Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

2011 Aerobic Exercise Training in Addition To Conventional Physiotherapy For Chronic Low Back Pain, A Randomized Controlled Trial

Enviado por

johaskinezDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

2011 Aerobic Exercise Training in Addition To Conventional Physiotherapy For Chronic Low Back Pain, A Randomized Controlled Trial

Enviado por

johaskinezDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

1681

BRIEF REPORT

Aerobic Exercise Training in Addition to Conventional Physiotherapy for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Carol W. Chan, PT, MSc, Nicola W. Mok, PT, PhD, Ella W. Yeung, PT, PhD

ABSTRACT. Chan CW, Mok NW, Yeung EW. Aerobic exercise training in addition to conventional physiotherapy for chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011;92:1681-5.

Objective: To examine the effect of adding aerobic exercise to conventional physiotherapy treatment for patients with chronic low back pain (LBP) in reducing pain and disability. Design: Randomized controlled trial. Setting: A physiotherapy outpatient setting in Hong Kong. Participants: Patients with chronic LBP (N46) were recruited and randomly assigned to either a control (n22) or an intervention (n24) group. Interventions: An 8-week intervention; both groups received conventional physiotherapy with additional individually tailored aerobic exercise prescribed only to the intervention group. Main Outcome Measures: Visual analog pain scale, Aberdeen Low Back Pain Disability Scale, and physical tness measurements were taken at baseline, 8 weeks, and 12 months from the commencement of the intervention. Multivariate analysis of variance was performed to examine betweengroup differences. Results: Both groups demonstrated a signicant reduction in pain (P.001) and an improvement in disability (P.001) at 8 weeks and 12 months; however, no differences were observed between groups. There was no signicant difference in LBP relapse at 12 months between the 2 groups (22.30, P.13). Conclusions: The addition of aerobic training to conventional physiotherapy treatment did not enhance either short- or longterm improvement of pain and disability in patients with chronic LBP. Key Words: Exercise; Low back pain; Physical therapy modalities; Rehabilitation. 2011 by the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine

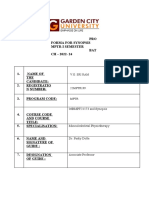

LBP develops in 5% to 10% of persons with acute LBP,3 with pain persisting for more than 12 weeks. Chronic LBP is also a costly epidemic, with both direct health care and indirect costs (such as reduced productivity) imposed on the society. Notably, chronic LBP is associated with various physical, emotional, and psychosocial dysfunctions that eventually cause deterioration in the quality of life. Disuse and physical deconditioning are commonly evident in individuals with chronic LBP.4,5 In addition, insufcient exercise was acknowledged as a risk factor for the development of LBP.6 As such, exercise therapy for both primary and secondary prevention of LBP has been advocated as a priority research area. Exercise programs involve a mixture of training modes ranging from specic motor control exercise of the trunk muscles, strengthening, stretching, and/or aerobic training to more complex training programs.7-9 The isolated effect of aerobic exercise therapy has been examined in individuals with chronic LBP.10,11 The results revealed that aerobic exercise induced a short-term improvement in depression10,11 and a reduction of pain and disability10 in people with chronic LBP, when compared with electrotherapy to the lower back10 and a waiting list control.11 However, it has been argued that various exercise treatments could only cause a small but not clinically relevant change in people with chronic LBP when the effect of various exercise was studied alone.12 In view of the multiple problems within the biopsychosocial spectrum presented by people with chronic LBP, it has been suggested that a combined (rather than a single) treatment approach should be considered for contemporary clinical trials.13 The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of the addition of an 8-week, individually supervised, and progressive aerobic exercise program to conventional physiotherapy treatment for patients with chronic LBP. We tested the hypothesis that additional aerobic exercises would further improve physical tness, pain, and disability in patients with chronic LBP. METHODS Participants Forty-six subjects (10 men, 36 women; mean age SD, 46.010.2y) were recruited from the Department of Physiotherapy at the David Trench Rehabilitation Centre, Hong Kong. The progress of subjects through the randomized trial is presented in gure 1. Inclusion criteria included subjects with LBP symptoms for at least 12 weeks and declared medically t to

OW BACK PAIN (LBP) is very common, and yet little is L known about its etiology or pathogenetic mechanism. The reported lifetime prevalence for LBP is as high as 84%. Chronic

1 2

From the Centre for Sports Training and Rehabilitation, Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong. Presented in part to the Hong Kong Physiotherapy Association, December 8 9, 2007, Hong Kong. Supported by the Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, Hong Kong Polytechnic University and Department of Physiotherapy, David Trench Rehabilitation Centre. No commercial party having a direct nancial interest in the results of the research supporting this article has or will confer a benet on the authors or on any organization with which the authors are associated. Trial Registration Number: ISRCTN23753357. Reprint requests to Ella W. Yeung, PT, PhD, Centre for Sports Training and Rehabilitation, Dept of Rehabilitation Sciences, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong, e-mail: ella.yeung@polyu.edu.hk. 0003-9993/11/9210-00403$36.00/0 doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2011.05.003

List of Abbreviations ALBPS LBP METs Aberdeen Low Back Pain Disability Scale low back pain metabolic equivalents

Arch Phys Med Rehabil Vol 92, October 2011

1682

AEROBIC EXERCISE FOR CHRONIC LOW BACK PAIN, Chan

Fig 1. CONSORT ow chart indicating ow of subjects through the trial. Abbreviation: VAS, visual analog scale.

undertake physical tness testing and exercise. Exclusion criteria included cardiac, systemic, or inammatory disease, or a workers compensation client. Subjects were randomly allocated to the control (conventional physiotherapy, n22) or the intervention (aerobic training and conventional physiotherapy, n24) group, using a random number table concealed in sealed envelopes. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Medical Research Ethical Committee and were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Conventional Treatment Both groups received conventional physiotherapy treatments that are commonly used clinically for chronic LBP, including electrical modalities (interferential therapy, ultrasound, or heat pack), passive segmental mobilization to the lumbar spine into end range, back mobilization exercise, abdominal stabilization exercise, and back care advice (ergonomic principles, proper posture, and lifting techniques). The choice of treatment was made by the physiotherapist based on the assessment ndings.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil Vol 92, October 2011

Aerobic Training Subjects in the intervention group received an additional aerobic training program for 8 weeks, individually prescribed and supervised by a physiotherapist. This duration was chosen to allow physiologic adaptations to aerobic training.14 The target exercise heart rate was calculated by using the percentage of heart rate reserve method: (maximal heart rate resting heart rate) (intensity fraction) resting heart rate. The exercise intensity was set at 40% to 60% of heart rate reserve15 and gradually progressed up to 85%, at a 5% increment each week. Subjects heart rates were monitored with a polar heart rate monitor.a The rating of perceived exertion (Borg CR-10 scale)16 was also used to provide a complementary estimation to exercise intensity. To achieve the recommended aerobic improvement,15 subjects performed 20 minutes of exercise, 3 times a week. Two training sessions were given and were supervised by the physiotherapist. Subjects were also instructed to perform at least 1 additional training at home each

AEROBIC EXERCISE FOR CHRONIC LOW BACK PAIN, Chan

1683

week. Home exercise adherence was recorded by each subject on a log sheet. The mode of exercise included treadmill walking/running, stepping, or cycling exercises, as preferred by the subject. Physical Fitness Measurements Physical tness parameters included aerobic capacity, back extensor muscular endurance, lower back and hamstring muscle exibility, and percentage of body fat. Aerobic capacity testing was performed according to the modied Bruce protocol on the treadmill.15 The rst 2 stages were performed at 2.74km/h at 0% and 5% grade, respectively. The third stage corresponds to the rst stage of the standardized Bruce protocol. At 3-minute intervals, the inclination was increased by 2% with a concomitant increase in speed. The Sorensen test for lumbar extensor endurance was performed with the subject holding the upper body unsupported in a horizontal prone position and the lower body xed to the plinth. The sit-and-reach test for exibility was evaluated with the Flex-Tester.b The percentage of body fat was assessed by obtaining skinfold measurements of 3 sites (chest, abdomen, and thigh in men; triceps, suprailiac, and thigh in women) with skinfold callipersc and by using the Siri equation.14 Outcome Measures The primary study outcomes were (1) pain measured with a 100-mm visual analog scale, and (2) functional disability using a validated Chinese version of the Aberdeen Low Back Pain Disability Scale (ALBPS).17 The secondary study outcomes were the physical tness parameters. The level of pain, ALBPS, and tness parameters were measured at baseline and 8 weeks. At the 12-month follow-up, the subjects were contacted by telephone and asked to complete the ALBPS. The number of LBP relapses was also obtained. This was dened as an LBP episode that required medical consultation after discharge from the study. Data Analyses Intention-to-treat analysis was carried out for all analyses. Outcomes variables were compared across time by using analysis of variance for continuous variables and chi-square analysis for categorical variables. A multivariate analysis of variance test was performed to examine between-group differences. All analyses were conducted using the SPSS version 16.0.d Values are presented as mean SD. The signicance level was set at equal to .05. RESULTS There was an overall exercise attendance rate of 91.3%. Table 1 presents the baseline demographic characteristics of the subjects. No signicant differences were found between the

Table 1: Baseline Characteristics of Subjects

Baseline Characteristics Control (n22) Intervention (n24)

Age (y) Men/women Duration of current symptom (mo) Recurrence of LBP Area of LBP Local LBP and above knee Below knee, not nerve root Below knee, nerve root Physical activity (MET min wk1) None: 0 Light: 1 to 450 Moderate: 450750 Vigorous: 750 Physical tness parameters Body fat percentage (%) VO2max (mL kg1 min1) Back extensor endurance (s) Sit-and-reach test (cm) Pain and disability scores Pain score VAS (mm) ALBPS score

46.011.5 5/17 14.121.5 6 (27.2) 10 (45.5) 7 (31.8) 5 (22.7) 10 (45.5) 2 (9.1) 1 (4.5) 9 (40.9) 23.17.8 40.46.9 42.834.9 19.29.1 59.521.5 30.813.9

47.18.3 5/19 11.813.7 2 (8.3) 13 (54.2) 7 (29.1) 4 (16.7) 14 (52.2) 3 (10.9) 4 (8.7) 13 (28.2) 24.97.2 39.04.7 46.528.1 22.09.3 59.513.9 28.811.0

NOTE. Values are mean SD, n, or n (%). Abbreviations: VAS, visual analog scale; VO2max, maximum oxygen consumption.

2 groups. Based on the American College of Sports Medicines age-adjusted standards, 43.5% and 47.8% of the subjects ranked below the 50th percentile for maximum oxygen consumption and body fat percentage, respectively, and 74% of the subjects had exibility classied as fair to poor.15 An average of 35.614.1 minutes of aerobic exercises at 5.601.30 metabolic equivalents (METs) was performed at each session. Most subjects (83.3%) were able to reach the target intensity range of 50% to 85% HRR at the end of the 8-week intervention. Eighty-one percent (n18) of the subjects chose walking, jogging, or running as the preferred mode of aerobic exercise training. Seventy-seven percent of the subjects in the intervention group performed additional aerobic exercises at home for at least 30min/wk. A mean of 486.9323.7 MET min wk1 was accrued for subjects in the intervention group. At 8 weeks, signicant improvements in pain and functional disability were reported in both groups (P.001). Improvements in disability were sustained in both groups at 12 months when compared with the baseline (P.001). However, no signicant differences were detected in pain and disability between the 2 groups at either time (table 2). The intervention

Table 2: Pain and Disability Scores at 8 Weeks and 12 Months Follow-up

Pain and Disability Scores Control (n22) Baseline 8wk 12mo Baseline Intervention (n24) 8wk 12mo Difference in Mean Change Scores (95% CI) at 8wk Difference in Mean Change Scores (95% CI) at 12mo

Pain score (0100) Disability score (0100)

59.521.5 30.813.9

34.521.1* 20.813.0*

NT 24.015.1*

59.513.9 28.811.0

31.520.9* 19.012.7*

NT

3.0 (10.2 to 16.2)

NA 3.9 (0.6 to 8.4)

18.415.2* 0.22 (6.0 to 5.5)

NOTE. Values are mean SD or as otherwise indicated. Abbreviations: CI, condence interval; NA, not applicable; NT, not tested. *Compared with baseline, P.001.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil Vol 92, October 2011

1684

AEROBIC EXERCISE FOR CHRONIC LOW BACK PAIN, Chan Table 3: Physical Fitness Parameters Before and After 8-Week Intervention

Control (n22) Physical Fitness Parameters Baseline 8wk P Baseline Intervention (n24) 8wk P

Body weight (kg) Body mass index (kg/m2) Body fat percentage (%) VO2max (mL kg1 min1) Back extensor endurance (s) Sit-and-reach test (cm)

58.59.5 22.82.9 23.17.8 40.46.9 42.834.9 19.29.1

58.29.4 22.72.9 22.27.8 40.27.3 49.937.1 24.08.4

.13 .24 .04* .74 .11 .001*

59.88.5 23.493.0 24.97.2 39.04.7 46.528.1 22.09.3

59.28.4 23.33.0 24.27.0 40.35.2 59.127.5 26.29.7

.02* .02* .03* .02* .005* .001*

NOTE. Values are mean SD or as otherwise indicated. Abbreviation: VO2max, maximum oxygen consumption. *Statistically signicant.

group improved in all physical tness parameters, while the control group improved only in exibility and percentage of body fat. However, there were no signicant differences between groups for changes in physical tness parameters (table 3). Chi-square analysis revealed no signicant difference between groups (22.30, P.13) in the incidents of LBP relapse at the 12-month follow-up. DISCUSSION This study investigated the effect of adding an aerobic exercise program to conventional physiotherapy in people with chronic LBP. The results indicated that the addition of supervised aerobic exercise training did not enhance the improvement in pain and disability. There was signicant short-term improvement in pain and disability in both groups, which reafrms the ndings of the meta-analysis on exercise therapy for the management of LBP by Hayden et al.18 In this metaanalysis, the authors suggested that exercise therapy, including abdominal stabilization exercise, seems to be slightly effective at pain reduction and functional improvement for chronic LBP. In the present study, back mobilization and abdominal stabilization exercise were included as conventional treatment, which might contribute to the improvement as evidenced by the improvement in pain and functional disability as well as exibility (note: the sit-and-reach test requires lumbar spine mobility) in both groups. We opted not to measure pain at the 12-month follow-up because it has been acknowledged that uctuation in pain level seems to be one of the characteristic features in chronic LBP; in addition, the intensity of pain is not associated with activity level in people with chronic LBP.19,20 Thus, only ALBPS and the number of LBP relapses were assessed at the 12-month follow-up in this study. The aerobic exercise training had no adverse effects on the subjects. The poor physical tness level evident in our patients is consistent with the ndings of previous studies,4,5 which suggest the importance of aerobic exercise for chronic LBP. Although the intervention group showed an improvement in all tness parameters after 8 weeks, the magnitude of change may be too small. The poor baseline tness level is a major limiting factor in this study; perhaps the loading stimulus is too small to result in noticeable effects on pain and disability. The subjects may have beneted from a more intense exercise program of longer duration, increased frequency, or both. In the metaanalysis that examined intervention characteristics that could improve outcomes for patients with chronic LBP, it was shown that individually designed and supervised exercise is more effective.21 We consider the ongoing supervision from the physiotherapist as an integral part of an individualized exercise therapy intervention. In this study, the physiotherapist moniArch Phys Med Rehabil Vol 92, October 2011

tored the subjects adherence to the exercise training program, as evidenced by the ability of most subjects to reach the target intensity range. In the long-term, adherence might improve if the subjects become aware of the benets of, and their bodies response to the exercises. They could learn to modify the exercises according to their tness level and uctuations in pain level. Study Limitations There are several limitations to consider in this study. First, our sample size was relatively small to detect signicant improvements in outcomes. Second, the nature of the aerobic exercise training made it impossible to conceal treatment allocation to the subjects or the investigators. The lack of blinding of the outcome assessors to group allocation may result in bias. Furthermore, changes in physical tness parameters were not assessed at 12 months, making it difcult to identify long-term changes. CONCLUSIONS The ndings of this study revealed that in patients with chronic LBP, the addition of aerobic training to conventional physiotherapy treatment did not lead to improvement of pain and disability at the short- and long-term follow-up beyond that achieved with conventional physiotherapy alone.

Acknowledgment: tical advice. We thank Raymond Cheung, PhD, for statis-

References 1. Deyo RA, Rainville J, Kent DL. What can the history and physical examination tell us about low back pain. JAMA 1992;268:760-5. 2. Walker BF. The prevalence of low back pain: a systematic review of the literature from 1966 to 1998. J Spinal Disord 2000;13:205-17. 3. Frymoyer JW. Back pain and sciatica. N Engl J Med 1988;318: 291-300. 4. Verbunt JA, Seelen HA, Vlaeyen JW, et al. Disuse and deconditioning in chronic low back pain: concepts and hypotheses on contributing mechanisms. Eur J Pain 2003;7:9-21. 5. Van der Velde G, Mierau D. The effects of exercise on percentile rank aerobic capacity, pain and self-rated disability in patients with chronic low back pain: a retrospective chart review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000;81:1457-63. 6. WHO Scientic Group on the Burden of Musculoskeletal Conditions at the Start of the New Millennium. The burden of musculoskeletal conditions at the start of the new millennium. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 2003;919:i-x, 1-218. 7. Moseley L. Combined physiotherapy and education is efcacious for chronic low back pain. Aust J Physiother 2002;48:297-302. 8. Moffett JK, Torgerson D, Bell-Syer S, et al. Randomised controlled trial of exercise for low back pain: clinical outcomes, costs, and preferences. BMJ 1999;319:279-83.

AEROBIC EXERCISE FOR CHRONIC LOW BACK PAIN, Chan

1685

9. UK BEAM Trial Team. United Kingdom Back Pain Exercise and Manipulation (UK BEAM) randomised trial: effectiveness of physical treatments for back pain in primary care. BMJ 2004;329: 1377-84. 10. Chatzitheodorou D, Kabitsis C, Malliou P, Mougios V. A pilot study of the effects of high-intensity aerobic exercise versus passive interventions on pain, disability, psychological strain and serum cortisol concentrations in people with chronic low back pain. Phys Ther 2007;87:304-12. 11. Sculco AD, Paup DC, Fernhall B, Sculco MJ. Effects of aerobic exercise on low back pain patients in treatment. Spine J 2001;1:95-101. 12. van Middlekoop M, Rubinstein SM, Kuijpers T, et al. A systemic review on the effectiveness of physical and rehabilitation interventions for chronic non-specic low back pain. Eur Spine J 2011;20:19-39. 13. Jull G, Moore A. Systemic reviews assessing multimodal treatments. Man Ther 2010;15:303-4. 14. American College of Sports Medicine. ACSMs resource manual for guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010. 15. American College of Sports Medicine. ACSMs guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009. 16. Borg G. Applications of the scaling methods. Champaign: Human Kinetics; 1998.

17. Leung AS, Lam TH, Hedley AJ, Twomey LT. Use of a subjective health measure on Chinese low back pain patients in Hong Kong. Spine 1999;24:961-6. 18. Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Malmivaara AV, Koes BW. Metaanalysis: exercise therapy for nonspecic low back pain. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:765-75. 19. Liszka-Hackzell JJ, Martin DP. An analysis of the relationship between activity and pain in chronic and acute low back pain. Anesth Analg 2004;99:477-81. 20. Huijnen IPJ, Verbunt JA, Roelofs J, Goossens M, Peters M. The disabling role of uctuations in physical activity in patients with chronic low back pain. Eur J Pain 2009;13:1076-9. 21. Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Tomlinson G. Systematic review: strategies for using exercise therapy to improve outcomes in chronic low back pain. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:776-85. Suppliers a. Polar A1 HRM; Electro Oy, Professorintie 5, 90440 Kempele, Finland. b. Novel Products Inc, PO Box 408, Rockton, IL 61072-0408. c. Harpenden skinfold calliper HSK-BI; British Indicators, Baty International, Victoria Rd, Burgess Hill, West Sussex, RHI5 9LR, United Kingdom. d. SPSS Inc, 233 S Wacker Dr, 11th Fl, Chicago, IL 60606.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil Vol 92, October 2011

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Rife Frequencies by NumberDocumento90 páginasRife Frequencies by Numbernepretip100% (5)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Cyriax - Spine: by DR. Akshay A. Chougule (PT) Orthopaedic Manual TherapistDocumento44 páginasCyriax - Spine: by DR. Akshay A. Chougule (PT) Orthopaedic Manual TherapistAishwarya Shah100% (1)

- Vindicate For LBPDocumento10 páginasVindicate For LBPShaun TylerAinda não há avaliações

- WFE Vs McKenzieDocumento5 páginasWFE Vs McKenzieRennyRay0% (1)

- Psychological Approaches To Pain Management Third Edition Ebook PDF Version A Practitioners Ebook PDF VersionDocumento62 páginasPsychological Approaches To Pain Management Third Edition Ebook PDF Version A Practitioners Ebook PDF Versioncarey.sowder235100% (41)

- Materi (Low Back Pain)Documento31 páginasMateri (Low Back Pain)bayudianindraAinda não há avaliações

- Medical Record Summary Template (Disability)Documento17 páginasMedical Record Summary Template (Disability)Alipit Jr. D. ArmanAinda não há avaliações

- Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability QuestionnaireDocumento2 páginasOswestry Low Back Pain Disability QuestionnaireMahendra UcupAinda não há avaliações

- Case Study - Treatment of Plantar Fasciitis With Acupuncture and Tuina (2019)Documento15 páginasCase Study - Treatment of Plantar Fasciitis With Acupuncture and Tuina (2019)wgf26706Ainda não há avaliações

- Clinical Practice Guidelines For The Management of Non-Specific Low Back Pain in Primary Care - An Updated OverviewDocumento14 páginasClinical Practice Guidelines For The Management of Non-Specific Low Back Pain in Primary Care - An Updated OverviewCambriaChicoAinda não há avaliações

- Evidence-Informed Primary Care Management of Low Back Pain - Clinical Practice Guideline - CanadaDocumento49 páginasEvidence-Informed Primary Care Management of Low Back Pain - Clinical Practice Guideline - CanadaCambriaChicoAinda não há avaliações

- Shiatsu & Back ProblemDocumento33 páginasShiatsu & Back ProblemlaukuneAinda não há avaliações

- MEDINEWS 2 Howrah Orthopaedic Hospita1Documento22 páginasMEDINEWS 2 Howrah Orthopaedic Hospita1Dr Subhashish DasAinda não há avaliações

- Diseases of The Spine: 2.1 Back PainDocumento13 páginasDiseases of The Spine: 2.1 Back PainadeAinda não há avaliações

- Spondylolysis SpondylolisthesisDocumento89 páginasSpondylolysis SpondylolisthesisAh ZhangAinda não há avaliações

- Synopsis Template - MPTR 2022 - For Merge-1Documento13 páginasSynopsis Template - MPTR 2022 - For Merge-1sriram gopalAinda não há avaliações

- Chronic PainDocumento36 páginasChronic Painvalysa100% (1)

- MRAT 211 - Lumbar Rehabilitation TransDocumento11 páginasMRAT 211 - Lumbar Rehabilitation TransLovely GopezAinda não há avaliações

- Low Back Pain Practice Guidelines 2013Documento12 páginasLow Back Pain Practice Guidelines 2013silkofosAinda não há avaliações

- 166-Article Text-300-1-10-20190603Documento4 páginas166-Article Text-300-1-10-20190603Achmad JunaidiAinda não há avaliações

- Application of Pilates-Based Exercises in The Treatment of Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain: State of The ArtDocumento5 páginasApplication of Pilates-Based Exercises in The Treatment of Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain: State of The ArtDiana Magnavita MouraAinda não há avaliações

- Manual Therapy of The HipDocumento23 páginasManual Therapy of The HipSardarChangezKhanAinda não há avaliações

- Lumbar Radicular Pain: PathophysiologyDocumento4 páginasLumbar Radicular Pain: PathophysiologynetifarhatiiAinda não há avaliações

- Low Back Pain Among Nurses in Slovenian Hospitals: Cross-Sectional StudyDocumento8 páginasLow Back Pain Among Nurses in Slovenian Hospitals: Cross-Sectional StudyMerieme SafaaAinda não há avaliações

- AINEsDocumento13 páginasAINEsSebastian NamikazeAinda não há avaliações

- Management of Symphysis Pubis Dysfunction During Pregnancy PDFDocumento11 páginasManagement of Symphysis Pubis Dysfunction During Pregnancy PDFHapplo82Ainda não há avaliações

- Lower Back Pains ExercisesDocumento13 páginasLower Back Pains ExercisesArlhona Juana RagoAinda não há avaliações

- Low Back PainDocumento17 páginasLow Back PainRamon Salinas AguileraAinda não há avaliações

- Brosur Young inDocumento17 páginasBrosur Young inEddy Lanang'e JagadAinda não há avaliações

- Research Article: Prevalence of Low Back Pain Among Undergraduate Physiotherapy Students in NigeriaDocumento5 páginasResearch Article: Prevalence of Low Back Pain Among Undergraduate Physiotherapy Students in NigeriaMirza Kurnia AngelitaAinda não há avaliações