Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

US Supreme Court Rules RICO Applies to Both Legitimate and Illegitimate Enterprises

Enviado por

Marina ReadDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

US Supreme Court Rules RICO Applies to Both Legitimate and Illegitimate Enterprises

Enviado por

Marina ReadDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

MP3 in itunes folder of the hearing: United States vs Turkette -----------------------------------------------------------------------U.S. Supreme Court UNITED STATES v.

TURKETTE, 452 U.S. 576 (1981) 452 U.S. 576 UNITED STATES v. TURKETTE. CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIRST CIRCUIT. No. 80-808. Argued April 27, 1981. Decided June 17, 1981. Chapter 96 of Title 18 of the United States Code, entitled Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO), was added to Title 18 by the Organized Crime Control Act of 1970. Title 18 U.S.C. 1962 (c), which is part of RICO, makes it unlawful "for any person employed by or associated with any enterprise engaged in, or the activities of which affect, interstate or foreign commerce, to conduct or participate, directly or indirectly, in the conduct of such enterprise's affairs through a pattern of racketeering activity or collection of unlawful debt." The term "enterprise" is defined in 18 U.S.C. 1961 (4) as including "any individual, partnership, corporation, association, or other legal entity, and any union or group of individuals associated in fact although not a legal entity." An indictment charged respondent and others with, inter alia, a conspiracy to violate 1962 (c). The indictment described the enterprise in question as a group of individuals associated in fact for the purpose of engaging in certain specified criminal activities. Respondent was convicted in Federal District Court, but the Court of Appeals reversed on the ground that RICO was intended solely to protect legitimate business enterprises from infiltration by racketeers and does not make it criminal to participate in an association which performs only illegal acts and has not infiltrated or attempted to infiltrate a legitimate enterprise. Held: The term "enterprise" as used in RICO encompasses both legitimate and illegitimate enterprises. Pp. 580-593. (a) Neither the language nor structure of RICO limits its application to legitimate enterprises. On its face, the definition of "enterprise" in 1961 (4) appears to include both legitimate and illegitimate enterprises within its scope. The section describes two separate categories of associations that come within the purview of an "enterprise" - the first encompassing organizations such as corporations, partnerships, and other "legal entities," and the second covering "any union or

group of individuals associated in fact although not a legal entity." The second category is not a more generalized description of the first, and hence the rule of ejusdem generis cannot be properly applied to hold [452 U.S. 576, 577] that the second category should be limited by the specific examples enumerated in the first. Pp. 580-582. (b) With respect to 1962 (c), an "enterprise" is not a "pattern of racketeering activity" but is an entity separate and apart from the pattern of activity in which it engages. In order to secure a conviction, the Government must prove both the existence of an "enterprise" and the connected "pattern of racketeering activity." Pp. 582-583. (c) Applying RICO to illegitimate as well as legitimate enterprises does not render any portion of the statute superfluous nor does it create any structural incongruities within the statute's framework. On the contrary, insulating the wholly criminal enterprise from prosecution under RICO is the more incongruous position. Pp. 583587. (d) Nothing in RICO's legislative history requires a conclusion that the statute is limited in its application to legitimate enterprises. In view of the purposes of the Organized Crime Control Act of 1970 to eradicate organized crime in the United States, it cannot be said that Congress nevertheless confined the reach of the law to only narrow aspects of organized crime, and, in particular, under RICO, to only the infiltration of legitimate business. Pp. 588-593. 632 F.2d 896, reversed. WHITE, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which BURGER, C. J., and BRENNAN, MARSHALL, BLACKMUN, POWELL, REHNQUIST, and STEVENS, JJ., joined. STEWART, J., filed a dissenting statement, post, p. 593. Mark I. Levy argued the cause for the United States. With him on the briefs were Solicitor General McCree, Acting Assistant Attorney General Keeney, Deputy Solicitor General Frey, and Joel M. Gershowitz. John Wall argued the cause for respondent. With him on the brief was Harry C. Mezer. * JUSTICE WHITE delivered the opinion of the Court. Chapter 96 of Title 18 of the United States Code, 18 U.S.C. 1961-1968 (1976 ed. and Supp. III), entitled[452 U.S. 576, 578] Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO), was added to Title 18 by Title IX of the Organized Crime Control Act of 1970, Pub. L. 91-452, 84 Stat. 941. The question in this case is whether the term "enterprise" as used in RICO encompasses both legitimate and illegitimate enterprises or is limited in application to the former. The Court of Appeals for the First Circuit held that Congress did not intend to include within the definition of "enterprise" those organizations which are exclusively criminal. 632

F.2d 896 (1980). This position is contrary to that adopted by every other Circuit that has addressed the issue. 1 We granted certiorari to resolve this conflict. 449 U.S. 1123(1981). I Count Nine of a nine-count indictment charged respondent and 12 others with conspiracy to conduct and participate in the affairs of an enterprise 2 engaged in interstate commerce [452 U.S. 576, 579] through a pattern of racketeering activities, in violation of 18 U.S.C. 1962 (d). 3 The indictment described the enterprise as "a group of individuals associated in fact for the purpose of illegally trafficking in narcotics and other dangerous drugs, committing arsons, utilizing the United States mails to defraud insurance companies, bribing and attempting to bribe local police officers, and corruptly influencing and attempting to corruptly influence the outcome of state court proceedings . . . ." The other eight counts of the indictment charged the commission of various substantive criminal acts by those engaged in and associated with the criminal enterprise, including possession with intent to distribute and distribution of controlled substances, and several counts of insurance fraud by arson and other means. The common thread to all counts was respondent's alleged leadership of this criminal organization through which he orchestrated and participated in the commission of the various crimes delineated in the RICO count or charged in the eight preceding counts. After a 6-week jury trial, in which the evidence focused upon both the professional nature of this organization and the execution of a number of distinct criminal acts, respondent was convicted on all nine counts. He was sentenced to a term of 20 years on the substantive counts, as well as a 2-year special parole term on the drug count. On the RICO conspiracy count he was sentenced to a 20-year concurrent term and fined $20,000. On appeal, respondent argued that RICO was intended [452 U.S. 576, 580] solely to protect legitimate business enterprises from infiltration by racketeers and that RICO does not make criminal the participation in an association which performs only illegal acts and which has not infiltrated or attempted to infiltrate a legitimate enterprise. The Court of Appeals agreed. We reverse. II In determining the scope of a statute, we look first to its language. If the statutory language is unambiguous, in the absence of "a clearly expressed legislative intent to the contrary, that language must ordinarily be regarded as conclusive." Consumer Product Safety Comm'n v. GTE Sylvania, Inc.,447 U.S. 102, 108 (1980). Of course, there is no errorless test for identifying or recognizing "plain" or "unambiguous" language. Also, authoritative administrative constructions should be given the deference to which they are entitled, absurd results are to be avoided and internal inconsistencies in the statute must be dealt with. Trans Alaska Pipeline Rate

Cases, 436 U.S. 631, 643 (1978); Commissioner v. Brown, 380 U.S. 563, 571 (1965). We nevertheless begin with the language of the statute. Section 1962 (c) makes it unlawful "for any person employed by or associated with any enterprise engaged in, or the activities of which affect, interstate or foreign commerce, to conduct or participate, directly or indirectly, in the conduct of such enterprise's affairs through a pattern of racketeering activity or collection of unlawful debt." The term "enterprise" is defined as including "any individual, partnership, corporation, association, or other legal entity, and any union or group of individuals associated in fact although not a legal entity." 1961 (4). There is no restriction upon the associations embraced by the definition: an enterprise includes any union or group of individuals associated in fact. On its face, the definition appears to include both legitimate and illegitimate enterprises within its scope; it no more excludes [452 U.S. 576, 581] criminal enterprises than it does legitimate ones. Had Congress not intended to reach criminal associations, it could easily have narrowed the sweep of the definition by inserting a single word, "legitimate." But it did nothing to indicate that an enterprise consisting of a group of individuals was not covered by RICO if the purpose of the enterprise was exclusively criminal. The Court of Appeals, however, clearly departed from and limited the statutory language. It gave several reasons for doing so, none of which is adequate. First, it relied in part on the rule of ejusdem generis, an aid to statutory construction problems suggesting that where general words follow a specific enumeration of persons or things, the general words should be limited to persons or things similar to those specifically enumerated. See 2A C. Sands, Sutherland on Statutory Construction 47.17 (4th ed. 1973). The Court of Appeals ruled that because each of the specific enterprises enumerated in 1961 (4) is a "legitimate" one, the final catchall phrase - "any union or group of individuals associated in fact" - should also be limited to legitimate enterprises. There are at least two flaws in this reasoning. The rule of ejusdem generis is no more than an aid to construction and comes into play only when there is some uncertainty as to the meaning of a particular clause in a statute. Harrison v. PPG Industries, Inc.,446 U.S. 578, 588 (1980); United States v. Powell, 423 U.S. 87, 91 (1975); Gooch v. United States, 297 U.S. 124, 128 (1936). Considering the language and structure of 1961 (4), however, we not only perceive no uncertainty in the meaning to be attributed to the phrase, "any union or group of individuals associated in fact" but we are convinced for another reason that ejusdem generis is wholly inapplicable in this context. Section 1961 (4) describes two categories of associations that come within the purview of the "enterprise" definition. The first encompasses organizations such as corporations and partnerships, and other "legal entities." The second covers [452 U.S. 576, 582] "any union or group of individuals associated in fact although not a legal entity." The Court of Appeals assumed that the second category was merely a more general description of the first. Having made that assumption, the court concluded that the more generalized description in the second category should be limited by the specific examples enumerated in the first. But that assumption is untenable. Each category describes a separate type of enterprise to be covered by

the statute - those that are recognized as legal entities and those that are not. The latter is not a more general description of the former. The second category itself not containing any specific enumeration that is followed by a general description, ejusdem generis has no bearing on the meaning to be attributed to that part of 1961 (4). 4 A second reason offered by the Court of Appeals in support of its judgment was that giving the definition of "enterprise" its ordinary meaning would create several internal inconsistencies in the Act. With respect to 1962 (c), it was said: "If `a pattern of racketeering' can itself be an `enterprise' for purposes of section 1962 (c), then the two phrases `employed by or associated with any enterprise' and `the conduct of such enterprise's affairs through [a pattern of racketeering activity]' add nothing to the meaning of the section. The words of the statute are coherent and logical only if they are read as applying to legitimate enterprises." 632 F.2d, at 899. [452 U.S. 576, 583] This conclusion is based on a faulty premise. That a wholly criminal enterprise comes within the ambit of the statute does not mean that a "pattern of racketeering activity" is an "enterprise." In order to secure a conviction under RICO, the Government must prove both the existence of an "enterprise" and the connected "pattern of racketeering activity." The enterprise is an entity, for present purposes a group of persons associated together for a common purpose of engaging in a course of conduct. The pattern of racketeering activity is, on the other hand, a series of criminal acts as defined by the statute. 18 U.S.C. 1961 (1) (1976 ed., Supp. III). The former is proved by evidence of an ongoing organization, formal or informal, and by evidence that the various associates function as a continuing unit. The latter is proved by evidence of the requisite number of acts of racketeering committed by the participants in the enterprise. While the proof used to establish these separate elements may in particular cases coalesce, proof of one does not necessarily establish the other. The "enterprise" is not the "pattern of racketeering activity"; it is an entity separate and apart from the pattern of activity in which it engages. The existence of an enterprise at all times remains a separate element which must be proved by the Government. 5 Apart from 1962 (c)'s proscription against participating in an enterprise through a pattern of racketeering activities, RICO also proscribes the investment of income derived from racketeering activity in an enterprise engaged in or which [452 U.S. 576, 584] affects interstate commerce as well as the acquisition of an interest in or control of any such enterprise through a pattern of racketeering activity. 18 U.S.C. 1962 (a) and (b). 6 The Court of Appeals concluded that these provisions of RICO should be interpreted so as to apply only to legitimate enterprises. If these two sections are so limited, the Court of Appeals held that the proscription in 1962 (c), at issue here, must be similarly limited. Again, we do not accept the premise from which the Court of Appeals derived its conclusion. It is obvious that 1962 (a) and (b) address the infiltration by organized crime of legitimate businesses, but we cannot agree that these sections were not also aimed at preventing racketeers from

investing or reinvesting in wholly illegal enterprises and from acquiring through a pattern of racketeering activity wholly illegitimate enterprises such as an illegal gambling business or a loan-sharking [452 U.S. 576, 585] operation. There is no inconsistency or anomaly in recognizing that 1962 applies to both legitimate and illegitimate enterprises. Certainly the language of the statute does not warrant the Court of Appeals' conclusion to the contrary. Similarly, the Court of Appeals noted that various civil remedies were provided by 1964, 7 including divestiture, dissolution, reorganization, restrictions on future activities by violators of RICO, and treble damages. These remedies it thought would have utility only with respect to legitimate enterprises. As a general proposition, however, the civil remedies could be useful in eradicating organized crime from the social fabric, whether the enterprise be ostensibly legitimate or admittedly criminal. The aim is to divest the association of the fruits of its ill-gotten gains. See infra, at 591-593. Even if one or more of the civil remedies might be inapplicable to a particular illegitimate enterprise, this fact would not serve to limit the enterprise concept. Congress has provided civil remedies for use when the circumstances so warrant. It is untenable to argue that their existence limits the scope of the criminal provisions. 8 [452 U.S. 576, 586] Finally, it is urged that the interpretation of RICO to include both legitimate and illegitimate enterprises will substantially alter the balance between federal and state enforcement of criminal law. This is particularly true, so the argument goes, since included within the definition of racketeering activity are a significant number of acts made criminal under state law. 18 U.S.C. 1961 (1) (1976 ed., Supp. III). But even assuming that the more inclusive definition of enterprise will have the effect suggested, 9 the language of the statute and its legislative history indicate that Congress was well aware that it was entering a new domain of federal involvement through the enactment of this measure. Indeed, the very purpose of the Organized Crime Control Act of 1970 was to enable the Federal Government to address a large and seemingly neglected problem. The view was that existing law, state and federal, was not adequate to address the problem, which was of national dimensions. That Congress included within the definition of racketeering activities a number of state crimes strongly indicates that RICO criminalized conduct that was also criminal under state law, at least when the requisite elements of a RICO offense are present. As the hearings and legislative debates reveal, Congress was well aware of the fear that RICO would "mov[e] large substantive areas formerly totally within the police power of[452 U.S. 576, 587] the State into the Federal realm." 116 Cong. Rec. 35217 (1970) (remarks of Rep. Eckhardt). See also id., at 35205 (remarks of Rep. Mikva); id., at 35213 (comments of the American Civil Liberties Union); Hearings on Organized Crime Control before Subcommittee No. 5 of the House Committee on the Judiciary, 91st Cong., 2d Sess., 329, 370 (1970) (statement of Sheldon H. Eisen on behalf of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York). In the face of these objections, Congress nonetheless proceeded to enact the measure, knowing that it would alter somewhat the role of the Federal Government in the war against organized crime and that the alteration would entail

prosecutions involving acts of racketeering that are also crimes under state law. There is no argument that Congress acted beyond its power in so doing. That being the case, the courts are without authority to restrict the application of the statute. See United States v. Culbert, 435 U.S. 371, 379 -380 (1978). Contrary to the judgment below, neither the language nor structure of RICO limits its application to legitimate "enterprises." Applying it also to criminal organizations does not render any portion of the statute superfluous nor does it create any structural incongruities within the framework of the Act. The result is neither absurd nor surprising. On the contrary, insulating the wholly criminal enterprise from prosecution under RICO is the more incongruous position. Section 904 (a) of RICO, 84 Stat. 947, directs that "[t]he provisions of this Title shall be liberally construed to effectuate its remedial purposes." With or without this admonition, we could not agree with the Court of Appeals that illegitimate enterprises should be excluded from coverage. We are also quite sure that nothing in the legislative history of RICO requires a contrary conclusion. 10 [452 U.S. 576, 588] III The statement of findings that prefaces the Organized Crime Control Act of 1970 reveals the pervasiveness of the problem that Congress was addressing by this enactment: "The Congress finds that (1) organized crime in the United States is a highly sophisticated, diversified, and widespread activity that annually drains billions of dollars from America's economy by unlawful conduct and the illegal use of force, fraud, and corruption; (2) organized crime derives a major portion of its power through money obtained from such illegal endeavors as syndicated gambling, loan sharking, the theft and fencing of property, the importation and distribution of narcotics and other dangerous drugs, and other forms of social exploitation; (3) this money and power are increasingly used to infiltrate and corrupt legitimate business and labor unions and to subvert and corrupt our democratic processes; (4) organized crime activities in the United States weaken the stability of the Nation's economic system, harm innocent investors and competing organizations, interfere with free competition, seriously burden interstate and foreign commerce, threaten the domestic security, and undermine the general welfare of the Nation and its citizens; and (5) organized crime continues [452 U.S. 576, 589] to grow because of defects in the evidence-gathering process of the law inhibiting the development of the legally admissible evidence necessary to bring criminal and other sanctions or remedies to bear on the unlawful activities of those engaged in organized crime and because the sanctions and remedies available to the Government are unnecessarily limited in scope and impact." 84 Stat. 922-923. In light of the above findings, it was the declared purpose of Congress "to seek the eradication of organized crime in the United States by strengthening the legal tools

in the evidence-gathering process, by establishing new penal prohibitions, and by providing enhanced sanctions and new remedies to deal with the unlawful activities of those engaged in organized crime." Id., at 923. 11 The various Titles of the Act provide the tools through which this goal is to be accomplished. Only three of those Titles create substantive offenses, Title VIII, which is directed at illegal gambling operations, Title IX, at issue here, and Title XI, which addresses the importation, distribution, and storage of explosive materials. The other Titles provide various procedural and remedial devices to aid in the prosecution and incarceration of persons involved in organized crime. Considering this statement of the Act's broad purposes, the construction of RICO suggested by respondent and the court below is unacceptable. Whole areas of organized criminal activity would be placed beyond the substantive reach of the enactment. For example, associations of persons engaged solely in "loan sharking, the theft and fencing of property, [452 U.S. 576, 590] the importation and distribution of narcotics and other dangerous drugs," id., at 922-923, would be immune from prosecution under RICO so long as the association did not deviate from the criminal path. Yet these are among the very crimes that Congress specifically found to be typical of the crimes committed by persons involved in organized crime, see 18 U.S.C. 1961 (1) (1976 ed., Supp. III), and as a major source of revenue and power for such organizations. See Hearings on S. 30 et al. before the Subcommittee on Criminal Laws and Procedures of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, 91st Cong., 1st Sess., 1-2 (1969). 12 Along these same lines, Senator McClellan, the principal sponsor of the bill, gave two examples of types of problems RICO was designed to address. Neither is consistent with the view that substantive offenses under RICO would be limited to legitimate enterprises: "Organized criminals, too, have flooded the market with cheap reproductions of hit records and affixed counterfeit popular labels. They are heavily engaged in the illicit prescription drug industry." 116 Cong. Rec. 592 (1970). In view of the purposes and goals of the Act, as well as the language of the statute, we are unpersuaded that Congress nevertheless confined the reach of the law to only narrow aspects of organized crime, and, in particular, under RICO, only the infiltration of legitimate business. [452 U.S. 576, 591] This is not to gainsay that the legislative history forcefully supports the view that the major purpose of Title IX is to address the infiltration of legitimate business by organized crime. The point is made time and again during the debates and in the hearings before the House and Senate. 13 But none of these statements requires the negative inference that Title IX did not reach the activities of enterprises organized and existing for criminal purposes. See United States v. Naftalin, 441 U.S. 768, 774 -775 (1979); United States v. Culbert, 435 U.S., at 377 . On the contrary, these statements are in full accord with the proposition that RICO is equally applicable to a criminal enterprise that has no legitimate dimension or has yet to acquire one. Accepting that the primary purpose of RICO is to cope with the infiltration of legitimate businesses, applying the statute in accordance with its terms, so as to reach criminal enterprises, would seek to deal with the problem at

its very source. Supporters of the bill recognized that organized crime uses its primary sources of revenue and power - illegal gambling, loan sharking and illicit drug distribution - as a springboard into the sphere of legitimate enterprise. Hearings on S. 30, supra, at 1-2. The Senate Report stated: "What is needed here, the committee believes, are new approaches that will deal not only with individuals, but also with the economic base through which those individuals [452 U.S. 576, 592] constitute such a serious threat to the economic well-being of the Nation. In short, an attack must be made on their source of economic power itself, and the attack must take place on all available fronts." S. Rep. No. 91-617, p. 79 (1969) (emphasis supplied). Senator Byrd explained in debate on the floor, that "loan sharking paves the way for organized criminals to gain access to and eventually take over the control of thousands of legitimate businesses." 116 Cong. Rec. 606 (1970). Senator Hruska declared that "the combination of criminal and civil penalties in this title offers an extraordinary potential for striking a mortal blow against the property interests of organized crime." Id., at 602. 14 Undoubtedly, the infiltration [452 U.S. 576, 593] of legitimate businesses was of great concern, but the means provided to prevent that infiltration plainly included striking at the source of the problem. As Representative Poff, a manager of the bill in the House, stated: "[T]itle IX . . . will deal not only with individuals, but also with the economic base through which those individuals constitute such a serious threat to the economic well-being of the Nation. In short, an attack must be made on their source of economic power itself . . . ." Id., at 35193. As a measure to deal with the infiltration of legitimate businesses by organized crime, RICO was both preventive and remedial. Respondent's view would ignore the preventive function of the statute. If Congress had intended the more circumscribed approach espoused by the Court of Appeals, there would have been some positive sign that the law was not to reach organized criminal activities that give rise to the concerns about infiltration. The language of the statute, however - the most reliable evidence of its intent - reveals that Congress opted for a far broader definition of the word "enterprise," and we are unconvinced by anything in the legislative history that this definition should be given less than its full effect. The judgment of the Court of Appeals is accordingly Reversed. JUSTICE STEWART agrees with the reasoning and conclusion of the Court of Appeals as to the meaning of the term "enterprise" in this statute. See 632 F.2d 896. Accordingly, he respectfully dissents. [ Footnote * ] Briefs of amici curiae urging affirmance were filed by Harvey A. Silverglate for the Boston Bar Association et al.; and by Barry Tarlow for California Attorneys for Criminal Justice et al.

Footnotes [ Footnote 1 ] See United States v. Sutton, 642 F.2d 1001, 1006-1009 (CA6 1980) (en banc), cert. pending, Nos. 80-6058, 80-6137, 80-6141, 80-6147, 80-6253, 806254, 80-6272; United States v. Errico, 635 F.2d 152, 155 (CA2 1980); United States v. Provenzano, 620 F.2d 985, 992-993 (CA3), cert. denied, 449 U.S. 899 (1980); United States v. Whitehead, 618 F.2d 523, 525, n. 1 (CA4 1980); United States v. Aleman, 609 F.2d 298, 304-305 (CA7 1979), cert. denied, 445 U.S. 946 (1980); United States v. Rone, 598 F.2d 564, 568-569 (CA9 1979), cert. denied, 445 U.S. 946 (1980); United States v. Swiderski, 193 U.S. App. D.C. 92, 94-95, 593 F.2d 1246, 1248-1249 (1978), cert. denied, 441 U.S. 933(1979); United States v. Elliott, 571 F.2d 880, 896-898 (CA5), cert. denied, 439 U.S. 953 (1978). See also United States v. Anderson, 626 F.2d 1358, 1372 (CA8 1980), cert. denied, 450 U.S. 912 (1981). But see United States v. Sutton, 605 F.2d 260, 264-270 (CA6 1979), vacated, 642 F.2d 1001 (1980); United States v. Rone, supra, at 573 (Ely, J., dissenting); United States v. Altese, 542 F.2d 104, 107 (CA2 1976) (Van Graafeiland, J., dissenting), cert. denied, 429 U.S. 1039 (1977). [ Footnote 2 ] Title 18 U.S.C. 1961 (4) provides: "`enterprise' includes any individual, partnership, corporation, association, or other legal entity, and any union or group of individuals associated in fact although not a legal entity." [ Footnote 3 ] Title 18 U.S.C. 1962 (d) provides that "[i]t shall be unlawful for any person to conspire to violate any of the provisions of subsections (a), (b), or (c) of this section." Pertinent to these charges, subsection (c) provides: "It shall be unlawful for any person employed by or associated with any enterprise engaged in, or the activities of which affect, interstate or foreign commerce, to conduct or participate, directly or indirectly, in the conduct of such enterprise's affairs through a pattern of racketeering activity or collection of unlawful debt." [ Footnote 4 ] The Court of Appeals' application of ejusdem generis is further flawed by the assumption that "any individual, partnership, corporation, association or other legal entity" could not act totally beyond the pale of the law. The mere fact that a given enterprise is favored with a legal existence does not prevent that enterprise from proceeding along a wholly illegal course of conduct. Therefore, since legitimacy of purpose is not a universal characteristic of the specifically listed enterprises, it would be improper to engraft this characteristic upon the second category of enterprises. [ Footnote 5 ] The Government takes the position that proof of a pattern of racketeering activity in itself would not be sufficient to establish the existence of an enterprise: "We do not suggest that any two sporadic and isolated offenses by the same actor or actors ipso facto constitute an `illegitimate' enterprise; rather, the existence of the enterprise as an independent entity must also be shown." Reply Brief for United States 4. But even if that were not the case, the Court of Appeals'

position on this point is of little force. Language in a statute is not rendered superfluous merely because in some contexts that language may not be pertinent. [ Footnote 6 ] Title 18 U.S.C. 1962 (a) and (b) provide: "(a) It shall be unlawful for any person who has received any income derived, directly or indirectly, from a pattern of racketeering activity or through collection of an unlawful debt in which such person has participated as a principal within the meaning of section 2, title 18, United States Code, to use or invest, directly or indirectly, any part of such income, or the proceeds of such income, in acquisition of any interest in, or the establishment or operation of, any enterprise which is engaged in, or the activities of which affect, interstate or foreign commerce. A purchase of securities on the open market for purposes of investment, and without the intention of controlling or participating in the control of the issuer, or of assisting another to do so, shall not be unlawful under this subsection if the securities of the issuer held by the purchaser, the members of his immediate family, and his or their accomplices in any pattern or racketeering activity or the collection of an unlawful debt after such purchase do not amount in the aggregate to one percent of the outstanding securities of any one class, and do not confer, either in law or in fact, the power to elect one or more directors of the issuer. "(b) It shall be unlawful for any person through a pattern of racketeering activity or through collection of an unlawful debt to acquire or maintain, directly or indirectly, any interest in or control of any enterprise which is engaged in, or the activities of which affect, interstate or foreign commerce." [ Footnote 7 ] Title 18 U.S.C. 1964 (a) and (c) provide: "(a) The district courts of the United States shall have jurisdiction to prevent and restrain violations of section 1962 of this chapter by issuing appropriate orders, including, but not limited to: ordering any person to divest himself of any interest, direct or indirect, in any enterprise; imposing reasonable restrictions on the future activities or investments of any person, including, but not limited to, prohibiting any person from engaging in the same type of endeavor as the enterprise engaged in, the activities of which affect interstate or foreign commerce; or ordering dissolution or reorganization of any enterprise, making due provision for the rights of innocent persons. ..... "(c) Any person injured in his business or property by reason of a violation of section 1962 of this chapter may sue therefor in any appropriate United States district court and shall recover threefold the damages he sustains and the cost of the suit, including a reasonable attorney's fee." [ Footnote 8 ] In discussing these civil remedies, the Senate Report on the Organized Crime Control Act of 1970 specifically referred to two state cases in which [452 U.S. 576, 586] equitable relief had been granted against illegitimate

enterprises. S. Rep. No. 91-617, p. 79, n. 9, p. 81, n. 11 (1969). These references were in the context of a discussion on the need to expand the remedies available to combat organized crime. [ Footnote 9 ] RICO imposes no restrictions upon the criminal justice systems of the States. See 84 Stat. 947 ("Nothing in this title shall supersede any provision of Federal, State, or other law imposing criminal penalties or affording civil remedies in addition to those provided for in this title"). Thus, under RICO, the States remain free to exercise their police powers to the fullest constitutional extent in defining and prosecuting crimes within their respective jurisdictions. That some of those crimes may also constitute predicate acts of racketeering under RICO, is no restriction on the separate administration of criminal justice by the States. [ Footnote 10 ] We find no occasion to apply the rule of lenity to this statute. "[T]hat `rule,' as is true of any guide to statutory construction, only serves as an aid for resolving an ambiguity; it is not to be used to beget one. . . . The rule comes into operation at the end of the process of [452 U.S. 576, 588] construing what Congress has expressed, not at the beginning as an overriding consideration of being lenient to wrongdoers." Callanan v. United States, 364 U.S. 587, 596 (1961) (footnote omitted). There being no ambiguity in the RICO provisions at issue here, the rule of lenity does not come into play. See United States v. Moore, 423 U.S. 122, 145 (1975), quoting United States v. Brown, 333 U.S. 18, 25 -26 (1948) ("`The canon in favor of strict construction [of criminal statutes] is not an inexorable command to override common sense and evident statutory purpose . . . . Nor does it demand that a statute be given the "narrowest meaning"; it is satisfied if the words are given their fair meaning in accord with the manifest intent of the lawmakers'"); see also Lewis v. United States, 445 U.S. 55, 60 -61 (1980). [ Footnote 11 ] See also 116 Cong. Rec. 602 (1970) (remarks of Sen. Yarborough) ("a full scale attack on organized crime"); id., at 819 (remarks of Sen. Scott) ("purpose is to eradicate organized crime in the United States"); id., at 35199 (remarks of Rep. Rodino) ("a truly full-scale commitment to destroy the insidious power of organized crime groups"); id., at 35300 (remarks of Rep. Mayne) (organized crime "must be sternly and irrevocably eradicated"). [ Footnote 12 ] See also id., at 601 (remarks of Sen. Hruska); id., at 606-607 (remarks of Sen. Byrd); id., at 819 (remarks of Sen. Scott); id., at 962 (remarks of Sen. Murphy); id., at 970 (remarks of Sen. Bible); id., at 18913, 18937 (remarks of Sen. McClellan); id., at 35199 (remarks of Rep. Rodino); id., at 35216 (remarks of Rep. McDade); id., at 35300 (remarks of Rep. Mayne); id., at 35312 (remarks of Rep. Brock); id., at 35319 (remarks of Rep. Anderson of California); id., at 35326 (remarks of Rep. Vanik); id., at 35328 (remarks of Rep. Meskill); Hearings on S. 30 et al. before the Subcommittee on Criminal Laws and Procedures of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, 91st Cong., 1st Sess., 108 (1969) (statement of Attorney General Mitchell); H. R. Rep. No. 1574, 90th Cong., 2d Sess., 5 (1968).

[ Footnote 13 ] 116 Cong. Rec. 591 (1970) (remarks of Sen. McClellan) ("title IX is aimed at removing organized crime from our legitimate organizations"); id., at 602 (remarks of Sen. Hruska) ("Title IX of this act is designed to remove the influence of organized crime from legitimate business by attacking its property interests and by removing its members from control of legitimate businesses which have been acquired or operated by unlawful racketeering methods"); id., at 607 (remarks of Sen. Byrd) ("alarming expansion into the field of legitimate business"); id., at 953 (remarks of Sen. Thurmond) ("racketeers . . . gaining inroads into legitimate business"); id., at 845 (remarks of Sen. Kennedy) ("title IX . . . may provide us with new tools to prevent organized crime from taking over legitimate businesses and activities"); S. Rep. No. 91-617, p. 76 (1969). [ Footnote 14 ] See also, e. g., 115 Cong. Rec. 827 (1969) (remarks of Sen. McClellan) ("Organized crime . . . uses its ill-gotten gains . . . to infiltrate and secure control of legitimate business and labor union activities"); 116 Cong. Rec. 591 (1970) (remarks of Sen. McClellan) ("illegally gained revenue also makes it possible for organized crime to infiltrate and pollute legitimate business"); id., at 603 (remarks of Sen. Yarborough) ("[RICO] is designed to root out the influence of organized crime in legitimate business, into which billions of dollars of illegally obtained money is channeled"); id., at 606 (remarks of Sen. Byrd) ("loan sharking paves the way for organized criminals to gain access to and eventually take over the control of thousands of legitimate businesses"); id., at 35193 (remarks of Rep. Poff) ("[T]itle IX . . . will deal not only with individuals, but also with the economic base through which those individuals constitute such a serious threat to the economic well-being of the Nation. In short, an attack must be made on their source of economic power itself . . ."); S. Rep. No. 91-617, supra, at 78-80; H. R. Rep. No. 1574, supra, at 5 ("The President's Crime Commission found that the greatest menace that organized crime presents is its ability through the accumulation of illegal gains to infiltrate into legitimate business and labor unions"); Hearings on Organized Crime Control before Subcommittee No. 5 of the House Committee on the Judiciary, 91st Cong., 2d Sess., 170 (1970) (Department of Justice Comments) ("Title IX is designed to inhibit the infiltration of legitimate business by organized crime, and, like the previous title, to reach the criminal syndicates' major sources of revenue") (emphasis supplied). [452 U.S. 576, 594] HERE IS ANOTHER LINK:

http://www.oyez.org/cases/1980-1989/1980/1980_80_808/argument

http://www.oyez.org/api/media/sites/default/files/audio/cases/1980/80808_19810427-argument.mp3 656 F.2d 5

UNITED STATES of America, Appellee, v. Novia TURKETTE, Jr., Appellant. UNITED STATES of America, Appellee, v. John VARGAS, Appellant. Nos. 79-1545, 79-1546. United States Court of Appeals, First Circuit. Argued June 6, 1981. Decided Aug. 13, 1981. Alfred Paul Farese, Everett, Mass., for appellant, NoviaTurkette, Jr. John Wall and Harry C. Mezer, Boston, Mass., with whom Cullen & Wall, Boston, Mass., was on brief, for appellant, John Vargas. William C. Bryson, Dept. of Justice, Washington, D.C., with whom Edward F. Harrington, U.S. Atty., Martin D. Boudreau, Sp. Atty., Boston, Mass., and Joel M. Gershowitz, Dept. of Justice, Washington, D.C., were on brief, for appellee. Before COFFIN, Chief Judge, BOWNES, Circuit Judge, and BOYLE, * District Judge. BOWNES, Circuit Judge. 1 Now that the Supreme Court has reversed us and decided, contrary to our opinion, that the term "enterprise" as used in the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) encompasses both legitimate and illegitimate enterprises, United States v. Turkette, --- U.S. ----, 101 S.Ct. 2524, 69 L.Ed.2d 246 (1981), we turn to the other issues in these cases. 2 A short case history is in order. The nine-count indictment named thirteen defendants. Prior to trial seven defendants pleaded guilty. Mistrials were granted during the course of the trial to two defendants. At the close of the Government's case, the court dismissed the RICO conspiracy count (Nine) against John Vargas. When the case went to the jury, the defendants were NoviaTurkette, Jr., John Vargas, Phillip A. Fraher, Jr., and Gabriel DeMarco. The lineup of defendants and the indictment was: 3 Count One, distribution of Schedule II controlled substances Turkette and Fraher;

4 Count Two, mail fraud based on an arson generated insurance claim Turkette and Vargas; 5 Count Three, mail fraud based on an arson generated insurance claim Turkette and Vargas; 6 Count Four, mail fraud based on an arson generated insurance claim Turkette and Vargas; 7 Count Five, mail fraud based on an arson generated insurance claim Turkette and Vargas; 8 Count Six, mail fraud based on a false insurance claim for a stolen car (car was deliberately burned) Turkette and Fraher; 9 Count Seven, mail fraud based on a false insurance claim for a stolen car Turkette and Fraher; 10 Count Eight, mail fraud based on a false insurance claim for a stolen car Turkette; 11 Count Nine, the RICO conspiracy count Turkette, Fraher and DeMarco. 12 Turkette was convicted on all nine counts. Fraher was convicted on Counts Six and Seven and acquitted on Counts One and Nine. DeMarco was acquitted on Count Nine, the only one charged. Vargas was convicted on Count Two and acquitted on Counts Three, Four and Five. 13 We note at the outset that neither defendant has seriously challenged the sufficiency of the evidence. Our review of the trial transcripts reveals a solid evidentiary footing for the verdict. See our prior opinion for a summary of the evidence. United States v. Turkette, 632 F.2d 896, 908-09 (1st Cir. 1980), rev'd, --U.S. ----, 101 S.Ct. 2524, 69 L.Ed.2d 246 (1981).

14 We first consider the claims of defendant Vargas: 15 1. That joinder was improper initially and the district court erred in not granting severance during the trial; 16 2. That the court-ordered seating arrangement was prejudicial; and 17 3. That the court erred in refusing to give two requested instructions. Joinder and Severance 18 We now reconsider the issue of joinder and severance in the light of the Supreme Court's holding that RICO applies to this case. Vargas' first argument is that joinder was improper under Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 8(b) 1 because the indictment did not allege that he knew that there was a diverse criminal enterprise or that he intended to associate himself with it and was, therefore, legally insufficient. Count Nine of the indictment simply does not admit of such a reading. It alleged that Vargas was an associate of Turkette (Para. 1(k)), that all named defendants were associated as an "enterprise" for the purpose of illegally trafficking in narcotics and other dangerous drugs, committing arsons, using the mail to defraud insurance companies, bribing police officers and attempting to corruptly influence state court trials (Para. 1(o)), that the defendants conspired to violate 18 U.S.C. 1962(c) (Para. 2), that the defendants, as part of the conspiracy, would engage in a pattern of racketeering activity affecting interstate commerce (Para. 3), that as part of the conspiracy Vargas and Turkette would burn two houses and submit fire insurance claims for their value (Paras. 5, 6, 7 & 8). We think Count Nine of the Indictment was legally sufficient. It alleged that Vargas joined a criminal enterprise, knew the criminal activities that were to be conducted and agreed to participate in the enterprise by committing two acts of arson so as to obtain insurance payments. Defendant's reliance on United States v. Diecidue, 603 F.2d 535 (5th Cir. 1979), cert. denied, 446 U.S. 912, 100 S.Ct. 1842, 64 L.Ed.2d 266 (1980), and United States v. Elliott, 571 F.2d 880 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, 439 U.S. 953, 99 S.Ct. 349, 58 L.Ed.2d 344 (1978), is misplaced. In each of those cases the court found that the evidence was not sufficient to sustain a conviction on the RICO conspiracy count as to one of the defendants. Neither Diecidue nor Elliott suggest any grounds for holding this indictment legally invalid. 19

The next ground advanced for invoking Rule 8(b) is that the RICO count was brought without a reasonable evidentiary foundation. We construe this to mean that Vargas claims that the Government acted in bad faith in including him in Count Nine. RICO permits the Government to cast a wider net than it could under traditional conspiracy principles. See United States v. Elliott, 571 F.2d at 902. Thus, the breadth of Count Nine does not, in itself, evidence bad faith on the part of the Government. Nor does the Government's failure to prove that Vargas was a conspirator show bad faith. In United States v. Luna, 585 F.2d 1, 4 (1st Cir.), cert. denied, 439 U.S. 852, 99 S.Ct. 160, 58 L.Ed.2d 157 (1978), we held that a jury acquittal on a conspiracy count did not prove "the impropriety of having joined the offenses and accused individuals in the same indictment." We do not think that the district court's granting defendant's motion for a judgment of acquittal on the conspiracy charge at the end of the Government's case demonstrates bad faith. Finally, Vargas has not introduced any independent evidence of bad faith. "A defendant alleging prosecutorial bad faith in joining multiple counts has the burden of establishing it." Id. at 4. We think the same rule applies to joinder of defendants. Based on our review of the evidence, we cannot say, without more, that the Government acted in bad faith. The RICO conspiracy count supplies the bond necessary to join Vargas with the other defendants because all are charged with participating "in the same series of acts or transactions constituting an offense or offenses." Fed.R.Crim.P. 8(b). It follows that there was no Rule 8(b) violation. 20 The next question is whether the court should have ordered a severance under Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 14.2 The standard of review is abuse of discretion. To prevail, the defendant must make a strong showing of prejudice. Id. at 4-5. Vargas's position is that the evidence against Turkette relative to the drug distribution operation would not have been admissible against him in a separate trial on mail fraud alone and, therefore, the introduction of such evidence was bound to unfairly prejudice him. In any conspiracy case there is a danger that the bad acts of one conspirator may slop over onto the other defendants. In a case with a RICO conspiracy count it is inevitable that some of the peripheral participants will be tarred by the brush of the entire criminal enterprise. The answer, however, is not automatic severance, but careful control of the case by the trial judge, as was exercised here. This case started with six defendants and ended up with four. We think the jury must have understood from the way the trial proceeded that each defendant was to be judged separately. The dismissal of the RICO count as to Vargas could only have highlighted for them that there must be an individualized assessment of the evidence. And the court's instructions on this was clear and complete. Furthermore, "(n)either the number of counts nor the number of defendants was so large as to give rise to concern that the jury could not differentiate among them." Id. at 5. Nor can we ignore the jury's verdict which reflects a careful dissection of the evidence as it applied to each defendant. Although we do not think that the issue of prejudicial joinder, either under Rule 8 or 14, should hinge on whether the jury returned a discriminating verdict, that is a

factor to be taken into consideration. See United States v. Richman, 600 F.2d 286, 299-300 (1st Cir. 1979). We find no abuse of discretion in the court's refusal to order a severance and, therefore, no violation of Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 14. The Seating Arrangement 21 This claim borders on the frivolous. At the start of the trial the district court directed the defendants to sit together in the first row of the spectator's section of the courtroom and excluded all others from that area. The only defendant to object to this was Vargas. His first argument is that the district court established "a prisoner's row" similar to the use of the dock in Massachusetts which was criticized by us in Walker v. Butterworth, 599 F.2d 1074, 1080-81 (1st Cir.), cert. denied, 444 U.S. 937, 100 S.Ct. 288, 62 L.Ed.2d 197 (1979). We think the analogy inapt; the dock is a four-foot high box in which the accused is isolated. In Walker we pointed out that its use might be analogized to wearing prison clothes during a trial, which was held unconstitutional in Estelle v. Williams, 425 U.S. 501, 96 S.Ct. 1691, 48 L.Ed.2d 126 (1976). Here, the defendants sat in the front row of the spectator's area of the courtroom, hardly a place calculated to strip an accused of his presumption of innocence in the eyes of the jury. The defendants were no more isolated than they would have been if seated with their attorneys, as is ordinarily the case. 22 As to the argument that the seating arrangement suggested to the jurors that they should infer the guilt of all from the guilt of one, we only remark that the defendants had to be seated somewhere, and from the start of the trial the jury knew that all of them, including Vargas, were charged with conspiracy. If the jury received a suggestion of guilt by association, and their verdict belies this, it was the result of the conspiracy charge, not the seating arrangement. 23 Moreover, this is a matter best left to the discretion of the trial court. How to arrange the seating for defendants and counsel depends upon such a variety of factors, e. g., the size of the courtroom, the number of spectators, the number of defendants and lawyers, acoustics, security provisions, etc., that we would be loathe to interfere unless there was a clearcut abuse of discretion. See United States v. Rios Ruiz, 579 F.2d 670, 674 (1st Cir. 1978). It is significant that Vargas does not claim that he could not communicate effectively with his attorney during the trial, nor has he suggested an alternative seating arrangement. There was no abuse of discretion. The Failure To Give Requested Instructions 24

1. The Requested Instruction Concerning Bribery Payments 25 The chief Government witness was Kenneth Landers, Turkette's principal associate in the enterprise and the crimes charged. He testified that Turkette and his father paid him money, bought him a car and promised him more money not to testify at the trial. Vargas requested that the court caution the jury not to infer from the bribery any consciousness of guilt on the part of any defendant unless the jury could find beyond a reasonable doubt that a particular defendant was involved in the robbery. The requested instruction used the words of 1 Devitt and Blackmar, Federal Jury Instructions 15.10, at 465-66 (1977). Although the court did not give the instruction as requested, it did cover the matter adequately. At the time Landers started to testify about the bribes the jury was told that it was not to consider the conversations "against the defendants who were not parties to the conversation on the one-hand, or who were not present at the meeting on the other hand." The charge to the jury emphasized that "it is your duty to give separate personal consideration to the case of each individual defendant." This was elaborated on and explicated fully. In addition, the court charged specifically as to Vargas: 26 I want to remind you that I excluded a lot of evidence in this case and did not admit it as to Mr. Vargas. I admitted it as to other defendants. That exclusionary order is still in effect and should be observed by you. The evidence as to the drug store robberies, drug sales, the payoffs to Charlie Werner and other evidence, which I am sure you will recall, I allowed in as to the three defendants other than Vargas. Whether or not Vargas is guilty on any one of these four counts is to be decided without reference to that evidence which was admitted only as to the other defendants and Counts 2, 3, 4 and 5 as to Mr. Vargas are to be decided on the evidence which was admitted as to him. 27 The words of Devitt and Blackmar might have added some frosting to the cake, but the court's instructions were ample fare and easily digested. 28 2. Failure To Give an Instruction Based on Defendant's Theory of the Case 29 Vargas fails to quote in his brief the requested instructions and has not even bothered to refer to it by number. We, therefore, rely on the Government's brief which identifies it as Vargas' requested instruction No. 23. After reading the request,3 we agree with the Government that it was not a theory of the case request but combined comments on the evidence with a request for a cautionary

instruction as to Landers' testimony. The comments were correctly ignored by the court and the cautionary instruction was given, although not in the language requested. 30 We now turn to the case of NoviaTurkette, Jr. The Supreme Court's decision has effectively demolished his claim of prejudicial joinder and we need spend no time on it. 31 The only issue is whether the district court erred in allowing Vargas to introduce in evidence photographs that Turkette alleges were illegally seized because not described in the warrant. The photos did not show Turkette engaged in any criminal activity; they were group pictures of Turkette and certain of the other defendants. Vargas, who was not in the picture, introduced them to prove that he was not associated with Turkette and the other defendants. Although we have not been told how Vargas knew of the photos, Turkette does not claim that the Government used Vargas as a conduit for introducing evidence that it could not put in its case-inchief.4 32 We need not decide whether the exclusionary rule applies in these circumstances because the photos were not prejudicial. In light of Turkette's conviction on all counts, the prejudice, if any, would be to those photographed with him. 33 The convictions in both cases are affirmed. * Of the District of Rhode Island, sitting by designation 1 Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 8(b) provides: (b) Joinder of Defendants. Two or more defendants may be charged in the same indictment or information if they are alleged to have participated in the same act or transaction or in the same series of acts or transactions constituting an offense or offenses. Such defendants may be charged in one or more counts together or separately and all of the defendants need not be charged in each count. 2 Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 14 provides in pertinent part:

If it appears that a defendant or the government is prejudiced by a joinder of offenses or of defendants in an indictment or information or by such joinder for trial together, the courts may order an election or separate trials of counts, grant a severance of defendants or provide whatever other relief justice requires. 3 Vargas' requested instruction No. 23 was as follows: In regard to the allegations of mail fraud, the Defendant John Vargas takes the position that the Government has failed to prove his guilt to a moral certainty and beyond a reasonable doubt. The only evidence upon which the Government relies to prove that the Defendant John Vargas was involved in or had knowledge of the alleged arsons comes from the testimony of Kenneth Landers, a/k/a George Gobel. In deciding what weight, if any, you will give this testimony, you must consider that Landers is an immunized accomplice and an admitted liar whose testimony is therefore highly suspect. In addition, you should also consider the personal motive of Landers to testify against John Vargas which you may find to have arisen out of an unrelated confrontation between them. 4 The Government disputes that there was an illegal seizure, claiming that the pictures were in plain view

Você também pode gostar

- United States v. Turkette, 452 U.S. 576 (1981)Documento15 páginasUnited States v. Turkette, 452 U.S. 576 (1981)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- 452 US 576 US V TURKETTE - RICODocumento11 páginas452 US 576 US V TURKETTE - RICOTiggle MadaleneAinda não há avaliações

- US V TurketteDocumento12 páginasUS V TurketteNay GasuAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Novia Turkette, JR., United States of America v. John Vargas, 632 F.2d 896, 1st Cir. (1980)Documento22 páginasUnited States v. Novia Turkette, JR., United States of America v. John Vargas, 632 F.2d 896, 1st Cir. (1980)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- 6th Juris MateriaDocumento55 páginas6th Juris MateriaRitesh kumarAinda não há avaliações

- HJ Inc. v. Northwestern Bell Telephone Co., 492 U.S. 229 (1989)Documento21 páginasHJ Inc. v. Northwestern Bell Telephone Co., 492 U.S. 229 (1989)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- In Forma Pauperis Fraud by The Judiciary of The County of Lancaster and The Common Pleas Court October 9, 2015Documento65 páginasIn Forma Pauperis Fraud by The Judiciary of The County of Lancaster and The Common Pleas Court October 9, 2015Stan J. Caterbone33% (3)

- Calleja v. Exec. Secretary DigestDocumento15 páginasCalleja v. Exec. Secretary DigestCassie GacottAinda não há avaliações

- Basco Vs PagcorDocumento21 páginasBasco Vs PagcoracaylarveronicayahooAinda não há avaliações

- Stamped Superior Court Re in Forma Pauperis Application Case No. 1915 Mda 2015 November 13, 2015Documento31 páginasStamped Superior Court Re in Forma Pauperis Application Case No. 1915 Mda 2015 November 13, 2015Stan J. Caterbone0% (1)

- Proper Federal Indictment ProcedureDocumento16 páginasProper Federal Indictment ProcedureTruthsPressAinda não há avaliações

- United States Court of Appeals, First CircuitDocumento13 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals, First CircuitScribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Richard Becker and Jack Eisen, 461 F.2d 230, 2d Cir. (1972)Documento8 páginasUnited States v. Richard Becker and Jack Eisen, 461 F.2d 230, 2d Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- White Light Corporation Vs City of Manila, 576 SCRA 416, January 20, 2009Documento34 páginasWhite Light Corporation Vs City of Manila, 576 SCRA 416, January 20, 2009phoebelazAinda não há avaliações

- Perrin v. United States, 444 U.S. 37 (1979)Documento12 páginasPerrin v. United States, 444 U.S. 37 (1979)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Module 4 CasesDocumento15 páginasModule 4 CasesKodeconAinda não há avaliações

- United Union of Roofers, Waterproofers and Allied Workers, Union No. 33 v. Edwin Meese, Attorney General of The United States of America, 823 F.2d 652, 1st Cir. (1987)Documento11 páginasUnited Union of Roofers, Waterproofers and Allied Workers, Union No. 33 v. Edwin Meese, Attorney General of The United States of America, 823 F.2d 652, 1st Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Criminal Liability of Corporations Is Not A Universal Feature of Modern Legal SystemsDocumento16 páginasCriminal Liability of Corporations Is Not A Universal Feature of Modern Legal SystemsAnonymous d6WYxHlAinda não há avaliações

- CI-15-10167 Lancaster County Court MOTION For Leave To File in Forma Pauperis Caterbone V Brunswick-Fitzwater-Lancaster Film November 24, 2015Documento9 páginasCI-15-10167 Lancaster County Court MOTION For Leave To File in Forma Pauperis Caterbone V Brunswick-Fitzwater-Lancaster Film November 24, 2015Stan J. CaterboneAinda não há avaliações

- Louis Henkin, The President and International LawDocumento9 páginasLouis Henkin, The President and International LawmhrelomarAinda não há avaliações

- Beat The Law - How To Get DiplomaticDocumento7 páginasBeat The Law - How To Get Diplomaticrifishman96% (47)

- Outline Corporate Law: On Philippine Atty. Cesar L. VillanuevaDocumento48 páginasOutline Corporate Law: On Philippine Atty. Cesar L. VillanuevaJosephine Carbunera Dacayana-MatosAinda não há avaliações

- PRESIDENT OBAMA DEFENDANT EXHIBIT of October 23, 2015 RECONSTRUCTED JANUARY 14, 2017Documento258 páginasPRESIDENT OBAMA DEFENDANT EXHIBIT of October 23, 2015 RECONSTRUCTED JANUARY 14, 2017Stan J. CaterboneAinda não há avaliações

- 130333-1991-Basco v. Philippine Amusements and Gaming20160212-374-144b11a PDFDocumento16 páginas130333-1991-Basco v. Philippine Amusements and Gaming20160212-374-144b11a PDFlovekimsohyun89Ainda não há avaliações

- NY State Foreign Exemptions Official Legal Memorandum Proves No STILAS ViolationDocumento4 páginasNY State Foreign Exemptions Official Legal Memorandum Proves No STILAS ViolationSTILAS Board of Supervising AttorneysAinda não há avaliações

- Philippine Association of Service Exporters Vs DrilonDocumento22 páginasPhilippine Association of Service Exporters Vs DrilonJerome LeañoAinda não há avaliações

- SEO-Optimized Title for Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corporation CaseDocumento18 páginasSEO-Optimized Title for Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corporation CaseLance LagmanAinda não há avaliações

- Constitutional provisions and doctrinal cases on labor protectionDocumento188 páginasConstitutional provisions and doctrinal cases on labor protectionFritzie G. PuctiyaoAinda não há avaliações

- Constitutional Law 2 Case DigestsDocumento15 páginasConstitutional Law 2 Case DigestsRed Hood100% (2)

- Construction of Each StatuteDocumento9 páginasConstruction of Each StatuteAffle John LeonorAinda não há avaliações

- Corp Law Outline 2001Documento46 páginasCorp Law Outline 2001Nash Chini TaAinda não há avaliações

- Wylie Vs RarangDocumento12 páginasWylie Vs Raranglovekimsohyun89Ainda não há avaliações

- SC upholds constitutionality of tax under Sugar Adjustment ActDocumento14 páginasSC upholds constitutionality of tax under Sugar Adjustment ActMirafelAinda não há avaliações

- 2018 CORPORATE LAW Outline (Atty Joey Hofilena) 2Documento65 páginas2018 CORPORATE LAW Outline (Atty Joey Hofilena) 2JoVic20200% (1)

- Lchong v. Hernandez, G.R. No. L-7995, May 31, 1957Documento22 páginasLchong v. Hernandez, G.R. No. L-7995, May 31, 1957AkiNiHandiongAinda não há avaliações

- White Light Corp vs. City of ManilaDocumento31 páginasWhite Light Corp vs. City of Manilapoiuytrewq9115Ainda não há avaliações

- Thomas H. Fitzgerald v. Martin P. Catherwood, As Industrial Commissioner of The State of New York, 388 F.2d 400, 2d Cir. (1968)Documento10 páginasThomas H. Fitzgerald v. Martin P. Catherwood, As Industrial Commissioner of The State of New York, 388 F.2d 400, 2d Cir. (1968)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Police Power and Its LimitationsDocumento8 páginasPolice Power and Its LimitationsDomski Fatima CandolitaAinda não há avaliações

- Case Digest For Stat ConDocumento10 páginasCase Digest For Stat Concarl fuerzasAinda não há avaliações

- Finalized Impeachment Complaint v. Comm. Andres BautistaDocumento24 páginasFinalized Impeachment Complaint v. Comm. Andres BautistaRapplerAinda não há avaliações

- David Vs ArroyoDocumento42 páginasDavid Vs ArroyoKarina Katerin BertesAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Knight, 659 F.3d 1285, 10th Cir. (2011)Documento18 páginasUnited States v. Knight, 659 F.3d 1285, 10th Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Digested Consti 2 CasesDocumento20 páginasDigested Consti 2 CasesThessaloe B. FernandezAinda não há avaliações

- 03 Shauf V CADocumento19 páginas03 Shauf V CAanneAinda não há avaliações

- Cases Feb 19Documento20 páginasCases Feb 19Carty MarianoAinda não há avaliações

- Corporation Law Historical BackgroundDocumento10 páginasCorporation Law Historical BackgroundpawsmasonAinda não há avaliações

- Ichong v. Hernandez, G.R. No. L-7995, May 31, 1957Documento19 páginasIchong v. Hernandez, G.R. No. L-7995, May 31, 1957Jelena SebastianAinda não há avaliações

- S1 (8) Ichong Vs HernandezDocumento13 páginasS1 (8) Ichong Vs HernandezNeil NaputoAinda não há avaliações

- Application of Article 2180 To Criminal Acts. - : Vicarious LiabilityDocumento2 páginasApplication of Article 2180 To Criminal Acts. - : Vicarious LiabilityDon CorleoneAinda não há avaliações

- Estrada v. Sandiganbayan G.R. No. 14560, 36 SCRA 394 (November 19, 2001) FactsDocumento3 páginasEstrada v. Sandiganbayan G.R. No. 14560, 36 SCRA 394 (November 19, 2001) FactsYhanna Patricia MartinezAinda não há avaliações

- (Consti 2 DIGEST) 148 - Ichong Vs Hernandez (Supra)Documento14 páginas(Consti 2 DIGEST) 148 - Ichong Vs Hernandez (Supra)Junnah MontillaAinda não há avaliações

- Labor Law Review - Atty V DuanoDocumento75 páginasLabor Law Review - Atty V DuanoMcel Padiernos100% (12)

- 7-Ichong Vs HernandezDocumento31 páginas7-Ichong Vs Hernandezmarkhan18Ainda não há avaliações

- Poli - Art 3 Sec 1 Due ProcessDocumento119 páginasPoli - Art 3 Sec 1 Due ProcessmimimilkteaAinda não há avaliações

- Corporation Code Refresher pt1Documento11 páginasCorporation Code Refresher pt1Jenica TiAinda não há avaliações

- Calleja Vs Executive Secretary DigestDocumento15 páginasCalleja Vs Executive Secretary Digestztu32941Ainda não há avaliações

- Lozano v. Martinez, 146 SCRA 323 (1986)Documento3 páginasLozano v. Martinez, 146 SCRA 323 (1986)Digesting FactsAinda não há avaliações

- 125389-1997-Defensor Santiago v. Commission On Elections20220117-11-1g5828uDocumento48 páginas125389-1997-Defensor Santiago v. Commission On Elections20220117-11-1g5828uEsther MozoAinda não há avaliações

- Fire & Smoke: Government, Lawsuits, and the Rule of LawNo EverandFire & Smoke: Government, Lawsuits, and the Rule of LawAinda não há avaliações

- Holmes - Rubin OpinionDocumento20 páginasHolmes - Rubin OpinionMarina ReadAinda não há avaliações

- FDIC Website Search - Power of Attorney - OneWest Bank and MOREDocumento3 páginasFDIC Website Search - Power of Attorney - OneWest Bank and MOREMarina ReadAinda não há avaliações

- CA Appellate CRT - Criteria For Publishing A RulingDocumento1 páginaCA Appellate CRT - Criteria For Publishing A RulingMarina ReadAinda não há avaliações

- CA CC Oath of Office (Judges)Documento1 páginaCA CC Oath of Office (Judges)Marina ReadAinda não há avaliações

- CA SOS Mers Suspended 2002-5-21Documento1 páginaCA SOS Mers Suspended 2002-5-21Marina ReadAinda não há avaliações

- A Summary of The Rules of EvidenceDocumento27 páginasA Summary of The Rules of EvidenceMarina ReadAinda não há avaliações

- CA CC Oath of Office (Judges)Documento1 páginaCA CC Oath of Office (Judges)Marina ReadAinda não há avaliações

- A Summary of The Rules of EvidenceDocumento27 páginasA Summary of The Rules of EvidenceMarina ReadAinda não há avaliações

- Following The Money: The Beneficiaries of Fraudulent Mortgage AssignmentsDocumento14 páginasFollowing The Money: The Beneficiaries of Fraudulent Mortgage AssignmentsMarina ReadAinda não há avaliações

- IndyMac - Deutsche - PSA (1) 3-1-2006Documento204 páginasIndyMac - Deutsche - PSA (1) 3-1-2006Marina ReadAinda não há avaliações

- Art - Collapse-Securitization - Subprime MeltdownDocumento56 páginasArt - Collapse-Securitization - Subprime MeltdownMarina ReadAinda não há avaliações

- California Civil Code 2924What Do You Owe and to Whom Do You Owe ItDocumento4 páginasCalifornia Civil Code 2924What Do You Owe and to Whom Do You Owe ItMarina Read100% (1)

- Commodity Exchange Act PDFDocumento2 páginasCommodity Exchange Act PDFAaronAinda não há avaliações

- Ministerial Decree No 401 of 2015 - EnglishDocumento3 páginasMinisterial Decree No 401 of 2015 - EnglishramodAinda não há avaliações

- People Vs Panganiban (Art 15), People Vs Sunga and People Vs Baello (Art 18), People Vs BinondoDocumento16 páginasPeople Vs Panganiban (Art 15), People Vs Sunga and People Vs Baello (Art 18), People Vs BinondomonchievaleraAinda não há avaliações

- 30 Students Sexually Abused by A TDSB TeacherDocumento4 páginas30 Students Sexually Abused by A TDSB Teachergrahamwishart123Ainda não há avaliações

- Nordic Asia Vs CADocumento1 páginaNordic Asia Vs CAShimi FortunaAinda não há avaliações

- Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Covanta Energy Philippine Holdings, Inc. DigestDocumento3 páginasCommissioner of Internal Revenue v. Covanta Energy Philippine Holdings, Inc. DigestCharmila Siplon100% (1)

- 05-10-11 Obama Continues Military Aid For Countries Recruting Child SoldiersDocumento2 páginas05-10-11 Obama Continues Military Aid For Countries Recruting Child SoldiersWilliam J GreenbergAinda não há avaliações

- Retributive TheoryDocumento18 páginasRetributive Theorynikita mukeshAinda não há avaliações

- 11 - Taguba V de Leon - PEREZDocumento2 páginas11 - Taguba V de Leon - PEREZPearl asdfAinda não há avaliações

- Correction Administration HistoryDocumento25 páginasCorrection Administration HistoryMelecio TatoyAinda não há avaliações

- Impotency As A Ground For Annulment - An Analysis Across Different Jurisdictions (Saumya Bazaz)Documento19 páginasImpotency As A Ground For Annulment - An Analysis Across Different Jurisdictions (Saumya Bazaz)sangitaAinda não há avaliações

- United States v. Thomas, 10th Cir. (2006)Documento6 páginasUnited States v. Thomas, 10th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Tenchavez Vs EscanoDocumento8 páginasTenchavez Vs EscanooabeljeanmoniqueAinda não há avaliações

- Cervantes Vs Auditor GeneralDocumento3 páginasCervantes Vs Auditor GeneralSylvia SecuyaAinda não há avaliações

- In Re Argosinio, 270 SCRA 26Documento1 páginaIn Re Argosinio, 270 SCRA 26Andrei Da JoseAinda não há avaliações

- 7610 - GRN 252267 EncinaresDocumento46 páginas7610 - GRN 252267 EncinaresJoAnneGallowayAinda não há avaliações

- Case Status - Search by Case NumberDocumento2 páginasCase Status - Search by Case NumberDr.Rajesh Kumar DubeyAinda não há avaliações

- Edo State marriage dissolution suitDocumento8 páginasEdo State marriage dissolution suitThomas BeahAinda não há avaliações

- Bengzon, Zarraga, Narciso, Cudala, Pecson & Bengson For Petitioners. Balgos & Perez For Intervening Petitioner. Eddie Tamondong and Antonio T. Tagaro For RespondentsDocumento19 páginasBengzon, Zarraga, Narciso, Cudala, Pecson & Bengson For Petitioners. Balgos & Perez For Intervening Petitioner. Eddie Tamondong and Antonio T. Tagaro For Respondentsgem baeAinda não há avaliações

- CATHOLIC VICAR APOSTOLIC Vs CA (G.R. No. 80294-95 September 21, 1988) Gancayco, J. FactsDocumento2 páginasCATHOLIC VICAR APOSTOLIC Vs CA (G.R. No. 80294-95 September 21, 1988) Gancayco, J. FactsCzar MartinezAinda não há avaliações

- Diksha Kumari Profile - NLU Jodhpur Law StudentDocumento2 páginasDiksha Kumari Profile - NLU Jodhpur Law StudentKaruna KumariAinda não há avaliações

- ZONINGDocumento1 páginaZONINGRoger JuanAinda não há avaliações

- Sample Trial Brief (Rules of Court)Documento4 páginasSample Trial Brief (Rules of Court)Wil MaeAinda não há avaliações

- Rehabilitation of Offenders Act - MOD Form 493 - DOC-43003 PDFDocumento5 páginasRehabilitation of Offenders Act - MOD Form 493 - DOC-43003 PDFNathan WatkinsAinda não há avaliações

- CyberbullyingDocumento2 páginasCyberbullyingPaula TenorioAinda não há avaliações

- Casent Realty v. PhilbankingDocumento4 páginasCasent Realty v. PhilbankingHezro Inciso CaandoyAinda não há avaliações

- Digest 01 - Orient Air Services Vs CA - OdtDocumento2 páginasDigest 01 - Orient Air Services Vs CA - OdtLiaa AquinoAinda não há avaliações

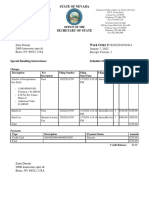

- Barbara K. Cegavske: Zane Durant 2000 Lonesome Spur DR Reno, NV 89521, USA January 7, 2022 Receipt Version: 1Documento10 páginasBarbara K. Cegavske: Zane Durant 2000 Lonesome Spur DR Reno, NV 89521, USA January 7, 2022 Receipt Version: 1fiqiAinda não há avaliações

- LEA-Police Comparative6Documento13 páginasLEA-Police Comparative6Michelle DuranAinda não há avaliações

- 05 SMCEU-PTGWO V SMPPEU-PDMP, G.R. No. 171153, September 12, 2007Documento10 páginas05 SMCEU-PTGWO V SMPPEU-PDMP, G.R. No. 171153, September 12, 2007Neriz Anne JavierAinda não há avaliações