Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Australian Journal

Enviado por

Paulo RodriguesDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Australian Journal

Enviado por

Paulo RodriguesDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Australian Journal of Psychology, Vol. 62, No. 3, September 2010, pp. 169178.

Balance between volunteer work and family roles: Testing a theoretical model of workfamily conict in the volunteer emergency services

SEAN COWLISHAW, LYNETTE EVANS, & JIM MCLENNAN

School of Psychological Sciences, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Downloaded by [ ] at 06:09 14 July 2011

Abstract Trends indicate overall declines in numbers of volunteer emergency service workers and suggest negative organisational factors impacting adversely on volunteers and organisations. Conict between emergency service work and family is implicated in falling volunteer numbers, and there is thus a need for research on difculties experienced in balancing volunteer work and family. The current study tested an adaptation of the workfamily conict (WFC) model originally proposed by Frone, Russell, and Cooper, in a sample of 102 couples in which one partner was an Australian emergency service volunteer. Results supported a model in which volunteer work-related antecedents, including time invested in on-call emergency activities and post-traumatic stress symptoms, had indirect links with outcomes, including volunteer burnout and their partners support for the volunteer work role, through the effects of WFC. These results add to research using theoretical models of paid work processes to better understand the problems faced by volunteer workers, and identify specic antecedents and outcomes of WFC in the volunteer emergency services. Implications for future research and organisations reliant on volunteer workers are discussed.

Keywords: Emergency services, family issues, industrial/organisational psychology, psychology of work and unemployment, volunteer work, workfamily interface

In Western societies there is a tradition of citizens volunteering their labour to benet other people, groups, or organisations (Wilson, 2000). The Australian Bureau of Statistics (2007) estimated that in 2006, 34% of the population had engaged in some type of formal volunteering during the previous year. Although proportionally small in relation to the total number of volunteers, emergency services volunteers make an important contribution by protecting life, property, and the environment. Volunteer reghters make up the greatest proportion of these volunteers (others include rescue, coastguard, and emergency medical and ambulance volunteers), and in Australia there are approximately 221,000 re service volunteers (McLennan, 2008). Since the early 1990s, total numbers of emergency service volunteers have fallen appreciably. McLennan and Birch (2005) noted that in Australia, total volunteer-based re agency memberships declined

by approximately 30% from 1995 to 2003. Several causes of declining volunteer memberships have been identied, including broad economic and demographic factors (cf. McLennan & Birch, 2005). Studies (e.g., Lewig, Xanthopoulou, Bakker, Dollard, & Metzer, 2007), however, suggested that organisational processes important for understanding the work experiences for paid employees (e.g., job demands and resources; Bakker, Demerouti, & Verbeke, 2004) also impact on the quality of volunteer work experiences, and thus require focused investigation. Although various organisational and work processes might benet from consideration, McLennan, Birch, Cowlishaw, and Hayes (2008) reported reasons why volunteers resigned from a volunteerbased re agency and suggested the importance of conicts between reghting and volunteers family and work commitments. The scant research on this

Correspondence: Dr L. Evans, School of Psychological Sciences, La Trobe University, Kingsbury Drive, Bundoora, Vic. 3086 Australia. E-mail: l.evans@latrobe.edu.au ISSN 0004-9530 print/ISSN 1742-9536 online The Australian Psychological Society Ltd Published by Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/00049530903510765

170

S. Cowlishaw et al. The current research considered several possible antecedents of WFC associated with volunteer emergency services work, which are largely (although not entirely) unique to this type of volunteer work. They have not been extensively considered in previous literature, which has focused predominantly on generic antecedents to WFC (Byron, 2005), which are relevant across various working contexts (i.e., different occupational settings). For instance, there is evidence that hours spent at work predicts WFC (Byron, 2005), and factors related to time invested in volunteering might also precipitate interrole conict. Although data on time committed by emergency service volunteers are limited, Hayward and Tuckey (2007) studied a large sample of Australian reghters and found reports of volunteering an average of 27 hr per month during the re season (6.75 hr per week). A unique characteristic of such time demands is associated with volunteers being generally on-call to respond to emergencies, which are unpredictable and occur without notice at any time (Cowlishaw, McLennan et al., 2008). As far as can be ascertained, the effects of unpredictable oncall work, including volunteer work, have not been examined, and the current study evaluated whether investment in unpredictable emergency response activities was related to WFC. An important issue concerns the psychological processes potentially explaining why volunteers might be inclined to dedicate time in volunteering at such a level as to conict with family. Studies on paid employees have considered analogous tendencies by workers to invest inordinate time in work activities, and suggested that whether individuals are psychologically involved in their work, or report high role salience associated with the work role, may determine this behavioural investment. For instance, Greenhaus and Powell (2003) found that workers with high work role salience were more likely to chose work over family events when presented with hypothetical scenarios, while work involvement and role salience have been found to predict time spent at work (e.g., Ford et al., 2007; Lobel & St. Clair, 1992). Based on this research, it is argued here that if volunteers are psychologically involved in unpaid work roles, then this involvement may determine their investment (i.e., time) in volunteer work, and, presumably, WFC. Admittedly, such an account of how involvement relates to WFC is one among several possibilities, and work involvement may also predict WFC directly if highly involved volunteers are inclined to generally neglect their personal lives. Alternatively, involvement may relate directly and negatively to WFC if involved workers are less sensitive to interrole conict, and are less likely to report WFC. Given that studies examining links between work involvement and WFC are limited, while studies of such

issue was reviewed by Cowlishaw, Evans, and McLennan (2008), who reported indirect evidence suggesting time- and strain-based conicts between emergency service volunteering and family. In a subsequent qualitative study, Cowlishaw, McLennan, and Evans (2008) noted aspects of emergency services volunteering that were likely to impact on family life. These included aspects of the work that were unique to volunteers, such as the disruptive effects of emergencies on family routines, associated with being on-call to respond to incidents. Other noted impacts on family life, however, were consistent with pressures on the families of paid workers, and included time away from family for training and responding to emergencies, and changes in the volunteers mood and behaviour at home after attending distressing incidents. Research, however, on the workfamily lives of emergency services volunteers is otherwise lacking. The overall aim of current study was to address this lack of research, and evaluate whether conceptual accounts of the workfamily interface could be adapted to study the workfamily interactions of volunteers. Considerable theoretical literature is available concerning the interplay between paid work and family (e.g., Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985; Voydanoff, 2002), and may be useful for investigating interactions between volunteering and family. Role conict theory has been the dominant theoretical framework informing this research (Casper, Eby, Bordeaux, Lockwood, & Lambert, 2007), and is thus a logical place to begin such investigation. Work family conict (WFC) is a form of inter-role conict whereby demands from work and from family are incompatible, such that participation in one role is made difcult through participation in the other (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). Although research (e.g., Frone, Yardley, & Markel, 1997) has proposed distinct directions of WFC, namely work interference with family and family interference with work, the current study focuses on how volunteer work conicts with family, as well as the potential antecedents and outcomes of such interference. Frone, Russell, and Cooper (1992) proposed a theoretical model that specied WFC as a mediator between job-related antecedents and family outcomes. In particular, they argued that WFC acted as an intervening pathway, such that work-related variables (e.g., job stress) affected outcomes for workers (e.g., life satisfaction) through WFC. Subsequent studies (e.g., Aryee, Fields, & Luk, 1999; Major, Klein, & Ehrhart, 2002) have since yielded support for this model, variants of which have dominated the literature (Ford, Heinen, & Langkamer, 2007). Accordingly, this indirect effects model was chosen to form the basis of the current study of WFC in emergency service volunteers.

Downloaded by [ ] at 06:09 14 July 2011

Balance between volunteer work and family processes in volunteers are non-existent, the current investigation considered whether volunteers work involvement might predict WFC indirectly through investment in emergency response activities. Strain-based antecedents refer to work experiences that produce strain and interfere with functioning in family roles (Ford et al., 2007). Although research has tended to focus on generic sources of stress (e.g., role conict) (Grandey & Cropanzano, 1999), exposure to traumatic events (e.g., motor vehicle accidents) is a potentially important work stressor that characterises many occupations, including the emergency services (Beaton, Murphy, Johnson, Pike, & Corneil, 1998). Previous investigations have shown that post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) can be associated with acute stress and strain in emergency service workers (Brough, 2004), including volunteers (Bryant & Harvey, 1996). PTSS, however, may also impact on family life. In particular, investigations by Regehr (2005) and Regehr, Dimitropoulos, Bright, George, and Henderson (2005) found that the families of emergency service workers were sensitive to various difculties following traumatic incidents, such as workers being emotionally distant. The impacts of PTSS, however, have not been widely investigated in workfamily research, and the current study also considered whether such symptoms were another relatively unique antecedent of WFC for emergency service volunteers. The current research then investigated two potential outcomes from WFC. First, research on paid workers (e.g., Innstrand, Langballe, Espnes, Falkum, & Aasland, 2008) has found a large relationship between WFC and work-related burnout. Burnout, referring to experiences of fatigue and exhaustion from long-term exposure (physical and psychological) to demanding work situations (Kristensen, Borritz, Villadsen, & Christensen, 2005), is important to study because of links with outcomes such as low life satisfaction (Demerouti, Bakker, & Schaufeli, 2005) and volunteers intention to continue volunteering (Lewig et al., 2007). Such links between interrole conict and burnout in a volunteer context are currently speculative. Second, the current research also examined whether WFC was related to support for the volunteer emergency service role, as reported by the volunteers partner. Partner support has not been studied extensively in previous research, which is surprising given that social support from family is related to whether family interferes with work (van Daalen, Willemsen, & Sanders, 2006). Despite this general lack of research, Cowlishaw, McLennan et al. (2008) found evidence that demands (e.g., child care) were left with family members as a result of volunteer reghting activities, while other studies have found strained family interactions associated with WFC (e.g., Matthews, Del Priore, Acitelli, &

171

Downloaded by [ ] at 06:09 14 July 2011

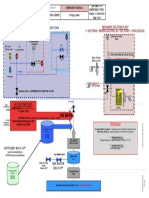

Barnes-Farrell, 2006). If family members perceive that such strains are the result of work demands, they may withdraw support for these commitments. A lack of support from family may increase pressures on the volunteer, thus also increasing their level of burnout. The current study evaluated these links between WFC and partner support, and then potential impacts of partner support on volunteer burnout. In summary, the current research evaluated a model that specied volunteer work-related antecedents predicting outcomes (mostly) through the effects of WFC. This model, which is shown in Figure 1, proposed relations among antecedents and outcomes of WFC that have not been considered in previous research (e.g., PTSS; partner support), as well as variables particularly (although not entirely) unique to volunteer emergency service work (e.g., on-call time investment). This research contributes to the literature by examining WFC in a new volunteer work context, and investigating variables related to WFC that are relatively unique to emergency service volunteer work. It should be noted from the outset that this model does not aspire to provide a comprehensive account of factors implicated in interactions between volunteer work and family (e.g., familywork conict). Rather, this study evaluated whether workfamily processes reected in accounts of WFC were similar to analogous processes by which volunteer work impacted on family life. This model was examined using data obtained from Australian emergency service volunteers and their partners, analysed using structural equation modelling (SEM).

Method Participants Participants consisted of 113 couples in whom one partner was an Australian emergency service

Figure 1. Standardised parameter estimates for the nal indirect effects model. Values in parentheses indicate parameter estimates when workfamily conict (WFC) was specied based on matched partner reports. PTSS post-traumatic stress symptoms. *p 5 .05, **p 5 .01

172

S. Cowlishaw et al. employment, the number and age of children, and general area of residence (e.g., rural farm; urban area). Workfamily conict. WFC was measured using the time- and strain-based WFC subscales (three items each) from the measure developed by Carlson, Kacmar, and Williams (2000). Each item was scored on a 5-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). In the current study, all items were adapted to (a) refer to volunteer work, and (b) capture volunteer and partner perceptions. For the partner-focused adaptations, items referred to my partners volunteering. Example items included Due to pressures at volunteering, sometimes my partner comes home too stressed to do the things he/she enjoys (partner report) and I have to miss family activities due to the amount of time I spend on responsibilities associated with my emergency service work (volunteer self-report). Items were combined to reect single dimensions for both volunteers and their partners, and internal consistency reliability was a .89 and a .88 for volunteers and their partners, respectively. Burnout. Burnout was measured using the WorkRelated Burnout subscale of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI) (Kristensen et al., 2005). This Burnout scale consists of seven items, each scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (to a very high degree) to 5 (to a very low degree), an example of which was Do you feel burnt out because of your work? All items were adapted to refer specically to volunteer work. The internal consistency reliability was a .77. Role involvement. This was measured using the veitem job involvement scale from Frone, Russell, and Cooper (1995). Items were adapted to refer to volunteering (as opposed to paid employment). An example is Some of the most important things that happen to me involve my volunteering. All items were scored on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). The internal consistency reliability was a .89. Post-traumatic stress symptoms. PTSS were measured using the Carlson (2001) 17-item Screen for Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms (SPTSS). The SPTSS items match the DSM-IV symptom criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), examples of which are: I feel cut off and isolated from other people and I get very irritable and lose my temper. A 5-point Likert scale response format was used, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (more than once every day). The SPTSS is not referenced to any

Downloaded by [ ] at 06:09 14 July 2011

volunteer. For the SEM analysis, any cases with 425% missing data were removed from the analysis listwise (Newman, 2003), while the ExpectationMaximisation (EM) algorithm was used to address missing data for the remaining cases (Enders, 2001). Accordingly, 11 couples were excluded because only one partner provided complete responses, leaving a nal sample of 102 couples. Eighty percent of these volunteers were male and 49.4 years old on average (SD 10.33). Eighty-one per cent of partners were female (with one missing value) and 47.4 years old on average (SD 10.19). Eighty-four percent of couples were married, and 10% were in de facto relationships (with some missing). Fifty-six per cent of couples had children living at home (mode 2.0 children), with ages ranging from 6 months to 35 years (M 12.6 years; SD 7.89). Sixty-two per cent of volunteers were employed full time, 17% part time, and 19% were unemployed or retired. Corresponding gures for partners were 40% full time, 31% part time, and 28% with no employment (with some missing). Thirty-three per cent of couples lived on rural properties, 40% in rural towns, 13% in urban areas, and 7% in provincial cities. Volunteers were reghters (89%), ambulance ofcers (7%) or emergency rescue volunteers (4%). These participants had been with their volunteer organisation for 18.8 years on average (SD 13.63); and reported volunteering, on average, 12.4 hr per week (SD 13.37). Procedure Invitations to participate were made to couples through stories in the general media and advertisements placed in the internal publications of cooperating emergency service agencies. These advertisements described the study and ways of taking part, including contacting the researchers via a free-call message service, or printing materials from a secure website. Questionnaire packages consisted of a covering letter and separate questionnaire forms (with reply-paid envelopes) for volunteers and their partners, and most were mailed to couples who registered interest via the message service. All questionnaires were anonymous and returned in separate reply-paid envelopes. If both partners were emergency service volunteers, the partner who volunteered most often was asked to complete the volunteer form, and all couples were asked to place an identifying code on questionnaires to match returns from both partners. Measures Initial sections of the questionnaire collected data on demographic variables, including age, type of paid

Balance between volunteer work and family specic traumatic event and thus measures symptom frequency following exposure to single, multiple, or no traumatic events (Carlson, 2001). Available studies have reported good reliability for this scale and high correlations with both self-report (e.g., r .79) and clinician administered (e.g., r .68) PTSD measures (Carlson, 2001; Caspi, Carlson, & Klein, 2007). The internal consistency reliability in this study was a .89. Partner support. Partner support for the volunteers emergency service commitments was operationalised using the single item Overall, how much would you like your partner to either continue or give up his/her volunteering?, answered directly by the volunteers partner on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (give up volunteering very much) to 5 (very much continue volunteering). This item correlated r .57 with partner responses on a visual analog scale indicating how happy they were with their partner being an emergency service volunteer.

173

On-call volunteer time investment. This was operationalised using volunteer responses to the single item During the busiest month of the past year, around how many incidents/jobs did you attend? This item had an open response format. Preliminary data screening indicated that this item was skewed and, as such, was transformed prior to analysis. Data analysis Descriptive statistics were calculated using SPSS. Independent group t tests and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were also conducted to examine potential differences in outcomes across background variables. Matched data from both partners were then analysed using the AMOS 16 SEM program. Maximum likelihood (ML) estimation was used to estimate the proposed model. Statistical indices were examined to evaluate the overall ability of the proposed model to account for the data. The chisquare statistic was the primary index used to evaluate model t, and a non-signicant value indicates a well-tting model. The BollenStine (1992) bootstrap p was calculated to compensate for biases in the chi-square estimate associated with multivariate non-normal data. Several approximate t indices were also examined, including the conrmatory t index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR). Criteria for evaluating model t based on Hu and Bentler (1999) were used, including CFI 4 .95; RMSEA 5 .06; and SRMR 5 .08. Assuming adequate overall t, the proposed model was then compared against plausible alternative models (cf. Tomarken & Waller, 2003).

Given that these models were not hierarchically nested, comparison was through examination of predictive t indices, including the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayes information criterion (BIC). Models with lower values on the AIC and BIC are preferred over models with higher values (cf. Kline, 2005). Several strategies were used to examine and control for measurement error in structural parameter estimates. First, most variables were specied as single-indicator latent variables. When multi-item measurement scales were used, internal consistency estimates were used to account for random measurement error (McDonald, Behson, & Seifert, 2005) using the formulas provided by Munck (1979). This technique requires fewer estimated parameters than multiple indicator models, but yields structural parameter estimates controlling for measurement error (Sass & Smith, 2006). Principal components analyses for each scale suggested sufcient unidimensionality to support item parcelling (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002). When single items were the only measures available, latent variables were specied by this single indicator with a regression weight of 1.0 and an error variance of zero. Second, to examine for effects of systematic measurement error (e.g., reporting biases), the nal model was re-estimated, but with the key variable of interest (WFC) specied as a latent variable using matched reports from both members of a couple (cf. Cook & Goldstein, 1993). This approach controls for biases in both partners reports (Cook & Kenny, 2006) and overcomes a limitation associated with relying on worker self-report data (Casper et al., 2007). Structural parameters were compared across models to examine for any discrepancies, presumably indicating systematic measurement error.

Downloaded by [ ] at 06:09 14 July 2011

Results Descriptive statistics Means, standard deviations, and correlations are listed in Table I. Variable means and standard deviations were obtained by summing scale items, and are supplied for descriptive purposes. As can be seen from Table I, volunteer and partner reports of WFC were moderately and positively correlated. WFC also correlated in expected directions with PTSS, on-call time investment, partner support, and burnout. Results from independent groups t tests and ANOVA (both Bonferroni adjusted) indicated no signicant differences in model variables according to employment status (full-time employed compared to part-time/unemployed), area of residence (rural properties, small rural towns, or densely populated areas), or number of children at home.

174

S. Cowlishaw et al.

Table I. Major variables Correlations Variable 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. WFC self-report WFC partner report Burnout Work role involvement PTSS Partner support On-call time investment M 15.10 16.17 15.35 18.16 22.83 4.30 11.87 SD 4.18 5.27 4.08 4.18 6.40 1.04 9.59 a .89 .88 .77 .89 .89 1 .52** .65** .19 .33** 7.31** .31** 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

.37** .07 .21* 7.43** .18

.12 .39** .41** .17

.21* 7.01 .20*

7.08 .27**

7.08

Notes. PTSS post-traumatic stress symptoms; WFC workfamily conict. *p 5 .05, **p 5 .01. Table II. Goodness-of-t indices for the proposed structural equation models

Model testing

Model

w2 108.16 8.65 19.21

df 15 7 11

pa .000 .943 .464

CFI .00 .98 .94

RMSEA .25 .05 .09

SRMR .06 .07

Table II presents t indices for estimated models. As can be seen, the proposed indirect effects model provided good t to the data, as reected in a non-signicant chi-square and approximate t indices within desired ranges. To further evaluate the adequacy of this model, alternative models were generated for comparative purposes (details on the specication and t of these can be obtained from the corresponding author). Two alternative models were theoretically plausible (e.g., with WFC specied as an exogenous variable), while another specied variance among variables as attributable to correlated reports of burnout and PTSS. While results suggested marginal or acceptable overall t for these alternatives, the proposed model was preferred according to the AIC and BIC, supporting the indirect effects model as a plausible representation of the data. Standardised parameter estimates for this model are shown in Figure 1. As seen in Figure 1, work involvement was a signicant predictor of on-call time investment (accounting for 5% of the variance). Time investment then signicantly predicted WFC. PTSS also had a positive effect on WFC, as well as a direct inuence on burnout. The model accounted for 16% of the variance in WFC. Parameter estimates then indicated that WFC had a large positive effect on burnout, and a moderate and negative effect on partner support. The pathway between partner support and volunteer burnout, however, was not signicant. Overall, this model accounted for 10% of the variance in partner support, and 65% if the variance in burnout. Finally, also shown in Figure 1, this indirect effects model was re-estimated, but with WFC specied using matched reports from volunteers and their partners. This model (indirect effectsb in Table II) yielded similar parameter estimates (in parentheses) to the original model using self-report data only.

Independence Indirect effects Indirect effectsb

Downloaded by [ ] at 06:09 14 July 2011

Notes. CFI conrmatory t index; RMSEA root mean square error of approximation; SRMR standardised root mean square residual. a BollenStine (1992) bootstrap p. b Model with workfamily conict specied using matched reports from both partners.

Discussion The current research contributes to the existing literature in several ways. Results indicate that an indirect effects model, with work-related antecedents specied to predict outcomes through WFC, was a plausible representation of data reported by volunteer emergency service workers and their partners. Previous studies (e.g., Frone et al., 1992) have focused exclusively on conicts between paid work and family, and the current research extends this literature to an unpaid volunteer context. The current study also advances literature on the antecedents and outcomes of WFC. The strong positive pathway from WFC to volunteer burnout was consistent with studies of paid workers (e.g., Demerouti, Bakker, & Bulters, 2004), and suggests that WFC is also a source of burnout for volunteers. Other proposed antecedents and outcomes, however, have not been considered extensively in previous research, which has focused predominantly on generic variables seemingly relevant across different work contexts. As such, the current study makes additional contributions to the literature by examining unique variables relating to WFC for emergency service volunteers. This investigation provided notable ndings concerning the antecedents of WFC. First, inter-role conict was positively predicted by volunteer reports

Balance between volunteer work and family of time spent in on-call emergency service activities. This is consistent with reported relationships between the scheduling of work activities and paid WFC (Byron, 2005; Hammer, Allen, & Grigsby, 1997). The impacts of on-call work demands, however, such as volunteer response to emergencies, have not been examined in previous literature. As such, the current results suggest that on-call demands, presumably associated with unpredictable interruptions to family life, were another source of WFC. Second, volunteers level of psychological work involvement predicted higher levels of time in emergency activities, supporting the proposed indirect link with WFC through time investment. This is consistent with previous results indicating that work involvement predicts time spent on paid work (Ford et al., 2007), and suggests that individuals can also be highly involved in a volunteer work role. Although evidence on the personal value of volunteering is limited, functional approaches to volunteer work (e.g., Clary et al., 1998; Snyder, Clary, & Stukas, 2000) indicate that volunteers have their own salient psychological motives for volunteering (e.g., ego enhancement, social engagement). The present study suggests that involvement in volunteer work impacts on the level of time and energy devoted to role responsibilities, but at a cost of interference with family activities. The current results indicated that PTSS were also related to WFC. Few previous studies have considered links between inter-role conict and sources of stress unique to particular working contexts. As far as can be ascertained, none have examined PTSS. In a supplementary analysis of a checklist assessing exposure to traumatic events, volunteers reported a range of distressing incidents, including attending motor vehicle accidents (80%); incidents involving death of a victim (66%); and threat of death or serious personal injury (40%). Studies on family functioning in the context of war-related trauma (e.g., Goff, Crow, Reisbig, & Hamilton, 2007) may be relevant here, and have documented impacts of PTSD on family life. This clinical literature suggests that such adverse impacts on families may occur, in part, through symptoms of avoidance and emotional numbing (Evans, McHugh, Hopwood, & Watt, 2003). Although few participants in the current study indicated such elevated levels of PTSS, studies of emergency service workers (e.g., Regehr et al., 2005) have also illustrated emotional and social withdrawal from families after attending distressing emergencies. Such subthreshold symptoms of posttraumatic stress (Breslau, Lucia, & Davis, 2004) may be relatively common in emergency service workers, and may contribute to WFC. A nal notable nding concerned the pathway between WFC and partner support for emergency

175

volunteering. Although partner support for work has not been considered extensively, literature on stress cross-over (Westman, 2001) indicates that work experiences do impact on family members, who thus have reactions to work events. As such, the current research supported the notion that interference in family activities from volunteer work would predict less support from the partner for the volunteers participation in emergency services work. What are less clear, however, are the likely consequences of such low support. An expected pathway from partner support to volunteer burnout was not found, suggesting that low support did not immediately impact on volunteers work-related strain. But this nding may be attributable to a limitation of the measure used to operationalise partner support (i.e., a single item indicator). In particular, partner reports of support may bear little correspondence to how such support is actually expressed through behaviour. Alternatively, studies indicate that a lack of family support can affect the workers ability to satisfy work demands, although it does so through familywork conict (van Daalen et al., 2006). As such, it is possible that partner support does impact on worker outcomes that are not necessarily related to burnout (e.g., work performance), and may do so through variables not evaluated in the current study. The ndings of this research should be considered in light of methodological limitations. First, this study could not measure all variables implicated in conicts between volunteer work and family. For instance, although variables associated with paid work may also impact on volunteer work and family, data on these were not available because of volunteer agency sensitivities about what questions they were prepared to have asked of their members. As such, future research is required to examine a larger range of variables, and potentially address other salient workfamily issues unique to volunteer workers (e.g., the simultaneous interactions between work, volunteering, and family demands). Also, data were collected on a single occasion and the current study provides only tentative evidence for the causal ordering of variables. For instance, although this study concluded that time demands predicted WFC, the reverse is also plausible: WFC may predict higher time demands if volunteers invest in volunteering to avoid existing difculties at home. Given that alternative explanations cannot be ruled out based on correlational data, the current conclusions must be considered tentative. The available sample size also precluded specication of more complex statistical models; it was not possible to simultaneously examine time- and strain-based forms of WFC, or evaluate whether the model explained more variance in outcomes for volunteers with or without parenting responsibilities. Finally, specic measures, such as

Downloaded by [ ] at 06:09 14 July 2011

176

S. Cowlishaw et al. Acknowledgements The research was conducted for the degree of PhD at La Trobe University, supported by a Scholarship awarded by the Bushre Cooperative Research Centre.

time invested in on-call work and partner support, were measured using single items only. These limitations, however, were partly offset by methodological strengths, including matched data obtained from both members of a couple that minimised the effects of systematic measurement error. As one reviewer noted, there are many other ways that such matched data could be used (e.g., to examine discrepancies between worker and partner perceptions of WFC), suggesting scope for additional research on partner reports of, and outcomes from, inter-role conict (Bakker, Demerouti, & Dollard, 2008). Conclusions Consistent with limited research applying accounts of paid work processes in volunteer samples (e.g., Lewig et al., 2007), the current investigation indicated that a model of WFC could inform understanding of difculties experienced by emergency service volunteers and their partners. The current study appears to be the rst to consider such workfamily issues in a volunteer context, and highlights the utility of theoretical models developed in the context of paid work to inform on volunteer issues. It also illustrates some of the difculties facing volunteers, their families and organisations. The current study thus has practical implications for organisations. It suggests that volunteer-based emergency services organisations will benet from strategies to reduce WFC. First, organisations should be sensitive to the implications for family from volunteer reactions to traumatic stress. Emergency service agencies frequently implement post-incident support programs for workers following distressing events. Although evidence on the benets of such programs for the individual is equivocal (Devily, Gist, & Cotton, 2006), such services could be expanded to incorporate components aimed at reducing impacts on family (e.g., by providing psychoeducation for partners). Second, WFC was related to volunteers work involvement, indicating that workers with interests overly focused around their volunteering may be at greater risk of WFC. Organisations should consider educating their volunteers on ways to achieve a sustainable balance among volunteering, paid work, and family roles. Informal support from supervisors is a factor helping workers balance work and family (Anderson, Coffey, & Byerly, 2002), and guidance from volunteer managers to help volunteers prioritise family needs could be an initial way to reduce WFC. Multiple strategies for supporting volunteers and their families, however, will likely be necessary to bring about lasting reductions in WFC, and change organisational culture such that family needs are given increased priority.

References

Anderson, S. E., Coffey, B. S., & Byerly, R. T. (2002). Formal organizational initiatives and informal workplace practices: Links to work-family conict and job-related outcomes. Journal of Management, 28, 787810. Aryee, S., Fields, D., & Luk, V. (1999). A cross-cultural test of a model of the work-family interface. Journal of Management, 25, 491511. Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2007). Voluntary work Australia (No. 4441.0). Canberra: Australian Capital Territory. Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Dollard, M. F. (2008). How job demands affect partners experience of exhaustion: Integrating work-family conict and crossover theory. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 901911. Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Verbeke, W. (2004). Using the job demands-resources model to predict burnout and performance. Human Resource Management, 43, 83104. Beaton, R., Murphy, S., Johnson, C., Pike, K., & Corneil, W. (1998). Exposure to duty-related incident stressors in urban reghters and paramedics. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 11, 821828. Bollen, K. A., & Stine, R. A. (1992). Bootstrapping goodness-oft measures in structural equation models. Sociological Methods and Research, 21, 205229. Breslau, N., Lucia, V. C., & Davis, G. C. (2004). Partial PTSD versus full PTSD: An empirical examination of associated impairment. Psychological Medicine, 34, 12051214. Brough, P. (2004). Comparing the inuence of traumatic and organizational stressors on the psychological health of police, re, and ambulance ofcers. International Journal of Stress Management, 11, 227244. Bryant, R. A., & Harvey, A. G. (1996). Posttraumatic stress reactions in volunteer reghters. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9, 5162. Byron, K. (2005). A meta-analytic review of work-family conict and its antecedents. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67, 169 198. Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., & Williams, L. J. (2000). Construction and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of work-family conict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 56, 249276. Carlson, E. B. (2001). Psychometric study of a brief screen for PTSD: Assessing the impact of multiple traumatic events. Assessment, 8, 431441. Casper, W. J., Eby, L. T., Bordeaux, C., Lockwood, A., & Lambert, D. (2007). A review of research methods IO/OB work-family research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 2843. Caspi, Y., Carlson, E. B., & Klein, E. (2007). Validation of a screening instrument for posttraumatic stress disorder in a community sample of Bedouin men serving in the Israeli Defense Forces. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20, 517527. Clary, E. G., Snyder, M., Ridge, R. D., Copeland, J., Stukas, A. A., Haugen, J., et al. (1998). Understanding and assessing the motivations of volunteers: A functional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 15161530. Cook, W. L., & Goldstein, M. J. (1993). Multiple perspectives on family relationships: A latent variables model. Child Development, 64, 13771388.

Downloaded by [ ] at 06:09 14 July 2011

Balance between volunteer work and family

Cook, W. L., & Kenny, D. A. (2006). Examining the validity of self-report assessments of family functioning: A question of the level of analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 20, 209 216. Cowlishaw, S., Evans, L., & McLennan, J. (2008). Families of rural volunteer reghters. Rural Society, 18, 1725. Cowlishaw, S., McLennan, J., & Evans, L. (2008). Volunteer reghting and family life: An organisational perspective on conicts between volunteer and family roles. Australian Journal on Volunteering, 13, 2131. Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., & Bulters, A. J. (2004). The loss spiral of work pressure, work-home interference and exhaustion: Reciprocal relations in a three-wave study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64, 131149. Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2005). Spillover and crossover of exhaustion and life satisfaction among dual earner parents. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67, 266289. Devily, G. J., Gist, R., & Cotton, C. (2006). Ready! Fire! Aim! The status of psychological debrieng and therapeutic interventions: In the work place and after disasters. Review of General Psychology, 10, 318345. Enders, C. K. (2001). A primer on maximum likelihood algorithms available for use with missing data. Structural Equation Modeling, 8, 128141. Evans, L., McHugh, T., Hopwood, M., & Watt, C. (2003). Chronic posttraumatic stress disorder and family functioning of Vietnam veterans and their partners. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 37, 765772. Ford, M. T., Heinen, B. A., & Langkamer, K. L. (2007). Work and family satisfaction and conict: A meta-analysis of crossdomain relations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 5780. Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. L. (1992). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conict: Testing a model of the work-family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, 65 78. Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. L. (1995). Job stressors, job involvement and employee health: A test of identity theory. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 68, 111. Frone, M. R., Yardley, J. K., & Markel, K. S. (1997). Developing and testing an integrative model of the work-family interface. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 50, 145167. Goff, B. S., Crow, J. R., Reisbig, A., & Hamilton, S. (2007). The impact of individual trauma symptoms of deployed soldiers on relationship satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 344 353. Grandey, A. A., & Cropanzano, R. (1999). The conservation of resources model applied to work-family conict and strain. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54, 350370. Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10, 7688. Greenhaus, J. H., & Powell, G. N. (2003). When work and family collide: Deciding between competing role demands. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 90, 291 303. Hammer, L. B., Allen, E., & Grigsby, T. D. (1997). Work-family conict in dual-earner couples: Within-individual and crossover effects of work and family. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 50, 185203. Hayward, R., & Tuckey, M. R. (2007, September). Well-being in volunteer re-ghters: Moving beyond critical incidents to examine the role of emotional demands and resources, in particular camaraderie. Paper presented at the 7th Industrial and Organisational Psychology Conference, Adelaide Convention Centre, South Australia, Australia. Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for t indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 155.

177

Innstrand, S. T., Langballe, E. M., Espnes, G. A., Falkum, E., & Aasland, O. G. (2008). Positive and negative work-family interaction and burnout: A longitudinal study of reciprocal relations. Work and Stress, 22, 115. Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press. Kristensen, T. S., Borritz, M., Villadsen, E., & Christensen, K. B. (2005). The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work and Stress, 19, 192 207. Lewig, K. A., Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Dollard, M. F., & Metzer, J. C. (2007). Burnout and connectedness among Australian volunteers: A test of the job demandsresources model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 71, 429 445. Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 151173. Lobel, S. A., & St. Clair, L. (1992). Effects of family responsibilities, gender, and career identity salience on performance outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 352, 10571069. Major, V. S., Klein, K. J., & Ehrhart, M. G. (2002). Work time, work interference with family, and psychological distress. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 427436. Matthews, R. A., Del Priore, R. E., Acitelli, L. K., & BarnesFarrell, J. L. (2006). Work-to-relationship conict: Crossover effects in dual-earner couples. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11, 228240. McDonald, R. A., Behson, S. J., & Seifert, C. F. (2005). Strategies for dealing with measurement error in multiple regression. Journal of Academy of Business and Economics, 3, 8097. McLennan, J. (2008). Issues facing Australian volunteer-based emergency services organisations 20082010. Melbourne: School of Psychological Science, La Trobe University. McLennan, J., & Birch, A. (2005). A potential crisis in wildre emergency response capability? Australias volunteer reghters. Environmental Hazards, 6, 101107. McLennan, J., Birch, A., Cowlishaw, S., & Hayes, P. (2008). I quit! Leadership and satisfaction with the volunteer role: Resignations and organisational responses. In Proceedings of the 43rd Annual Conference of the Australian Psychological Society (pp. 214218). Adelaide: Australian Psychological Society. Munck, I. M. (1979). Model building in comparative education: Applications of the LISREL methods to cross-national survey data. International Association for the Evaluation Achievement Monograph Series No. 10. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell. Newman, D. A. (2003). Longitudinal modeling with randomly and systematically missing data: A simulation of ad hoc, maximum likelihood, and multiple imputation techniques. Organizational Research Methods, 6, 328362. Regehr, C. (2005). Bringing the trauma home: Spouses of paramedics. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 10, 97114. Regehr, C., Dimitropoulos, G., Bright, E., George, S., & Henderson, J. (2005). Behind the brotherhood: Rewards and challenges for wives of reghters. Family Relations: Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies, 54, 423435. Sass, D. A., & Smith, P. L. (2006). The effects of parceling unidimensional scales on structural parameter estimates in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 13, 566586. Snyder, M., Clary, E. G., & Stukas, A. A. (2000). The functional approach to volunteerism. In G. R. Maio, & J. M. Olson (Eds.), Why we evaluate: Functions of attitudes (pp. 365393). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Downloaded by [ ] at 06:09 14 July 2011

178

S. Cowlishaw et al.

Voydanoff, P. (2002). Linkages between the work-family interface and work, family, and individual outcomes: An integrative model. Journal of Family Issues, 23, 138164. Westman, M. (2001). Stress and strain crossover. Human Relations, 54, 717752. Wilson, J. (2000). Volunteering. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 215240.

Tomarken, A. J., & Waller, N. G. (2003). Potential problems with well tting models. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 578598. van Daalen, G., Willemsen, T. M., & Sanders, K. (2006). Reducing work-family conict through different sources of social support. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69, 462 476.

Downloaded by [ ] at 06:09 14 July 2011

Você também pode gostar

- OVERTOURISM Definition and ImpactDocumento6 páginasOVERTOURISM Definition and ImpactPaulo RodriguesAinda não há avaliações

- Audi TT Roadster MK1 QuickReferenceGuide PDFDocumento4 páginasAudi TT Roadster MK1 QuickReferenceGuide PDFPaulo RodriguesAinda não há avaliações

- Consumer Culture and Post Modernism Mike FetherstoneDocumento16 páginasConsumer Culture and Post Modernism Mike FetherstonePaulo RodriguesAinda não há avaliações

- The Post Modern Transition Law and Politics BSSDocumento68 páginasThe Post Modern Transition Law and Politics BSSPaulo RodriguesAinda não há avaliações

- The Post Modern Transition Law and Politics BSSDocumento68 páginasThe Post Modern Transition Law and Politics BSSPaulo RodriguesAinda não há avaliações

- As LuzesDocumento4 páginasAs LuzesPaulo RodriguesAinda não há avaliações

- Room For Manoeuver BSSDocumento28 páginasRoom For Manoeuver BSSPaulo RodriguesAinda não há avaliações

- The Evolution of Understanding NeighborsDocumento5 páginasThe Evolution of Understanding NeighborsPaulo RodriguesAinda não há avaliações

- State Wage Relations and Social Welfare The Case of Portugal BSSDocumento54 páginasState Wage Relations and Social Welfare The Case of Portugal BSSPaulo RodriguesAinda não há avaliações

- Room For Manoeuver BSSDocumento28 páginasRoom For Manoeuver BSSPaulo RodriguesAinda não há avaliações

- A History of Social Welfare and Social WorkDocumento53 páginasA History of Social Welfare and Social WorkPaulo RodriguesAinda não há avaliações

- Citing References Harvard System PDFDocumento8 páginasCiting References Harvard System PDFPaulo RodriguesAinda não há avaliações

- The Post Modern Transition Law and Politics BSSDocumento68 páginasThe Post Modern Transition Law and Politics BSSPaulo RodriguesAinda não há avaliações

- Cultura Popular e Ideologia Estatal EEDocumento26 páginasCultura Popular e Ideologia Estatal EEPaulo RodriguesAinda não há avaliações

- Taylor Is MoDocumento15 páginasTaylor Is MoPaulo RodriguesAinda não há avaliações

- (Architecture-eBook) (Japanese) TEN HOUSES 06Documento145 páginas(Architecture-eBook) (Japanese) TEN HOUSES 06Paulo RodriguesAinda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- B361-08 Standard Specification For Factory-Made Wrought Aluminum and Aluminum-Alloy Welding FittingsDocumento6 páginasB361-08 Standard Specification For Factory-Made Wrought Aluminum and Aluminum-Alloy Welding FittingsmithileshAinda não há avaliações

- Different Types of AstrologyDocumento16 páginasDifferent Types of AstrologyastrologerrajeevjiAinda não há avaliações

- 1000 Plus Psychiatry MCQ Book DranilkakunjeDocumento141 páginas1000 Plus Psychiatry MCQ Book Dranilkakunjethelegend 20220% (1)

- CSR FinalDocumento44 páginasCSR FinalrohanAinda não há avaliações

- Emergency procedures for shipboard fire suppression systemsDocumento1 páginaEmergency procedures for shipboard fire suppression systemsImmorthalAinda não há avaliações

- Mrs Jenny obstetric historyDocumento3 páginasMrs Jenny obstetric historyDwi AnggoroAinda não há avaliações

- Copyright WorksheetDocumento3 páginasCopyright WorksheetJADEN GOODWINAinda não há avaliações

- Appendix Preterism-2 PDFDocumento8 páginasAppendix Preterism-2 PDFEnrique RamosAinda não há avaliações

- Default Password For All TMNet Streamyx Supported ModemDocumento2 páginasDefault Password For All TMNet Streamyx Supported ModemFrankly F. ChiaAinda não há avaliações

- IES VE Parametric Tool GuideDocumento7 páginasIES VE Parametric Tool GuideDaisy ForstnerAinda não há avaliações

- List Megacom 04 Maret 2011Documento3 páginasList Megacom 04 Maret 2011伟汉 陈Ainda não há avaliações

- Cost Estimation and Cost Allocation 3Documento55 páginasCost Estimation and Cost Allocation 3Uday PandeyAinda não há avaliações

- VERTICAL CYLINDRICAL VESSEL WITH FLANGED FLAT TOP AND BOTTOMDocumento1 páginaVERTICAL CYLINDRICAL VESSEL WITH FLANGED FLAT TOP AND BOTTOMsandesh sadvilkarAinda não há avaliações

- AppoloDocumento2 páginasAppoloRishabh Madhu SharanAinda não há avaliações

- The Demands of Society From The Teacher As A PersonDocumento2 páginasThe Demands of Society From The Teacher As A PersonKyle Ezra Doman100% (1)

- El 114 The-Adventures-of-Tom-Sawyer-by-Mark-TwainDocumento11 páginasEl 114 The-Adventures-of-Tom-Sawyer-by-Mark-TwainGhreniel V. Benecito100% (1)

- Test BankDocumento14 páginasTest BankB1111815167 WSBAinda não há avaliações

- Miguel Angel Quimbay TinjacaDocumento9 páginasMiguel Angel Quimbay TinjacaLaura LombanaAinda não há avaliações

- Four Big Secrets of A Happy FamilyDocumento67 páginasFour Big Secrets of A Happy FamilySannie RemotinAinda não há avaliações

- Residency Programs in The USADocumento28 páginasResidency Programs in The USAAnastasiafynnAinda não há avaliações

- AirOS 3.4 - Ubiquiti Wiki#BasicWirelessSettings#BasicWirelessSettingsDocumento24 páginasAirOS 3.4 - Ubiquiti Wiki#BasicWirelessSettings#BasicWirelessSettingsAusAinda não há avaliações

- Anatomy of an AI SystemDocumento23 páginasAnatomy of an AI SystemDiego Lawliet GedgeAinda não há avaliações

- Nano-C ENDocumento1 páginaNano-C ENMartín CoronelAinda não há avaliações

- Einstein & Inconsistency in General Relativity, by C. Y. LoDocumento12 páginasEinstein & Inconsistency in General Relativity, by C. Y. Loicar1997100% (1)

- Newspaper ChaseDocumento10 páginasNewspaper Chasefi3sudirmanAinda não há avaliações

- Shaft Alignment Tools TMEA Series: SKF Product Data SheetDocumento3 páginasShaft Alignment Tools TMEA Series: SKF Product Data SheetGts ImportadoraAinda não há avaliações

- Gartner - Predicts 2021 - Accelerate - Results - Beyond - RPA - To - Hyperautomation-2020Q4Documento17 páginasGartner - Predicts 2021 - Accelerate - Results - Beyond - RPA - To - Hyperautomation-2020Q4Guille LopezAinda não há avaliações

- (Template) ELCT Question Paper - Summer - 2021Documento2 páginas(Template) ELCT Question Paper - Summer - 2021Md.AshikuzzamanAinda não há avaliações

- Elements of PoetryDocumento50 páginasElements of PoetryBeing LoisAinda não há avaliações

- Fake News Detection PPT 1Documento13 páginasFake News Detection PPT 1Sri VarshanAinda não há avaliações