Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Virtual Heritage

Enviado por

Laura JoannaDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Virtual Heritage

Enviado por

Laura JoannaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

VIRTUAL HERITAGE: REALITY AND CRITICISM

BENG-KIANG TAN, HAFIZUR RAHAMAN

Department of Architecture, School of Design and Environment, National University of Singapore, Singapore

abstract: Virtual environments which are culturally embedded are often categorized as virtual heritage. Emerging media and digital tools offer us the possibility to experience 3D virtually reconstructed historic sites as visitors, travelers or even as resident. Many critics have identified different issues that often inhibit widespread distribution and use of virtual heritage. However, these present criticisms are mostly focused on either the process or the product but do not consider user, i.e. the people using it. This paper attempts to identify and categorize various constraints through investigating present discourse of literature and presents user as another inevitable factor to be considered for developing any virtual heritage environment. keywords: Virtual heritage, virtual environment, dissemination, user, interpretation

rsum : Les environnements virtuels qui sont culturellement imprgns sont souvent catgoriss en tant que patrimoine virtuel. Les mdias mergents et les outils numriques nous offrent la possibilit de vivre, en tant que visiteurs, voyageurs, voire comme rsidants, des sites historiques reconstitus en 3D. Plusieurs critiques ont identifi diffrents aspects qui souvent empchent une large diffusion et un usage de patrimoines virtuels. Cependant, ces critiques portent en gnral soit sur le processus, soit le produit mais ne considrent pas lusager, cest--dire celui qui en fait usage. Cet article tente didentifier et de catgoriser une varit de contraintes travers ltude de discours littraires actuels et de lusager comme facteur invitable considrer pour le dveloppement de tout environnement patrimonial virtuel. mots-cls : Patrimoine virtuel, environnement virtuel, diffusion, usager, interprtation

T. Tidafi and T. Dorta (eds) Joining Languages, Cultures and Visions: CAADFutures 2009 pum, 2009

144

b.k. tan h. rahaman

1. INTRODUCTION

Virtual environments which are embedded with cultural heritage and represented through digital media are often categorized as virtual heritage. In present day, new media and digital tools offer us the possibility to experience virtually reconstructed historic sites or virtual heritage sites as visitors, travelers or even as a resident. Although virtual heritage poses great potential to reconstruct our past heritage and memory, many critics often blame high cost, development complexity, inaccessibility of technology, complexity in usability and high maintenance for prohibiting widespread dissemination, distribution and use of virtual heritage media. Some authors have also identified different weakness within the interface and delivered contents. This study argues that, these present criticism are mostly focused either on process or product of developing virtual heritage; but do not consider user i.e. people using it, as another factor. That is why in most cases virtual heritage contents are developed with an ocular-centric tendency. As the sense of perception is subjective, it seems that content without relating directly to how a viewer perceive the virtual world, does not create any meaning. Rather it works as a storehouse of visually presented objects. As a result viewers thus fail to understand the inherent significance of heritage which is not always immediately or visually apparent from a virtual heritage site. This paper investigates present discourse to identify and categorize various constraints mentioned by different authors and also present some new issues that need to be considered in designing virtual heritage environment. The authors hope that this paper will help researchers and designers understand the present problems in developing a more engaging, entertaining and popular virtual heritage environment.

2. VIRTUAL HERITAGE AND ITS DOMAINS 2.1. Definitions

The broad term heritage refers to the study of human activity not only through the recovery of remains, as is the case with archaeology, but also through tradition, art and cultural evidences, and narratives. On the other hand virtual heritage (VH) is a term use to describe works that deals with virtual-reality (VR) and cultural-heritage (Roussou 2002). In general, virtual heritage and cultural heritage have independent meanings: cultural heritage refers to properties and sites with archaeological, aesthetic and historical value and virtual heritage refers to instances of these properties and sites within a technological domain. To virtualize heritage means to actualize the heritage content digitally and to simulate it using computer graphics technology. According to Roussou

Virtual heritage: Reality and criticism

145

(2002), the functions of virtual heritage are to facilitate the synthesis, conservation, reproduction, representation, digital reprocessing, and display of cultural evidence with the use of advances in VR imaging technology. Some scholars also described virtual heritage as a vehicle for preservation, access and economic development at the service of archaeological remains valued for their artistic qualities. The representation of landscapes, objects, or sites of the past and the overall process of visualization of archaeological data with the use of VR technology form a sub-domain known as Virtual Archaeology (Barcel 2000). Some extended form of VR technology mixed with real-world known as Mixed Reality and Augmented Reality have also been applied in experiencing archaeology and heritage. These applications are frequently identified with the reconstruction of ancient sites in the form of reproducing accurate 3D models (Valtolina et al. 2005; Yang et al. 2006).

2.2. Domains of virtual heritage

Digital tools and techniques now emerging from academic, government and industry labs offer new hope to the often painstakingly complex tasks of archaeology, surveying, historic research, conversation and education (Addison 2000). The increasing development of VR technologies, interfaces, interaction techniques and devices has greatly improve the efficacy and usability of VR, providing more natural and obvious modes of interaction and motivational elements. This has helped institutions of informal education, such as museums, media research and cultural centers to embrace advanced virtual technologies and support their transaction from the research laboratory to the public realm.

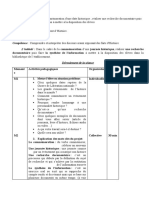

figure 1. basic domains of virtual heritage.

146

b.k. tan h. rahaman

According to Addison (2000) there are three major domains in virtual heritage:

3D Documentation: everything from site survey to epigraphy 3D Representation: from historic reconstruction to visualization 3D Dissemination: from immersive networked worlds to in-situ augmented reality.

Figure 1 explains the present method of developing and disseminating virtual heritage. The first stage is all about finding information, analysis and documenting the authentic data from both cultural and architectural past. The next stage is for representation which is conditioned by media and only supports (at this time) the tangible heritage and mostly focused on accuracy of visualization. The final stage is devoted to distributing these information and knowledge to general public by means of interactive digital media, which can vary from in-situ, internet or independent installation based distribution.

3. PRESENT CRITICISMS OF VIRTUAL HERITAGE

Virtual reconstructions are mostly developed by researchers and academicians (excluding movie industries for entertainment) requiring extensive labor and high expertise. However, the end product (3D models/environment) remains within the domain of scholars and academia. A few of them are merely published in websites or open to public spaces like museums. Because present VR technologies pose a variety of practical limitations, such as, high cost, development complexity, inaccessibility of immersive VR technologies, intricacy in usability and high maintenance, it is restricting the ability of virtual heritage to serve the needs of a commercially produced mass entertainment industry (Roussou 2008). So far, from literature review the following short-comings have been identified.

3.1. Lack of meaningful and cultural content

Some authors have blamed todays virtual worlds as static and lifeless (Addison 2000). Other authors have identified other weakness such as lack of engagement, lack of realism, lack of meaningful content, confusing interface design, orientation and navigation difficulties and a paucity of useful feedback mechanism (Champion 2002; Costalli et al. 2001; Economou and Tost 2008). Even when photorealistic architecture reconstructions are found to be very impressive, they lack dynamic elements such as virtual humans or animals (Yang et al. 2006), rain, wind and fog in most cases. An architectural heritage is something more than a physical form. A building is a place for doing different activities, especially spaces inside a cultural or

Virtual heritage: Reality and criticism

147

religious building house rituals and performances. To understand the architecture of these monuments, mere virtual reconstruction of the three dimensional form may not be sufficient. Some present discourse of Yehuda E Kalay (2008) and Bharat Dave (2008) criticized virtual heritage for being limited to accumulating only tangible/formal aspects of heritage; and blamed for not permitting to hold the expected cultural heritage contents.

3.2. Conclusive process: lack of later interpretation

Most historic architecture is dynamic and has gone through different phases of changes and development. So, for reconstruction there is always a big question about selection of specific time period to present. For example, the construction process of the Chartres Cathedral lasted over thirty years. Unlike a painting, which the painter can varnish once he has completed it, a historical building is alive and never completes (Dave 1998). As a result the typological, temporal, material and historical aspects of architecture do not lend them to become an isolated geometric representation. Dave (1998) has referred to this issue of virtual reconstruction process and advised it should be an evolving commentary of arguments or interpretations rather than conclusive documents. However, the process of virtual reconstruction (Figure 1) expresses the truth of rigidness and one-way data flow. Documentation stage is always concerned about authentication of data; representation stage is aimed at accuracy, while dissemination stage focuses on showing its mastery of technology. Most of the reconstruction projects do not permit later interpretation or update. This one-way process is always criticized by many authors and often advised (Dave 1998) to go beyond creating introverted and closed historical reconstruction projects.

3.3. Lack of engagement

There are two types of VR exploration:

First person control (user can control the view and path according to will) Guided tour (passive observer watching predefined animation or guided by curator or PDA)

Except some new developments like Forbidden City project (http://www. beyondspaceandtime.org), most of the virtual heritage environments are designed with a minimum opportunity of active participation from users. Even if the viewing control is given to the user, rarely is there a role for visitor to play or to perform any action or task that is not predefined. Mosaker (2001) blamed present virtual heritage environments for lack of thematic interactivity. This

148

b.k. tan h. rahaman

means users can move around inside the environment without any certain goal or objective in mind, which sometimes make them lost and bored. On the other hand interactivity has made many computer games so popular and engaging which may be followed in virtual heritage environments too (Eiteljorg 1998, Laurel et al. 1994 in Champion and Dave 2002). A study on user-experience by Tost and Champion (2007) on three virtual heritage projects (i) Building virtual Rome (ii) Ename Museum and (iii) The Palenque, have found that engagement is very important for a entertaining and learning experience and also a major factor to determine the success of the project.

3.4. Lack of sense of place

Critics often blame virtual environments (VE) for evoking cyberspaces but not place. In other words VE always lack richness of association and affordances, and limits the personalization of spaces. Lidunn Mosaker (2001) surveyed visitors with two virtual heritage projects made by Hellenic Worlds and Nu.M.E. (Nuovo Museo Elettronico) and observed that most of the users do not know about the details of the ancient architecture styles and are not fascinated by the environment. His findings showed that visitors are more interested in the human part of the city life, which is something they can actually relate to but not with the built forms. Perfectly designed virtual buildings, columns, details and cornices do not mean anything to them; they only gave a sterile impression to visitors. Weckstorm (Weckstrm 2004) who studied a group of students exploring some virtual worlds (simulators, chat rooms, games, including flight simulators 2004, TRANSIMS visualize, Habbo Hotel, The Sims Online and Ever Quest), found the experience of the participants as empty and hollow, like stage sets. In most cases visitors found very neat buildings but they failed to understand the purpose or use of those buildings. As a result those students concluded their experience as just architectural spaces without any feeling of worldliness. Some attempts were made to overcome this issue in the Forbidden City project, where users can meet virtual avatars and perform activities with them. These experiments showed that user experience more than tangible objects. Solid and immutable objects are easier to conceptualize and model but this does not fully constitute reality to us because the real world consists of many intangible associations, values, social behavior and mental states which gives us the sense of place and realness. Also virtual environments typically have less annotation ability with the exception of 2nd Life and Forbidden City. They are mostly built for single-user and can only allow seeing others; sharing information is limited to chat, send-

Virtual heritage: Reality and criticism

149

ing files or hyperlinks. Some recent VE allows users to buy and sell goods or gamble but are mostly very limited for other different social interactions.

3.5. Technological limitation 3.5.1. Technical artistry and power of new technology

Present trends in virtual heritage mostly demonstrate the technical artistry and power of new technology (Tost and Champion 2007). The advancement of digital media technology holds great potential for photo-realistic reconstruction of heritage and monuments and culturally significant places. In order to approach visual fidelity and accurate reproduction of real and historical environment, computer visualizations have focused on reducing technical limitations to attain a degree of reality. Rossou et al. (2003) considered this technological development and pointed out photorealism as one of the most important issue to measure successfulness in representation for a virtual reconstruction site. However, this love of technology may lead us towards the amorphous nature of history. According to Champion (2004), the notion of photorealism often suggests an authoritative knowledge of the culture that the authors or designers in fact may not possess.

3.5.2. Lack of widely distributed technology

In recent days rapid advances in digital media and virtual reality technologies offer new hopes for virtual heritage. The potential of Head Mounted Displays (HMD), Computer Audio Visual Environment (CAVE) technologies, Single Wall Projection Displays / Powerwalls, WorkBenches, Fish Tank VRs and WIMPs (windows, icons, menus, pointing) has opened the new possibilities of exploring virtual heritage. Most of these technologies aim to support an immersive environment for the user. However some of these approaches suffer from disadvantages. For example, the use of HMD can cause nausea, disorientation and other motion sickness and secondly it does not encourage communication between users and is isolated from the real world. In some cases a semi-immersive approach is developed, but in most cases these technologies are often criticized for their high cost, maintenance, operation, hardware and usability. Even though there are some online environments and 3D chat rooms in the web, they are mostly restricted to certain type of operating systems, browser, graphics-card and bandwidth. There are also open platform applications, such as, Metastream, Blender 3D, Blassun and Crystal Space, but we cannot rely on them being around, for example, Adobe closed their 3D environment builder application Adobe Atmosphere. Web based 3D technology companies appear and disappear frequently and cannot be relied on (Champion 2006).

150

b.k. tan h. rahaman

3.6. Lacking positive attitude of wide dissemination, distribution and use

Virtual heritage by definition means to actualize it digitally and to simulate it by using computer technology. In general, virtual heritage/archaeology refers to the use of three dimensional computer models of ancient buildings and artifacts visualized through digital technologies that offer some degree of immersion and or interaction with the content. Virtual heritage content can be delivered through internet, museum, public display or other means like PDA, handhelds and so on. Each media has its own potentials and constraints. Print media is mostly static and non-interactive and VR environments can be viewed real-time through PC monitors but internet broadband is not available to most of the people in the world. As a consequence, memory preserving institutions such as museum and public libraries are in a position to take the responsibility to host such services and disseminate the knowledge of history to general public. However, Fiona Cameron (2008) has brought up the present debates on the meaning and relationship between historical collections and digital historical objects in the light of materialculture paradigm and object-centeredness of museum culture. According to Cameron, digital objects are always being judged from the standpoint of the superior physical counterpart. Physical object carries the essence of aura, evidence, the passage of time, the signs of the power through accumulation, authority, knowledge, and privilege. Digital media on the other hand, is considered as immediate, surface, temporary, modern, popular and democratic (Witcomb 2008). So mass dissemination of virtual heritage in this sector is less admired as some authorities considered digital media as a threat for loss of aura, loss of ability to distinguish between real and copy, reduction of knowledge to information and finally loss of institutional authorship.

4. Understanding the end-user

In a virtual heritage environment while people are interacting with the system/ interface, they are primary interacting with information. Accordingly to Precce et al. (1993) Peoples objective in using the machine is to carry out a task in which information is accessed, manipulated or created. The computer and peripheral devices are the means through which this objective is achieved. In cognitive psychology the way we come with some selection is regarded as a series of information processing steps. The stages involved in human information processing are explained in Figure 2.

Virtual heritage: Reality and criticism

151

figure 2. stages involved in human information processing (adapted from jenny preece 1993).

Encoding information + Developing Internal representation Compare with previous representation Deciding appropriate response

Action

Again, a person certainly inherits a specific cultural, technical and cognitive background, which is unique from others. According to cognitive psychology this information processing activity depends on capabilities (visual perception, attention, memory, learning and mental model) of the users mental process (Preece et al. 1993).

figure 3. relationship between people and virtual heritage.

Figure 3 shows that experience and learning from the existing or offered content depends largely on both media (ChanLin 2001; Osberg 1997; Roussou 2008) and viewers (physical and psychological) background. The issues related to media are cost, software, hardware (HMD, CAVE etc.) and narrative. On the other hand, the user background and cognition part directly relate to the physical aspects such as age, gender and cultural aspects such as social background, sense of perception, technical knowledge, ideology, learning ability and interest. Both of these criteria influence directly how a viewer reacts and interprets the content. So, it can be argued that within the field of virtual heritage there is a lack of literature focused on the theory and methodology of user interaction and interpretation of heritage. This implies that most of the designers follow the common pattern of descriptive interpretation of content developmentan approach to visually describe the physical appearance of heritage in its digital form. As virtual heritage deals with cultural artifacts, demographic differences always influence users on value judgment; as well as task accomplishment in any virtual heritage environment. What we see our concept-oriented brain tells us about it. Not only through our eyes but also our previous experiences filter

152

b.k. tan h. rahaman

the reality as soon as our brain has received it. It seems that without content relating directly to how we perceive the world, virtual heritage does not create reality for us but becomes a storehouse of visually presented object (Preece et al. 1993). In most of the virtual environment, a user can move, accomplish task (e.g Palenque project), walk or fly (e.g. Nu.M.E), even sometimes re-arrange or construct blocks (e.g. CREATE), but there are no options open for end users to either manipulate or customize the interface or change the predefined way of interpreting the information or even contribute in the reconstruction process. In this circumstance a viewer faces some degree of lack of association and engagement because:

(i) Users feel being imposed, guided and restricted in their individuality and freedom of acquiring knowledge from the content. (ii) As each visitor/user has their own cultural background, so different cultural objects pose different meaning to each person. An artifact that may be very important to one may not be for another user. So the intended interpretation may not occur.

Janice Affleck (2006) also identified this problem and tried to investigate in a web portal dedicated for participatory online interpretation of heritage content among a virtual community. The site was mostly limited to manipulate content (text, photographs and audio-visual) and some sort of personal interpretation. But the project lived for only six weeks and there was no active role-play option for the user and the interpretation approach was mostly contributive rather than explorative.

5. APPROACHING THE PROBLEM

In most cases 3D environments are typically reproductions/reconstructions of archaeological sites or monuments. These virtual environments help to visualize 3D objects/spaces but rarely convey cultural meanings. In other words the cultural value of digital cultural data is not intrinsic, nor is it implicit in their 3D visualization (Bonini 2008). It is very important to know how a digital object can express cultural value and at the same time that value is perceived by the viewer. So, in virtual heritage projects, digitalized artifacts somehow need to trigger the users cognitive process while he is exploring the virtual environment, otherwise the artifacts will become meaningless visual objects to us. While developing a virtual heritage environment we need to consider two important basic things:

(a) Content development: Technology always has some constrains with hardware and software; as well as connected to an image of practice. Media experts like: modelers, animators, programmers may know how to do

Virtual heritage: Reality and criticism

153

something, but may not be aware of the implicit cultural values of a particular artifacts or environment. So, while working as a cultural preservationist, the implemented methods or approaches reflects their own assumptions and may not be appropriate (Kalay 2008). (b) User interpretation: Virtual environment allows more freedom and authority. Freedom in walkthrough and time-travel allows open-ended sequences of expedition. Such freedom on the other hand may become temporally, as well as spatially confused and to some extent result in getting lost in some ancient and unknown world. So, effort should be given to contextualize the experience and set the mood for its understanding (Kalay 2008). A virtual environment thus need to become a context where multiple and diverse cultural experiences may occur at different levels for different users (from layman to expert) according to their level of interpretation.

Copeland (1998, 2004) suggested a constructivist approach for interpretation in an archaeological site. It is an approach of interpretation based on learning by doing through problem solving. Copeland explained the implication of constructivist approach as the way that individuals are constantly constructing meaning by their own thought, feeling, actions, negotiation and reaction with the world. Thus constructivist interpretation seeks to engage visitors with evidence and help them to construct their own meaning. Again, a considerable amount of literature has argued that interactive engagement in a computer medium is best demonstrated by games (Schroeder 1996; Prensky 2001; Champion et al. 2003). Serious game by definition provides the platform for learning and entertainment. Considering this opportunity certain techniques of game play and game design can be adopted in developing virtual heritage environment. Finally in a virtual environment, interaction possibilities are the basic/core of promoting sense of place and experience. Interaction in a virtual environment builds meaning to a user which depends on situated action, embodied interaction and the cognition process valued by the cultural or social background of the user. The sense of presence can therefore support the acquisition of knowledge. Adapting the concept of Hermeneutic virtual environment by Champion and Dave (2002) which claim to be more culturally coded and inhabitable, together with constructivist interpretation and game based interaction mentioned above, we propose a new conceptual framework (Figure 4). We believe this framework can provide a more interpretive, engaging and culturally rich virtual environment which may be successfully implemented for virtual heritage projects.

154

b.k. tan h. rahaman

figure 4. propose framework for a more interpretive virtual heritage environment.

6. CONCLUSION

Virtual heritage as a discipline is still in its infancy and development. This paper argues that the criticisms and debates are mostly directed at process (authentication of data, site survey to epigraphy) or product (representing closer to reality and presentation of technical artistry) but do not consider user (endusers perception of the content). Humans are cultural beings and their demographic and cultural backgrounds differ from each other. Perception, reaction or even interpretation is therefore subjective. So, while developing the content, consideration should be given to understanding the user group and allowing them to explore non-linear open-ended interpretative way for a better participative and learning environment. Our ongoing research aims to develop the conceptual framework proposed in Figure 4 for a more effective interpretation method of virtual heritage where the meaning of interpretation will be open ended and opposite from a descriptive, linear process. Thus the research will help to minimize the distance between end-user and heritage through effective interaction with the content and optimize understanding and learning from the delivered content.

REFERENCES

Addison, A.C., 2000, Emerging Trends in Virtual Heritage, IEEE Multimedia, 7: 22-25. Affleck, J. and Kvan, T., 2006, Reconstructing Virtual Heritage: Participatory Interpretation of Cultural Heritage through New Media, in T. Kvan and Y. Kalay (eds), New Heritage Conference: Beyond Verisimilitude; Interpretation of Cultural Heritage through New Media, Faculty of Architecture, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, pp. 82-93. Barcel, J.A., 2000, Visualizing What Might Be. An Introduction to Virtual Reality in Archaeology, Virtual Reality in Archaeology, 843: 9-36.

Virtual heritage: Reality and criticism

155

Bonini, E., 2008, Building Virtual Cultural Heritage Environments: The Embodied Mind at the Core of the Learning Processes, International Journal of Digital Culture and Electronic Tourism, 1: 113-125. Cameron, F., 2008, Beyond the Cult of the Replicant : Museums and Historical Digital Objects - Traditional Concerns, New Discourses, in New Heritage: New Media and Cultural Heritage, London and New York: Routledge-Taylor and Francis Group., pp. 49-71. Champion, E., 2002, Cultural Engagement in Virtual Heritage Environments with Inbuilt Interactive Evaluation Mechanisms, in Proceedings of the Fifth Annual International Workshop, PRESENCE. Champion, E., 2004, The Limits of Realism in Architectural Visualization, in Proceedings of the XXIst Annual Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians Australia and New Zealand (SAHANZ), 26-29 September, Melbourne, <http://sahanz04.tce.rmit.edu.au/>. Champion, E. and Dave, B., 2002, Where is this place?, in Proceedings of 22st Annual Conference ACADIA 2002: Thresholds Between Physical and Virtual, 24-27 October, Cal Poly Pomona, CA, pp. 87-97. Champion, E.M., 2006, Evaluating Cultural Learning in Virtual Environments, PhD thesis, Department of Geomatics, Faculty of Engineering and the Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning, Melbourne, The University of Melbourne. ChanLin, L., 2001, Formats and Prior Knowledge on Learning in a Computer-Based Lesson, Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 17: 409-19. Copeland, T., 1998, Constructing History: All our Yesterdays, Teaching the Primary Curriculum for Constructive Learning, 119. Copeland, T., 2004, Presenting Archaeology to the Public : Constructing Insights On-Site, in N. Merriman (ed.), Public Archaeology, London, New York, Routledge, pp.132-144. Costalli, F., Marucci, L. et al., 2001, Design Criteria for Usable Web-Accessible Virtual Environments, in the Proceedings of International Cultural Heritage Informatics Meeting: ichom01, Milan, ichim, pp. 413-26 Dave, B., 1998, Bits of heritage, in Proceeding of Virtual Systems and Multimedia: Future Fusion, The Netherlands, IOS Press, pp. 250-55 Dave, B., 2008, Virtual Heritage: Mediating Space, Time and Perspectives, in Y.E. Kalay, T. Kvan and J. Affleck (eds), New heritage: New Media and Cultural Heritage, New York, Routledge, pp. 40-52 Economou, M. and Tost, L.P., 2008, Educational Tool or Expensive Toy? Evaluating VR Evaluation and its Relevance for Virtual Heritage, in New heritage: New Media and Cultural Heritage, London and New York, Routledge-Taylor and Francis Group, pp. 242-60. Kalay, Y.E., 2008, Preserving Cultural Heritage through Digital Media, in New Heritage: New Media and Cultural Heritage, New York, Routledge, pp. 01-10 Mosaker, L., 2001, Visualising Historical Knowledge Using Virtual Reality Technology, Digital Creativity, 12: 15-25. Osberg, K.M., 1997, Constructivism in Practice: The Case for Meaning-Making in the Virtual Vorld, PhD Thesis, Department of Education, Seattle, University of Washington, <ftp:// ftp.hitl.washington.edu/pub/publications/r-97-47/osberg.rtf> accessed: 28th September 2008. Preece, J., Benyon, D., Davies, G., Keller, L. and Rogers, R. (eds), 1993, A Guide to Usability: Human Factors in Computing, Wokingham, England; Reading, MA, Addison-Wesley. Prensky, M., 2001, Digital Game-Based Learning, New York, McGraw-Hill.

156

b.k. tan h. rahaman

Roussou, M., 2002, Virtual Heritage: From the Research Lab to the Broad Public, Virtual Archaeology, 93-100. Roussou, M., 2008, The Components of Engagement in Virtual Heritage Environments, in New Heritage: New Media and Cultural Heritage, London and New York, RoutledgeTaylor and Francis Group, pp. 225-41 Roussou, M., Drettakis, G., Reche, A. and Tsingos, N., 2003, Photorealism and Non-Photorealism in Virtual Heritage Representation, VAST 2003 and First Eurographics Workshop on Graphics and Cultural Heritage. Schroeder, R., 1996, Possible Worlds: The Social Dynamic of Virtual Reality Technology Boulder, CO, Westview Press. Tost, L.P. and Champion, E.M., 2007, A Critical Examination of Presence Applied to Cultural Heritage, in The 10th Annual International Workshop on Presence , Barcelona, 25-27 October, pp. 245-56, <http://www.temple.edu/ispr/prev_conferences/proceedings/2007/Tost%20and%20 Champion.pdf>. Valtolina, S., Franzoni, S., Mazzoleni, P. and Bertino, E., 2005, Dissemination of Cultural Heritage Content through Virtual Reality and Multimedia Techniques: A Case Study, in Proceeding of the 11th International Multimedia Modelling Conference (MMM 2005). <www.archimuse.com/mw2007/papers/>. Weckstrm, N., 2004, Finding Reality, in Virtual Environments, Unpublished Masters Thesis, Arcada Polytechnic: Helsingfors/Esbo. Witcomb, A., 2008, The Materiality of Virtual Technologies: A New Approach to Thinking about the Impact of Multimedia in Museums, in New Heritage: New Media and Cultural heritage, London and New York, Routledge-Taylor and Francis Group, pp. 34-48 Yang, C., Peng, D. and Sun, S., 2006, Creating a Virtual Activity for the Intangible Culture Heritage, in 16th International Conference on Artificial Reality and Telexistence-Workshops, ICAT06, pp. 636-41.

Você também pode gostar

- Administrateur Messagerie 4645 PDFDocumento52 páginasAdministrateur Messagerie 4645 PDFtipowaAinda não há avaliações

- TDR Agence - de CommunicationDocumento4 páginasTDR Agence - de CommunicationDalila AmmarAinda não há avaliações

- Editions Esprit Esprit: This Content Downloaded From 139.124.244.81 On Tue, 30 Nov 2021 10:54:32 UTCDocumento9 páginasEditions Esprit Esprit: This Content Downloaded From 139.124.244.81 On Tue, 30 Nov 2021 10:54:32 UTCBou-laouz IkramAinda não há avaliações

- 3as Lancement Texte DhistoireDocumento2 páginas3as Lancement Texte DhistoirelilyaAinda não há avaliações

- Couple Conscience Et Sexualite ExperimentaleDocumento279 páginasCouple Conscience Et Sexualite ExperimentaleDeaSahiAinda não há avaliações

- Methodologie Projet Action Appui ParentaliteDocumento6 páginasMethodologie Projet Action Appui ParentalitepapitoloveAinda não há avaliações

- Mécanisme de La PersuasionDocumento22 páginasMécanisme de La PersuasionAboubacar Doucouré100% (1)

- DSCG Management Des Systemes D Information 2013Documento10 páginasDSCG Management Des Systemes D Information 2013francoisabj2004Ainda não há avaliações

- Cursan 1 PsihoDocumento56 páginasCursan 1 Psihodragonul811Ainda não há avaliações

- 01 IntroductionDocumento20 páginas01 IntroductionsuramosAinda não há avaliações

- Cours - EL ARAFI - FL - MAster - FPF - S2 - MARS20 - FRDocumento80 páginasCours - EL ARAFI - FL - MAster - FPF - S2 - MARS20 - FRfatiha el yaakoubiAinda não há avaliações

- Annexe 6 - Plan de Com Du PNDDocumento56 páginasAnnexe 6 - Plan de Com Du PNDdieuvalgmAinda não há avaliações

- Ig Riskmanagement HighresDocumento1 páginaIg Riskmanagement Highreslycée ibnrochdAinda não há avaliações

- Module 01 Metier Et Formation BTP TCCTPDocumento55 páginasModule 01 Metier Et Formation BTP TCCTPcondicteur.carlosAinda não há avaliações

- L - Audit Des Regions MarocainesDocumento43 páginasL - Audit Des Regions Marocainesنبيل بربيب100% (1)

- Perspective Historique de L'intelligence EconomiqueDocumento17 páginasPerspective Historique de L'intelligence EconomiqueMavoungouAinda não há avaliações

- AUDIT FINANCIER CompletDocumento143 páginasAUDIT FINANCIER CompletIhsane LakhdarAinda não há avaliações

- Le Langage Corporel Decouvrez Ces Gestes Qui Vous Trahissent Comprendre La Communication Non Verbale Et Savoir Decoder Les. ANNA DAVIDDocumento127 páginasLe Langage Corporel Decouvrez Ces Gestes Qui Vous Trahissent Comprendre La Communication Non Verbale Et Savoir Decoder Les. ANNA DAVIDGuaran TekAinda não há avaliações

- Veille InformationnelleDocumento29 páginasVeille Informationnelledcg dcgAinda não há avaliações

- Questions ÉconomieDocumento2 páginasQuestions Économieun big oiseauAinda não há avaliações

- LE POINT DE BASCULE Résumé - Malcolm GladwellDocumento29 páginasLE POINT DE BASCULE Résumé - Malcolm GladwellChouchouAinda não há avaliações

- ST-DIRPR09-Procédure-Gestion Documentaite-V1.0Documento12 páginasST-DIRPR09-Procédure-Gestion Documentaite-V1.0babaAinda não há avaliações

- Transparence de La Gestion Fiscale A Travers LaDocumento54 páginasTransparence de La Gestion Fiscale A Travers Lasoukaina100% (1)

- Rapport Final Du Stage CD SARA FELHANEDocumento107 páginasRapport Final Du Stage CD SARA FELHANEabd100% (1)

- Cours Audit Operationnel 2014-2015 1Documento25 páginasCours Audit Operationnel 2014-2015 1AliAinda não há avaliações

- Avant Projet préléminaireDocumento5 páginasAvant Projet préléminaireferielbenmalek09Ainda não há avaliações

- These Danielle AttiasDocumento232 páginasThese Danielle AttiasFabrice100% (1)

- Thèse - Systeme D'informationDocumento158 páginasThèse - Systeme D'informationouafae jowharAinda não há avaliações

- Chap HGGSPDocumento5 páginasChap HGGSPaillard.pierrickAinda não há avaliações

- Memoire Final Corrigé 2Documento110 páginasMemoire Final Corrigé 2Safia Boubacar100% (2)