Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Mobile Learning Defined

Enviado por

dicksonhtsDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Mobile Learning Defined

Enviado por

dicksonhtsDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

IADIS International Conference Mobile Learning 2005

DEFINING MOBILE LEARNING

John Traxler

University of Wolverhampton Wolverhampton, WV1 1SB, UK John.traxler@wlv.ac.uk

ABSTRACT Mobile learning is new. It is currently difficult to define, conceptualise and discuss. It could perhaps be a wholly new and distinct educational format, needing to set its own standards and expectations, or it could be a variety of e-learning, inheriting the discourse and limitations of this slightly more mature discipline. This paper is a preliminary attempt to address this issue of definition and conceptualisation, and draws on recent research examining case studies from the UK and elsewhere. KEYWORDS

Mobile learning;

1. THE STATE OF MOBILE LEARNING

There is considerable evidence to suggest that mobile learning is growing in visibility and significance. First, there is the growing size and frequency of dedicated conferences, seminars and workshops, both in the United Kingdom and internationally. MLEARN 2002 (Birmingham) and MLEARN 2003 (London, which attracted more than 200 delegates from 13 countries) were followed by MLEARN 2004 (Rome) in July 2004. Another dedicated event, the International Workshop on Mobile and Wireless Technologies in Education (WMTE 2002), sponsored by IEEE, took place in Sweden in August 2002 (http://lttf.ieee.org/wmte2002/). The second WMTE (http://lttf.ieee.org/wmte2003/) was held at National Central University in Taiwan in March 2004. Another notable event was the ICML International Conference on Mobile Learning: New Frontiers and Challenges, 5-7, March 2003, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (http://www.umcced.edu.my/conference/mlearn/). There are also a growing number of national and international workshops such as the June 2002 national workshop in Telford on mobile learning in the computing discipline with 60 delegates from UK higher education (http://www.ics.ltsn.ac.uk/events) and the National Workshop and Tutorial on Handheld Computers in Universities and Colleges series held at Wolverhampton (http://www.einnovationcentre.co.uk/eic_event.htm) on 11 June 2004 and Telford on 12 January 2005, each with 95 delegates. Other European events have included The Social Science of Mobile Learning, in Budapest, on 29 November 2002 (http://21st.century.phil-inst.hu/m-learning_conference/), and the Workshop on Ubiquitous and Mobile Computing for Educational Communities: Enriching and Enlarging Community Spaces, Amsterdam, 19 September 2003 (http://www.idi.ntnu.no/~divitini/umocec2003/), part of the International Conference on Communities and Technologies. Second, there have also been a rising number of references to mobile learning at generalist academic conferences. Online Educa Berlin, the world's largest e-learning conference, annually attracts 1200 participants from over 60 countries. It includes mobile learning in its theme on Future Technologies for Learning; the latest one was held in December 2003 (http://www.online-educa.com/en/). Issues of usability and interaction with mobile devices are the focus of events such as the annual International Symposium on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, held in Italy in September 2003 http://hcilab.uniud.it/mobilehci/index.html; in Glasgow in September 2004 http://www.cis.strath.ac.uk/~mdd/mobilehci04/).

261

ISBN: 972-8939-02-7 2005 IADIS

2. MOBILE LEARNING EXAMPLES

The practice of mobile learning currently exploits both handheld computers and mobile phones.

2.1 Mobile Learning Using Handheld Computers

Mobile learning using handheld computers is obviously relatively immature in terms of both its technologies and its pedagogies but is nevertheless developing rapidly. It sometimes draws on the theory and practice of pedagogies used in technology supported learning and others used in the classroom and the community, and takes place as mobile devices are transforming notions of space, community and discourse (Katz & Aakhus, 2002), (Brown, 2001) and the investigative ethics and tools (Hewson et al, 2003). The term mobile learning covers the personalised, connected and interactive use of handheld computers in classrooms (Perry, 2003), (OMalley & Stanton, 2002), in collaborative learning (Pinkwart et al, 2003), in fieldwork (Chen, 2003) and in counselling and guidance (Vuorinen & Sampson, 2003). Mobile devices are supporting corporate training for mobile workers (Gayeski, 2002), (Pasanen, 2003), (Lundin & Magnusson, 2003) and are enhancing medical education (Smordal, 2003), teacher training (Seppala & Alamaki, 2003), music composition (Polishook, 2005), nurse training (Kneebone, 2005) and numerous other disciplines. Mobile devices are becoming a viable and imaginative component of institutional support and provision (Griswold et al, 2002), (Sariola, 2003), (Hackemer & Peterson, 2005). In many of these cases, they give uniquely situated and context-aware learning experiences but in other cases they may be reaching remote or inaccessible learners and supporting conventional learning or conventional e-learning. There is developmental work that looks at the issues of extending standards to mobile learning (Shih, 2004), of delivering usable content in mobile devices (Kukulska-Hulme, 2002) and of supporting online mobile learner communities (Salmon, 2000). There is as yet little research that looks at how the dominant pedagogies of e-learning might translate into the mobile domain (Rudman et al, 2002), (Sharples, 2001), (Luckin et al, 2003) and not a great deal of work that moves beyond using technologies provided by the market-place to looking at ones underpinned by sound pedagogic theory (Rudman et al, 2003), (Lyons, 2003). The specifics of evaluation and ethical aspects of mobile learning are only starting to be considered (Traxler, 2004), (Taylor, 2003).

2.2 Mobile Learning Using Mobile Phones

Mobile learning also covers the delivery and support of learning using mobile phones and in the last five years, mobile phones have steadily assumed a place in further and higher education in the USA, the Far East/Pacific Rim and the UK (Garner et al, 2002), (Briggs & Stone, 2002), (Alsop et al, 2002), supporting distance learners and part-time students. There has also been a growing understanding of mobile phones potential for supporting learning (Attewell & Savill-Smith, 2003) and of the evolution of cultural life and social behaviour with the take up of mobile phones in many parts of the world (Plant, 2001). There is experience of using mobile phones to deliver educational content. One study looks at SMS in learning Italian (Levy & Kennedy, 2005), another at learning literature (Hoppe, 2004). There is also experience in using mobile phones to provide study support (Traxler & Riordan, 2003). This work shows that SMS can be used to provide support, motivation and continuity; alerts and reminders; bite-size content, introductions, tips and revision; study guide structure. Experts in online learning are mapping out how to transfer their support strategies (Salmon, 2000) to SMS and anticipate the gradual transition of any SMS service from operational issues, through tutorial and pastoral support, to fully moderated asynchronous conferences.

3. DEFINING MOBILE LEARNING

Mobile learning can perhaps be defined as any educational provision where the sole or dominant technologies are handheld or palmtop devices. This definition may mean that mobile learning could include mobile phones, smartphones, personal digital assistants (PDAs) and their peripherals, perhaps tablet PCs and

262

IADIS International Conference Mobile Learning 2005

perhaps laptop PCs, but not desktops in carts and other similar solutions. Perhaps the definition should address also the growing number of experiments with dedicated mobile devices such as games consoles and iPODs, and it should encompass both mainstream industrial technologies and one-off experimental technologies.

m-learning vs. e-learning

ubiquitous static luggable mobile wearable pervasive PDA laptop PC

Figure 1.

Figure 1

tablet

phone

However any such definitions and description of mobile learning are perhaps rather technocentric, not very stable and based around a set of hardware devices. Such definitions merely put mobile learning somewhere on e-learnings spectrum of portability and also perhaps draw attention to its technical limitations rather than promoting its unique pedagogic advantages and characteristics (Figure 1). The uncertainty about whether laptops and Tablets deliver mobile learning (Figure 2) illustrates the difficulty with this definition.

m-learning vs. e-learning

e-learning

PC

m-learning

MMS SMS PDA smartphone

Figure 2

Tablet PC

laptop

Figure 2.

When we look at learning from the learners and users perspective, a definition of mobile learning becomes clearer. People use a variety of words to describe the nature of learning when it is mobile. Many of these characteristics are the core of what separates mobile learning (m-learning) from (tethered) e-learning (Figure 3) and we are beginning, just beginning, to see the emergence of a distinct mobile learning community.

263

ISBN: 972-8939-02-7 2005 IADIS

m-learning vs. e-learning

e-learning

intelligent personalised interactive

m-learning

spontaneous situated portable context-aware lightweight informal personal

media-rich institutional structured multimedia usable massive hyper-linked accessible connected

Figure 3

Figure 3.

If we look back at the examples described earlier, we can see these characteristics emerging. So there are core characteristics that define mobile learning and these characterize mobile learning as Spontaneous Private Portable Situated Informal Bite-sized Light-weight Context aware And perhaps soon Connected Personalised Interactive Examples of these attributes can be found across many or most of the recent trials, pilots and implementations of mobile learning but not in such a conclusive enough fashion to support a case that mobile learning is wholly distinct from (tethered) e-learning. Perhaps this will emerge as educationalists become more confident in exploiting and integrating the diversity of ways that mobile devices can interact with the outside world, including cameras and speech technologies. If it is to emerge, it will need to refer back to theories and accounts of for example informal learning, situated learning and bite-sized learning that have little connection with e-learning or other forms of technology supported learning. Incidentally this line of argument, namely that mobile learning is potentially a distinct phenomenon when defined in terms of learners experiences, also begs the question of whether some more traditional forms of learning are also mobile learning. But finally, once we look more closely we see some characteristics that separate and define different types of mobile learning experience (Figure 4). Latency is the waiting associated with a particular service (anyone booting up a Windows PC knows latency can be quite an overhead, anyone looking at their wristwatch knows it neednt be); mobile learning usability varies from reading and writing SMS text on a matchbox-sized device to something comparable to a desktop PC and mobile learning connectivity can vary from always-on to havent got any.

264

IADIS International Conference Mobile Learning 2005

m-learning vs. e-learning

usability laptop PDA PC

latency connectivity SMS

Figure 4 Figure 4.

Again, these apparently technical characteristics will probably have direct consequences for the nature of mobile learning (and teaching). Put simplistically, problems or limitations with usability or latency may inhibit models of teaching that concentrate on the delivery of content whereas problems or limitations with connectivity may hamper models of teaching and learning based on discourse and conversation. In more practical terms, the ability to exploit educationally the popularity of standalone downloadable games may favour a model of learning based around behaviourist practice-and-drill whilst the ability to exploit educationally any fashion for beaming or peer-to-peer connectivity may underpin a more conversational model of learning. These issues are discussed at greater length elsewhere (Kukulska-Hulme & Traxler, 2005).

4. CONCLUSION

This paper attempts to summarise the factors that will influence our understanding of mobile learning in the coming years. This understanding will itself influence the progress and direction of mobile learning and its perception and acceptance by the wider educational community. The definition and depiction of mobile learning as merely portable e-learning is a gradualist position which will ease its diffusion but weaken its contribution whereas the definition and depiction of mobile learning as something wholly new and distinct is a radical position that will make diffusion and acceptance more problematic but maintain its identity and coherence. What we have not considered here is the extent to which mobile learning could draw on discourses outside e-learning.

REFERENCES

Alsop, G., Briggs, J., Stone, A., & Tompsett, C. (2002). M-learning as a Means of Supporting Learners: Tomorrow's Technologies Are Already Here, How Can We Most Effectively Use Them in The E-learning Age?. Sheffield: Attewell, J., & Savill-Smith, C. (2003). Young People, Mobile Phones and Learning. London: Learning and Skills Development Agency. Briggs, J. & Stone, A. (2002). ITZ GD 2 TXT - How To Use SMS Effectively in M-Learning. Birmingham: Brown (2001) Wireless World: Social and Interactional Aspects of the Mobile Age; Springer: 2001 Garner, I., Francis,J., & Wales, K. (2002). An Evaluation of an Implementation of a Short Message System (SMS) to Support Undergraduate Student Learning. Birmingham: Gayeski, D. (2002). Learning Unplugged - Using Mobile Technologies for Organisational and Performance Improvement. New York, NY: AMACON - American Management Association.

265

ISBN: 972-8939-02-7 2005 IADIS

Griswold, W., Boyer, R., Brown, S., Truong, T., Bhasker, E., Jay, G., & Shapiro, B. (2002). Using Mobile Technology to Create Opportunistic Interactions on a University Campus. San Diego, CA: Computer Science and Engineering, University of California, San Diego Hackemer, K & Peterson, D. (2005) Campus-wide Handhelds In A. Kukulska-Hulme & J. Traxler (Eds.), Mobile Learning: A Handbook for Educators and Trainers. London: Routledge Hewson, C., Yule, P., Laurent, D., & Vogel, C. (2003). Internet Research Methods (N. G. Fielding & R. M. Lee, Eds.). London: SAGE Publications. Hoppe, H. U. (2004). SMS-based Discussions - Technology Enhanced Collaboration for A Literature Course. National Central University, Taiwan: Katz, J. E., & Aakhus, M. (Eds.). (2002). Perpetual Contact - Mobile Communications, Private Talk, Public Performance. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Kukulska-Hulme, A. (2002). Cognitive, Ergonomic and Affective Aspects of PDA Use for Learning. Birmingham: Kukulska-Hulme, A.; Traxler, J. Mobile Learning: A Handbook for Educators and Trainers; Routledge: London, 2005 Kneebone, R. (2005) PDAs for PSPs In A. Kukulska-Hulme & J. Traxler (Eds.), Mobile Learning: A Handbook for Educators and Trainers. London: Routledge Levy, M., & Kennedy, C. (2005). Learning Italian via Mobile SMS. In A. Kukulska-Hulme & J. Traxler (Eds.), Mobile Learning: A Handbook for Educators and Trainers. London: Routledge. Luckin, R., Brewster, D., Pearce, D., Siddons-Corby, R., & du Boulay, B. (2003). SMILE: the Creation of Space for Interaction Through Blended Digital Technology. London: Lundin, J., & Magnusson, M. (2003). Collaborative learning in mobile work. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 19(3), 273-283. Lyons, K. (2003). Everyday Wearable Computer Use: A Case Study of an Expert User. Udine, Italy: Springer. O'Malley, C. & Stanton, D. (2002). Tangible Technologies for Collaborative Storytelling. Birmingham: Pasanen, J. (2003). Corporate Mobile Learning. In H. Kynaslahti & P. Seppala (Eds.), Mobile Learning (pp. 115-123). Helsinki, Finland: IT Press. Perry, D. (2003). Handheld Computers (PDAs) in Schools. Coventry: BECTa. Pinkwart, N., Hoppe, H. U., Milrad, M., & Perez, J. (2003). Educational scenarios for cooperative use of Personal Digital Assistants. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 19(3), 383-391. Polishook, M. (2005) Music on PDAs in A. Kukulska-Hulme & J. Traxler (Eds.), Mobile Learning: A Handbook for Educators and Trainers. London: Routledge Plant, S. (2001). On the Mobile - the effects of mobile telephones on individual and social life. Motorola. Rudman, P. D., Sharples, M., & Baber, C. (2002). Supporting Learning in Conversations using Personal Technologies. Birmingham: Rudman, P. D., Sharples, M., Chan, T., & Bull, S. (2003). Evaluation of a Mobile Learning Organiser and Concept Mapping Tools. London: Salmon, G. (2000). e-moderating - the key to teaching and learning online (F. Lockwood, Ed.). London: Kogan Page. Sariola, J. (2003). The Boundaries of University Teaching: Mobile Learning as a Strategic Choice for the Virtual University. In H. Kynaslahti & P. Seppala (Eds.), Mobile Learning (pp. 71-78). Helsinki: IT Press. Seppala, P., & Alamaki, H. (2003). Mobile learning in teacher training. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 19(3), 330-335. Sharples, M. (2001). Disruptive Devices: Mobile Technology for Conversational Learning. International Journal of Continuing Engineering Education and Lifelong Learning, 12(5/6), 504-520. Smordal, O., & Gregory, J. (2003). Personal Digital Assistants in medical education and practice. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 19(3), 320-329. Shih, T (2004). Aspects of Distance Education Technologies The Sharable Content Object Reference Model, International Journal of Distance Education Technologies, 2003 Taylor, J. (2003). A Task-centred Approach to Evaluating a Mobile Learning Environment for Pedagogical Soundness. London: Traxler, J. (2004). Mobile Learning - The Ethical and Legal Challenges. Rome: LSDA. Traxler, J. & Riordan, B. (2003). Evaluating the Effectiveness of Retention Strategies Using SMS, WAP and WWW Student Support. Galway, Ireland: ICS-LTSN. Vuorinen, R., & Sampson, J. (2003). Using mobile Information Technology to Enhance Counselling and Guidance. In H. Kynaslahti & P. Seppala (Eds.), Mobile Learning (pp. 63-70). Helsinki: IT Press.

266

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- CH 3 Stoichiometry Multiple ChoiceDocumento6 páginasCH 3 Stoichiometry Multiple ChoiceSusie ZhangAinda não há avaliações

- Consumer Resistance To Innovations The Marketing Problem and Its SolutionsDocumento10 páginasConsumer Resistance To Innovations The Marketing Problem and Its SolutionsdicksonhtsAinda não há avaliações

- Mobile Wallet Adoption - The Moderating Role of Age (ACIS)Documento15 páginasMobile Wallet Adoption - The Moderating Role of Age (ACIS)dicksonhtsAinda não há avaliações

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Revisiting Technology Resistance Current Insights and Future Directions (2018)Documento11 páginasRevisiting Technology Resistance Current Insights and Future Directions (2018)dicksonhtsAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- CH 3 Stoichiometry Multiple ChoiceDocumento6 páginasCH 3 Stoichiometry Multiple ChoiceSusie ZhangAinda não há avaliações

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Applying Innovation Resistance Theory To Understand User Acceptance of Online Shopping PDFDocumento6 páginasApplying Innovation Resistance Theory To Understand User Acceptance of Online Shopping PDFdicksonhtsAinda não há avaliações

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- A Framework For Assessing The Quality of Mobile Learning - Factors of QualityDocumento10 páginasA Framework For Assessing The Quality of Mobile Learning - Factors of QualitydicksonhtsAinda não há avaliações

- Cloud Computing and e LearningDocumento10 páginasCloud Computing and e LearningdicksonhtsAinda não há avaliações

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Sains - KBSM - Physics Form 5Documento13 páginasSains - KBSM - Physics Form 5Sekolah Portal100% (9)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- Organizational Size and IT Innovation Adoption - A Meta-Analysis (I &M 2006)Documento11 páginasOrganizational Size and IT Innovation Adoption - A Meta-Analysis (I &M 2006)dicksonhtsAinda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- E Learning in Malaysian IptDocumento0 páginaE Learning in Malaysian IptdicksonhtsAinda não há avaliações

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- PFC Liang 2009Documento10 páginasPFC Liang 2009dicksonhtsAinda não há avaliações

- ISSM and VLE StudiesDocumento19 páginasISSM and VLE StudiesdicksonhtsAinda não há avaliações

- Towards A Model For M-Learning in Africa (Journal)Documento17 páginasTowards A Model For M-Learning in Africa (Journal)dicksonhtsAinda não há avaliações

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Attitude Toward ICT CompetencyDocumento8 páginasAttitude Toward ICT CompetencydicksonhtsAinda não há avaliações

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- An Analysis of The TAM in ElearningDocumento13 páginasAn Analysis of The TAM in ElearningdicksonhtsAinda não há avaliações

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Logical PositivismDocumento3 páginasLogical PositivismjoluqAinda não há avaliações

- Competency DefinitionDocumento15 páginasCompetency DefinitiondicksonhtsAinda não há avaliações

- ICT Literacy ArticleDocumento3 páginasICT Literacy ArticledicksonhtsAinda não há avaliações

- Psychometric Success Abstract Reasoning - Practice Test 1Documento13 páginasPsychometric Success Abstract Reasoning - Practice Test 1Ambrose Zaffar75% (16)

- Digital Library Adoption and The Technology Acceptance ModelDocumento19 páginasDigital Library Adoption and The Technology Acceptance ModeldicksonhtsAinda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Understanding Digital Library AdoptionDocumento10 páginasUnderstanding Digital Library AdoptiondicksonhtsAinda não há avaliações

- Attitude Toward ICT CompetencyDocumento8 páginasAttitude Toward ICT CompetencydicksonhtsAinda não há avaliações

- Maths 05Documento16 páginasMaths 05dicksonhtsAinda não há avaliações

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Security Issues in Mobile Payment Systems Shivani AgarwalDocumento11 páginasSecurity Issues in Mobile Payment Systems Shivani Agarwalprudviraj.bv@gmail.comAinda não há avaliações

- IATA Industry Outlook Sept2012Documento4 páginasIATA Industry Outlook Sept2012Fabrice BugnotAinda não há avaliações

- IATA Financial Forecast - June 2013Documento4 páginasIATA Financial Forecast - June 2013awang90Ainda não há avaliações

- Digital Library Adoption and The Technology Acceptance ModelDocumento19 páginasDigital Library Adoption and The Technology Acceptance ModeldicksonhtsAinda não há avaliações

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (120)

- A Framework For Evaluation of VLEsDocumento46 páginasA Framework For Evaluation of VLEsdicksonhtsAinda não há avaliações

- 2-Bms FeaturesDocumento17 páginas2-Bms FeaturesMostafa AliAinda não há avaliações

- 3-D Numerical Analysis of Orthogonal Cutting Process Via Mesh-Free MethodDocumento16 páginas3-D Numerical Analysis of Orthogonal Cutting Process Via Mesh-Free MethodpramodgowdruAinda não há avaliações

- How To Create Sales Document Type in SAPDocumento10 páginasHow To Create Sales Document Type in SAPNikhil RaviAinda não há avaliações

- Latex Tutorial: Jeff Clark Revised February 26, 2002Documento35 páginasLatex Tutorial: Jeff Clark Revised February 26, 2002FidelHuamanAlarconAinda não há avaliações

- Dse7510 Installation InstDocumento2 páginasDse7510 Installation InstZakia Nahrisyah100% (1)

- Spatial DatabaseDocumento28 páginasSpatial DatabasePravah ShuklaAinda não há avaliações

- RMAN Basic CommandsDocumento5 páginasRMAN Basic CommandsAnkit ThakwaniAinda não há avaliações

- ONTAP 90 Antivirus Configuration Guide PDFDocumento34 páginasONTAP 90 Antivirus Configuration Guide PDFdarshx86Ainda não há avaliações

- Poh F15eDocumento167 páginasPoh F15ejandriolliAinda não há avaliações

- IJACSA Volume10No9 PDFDocumento617 páginasIJACSA Volume10No9 PDFAli AbbasAinda não há avaliações

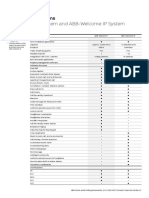

- ABB-Welcome System and ABB-Welcome IP System: Door Entry SystemsDocumento1 páginaABB-Welcome System and ABB-Welcome IP System: Door Entry SystemspeteatkoAinda não há avaliações

- Ecoson V Rev 1.5 06.2012 Catalogue enDocumento16 páginasEcoson V Rev 1.5 06.2012 Catalogue enAlfavet EirlAinda não há avaliações

- Datasheet Yealink Vp530 enDocumento2 páginasDatasheet Yealink Vp530 enfastoreldaAinda não há avaliações

- İstanbul Aydın University: 1. Project ProposalDocumento11 páginasİstanbul Aydın University: 1. Project ProposalSafouh AL-HelwaniAinda não há avaliações

- Informatica Training - Presentation TranscriptDocumento10 páginasInformatica Training - Presentation TranscriptSai KiranAinda não há avaliações

- Sinorix STD SiemensDocumento6 páginasSinorix STD SiemensAlesianAinda não há avaliações

- VIZIMAX - SynchroTeq - Customer Product Catalog EN - 2019 - 20181019Documento11 páginasVIZIMAX - SynchroTeq - Customer Product Catalog EN - 2019 - 20181019Luis Angel Huaratazo HuallpaAinda não há avaliações

- Comparison of Query Performance in Relational A Non-Relation Databases Comparison of Query Performance in Relational A Non-Relation DatabasesDocumento8 páginasComparison of Query Performance in Relational A Non-Relation Databases Comparison of Query Performance in Relational A Non-Relation DatabasesJuan HernándezAinda não há avaliações

- Visualsoft Suite User Manual Visual: Overlay 10.4Documento60 páginasVisualsoft Suite User Manual Visual: Overlay 10.4cristianocalheirosAinda não há avaliações

- Résumé: P.Arpita Kumari Prusty Thryve Digital Health LLPDocumento6 páginasRésumé: P.Arpita Kumari Prusty Thryve Digital Health LLPAshish KAinda não há avaliações

- 30 60 90 IFC What Is The Progress of EngineeringDocumento32 páginas30 60 90 IFC What Is The Progress of EngineeringRyo DavisAinda não há avaliações

- Lab 5 InstruLectureDocumento13 páginasLab 5 InstruLectureusjpphysicsAinda não há avaliações

- TutDocumento19 páginasTutalbertshoko68440% (1)

- Lecture 3 PDFDocumento43 páginasLecture 3 PDFRaziaSabeqiAinda não há avaliações

- Applied Machine Learning For Engineers: Introduction To NumpyDocumento13 páginasApplied Machine Learning For Engineers: Introduction To NumpyGilbe TestaAinda não há avaliações

- ConcepcionEstructuralProyectoyAsisteNATBarajas HyA239Documento30 páginasConcepcionEstructuralProyectoyAsisteNATBarajas HyA239Daniel Prince Cabello MezaAinda não há avaliações

- Term Year 2016-2017: Technology Support Services Comptia A+ SyllabusDocumento6 páginasTerm Year 2016-2017: Technology Support Services Comptia A+ SyllabusJennifer BurnsAinda não há avaliações

- RealEstate ReportDocumento36 páginasRealEstate ReportAnupriya Gupta0% (1)

- Clean Wipe Symantec READMEDocumento2 páginasClean Wipe Symantec READMEShady El-MalataweyAinda não há avaliações

- 1 s2.0 S2095809918301887 MainDocumento15 páginas1 s2.0 S2095809918301887 MainBudi Utami FahnunAinda não há avaliações

- The End of Craving: Recovering the Lost Wisdom of Eating WellNo EverandThe End of Craving: Recovering the Lost Wisdom of Eating WellNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (80)

- Sully: The Untold Story Behind the Miracle on the HudsonNo EverandSully: The Untold Story Behind the Miracle on the HudsonNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (103)

- Highest Duty: My Search for What Really MattersNo EverandHighest Duty: My Search for What Really MattersAinda não há avaliações

- Hero Found: The Greatest POW Escape of the Vietnam WarNo EverandHero Found: The Greatest POW Escape of the Vietnam WarNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (19)

- The Beekeeper's Lament: How One Man and Half a Billion Honey Bees Help Feed AmericaNo EverandThe Beekeeper's Lament: How One Man and Half a Billion Honey Bees Help Feed AmericaAinda não há avaliações

- ChatGPT Money Machine 2024 - The Ultimate Chatbot Cheat Sheet to Go From Clueless Noob to Prompt Prodigy Fast! Complete AI Beginner’s Course to Catch the GPT Gold Rush Before It Leaves You BehindNo EverandChatGPT Money Machine 2024 - The Ultimate Chatbot Cheat Sheet to Go From Clueless Noob to Prompt Prodigy Fast! Complete AI Beginner’s Course to Catch the GPT Gold Rush Before It Leaves You BehindAinda não há avaliações

- The Intel Trinity: How Robert Noyce, Gordon Moore, and Andy Grove Built the World's Most Important CompanyNo EverandThe Intel Trinity: How Robert Noyce, Gordon Moore, and Andy Grove Built the World's Most Important CompanyAinda não há avaliações

- Faster: How a Jewish Driver, an American Heiress, and a Legendary Car Beat Hitler's BestNo EverandFaster: How a Jewish Driver, an American Heiress, and a Legendary Car Beat Hitler's BestNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (28)

- The Fabric of Civilization: How Textiles Made the WorldNo EverandThe Fabric of Civilization: How Textiles Made the WorldNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (57)