Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Finance Islamique - J Banking Regul 2009

Enviado por

gladio67Descrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Finance Islamique - J Banking Regul 2009

Enviado por

gladio67Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Original Article

Islamophobia or an important weapon? An analysis of the US financial war on terrorism

Nicholas Ryder

is Reader in Financial Services Law at Bristol law School, University of the West of England, Bristol. His research interests concentrate on financial crime and financial services regulation. He is Head of the Commercial Law Research Unit, and currently teaches Commercial Law and International Financial Crime.

Umut Turksen

is Senior Lecturer at Bristol Law School, University of the West of England, Bristol. He has extensive experience of research, consultancy and evaluation in the fields of legal procedure and international trade law. He teaches Public International Law, European Union Law and World Trade Organisation Law. Correspondence: Nicholas Ryder, Commercial Law Research Unit, Bristol Law School, University of the West of England, Bristol, Frenchay Campus, Coldharbour Lane, Bristol BS16 1QY, UK E-mail: Nicholas.Ryder@uwe.ac

ABSTRACT This article considers the impact of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 (9/11) on the legislative and policy response by the United States towards terrorist financing. This article is divided into three parts. Part 1 considers the alleged association between Islamic banking systems and terrorist finance. The second part of the article critically considers the ability of the US authorities to freeze the assets of organisations who are suspected of financing terrorism by virtue of Presidential Executive Order 13 224. The final part of the article considers the reporting requirements imposed by the Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act 2001 (USA PATRIOT Act 2001). The third part also highlights some provisions and practices that raise the spectre of racial profiling in the United States, and critiques the fairness and success of such measures imposed on particular group of persons. The objective is not to provide a comprehensive analysis of the laws and policies, but to emphasise areas that have not yet been subject to sufficient scrutiny from the perspective of success and equality of the application of the law.

Journal of Banking Regulation (2009) 10, 307320. doi:10.1057/jbr.2009.10

SOURCES OF TERRORIST FINANCE

Terrorist finance was adopted by the United Nations (UN) in its Declaration to Eliminate International Terrorism in 1994.1 The International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism defines funds for terrorism to include assets of every kind, whether tangible or intangible, movable or immovable, however acquired, and legal documents or instruments in any form.2 Before the terrorist

attacks of 9/11, the international communitys efforts towards the reduction of financial crime focused mainly on the prevention of money laundering, the illegal drugs trade and fraud. The terrorist attacks resulted in a significant alteration in both political and legislative attitudes towards terrorist financing. Subsequently, the United States instigated a financial war on terrorism, a term originally coined by President Clinton following the bombings of the US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania.3

r 2009 Palgrave Macmillan 1745-6452 Journal of Banking Regulation www.palgrave-journals.com/jbr/

Vol. 10, 4, 307320

Ryder and Turksen

Terrorists have traditionally relied upon two sources of funding: state and private sponsors.4 State sponsorship of terrorism is where national governments provide ideological, logistical and financial support to terrorist organisations.5 The United States has designated four countries as state sponsors of terrorism: Sudan, Syria, Iran and Cuba.6 The true extent of statesponsored terrorism is impossible to determine, yet it has been suggested that state sponsors do provide substantial support.5 There is evidence, however, that the extent of state-sponsored terrorism has declined,7 and it is now more likely that terrorists will receive funding from private sponsors or donors.8 Such assertion ties in with the 9/11 Commission Report (9/11 Commission), which concluded that al-Qaeda has relied on a core group of financial facilitators who raised money from a variety of private donors.9 The decline in statesponsored terrorism has forced terrorist organisations to become self-funding,10 and as a result they are forced to deploy several mechanisms to raise funds.11 Therefore, somewhat unsurprisingly, there are an abundant number of sources of funding available to terrorists.12 This means that they are able to manipulate an expanding array of tools to shield their wealth, without regard to international borders.13 Terrorists are also utilising new electronic technologies to transfer money over the internet to conceal their true origin.14 The Financial Action Task Force reported that the legal sources used to support terrorism are extensive. Terrorists have also acquired funding through traditional criminal activities, including benefit and credit card fraud, identity theft, the sale of counterfeit goods and drug trafficking.15

Hawala A terrorists financial tool?

As a direct result of 9/11, the international community has targeted alternative or nonremittance underground banking systems. Underground banking is a phrase that has been used to describe informal banking systems that are seen to be secretive and mysterious,16,17

or a method of banking that takes place outside the regulated financial services sector. Rider18 took the view that underground banking systems have developed to a level in some societies where they rival the conventional banking system in terms of efficiency and capability. One such method is the hawala system, which has existed for centuries throughout the world.19 It is said that the origins of the hawala system can be traced as far back as 5000 BC.20 While others assert that it was founded as a legal concept of Islamic law in 1327.21 Hawala has several different interpretations, including assignment, change, transform or promissory note.22 The hawala system is an informal financial network based on trust, which means that any funds transferred are difficult to detect.23 This is largely because the hawala financial network makes no use of any written record.19 The World Bank claims that the amount of money remitted via the hawala system to developing countries alone from the United States is US$80 billion.19 The total number of hawala transfers amount to two trillion dollars, but this figure only accounts for approximately 2 per cent of international financial transactions.24 Why is the hawala system so popular? It has been suggested that one reason is that many people distrust the banking system.25 Furthermore, the hawala system is efficient and quicker than the traditional banking system.26 Despite its legitimate users, the International Monetary Fund warned that the hawala system is potentially open to abuse of financial crime.27 It has been suggested that the hawala system has been used for criminal activities,19 and that it plays a central role in the shadow economy [it is] the optimal financial system for terrorists.28 Schramm and Taube21 claimed that the undocumented system is well prepared to elude surveillance and regulation by anti-terrorist groups. As soon as the phrase hawala was mentioned following 9/11, politicians, law enforcement agencies and the media declared it as a financial tool of terrorism.29 This is deceptive because until the financial war on

308

r 2009 Palgrave Macmillan 1745-6452

Journal of Banking Regulation

Vol. 10, 4, 307320

Islamophobia or an important weapon?

terrorism, these systems were legitimate and were heavily advertised.30 It has been reported, although narrowly, that al-Qaeda has regularly used this system to fund its operation.31 However, there is no conclusive evidence that al-Qaeda used the hawala system to fund 9/11.32 One of the problems facing the legislative approach to the prevention of terrorist finances is that alternative remittance systems, such as hawala, are difficult to regulate, and that previous attempts to regulate them have been ineffective.33 Rider argues that one of the main reasons for the inadequate level of regulation is that the law and enforcement policies which have been fashioned to address money laundering through conventional banking systems are of little practical relevance in the case of such underground systems.34 Several countries have attempted to regulate and even ban this ancient method of money transmission.21 Any attempt to legislate against the hawala system by imposing reporting or registration requirements might limit some illegal activities, but their overall effectiveness must be questioned.19 For example, because the hawala system is secretive and it lacks any paper record of the transaction it bedevils financial auditors and law enforcement officials. It poses considerable challenges to existing legal and regulatory regimes on money laundering and terrorist financing.27 For example, any attempt to regulate the hawala system would place an increased secretarial burden on financial regulatory agencies that are already struggling to reduce money laundering.35 The secretive nature of the hawala system makes it impossible to regulate, and gives rise to potential abuse by terrorists. Legislators and financial regulatory bodies have targeted the hawala system because of its alleged links to terrorism following the attacks of 9/11. If this system is to be effectively regulated, governments need to fully understand non-remittance systems and why millions of people use them. Despite its alleged association with terrorism, the hawala system is a lawful financial system,19 and consequently should be incorporated into the existing financial system.

THE LEGISLATIVE RESPONSE

These terrorist attacks set in motion a new and direct legislative approach towards terrorist funding at an international level.36 UN Security Council Resolution 1373 imposed four obligations. First, it requires states to thwart and control the financing of terrorism.37 Second, it criminalises the collection of terrorist funds in states territory.38 Third, it freezes funds, financial assets and economic resources of people who commit or try to commit acts of terrorism.39 Fourth, it prevents any nationals from within their territories from providing funds, financial assets and economic resources to people who seek to commit acts of terrorism.40 Resolution 1373 forms the basis of the international effort to counter terrorist finance,41 and it represents a powerful tool to leverage co-operation by all states on financing issues.41 Consequently, we have witnessed a reduction in state-sponsored terrorism. However, the Resolution can be criticised because it provides the individuals and organisations who have been accused of supporting terrorism with no opportunity within the UN to challenge the listing by the UN Counter Terrorism Committee.41 As a result of Resolution 1373, we are left with a patchwork of domestic, bilateral, and regional efforts that at best work in parallel but not complimentary fashion, and at worst work at cross-purposes.42 The legislative policy of the United Sates is contained in Presidential Executive Order 13 224 and the USA PATRIOT Act 2001.43 This Order sought to block and freeze the assets of terrorists and people who provided [and freeze] all assets and interests in property of certain terrorists and individuals who assist them. The US government has attempted to deny terrorists admittance to the international financial system and limit their ability to raise funds. There are three important aspects of this law.44 First, it covers global terrorism. Second, it expands the class of targeted groups to include those who are associated with designated terrorist groups.45 Third, it clarifies the ability of the United States to freeze and block

r 2009 Palgrave Macmillan 1745-6452

Journal of Banking Regulation

Vol. 10, 4, 307320

309

Ryder and Turksen

terrorist assets abroad. The next part of the article considers the impact of the second part of the Executive Order.

ASSET FREEZING

In September 2001, the US government began to freeze assets and bank accounts across the globe that they believed to assist terrorists and their operations.46 Its ability to freeze the assets of suspected or known terrorists is administered by the Office of Foreign Assets Control, or OFAC.47 As a result of the Executive Order, a number of corporations and individuals were designated as either a terrorist group or a foreign terrorist organisation for the purposes of freezing assets.48 The Treasury Department reported that as a result of Executive Order 13 224, over 150 terrorist-related accounts have been blocked in the United States, more than 400 individuals and entities have been designated terrorists or terrorists supporters, and approximately 40 charities that were transferring money to al-Qaeda, HAMAS and other terrorist groups have been designated and denied access to the US financial system.49 Furthermore, 1439 suspected terrorist accounts have been frozen, containing $135 million in assets.50 This part of the policy has produced mixed results.51 The number of suspected accounts and assets frozen represents a small fraction of the funds available to terrorists.52 Seldon53 warned that despite laudable goals, many asset seizures have undermined the faith of foreign investors in the US, and he also cited several failed prosecutions ofindividuals and organisations who also had their assets frozen following 9/11.54 One of the most controversial aspects of the US policy is its attitude towards Islamic charities. The authorities assert that there is increasing evidence that terrorists are partly financed by followers who donate money to Islamic charities, which is then transferred to terrorists.55 It has been estimated that al-Qaeda funds a large proportion of its operations through charitable donations. Therefore, charities

could be the second largest source of funding for al-Qaeda.56 However, any accurate evidence of charitable donations being used by terrorist groups is extremely rare.57 One of the first US Islamic charities to be classified as a terrorist organisation was the Holy Land Foundation in Texas.58,59 Since this announcement, a large number of other Muslim charities based in the United States have also been given an identical classification, and had their assets frozen.60 Irrespective of the apparent success and robustness with which the US authorities have targeted this apparent source of terrorist finance, it has faced many problems in actually proving many of the terrorist-related charges. Ruff61 has accused the US government of being overzealous and using exaggerated facts to gain media attention, thus making the freezing of assets during a pending investigation particularly suspect. Engel62 has also criticised this part of the anti-terrorist finance policy because the freezing of their assets has confiscated the good-faith donations solicited fraudulently from Muslim-Americans. In a large number of these cases, the charges were dropped or the prosecutors were unable to prove any connections with terrorist activities.63 This part of the policy is contentious because the evidence linking each of these organisations to the funding of terrorism was in the hands of the US prosecutors, who withheld it from the media, the public and to the charities themselves who were directly accused of funding terrorism.64 The US governments policy towards the freezing of suspected terrorist assets is a short-term solution to a long-term problem. It is an ineffective response to the funding of international terrorism because of the vast array of sources of funding available. The US government is clearly motivated by a political desire to appease the public and make it look like they will actually catch terrorists rather than sit idly.

REPORTING REQUIREMENTS

An important part of the policy towards the prevention of terrorist finance is the reporting

310

r 2009 Palgrave Macmillan 1745-6452

Journal of Banking Regulation

Vol. 10, 4, 307320

Islamophobia or an important weapon?

requirements placed on financial and credit institutions. The USA PATRIOT Act 2001 contained a comprehensive package of provisions that aimed to bolster the anti-terrorist financing regulatory regimes.65 Title III of the Act increases the reporting obligations and permits the Secretary of the Treasury to impose additional requirements on financial institutions.66 The Act introduced a series of regulations that are aimed at detecting terrorist finance before its introduction to the financial system.67 Under the Act, financial institutions are required to file a suspicious activity report (SAR) to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network or FinCEN.68 The reporting requirements impose administrative burdens on financial institutions that already had to comply with reporting requirements under the Bank Secrecy Act 1970.69 The USA PATRIOT Act 2001 has already led to an increased level of record keeping, report filing, and internal policing requirements.70 In November 2008, FinCEN published its SAR, which yielded some very interesting statistics. For example, the reported instances of suspected terrorist financing decreased by 28 per cent in the half of 2008. Yet there was an increase in suspected mortgage loan and wire transfer fraud.71 Nonetheless, the total number of SARs filed with FinCEN continues to increase at a steady rate. The imposition of mandatory reporting requirements was inevitable following the attacks of 9/11 because one of the terrorists had been the subject of a SAR in September 2000. It is questionable, however, whether the filing of a SAR following these transactions [to fund 9/11] would have made a difference.72 It is, therefore, possible to argue that the measures introduced by the USA PATRIOT Act 2001 may prove to be counterproductive.73 The imposition of more regulations has generated depressingly few tangible results.74 Increasing the level of reporting requirements on financial institutions will not prevent terrorist finance. This part of the policy is predictable because a large percentage of the monies used to fund 9/11 were wired to the accounts of the

terrorists directly through the US formal banking system.

PROFILING OF PERSONS AND ITS SUCCESS

They [non-US terrorist suspects] dont deserve the same guarantees and safeguards that would be used for an American citizen going through the normal judicial process.75 Can this part of the US policy described as islamophobic and/or discriminatory? The history of discrimination in the United States is controversial and extremely well documented and is beyond the scope of this article. Yet, since 9/11, the level of discrimination against Muslims in the United States has increased. In fact, some authors argue that these measures amount to a racial profiling,76 and are not allowed under anti-discrimination laws.77 After the terrorist attacks, the US government and its agencies felt that it was important to disrespect the long-established need to obtain probable cause before investigating a persons private affairs. Lee78 noted that in an attempt to flush out the funds of foreign nationals who financed terrorism y the Fourth Amendment was trumped. The Forth Amendment of the US Constitution provides the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized. The USA PATRIOT Act 2001 has been used by US authorities in a vain attempt to generate a master list of evil doers and their possible activities.78 If a person enters into a legitimate transaction that has been designated by the financial institution as suspicious or high risk, the business deal will be the subject of a SAR or a currency transaction report. Whether or

r 2009 Palgrave Macmillan 1745-6452

Journal of Banking Regulation

Vol. 10, 4, 307320

311

Ryder and Turksen

not these provisions are an example of Islamophobia or amount to racial profiling depends upon the interpretation of the phrase suspicion and the employees of financial institutions. Lee contends that if you are Black or Brown and living in America, you have probably been stopped and questioned by the police at some moment in your life y since the USA PATRIOT Act 2001 y if you are Brown, Muslim, national of Middle Eastern descent, look Muslim or of Middle Eastern Ethnicity that questioning may happen in a bank.79 Lee adds that the USA PATRIOT Act 2001 put banks in the business of practicing selective enforcement and racial profiling with every transaction, every hour of every business day.80 Part of the problem lies with the people who report a suspicious transaction and the grounds they base their decision on. FinCEN have issued guidelines that provide guidance for employees of financial institutions as to what should initiate the completion of an SAR. This includes, for example, the use of a business account that would not normally generate the volume of wire transfer activity, a beneficiary account in a problematic country, currency exchange from various countries in the Middle East and business account activity conducted by nationals in countries associated with terrorist activity. The privacy of account holders versus the authorities ability to obtain information has been scrutinised by the US Supreme Court on several occasions. While the US Supreme Court has condemned racial stereotyping,81 it has decided that the reporting obligations imposed by the BSA 1970 do not infringe the Fourth Amendment of the US Constitution.82 The appropriateness of racial profiling in concurrence with the SARs regime must be criticised because its effectiveness is dependent upon the employees of the financial institutions who are subject to the reporting requirements of the USA PATRIOT Act 2001. Whether or not a person is to be the subject of a SAR will wholly depend upon the judgment of the employee in applying the firms counter

terrorist finance policy. Is an employee able to understand and detect whether a transaction or series of transactions is being used to fund acts of terrorism? This is extremely unlikely given the lack of understanding of the funding of terrorism shown by the US Administration and the general ineffectiveness of the USA PATRIOT Act 2001. This point is noted by Lee, who took the view that Profiling has not enhanced national security; not a single arrest, not a single dollar found by a SAR or CTR report since the aftermath of 9/11, has been traced to a terrorist act. Moreover, the Treasury Department is now so overwhelmed by the sheer number of SARs and CTRs, if there were evidence of terrorism uncovered by these devices, it would be months before the particular SAR would be identified.78 Before September 11, 2001, only 21 SARs described suspicious activity related to terrorism or terrorist organisations.83 Between 12 September 2001 and 31 March 2002, more than 1600 SARs were filed by 225 financial institutions that contained references to terrorism or terrorist groups. The amounts of suspicious financial activities ranged from $14 to $300 million.84 The suspicious wire transfers occurred predominantly to or from Middle-Eastern countries. But other countries with predominantly Muslim populations such as Pakistan, Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines were also identified in connection with suspicious wire transfer activity. Of course, the selection of Middle Eastern ethnicity and Muslims as terrorist suspects does not automatically amount to a racial profiling if the investigation is based on evidence of particular conduct, as well as characteristics of individuals such as race, national origin, eye colour and height. However, if any counter terrorism measure or decision is based on the belief that members of a particular group are more likely to commit the crime under

312

r 2009 Palgrave Macmillan 1745-6452

Journal of Banking Regulation

Vol. 10, 4, 307320

Islamophobia or an important weapon?

investigation than are members of other groups, such as a member of the Irish Republican Army or the Basque group ETA, then one could start establishing the hallmark of racial profiling based on stereotypes.85 Gross and Livingston86 have asserted that it is not racial profiling for an officer to question, stop, search, arrest, or otherwise investigate a person because his race or ethnicity matches information about a perpetrator of a specific crime that the officer is investigating. Although the courts have held that racial component of any evidence and/or suspect description on its own is not sufficient enough to justify a stop and search, investigate and arrest, no court decision has established that reliance on suspect description is discriminatory or identifying characteristics cannot include race or ethnicity.87 For example, it was asserted that y common sense dictates when determining whom to approach as a suspect of criminal wrongdoing, a police officer may legitimately consider race as a factor if descriptions of the perpetrator known to the officer include race.88 Academia also agrees that suspect description reliance is permissible under the Equality Protection Clause,89 as it is not racially discriminatory and relies on particular characteristics of a specific perpetrator.90 Some academics support the use of racial profiling,91 whereas some are totally against it,92 or argue that it is unnecessary.93 The Supreme Courts view has been that [at] the very least, the Equal Protection Clause demands that racial classifications y be subjected to the most rigid scrutiny.94 If such measures are to be upheld, it must be shown that they are necessary to promote a compelling or overriding government interest.95 The Department of Justice guidelines on the use of race in criminal investigations follow a similar line. It provides that racial profiling is wrong and stereotyping certain races as having greater propensity to commit crimes is absolutely prohibited, but efforts to defend and safeguard against threat to the national security or integrity of the Nations borders are exempt from racial profiling prohibitions.

According to these guidelines, while the government declares that racial profiling is wrong and immoral, in the same breath it asserts that the war on terror justifies the use of race and ethnicity when similar tactics have been found both ineffective and contrary to equal protection principles in other criminal investigations.96 Moreover, while statutory instruments do not explicitly endorse or encourage racial profiling, the same cannot be said of policies and practice developed by institutions entrusted with countering the financing of terrorism. The UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights asserts that according to the nondiscrimination jurisprudence, a difference in treatment on the basis of a criterion such as race, ethnicity, national origin or religion will only be compatible with the principle of nondiscrimination if it is supported by objective and reasonable grounds.97 Accordingly, the terrorist-profiling practices that involve distinctions according to a persons presumed race cannot be supported by objective and reasonable grounds, because they are based on the wrongful assumption that there are different human races, and therefore inevitably involve unfounded stereotyping through a crude categorisation of assumed races, such as white, black and Asian. As far as distinctions according to national or ethnic origin and religion are concerned, the following two requirements are generally applicable to determine the existence of an objective and reasonable justification. First, the difference in treatment must pursue a legitimate aim. Second, there has to be a reasonable relationship of proportionality between the difference in treatment and the legitimate aim sought to be realised.98 In regard to the first requirement, the aim of law-enforcement practices that are based on terrorist profiling is the prevention of terrorist attacks, and this constitutes a legitimate and compelling social need. The decisive question is therefore whether terrorist-profiling practices, and the differential treatment they involve,

r 2009 Palgrave Macmillan 1745-6452

Journal of Banking Regulation

Vol. 10, 4, 307320

313

Ryder and Turksen

are a proportionate means of achieving this aim. In assessing proportionality, it is necessary to consider whether terrorist-profiling practices are a suitable and effective means of countering terrorism, and also what kind of negative effects these practices may produce. In order to serve as a suitable and effective tool of counterterrorism, a profile would need to be narrow enough to exclude those persons who do not present a terrorist threat, and, at the same time, broad enough to include those who do. However, as the evaluation of current practices reveal, terrorist profiles that are based on characteristics such as ethnicity, national origin and religion are regularly inaccurate and both over- and under-inclusive. Therefore, it can be argued that ethnicity, national origin and religion are inaccurate indicators because the initial premise on which they are based, namely, that Muslims, Arabs or persons of Middle Eastern appearance are particularly likely to be involved in terrorist activities, is highly doubtful. As Leiken and Brookes recent study indicates, Islamist terrorists arrested or killed in Western States showed that less than half of them were born in Middle Eastern countries.99 It is also worrying that the over-inclusive terrorist profiles that are used in SARs overwhelm the law-enforcement system. With the broader profiles, the greater becomes the number of people whom the law enforcement agencies treat as suspects, even though the vast majority of them will turn out to present no risk. This may result in the important lawenforcement resources being diverted away from more beneficial work. Moreover, there is a danger that profiles based on ethnicity, national origin and religion are also underinclusive, and as a consequence may lead law-enforcement agents to miss a range of potential terrorists who do not fit the respective profile. In relation to the SAR requirements, the question remains as to whether financial institutions use suspect descriptions in order to narrowly target those individuals who most resemble the perpetrator or whether they view

suspect descriptions on stereotypes based on mere geographical origin, name, religion and so on.100 In fact, is there a real, clear division between the two approaches? In the context of countering the financing of international terrorism, there seems to be no dissimilarity.101 For example, the current number of known and suspected terrorists who are sought by law enforcement agencies run in thousands.102 Moreover, there are those who are identified as having links or associations with prescribed terrorist organisations. As a result of the current nature of international terrorism, the efforts to identify and find these persons cannot be temporary or geographically limited, based on mere suspect description. Hence, the Department of Justice shares the names of suspected terrorists by adding the names to the National Crime Information Center Database,103 and provides electronic filtering called the System to Assess Risk, used by the FBIs Foreign Terrorist Tracking Task Force, which tracks suspected terrorists. Neither of these tools is available to financial institutions yet, and none of the anti-terrorism laws explicitly regulate the issue of profiling through legislation. Consequently, the financial institutions follow the US Department of Treasurys Guidance on the SAR, which stipulates the modus operandi for conducting the SAR.104 Although the guidelines emphasise the importance of the role of the financial institutions in counter-terrorism efforts and outline what should be included in the SAR, they do not provide a criteria against which the SAR regime should be exercised specifically. The guidelines merely require the reporting institution to ask themselves Why does the filer think the activity is suspicious?105 This allows for a great subjective decision making on the filers behalf and often lacks factual basis. For example, in 40 instances, financial institutions indicated that the SAR was filed because the individual was a pilot or student attending flight school.83 In other instances, financial institutions indicated that the SAR was filed because the account holder appeared to have the same name as individuals

314

r 2009 Palgrave Macmillan 1745-6452

Journal of Banking Regulation

Vol. 10, 4, 307320

Islamophobia or an important weapon?

identified by the media as terrorists, appeared to be of Middle-Eastern descent, or the SAR was filed because of the recent events of terrorist acts.83 It is not surprising therefore that most SARs have provided no use whatsoever for preventing terrorism nor resulted in conviction of suspected terrorists. In its report, FinCEN asserts that SARs greatly enhance cases involving material support to terrorism. However, in the same report, it is also indicated that the only successful conviction relates to a violation of immigration laws, not financing of terrorism. Empirical evidence from a number of schemes involving profiling also underline the ineffectiveness of such strategy. For instance, the German Rasterfahndung did not result in a single criminal charge for terrorism-related offences.106 Instead, the few successes achieved by the German police forces in detecting alleged Islamist terrorists were all achieved by traditional, intelligence-led methods.107 Similarly, in the United Kingdom, the widespread, and ethnically disproportionate, use of stop-and-search powers has produced hardly any results. In 20032004, for example, 8120 pedestrians were stopped under Section 44 (2) of the Terrorism Act 2000. Yet these stops led to only five arrests in connection with terrorism a success rate of 0.06 per cent. Incidentally, all of those arrested were White.108 Finally, in the United States, the targeting of mainly immigrants of Middle Eastern descent has not produced any significant results in the form of arrests or successful convictions either.109 While the effectiveness of such measures may be debated, one ought to consider the long-term effect of such policy on the overall social cohesion of the society as well. As a multi-cultural society, the United States has over a million Muslim citizens of Middle Eastern and/or Arab origin.110,111 Although the SAR regime may not be directed at them, inevitably, American citizens of such origins will also be affected by the SAR regime, especially in terms of how they are perceived

by the general population. Therefore, as aptly asserted by Barak-Erez,112 such practices should not only establish an objective criterion for profiling, but also ensure that it does not have long-lasting effects on innocent people. Even though suspect descriptions may be specific as to time and place, they may still encompass a large number of people. For instance, reliance on an intelligence report that three Muslim men from the Middle East will attempt to finance a terror plot by wire transfers next week could lead to nearly all money transfers from the Middle East being scrutinised. While the supporters of profiling may contend that members of a targeted group have nothing to fear from profiling because they will be exonerated if they are innocent, this is often not the case. For example, persons who are wrongly identified as suspected terrorists can suffer irreparable harm. Khaled el-Masri of Germany proves the case in point.113 In fact, in their efforts to combat financing of terrorism, banks may engage in profiling on the basis of key aspects of a description of a known terrorist such as name and nationality. Inevitably, SARs based on such criteria have resulted in the investigation of thousands of innocent Arabs and Muslims, and could lead to wide stigmatisation of the entire group as potential terrorists. Thus, some may view this sort of investigation as racial profiling. On the other hand, however, it could be perceived as a justified effort to prevent any financial activity that may further terrorism. Given that distinction between legitimate suspect description reliance and prohibited profiling is fuzzy in the war on financing of terrorism, it may be necessary to consider both the proportionality and effectiveness of such practices if we want to establish an intelligent evaluation. Importantly, without reliable information and concrete evidence, connecting suspects or suspicious financial activities to a specific criminal offence will provide hardly any results. It is now accepted that racial profiling does not expose potential terrorists nor increase national

r 2009 Palgrave Macmillan 1745-6452

Journal of Banking Regulation

Vol. 10, 4, 307320

315

Ryder and Turksen

security.114116 On the contrary, such practices undermine national security and alienate targeted groups, while heightening their vulnerability and exclusion from the society. The creation of dualism between us, the natives and them, the targeted groups (for example, Muslims), is also deeply regressive in a globalising society.117 Therefore, dualist approaches (such as liberalism versus terrorism, or liberalism versus Islamic or Christian fundamentalism) to counter-terrorism and financing of terrorism policies are bound to fail. Terrorism is not confined to external threats (that is, al Qaeda), and is also reproduced internally in those societies imbued with Western values. The IRA bombings; the massacre at Waco, Texas; the Oklahoma City bombing; the Aum Shinrikyo (Japanese terrorist cult) gas bomb attack in Tokyo; the recent underground bombings in Istanbul118 and London are just a few prominent examples.119 Even if al-Qaeda and/or Arab terrorists did represent the only terrorist threat, racial profiling would not be effective. The judgments based solely on looks, religion or nationality can be misleading because neither race, nor religion nor nationality assumes a quintessential form. Therefore, there is a great need for reshaping of the counterterrorism policy pertaining to financial activities. The assumption that banks have superior knowledge to detect illicit activity may not apply to terrorist financing. Although the antiterrorism agencies may possess the intelligence that could reveal terrorist operatives and fundraisers, financial institutions generally do not have such capacity. The September 11 plot provides a perfect example. The 19 hijackers hid in plain sight: none of their financial activities could have revealed their real intent. It is common sense to guess that the vast majority of Islamic or Arab bank customers are not terrorists or terrorist supporters, and thus indiscriminately filing SARs on them will do nothing, but waste resources and cause bad will. Similarly, filing a SAR that an Islamic charity is sending money to Afghanistan or Palestine will not be particularly effective in finding terrorist

financiers either. It is very well known that there are many legitimate humanitarian needs in these jurisdictions where such charitable activity can deal with the root causes of terrorism. Moreover, successful counter-terrorism operations depend on the cooperation of the communities where the suspects live. Hence, the UN Special Rapporteur has called on States to foster community policing initiatives that build partnerships of trust between law-enforcement agencies and ethnic and other communities.120 Profiling based on ethnicity, national origin and religion may have the contrary effect of alienating communities from cooperating with law-enforcement authorities, and may thus hamper effective gathering of intelligence. The US government claims that it has robust strategy, which has included the successful, yet controversial closure of the al Barakaat financial network, the Holy Land Foundation for Relief and Development, Afghan Support Committee, the Revival of Islamic Heritage Society and the Al-Haramain organisation.121 It has, however, made limited headway against terrorist finance. The full impact and success of these measures in terms of immobilisation of funds or of knowledge gained about terrorist structures remain uncertain. Terrorist organisations have adapted to the legislative changes introduced in the United States, and they continue to have a vast array of sources of funding available. The impact of these legislative provisions on terrorist finance must therefore be questioned, as al-Qaeda continues to inspire an increasing number of terrorist attacks.

CONCLUSION

The international community was totally unprepared to regulate terrorist finances before the events of 9/11. The terrorist attacks on the Pentagon and the World Trade Center galvanised the international community into action. Within ten days of the attacks, President Bush proclaimed that his administration would stifle terrorist funds wherever they were held in the world. What followed can only be described as

316

r 2009 Palgrave Macmillan 1745-6452

Journal of Banking Regulation

Vol. 10, 4, 307320

Islamophobia or an important weapon?

a plethora of legislation, rules and regulations aimed at preventing terrorist organisations from carrying out such attacks. At the forefront of the US war on terrorist finances is Executive Order 13 224, which had an immediate impact. The US authorities froze assets worth $135 million of nearly 250 individuals and groups who were designated terrorist organisations. Part of this campaign was directed at USbased Islamic charities after it was reported that al-Qaeda received a large percentage of its monies from such organisations. A high-profile attempt to counter terrorist finance resulted in a number of Islamic charities having their assets frozen. What has this realistically achieved? It is controversial. It has alienated potential Islamic investors in the United States, as well as potential international partners who are needed to confront the problems caused by terrorist finance. Furthermore, innocent people with certain attributes and characteristics have been targeted and investigated without justification. The introduction of additional reporting requirements under the USA PATRIOT Act 2001 does little to advance the so-called war on terrorist finances. The inadequacies of the previous legislation were highlighted by the 9/11 Commission, which reported that one of the suicide terrorists had been the subject of an SAR in 2000. This SAR was one of over 1.2 million such reports filed with the US authorities between 1996 and 2003. The new regulations placed on the US banking sector are burdensome, and the compliance costs are huge. The use and effectiveness of such a policy must therefore be questioned.

4 5

10

11 12

13

14

REFERENCES AND NOTES

1 Annex to Resolution 49/60, Measures to eliminate international terrorism, 9 December 1994, 49/60. 2 Article 1. para. 1 of the Convention, The United Nations (1999). 3 However, it must be noted that this is not a new concept or strategy. See, for example, Rider, B. (2002) The weapons of war: The use of anti-money laundering laws against terrorist and criminal enterprises Part I (2002). Journal of International Banking Regulation 4(1): 1331, at 14. A reaction to these attacks was the issuing of Executive Order 13 129, which prevented access to property and outlawed

15

16

17

18 19

dealings with the Taliban. See Exec. Order No. 13224, 3 C.F.R. 786 (2001), reprinted in 50 USC.S. 1701 (2001). Bantekas, I. (2003) The international law of terrorist financing. American Journal of International Law 97: 315333, at 315. For a detailed discussion of this issue see Chase, A. (2004) Legal mechanisms of the international community and the United States concerning the state sponsorship of terrorism. Virginia Journal of International Law 45(1): 137141. See US Department of State State sponsors of terrorism, n/d, http://www.state.gov/s/ct/c14151.htm, accessed 13 March 2009. This may attributable to the depth of shared international commitment to an effective, sustained and multilateral response to the problem of terrorism since 9/11. Within the United Nations, the Security Council was the first to react and unanimously passed resolutions 1368 (2001), 1373 (2001) and 1566 (2004) in order to prevent and suppress terrorism, while the General Assembly adopted resolution 56/1 (2001) by consensus. Arguably, along with some 19 global and regional treaties pertaining to the subject of international terrorism, there is now a more robust political and legal deterrence to counter-terrorism. Quenivet, N. (2005) The world after September 11: Has it really changed? The European Journal of International Law 16(3): 561575, at 561. The 9/11 Commission. (2004) The 9/11 commission report Final report of the national commission on terrorist attacks upon the United States, London: Norton, p. 170. The self sufficiency-of terrorist cells was also recognised by the official report on the terrorist attacks on London on the 7 July 2005. See House of Commons. (2005) Report of the official account of the Bombings in London on 7th July 2005. London: House of Commons, p. 23. Winer, J. and Roule, T. (2002) Fighting terrorist finance. Survival 44(3): 87104, at 89. See Ryder, N. (2007) A false sense of security? An analysis of legislative approaches to the prevention of terrorist finance in the United States of America and the United Kingdom. Journal of Business Law November, 821850. Alexander, K. (2001) The international anti-money laundering regime: The role of the financial action task force. Journal of Money Laundering Control 4(3): 231248, at 231. For a more detailed discussion of this see Ping, H. (2004) New trends in money laundering From the real world to cyberspace. Journal of Money Laundering Control 8(1): 4855. See, for example, Linn, C. (2005) How terrorist exploit gaps in US anti-money laundering laws to secrete plunder. Journal of Money Laundering Control 8(3): 200214. Baldwin Jr., F. (2002) Money laundering countermeasures with primary focus upon terrorism and the USA patriot act 2001. Journal of Money Laundering Control 6(2): 105136, at 112. For a more in depth discussion of the operation of underground banking systems see Trehan, J. (2002) Underground and parallel banking systems. Journal of Financial Crime 10(1): 7684. Rider, above n 3, at p. 28. This system has also been referred to as the hundi or fei chien banking system. See, for example, Pathak, R. (2004)

r 2009 Palgrave Macmillan 1745-6452

Journal of Banking Regulation

Vol. 10, 4, 307320

317

Ryder and Turksen

20

21

22 23

24

25 26 27

28 29 30 31 32

33 34 35

36 37 38 39 40 41

42 43

44

The obstacles to regulating the hawala: A cultural norm or a terrorist hotbed? Fordham International Law Journal 27(6): 20072061. Razavy, M. (2005) Hawala: An underground haven for terrorists or social phenomenon? Crime, Law and Social Change 44(3): 277299. Schramm, M. and Taube, M. (2003) Evolution and institutional foundation of the Hawala financial system. International Review of Financial Analysis 12(4): 405420, at 407. Pathak, above n 19, at p. 2008. See, for example, Waszak, D. (2004) The obstacles to suppressing radical Islamic terrorist financing case western reserve. Journal of International Law 35(23): 673710. For a detailed explanation of the practical workings of the hawala system see Daudi, A. (2005) The invisible bank: Regulating the hawala system in India, Pakistan and the United Arab emirates. Indiana International and Comparative Law Review 15(3): 619654. Razavy, above n 20, at p. 287. Ryder, above n 13, at p. 829. See Wheatley, J. (2005) Ancient banking, modern crimes: How Hawala secretly transfers the finances of criminals and thwarts existing laws university of Pennsylvania. Journal of International Economic Law 26(2): 347374. M. Schramm and M. Taube, above n 21, at p. 409. Jamwal, N. (2000) Hawala The invisible financing system of terrorism. Strategic Analysis 26(2): 181198, at 182. Jost, P. and Sandhu, K. (2000) The Hawala Remittance System and its Role in Money Laundering. Lyon, France: Interpol. See, for example, Wheatley, above n 29, at p. 347. The 9/11 Commission conclude that the funds used for these attacks were directly transferred into the bank accounts of the terrorists through the formal US banking system, not through the hawala system. See 9/11 Commission, above n 10, at pp. 170171. Navias, M. (2002) Financial warfare as a response to international terrorism. The Political Quarterly 73(1): 5779, at 61. Rider, above n 3, at p. 25. For a more detailed discussion of this see Ryder, N. (2008) The financial services authority, the reduction of financial crime and the money launderer A game of cat and mouse. Cambridge Law Journal 67(3): 635653. Winer and Roule, above n 12, at p. 88. S.C. Res, 1373, U.N. SCOR, 56th Sess., 4385th Mtg. Article 1(a). S.C. Res, 1373, U.N. SCOR, 56th Sess., 4385th Mtg. Article 1(b). S.C. Res, 1373, U.N. SCOR, 56th Sess., 4385th Mtg. Article 1(c). S.C. Res, 1373, U.N. SCOR, 56th Sess., 4385th Mtg. Article 1(5). Myers, J. (2003) Disrupting terrorist networks: The new US and international regime for halting terrorist finance. Law and Policy in International Business 34(1): 1723, at 21. Levitt, above n 9, at p. 6. For a more detailed discussion on this law see Pogue, A. (2005) If it werent for the flip side Can the USA Patriot Act help the US pursue drug dealers and terrorists overseas, without overstepping constitutional boundaries at home. Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy 14: 486493. See Myers, above n 49, at p. 17.

45 For a critical review of these powers see McCulloch, J. and Pickering, S. (2005) Suppressing the financing of terrorism Proliferating state crime, eroding centure and extending no-colonialism. British Journal of Criminology 45(4): 470486, at 470. 46 Seldon, R. (2003) The executive protection: Freezing the financial assets of alleged terrorists, the constitution, and foreign participation in US financial markets. Fordham Journal of Corporate and Financial Law 8(3): 491552. 47 OFAC enforces economic and trade sanctions based on US foreign policy and national security goals against targeted foreign countries, terrorists and those engaged in proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. 48 For a more detailed discussion of the US governments ability to classify groups as specially designated terrorist group or a foreign terrorist organisation see Crimm, N.J. (2004) High alert: The Governments war on the financing of terrorism and its implications for donors, domestic charitable organisations and global philanthropy. William and Mary Law Review 45: 13411449, at 1369. 49 US Treasury Department. (2006) Office of Terrorism and Financial Intelligence US Department of Treasury Fact Sheet. Washington: US Department of Treasury, p. 5. 50 Waszak, above n 23, at p. 673. 51 Winer and Roule, above n 12, at p. 88. 52 See Navias, above n 37, at p. 59. 53 Seldon, above n 56, at p. 502. 54 Ibid., at 503. 55 See, for example, Hardister, A. (2003) Can we buy peace on earth?: The price of freezing terrorist assets in a postSeptember 11 world North Carolina. Journal of International and Commercial Regulation 28: 605661. 56 Baron, B. (2005) The Treasury guidelines have had little impact overall on US international philanthropy, but they have had a chilling impact on US based Muslim charities. Pace Law Review 25: 309317, at 315. 57 Ibid., at p. 317. 58 On 25 November 2008, five of the organisers of the Holy Land Foundation were convicted of providing over $12 million to Hamas. See Trahan, J. and Eiserer, T. (2008) Holy land foundation defendants guilty on all counts. Dallas Morning News, 25 November 2008, www.dallasnews.com. 59 For an excellent discussion of this case see Nicols, G. (2008) Repercussions and recourse for specially designated terrorist organisations acquitted of materially supporting terrorism. Review of Litigation 28: 263293. 60 Ruff, K. (2006) Scared to donate: An examination of the effects of designating Muslim charities as terrorist organisations on the first amendment rights of Muslim donors New York University. Journal of Legislation and Public Policy 9: 447502, at 449. 61 Ibid., p. 465. 62 Engel, M. (2004) Donating blood money: Fundraising for international terrorism by United States charities and the governments efforts to constrict the flow Cardozo. Journal of International and Comparative Law 12: 251296, at 283. 63 Ruff, above n 69, at pp. 464471. 64 The 9/11 Commission called the US approach towards Muslim charities as aggressive and that it did have concerns about certain civil liberties. See 9/11 Commission, above n 10.

318

r 2009 Palgrave Macmillan 1745-6452

Journal of Banking Regulation

Vol. 10, 4, 307320

Islamophobia or an important weapon?

65 United States Treasury Department. (2002) Contributions by the Department of the Treasury to the Financial War on Terrorism. Washington: US Treasury Department, pp. 1011. 66 Title III is also known as the International Money Laundering Abatement and Anti-terrorist Financing Act 2001. 67 USA PATRIOT Act 2001, Sections 311330. 68 For a more detailed assessment and commentary about the SARs regime, see FinCEN. (1998) 1st Review of the Suspicious Activity Reporting Systems. Washington: FinCEN. 69 See, generally, Adams, T. (2000) Tacking on money laundering charges to white collar crimes: What did congress intend, and what are the courts doing? Georgia State University Law Review 17(2): 531573. 70 Baldwin Jnr, above n 17, at p. 118. 71 FinCEN. (2008) The SAR Activity Review By the Numbers. Washington: FinCEN, p. 5. 72 Roberts, M. (2004) Big brother isnt just watching you, hes also wasting your tax payer dollars: An analysis of the antimoney laundering provisions of the USA Patriot Act Rutgers. Law Review 56: 573602, at 584. 73 The US Treasury Department reported that there in 2001, there were 12.6 million currency transaction reports were filed (these are required for transactions over $10 000) and 182 000 suspicious activity reports were filed with the Treasury Department. See US Treasury Department, above n 74, at 6. 74 See above n 74, at p. 82. 75 Bumiller, E. and Myers, S.L. (2001) Senior administration official defend military tribunals for terrorist suspects. New York Times, 15 November, citing Vice President Dick Cheney, 14 November, www.nytimes.com. 76 Harris, D. (2002) Racial profiling revisited: Just common sense in the fight against terror. Criminal Justice 17(2): 3641. 77 A number of international legal instruments (for example Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948 and Article 2(1) and 26 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966) and the US Constitution prohibit discrimination and require equality before the law. 78 Lee, C. (2006) Constitutional cash: Are banks guilty of racial profiling in implementing the United States patriot act? Michigan Journal of Race and Law 11(Spring): 557604, at 562. 79 Lee, above n 87, at p. 558. Similar trends can be observed in the United Kingdom. For example, in 2003/2004 Asian people were about 2.9 times more likely and black people about 3.3 times more likely, to be stopped and searched under anti-terrorism legislation than white people. After the London bombings of July 2005 this ratio increased 12-fold for Asian people. See Home Office. (2006) Statistics on Race and the Criminal Justice System 2005. London: Home Office, p. 31. 80 Lee, above n 87, at p. 564. 81 See, for example, Shaw v. Reno, 509 US 630, 643644 (1993); Edmonson v. Leesville Concrete Co., 500 US 614, 630631 (1991). 82 See Lee, above n 87, at p. 564. 83 See FinCEN. (2002) The SAR Review and Activity Tips and Trends Issue 4. Washington: FinCEN. 84 There were 1016 SARs that recorded $0 as the violation amount. 85 Ramirez defines racial profiling as the inappropriate use of race, ethnicity or national origin, rather than behaviour

86

87 88 89

90 91

92

93

94 95

96

97

98

or individualised suspicion, to focus on an individual for additional investigation. See Ramirez, D. Hoopes, J. and Quinlan, T. (2003) Defining racial profiling in a postSeptember 11. World American Criminal Law Review 40: 11951233, at 12021207. Gross, S. and Livingston, D. (2002) Essay, racial profiling under attack. Columbia Law Review 102: 14131438, at 1415. The US jurisprudence also confirms this view that a prohibition of racial profiling would not obligate law enforcement agencies from investigating only members of a particular race or origin if they are seeking a specific perpetrator who has been identified as a member of that race. See, Brown v. State, 592 So. 2d 1237 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 1992); Commonwealth v. Mercado, 663 N.E.2d 243 (Mass. 1996) and Commonwealth v. McDonald, 740 A.2d 267 (Pa. Super. Ct. 1999). US v. Kim, 25 F.3d 1426, 1431 n.3 (9th Cir. 1994). See, for example, US v. Waldon, 206 F.3d 597, 604 (6th Cir. 2000). The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution provides that no State shall y deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. The Supreme Court in Yick Wo v. Hopkins 118 US 356, 369 (1886) has recognised that the Equal Protection Clause is applicable to all persons within the territorial jurisdiction, without regard to any differences of race, of color, or of nationality. See Cole, D. (2000) No Equal Justice. New York: New Press. Taylor, S. (2004) The skies wont be safe until we use commonsense profiling. In: K. Darmer et al (eds.) Civil Liberties vs National Security: In a Post 9/11 World. New York: Prometheus Books. Harris, D. (2004) Racial profiling revisited: Just common sense in the fight against terror?. In: K. Darmer et al (eds) Civil Liberties vs National Security: In a Post 9/11 World. New York: Prometheus Books. See Bahdi, R. (2003) No exit: Racial profiling and Canadas war against terrorism. Osgoode Hall Law Journal 41: 231293. Loving v. Virginia 388 US 1, 11 (1967). McLaughlin v. Florida 389 US 184, 196 (1964); Adarand Constructors, Inc v. Pena 515 US 200, 227 (1995). Similarly, in the United Kingdom, the House of Lords held that unless good reason exists, differential treatment based on race are properly stigmatised as discriminatory. See, Ghaidan v. Godin-Mendoza 2004 UKHL 30, para 9. Rudovsky, D. and Banks, R. (2007) Racial profiling on the war on terror. University of Pennsylvania Law Review 155: 173184. Human Rights Committee, general comment no. 18: Nondiscrimination (1989), para. 13; Human Rights Committee, Broeks v. The Netherlands, communication No. 172/1984 (CCPR/C/OP/2), para. 13 (1990); Belgian Linguistics Case (No. 2) (1968) 1 EHRR (European Human Rights Reports) 252, para. 10; Proposed Amendments to the Naturalization Provisions of the Constitution of Costa Rica, Advisory Opinion OC-4/84, Inter-American Court of Human Rights (Ser. A) No. 4 (19 January 1984), para. 57. For detailed discussion on this issue see Moeckli, D. (2008) Human Rights and Non-discrimination in the War on Terror. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

r 2009 Palgrave Macmillan 1745-6452

Journal of Banking Regulation

Vol. 10, 4, 307320

319

Ryder and Turksen

99 Leiken, R. and Brooke, S. (2006) The quantitative analysis of terrorism and immigration: An initial exploration. Terrorism and Political Violence 18(4): 503521. 100 On the topic of construction of race before and after September 11, see Joo, T. (2002) Presumed disloyal: Executive power, judicial deference and the construction of race before and after September 11. Columbia Human Rights Law Review 34: 147. 101 Banks, R. (2004) Racial profiling and antiterrorism efforts. Cornell Law Review 89: 12011217, at 1206. 102 According to the lists provided by Treasury Department, the State Department, the Department of Justice, the Federal Bureau of Investigations, the UN and other allied countries there are nearly 400 000 names from 239 countries. 103 Department of Justice. (2003) New terrorist screening center established: Federal government consolidates terrorist screening into single comprehensive anti-terrorist watchlist. 16 September, www.fbi.gov/pressrel/pressrel03/ tscpr091603.htm, accessed 16 April 2009. 104 FinCEN. (nd) Suspicious activity reporting guidance, http://www.fincen.gov/news_room/rp/sar_guidance.html, accessed 20 February 2009. 105 It is difficult to determine whether race might constitute the only factor subjecting a person to SAR or whether it constitutes only one factor among a group of factors. This is because the financial institution can usually find some basis, independent of race, which might raise suspicion. For example, acting too nervous or amount of the money transfer may be used as a criterion. 106 See the decision of the Bundesverfassungsgericht (the Federal Constitutional Court) of Germany in decision BVerfG, 1 BvR 518/02, 4 April 2006, http://www .bverfg.de/entscheidungen/rs20060404_1bvr051802.html, para. 28 (explaining that in the Federal State) of Nordrhein-Westfalen, 5.2 million personal data sets were collected). 107 See, for example, Hessischer Landtag, Kleine Anfrage des Abg. Hahn (FDP) vom 10.03.2004 betreffend Ergebnisse der Rasterfahndung und Antwort des Ministers des Innern und fu r Sport, Drucksache 16/2042, 18 May 2004. 108 Home Office. (2004) Statistics on Race and the Criminal Justice System 2003. Home Office: London, p. 28 and Home Office, above n 89, at p. 35. 109 See Lawyers Committee for Human Rights. (2003) Assessing the new normal: Liberty and security for the post-September 11 United States. United States of America: Lawyers Committee for Human Rights, p. 39. 110 Rudovsky, above n 107, at p. 176. It is important to note that not all Arabs or people form the Middle East are Muslims. It is reported that only 20 per cent of Muslims are Arabs. See, Middle East Policy Council. (nd) Arab World Studies Notebook: Muslims Worldwide, www.mepc.org/

111

112

113

114

115 116

117

118

119

120

121

public_asp/workshops/musworld.asp, accessed 10 January 2009. For a detailed analysis see Kulczycki, A. and Lobo, A. (2001) Deepening the melting pot: Arab Americans at the close of the century. Middle East Journal 55(3): 459473. Barak-Erez, D. (2007) Terrorism and profiling: Shifting the focus from criteria to effects. Cardozo Law Review 29: 18, On the consequence of the use of anti-terror policy solely on Arabs and Muslims see Council on American-Islamic Relations Research Center (2002). The Status of Muslim Civil Rights in the United States: Stereotypes and Civil Liberties, www.cair-net.org/civilrights2002/civilrights2002 .pdfm, accessed 15 February 2009. For full details of el-Masris ordeal see, Amnesty International, The Rendition of Khaled el-Masri: USA/ Macedonia/Germany, 9 August 2006, AI Index: AMR 51/133/2006. See, for example, Cole, D. (2003) Enemy Aliens: Double Standards and Constitutional Freedoms in the War on Terrorism. London: New Press. Hewitt, D. (2003) Understanding Terrorism in America: From the Klan to Al Qaeda. London: Routledge, p. 93. Shaftoe, H., Turksen, U., Lever, J. and Williams, S. (2007) Dealing with terrorist threats through a crime prevention and community safety approach. International Journal of Crime Prevention and Community Safety 9(4): 291307. Like security, ethnic affinity is also a social construct that can change over time. Australian and Americans, for example, redefined themselves so that Asians are no longer excluded as inassimilable peoples. Similarly, many West Europeans regard East Europeans as fellow-Europeans, more acceptable as migrants than people from North Africa or Middle East. Who is or is not one of us and can join the club is historically variable. Too many nineteenth century Americans and British, Africans and Caribbean were not one of us, and today for many Westerners, Muslims are not one of us. Also note that of arrests made under the UK AntiTerrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 in 2003, 30 per cent of the detainees are British Citizens. See Privy Counsellor Review Committee. (2003) Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 Review, Report. London: House of Commons, para. 193. BBC News. (2007) Investigation into the latest bombings in London identified and convicted five suspects all of whom are British nationals. 1 May, http://news.bbc .co.uk/1/hi/uk/4676861.stm, accessed 21 December 2008. The UN Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism, 29 January 2007 A/HRC/4/26. US Treasury Department, above n 74, at p. 6.

320

r 2009 Palgrave Macmillan 1745-6452

Journal of Banking Regulation

Vol. 10, 4, 307320

Você também pode gostar

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Good Hunting German Submarine OffensiveDocumento22 páginasGood Hunting German Submarine Offensivegladio67Ainda não há avaliações

- Paper Mills and Fabrication - 0002Documento9 páginasPaper Mills and Fabrication - 0002gladio67Ainda não há avaliações

- The Kavango Jeugbeweging and The South ADocumento34 páginasThe Kavango Jeugbeweging and The South Agladio67100% (1)

- Emigre Politics and The Cold War The NatDocumento16 páginasEmigre Politics and The Cold War The Natgladio67Ainda não há avaliações

- Multiple Fronts of The Cold War Ethnic A PDFDocumento32 páginasMultiple Fronts of The Cold War Ethnic A PDFgladio67Ainda não há avaliações

- Journal of Strategic Studies: To Cite This Article: Magnus Petersson (2006) The Scandinavian Triangle: DanishDocumento28 páginasJournal of Strategic Studies: To Cite This Article: Magnus Petersson (2006) The Scandinavian Triangle: Danishgladio67Ainda não há avaliações

- Paper Mills and Fabrication - 0001Documento79 páginasPaper Mills and Fabrication - 0001gladio67Ainda não há avaliações

- Cold War Allies: The Origins of CIA's Relationship With Ukrainian Nationalists (S)Documento25 páginasCold War Allies: The Origins of CIA's Relationship With Ukrainian Nationalists (S)gladio67Ainda não há avaliações

- For The Freedom of Captive European Nati PDFDocumento19 páginasFor The Freedom of Captive European Nati PDFgladio67Ainda não há avaliações

- Controversies of US-USSR Cultural Contac PDFDocumento27 páginasControversies of US-USSR Cultural Contac PDFgladio67Ainda não há avaliações

- Eisenhower and The First Forty Days Aft PDFDocumento39 páginasEisenhower and The First Forty Days Aft PDFgladio67Ainda não há avaliações

- Espionage Against Poland in The DocumentDocumento24 páginasEspionage Against Poland in The Documentgladio67Ainda não há avaliações

- Bines - Polish Section SOE 1940-1946 - 2008 ThesisDocumento299 páginasBines - Polish Section SOE 1940-1946 - 2008 Thesisgladio67Ainda não há avaliações

- Back To The Motherland Repatriation and PDFDocumento264 páginasBack To The Motherland Repatriation and PDFgladio67Ainda não há avaliações

- (Richard Wires) The Cicero Spy Affair German AccessDocumento281 páginas(Richard Wires) The Cicero Spy Affair German Accessgladio67Ainda não há avaliações

- 1byrne J J Mecca of Revolution Algeria Decolonization and TheDocumento409 páginas1byrne J J Mecca of Revolution Algeria Decolonization and Thegladio67Ainda não há avaliações

- War Atlas From 1915 YearDocumento24 páginasWar Atlas From 1915 YearDiwko CircAinda não há avaliações

- Roger Hermiston - The Greatest Traitor. The Secret Lives of Agent George Blake-Quayside Publishing Group - MBI - Aurum Press LTD (2014)Documento342 páginasRoger Hermiston - The Greatest Traitor. The Secret Lives of Agent George Blake-Quayside Publishing Group - MBI - Aurum Press LTD (2014)gladio67100% (1)

- Stella Remington Open Secret - 2002Documento192 páginasStella Remington Open Secret - 2002gladio67100% (1)

- Spy CatcherDocumento325 páginasSpy CatcherEwan OwenAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Abu Sayyaf - The Father of The SwordsmanDocumento9 páginasAbu Sayyaf - The Father of The SwordsmanThe American Security ProjectAinda não há avaliações

- A Crtical Review of The Book "Imperialism, Sovereignty and The Making of International Law"Documento5 páginasA Crtical Review of The Book "Imperialism, Sovereignty and The Making of International Law"DamudorAinda não há avaliações

- BROMOZINEDocumento13 páginasBROMOZINEFrank GallagherAinda não há avaliações

- Offshore Wind 2AC BlocksDocumento201 páginasOffshore Wind 2AC BlocksSamdeet KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Muhammad Achievement and Heritage by Zaky RawdatDocumento148 páginasMuhammad Achievement and Heritage by Zaky RawdatBukti Dan SaksiAinda não há avaliações

- IMF and AML PDFDocumento3 páginasIMF and AML PDFFrancis Njihia KaburuAinda não há avaliações

- 7477 Digitalstoryreferences SMPDocumento11 páginas7477 Digitalstoryreferences SMPapi-248684364Ainda não há avaliações

- SAT Issue 02-18Documento32 páginasSAT Issue 02-18Shahid KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Article 1Documento6 páginasArticle 1Kushal MansukhaniAinda não há avaliações

- RD TH: Comment (DRS1) : Reviewed by Daphne SykesDocumento2 páginasRD TH: Comment (DRS1) : Reviewed by Daphne SykespkgalAinda não há avaliações

- Manila Bulletin Charlie HebdoDocumento3 páginasManila Bulletin Charlie Hebdoronnie 1992Ainda não há avaliações

- QuestionnaireDocumento4 páginasQuestionnairesaraAinda não há avaliações

- Expert Report Shows Sovereign Citizen Extremists Will Use Bank Debt Collection Units To Target VictimsDocumento14 páginasExpert Report Shows Sovereign Citizen Extremists Will Use Bank Debt Collection Units To Target VictimslenorescribdaccountAinda não há avaliações

- Book Reviews I P ' I: Slam and Akistan S DentityDocumento12 páginasBook Reviews I P ' I: Slam and Akistan S DentityMohsinAliShahAinda não há avaliações

- Cyberspace Cybersecurity and Cybercrime 1st Edition Kremling Test Bank DownloadDocumento12 páginasCyberspace Cybersecurity and Cybercrime 1st Edition Kremling Test Bank DownloadsusanmitchelltbirekmnqzAinda não há avaliações

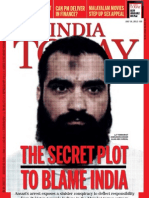

- India Today - 16 July 2012Documento184 páginasIndia Today - 16 July 2012Aparupa DasguptaAinda não há avaliações

- Al-Shabaab Publishes Alleged Photograph of Dead French Commando PDFDocumento3 páginasAl-Shabaab Publishes Alleged Photograph of Dead French Commando PDF3FnQz8tgAinda não há avaliações

- Ejk BackgroundDocumento22 páginasEjk Backgroundmz rph100% (1)

- How Facebook Protects The Perpetrators Instead of The TI in Cyberstalking - BullyingDocumento4 páginasHow Facebook Protects The Perpetrators Instead of The TI in Cyberstalking - BullyingJusticeTIAinda não há avaliações

- Detailed Lesson PlanDocumento15 páginasDetailed Lesson PlanIan AtienzaAinda não há avaliações

- The Good Enough Doctrine: Learning To Live With TerrorismDocumento13 páginasThe Good Enough Doctrine: Learning To Live With TerrorismEla MuñozAinda não há avaliações

- Failure of Polio Eradication in PakistanDocumento4 páginasFailure of Polio Eradication in PakistanAamir BugtiAinda não há avaliações

- Evidence Timelines. by Oscar Carmona GilDocumento4 páginasEvidence Timelines. by Oscar Carmona GilOscar Alberto CarmonaAinda não há avaliações

- Lynch 2006Documento26 páginasLynch 2006Elham RafighiAinda não há avaliações

- Constrains of S: TH RDDocumento8 páginasConstrains of S: TH RDKamrul HasanAinda não há avaliações

- The Monkey Wrench Gang Seminar ReflectionDocumento3 páginasThe Monkey Wrench Gang Seminar Reflectionapi-2530632710% (1)

- Reglamento Para La Adopción de Medidas Cautelares Sobre Bienes y Fondos Respecto Del Delito Vinculado Con El Terrorismo y Su Financiamiento, Previsto en El Código Orgánico Integral Penal Completo FinishDocumento61 páginasReglamento Para La Adopción de Medidas Cautelares Sobre Bienes y Fondos Respecto Del Delito Vinculado Con El Terrorismo y Su Financiamiento, Previsto en El Código Orgánico Integral Penal Completo FinishPedroAldasAlvarezAinda não há avaliações

- Idu Unit Script - Palestine Israel First DraftDocumento3 páginasIdu Unit Script - Palestine Israel First Draftapi-300755806Ainda não há avaliações

- The Financial Action Task ForceDocumento6 páginasThe Financial Action Task ForceSaba GhaziAinda não há avaliações

- What Is Terrorism - PrimoratzDocumento13 páginasWhat Is Terrorism - PrimoratzRoger FrancoAinda não há avaliações