Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Psychology of Punishment

Enviado por

FlexibleLeahDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Psychology of Punishment

Enviado por

FlexibleLeahDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Question: What Is Punishment?

Answer: Punishment is a term used in operant conditioning to refer to any change that occurs after a behavior that reduces the likelihood that that behavior will occur again in the future. While positive and negative reinforcement are used to increase behaviors, punishment is focused on reducing or eliminating unwanted behaviors. Punishment is often mistakenly confused with negative reinforcement. Remember, reinforcement always increases the chances that a behavior will occur and punishment always decreases the chances that a behavior will occur. Types of Punishment Behaviorist B. F. Skinner, the psychologist who first described operant conditioning, identified two different kinds of aversive stimuli that can be used as punishment. Positive Punishment: This type of punishment is also known as "punishment by application." Positive punishment involves presenting an aversive stimulus after a behavior as occurred. For example, when a student talks out of turn in the middle of class, the teacher might scold the child for interrupting her.

Negative Punishment: This type of punishment is also known as "punishment by removal." Negative punishment involves taking away a desirable stimulus after a behavior as occurred. For example, when the student from the previous example talks out of turn again, the teacher promptly tells the child that he will have to miss recess because of his behavior.

Is Punishment Effective? While punishment can be effective in some cases, you can probably think of a few examples of when punishment does not reduce a behavior. Prison is one example. After being sent to jail for a crime, people often continue committing crimes once they are released from prison. Why is it that punishment seems to work in some instances, but not in others? Researchers have found a number of factors that contribute to how effective punishment is in different situations. First, punishment is more likely to lead to a reduction in behavior if it immediately follows the behavior. Prison sentences often occur long after the crime has been committed, which may help explain why sending people to jail does not always lead to a reduction in criminal behavior. Second, punishment achieves greater results when it is consistently applied. It can be difficult to administer a punishment every single time a behavior occurs. For example, people often continue to drive over the speed limit even after receiving a speeding ticket. Why? Because the behavior is inconsistently punished. Punishment also has some notable drawbacks. First, any behavior changes that result from punishment are often temporary. "Punished behavior is likely to reappear after the punitive consequences are withdrawn," Skinner explained in his book About Behaviorism. Perhaps the greatest drawback is the fact that punishment does not actually offer any information about more appropriate or desired behaviors. While subjects might be learning to not perform certain actions, they are not really learning anything about what they should be doing. Another thing to consider about punishment is that it can have unintended and undesirable consequences. For example, while approximately 75 percent of parents in the United States report spanking their children on occasion, researchers have found that this type of physical punishment can lead to antisocial behavior, aggressiveness and delinquency among children. For this reason, Skinner and other psychologists suggest that any potential short-term gains from using punishment as a behavior modification tool need to be weighed again the potential long-term consequences. Question: What Is Positive Punishment? Answer: Positive punishment is a concept used in B. F. Skinner's theory of operant conditioning. The goal of punishment is to decrease the behavior that it follows. In the case of positive punishment, it involves presenting an unfavorable outcome or event following an undesirable behavior.

The concept of positive punishment can difficult to remember, especially because it seems like a contradiction. How can punishment be positive? The easiest way to remember this concept is to note that it involves an aversive stimulus that is added to the situation. For this reason, positive punishment is sometimes referred to as punishment by application. Examples of Positive Punishment

You wear your favorite baseball cap to class, but are reprimanded by your instructor for violating your school's dress code.

Because you're late to work one morning, you drive over the speed limit through a school zone. As a result, you get pulled over by a police officer and receive a ticket.

Your cell phone rings in the middle of a class lecture, and you are scolded by your teacher for not turning your phone off prior to class.

Can you identify the examples of positive punishment? The teacher reprimanding you for breaking the dress code, the officer issuing the speeding ticket and the teacher scolding you for not turning off your cell phone are all examples of positive punishment. They represent aversive stimuli that are meant to decrease the behavior that they follow. In all of the examples above, the positive punishment is purposely administered by another person. However, positive punishment can also occur as a natural consequence of a behavior. Touching a hot stove or a sharp object can cause painful injuries that serve as natural positive punishers for the behaviors. Spanking as Positive Punishment While positive punishment can be effective in some situations, B.F. Skinner noted that its use must be weighed against any potential negative effects. One of the best-known examples of positive punishment is spanking. Defined as striking a child across the buttocks with an open hand, this form of discipline is reportedly used by approximately 75 percent of parents in the United States. Some researchers have suggested that mild, occasional spanking is not harmful, especially when used in conjunction with other forms of discipline. However, in one large meta-analysis of previous research, psychologist Elizabeth Gershoff found that spanking was associated poor parent-child relationships as well as with increases in antisocial behavior, delinquency and aggressiveness. More recent studies that controlled for a variety of confounding variables also found similar results. Question: What Is Negative Punishment? Answer: Negative punishment is an important concept in B. F. Skinner's theory of operant conditioning. In behavioral psychology, the goal of punishment is to decrease the behavior that precedes it. In the case of negative punishment, it involves taking something good or desirable away in order to reduce the occurrence of a particular behavior. One of the easiest ways to remember this concept is to note that in behavioral terms, positive means adding something while negative means taking something away. For this reason, negative punishment is often referred to as punishment by removal. Examples of Negative Punishment

After getting in a fight with his sister over who gets to play with a new toy, the mother simply takes the toy away.

A teenage girl stays out for an hour past her curfew, so her parents ground her for a week.

A third-grade boy yells at another student during class, so his teacher takes away "good behavior" tokens that can be redeemed for prizes.

Can you identify the examples of negative punishment? Losing access to a toy, being grounded and losing reward tokens are all examples of negative punishment. In each case, something good is being taken away as a result of the individual's undesirable behavior. The Effects of Negative Punishment While negative punishment can be highly effective, Skinner and other researchers have suggested that a number of different factors can influence its success. Negative punishment is most effective when:

It immediately follows a response It is applied consistently

Consider this example: a teenage girl has a driver's license, but it does not allow her to drive at night. However, she drives at night several times a week without facing any consequences. One evening while she is driving to the mall with a friend, she is pulled over and issued a ticket. As a result, she receives a notice in the mail a week later informing her that her driver's privileges have been revoked for 30 days. Once she regains her license, she goes back to driving at night even though she has six more months before she is legally allowed to drive during evening and nighttime hours. As you might have guessed, losing her license is the negative punishment in this example. So why would she continue to engage in the behavior even though it led to a punishment? Because the punishment was inconsistently applied (she drove at night many times without facing punishment) and because the punishment was not applied immediately (her driving privileges were not revoked until a week after she was caught), negative punishment was not effective at curtailing her behavior. Another major problem with punishment is that while it might reduce the unwanted behavior, it does not really provide any information or instruction on more appropriate reactions. Skinner also noted that once the punishment is withdrawn, the behavior is very likely to return. COVER STORY

Rehabilitate or punish?

Psychologists are not only providing treatment to prisoners; they're also contributing to debate over the nature of prison itself. By ETIENNE BENSON Monitor Staff July/August 2003, Vol 34, No. 7 Print version: page 46

It's not a very good time to be a prisoner in the United States. Incarceration is not meant to be fun, of course. But a combination of strict sentencing guidelines, budget shortfalls and a punitive philosophy of corrections has made today's prisons much more unpleasant--and much less likely to rehabilitate their inhabitants--than in the past, many researchers say. What is the role for psychologists? First and foremost, they are providing mental health services to the prison population, which has rates of mental illness at least three times the national average. More broadly, they are contributing a growing body of scientific evidence to political and philosophical discussions about the purpose of imprisonment, says Craig Haney, PhD, a psychologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz. "Psychology as a discipline now has a tremendous amount of information about the origins of criminal behavior," says Haney. "I think that it is important for psychologists to bring that information to bear in the debate on what kind of crime control policies we, as a society, should follow." The punitive turn Until the mid-1970s, rehabilitation was a key part of U.S. prison policy. Prisoners were encouraged to develop occupational skills and to resolve psychological problems--such as substance abuse or aggression--that might interfere with their reintegration into society. Indeed, many inmates received court sentences that mandated treatment for such problems. Since then, however, rehabilitation has taken a back seat to a "get tough on crime" approach that sees punishment as prison's main function, says Haney. The approach has created explosive growth in the prison population, while having at most a modest effect on crime rates. As a result, the United States now has more than 2 million people in prisons or jails--the equivalent of one in every 142 U.S. residents--and another four to five million people on probation or parole. A higher percentage of the population is involved in the criminal justice system in the United States than in any other developed country. Many inmates have serious mental illnesses. Starting in the late 1950s and 1960s, new psychotropic drugs and the community health movement dramatically reduced the number of people in state mental hospitals. But in the 1980s, many of the mentally ill who had left mental institutions in the previous two decades began entering the criminal justice system. Today, somewhere between 15 and 20 percent of people in prison are mentally ill, according to U.S. Department of Justice estimates. "Prisons have really become, in many ways, the de facto mental health hospitals," says former prison psychologist Thomas Fagan, PhD. "But prisons weren't built to deal with mentally ill people; they were built to deal with criminals doing time." The mentally ill The plight of the mentally ill in prisons was virtually ignored for many years, but in the past decade many prison systems have realized--sometimes with prodding from the courts--that providing mental health care is a necessity, not a luxury, says Fagan. In many prison systems, psychologists are the primary mental health care providers, with psychiatrists contracted on a part-time basis. Psychologists provide services ranging from screening new inmates for mental illness to providing group therapy and crisis counseling. They also provide rehabilitative services that are useful even for prisoners without serious mental illnesses, says Fagan. For example, a psychologist might develop special programs for substance abusers or help prisoners prepare for the transition back to the community. But they often struggle to implement such programs while keeping up with their regular prison caseloads. "We're focused so much on the basic mental health services that there's not enough time or emphasis to devote to rehabilitative services," says Robert Morgan, PhD, a psychologist at Texas Tech University who has worked in federal and state prisons and studies treatment methods for inmates. Part of the problem is limited resources, says Morgan: There simply aren't enough mental health professionals in most prisons. Haney agrees: "Many psychologists in the criminal justice system have enormous caseloads; they're struggling not to be overwhelmed by the tide." Another constraint is the basic philosophical difference between psychology, which is rehabilitative at heart, and corrections, which is currently punishment-oriented. "Right now there's such a focus on punishment--most criminal justice or correctional systems are punitive in nature-that it's hard to develop effective rehabilitative programs," says Morgan. Relevant research To help shift the focus from punishment to rehabilitation, psychologists are doing research on the causes of crime and the psychological effects of incarceration.

In the 1970s, when major changes were being made to the U.S. prison system, psychologists had little hard data to contribute. But in the past 25 years, says Haney, they have generated a massive literature documenting the importance of child abuse, poverty, early exposure to substance abuse and other risk factors for criminal behavior. The findings suggest that individual-centered approaches to crime prevention need to be complemented by community-based approaches. Researchers have also found that the pessimistic "nothing works" attitude toward rehabilitation that helped justify punitive prison policies in the 1970s was overstated. When properly implemented, work programs, education and psychotherapy can ease prisoners' transitions to the free world, says Haney. Finally, researchers have demonstrated the power of the prison environment to shape behavior, often to the detriment of both prisoners and prison workers. The Stanford Prison Experiment, which Haney co-authored in 1973 with Stanford University psychologist and APA Past-president Philip G. Zimbardo, PhD, is one example. It showed that psychologically healthy individuals could become sadistic or depressed when placed in a prison-like environment. More recently, Haney has been studying so-called "supermax" prisons--high-security units in which prisoners spend as many as 23 hours per day in solitary confinement for years at a time. Haney's research has shown that many prisoners in supermax units experience extremely high levels of anxiety and other negative emotions. When released--often without any "decompression" period in lower-security facilities--they have few of the social or occupational skills necessary to succeed in the outside world. Nonetheless, supermax facilities have become increasingly common over the past five to ten years. "This is what prison systems do under emergency circumstances--they move to punitive social control mechanisms," explains Haney. "[But] it's a very short-term solution, and one that may do more long-term damage both to the system and to the individuals than it solves."

Você também pode gostar

- From Chastity Requirement To Sexuality License: Sexual Consent and A New Rape Shield LawDocumento146 páginasFrom Chastity Requirement To Sexuality License: Sexual Consent and A New Rape Shield Lawmary eng100% (1)

- Custodial TortureDocumento13 páginasCustodial Torturewhat78406Ainda não há avaliações

- Tugas TranslateDocumento3 páginasTugas TranslateAgus R. SitumeangAinda não há avaliações

- Pavlov's Classical Conditioning TheoryDocumento10 páginasPavlov's Classical Conditioning TheoryMir AqibAinda não há avaliações

- Positive Punishment in Operant ConditioningDocumento7 páginasPositive Punishment in Operant Conditioningmahrukh khanAinda não há avaliações

- Theories of Learning: Classical Conditioning, Operant Conditioning & Social LearningDocumento7 páginasTheories of Learning: Classical Conditioning, Operant Conditioning & Social LearningArron AblogAinda não há avaliações

- Skinner TheoryDocumento9 páginasSkinner Theorygabriel chinechenduAinda não há avaliações

- Why punishment works - focusing on loss aversion and building trustDocumento2 páginasWhy punishment works - focusing on loss aversion and building trustBen JefferiesAinda não há avaliações

- 12 Examples of Positive PunishmentDocumento11 páginas12 Examples of Positive PunishmentМарина Трубникова ПинкусAinda não há avaliações

- Operant Conditioning PaperDocumento8 páginasOperant Conditioning PaperSalma Ahmed100% (4)

- Operant ConditioningDocumento3 páginasOperant ConditioningMark neil a. GalutAinda não há avaliações

- Pyschology AssignmentDocumento5 páginasPyschology AssignmentGeoffreyAinda não há avaliações

- Speaking Test Step 2Documento3 páginasSpeaking Test Step 2Nabila TharifahAinda não há avaliações

- Skinner EssayDocumento3 páginasSkinner EssayMisheck NkosiAinda não há avaliações

- Physiology Quiz AnswersDocumento3 páginasPhysiology Quiz AnswersGhulam AbbasAinda não há avaliações

- How operant conditioning shapes behavior through rewards and punishmentsDocumento5 páginasHow operant conditioning shapes behavior through rewards and punishmentsmadhu bhartiAinda não há avaliações

- Skinner-Behavioral Analysis Related Research - ReportDocumento3 páginasSkinner-Behavioral Analysis Related Research - ReportPatricia Nolan LopezAinda não há avaliações

- Operant Conditioning (Sometimes Referred To AsDocumento7 páginasOperant Conditioning (Sometimes Referred To AsJhon LarioqueAinda não há avaliações

- ASSIGNMENTDocumento5 páginasASSIGNMENTCHIOMA AGUHAinda não há avaliações

- Description of The Strategy: Positive PunishmentDocumento5 páginasDescription of The Strategy: Positive Punishmentiulia9gavrisAinda não há avaliações

- What Is Operant Conditioning - Definition and ExamplesDocumento10 páginasWhat Is Operant Conditioning - Definition and ExamplesAlekhya DhageAinda não há avaliações

- Treatment of Criminal OffendersDocumento7 páginasTreatment of Criminal OffendersRukhsarAinda não há avaliações

- Jennifer's Operant Conditioning AnalysisDocumento5 páginasJennifer's Operant Conditioning AnalysisJennifer BotheloAinda não há avaliações

- Increase Productivity by Giving Reward and PunishmentDocumento5 páginasIncrease Productivity by Giving Reward and PunishmentGilang Fardes PratamaAinda não há avaliações

- Psy Essay Negative ReinforcementDocumento4 páginasPsy Essay Negative ReinforcementjemamustafaAinda não há avaliações

- How To Change Children's Behavior (Quickly)No EverandHow To Change Children's Behavior (Quickly)Nota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Behavioural ApproachDocumento61 páginasBehavioural ApproachJK Group LtdAinda não há avaliações

- Correctional CounselingDocumento6 páginasCorrectional CounselingJoseph GathuaAinda não há avaliações

- Social Psychology EssaysDocumento4 páginasSocial Psychology EssaysKavinayaa MohanAinda não há avaliações

- Contributions To Psychology and HumanitiesDocumento2 páginasContributions To Psychology and HumanitiesJessie BelarminoAinda não há avaliações

- Learning Theories Imp Mat-1Documento32 páginasLearning Theories Imp Mat-1Tabish MirAinda não há avaliações

- PSY Chapter 5 Short AnswerDocumento2 páginasPSY Chapter 5 Short AnswerMichelleAinda não há avaliações

- Task4 LAD - Apura Roze Angela MAED ELTDocumento13 páginasTask4 LAD - Apura Roze Angela MAED ELTFarrah Mie Felias-OfilandaAinda não há avaliações

- Newsletter Salam Atwi Ahmad Hachem and Hussein BdewiDocumento3 páginasNewsletter Salam Atwi Ahmad Hachem and Hussein Bdewiapi-344653129Ainda não há avaliações

- UntitledDocumento2 páginasUntitledMichelleAinda não há avaliações

- Delos Santos Roselle DDocumento3 páginasDelos Santos Roselle DRoselle Delos SantosAinda não há avaliações

- MPCL007-1st Yr En.2101329657 - Sekhar VuswabDocumento22 páginasMPCL007-1st Yr En.2101329657 - Sekhar VuswabSekhar ViswabAinda não há avaliações

- Thesis Statement On Corporal Punishment in SchoolsDocumento8 páginasThesis Statement On Corporal Punishment in Schoolsdnr3krf8100% (2)

- Corporal Punishment: Ryeu Angelo SJ. Pike Grade 10 - St. James The GreaterDocumento2 páginasCorporal Punishment: Ryeu Angelo SJ. Pike Grade 10 - St. James The GreaterRichie PikeAinda não há avaliações

- Behaviorism by Skinner and OthersDocumento6 páginasBehaviorism by Skinner and OthersAnonymous On831wJKlsAinda não há avaliações

- Similarities and DifferencesDocumento7 páginasSimilarities and DifferencesEnniah MlalaziAinda não há avaliações

- Mod 1 - ABA - Dec Und Beh-1Documento3 páginasMod 1 - ABA - Dec Und Beh-1Dhen LoyolaAinda não há avaliações

- Psychological Learning TheoriesDocumento75 páginasPsychological Learning TheoriesVivian Chen100% (1)

- The Perceived Effects of Physical Punishment To TeenagersDocumento23 páginasThe Perceived Effects of Physical Punishment To TeenagersClare VenturaAinda não há avaliações

- Is Spanking Discipline or ViolenceDocumento2 páginasIs Spanking Discipline or ViolenceYvanna MabituinAinda não há avaliações

- Shaping BehaviorDocumento2 páginasShaping BehaviorAnirban HalderAinda não há avaliações

- ReinforcementDocumento16 páginasReinforcementharinAinda não há avaliações

- IntroDocumento10 páginasIntroAnthony Wilfred BasmayorAinda não há avaliações

- The House Support Corporal Punishment in SchoolsDocumento3 páginasThe House Support Corporal Punishment in Schools席子音楠Ainda não há avaliações

- Critical Reading ExerciseDocumento8 páginasCritical Reading ExerciseQuang Hoàng NghĩaAinda não há avaliações

- Formation and Change of Attitudes TITLE How Attitudes Develop and Are ModifiedDocumento5 páginasFormation and Change of Attitudes TITLE How Attitudes Develop and Are ModifiedSooraj.rajendra Prasad100% (1)

- Punishment and RewardDocumento7 páginasPunishment and RewardRevamsh PopuriAinda não há avaliações

- CrimEd 603 (Psychological Factors of Crime) FinalDocumento38 páginasCrimEd 603 (Psychological Factors of Crime) FinalJohnpatrick DejesusAinda não há avaliações

- Operant Conditioning and Social Cognitive TheoryDocumento2 páginasOperant Conditioning and Social Cognitive TheoryIryna DribkoAinda não há avaliações

- Rewards & Punishment: - John HoltDocumento8 páginasRewards & Punishment: - John HoltGrace Amparado UrbanoAinda não há avaliações

- Operant Conditioning and Social Learning TheoryDocumento2 páginasOperant Conditioning and Social Learning TheorybookwormdivaAinda não há avaliações

- Criminal Behavior and Learning TheoryDocumento8 páginasCriminal Behavior and Learning TheoryRobert BataraAinda não há avaliações

- CRI 184 - Module 5 Supplemental NotesDocumento7 páginasCRI 184 - Module 5 Supplemental NotesSamchiAinda não há avaliações

- Behavioral TheoryDocumento59 páginasBehavioral TheoryJK Group LtdAinda não há avaliações

- Juvenile Justice in The Philippines - A Personal Experience (Abstract) Marianne Murdoch-Verwijs, LLM (Free University, Amsterdam)Documento11 páginasJuvenile Justice in The Philippines - A Personal Experience (Abstract) Marianne Murdoch-Verwijs, LLM (Free University, Amsterdam)FlexibleLeahAinda não há avaliações

- Active and Passive OverviewDocumento2 páginasActive and Passive Overviewhwa5181Ainda não há avaliações

- COMPADocumento6 páginasCOMPAFlexibleLeahAinda não há avaliações

- K TrafficDocumento3 páginasK TrafficFlexibleLeahAinda não há avaliações

- Forensic Science - Hair Analysis I ADocumento39 páginasForensic Science - Hair Analysis I AFlexibleLeah100% (1)

- Pig TestDocumento1 páginaPig TestFlexibleLeahAinda não há avaliações

- P RisidintiDocumento65 páginasP RisidintiFlexibleLeahAinda não há avaliações

- Final Report For PrintDocumento11 páginasFinal Report For PrintFlexibleLeahAinda não há avaliações

- KEY FinalsDocumento4 páginasKEY FinalsFlexibleLeahAinda não há avaliações

- PDAFDocumento29 páginasPDAFFlexibleLeahAinda não há avaliações

- C RIMINOLOGYDocumento2 páginasC RIMINOLOGYFlexibleLeahAinda não há avaliações

- 456Documento4 páginas456FlexibleLeahAinda não há avaliações

- Ateneo 2007 Criminal ProcedureDocumento69 páginasAteneo 2007 Criminal ProcedureJingJing Romero98% (55)

- AustraliaDocumento1 páginaAustraliaFlexibleLeahAinda não há avaliações

- Test Procedure in Polygraph ExaminationDocumento15 páginasTest Procedure in Polygraph Examinationmyphone314850% (6)

- Ate Leah HahaDocumento4 páginasAte Leah HahaFlexibleLeahAinda não há avaliações

- Revised Ortega Lecture Notes IDocumento105 páginasRevised Ortega Lecture Notes IFlexibleLeahAinda não há avaliações

- 3G3EV Installation ManualDocumento55 páginas3G3EV Installation ManualHajrudin SinanovićAinda não há avaliações

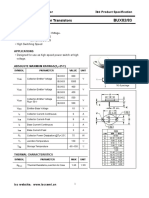

- Isc BUX82/83: Isc Silicon NPN Power TransistorsDocumento2 páginasIsc BUX82/83: Isc Silicon NPN Power TransistorsCarlos HCAinda não há avaliações

- ICAEW Professional Level Business Planning - Taxation Question & Answer Bank March 2016 To March 2020Documento382 páginasICAEW Professional Level Business Planning - Taxation Question & Answer Bank March 2016 To March 2020Optimal Management SolutionAinda não há avaliações

- Flowers From 1970Documento93 páginasFlowers From 1970isla62% (21)

- 2018-06-21 Calvert County TimesDocumento24 páginas2018-06-21 Calvert County TimesSouthern Maryland OnlineAinda não há avaliações

- Aerobic BodybuilderDocumento38 páginasAerobic Bodybuildercf strength80% (5)

- Cherry Circle Room Main MenuDocumento8 páginasCherry Circle Room Main MenuAshok SelvamAinda não há avaliações

- CIVICUS Monitoring October 2020 BriefDocumento8 páginasCIVICUS Monitoring October 2020 BriefRapplerAinda não há avaliações

- Payslip 11 2020Documento1 páginaPayslip 11 2020Sk Sameer100% (1)

- MR Safe Conditional PDFDocumento4 páginasMR Safe Conditional PDFAKSAinda não há avaliações

- Elo TecDocumento2 páginasElo TecMimi MimiAinda não há avaliações

- Barrioquinto vs. FernandezDocumento2 páginasBarrioquinto vs. FernandezIrene RamiloAinda não há avaliações

- General Biology 1: Quarter 1 - Module - : Title: Cell CycleDocumento27 páginasGeneral Biology 1: Quarter 1 - Module - : Title: Cell CycleRea A. Bilan0% (1)

- Test NovDocumento4 páginasTest NovKatherine GonzálezAinda não há avaliações

- Sensation As If by Roberts PDFDocumento369 páginasSensation As If by Roberts PDFNauman Khan100% (1)

- Margaret Sanger's Role in Population Control AgendaDocumento11 páginasMargaret Sanger's Role in Population Control AgendaBlackShadowSnoopy100% (1)

- The Dolphin: by Sergio Bambarén. Maritza - Jhunior - Cynthia - Carlos - AlexDocumento10 páginasThe Dolphin: by Sergio Bambarén. Maritza - Jhunior - Cynthia - Carlos - AlexAlexandra FlorAinda não há avaliações

- Brer Rabbit Stories - 2015Documento17 páginasBrer Rabbit Stories - 2015Ethan Philip100% (1)

- How To Make Waffles - Recipes - Waffle RecipeDocumento5 páginasHow To Make Waffles - Recipes - Waffle RecipeJug_HustlerAinda não há avaliações

- PEPSICODocumento35 páginasPEPSICOAnkit PandeyAinda não há avaliações

- Commissioning Requirements Section 01810Documento28 páginasCommissioning Requirements Section 01810tivesterAinda não há avaliações

- IEPF Authority (Recruitment, Salary and Other Terms and Conditions of Service Officers and Other Employees), Rules 2016Documento10 páginasIEPF Authority (Recruitment, Salary and Other Terms and Conditions of Service Officers and Other Employees), Rules 2016Latest Laws TeamAinda não há avaliações

- Ch-19 Gas Welding, Gas Cutting & Arc WeldingDocumento30 páginasCh-19 Gas Welding, Gas Cutting & Arc WeldingJAYANT KUMARAinda não há avaliações

- KeirseyDocumento28 páginasKeirseyapi-525703700Ainda não há avaliações

- ParaphrasingDocumento20 páginasParaphrasingPlocios JannAinda não há avaliações

- Power Quality SolutionDocumento40 páginasPower Quality Solutionshankar ammantryAinda não há avaliações

- Handbook of Heterogeneous Catalytic Hydrogenation For Organic Synthesis 2001 2Documento747 páginasHandbook of Heterogeneous Catalytic Hydrogenation For Organic Synthesis 2001 2Purna Bhavnari75% (4)

- The Basics of Profit Planning for Your Small BusinessDocumento1 páginaThe Basics of Profit Planning for Your Small BusinessRodj Eli Mikael Viernes-IncognitoAinda não há avaliações

- Liveability Index 2022Documento13 páginasLiveability Index 2022Jigga mannAinda não há avaliações

- Shoplifting's Impact on Consumer BehaviorDocumento3 páginasShoplifting's Impact on Consumer BehaviorJerico M. MagponAinda não há avaliações