Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Notes On Tamil Family Writer PDF

Enviado por

Thangapandian NTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Notes On Tamil Family Writer PDF

Enviado por

Thangapandian NDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Review Essay

Sujata Sriram

Tata Institute of Social Sciences, India

Nandita Chaudhary

Lady Irwin College, University of Delhi, India

An Ethnography of Love in a Tamil Family

Trawick, Margaret, Notes on Love in a Tamil Family. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990. 320 pp. ISBN 0520078942 (pbk). If you visit Dr. Margaret Trawicks home page at the University of Massey, New Zealand, there are two photographs on display. One is of Trawick herself. The other is a photograph of one of the primary respondents in her study on love in a Tamil family. The inscription below that photograph reads In Memory of Pullavar S.R. Themozhiyar, 19381998. Trawick lived with Themozhiyars family and used them as sources for her book Notes on Love in a Tamil Family. The book was researched in three phases, in 1975, 1980 and then in 1984. First published in 1990, the book was awarded the 1992 Coomaraswamy award for signicant scholarly work on South Asia. Oxford University Press, India brought out an Indian edition in 1996. Trawicks meeting with Themozhiyar, or Ayya, as he is also known in the book, was a serendipitous one. She was in Tamil Nadu researching concepts of the human body in South India. Ayya was introduced to her as a Tamil scholar who made his living by lecturing at religious gatherings about Saiva literature (p. 41). Ayya introduced Trawick to the epic poem Tirukkovaiyar by Manikkavacakar. This was a love poem, which talked of the love of a man and a woman, and also spoke of the

Culture & Psychology Copyright 2004 SAGE Publications (London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi) www.sagepublications.com Vol. 10(1): 111127 [DOI: 10.1177/1354067X04040933]

Culture & Psychology 10(1)

various exploits of Lord Siva. The poem was replete with metonymy and metaphor. It was in the course of translating the epic that Trawick met the various members of Ayyas extended family. The translation of the poem gave Trawick access to the linkages between the worlds of divinity, poetry and real life. She recognized that there could be no one translation of the poem; the degree of metaphor and metonymy allowed for a plurality of meanings, which echoed real life.

Trawicks Method

When Trawick visited Tamil Nadu and lived with Ayyas family, it was not with the intention of studying love and its diverse expressions in India. Her primary interest was Tamil poetry and how it related to everyday life. By her own account, Trawick visited India three times. She lived with Ayyas family for extended periods of time, along with her husband and sons. In addition, she carried out open-ended interviews with 150 other respondents to supplement the ndings from Ayyas family Trawick was not dependent on an interpreter to translate the responses of her respondents. It is possible that this was one of the factors that allowed for the integration of Trawick into the family. Her familiarity with Tamil would also have helped her understand the nuances emerging from the discourse that she observed and was involved in. As Trawick says (speaking of Ayyas inability to communicate with others when he visited America, so that she acted as interpreter), I learned the powers of an interpreter, then, and was glad I never had one in India. The temptation to edit things people said to each other was sometimes very great (p. 21). It is precisely this feature that produces the consciously dialogical framework. Trawick is not an impartial observer; she is very much a part of what is happening around her.

When you are trying to understand a story in India it becomes important to consider the life of the person telling the story, and when you are trying to understand a person it becomes important to listen to the stories that that person tells. It is also important to recognise the ways in which one may lead to alterations in the interpretation or enactment of the other. The story may change to t the life; the life may change to t the story. (p. 24)

This deliberate stance as a researcher is what sets Trawicks ethnography apart from other ethnographies such as Minturns Sitas Daughters (1993). Minturn, unlike Trawick, does not enter into a dialogical relationship with her subjects; her subjects are informants, not people on an equal footing from whom it is possible to learn. It is not clear 112

Sriram & Chaudhary Love in a Tamil Family

whether Minturn was familiar with the dialect spoken in Khalapur. Her account of Khalapur is a more factual listing of events and occurrences, in keeping with the requirements of a scientic study. In contrast, Trawick enters into the lives of her respondents, using the skills afforded by a narrative framework to illustrate the principles by which everyday life is transacted. In the introduction to Divine Passions: On the Social Construction of Emotion in India, Lynch (1990) refers to Trawicks work as being a doubled dialogue (p. 25; see Trawick, 1990). At one level, an ongoing dialogue with the family is taking place. At a more crucial level, Trawick is in dialogue with herself, trying to explicate, analyse and elucidate the dialogues with the family. It is possible to discern yet another level of communication in the book: that with the reader as she guides her audience to accompany her in the search for the reality as it unfolds before her. This dialogue is carried through till the end with skill and openness. Trawick does not set herself up to judge the people whom she lives with and becomes a part of. Love in itself is assumed to be a pan-cultural emotion. However, the expressions of love vary widely primarily because behaviour is often used to dene emotions. The Western idiom for understanding either the expression or the importance of love fails to hold true in the Tamil or the Indian way of life. The display rules for the expression of affection also vary across cultures, bringing about crucial differences. The theoretical framework for the book extends from the postmodern need to de-construct existing theoretical claims. There is a desire to understand the context, and thereby seek meaning for plurality of self and culture, through the idiom of love. The Dramatis Personae Themozhiyar, also known as Ayya, and his family were the primary sources of information for Trawick. This was not Ayyas natal family. The family were upper-caste Hindus coming from the Reddiar caste. They were impoverished landowners, barely able to scrape a subsistence living from the land they owned, from a village near the city of Chennai. The head of the family was called Annan (elder brother). He was married to Anni (a Tamil kinship term that means elder brothers wife). Annis sister Padmini was married to Ayya. Anni and Padmini were cross-cousins of Annan; Annans mother was in the kin position of Attai, or fathers sister, to Anni and Padmini. Various other crosscousins to Anni and Padmini resided in the household for periods of time; among these were Mohana and Vishvanathan. Then there were 113

Culture & Psychology 10(1)

the children, a crucial part of the family. Annan and Anni had a grownup daughter called Anuradha; they also had an 8-year-old daughter and a 6-year-old son. Padmini had an 8-year-old daughter, a 6-year-old daughter and a 2-year-old son. Mohana had a 2-year-old son. In the family, Ayya and Anni formed the emotional core from which the rest of the family took their cue. When Trawick introduces the family to the readers, she also includes her son and herself in the introduction, a subtle inclusion but a signicant stance in the political implication of doing research in the eld. This is another thread that is woven in the rendering of her story: the balancing of her position as an obvious outsider who has chosen to mediate the social distance between herself and her eld to become closer to the people whose lives she unpackages for the world. This invisible distance that exists between a researcher and the researched has received far less attention than it deserves. Trawick opens up this debate with courage and conviction, making her decisions, both professional and personal, available for others to read and reect upon. In every research endeavour, such arguments are thrown up, to be included, ignored or abandoned, but rarely does the reader or the reviewer have access to the tedious dynamics behind such processes. The family described above is characterized by the kinds of kin networks assumed to be typical of Southern India. In many South Indian families, cross-cousin marriage is desirable. This further means that the position of the bride on entry into the family is not as a stranger, as occurs in North Indian families, where this form of marriage is not permitted. Thus, relationships within a marriage are likely to carry the resonance of earlier, comfortable relationships within the natal family. While there is social sanction for cross-cousin marriage, data from actual marriages show that the incidence of such marriages is low (Trautman, 1981). This has implications on the issue of the Oedipus complex. The relationships that Trawick emphasizes are between father and son, mother and daughter, and brother and sister. The incestuous longing of the son for his mother is not a feature that emerges in the text. If we go by what Kurtz (1992) says,

. . . the main barrier between the child and his mother . . . is not the father but the in-law mothers. These women, moreover, are not primarily rivals of the child for the love of the mother. Rather, they are rivals of the mother for the love of the child. (p. 235)

In the context of the Tamil family, the in-law mothers are not strangers to the mother, but in many cases are kin to her through the practice of 114

Sriram & Chaudhary Love in a Tamil Family

cross-cousin marriage, perhaps deeply changing the underlying afliations within the family.

The Dominant Themes

The title indicates that emotional love is the primary theme to be explored in the book. However, the book provides insights into kinship patterns and kin bonding prevalent in South India about how relational love is an enduring feature of lial interactions, an emotion that, when scrutinized, seems fundamentally different from the surge of affections so integral to the Western notion of love. Trawick illustrates the lives of women and children in the everyday context of life. The theme of intentional ambiguity (pp. 4041) as a means of understanding how multiple strands are woven into everyday life, drawing from experience, mythology, poetry and, most importantly, relationships with others, is drawn up and elaborated upon. Issues of relationships between caste groups, which are an integral part of Indian life, are also dealt with in the association between the members of the family and their servants, who belong to a lower caste. Love or Anpu Anpu, as seen by Trawick, is a way of living. It is a way of transacting life. It is expressed, but not spoken of, as love. Anpu has certain inherent characteristics. While Trawick sees the characteristics of anpu as being Tamil in nature, one can nd many similarities with family relationships in other parts of India as well. Anpu grows in hiding; it needs to be contained (adakkam). The most crucial love, mother love, needs to be contained most. It is this containment that does not permit the expression of fondness and affection for ones own child, something that nds expression in folk expressions all over the country. It is believed that a mothers close regard of her own child can carry potential harm, and the open display of affection is certainly believed to bring on misfortune, either directly, or indirectly through the evil glance of another. This theme has been explored by Das (1976) in her study of Punjabi families, where it is felt that other members of the family are there to express love for the child. The child is not just the child of the mother, but, more importantly, is the child of the entire family. Mother love should be kept within limits at all times. Too much love, an overowing of love, can hurt both the giver and the recipient. It would probably lead to a development of solipsism, at the cost of living as a part of a large group such as a family. Seymour (1999), in her ethnographic work 115

Culture & Psychology 10(1)

on families in Orissa, observed the same tendency to keep mother love under control. In a similar vein, affection between spouses is to be avoided at all costs, Trawick discovers. In public, there is an avoidance of mentioning the spouses name. (This custom is prevalent in many parts of India, where it is seen as a form of disrespect to call the husband by name. Husbands are named on the teknonymy principle rather than by their given name. To summon a husband, an equivalent of please listen [sunte ho ji, in Hindi; parengo in Tamil] is used.) Intimacy between husband and wife can serve to jeopardize the collective wellbeing of the family; similarly, the relationship between a mother and child must be controlled. Containment is expressed sometimes by downgrading the loved one either through a nickname (e.g. naming a child kupai or rubbish, which serves to devalue the child) or through a black spot put on the cheek to ward off evil. Love grows by habit (parakkam). In their dealings with children, adults invoke the concept of parakkam often. Once a habit is formed, the person would feel uncomfortable without it, and would actively seek it out if deprived of it. What you looked like and what you did showed to others what your parakkam was, and hence, what you were (p. 98). Being exposed to elements in the atmosphere can also absorb parakkam; it will be integrated into the personality, such that, at a particular point, the parakkam becomes the personality. Through repeated practice, a habit can become a quality of the person. Parakkam leads to an ease of functioning with another, and consequently allows for the expression of love. Parakkam with a person means having that person as a part of the system. Hence it is necessary for love; and parakkam continues because of love. It is possible to discern how deeply different these beliefs are from the prevailing notions of the love expressions in public culture, even within India. Harshness and Cruelty (Kadumaai, Kodumai) Just as love is tender, love is also cruel and forceful. Just as growth and change are painful, so also is maturity. Physical affection for children is expressed more often than not by slaps, pinches and tweaks. A child will sometimes be punished for a mistake made by another. Or sometimes a child will be punished by one and comforted by another, maybe even punished by one to be comforted by the other. The punisher was always the mother, and the comforter somebody else (p. 77). Adults often play at a game of reprimanding and comforting a child alternately till the child begins to weep. When the child weeps, he will be cuddled and comforted or distracted with something else. 116

Sriram & Chaudhary Love in a Tamil Family

In interactions with adults, the harshness of anpu is seen in the intense interactions in the form of loud arguments interspersed with laughter. The feeling was that intense love required intense interaction. The true sign of loves absence might be the absence of any interaction at all (p.101). The association of harshness and cruelty with love is related to the belief that it is better to get the punishment over and done with. If hardship were to became a habit, then the fruits, as and when they came, would be that much sweeter. The world is a place of deception, being full of maya. Making children cry in games of playful affection makes one tough, capable of enduring a lot, of absorbing insults with equanimity. Just as you have to learn to do without, the need for sharing is taught. Mothers deliberately ignore, tease and are cruel to their children to push the affection outward away from the closest blood-tie between mother and child. This limiting of pleasure is a very Indian phenomenon. Idiomatic sayings talk about how laughter and tears go hand in hand, and how too much laughter will bring only tears. As children grow older, a rm disciplining hand is required to provide the necessary succour to allow the child to grow strong and self-reliant. It is this harshness that Trawick nds most difcult to understand and detach herself from. Seymour (1999) observes that teasing behaviour seen between caregivers and children serves the purpose of keeping young children actively engaged in dependent seeking activity with others until they are old enough to reverse roles and become the teasers/givers. In this manner, an active form of interdependence among family members is inculcated (p. 83). This socialization for interdependence results in affect being diffused among family members. Personal Relationships and Love In Trawicks work, an association is built between love and poverty and simplicity (erumai, elimai). The negation of the symbols of wealth is positively linked with expressions of anpu in Ayyas family. Doing without luxuries is seen as a form of being grown up, of being adult, and as a matter of expressing love. It may be preferable to see it as love being related to unity in the face of adversity. Anpu means going without if your nearest and dearest are unable to have access to an item of luxury. Luxury is for children (not that they are indulged with luxury either), for the immature. Anpu here implies solidarity of family forms in the face of social criticism. Anpu is further characterized by servitude (adimai). Just as love entails containment, thereby binding an individual, the reciprocal of 117

Culture & Psychology 10(1)

containment, servitude, is seen as a powerful expression of love. Adimai implies having nothing of ones own (p. 111). Feeding habits of women in India (not just in Tamil Nadu) are expressions of love and servitude. In the name of love, food is served to guests and children; often without considering whether the person wants the food or not. A refusal of food thus offered in love could be read as a rejection of love. Children are often coaxed to eat just one more mouthful, for my sake. If you love me, you will eat some more; these are messages from childhood that resonate in many Indian homes, especially when children return home after long intervals of time, or where grandparents are present. This particular linkage of food with the expression of love in childhood was one of the most enduring memories people had of growing up in Indian families (Chaudhary & Keller, 2003). Love mixes you up, causes confusion (kalattal and mayakkam). Love is considered to be intoxicating, a state when the mind is dizzy and unable to think clearly. This is probably the closest to the infatuation that is spoken of in Western romantic literature. With age, the confusion of love is supposed to lessen as a resistance develops. Love has the effect of reversing and erasing distinctions, of mixing up. Distinctions between what is mine vs what is yours are erased in the context of anpu. To draw distinctions implies a lack of love:

. . . a concept of love that is based upon familial interdependence and a sense of duty (dharma) to ones relatives is encouraged. Initially, it is communicated to the child by various persons through constant physical contact holding, feeding, carrying and co-sleeping. Later it will be communicated in other ways, but always with set limits. Love and concepts of dominance and submission are inextricably connected. . . . love is not so much an emotion generated by a specic individual, as it is a deep sense of emotional connectedness associated with members of ones extended family. (Seymour, 1999, pp. 8485)

Intentional Ambiguity

In the introduction to the book, Trawick develops a theory of the importance of ambiguity in the life of the Indian and the Tamil in particular. In Trawicks estimation, ambiguity is a fundamental quality of the Asian psyche. It is assumed to be an inherent part of the belief of the sacred, and is an integral part of the communication system. In this is the recognition that signs and their meanings are different things; they may have different names. The knowing and simultaneous attribution by the same person of mutually exclusive meanings to a single sign is a part of the ambiguity that is accepted and even encouraged within the system. In the context of communication, the informational 118

Sriram & Chaudhary Love in a Tamil Family

content of the communication is not as important as the personal relationship that is established during the social interchange, thereby greatly diminishing the strength of semantic meaning as it is understood in the conventional study of language. An understanding of ambiguity is crucial to the understanding of the cultural system. Every event and communication has more than one meaning. Just as poetic ambiguity resonates in Tamil poetry, psychological ambiguity is also inherent in the individual. It is what allows for a unication of varied, disparate emotional patterns and personalities.

The patterns of ambiguity dene the relationships between self and others. As life progresses, what happens to the self is neither individuation (i.e. increasing differentiation of self from others) nor internal integration (i.e. crystallization of a stable sense of self), but rather a continuous decrystallization and deindividuation of the self, a continuous effort to break down separation, isolation, purity, as though these states, left unopposed, would form of their own accord and freeze up life into death. (pp. 242243)

The distinction between self and others is essentially a Western phenomenon. The self as seen as a system of isolation, with boundaries clearly drawn, does not t into the cultural context of the Tamil and, further, the cosmos of the Indian collectivity. The individualist self can never nd anything sacred in a relationship, because relationships are means to ends; and relationships are the essence of anpu.

How Cultural Unity is Maintained

The principles that maintain cultural unity and sameness can also function to sustain the self as defence mechanisms. Trawick discusses some of the operating principles functioning towards the solidarity of the family. Mirroring/Twinning The phenomenon of mirroring or twinning is seen in how repeatedly . . . a pair of children or adults would be linked with each other by themselves or by others and dened as balanced and equivalent: equal in some ways, opposite in others, a matched set, mirror images, twins (p. 243; e.g. periavar vs cinnavan or big man vs small man when referring to Annan and Ayya together). Often the names of the two matched individuals are merged into a compound word. Matched nicknames also abound in such cases. In the case of children, such twins are dressed alike. In Ayyas family, among the children, Trawick speaks of how Arulmori, Ayyas daughter, in the absence of a same-sex age-mate and 119

Culture & Psychology 10(1)

human mirror, has to embody her own opposite. In contrast, both her older sister and younger brother with their human mirrors are moulded into mutual complementarity. The children are seen as balancing partners for each other. This concept may be of utility for maintaining and creating the harmony of the family, with one complementing the other; but the utility for the denition of the psyche of each child is questionable. Twinning is seen as similar to the concept of splitting as given by Anna Freud, wherein a person experiences in mixed form, two attributes that she would rather keep separate, and so assigns them in fantasy, to two different persons or entities (p. 245). In the Tamil family, two initially separate people were rendered complementary and then merged. The most-merged personalities (and so the least autonomous) were therefore the adults (p. 245). This phenomenon is perhaps responsible for the lack of individuality seen in the Indian context. The person who is different is seen as bucking the system, and straining the regular weave of the family and society in general. Individuality is acceptable only for the person recognized as being gifted or imbued with powers that set him or her apart from others, such as Ayya, who is seen as a scholar, a learned man, with special powers and dispensation. Complementarity/Dynamic Union Patterns of complementarity are seen in the interactions when, as a response to an act, instead of the desired response, its opposite occurs. Rather than changing patterns of behaviour, the same action is repeated, and elicits the same negative response as earlier. It is the engagement, the association between individuals, that is seen as the reward, rather than the goal. The association of individuals is often such that balance is never reached. Trawick gives the example of money-lending etiquette, wherein in repayment, accounts are never settled completely; an extra rupee is added, as a reason for the two parties to meet and do business again. In another instance, Ayya deliberately stops short of completing the translation of a poem at the penultimate stanza. Dynamic union is an integral part of the Dravidian cosmos as reected in the kinship system and the conscious seeking for afnity as belonging. A man marries his cross-cousin (Mothers Brothers Daughter), thereby

. . . giving it momentum, there also burns longing between actual human individuals, longing aroused in part by the experiences of childhood and in part by mythic and ideal patterns that people seek to live out but which in their actual lives, they can never fulll. (p. 247)

120

Sriram & Chaudhary Love in a Tamil Family

In kinship terminology in South India, the same kin term is used for Mothers Brother and Father-in-law (mama). Dynamic union and complementarity is seen abundantly in poetry and linguistic usage in Tamil. All these devices are seen as attempts to maintain tension rather than bringing resolution. Sequential Contrast Trawick makes connections between Tamil myths and everyday life. Just as in myths, events are viewed in sequence, never being seen at the same time to give a complete picture. The sequential contrast can be seen in the dealings with children, wherein they are alternately punished and comforted. Emotions tend to swing pendulum-like. Each opposite is the seed for its obverse; the opposites cannot be kept separate: all rhythms are transformations and reverse transformations of states into opposite states and then back again, repeatedly (p. 250). Tamil poetry, with an abundance of this swing between point and counter-point, may be an extension of the contrasts that exist in everyday dealings in the family context; hence its importance. Projection/Introjection The phenomenon of projection is seen as a means of allowing personalities to develop interdependently, such that they shape one another. Just as traits of personality can be handed down through generations, they can be transferred laterally. The traits of the father can be seen eventually in the son. Two individuals sharing a kinship term are considered as having traits in common. A son was expected in some way to embody his father, a daughter to embody her mother (p. 251). This pattern of projection can be seen very commonly all over India. Another projection is from ones name. Bearing the name of a mythic character implies possessing some characteristics in common with that character. The implication is that what is borne in the blood will eventually be revealed as the truth. Internal Contradiction/Category Mediation Unlike the Western belief that a thing cannot simultaneously be A and not A, Indian approaches to such absolutes are more blurred. If we consider the boundaries of the sexes, male vs female, the Indian cultural context allows for a proliferation of androgynous forms even in divine depictions. It is possible to express distinctly different ways of relating to people in a seemingly contradictory fashion. There would appear to be a greater range of possible relations into which one can 121

Culture & Psychology 10(1)

enter, and a greater range of possible modes of being that can be assumed without worrying about consistency. We would hesitate to generalize this statement of Trawicks. The scope of possible behaviours and ways of functioning may be wider in India; but this may be more true for men than women. In the case of women, it is age and marriage that may provide a channel for experimenting with differentials in culturally prescribed ways of behaviour. Cultural prescriptions for gender-appropriate behaviour are endorsed through socialization, and escaping the hidden internal tyranny that Trawick speaks of may be more wishful thinking than wish-fullment. Trawick herself comes around to discussing these complexities in her later publication (Trawick, 2003). Hiddenness Meaning is often hidden, not clear to the visible eye. There is a play of illusion, where many different things seem to be said. There are many acts of deliberate irony, when feelings are hidden by their opposites, where the hiding of the feeling is what communicates its presence. Trawick draws a parallel here between poetry and real life in that, as in poetry, there is a deliberate play with words, often resorting to subtlety, metonymy, metaphor and other nuances in the use of language. This sort of obliqueness nds an important place in the lives of people and the relationships that they construct around themselves. Trawick assumes that feelings are hidden not as a means of cutting off communication, but to allow the relationships to exist in a dynamic mode, without clear articulation. A certain tension develops, which serves to bind the self to others. To those whom one loves, one gives without limits, and one expects their demands to be limitless. The giving is not done to end the taking but to start and keep going an endless, dynamic bond (p. 256). Just as giving increases desire, hiding increases further seeking. Love is to be hidden, expressed through actions, and not spoken in words. Love is hidden in the harshness and the teasing. It is to be inferred and understood, and does not need to be spoken out loud. The echoes of some of these strategies for sustaining long-term relationships are displayed, in far more exaggerated and melodramatic terms, in Indian cinema. Plurality and Mixture, Boundlessness and Reversal Love means mixture and confusion. The boundaries between individuals and relationships are blurred and constantly reversed. Love goes beyond paired bonds. It encompasses everybody. Identity of the self and the identity of the loved one are lost in the crowd. 122

Sriram & Chaudhary Love in a Tamil Family

What Trawick Has Not Done

Trawick paints a very rosy picture of the family. There is very little evidence from the readings of any kind of family strife and tension. This is a little difcult to believe. The other issue may be that the family reveals its best face to the stranger in their midst, however much she may feel a part of the family in question. In a later piece on the Indian family, Trawick (2003) is more critical when she discusses her doubts about whether this social collective will survive in its present form because of the different pressures that are exerted on the individual members for the survival of the collective. Perhaps she was able to see through some of the apparent patterns of collective harmony and apprehend the difculty that can ensue from a life-long commitment to a difcult relationship with so much intensity and expectation. There is no evidence whatsoever of any sibling rivalry. This could of course be because of the twinning/mirroring concepts given by Trawick. However, between Siva and Oli, the children of the household, we would expect some sibling rivalry, given that the adults, all of whom favor Oli, discriminate against Siva. Trawick herself describes Siva as the fall guy, constantly undervalued against Oli. Perhaps some of this absence of rivalry could also be linked to the social value placed on the child, the motivation to create a hierarchy that seems quite basic to the Indian psyche, wherein Siva just cannot even think of manifesting rivalry against Oli. Trawick provides no speculation about why such rivalry should be absentif, indeed, it is. The consequence of not having an age-mate of the same sex also has not been sufciently analysed by Trawick. In the family whom Trawick studies, two of the children, Arulmori and Umapati, do not have an age-mate of the same sex. While Trawick has examined kinship terminology, a more in-depth discussion of this needs to be undertaken. In the case of Anni and Padmini, the term they use for their mother-in-law is Attai. In kinship terms, attai refers to Fathers Sister, and it is this kinship relationship that both Anni and Padmini are responding to. As shown by Raheja and Gold (1996), women tend to use kin terms from the natal family in preference to kin terms dened by marriage. The acceptable kin terms for mother-in-law in Tamil are maamiyar, attai or mami, as identied by Karve (1953, p. 200). The issue of sexual love and relationships is inadequately brought about in the book. Sex features in a big way in Tamil popular culture, music, poetry, dance and lm. Much of it relates to the relationship 123

Culture & Psychology 10(1)

(usually sexual) between men and women. There is a lot of metaphor in popular Tamil music, which is sexual in nature. Trawick makes a passing reference to the sexual interactions, but there is no embellishment. The sleeping patterns existing are not elaborated on. Perhaps this is due to the fact that sexuality may not have been displayed in the talk and she may not have been able to gather the non-verbal cues that are often employed in the discussion of sexuality. There is also a very large body of jokes and innuendoes in Tamil, which are accessible only through colloquial use, and it would take far more than the knowledge of Tamil vocabulary to gain access to the meaning system. The implications of the gulf between the classical and the colloquial use of language have to be understood. Trawick has combined classical Tamil poetry with her ethnography to analyse emotions and relationships in the Tamil context. It may be interesting to reect on what she would have found if she had tried to investigate love using the context of the popular culture of Tamil Nadu, although this has been attempted by other scholars (e.g. Thomas, 1995). Analysis of womens folk songs extrapolating to womens psyche and kin relationships has also been attempted by studies in a North Indian cultural context (e.g. Raheja & Gold, 1996). Is Trawicks eldwork comprehensive enough? The purists are likely to pick holes in her method, especially with regard to sample size and procedures. Trawick interviewed 150 respondents in an attempt to generalize her ndings from Ayyas family. In contrast, if we examine Seymours (1999) longitudinal study in Orissa, she followed 24 households over a period of 30 years. The detail that is there in her ethnography is distinctly lacking in Trawicks work. The effects of features such as education for women and changes due to urbanization that have effects on concepts of familism and self are not reected in Trawicks work. And this is despite her visiting the same family and area over a period of 20 years. Did she see no effect of social change on the men, women and children of the family? The ethics of Trawicks methodology may also be questioned by some. She has used actual names and photographs of the members of the family. This was probably done with the permission of the family. The photographs of the family that are there in the book are also available on-line on Trawicks web page, along with photographs from her recent study in Sri Lanka. In Trawicks defence, however, she has attempted to paint an accurate rendering of the family with an eye for detail and honesty. It is Trawicks honesty that strikes the reader most. She records with great detail her transactions with Ayya and other family members. 124

Sriram & Chaudhary Love in a Tamil Family

Trawicks relationship with Ayya is that of a student and a teacher. It is the connection that Trawick has with the family that serves to captivate the reader. Her emotions are there, at the surface, dealt with openly as she dialogues with the reader, herself and her family. Many of the things Trawick speaks of will strike a resonant chord with Indians all over the world. The simplicity of her style spans a depth of information that can be uncovered only on re-reading the book. We have read the entire book three times over, and parts of it more than that, and every re-reading gives more to think about. There are many Indians who nd it difcult to say the three little words I love you that the West depends on so strongly. Love is not spoken about; it is expressed through actions and deeds. It is easier to dene love through what it signies. It is parakkam that grows with association, like Trawick does.

General Conclusion: What Can Cultural Psychology Learn from South India?

Though Trawicks book is not new, her methods, which can be seen as unconventional by some, can be of use in the study of families in a cultural context. She has used a certain amount of licence in extrapolating from her observations to linkages in classical literature, and applying her ndings to everyday life. Intuition has played a part in her analysis. It requires courage and a great deal of conviction to use this method of studying a culture and, more importantly, of reporting that allows the reader to enter into a dialogical frame with the researcher and the respondents. The seeming simplicity of the reporting is what may be in actuality difcult to approximate. Training in research methodology with its formal methods and processes does not allow for seemingly dangerous extrapolation and intuitive concluding. It is most difcult to be non-judgemental about a culture with which one is familiar from the periphery. Trawick has succeeded in encouraging the development of an indigenous theory of emotional expression that allows movement away from reductionist approaches. Trawick, with her examination of love, may be coming partway towards explaining the reluctance to sever a relationship, even a bad one, in the Indian context. In her explanation of love in this family, she comes close to understanding the endurance of relationships in the Indian context; even relationships that are unpleasant survive due to the reluctance to sever an association. Western psychology has tended to assume that the individual strives for autonomy from others, seeking urgently towards individuation during development. 125

Culture & Psychology 10(1)

Successful socialization moves a child away from an intense emotional, symbiotic bond with a single caretaker towards an individuated selfhood. In the Tamil context (and the wider Indian context), the ideal self is not an autonomous individual, but a person bound to a groupsomeone who will subordinate his or her personal desires to the collective interests of the group. Renunciation of personal desires is culturally lauded and elaborated in the Indian context. The developmental eventuality of the lonely ascetic, seeking salvation through the conscious abandonment of physical desires, materials and relationships, seems like a theoretical play with the reversal of an intensely social early experience where even the differentiation between people becomes clouded. Ironically, the person who has been through all this intensity is expected to distance the self from others with age, rather than become more used to it. Perhaps this is another example of the constant moderation, balancing and complementarity that Trawick was able to discern in the family relationships and affective interactions. References

Chaudhary, N., & Keller, H. (2003, July 1216). Memories of me: Stories of the self from India and Germany. Paper presented at the regional conference of the International Association for Cross-cultural Psychology, Budapest, Hungary. Das, V. (1976). Masks and faces: An essay on Punjabi kinship. In P. Uberoi (Ed.), Family, kinship and marriage in India (pp. 185224). Delhi: Oxford University Press. Karve, I. (1953). Kinship organization in India. Bombay: Asia Publishing House. Kurtz, S.N. (1992). All the mothers are one: Hindu India and the cultural reshaping of psychoanalysis. New York: Columbia University Press. Lynch, O.M. (1990). Introduction: Emotions in theoretical contexts. In O.M. Lynch (Ed.), Divine passions: On the social construction of emotion in India (pp. 334). Berkeley: University of California Press. Minturn, L. (1993). Sitas daughters: Coming out of purdah. New York: Oxford University Press. Raheja, G.G., & Gold, A.G. (1996). Listen to the herons words: Reimagining gender and kinship in North India. Delhi: Oxford University Press. Seymour, S.C. (1999). Women, family, and child care in India: A world in transition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Thomas, R. (1995). Melodrama and the negotiation of morality. In C. Breckenridge (Ed.), Consuming modernity: Public culture in a South Asian world (pp. 157182). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Trautmann, T. (1981). Dravidian kinship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Trawick, M. (1990). Notes on love in a Tamil family. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

126

Sriram & Chaudhary Love in a Tamil Family

Trawick, M. (2003). The person behind the family. In V. Das (Ed.), The Oxford companion to sociology and social anthropology (pp. 11581178). New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Biographies

SUJATA SRIRAM, Ph.D., is Reader in the Unit for Family Studies at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, India. She has undertaken research studies on families and children. Her areas of academic interest are family dynamics and relations, quality of life, the development of selfhood, development of children in orphanages, and values and belief systems in families. ADDRESS: Sujata Sriram, Reader, Unit for family Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Deonar, Mumbai 400088, India. [email: sujatas@tiss.edu] NANDITA CHAUDHARY, Ph.D., is Reader in Child Development at Lady Irwin College, Delhi University, New Delhi. She has undertaken research projects in the area of programme evaluation, family studies, and the language and thought of children. She was placed at Clark University Psychology Department for pre-doctoral study under the Fulbright exchange programme. ADDRESS: Nandita Chaudhary, Department of Child Development, Lady Irwin College, New Delhi 110001, India. [email: nanditachau@hotmail.com]

127

Você também pode gostar

- Death, Beauty, Struggle: Untouchable Women Create the WorldNo EverandDeath, Beauty, Struggle: Untouchable Women Create the WorldAinda não há avaliações

- Vannathirai 05-05-2014Documento69 páginasVannathirai 05-05-2014foosaaAinda não há avaliações

- When the World Becomes Female: Guises of a South Indian GoddessNo EverandWhen the World Becomes Female: Guises of a South Indian GoddessAinda não há avaliações

- Kothi Dictionary HindiDocumento53 páginasKothi Dictionary HindiSumana MitraAinda não há avaliações

- Hela Bodhu Piyuma 37Documento36 páginasHela Bodhu Piyuma 37චතුර දසනායකAinda não há avaliações

- Fluid Signs: Being a Person the Tamil WayNo EverandFluid Signs: Being a Person the Tamil WayNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (3)

- Keyman Typing ManualDocumento4 páginasKeyman Typing ManualNareshAinda não há avaliações

- Arabizi FinalDocumento4 páginasArabizi FinalmittentenAinda não há avaliações

- The Feminine and the Familial: A Foray into the Fictional World of Shashi DeshpandeNo EverandThe Feminine and the Familial: A Foray into the Fictional World of Shashi DeshpandeAinda não há avaliações

- Somebody Give This Heart A Pen Teachers' GuideDocumento4 páginasSomebody Give This Heart A Pen Teachers' GuideCandlewick PressAinda não há avaliações

- Untouchable Fictions: Literary Realism and the Crisis of CasteNo EverandUntouchable Fictions: Literary Realism and the Crisis of CasteAinda não há avaliações

- Bonds PresentationDocumento10 páginasBonds Presentationapi-361344297Ainda não há avaliações

- Love and Honor in the Himalayas: Coming To Know Another CultureNo EverandLove and Honor in the Himalayas: Coming To Know Another CultureNota: 3 de 5 estrelas3/5 (4)

- Thesis On Desirable DaughtersDocumento8 páginasThesis On Desirable DaughtersCustomPaperSingapore100% (1)

- NadiyaDocumento25 páginasNadiyaNadi yaAinda não há avaliações

- Echoes of Feminism in Mahesh Dattani's TaraDocumento6 páginasEchoes of Feminism in Mahesh Dattani's TaraAnonymous CwJeBCAXp0% (1)

- International Journal of English Language, Literature and Translation StudiesDocumento5 páginasInternational Journal of English Language, Literature and Translation StudiesJeenDasAinda não há avaliações

- Gender Discrimination in The Select PlaDocumento6 páginasGender Discrimination in The Select PlaKrushna Viveka.CAinda não há avaliações

- Genderlect 2Documento15 páginasGenderlect 2Unknown UserAinda não há avaliações

- 10.BookReviewTheSunandHerFlowers 121-1241 PDFDocumento5 páginas10.BookReviewTheSunandHerFlowers 121-1241 PDFXimenaAinda não há avaliações

- Fatima ThesisDocumento27 páginasFatima ThesisFatima AkhtarAinda não há avaliações

- Issues of Gender Discrimination, Questions of Identity, Themes of Myth in Githa Hariharan's The Thousand Faces of NightDocumento5 páginasIssues of Gender Discrimination, Questions of Identity, Themes of Myth in Githa Hariharan's The Thousand Faces of NightAisha RahatAinda não há avaliações

- Feminism As A Wome1..Documento36 páginasFeminism As A Wome1..ChgcvvcAinda não há avaliações

- Concept of New Indian Women in Nayantara Sahgal's NovelsDocumento3 páginasConcept of New Indian Women in Nayantara Sahgal's NovelsSudhaAinda não há avaliações

- New Woman Ideology in Tagore's FictionDocumento5 páginasNew Woman Ideology in Tagore's FictionIJELS Research JournalAinda não há avaliações

- Portrayal of The Theme of Alienation in Anita Desai'SDocumento5 páginasPortrayal of The Theme of Alienation in Anita Desai'SBashemphang lamareAinda não há avaliações

- Dissertation On Thousand Faces of NightDocumento13 páginasDissertation On Thousand Faces of NightShreya Hazra100% (1)

- Uma Chakravarthy On Dalit FeminismDocumento13 páginasUma Chakravarthy On Dalit FeminismAkshay KaleAinda não há avaliações

- DamorDocumento19 páginasDamorchaudharyharish14969236Ainda não há avaliações

- 143-Article Text-813-1-10-20221121-2Documento8 páginas143-Article Text-813-1-10-20221121-2Khafifah MadiaAinda não há avaliações

- Tara ThemesDocumento9 páginasTara ThemesCat HunterAinda não há avaliações

- E-Gyankosh - Leela DubeDocumento16 páginasE-Gyankosh - Leela DubeLilyAinda não há avaliações

- HelenDocumento3 páginasHelenFaizullah MohsinAinda não há avaliações

- Kinship and History in South Asia Four Lectures (Thomas R. Trautmann)Documento141 páginasKinship and History in South Asia Four Lectures (Thomas R. Trautmann)Ghulam MustafaAinda não há avaliações

- Writing A Cause and Effect EssayDocumento4 páginasWriting A Cause and Effect Essaysoffmwwhd100% (2)

- Rajendra UniDocumento16 páginasRajendra Unichaudharyharish14969236Ainda não há avaliações

- Mahasweta Devi's Mother of 1084: A Subaltern Reading: Open AccessDocumento2 páginasMahasweta Devi's Mother of 1084: A Subaltern Reading: Open AccessSarthak KhuranaAinda não há avaliações

- Mod 8 Gender and NationDocumento28 páginasMod 8 Gender and NationharshitaAinda não há avaliações

- Structural IsmDocumento5 páginasStructural IsmmahiftiAinda não há avaliações

- Fatima ThesisDocumento27 páginasFatima ThesisFatima Akhtar100% (3)

- Search For Identity in DespandeyDocumento117 páginasSearch For Identity in DespandeySahel Md Delabul HossainAinda não há avaliações

- LiteratureDocumento4 páginasLiteraturechathuikaAinda não há avaliações

- Analysis of The Narrative Perspective of KatherineDocumento16 páginasAnalysis of The Narrative Perspective of KatherineAlaydin YılmazAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter PageDocumento54 páginasChapter Pagezadak3199Ainda não há avaliações

- Tannen Review Berk92Documento9 páginasTannen Review Berk92malchukAinda não há avaliações

- JPSP - 2022 - 342Documento7 páginasJPSP - 2022 - 342aswathisuresh046Ainda não há avaliações

- Economics EssayDocumento6 páginasEconomics Essayezknbk5h100% (2)

- 4 JLLANS FeministDocumento6 páginas4 JLLANS FeministShoushi ShadouyanAinda não há avaliações

- A Committed Social ActivistDocumento18 páginasA Committed Social ActivistShivam ShreshthaAinda não há avaliações

- Deliverance of Women and Rabindranath Tagore: in Vista of EducationDocumento5 páginasDeliverance of Women and Rabindranath Tagore: in Vista of EducationBONFRINGAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 3Documento26 páginasChapter 3Raj RudrapaaAinda não há avaliações

- Letters From A Father To His DaughterDocumento4 páginasLetters From A Father To His DaughterAyan Roy100% (2)

- DeshpandeDocumento9 páginasDeshpandePushpita PandaAinda não há avaliações

- Woven Lives Sisterhood and Feminism 1Documento32 páginasWoven Lives Sisterhood and Feminism 1Rikardo SihombingAinda não há avaliações

- The Indian Women Writers and Their Contribution in The World Literature-A Critical StudyDocumento5 páginasThe Indian Women Writers and Their Contribution in The World Literature-A Critical Studyliterature loversAinda não há avaliações

- Feasting, Fasting & Diamond DustDocumento12 páginasFeasting, Fasting & Diamond DustHoughton Mifflin HarcourtAinda não há avaliações

- Tnpsc2a PDFDocumento26 páginasTnpsc2a PDFArvind HarikrishnanAinda não há avaliações

- Five Year Plan WriteupDocumento13 páginasFive Year Plan WriteupChandra Shekhar GohiyaAinda não há avaliações

- KJDocumento5 páginasKJThangapandian NAinda não há avaliações

- இலக்கணநூல் 1859 ஜி யூ போப்Documento428 páginasஇலக்கணநூல் 1859 ஜி யூ போப்Thangapandian NAinda não há avaliações

- Viva PreparationDocumento24 páginasViva PreparationenggsantuAinda não há avaliações

- Gtpapay Gtpapay GtpapayDocumento10 páginasGtpapay Gtpapay GtpapayThangapandian NAinda não há avaliações

- Be Different, Be Focused, and Be A Josephite.,: Department of Mechanical EngineeringDocumento1 páginaBe Different, Be Focused, and Be A Josephite.,: Department of Mechanical EngineeringThangapandian NAinda não há avaliações

- India PartitionDocumento1 páginaIndia PartitionThangapandian NAinda não há avaliações

- Total Knee Exercise ProgramDocumento7 páginasTotal Knee Exercise ProgramThangapandian NAinda não há avaliações

- Mechanics of Materials: Jiao Luo, Miaoquan Li, Xiaoli Li, Yanpei ShiDocumento9 páginasMechanics of Materials: Jiao Luo, Miaoquan Li, Xiaoli Li, Yanpei ShiThangapandian NAinda não há avaliações

- DMRL Cep TalkDocumento44 páginasDMRL Cep TalkThangapandian NAinda não há avaliações

- Dalits in Dravidian Land ExcerptDocumento15 páginasDalits in Dravidian Land ExcerptThangapandian NAinda não há avaliações

- Advt FacultyDocumento45 páginasAdvt FacultyVignesh RamAinda não há avaliações

- ConductiveDocumento4 páginasConductiveThangapandian NAinda não há avaliações

- Paper 1Documento15 páginasPaper 1Thangapandian NAinda não há avaliações

- CNT EpoxDocumento7 páginasCNT EpoxThangapandian NAinda não há avaliações

- CSIRDocumento1 páginaCSIRThangapandian NAinda não há avaliações

- 2009-Role of StrainDocumento7 páginas2009-Role of StrainThangapandian NAinda não há avaliações

- Journal of Applied Mathematics and Mechanics: ReprintDocumento10 páginasJournal of Applied Mathematics and Mechanics: ReprintThangapandian NAinda não há avaliações

- CNT FAteDocumento6 páginasCNT FAteThangapandian NAinda não há avaliações

- W16Documento38 páginasW16Thangapandian NAinda não há avaliações

- Stress Strain DaigramDocumento7 páginasStress Strain DaigramSai PrithviAinda não há avaliações

- JJKJDocumento12 páginasJJKJThangapandian NAinda não há avaliações

- Staff - Workload - JULY - DeC 14 - As On 9.5.14Documento11 páginasStaff - Workload - JULY - DeC 14 - As On 9.5.14Thangapandian NAinda não há avaliações

- Origin 8 User GuideDocumento560 páginasOrigin 8 User Guideชายยาว จุฑาเทพAinda não há avaliações

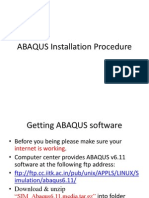

- Abaqus PDFDocumento15 páginasAbaqus PDFThangapandian NAinda não há avaliações

- Cover Letter Template AJEDocumento1 páginaCover Letter Template AJEThangapandian NAinda não há avaliações

- Analyze The Microstructure Given BelowDocumento3 páginasAnalyze The Microstructure Given BelowThangapandian NAinda não há avaliações

- EtchantsDocumento1 páginaEtchantsThangapandian NAinda não há avaliações

- Abaqus Installation PDFDocumento21 páginasAbaqus Installation PDFThangapandian NAinda não há avaliações

- Buzz Session Rubrics 2Documento8 páginasBuzz Session Rubrics 2Vincent Jdrin67% (3)

- Vietnam - Introduce Tekla Open APIDocumento34 páginasVietnam - Introduce Tekla Open API김성곤Ainda não há avaliações

- Problems of Education in The 21st Century, Vol. 27, 2011Documento125 páginasProblems of Education in The 21st Century, Vol. 27, 2011Scientia Socialis, Ltd.Ainda não há avaliações

- Accounting Theory ConstructionDocumento8 páginasAccounting Theory Constructionandi TenriAinda não há avaliações

- Literacy Progress Units: Spelling - Pupil BookletDocumento24 páginasLiteracy Progress Units: Spelling - Pupil BookletMatt GrantAinda não há avaliações

- Vice President, Private EquityDocumento2 páginasVice President, Private EquityMarshay HallAinda não há avaliações

- Standard DIN 5008 For Cover Letter DeutschlandDocumento1 páginaStandard DIN 5008 For Cover Letter Deutschlandsuzanne_13Ainda não há avaliações

- Business Research Methods (Isd 353)Documento19 páginasBusiness Research Methods (Isd 353)Thomas nyadeAinda não há avaliações

- Swami Vedanta Desikan Mangalasasana Utsava PrakriyaDocumento18 páginasSwami Vedanta Desikan Mangalasasana Utsava PrakriyaSarvam SrikrishnarpanamAinda não há avaliações

- LPP QuestionsDocumento38 páginasLPP QuestionsShashank JainAinda não há avaliações

- The Big Five Personality Test (BFPT)Documento6 páginasThe Big Five Personality Test (BFPT)FatimaAinda não há avaliações

- Evaluating IMC EffectivenessDocumento36 páginasEvaluating IMC EffectivenessNicole BradAinda não há avaliações

- SM21-Research Proposal Manuscript (Masuela Ocopio Olmedo &rael)Documento53 páginasSM21-Research Proposal Manuscript (Masuela Ocopio Olmedo &rael)Jhirone Brix Celsius OlmedoAinda não há avaliações

- Transcript Not Official Unless Delivered Through Parchment ExchangeDocumento1 páginaTranscript Not Official Unless Delivered Through Parchment ExchangealesyAinda não há avaliações

- SLM E10q3m4Documento6 páginasSLM E10q3m4May Dee Rose Kaw-itAinda não há avaliações

- Acute Confusional State ManagementDocumento18 páginasAcute Confusional State ManagementAhmed AbdelgelilAinda não há avaliações

- Study Guide (ITIL 4 Foundation) .PDF Versión 1 (27-44)Documento18 páginasStudy Guide (ITIL 4 Foundation) .PDF Versión 1 (27-44)Brayhan Huaman BerruAinda não há avaliações

- Form 3 Booklist - 2021 - 2022Documento3 páginasForm 3 Booklist - 2021 - 2022Shamena HoseinAinda não há avaliações

- Resume Abdullah AljufayrDocumento5 páginasResume Abdullah AljufayrAbdullah SalehAinda não há avaliações

- Grammar MTT3Documento2 páginasGrammar MTT3Cẩm Ly NguyễnAinda não há avaliações

- How To Tame A Wild Tongue Dual Entry NotesDocumento2 páginasHow To Tame A Wild Tongue Dual Entry Notesapi-336093393Ainda não há avaliações

- Asher's EssayDocumento2 páginasAsher's EssayAsher HarkyAinda não há avaliações

- Guiding Young ChildrenDocumento4 páginasGuiding Young ChildrenAljon MalotAinda não há avaliações

- CSTP 6 Concialdi 5Documento8 páginasCSTP 6 Concialdi 5api-417288991Ainda não há avaliações

- Java-Project Title 2021Documento6 páginasJava-Project Title 2021HelloprojectAinda não há avaliações

- Revised ISA SED - Final Version - April 17 2017 1 2Documento154 páginasRevised ISA SED - Final Version - April 17 2017 1 2Charo GironellaAinda não há avaliações

- Final Black Book ProjectDocumento61 páginasFinal Black Book ProjectJagruti Shirke50% (2)

- Switching Focus Between The Three Pillars of Institutional Theory During Social MovementsDocumento19 páginasSwitching Focus Between The Three Pillars of Institutional Theory During Social MovementsAnshita SachanAinda não há avaliações

- EEI Lesson Plan Template: Vital InformationDocumento2 páginasEEI Lesson Plan Template: Vital Informationapi-407270738Ainda não há avaliações

- Self-Concealment and Attitudes Toward Counseling in University StudentsDocumento7 páginasSelf-Concealment and Attitudes Toward Counseling in University StudentsMaryAinda não há avaliações

- Summary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesNo EverandSummary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1635)

- Indistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your LifeNo EverandIndistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your LifeNota: 3 de 5 estrelas3/5 (5)

- The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentNo EverandThe Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (4125)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNo EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNota: 2 de 5 estrelas2/5 (1)

- The Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismNo EverandThe Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (7)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionNo EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (404)

- Master Your Emotions: Develop Emotional Intelligence and Discover the Essential Rules of When and How to Control Your FeelingsNo EverandMaster Your Emotions: Develop Emotional Intelligence and Discover the Essential Rules of When and How to Control Your FeelingsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (321)

- The One Thing: The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary ResultsNo EverandThe One Thing: The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary ResultsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (709)

- Becoming Supernatural: How Common People Are Doing The UncommonNo EverandBecoming Supernatural: How Common People Are Doing The UncommonNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1480)

- Summary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisNo EverandSummary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (30)

- The Silva Mind Method: for Getting Help from the Other SideNo EverandThe Silva Mind Method: for Getting Help from the Other SideNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (51)

- Speaking Effective English!: Your Guide to Acquiring New Confidence In Personal and Professional CommunicationNo EverandSpeaking Effective English!: Your Guide to Acquiring New Confidence In Personal and Professional CommunicationNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (74)

- The 5 Second Rule: Transform your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageNo EverandThe 5 Second Rule: Transform your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (9)

- Uptime: A Practical Guide to Personal Productivity and WellbeingNo EverandUptime: A Practical Guide to Personal Productivity and WellbeingAinda não há avaliações

- The War of Art by Steven Pressfield - Book Summary: Break Through The Blocks And Win Your Inner Creative BattlesNo EverandThe War of Art by Steven Pressfield - Book Summary: Break Through The Blocks And Win Your Inner Creative BattlesNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (273)

- The 16 Undeniable Laws of Communication: Apply Them and Make the Most of Your MessageNo EverandThe 16 Undeniable Laws of Communication: Apply Them and Make the Most of Your MessageNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (73)

- The Science of Self Discipline: How Daily Self-Discipline, Everyday Habits and an Optimised Belief System will Help You Beat Procrastination + Why Discipline Equals True FreedomNo EverandThe Science of Self Discipline: How Daily Self-Discipline, Everyday Habits and an Optimised Belief System will Help You Beat Procrastination + Why Discipline Equals True FreedomNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (867)

- Own Your Past Change Your Future: A Not-So-Complicated Approach to Relationships, Mental Health & WellnessNo EverandOwn Your Past Change Your Future: A Not-So-Complicated Approach to Relationships, Mental Health & WellnessNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (85)

- Quantum Success: 7 Essential Laws for a Thriving, Joyful, and Prosperous Relationship with Work and MoneyNo EverandQuantum Success: 7 Essential Laws for a Thriving, Joyful, and Prosperous Relationship with Work and MoneyNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (38)

- The Slight Edge: Turning Simple Disciplines into Massive Success and HappinessNo EverandThe Slight Edge: Turning Simple Disciplines into Massive Success and HappinessNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (117)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeNo EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (253)

- How To Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie - Book SummaryNo EverandHow To Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie - Book SummaryNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (556)

- The Motive: Why So Many Leaders Abdicate Their Most Important ResponsibilitiesNo EverandThe Motive: Why So Many Leaders Abdicate Their Most Important ResponsibilitiesNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (224)

- Mastering Productivity: Everything You Need to Know About Habit FormationNo EverandMastering Productivity: Everything You Need to Know About Habit FormationNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (23)

- The Science of Deliberate Creation - A Quarterly Journal and Catalog Addendum - Jul, Aug, Sept, 2003 - Single Issue Pamphlet – 2003No EverandThe Science of Deliberate Creation - A Quarterly Journal and Catalog Addendum - Jul, Aug, Sept, 2003 - Single Issue Pamphlet – 2003Nota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (179)

- Summary: The Gap and the Gain: The High Achievers' Guide to Happiness, Confidence, and Success by Dan Sullivan and Dr. Benjamin Hardy: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisNo EverandSummary: The Gap and the Gain: The High Achievers' Guide to Happiness, Confidence, and Success by Dan Sullivan and Dr. Benjamin Hardy: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (4)