Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Locanto - Stravinsky's Late Technique

Enviado por

1111qwerasdfDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Locanto - Stravinsky's Late Technique

Enviado por

1111qwerasdfDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

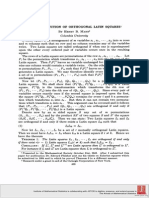

:~ssI:IiI~No ioc~N1o

Co:iosINo vI1n IN1riv~is: IN1riv~iiIc S.N1~x ~No SriI~i

TrcnNIqir IN L~1r S1i~vINsi.musa_302 221..266

Ti~Nsi~1ro n. Cn~ovIci JrNiINs

The use of intervals as the basic material of musical construction consistently

served as an important and deeply personal characteristic of Stravinskys com-

positional process. In his nal serial compositions, however, this aspect assumed

a more decisive role and underwent signicant changes. Stravinskys late writ-

ings, composed in collaboration with Robert Craft, reect this renewed interest

in intervallic construction. In them, the composer repeatedly describes the rst

stages of the creative process as work with intervals and even projects this

practice backwards to cover the entirety of his musical output. Stravinsky thus

emphasises, perhaps excessively, the continuity of his thinking despite the

evident changes that took place throughout his compositional career.

1

The new and more important role occupied by the intervallic component in

Stravinskys serial compositions is, to a large extent, a consequence of the

gradual abandonment of pitch collections (octatonic, whole-tone, diatonic, and

so on),

2

which had played such a decisive role in his earlier music, in favour of

a growing tendency to make systematic use of twelve-note aggregates a ten-

dency accentuated particularly in the compositions which follow Threni.

3

Although Stravinsky continued to prefer the same pc sets (particularly tetra-

chords) which in his earlier compositions were derived from diatonic or octatonic

collections, the sketches for his last compositions seem to indicate that the

creative process has moved from specic intervals to larger combinations (and

not vice versa), thereby producing harmonic environments which can appear

variously diatonic, octatonic or chromatic.

By freeing the treatment of intervals from a broader system of pitch organi-

sation,

4

Stravinsky seems to have followed a path which presents some similari-

ties to but also some profound differences from the predominantly motivic

pathway followed by Schoenberg and his pupils in their gradual departure from

traditional tonality. Although all of these composers treated the intervallic com-

ponent in different ways, it became for them the foundational aspect of a

motivic technique that is, one based on the use of a restricted number of

intervallic congurations which serve a basic unifying function within a musical

work. Yet the specic way in which Stravinsky used intervallic motives emerges

through a study of his many unpublished versions of pieces, and these must be

evaluated in relation to the peculiarities of his aesthetic.

DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-2249.2011.00302.x

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 221

2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK

and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA

All of this raises an interesting issue: although in so-called atonal music the

(presumable) absence of a hierarchy among the sounds allows the composer to

employ all twelve pitch classes as he pleases (considering them exclusively in

terms of their intervallic relationships),

5

with the adoption of serial procedures a

new constructive order is imposed. Now, while in the work of other composers

one could say that this new constructive order encompasses and essentially

identies with motivic-intervallic syntax, in Stravinsky the result of such identi-

cation is instead rather problematic, because these two aspects operate accord-

ing to slightly but signicantly different criteria. In the following pages, I

will attempt to demonstrate how, particularly in the compositions from Agon

onwards, this approach provided Stravinsky with a stimulus, rather than an

obstacle, to composition. I will also attempt to interpret some characteristics of

Stravinskys creative process and serial technique which are by now well known

but whose deeper motivations still require further investigation.

Motivic-Intervallic Syntax: General Characteristics

Even if it is evident that the use of intervals as the basic material of the

compositional process constitutes a central feature of Stravinskys late musical

thought, the specic technical means employed lend themselves to being

described in rather different ways.

6

Stravinsky never specied exactly what he

meant by the expression composing with intervals, nor does the study of his

sketches offer any denitive answers. A great deal of his work with pitch material,

in fact, took place at the keyboard, in a phase prior to that documented in the

earliest sketches, which in actuality record a stage in the creative process that is

already quite advanced.

7

Given this modus operandi one can easily imagine that

Stravinskys interval-based procedures were not codied according to any kind

of systematic approach. This, however, does not exclude the possibility that such

procedures can be described retrospectively in theoretical terms.

To this end, I will use as a brief rst example the original twelve-note row of

A Sermon, a Narrative, and a Prayer (Ex. 1). The row can be subdivided into four

distinct trichords, three of which the rst, second and fourth belong to set

class [014]. Segments 2 and 4 are ordered as <0, 1, 4>, while segment 1 is

ordered as <1, 0, 4>.

8

From an intervallic point of view, if we consider the

intervals apart from their melodic direction (ascending or descending), that is, as

unordered pitch-class intervals (interval classes), all three segments contain a

Ex. 1 Stravinsky, A Sermon, a Narrative, and a Prayer: subset structure of the original

twelve-note row

[014] [014] [014] [015]

1 1 1 3 3 4

3 4 4

222 :assi:iLiaNo LocaN1o

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

semitone (ic1), a minor third (ic3) and a major third (ic4).

9

In consequence, we

could describe the three segments as three statements, differently ordered, of the

same group of three interval classes, or equally well as three statements, differ-

ently ordered, of the same set class [014].

Considering the segments of the row as unordered sets corresponds to a

constructive logic which, far from being exclusive to Stravinsky, seems deeply

rooted in most twelve-note and serial music in general and is certainly very

familiar from the published literature on serialism. Many of the basic operations

which concern the subset structure of the twelve-note row are based on this

logic. In Schoenberg, Berg and Webern, the rows are often organised in such a

way as to maximise certain segments which, if considered apart from the order

of the pitches, belong to the same set class. To mention only a couple of

examples, one could cite the row of Schoenbergs String Quartet No. 4, in which

one can identify four segments of three notes as belonging to set class [015]

(Ex. 2a),

10

or the row employed in the twelve-note section of the third movement

of Bergs Lyric Suite, which contains four segments belonging to the class [0126]

(Ex. 2b).

11

Furthermore, in many twelve-note compositions the idea of considering some

segments of the row as unordered sets constitutes an essential premise for

establishing various types of formal relationships. The internal structure of the

row, in fact, allows some of its subsets to preserve the same global pitch content

even after the typical transformational operations (transposition, retrograde and

inversion) are applied.This gives rise to a network of relations among the various

forms of the row employed in a composition.

12

The very notion of hexachordal

combinatoriality,

13

which plays a fundamental role in Schoenbergs twelve-note

music, is based on the possibility of conceiving the hexachords as unordered

collections.

The global intervallic content of these serial segments of course plays an

important role in enabling this type of relation from the moment that each

Ex. 2a Schoenberg, String Quartet No. 4: subset structure of the fundamental

twelve-note row

[015] [015]

[015] [015]

Ex. 2b Berg, Lyric Suite: subset structure of the twelve-note row of the third

movement

[0126] [0126]

[0126] [0126]

Co:iosiNc wi1n IN1cnvaLs 223

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

segment can be considered either as an unordered set of pitch classes or as an

unordered set of interval classes. Particular attention to intervallic content forms

the basis of Weberns practice of deriving a row from the reiteration of a single

basic cell. To mention only one well-known example: in Cantata No. 1, Op. 29

(Ex. 3),

14

the four discrete trichords of the row are all members of the same set

class [014]. The importance of the global intervallic content of set class [014]

(semitone, minor third and major third) is underlined by the presence of the

semitone between the rst and second segments and between the third and

fourth segments, and by that of the minor third between the second and third

segments.

To summarise: the idea of globally considering the pitches and/or intervals

contained in some serial segments typically constitutes one of the basic con-

structive criteria of twelve-note serialism. Nevertheless, this criterion corre-

sponds only in part to the concept of intervallic motive which I hope to

illuminate in the music of Stravinsky. Generally, the constituent pitches of a

motive can be used in either a harmonic or a melodic sense,

15

and compared in

any order. Nevertheless, Stravinsky, working with the orientation of single inter-

vals, radically modies the physiognomy of his motives, which can thereby

assume forms corresponding to different set classes. From this point of view,

then, an intervallic motive no longer corresponds, in any sense, to a class of

unordered pc sets. Rather, Stravinskys operations act more on the level of single

intervals than on the level of the global congurations within which these single

intervals are included.

The difference becomes clear if we return to the third segment of the row of

A Sermon, a Narrative, and a Prayer (see again Ex. 1). This segment belongs not

to set class [014], but rather to the class [015]. As a consequence, its global

intervallic content is different. However, this segment shares with the other

segments two of its three intervals (ic1 and ic4), which are merely arranged

differently (Ex. 4): in the third segment they are joined in the same direction,

thereby producing an ic5; in the rst, second and fourth segments they are joined

in opposed directions, thereby producing an ic3 (Ex. 4).

16

In short, considered as

unordered pc sets, only three of the four segments of the row of Ex. 1 turn out

to belong to the same class; considered, however, as intervallic motives formed

through the combination in varying directions of two intervals, they turn out

to all be members of the same motive class (Ex. 5): the semitone and the major

third conjoined, expressed symbolically as 14.

17

Ex. 3 Webern, Cantata No. 1, Op. 29: subset and intervallic structure of the original

twelve-note row

[014] [014] [014] [014]

O RI

1

3 1

224 :assi:iLiaNo LocaN1o

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

This simple alteration in intervallic direction constitutes a precious compo-

sitional resource in Stravinskys hands. Joining various forms of a single (or at

most two) motivic class(es), he creates twelve-note rows as in the previous

example as well as smaller or larger successions of pitches to be employed

either melodically or harmonically in a musical passage. For instance, in Ex. 6 we

can observe the succession of pitches which serves as the basis for three episodes

(bars 722) included in the rst section (up to the prima volta) of the rst of the

ve Movements. This passage conceals a closely woven fabric of overlapping

motives of the semitone-tone (12) and semitone-tritone (16) types (indicated

by square brackets). Depending on the orientation assumed by the two intervals,

the rst motive (12) produces sets of three pitches belonging to set classes [012]

and [013]. The second motive (16), on the other hand, produces collections

belonging to set class [016] regardless of the orientation assumed by the two

intervals.

18

It should be apparent that, in dening this type of intervallic syntax as motivic,

the term motive is being used with some degree of latitude. In the Formenlehre

tradition, for example, a motive is typically conceived as a structural nexus of

rhythm and intervals.

19

In Stravinskys music, however, a motive is essentially an

abstract conguration of intervals: pitch components and rhythm are treated as

initially distinct and separate dimensions which can subsequently be related.

20

As

suggested above, in spite of some apparent similarities, this conception of inter-

Ex. 4 Intervallic motive class 14 in the two forms of set class [015] and [014]

5

1

1

0 0

ic4

(ic5)

(ic4)

ic3

ic1

ic1

4

14 motive

Ex. 5 Stravinsky, A Sermon, a Narrative, and a Prayer: motivic-intervallic structure of

the original twelve-note row

[014] [014] [014] [015]

1 1 1 3 3 4

3 4 4 4

5 1

E D B A

C B G

F

F

E D A 4 4

4

4

(3)

(5)

(3) (3)

1

14 motive

1 1 1

Co:iosiNc wi1n IN1cnvaLs 225

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

vallic motive also differs radically from that familiarly applied to the post-tonal

music of Schoenberg, Berg and Webern. For these composers, the concept of

motivic elaboration which guaranteed coherence in tonal music was gradually

replaced by a constructive principle based on the use of fundamental intervallic

constellations which operate at a more basic level. According to Martina

Sichardt, this reduction of the various Gestalten within a passage to its most

elementary intervallic basis a tendency Schoenberg himself had consciously

put into practice in his own analytical formulations represented a fundamental

premise for the elaboration of the twelve-note method.

21

In this respect, it is

interesting to note that most of the basic intervallic constellations which form the

expressive vocabulary of melodic gestures in Schoenbergs compositions consist

merely of the union of two or three intervals one of which is usually the

semitone disposed in a particular arrangement.

22

An interesting analogy with Stravinskys practice can nonetheless be glimpsed

wherever Schoenberg subjects these basic combinations of intervals to a process

of variation. Jack Boss, for example, has demonstrated that the majority of the

intervallic motives in the rst of Schoenbergs Vier Lieder, Op. 22, could be

derived by applying three types of modication to a motive formed from the

combination of one ic1 and one ic3.

23

Boss considers all of the possible arrange-

ments of these two intervals (that is, <+1, +3>, <+1, -3>, <-1, +3>, <-1, -3>, <+3,

+1>, <+3, -1>, <-3, +1> and <-3, -1>) as variants belonging to the same motivic

category. Moreover, each of these forms can undergo in its turn three funda-

mental types of variation, two of which involve octave complementation and

pitch reordering. All of this corresponds exactly to my denition of motive

class 13. However, despite this similarity, a profound discrepancy remains

regarding the very concept of motive. Schoenbergs procedures, as described

by Boss, effectively identify motive as an entity which may be subjected to a

wide range of transformations while remaining largely recognisable. According

to Boss, for example, the third basic category of variation employed by

Ex. 6 Stravinsky, Movements, i: motivic-intervallic structure of the succession of

pitches contained in each of the three solo episodes of bars 722

[012] [016] [016] [016] [016] [016] [016] [012] [012]

[012] [016] [013] [013] [016] [016] [016] [012] [012]

[016] [016] [016] [016] [012] [012] [013]

12 motive 16 motive

[013] [012] [016] [016]

1 1 1 1

2 6

(3)

[7] = 5

2

6

(5) (1)

226 :assi:iLiaNo LocaN1o

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Schoenberg involves the expansion of intervals.

24

In this respect, the Schoenber-

gian concept of variation implies a decisively greater quantity and variety

of forms derivable from a single motive than those which occur in Stravinsky.

Still more important is the fact that the Schoenbergian concept of variation

implies a broader process, one which involves the entire plan of the musical form.

Indeed, in Schoenberg, the variation of a motive cannot be dissociated from

the concept, central to the Austro-German tradition, of motivic elaboration,

understood as a means of conferring coherence and organic unity on a compo-

sition.

25

All of this is foreign to Stravinskys musical thought, in which the

manipulation of intervallic motives is understood as a procedure for generating

primary compositional material capable of being employed as a point of creative

departure.

The idea developed in particular through the work of George Perle

26

that

a basic cell or referential sonority can be presented even in a vertical sense

could be considered another point of contact between Stravinskys motivic-

intervallic syntax and the post-tonal harmonic language of Schoenberg, Berg

and Webern. However, unlike the notion of the Stravinskian intervallic motive,

the concept of the basic cell consists of a xed conguration of intervals and

corresponds therefore to a single set class.

27

The most decisive difference,

however, concerns the contrasting aesthetic-musical aspects within which a

motive unit is taken to function: in the music of Schoenberg, Berg and Webern

an intervallic conguration disposed vertically always maintains a motivic char-

acter from which, in fact, the idea of chord as motive arises even in a

dynamic sense. The nature of this element is expressed by the Schoenbergian

concept of unrest:

What is a motive? A motive is something that gives rise to motion. A motion is that

change in a state of rest, which turns it into its opposite. Thus, one can compare a

motive with a driving force ... . What causes motion is a motor. One must distin-

guish between motor and motive ... . A thing is termed a motive if it is already subject

to the effect of a driving force, has already received its impulse, and is on the verge of

reacting to it ... . The smallest musical event can become a motive if it is permitted

to have an effect; even an individual tone can carry consequences. (Schoenberg

1995, p. 386; emphases in original)

In the music of Schoenberg, the simultaneous presentation of pitches produced

by an intervallic conguration can be considered the result of an extreme

concentration in time of an event whose essence is decidedly dynamic tied,

that is, to the movement of time. Therefore, if Schoenbergs motivic conception

is essentially temporal the very idea of a suppression of temporality associated

with the Schoenbergian law of the unity of musical space implies in actuality

the concept of time the Stravinskian approach conversely returns to a con-

ception we may dene as spatial or plastic-visual: the motive is understood as

a conguration of intervals which can be arranged in two dimensions, as in

visual space.

Co:iosiNc wi1n IN1cnvaLs 227

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Theoretical Aspects

Before examining some specic examples, a number of purely theoretical con-

siderations are worth reviewing in greater detail. As mentioned earlier, the

possibility of freely orienting any intervallic conguration ensures that a single

motivic class corresponds to more than one set class. With respect to the motives

formed from two different intervals (the model Stravinsky most frequently

employs), each of the fteen possible combinations generally produces two

different set classes, depending on the orientation of the two intervals conjoined.

Only those motives containing the tritone produce a unique set class regardless

of intervallic orientation (see the left-hand side of Table 1).

28

The right-hand side of Table 1, however, shows the motives which are capable

of producing a particular set class of three pitches. For example: the set class

[013] can be obtained by uniting one ic1 and one ic2 in the same direction

(motive 12), or by uniting a single ic2 and a single ic3 in opposite directions

(motive 23). As can be seen, according to the global intervallic content,

29

each

set class can be produced by a variable number of up to three intervallic motives.

Only set class [048], which contains three identical intervals (three ic4s), cannot

be produced by any motive formed from two different intervals.

The motives formed through the union of three different interval classes do

not constitute an analytically relevant object since too many different set classes

are generated. For example, a motive which combines a semitone, tone and

minor third in whatever order and direction would produce ten different set

classes containing either three or four distinct pitch classes:

30

Table 1 Motives formed by two different conjoined intervals

Motivic-

intervallic

class

Set class(es)

produced

Set class Associated

motivic-intervallic

class(es)

12.............................................(012) (013) (012) ............................12

13............................................ (013) (014) (013) ............................12 13 23

14.............................................(014) (015) (014) ............................13 14 34

15.............................................(015) (016) (015) ............................14 15 45

16 .............................................(016) (016) ............................15 16 56

23.............................................(013) (025) (024) ............................24

24.............................................(024) (026) (025) ............................23 25 35

25.............................................(025) (027) (026) ............................24 26 46

26 .............................................(026) (027) ............................25

34.............................................(014) (037) (036) ............................36

35.............................................(025) (037) (037) ............................34 35 45

36............................................ (036) (048) ............................

45.............................................(015) (037)

46 .............................................(026)

56 .............................................(016)

228 :assi:iLiaNo LocaN1o

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

123: [013][023][0123][0124][0125][0134][0135][0136][0146][0236]

Moreover, the majority of these ten set classes can be derived from other motives

covering three different intervals. Thus every set class can be associated with an

excessively broad number of motives and vice versa.

However, motives that may be realised using only two interval classes, one of

which repeats once (for example, 121) to form a set of four pitches, are

relatively common. In Stravinskys case, motives of this type are typically those

which employ the semitone in conjunction with the whole tone or perfect fth

(121, 212, 151 and 515). As can be seen on the left-hand side of

Table 2, these motives produce only two or three different set classes, according

to the orientation assumed by the intervals. The right-hand side of the same

table, on the other hand, show how two different motives of this type can, at

times, produce the same set class. For example, the set class [0123] is obtained

by both 121 and 212.

Intervallic Syntax and Serial Technique

The major discrepancy between the motivic-intervallic syntax described so far

and serial technique as conceived by Stravinsky himself consists in the fact

that while the rst operates predominantly on the level of single intervals, the

second acts essentially on the level of pitch-class sets, understood as the units of

primary structural value.

31

Different orientations of the single intervals of a

motive can produce forms which belong to different set classes; by contrast,

neither the retrograde, nor the inversion, nor the retrograde inversion, nor any

type of permutation of the order of a particular pc set is capable of generating a

different set class. From the point of view of musical perception, one could even

say that motivic-intervallic syntax attributes to the quality of single intervals an

importance superior to the globalising tendency of pc sets. Put simply, intervallic

logic tends towards disintegration, serial technique towards unication.

Table 2 Motives formed by two different intervals, with one of them repeated once

Motivic-

intervallic

class

Set class(es)

produced

Set class Associated

motivic-intervallic

class(es)

121............................(012) (0123) (0134) (012)..............................121

212............................(0123) (0235) (0123)............................121 212

151............................(0145) (0156) (0167) (0134)............................121

515............................(0156) (0167) (0158) (0145)............................151

(0156)............................151 515

(0158)............................515

(0167)............................151 515

(0235)............................212

Co:iosiNc wi1n IN1cnvaLs 229

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Despite these discrepancies, in Stravinskys compositional thought the two

aspects seem to aim towards the same end. In order to clarify how this occurs,

consider Ex. 7, which reproduces the three choral statements at the beginning,

in the middle and towards the end of the Dies irae of the Requiem Canticles.

These three fragments constitute an autonomous formal layer which interacts

with the surrounding layers of contrasting musical material (omitted from the

example). The rst choral statement (bars 8283) divides into two parts: in the

rst part the chorus (doubled by the brass) intones the words Dies irae on a forte

chord repeated in a dotted rhythm; in the second, the single word irae (chorus

and horns con sordini) is repeated as an echo to a piano chord which bears a

certain afnity with the preceding harmony. The second statement (bar 86) is

limited instead to a repetition of the forte chord on dies illa, and without the

echo response. The third statement (bar 97 onwards) is essentially a recapitula-

tion of the rst, although it presents a slight harmonic departure.Thus, the entire

layer assumes a type of ABA form.

My analytic symbols placed below the score in Ex. 7 show the motivic-

intervallic construction of this layer. The two chords of the rst statement (bars

8283) correspond to the two forms [015] and [016] of the motivic class 15.

Moreover, notice that these forms share the pitches E

and A

, which together

form ic5. The impression that the rst chord is echoed by the second (come eco)

therefore derives not only from the presence of two common tones, but also from

the intrinsic motivic-intervallic afnity of the two harmonic simultaneities. The

second choral statement (bar 86) opens onto a symmetrical sonority, a member

of set class [0156] containing two ic1s and two ic5s. This sonority is obtained

through the sum of the two 15 motives appearing in the two chords of the rst

statement: E

[015] + E

B [016] = E

B [0156]. This time the

chord is not simply repeated: in the middle of the bar, the lowest voice moves a

semitone from B to B

, thereby giving rise to a sonority containing an ic1 (FF

)

and two conjoined ic5s (A

). The recapitulation (bar 97) is practically

identical to the rst statement; nevertheless, in the rst part (the forte chord on

Dies irae), the bass moves a semitone from F

to G. Finally, notice that the

perfect fth A

is a constant presence throughout the layer in its entirety, thus

forming a kind of operative tonal axis.

The sketches transcribed in Ex. 8a and 8b concern the composition of the

same formal layer. Ex. 8a reproduces a strip of paper containing an early version

of the rst statement (bars 8283), preceded by the pre-emptive instrumental

gesture which introduces it (bar 81).

32

Note that in this version the harmony of

the choral part includes a move of a semitone from F

to G in the bass voice, a

solution which Stravinsky will subsequently adopt for the varied recapitulation

(compare Ex. 8a with Ex. 7).

33

Ex. 8b reproduces a little sheet containing two

different versions in the upper and lower systems respectively of the rst and

the second statements, worked out as an unbroken succession. Here the second

statement adumbrates the echo response, which in the nal version Stravinsky

uses only for the rst statement (and for the recapitulation). In the rst version

230 :assi:iLiaNo LocaN1o

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

E

x

.

7

S

t

r

a

v

i

n

s

k

y

,

R

e

q

u

i

e

m

C

a

n

t

i

c

l

e

s

,

D

i

e

s

i

r

a

e

,

b

a

r

s

8

1

8

3

,

8

6

a

n

d

9

7

9

8

:

m

o

t

i

v

i

c

-

i

n

t

e

r

v

a

l

l

i

c

c

o

n

s

t

r

u

c

t

i

o

n

P

i

a

n

o

T

i

m

p

a

n

i

D

i

e

s

i

r

a

e

,

i

r

a

e

,

{

c o m e e c o

C

O

R

O

T

.

B

.

A

.

S

.

C

o

r

.

c

o

n

s

o

r

d

.

I

I

I

.

I

V

I

I

{

T

r

.

I

.

I

I

T

r

b

n

.

I

.

I

I

t

e

n

.

D

I

E

S

I

R

A

E

=

1

3

6

(

=

6

8

)

8

2

D

i

e

s

i

r

a

e

,

d

i

c

o

m

e

e

c

o

{

9

7

{

8

6

d

i

e

s

i

l

l

a

,

C

O

R

O

S

.

A

.

B

.

T

.

T

r

.

I

.

I

I

T

r

b

n

.

I

.

I

I

t

e

n

.

,,

c

o

m

e

e

c

o

{

T

r

.

I

.

I

I

T

r

b

n

.

I

.

I

I

t

e

n

.

C

o

r

.

c

o

n

s

o

r

d

.

I

I

.

I

V

I

.

I

I

I

C

O

R

O

S

.

A

.

B

.

T

.

[

0

1

5

]

[

0

1

6

]

[

0

1

5

6

]

=

[

0

1

6

]

+

[

0

1

5

]

[

0

1

6

]

[

0

1

5

]

E

F

A

E A B

A BE

F

B

E

E

A

A

F

G

B

5

5

5

1

1

1

5

5 1

1

1

1

3

Co:iosiNc wi1n IN1cnvaLs 231

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

of the passage (the upper system), the chord of the second statement is a series

of three conjoined perfect fths (BF

). In the second version (the lower

system) the B is modied to a B

. The alteration forms set class [0157], which

contains two conjoined ic5s (F

) along with an ic1 between B

and C

. In

the nal version, Stravinsky preferred a sonority containing two ic1s and two

ic5s, as we have already seen. In the event, all of the variants in the sketches, like

the nal version, can be interpreted from the point of view of a systematic use of

combinations of ic1 and ic5.

The only serial symbols discernible in the sketches are on the page transcribed

in Ex. 8b and refer to the second of the two fundamental twelve-note rows

employed in the Requiem Canticles,

34

or, more precisely, to the two rotational

arrays generated respectively by the rst hexachord of series I (Ia) and the rst

hexachord of series RI (RIa) of Ex. 8c.

35

Without going into detail on the various

properties of this type of table and the ways of using it,

36

I will briey describe

its construction. The pitches of the original hexachord are rst made to rotate

systematically from right to the left: the rst rotation begins with the second

pitch of the original hexachord, through which the rst pitch moves into the nal

position; the second rotation begins with the second pitch of the rst rotation

(the third pitch of the original), and so on for ve iterations (after which it

returns to the original form). The ve rotated forms thus obtained are trans-

posed successively so that they all begin on the same pitch as the original

hexachord (in the specic case of Ex. 8c, F for the forms generated by hexachord

Ia; G for the forms generated by hexachord RIa). Each of the ve rotated-

transposed forms thus obtained contains the same succession of intervals

Ex. 8a Stravinsky, sketches for Requiem Canticles, Dies irae (compare bars 8183 of

the printed score) (Paul Sacher Foundation, Igor Stravinsky Collection)

B

T

Di es i

3

rae

3

i - [illegible]

S

A

3

3

eco

3

3

Tmp

II Inv.

232 :assi:iLiaNo LocaN1o

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

globally each time beginning at a different point within the succession but

different pitch classes.

37

The symbols on the sketch shown in Ex. 8b clearly indicate that the chords of

the choral part result from the combination of dyads freely selected from the two

Ex. 8bd (b) Stravinsky, sketches for Requiem Canticles, Dies irae (cf. bars 8183, 86

and 9798 of the printed score) (Paul Sacher Foundation, Igor Stravinsky Collec-

tion); (c) rotational arrays of the hexachord a of the inversion (left-hand column)

and retrograde inversion (right-hand column) of twelve-note row II, with encircled

serial segments employed in the upper sketch (the circles and connecting arrows are

not part of Stravinskys original autograph); (d) motive 15, in the forms of sets

[016] and [015]

T

B

II

1

2

inv.

{

{

S

A

Di es i rae, (irae) Di es illa

R inv. 1 (5 & 6)

illa

B

T

S

A

Di es i rae (ir rae) di

R

es

inv. 1 (4 & 5)

illa

(ill a[sic])

1

2

3

4

5

6

1

2

3

4

5

6

[016] [015]

B

C

F

A

D

B

5 5

1

1

Row II

hexachord I

Row II

hexachord RI

st

nd

1

1

st

st

1 & 2

1 & 2 3 & 2 [T ]

1 & 3

2 & 3

11

(b)

(c) (d)

Co:iosiNc wi1n IN1cnvaLs 233

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

rotational arrays (Ex. 8c).

38

In general, the dyads derive from segments of two

consecutive notes within a line of the tables. In one case, they even derive from

two non-consecutive notes (1st, 1 & 3= the rst and third note of the rst line).

In another case, the dyad derived from the third and second note of the second

line (2nd, 3 & 2 = G

) is transposed down a semitone (T

11

), so as to become

GE

. As can be seen, Stravinsky does not seem to have selected the dyads on the

basis of a pre-established criterion or precise order within the table. Rather, it

seems that his only intention was to ensure the production of numerous ic1 and

ic5 relations. These intervals attain a certain importance within the original form

of hexachord a, where they form two motives of class 15, in the forms [016] and

[015], respectively (also shown in Ex. 8d). Moreover, given the structure of the

tables, these intervallic motives also appear in the rotated(-transposed) forms.

This justies Stravinskys recourse to the rotational arrays, but it does not

explain his reason for extrapolating only dyadic segments, rather than complete

hexachordal units. Nevertheless, it is evident that, by operating in this manner,

Stravinsky hoped to obtain a denser and more cohesive motivic construction

than could be achieved using the hexachords in their entirety. Note, for example,

that the two 15 motives interlaced to form the symmetrical set [0156] in

the second choral statement derive from neither hexachord a nor from its

rotated(-transposed) form. This demonstrates that from Stravinskys point of

view serial technique is not essential per se, but instead functions only as a means

to an end with regard to motivic-intervallic syntax. The use of complete serial

forms does not, as a matter of fact, represent a restriction: if necessary, their use

can pass into the background in favour of a more immediate and direct engage-

ment with single intervals.

From Intervallic Motives to Rows

The problem of the interaction between intervallic-motivic logic and serial

technique becomes central in the compositions following Agon, which are sys-

tematically based on the use of ordered pc sets (tetrachords, hexachords, twelve-

note rows, and so on). This interaction can be observed in two distinct

conceptual stages of the creative process: (1) the initial denition of a row of

pitches and (2) the transformation of the abstract row into concrete musical

contexts. In either of these stages, motivic-intervallic logic can take on a role of

greater or lesser importance. In the rst stage, such logic can determine the

physiognomy of the pc sets to be used as primary series. In the second stage, it

can determine the manner in which the rows are manifested musically. The

implicit motivic-intervallic relations in the abstract formulation of the row, in

fact, can be revealed through a variety of devices. These devices can occasionally

elucidate different motivic-intervallic aspects latent in the row, which is then

subjected to a process of continual motivic interpretation.

In each composition, motivic-intervallic logic may be present in one rather

than the other of these two conceptual stages of the creative process. In Agon, for

234 :assi:iLiaNo LocaN1o

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

example, this logic seems to have characterised the pre-compositional stage (that

is, the initial denition of a tone row). Indeed, the majority of the rows employed

in the work demonstrate a very clear and denite motive-intervallic design.

Elsewhere, I have tried to show how the overwhelming majority of rows (ranging

from four to twelve pitches) which in recent studies of the compositional process

have been identied throughout the ballet,

39

from the Triple Pas-de-Quatre

forwards, can be traced back to motivic-intervallic combinations of ic1 and ic2.

40

Consider, for example, the ordered tetrachord <0, 1, 4, 3>, which appears for the

rst time in the Pas-de-Deux: it can be generated by a 121 motive, with the

intervals oriented in the same direction to form set class [0134], by simply

ordering the sounds according to the succession <0, 1, 4, 3> in which the whole

tone is found between the second and fourth notes and the two semitones on

either side. The central position is then occupied by a (non-structural) major

third (Ex. 9).

The majority of the rows (from six to thirteen pitches) employed in the

succeeding movements of the ballet are obtained by combining different state-

ments of this characteristic tetrachord.

41

Consequently, the 121 motive

becomes the generating nucleus for the remainder of the work. Other rows not

based on the <0, 1, 4, 3> tetrachord can still be traced back to a particular

combination of ic1 and ic2. The rst ve notes of the hexachord stated in canon

at the beginning of the Bransle Simple (Ex. 10a), for instance, are formed by a

succession of alternating tones and semitones, interpretable as two 12 motives

united by a common pitch class. In this case, the particular design of the intervals

the rst motive is in the form [013], with the intervals oriented in the same

direction; the second is in the form [012], with the intervals in opposite direc-

tions guarantees that between the highest pitch, D, and the lowest, G, an ic5 is

formed, the same interval as that produced by the concluding B (the only note

which lies outside the 12 pattern) and the preceding F

. This results in a

symmetrical structure, with two ic5s (DG and BF

) at the distance of a

semitone. The twelve-note row employed in the coda of the rst Pas-de-Trois

(presented for the rst time in bars 185189) is entirely formed from a chain of

12 motives in the two forms [012] and [013] (Ex. 10b).

In Agon, the intervallic motives containing the tone and semitone, aside from

generating the majority of the fundamental rows, perform an important role even

in the movements not based on serial technique.

42

Thus their presence imposes

coherence on the work in its entirety, despite the different compositional tech-

niques employed.

43

The passage for the rst violin (doubled by the cello) at bars

Ex. 9 Motive 121 in [0134] form, reordered as tetrachord <0, 1, 4, 3>

121 motive in <0134> form the same reordered as <0143>

1

2

1

Co:iosiNc wi1n IN1cnvaLs 235

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

97102 of the Triple Pas-de-Quatre, for example, derives from a dense chain of

overlapping 212 motives (Ex. 11). The intervallic orientation of the motives is

almost always a zigzag, forming the chromatic set class [0123], but at times (see

the circled motives in Ex. 11) the intervals are oriented in the same direction,

thus forming the set class [0235] (see again Table 2).

44

By comparison with the rows used in Agon, the motivic structure of the

twelve-note rows employed in the compositions which succeed it chronologically

appear to be less well dened. Beginning with Movements, Stravinsky seems to

have derived many of his twelve-note rows from a reading of a concrete musical

idea most often a brief polyphonic passage. This procedure guarantees that the

intervallic motives contained in the initial musical idea are less evident in the

related twelve-note row, in which the structural intervals can be found between

non-adjacent pitches. This creates a sort of circularity between the two stages

into which I have conceptually subdivided the creative process: from a concrete

musical idea comes an abstract row of pitches, and on the basis of this row, new

Ex. 10a Stravinsky, Agon, Bransle Simple (opening): motivic construction

2 1

2 1

5

[012]

[013]

5

Ex. 10b Stravinsky, Agon, twelve-note row of the coda of the rst Pas-de-Trois:

motivic construction

2 2

2

2

2 1 1 1 1 1

5

[012]

[012]

[013]

[013] [013]

Ex. 11 Stravinsky, Agon, Triple Pas-de-Quatre: motivic construction of bars 97102

= 212 motive

[0123] [0123] [0123] [0123]

[0123] [0123] [0123] [0123]

[0123] [0123] [0123]

[0123] [0123]

(C. ni)

[0123] [0123]

[0123] [0123] [0123] [0123] [0123] [0123] [0123]

[0123] [0123] [0123] [0123] [0123] [0123] [0235] [0235]

236 :assi:iLiaNo LocaN1o

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

and different concrete musical passages are realised. In effect, Stravinsky appears

to open up a wider eld of compositional possibilities: if indeed the motivic-

intervallic structure of the resultant row is more ambiguous, the row more easily

presents various musical realisations capable of illuminating different motivic-

intervallic aspects that are implicit within it.

In his last works, Stravinsky hinted at different cases in which the formulation

of a twelve-note row could derive from an initial concrete musical idea.

45

Con-

sider for example the following declaration concerning the composition of

Epitaphium:

I began the Epitaphium with ute-clarinet duet (which I had originally thought of

as a duet for two utes, and which can be played by two utes ... ). In the manner

I have described in our previous conversations, I heard and composed a

melodic-harmonic phrase. I certainly did not (and never do) begin with a purely

serial idea, and, in fact, when I began I did not know, or care, whether all twelve

notes would be used. After I had written about half the rst phrase I saw its serial

pattern, however, and ... began to work toward that pattern. The constructive

problem that rst attracted me in the two-part counterpoint of the rst phrase was

the harmonic one of minor seconds. The ute-clarinet responses are mostly

seconds, and so are the harp responses, though the harp part is sometimes

complicated by the addition of third, fourth and fth harmonic voices. (Stravinsky

and Craft 1960, pp. 99100)

Assertions of this sort often nd conrmation in the sketches of the compo-

sitions from Movements onwards, where one encounters some melodic or con-

trapuntal annotations which probably served as the model for the formulation of

the rows.

46

A circumstance of this kind probably explains the origin of the two

twelve-note rows employed in the Requiem Canticles, which Stravinsky explicitly

attributed to some intervallic designs which I expanded into contrapuntal

forms.

47

The intervallic designs to which this quotation alludes can be found

among the sketches for the instrumental Interlude which in actuality was the

rst movement in chronological order of composition.

48

The amount of preparatory material which survives for the Interlude is

uncommonly large, considering the Stravinskian standard: more than twenty

small sheets and strips of paper of different sizes, forms and typologies for a

passage lasting only 67 bars.

49

Some sketches contain only one or two brief

musical phrases, mostly corresponding to the exposition of a single form of row

I or row II (or of one of their constituent hexachords). Other pages assemble

their content from various earlier sketches. The nal form of the passage thus

results from a sort of montage of single ideas which had been elaborated

individually in the rst stages of composition. Comparison of these versions,

together with analysis of the various written materials employed and the auto-

graph dates placed by Stravinsky on some pages, allows for chronological recon-

struction of the sketches for the Interlude with a good degree of certainty.

50

One

of the very rst ideas notated by Stravinsky is reproduced in Ex. 12a. It is formed

Co:iosiNc wi1n IN1cnvaLs 237

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

from the union of two brief contrapuntal phrases based on the two original rows

employed in the movement, as indicated by the autograph serial symbols.

51

The

two phrases, initially notated separately on two small clippings of paper, were

then pasted onto a piece of cardboard (the continuity between the two phrases

is indicated by Stravinskys autograph arrow).

52

These phrases correspond

respectively to bars 161162 and 173175 of the score, of which the clippings

preserve a very rudimentary version. In the following sketches, Stravinsky added

new musical material between the two phrases, which are at the same time then

gradually reshaped. To this extended musical passage thus obtained (bars 163

172) Stravinsky subsequently added bars 176192, thus creating the entire

episode for four utes (bars 161192), the largest and most important formal

section of the piece. In summary, it seems that the two musical ideas contained

in the sketches transcribed in Ex. 12a were indeed the point of departure in the

composition of the Interlude. If this is so, they may well feature the original

intervallic designs to which Stravinsky alludes in the statement quoted above. In

fact, the contrapuntal relations of the two musical phrases illuminate a very clear

Ex. 12a Stravinsky, sketches for Requiem Canticles, Interlude (Paul Sacher Founda-

tion, Igor Stravinsky Collection)

II

[ ]

0

3

I

0

Ex. 12b Motivic analysis of the musical ideas contained in the sketches of Ex. 12a

3

F

C

B

D

A

A

D

F

G

C

G

E

F

G

E

F

F

D

E

C

B

C

D

C

B

A

G

A

[016] [015] [013] [013] [013] [012] [013] [012]

1

2 2

1

1

2 2

1

1

1

1

2

1

2

1

5

5

5

1

5

5

1

238 :assi:iLiaNo LocaN1o

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

motivic-intervallic construction, based on the 12 and 15 motives (Ex. 12b).

The triplet in the rst crotchet of the second phrase, shown on the right in

Ex. 12b probably composed rst

53

presents within itself a sort of polyphony:

the lower part, delineated by the pitches FGE placed in the same register,

produces a 12 motive; the D

of the upper part forms, however, a relation of a

semitone with the lower E. By holding these two pitches rm and adding the F

,

another 12 motive is obtained in the second crotchet of the phrase, this time

vertically (D

EF

). Furthermore, the two motives (EFG and D

EF

) are

separated by the distance of a semitone. In the remaining part of the phrase,

three overlapping 12 motives, in both [012] and [013] forms, are unfolded

horizontally. In the rst phrase (reproduced on the left in Ex. 12b), the rst two

vertical simultaneities of three pitches form two motives of class 15 respec-

tively in the forms [016] and [015] while the following group of four pitches

delineates a cycle of three ic5s (C

), divided symmetrically into two

(F

in the bass; G

in the upper parts). The last vertical sonority of three

pitches (F

EG) forms a 12 motive which creates a strong link with the

following phrase, beginning with the motive FGE, another member of the 12

motivic class. The link illustrated also by Stravinskys cue in the upper right-

hand corner of the rst sheet of Ex. 12a is reinforced by the presence of pitch

classes E and G in both of the motives.

The intervallic designs contained in the two ideas thus become relatively

clear. We might ask at this point which came rst, these two musical ideas or the

two twelve-note rows whether, in other words, the rows were obtained from the

musical ideas or could instead have been xed in advance as an abstract

sequence of pitches on the basis of which the musical ideas were subsequently

elaborated. The fact that the two musical ideas contain all twelve notes without

repetition does not mean we must prefer the second solution: generally speaking,

in fact, we may suppose that Stravinsky initially elaborated his musical ideas

following a predominantly motivic-intervallic logic, and although even at this

stage of which, however, hardly any written traces remain he tended to exploit

all twelve notes of the chromatic gamut, that did not prevent him from using

some pitches more than once. Only in the nal formulation of the idea were the

repetitions eliminated until a fundamental twelve-note row was obtained. This is

clearly demonstrated by an important document to which Joseph Straus has

drawn attention:

54

the photographs taken in 1967 by Arnold Newman in Stravin-

skys Hollywood studio.

55

Like the stills of a lm, Newmans photographs record

step by step the creation of a musical idea a brief instrumental passage and

its successive transformation into a twelve-note row.

56

According to Straus, the

musical passage reveals, above all else, some semitone-tone motives belonging to

set class [013].

57

From my point of view, conversely, the rethinking which took place in the

course of elaboration was determined by a motivic idea of the semitonemajor

third type (14) in its two possible forms, [014] and [015]. In the very rst bar,

Stravinsky notated a portion of an Allintervallreihe (all-interval row; Ex. 13a) as

Co:iosiNc wi1n IN1cnvaLs 239

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Straus also observes. In the next stage of composition (Ex. 13b), he abandoned

this initial idea to compose a brief counterpoint between two voices, without

attempting to avoid the repetition of pitches (note the initial pitches B and C,

repeated at the close of the passage). The third stage reveals the rst signicant

stage of rethinking: comparing Ex. 13b with Ex. 13c, observe that Stravinsky

replaces the rst of the two Cs with an E

, thus avoiding the presence of

repetition. The choice of E

throws light on the motivic-intervallic logic which

guides the composition of the passage: the rst three notes of the viola (BE

)

now form a motive of the semitonemajor third type (14). This motive in its

two forms, [014] and [015] appears at numerous other points within the

passage: in the rst ve notes of the viola part (twice: BE

and B

A, with

B

in common); in the last three notes of the cello (B

F), grouped together

as a triplet; between the rst two notes of the viola (BE

) and the D of the cello

which follows immediately afterwards (a semitone lower); and nally in the

contrapuntal relationship between the B

of the viola and the D of the cello

(Ex. 13f).

There is a second signicant redrafting at the following stage (Ex. 13d), where

Stravinsky replaces the rst and the third notes of the viola (B and B

), both

repeated, with G and A

respectively. By making this adjustment, Stravinsky not

only obtains all twelve notes without repetition, but also preserves intact the

Ex. 13ag See Arnold Newmans photos, reproduced in Craft (1967), pp. 1415 and

1617. The sequence of photos goes across the volumes two-page spreads of the

sketches; photos 1 and 2 are on p. 14, photos 3 and 4 on p. 15, and so on

(a) stage 1

(cf. photos 110)

(b) stage 2

(cf. photos 1113)

(c) stage 3

(cf. photos 1417)

(d) stage 4

(cf. photos 1820)

(e) analysis of stage 5

(cf. photos 1825)

(f) analysis of stage 3

(g) analysis of stage 4

3

3

[3]

3

[3]

inverted

[025] [027]

D

G

E

A

D

E

5

5

2

2

3

[014] [015] [014] [014]

B B B A

D D E

E

B D D B

4

1

1

4

4 4

1

1

[3]

[015]

F

G

B

4

1

3

[015] [015] [015]

D

E

G A

G

E A

D

D

1 1

4

1

4 4

[3]

[015]

F

G

B

4

1

240 :assi:iLiaNo LocaN1o

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

motivic construction of the passage, which remains based on the conspicuous

presence of a 14 motive now in the form [015] (Ex. 13g).

The third and nal phase of development occurs in the nal stage (Ex. 13e),

at the end of which Stravinsky obtains a twelve-note row, arranging in succession

the notes of the passage just composed.

58

Here a small adjustment in the order

of the pitches sufces to mask the original motivic-intervallic aspect of the

passage while at the same time illuminating a new one. The second and sixth

pitches (E

and E

) are inverted (see the circled notes in Ex. 13e). Thus, the rst

two segments of three pitches (GED and A

) become two motives of the

class 25. Moreover, the four segments of three pitches which form the row

delineate a symmetrical structure: the combination of the even-numbered seg-

ments forms a partial circle of fths from G

to F, while the combination of the

odd-numbered segments forms the remaining part of the circle (from C to B):

59

1. E

(segment 2) + B

F (segment 4) = G

F;

2. GDE (segment 1) + ABC (segment 3) = CGDAEB.

In the end, the simple exchange of E with E

in the nal row creates, in this case,

a marked estrangement of the motivic-intervallic construction of the original

musical idea.

60

From the Row to Intervallic Motives

At this point it is worth reecting on the ways in which motivic-intervallic logic

inuences the musical concretisation of the row, once it has been denitively

established. I will rst consider a brief musical fragment drawn fromthe beginning

(bars 4648) of the second of the ve Movements (Ex. 14a and b).

61

The passage

is based on the two discrete hexachords (labelled a and b) of the fundamental row

Ex. 14a Stravinsky, Movements, ii: hexachordal forms employed in the sketch shown

in Ex. 14b

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2 3

3

3

3 4

4

4

4 5

5

5

5 6

6

6

6

[016]

[016]

[012]

[012] [012]

[012]

[016]

[016]

Hexachord

Hexachord

RI (T )

R

6

Co:iosiNc wi1n IN1cnvaLs 241

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

used throughout the entire composition (Ex. 14a, rst and third lines). In the

upper part of the sketch transcribed in Ex. 14b, Stravinsky wrote the RI (T

6

) form

of hexachord a and the R form of hexachord b (Ex. 14a, second and fourth lines)

as indicated also by the autograph labels Riv-Inv a and Riv b.

62

As my analysis in Ex. 14a shows, hexachord b can be divided into two

trichords belonging to set class [012], which can in turn be related to motive

class 12 (see again Table 1). Hexachord a is formed by two trichords of set class

[016], which can be related to three different intervallic motives: 16, 15 or 56.

In this case, Stravinsky clearly placed the intervals of a semitone and perfect fth

(motive 15) in relief. To this end, a particular permutation of the order of the

pitches of hexachord a is carried out:

63

besides placing the pitches in reverse

order (from the sixth to the rst), he also reversed the order of the rst two

pitches of each trichord. In this manner the pitches which form ic5 (represented

in bold in the schema below) are always adjacent:

654/321 becomes 564/312

(GF

C/DD

becomes F

GC/DA

).

The purpose behind this particular reordering can be appreciated in the

musical passage outlined in the sketch transcribed in Ex. 14b, immediately

below the two hexachords: the pitches which form ic5 are arranged vertically as

a perfect fth; the pitches which form ic1 precede the fth in a register at the

distance of an octave. The two fths (CG/D

) are separated by a semitone,

thereby producing a symmetrical conguration. All these choices are clearly

intended to throw the ic1 and ic5 into relief.

Ex. 14b Stravinsky, sketches for Movements, ii (cf. bars 4648 of the printed score)

(Paul Sacher Foundation, Igor Stravinsky Collection)

5 6 4 3 1 2

6 5 4 3 2 1

6

4

3

1

2

5

2 3 4

6

5

1

Riv.

Riv

Riv- Inv

Riv-Inv

242 :assi:iLiaNo LocaN1o

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

This brief example shows how some operations which alter the physiognomy

of the row were intended by Stravinsky to facilitate the transformation of an

abstract row in a specic musical passage which highlights some particular

motivic-intervallic characteristics. One such operation is order permutation, as

we have just seen; another consists of extrapolating small segments, usually of

two to four notes in length, and successively reconguring them. This technique,

which I call serial fragmentation-recombination, was probably adopted for the

rst time by Stravinsky in Threni and was subsequently used in an increasingly

sophisticated fashion.

64

We have already observed one application, albeit a rather

limited one, in the Dies irae of the Requiem Canticles. To further illustrate its

function in relation to the motivic-intervallic syntax, I will now consider its use

in the rst part of the Rex tremendae of the Requiem Canticles.

The serial construction of the passage is clearly illustrated on the rst page of

the autograph short score (containing bars 203208), transcribed in Ex. 15a.

65

The symbol I Ra stands for row number I, retrograde form, hexachord a. The

Ex. 15a Stravinsky, rst page of the short score for Requiem Canticles, Rex tre-

mendae (compare bars 203207 of the printed score) (Paul Sacher Foundation, Igor

Stravinsky Collection)

B

6

T

8

Rex

4

vla

vc

cb

A

Rex

1

3 Fl

4 5 6

S

I R

Rex

3

Rex tre

men

Verticals

dae ma je sta tis

1 2 3

I

4

inv

5

3

6

rd

3 Fl

[ ]

th

R 5

[ ]

I inv 1 line

st

vc

I inv 4 line

th

3 line

rd

I

3 4 5

trmb

6 line

th

5

th

5 4 6

4 5 6

R 1

st

Strings

vlc

3 line

rd

Co:iosiNc wi1n IN1cnvaLs 243

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

circled numbers at the beginning of each choral part in the short score indicate

the lines of the rotational arrays of the rst hexachord. Only limited portions

(three to ve notes) of each line are used (shown circled in Ex. 15b). The zigzag

line traced across the choral parts

66

corresponds to the brass part (trumpet and

trombone) elaborated on the lower portion of the page. The autograph symbols

indicate that even this line was obtained by the combination of three serial

segments drawn from the two rotational arrays of the R hexachords. For

example, the symbol Ra 5th 3 4 5 stands for retrograde, hexachord a, fth line

of the rotational array, notes 345 (see also Ex. 15b, where the segments used

in the brass part are indicated within boxes). In sum: the rst three bars

67

of the

choral part and the brass parts are obtained exclusively through a combination

of serial segments extrapolated by two rotational arrays produced by hexachords

a and b of the retrograde form of row I. As in the case of the Dies irae, the

segments are selected in an apparently arbitrary manner. Nevertheless, they

demonstrate a signicant presence of motives of class 12: four of the ve

segments of three-note segments (Ra 1st 46, Ra 4th 46, Ra 5th 35, Ra 6th

46 and Rb 5th 46) directly correspond to this motive class; one of the two

segments of ve notes (Ra 3rd 26) contains two overlapped 12 motives

(C

C + CBA); and the other (Ra 1st 15) begins with a 12 motive. The

reason for this arrangement was Stravinskys desire to create an imitative texture

based on the motivic-intervallic element: at regular intervals of a minim the

contralto, the trombone, the sopranos and the tenors display motive 12; but

because this motive can assume two different forms [012] and [013] and

given that the three pitches can be combined in any order, the imitative responses

repeat neither the same melodic prole (as in traditional imitative style) nor the

Ex. 15b Stravinsky, Requiem Canticles, twelve-note row I: rotational arrays of the

hexachords a and b of the retrograde form, with encircled serial segments employed

in the sketch of Ex. 15a

1

2

3

4

5

6

Row I Retrograde

244 :assi:iLiaNo LocaN1o

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

same set class. Therefore, motive 12 is repeated three times in the brass part

which runs throughout the choral passage. Note also that the initial pitches of

each imitative part (A

) gradually take the form of a sequence of

perfect fths (F

), which is completed in bar 3 with the addition of

the pitches G

and C

in the bass part.

This homogenous motivic design is due largely to the structure of the row

itself. Indeed, it should be evident that numerous 12 motives are already

contained in row I of the Requiem Canticles (see again the right-hand section of

Ex. 12b). Nevertheless, by segmenting the hexachords selectively, Stravinsky

created an imitative texture which was more coherent than would have been

possible had he used complete hexachords. One might ask in what sense and to

what degree such a procedure could be dened as authentically serial. However,

the fact that the composer had indicated the serial origin of the various segments

in the short score demonstrates that he conceived of the row as a reservoir of

motivic-intervallic material, and that he understood serial technique as a means

of managing this material systematically.

The beginning section of the rst of the ve Movements (see again Ex. 6)

is likewise based on a systematic application of serial fragmentation-

recombination. The passage divides into an initial introduction (bars 16) and

three solo episodes for, respectively, piano, rst ute (accompanied by piano and

clarinet) and piano again (accompanied by strings). The central ute solo is very

familiar to Stravinsky scholars; indeed, the composer himself drew attention to

its complex serial construction, thereby instigating a long series of attempts at

analysis.

68

As I will try to show, a motivic-intervallic approach can provide a new

and logical key to reading the passage.

To this end, it is useful to begin with the subset structure of the two hexa-

chords of the fundamental row (Ex. 16). The rst hexachord is formed by two

disjunct trichords belonging to set class [016]. In the middle, starting with the

third note, one nds a trichord of set class [012].The second hexachord contains

two disjunct trichords of set class [012] and one [016] trichord at its centre, thus

complementing the rst hexachord. Other interesting properties of the two

hexachords emerge when one takes into consideration their rotated forms.

Ex. 17 cites one of the rotational arrays employed by Stravinsky for the compo-

sition of Movements: columns a and b contain the rotated forms of the two

hexachords of the original form of the row; columns g and d display the rotated-

transposed forms. Ex. 18 reveals the subset structure of all these rotated

(-transposed) forms. Eight of the twelve hexachords contain within them three

Ex. 16 Stravinsky, Movements, i: subset structure of the original twelve-note row

Orig.

[016] [016] [012] [012]

[016] [012]

Co:iosiNc wi1n IN1cnvaLs 245

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Ex. 17 Stravinsky, Movements, sketch showing the rotated (columns a and b) and

rotated-transposed (columns g and d) forms of the two hexachords of the original

twelve-note row (Paul Sacher Foundation, Igor Stravinsky Collection)

I

II

III

IV

V

Ex. 18 Stravinsky, Movements: subset structure of the rotated-transposed forms of

the two hexachords of the fundamental row

Orig.

I

II

III

IV

V

[016] [016] [012] [012]

[016] [012]

[016] [012]

[012] [016]

[016]

[012]

[012]

[016] [016]

[016] [016]

[012]

[012]

[016]

[012]

[016]

[012] [016]

[012]

[012] [012] [016] [016]

[016]

[012]

[012]

[016]

[016]

[012]

[016]

[016]

246 :assi:iLiaNo LocaN1o

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

trichords belonging to set class [016] or [012]; two hexachords (IIg and IIIg)

contain four which closely overlap with one another. The remaining two hexa-

chords (Id and IVd) contain two each.

It is evident, therefore, that the internal structure of the two hexachords is

such that the rotated forms generate a large number of trichords belonging to set

classes [012] and [016]. Now, set [012] can be understood solely as a 12 motive

with the intervals arranged in opposite directions,

69

while set [016] could be

associated with three different motives: 15, 16 or 56 (see again Table 1). A

deeper analysis will clarify which of these intervallic motives was the object of

Stravinskys interest.

With the aid of the sketches, I have reconstructed the chronology and serial

origin of the three episodes which form the entire section, summarised in

Table 3.

70

As can be seen, all three episodes are based on a combination of serial

segments chosen from columns g and d of the rotational array. The serial

segments employed for the second episode, the ute solo (bars 1317), are

indicated in the sketch transcribed in Ex. 19a; the symbols here refer to the

sketch with the rotational array transcribed in Ex. 17 (the Greek letters refer to

columns g and d of the array and the roman numerals to the lines; the arabic

numeral indicate the selected segments). The 34 notes of the ute melody

(Ex. 19a) are obtained by combining ten serial segments, freely chosen from the

array (Ex. 19b). In the nal version (Ex. 19c), the melody thus obtained was

completely transposed a major third higher (T

4

) to start on G instead of E

. In the

third episode (bars 1822; see Ex. 20) the piano and string parts employ the

same serial segments as the ute solo, as is suggested by the serial symbols and

the indication follow the ute solo before (same series) in the short score;

however, this time it is not transposed (compare Ex. 20 with Ex. 19b).

The rst episode (bars 712; Exs. 21 and 22) is essentially based upon the

same succession of serial segments, even if in the nal version the resulting

correspondence is obscured owing to some errors Stravinsky committed in the

Table 3 Chronology and serial origin of the three episodes in Stravinskys Movements,

i, bars 722

Episodes (in chronological order) Twelve-note material employed

bb. 1317: second episode

(solo for ute I)

Serial segments drawn from columns g and d of the

rotational array of the hexachords. The entire

succession is transposed T

4

to G. The accompaniment

uses complete hexachords.

bb. 712: rst episode

(rst solo episode for piano)

The same serial segments from the ute solo but

transposed T

2

(on F).

bb. 1822: third episode

(second solo episode for piano)

The same serial segments from the ute solo, not

transposed (on E

).

Co:iosiNc wi1n IN1cnvaLs 247

Music Analysis, 28/ii-iii (2009) 2011 The Author.

Music Analysis 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

preparation phase. On the rst two lines on the page of sketches transcribed in

Ex. 21, up to the pitches BCD

before the notated clefs, the composer had