Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

6-Peptic Ulcer and Helicobacter Pylori Eradication)

Enviado por

M.Akram TatriDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

6-Peptic Ulcer and Helicobacter Pylori Eradication)

Enviado por

M.Akram TatriDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

International Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences Vol 2(12) pp. 370-375, December 2010 Available online http://www.academicjournals.

org/ijmms ISSN 2006-9723 2010 Academic Journals

Full length Research paper

Peptic ulcer and Helicobacter pylori eradication: A review article

M. Akram1*, Shahab-uddin1, Afzal Ahmed2, Khan Usmanghani3, Abdul Hannan3, E. Mohiuddin4, M. Asif5 and S. M. Ali Shah5

1

Department of Basic Medical Sciences, Faculty of Eastern Medicine, Hamdard University, Karachi, Madinat-al-Hikmah, Muhammad Bin Qasim Avenue, Karachi, Pakistan 74600. 2 Department of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Faculty of Eastern Medicine, Hamdard University, Karachi, Madinat-alHikmah, Muhammad Bin Qasim Avenue, Karachi, Pakistan 74600. 3 Department of Basic Sciences, Faculty of Eastern Medicine, Hamdard University, Karachi, Madinat-al-Hikmah, Muhammad Bin Qasim Avenue, Karachi, Pakistan 74600. 4 Department of Surgery and Allied Sciences, Faculty of Eastern Medicine, Hamdard University, Karachi, Madinat-alHikmah, Muhammad Bin Qasim Avenue, Karachi, Pakistan 74600. 5 College of Conventional Medicine, Islamia University Bahawalpur, Pakistan-60600.

Accepted 2 September, 2010

Helicobacter pylori infection with relation to peptic ulcer disease has been the subject of exhaustive research. It is widely accepted that H. pylori is the major cause of peptic ulcer disease. In Pakistan, infection rate was about 83% in adult patients undergoing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy for various reasons. Infection with H. pylori is associated with a three to six fold increase in the risk of developing non cardiac (body and antrum) stomach cancer. The bacterium H. pylori can infect the stomach during child hood and cause life long chronic gastritis, which can lead to peptic ulcer disease and since reinfection in adults is extremely rare, adequate treatment permanently cures this former chronic recurrent, serious disease. If ulcers do not recur neither do ulcer perforation nor bleeding; then quality of life increases. Antibiotic resistance needs to be taken into account when designing treatment for H. pylori infection. Over the past decade, many different therapies were recommended and prescribed that resulted in inhibiting the malaise onset of H. pylori change rapidly. Eradication of H. pylori has been demonstrated to be useful for preventing the relapse of gastric and duodenal ulcer. In this article, we try to provide a basic frame work on which diagnosis and treatment modalities can be based for its curative and preventive function. Key words: Helicobacter pylori, ulcer disease, treatment. INTRODUCTION Helicobacter pylori is the major cause of gastro duodenal disease like peptic ulcer and important risk factor for gastric carcinoma and primary gastric lymphoma. H. pylori cause more than 90% of duodenal ulcers and up to 80% of gastric ulcers. H. pylori is a spiral shaped bacterium that was first confirmed to be present on the gastric surface in the 1983. When this bacterium was discovered, spicy food, acid, stress, and lifestyle were considered to be the major causes of ulcers. The majority of patients were given long term medications, such as H2 blockers, and more recently, proton pump inhibitors, without a chance for permanent cure. These medications relieve ulcer related symptoms, heal gastric mucosal inflammation, and may heal the ulcer, but they do not treat the infection. When acid suppression is removed, the majority of ulcers, particularly those caused by H. pylori, recur. Since it is known that most ulcers are caused by H. pylori, appropriate antibiotic regimens can successfully eradicate the infection in most patients, with complete resolution of mucosal inflammation and a minimal chance for recurrence of ulcers (Marshall and Warren, 1983).

*Corresponding author. E-mail: makram_0451@hotmail.com.

Akram

et

al. 371

Diagnostic testing Currently, there are several popular methods for detecting the presence of H. pylori infection, each having its own advantages, disadvantages and limitations. Basically, the tests available for diagnosis can be differentiated according to whether or not endoscopic biopsy is necessary. Histological evaluation, culture, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and rapid urease tests are typically performed on tissue obtained at endoscopy. Alternatively, simple breath tests, serology, and stool assays are sometimes used, and trials investigating PCR amplification of saliva, feces, and dental plaque to detect the presence of H. pylori are ongoing (Ananthakrishnan and Kate, 1998). Histology Histological evaluation has traditionally been the gold standard method for diagnosing H. pylori infection. The disadvantage of this technique is the need for endoscopy to obtain tissue. Limitations also arise at times because of an inadequate number of biopsy specimens obtained or failure to obtain specimens from different areas of the stomach. In some cases, different staining techniques may be necessary, which can involve longer processing times and higher costs. However, histological sampling does allow for definitive diagnosis of infection, as well as of the degree of inflammation or metaplasia and the presence or absence of MALT lymphoma or other gastric cancers in high risk patients (Malfertheiner et al., 2007). Culture However, because H. pylori is difficult to grow on culture media, the role of culture in the diagnosis of the infection is limited mostly to research and epidemiologic considerations. Although this culture is costly, time consuming and labor intensive culture does have a role in antibiotic susceptibility studies and studies of growth factors and metabolism (Fischbach, 2000). Polymerase chain reaction With the advent of PCR, many exciting possibilities emerged for diagnosing and identifying H. pylori infection. PCR allows the identification of the organism in small samples with few bacteria present and entails no special requirements in processing and transport. Moreover, PCR can be performed rapidly and cost effective, and it can be used to identify different strains of bacteria for pathogenic and epidemiologic studies. The PCR can detect segments of H. pylori DNA in the gastric mucosa of previously treated patients, false positive results can

occur, and errors in human interpretation of bands on electrophoretic gels can likewise lead to false negative results (NIH Consensus Conference, 1994). Rapid urease testing Rapid urease testing takes advantage of the fact that H. pylori is a urease producing organism. Samples obtained on endoscopy are placed in urea containing medium; if urease is present, the urea will be broken down to carbon dioxide and ammonia, with a resultant increase in the pH of the medium and a subsequent color change in the pH dependent indicator. This test has the advantages of being inexpensive, fast, and widely available. It is limited, however, by the possibility of false positive results; decreased urease activity, caused either by recent ingestion of antibiotic agents, bismuth compounds, proton pump inhibitors, or sucralfate or by bile reflux, can contribute to these false positive results (Abraham and Bhatia, 1997). Urea breath test A urea breath test similarly relies on the urease activity of H. pylori to detect the presence of active infection. In this 14 test, a patient with suspected infection ingests either C 13 13 labeled or C- labeled urea; C-labeled urea has the advantage of being non radioactive and thus safer (theoretically) for children and women of child bearing age. Urease, if present, splits the urea into ammonia and isotope-labeled carbon dioxide; the carbon dioxide is absorbed and eventually expired in the breath where it is detected. Besides being excellent for documenting active infection, this test is also valuable for establishing absence of infection after treatment, an important consideration in patients with a history of complicated ulcer disease with bleeding or perforation. In addition, a urea breath test is relatively inexpensive (whichever isotope is used) is easy to perform, and does not require endoscopy. However, if the patient has recently ingested proton pump inhibitors, antibiotic agents, or bismuth compounds, a urea breath test can be of limited value. Moreover, except for major medical centers or tertiary referral centers where results are usually available in fewer than 24 h, a urea breath test may be further limited by a turn around time of several days (or longer) required for transport of samples and analysis by specialized laboratories not present in many community settings (Tandon, 2000). Serologic tests In response to H. pylori infection, the immune system typically mounts a response through production of

372

Int.

J.

Med.

Med.

Sci.

immunoglobulin to organism specific antigens. These antibodies can be detected in serum or whole blood samples easily obtained in a physicians office. The presence of IgG antibodies to H. pylori can be detected by use of a biochemical assay, and many different ones are available. Serologic tests offer a fast, easy, and relatively inexpensive means of identifying patients who have been infected with the organism. However, this method is not a useful means of confirming the eradication of H. pylori; several different samples and changes in titers of specified amounts over time would be needed. In addition, few patients become truly seronegative, even after eradication of the organism. In low prevalence populations, serologic tests should be a second-line methodology because of low positive predictive value and a tendency toward false positive results. Serologic tests may be useful in identifying certain strains of more virulent H. pylori by detecting antibodies to virulence factors associated with more severe disease and complicated ulcers, gastric cancer, and lymphoma (Chiba et al., 1992). Stool antigen testing Stool antigen testing is a methodology that uses an enzyme immunoassay to detect the presence of H. pylori antigen in stool specimens. There is a cost effective and reliable means of diagnosing active infection and confirming cure, such testing has a sensitivity and specificity compared to those of other noninvasive tests (Peterson et al., 1993). General diagnostic principles The question of, which patients to test, when to test them, and what test to use, still poses problems for many physicians. Ultimately, the answer to these questions must be based on patient preference, cost, availability of different tests, and positive and negative predictive values of different tests (which depend on the individual patient population, including the prevalence of disorders caused by H. pylori infection in the community). Nevertheless, certain principles of testing seem universal. First, endoscopic methods of diagnosis should be used only if the procedure is necessary to detect some other condition besides H. pylori infection. Second, only those patients in whom treatment will make a difference should be tested. Conclusive evidence does not exist that eradication of the infection in patients with simple dyspepsia will relieve symptoms, and testing of asymptomatic patients without a history of documented peptic ulcer disease is not warranted. Testing can be considered on a case by case basis in patients with symptoms, suggestive of peptic ulcer disease. Because treatment of H. pylori infection is definitely indicated in

patients with active or previously documented peptic ulcer disease, gastric MALT lymphoma, or family history of gastric cancer; their H. pylori status must be clarified. Urea breath and stool antigen tests are the most cost effective tests to identify active infection, but their limitations must be considered. Serology is an excellent, inexpensive test to ascertain if someone with a history of peptic ulcer disease and unknown H. pylori status warrants treatment, thus endoscopy with tissue sampling in patients with a history of peptic ulcer disease can provide more definitive diagnosis of H. pylori infection, as well as information about the activity of peptic ulcer disease and possibly other factors at play (including gastric carcinoma). Follow up testing with urea breath or stool antigen tests which have both sensitivities and specificities greater than 90% is necessary to document cure in patients with complicated peptic ulcer disease e.g. perforation, hemorrhage, obstruction or recurrent symptoms and should be performed 4 weeks after completion of treatment (Bardhan et al., 1997). Management General treatment principles Determining the optimum treatment of H. pylori infection is difficult because the organism lives in an environment that is not easily accessible to many medications and because emerging bacterial resistance presents an added challenge. Moreover, many of the recommended regimens are difficult for patients to take, leading to problems with compliance; specifically, taking a large number of pills at least twice daily and coping with unpleasant adverse effects that encourage patient cooperation a little. Despite these obstacles, current regimens can obtain cure rates in excess of 85% in most patient populations (De Boer and Titrate, 1995). Patient management in primary care The majority of patients infected with H. pylori present initially in primary care, suffering from dyspeptic symptoms with or without alarm symptoms. This is where many of them can and should be treated for the infection, even though, in the absence of endoscopy, the primary care physician may not have an accurate diagnosis of the underlying disease pathology. In this environment, primary care physicians need to have a clear understanding of the major role that they play for the treatment of H. pylori. The recommendations given here are particularly relevant to the management in primary care, but many of them apply across clinical practice. Two strongly recommended indications that should be noted here as particularly relevant in primary care are patients who are first degree relatives of gastric cancer

Akram

et

al. 373

patients and eradication therapy in response to patients' wishes after full consultation. As recommended in the original Maastricht Consensus Report, a `test and treat' approach should be offered to adult patients under the age of 45 years (the age cut-off may vary locally according to the mean age of gastric cancer onset), thereby presenting, with persistent dyspepsia, in primary care. Several studies have since been published that support this recommendation (Anantharishanan and Kate, 1997). Antibiotic agents Currently, antibiotic agents used to treat H. pylori infection are administered in combination, while no single agent ever used as monotherapy, due to lack of efficacy and the potential development of resistance. Metronidazole or likewise proton pump inhibitor has activity that is independent of pH, but resistance to the drug is common in many parts of the world. This problem with resistance is ameliorated somewhat, however, when the drug is used with clarithromycin. Metronidazole can have unpleasant adverse effects (e.g. nausea) and a disulfiram-like reaction to alcohol ingestion is possible, although exceedingly rare. Clarithromycin has lower rates of resistance (approximately 7 to 11%), but is not acid stable, may cause dysgeusia and is more expensive than other antibiotic agents. Resistance to amoxicillin is rare, but this drug usually requires the co-administration of a proton pump inhibitor because its activity is pHdependent. Finally, tetracycline has the advantage of low cost and low occurrence of resistance, but can cause discoloration of the teeth in children and photosensitivity reactions (Marshall et al., 1987). Adjunctive agents The most popular agents currently used in combination with antibiotic agents to eradicate H. pylori infection are the proton pump inhibitors, that is, omeprazole or like wise proton pomp inhibitor being the most widely studied drug. Omeprazole acts not only by directly inhibiting bacterial microsomal enzymes, but also by raising intragastric pH, thus facilitating the action of antibiotic agents, reducing gastric secretions, and increasing antibiotic concentrations in the stomach. Other adjunctive agents include histamine receptor antagonists and ranitidine bismuth citrate, which has anti secretary properties in addition to the antibacterial action of bismuth (that is, interruption of the bacterial cell wall). Ranitidine bismuth citrate is no longer available (Penston, 1994). Current regimens Presently, the most efficacious regimens include two antibiotic agents and at least one adjunctive agent for 14

days. A literature citation study carried out has claimed adequate cure rates with a 7-day course of quadruple therapy (two antibiotics, two adjunctive agents), but other studies have not confirmed this finding. Most clinicians treat H. pylori infection with a triple drug or even quadruple-drug approach. 1. Administration of a proton pump inhibitor, clarithromycin and either metronidazole or amoxicillin for two weeks. 2. Administration of ranitidine bismuth citrate (this guideline preceded the drugs withdrawal in the United States), clarithromycin and either metronidazole, amoxicillin, or tetracycline for two weeks. 3. A proton pump inhibitor, bismuth, metronidazole and tetracycline for two weeks. For patients who fail initial triple-drug therapy, according to follow-up testing, subsequent therapy should involve using a different combination of available antibiotic agents, increasing the duration of treatment, or incorporating a course of quadruple therapy. Culture with sensitivity testing should be performed after twice treatment failures (Janan et al., 2001). Antibiotics and other agents As emerging drug resistance continues to plague efforts to eradicate H. pylori infection, new therapeutic regimens incorporating existing antibiotic agents and newly developed compounds are essential. Nitazoxanide is an effective agent when used in combination with omeprazole, and further studies are ongoing. In addition, macrolides other than clarithromycin may play a role in future therapies. The mapping of the complete genome of H. pylori has opened the door for a new era in chemotherapeutic drugs. It will now be possible to develop agents that act on specific key protein products that are vital to the survival of the bacterium (Glupezynski and Burette, 1990). Regimens for H. pylori Many antimicrobial agents have been studied for their efficacy in eradicating H. pylori infection either as a single agent or as a combination therapy. However, single antibacterial agent treatment schedules have not been sufficiently effective with eradication rates ranging from only 23% for amoxicillin to 54% for clarithromycin. Single drug regimens are not advocated due to the potential for the development of antibiotic resistance especially to macrolides and nitroimida-zoles, which are the key agents in the multidrug regimens for H. pylori. Dual treatments combining, a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) with either clarithromycin or amoxicillin was popular a few years ago as they were easy to explain to the patients and

374

Int.

J.

Med.

Med.

Sci.

were well tolerated. The newer dual drug regimen of ranitidine bismuth citrate (RBC) and clarithromycin for two weeks has shown few side effects and has a superior eradication rate compared to other dual therapies. However, it has still not been widely evaluated. Overall dual therapies are not very much in current use for the eradication of H. pylori due to low eradication rates (Howden and Hunt, 1998). Gastric ulcer The main point of difference in the management of a patient with H. pylori associated gastric ulcer is the need to exclude malignancy in an apparently benign gastric ulcer. Patients with gastric ulcer should, therefore, be reendoscope for about 8 weeks after H. pylori eradication therapy to confirm healing, obtain further biopsies if eradication of H. pylori leads to healing of gastric ulcer and markedly decreases the incidence of relapse. The effect of eradication of H. pylori on gastric ulcer complication is unknown at present. Antisectary maintenance treatment should, therefore, be ignited after successful eradication of H. pylori in those patients with gastric ulcer who have a history or hemorrhage or perforation, until complete healing of the ulcer is confirmed at follow up endoscopy (Harris, 1997). H. pylori and gastric cancer Infection with H. pylori is associated with a three to six fold increase in the risk of developing non cardiac (body and antrum) stomach cancer. Although prevention of gastric cancer through eradication of H. pylori is potentially extremely important in global terms (750,000 deaths attributable annually to the neoplasm), it must be emphasized that at present, there is no evidence that eradication of H. pylori decreases that risk, nor is it known at what stage H. pylori has to be eradicated to prevent the progression of chronic gastritis to atrophy, intestinal metaplasia and eventually to invasive cancer. Although infection with H. pylori is very common, the lifetime risk of developing non cardiac stomach cancer in infected individuals in the developed world is estimated to be less than 1%. In subjects with other risk factors for stomach cancer, such as one or more first degree relatives with this condition, or the presence of gastric mucosal dysphasia found at gastroscopy, it seems reasonable to offer H. pylori eradication therapy. It is important however, to discuss with the patient, the possible side effects of the treatment, the lack of evidence to support this practice and the possibility of treatment failure (Dajani and Klamut, 2000). Triple drug therapy Triple therapies with Lansoprazole, Amoxicillin and

Clarithromycin for eradication of H. pylori were studied in multicentric, randomized double blind fashion to evaluate the eradication rate and safety in Japanese patients with H. pylori positive active peptic ulcers. Both regimens gave satisfactory eradication rates of H. pylori in patients with gastric ulcer or duodenal ulcer. The triple therapy with LPZ 30 mg/AMPC 750 mg/CAM 200 mg bid may be preferred in Japan because of the excellent rates and lower rate of side effects (Ahuja et al., 1998). Quadruple treatment Addition of acid suppressant increases the efficacy of bismuth triple regimen. Quadruple treatment is more effective with proton pump inhibitor than with histamine 2 receptor antagonists and when tetracycline and metronidazole are incorporated. In meta-analysis, the quadruple regimen with increasing number of tablet as dosage form design each day are presented and analyzed. Nevertheless studies have found good compliance with a drop out rate compared with that of the easier triple therapies. A course for seven days seems to cure both metronidazole sensitive and resistant strains. Sensitive strains as mentioned are eradicated in four days. The high cure rate at day 4 shows its potency and wide therapeutic window (Hoffman, 1999). Recommendations for therapy Currently, the indication for treatment of H. pylori infection should confirm to establish guidelines as per the National Institute of Health (NIH) and the Indian consensus statements (Tandon, 2000). When the treatment is indicated, the regimen selected should have a known eradication rate of over 90%, which is according to the recommended guidelines for the treatment of H. pylori infection. Local (geographical) prevalence of antimicrobial resistance should be known so that drugs can be combined appropriately. Additional factors to be taken into account include cost, simplicity of the schedule to avoid noncompliance and side effects. As mentioned earlier, a proton pump inhibitor based triple therapy regimen with two antibiotics for duration of 7 to 14 days has come to be accepted as the first line of optimal therapy. European reports favour a one-week therapy (two antibiotics, two adjunctive agents) compared to 10 to 14 days therapy recommended by the Americans (De Boer and Titrate, 1995). In countries like India and Pakistan, where resistance to nitroimi-dazoles is high, it is better to avoid this class of drugs when choosing a combination therapy. It is preferred to use a PPI with amoxicillin and clarithromycin as the first line of treatment for duration of 10 days. An alternative line of therapy can be Ranitidine bismuth citrate in combination with amoxicillin and clarithromycin. Amoxicillin can be substituted with metronidazole when the local resistance

Akram

et

al. 375

to nitroimidazoles is low. Quadruple regimens are good as second line therapy for failed primary treatment. A triple regimen with a PPI and different combination of antibiotics not used earlier can also be tried. The duration of the treatment in this instance should be increased to increase the likelihood of cure. Although a seven day treatment is standard for PPI and Ranitidine Bismuth Citrate based regimens, the success rate can be improved by prescribing a 10 to 14 day regimen in patients who have had previous drug failure. Confirmation of eradication of H. pylori is not recommended in every case treated for H. pylori when an optimal regimen is used and patient compliance is good. However, confirmation of eradication might be required in patients with a history of ulcer complications or following treatment for MALT lymphoma. Most of the tests for confirming eradication are invasive and require endoscopy. Urea breath tests are recommended in guidelines as a preferred non-invasive choice for detecting H. pylori before and after treatment (Chey, 2007). Conclusions Triple therapy regimens comprising of a proton pump inhibitor or ranitidine bismuth citrate and two antibiotics (amoxicillin and clithromycin) are the standard therapy to treat H. pylori infection. Bismuth based triple therapy consisting of bismuth, tetracycline and metronidazole is less expensive as compare to proton pump inhibitor or ranitidine bismuth citrate based triple therapies. However, bismuth triple therapy manifest by side effects and metronidazole resistance in Asian countries like India and Pakistan. In Europe, a 7 day course of PPI based triple therapy is usually recommecnded, whereas, in USA, the same dosage prescribed is of 10 to 14 days. It is recommended 10-day triple therapy in a combination, which does not include nitroimidazoles. Clarithromycin resistance is also rising in countries where this antibiotic is widely prescribed for other infections. If a patient remains infected after a course of therapy for H. pylori, the second treatment should avoid the antibiotics that cause resistance. If the first line PPI based therapy fails, either an RBC based triple therapy or quadruple therapy consisting of a PPI and bismuth triple therapy combination is recommended. The antibiotic resistance in bacteria and understanding of its mechanism or eradication has to explored for the ultimate eradication of H. pylori infection.

REFERENCES Abraham P, Bhatia SJ (1997). First national workshop on Helicobacter pylori: Position paper on Helicobacter pylori in India. Indian J. Gastroenterol., 16: 29-33. Ahuja V, Dhar A, Bal C, Sharma MP (1998). Lansoprazole and secnidazole with clarithromycin, amoxicillin or pefloxicin in the

eradication of Helicobacter pylori in a developing country. Aliment Pharmacol., 12: 551-555. Ananthakrishnan N, Kate V (1998). Helicobacter pylori: The rap-idly changing scenario. In: Chattopadhyay TK. editor. G.I. Surg. Annu., 5: 1-20. Anantharishanan N, Kate V (1997). Helicobacter pylori and its role in disorders of the upper gastrointestinal tract. In: Gupta RL, editor. Recent Adv. Surg., New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers, 6: 168-189. Bardhan KD, Dallier C, Eisold H (1997). Duggan AE. Ranitidine bismuth citrate with clarithromycin for the treatment of duodenal ulcer. Gut, 41: 181-186. Chey w, (2007). American College of Gastroenterology Guideline on the Management of Helicobacter pylori Infection". Am. J. Gastroenterol., 102: 18081825. Chiba N, Rao BV, Pacemaker JW, Hunt RH (1992). Meta-analysis of the efficacy of antibiotic therapy in eradicating Helicobacter pylori. Am. J. Gastroenterol., 87(17): 16-27. Dajani EZ, Klamut MJ (2000). Novel therapeutic approaches to gastric and duodenal ulcers: an update. Expert Open Investig. Drugs, 9: 1537-1544. De Boer WA, Titrate GNJ (1995). The best therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection. Should efficacy or side effect profile determine our choice? Scand. J. Gastroenterol., 30: 4017. Fischbach W (2000). Primary gastric lymphoma of MALT: considerations of pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapy. Can. J. Gastroenterol., 14: 44-50. Glupezynski Y, Burette A (1990). Drug therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection. Problems and Pitfalls. Am. J. Gastroenterol., 85: 15451549. Harris A (1997) . Treatment of Helicobacter pylori. Drugs Today, 33: 5966. Hoffman PS (1999). Antibiotic resistance mechanisms of Helicobacter pylori. Can. J. Gastroenterol., 13: 243-249. Howden CW, Hunt RH (1998). Guidelines for the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Ad Hoc Committee on practice parameters of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am. J. Gastroenterol., 159: 2330-2338. Howden CW, Hunt RH (1998). Guidelines for the management of Helicobacter pylori infection-for and on behalf of the Ad hoc Committee on Practice Parameters of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am. J. Gastroenterol., 93: 2330-2337. Janan FAJ, Ahmad MM, Rowshon AHM, Hussain S, Hussain M, Rahim S (2001). Eradication of Helicobacter pylori with a metronidazole containing regimen in a metronidazole abusing population. Indian J. Gastroenterol., 20: 37. Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, Bazzoli F (2007). Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: The Maastricht III Consensus Report, 56: 772-781. Marshall B, Warren JR (1983). Unidentified curved bacillus in active chronic gastritis. Lancet, 1: 1. Marshall BJ, Armstrong JA, Francis GJ, Nokes NT, Wee SH (1987). Antibacterial action of bismuth in relation to Campylobacter pylori is colonization and gastritis. Digestion, 37: 16-30. NIH Consensus Conference (1994). Helicobacter pylori and peptic ulcer disease. J. Am. Med. Assoc., 272: 65-69. Penston JG (1994). Helicobacter pylori eradication-understand-able caution but no excuse for inertia. Aliment. Pharmacol., 8: 369-389. Peterson WL, Graham DY, Marshall B, Blaser MJ, Genta RM, Klein PD (1993). Clarithromycin as monotherapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori: A randomized, double blind trial. Am. J. Gastroenterol., 88: 1860-1864. Tandon R (2000). Second national workshop on Helicobacter pylori: Consensus Statements-Treatment of Helicobacter pylori in peptic ulcer disease. Indian J. Gastroenterol., 19: S37.

Você também pode gostar

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire (PSQ) - Validity and ReliabilityDocumento12 páginasPediatric Sleep Questionnaire (PSQ) - Validity and ReliabilitySabrina GurksnisAinda não há avaliações

- Anorexia Case Study and Test QuestionsDocumento25 páginasAnorexia Case Study and Test Questionsclaudeth_sy100% (2)

- Coma Dfiferential DiagnosisDocumento23 páginasComa Dfiferential DiagnosisGeorge GeorgeAinda não há avaliações

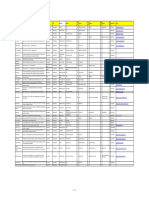

- Name Clinic/Hosp/Med Name &address Area City Speciality SEWA01 Disc 01 SEWA02 DIS C02 SEWA03 Disc 03 SEWA04 DIS C04 Contact No. EmailDocumento8 páginasName Clinic/Hosp/Med Name &address Area City Speciality SEWA01 Disc 01 SEWA02 DIS C02 SEWA03 Disc 03 SEWA04 DIS C04 Contact No. EmailshrutiAinda não há avaliações

- Comparative Study of Herbal Medicine With Allopathic Medicine For The Treatment of HyperuricemiaDocumento5 páginasComparative Study of Herbal Medicine With Allopathic Medicine For The Treatment of HyperuricemiaM.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- Xanthine Oxidase InhibtionDocumento10 páginasXanthine Oxidase InhibtionM.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- 81-Mini Review On Water BalanceDocumento4 páginas81-Mini Review On Water BalanceM.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- 75 Akram Et AlDiarrheaJMPR 11 1702Documento4 páginas75 Akram Et AlDiarrheaJMPR 11 1702M.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- 87-Ijapp-13-1049 - FinalDocumento6 páginas87-Ijapp-13-1049 - FinalM.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- Akram Et AlDocumento3 páginasAkram Et AlashorammarAinda não há avaliações

- 86-Arshad Original ArticleDocumento34 páginas86-Arshad Original ArticleM.Akram Tatri100% (1)

- Diabetes Mellitus Ij Diabetes and MeatbolismDocumento9 páginasDiabetes Mellitus Ij Diabetes and MeatbolismChristopher BrayAinda não há avaliações

- 88 Glucose 6 Phosppahte GJMS 11 036Documento3 páginas88 Glucose 6 Phosppahte GJMS 11 036M.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- 85-Aamir Somroo Original PaperDocumento5 páginas85-Aamir Somroo Original PaperM.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- 79-Aegle MarmelosDocumento3 páginas79-Aegle MarmelosM.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- 80 Qalb e SaleemDocumento5 páginas80 Qalb e SaleemM.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- 71 (Immunomodujmpr 11 1401Documento6 páginas71 (Immunomodujmpr 11 1401M.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- 74 Khalil Unani MDCNJMPR 11 509Documento4 páginas74 Khalil Unani MDCNJMPR 11 509M.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- 67 (Tribulus GhazalaDocumento4 páginas67 (Tribulus GhazalaM.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- 69 (Glycosides (JMPR 11 732Documento4 páginas69 (Glycosides (JMPR 11 732M.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- 66 (Ethno JMPR-11-1358Documento3 páginas66 (Ethno JMPR-11-1358M.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- 70 Rubinaajb 11 2248Documento6 páginas70 Rubinaajb 11 2248M.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- 65 (IrritaDocumento5 páginas65 (IrritaM.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- FASTADocumento3 páginasFASTAM.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- 60 Paper Published (Premenstrual Syndrome) JMPR 11 1198Documento6 páginas60 Paper Published (Premenstrual Syndrome) JMPR 11 1198M.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- 63-Ibrahim PJN (Clinical Evaluation of Herbal Medicine For Treatment of Intestinal WormsDocumento7 páginas63-Ibrahim PJN (Clinical Evaluation of Herbal Medicine For Treatment of Intestinal WormsM.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- 57 Faisal ZakaiJMPR 11 244Documento10 páginas57 Faisal ZakaiJMPR 11 244M.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- 62 Medicinal Potentials of Alpinia GalangaDocumento3 páginas62 Medicinal Potentials of Alpinia GalangaM.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- 59 (Helicobacter PyloriDocumento5 páginas59 (Helicobacter PyloriM.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- 54 Sinusitis (JMPR 11 184sajid Khan)Documento9 páginas54 Sinusitis (JMPR 11 184sajid Khan)M.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- 61 (myrtusJMPR 11 250Documento3 páginas61 (myrtusJMPR 11 250M.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- 58 (Prev of Hep Iqb JMPR-11-307Documento3 páginas58 (Prev of Hep Iqb JMPR-11-307M.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- 56 Althae JMPR-11-329Documento5 páginas56 Althae JMPR-11-329M.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- 55 glyceyrrhizaJMPR 11 219Documento4 páginas55 glyceyrrhizaJMPR 11 219M.Akram TatriAinda não há avaliações

- Daftar Pustaka: Poltekkes Kemenkes YogyakartaDocumento6 páginasDaftar Pustaka: Poltekkes Kemenkes YogyakartaNurhadi KebluksAinda não há avaliações

- WHO 2019 nCoV Vaccination Microplanning 2021.1 EngDocumento81 páginasWHO 2019 nCoV Vaccination Microplanning 2021.1 Engdr.tabitaAinda não há avaliações

- Readmissions Final ReportDocumento46 páginasReadmissions Final ReportRiki Permana PutraAinda não há avaliações

- CASE STUDY of HCDocumento3 páginasCASE STUDY of HCAziil LiizaAinda não há avaliações

- Drugs in Europe-EUDocumento43 páginasDrugs in Europe-EUDenisa Elena AAinda não há avaliações

- Pathology Item CardDocumento2 páginasPathology Item CardBir Mohammad SonetAinda não há avaliações

- OBGYN End of Rotation Exam OutlineDocumento35 páginasOBGYN End of Rotation Exam OutlinehevinpatelAinda não há avaliações

- Second Degree Burn Injury in A CowDocumento2 páginasSecond Degree Burn Injury in A CowvetarifAinda não há avaliações

- Application CoopMED Health Insurance Plan BarbadosDocumento2 páginasApplication CoopMED Health Insurance Plan BarbadosKammieAinda não há avaliações

- Barodontalgia 2009Documento6 páginasBarodontalgia 2009Maganti Sai SandeepAinda não há avaliações

- Full Text 01Documento44 páginasFull Text 01ByArdieAinda não há avaliações

- Download ebook Cohens Pathways Of The Pulp 12Th Edition Pdf full chapter pdfDocumento67 páginasDownload ebook Cohens Pathways Of The Pulp 12Th Edition Pdf full chapter pdfchristopher.jenkins207100% (25)

- Ayurveda Association of Singapore SWOT AnalysisDocumento15 páginasAyurveda Association of Singapore SWOT AnalysisOng Saviour NicholasAinda não há avaliações

- Intensive-Care Unit: TypesDocumento2 páginasIntensive-Care Unit: TypesRavi KantAinda não há avaliações

- PhilHealth Hospital Accreditation ChecklistDocumento14 páginasPhilHealth Hospital Accreditation Checklistamira_hassan100% (1)

- Risk Dementia EngDocumento96 páginasRisk Dementia EngsofiabloemAinda não há avaliações

- Peptic Ulcer Disease: Learning ObjectivesDocumento7 páginasPeptic Ulcer Disease: Learning ObjectivesMahendraAinda não há avaliações

- B.SC NURSING SubjectWiseDocumento105 páginasB.SC NURSING SubjectWiseGeorge9688Ainda não há avaliações

- The Use of Acupuncture With in Vitro Fertilization: Is There A Point?Documento10 páginasThe Use of Acupuncture With in Vitro Fertilization: Is There A Point?lu salviaAinda não há avaliações

- The Impact of Depression Among Students in Iplc Senior High School-1Documento3 páginasThe Impact of Depression Among Students in Iplc Senior High School-1Roxanne TongcuaAinda não há avaliações

- Case Study Bronchial Asthma-1Documento13 páginasCase Study Bronchial Asthma-1Krishna Krishii AolAinda não há avaliações

- Student's Handbook 2014Documento52 páginasStudent's Handbook 2014Ahmed MawahibAinda não há avaliações

- Kendriya Vidyalaya Rae BareliDocumento21 páginasKendriya Vidyalaya Rae BareliRishabh TiwariAinda não há avaliações

- Maternity Newborn Diagnoses ICD-9 To ICD-10-CM Code TranslationDocumento3 páginasMaternity Newborn Diagnoses ICD-9 To ICD-10-CM Code TranslationNathanael ReyesAinda não há avaliações

- Nursing Career Ladder System in Indonesia The Hospital ContextDocumento9 páginasNursing Career Ladder System in Indonesia The Hospital Contextners edisapAinda não há avaliações

- Workplace Training BrochureDocumento12 páginasWorkplace Training BrochuremahedAinda não há avaliações