis,"Balmenstrual cycle: Premenstrual symptoms and aptimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp 51-66. proaches to study. Educational Psychology Kim J-0, Mueller CW (1978): "Factor Analysis: 9:215-238. Statistical Methods and Practical Issues." Thompson EH, Pleck JH (1986): The structure of Beverly Hills: Sage, male role norms. American Behavioral Scientist Lagerspetz KMJ, Bjorkqvist K, Peltonen T (1988): 29:531-543.

Você também pode gostar

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5795)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Juvenile Crime Is A Cry For HelpDocumento3 páginasJuvenile Crime Is A Cry For HelpDesiree OliverosAinda não há avaliações

- Research - Topic #1Documento5 páginasResearch - Topic #1yayamiamomAinda não há avaliações

- The Moderation Analysis of Coping Strategies in The Relationship Between Anxiety and Aggression Among Security PersonnelDocumento10 páginasThe Moderation Analysis of Coping Strategies in The Relationship Between Anxiety and Aggression Among Security PersonnelJournal of Interdisciplinary PerspectivesAinda não há avaliações

- CH 1 Introduction To NegotiationDocumento33 páginasCH 1 Introduction To NegotiationNickKyAinda não há avaliações

- National Geographic USADocumento135 páginasNational Geographic USAThe ExtraKrumbs100% (2)

- Usadigg Tech What Are The Consequences of The Early Weaning of The KittenDocumento5 páginasUsadigg Tech What Are The Consequences of The Early Weaning of The KittenHICHAM casaAinda não há avaliações

- Module Two: Defining Gender-Based Violence (GBV)Documento27 páginasModule Two: Defining Gender-Based Violence (GBV)MhiahLine Tolentino100% (2)

- People vs. Umali (Digest)Documento1 páginaPeople vs. Umali (Digest)Jam Castillo100% (2)

- Review of Related Literature and StudiesDocumento15 páginasReview of Related Literature and StudiesIan G DizonAinda não há avaliações

- Essay On Ways of Preventing Bullying in SchoolsDocumento3 páginasEssay On Ways of Preventing Bullying in SchoolsClement KipyegonAinda não há avaliações

- ANG, Alicia Abby Ann E. Crim 1-B Module 3 Assignment: As A ResultDocumento7 páginasANG, Alicia Abby Ann E. Crim 1-B Module 3 Assignment: As A ResultAlicia Abby Ann AngAinda não há avaliações

- BullyingDocumento15 páginasBullyingapi-249799367Ainda não há avaliações

- Peoria County Jail Booking Sheet For July 23 2016Documento6 páginasPeoria County Jail Booking Sheet For July 23 2016Journal Star police documentsAinda não há avaliações

- AGGRESSIONDocumento28 páginasAGGRESSIONMichelle Therese100% (1)

- Moot Court On Memorial in Behalf of PetitionerDocumento18 páginasMoot Court On Memorial in Behalf of PetitionerRukaiya ParweenAinda não há avaliações

- Legal ResearchDocumento6 páginasLegal Researchfestus12Ainda não há avaliações

- Cultural ViolenceDocumento16 páginasCultural ViolenceGrupo Chaski / Stefan Kaspar100% (3)

- CRIM 2 REPORT-Secondary PreventionDocumento2 páginasCRIM 2 REPORT-Secondary PreventioncessyAinda não há avaliações

- University of Lucknow: Law Relating To Women & Children Topic: Domestic Violence Against WomenDocumento13 páginasUniversity of Lucknow: Law Relating To Women & Children Topic: Domestic Violence Against WomensuneelAinda não há avaliações

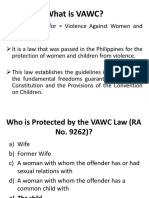

- Simplified VAWCDocumento13 páginasSimplified VAWCAnonymous oNB5QA0Ainda não há avaliações

- Bullying, Stalking, Extortion, Gang and Youth Violence, and Illegal Fraternity-Related ViolenceDocumento7 páginasBullying, Stalking, Extortion, Gang and Youth Violence, and Illegal Fraternity-Related ViolenceApple NapaAinda não há avaliações

- CBSE Class 12 Psychology - Psychology and LifeDocumento3 páginasCBSE Class 12 Psychology - Psychology and Lifeishwar singhAinda não há avaliações

- Ra 9262Documento3 páginasRa 9262Edaj ResyelAinda não há avaliações

- Child Abuse and MaltreatmentDocumento4 páginasChild Abuse and MaltreatmentScholah NgeiAinda não há avaliações

- Validation of A Selection Protocol of Dogs Involved in Animal-Assisted InterventionDocumento8 páginasValidation of A Selection Protocol of Dogs Involved in Animal-Assisted InterventionJosé Alberto León HernándezAinda não há avaliações

- Domestic Violence in IndiaDocumento8 páginasDomestic Violence in IndiairnaqshAinda não há avaliações

- 1.what Is Cyberbullying?: Depression AnxietyDocumento3 páginas1.what Is Cyberbullying?: Depression AnxietyNguyễn Thùy LinhAinda não há avaliações

- Behavioral Crisis Prevention and Intervention: The Dynamics of Non-Violent CareDocumento58 páginasBehavioral Crisis Prevention and Intervention: The Dynamics of Non-Violent Carelundholm4728Ainda não há avaliações

- Campus Sexual Violence - Statistics - RAINNDocumento6 páginasCampus Sexual Violence - Statistics - RAINNJulisa FernandezAinda não há avaliações

- How Video Games Affect HealthDocumento28 páginasHow Video Games Affect HealthPaida HeartAinda não há avaliações