Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Old Testament and Anti-Usurial Laws

Enviado por

Ryan Hayes0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

50 visualizações0 páginaOld Testament and Anti-usurial Laws

Título original

Old Testament and Anti-usurial Laws

Direitos autorais

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoOld Testament and Anti-usurial Laws

Direitos autorais:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

50 visualizações0 páginaOld Testament and Anti-Usurial Laws

Enviado por

Ryan HayesOld Testament and Anti-usurial Laws

Direitos autorais:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 0

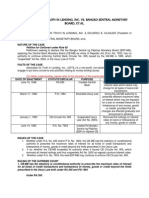

ETH/KOF Arbeitspapiere Nr.

49, April 1997

The Old Testament Anti-Usury Laws Reconsidered:

The Myth of Tribal Brotherhood

Thomas Moser

1

ABSTRACT

While there was in general no negative attitude towards interest on loans in the ancient Near

Eastern civilizations it was the moral commands of the Hebrew Bible that viewed the concept of

interest taking on loans - at least to any member of the community of Israel - as a morally

questionable practice. All of the three legal codes of the Old Testament contain a law prohibiting

the lending on interest whereby the prohibition in the Code of the Covenant in the book of

Exodus is generally agreed to be the oldest. This thrice repeated prohibition against lending for

interest in the Pentateuch is therefore often regarded as the result of a primitive economic

standard and the specific kinship morality of a tribal society. A closer look at the subject seems

to prove this general opinion of most scholars to be a historical myth. In the light of recent

historical research the Hebrew condemnation of lending at interest is neither in striking contrast

with the traditions of Israels ancient neighbors nor rested on very different grounds to the ideas

of Plato.

The Biblical prohibition against lending at interest was formulated by the Deuteronomic

school as part of an ideal law for a new post-exile Israel. It was the utopian response to the

ethical demands of the prophetic thematization of justice after Israels economy had entered the

stage of early capitalism. Therefore it was not the authors of Deuteronomy, who formulated the

prohibition in a stricter way than the traditional Covenant. It was the authors of Deuteronomy,

who were the first to formulate the prohibition, and it was the Deuteronomistic school, which

extended the other codes with a prohibition against lending at interest based on the

Deuteronomic Code. The Old Testament anti-usury laws are but one of the many utopian ethical

demands that had a profound influence on the life and thought of the Western World.

1 Introduction

Credit arrangements and the concept of interest are at least as old as the recorded history of

human society itself, even writing seems to have its origin in the need to record debts and

credits. Documented contracts from the Sumerian civilization c. 3000 BC reveal a systematic

1

Correspondence may be addressed to Thomas Moser, Center for Research of Economic Activity (KOF), Swiss

Federal Institute of Technology Zurich, ETH-Zentrum, CH-8092 Zurich, Fax: (++41)-1-632 12 34, e-mail:

moser@kof.reok.ethz.ch. I would like to thank Prof. Franz Ritzmann, Prof. Andreas Zimmermann (University

of Zurich), and Prof. Andr Lapidus (Universit de Paris I Panthon-Sorbonne). This paper was presented at the

ESHET Annual Conference in Marseille, 27 February - 2 March 1997.

- 2 -

use of credit.

2

All aspects of the loans were left up to the contracting parties, but most common

were loans of grain at annual rates of 20-50% and loans of silver at 12-30%

3

. The main

creditors were temples, royal treasuries, and private citizens while the main debtors were

farmers and traders

4

. A general feature of all credit arrangements in the ancient Near East is the

fact that interest was an ordinary and an accepted collateral of loans. Although some legal codes

mention some interest rates that generally have been interpreted as maximum rates

5

, not one

single law that prohibits interest or even any other record that states a negative attitude towards

the taking of interest is known.

6

The Hebrew Bible which was to become the Christian Old Testament, on the other hand, con-

tains several negative statements towards the concept of interest-taking, and each of its three

legal codes states an explicit usury

7

prohibition. This striking contrast, with the traditions of the

neighboring Near Eastern civilizations, has given rise to scholarly controversy. Generally two

solutions are offered: (1) That the Hebrew scriptures reflect an economy that was much less de-

veloped than that of its neighbors, and the biblical commandments therefore express a kinship

morality of a tribal society (Nelson 1949). (2) That the Hebrew society was different because

of its religious belief in a God, who demanded justice and protection for the poor. In the light of

recent historical research, both arguments can not be maintained. The second argument can eas-

ily be rejected since the demands of justice and protection for the poor was a common feature of

ancient Near Eastern Gods

8

. Furthermore, the most outstanding creditor in the ancient Near

Eastern economy was the temple of Samas, god of justice, who had its own interest-rate and

whose temple is believed to be the first bank in the world (Bromberg 1942).

9

The problem

with the first argument is that it takes the historical background set out in the Bible more or less

for granted. If put in the right historical context, it can be shown that just as in ancient Greece

and Rome, the first negative statements about the concept of interest were raised during the most

prosperous periods in Israelite economic history.

2 The Legal Codes of the Old Testament

The first five books of the Old Testament (Pentateuch), which according to the Jewish classifi-

cation form the Law (torah), embody three ancient Hebrew legal codes: the Code of the

Covenant (Ex 20:22-23:33), the Law of Holiness (Lev 17-26), and the Deuteronomic Code

(Deut 12-26). Each of these codes contains a law prohibiting interest-taking. Before we take a

2

Van de Mieroop (1992, 94): Lending was a very profitable business in Mesopotamia as can be seen from the

great number of entrepreneurs who involved themselves with it. For several examples of such loans translated

into English see Bromberg (1942), Homer (177, 29), and Van de Mieroop (1992). The most comprehensive

survey is given by Bogaert (1966).

3

See San Nicol (1938), Leemans (1950), and Bogaert (1966).

4

Zettler (1992, 107-109) proved that at least in one case the temple of Inanna at Nippur during Ur III (c. 2112-

2004 BC) borrowed as an institution to cover its deficit.

5

Code of Eschnunna (c. 19th century BC): 33.3% for grain (20) and 20% for silver (21); the same rates are

mentioned in Code of Hammurabi (c. 18th century BC, 70).

6

What we can find are several liquidations of debts via royal proclamations and proverbs that warn against going

into debt. See the Teachings of Amen-em-ope (c. 1200 BC): Do not spend tomorrows riches, todays wealth

is all you own or the Teachings of Ahiquar (c. 700 BC): Receiving a loan is sweet ..., Repaying a loan may

cost all you possess (9,130-135). See Moser (1997, 1998).

7

The term usury stems from the Latin term usura, which in Roman Law denoted the payment for the use of a

loan of any non-specific good. The modern term interest evolved from the Medieval Latin word interesse, a

payment for damages arising to the creditor from default or delay in repayment (the quod interest of Roman

Law). In this paper I will use usury and interest as synonyms.

8

See Matthews, V.H. and D.C. Benjamin (1991), and Boecker (1976)

9

It also has to be noticed that the Old Testament term justice (tsaedaeq) attributed to God refers to the contrac-

tual relationship between God (Yahweh) and his people (Israel) and has the meaning of fidelity or loyalty

towards this Covenant. It goes without saying that such a justice is extremely encouraging for credit ar-

rangements.

- 3 -

closer look at these laws, a preliminary aspect needs to be emphasized. The legal Codes of the

Old Testament are often said to be in outstanding contrast to other ancient Near Eastern Codes.

But it should be recognized that these legal laws have been adapted to the Hebrew scriptures.

Therefore their selection as well as their editing was religiously motivated. Contrary to other

Near Eastern civilizations, we do not know of any pure Hebrew civil Law Code. In my opin-

ion, this seems to be the main reason for their fusion of religious commandments and secular

regulations. It is the aim of this study to show that the usury-laws in the Old Testament have no

secular history.

2. 1 Interest Prohibition in the Book of Covenant: Ex 22:24

10

The Book of the Covenant (Ex 20:22-23:33) is generally agreed to be the oldest legal Code in

the Old Testament. The laws in Ex 21:12-22:16 in particular, are believed to be an outcome of

secular jurisdiction. These legal decisions seem to have been transmitted as a purely secular

Law Code until the 9th/8th century BC before it was edited and theologized in the 8th or 7th

century BC, under the influence of the early prophetic movement. As a result, the Book of

the Covenant was on the one hand enlarged by sacred and social demands, and on the other

hand stylized as a divine speech, before it was incorporated into a salvation history of the

children of Israel, as a part of the Pentateuch - which by itself had been again subject to a long

process of editing in the following centuries. These results of recent research have not been

included into the history of economic thought . From the fact that the Book of the Covenant is

regarded as the oldest of the three law legal codes, most scholars draw the conclusion that Ex

22:24 is the oldest formulation of the three interest prohibitions

11

. The Law reads as follows

12

:

[Ex 22:24a] If you lend money to any of my people with you who is poor

[Ex 22:24b] you shall not be to them as a creditor

[Ex 22:24c] and you shall not exact interest from him.

Wellhausen in 1876

13

and more recently Schweinhorst-Schnberger (1990, 358) have con-

firmed in great detail that Verse 24c is a secondary supplement to Ex 22:24.

14

It was added to-

gether with the expression of my people in Verse 24a (to stylize it as a divine speech) by a

deuteronomistic editor to adapt it to the interest prohibition in Deut 23:20. This has already been

pointed out by Hejcl (1907, 65), Neufeld (1955) and Klingenberg (1977, 16), but only Hejcl

posed the crucial question, if Ex 22:24 without those supplements can still be called a law that

prohibits interest taking, to which he answers positively.

In its original formulation: If you lend money to any(body) with you who is poor, you shall

not be to them as a creditor, it commands the moneylender not to behave like a creditor

(noseh, in older Bible versions translated as usurer) towards the (poor) debtor . The crucial

question therefore is: what is it that makes somebody a noseh. It is only if his significant feature

would be to take interest, then Ex 22:24 could still be called the oldest known interest prohibi-

tion. But it can be shown that the characteristic feature of a noseh is not that he takes interest,

but that he, contrary to the ordinary money-lender, loaned money to a debtor who guaranteed

10

According to English translations of the Bible and the Latin Vulgate Ex 22:25. For the following general in-

formation about the Book of the Covenant see Westbrook (1985), Schwienhorst-Schnberger (1990), and

Smend (1989).

11

Baeck 1994, Gordon 1982, Klingenberg 1977, Gamoran 1971, Meislin/Cohen 1963/64, Neufeld 1955, Stein

1953. Their dates range from 1280 BC (Klingenberg 1977) up to the 8th century BC (Meislin/Cohen). But

Hejcl (1906, 67) rightly pointed out that this law only deals with money (silver), and that this is very unlikely

to be the main concern for a tribal clan, and Neufeld (1955) has emphasized that the single laws of the Book

of the Covenant do not at all reflect the primitive economy that its narrative context presupposes.

12

All passages are from the English translation of the Old Testament known as the Revised Standard Version.

13

Jahrbcher fr deutsche Theologie 21, 1876.

14

The most obvious though not clearly recognizable hint in the English Version is that the you in 24c is plural

while 24a and 24b formulate a you singular.

- 4 -

with his own body for the security of the loan

15

. The conclusion therefore must be, that Ex

22:24 originally had nothing to say about interest-taking, and therefore was not an interest-pro-

hibition.

16

In its original formulation, it commands the creditor not to enslave the debtor in the

case of default. This is a very prominent problem in ancient history. The prohibition of loans on

personal security was one of the laws that was introduced in ancient Greece through Solons

reform, at the close of the seventh century BC. Similar laws and edicts, which are believed to

have influenced Solon, have actually a long history in the laws of the ancient Near East

17

. On

the other hand, it can still be questioned if Ex 22:24 even in its original formulation was a real

legal law at all.

18

However, to summarize our conclusion we can say, that Ex 22:24 initially did

not prohibit interest. The interest prohibition was added by a deuteronomistic editor, to comply

with the prohibition in the Book of Deuteronomy.

2. 2 Interest Prohibition in the Law of Holiness: Lev 25:35-37

The legal Code called the Law of Holiness (Lev 17-26) is less consistent and more theologized

than the Book of the Covenant. It seems to draw its material from a large number of differing

sources and its editing was carried out in several stages even before it was incorporated into the

Pentateuch. It is generally agreed, that there is an affinity between the Law of Holiness, and

the Book of Ezekiel regarding its contents and its time of formation. Both Books are believed to

have been edited by the same intellectual circles. According to Cholewinski (1976, 337) the

Law of Holiness was composed by Jerusalems clergy in Babylonian Exile (586-538 BC) as

a revision or counter-proposal to the Deuteronomic Code. It is not beyond question that it

contains some real civil laws, but on the whole the Law of Holiness was composed as a re-

ligious text for its incorporation into the Deuteronomic salvation history. The major concern of

its composers was the reorganization of a New Israel-to-be after the return from Babylonian

Exile. The interest prohibition reads:

[Lev 25:35] And if your brother becomes poor, and cannot maintain himself

with you, you shall maintain him; as a stranger and a sojourner he shall live with

you. [36] Take no interest from him or increase, but fear your God; that your

brother may live beside you. [37] You shall not lend him your money at interest,

nor give him your food for profit.

According to Cholewinskis analysis (1976, 101-103.), the original chapter Lev 25 consisted of

four parts, each starting with: and if your brother becomes poor (v.25; v.35; v.39; v.47).

They all try to mitigate possible consequences that could emerge out of economic distress:

If economic distress led to the sale of agricultural land, this land had to be returned to its

original owner at the next Jubilee Year, which occurred every 50 years (v.25f.).

If economic distress led to indebtedness, the creditor was not to ask for interest (v.35f.).

If economic distress led to enslavement, that person had to be released at least at the next

Jubilee Year (v.39f.).

If economic distress led to enslavement and the slave-owner was a foreigner, the

debtors fellow-Jews are asked to pay for his release and let him work out his debt

(v.47f.).

15

See Schwienhorst-Schnberger (1990, 358) and Hossfeld/Reuter, noseh, Theologisches Wrterbuch des Alten

Testaments. See also Isaiha 24:2 which mentions first the ordinary debtor and then the noseh.

16

Neufeld (1955) also mentioned that noseh means literally one who lends money upon pledge, but he did not

draw any conclusion from this fact. Klingenberg (1977, 29) even stated himself that V.24ab does not say any-

thing about interest-taking, but his conclusion was that this was exactly the fault of this law since it was in-

tended to be an interest prohibition (?) and insofar the cause for the supplement.

17

See Kraus (1984).

18

Cuneiform laws are usually formulated in the 3rd. person singular and entail a punishment. See Boecker (1976)

- 5 -

In this context Lev 25:35-37 resembles a law to be found in the Code of Hammurabi (c. 18th

century BC), which requires the debtor to temporarily forgo the interest if the debtor finds him-

self in a situation of economic distress. It states that a debtor, whose field gets flooded, or who

has a bad harvest from lack of water, does not have to pay the interest on his debts during that

particular year (CH 48). It is possible that Lev 25:35-37 had a similar intention

19

. On the other

hand, it is also possible, that the law was formulated with regard to Deut 23:20 (Cholewinski

1976, 302). A certain parallel can also be seen in Deut 15:7-11 which demands that one helps a

person that gets into a situation of economic distress on receipt of a loan.

The main controversy with Lev 25:35-37 evolved around the two different terms that it uses for

interest: nesek and tarbit. The first term nesek, usually translated into interest (or usury) is

also used in the two other interest prohibitions (Ex 22:24; Deut 23:20-21). The ancient transla-

tions; the Greek Septuagint and the Latin Vulgate also translate it into the common terms for in-

terest (tokos, respectively usura). The term tarbit, usually translated into increase also receives

more unusual terms for interest in the ancient translations of the Hebrew scriptures. The ques-

tion that has arisen since antiquity is: do both of these terms differ in their meaning? The most

prominent stated opinions are: (a) That nesek occurs in a loan of money, while tarbit occurs in a

loan of natural produce (Loewenstamm 1969; Gamoran 1971). The main problem with this in-

terpretation is that in Deut 23:20 nesek is used for a loan of money as well as for a loan of

victuals. (b) That nesek refers to a discount taken initially from the sum lent, while the term

tarbit denounces a regular payment of interest (Neufeld 1955; Meisilin/Cohen 1963/4; Gordon

1982). (c) That there is no difference in meaning at all. This was already concluded by the

Talmud and seems also to follow from the ancient translations of the Hebrew Scriptures. On the

whole this does not change our conclusion, that it is also most likely that Lev 25:35-37 was

founded on the interest prohibition in the Deuteronomic Code.

2. 3 Interest prohibition in the Deuteronomic Code: Deut 23:20-21

20

The Deuteronomic Code (Deut 12-26) seems also to have been subject to a long and compli-

cated process of editing. Its fusion of religious cult, civil laws, and personal ethics goes even

further than in the Law of Holiness. Its origin is often associated with the reform of King

Josiah in 622 BC, while its editing and enlargement is supposed to have been undertaken by the

royal scholars in Jerusalem. This thesis gets further support by the fact that its contents seems to

show more affinity towards the Wisdom literature of the Old Testament than towards the

Prophetic literature (Perlitt 1994, 86). Other scholars have brought forward several reasons

for a later dating. Additionally, it has been doubted that the Code contains any true legal laws,

and some scholars see it exclusively as a literary construction, either to explain the implications

of the Old Testament narratives, or to serve as a Utopian constitution for a post-exile Israel

(Hoffmann 1980). The general agreement seems at least to be that the Deuteronomic Code

does not pre-date the 7th century BC. However, it has been shown that the Deuteronomic

Code itself, shortly thereafter, became the model to a Deuteronomistic school

21

which is re-

sponsible for a lot of the editing in the entire Pentateuch. The law concerned with interest-taking

runs as follows:

[Deut 23:20] You shall not lend upon interest to your brother, interest on money,

interest on victuals, interest on anything that is lent for interest.

[Deut 23:21] To a foreigner you may lend upon interest, but to your brother you

shall not lend upon interest; that Yahweh your God may bless you in all that you

undertake in the land which you are entering to take possession of it.

19

Particularly with regard to the fact that in the context of a loan, to be in need can only be meaningful in the

case of temporary distress. Since a loan is an (intertemporal) exchange and not a donation, a needy person will

not find a lender, since the poor persons problem is not really the payment of the interest but the repayment of

the loan itself.

20

Deut 23:19-20 according to English translations and the Latin Vulgate.

21

According to the different stages of this deuteronomistic editing process, recent research has so far distinguished

at least three editors (or schools of editors): a deuteronomistic historian (DtrH), a nomistic editor (DtrN), pri-

marily interested in the Law, and a third deuteronomistic editor reflecting prophetic interest (DtrP). See further

Smend (1989).

- 6 -

This prohibition has three special features in comparison with the other laws. Firstly, the object

of the loan is described as anything that is lent for interest. Secondly, there is no mention of

the economic situation of the debtor. But the commonly stated opinion, that this means an inten-

sification of the prohibition can not be maintained in the light of the chronology we have just

established. Finally, it is the only law that not only implicitly seems to be limited to the Jewish

community, but that even explicitly allows to take interest from foreigners (nokri). This has

given rise to debate throughout the Ages.

22

But this differentiation between Israelites and for-

eigner is actually undertaken on several occasions in the Book of Deuteronomy (see 14:21; 15:3;

17:15; 28:12; 28:44). It has also to be mentioned that the formulation of the law does not give

the impression of a civil law, especially in the light of Near Eastern Law in general, and par-

ticularly in regards to some of the laws in the Book of the Covenant.

Overall, we can conclude, that since both of the other interest prohibitions (Ex 22:24; Lev

25:35-37) depend on the interest prohibition in the Deuteronomic Code, that the oldest law

prohibiting interest-taking in the Old Testament does not pre-date the 7th BC. According to

Silver (1983) the 8th and 7th century BC were economically the most prosperous periods in Is-

raelite history. It is commonly known that Plato (427-348 BC) and Aristotle (384-322 BC) were

critics of the democratic Athens, that had turned itself into a commercial center, and that they

condemned also the concept of interest-taking. Plato included in his work known as the Laws

(Nomoi) an explicit interest prohibition in the Utopian constitution of his state (polis):

... no one shall deposit money with another whom he does not trust as a friend,

nor shall he lend money upon interest; and the borrower should be under no

obligation to repay either capital or interest [Nomoi 5,742c]

3 Attitudes towards Interest in the Prophets and the Writings

The only Prophet in the Old Testament that actually states his attitude towards interest-taking is

Ezekiel, who was in Exile in Babylon, and whose first prophecy was made in 597 BC. His sev-

eral statements about interest-taking were to become very popular among the later Christian

Church Fathers. On one hand, his statements can be found in Chapter 18 where he is talking

about the conduct of the just man, who does not lend at interest or take any increase (Ez

18:8, see also Ez 18:17), while the robber, a shedder of blood, lends at interest, and takes

increase and shall not live therefore (Ez 18:13). On the other hand, he talks about interest tak-

ing in his so-called accusation against Jerusalem:

In you men take bribes to shed blood; you take interest and increase and make

gain of your neighbours by extortion; and you have forgotten me, says the God

Yahweh. [Ez 22:12]

As we have already stated that there is a relation between the circle around Ezekiel and the edi-

tors of the Law of Holiness, it is not surprising that both terms for interest, nesek and tarbit,

can be found here. But there is no general agreement on the question if these sayings go back to

Ezekiel himself or to the editors of his book. For our purpose, it is sufficient to show that

among the books of the Prophets we can not find a single statement critical of the taking of

interest that extends back further than the 6th century BC.

If we turn to the last group of books in the Old Testament, the Writings, there are two

statements about interest-taking. The first one is in the Book of Psalms which basically features

religious lyrics. It contains several single collections, and is believed to have served as a song-

book for the Jewish community of the Second Temple (515-450 BC). It is also during this

time that most of its material was written, although single Psalms can originate from different

time periods. Ps 15

23

asks in its first line: Yahweh, who will sojourn in your tent? , to which

Verse 5 answers: who does not put out his money at interest, and does not take a bribe against

the innocent... (Ps 15:5). According to Beyerlins analysis (1985) Verse 5 belongs to the

22

The first Christian writer that tried to explain this was Ambrose of Milan (339-397 AD) in his treatise De

Tobia.

23

According to the Septuagint and the Vulgate as well as to English translations Ps 14.

- 7 -

original formulation and shows obvious affinity with Ez 18 and Ez 22. He comes to the conclu-

sion that they both must originate from a mutual source. In his view, Ps 15:5 was composed

after the Exile (586-538 BC).

24

The second statement in the Writings is to be found in the Book of Proverbs which be-

longs to the Wisdom literature. But the statement can not as clearly be said to show a negative

attitude towards the concept of interest-taking:

He who augments his wealth by interest and increase gathers it for him who is

kind to the poor. [Prov 28:8]

Although it seems to state a negative attitude towards interest, this can not be concluded for cer-

tain since the Book of Proverbs also contains several statements that oppose such an attitude

(see Prov 16:26; 17:8; 22:16, 29:19). On the whole, this statement does not give strong support

for any interest prohibition in ancient Hebrew society before the 7th century BC.

4 Conclusion

In summarizing the results of this analysis, it can be concluded, that the interest prohibition in

the Deuteronomic Code is probably the oldest declaration in the entire Old Testament, forbid-

ding the taking of interest from a fellow Jewish member of the community. But at the same time

it explicitly allows one to take interest from a foreigner. The statement has its origin in the

flourishing Israelite economy of the 7th century BC, formulated by the authors of the Book of

Deuteronomy (or the deuteronomistic school), probably as part of an Utopian constitution

for an ideal Israel. The interest prohibitions in the Book of Exodus and Leviticus have been

inserted at a later date to comply with Deut 23:20-21. It is at this same period in time that Ezekiel

or his editors articulated a similar negative attitude towards usury. This probably occurred in the

context of the prosperous economy of Babylon. On the whole, it seems that the Hebrew anti-

usury laws are but one of the many utopian ethical ideals, that had a profound influence on the

life and thought of the Western World. Particularly, when in the 2nd century AD the Christian

Church definitively decided to adopt the Hebrew Bible as the Old Testament of its Christian

Scriptures.

24

It is interesting to notice that Ps 15:5 was to become the most important quotation for the early Christian

Church as a argument against usury. Canon 17 of the first general Council of Nicaea in 325 AD, which was

the first and most important canonical prohibition against usury for the entire Christian Church, quoted Ps

15:5.

- 8 -

5 References

Baeck, L.: The Mediterranean tradition in economic thought. London and New York, 1994

Beyerlin, W.: Weisheitlich-kultische Heilsordnung zum 15. Psalm. Neukirchen, 1985.

Boecker, H.J.: Recht und Gesetz im Alten Testament und im alten Orient. Neukirchen-Vluyn,

1976.

Bogaert, R.: Les origines antiques de la Banque de dpt: Une mise au point accompagne

dune esquisse des oprations de banque en Msopotamie. Leyden, 1966.

Bromberg, B.: The origin of banking: religious finance in Babylonia. Journal of Economic

History, Vol. 2, 1942, pp.77-88.

Cholewinski, A.: Heiligkeitsgesetz und Deuteronomium: Eine vergleichende Studie. Rome,

1976.

Gamoran, H.: The biblical law against loans on interest. Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol.

30, 1971, pp.127-134.

Gordon, B.: Lending at interest: some Jewish, Greek, and Christian apporaches 800 BC-

AD 100. History of Political Economy, Vol. 14, 1982, pp.406-426.

Haase, R.: Die keilschriftlichen Rechtssammlungen in deutscher bersetzung. Wiesbaden,

1963.

Hejcl, J.: Das alttestamentliche Zinsverbot im Lichte der ethnologischen Jurisprudenz sowie des

altorientalischen Zinswesens. Freiburg i.B., 1907.

Hoffmann, H.-D.: Reform und Reformen: Untersuchungen zu einem Grundthema der deutero-

nomischen Geschichtsschreibung. Zrich, 1980.

Homer, S.: A History of Interest Rates. New Brunswick New Jersey, 1977 (1963).

Klingenberg, E.: Das israelitische Zinsverbot in Torah, Misnah und Talmud. Mainz, 1977.

Kraus, F.R.: Knigliche Verfgungen in Altbabylonischer Zeit. Leiden, 1984.

Leemans, W.F.: The rate of interest in Old-Babylonian times. Revue International des Droits de

lAntiquite 5, 1950, pp.7-34.

Loewenstamm, S.E.: Nsk and m/tarbit. Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 88, 1969, pp.51-

54.

Matthews, V.H. and D.C. Benjamin: Old Testament parallels: Laws and stories from the ancient

Near East. New York, 1991.

Meislin, B.J. and M.L. Cohen: Backgrounds of the Biblical Law against Usury. Comperative

Studies in Society and History, Vol. 6, 1963/64, pp.250-267.

Mieroop, Marc Van De: Society and enterprise in old Babylonian Ur. Berlin, 1992.

Moser, Th. Die patristische Zinslehre und ihre Ursprnge: Vom Zinsgebot zum Wucher-verbot.

Winterthur: Schellenberg, 1998.

Moser, Th. Spending Tomorrow's Riches: Credit and Credit Markets in Ancient Near Eastern

Thought. Prepared to be presented at the 2nd Annual Conference of the European Society

for the History of Economic Thought (ESHET) 1998 in Bologna, 27 February - 1 March,

1997.

Nelson, B.: The Idea of Usury: From Tribal Brotherhood to Universal Otherhood. Chicago and

London, 1949.

Neufeld, E.: The prohibition against loans at interest in ancient Hebrew Laws. Hebrew Union

College Annual, Vol. 26, 1955, pp.355-412.

Perlitt, L.: Deuteronomium-Studien. Tbingen, 1994.

San Nicol, M.: Art. Darlehen. Reallexikon der Assyriologie II. Berlin und Leipzig, 1938,

pp. 123-131.

Schwienhorst-Schnberger, L.: Das Bundesbuch (Ex 20,22-23,33). Studien zu seiner Entste-

hung und Theologie. Berlin, New York, 1990.

Silver, M.: Prophets and Markets: The Political Economy of Ancient Israel. Boston etc., 1983

Smend, R.: Die Entstehung des Alten Testaments. 4. Aufl. Stuttgart etc., 1989.

Soss, N.M.: Old Testament Law and Economic Society. Journal of the History of Ideas. Vol.

34, 1973, pp.323-344.

- 9 -

Stein, S.: The laws on interest in the Old Testament. Journal of Theological Studies, N.S. 4,

1953, pp.161-170.

Zettler, R.L.: The Ur III Temple of Inanna at Nipur: The Operation and Organization of Urban

Religious Institutions in Mesopotamia in the Late Third Millennium B.C.. Berlin, 1992.

Você também pode gostar

- Taeusch C.-History of UsuryDocumento29 páginasTaeusch C.-History of UsuryRaicea Ionut GabrielAinda não há avaliações

- Comparing Islamic and Christian Understanding of UsuryDocumento18 páginasComparing Islamic and Christian Understanding of UsuryRh2223dbAinda não há avaliações

- The Unconstitutionality of Slavery (Complete Edition): Volume 1 & 2No EverandThe Unconstitutionality of Slavery (Complete Edition): Volume 1 & 2Ainda não há avaliações

- Land of Oppression Instead of Land of OpportunityNo EverandLand of Oppression Instead of Land of OpportunityAinda não há avaliações

- A New Banking System: The Needful Capital for Rebuilding the Burnt DistrictNo EverandA New Banking System: The Needful Capital for Rebuilding the Burnt DistrictAinda não há avaliações

- Human Rights: Human Rights Are Commonly Understood As "Inalienable FundamentalDocumento37 páginasHuman Rights: Human Rights Are Commonly Understood As "Inalienable FundamentalgloomyeveningAinda não há avaliações

- Submission 27 - David Roy PackhamDocumento16 páginasSubmission 27 - David Roy Packhamaussienewsviews5302Ainda não há avaliações

- The Delegates of 1849: Life Stories of the Originators of California's Reputation as a Bold and Independent StateNo EverandThe Delegates of 1849: Life Stories of the Originators of California's Reputation as a Bold and Independent StateAinda não há avaliações

- THE DEMOCRACY AMENDMENTS: How to Amend Our U.S. Constitution to Rescue Democracy For All CitizensNo EverandTHE DEMOCRACY AMENDMENTS: How to Amend Our U.S. Constitution to Rescue Democracy For All CitizensAinda não há avaliações

- TELL THE TRUTH AND SHAME THE DEVIL: THE UNTOLD STORY OF A PASTOR'S WIFENo EverandTELL THE TRUTH AND SHAME THE DEVIL: THE UNTOLD STORY OF A PASTOR'S WIFEAinda não há avaliações

- The Louisiana Mayor’S Court: An Overview and Its Constitutional ProblemsNo EverandThe Louisiana Mayor’S Court: An Overview and Its Constitutional ProblemsAinda não há avaliações

- Liberty and Research and Development: Science Funding in a Free SocietyNo EverandLiberty and Research and Development: Science Funding in a Free SocietyAinda não há avaliações

- All Human Are Not EqualDocumento3 páginasAll Human Are Not EqualRareș Gafton100% (1)

- The Conflict between Private Monopoly and Good CitizenshipNo EverandThe Conflict between Private Monopoly and Good CitizenshipAinda não há avaliações

- What Is MoneyDocumento19 páginasWhat Is MoneyBill McNallyAinda não há avaliações

- THE STATE OF THE REPUBLIC: How the misadventures of U.S. policy since WWII have led to the quagmire of today's economic, social and political disappointments.No EverandTHE STATE OF THE REPUBLIC: How the misadventures of U.S. policy since WWII have led to the quagmire of today's economic, social and political disappointments.Ainda não há avaliações

- U.S. Copyright Renewals, 1960 July - DecemberNo EverandU.S. Copyright Renewals, 1960 July - DecemberAinda não há avaliações

- Conquest of Poverty (1933) Gerald Grattan McGeerDocumento236 páginasConquest of Poverty (1933) Gerald Grattan McGeerDaniel ThompsonAinda não há avaliações

- Hufschmid, Eric - Painful QuestionsDocumento14 páginasHufschmid, Eric - Painful QuestionsRicardo100% (1)

- Certanity of Subject Matter FINALDocumento3 páginasCertanity of Subject Matter FINALshahmiran99Ainda não há avaliações

- Albert Jay NockDocumento10 páginasAlbert Jay NockDenis CardosoAinda não há avaliações

- Geenva ConventionsDocumento13 páginasGeenva Conventionsnajeebcr9Ainda não há avaliações

- Hegel Branch, Ethel L. Chandler and Donald Chandler v. James S. Steph, Trustee, Chickasaw Lumber Company of Duncan, Oklahoma, Inc., 389 F.2d 233, 10th Cir. (1968)Documento4 páginasHegel Branch, Ethel L. Chandler and Donald Chandler v. James S. Steph, Trustee, Chickasaw Lumber Company of Duncan, Oklahoma, Inc., 389 F.2d 233, 10th Cir. (1968)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Sheldon Emry God's Bible Law On Military Draft and WarfareDocumento12 páginasSheldon Emry God's Bible Law On Military Draft and WarfarethetruththewholetruthandnothingbutthetruthAinda não há avaliações

- Tacitus As A Witness To JesusDocumento4 páginasTacitus As A Witness To JesusAlex BenetsAinda não há avaliações

- 1100-1200 History of The Catholic ChurchDocumento74 páginas1100-1200 History of The Catholic ChurchShawn ArevaloAinda não há avaliações

- Marlou Schrover, Deirdre M. Moloney (Eds)Documento273 páginasMarlou Schrover, Deirdre M. Moloney (Eds)jjjAinda não há avaliações

- Money: Research ShowcaseDocumento20 páginasMoney: Research ShowcaseJames PavurAinda não há avaliações

- 1849 1862 Statutes at Large 780-974Documento200 páginas1849 1862 Statutes at Large 780-974ncwazzyAinda não há avaliações

- Speech by DavynDocumento4 páginasSpeech by DavynNicole Lebrasseur100% (1)

- Fourteenth Amendment Diversity Corporation Cannot Sue Rundle v. DelawareDocumento19 páginasFourteenth Amendment Diversity Corporation Cannot Sue Rundle v. DelawareChemtrails Equals Treason100% (1)

- The Stern Gang Leader Abraham (Yair) Stern Collaborated With The Nazis During The Fulfillment of "The Final Solution"Documento2 páginasThe Stern Gang Leader Abraham (Yair) Stern Collaborated With The Nazis During The Fulfillment of "The Final Solution"hokuto5Ainda não há avaliações

- Tro RulingDocumento20 páginasTro RulingNBC MontanaAinda não há avaliações

- The Pseudoscience of EconomicsDocumento30 páginasThe Pseudoscience of EconomicsPeter LapsanskyAinda não há avaliações

- If Not Silver, What? by Bookwalter, John W.Documento48 páginasIf Not Silver, What? by Bookwalter, John W.Gutenberg.org100% (1)

- Ivermectin-The Global Scam1Documento8 páginasIvermectin-The Global Scam1job.cndAinda não há avaliações

- Heraclitus Fragments FinalDocumento25 páginasHeraclitus Fragments FinalAdrián PaúlAinda não há avaliações

- Lieber Series: Rancis Ieber Ontributions To Olitical CienceDocumento14 páginasLieber Series: Rancis Ieber Ontributions To Olitical CienceCrizziaAinda não há avaliações

- Road Back To Sound MoneyDocumento1 páginaRoad Back To Sound MoneyCarl MullanAinda não há avaliações

- Letter of DisassociationDocumento7 páginasLetter of DisassociationDon HuntAinda não há avaliações

- Vickers Thesis 2016Documento56 páginasVickers Thesis 2016Yasir SamiAinda não há avaliações

- Set Rockman - Slavery and CapitalismDocumento16 páginasSet Rockman - Slavery and CapitalismhgdltAinda não há avaliações

- Taking Imaginary Money As Real Money Is Seriously WrongDocumento6 páginasTaking Imaginary Money As Real Money Is Seriously WrongTy Chan100% (1)

- Magna CartaDocumento5 páginasMagna CartaMichael JonesAinda não há avaliações

- ThestampactDocumento3 páginasThestampactapi-355864571Ainda não há avaliações

- America Is A Bible LandDocumento8 páginasAmerica Is A Bible LandMJAinda não há avaliações

- English Grammar in A Nutshell: I. The Parts of SpeechDocumento4 páginasEnglish Grammar in A Nutshell: I. The Parts of SpeechRobert SirbuAinda não há avaliações

- Democracy or RepubicDocumento8 páginasDemocracy or RepubicSherwan R ShalAinda não há avaliações

- Let Us Live Not As FoolsDocumento3 páginasLet Us Live Not As FoolsCarlos Antonio P. PaladAinda não há avaliações

- Clogging The Equity of Redemption: An Outmoded Concept?: L W B DDocumento18 páginasClogging The Equity of Redemption: An Outmoded Concept?: L W B Dadvopreethi100% (1)

- SyllabusDocumento16 páginasSyllabusnokchareeAinda não há avaliações

- Frank M. Walker Why The Protestant Reformation Failed!Documento8 páginasFrank M. Walker Why The Protestant Reformation Failed!thetruththewholetruthandnothingbutthetruthAinda não há avaliações

- Tamez - Galatains - Case Study in FreedomDocumento8 páginasTamez - Galatains - Case Study in FreedomRyan HayesAinda não há avaliações

- Freedom and Law in Galatians!!Documento13 páginasFreedom and Law in Galatians!!Ryan Hayes100% (1)

- Diogenes Allen-Paradox of Freedom and AuthorityDocumento10 páginasDiogenes Allen-Paradox of Freedom and AuthorityRyan HayesAinda não há avaliações

- Hegel in Bonhoeffers SC PDFDocumento13 páginasHegel in Bonhoeffers SC PDFRyan HayesAinda não há avaliações

- Macintyre, Aquinas, PoliticsDocumento28 páginasMacintyre, Aquinas, PoliticsRyan Hayes100% (1)

- Free Yet Enslaved!Documento6 páginasFree Yet Enslaved!Ryan HayesAinda não há avaliações

- Scholastic EconomicsDocumento31 páginasScholastic EconomicsRyan HayesAinda não há avaliações

- Blomberg-Neither Capitalism Nor Socialism!Documento19 páginasBlomberg-Neither Capitalism Nor Socialism!Ryan HayesAinda não há avaliações

- Eberhard Bethge - Interpreter of BonhoefferDocumento21 páginasEberhard Bethge - Interpreter of BonhoefferRyan HayesAinda não há avaliações

- Christus Victor in Wesleyan TheologyDocumento14 páginasChristus Victor in Wesleyan TheologyRyan HayesAinda não há avaliações

- How Does Jesus SaveDocumento6 páginasHow Does Jesus SaveRyan HayesAinda não há avaliações

- Bonhoeffer's Ethics!Documento14 páginasBonhoeffer's Ethics!Ryan Hayes100% (1)

- Does America Need Barmen Declaration-StringfellowDocumento4 páginasDoes America Need Barmen Declaration-StringfellowRyan HayesAinda não há avaliações

- Authority Over Death-StringfellowDocumento4 páginasAuthority Over Death-StringfellowRyan HayesAinda não há avaliações

- Veil and Priestly Robes of Incarnation in Hebrews 10Documento14 páginasVeil and Priestly Robes of Incarnation in Hebrews 10Ryan Hayes100% (1)

- Becker's AnthropologyDocumento15 páginasBecker's AnthropologyRyan HayesAinda não há avaliações

- Heb 11 and Incarnation - MoyterDocumento14 páginasHeb 11 and Incarnation - MoyterRyan HayesAinda não há avaliações

- Liturgy As Political Event-StringfellowDocumento4 páginasLiturgy As Political Event-StringfellowRyan HayesAinda não há avaliações

- Levison's Filled With The SpiritDocumento11 páginasLevison's Filled With The SpiritRyan HayesAinda não há avaliações

- Incarnation in Hebrews!Documento16 páginasIncarnation in Hebrews!Ryan HayesAinda não há avaliações

- Esearch Ethodology: (Type Text)Documento65 páginasEsearch Ethodology: (Type Text)Majeed MujawarAinda não há avaliações

- Small Industries Service Institute: Details of Major Extension Services Provided in The Institute Are Given BelowDocumento5 páginasSmall Industries Service Institute: Details of Major Extension Services Provided in The Institute Are Given BelowMểểŕá PáńćhálAinda não há avaliações

- Subprime Mortgage CrisisDocumento35 páginasSubprime Mortgage CrisisVineet GuptaAinda não há avaliações

- Financial Analysis of Everest BankDocumento27 páginasFinancial Analysis of Everest BankSusan Kadel67% (18)

- Credit TransactionsDocumento79 páginasCredit Transactionslex libris100% (3)

- The State of Working AmericaDocumento34 páginasThe State of Working AmericaricardoczAinda não há avaliações

- Advocates of Til vs. BSPDocumento3 páginasAdvocates of Til vs. BSPIrene RamiloAinda não há avaliações

- MGEC Investor Presentation-IRDocumento17 páginasMGEC Investor Presentation-IRIbrahim IbrahimAinda não há avaliações

- Smart Contracts 12 Use Cases For Business and BeyondDocumento56 páginasSmart Contracts 12 Use Cases For Business and BeyondVuk JovinAinda não há avaliações

- Disclosure No. 376 2014 Annual Report For Fiscal Year Ended December 31 2013 SEC FORM 17 ADocumento380 páginasDisclosure No. 376 2014 Annual Report For Fiscal Year Ended December 31 2013 SEC FORM 17 ARanShibasakiAinda não há avaliações

- 5.1 FindingsDocumento9 páginas5.1 FindingsSaif Ahmed Khan RezvyAinda não há avaliações

- Account OriginationDocumento23 páginasAccount Originationsans1234Ainda não há avaliações

- Jones Electrical DistributionDocumento12 páginasJones Electrical DistributionJohnAinda não há avaliações

- 107900592009Documento88 páginas107900592009mylovedikuAinda não há avaliações

- Retail BankingDocumento11 páginasRetail Banking8095844822Ainda não há avaliações

- Function of Commercial BankDocumento4 páginasFunction of Commercial BankMohammad SaadmanAinda não há avaliações

- ACTBAS1 - Lesson 2 (Statement of Financial Position)Documento47 páginasACTBAS1 - Lesson 2 (Statement of Financial Position)AyniNuydaAinda não há avaliações

- 3 - SECTION C Forms & AppendicesDocumento52 páginas3 - SECTION C Forms & AppendicesIzzy Ferris100% (1)

- A-Exploring The Limits of Privatization-Ronald C. Moe 1987Documento9 páginasA-Exploring The Limits of Privatization-Ronald C. Moe 1987Giancarlo Palomino CamaAinda não há avaliações

- Theories of Interest RatesDocumento31 páginasTheories of Interest Rateskhan_ssAinda não há avaliações

- LAMP TermsheetDocumento4 páginasLAMP TermsheetJane JjAinda não há avaliações

- The Causal Relationship Between Financial Decisions and Their Impact On Financial PerformanceDocumento2 páginasThe Causal Relationship Between Financial Decisions and Their Impact On Financial PerformancececepAinda não há avaliações

- I AnnexureDocumento4 páginasI AnnexureRiSHI KeSH GawaIAinda não há avaliações

- Peoples Bank 2015Documento284 páginasPeoples Bank 2015Pinky PinkAinda não há avaliações

- New PM CasesDocumento15 páginasNew PM CasesChirag Nahar33% (3)

- Ruy Mauro Marini - Brazilian Interdependence and Imperialist IntegrationDocumento19 páginasRuy Mauro Marini - Brazilian Interdependence and Imperialist IntegrationMiguel Borba de SáAinda não há avaliações

- BFSI Business Analysis ProfessionalDocumento6 páginasBFSI Business Analysis ProfessionalaAinda não há avaliações

- Swot hsb4cDocumento10 páginasSwot hsb4chxm77Ainda não há avaliações

- WNS Fiscal 2014 Annual Report On Form 20-FDocumento596 páginasWNS Fiscal 2014 Annual Report On Form 20-FSaurabh ShitutAinda não há avaliações

- IL Loan Brokerage Agreement and Loan Brokerage Disclosure Statement PDFDocumento2 páginasIL Loan Brokerage Agreement and Loan Brokerage Disclosure Statement PDFJohn TurnerAinda não há avaliações