Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

HEARN, Adrian - China and Latin America - Economy and Society

Enviado por

Daniel AraujoDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

HEARN, Adrian - China and Latin America - Economy and Society

Enviado por

Daniel AraujoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

China and Latin America: Economy and Society

Adrian Hearn

The expansion of Chinas economic and political alliances in the Western Hemisphere in the early 21st century signals its emerging international inuence. Latin America has become a crucial source of oil, copper, coal, steel, grain, and other resources for China, stimulating economic growth in supplier countries but also a range of new dilemmas for the regions development. This article explores Chinas integrated pursuit of social, political, and economic goals in the region and the local reactions this has provoked. Drawing on case studies, interviews, and observations gathered in China, Cuba, and Mexico, the article argues that Chinas approach to Latin America is characterized by a blend of state and market strategies for building long-term cooperation, social capital, and understanding. La expansin de las alianzas econmicas y polticas de China en el hemisferio occidental a principios del siglo XXI muestra su emergente inuencia internacional. Amrica Latina se ha convertido en una fuente crucial de petrleo, cobre, carbn, acero, granos y otros recursos para China, lo que estimula el crecimiento econmico de los pases abastecedores, pero tambin una serie de nuevos dilemas para el desarrollo de la regin. Este artculo examina la integral bsqueda de China de retos sociales, polticos y econmicos en la regin y las reacciones locales que esta ha provocado. Al basarse en estudios de caso, entrevistas y observaciones recolectadas en China, Cuba y Mxico, el artculo argumenta que el acercamiento chino a Amrica Latina est caracterizado por una mezcla de estrategias de Estado y de mercado para crear una cooperacin a largo plazo, capital social y entendimiento.

Key words: Latin America, China, social capital, soft power, international relations

he acquisition of energy, mineral, and agricultural resources is a key dimension of Chinas foreign policy, and observers have recognized China as the new engine of Latin American growth (Jiang, 2005; Zweig & Jianhai, 2005). Resource exporters, such as Argentina and Brazil (iron ore and soy beans), Chile (copper), Cuba (nickel), Peru (copper and shmeal), and Venezuela (crude oil), have beneted from increasing demand and rising commodity prices. Countries that export few natural resources, such as Mexico and the nations of Central America, have experienced signicant trade decits as Chinese manufactured products enter their markets.

Latin American PolicyVolume 4, Number 1Pages 2435 2013 Policy Studies Organization. Published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

China and Latin America

25

This article argues that China has approached Latin America by building cooperative relationships with nations across the political spectrum, whether they export natural resources or not. This strategy hinges largely on how well China can overcome the sociopolitical challenge of harmoniously integrating politically diverse actors and nations into a cohesive foreign policy framework. To deepen bilateral relationships, China has developed state-to-state programs that prioritize the accrual of trust and social capital over the long term. This has become particularly important for promoting goodwill with countries like Mexico, where the economic terms of trade have disproportionately favored China.

China and International Community Building

Chinas foreign policy, as articulated to the United Nations, does not reveal specic geopolitical objectives but rather endorses a global environment that sustains the prerogative of sovereign nations to interact and collaborate with each other in stable, long-term partnerships (PRC, 2004). Such an environment suits the needs of an emerging power that has established itself as a nonaligned international protagonist seeking to deepen its global inuence over the course of the 21st century.1 Chinas success over the past decade in building relationships with socialist countries such as Cuba and Venezuela while simultaneously forging links with more-conservative countries such as Mexico, Columbia, and the nations of Central America, illustrates its capacity to transcend traditional political divides. One of Chinas strengths is its approach to a central challenge faced by any community-building initiative: the integration of actors, organizations, and nations, each with diverse agendas and aspirations, into a comprehensive policy framework. Sociological research into the effect of social capital on economic development, democratization, and civic participation has shed light on the problems of community building and collaborative social integration in domestic scenarios (Evans, 1996; Fedderke, de Kadt, & Luiz, 1999; Hearn, 2008; Lin, 2001; Portes, 1998; Putnam, 2000; Woolcock, 1998). Applied to the international scale, some of the ndings of this literature help to explain how China has set about building a global community and how governments in the Americas have reacted to this prospect. A good starting point is an article by Johannes Fedderke et al. (1999) that reects on the international implications of domestic social capital formation. The authors argue that a key determinant of a governments ability to develop effective international partnerships is its ability to rationalize domestic economic practices and customs into a form that is intelligible to foreign actors. This process is characterized by the transformation of substantive local rules and values into a wider system of procedural norms, or the gradual replacement of informal associations and networks by formal administrative structures, and the impersonal market mechanism no longer tied to individual identities . . . Action premised on social capital with a rationalized mode of delivery is rendered more exible, and stands a greater chance of successful adaptation to a wide range of environmental circumstances (Fedderke et al., 1999, pp. 719, 721). In practice, this means that nations seeking to integrate themselves into larger international markets should rst pass through a series of domestic reforms to minimize the

26

Latin American Policy

inuence of administrative idiosyncrasies and interpersonal afnities on their economic and legal systems, because other global actors may not share these. During the Cold War, the processes of domestic rationalization that most countries pursued were characterized by the privatization and opening of markets to facilitate integration into the U.S.-led system of free trade or by the centralization and regulation of markets to facilitate integration into the trade regime of the Soviet-led United Front. Whereas the former countries developed legal codes to protect commercial initiatives capable of rapidly generating nancial capital, the latter produced political alliances that prioritized the long-term stability of state-led economic exchange and resource bartering. In the rst decade of the 21st century, the emergence of the new left in Latin America, galvanized by experiments with alternative regional models of trade and development and by broad disenchantment with the Washington Consensus, challenged the ascendancy of global capitalism since the late 1980s. The term new left was coined in the early 2000s to describe the elected governments of Hugo Chvez in Venezuela (1998 and 2007), Luiz Incio Lula da Silva in Brazil (2002 and 2006), Kristina Kirchner in Argentina (2007), Tabar Vsquez in Uruguay (2004), Evo Morales in Bolivia (2005), Michele Bachelet in Chile (2006), Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua (2006), and Rafael Correa in Ecuador (2006), which together came to govern nearly 60% of Latin Americas population of 527 million (Arnson, 2007, p. 3). Although these leaders exhibited varying degrees of caution regarding upsetting trade relations with the United States, all signaled a greater role for the state in economic affairs and moved to strengthen regional alliances that reduce dependence on the U.S. market. All also set in motion closer relationships with China.2 Recognizing the opportunities and risks that this scenario poses, China has reciprocated with a strategic balance of economic and diplomatic engagement. The basis of this balance is a calculated integration of practices that two decades ago would have been unequivocally identied as communist or capitalist. China has worked hard to develop state-to-state institutional alliances that foster long-term collaboration and build political legitimacy with cooperating governments (much as the Soviet Union did), but it has done this as a World Trade Organization (WTO) member employing the mechanisms of global capitalism to advance its position in the world market.3 To avoid comparisons with the Soviet Unions Cold War attempts to build a communist United Front, Chinas language has been colored with less-threatening commitments to southsouth cooperation, a nonaligned agenda and solidarity with an international community of developing nations. As social capital theorists Alejandro Portes and Julia Sensenbrenner (1993) have shown at the microlevel, communities that perceive themselves to be in some way disadvantaged or subordinated to larger dominating forces are especially likely to develop mechanisms of cooperation, trust, and social capital. In a 2004 press conference with Fidel Castro, Hu Jintao invoked just such a scenario, stating that China and Cuba have helped each other and treated each other with sincerity . . . We are fraternal brothers . . . passing the test of changing and adverse international circumstances (Murray, 2004; also see Lam, 2004, p. 3; Len-Manrquez, 2006, p. 45). At the 2006 meeting of the Non-Aligned Movement in Havana, China extended an invitation for greater southsouth solidarity to

China and Latin America

27

Latin America as a whole. These commitments have materialized in trade accords and exchange programs established by a constant ow of high-level Chinese diplomats to Latin America, including President Hu Jintao in 2004 and 2008 and President-in-waiting Xi Jinping in 2011. As a result of these accords, ChinaLatin America trade grew from US$10 billion in 2000 to more than US$240 billion in 2011. U.S. Commerce Department ofcial Tim Ashby has pointed out that China often pays its bills with trade credits, construction equipment, infrastructure upgrading, and technical training rather than hard currency, making deals like those forged with Cuba less economically signicant than they may seem (Robles, 2005). Nevertheless, the signicance of such exchanges may not lie in their capacity to generate short-term economic gains. Chinas moreencompassing goal is to build stable alliances that facilitate growth and inuence over the longer term. As one study of social capital has argued, the currency with which obligations are repaid may be different from that with which they were incurred in the rst place and may be as intangible as the granting of approval or allegiance (Portes, 1998, p. 7). Although some Chinese investments may not register as economic transactions, their signicance should be evaluated in the context of contemporary Latin American politics. Venezuela, Cuba, Bolivia, Nicaragua, and Ecuador are building a trade network called the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas (ALBA), which has proven more successful than the (now abandoned) U.S.-backed Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA). In addition to creating an ALBA Development Bank, the network promotes the exchange and bartering of resources, particularly Venezuelan oil and assistance with debt relief for Cuban doctors, the use of Ecuadorian oil rening facilities, Bolivian coca and soy products, and Nicaraguan meat and dairy. Chinese assistance with physical and human development initiatives ts neatly into this model. Such exchanges may not produce immediate nancial returns, but as Hugo Chvez pointed out during a February 2006 public speech in Havana, their value lies in stable alliances, face-to-face cooperation, direct assistance to poor communities, and long-term economic outcomes. As Chinese inroads into Latin America deepen, the United States must balance its strategic and commercial interests in new ways. Mrozinski, Williams, Kent, & Tyner (2002) point out that, although Latin American resource exports fuel Chinas economic growth, this process serves the interests of U.S. corporations with manufacturing operations in China. The resulting conict of strategic and economic interests was a little-discussed motivating force behind the FTAA negotiations. A crucial component of the FTAA was the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA), whose political merits George W. Bush emphasized when he pushed it through Congress on a combined national security and economic platform (Economist, 2005). Bush said that the political logic behind CAFTA was to shore up democracy in Central America rather than leave it prey to the intervention of foreign socialist governments. Meanwhile, CAFTAs economic logic lies in a value-adding business environment in Latin America that could lure investorsparticularly those from the United Statesaway from China. If CAFTA and some revived variant of the FTAA ever succeed in bringing this about, the conict between U.S. economic and political interests will diminish,

28

Latin American Policy

potentially clearing the way for more-assertive measures from Washington to contain Chinas inuence in the Western Hemisphere. In this context, Chinas commitment to southsouth cooperation takes on broader signicance. It is a commitment that aims at nothing less than simultaneous harmonization with contemporary capitalist and socialist economic regimes. This exibility has proven useful not only for forging relations across the political spectrum, but also for defending against criticism. During his 2005 trip to Washington, Cheng Siwei, vice president of Chinas Permanent Committee of the National Popular Assembly, responded to concerns about his countrys relations with Cuba by stressing economic over political objectives. Dont be sensitive. This is a normal development. Business is business (quoted in Robles, 2005). These comments reveal what Fedderke et al. (1999) might call a dual rationalization of social capital to suit the dominant trends of the global economic climate, providing China with an effective means for integrating politically diverse countries into a cohesive foreign policy framework. It will become increasingly difcult for China to maintain this diplomatic balance as competition for Latin Americas natural resources intensies. The next section describes how Chinas industrial and cultural programs in the region are protecting its resource interests and creating a sociopolitical environment that favors closer economic integration across the political spectrum.

Chinas Local Effects

The U.S. governments geopolitical anxieties are less damaging to China than the broader fear of a growing China threat that has begun to emerge in countries across Latin America. These apprehensions nd historical precedence in the observations of Vladimir Lenin in the early 20th century, Ral Prebisch in the 1950s, and Noam Chomsky since the 1980s that the regions prospects for moving inwards from the periphery of the global market lie in less dependence on resource exports and more attention to educational and technical advancement. Chinese investment in Latin American resources may bring rapid economic growth but does not in itself provide a long-term, sustainable platform for development (Len-Manrquez, 2006, p. 40). With this in mind, Devlin, Estevadeordal, and Rodrguez caution that It is inadvisable for countries simply to allow current market forces (partly triggered by China) to lead them toward specialization in a few traditional sectors (2006, p. 169). Latin Americans have grown accustomed to foreign-managed manufacturing operations, industrial parks, and resource extraction projects that have too often failed to build local technical capacities or create opportunities for domestic businesses (Pritchard & Hearn, 2005; Mesquita Moreira, 2004). It is no coincidence that, according to Latinobarometro, 63% of Latin Americans oppose the privatization of their energy resources (Economist, 2006, p. 42). Concerns about unfair commercial competition and dissatisfaction with labor conditions, wages, industrial insulation, and the practice of bringing in workers from mainland China to replace the local workforce have surfaced in Mexico, Bolivia, Colombia, and Chile. Similar grievances against Chinese enterprises have also emerged in Africa (Faul, 2007).

China and Latin America

29

According to sources in Beijing, China is pursuing a model of development that takes account of the successes and failures of the United States in the region. For Jiang Shixue, former deputy director of the Institute for Latin American Studies at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the key to this approach is a balance between equality and growth and a shared attention to social and economic concerns (personal communication, July 17, 2007). Other Chinese ofcials draw attention to the domestic operations of state-controlled enterprises as an indication of their corporate responsibility. The electronics manufacturer Haier participates in social programs ranging from blood drives to natural disaster relief (Hawes, 2007; Sun Hongbo, personal communication, July 30, 2007). The ability of Chinese enterprises to simultaneously pursue a social and economic agenda results largely from the fact that the government, which according to one prominent Chinese businessman (personal communication, September 20, 2012), funds public welfare in this way to build popular respect for state enterprises while reducing the ofcial size of its budget, controls most of them. It remains to be seen whether Chinese enterprises are concerned enough about public opinion in Latin America to make comparable investments in local welfare. Chinese corporations emphasize or play down their governmental connections depending on political conditions in partner countries. In their Cuban operations, Chinese enterprises publicly advertise the fact that they are state operated as they enter into joint ventures with the Cuban state. Haier and China Putian Corporation dominate the electronics sector of the annual Havana Trade Fair, the latters promotional banner announcing that, China Putian Corporation was founded in 1980. It is an extra-large sized state-owned enterprise directly under the management of [the] Chinese central government . . . China Putian Corporation will regard Cuba as a platform so as to develop is business in Latin America. According to an industrial analyst at the University of Havana, public identication with the Chinese state is intended to inspire condence in corporate responsibility and accountability, qualities that have become harder to prove as imported Chinese textiles and small appliances nd their way into Cubas already expansive informal sector (personal communication, January 10, 2012). By contrast, the advertising campaigns of Chinese companies such as Lenovo in market-oriented Latin American countries do not openly celebrate linkages with the Chinese state.4 This adaptive strategy is an important ingredient in Chinas effort to engage with public and private counterparts and build what Devlin and Estevadeordal (2004) call a trade-cooperation nexus. At the core of this nexus is an awareness that the accrual of social capital over the long term can weigh heavily on the formation of broader industrial and diplomatic relations. A good example of this is a project currently under development by the China National Offshore Oil Corporation with the Venezuelan oil company Petrleos de Venezuela. The project seeks to reduce the reliance of Venezuelas oil sector on the expertise of U.S. rms by building national technical capacities, especially in the manufacture of oil-drilling equipment. A team of 71 Venezuelan technicians and engineers arrived in Beijing in March 2007 to commence its rst phase, which involved technical training and daily Mandarin language and culture classes at Beijing Foreign Studies University.5 In October 2007, the second phase brought the Venezuelans home with a team of Spanishspeaking Chinese technicians to supervise the assembly of drill parts and the

30

Latin American Policy

maintenance of the completed equipment. The third phase, which commenced in mid-2008, saw Venezuela independently building the equipment and putting it into operation. The amount of Venezuelan oil bound for China is increasing (640,000 barrels per day as of mid-2012) and will increase further upon completion of a US$8 billion pipeline stretching 2,000 miles from Venezuelas Caribbean coast to Colombias Pacic coast. Further facilitating the export of Venezuelan oil to China, in 2006, a national referendum in Panama approved a proposal to widen the Panama Canal, an undertaking that began in 2007 and will cost US$5.25 billion over eight years. The China Ocean Shipping Company has publicly endorsed this endeavor, which will allow the canal, whose Pacic and Atlantic port facilities Chinese companies presently control, to accommodate ultralarge crude carriers. Venezuelan oil minister Rafael Ramrez has outlined his goal to increase his countrys oil exports to China to one million barrels per day by 2015, and to this end, China National Petroleum Corporation is working with Petrleos de Venezuela to build three reneries in China (CEG, 2007; Daly, 2012). Although Chinas political agenda may be less explicit than Venezuelas, the collaboration of their oil enterprises forties state-to-state relations in a way that would be unlikely under a free market system. A strictly market-based framework would have trouble accommodating such long-term nancial horizons, investment in language and cultural awareness, and the gradual process of building professional and social ties. Furthermore, as one of the Venezuelan technicians pointed out in Beijing, the focus on technology transfer overcomes a key problem that disadvantaged countries face under global capitalism, namely, that contracted multinational corporations go to great lengths to retain their technical know-how and intellectual property rather than enhance the self-sufciency of potential local competitors. In contrast, as the technician put it, We are emissaries of socialism, and one of the keys to modern socialism is technology transfer (personal communication, June 21, 2007). According to Jianmin Li, deputy secretary general of the China Scholarships Council, direct state-to-state cooperation has allowed China to prioritize educational exchange and capacity-building in priority areas. In 2007, the council funded 12,000 young Chinese to study overseas; 400 of these went to Cuba to study medicine and tourism, a number that doubled in 2008 and has since continued to grow. As Li explained,

Look where the students come from: overwhelmingly from the Western provinces of China, because thats where our central government is trying to develop infrastructure and social programs. So these doctors will return from Cuba to Western China and ll an important need. In the meantime, a signicant number of Cuban doctors are in Western China, lling the need for the short term. (Personal communication, July 5, 2007)

Educational exchange is a central component of the Chinese governments ambitious program of institutional capacity-building, Project 211, and as such has emerged as a key strategic branch of Chinas foreign policy. The China National Offshore Oil Corporation, the China National Petroleum Corporation, and other Chinese oil companies fund Chinas three petroleum universities, which enroll their studentsoften with support from the Ministry of Educationin Latin American universities to learn Spanish and local business culture.

China and Latin America

31

Education programs also serve the broader purpose of reducing anxieties about Chinas perceived threat to the region. A case in point is Mexico, where relations with China are characterized less by cooperation than competition. Manufactured products, such as textiles, appliances, and automobile parts, account for more than 85% of Mexicos exports, but China manufactures the same products at a lower cost and consequently surpassed Mexicos position in the U.S. market in 2002. Competition with China has caused the loss of more than 672,000 Mexican jobs across 12 industrial sectors, with further losses resulting from the abolition of tariffs on shoes and textiles in December 2011. El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama face similar problems and have experienced rising poverty and consequent disappointment with the Washington Consensus, CAFTA notwithstanding (Len-Manrquez, 2006; Villafae & Di Masi, 2002; Villafae & Uscanga, 2000). This situation has driven Mexico to begin emulating the resource-intensive strategies of other Latin American countries by increasing copper and oil production. Industry watchers note the potential of Mexican oil output to rival that of Saudi Arabia but stress the need for investment of some US$20 billion per year to exploit existing elds and explore discoveries such as the deepwater Noxal eld in the Gulf of Mexico (Reuters, 2004; Rueda, 2005). China, the United States, and other countries are lining up to provide this investment, but the efforts of former presidents Felipe Caldern and Vicente Fox to allow foreign companies into the sector met with strong domestic opposition. President Enrique Pea Nieto, inaugurated in December 2012, has faced comparable opposition to this agenda and has already begun to articulate a more conciliatory position endorsing ongoing public control of the sector (Thomson, 2012). Nationalized by the progressive President Lzaro Crdenas in 1938 under the PEMEX Corporation, oil is one of Mexicos only signicant economic resources to remain in national hands through the economic reforms of the past two decades. Public sensitivity about the matter stems largely from Mexicos rather sudden entry into the world market through the 1986 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (Dussel Peters, 2007, p. 20). A combination of competition in manufacturing and pressure to export oil, both resulting largely from the emergence of China, have essentially undermined the benets of industrial upgrading that Mexico achieved in the mid-to-late 20th century. Adding to the bilateral tension, the Confederation of Industrial Chambers has asserted that, for every two manufactured products exported by Mexico, ten enter from China, and that between 900,000 and 1 million workers have lost their jobs (Mural, 2011, p. 4). The informal sector is woven tightly into these indicators, with 60% of clothing sold in Mexico thought to consist of contraband, most of which comes from China (Mayoral Jimnez, 2011; Rodrguez, 2011). Studies conducted in 2012 found that 53% of Mexicans aged 16 to 25 habitually purchase contraband and that the informal sector constituted 15% of GDP (Informador, 2012). According to a Beijing-based representative of Mexicos Tecnolgico de Monterrey, politicians from both countries have sought to improve Mexican perceptions of China and simultaneously accrue political capital by establishing cultural and industrial education programs (personal communication,

32

Latin American Policy

November 3, 2007). Led by the Secretariat of Economic Development of the state of Michoacn, nine Mexican state governments now offer scholarships for students to live in China and study its business practices. Eloy Vargas Arreola, secretary of the Michoacn Secretariat of Economic Development, has urged public optimism, stating that, China, a friend and ally of Mexico, poses no threat (Kai, 2006). To amplify this message, a 2006 bilateral cultural development agreement resulted in the inauguration of Latin Americas rst Confucius Institute in Mexico City. There are currently 190 Confucius Institutes operating in 57 countries (ve in Mexico), and there is a broad range of perceptions of their function. According to Jiang Yandong, director of development and planning at Hanban (the organization responsible for the institutes),

In addition to language teaching we have a cultural mission, which has two parts: the rst is to make people aware of Chinas special kind of socialism, and the second is to teach traditional Asian values through the lessons of Confucius. Our cultural teaching draws on the Confucian texts, whose lessons can be summed up as h wi gi, which means, harmony is the priority.. . . We have to see past the prots before our eyes and instead see the opportunities of the future. (Personal communication, November 17, 2007)

As representatives of the Chinese Ministry of Education, the Confucius Institutes frame educational and cultural exchange within the values of ofcial Chinese political discourse. Confucian principles such as long-term cooperation, ordered harmony, and respect for the autonomy of others reect the geopolitical conditions that the Chinese government considers necessary for global peace and prosperity, as expressed in its foreign policy (PRC, 2004). Responding to accusations that the Confucius Institutes attempt to extend Beijings soft power by recasting Maoist communism in less-threatening terms (e.g., Kurlantzick, 2007; OMF, 2006; York, 2005), Jiang points out that the institutes are only set up when host countries request them.

Although we provide some funding, teachers, and resources, the Institutes belong to the host organization and result from independent applications to set them up. Our objectives may t with those of the Chinese government, but our ofce is made up of different people with different goals from the Communist Party. Were not trying to extend soft power any more than the Goethe Institutes of Germany or the Study Centers of the British Council. Actually, we have one major difference from both of these: our Institutes are always set up collaboratively with local educational institutions, and so from the start they are tied to host country interests. (Personal communication, November 17, 2007)

Although the institutes harbor no specic political objective, the ofcial Chinese news service Peoples Daily acknowledges that they and their associated programs serve to minimize the misconception of [Chinas] development as the China threat by making its traditional value systems known to the world (Peoples Daily, 2006). The hope seems to be that greater cultural familiarity will offset local misunderstandings, suspicions, and fears associated with Chinas growing inuence. This is a timely objective in Mexico, where the terms of trade have disproportionately beneted China, and illicit commerce has damaged the image of both governments. The extent to which education programs will ease

China and Latin America

33

apprehensions and potentially stimulate creative thinking about new forms of ofcial commercial cooperation remains to be seen.

Conclusion

Understanding Chinas multilayered relations with Latin America requires attention to the role of cultural programs, educational exchange, and social capital in building political legitimacy and long-term economic growth. As Nan Lin has written, Social networks and social capital are at the core of the micromacro link. Concepts of power, dependence, solidarity, social contracts, and multilevel systems do not make sense until social capital is brought into consideration (2001, p. 142). Chinas exible approach to international relations is evident in its simultaneous cooperation with politically diverse trading partners, from Cuba and Venezuela to Mexico and the United States. The pursuit of WTO market economy status signals Chinas integration into the capitalist world system, even as it seeks common ground and solidarity with other nonaligned, developing countries. The collaborative programs that underpin this solidarity are similarly mixed, oriented toward economic growth and protability but in most cases developed through direct intergovernmental channels rather than in the private sector. Greater state participation in economic affairs, a longer-term vision of growth, technical training, educational exchange, and industrial upgrading resonate closely with the goals of Latin Americas new left. Countries across the region have begun to show interest in emulating aspects of Chinese market socialism and in rationalizing their domestic systems of governance to facilitate closer integration (Devlin et al., 2006, p. 169; Lu, 2005, p. 40). It is difcult to assess how deep Chinas appeal and inuence in Latin America will run over the course of the early 21st century. As Jorge I. Domnguez put it when the effects of Chinas inuence were beginning to make their mark in the region, The twenty-rst century may or may not be the China century in Latin America but this rst decade of the century surely is the China decade (2006, p. 48). Since then, Chinas effect on Latin America has signicantly deepened and is set to deepen further. The Chinese governments foreign policy commitment to building relationships across the political spectrum, with resource exporters and otherwise, has so far proven hard to resist.

About the Author

Dr. Adrian H. Hearn is an Australian Research Council Future Fellow at the University of Sydney China Studies Centre and Chair of the Latin American Studies Association (LASA) Section for Asia and the Americas. Recent publications include Cuba: Religion, Social Capital, and Development (Duke University Press, 2008) and (as editor) China Engages Latin America: Tracing the Trajectory (Lynne Rienner, 2011).

Notes

An important objective of Chinese foreign policy that falls beyond the scope of this article is its attempt to persuade the 12 Latin American countries (of 23 worldwide) that maintain diplomatic relations with Taiwan to shift their allegiance to the Peoples Republic of China (PRC). A further objective, realized in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Peru during Hu Jintaos 2004 visit, is to become more broadly recognized as a market economy in the WTO.

1

34

Latin American Policy

2 Nicaragua has been comparatively slow to warm to China, but like Panama, the Dominican Republic, and Paraguay, domestic pressure is growing within Nicaragua to cut diplomatic ties with Taiwan (CRS, 2008, p. 19). 3 Empirical examples of this process from across Latin America are presented in Hearn and Len-Manrquez (2011). 4 The Chinese company Legend Holdings is Lenovos largest single stakeholder, with 34% of stock, and the Chinese governments Academy of Sciences owns 36% of Legend Holdings (Lenovo, 2012). 5 This information is from a focus group interview with Venezuelan technicians in Beijing conducted on June 21, 2007. The technicians noted that the project is only a partial solution to dependence on the United States because it will still be necessary to purchase some drill components from the U.S. rm Caterpillar.

References

Arnson, C. J. (2007). Introduction. In C. Arnson & J. R. Perales (Eds.), The New Left and Democratic Governance in Latin America (pp. 39). Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. CEG (China Elections and Governance). (2007). China and Venezuela to sign big oil deals. China Elections and Governance (the Carter Foundation). Retrieved from http://www. chinaelections.org/en/news.asp?classid=83&classname=Sino%2DLatin+Am%2E+Alliance CRS (Congressional Research Service). (2008). Chinas foreign policy and soft power in South America, Asia, and Africa, Committee on Foreign Relations of the United States Senate. Retrieved from http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html Daly, J. (2012). Venezuela ramps up China oil exports unsettling Washington. Retrieved from http://oilprice.com/Energy/Crude-Oil/Venezuela-Ramps-up-China-Oil-Exports-UnsettlingWashington.html Devlin, R., & Estevadeordal, A. (2004). Trade and cooperation: A regional public goods approach. In A. Estevadeordal, B. Frantz, & T. Nguyen (Eds.), Regional public goods: From theory to practice (pp. 155179). Washington, DC: IDB/ADB. Devlin, R., Estevadeordal, A., & Rodrguez, A. (Eds). (2006). The emergence of China: Opportunities and challenges for Latin America and the Caribbean. Cambridge, MA: David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies with the Inter-American Development Bank. Domnguez, J. I., et al. (2006). Chinas relations with Latin America: Shared gains, asymmetric hopes (Working Paper). Washington, DC: The Inter-American Dialogue. Dussel Peters, E. (2007). What does Chinas integration to the world market mean for Latin America? The Mexican experience. Paper presented at the Congress of the Latin American Studies Association, Montral, Canada. Economist. (2005, July 28). Using oil to spread revolution, 376, 3334. Economist. (2006, December 9). Democracy divided, 381, 42. Evans, P. (1996). Government action, social capital and development: Reviewing the evidence on synergy. World Development, 24, 11191132. Faul, M. (2007, February 7). China acknowledges downside in Africa. The Washington Post Online. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/02/08/ AR2007020800981_pf.html Fedderke, J., de Kadt, R., & Luiz, J. (1999). Economic growth and social capital: A critical reection. Theory and Society, 28, 709745. Hawes, C. (2007). Chinas company cultures: Sage insights on doing business with the biggest nation on Earth. UTS Speaks public lecture series, The University of Technology, Sydney. Hearn, A. H. (2008). Cuba: religion, social capital, and development. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Hearn, A. H., & Len-Manrquez, J. L. (2011). China engages Latin America: Tracing the trajectory. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers. Informador. (2012 June 7). La economa informal representa 15% del PIB. Retrieved from www.informador.com.mx/economia/2012/381491/6/la-economia-informal-representa-15-delpib.htm Jiang, S. (2005). South-south cooperation in the age of globalization: recent development of Sino-Latin American relations and its implications (ILAS Working Paper #7). Beijing: Institute of Latin American Studies, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Kai, W. (2006). Breves desde Mxico. China Hoy (China Today). Retrieved from http:// www.chinatoday.com.cn/hoy/2006n/s2006n5/p28.html Kurlantzick, J. (2007). Charm offensive: How Chinas soft power is transforming the world. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

China and Latin America

35

Lam, W. (2004). Chinas encroachment on Americas backyard. China Brief 4, 13. Retrieved from http://www.jamestown.org/publications_details.php?volume_id=395&issue_id=3152&article_ id=2368903 Lenovo. (2012). Investor Fact Sheet. Retrieved from http://www.lenovo.com/ww/lenovo/pdf/ Lenovo-Factsheet-2012-Aug-ENG.pdf Len-Manrquez, J. L. (2006). China y Amrica Latina: Claves para entender una relacin econmica diferenciada. Nueva Sociedad (Buenos Aires) 203, 2847. Lin, N. (2001). Social capital: A theory of social structure and action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Lu, M. (2005, August). China slows down. The Bulletin [Newsweek] 123, 4041. Mayoral Jimnez, I. (2011, December 6). Mxico se blinda por contrabando chino. Retrieved from www.cnnexpansion.com/economia/2011/12/06/mexico-se-blinda-vs-pirateria-de-china Mesquita Moreira, M. (2004). Fear of China: Is there a future for manufacturing in Latin America. Washington, DC: Integration and Regional Programs Department, Inter-American Development Bank. Mural. (2011, December 8). Plantean de nuevo prrroga a apertura. El Mural, p. 4. Murray, M. (2004, November 23). China gives boost to Cubas economy. Retrieved from www.msnbc.msn.com/id/6566988/ Mrozinski, L. G., Williams, T., Kent, R. H., & Tyner, R. D. (2002). Countering Chinas threat to the Western Hemisphere. International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, 15, 195210. OMF (Overseas Missionary Fund). (2006, June/July). Confucius Institutes. China Insight Newsletter. Peoples Daily. (2006). China threat fear countered by culture. Retrieved from http:// english.peopledaily.com.cn/200605/29/eng20060529_269387.html Portes, A. (1998). Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 24, 124. Portes, A., & Sensenbrenner, J. (1993). Embeddedness and immigration: Notes on the social determinants of economic action, American Journal of Sociology, 98, 13201350. PRC (Peoples Republic of China). (2004). Permanent Mission of the Peoples Republic of China to the United Nations Ofce at Geneva and Other International Organizations in Switzerland. Retrieved from http://www.china-un.ch/eng/ljzg/zgwjzc/default.htm Pritchard, B., & Hearn, A. H. (2005). Regulating foreign direct investment: Southeast Asia at the crossroads, Sydney: The Research Institute for Asia and the Pacic in association with the Ministry of Finance of Japan. Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon and Schuster. Reuters. (2004). Mexicos Pemex reports huge new oil nds. http://www.energybulletin.net/ 1803.html Robles, F. (2005, December 24). From the Far East. Miami Herald, p. 1C. Rodrguez, I. (2011). Comercio ilegal acapara mercado de ropa, CNNExpansin. Retrieved from www.cnnexpansion.com/manufactura/2011/01/25/comercio-ilegal-acapara-mercado-de-ropa Rueda, M. (2005, July 1). Slippery slope: despite high oil prices, lack of investment at state-run Pemex means Mexico could soon become a crude importer. Latin Trade. Thomson, A. (2012, December 4). Pea Nieto sets out reform agenda. Financial Times. Retrieved from http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/46d86a20-3e57-11e2-91cb-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2E8 LaIljm Villafae, V. L., & Uscanga, C. (2000). Mexico frente a las grandes regiones del mundo. Mexico: Siglo XXI. Villafae, V. L., & Di Masi, J. (2002). Del TLC al Mercosur: Integracin y diversidad en America Latina. Mexico: Siglo XXI. Woolcock, M. (1998). Social capital and economic development: Toward a theoretical synthesis and policy framework. Theory and Society, 27, 151208. York, G. (2005, September 9). Beijing uses Confucius to lead charm offensive. Globe and Mail. Zweig, D., & Jianhai, B. (2005). Chinas global hunt for energy. Foreign Affairs, 84, 2538.

Você também pode gostar

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Mandate For Leadership Policy RecommendationsDocumento19 páginasMandate For Leadership Policy RecommendationsThe Heritage Foundation77% (31)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- White Mans Burden&CivilizationDocumento103 páginasWhite Mans Burden&CivilizationVijay DhuriAinda não há avaliações

- MindWar (PDFDrive)Documento274 páginasMindWar (PDFDrive)WalterSobchakAinda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Notice of Voluntary Dismissal of SuitDocumento2 páginasNotice of Voluntary Dismissal of SuitBasseemAinda não há avaliações

- Sample Marketing PlanDocumento27 páginasSample Marketing Planme2ubondAinda não há avaliações

- Horia Sima Europe at The CrossroadsDocumento23 páginasHoria Sima Europe at The CrossroadsAnonymous S3wsIptcOAinda não há avaliações

- Food Report CGI Hong KongDocumento84 páginasFood Report CGI Hong Kongmehmetredd100% (1)

- Baldwin (1997) The Concept of SecurityDocumento20 páginasBaldwin (1997) The Concept of SecurityCristina Ioana100% (1)

- The Victorian CompromiseDocumento2 páginasThe Victorian CompromiseRosanna Rolli Anelli50% (2)

- AACOMAS Matriculant Profile: Matriculants and College Designations 2009Documento11 páginasAACOMAS Matriculant Profile: Matriculants and College Designations 2009Tây SơnAinda não há avaliações

- Trace How The Watergate Crisis Brought An End To The Nixon PresidencyDocumento1 páginaTrace How The Watergate Crisis Brought An End To The Nixon PresidencyHaley WordenAinda não há avaliações

- c2d1a2h1amFrMDE5NTQ3MTY3OQ PDFDocumento2 páginasc2d1a2h1amFrMDE5NTQ3MTY3OQ PDFArif SaidAinda não há avaliações

- Backward Design Instructional Planning TemplateDocumento8 páginasBackward Design Instructional Planning TemplateKirstie Savaris100% (4)

- Task1 Writing.Documento15 páginasTask1 Writing.Ánh Ngọc NguyễnAinda não há avaliações

- Mobilizing The Indo-Pacific Infrastructure Response To China S Belt and Road Initiative in Southeast AsiaDocumento15 páginasMobilizing The Indo-Pacific Infrastructure Response To China S Belt and Road Initiative in Southeast AsiaValentina SadchenkoAinda não há avaliações

- JJHI Enrollment ApplicationDocumento1 páginaJJHI Enrollment ApplicationLyric LoveAinda não há avaliações

- Brettenwood SystemDocumento19 páginasBrettenwood SystemPankaj PatilAinda não há avaliações

- GOVT 5th Edition Sidlow Test Bank DownloadDocumento13 páginasGOVT 5th Edition Sidlow Test Bank DownloadBeverly Dow100% (25)

- Private: Managing National ParksDocumento4 páginasPrivate: Managing National ParksAllãn SinclairAinda não há avaliações

- Status and Trends in The Education of Racial and Ethnic Groups 2018Documento228 páginasStatus and Trends in The Education of Racial and Ethnic Groups 2018Paddy Nji KilyAinda não há avaliações

- DNR RegionsDocumento2 páginasDNR RegionsBrad DokkenAinda não há avaliações

- 2012 Mid Term Fiscal Policy ReviewDocumento170 páginas2012 Mid Term Fiscal Policy ReviewgizzarAinda não há avaliações

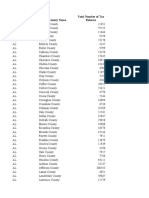

- Tax DataDocumento158 páginasTax Data헤라Ainda não há avaliações

- THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. LOL-LO and SARAW, Defendants-AppellantsDocumento26 páginasTHE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. LOL-LO and SARAW, Defendants-AppellantsKLAinda não há avaliações

- Black People Fight For FreedomDocumento1 páginaBlack People Fight For FreedompaulineoAinda não há avaliações

- Colonialism and Elitism in Philippine Political Development: Assessing The Roots of UnderdevelopmentDocumento34 páginasColonialism and Elitism in Philippine Political Development: Assessing The Roots of UnderdevelopmentPhilip JameroAinda não há avaliações

- New Reading TestDocumento18 páginasNew Reading TestBảo Nghi TrầnAinda não há avaliações

- Unified Strokes, A New Growth Strategy: Annual Report 2011-12Documento92 páginasUnified Strokes, A New Growth Strategy: Annual Report 2011-12Murugan MuthukrishnanAinda não há avaliações

- Kimberly DaCosta Holton - Pride Prejudice and Politics - Performing Portuguese Folklore Amid Newark's Urban RemaissanceDocumento22 páginasKimberly DaCosta Holton - Pride Prejudice and Politics - Performing Portuguese Folklore Amid Newark's Urban RemaissanceC Laura LovinAinda não há avaliações

- Sanitation and Public Health Program in BatangasDocumento12 páginasSanitation and Public Health Program in BatangasGellie Lara BautistaAinda não há avaliações