Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Essay Speech

Enviado por

Julie BlackettTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Essay Speech

Enviado por

Julie BlackettDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Julie Blackett SID 17354921 On the 3rd October, 1938, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain stood before the

House of Commons of the United Kingdom Parliament and presented a speech defending the decisions made in the recent meeting at Munich. This speech, and more commonly others Chamberlain made to the people in the days prior, have come to be known as Peace in our time or Peace for our time speech, depending upon the source used. This speech provides an important insight into the events occurring during this pivotal time and how the decisions made had an impact upon subsequent events. This response will consider the context and significance of this speech and attempt to identify any problems it poses. Perhaps the most important aspect to consider in regards to this speech is the context. This speech was given in the days following the Munich Agreement and during a time in which Chamberlain was engaged in a period of appeasement towards Germany after the devastation of the First World War. This was done in an attempt to prevent or at the very least delay another war in Europe, particularly in light of the fact that Chamberlain was aware of Britains military weakness as compared with Germany. (Badertscher 2009) Chamberlain had appeared to misjudge Hitlers character and global ambitions, believing that traditional diplomacy and a few concessions would help avoid war (Badertscher 2009) which likely contributed to the Munich Agreement. Considering the content of Chamberlains speech to Parliament, it seems that he is trying to gloss over certain circumstances surrounding the Munich Agreement. Chamberlain states that we did not go there to decide whether the predominantly German areas in the Sudetenland should be passed over to the German Reich. That had been decided already. Czechoslovakia had accepted the Anglo-French proposals. (Chamberlain 1938) This is a somewhat questionable matter, as it known that Czechoslovakia was not even present during the Munich discussion and this fact questions what they actually agreed to. It could be said that Czechoslovakia was essentially blackmailed into agreeing to the Anglo-French proposals, since should Benes reject the Anglo-French proposals, Czechoslovakia must fight Germany alone.(Shepardson 2006) The conference, which involved Britain, Germany, France, and Italy, did not invite the Czechoslovakian government, nor were they consulted. Chamberlain finishes this point of his speech by stating that he hopes the conditions decided upon during the Munich conference will provide greater security than it had in the past. This was obviously not the case. Thus it becomes necessary to consider what else is not true. Chamberlain even provides some defence of Hitlers character, by claiming that his decision to meet with the others at the conference, even though Hitler had already made his decisions, was a great and real contribution (Chamberlain 1938). It is likely that Chamberlain was simply putting the best possible slant to the events and people involved. Chamberlain also seemed to be operating under the delusion that it was the peoples desire for peace that led to the concessions made at the conference, rather than any threat. This statement blatantly ignores the threats Czechoslovakia faced before conceding to the demands regarding Sedetenland. Historians have argued that Chamberlains period of appeasement in the 1930s was to buy time so that Britain would have a chance to prepare for war, should it occur again

SID 17354921 1

(Badertscher 2009). This was certainly the case as Hitler ignored the agreements made in Munich, as only months later Germany invaded the rest of Czechoslovakia and annexed the country. This made clear that the appeasements had failed and provided Britain with a small period of time to prepare for war before Germanys invasion of Poland in 1939. It is important to note that there is still debate about the period of appeasement that Chamberlain is most well known for. Some historians take the view that it continued long past when it should have and that Chamberlain continued to hold belief in Hitler that was undeserved and unrealistic. Others saw it as providing Britain the best chance to survive economically, as well as providing Britain the chance to prepare for war should it occur. This view is enhanced by the fact that it must be said that Chamberlain did contribute to this process by building up Britains military and defence industry, including the institution of a draft.(Badertscher 2009) This was the first peace time draft in Britains history and supports the idea that Chamberlain was not as blind to the facts of the situation as some would say. It is important to note that this speech is often confused with the ones Chamberlain made to the public on his return from Munich. This leads to some conflicting ideas about what is said, for instance it is not during his speech to Parliament that Chamberlain uses the phrase peace for our time, but is rather used when addressing the public. It must also be noted that most of Chamberlains actions, including those contributing to the speech, are seen to have predominantly failed and the events leading up to and directly after this speech can be seen as the low point in his appeasement policy of the 1930s. The fact that Chamberlain resigns soon after matters come to head and then dies shortly after that also presents some problems when considering the causes and events that occurred during this time. Chamberlain wrote no political memoirs and did not really have the opportunity to explain his decisions after the fact or to address historys view of him and his actions. This speech provides a vital insight into the events that led to World War 2 and the people involved. It has become a popular reference, the term peace in our time being quite commonly, even though it is confused with the other speeches Chamberlain made to the public at the time. Overall, it is the defence of the decisions made at Munich and what that defence reveals, that makes this speech such a significant part of history.

SID 17354921

Bibliography Baderscher, Eric 2009, Neville Chamberlain, Great Neck Publishing, http://web.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.uws.edu.au/ehost/detail?vid=3&sid=bcd0bca5-fcc7-4aa0b532405598f0815b%40sessionmgr198&hid=124&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZSZzY29w ZT1zaXRl#db=f5h&AN=15315250 Chamberlain, Neville, 3 October 1938, Peace in our time, Parliamentary Debates, vol. 339, House of Commons of the Parliament of Great Britain Shepardson, D.E, 2006, A Faraway Country: Munich Reconsidered, The Midwest Quarterly, vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 81-99, http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.uws.edu.au/docview/195697949?accountid=36155

SID 17354921

Você também pode gostar

- Holiday Budget: Month Deposit Withdrawal BalanceDocumento1 páginaHoliday Budget: Month Deposit Withdrawal BalanceJulie BlackettAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5795)

- EssayDocumento4 páginasEssayJulie BlackettAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Return of Universal HistoryDocumento4 páginasThe Return of Universal HistoryJulie BlackettAinda não há avaliações

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Mclachlan, N.D. "Macquarie, Lachlan (1762-1824) " Australian Dictionary of Biography Lachlan Macquarie, Sources of Australian History, 124 Ibin., 125Documento5 páginasMclachlan, N.D. "Macquarie, Lachlan (1762-1824) " Australian Dictionary of Biography Lachlan Macquarie, Sources of Australian History, 124 Ibin., 125Julie BlackettAinda não há avaliações

- London Olympic HolidayDocumento7 páginasLondon Olympic HolidayJulie BlackettAinda não há avaliações

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- World Politics-Take Home Exam Julie Blackett SID 17354921 Question 3 Word Count 595Documento3 páginasWorld Politics-Take Home Exam Julie Blackett SID 17354921 Question 3 Word Count 595Julie BlackettAinda não há avaliações

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Julie Blackett SID: 17354921 Essay TaskDocumento4 páginasJulie Blackett SID: 17354921 Essay TaskJulie BlackettAinda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Class Writing Task 1Documento2 páginasClass Writing Task 1Julie BlackettAinda não há avaliações

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- American Biography Thomas JeffersonDocumento3 páginasAmerican Biography Thomas JeffersonBogdan HonciucAinda não há avaliações

- AR15 Full Auto Conversions ATF FOIADocumento17 páginasAR15 Full Auto Conversions ATF FOIAD.G.100% (2)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- China Economy in 1993-1999 2003 2004 2008 2012Documento458 páginasChina Economy in 1993-1999 2003 2004 2008 2012api-278315972Ainda não há avaliações

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

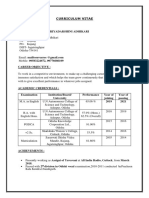

- Curriculum Vitae: Career ObjectiveDocumento2 páginasCurriculum Vitae: Career ObjectiveSubhashreeAinda não há avaliações

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Lack of Paper in VenezuelaDocumento4 páginasThe Lack of Paper in VenezuelaTannous ThoumiAinda não há avaliações

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- WbsedclDocumento1 páginaWbsedclSalman IslamAinda não há avaliações

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- Conflict TheoryDocumento6 páginasConflict TheoryTudor SîrbuAinda não há avaliações

- Rajiv Gandhi National University of Law: Submitted To-Submitted byDocumento13 páginasRajiv Gandhi National University of Law: Submitted To-Submitted bymohit04jainAinda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Annual Report - Sruti - 2016-17Documento36 páginasAnnual Report - Sruti - 2016-17Saurabh SinhaAinda não há avaliações

- Book Chandler Bosnia Faking Democracy After DaytonDocumento263 páginasBook Chandler Bosnia Faking Democracy After DaytonAndreea LazarAinda não há avaliações

- Causes of Failure of Democracy in PakistanDocumento9 páginasCauses of Failure of Democracy in Pakistanshafique ahmedAinda não há avaliações

- Research PodcastDocumento3 páginasResearch PodcastDaniela RodriguezAinda não há avaliações

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Provincial Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocumento3 páginasCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Provincial Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsAinda não há avaliações

- 192 Scra 100 - Ordillo Vs ComelecDocumento13 páginas192 Scra 100 - Ordillo Vs ComelecracaliguirancoAinda não há avaliações

- Household Record of Barangay Inhabitants (RBI)Documento1 páginaHousehold Record of Barangay Inhabitants (RBI)Jolland Palomares Sumalinog100% (1)

- Class 12 Political Science Notes Chapter 3 US Hegemony in World PoliticsDocumento7 páginasClass 12 Political Science Notes Chapter 3 US Hegemony in World PoliticsAhsas 6080Ainda não há avaliações

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- CVDocumento4 páginasCVapi-75669140Ainda não há avaliações

- Homeroom Pta OfficialsDocumento9 páginasHomeroom Pta Officialsapi-265708356Ainda não há avaliações

- Struktur OrganisasiDocumento1 páginaStruktur OrganisasiBill FelixAinda não há avaliações

- Palestine Power Point PresentationDocumento43 páginasPalestine Power Point PresentationAhmadi B-deanAinda não há avaliações

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocumento2 páginasCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsAinda não há avaliações

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- The AuthoritariansDocumento261 páginasThe AuthoritariansMrTwist100% (11)

- The First Philippine Telecoms Summit 2017 ProgramDocumento5 páginasThe First Philippine Telecoms Summit 2017 ProgramBlogWatchAinda não há avaliações

- Nicolás GuillénDocumento23 páginasNicolás GuillénJohn AtilanoAinda não há avaliações

- Culture JamDocumento263 páginasCulture JamallydAinda não há avaliações

- Monitoring Jap Codes WWIIDocumento204 páginasMonitoring Jap Codes WWIIescher7Ainda não há avaliações

- Aristotle's The-WPS OfficeDocumento4 páginasAristotle's The-WPS OfficeGamli Loyi100% (1)

- Format For Filing Complaint Under The Protection of Women From Domestic Violence Act, 2005Documento9 páginasFormat For Filing Complaint Under The Protection of Women From Domestic Violence Act, 2005tamalmukhAinda não há avaliações

- 60 Years of UN PeacekeepingDocumento5 páginas60 Years of UN PeacekeepingCher LimAinda não há avaliações

- CBSE Class 09 Social Science NCERT Solutions 3 History Nazism and The Rise of HitlerDocumento5 páginasCBSE Class 09 Social Science NCERT Solutions 3 History Nazism and The Rise of HitlerFranko KapoorAinda não há avaliações