Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

2012SB24 Robert Cotto, Jr.

Enviado por

realhartfordTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

2012SB24 Robert Cotto, Jr.

Enviado por

realhartfordDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Testimony Regarding S.B.

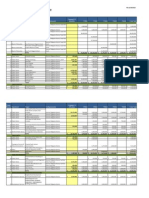

24: An Act Concerning Educational Competitiveness (District Management, Alternative Schools, and School-Based Health Centers) Robert Cotto, Jr., Ed.M. Education Committee February 22, 2012 Senator Stillman, Representative Fleischmann, and distinguished Members of the Education Committee: I am testifying today on behalf of Connecticut Voices for Children, a research-based public education and advocacy organization that works statewide to promote the well-being of Connecticuts children, youth, and families. The Governors Bill on education, S.B. 24, proposes a new way to define district performance using data from the states standardized tests, the CAPT and the CMT. CT Voices has concerns about the definition of district performance index and the related formula. Additionally, we propose amendments to SB 24 related to alternative schools. Finally, we are also concerned about the reduction in funding for School-Based Health Centers. I. Any evaluation of a school district should take into account indicators of basic academic skills-like tests-as well as other evidence of critical thinking, participation in the arts, reading of literature, preparation for skilled work and civic life, growth in social skills, and positive emotional health and development.1 District evaluation should also account for the inequitable distribution of resources available across districts, the economic challenges that children and families face, and the efforts made by parents, teachers, and students to improve the quality of their schools. As currently defined in the bill, the district performance index calculates a composite indicator of the results from only the standard and modified CMT and CAPT in math, reading, science, and writing.2(See table 1)3 The formula and definition fall short of valid and balanced district evaluation. The purpose of this index is to rank and sort districts using standardized test results. The index also assumes a critical role in the definition of conditional funding districts, schools within the Commissioners Network defined in this bill, and the NCLB waiver request.4 In a number of ways, the district performance index may amplify the problems associated with the No Child Left Behind Act. Admittedly, the index attempts to view more levels than just proficient, which was the primary metric of NCLB.5Concerns with the district performance index include: conflating increases in test scores with progress in student learning, reporting district outcomes in a potentially confusing way, ignoring changes in student demographics, disadvantaging districts where many students begin school unprepared to begin school, and other technical issues.6

33 Whitney Avenue New Haven, CT 06510 Phone 203-498-4240 Fax 203-498-4242 53 Oak Street, Suite 15 Hartford, CT 06106 Phone 860-548-1661 Fax 860-548-1783

Web Site: www.ctkidslink.org E-mail: voices@ctkidslink.org

There is a danger that in practice, the easiest way for administrators and educators to improve a districts index will be to accelerate the trend of teaching to the states standardized tests and excluding students from schools and districts that would not score well on those tests such as emerging bilingual students (ELL), students with disabilities, low-income, and/or some minority students.7 The definition in the bill may encourage an incomplete metric that the State Department of Education will use to judge, conditionally fund, and intervene in school districts. We strongly urge further review and broad discussion of this definition of district performance index and consideration of an alternative definition with an evidence-based, understandable, and balanced way of evaluating districts. II. Additionally, CT Voices for Children recommends that SB 24 should be amended to improve the quality, informed consent procedures, and information publicly available regarding alternative schools and programs, schools and programs for at-risk students who require nontraditional modes of instruction. While SB 24 promotes a number of alternative educational options such as charter and magnet schools and encourages those schools to be more inclusive of students who are struggling in regular classrooms,8 the bill does not address the large number of at risk students currently being educated in other types of (largely unregulated) alternative schools and programs. Alternative schools exist in many school districts in Connecticut and can play a valuable role for many at risk students who require nontraditional modes of instruction. Accordingly, SB 24 should be amended to: (1) ensure that alternative schools and programs offer educational opportunities equal to those afforded by traditional high schools, in accordance with the right under Connecticuts Constitution to equal educational opportunity.9 (2) ensure that parents and the public understand what alternative schools and programs are available to students; and (3) ensure that parents and students are able to provide informed consent for placement in an alternative school or program. Further supporting material and proposed language is attached to this testimony in Appendix A. III. Finally, we are pleased to see in this bill the recognition of the need for wraparound services that address the holistic needs of children, particularly for physical and mental health services. Schools are a critical part of the mental health care delivery system, since 70-80% of children receiving services do so through a school setting, which can both reduce stigma and facilitate access.10 Early intervention is an important investment for the state to make because it creates better outcomes for children and provides significant cost savings in the long run. However, we are concerned that the Governors proposed education plan dedicates funding for new community schools and therefore access to expanded health services only to a small number of

struggling school districts, while the needs are great across the state. Furthermore, we are concerned to see the funding for School Based Health Centers was reduced by $412,592 (4%) in the Governors midterm budget,11which will impede the ability of existing health centers to provide services to the children in their schools.

Appendix A: Supporting Material re: Alternative Schools SB 24 should be amended to improve the quality, informed consent procedures, and information publicly available regarding alternative schools and programs, schools and programs for at-risk students who require nontraditional modes of instruction. Overview While SB 24 promotes a number of alternative educational options such as charter and magnet schools and encourages those schools to be more inclusive of students who are struggling in regular classrooms,12 the bill does not address the large number of at risk students currently being educated in other types of (largely unregulated) alternative schools and programs. (The term at risk refers to students who are at risk of dropping out of traditional schools, being excluded from traditional schools due to behavioral challenges, or becoming involved in the juvenile justice system due in part to unmet educational, mental health, and behavioral needs. At risk students frequently benefit from nontraditional modes of instruction offered in smaller, more personalized, environments, with a greater array of social supports). Alternative schools exist in many school districts in Connecticut and can play a valuable role for many at risk students who require nontraditional modes of instruction. However, as described below, there are many barriers to effective alternative education in Connecticut. Accordingly, SB 24 should be amended to: 1. ensure that alternative schools and programs offer educational opportunities equal to those afforded by traditional high schools, in accordance with the right under Connecticuts Constitution to equal educational opportunity.13 2. ensure that parents and the public understand what alternative schools and programs are available to students; and 3. ensure that parents and students are able to provide informed consent for placement in an alternative school or program. Proposed language that addresses these issues is attached to this testimony in Appendix A. The patchwork of alternative educational schools and programs in Connecticut faces several large structural problems and lags far behind the systems in other states. Although there are several high quality alternative schools in Connecticut, there are many pressing problems facing the patchwork of alternative educational schools and programs in our state. Most notably: The State Department of Education does not provide any oversight to alternative schools or programs, nor does it require basic data reporting except in limited circumstances. Indeed, there currently exists no publicly-available list of alternative schools and programs in Connecticut, much less basic information concerning their locations, numbers of students served, curriculum, resources, entry or exit procedures, or reasons for which students are sent to them.14 Many alternative programs are denoted as programs rather than schools, which exempts them from submitting Strategic School Profiles.15 (In

33 Whitney Avenue New Haven, CT 06510 Phone 203-498-4240 Fax 203-498-4242 53 Oak Street, Suite 15 Hartford, CT 06106 Phone 860-548-1661 Fax 860-548-1783

Web Site: www.ctkidslink.org E-mail: voices@ctkidslink.org

fact, only a handful of alternative educational environments throughout the state are classified as schools and therefore make public the basic information required by Strategic School Profiles.16) To the extent they are actually included in mandatory reports, basic demographic and outcome data such as graduation rates for students in alternative programs are commingled with data from the traditional school, making it impossible to determine how many students are sent to alternative programming or evaluate the educational success of these programs.17 In addition, our research has uncovered to date no administrator in Connecticuts State Department of Education charged, even in part, with the portfolio of the states alternative schools and programs. Accordingly, there is not even a rudimentary quality assurance system. Some districts unilaterally move students into alternative schools or programs without parental consent, and sometimes also refuse to allow students to exit the programs back to traditional schools.18 In some cases, schools circumvent formal expulsion procedures by counseling out students with challenging behavioral needs. There currently exists no standard process or set of rules for determining which students are sent to alternative programs or why.19 Many alternative schools do not offer their students the same number of class hours or course offerings that regular public schools require, thus denying vulnerable students access to the quantity and quality of education that they deserve.20 Although it is important for alternative schools and programs to have the flexibility to pursue nontraditional means of instruction, the educational services offered must nonetheless meet a baseline sufficient to guarantee the equal educational opportunity required by Connecticuts Constitution. While some alternative schools help students succeed, others become dumping grounds for vulnerable students, providing pathways to the juvenile justice system.21 Without basic procedural safeguards and quality assurance mechanisms, it is impossible to evaluate which programs are succeeding and which are ineffective.

Other states provide, through legislation and through state education department leadership, sophisticated quality assurance and oversight structures.22Many of the elements of these best practice states have been incorporated into the proposed amendment below. The proposed amendment to SB 24 will make crucial improvements to alternative educational opportunities for Connecticuts at-risk students: By requiring SDE to consult with various stakeholders in developing a definition for alternative schools and programs and developing methods of data collection, the proposed amendment will ensure that light is shed on these often invisible schools and programs. Through establishing standardized processes for enrollment of students, to include informed parental consent, the proposed amendment will ensure that students are being placed in a thoughtful and equitable way.

Through mandating class hours and course offerings, the proposed amendment will ensure that alternative students will have access to the same depth and breadth of education as their peers in regular public schools. Suggested Amendment to SB 24

Section 36 of Raised Bill No. 24 should be amended as follows: Section 10-220d of the 2012 supplement to the general statutes is repealed and the following is substituted in lieu thereof (Effective July 1, 2012): Each local and regional board of education shall provide full access to [regional vocationaltechnical] technical high schools, regional agricultural science and technology education centers, interdistrict magnet schools, charter schools and interdistrict student attendance programs for the recruitment of students attending the schools under the board's jurisdiction, provided such recruitment is not for the purpose of interscholastic athletic competition. Each local and regional board of education shall provide information relating to technical high schools, regional agricultural science and technology education centers, interdistrict magnet schools, charter schools, alternative schools and interdistrict student attendance programs on the board's web site. Each local and regional board of education shall inform students and parents of students in middle and high schools within such board's jurisdiction of the availability of (1) vocational, technical and technological education and training at [regional vocational-technical] technical high schools, and (2) agricultural science and technology education at regional agricultural science, alternative schools and technology education centers. Conn. Gen Stat. 10-186 shall be amended as follows: (a) (1) Each local or regional board of education shall furnish, by transportation or otherwise, school accommodations so that each child five years of age and over and under twenty-one years of age who is not a graduate of a high school or vocational school may attend public school, except as provided in section 10-233c, and subsection (d) of section 10-233d.Boards of education may choose to provide an alternative school or program as an educational option within the district.Any board of education which denies school accommodations, including a denial based on an issue of residency, to any such child shall inform the parent or guardian of such child or the child, in the case of an emancipated minor or a pupil eighteen years of age or older, of his right to request a hearing by the board of education in accordance with the provisions of subdivision (1) of subsection (b) of this section. A board of education which has denied school accommodations shall advise the board of education under whose jurisdiction it claims such child should be attending school of the denial. For purposes of this section, (1) a parent or guardian shall include a surrogate parent appointed pursuant to section 10-94g, and (2) a child residing in a dwelling located in more than one town in this state shall be considered a resident of each town in which the dwelling is

located and may attend school in any one of such towns. For purposes of this subsection, dwelling means a single, two or three family house or a condominium unit. (2) On or before July 1, 2013, the State Department of Education, in consultation with alternative school administrators and educators, parents, students, and advocates, shall (1) define alternative school and alternative program for use by local and regional boards of education, which shall include schools where parents have elected to register their children,(2) establish the criteria by which local and regional boards of education are to measure, collect, and report on data concerning alternative schools and programs in the school district, including but not limited to the following: the reason for attendance in an alternative schools or programs, per pupil expenditure, average duration of attendance, placement of students post- alternative school or program placement, and total number of students served during the school year, (3) establish processes by which schools will refer or students will seek enrollment to alternative schools and programs, including procedures to obtain informed parental consent prior to referral, and discharge students back to traditional public schools, (4) establish procedures to obtain informed parental consent prior to referral. (3) Every school district must publicly disclose, including but not limited to making available on its district website, the existence, purpose, location, contact information, staff directory, and enrollment for all district-operated alternative schools and programs. Conn Gen. Stat. 10-220(c) shall be amended as follows: Annually, each local and regional board of education shall submit to the commissioner of education a strategic school profile report for each school, including each alternative school or program, under its jurisdiction and for the school district as a whole. The superintendent of each local and regional school district shall present the profile report at the next regularly scheduled public meeting of the board of education after each November first. Conn Gen. Stat. 10-16 shall be amended as follows: Each school district shall provide in each school year no less than one hundred and eighty days of actual school sessions for grades kindergarten to twelve, inclusive, nine hundred hours of actual school work for full-day kindergarten and grades one to twelve, inclusive, and four hundred and fifty hours of half-day kindergarten, provided school districts shall not count more than seven hours of actual school work in any school day towards the total required for the school year.Such requirements shall also apply to alternative schools and programs unless the Commissioner of the State Department of Education waives such requirements, pursuant to procedures established by the State Department of Education. If weather conditions result in an early dismissal or a delayed opening of school, a school district which maintains separate morning and afternoon half-day kindergarten sessions may provide either a morning or afternoon half-day kindergarten session on such day. Conn. Gen. Stat. 10-16b shall be amended as follows: (a) In the public schools, the program of instruction offered shall include at least the following subject matter, as taught by legally qualified teachers, the arts; career education; consumer education; health and safety, including, but not limited to, human growth and development, nutrition, first aid,

disease prevention, community and consumer health, physical, mental and emotional health, including youth suicide prevention, substance abuse prevention, safety, which may include the dangers of gang membership, and accident prevention; language arts, including reading, writing, grammar, speaking and spelling; mathematics; physical education; science; social studies, including, but not limited to, citizenship, economics, geography, government and history; and in addition, on at least the secondary level, one or more world languages and vocational education. For purposes of this subsection, world languages shall include American Sign Language, provided such subject matter is taught by a qualified instructor under the supervision of a teacher who holds a certificate issued by the State Board of Education. For purposes of this subsection, the arts means any form of visual or performing arts, which may include, but not be limited to, dance, music, art and theatre. Such program of instruction outlined above shall also be available to students enrolled in alternative schools and programs. Conn. Gen. Stat. 10-233f(b) shall be amended as follows: A local or regional board of education may reassign a pupil to a regular classroom program in a different school in the school district and such reassignment shall not constitute a suspension pursuant to section 10-233c, or an expulsion pursuant to section 10-233d. A student may also attend an alternative school or program, provided informed parental consent for the placement is obtained prior to referral.

1Rothstein, Jacobsen, and Wilder. Grading Education: Getting Accountability Right. Economic Policy Institute; Washington, D.C. Teachers College Press; New York, NY: 2008. See Chapter 2 on Weighting public education. 2See SB 24, Sec. 1 (39). Definition of District Performance Index 3Table 1

StandardsBased Level Weight

4See

Below Basic 0

Basic 0.25

Proficient 0.5

Goal .75

Advanced 1

SB 24, Sec. 1 (40). Definition of Conditional Funding District. Also see Explanation of commissioners network in SB 24, Sec. 18. (d) 1 6. Also see Connecticut State Department of Education. Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) Flexibility Waiver Request: Section 2, Principle 2: State-Developed Differentiated Recognition, Accountability, and Support. CT Department of Education. Web. 7 Feb. 2012. <sde.ct.gov> 5See Ho, Andrew Dean. The Problem With Proficiency: Limitations of Statistics and Policy Under No Child Left Behind. Educational Researcher, Vol. 37, No. 6 (2008): pp. 351-360. Web. 27 Sept. 2011. 6See Koretz, Daniel. Measuring Up: What Educational Testing Really Tells Us. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009. Print. A longer list of the problems with the district performance index include: Mistakes increases in test indicators with progress in student learning. Determines districts performance only on standardized tests in four subjects Ignores qualitative evidence of teaching and learning; and student well-being. Reports district performance on tests in a convoluted manner Disadvantages districts where many students begin school unprepared Assumes that districts with high ratings (or increases) have high-quality instruction. Ignores shifts and demographic changes in student populations The index over-weights the advanced category and under-weights the other levels 7See Koretz 2008, particularly Chapter 10: Inflated Test Scores for an overview. Also see Vasquez Heilig, J. & DarlingHammond, L. (2008). Accountability Texas-style: The progress and learning of urban minority students in a high-stakes testing context. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. 30(2), 75-110. Web. 1 Feb. 2011. Also see Vasquez Heilig, J. & Darling-Hammond, L. (2008). Accountability Texas-style: The progress and learning of urban minority students in a high-stakes testing context. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. 30(2), 75-110. Web. 1 Feb. 2011. Also see Valenzuela et. al. Leaving Children Behind: How Texas Style Accountability Fails Latino Youth. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2005. Print. 8SB 24 provides funding for the creation of new charter schools with strategies to engage and records of serving (A) Students with histories of low academic performance, (B) students who receive free or reduced priced school lunches, (C) students with histories of behavioral and social difficulties, (D) students eligible for special education services, or (E) students who are English language learners; See SB 24, Section 8 (D)b(1). It also gives priority in the application process to charter schools whose primary purpose is to serve these populations (SB 24, Section 52, (c)3(A)) and those that demonstrate highly credible and specific strategies to attract, enroll and retain these students, (SB 24, Section 52, (c)3(E)). 9See, Horton v. Meskill, 172 Conn. 615 (1977), which found that the right to education is basic and fundamental under the states constitution and public school students are entitled to equal enjoyment of that right. 10 Protecting the Health of Connecticuts Young People, Connecticut Association of School Based Health Centers, (October 2010), available at: http://www.ctschoolhealth.org/Announcements/view.asp?id=54 11See Dannel Malloy, FY 2013 Governors Midterm Budget Adjustments (February 8, 2012) at B-79 (line item School Based Health Clinics), available at http://www.ct.gov/opm/lib/opm/budget/2012_midterm_budget/pdfs/fy2013midtermbudget_forweb.pdf 12SB 24 provides funding for the creation of new charter schools with strategies to engage and records of serving (A) Students with histories of low academic performance, (B) students who receive free or reduced priced school lunches, (C) students with histories of behavioral and social difficulties, (D) students eligible for special education services, or (E) students who are English language learners; See SB 24, Section 8 (D)b(1). It also gives priority in the application process to charter schools whose primary purpose is to serve these populations (SB 24, Section 52, (c)3(A)) and those that

33 Whitney Avenue New Haven, CT 06510 Phone 203-498-4240 Fax 203-498-4242 53 Oak Street, Suite 15 Hartford, CT 06106 Phone 860-548-1661 Fax 860-548-1783

Web Site: www.ctkidslink.org E-mail: voices@ctkidslink.org

demonstrate highly credible and specific strategies to attract, enroll and retain these students, (SB 24, Section 52, (c)3(E)). 13See, Horton v. Meskill,172 Conn. 615 (1977), which found that the right to education is basic and fundamental under the states constitution and public school students are entitled to equal enjoyment of that right. 14See email from Charlene Russell-Tucker, State Department of Education (January 6, 2011). 15See Laura McCargar, Invisible Students: The Role of Alternative and Adult Education in the Connecticut School-toPrison Pipeline, Connecticut Pushout Research and Organizing Project, (December 2011), 24, available at: http://ctprop.org/ 16Alternative schools that submitted SSPs in 2009-2010 (the most recent year for which SSPs are available) include: the Alternative Center for Excellence in Danbury, Stevens Alternative High School in East Hartford, Briggs High School in Norwalk, and Thames River Academy in Norwich (see the Strategic School Profile Reports function on the Connecticut Education and Research (CEDaR) database, available at: http://sdeportal.ct.gov/Cedar/WEB/ResearchandReports/SSPReports.aspx?type=SSP).Many more alternative schools, including those publicly listed by local districts on their websites and those whose administrators participate in the Connecticut Association of Alternative Schools and Programs (CAASP), do not complete SSPs. 17 The state tracks the demographics but not educational attainment of students in so-called 90 Programs (a term stemming from a PSIS identification code number), which are district-run schools and programs serving at risk students. The State Department of Education (SDE) reported that fifty such programs spread across 27 school districts were in operation in Connecticut in 2009. Based on local district websites, researcher Laura McCargar identified more than 50 district-defined alternative schools or programs in operation in the state, of which only 9 were included in the 90 Program list provided by SDE (See, McCargar, 46). 18See McCargar 30-32. In addition, informal conversations with lawyers who represent students in alternative education programs have yielded no examples of students successful exiting the alternative education program to return to the traditional high school. In the absence of basic data reporting requirements, we cannot assess whether these anecdotes represent outliers or the norm. 19See, McCargar, 30-32 20See, McCargar, 49-50 21See, McCargar, 20-25, 47-49 22See, Cheryl Almeida, Cecilia Le, Adria Steinberg, and Roy Cervantes, Reinventing Alternative Education: An Assessment of Current State Policy and How to Improve It, Jobs for the Future, (September 2010), available at: http://www.jff.org/sites/default/files/AltEdBrief-090810.pdf. See also, Camilla Lehr, Eric Lanners, and Cheryl Lange, Alternative Schools: Policy and Legislation Across the United States. University of Minnesota Institute on Community Integration (October 2003), available at: http://ici.umn.edu/products/docs/Alternative_Schools_Report_1.pdf. See also, Sarah Esty, memo Re: Alternative Schools Best Practices, (October 28, 2011), on file with Connecticut Voices for Children.

Você também pode gostar

- 20150717163253 (1)Documento1 página20150717163253 (1)realhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- Second Petition From ConnDOTDocumento4 páginasSecond Petition From ConnDOTrealhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- Hartford Ballot Nov 2015Documento2 páginasHartford Ballot Nov 2015realhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- Zionhill MasterplanDocumento1 páginaZionhill MasterplanrealhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- Zoning Regulations MasterDocumento195 páginasZoning Regulations MasterkevinhfdAinda não há avaliações

- BRONIN Recommended Budget For Fiscal Year 2017Documento357 páginasBRONIN Recommended Budget For Fiscal Year 2017kevinhfdAinda não há avaliações

- FY15 16 Budget Book WEB ReducedDocumento328 páginasFY15 16 Budget Book WEB ReducedrealhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- Legal Opinion On CensureDocumento4 páginasLegal Opinion On CensurerealhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- Part 1 Crime Historical Analysis Spread SheetDocumento1 páginaPart 1 Crime Historical Analysis Spread SheetrealhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- BuckinghamSquareMasterPlan-2015 06 17 PDFDocumento4 páginasBuckinghamSquareMasterPlan-2015 06 17 PDFrealhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- Resolution Larry DeutschDocumento1 páginaResolution Larry DeutschrealhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- Final Moylan Petition LetterDocumento16 páginasFinal Moylan Petition LetterrealhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- HPDDocumento35 páginasHPDrealhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- BuckinghamSquareMasterPlan-2015 06 17 PDFDocumento4 páginasBuckinghamSquareMasterPlan-2015 06 17 PDFrealhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- CIP BudgetDocumento4 páginasCIP BudgetrealhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- Grading and Drainage - 150213Documento1 páginaGrading and Drainage - 150213realhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- Letter To HPS SuperintendentDocumento2 páginasLetter To HPS SuperintendentrealhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- City of Hartford Capital Improvement Plan FY2016 - FY2020 Part II: Project DescriptionsDocumento7 páginasCity of Hartford Capital Improvement Plan FY2016 - FY2020 Part II: Project DescriptionsrealhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- Trinity Athletic Fields Site PlanDocumento8 páginasTrinity Athletic Fields Site PlanrealhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- Stormwater Report-Compiled 150217Documento103 páginasStormwater Report-Compiled 150217realhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- City of Hartford Capital Improvement Plan FY2016 - FY2020 Part II: Project DescriptionsDocumento7 páginasCity of Hartford Capital Improvement Plan FY2016 - FY2020 Part II: Project DescriptionsrealhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- Sotc 2015 FinalDocumento14 páginasSotc 2015 FinalrealhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- CTHartford01b POSDocumento345 páginasCTHartford01b POSrealhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- Circular LTR 2015-02 Connecticut Reaffirms Safety of Artificial TurfDocumento2 páginasCircular LTR 2015-02 Connecticut Reaffirms Safety of Artificial TurfrealhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- City of Hartford, Connecticut Capital Improvement Program - FY2016 Through FY2020Documento3 páginasCity of Hartford, Connecticut Capital Improvement Program - FY2016 Through FY2020realhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- Capital Av 393 CSPR 120914pubDocumento5 páginasCapital Av 393 CSPR 120914pubrealhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- COIReportOfFactualFindings 2Documento32 páginasCOIReportOfFactualFindings 2realhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- Agenda Council Meeting October 27, 2014Documento1 páginaAgenda Council Meeting October 27, 2014realhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- Highlights Demographic Survey of American Jewish College Students 2014Documento8 páginasHighlights Demographic Survey of American Jewish College Students 2014realhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- HartfordDocumento30 páginasHartfordrealhartfordAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (120)

- Adb Sov Projects 20200317Documento381 páginasAdb Sov Projects 20200317YuLayAinda não há avaliações

- Engineering Degree PlanDocumento8 páginasEngineering Degree Planashvinbalaraman0Ainda não há avaliações

- Chapter I Objectives and Function of Confucian ReligiousDocumento13 páginasChapter I Objectives and Function of Confucian ReligiousWelsenAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson Plan in Physical Education 6Documento2 páginasLesson Plan in Physical Education 6SIMPLEJG100% (1)

- Breakthrough EducationDocumento2 páginasBreakthrough EducationPeter Jay Corros100% (1)

- PHD Regulations 2012 PDFDocumento15 páginasPHD Regulations 2012 PDFNithin JoseAinda não há avaliações

- Classroom Observation AssignmentDocumento2 páginasClassroom Observation Assignmentapi-302422262Ainda não há avaliações

- Project #1-Caregiver's BrochureDocumento2 páginasProject #1-Caregiver's BrochureswarnaAinda não há avaliações

- Educational Theory A Qur' Anic Outlook PDFDocumento382 páginasEducational Theory A Qur' Anic Outlook PDFPddfAinda não há avaliações

- Initial Test Schedule For PMA and GDPDocumento1 páginaInitial Test Schedule For PMA and GDPHamzee Rehman100% (1)

- Lesson Plan ICTDocumento3 páginasLesson Plan ICTAnthony RafolsAinda não há avaliações

- Axiology focus-WPS OfficeDocumento2 páginasAxiology focus-WPS OfficeJohn Paul Condat BallesterosAinda não há avaliações

- Study Material-INTRODUCTION TO FACILITATING LEARNER-CENTERED TEACHINGDocumento2 páginasStudy Material-INTRODUCTION TO FACILITATING LEARNER-CENTERED TEACHINGJosette BonadorAinda não há avaliações

- Resume - Kristy HerDocumento2 páginasResume - Kristy Herapi-283950188Ainda não há avaliações

- 2311 Gcse 9 1 Notional Component Grade BoundariesDocumento6 páginas2311 Gcse 9 1 Notional Component Grade BoundariesanurudinethmaAinda não há avaliações

- Individual Factors in The Learner's DevelopmentDocumento9 páginasIndividual Factors in The Learner's Developmentharold castle100% (1)

- The 73 TOPIK (Test of Proficiency in Korean) NoticeDocumento2 páginasThe 73 TOPIK (Test of Proficiency in Korean) NoticeNilufar YunusovaAinda não há avaliações

- Reciprocal Teaching StrategyDocumento3 páginasReciprocal Teaching StrategySaraya Erica OlayonAinda não há avaliações

- Workforce Development in JamaicaDocumento32 páginasWorkforce Development in JamaicaPaulette Dunn100% (1)

- Module 4 Science & Technology and National Development (ACQUIRE)Documento5 páginasModule 4 Science & Technology and National Development (ACQUIRE)ACCOUNT ONEAinda não há avaliações

- Ктп ин инглишDocumento38 páginasКтп ин инглишЖансая ЖакуповаAinda não há avaliações

- Learning For A Future: Refugee Education in Developing CountriesDocumento267 páginasLearning For A Future: Refugee Education in Developing CountriesI CrazyAinda não há avaliações

- Class Rules & Procedures TanDocumento2 páginasClass Rules & Procedures TansherrillmattAinda não há avaliações

- Curriculum Vita: Deepti RahangdaleDocumento2 páginasCurriculum Vita: Deepti RahangdaleDeepti ThakreAinda não há avaliações

- Communication For EngineersDocumento7 páginasCommunication For EngineershomsomAinda não há avaliações

- Advantages and Difficulties of Comprehensive TrainingDocumento2 páginasAdvantages and Difficulties of Comprehensive Traininglil meowAinda não há avaliações

- Problems in Reading Comprehension in EngDocumento14 páginasProblems in Reading Comprehension in EngSushimita Mae Solis-AbsinAinda não há avaliações

- Implementing Audio Lingual MethodsDocumento8 páginasImplementing Audio Lingual MethodsSayyidah BalqiesAinda não há avaliações

- MathdlpDocumento10 páginasMathdlpPearl DiansonAinda não há avaliações

- Ed 103 Part Iv.bDocumento25 páginasEd 103 Part Iv.bLaurice TolentinoAinda não há avaliações