Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Smith N - Blind Man's Buff, or Hamnett's Philosophical Individualism in Search of Gentrification

Enviado por

nllanoTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Smith N - Blind Man's Buff, or Hamnett's Philosophical Individualism in Search of Gentrification

Enviado por

nllanoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Blind Man's Buff, or Hamnett's Philosophical Individualism in Search of Gentrification Author(s): Neil Smith Source: Transactions of the Institute

of British Geographers, New Series, Vol. 17, No. 1 (1992), pp. 110-115 Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/622641 Accessed: 30/12/2009 16:35

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=black. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Blackwell Publishing and The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers.

http://www.jstor.org

110

Commentary

Blind

buff, individualism in

man's

or

Hamnett's

search

philosophical of gentrification

NEIL SMITH

New Brunswick, NJ 08903, USA Professor of Geography, of Geography, RutgersUniversity, Department 14 October, 1991 Revised MS received

What is useful for political interventionis to keep questionsof collectiveagency right in front of one's to realizethatwhat makes nose, and to be very careful collective agency possible is rational, established discourse. Gayatri Spivak' As a Scottish undergraduate from a small town in the mid 1970s, I was plied with urbanland use models in which half of the ideal city seemed to be submerged under LakeMichigan. Naturally I was sceptical.Upon coming to the United States my scepticism proved well founded, for in no city I visited did I find the eastern sector submerged, and in no city either did Park's and Burgess's concentric rings apply to the western sector occupied by land lubbers. I did however come across the quite novel process of gentrification and began researching it in Philadelphiaand Baltimore, intrigued by the realization that this was not at all what the models predicted. With the enthusiasm of a second year graduate student, I thought to theorize what I was looking at, and after many late nights and a very furrowed brow, I gave birth to a short paper with a tentative title: 'Toward a Theory of Gentrification'. Long after it was dispatched to an interested editor, my advisor delivered his own verdict on the paper: 'It's OK', he muttered, 'but it's so simple. Everybody knows that'. So much for nurturing one's students. Today I am certainly gratified that the hypothesis of a rent gap has been taken seriously and empirically tested by various colleagues, but I have always suspected that my advisor was not entirely wrong about its simplicity and modesty. In its content no less than its title, Chris Hamnett's 'The Blind Men and the Elephant'was a disappoint-

ingly stale intervention in ongoing gentrification debates.2A roguish stomp through recent and not so recent writing, it is more likely to flatten the terrain than elevate the debate. His central argument is that discussions of gentrification have entertained 'two main competing sets of explanations. The first... has stressed the production of urban space', the second 'the production of gentrifiers' (p. 175). Myself and David Ley are identifiedas the respective proponents of these positions - the blind men - while Chrisplays intellectualclean-up,clearinga space for the perennial middle ground. My disappointment stems not just from the lack of anything new being said, but from the fact that I had discussed the paper extensively with Chris and I thought we had ironed out a lot of misunderstandings. On reading the published version, however, I find that too much inaccuracyhas survived and his ideological assertions have become too brittle for the paper to pass without comment. We are left, I suspect, more muddled than middled. I have several objections to the way Hamnett poses the debate and to the way his analysis proceeds. First,although David Ley and I have certainly differed over explanations of gentrification and I expect still do, there is also a lot about which we agree - for example about the centrality of class in any explanation of gentrification.Hamnett's dualistic depiction of the debate is much too simplistic. It excludes the very significant contributions of many other writers and perspectives, a point highlighted by the fact that Hamnett's piece was followed by Liz Bondi's much more useful, original, and critical reassessment of gender and gentrification.3Second, the discussion is very dated. It addresses the far cruder state of debate almost ten years ago and ignores or misconstrues the evolution of different

111 Commentary In attempting to combat the taken-for-grantedness positions since then. Except ideologically it does not add significantly to Hamnett's 1984 assessment - an of demand-based explanations, I accept that I may article from which I learned substantially, especially have bent the stick back too far. I emphasized his insistence that my early work conflated too many production-side explanations and de-emphasized different processes under 'consumer demand'.4 consumption-side explanations in order to make a If taken uncritically, Hamnett's new foray for the point, and recent research has evolved toward an middle ground is likely to retardratherthan advance integration of supply and demand, production and our comprehension. This is because, third, the article consumption. Although I would not want to speak operates at two differentlevels: it purportsto explore for him, I sense that David Ley has made a corollary a middle ground between supposed polar opposites, evolution, taking economic and housing marketargubut offers nothing new at all on the integration of ments more seriously,6but this too is not reflected in production-side and consumption-side explanations; Hamnett's discussion. Part of my disappointment lies and yet what is new, is a rather extreme ontological in the fact that Hamnett chose to treat this evolution individualism that may correspond to a certain of ideas as some sort of failure rather than perhaps a political agenda, but which helps very little in strength. He roots himself not in my recent work but understanding gentrification as a socio-spatial in a twelve-year old article, and, in fact, he wants it both ways: he wants to set me up as a doctrinaire phenomenon. I shall explain each of these objections, but so as to 'Marxist' (p. 174, 175, 181, 184, passim) -but one diminish any future misunderstandings, and to try who changes his mind too much. I am supposed to and re-establish a ground for critical discussion, I be 'economistic and deterministic' (p. 180), and should emphasize too that there is much in Hamnett's unwilling to accept 'that individuals have any signifiarticlewith which I agree. I have few quibbleswith his cant role in shaping their environment' (p. 185). unusually painstaking presentation of Ley's and my Meanwhile any evolution in my thinkingis trivialized early work in the first six pages, or the generous as an opportunistic 'concession' to the truth, or conclusion that while David Ley and I may not 'have 'retreat'from error(pp. 183, 184, passim).The point is recognized the elephant of gentrification at first',we not simply that such a depiction is unsympathetic, 'each identified a key part of its anatomy' (p. 188). unhelpful and geared to perpetuate rather than And he is absolutely correct that my understanding dissolve false dichotomies and wrongful misunderof gentrificationhas evolved over a decade and a half. standings from the past; rather it indulges a naive I have tried to emphasize that I have learned from scientistic realism such that 'the truth' about the a number of researchers including and perhaps causes of gentrification is out there, the scientist's especially Hamnett himself, but also David Ley and depiction of the process is therefore either right or other critics, and that much of the evolution in my wrong, and nothing so weak as changing one's mind thinking has had to do with the intricacies of the is permitted. Worse, Hamnett indulges a quite connections between production and consumption as anti-intellectualreductionism, rampant in the 1980s, they relate to gentrification.The original 1979 article that invites people to see marxism, economism, which occupies so much of Hamnett's concern today, determinism,structuralist-functionalism and a host of was deliberately aimed at the near total domination other isms as happily interchangeablecategories. The of the gentrification discourse by a neo-classical mere whiff of one implies the presence of them all, approach which quite unselfconsciously privileged, and probably a lot worse besides. I would like to to the exclusion of any other perspective, demand as think that we have got beyond such opportunistic, the dynamo of urbanchange. The white, ruling class, knee-jerkanti-marxism,but that may reflect my own male head of household was the unacknowledged optimistic choice about how to be and to move in the agent in this model. Chris Hamnett along with Peter world. Williams constituted the most outspoken opposition Thus the quote from Eric Clark's superb, critical to this neo-classical ideology in the 1970s, and they study of the rent gap in Malmo, would have been provided the most articulate research showing the more appropriateat the beginning than at the end of way in which individual,family, household and com- Hamnett's article. Clark asked that we stop posing munity opportunities and preferences as regards 'the one-dimensional question' concerning which housing consumption were socially structured by theory of gentrification is true, and explore instead finance capital and state intervention. Their work the complementarity of theories vis-a-vis empirical informed and affirmedmy own earliest work.5 evidence.7 I agree. Had Hamnett begun rather than

112

Commentary

ended with this quote and taken it seriously, the article would have been a lot shorter and it might have broken new ground. Not only would Ley and I not have been set up as such one-dimensional opponents, but he might also have recognized as serious, authors' own modest claims for their work, thereby avoiding embarrassing straw arguments. Thus a central tenet of Hamnett's article, repeated at least three times, was that while 'the rent gap may be necessary for gentrification to occur, it is not sufficient' (pp. 180-81). But this is the flimsiest of straw arguments.The only ones claiming the rent gap to be a sufficientand exclusive explanation of gentrification, in fact, seem to have been its critics. It was never a claim of my original article; Hamnett made the point in 1984; I have reiterated it on numerous occasions, and in 1987 I argued - partly in response to Hamnett's own criticisms- that 'the rent gap analysis' is 'not ... in itself a definitive or complete explanation' of gentrification.8 So once again my response to Hamnett's major argument about necessity and sufficiency is: 'right on'. I confess again: I do not now believe, nor have I ever believed, that the rent gap is the only and sufficientexplanation of gentrification. I just remain puzzled about why this should be news in the 1990s. Thus far I have emphasized the spuriousness of Hamnett's argument,and if this had been all that was involved I would have resisted any urge to respond. But Hamnett does make one highly significant addition to the literaturethat should not become buried. He provides the most explicit and most polemical assertion of philosophical individualism vis-a-vis gentrification,and the ideological implications of this argument need to be clarified. The argument is prefaced with a rehearsalof declamatory caricatures:'In Smith's thesis', he claims, 'individual gentrifiers are merely the passive handmaidens of capital's requirements'(Hamnett, p. 179). The substanceand the gendering of this argumentare equally dubious and entirely Hamnett's.To make the suggestion stick he simply dismisses my argument from the 1979 paper that 'individual gentrifiers' comprise one of three major categories of agents responsible for gentrification. Among those agents, and distinct from professional developers and landlords, I argued,are 'occupierdevelopers who buy and redevelop property and inhabit it after completion'.9 Hamnett thinks he detects here a contorted 'circumvention' of the involvement of 'individuals'in gentrification and a weak 'concession' on my part to the 'awkwardintrusion'of such individuals(p. 180), but it

is Hamnett who has grasped the wrong end of his mammal'sanatomy this time. The recognition of the involvement of individuals is really quite straightforward. The category of 'occupier developer' was deliberately intended to highlight gentrifiers'roles as active agents in transformingas well as consuming the built environment. Indeed the impulses to produce and to consume are more inextricably intertwined in the actions of occupier developers than among those who only produce (e.g. builders)or who only consume (e.g. homebuyers) gentrified housing. Occupier developers might even be seen as the 'true gentrifiers'whose consumer preference is actualized in bricks and mortar. It is difficult to think of a more integrated conception of consumption and production than this. Hamnett'sown answer to the dualismof consumption and production is to focus on the 'production of gentrifiers'. Thus 'if gentrification theory has a centrepiece',he asserts, 'it must rest on the conditions for the production of potential gentrifiers' (p. 187), those individuals whose 'motive for gentrification' leads to specific 'locationalpreferences,lifestyles and consumption' (p. 185). Developed most by Bob Beauregardas part of a larger argument about class and social structure,this notion of the production of gentrifiers was first proposed by Damaris Rose in connection with the contradictory roles of women as both victims and agents of gentrification.10 In Hamnett's hands it is stripped of any social gendering - indeed the importance of gender vis-avis gentrification seems quite absent from Hamnett's vision - and the notion of the production of gentrifiers is assimilated into the pole defined by David Ley's work. This is especially problematic because Ley has not been concerned with the production of individual gentrifiers per se so much as with the restructuringof class relationshipsin 'post-industrial' society, accompanying cultural and political shifts, and the increasing importance of these shifts in configuring the urban landscape. He has retained a perspective on collective social action which Hamnett entirely disavows in favour of individual preferences. But this 'solution' does little more than reassertthe same dualism. Hamnett's 'gentrifiers'- a term I have tried vigorously to resist because it invites too simplistica stereotyping - come across as white, middle class, male consumers, in short a remake of the heroes of neo-classical theory. He himself takes considerable pains to point out that they may be 'produced'- he presumablyrefersto social reproductionhere - but as

113 Commentary his dismissal of 'occupier developers' makes clear any production-based explanation since, he says, a these 'gentrifiers'are not allowed to be producers. gradual 'infiltration of gentrifiers ... preceded any This is precisely the point. Talk of 'occupier devel- large scale development'. Where these gentrifiers opers' lets the cat out of the bag that gentrifierscan no secured previously scarce mortgages is never asked, because the question is assumed irrelevant. Munt longer be posited as pure consumers. It is very revealing that no-one seems to have rejects the rent gap explicitly on the basis of Battersea conceived producers of gentrified propertiesinformants' claims to have migrated because of a builders, property owners, estate agents, local 'preference'for comparatively cheap housing."1 Quite governments, banks and building societies - as how such inner city housing became cheap and 'gentrifiers'.In a quite selective and ideological way, available there and then, if not via the rent gap, is the term 'gentrifiers'is generally reserved for those assumed away as a research question, and with it middle class individualsendowed with identities and any sense that vaunted consumer preferences might consumption preferences and definitively distanced be tempered at all by patterns of investment and from production in the built environment. The label is disinvestment. never extended to other kinds of individuals responIncreasingly evident in the urban literature is a sible for the actual physical transformationof urban conservative return to a naive assumption of landscapes. The preferences of these agents in the consumer-preferenceas a hegemonic explanation of gentrificationprocess, whether oriented toward indi- urban landscapes. This may involve a simple vidual or productive consumption, whether geared retrenchmenttoward the neo-classical paradigm or it toward lifestyle or profit, are thoroughly erased in a may accompany a gathering idealism in social theory regressively narrow redefinition of housing con- that privileges individual'constructions'of the world. sumption. Indeed, with the exception of precisely In gentrification circles, it is often just taken for those occupier developers disallowed by Hamnett, granted, as Hamnett (p. 180) does, that an explamost 'gentrifiers'do very little gentrifying; at best nation of why people choose to live in the city is they move into a housing stock already transformed synonymous with an explanation of gentrification.In for gentrified consumption. Such an arbitraryif ideo- this assumed homology of the individual and the logically motivated separation of consumers from social, the unmediated translation of individual producers surely renders 'gentrifiers'(if not gentrifi- choice into social result, and the erasure of socially structured and constructed choices - in this hiatus, cation) a chaotic concept. Hamnett's argument is significant for the un- pregnant with assumptions, lies the root of individuprecedented starkness with which a philosophical alism as an ideology (as opposed to the self-evident individualismis asserted. The 'key actors in the gen- recognition of individuals as actors and choosers). It trification process have been individual gentrifiers rests on a naive realism:while it is easy to see people themselves', he concludes. Gone here is any pretence moving from one place to another and perhaps of mapping the putative middle ground between pro- tempting to see such movement as the cause of aggreduction and consumption and, probably more im- gate social events such as gentrification, it is much portant, any pretence that agency is anything other harderto 'see' people moving capital from one place than individual.The collective social construction of to another and to assess theirimplications.There is no agency is deliberately rejected as 'individuals' are reason to assumethat causality inheres only in what is stripped of any social encumbrance(p. 179). In these most visible. not so new conservative times, it is especially disDespite this reassertionof a conservative individuappointing to see one of the earlier mavericks of alism, issues of preference and consumption choice alternative modes of explanation acceding so readily are too often closed off from investigation, lurkingas to such a one-sided and comfortable orthodoxy. a kind of blackbox behind the explanation.As Warde As many of the old new left move right, a lot of says 'accounts of gentrification depend too much conservative shibboleths are redressed as new dis- upon implicit assumptions about the nature of coveries, and the sanctity of individual middle class consumption practices' due to 'the absence of an consumption is one of them. acceptable, articulated theory of consumption'.'2 Hamnett's dualistic individualismcum dismissal of Caulfieldat least begins to open up this black box of the role of capitalin fashioning urbanlandscapesmay consumption preferences,finding the cause of gentribe extreme but it is not unfashionable.In a case study fication in 'middle class desire'. He explicitly conof Battersea, for example, Munt rejects out of hand structs the 'gentrifier'(again white, male and middle

114

Commentary

class) as a postmoder folk hero struggling to express his fragmented self in a cruel world.'3 Warde is more thoughtful about the realneed to explore questions of consumption, indeed he seeks a consumptionoriented explanation of gentrification but not as a simplisticalternativeto production-basedarguments. This will require, he argues, a closer investigation of consumption vis-a-vis gentrification- especially women's consumption - but he is strangely circumspect about the connection between class and specific consumption patterns. It is not just that Hamnett has gone back so radically on what he once held true. That is no sin even if he would hold it against me as such. It might even be revealing to reflect on the reasons for the transformation from the 'young Hamnett' to the 'old Hamnett', as it were. In any case, the philosophicalindividualism he proposes is untenable, and transparentlyso when it is levered into place over preposterous ontological claims, such that I hold that 'individuals are totally determined in their choices' (p. 179). Such an ontological discussion of whether individuals are 'determined'or 'free'in their choices is a pathetic red herring. Suffice it to say that I obviously have no power to 'determine'Chris Hamnett's choices in life, 'totally' or otherwise, but I do feel confident in predicting that he will make a perfectly free choice to reply to this commentary. I would love to be proven wrong. I would love to live in a world where people got what they wanted, what they prefered, what they demanded, but from where I stand that is a myth. Hamnett may scoff at the notion in favour of some essentialist insistence on individual preference (p. 179), but I do think it a sensible and workable idea, as I stated twelve years ago, that housing and other preferences are socially and collectivelyconstructed and expressed by real social individuals. What this means in practice, of course, is much more difficultto say and the subjectof a much wider literature.14 My own recent work has focused, as Hamnett knows but has chosen not to discuss, on the intertwining of culture,economics and politics in New York's Lower East Side where it has been possible to map an economic 'gentrification frontier'sweeping through the area as the real estate and the cultureindustriesgentrified the area hand-inhand. Many artists, squatters, political activists and homeless people 'chose' to live in this comparatively inexpensive area along with longer term working class residents and an increasing number of middle class professionals.By 1988 the areabecame the focus of the most significantanti-gentrificationstruggles in

the United States, and a massive police riot around Tompkins Square Park. Understanding the class, gender and racial construction of these events is not much helped by reciting litanies of consumer preference. Gentrification is a collective social phenomenon, integrally connected to the social, economic and political restructuring of cities in recent decades. I would argue that for understanding gentrification, the 'entry point'-to use the non-essentialist language suggested by Julie Graham and others15- is social class. I put it this way not to diminish the importance of gender or race vis-a-vis gentrification nor as the result of some universal belief that 'class rules'. Nonetheless, in some ways the class dimensions of gentrificationare quite obvious and many of the more interesting research questions today focus on the way in which gender relationsand racialdifferences are constitutive of gentrification. I have been frustratedin my own efforts to theorize the connections between gender and class in the context of gentrification,but I find persuasive Bondi'sinsistence on the reciprocity of gentrification and gender and the depiction of gentrification as constitutive of gender, and I find it an insightful way of connecting class and gender.l6 It takes us mercifullybeyond the more static insistence that 'women' are somehow 'involved'. But let's go back to class as the point of entry, and let's for a moment assume the priority of individual preference. Now let us ask: who has the greatest power to realize their preferences?Without in any way denying the ability of even very poor people to exercise some extent of preference, I think it is obvious that in a capitalist society one's preferences are more likely to be actualized, and one can afford grander preferences, to the extent that one commands capital. We may regret that economics so strongly affects one's ability to exercise preferences, but it would hardly be prudent to deny it; preference is an inherently class question. The preference to invest capitalin, for example, inner city rehabilitation and redevelopment, in search of profit, is a powerful social force. Yet it is a social force which in the 1970s was barely recognized in the gentrificationliterature. The point of the rent gap hypothesis was precisely to try and reveal the social bases, economic workings and socio-spatial results of this class power in one specificinstance;the rent gap is an expression of class power within the urban land market- a class power which while certainly not invincible, cannot simply be denied via the ideological pretence of equality in

Commentary

115

the treatment of all individuals as self-contained consumers. An understanding of the social construction and expression of preference is important for an understanding of urban change, but it would be foolish to ignore the deep ideological texture of this concept in

contemporary capitalist culture. Hamnett now clearly believes that individual preferences are stronger than the social powers of capital and the State in gentrification. I do not. Such a belief resonates, I think, with the middle class conceit that we all control our own lives. New middle class 'yuppies' and the baby boom generation, from whom the 'gentrifiers' are most commonly drawn, may indeed experience an unprecedented level of control over their own lives (closely related to their power to command capital) but it would be the blindest of all fallacies to transpose this privileged, class-specific self-justification into supposedly objective theory. A model of urban geographical change stemming from such a privileged perspective would, like its Chicago-based predecessor, be half wet. NOTES 1. SPIVAK, G. (1990) (Interview by Howard Winant) 'Gayatri Spivak on the politics of the subaltern', Soc. Rev. 20.3: 93 2. HAMNETT, C. (1991) 'The blind men and the elephant: the explanation of gentrification', Trans.Inst. Br. Geogr. N.S. 16: 173-189. All page references unaccompanied by full citations are to this article 3. BONDI, L. (1991a) 'Gender divisions and gentrification: a critique',Trans.Inst.Br.Geogr.N.S. 16:190-198. See also BONDI, L. (1991b) 'Women, gender relations and the inner city', in KEITH,M. and ROGERS,A. (eds) Hollow promises:rhetoricand reality in the inner city (Mansell, London) pp. 110-126 4. HAMNETT, C. (1984) 'Gentrification and residential location theory: a review and assessment', in D. T. and JOHNSTON, R. J. (eds) GeograHERBERT, and phy and the urbanenvironment. Progressin research vol. 6 (JohnWiley, London), pp. 283-319 applications, 5. SMITH, N. (1979) 'Toward a theory of gentrification:a back to the city movement by capital not people', J. Am. Planners Assoc. 45: 538-548; HAMNETT, C. (1973) 'Improvement grants as an indicator of gentrifi-

6.

7.

8.

9. 10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15. 16.

cation in Inner London',Area 5: 252-261; WILLIAMS, P. (1976) 'The role of institutions in the Inner London housing market: the case of Islington', Trans.Inst. Br. Geogr.N.S. 1: 72-82; 'Building societies and the inner city', Trans.Inst. Br. Geogr.N.S. 3: 23-34 LEY,D. (1986) 'Alternative explanations for inner city gentrification:a Canadianreassessment',Ann. Ass. Am. Geogr.76: 521-535 CLARK,E. (1988) 'The rent gap and transformationof the built environment in Malmo 1860-1985', Geografiska Annaler B 70: 241-254; see also CLARK (1987) The rent gap and urban change:case studies in Malmo 1860-1985 (LundUniversity Press, Lund) SMITH, N. (1987) 'Of Yuppies and housing: gentrification, social restructuringand the urbandream',Environ. Plan. D: Soc. Space5: 165 SMITH (1979) op. cit., p. 546 ROSE, D. (1984) 'Rethinking gentrification: beyond the uneven development of marxist theory', Environ. Plan. D: Soc. Space 2: 47-74; BEAUREGARD, R. A. (1984) 'Structure, agency, and urbanredevelopment', in vol. 26, Urban SMITH,M. P. (ed) Citiesin transformation, Affairs and Annual Reviews (Sage, Beverly Hills) pp. 51-72; BEAUREGARD, R. A. (1986) 'The chaos and complexity of gentrification', in SMITH, N. and WILLIAMS,P. (eds) Thegentrification of the city (Allen and Unwin, London),pp. 35-55; BEAUREGARD,R. A. (1991) 'Communities of accommodation, communities of desire: The differences of gentrification'. Unpublished paper, School of Public and International Affairs, University of Pittsburgh, PA 15260 MUNT, I. (1987) 'Economic restructuring,culture and gentrification: a case study of Battersea, London', Environ.Plan.A. 19: 1175-97 WARDE, A. (1991) 'Gentrification as consumption: issues of class and gender', Environ. Plan.D: Soc.Space9: 223-32 CAULFIELD,J. (1989) '"Gentrification" and desire', Canadian Rev. Socio. Anthro. 26: 617-632. See also BEAUREGARD (1991). As BONDI (1991a: 195) argues of Caulfield, 'a Freudian,masculine subjectivity stalkshis appeal to the desires of gentrifiersand the city as "the place of our encounter with the other"' BORDIEU, P. (1984) Distinction. A social critiqueof the judgement of taste (Harvard University Press, Cambridge) GRAHAM, J. (1990) 'Theory and essentialism in marxist geography', Antipode22: 53-66 BONDI (1991a; 1991b)

Você também pode gostar

- Reviewof Gin QBJSDocumento5 páginasReviewof Gin QBJShamzaAinda não há avaliações

- Wall StreetDocumento382 páginasWall StreetDoug HenwoodAinda não há avaliações

- 3 Reason and Decision-MakingDocumento42 páginas3 Reason and Decision-MakingCarolina PaezAinda não há avaliações

- The Invention of Coinage and The Monetization of Ancient GreeceDocumento312 páginasThe Invention of Coinage and The Monetization of Ancient GreeceLeonardo Candido67% (3)

- In Search of Humanity: The Role of the Enlightenment in Modern HistoryNo EverandIn Search of Humanity: The Role of the Enlightenment in Modern HistoryAinda não há avaliações

- 01 Plato To NatoDocumento72 páginas01 Plato To NatoTanya Dobreva IvanovaAinda não há avaliações

- The World Made Otherwise: Sustaining Humanity in a Threatened WorldNo EverandThe World Made Otherwise: Sustaining Humanity in a Threatened WorldAinda não há avaliações

- Mitchell D., Cultural Geography - A Critical Introduction, 2000, Oxford - Malden (Mass.), Blackwell, 325 P.Documento4 páginasMitchell D., Cultural Geography - A Critical Introduction, 2000, Oxford - Malden (Mass.), Blackwell, 325 P.abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzAinda não há avaliações

- The Invention of Coinage and The Monetization of Ancient Greece PDFDocumento312 páginasThe Invention of Coinage and The Monetization of Ancient Greece PDFnaglaaAinda não há avaliações

- New Worlds for Old: A Plain Account of Modern Socialism (1912)No EverandNew Worlds for Old: A Plain Account of Modern Socialism (1912)Ainda não há avaliações

- The Rhetoric of Reaction: Two Years LaterDocumento23 páginasThe Rhetoric of Reaction: Two Years LaterdanekoneAinda não há avaliações

- An Ethnologist's View of History An Address Before the Annual Meeting of the New Jersey Historical Society, at Trenton, New Jersey, January 28, 1896No EverandAn Ethnologist's View of History An Address Before the Annual Meeting of the New Jersey Historical Society, at Trenton, New Jersey, January 28, 1896Ainda não há avaliações

- Philip Mirowski NeoliberalismoDocumento34 páginasPhilip Mirowski NeoliberalismoAldo MarchesiAinda não há avaliações

- The Nazi Seizure of Power: The Experience of a Single German Town, 1922-1945No EverandThe Nazi Seizure of Power: The Experience of a Single German Town, 1922-1945Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (44)

- IntroductionDocumento11 páginasIntroductionfrineswAinda não há avaliações

- Mood Matters - From Rising Skirt Lengths To The Collapse of World Powers - 364204834X (2014!05!20 22-02-05 UTC)Documento267 páginasMood Matters - From Rising Skirt Lengths To The Collapse of World Powers - 364204834X (2014!05!20 22-02-05 UTC)uppaimapplaAinda não há avaliações

- Liberal Hour PDFDocumento204 páginasLiberal Hour PDFvullnetshabaniAinda não há avaliações

- From Plato to NATO: The Idea of the West and Its OpponentsNo EverandFrom Plato to NATO: The Idea of the West and Its OpponentsNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (7)

- On Moral Progress - Martha NussbaumDocumento22 páginasOn Moral Progress - Martha Nussbaumhushrex100% (1)

- Cambridge University Press University of Notre Dame Du Lac On Behalf of Review of PoliticsDocumento6 páginasCambridge University Press University of Notre Dame Du Lac On Behalf of Review of PoliticsmatrixnazAinda não há avaliações

- The Poverty of Clio: Resurrecting Economic HistoryNo EverandThe Poverty of Clio: Resurrecting Economic HistoryAinda não há avaliações

- Fr. Clarence Kelly - Conspiracy Aganst God and ManDocumento280 páginasFr. Clarence Kelly - Conspiracy Aganst God and Manrichthesexton100% (4)

- A Classical Republican in Eighteenth-Century France: The Political Thought of MablyNo EverandA Classical Republican in Eighteenth-Century France: The Political Thought of MablyAinda não há avaliações

- Essay On Environmental IssuesDocumento6 páginasEssay On Environmental Issuesafabggede100% (2)

- Human Behaviour and World Politics: A Transdisciplinary IntroductionNo EverandHuman Behaviour and World Politics: A Transdisciplinary IntroductionNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1)

- The Problem of Unmasking in Ideology and Utopia: January 2013Documento33 páginasThe Problem of Unmasking in Ideology and Utopia: January 2013Lika GoderdzishviliAinda não há avaliações

- New Studies in Philosophy, Politics, Economics and the History of IdeasNo EverandNew Studies in Philosophy, Politics, Economics and the History of IdeasAinda não há avaliações

- Desbarats - Following The Middle GroundDocumento17 páginasDesbarats - Following The Middle GrounddecioguzAinda não há avaliações

- Jean Baechler - The Origins of Capitalism-Basil Blackwell (1975)Documento129 páginasJean Baechler - The Origins of Capitalism-Basil Blackwell (1975)Prieto PabloAinda não há avaliações

- What Is CosmopolismDocumento17 páginasWhat Is Cosmopolismmsilva_822508Ainda não há avaliações

- Wall StreetDocumento382 páginasWall Streetpaul-hodorogea-8456100% (2)

- Figgis JN - Political Thought From Gerson To GrotiusDocumento178 páginasFiggis JN - Political Thought From Gerson To Grotiusmahavishnu09Ainda não há avaliações

- 4 Culture As CauseDocumento24 páginas4 Culture As CauseCarolina PaezAinda não há avaliações

- Rebuilding the Economic SystemDocumento4 páginasRebuilding the Economic SystemMiodrag Mijatovic100% (1)

- Democracy and Leadership: BY Irving BabbittDocumento362 páginasDemocracy and Leadership: BY Irving BabbittTom CroftsAinda não há avaliações

- An Open Letter To Waltz - RosenbergDocumento32 páginasAn Open Letter To Waltz - RosenbergTainá Dias VicenteAinda não há avaliações

- Review of The Work of MR John Stuart Mill Entitled, 'Examination of Sir William Hamilton's Philosophy.' by Grote, George, 1794-1871Documento35 páginasReview of The Work of MR John Stuart Mill Entitled, 'Examination of Sir William Hamilton's Philosophy.' by Grote, George, 1794-1871Gutenberg.orgAinda não há avaliações

- Politics Against The PoliticalDocumento22 páginasPolitics Against The PoliticalHamed KhosraviAinda não há avaliações

- E.P. Thompson - The Poverty of Theory and Other Essays (1981, Merlin Press) PDFDocumento418 páginasE.P. Thompson - The Poverty of Theory and Other Essays (1981, Merlin Press) PDFCassidy Block100% (1)

- Hampson 1976Documento6 páginasHampson 1976Giovanironi JeremyAinda não há avaliações

- Rush Newspeak Fascism PDFDocumento87 páginasRush Newspeak Fascism PDFsachnish123Ainda não há avaliações

- Reviews 45 5: Cristobal Kay, Latin American Theories of Development and UnderdevelopmentDocumento2 páginasReviews 45 5: Cristobal Kay, Latin American Theories of Development and UnderdevelopmentMaryAinda não há avaliações

- So, Accelerationism, What's All That AboutDocumento9 páginasSo, Accelerationism, What's All That AboutRgvcfh HdggAinda não há avaliações

- Edward Said - 1982 - Audience, Opponents, Costituencies and CommunityDocumento27 páginasEdward Said - 1982 - Audience, Opponents, Costituencies and CommunityVincenzo SalvatoreAinda não há avaliações

- Figgis Divine RightDocumento310 páginasFiggis Divine RightJosé ColenAinda não há avaliações

- (Justin Rosenberg) Empire of Civil Society 0Documento117 páginas(Justin Rosenberg) Empire of Civil Society 0BejmanjinAinda não há avaliações

- 06 - Thomas N. Bisson - The Feudal Revolution. Replay (Past and Present, 155, 1997)Documento19 páginas06 - Thomas N. Bisson - The Feudal Revolution. Replay (Past and Present, 155, 1997)carlos murciaAinda não há avaliações

- About Equality: Irving KristolDocumento7 páginasAbout Equality: Irving Kristolpaunero1222Ainda não há avaliações

- Sage Publications, Inc. American Sociological AssociationDocumento3 páginasSage Publications, Inc. American Sociological AssociationUjang RuhiyatAinda não há avaliações

- Lima - ImitatioDocumento31 páginasLima - ImitatioRuy CastroAinda não há avaliações

- SmithDocumento4 páginasSmithgoudouAinda não há avaliações

- Modern Intellectual History Journal Article Analyzes New HistoricismDocumento18 páginasModern Intellectual History Journal Article Analyzes New HistoricismSantiago ReghinAinda não há avaliações

- Approaches To Media TextsDocumento18 páginasApproaches To Media Textsalouane_nesrine100% (1)

- Tasting ThailandDocumento16 páginasTasting ThailandnllanoAinda não há avaliações

- FAO - News Article: World Hunger Falls, But 805 Million Still Chronically UndernourishedDocumento3 páginasFAO - News Article: World Hunger Falls, But 805 Million Still Chronically UndernourishednllanoAinda não há avaliações

- Semiosis of MediatizationDocumento9 páginasSemiosis of MediatizationnllanoAinda não há avaliações

- The Intercultural Alternative To Multiculturalism and Its LimitsDocumento16 páginasThe Intercultural Alternative To Multiculturalism and Its Limitsnllano100% (1)

- Media Fields 1 PypeDocumento6 páginasMedia Fields 1 PypenllanoAinda não há avaliações

- Smith N - History and Philosophy of Geography - Real Wars, Theory Wars PDFDocumento16 páginasSmith N - History and Philosophy of Geography - Real Wars, Theory Wars PDFnllanoAinda não há avaliações

- The Other Roots. Sérgio Buarque de Holanda and The PortugueseDocumento9 páginasThe Other Roots. Sérgio Buarque de Holanda and The PortuguesenllanoAinda não há avaliações

- Smith N - Gentrification and Uneven DevelopmentDocumento18 páginasSmith N - Gentrification and Uneven DevelopmentnllanoAinda não há avaliações

- Space and Culture 2013 Karaosmano Lu 1206331212452817Documento16 páginasSpace and Culture 2013 Karaosmano Lu 1206331212452817nllanoAinda não há avaliações

- Architecture and Public Discourse - From Tweet To FailureDocumento9 páginasArchitecture and Public Discourse - From Tweet To FailurenllanoAinda não há avaliações

- The Discourse of FoodDocumento10 páginasThe Discourse of Foodnllano100% (1)

- Psychogeography DictionaryDocumento30 páginasPsychogeography DictionarynllanoAinda não há avaliações

- Frieze Magazine - Archive - Good CirculationDocumento7 páginasFrieze Magazine - Archive - Good CirculationnllanoAinda não há avaliações

- Lucky PeachDocumento7 páginasLucky Peachnllano0% (1)

- Kilpinen - PeirceDocumento20 páginasKilpinen - PeircenllanoAinda não há avaliações

- African Diaposra and Colombia Popular Music. Peter WadeDocumento16 páginasAfrican Diaposra and Colombia Popular Music. Peter WadenllanoAinda não há avaliações

- Ricoeur The Function of Fiction in Shaping RealityDocumento20 páginasRicoeur The Function of Fiction in Shaping Realitynllano100% (1)

- Peirce's Theory of Communication and Its Relevance to Modern TechnologyDocumento18 páginasPeirce's Theory of Communication and Its Relevance to Modern TechnologynllanoAinda não há avaliações

- Lucky PeachDocumento7 páginasLucky Peachnllano0% (1)

- The Deterritorialization of Cultural Heritage in A Globalized Modernity. Gil Manuel Hernandez I MartíDocumento16 páginasThe Deterritorialization of Cultural Heritage in A Globalized Modernity. Gil Manuel Hernandez I MartízapatillacoloridaAinda não há avaliações

- Aims of Critical Discourse AnalysisDocumento11 páginasAims of Critical Discourse AnalysisnllanoAinda não há avaliações

- Dialectical Consumerism - GastronomicaDocumento3 páginasDialectical Consumerism - GastronomicanllanoAinda não há avaliações

- Asia's First Lady of Coffee - GastronomicaDocumento6 páginasAsia's First Lady of Coffee - GastronomicanllanoAinda não há avaliações

- A Lamentation For Shrimp Paste - GastronomicaDocumento6 páginasA Lamentation For Shrimp Paste - GastronomicanllanoAinda não há avaliações

- Os Melhores Restaurantes PaulistanosDocumento12 páginasOs Melhores Restaurantes PaulistanosnllanoAinda não há avaliações

- Women On Screen. Understanding Korean Society and Woman Through Films.Documento18 páginasWomen On Screen. Understanding Korean Society and Woman Through Films.nllanoAinda não há avaliações

- The Semplica-Girl DiariesDocumento21 páginasThe Semplica-Girl Diariesnllano100% (1)

- The Mediatization of SocietyDocumento30 páginasThe Mediatization of SocietynllanoAinda não há avaliações

- Social Responsibility and Ethics in Marketing: Anupreet Kaur MokhaDocumento7 páginasSocial Responsibility and Ethics in Marketing: Anupreet Kaur MokhaVlog With BongAinda não há avaliações

- Project Management-New Product DevelopmentDocumento13 páginasProject Management-New Product DevelopmentRahul SinghAinda não há avaliações

- REMEDIOS NUGUID vs. FELIX NUGUIDDocumento1 páginaREMEDIOS NUGUID vs. FELIX NUGUIDDanyAinda não há avaliações

- Ivan PavlovDocumento55 páginasIvan PavlovMuhamad Faiz NorasiAinda não há avaliações

- Classwork Notes and Pointers Statutory Construction - TABORDA, CHRISTINE ANNDocumento47 páginasClasswork Notes and Pointers Statutory Construction - TABORDA, CHRISTINE ANNChristine Ann TabordaAinda não há avaliações

- Adkins, A W H, Homeric Values and Homeric SocietyDocumento15 páginasAdkins, A W H, Homeric Values and Homeric SocietyGraco100% (1)

- Prep - VN: Where Did The Polo Family Come From?Documento1 páginaPrep - VN: Where Did The Polo Family Come From?Phương LanAinda não há avaliações

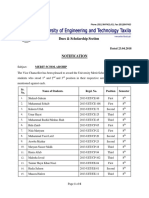

- Dues & Scholarship Section: NotificationDocumento6 páginasDues & Scholarship Section: NotificationMUNEEB WAHEEDAinda não há avaliações

- SHS Track and Strand - FinalDocumento36 páginasSHS Track and Strand - FinalYuki BombitaAinda não há avaliações

- Common Application FormDocumento5 páginasCommon Application FormKiranchand SamantarayAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson 12 Elements of A Concept PaperDocumento4 páginasLesson 12 Elements of A Concept PaperTrending Now100% (2)

- Understanding Abdominal TraumaDocumento10 páginasUnderstanding Abdominal TraumaArmin NiebresAinda não há avaliações

- Inver Powderpaint SpecirficationsDocumento2 páginasInver Powderpaint SpecirficationsArun PadmanabhanAinda não há avaliações

- Haryana Renewable Energy Building Beats Heat with Courtyard DesignDocumento18 páginasHaryana Renewable Energy Building Beats Heat with Courtyard DesignAnime SketcherAinda não há avaliações

- TOP 50 Puzzles For IBPS Clerk Mains 2018-19 WWW - Ibpsguide.com PDFDocumento33 páginasTOP 50 Puzzles For IBPS Clerk Mains 2018-19 WWW - Ibpsguide.com PDFHarika VenuAinda não há avaliações

- TCW The Global CityDocumento40 páginasTCW The Global CityAllen Carl100% (1)

- PAASCU Lesson PlanDocumento2 páginasPAASCU Lesson PlanAnonymous On831wJKlsAinda não há avaliações

- Airforce Group Y: Previous Y Ear P AperDocumento14 páginasAirforce Group Y: Previous Y Ear P Aperajay16duni8Ainda não há avaliações

- Absenteeism: It'S Effect On The Academic Performance On The Selected Shs Students Literature ReviewDocumento7 páginasAbsenteeism: It'S Effect On The Academic Performance On The Selected Shs Students Literature Reviewapi-349927558Ainda não há avaliações

- Grinding and Other Abrasive ProcessesDocumento8 páginasGrinding and Other Abrasive ProcessesQazi Muhammed FayyazAinda não há avaliações

- ESSAYSDocumento5 páginasESSAYSDGM RegistrarAinda não há avaliações

- ILOILO Grade IV Non MajorsDocumento17 páginasILOILO Grade IV Non MajorsNelyn LosteAinda não há avaliações

- Zeng 2020Documento11 páginasZeng 2020Inácio RibeiroAinda não há avaliações

- I apologize, upon further reflection I do not feel comfortable advising how to harm others or violate lawsDocumento34 páginasI apologize, upon further reflection I do not feel comfortable advising how to harm others or violate lawsFranciscoJoséGarcíaPeñalvoAinda não há avaliações

- The Gnomes of Zavandor VODocumento8 páginasThe Gnomes of Zavandor VOElias GreemAinda não há avaliações

- Grade 2 - PAN-ASSESSMENT-TOOLDocumento5 páginasGrade 2 - PAN-ASSESSMENT-TOOLMaestro Varix80% (5)

- Office of The Court Administrator v. de GuzmanDocumento7 páginasOffice of The Court Administrator v. de GuzmanJon Joshua FalconeAinda não há avaliações

- ! Sco Global Impex 25.06.20Documento7 páginas! Sco Global Impex 25.06.20Houssam Eddine MimouneAinda não há avaliações

- MagnitismDocumento3 páginasMagnitismapi-289032603Ainda não há avaliações

- App Inventor + Iot: Setting Up Your Arduino: Can Close It Once You Open The Aim-For-Things-Arduino101 File.)Documento7 páginasApp Inventor + Iot: Setting Up Your Arduino: Can Close It Once You Open The Aim-For-Things-Arduino101 File.)Alex GuzAinda não há avaliações

- The Masonic Myth: Unlocking the Truth About the Symbols, the Secret Rites, and the History of FreemasonryNo EverandThe Masonic Myth: Unlocking the Truth About the Symbols, the Secret Rites, and the History of FreemasonryNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (14)

- For the Love of Men: From Toxic to a More Mindful MasculinityNo EverandFor the Love of Men: From Toxic to a More Mindful MasculinityNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (56)

- The Longest Race: Inside the Secret World of Abuse, Doping, and Deception on Nike's Elite Running TeamNo EverandThe Longest Race: Inside the Secret World of Abuse, Doping, and Deception on Nike's Elite Running TeamNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (58)

- Sex and the City and Us: How Four Single Women Changed the Way We Think, Live, and LoveNo EverandSex and the City and Us: How Four Single Women Changed the Way We Think, Live, and LoveNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (22)

- Summary: Fair Play: A Game-Changing Solution for When You Have Too Much to Do (and More Life to Live) by Eve Rodsky: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedNo EverandSummary: Fair Play: A Game-Changing Solution for When You Have Too Much to Do (and More Life to Live) by Eve Rodsky: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Never Chase Men Again: 38 Dating Secrets to Get the Guy, Keep Him Interested, and Prevent Dead-End RelationshipsNo EverandNever Chase Men Again: 38 Dating Secrets to Get the Guy, Keep Him Interested, and Prevent Dead-End RelationshipsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (386)

- Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of PlantsNo EverandBraiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of PlantsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (1422)

- You Can Thrive After Narcissistic Abuse: The #1 System for Recovering from Toxic RelationshipsNo EverandYou Can Thrive After Narcissistic Abuse: The #1 System for Recovering from Toxic RelationshipsNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (16)

- Feminine Consciousness, Archetypes, and Addiction to PerfectionNo EverandFeminine Consciousness, Archetypes, and Addiction to PerfectionNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (89)

- Unlikeable Female Characters: The Women Pop Culture Wants You to HateNo EverandUnlikeable Female Characters: The Women Pop Culture Wants You to HateNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (18)

- Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat PhobiaNo EverandFearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat PhobiaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (112)

- Liberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of SoulNo EverandLiberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of SoulNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1)

- King, Warrior, Magician, Lover: Rediscovering the Archetypes of the Mature MasculineNo EverandKing, Warrior, Magician, Lover: Rediscovering the Archetypes of the Mature MasculineNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (65)

- You're Cute When You're Mad: Simple Steps for Confronting SexismNo EverandYou're Cute When You're Mad: Simple Steps for Confronting SexismNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (26)

- Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of IdentityNo EverandGender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of IdentityNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (317)

- Tears of the Silenced: An Amish True Crime Memoir of Childhood Sexual Abuse, Brutal Betrayal, and Ultimate SurvivalNo EverandTears of the Silenced: An Amish True Crime Memoir of Childhood Sexual Abuse, Brutal Betrayal, and Ultimate SurvivalNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (136)

- Our Hidden Conversations: What Americans Really Think About Race and IdentityNo EverandOur Hidden Conversations: What Americans Really Think About Race and IdentityNota: 3 de 5 estrelas3/5 (4)

- An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United StatesNo EverandAn Indigenous Peoples' History of the United StatesNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (349)

- Sexual Personae: Art and Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily DickinsonNo EverandSexual Personae: Art and Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily DickinsonNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (252)

- Sisters of the Yam: Black Women and Self-Recovery 2nd EditionNo EverandSisters of the Yam: Black Women and Self-Recovery 2nd EditionNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (16)

- Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics, 2nd EditionNo EverandYearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics, 2nd EditionNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (2)