Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Loveman Is Race Essential

Enviado por

Javier Fernando GalindoDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Loveman Is Race Essential

Enviado por

Javier Fernando GalindoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Is "Race" Essential? Author(s): Mara Loveman Source: American Sociological Review, Vol. 64, No. 6 (Dec., 1999), pp.

891-898 Published by: American Sociological Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2657409 Accessed: 12/11/2008 10:12

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=asa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Sociological Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Sociological Review.

http://www.jstor.org

COMMENT AND REPLY

three critical pitfalls: (1) confounding categories with groups, (2) reifying "race,"and IS "RACE" ESSENTIAL? (3) maintaining the unwarranted analytical distinction between "race" and "ethnicity." Mara Loveman These three flaws undermine the usefulness Universityof California, Los Angeles of his "racialized social system" framework for improving our understanding of historiIn his recent article in the American Socio- cal and contemporary meanings of "race" logical Review, Eduardo Bonilla-Silva and consequences of "racism." (1997, henceforward EBS) argued that "the To avoid these pitfalls and to understand central problem of the various approaches to more fully how "race"shapes social relations the study of racial phenomena is their lack and becomes embedded in institutions, of a structuraltheory of racism" (p. 465). He "race"should be abandoned as a category of identified several limitations of existing ap- analysis. This would increase analytical leproaches, including the tendency to treat rac- verage for the study of "race" as a category ism too narrowly: as psychological and irra- of practice.2 To improve our understanding tional (as opposed to systemic and rational); of "racial" phenomena we do not need a as a "free-floating" ideology (as opposed to "structuraltheory of racism" but rather an structurallygrounded); as a historical legacy analytical framework that focuses attention (as opposed to a contemporary structure);as on processes of boundary construction, static and epiphenomenal (as opposed to maintenance, and decline-a comparative changing and autonomous); as evident only sociology of group-making-built on the in overt behavior (as opposed to both overt Weberianconcept of social closure. and covert behavior). EBS believes that a structuraltheory of racism based on the conCATEGORIES cept of "racialized social systems" can over- CONFOUNDING GROUPS WITH come these shortcomings (p. 469). Although I agree completely with EBS The first major pitfall of the framework EBS about the importance of improving our un- proposes is that it treats as natural and autoderstanding of the causes, mechanisms, and matic the move from the imposition of racial consequences of "racial phenomena,"l I ar- categories to the existence of concrete gue that his "structuraltheory of racism" is groups that embody those categories. decisively not the best analytical framework "Racialized societies" are defined as "socifor accomplishing this goal. The utility of his eties in which economic, political, social, theoretical framework is undermined by and ideological levels are partially structured by the placement of actors in racial catego* or races" (p. 469). "Race" thus seems to ries Direct correspondence to Mara Loveman, as a synonym for "racialcategories." be used UCLA Department of Sociology, 2201 Hershey EBS, however, does not maintain this anaHall, Box 951551, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1551 (mloveman@ucla.edu). For their insightful com- lytical usage of "race."In his next paragraph, ments and helpful suggestions, I thank Rogers he argues: "In all racialized social systems Brubaker, Rachel Cohen, Jon Fox, Peter the placement of some people in racial catStamatov, Lofc Wacquant, Roger Waldinger, and egories involves some form of hierarchy that ASR's anonymous reviewers. I gratefully ac- produces definite social relations between

COMMENTON BONILLA-SILVA,ASR, JUNE 1997

knowledge support received from the Mellon Foundation's Program in Latin American Sociology. 1It should be clear from this that I oppose the claim made by some theorists that "race" is no longer relevant and should not be a focus of sociological analysis.

Refering to "race" as a category of practice does not imply in any way that "race" is merely epiphenomenal, just as recognizing that "race"is a social construction does not imply in any way that it is not real in its consequences.

892

AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

Although EBS is correct in arguing that the socially constructednatureof "race"does not make it less than "real,"his framework does not recognize the variability and contingency of the "real" consequences of "race" as, in Bourdieu's (1990) terminology, a principle of vision and division of the social world. On the one hand, EBS writes of "the classification of a people in racial terms" (p. 471) as if a bounded, clearly demarcatedgroup existed objectively, "out there,"before the process of categorization. Categories sometimes may be superimposed on already recognized and operative social boundaries, and perhaps may change their meaning without altering their content. But they also may create new divisions, making possible the emergence of "peoples"who had not previously recognized themselves, nor had been recognized by others, as such (Hacking 1986; Horowitz 1985; Petersen 1987). On the other hand, the extent to which "race"becomes a basis of group association and identity as a consequence of imposed racial categorization is historically variable. Again, this point raises the question of the relationship between imposed categories, the identity of the categorized, and experienced groupness (Jenkins 1994). EBS's analytical framework may permit such contingency during the initial process of racialization; within a "racialized social system," however, it provides no leverage for exploring the variable relationship between categories, identities, and the "groupness" experienced because the analytical distinction between categories and groups is not maintained. EBS points out that "races" are socially 3 This observation is not new. As Weber and therefore that "the meaning constructed, ([1922] 1968) explained, and the position assigned to races in the raIt is by no means true that the existence of comcial structureare always contested" (p. 472). mon qualities, a common situation, or common modes of behaviorimply the existence of a com- In this formulation, however, the groupness munal social relationship.Thus, for instance, the of the actors in a "racialized social system" is possession of a commonbiological inheritanceby assumed. By definition, "races"exist as colvirtue of which persons are classified as belong- lective actors in a racialized social system ing to the same 'race,' naturallyimplies no sort (even if, at some moments, nonracial-class of communalrelationshipbetween them. (P. 42) or gender-interests are the primaryfocus of Generations of Marxist scholars also have their attention). Contention occurs over the grappled with this issue in efforts to theorize the meaning (positive/negative stereotypes) and relationship between "class-in-itself' and "classthe position (subordinate/superordinate) of for-itself." different "races," not over the existence or 4 In some cases, analysis of processes of catof racial boundaries themselves operation egorization may reveal more about the categorizers than the categorized (Jenkins 1994:207; (Barth 1969; Roediger 1991). "Racial" politics entail struggles over boundaries;this fact Stuchlik 1979). the races" (p. 469). Clearly, "racial categories" and "races"have ceased to be synonymous-"racial categories" have produced "races"in an entirely different sense. EBS thus uses the term "race"analytically to mean both "racial category" (p. 469) and "racialized social group" (p. 471). The problem is not simply that the conceptual framework employs this dual analytical understanding of "race,"but that it hinges upon the analytical conflation of "race" as category with "race" as social group. This conflation appearswarranted,given the assumption that racial categories both create and reflect the experienced reality. According to EBS, categorization into "races"--or "racialization"-engenders "new forms of human association with definite status differences." After racial labels are "attached" to a "people," "race becomes a real category of group association and identity" (pp. 471-72). Although this may be the case in particular contexts in particular historical periods, it is not axiomatic that membership in a category will correspond directly to experienced group boundaries or social identities.3 The extent to which categories and groups do correspond,and the conditions under which they do so, should be recognized as important theoretical questions that are subject to empirical research (Jenkins 1994).4 By adopting a conceptual framework that fails to maintain the analytical distinction between category and group, classification and identity, such potentially rewarding avenues of research and theorization are foreclosed.

COMMENT AND REPLY

893

The limitations of this reified conceptualization of "race" become readily apparent when EBS addresses the problem of "race" in Latin America. He suggests that in countries such as Brazil, Cuba, and Mexico, "race has declined in significance," but that these countries "still have a racial problem insofar REIFYING "RACE" as the racial groups have different life After conflating racial categories with racial chances" (p. 471). "Race" is treated as a groups, it is only another small step to ob- "thing" in this formulation; in addition, it is jectifying "races" as races. In racialized so- treated as the same "thing" in each of these cial systems-societies that are partially places as in the United States. It is conceptustructuredby the placement of actors in ra- alized as varying in salience or importance, cial categories-races exist. Indeed, this is so but not in meaning. EBS himself criticizes by definition in the conceptual language used other approaches for failing to recognize the (racial categories = racialized social groups change over time in the meaning of "race"in = races). The analytical frameworkproposed the United States. Yet his own analytical by EBS thus depends on the reification of frameworkforecloses the possibility of com"race";races are real social groups and col- parative analysis of the varied meanings of lective actors. "race" across time and place, and of the reEBS seems to recognize this problematic sulting variability in its consequences for soaspect of his conceptual framework, which cial organization and domination. accounts for his comment in a footnote that As one example, reification of "race" ob''races (as classes) are not an 'empirical scures the problematic nature of the claim thing'; they denote racialized social relations that in Brazil the "racial groups have differor racial practices at all levels" (p. 472, from ent life chances" and hence different objecPoulantzas 1982:67). This disclaimer, how- tive "racial interests." This assumption ever, is in profound tension with the clashes with the experience of political acconceptualization of races as social groups tivists of the movimento negro, whose first with particular"life chances" and as collec- and most challenging task in mobilizing tive actors with "objective racial interests" people around "race" in Brazil has been to (p. 470). As EBS explains, "Insofar as the make people think in "racial" terms so that races receive different social rewards at all they might "see" why and how "race" matlevels, they develop dissimilar objective in- ters in their lives. Central to this goal have terests, which can be detected in their been efforts to encourage Brazilians to catstruggles to either transform or maintain a egorize themselves according to a dichotomous understandingof "race"-based on the particularracial order"(p. 470). Preempting the criticism that "races" U.S. "model"-that does not automatically themselves may be stratified by class and or obviously resonate with their own experigender, EBS argues, "The fact that not all ence and understanding of "race" as much members of the superordinate race receive more flexible and subject to context the same level of rewards and (conversely) (Hanchard 1994; Harris 1970; Nobles 1995; that not all members of the subordinaterace Wagley 1965). or races are at the bottom of the social order The assumption that "races" exist as does not negate the fact that races, as social bounded, socially determined groups is also groups, are in either a superordinateor a sub- problematic in the United States, however ordinateposition in a social system" (p. 470). warrantedit may seem for those accustomed Yet this attempt to defend his framework ac- to viewing "race" through the prism of tually reveals a more profound analytical United States experience. The disjuncture shortcoming: Although his framework per- between discrete, mutually exclusive racial mits variability in individual life chances categories and the potential ambiguity and within a "race," the boundaries-and the blurriness of "racial"boundaries in people's boundedness-of the "races"themselves are experience in the United States has come to assumed to be unproblematic. the fore in recent political struggles over the

is not broughtinto focus by an analytical lens that treats the existence of bounded, racialized collective actors-races-as the logical (natural?) outcome, as well as the defining characteristic,of "racialized social systems."

894

AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

has a primarily sociocultural foundation, and ethnic groups have exhibited tremendous malleability in terms of who belongs," while "racial ascriptions (initially) were imposed externally to justify the collective exploitation of a people and are maintained to preserve status differences" (p. 469). This rationalization suffers from the same defect as other attempts to distinguish analytically between "race" and "ethnicity" by reference to the empirical differences between them: Differences that are peculiar to the United States at particulartimes in its history are taken as the bases for conceptual generalization. The position that "race"and "ethnicity" are analytically distinct thus reflects the ingrained North American bias in the sociology of "race."Commonsense understandings of these categories as they exist in the United States are elevated to the status of social scientific concepts. The particular (and particularly arbitrary) operation of "race" versus "ethnicity"in the United States is thus treated as the norm, from which other modalities of categorization are considered to be deviations (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1999).6 EBS's theory relies on commonsense understandings of "race" and on circular definitions to justify its exclusive application to "racialized"social systems. The key concept of his analytical framework, "racialized soDISTINGUISHING ANALYTICALLY cial systems," is defined only in reference to BETWEEN "RACE" AND "ETHNICITY" the concept of "race"itself. Thus, "racialized The third analytical pitfall is the unfounded social systems are societies that allocate difinsistence on distinguishing analytically be- ferential economic, political, social, and tween "race"and "ethnicity,"and the attempt even psychological rewards to groups along to theorize the formerin intellectual isolation racial lines; lines that are socially confrom the latter.5 Although EBS insists that structed" (p. 474). But what are "racial his conceptual framework is applicable only lines"? How do they differ analytically from to "racialized social systems," he does not ethnic lines? The definitions offered are cirmake clear the analytical bases for distin- cular: Racial lines are present in racialized guishing "racialized" systems from "ethni- societies buttressed by racial ideology, in cized" systems. The justification offered for distinguishing 6 As Wacquant (1997) suggests, analytically between race and ethnicity is [T]he sociology of "race"all over the world is based on an empirical understandingof their dominated by U.S. scholarship. And since U.S. differences. According to EBS, "ethnicity scholarshipitself is suffused with U.S. folk coninclusion of a "mixed race" category in the next census. Once it is recognized that the boundaries between "races," and hence the existence of "races," cannot be deduced from the existence or imposition of "racial" categories, whether in Brazil or in the United States, the attribution of objective "racial interests" to the putative "races" becomes all but meaningless. Even if "racial"interests are defined in a nontautological manner, the notion that such interests are objective and can be identified from the struggles of "races"over their position in the racial hierarchy falls apart once the existence of "races"per se is made problematic. The assumption that "races" exist as collective actors cannot be the starting point if the goal is to understandwhat "race"means, and how, and with what consequences, it operates as a principle of vision and division of the social world across time and place. The analyst should focus on the groupness itself, and hence on the processes of boundarymaking and unmaking in relation to systems of categorization and processes of social inclusion and closure. This requires an analytical framework that is not built on a reified conceptualization of "race."

5 Theorists have offered several reasons for distinguishing analytically between "race" and "ethnicity";some are more compelling than others. Space constraints prevent a full consideration of this issue here. My comments explicitly address only the type of rationale EBS offers.

ceptions of "race,"the peculiar schema of racial division developedby one countryduringa small segmentof its shorthistory, a schemaunusualfor rigidity and social conits degree of arbitrariness, sequentiality,has been virtuallyuniversalizedas the templatethroughwhich analyses of "race"in all countriesand epochs are to be conducted.(P. 223)

COMMENT AND REPLY

895

which racial contestation "reveals the different objective interests of the races in a racialized system" (p. 474). EBS is not alone among scholars of "race" in resorting to tautology to defend the unique analytical status of "race." In their "racial formation" perspective, Omi and Winant (1994) also rely on circular definitions and essentialist reasoning to defend the independent ontological status of "race."They define "racial formation" as the "sociohistorical process by which racial categories are created, inhabited, transformed,and destroyed" (p. 55), but they never define "racial categories" without referencing "race." Their efforts to argue for a distinction between "race"and "ethnicity"is based on a particular reading of U.S. history ratherthan on any analytical foundation. Omi and Winant (1994) argue that the "ethnicityparadigm,"developed in reference to the experience of "European [white] immigrants," cannot comprehend the experience of "racial groups." They rule out the possibility that European immigrants could be "racialized"because they were phenotypically white. This position is not only historically inaccurate, as demonstratedin work on the racialization of Irish and Italian immigrants (Ignatiev 1995; Roediger 1991), but it also contradicts their own contention that "race has no fixed meaning, but is constructed and transformed sociohistorically" (Omi and Winant 1994:7 1). Thus the great difficulty of providing analytic justification for isolating theories of "race" from theories of "ethnicity" is revealed in "race"theorists' recent, prominent attempts to prove otherwise. Historically specific differences between the meaning and operation of "race" and "ethnicity" as systems of categorization in practice in one society cannot be the foundation for a general and generalizable analytical distinction between "race"and "ethnicity."Asserting the unique ontological status of "race" may actually undermine attempts to improve understanding of the operation and consequences of "race,""racism,"and "racial domination" in different times and places. The arbitrary theoretical isolation of "race" from "ethnicity" discourages the comparative research needed to discover what, if anything, is unique about the operation or consequences

of "race" as an essentializing practical category, as opposed to other categorization schemes that naturalize social differences between human beings. RECONSIDERING "RACE" According to Wacquant(1997), "from its inception, the collective fiction labeled 'race'

... has always mixed science with common

sense and traded on the complicity between them" (p. 223). This complicity is intrinsic to the category "race"; it undermines attempts to study "race"as a practical category by using "race" as an analytical category.7 This is quite clear in the frameworkproposed by EBS, and in the framework of Omi and Winant (1994) as well. Neither "racialized social system" nor "racial formation" is defined without reference to "race"; therefore a commonsense understanding of "race" is requiredto do the work of determining when a social system is racialized. Without a clear analytical definition, the realm of "cases" of racialization is presented and understood as the set of contexts in which the language of "race" is operative and has social consequences for particular groups of people. The presence of "race talk," or racial terminology, and beliefs and institutionalized practices informed by that terminology, indicates that "racialized social system" or "racial formation" is the appropriate conceptual framework. Relevant cases are identified by the existence of "racial groups" (EBS, pp. 476-77; Omi and Winant 1994); conversely, identification of "racial groups" can be based only on commonsense understandings of "race" because they are never defined analytically without referencing "race." Case selection thus is governed by folk understandingsof "race"rather than by analytical criteria such as distinctive bases and processes of social closure. This analytical pitfall can be avoided most successfully by abandoning "race" as a category of analysis in order to gain analytical

7 Because of the extent of "continual barter between folk and analytical notions. .. of 'race,"' we need an analytical language that helps us avoid the "uncontrolled conflation of social and sociological understandingsof 'race"' (Wacquant 1997:222).

896

AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

leverage to study "race" as a category of practice.8 By adopting an analytical framework that focuses on essentializing schemas of categorization and processes of groupmaking generally, one can explore empirically whether and to what extent a particular essentializing vocabulary is related to particular forms of social closure and with what consequences. Thus it becomes an empirical question whether, and to what extent, systems of classification, systemic stratification, and social injustices buttressed by ideas about "race" are historically distinct from those informed by a discourse of "ethnicity" or "nationality." Empiricalresearch on a specific historical period in a particularnationstate could uncover important differences in the meaning and consequences of "race"and "ethnicity"; consideration of such findings within a comparative historical perspective could clarify the extent of historical contingency involved. Such an approach is likely to discredit claims that "race"is unique in its operation as an essentializing signifier (Guillaumin 1995:30; Omi and Winant 1994), while facilitating empirical research into the different meanings and consequences of "race"in diverse places and times. It also permits a recognition of "race,""ethnicity,"and "nation" as social constructions with real consequences without falling into the realm of reification. Miles (1984) argues that because "race"is socially constructed, "there is nothing distinctive about the resulting relations between the groups party to such a social construction" (p. 220). In contrast, the approachI de8The distinction between categories of analysis and categories of practice is borrowed from Brubaker(1996), following Bourdieu (1991). According to Brubakerand Cooper (forthcoming): Reification is a social process, not only an intellectual practice.As such, it is centralto many social and political practices oriented to "nation," "ethnicity," "race," and other putative "identities." As analysts of these practices, we should certainly try to account for this process of reification, throughwhich the "political fiction" of the "nation"-or of the "ethnicgroup,""race," or other"identity"-can become powerfullyrealized in practice.But we should avoid unintentionally reproducing or reinforcing such reification

scribe here keeps open the possibility that social relations constituted by the concept of "race" may entail distinct patterns, logic, or consequences. Yet it avoids treating this historically contingent possibility as a timeless characteristicof "race"by (tautological) definition. Rejection of "race" as an analytical concept facilitates analysis of the historical construction of "race"as a practical category without reification, and thus provides a degree of analytical leverage that tends to be foreclosed when "race"is used analytically.9 TOWARD A COMPARATIVE SOCIOLOGY OF GROUP-MAKING A comparative sociology of group-making focuses analytical attention on the historically contingent relationship between processes of categorization, forms of social closure, and the construction of collective identity. By deghettoizing the study of "race"and approaching it as part of a larger field of issues related to processes and consequences of symbolic boundary construction, maintenance, and decline, one could avoid the analytical pitfalls discussed above. In turn, this perspective would furtherthe importantgoal of EBS's "racialized social system" approach: to improve upon previous frameworks for the study of "race"in order to understandmore clearly how "race"shapes social relations (p. 476). The conceptual foundation for a comparative sociology of boundary construction and group-making already exists, set forth by Weber in his classic formulation of the concept of social closure. Social closure focuses analytical attention on how groups come together and dissolve through social interaction in diverse spheres of life. The concept of social closure is inherently relational; it draws analytical attention to the ideal and

9 For example, in her exemplary analysis of the racialization of slavery and slaves in the United States, Fields (1990) rejects the use of "race" as an analytical concept in order to explain its emergence, utilization, and ideological function as a category of practice in a specific historical moment characterized by a particular, contradictory ideological configuration. Fields argues that attempts to explain "racial phenomena" in terms of "race" are no more than definitional statements (Fields 1990:100).

by uncriticallyadoptingcategories of practice as categoriesof analysis. (Emphasisin original)

COMMENT AND REPLY

897

material motivations for constructing boundaries between "us" and "them" (Weber [1922] 1968:43). In doing so, it gives priority to analysis of the relational construction or dissolution of boundaries, rather than to the "substance"on either side of the boundaries (Barth 1969).10 The concept of social closure also implies that the degree of "groupness"can vary along different dimensions; at a given time, for example, a particular "us-them"distinction may profoundly influence spouse selection but may have little effect on hiring practices. The concept of social closure highlights how social groups are constituted (to varying degrees) by the construction of symbolic boundaries (categorization) by collectivities with varying degrees of prior "groupness," and how such collectivities become groups with the potential to recognize and act upon collective interests to generate social change. Boundaries constructed through social closure may represent the interests of those on only one side, but they have implications for those on both sides. They may even become a resource for those whom they were meant to exclude or dispossess (Parkin 1979; Wallman 1978). In the approach proposed here, I accept Wacquant's(1997) claim that "to understand how and with what consequences the 'collective fiction' of 'race' is actualized," the analyst must study "thepractices of division and the institutions that both buttress and result from them" (p. 229). For the study of these practices, Wacquant(1997:230) proposes an analyticalframeworkthat focuses on five "elementary forms of racial domination": categorization, discrimination, segregation, ghettoization, and racial violence. Although his description of these practices as forms of ''racial" domination seems to be in tension with his sustained and insightful critique of the problematicnatureof "race"and "racism" as social scientific concepts, the substance of his framework could be conceptualized easily, if not more prosaically, as "elementary forms of social closure" based on imputed 10Althoughthis "substance" remainsrelevant for empiricalanalysisof specific and important cases of social closure,its relevanceis "secondary"in thatit mattersonly insofaras it both reflects and influencesthe motivationsfor social closure.

essential characteristics. Therefore, Wacquant's framework is a promising starting point for a comparative sociology of boundary constructionand group-makingthat could improve our understandingof "race"(as well as "ethnicity" and "nation") as social constructions with real consequences by incorporating them into a common framework. This is not to suggest that "social closure" is the only concept needed to understandprocesses of group-making, nor, much less, that "social closure" is itself a sufficient or comprehensive sociological theory of groupmaking. Rather,I emphasize how the concept of social closure can serve as a primaryfoundation for sociological inquiry into the construction, reproduction, or decline of symbolic boundaries. An explanatory framework built on such a foundation would provide more analytical leverage for improving our understanding of "race" than is offered by EBS's "structuraltheory of racism." A comparative historical approach to the study of "race" as a category of practice, constitutive of social relations in given contexts, has far greater analytical and theoretical potential than a "racialized social system" approach. Even if such a perspective could avoid the reification of "race,"the empirical and theoretical justifications for isolating the study of "race"are tenuous at best. Moreover, comparative analysis of social processes involved in the construction, maintenance, and decline of symbolic boundaries in diverse contexts promises to yield significant insights clarifying why particular systems of symbolic differentiation emerge and are sustained (or not), and are salient to varying degrees, at particularpoints in history. A comparative approach to the study of boundary construction and group-making built on the Weberian concept of social closure also could facilitate identification of forms of closure associated with particular symbolic-boundary dynamics (emergence, maintenance, decline). Such a framework could permit identification of the patterns of relations between particularsocial processes and particularstructuralconditions that trigger certain boundary dynamics; consequently, it could improve social scientific understanding,explanation, and theorization. These promising research avenues are foreclosed by approaches that reify "race"in

898

AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

Press. Hanchard, Michael. 1994. Orpheus and Power: The 'MovimentoNegro' of Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo, Brazil 1945-1988. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Harris, Marvin. 1970. "Referential Ambiguity in the Calculus of Brazilian Racial Identity." Mara Loveman is a Ph.D. Candidate in the DeSouthwestern Journal of Anthropology 26(1): partment of Sociology at the University of Cali1-14. fornia, Los Angeles, and a Mellon Fellow in Latin Horowitz, Donald. 1985. Ethnic Groups in ConAmerican Sociology. Her current research examflict. Berkeley, CA: University of California ines the mutual constitution of "race" and "naPress. tion" through state-building activities in nine- Ignatiev, Noel. 1995. How the Irish Became teenth century Latin America, focusing on Brazil White. New York: Routledge. in comparative perspective. Her research inter- Jenkins, Richard. 1994. "Rethinking Ethnicity: ests include "race," ethnicity and nationhood in Identity, Categorization and Power." Ethnic comparativeperspective, categorization and cogand Racial Studies 17:197-223. nitive sociology, social movements in repressive Miles, Robert. 1984. "Race Relations: Perspecstates, political sociology, and comparative histive One." Pp. 218-21 in Dictionary of Race torical methodology. She recently published and Ethnic Relations, edited by E. Cashmore. "High-RiskCollective Action: Defending Human London, England: Routledge. Rights in Chile, Uruguay and Argentina" (Ameri- Nobles, Melissa. 1995. " 'Responding with Good can Journal of Sociology, 1998, vol. 104, pp. Sense': The Politics of Race and Censuses in 477-525). ContemporaryBrazil." Ph.D. dissertation, Departmentof Political Science, Yale University, New Haven, CT. REFERENCES Omi, Michael and Howard Winant. 1994. Racial Barth, Fredrik. 1969. Ethnic Groups and BoundFormation in the United States. New York: aries: The Social Organization of Cultural DifRoutledge. ference. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Com- Parkin, Frank. 1979. Marxism: A Bourgeois Cripany. tique. New York: Columbia University Press. Bonilla-Silva,Eduardo.1997. "Rethinking Racism." Petersen, William. 1987. "Politics and the MeaAmerican Sociological Review 62:465-79. surement of Ethnicity." Pp. 187-233 in The Bourdieu, Pierre. 1990. "Social Space and SymPolitics of Numbers, edited by P. Starr and W. bolic Power." Pp. 123-39 in In Other Words: Alonso. New York: Russell Sage. Towards a Reflexive Sociology. Stanford, CA: Poulantzas, Nicos. 1982. Political Power and SoStanford University Press. cial Classes. London, England: Verso. Bourdieu, Pierre. 1991. "Identity and Represen- Roediger, David. 1991. The Wages of Whiteness. tation." Pp. 220-88 in Language and Symbolic London, England: Verso. Power. Boston, MA: HarvardUniversity Press. Stuchlik, Milan. 1979. "Chilean Native Policies Bourdieu, Pierre and Lofc Wacquant. 1999. "On and the Image of the Mapuche Indians." Pp. the Cunning of Imperialist Reason." Theory, 33-54 in Queen's University Papers in Social Culture, and Society 16(1):41-58. Anthropology, vol. 3, The Conceptualisation Brubaker, Rogers. 1996. Nationalism Reframed. and Explanation of Processes of Social Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Change, edited by D. Riches. Belfast, NorthPress. ern Ireland: Queen's University Press. Brubaker, Rogers and Frederick Cooper. Forth- Wacquant, Loic. 1997. "Towards an Analytic of coming. "Beyond Identity." Theory and SociRacial Domination." Political Power and Soety. cial Theory 11:221-34. Fields, Barbara. 1990. "Slavery, Race, and Ideol- Wagley, Charles. 1965. "On the Concept of Soogy in the United States of America." New Left cial Race in the Americas." Pp. 531-45 in ConReview 181 May-June:95-118. temporary Cultures and Societies in Latin Guillaumin, Colette. 1995. Racism, Sexism, America, edited by D. B. Heath and R. N. Power, and Ideology. London, England: Adams. New York: Random House. Routledge. Wallman, Sandra. 1978. "The Boundaries of Hacking, Ian. 1986. "Making Up People." Pp. 'Race': Processes of Ethnicity in England." 222-36 in Reconstructing Individualism: AuMan 13:200-17. tonomy, Individuality and the Self in Western Weber, Max. [1922] 1968. Economy and Society. Thought, edited by T. Heller, M. Sosna, D. Reprint, Berkeley, CA, University of CaliforWellbery. Stanford, CA: Stanford University nia Press.

their attempt to employ it analytically. To investigate and explain the causes, dynamics, and consequences of "race"as a category of practice, social scientists would be better off eliminating "race"as a category of analysis.

Você também pode gostar

- Punjabi Kinship Terminology PDFDocumento10 páginasPunjabi Kinship Terminology PDFRavijot KaurAinda não há avaliações

- Choreographies of Gender-1Documento34 páginasChoreographies of Gender-1cristinart100% (1)

- Feminist EthnographyDocumento37 páginasFeminist Ethnographysilsoca100% (1)

- Sexual Fields: Toward a Sociology of Collective Sexual LifeNo EverandSexual Fields: Toward a Sociology of Collective Sexual LifeAdam Isaiah GreenAinda não há avaliações

- Social Stigma and Identity ProcessesDocumento23 páginasSocial Stigma and Identity Processessibte akbarAinda não há avaliações

- Determinants of Human BehaviorDocumento12 páginasDeterminants of Human BehaviorAnaoj28Ainda não há avaliações

- Vieweswaran - Histories of Feminist Ethnography.Documento32 páginasVieweswaran - Histories of Feminist Ethnography.akosuapaolaAinda não há avaliações

- Girl, Interrupted: Interpreting Semenya's Body, Gender Verification Testing, and Public DiscourseDocumento16 páginasGirl, Interrupted: Interpreting Semenya's Body, Gender Verification Testing, and Public DiscoursekerembasAinda não há avaliações

- Realism, Antirealism, and Conventionalism About RaceDocumento33 páginasRealism, Antirealism, and Conventionalism About RaceJuan Jacobo Ibarra SantacruzAinda não há avaliações

- Sexuality, Class and Role in 19th-Century America. Ch. E. RosenbergDocumento24 páginasSexuality, Class and Role in 19th-Century America. Ch. E. RosenbergJosé Luis Caballero MartínezAinda não há avaliações

- Demonstrating The Social Construction of RaceDocumento7 páginasDemonstrating The Social Construction of RaceThomas CockcroftAinda não há avaliações

- Garcia - Current Conceptions of RacismDocumento38 páginasGarcia - Current Conceptions of RacismAidan EngelAinda não há avaliações

- Joan Scott's "GenderDocumento7 páginasJoan Scott's "GenderClarisse MachadoAinda não há avaliações

- Ethnicity. Problem and Focus in AnthropologyDocumento26 páginasEthnicity. Problem and Focus in AnthropologyPomeenríquezAinda não há avaliações

- The Many Faces of Social IdentityDocumento12 páginasThe Many Faces of Social IdentityYeny GiraldoAinda não há avaliações

- Race and Ethnicity.Documento29 páginasRace and Ethnicity.mia100% (1)

- Caste and Class in IndiaDocumento11 páginasCaste and Class in IndiaadityaAinda não há avaliações

- Elementary Structures Reconsidered: Levi-Strauss on KinshipNo EverandElementary Structures Reconsidered: Levi-Strauss on KinshipAinda não há avaliações

- Racial Socialization and RacismDocumento17 páginasRacial Socialization and Racism吴善统Ainda não há avaliações

- Racismor Race Play AConceptual Investigationofthe Race Play DebatesDocumento23 páginasRacismor Race Play AConceptual Investigationofthe Race Play DebatesIberê AraújoAinda não há avaliações

- Artikel Sun-Ki ChaiDocumento12 páginasArtikel Sun-Ki ChaidonashrafAinda não há avaliações

- Seeger 1989 Dualism Fuzzy SetsDocumento18 páginasSeeger 1989 Dualism Fuzzy SetsGuilherme FalleirosAinda não há avaliações

- Jaspal 2011 Caste Social Stigma and Identity ProcessesDocumento36 páginasJaspal 2011 Caste Social Stigma and Identity Processessumukh.knAinda não há avaliações

- Hays StructureAgencySticky 1994Documento17 páginasHays StructureAgencySticky 1994lingjialiang0813Ainda não há avaliações

- Always Potentially Liberated Towards NeDocumento18 páginasAlways Potentially Liberated Towards Nevmaster101 fAinda não há avaliações

- 3.anthias YuvalDavis 1983Documento15 páginas3.anthias YuvalDavis 1983Osman ŞentürkAinda não há avaliações

- Caste Social Stigma and Identity ProcessDocumento36 páginasCaste Social Stigma and Identity ProcessmartacarlosAinda não há avaliações

- Komarovsky 1950Documento10 páginasKomarovsky 1950jmolina1Ainda não há avaliações

- Charles (2008) - Culture and Inequality: Identity, Ideology, and Difference in "Postascriptive Society"Documento18 páginasCharles (2008) - Culture and Inequality: Identity, Ideology, and Difference in "Postascriptive Society"RB.ARG100% (1)

- Martha Gimenez, "Marxism and Class, Gender, Race: Rethinking The Trilogy"Documento12 páginasMartha Gimenez, "Marxism and Class, Gender, Race: Rethinking The Trilogy"Ross Wolfe100% (3)

- Interrogating WhitenessDocumento19 páginasInterrogating WhitenessPerla ValeroAinda não há avaliações

- Harrison-Ontologies of Gender and LoveDocumento23 páginasHarrison-Ontologies of Gender and LoveWalterAinda não há avaliações

- Text 2 ErotismDocumento26 páginasText 2 ErotismMadalina BorceaAinda não há avaliações

- BARTH, Fredrik - Analytical Dimensions in The Comparison of Social OrganizationsDocumento15 páginasBARTH, Fredrik - Analytical Dimensions in The Comparison of Social OrganizationsAnonymous OeCloZYzAinda não há avaliações

- Todorov RaceWritingCulture 1986Documento12 páginasTodorov RaceWritingCulture 19861210592Ainda não há avaliações

- American Anthropological Association, Wiley American EthnologistDocumento5 páginasAmerican Anthropological Association, Wiley American EthnologistangelaAinda não há avaliações

- Race and (The Study Of) EsotericismDocumento22 páginasRace and (The Study Of) EsotericismNicky KellyAinda não há avaliações

- Theorizing Relations in Indigenous South America: Edited by Marcelo González Gálvez, Piergiogio Di Giminiani and Giovanna BacchidduNo EverandTheorizing Relations in Indigenous South America: Edited by Marcelo González Gálvez, Piergiogio Di Giminiani and Giovanna BacchidduMarcelo González GálvezAinda não há avaliações

- The Cultural Contexts of Ethnic DifferencesDocumento10 páginasThe Cultural Contexts of Ethnic DifferencesAlice MelloAinda não há avaliações

- Coreografías Del Género - Susan L FosterDocumento34 páginasCoreografías Del Género - Susan L FosterJuli SorterAinda não há avaliações

- Steinmetz, G. (1998) - Critical Realism and Historical Sociology. A Review Article. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 40 (01), 170-186.Documento18 páginasSteinmetz, G. (1998) - Critical Realism and Historical Sociology. A Review Article. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 40 (01), 170-186.lcr89Ainda não há avaliações

- Alexander MulticulturalismDocumento14 páginasAlexander MulticulturalismmopemoAinda não há avaliações

- Social StructuresDocumento7 páginasSocial StructuresNaimat UllahAinda não há avaliações

- Harper PassingWhatRacial 1998Documento18 páginasHarper PassingWhatRacial 1998Pete's CoverAinda não há avaliações

- Racism and The Sociological Imagination: The British Journal of Sociology 2008 Volume 59 Issue 4Documento19 páginasRacism and The Sociological Imagination: The British Journal of Sociology 2008 Volume 59 Issue 4Jehan BimbasAinda não há avaliações

- Review Gintis BowlesDocumento5 páginasReview Gintis BowlesnicoleAinda não há avaliações

- Review of Butler's Bodies That MatterDocumento7 páginasReview of Butler's Bodies That MatterD.A. Oloruntoba-OjuAinda não há avaliações

- Epstein, S. (1994) 'A Queer Encounter - Sociology and The Study of Sexuality'Documento16 páginasEpstein, S. (1994) 'A Queer Encounter - Sociology and The Study of Sexuality'_Verstehen_Ainda não há avaliações

- This Content Downloaded From 175.208.161.193 On Fri, 18 Nov 2022 04:30:43 UTCUTCDocumento4 páginasThis Content Downloaded From 175.208.161.193 On Fri, 18 Nov 2022 04:30:43 UTCUTCZenas LeeAinda não há avaliações

- What Is Ethnic Identity and Does It Matter? Forthcoming in The Annual Review of Political ScienceDocumento29 páginasWhat Is Ethnic Identity and Does It Matter? Forthcoming in The Annual Review of Political ScienceshwetengAinda não há avaliações

- This Content Downloaded From 95.168.118.0 On Tue, 16 Feb 2021 10:40:50 UTCDocumento23 páginasThis Content Downloaded From 95.168.118.0 On Tue, 16 Feb 2021 10:40:50 UTCrenkovikiAinda não há avaliações

- RacialFormation2nd ch4 1994Documento14 páginasRacialFormation2nd ch4 1994Gmac10Ainda não há avaliações

- University of Minnesota Press Cultural CritiqueDocumento22 páginasUniversity of Minnesota Press Cultural CritiqueDavidAinda não há avaliações

- How Social Cohesion Develops in Liberal DemocraciesDocumento18 páginasHow Social Cohesion Develops in Liberal Democraciesjoaquín arrosamenaAinda não há avaliações

- Balibar - Difference Otherness ExclusionDocumento16 páginasBalibar - Difference Otherness ExclusionHerrSergio SergioAinda não há avaliações

- Totality Inside Out: Rethinking Crisis and Conflict under CapitalNo EverandTotality Inside Out: Rethinking Crisis and Conflict under CapitalAinda não há avaliações

- The University of Chicago PressDocumento26 páginasThe University of Chicago PressPedro DavoglioAinda não há avaliações

- Met Social GroupsDocumento13 páginasMet Social GroupsLenguaje SemestreAinda não há avaliações

- Notes On Community, Hegemony, and The Uses of The PastDocumento7 páginasNotes On Community, Hegemony, and The Uses of The PastIvana Lucic-Todosic100% (1)

- Comparative Policy Studies: Edited by Isabelle Engeli and Christine Rothmayr AllisonDocumento269 páginasComparative Policy Studies: Edited by Isabelle Engeli and Christine Rothmayr AllisonJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- Socioeconomic Differences in Reading Trajectories: The Contribution of Family, Neighborhood, and School ContextsDocumento17 páginasSocioeconomic Differences in Reading Trajectories: The Contribution of Family, Neighborhood, and School ContextsJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- RetrieveDocumento27 páginasRetrieveJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- Socioeconomic Status Differences in Preschool Phonological Sensitivity and First-Grade Reading AchievementDocumento12 páginasSocioeconomic Status Differences in Preschool Phonological Sensitivity and First-Grade Reading AchievementJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- Role of Out of School Factors in LiteracyDocumento16 páginasRole of Out of School Factors in LiteracyCristy EismaAinda não há avaliações

- Lahire (2019) - Sociological Biography and Socialisation Proccess PDFDocumento16 páginasLahire (2019) - Sociological Biography and Socialisation Proccess PDFJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- Transportation Research Part D: Luis A. Guzman, Daniel Oviedo, Julian Arellana, Victor Cantillo-GarcíaDocumento13 páginasTransportation Research Part D: Luis A. Guzman, Daniel Oviedo, Julian Arellana, Victor Cantillo-GarcíaJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- Boudon (1982) - The Unintended Consequences of Social ActionDocumento240 páginasBoudon (1982) - The Unintended Consequences of Social ActionJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- PioneringDocumento13 páginasPioneringJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- XXIV - Elster, Jon. 1993. Tuercas y Tornillos - Pp.31-49Documento12 páginasXXIV - Elster, Jon. 1993. Tuercas y Tornillos - Pp.31-49Javier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- Nurse or MechanicDocumento32 páginasNurse or MechanicJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- The Challenges and Opportunities of Re-Studying Community On Sheppey: Young People's Imagined FuturesDocumento20 páginasThe Challenges and Opportunities of Re-Studying Community On Sheppey: Young People's Imagined FuturesJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- Limitations of Rational Choice TheoryDocumento13 páginasLimitations of Rational Choice TheoryJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- A Pragmatist Theory of Social MechanismsDocumento23 páginasA Pragmatist Theory of Social MechanismsJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- Realizing Narratives Render Projected Futures Knowable as RealDocumento20 páginasRealizing Narratives Render Projected Futures Knowable as RealJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- Time Perspective in Adolescents and Young Adults: Enjoying The Present and Trusting in A Better FutureDocumento19 páginasTime Perspective in Adolescents and Young Adults: Enjoying The Present and Trusting in A Better FutureJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- Tironi, M. Et - Al. (2018) - Inorganic Becomings.Documento26 páginasTironi, M. Et - Al. (2018) - Inorganic Becomings.Javier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- Cultural Reception and Production, The Social Construction of Meaning in Book ClubsDocumento25 páginasCultural Reception and Production, The Social Construction of Meaning in Book ClubsJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- Boudon (2013) The Origin of Values - Sociology and Philosophy of Beliefs PDFDocumento240 páginasBoudon (2013) The Origin of Values - Sociology and Philosophy of Beliefs PDFJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- Alan Fine, Gary. Gropu Culture and Interaction Order - Local Sociology On The Meso - LevelDocumento25 páginasAlan Fine, Gary. Gropu Culture and Interaction Order - Local Sociology On The Meso - LevelJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- Chesneaux, Jean. Jules Verne's Image of The United StatesDocumento18 páginasChesneaux, Jean. Jules Verne's Image of The United StatesJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- Bajc - On Surveillance As A Solution To Security IssuesDocumento14 páginasBajc - On Surveillance As A Solution To Security IssuesJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- Amir, Samin. Against Hardt and NegriDocumento13 páginasAmir, Samin. Against Hardt and NegriJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- Abdullah, Shazila Et Al. (2012) - Reading For Pleasure As A Means of Improving Reading Comprehension SkillsDocumento7 páginasAbdullah, Shazila Et Al. (2012) - Reading For Pleasure As A Means of Improving Reading Comprehension SkillsJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- Amir, Samin. Against Hardt and NegriDocumento13 páginasAmir, Samin. Against Hardt and NegriJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- The Ritual Process Structure and Anti Structure Symbol Myth and Ritual SeriesDocumento222 páginasThe Ritual Process Structure and Anti Structure Symbol Myth and Ritual Seriesgeekc100% (5)

- War Making and State Making as Organized Protection RacketsDocumento23 páginasWar Making and State Making as Organized Protection RacketsJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- Analyticracialdominat0 WacquantDocumento8 páginasAnalyticracialdominat0 WacquantOscar Alejandro Quintero RamírezAinda não há avaliações

- Byron J Good (1977) The Heart of Whats The MatterDocumento34 páginasByron J Good (1977) The Heart of Whats The MatterJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- Emirbayer and Matthew DesmondRace - and - Reflexivity Demsond EmirbayerDocumento69 páginasEmirbayer and Matthew DesmondRace - and - Reflexivity Demsond EmirbayerJavier Fernando GalindoAinda não há avaliações

- Hencher - Interpretation of Direct Shear Tests On Rock JointsDocumento8 páginasHencher - Interpretation of Direct Shear Tests On Rock JointsMark2123100% (1)

- Interna Medicine RheumatologyDocumento15 páginasInterna Medicine RheumatologyHidayah13Ainda não há avaliações

- AP Euro Unit 2 Study GuideDocumento11 páginasAP Euro Unit 2 Study GuideexmordisAinda não há avaliações

- Startups Helping - India Go GreenDocumento13 páginasStartups Helping - India Go Greensimran kAinda não há avaliações

- LLoyd's Register Marine - Global Marine Safety TrendsDocumento23 páginasLLoyd's Register Marine - Global Marine Safety Trendssuvabrata_das01100% (1)

- Basic Calculus: Performance TaskDocumento6 páginasBasic Calculus: Performance TasksammyAinda não há avaliações

- 2.0 - SITHKOP002 - Plan and Cost Basic Menus Student GuideDocumento92 páginas2.0 - SITHKOP002 - Plan and Cost Basic Menus Student Guidebash qwertAinda não há avaliações

- LLM DissertationDocumento94 páginasLLM Dissertationjasminjajarefe100% (1)

- The Impact of Information Technology and Innovation To Improve Business Performance Through Marketing Capabilities in Online Businesses by Young GenerationsDocumento10 páginasThe Impact of Information Technology and Innovation To Improve Business Performance Through Marketing Capabilities in Online Businesses by Young GenerationsLanta KhairunisaAinda não há avaliações

- 9AKK101130D1664 OISxx Evolution PresentationDocumento16 páginas9AKK101130D1664 OISxx Evolution PresentationfxvAinda não há avaliações

- Principles of SamplingDocumento15 páginasPrinciples of SamplingziggerzagAinda não há avaliações

- Maximizing modular learning opportunities through innovation and collaborationDocumento2 páginasMaximizing modular learning opportunities through innovation and collaborationNIMFA SEPARAAinda não há avaliações

- Body Scan AnalysisDocumento9 páginasBody Scan AnalysisAmaury CosmeAinda não há avaliações

- Ogl422 Milestone Three Team 11 Intro Training Session For Evergreen MGT Audion Recording Due 2022apr18 8 30 PM PST 11 30pm EstDocumento14 páginasOgl422 Milestone Three Team 11 Intro Training Session For Evergreen MGT Audion Recording Due 2022apr18 8 30 PM PST 11 30pm Estapi-624721629Ainda não há avaliações

- Relay Coordination Using Digsilent PowerFactoryDocumento12 páginasRelay Coordination Using Digsilent PowerFactoryutshab.ghosh2023Ainda não há avaliações

- EMMS SpecificationsDocumento18 páginasEMMS SpecificationsAnonymous dJtVwACc100% (2)

- Assignment 3 Part 3 PDFDocumento6 páginasAssignment 3 Part 3 PDFStudent555Ainda não há avaliações

- Panasonic TC-P42X5 Service ManualDocumento74 páginasPanasonic TC-P42X5 Service ManualManager iDClaimAinda não há avaliações

- 277Documento18 páginas277Rosy Andrea NicolasAinda não há avaliações

- Neonatal SepsisDocumento87 páginasNeonatal Sepsisyhanne100% (129)

- DAT MAPEH 6 Final PDFDocumento4 páginasDAT MAPEH 6 Final PDFMARLYN GAY EPANAinda não há avaliações

- Impact of Recruitment & Selection on Employee RetentionDocumento39 páginasImpact of Recruitment & Selection on Employee RetentiongizawAinda não há avaliações

- Intec Waste PresiDocumento8 páginasIntec Waste Presiapi-369931794Ainda não há avaliações

- Week 6Documento7 páginasWeek 6Nguyễn HoàngAinda não há avaliações

- Principles of Cost Accounting 1Documento6 páginasPrinciples of Cost Accounting 1Alimamy KamaraAinda não há avaliações

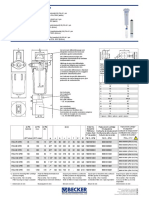

- Medical filter performance specificationsDocumento1 páginaMedical filter performance specificationsPT.Intidaya Dinamika SejatiAinda não há avaliações

- SQL 1: Basic Statements: Yufei TaoDocumento24 páginasSQL 1: Basic Statements: Yufei TaoHui Ka HoAinda não há avaliações

- Oracle Fusion Financials Book Set Home Page SummaryDocumento274 páginasOracle Fusion Financials Book Set Home Page SummaryAbhishek Agrawal100% (1)

- Learning Online: Veletsianos, GeorgeDocumento11 páginasLearning Online: Veletsianos, GeorgePsico XavierAinda não há avaliações

- C ClutchesDocumento131 páginasC ClutchesjonarosAinda não há avaliações