Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Indian Literatureencarta

Enviado por

Perry MasonDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Indian Literatureencarta

Enviado por

Perry MasonDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Indian Literature, literature in the languages of India, as well as those of Pakistan ( see Indian Languages).

For information on the literature written in the classicial language, Sanskrit, see Sanskrit Literature. The Indian literary tradition is primarily one of erse and is also essentially oral. The earliest works were composed to !e sung or recited and were so transmitted for many generations !efore !eing written down. "s a result, the earliest records of a te#t may !e later !y se eral centuries than the con$ectured date of its composition. Furthermore, perhaps !ecause so much Indian literature is either religious or a reworking of familiar stories from the Sanskrit epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, and the mythological writings known as Puranas, the authors often remain anonymous. %iographical details of the li es of most of the earlier Indian writers e#ist only in much later stories and legends, so that any history of Indian literature is !ound to raise more &uestions than it answers. 'ften, much less is known a!out an Indian poet who died in the early ()th century than of the *nglish medie al poet +eoffrey ,haucer or of the Latin poet -irgil. Linguistic and Cultural Influences .uch traditional Indian literature is deri ed in theme and form not only from Sanskrit literature !ut from the %uddhist and /ain te#ts written in the Pali language and the other Prakrits (medie al dialects of Sanskrit). This applies to literature in the 0ra idian languages of the south as well as to literature in the Indo1Iranian languages of the north. Successi e in asions of Persians and Turks, !eginning in the (2th century, resulted !y a!out (344 in most of India !eing go erned !y .uslim rulers. The influence of Persian and Islamic culture (see Persian Literature) is strongest in literature written in 5rdu, although important Islamic strands can !e found in other literatures as well, especially those written in %engali, +u$arati, and 6ashmiri. "fter (7(3, when the %ritish controlled nearly all of India, entirely new literary alues were esta!lished that remain dominant today. The Tamil Tradition The only Indian writings that incontesta!ly pre1date the influence of classical Sanskrit are those in the Tamil language. "nthologies of secular lyrics on the themes of lo e and war, together with the grammatical1stylistic work Tolkappiyam ('ld ,omposition), were once thought to !e ery ancient8 they are now !elie ed to date no earlier than from a!out the (st to the 9th century "0. Later, !etween the :th and )th centuries, Tamil sectarian de otional poems were composed, often claimed as the first e#amples of the Indian bhakti tradition (see !elow). "t some indeterminate date !etween the ;nd and 9th centuries, two long Tamil erse romances (sometimes called epics) were written< Cilappatikaram (The /ewelled "nklet) !y Ilanko "tikal, which has !een translated into *nglish (()=) and ():9)8 and its se&uel Manimekalai (The +irdle of +ems), a %uddhist work !y ,attanar. Medieval Indian Literature The first true works of literature in most of the main indigenous Indian languages tend to date from a!out (;44. %efore then, any work of literature would ha e !een

composed in the literary languages< Sanskrit or one of the Prakrits in the north or Tamil in the 0ra idian south. Sanskrit Epic Influence In this early period, which ended in a!out (944, the main literary productions in all the languages of India were ersions of stories from the Sanskrit epics and the Puranas. .any of the ernacular treatments of the Ramayana, Mahabharata, and BhagavataPurana, well known to educated Indian readers e en today, were written during this period. For e#ample, the first true .alayalam work, which is a ersion of the Ramayana, dates from a!out the (=th century. Other Themes 'ther themes were also treated in medie al Indian literature. The earliest works in many of the languages were sectarian, designed to ad ance or to cele!rate some unorthodo# regional !elief. *#amples are the Caryapadas, Tantric (see Tantra) erses of the (;th century that are the earliest sur i ing works in %engali, and the Lilacaritra (c. (;74), a .arathi prose account of the words and deeds of the founder of the .ahanu!ha a sect. In 6annada (6anarese) from the (4th century, and later in +u$arati from the (=th century, the first truly indigenous works are /ain romances8 ostensi!ly the li es of /ain saints, these are actually popular tales !ased on Sanskrit and Pali themes. Tales !esides these sectarian works were composed8 e#amples in >a$asthani are !ardic tales of chi alry and heroic resistance to the first .uslim in asions?such as the (;th1 century epic poem Prithiraja-raso !y ,hand %ardai of Lahore. Popular stories and !allads were also composed, such as those of *ast %engal. Later important religious literatures de eloped that were associated with certain regional philosophies and sects< te#ts in Tamil from the (=th to the (9th century de oted to the medie al @indu Shai a1siddhanta sect8 the works of the Lingayats (a @indu sect de oted to the worship of Shi a) in 6annada, especially the acanas, or AsayingsB, of %asa a, the mid1(;th1century founder of the sect, and his disciples8 and the Tantric te#ts, especially those from north1east India, which de eloped later into genres such as the mangala-kavya (poetry of an auspicious happening) of %engal. This erse was addressed to deities such as .anasa (a snake goddess), purely local forms of the female di ine principle called 0e i (see @induism). .ost important of all for later Indian literature were the first traces in the ernacular languages of the northern Indian cults of 6rishna and of >ama. The 6rishna story de eloped in Sanskrit from the Mahabharata through the Bhagavata-Purana, to the (;th1century poem !y /ayde , called the itagovinda (The ,owherdCs Song)8 !ut in a!out (244, a group of religious lo e poems written in .aithili (eastern @indi of %ihr) !y the poet -idyapati were a seminal influence on the cult of >adha16rishna in %engal and the whole religio1erotic literature associated with it. The Bhakti Tradition The full flowering of the >adha16rishna cult, under the @indu mystics ,aitanya in %engal and -alla!hacharya at .athura, in ol ed bhakti! The word bhakti implies a personal de otion to a god far different from the rituals of %rahmanism?an intense

longing compara!le to the desire of lo ers or of a child separated from his or her mother. Indeed, bhakti may !e concei ed of in terms of all forms of human lo e. "lthough earlier traces of this attitude are found in the work of the Tamil "l ars (mystics who wrote ecstatic hymns to -ishnu !etween the 3th and (4th centuries), the enthusiasms of the Sufi mystics of Islam pro!a!ly produced the surge of bhakti that flooded e ery channel of Indian intellectual and religious life !eginning in the late (9th century. The sentiment was the same, !ut the recipient aried !y region. %eside the writings of the de otees of >adha16rishna, bhakti was addressed to >ama (an a atar of -ishnu), most nota!ly in the " adhi (eastern @indi) works of Tulsi 0as8 his Ramcaritmanas (Lake of the "cts of >ama, (9321(9338 trans. ()9;) has !ecome the authoritati e, repeatedly recited ersion of the Ramayana for the whole @indi1speaking north. The early gurus, or founders of the Sikh religion, especially Danak and "r$un, wrote bhakti hymns to their concepts of deity. These are the first written documents in Pun$a!i (Pan$a!i) and form part of the "di ranth (First, or 'riginal, %ook), the sacred scripture of the Sikhs, which was first compiled !y "r$un in (:42. In the (:th century, in other regions, bhakti was directed to other forms of di inity. For e#ample, the >a$asthani princess and poet .ira %ai addressed her lyric erse to 6rishna, as did the +u$arati poet Darsimh .ehta. Indian Literature of the Middle Period In the literature from a!out (944 to (744, the stream of reworkings of the traditional Sanskrit epics continued una!ated, while at the same time the use of 5rdu and of Persian literary forms arose. Traditional Material In the (:th century, /agannath 0as wrote an 'riya ersion of the Bhagavata and Tuncattu *ruttacchan, the so1called father of .alayalam literature, wrote recensions of traditional literature. To these were added, particularly in the (7th century, a deli!erate imitation of Sanskritic forms and metres in addition to a highly Sanskritic oca!ulary !y pandita, or AlearnedB poets, or !y court poets like those of the Telugu1speaking kingdom of -i$aynagar. @istorical e ents were recounted in (7th1century "ssamese and .arathi prose chronicles, !allads, and folk drama in ol ing much dance and song. Urdu Literature 0uring this period, Indian literature was also written in 5rdu, a new language. 5rdu, spoken in the 0elhi region, is similar to @indi and contains many words from "ra!ic and Persian. The 5rdu poets almost always wrote in Persian forms, using the ghaEal for lo e poetry in addition to an Islamic form of bhakti, the masnavi for narrati e erse, and the marsiya for elegies. Friting in 5rdu !egan first in the Islamic kingdoms of the 0eccan, where literary e#periment was apparently easier and the prestige of the orthodo# literary language, Persian, was less strong8 it culminated there in the lyrics of Fali. 5rdu then gained use as a literary language in 0elhi and Lucknow. The ghaEals of .ir and +hali! mark the highest achie ement of 5rdu lyric erse. The 5rdu poets were mostly sophisticated, ur!an artists, !ut some adopted the idiom of folk poetry, and this is typical of the erse written in Pun$a!i, Pushtu, Sindhi, or other regional languages.

The Modern Period Poets such as +hali!, for e#ample, li ed and worked during the %ritish era, when a literary re olution occurred in all the Indian languages as a result of contact with Festern thought, when the printing press was introduced (!y ,hristian missionaries), and when the influence of Festern educational institutions was strong. 0uring the mid1 ()th century in the great ports of %om!ay, ,alcutta, and .adras, a prose literary tradition arose?encompassing the no el, short story, essay, and literary drama (this last incorporating !oth classical Sanskrit and Festern models)?that gradually engulfed the customary Indian erse genres. The northern heartland of 0elhi and 5ttar Pradesh was the last to !e affected !y this new tradition8 and !ecause .uslims for the most part did not take ad antage of the new education, 5rdu writing preser ed much of its integrity. 5rdu poets remained faithful to the old forms and metres while %engalis were imitating such *nglish poets as Percy %ysshe Shelley in the (724s or T. S. *liot in the ()24s. 0uring the last (94 years many writers ha e contri!uted to the de elopment of modern Indian literature, writing in any of (9 ma$or languages (including, of course, *nglish). In the process of FesterniEation, %engali has led the way and today has one of the most e#tensi e literatures of any Indian language. 'ne of its greatest representati es is >a!indranath Tagore, the first Indian to win the Do!el PriEe for Literature (()(=). .uch of his prose and erse is a aila!le in his own *nglish translations. Fork !y two other great ;4th1century Indian leaders and writers is also widely known through translation< the erse of the Islamic leader and philosopher Sir .uhammad I&!al, originally written in 5rdu and Persian8 and the auto!iography of .ohandas 6. +andhi, My #$periments %ith Truth, originally written in +u$arati !etween ();3 and ();) and now considered a classic. "lthough the !ulk of later ;4th1century Indian writing remains untranslated, se eral writers working in *nglish are relati ely well known to the Fest. They include .ulk >a$ "nand, among whose many works the early affectionate &ntouchable (()=9) and Coolie (()=:) are no els of social protest8 and >. 6. Darayan, writer of no els and tales of illage life in southern India. The first of DarayanCs many works, '%ami and (riends, appeared in ()=98 among his more recent titles are The #nglish Teacher (()74), The )endor o* '%eets (()7=), and &nder the Banyan Tree (()79). "mong the younger authors writing of modern India with nostalgia for the past is "nita 0esai?as in Clear Light o* +ay (()74). @er ,n Custody (()72) is the story of a teacherCs fatal enchantment with poetry. -ed .ehta, although long resident in the 5nited States, recalls his Indian roots in a series of memoirs of his family and of his education at schools for the !lind in India and "merica8 among these works are )edi (()7;) and 'ound 'hado%s o* the -e% .orld (()7:).(

1"Indian Literature," Microsoft Encarta 99 Encyclopedia. 1993-1998 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reser ed.

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Bollywood Bites The BulletDocumento4 páginasBollywood Bites The BulletPerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- PoetryDocumento5 páginasPoetryPerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- MarxismDocumento2 páginasMarxismPerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- Roman Art and Architectur1Documento4 páginasRoman Art and Architectur1Perry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- Indian LanguagesDocumento2 páginasIndian LanguagesPerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- Philosophy of ReligionDocumento4 páginasPhilosophy of ReligionPerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- ReligionDocumento12 páginasReligionPerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- Perception and GestaltDocumento3 páginasPerception and GestaltPerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- Habermas, Jürgen (1929-), German Sociologist and PhilosopherDocumento1 páginaHabermas, Jürgen (1929-), German Sociologist and PhilosopherPerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- CensorshipDocumento8 páginasCensorshipPerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- Hungarian Finnish and Greek LiteratureDocumento15 páginasHungarian Finnish and Greek LiteraturePerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- JihadDocumento2 páginasJihadPerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- EpistemologyDocumento7 páginasEpistemologyPerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- Civil Rights and Civil LibertiesDocumento11 páginasCivil Rights and Civil LibertiesPerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- Dange and RoyDocumento2 páginasDange and RoyPerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- FibroidsDocumento1 páginaFibroidsPerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- Mesopotamian Art and ArchitectureDocumento6 páginasMesopotamian Art and ArchitecturePerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- FormDocumento8 páginasFormPerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- Word Changes to Indicate RelationshipsDocumento1 páginaWord Changes to Indicate RelationshipsPerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- About NietzscheDocumento2 páginasAbout Nietzschebasescu_traianAinda não há avaliações

- Language of LiteratureDocumento3 páginasLanguage of LiteraturePerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- Slang JargonDocumento2 páginasSlang JargonPerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- The Gme British HistoryDocumento8 páginasThe Gme British HistoryPerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- William ShakespeareDocumento2 páginasWilliam ShakespearePerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- Stress From BritannicaDocumento2 páginasStress From BritannicaPerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- Plato AristotleDocumento13 páginasPlato AristotlePerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- CriticismDocumento3 páginasCriticismSachin KetkarAinda não há avaliações

- TRIBEDocumento3 páginasTRIBEPerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- Critique of Pure Reason (1781), in Which He Examined The Bases of Human Knowledge and CreatedDocumento3 páginasCritique of Pure Reason (1781), in Which He Examined The Bases of Human Knowledge and CreatedPerry MasonAinda não há avaliações

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- 2014 - Aliyar Year PlannerDocumento1 página2014 - Aliyar Year PlannerSuresh DhanasekarAinda não há avaliações

- Languages of IndiaDocumento10 páginasLanguages of IndiaNyegosh DubeAinda não há avaliações

- Dse, ChatraDocumento251 páginasDse, ChatraAparnaAinda não há avaliações

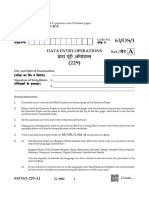

- 229 Os Data Entry Oprations (Set A B C)Documento24 páginas229 Os Data Entry Oprations (Set A B C)mahaksatija2525Ainda não há avaliações

- Bal Sahitya 2011Documento4 páginasBal Sahitya 2011Rama Prakash Kizhakke AdanathAinda não há avaliações

- UGC List of Fake UniversitiesDocumento49 páginasUGC List of Fake UniversitiesRajveerAinda não há avaliações

- Malyalam Sample Question Paper PDFDocumento9 páginasMalyalam Sample Question Paper PDFArunAinda não há avaliações

- Birthday in Different LanguagesDocumento6 páginasBirthday in Different Languageskartheek kumarAinda não há avaliações

- 10th Prelims 1st Stage 2022 Question Paper With Answer Key 1Documento17 páginas10th Prelims 1st Stage 2022 Question Paper With Answer Key 1Sreenath MuraliAinda não há avaliações

- Sanskrit WebsitesDocumento6 páginasSanskrit WebsitesjyotisatestAinda não há avaliações

- EAP 796 ReportDocumento5 páginasEAP 796 ReportBarnali DuttaAinda não há avaliações

- GDCE - Shortlistedlist - Updated Hubli ContactsDocumento84 páginasGDCE - Shortlistedlist - Updated Hubli Contactsarbaz khanAinda não há avaliações

- Sree Lalita Sahasra Namavali in Sanskrit 2Documento43 páginasSree Lalita Sahasra Namavali in Sanskrit 2jatin.yadav1307Ainda não há avaliações

- Specialist-GDMO-Vacancy List Final PDFDocumento26 páginasSpecialist-GDMO-Vacancy List Final PDFMeera GouthamAinda não há avaliações

- Indian Languages - Working KnowledgeDocumento31 páginasIndian Languages - Working Knowledgevinayak100% (1)

- Kalagnanam Part1 - Sri Potuluri Virabrahmendra Swami KalagnanamDocumento1 páginaKalagnanam Part1 - Sri Potuluri Virabrahmendra Swami Kalagnanamnsprasad88Ainda não há avaliações

- RamodantamDocumento9 páginasRamodantamdubeypmAinda não há avaliações

- Urdu (ودرا)Documento13 páginasUrdu (ودرا)saji kumarAinda não há avaliações

- Learn Saraiki 012 Names of RelationsDocumento68 páginasLearn Saraiki 012 Names of Relationskhan VinesAinda não há avaliações

- AksharamukhaDocumento20 páginasAksharamukhamansiAinda não há avaliações

- Government of Maharashtra State Common Entrance Test Cell, MumbaiDocumento294 páginasGovernment of Maharashtra State Common Entrance Test Cell, MumbaianiketAinda não há avaliações

- Zindagi Shayari (Top 20 Sher) RekhtaDocumento1 páginaZindagi Shayari (Top 20 Sher) Rekhtarohitkrishnan.connectAinda não há avaliações

- Typing in SanskritDocumento8 páginasTyping in SanskritccparamAinda não há avaliações

- Blood Relation Sheet 2Documento3 páginasBlood Relation Sheet 2Yogi JiAinda não há avaliações

- Iptv LinkDocumento31 páginasIptv Linkgaurav agrawal100% (2)

- Class Ix - Mil (Khasi) PDFDocumento3 páginasClass Ix - Mil (Khasi) PDFNidasuk Thma100% (1)

- HS/XII/A/k/19Documento7 páginasHS/XII/A/k/19M. Amebari NongsiejAinda não há avaliações

- Sanskrit Nibandh MandakiniDocumento222 páginasSanskrit Nibandh MandakiniachublrAinda não há avaliações

- Malayalam Alphabet, Pronunciation and LanguageDocumento9 páginasMalayalam Alphabet, Pronunciation and LanguageVenkates Waran GAinda não há avaliações