Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

About You

Enviado por

Yan Hao NamTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

About You

Enviado por

Yan Hao NamDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

About you: Empathy, objectivity and authority

Lesley Stirling

a,

*, Lenore Manderson

b,1

a

School of Languages and Linguistics, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria 3010, Australia

b

School of Psychology, Psychiatry and Psychological Medicine, Monash University, Victoria 3800, Australia

1. Introduction

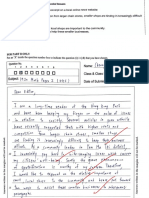

In an interview with a medical anthropologist researching the consequences of bodily change, a woman who had been

treated for breast cancer describes her experience of radiotherapy

2

:

(1)

G: um,

(1.0)

but I used to just lay there and just look up on the-

(0.6)

up on the roof or on-

cos they had this ugly looking picture on the side of the wall?

Journal of Pragmatics 43 (2011) 15811602

A R T I C L E I N F O

Article history:

Received 20 March 2008

Received in revised form 1 December 2010

Accepted 1 December 2010

Available online 13 January 2011

Keywords:

Context

Generalized you

Interaction

Membership categorization

Personal narrative

Repair

A B S T R A C T

This article considers the patterns of usage of generalized you within a corpus of interviews

with women who had undergone mastectomies, mostly following diagnosis of breast

cancer. To date, descriptions of the meanings and functions of generalized you have focused

ontheclassicatoryrather thanthecontextual. Our analysis of discursiveshifts betweenyou

and other forms of reference within one case study interview demonstrates the benets of

microcosmic, interactional analysis for anunderstanding of boththefunctions of youandthe

dynamics of theinteraction. We consider twomainuses of you. Intherst, we surveya range

of instances where generalized you occurs in structural knowledge descriptions, and

illustrate how these function differently in the interactive context depending upon the

contextually delimited membership category at issue. In the second, we consider cases

where segues between use of you and use of I occur in the description of privileged personal

experience bythespeaker, and, inparticular, instances where false starts andrepairs suggest

negotiation of choice between generic and specic frames for the account. We conclude by

reviewing three potentially concurrent interactional functions of generalized you, and

propose that inour data, generalizedyouhas the effect of allowing objectivity withpotential

interactional benets to both participants in the interview.

Crown Copyright 2010 Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +61 3 8344 5192; fax: +61 3 9499 1812.

E-mail addresses: lesleyfs@unimelb.edu.au (L. Stirling), lenore.manderson@med.monash.edu.au (L. Manderson).

1

Tel.: +61 3 9903 4047; fax: +61 3 9903 4508.

2

Names have been changed. In extracts, G stands for the participant we call Glenda, R for the researcher who conducted the interview. We consider it

important to provide sufcient context for examples; key parts of each extract are highlighted via shading.

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Pragmatics

j our nal homepage: www. el sevi er . com/ l ocat e/ pr agma

0378-2166/$ see front matter. Crown Copyright 2010 Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2010.12.002

(0.5)

that people probably-

youd turn your head,

(R): <8huh huh8>

(0.6)

G: and you can see this picture and,

(8it was-8)

(1.2)

just an ugly looking picture but,

(0.7)

something to look at and then [youd]-

R: [yes.]

G: youd h-

youd imagine you were inside that picture?

(0.5)

walking away through the trees,

and the bushes and,

(0.7)

you know youd just have a little bit of time to think about,

R: yeah=

G: =what youre doing in that room-

((tape cuts out))

Glenda opens this passage with a generic narrative about howshe would occupy her attention while the treatment was being

conducted: but I used to just lay there and just look up on the- up on the roof or on- . . .. She then introduces into the discourse, as

a new referent, a particular picture this ugly looking picture on the side of the wall implying that this was an alternative

focus of her attention (. . .or on. . .). The unnished relative clause that people probably. . . gives way to an elaborated

description of the role this picture could play for people having radiotherapy, based on what is clearly her own specic

experience, and indicates a shift to a context of generalizable knowledge and experience. Throughout the ensuing long

passage in which Glenda describes perceptions and mental states based on her own experience, she uses the pronoun you to

refer to the active protagonist and centre of perspectivisation. Such uses are the subject of our article.

The empirical data used are interviews with women who had undergone mastectomies, due to a diagnosis of breast

cancer or less commonly for prophylactic purposes. These interviews are from a larger, ongoing study on bodily change,

chronic disease, disability and social inclusion, which pays particular attention to how individuals gain meaning from their

experiences of surgery, chronic illness and disability, and how they adapt physically and socially to subsequent changes in

bodily appearance and function (cf. Manderson, 1999, 2005; Peake et al., 1999; Peake and Manderson, 2003; Manderson and

Peake, 2005; Manderson et al., 2005). To explore the nature of embodiment, women were purposively recruited from two

Australian states (Victoria and Queensland) through snowballing and personal referral. All study participants were

Australian-born and English speakers, with a mean age of 58 years (range 3578). Women were diverse in terms of education

and employment, however all but one had been married and had children.

Interviews were conducted with 20 of these women at a venue of their choice; interview guidelines were designed to

elicit narratives of illness from the participants through loosely structured questions. Because interviews were often

extremely lengthy, several were conducted over multiple sessions to allow for full accounts of illness, surgery and

subsequent experiences. All interviews were tape-recorded and later transcribed for thematic analysis.

In this article, we focus particularly on four interviews each of approximately 45 min in length, together representing

approximately 3 h of interaction. To allow for detailed micro-analysis, these were re-transcribed in the tradition of

Conversation Analysis. Transcription conventions (based on Jefferson, 1984; Gardner, 2002) are provided in Appendix A. The

program Transcriber was used to segment recordings and measure pause durations.

In our earlier work on the language used in these and similar interviews, we considered the difculties that women face in

speaking of a bodily part no longer present, that is, the breast post-mastectomy (see Manderson and Stirling, 2007). We focus

here on the pattern of usage of generalized you in these interviews. Substantial previous work has been undertaken on

generalized you

3

(e.g. Whitley, 1978; Bolinger, 1979; Laberge and Sankoff, 1979; Kitagawa and Lehrer, 1990; Mu lha usler and

Harre , 1990; OConnor, 1994; Wales, 1996; Kamio, 2001; Bredel, 2002; Predelli, 2004; Hyman, 2004). Our focus here is on

generalized uses of you within contexts of the narration and description of personal experience. The cases we discuss in

3

Other common terms used are impersonal, indenite or generic you.

L. Stirling, L. Manderson / Journal of Pragmatics 43 (2011) 15811602 1582

detail, like the example above, are ones where the speaker has privileged, direct and specic experience of the situation or

situation type being discussed, and yet elects to use you rather than I in this context.

We identied all uses of generalized you compared to other pronominal reference, and undertook a close analysis of the

sequential context in which these occurred, including investigation of co-occurring linguistic phenomena such as tense

forms, markers of genericity such as use of modal auxiliaries, and discourse markers such as you know. In this article we take

one interview, with Glenda, as a case study, in order to present patterns of usage of generalized you throughout an extended,

coherent context. This interview is representative of the other interviews in our corpus, in that the kinds of uses we discuss

are evident in all interviews. However, Glenda makes extensive use of generalized you, while the women varied markedly in

the extent to which they did so. Patterns of individual variation, contextually determined or socially determined variation,

have yet to be properly addressed and will not be discussed here.

Pronoun choice can be seen as an aspect of what has been referred to as membership categorization (Sacks, 1972; Schegloff,

2007) the way in which conversational interactants use social classications to describe and provide an abbreviated form

of reference for the social actors they invoke, as a kind of reication of sub-conscious observations made in their day-to-day

activities. The classic example is Sacks (1972) childs story: The baby cried. The mommy picked it up, where our

commonsense understanding of the categories used (baby, mommy) allows us to infer a good deal of further information

about the participants (e.g. the mommy is the mommy of the baby). It has been shown that pronominal choice sets such as I/

we or (s)he/they can reect indirect categorization of referents as part of one group or another (e.g. Edwards, 2005; Leudar

et al., 2004). Thus in one of Edwards examples, a veterinarian switches between use of I to refer to specic past acts of her

own and we to indicate potential future acts of herself or some other member of the practice. The precise interpretation of we,

in terms of which of the many groups to which the speaker belongs, is context-bound and context-determined.

We propose here that generalized uses of you similarly can be viewed as context-delimited invokers of membership

categories to which the speaker and, depending on context, the addressee, are seen to belong. It is well established that

speakers are attentive to their own and their interlocutors claims to authority for making contributions in interactions (e.g.

Heritage and Raymond, 2005). As Potter (1996) has shown, category membershipbrings withit epistemological entitlement:

certain categories of people, in certain contexts, are treated as knowledgeable (p. 133), establishing entitlement to speak

authoritatively on the topic (p. 138). Category entitlements can be used by speakers to underpin their authority and the

credibility of the descriptions and evaluations which they produce, and also allow them to engage with issues of

accountability and deniability (see also Baker, 2004, who says The artful production of plausible versions using recognizable

membership categorization devices is a profoundly important form of cultural competence p. 175).

In section 2 of this paper we outline the major functional distinctions that have been described in the literature on

generalized you. In section 3 we illustrate the inherent problems with attributing particular functions to individual uses of

generalized you in an interactional context, and use extended discussion of one interaction to indicate the complex mapping

of patterns of specic and generalized framing and how these are associated with choice between the pronoun I and

generalized you.

Despite these complexities, we suggest that a close analysis of use in context, including reference to co-occurring

linguistic phenomena, allows us to take a novel perspective on the function or functions of individual uses of you in

interactional context. In exploring the reasons for pronoun choices such as between I and you, we suggest the relevance of

three functional perspectives on generalized you: an interactional function of recruiting involvement, here empathetic, from

the addressee; an identity-framing and relationship-preserving function of displaying distance and objectivity; and nally

an epistemic, interactional and identity-framing function of displaying authority. All three are made possible by the category

membership invoking nature of generalized you. Finally, we suggest that all three can be viewed as relating to a key

overarching goal of the kind of personal narration we examine here: that it should be regarded as credible and authoritative.

2. The meanings and functions of you

Excluding some work not discussed here which considers second-person narration as a stylistic device used by authors

in literary works (e.g. Morrissette, 1965; Fludernik, 1993; Herman, 1994; DelConte, 2003; Clarkson, 2005), two main types of

approach have been used to describe and account for the use of the generalized you. Most work has been undertaken from

the perspective of linguistic grammar, and we include in this category general grammatical descriptions of the semantics and

pragmatics of the pronoun. We distinguish from this the limited work that has attempted to trace the use and functions of

generalized you within specic discursive contexts (e.g. OConnor, 1994). We begin our investigation by outlining in this

section the major accounts for generalized you which have been given in the literature.

The relevant work in linguistics has focussed on grammatical description, augmented by the consideration of semantic

and pragmatic factors needed to account for this particular use of the second person pronoun, and for other generalized uses

of pronouns. Thus generalized you has been included in various grammars of English (e.g. Jespersen, 1909; Quirk et al., 1985),

as well as being the focus of research articles since Whitley, 1978 (e.g. see Bolinger, 1979; Laberge and Sankoff, 1979;

Kitagawa and Lehrer, 1990; OConnor, 1994; Kamio, 2001; Bredel, 2002; Predelli, 2004; Hyman, 2004). Although Mu lha usler

and Harre (1990) have argued convincingly that any pronoun can be used for any person, grammatical descriptions of

English personal pronouns still represent you as the form used for second person singular and plural reference, and (rightly)

present as primary the deictic referential use of this form to identify a specic addressee or group containing the addressee.

The uses we are interested in are seen as extensions from this central use, and as Siewierska (2004:210ff) points out, are

L. Stirling, L. Manderson/ Journal of Pragmatics 43 (2011) 15811602 1583

found extensively in European and other languages with closed pronoun systems. Kitagawa and Lehrer (1990) note that in

addition to distinguishing generalized uses from specic referential uses, we need to distinguish them from vague uses of

you, as in their attested example, referring to Americans, where the speaker says: Youre I dont mean you personally youre

going to destroy us all in a nuclear war, in which case you is taken to refer to a group of which the addressee is a member and

the disclaimer is needed to absolve the addressee from personal responsibility.

The set of generalized uses of personal pronouns in English implicates we and they as well as you and the more clearly

impersonal one (although see Wales (1996) on specic referential uses of one). Many researchers have argued that these

four pronouns in their generalized uses have informational equivalence and are mutually substitutable, with differences

between them restricted to matters of formality, style and rhetoric. Thus Huddleston (1984:288) describes the generic you

as a stylistically less formal variant of non-deictic one and Kitagawa and Lehrer (1990:741) argue that person shifts

(between we, you, one) occur frequently in spontaneous conversation, testifying to their informational equivalence.

However Bolinger (1979) showed that generalized uses of you cannot always be readily replaced by generalized one, we or

they. In our data, all uses of you are replaceable, albeit with stylistic impact, by one, as Huddleston suggests. Aside from this,

as we illustrate, in our data it is more common to nd person shifts between specic I and generalized you, and whatever

their informational equivalence in context, these are certainly not interactionally equivalent.

There is a major difference between generalized uses of we and you on the one hand and of they on the other: the former

are related to specic deictic uses which include the speaker and addressee in their reference, while uses of they clearly

exclude speaker and addressee. The two participants of the communicative interaction are the speaker and addressee: as

Lyons (1977:638) notes, only these are actually participating in the drama. Primary descriptions of the deictic pronouns I

and you (singular) generally contrast themby saying that I by denition refers to the current speaker and excludes reference

to the current addressee, while you has the opposite meaning, referring to the current addressee and excluding reference to

the current speaker. As Mu lha usler and Harre point out, the grammar of the I-you discourse has long been considered a

basic structural component of human thought, and so the dynamics of this assignment of participant roles has been taken to

have ramications beyond those of grammar (cf. also Mead, 1934/1962; Buber, 1923/1996).

Many authors have also noted that generalized uses of you tend to co-occur with other linguistic phenomena, as part of a

suite of linguistic characteristics epiphenomenal upon the speakers aim at that point in the discourse to present general

information. Hence, it has been noted that you often occurs with the present tense (e.g. Bolinger, 1979). OConnor (1994)

suggests that you is common in and one of the markers of evaluative parts of the narrative (cf. Labov and Waletzky, 1967;

Labov, 1972), and notes its co-occurrence with other linguistic features setting off such segments. These include framing you

know and pauses, grammatical or lexical indicators of hypothetical situations, and other indicators of genericity such as

expressions like always, plural reference, and indeniteness. These uses of you are seen to connect to the grammar of

genericity more generally.

All of these claims represent tendencies rather than absolutes. For instance, it is not the case that generalized you always

occurs with the generic present tense, as Bolinger (1979) and Kitagawa and Lehrer (1990) have pointed out. In the example

withwhichwe began this paper, you indeed co-occurred with the past tense, in this case with the modal verb would, referring

to recurrent past actions and states. Bolinger suggests that it is not so much past tense that is excluded but reference to

specic, individuated events.

Often very general claims are made about the meaning and function of generalized you. One theme is that generalized

you, like the other generalized uses of pronouns, is used to make general statements about the way things are, or to talk in a

universal way about people in general or anyone. This is consistent with its co-occurrence with other linguistic markers of

genericity. In fact, it is rare that generalized you is used with quite such general reference, and more commonly the group at

issue is a contextually dened general subgroup and you means anyone [who falls into the group under discussion]. The

way in which context works to so constrain the group is not usually discussed in detail. It is this usage which relates to the

concept of membership category that we referred to above, as we shall show in the discussion.

Several authors have gone beyond such general characterisations in attempting to make sense of the somewhat chaotic

range of phenomena at issue, by teasing out distinct subtypes of generalized uses of you. These include Kitagawa and Lehrer

(1990) and OConnor (1994). Kitagawa and Lehrer dene three subtypes, which they distinguish as the situational insertion

type (after Laberge and Sankoff, 1979), the moral or truism formulation type, and the life drama type. The three types

OConnor identies are generic you, self-indexing you and involving you.

Kitagawa and Lehrers situational insertion you seems akin to OConnors self-indexing type. It is a kind of structural

knowledge description in which the speaker tells of what commonly happens in a situation, so that its use indicates that the

speakers experience embeds themin a wider class of people, that is, that the experience is only incidentally theirs but could

well be anybodys. Kitagawa and Lehrer argue that these uses of you can be replaced by quantiers such as everyone, anyone

or other impersonal pronouns such as we, one.

Kitagawa andLehrers moral or truismformulation typeis similar except inthat it is prescriptive informulation, andcannot

be replaced by universal quantier expressions. OConnor (1994) calls this generic you you is used to index a common

experience, or make a general moral reection, in the way that the impersonal pronoun one does (you have to take a chance).

In the life drama type identied by Kitagawa and Lehrer, but not found in our data, a generic and impersonal narrative is

produced using you and present/progressive forms of the verb (you are in Egypt admiring the pyramids..); this type they claim

cannot be replaced by either universal quantiers or other impersonal pronouns, and also behaves differently under indirect

quotation. Thus they argue that the three sub-types they dene are distinguished by linguistic tests.

L. Stirling, L. Manderson / Journal of Pragmatics 43 (2011) 15811602 1584

OConnors involving you represents a fourth type of usage not discussed by Kitagawa and Lehrer and generally

somewhat neglected other than in Bolingers (1979) earlier lucid exposition. This type of you is used in speaking of

experiences which the addressee need not reasonably be expected to share, yet the speaker uses you, not I, in a way that I

claim positions both the speaker and the interlocutor as agents. Such a you is an interpersonal, involving you that draws the

interlocutor in (OConnor, 1994:59). This, she says, is the you that appears to vary with I to most closely indicate the

speaker (p. 59).

In similar vein, Bolinger (1979) had argued that you is both generic and normative, and that it enables the speaker to

generalize and personalize at the same time (p. 207); it not only involves identication with the speakers own viewpoint,

but also invites the addressee to share this viewpoint: It is impersonal only in that the rationale for accepting it transcends

us both: I have no right to assume that you will share with me what is not eminently sharable, namely, a norm (p. 205). As

we will show, this type of usage thus makes of generalized you an extremely powerful descriptive device.

Bolinger nevertheless maintained that you is not used for reporting particular events. In fact, he argued that this was the

one constraint described by Whitley (1978), which he felt was not a tendency: the events being described are not specic,

one-time, denite actions and events, but rather habitual, recurrent or repetitive. The kinds of usages OConnor refers to as

involving suggest that this description is not the full story, however, and it is these to which we now turn.

3. Generalized uses of you in our data

Our survey of published descriptions of you in section 2 shows that these have focused for the most part on the

classicatory rather than the contextual, with a plethora of diverse sub-types dened. This has led to seemingly

contradictory claims and apparent disagreements over the functions and properties of generalized you.

In contrast, the approach we take, akin to that of OConnor (1994), prioritises the value of considering the minutiae of the

linguistic interaction. The micro-pattern of usage and shifts in usage within a particular discourse or discourses provides

insight into the range of meanings and functions of you more generally. A particular focus on the subtle web of related but

shifting usages of referring expressions, including I and generalized you, throughout an interaction leads us to observe, for

instance, that there are parts of the interaction where shifts between you and I occur in the context of self-repair by the

interviewee, suggesting internal decision-making as to the specic or generic framing of particular content.

As well as providing insight into the available range of discourse functions of generalized you, this analysis provides a way

of understanding what is happening in the interview. In our case study, Glenda recalls and reects on her experiences of

being diagnosed with breast cancer prior to the birth of her youngest child. Her narrative, as with those of many of the

women in the study, is highly marked for what has been called evaluation, appraisal or stance (e.g. Hunston and Thompson,

2001; Ka rkka inen, 2003, 2006) her epistemic and affective position with respect to the events being described, which is

sometimes quite negative about the health professionals she reports dealing with.

Following recovery and when she felt strong enough, Glenda became involved in a peer support program, and at the time

that she was interviewed, she was regularly speaking to and spending time with other women at earlier stages of treatment.

Consistent with ideas of peer support used in clinical and related medical contexts, she therefore routinely used her own

experience as an exemplar for other women. But in addition, in this interview she was contributing her own experience to a

study on womens experience of breast cancer, and she appeared mindful of her role as a case, and so of matching her

experience with those of others.

She had worked with the anthropologist (the second author) in the past, and their friendship underpins the interview,

such that empathy and trust are implicit. The anthropologist is also a woman, of a similar age, and like Glenda has children

hence some uses of you function here to establish their actual and theoretical common ground. As discussed in a different

context, gender and age can both strongly inuence the tenor, content and direction of interviews (Manderson et al., 2006).

But at the same time, the anthropologist is better educated, and as the researcher, in the context of the interview, the power

differential of the two is signicant. We will show that using you allows Glenda both to establish her own authority and to

recruit the anthropologist into her world at multiple levels.

In this interview, Glenda segues between her own experience and generalizing to the plight of any/all (breast) cancer

patients; this segue is at times cleverly encoded through the juxtaposition in the one utterance of particular/personal

linguistic features and general/inclusive linguistic features.

We observe two main types of use of you in our data. In section 3.1, we will look at uses of you to invoke world knowledge

or the shared knowledge and experience of co-members of particular groups. This usage is in line with the generic uses of you

in structural knowledge contexts discussed in the literature Kitagawa and Lehrers situational insertion and moral or

truism types and OConnors self-indexing or generic types. We nd few examples of the moral or truism type and argue

that despite the classication of these two types as linguistically distinct in previous work, they function similarly from an

interactional point of view. We look in detail here at the contextual delimitation of the membership categories invoked by

particular such uses of you, something which has not been a focus of previous work. Such uses underpin the narrative

authority and credibility of the account in complex ways, as we describe.

In section 3.2 we turn to cases where you is used in the context of recounting personal experience, and forms a choice set

with I. These uses are most like OConnors involving type, and are not discussed by Kitagawa and Lehrer. This is the type of

usage illustrated in example (1) at the start of this article. We suggest that these uses too work to enhance the credibility of

the description, but in a more subtle and intriguing way.

L. Stirling, L. Manderson/ Journal of Pragmatics 43 (2011) 15811602 1585

3.1. Structural knowledge descriptions, membership entitlement, and you in Glendas discourse

There are numerous instances in Glendas discourse where generalized you occurs in the context of reference to general

truths about the world, to general processes involved in breast cancer treatment, or to cultural understandings and

expectations shared with the interviewer by virtue of her too being a woman and a mother, and of their common knowledge

and experience of a medical system (including familiarity with mammograms, although not of breast cancer). We can

understand such uses as invoking more or less general membership categories and the knowledge entitlements which go

with these. They correlate with what Goldsmith and Woisetschlaeger (1982) describe as structural knowledge descriptions

(see also Kitagawa and Lehrer, 1990). In attempting to account for differences in the distribution of the present tense and the

present progressive, Goldsmith and Woisetschlaeger pointed out that speakers can describe the world in one of two major

modes: in describing phenomenal knowledge, speakers describe what actually happens in the world in particular

circumstances, while in describing structural knowledge, speakers describe how the world is made such that things may

happen in it, from a perspective of general experience with what is the case in a kind of situation.

However, although these passages all occur in contexts of what Kitagawa and Lehrer (1990) would refer to as structural

knowledge descriptions, we show that there are differences in the way they function within the interactive context.

The references to general truths about the world tend to occur as evidentiary support when Glenda describes (and

analyses and theorizes) negative emotions that she experienced:

(2)

G: [and-] and-

(1.1)

and it was the grief:-

(0.8)

the grieving started (1.4) from then on,

from when I knew that I had to have a mastectomy,

and I-

(0.8)

I thought well,

(1.7)

you know theyre gonna take my breast off now and,

(1.5)

you know not-

not that I was big

but still you know,

your breast is your breast

and thats-

its the giver of life to your children

and,

(0.6)

R: mm=

G: =and just being disgured and not having a breast and-

(1.1)

but the grieving really started after I came out of surgery,

and the next day-

(0.8)

or-

yeah when I got out of an-

when the anaesthetic wore off,

(0.4)

Here Glenda is retrospectively describing and so theorizing her reactions at a time of heightened negative emotion,

explaining why the knowledge that she would have a mastectomy made her grieve, by arguing for the importance of the

breast to be lost. She begins with a reported private thought (cf. Barnes and Moss, 2007), displaying her realization of her

situation: I thought, well, you know, theyre going to take my breast off now. This is followed by a disclaimer it wasnt that she

L. Stirling, L. Manderson / Journal of Pragmatics 43 (2011) 15811602 1586

had started with big breasts: you knownot, not that I was big. The use of the discourse marker you knowhere ts Fox Tree and

Schrocks (2002) characterization, following Jucker and Smith (1998), of you know as indicating that the addressee is

expected to make an inference to supply missing information from the discourse. We are presumably to infer that some

might think that having big breasts (as for bigger instantiations of anything of value) would make them more worthy of

grieving. Glenda then lists three reasons for grieving the loss of a breast despite this, of which one is the functionality of the

breast in connection with nurturing children, and another, the more general aspect of being disgured. First, however, is

what she expresses as your breast is your breast. This might be paraphrased as referring to the inalienable sense of the breast

as a part of one/ones identity such that, regardless of howobjectively valued such a breast might be (i.e. even if not big), one

is entitled to mourn it. Generalized you is used here in an aphoristic, tautological way; this is a comment that would be true

for all and only women a rare example in our data of the moral or truism type of generalized you. Glenda thus underpins

her affective stance with reasoning which she constructs as universally shared, after disclaiming any specically personal

stake she might have had in the matter, e.g. through having particularly highly valued breasts.

In contrast, use of generalized you in reference to general processes involved in breast cancer treatment tend to be

interpolations withinthe sequential owof the narrative. Glenda interrupts her narrative, as she judges it necessary, to explain

to the interviewer facts about the process and procedures with which the latter may be unfamiliar. Here, you can be taken to

refer toanyone who undergoes treatment for breast cancer (includingme, andyouif youundergo treatment). Byinvoking this

membership category and the knowledge entitlement that goes with it, the speaker is displaying her authority as a member of

this group and thus enhancing the credibility of her both account and the evaluations within it. (Conversely, as Lindstro mand

Mondada(2009) amongst others havepointedout, provisionof anassessment is initself evidenceof claimingof knowledge, and

functions as a display of epistemic authority so use of generalized you and its evaluative context are mutually reinforcing

strategies in constructing an authoritative narrative.) Some examples are discussed below, in (3)(5).

(3)

G: I asked him to close the door,

(0.7)

and you know,

to lock it,

(1.0)

and I took- took off my shirt,

(0.7)

and my- the bra that I had on and,

and the

(0.6)

tsk-

the ( ) prosthesis [that they give you],

R: yeah

G: s$o I$ took that off,

(0.6)

Here, Glenda describes howshe forcedher husbandtotakehis rst lookat the site of her mastectomy, soas tocarefullycheckhis

real feelings about her. She describes in minute detail howshe undressed in front of him.

4

In this description of a concrete past

event presentedas pivotal intheir relationship, there is noplace for generalizedyou, except inthis one clause. The tsk indicates a

word search for the term used to name a particular artefact. Note the co-occurrence of generalized they with you here.

Similarly, the passage in (4) is part of a long and highly evaluated description of Glendas rather negative experience of

radiotherapy. Glenda is in the middle of describing what the health care professionals did and, more importantly, did not do

in order to provide her with information, prepare her for the treatment and ease her anxiety. In this extract, she interrupts

herself to explain a fact about the process of which she was denied knowledge, and which she (by virtue of explaining it) is

not presupposing the addressee knows. Again the use of they accompanying you lies somewhere on a cline of non-specicity.

(4)

G: [and-] and-

(0.5)

And she didnt even tell me that they could see me you know,

4

The highly detailed descriptions Glenda provides have also been identied as a feature of (potentially contestable) personal experience narrative which

functions to enhance narrative authenticity and hence speaker credibility, cf. Ochs and Capps (1997), Potter (1996), as we discuss further below.

L. Stirling, L. Manderson/ Journal of Pragmatics 43 (2011) 15811602 1587

through-

through-

(0.4)

cos they got this glass window?

(0.4)

where they watch you.

I didnt even know that you know.

(0.8)

and she left me.

she just left me in the room,

In (5), there is again an interpolated general explanation of what happens in the process of receiving radiotherapy.

(5)

G: [but] then-

(0.7)

after-

ah that was- that was terrible that day,

I was so angry with them,

(0.7)

you know I- I didnt want to go back the next day,

I was just so angry.

(0.6)

and I had to have six weeks straight of that every day.

(0.6)

R: [mm]

G: [you] go for six weeks-

is- is the-

(0.8)

R: mm=

G: =time that they give everybody,

you know six weeks-

(0.5)

or if have- if your cancers worse you might go on for a bit longer,

(0.8)

you can go on for however long your doctor wants you to but,

(1.5)

yeah,

ah,

(1.1)

o- b- it got- it got a little bit easier towards the end,

The short pause after I had to have six weeks straight of that every day before the interviewer responds may trigger further

explanation. Here you is the group of breast cancer patients who receive radiotherapy. The following boundary markers and

pauses but, (1.5) yeah, ah (1.1) mark off the interpolated explanation from the next part of the contribution as an aside.

There are many features of the passage in (5) which indicate that it is constructed so as to enhance the believability of

Glendas negative evaluation of her experience and the addressees acceptance of it (including markers of maximisation such

as straight), and the inclusion of a didactic aside of this type helps to establish her credentials and supports the general and

objective nature of her experience.

We now move to a different interactive function performed by structural knowledge description you. Where Glenda

invokes and seeks acknowledgement of shared cultural understandings with the interviewer, you is also used, in

accompaniment with you know and with other ways of soliciting agreement such as rising terminal intonation and pausing.

This is the case in (6):

L. Stirling, L. Manderson / Journal of Pragmatics 43 (2011) 15811602 1588

(6)

G: and thats why the nurses were cracking up at me because,

(0.4)

you know how they make,

they want you to feed the baby or-

(0.4)

R: mm

G: your ma-

your milk?

(0.6)

the breast and,

(0.8)

and they couldnt un-

they didnt understand why I was refusing not to feed the baby,

(0.9)

The interpolated general statement occurs in the context of explaining why the nurses were irritated with her after she gave

birth (thats why the nurses were cracking up at me because . . . they didnt understand why I was refusing not to feed the baby).

Glenda makes a general statement about the stance nurses take with newmothers, i.e. they encourage breastfeeding. This is

couched within a question about the interviewers shared knowledge and recognition of this general truth. (Here you knowis

not functioning as a discourse marker but as a full subject + main verb as part of what is being questioned.)

Again, example (7) is introduced by you knowas an explicit bid for the recognitionof what is presented as a shared general

truth about medical check-ups after giving birth, something any woman who had given birth in Glendas society, including

the anthropologist, would know. This successfully elicits acknowledgement of common ground from the interviewer, with

yeah.

(7)

G: Im glad,

(1.3)

cos Garry my ha-

Garry pushed me.

(1.1)

cos (0.4) th- when that six weeks came,

you know when you have to go back to antenatal,

for [your] check up,

R: [yeah]

The next passage, in (8), occurs in the context of a general question about how the breast cancer surgery affected what she

could do, and a follow-up question about howhard it was to look after the baby after the surgery. Glendas general response

was that it was hard to see others doing what she would have liked to do herself. Here, she has said she couldnt do much

because of the surgery, and she then explains why this was frustrating.

(8)

G: um,

and that was frustrating because,

(0.8)

you know when youve got babies you-

(0.5)

its mother and baby you know?

R: [yes]

G: [you] want to hold them close to your body and your chest and,

k-

(0.6)

L. Stirling, L. Manderson/ Journal of Pragmatics 43 (2011) 15811602 1589

kiss them and cuddle them and,

(0.4)

all those things I couldnt do with her?

R: mm,

mm,

G: so I missed that.

(0.6)

Here, the usage is in the context of explaining an intense and private emotion, by making reference to an attributed shared

emotion (what mothers want to do) there are things all mothers including you (want to) do and I missed being able to

do them. As with the previous two examples, this segment is introduced by you know, seeking recognition and

acknowledgement of this shared understanding from the interviewer, reinforced by a nal you know with rising intonation,

in the pattern: you know when/how [. . .you. . .], you know?.

Part of the same general sequence is example (9), in which the generalization is accompanied by the temporal adverb

usually.

(9)

but I couldnt hold her (as [well as-)]

R: [yeah]

G: the way I wanted to,

the way you usually hold-

(0.5)

[hold] your babies and,

R: [yeah]

(0.4)

In all the examples discussed in this section, Glenda uses generalized you to invoke a membership category to which she

belongs. The specic category at issue in each case is discernable in some cases fromdirect mention (its mother and baby you

know?), but more usually from the category-bound activities expressed by the predicates and other lexical items in the

clauses containing you, including nominals in construction with possessive generalized you (your babies, your cancer) (Sacks,

1972, 1992).

5

Furthermore, the context of participation in a sociological interview in a study targeting women who had had

breast cancer arguably makes always relevant the membership category of (breast) cancer patient/survivor. In examples

(3)(5), Glenda situates herself as a member of a group of people who have been diagnosed with and treated for breast

cancer which excludes the addressee. In contrast, in examples (6)(9), Glenda positions herself and the interviewer as

within an in-group of women mothers who share knowledge, understanding and experience of matters of childbirth and

mothering. As noted above, Glenda and the interviewer kneweach other prior to the interview, and so Glenda has knowledge

of the interviewers personal circumstances.

Although generalized you is used in each case, and in most examples ts the analytic prole of the situational insertion or

self-indexing use identied in the literature, there are clear interactional signals for these distinct positionings in Glendas

speech: most notably in the use in (6)(9) of questioning you know to introduce the passages at issue and in the explicit

seeking of acknowledgement from the addressee via question intonation. For these cases, where membership category is

shared between the interlocutors, there is an overtly signalled appeal for engagement and alignment of the addressee.

In both sets of examples, Glenda uses you to situate herself within a general category and recruit generalized knowledge

the knowledged entitlement of the category in question (Potter, 1996) hence successfully positioning herself as

authoritative with respect to this knowledge. Where she invokes a category shared by the interviewer, she additionally

solicits both the empathy and the epistemic agreement of the addressee. Via both these means she supports the credibility of

the account she is constructing of the experiences she has had.

In all of the examples considered in this section, generic or habitual present tense is used, and it is notable that in most

cases you could not be replaced by specic I, although it is often the case that it could be replaced by a rst person plural

pronoun, we or us. We return to this observation below.

3.2. You and I in Glendas narration of personal experience

We nowturn to cases where generalized you is used in the speakers description of her experiences of treatment for breast

cancer, and particularly in the context of description of heightened negative emotion, thus once again in evaluatively marked

5

The latter have been described as category-implicative descriptions in contrast to those involving direct reference to categories (cf. Stokoe, 2010).

L. Stirling, L. Manderson / Journal of Pragmatics 43 (2011) 15811602 1590

contexts. Inmany of the interviews in our data, fromwomenof different ages and educational backgrounds, generalized you is

used where participants are describing bodily experiences or their reactions to these, particularly negative experiences of pain

or bodily change. Such experiences form what have been called A-events (Labov and Fanshel, 1977) or Type 1 knowables

(Pomerantz, 1980; Sacks, 1975) that is, events for which the speaker has privileged knowledge. These contexts of use of

generalized you are ones where recurrent past or on-going personal experience of the speaker is described, often using past

tense and often accompanied by indicators of recurrence such as modal would or quantiers such as usually. Unlike the uses in

section 3.1, these uses can generally be replaced by I without changing the informational content of the description.

Before discussing these usages in the case study at issue, an example from another interview is given in (10), in the

response of one respondent when asked how chemotherapy affected her. This example clearly illustrates the use of

generalized you in conjunction with the past tense to describe recurrent prior personal experience of the speaker.

(10)

it used-

it made you ill and

(1.1)

um

(0.8)

but-

the morning that youd have to go down

(1.2)

you- you know you woke up feeling ill even$ tho$ugh$ you hadnt got there

It is difcult to see how generalized you could be replaced by any pronoun other than I/me or impersonal one here.

Substitution by a plural rst person pronoun in such a context would inappropriately leave the speaker open to

accountability for shared specic A-event experiences by others in the reference group.

A similar example from Glendas interview is (11). This example occurs in a general narrative by Glenda of how she rst

came to look at her mastectomy site after surgery. This passage grounds the described intensity of her emotional response as

she comes close to the moment of heightened intensity, when she actually looks at her chest, by elaborating on the reasons

for her fear and her reluctance to look at her body.

(11)

G: so she was right there,

she said Im just out here making your bed if you need me.

(1.5)

and I think I cried most of the time in that whole shower,

and I dont know whether th-

all the water was from the shower,

or from m$y tears (0.4) huh huh .hh

but it was just you know a-

(1.6)

yeah looking at your body,

(1.0)

R: mm

G: and thinking oh you know,

(0.8)

all the women around you,

(0.8)

who had two breasts you know,

(0.7)

had nice breasts,

youd be always-

Id be always looking you know.

(0.4)

L. Stirling, L. Manderson/ Journal of Pragmatics 43 (2011) 15811602 1591

as soon as I came ou- out- (0.4) out of hospital,

(0.7)

and youd go out-

cos I never went out for about three or four months,

I stayed indoors,

and I was scared?

(0.5)

R: [mm]

Introduced with but and you know, this passage involves switching between the rst person and generalized you. Glenda

presents a generalized sequence of thoughts which she attributes both to herself and generalized others, reecting the fear of

comparing ones own mastectomized body to that of other women. In a self-repair, she switches from the generalized,

modalized youd be always to Id be always looking. She then species the time at which she might begin this endless looking:

as soon as I came ou- out- (0.4) out of hospital. She then switches to a more general statement with the false start and youd go

out: this suggests the beginning of a description of a repeated series of events which she experienced, but is cut off as she

interrupts herself to say that in fact, she did not go out. In contexts such as these, the speaker is clearly negotiating choice

points between self-reference using I and self-including reference using you.

Examples (12) and (13) arise in the context of Glenda describing to the researcher where the pain she had experienced

post surgery was situated.

(12)

R: [where- wh]ere was the pain?

G: well it would come through the breast here in the middle and then,

go right at the back of your-

[up] the back.

R: [yeah]

G: and [its:-]

[so its] like where- where the scar [tissue] is?=

G: [yeah,] =yeah,

yeah,

and sorta right in the centre like where your nipple is,

and it goes right in.

(0.5)

sort of like phantom pain?

R: yes.

(0.6)

(13)

R: so when [you feel the pain] then you have the sensation of actually having a nipple and-

G: [the sensation of-]

well you can feel- feel something there and you [wanna] scratch it and,

R: [ yes ]

(0.6)

G: yeah you know you wanna-

(1.6)

just wanna fee$l it-

you know you think oh,

(0.5)

you$ kno$w huh [huh huh huh]

The interviewer asked Glenda Where was the pain? and example (12) was the response to this. At the end of this response

Glenda compares the pain she is describing as sort of like phantom pain? The researcher follows this up with a claricatory

L. Stirling, L. Manderson / Journal of Pragmatics 43 (2011) 15811602 1592

question: So when you feel this pain, do you actually feel like you still have a nipple? Example (13) is the response to this

claricatory question, and represents an attempt by Glenda to describe the bodily sensations she experiences. In both cases

Glenda is responding to specic, personal questions requiring specic and subjective answers, and is trying to describe a

specic bodily sensation to someone she knows has not experienced this, to talk the addressee into an understanding of

what she feels. Note that what she is describing is a recurrent experience in the past rather than a singular one (it would come

. . . and then go. . .). Glenda consistently avoids the use of the rst person pronoun here.

In some instances within these passages, she uses you in the context of describing locations on the body which are

presented as assumed to be shared amongst people (or perhaps women), so while the pain being described is subjective and

particular to her, she presents the location on the bodily canvass as if located on a generic human body. She uses the breast

instead of my breast; notice the interesting repair in (12) where she begins go right at the back of your- breaks off and then

completes the utterance with up the back (cf. Manderson and Stirling, 2007). Your nipple in sorta right in the centre like where

your nipple is, refers to anyones nipple.

A more ambiguous example is (14), when Glenda describes how she felt after having had mastectomy surgery.

(14)

G: when I had no visitors you know Id-

Id prob-

Id probably be crying most of the time when no visitors were in the room,

(1.0)

about,

you know,

(0.8)

breast cancer and not having a breast,

and even too scared to look down at this bandage.

I knew the bandage (0.6) was there,

you could feel it and everything

but I was,

(0.5)

just too frightened to look down?

R: mm

(1.0)

Again this is recollection of a time of heightened negative emotion. Glenda begins to describe her fear of looking at the

surgery site post surgery: and even too scared to look down at this bandage. This begins a lengthy description (not quoted here)

of a general and repeated set of events occurring over the days following the surgery, before she nally gets to the point

where she feels able to look at the mastectomy site. She elaborates on this initial remark in the immediately following

utterances, in a sequence involving shifts in the subject pronoun fromthe rst person I to generalized you and back again to I.

There is a sense in which the possibility of (physically) feeling the bandage is a more externalized and shareable experience

than the thoughts and emotions reported using I. Had she said here, I could feel it, this would perhaps have brought with it

the image of her touching it in actuality, and might have committed her to a claim that she had done so. The use of

generalized you allows for a shift away fromthe personal accountability whichsuch a claimwould entail. Note that the this of

this bandage brings both a sense of immediacy (in its proximal deixis) and also unfamiliarity (akin to non-specic uses of this

as in met this guy at the bus stop) there is certainly no ownership here as there would have been with my bandage or even an

introductory the bandage (Manderson and Stirling, 2007). Finally the high rising tone on too frightened to look down? seeks

acknowledgement from the hearer, which is forthcoming (mm).

In contrast, in example (15) generalized you is used for reports of emotion (how youre feeling) as well as physical

sensation (when youre lying), as Glenda makes a general evaluative claimabout her hospital experiences couched in terms of

the generic category of nurses on the one hand and patients on the other. She describes her perception of the nurses

general inability to talk to or console patients, and gives an account of what kinds of upsetting experiences they might

console patients about, or what patients might feel in need of being consoled about. After making a general statement about

the way any patient might feel in a hospital situation (or perhaps in that kind of hospital situation), where generalized you is

used, Glenda moves to a specic evidentiary personal instance (cos) with the rst person I.

(15)

G: and the nurses you know,

they were all-

they just didnt know

L. Stirling, L. Manderson/ Journal of Pragmatics 43 (2011) 15811602 1593

(0.6)

how to-

(1.5)

how to console a- (0.5) patients either,

R: mm,

G: or how to talk to the patients,

you know about,

(1.0)

about how youre feeling right there and then,

when youre lying in that (1.1) sterile hospital=

R: =mm=

G: =atmosphere and,

(0.6)

everyone else sick around you,

cos I was in with all the (0.6) older patients,

all old

(0.5)

R: mm=

G: =women you know,

and that made it even worse?

(0.6)

In (16), part of the long passage mentioned earlier describing howthe nurses tried to get her to look at the mastectomy site,

Glenda again reects back on remembered heightened negative emotion. This extract begins with a report of what she would

habitually tell the nurses: I dont want to. Not today. The next utterance gives the reason for this statement: using the rst

person pronoun I, as she does elsewhere in speaking of her own remembered fear, she says she was scared. However, she

couches the content of her fear what she was afraid of using generalized you (scared of um, (1.7) losing your breast ..), and

by doing so gives it potentially more general applicability. In this way the propositional content of an emotion state is framed

as a general truth about the world or as a shared reaction to circumstance. Glenda then restates her state of mind at the time:

she didnt want to look at it, because . . . leaving the addressee to ll in the already specied reason, with you know perhaps

here again signalling the need for addressee inference. This is the end of this sequence, with the following utterance marking

a move to a new topic.

(16)

G: I dont want to.

not today.

(0.7)

I was scared.

R: mm

G: scared of um,

(1.7)

losing your breast and-

and- and grieving for-

[for] that loss,

R: [mm]

G: um,

(1.3)

and I didnt want to look at it you know.

just cos-

(1.6)

you know,

(0.7)

L. Stirling, L. Manderson / Journal of Pragmatics 43 (2011) 15811602 1594

The next example in this section also involves talk about emotion, with Glenda switching between I and you as she answers a

question about her own emotional response with respect to sex and love-making. She has been describing her husbands

attitude as hesitant, which she attributes to him being considerate. But this made her worry. The you passage in (17)

presents the content of her worry by describing an imagined scenario plausibly a real recurrent worry she has had which

is later denied validity (but it wasnt). Note in particular the correction fromyou to me in the segment he doesnt want to make

love to you- to me . . . and the subsequent consistent use of me in these segments of reported thought, which display the

inappropriateness of generalized you in this context. It is perhaps the case that this decision by the speaker relates to the fact

that what is being reported here is direct rather than indirect reported private thought, as indicated by the presence of the

exclamation oh at the start. Her corrected initial attribution of this thought process to a more generalised centre of

perspectivisation is however consistent with the other examples we have seen, in that once again it invokes the support of

more general shared experience in presenting her position here.

(17)

G: hes very considerate and loving and hes sort of,

(1.0)

um,

(0.7)

didnt want to do anything=

R: =yes=

G: =wrong either to upset me and things like that.

(0.8)

and then you know um,

(0.8)

then you think oh!

(0.7)

oh he doesnt want to make love to you- to me or-=

R: =yeah=

G: =you know,

(0.4)

then you th- start thinking all these other ideas,

like you know he doesnt really want to make love to me because Ive got

one breast and=

R: =yes

(0.4)

G: but it wasnt,

Garry was waiting for me,

In conclusion, let us consider a nal passage fromthe interviewwhich occurs after the researcher has asked Glenda if she had

ever got lymphedema, and Glenda rst provides a straightforward, unqualied negative answer. But then she continues,

qualifying this statement somewhat witha long, educative passage explaining howshe, like anyone who has hadbreast cancer,

has to be careful in a range of different ways so as to avoid getting lymphedema, giving the rules for lymphedema avoidance.

6

(18)

G: but still you got-

I still gotta be very careful in-

(0.8)

in um,

(1.1)

how I-

how you-

how I do things around the house,

6

Lymphedema is a disorder which occurs when lymphatic uid builds up in soft tissues of the body, for example in the armafter under armlymph nodes

have been removed as part of treatment for breast cancer.

L. Stirling, L. Manderson/ Journal of Pragmatics 43 (2011) 15811602 1595

gardens and,

(1.0)

in the kitchen you know,

youve still got to be very careful in how you-

cut you know,

you dont cut yourself and all those sorts of things and,

(1.3)

R: because why?

G: you can never-

you can never be-

(0.9)

you can never not be careful with your body anymore [once] you have cancer,

R: [ mm]

(0.4)

mm,

(1.4)

G: cos if you cut yourself you get bacteria in your-=

R: =mm

G: well this is what-

ah you know through-

with the breast cancer if you cut your hands on that side,

(0.5)

R: mm,

G: the bacteria gets in and then it- it start- affects the lymphedemia stuff=

R: =right=

G: =your lymph nodes and that,

R: yeah

G: and can cause lymphedema and all [those] sorts of thing,

R: [ mm ]

mm,

G: and you know,

other things can go wrong,

(1.2)

so you have to be very careful about,

(0.6)

when youre doing the gardening or being pricked with (0.7) rose bush or=

=whatever,

you know,

youre doing in the- in the garden or wherever you are really,

[and] youre very conscious of everything.

While most uses of you in this passage are examples of structural knowledge description you, the kind discussed in section

3.1, involving membership of a category of breast cancer survivors, Glenda nevertheless vacillates between I and you in

framing this information: after a shaky, dysuent start with a number of false starts and repairs involving the choice between

I and you, Glenda settles into a generalized pattern. During this segment Glenda thus shifts fromthe individual to the general,

once again positioning herself as authoritative about breast cancer and its treatment by virtue of the knowledge entitlement

which comes with her membership of this category.

4. Discussion

Speakers typically describe and narrate their own past experience within interactive contexts. In the course of any one

interaction, as well as across multiple distinct interactions over time, they will ne-tune the reconstruction of the events

L. Stirling, L. Manderson / Journal of Pragmatics 43 (2011) 15811602 1596

that they are relating to suit the sequential position of the utterance in the discourse, their evaluation of the interlocutors

state of knowledge, interactive goals and attitude, and the stance they themselves wish to take on the situations or

situation types under discussion. Key life-changing events may be related many times in the course of an individuals life

span, and we knowthat the formof narration changes fromone episode of narration to another (Bauman, 1986; Bamberg,

2008).

One force at work in narration of personal experience is the need to display the validity and credibility of what is being

said and the speakers authority for saying it. Potter (1996) shows that amongst the most important devices speakers use in

constructing credible accounts are on the one hand the provision of vivid detail, to sustain the category entitlement of

witness, and on the other the use of general formulations, to construct the account as neutral and consensual.

Another potential pressure on the construction of personal narratives is the need to tie the content being presented to the

interlocutors knowledge and experience and perhaps to recruit their engagement, assent or empathy. As the latter may also

assist in achieving the acceptance of the narrative as credible, speakers may design their accounts so as recruit audience

empathy and alignment.

Both related goals of credibility and of audience alignment are served by strategic appeal to generalized knowledge of the

way things are, by invoking membership categories of one kind or another. A complex map of patterns of shifts within the

discourse between talk of specic, past personal experience, and more general social and cultural knowledge and situation

types can be the result. While various linguistic cues may place a particular utterance at the more specic or more generic

end of the spectrum, it is possible for an utterance to invoke at one and the same time both a specic set of events and more

generalized knowledge of events of this type: not only is there a cline of specicity, and sometimes indeterminacy as to

where on the cline an utterance lies, but there is also the possibility of a functional layering of (general and particular)

meanings.

Generalized you allows speakers to talk in rich detail of events which they have experienced, taking advantage of the

appeal to authentic witnessing which this allows, while at the same time assigning accountability for their descriptions to a

broader social group, bringing with it the authority that category-based knowledge entitlement confers. Thus Glenda tells us

about the ugly picture on the wall of the radiotherapy treatment room and the imaginings this inspires while at the same

time evoking, and invoking, the experience of countless other women with breast cancer who we infer to have been treated

in the same room.

In the examples considered in section 3, taken primarily from one extended interaction, we have tried to place the use of

generalized you within this shifting pattern of specicity and generality. As we indicated in section 2, it has been observed in

previous research that generalized uses of you co-occur with other markers of genericity such as the use of the generic

present tense, modal auxiliaries or adverbs. Thus interpretation of a use of you as generalized may in part be supported by

these other markers, indicating that the event being described is to be taken generically. On the other hand, the presence of

you within an utterance may act as one of the indicators of genericity.

Fromthe perspective of the literature reviewed in section 2, we found two distinct types of usage in our data, co-occurring

with distinct ranges of other linguistic markers: the structural knowledge description type discussed in section 3.1 was

found with present tense, while the personal experience type of use discussed in section 3.2 tended to co-occur with

(modalized) past tense forms of the verb due to the fact that specic, if recurrent, experiences of the speaker were being

described.

The personal experience cases explored in section 3.2 have been of particular interest in our discussion, as while they

conformto Bolingers observation that, though past tense, they refer to recurrent rather than single events, nevertheless they

are cases where the events being described are overwhelmingly particular to the speaker and not the addressee and are

grounded in specic, if repeated, personal experience, often described in vivid detail. Because of this, one might expect the

rst person pronoun I/me to appear, yet the generalized you is chosen. However in many of these cases there is a pattern of

shifting choices of pronoun reference between you and I, and instances of repair involving such shifts suggest that for the

speaker, part of the construction of the narration involves subtle choices between particular and generalized frames and/or

reference using the rst person or you.

While this framing helps to understand the particular interpretation you may have in specic instances in the discourse,

the question remains: what kind of functional motivations may underlie the choice between you and rst person self-

reference, as in the examples of personal experience you discussed in section 3.2?

We have suggested in the course of our discussion of these examples that the key to understanding choice of generalized

you in our data lies in its invocation of membership categories of greater or lesser specicity, and the knowledge entitlements

which these bring with them. The women in our study are positioned as witnesses by virtue of their inclusion in the study.

They are credible narrators by virtue of their status as rst hand experiencers of the events which they are reporting and they

underline this status and capitalise on it in the rich detail they provide in their descriptions of events, which add to the force

of their accounts. The membership category of witness in itself is a powerful one, although as both Potter (1996) and Ochs

and Capps (1997) have pointed out, it brings with it certain disadvantages: vulnerability to accusations of personal interest,

as well as to potential contesting of the account.

In contrast, invocation of more general membership categories, such as that of breast cancer survivor, or mother, or

woman, allow speakers to frame their claims as ones which would be corroborated by members of these categories more

generally. We have seen how Glenda invokes membership categories specic to her illness experience in ways which

underpin her authority. She invokes more general categories, shared with the interlocutor, at points in her narrative where

L. Stirling, L. Manderson/ Journal of Pragmatics 43 (2011) 15811602 1597

she is constructing a negative evaluation of the health care system she has encountered and in these contexts, her appeal to

the shared experience of being a woman or being a mother explicitly acceded to by the interlocutor makes her account

difcult to challenge.

We sawin section 2 that many attributions of intention to speakers using generalized you are agged in the literature, for

instance OConnors description of her third category as involving. Broad statements of functionality tend to be made in

discourse analytic research with a more general purview(cf. Fairclough, 1989:128). Our claimhere is that the key property of

generalized you is that it invokes some contextually determined membership category, and that this property underpins a

range of more specic and potentially coincident functions, which in our data all work to enhance the credibility and

authenticity of the narrative being produced. We elaborate on these more specic interactional functions in the remainder of

this section, and suggest that all of these can be seen as at work, in varying degrees and combinations, in the examples we

have considered above.

7

4.1. You and the addressee: inclusion, empathy and co-option

The most notable element in the use of generalized you, which most clearly distinguishes it fromgeneralized uses of other

personal pronouns, is the implication of the addressee in the reference group by virtue of the primary use of the formto refer

to the addressee(s). Why would a speaker make a point of including the addressee in a reference group invoked in the context

of making a general statement about the world, something not (necessarily) specic to the addressees personal history or

circumstances?

Numerous authors have considered this property of generalized you and, depending on the kind of data which they

have considered, have viewed it as involving benign or less benign intentions of the speaker. For example, Kitagawa

and Lehrer (1990:744, 752) state: In both impersonal and vague uses of you the interlocutor assumes the status

of representative in some sense of the intended referent either as representing potentially all members in the

impersonal cases, or a subgroup and A sense of informal camaraderie is often present with the use of impersonal you

precisely because the speaker assigns a major actor role to the addressee. In so doing, s/he is letting the hearer into the

speakers world view, implying that the hearer also shares the same perspective. This can be considered as an act of

camaraderie.

In contrast, OConnor (1994) reports on the potentially more sinister face of this property of generalized you. She

describes how prison inmates use you to co-opt empathy and engage the addressee as a possibly unwilling neophyte, in a

teaching situation in which the information being conveyed may be socially stigmatized, illegal or morally questionable.

Freadman (1999), too, in her essay on the Ryan hanging, the last hanging in Victoria, describes the use of you to include the

addressee, and writes of its urgent inclusiveness which demands empathy, even identication (p. 37). Calling this the

interpellatory you of witnessing, she notes that witnessing brings with it a positioning and imposition of ethical obligation

upon a listener, citing in support Dori Laubs work on accounts of the holocaust (Felman and Laub, 1992). For both OConnor

and Freadman, the effect on the listener is unavoidable incorporation, with potentially negative results (see also DelConte,

2003).

8

Freadman makes the stronger claim, at least in the passages she is considering, that the pronoun is used in each case at a

point of ineffable solitude (p. 37). The condition of the isolated I is intolerable, she writes, hence you is used to avoid this

isolation. Glendas description of radiotherapy, in our quotation at the beginning of this article, has very much the avour of

a point of ineffable solitude.

As we have seen in the examples discussed, while generalized you always has the theoretical capability of including the

addressee in the invoked reference group, which gives it its involving character, this is actively utilised by the speaker in

cases where the reference group is a membership category to which both participants belong in our data, categories such as

mother or woman.

4.2. You and the speaker: objectivity distancing or isolation?

Although many authors have suggested that generalized you always includes the speaker, as inevitably part of

reference to people in general, from the perspective of the speaker, the use of generalized you can be seen as potentially

excluding of self. In fact we have argued that it is more common for generalized you to invoke a contextually determined

category more specic than people in general. It is surely possible for this category to be one which the speaker does not

in fact belong to, however such cases are not exemplied in our data: as we have seen in section 3, Glenda always speaks

from a position of inclusion in the more general categories she invokes. Nevertheless, use of you does function as an

externalising or distancing device as it diffuses the speakers personal accountability with respect to the events and

evaluations represented. This becomes particularly noteworthy when the kinds of events being described are ones which

the speaker has privileged access to and may describe in signicant detail: and this kind of usage is far from rare, as we

7

Stokoe (2010) also illustrates a type of systematic sequential analysis that can be done with membership categories (p. 59), looking at shifts between

the general and the specic, but does not focus on pronominal reference.

8

Interestingly, both Wear (1993) and Langellier (2001) quote confronting statements using you in the titles of their papers on the experience of breast

cancer. Langellier (p. 152153) reports an account of radiotherapy very similar to what we found in our data in its use of generalized you.

L. Stirling, L. Manderson / Journal of Pragmatics 43 (2011) 15811602 1598

have seen. We talk about examples of this kind from our data in section 3, and both OConnor and Freadman refer to

similar examples.

OConnor describes numerous instances where prisoners use generalized you in the context of describing events and

event types which have very limited generality in the speech community, but which the teller has experiential knowledge of,

such as acts of stabbing murders. She suggests that use of the pronoun you may allow the speaker to distance themselves

from the events being described it locates some of the memory at a safer remove (59).

We concur that the use of generalized you has an externalising or distancing effect, and psychological distancing

of the kind postulated by OConnor would be plausible in our data given the heightened emotion and evaluation in

the accounts, although it is not straightforward to nd independent evidence for this in the interaction. We would

also note, however, that much earlier work has shown that externalising creates a sense of objectivity which

enhances the credibility of the account, and this explanation coheres with the general picture we present here of