Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

AMERICA'S EDENIC REGENERATION IN BLADE RUNNER

Enviado por

Bryan GraczykTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

AMERICA'S EDENIC REGENERATION IN BLADE RUNNER

Enviado por

Bryan GraczykDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES

19

FIERY THE ANGELS FELL: AMERICA, REGENERATION, AND RIDLEY SCOTT'S BLADE RUNNER CHRISTIANE GERBLINGER Fiery the Angels rose, & as they rose deep thunder roll'd Around their shores: indignant burning with the fires of Orc And Boston's Angel cried aloud as they flew thro' the dark night.1 Ridley Scotts Blade Runner indicates that the only possible path for the evolution of humanity to take is a regenerative one, specifically, by renewing earlier human precedents in an Edenic America. When the film was released in 1982, the United States was experiencing the economic policies of Reaganomics. By the time of the films March release that year, Reagan had begun implementing cuts in education, welfare, and housing, he had increased defense spending, and had survived an assassination attempt. In the same year, Sylvester Stallone began his meteoric rise as Vietnam veteran John Rambo in First Blood. Like Nixon before him, taken by George C. Scotts portrayal of General Patton to the extent that he decided to invade Cambodia,2 Ronald Reagan was so impressed by the revisionism personified in the warrior-hero figure of action and war cinema that he proclaimed he would send Rambo abroad in any future international emergencies.3 With this statement, and others like it,4 Reagan gave voice to a Vietnam myth that primarily had its foundation in the much older, and equally unfounded, archetype of the American warrior, effectively creating a cultural climate in which 1980s America was characterized not by progress but by a valorization of regression. Because of a monumental and unprecedented moment of failure in its history, then, the progress of America lay in its past: it had to go back, at the very least, to the days before Vietnam. To go forward, therefore, vitally depended upon going back. In this essay, it is argued that Scotts Blade Runner, although an unconventional film in many ways, is a product of this logic of regression in its suggestion that the preferable path for the development of humanity to take is a regenerative one. Viewed thus the film prompts one to make the point that the world beyond its technopolis is the same Edenic New World as Americas fantasy past. To more fully understand Blade Runner's regenerative motif it is important to explore two specific themes that are raised by the film and which most significantly represent the sequence of creating anew from remnants of the old. Firstly, by opening an interpretive panorama on the word to fall, the film offers a view of evolution through the attempt to rebel against the status quo; and secondly, the prelapsarian archetypal configuration of Adam and Eve is reinterpreted by placing the regenerated self in an environment which holds

20

AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES

the promise of a renewed New World. To establish the first theme raised by the motif of regeneration in Blade Runner, it is important to consider the difference between the film's humans and its replicant humanoids. When Roy Batty, the principal replicant played by Rutger Hauer, is first appraised by Blade Runner's camera, he quotes from Blake's 1793 America, A Prophecy. He deliberately misquotes the section he cites: Fiery the angels fell; deep thunder rolled around their shores, burning with the fires of Orc. Very few commentators have noted this literary allusion, with the notable exception of Robin Wood, who suggests that, read against its original (which has here been cited in an epigraph), the near-quotation discloses the end of the American democratic principle of freedom, its ultimate failure,5 a claim which he says is supported by the film's visual imagery that links Roy with the disintegration and urban squalor that surround him. While Wood is right to connect the word to rise with the birth of the new nation, his conclusion that falling must be the end of this nation may be too reductive a reading. Roy Batty, the leader of the other Nexus 6 androids, could well be an interpretation of Blake's Orc, who heralds revolution, the cessation of restraint, and the inception of a new existence. By inserting lines from Blake's poem, Scott may have intended to signal that Batty is possessed by the spirit of Orc, and thus by the spirit of rebellion. Wood's suggestion that to fall to earth is to symbolize the cessation of a democratic commitment to freedom is simply too narrow a reading of Blade Runner's mise en scne. After all, Blake's poem does not merely describe the end of British oppression in the American colonies, but also celebrates America's struggle and its Declaration of Independence -- its beginning as a democratic nation. Scott's importation of Blake, and hence (consciously or not) of a particular revolutionary mood, thus invokes a similar, and very substantial, mood of change, of an inception into a new mode of existence, and of a liberation from servitude and oppression. Although the cityscape of Blade Runner is indeed a disintegrating one, and the words rise and fall are opposites, Blake toyed with opposites and contradictions throughout his career, and imbued Milton's morally ambiguous fallen angel Satan with an unequivocally attractive personality. Scott may have been aware of this system of subversion through inversion when he (and scriptwriter David Peoples) chose to insert the excerpt into the script - it's not in Philip K. Dick's Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, the novel upon which Blade Runner is based.6 Illegal on earth, the replicants descend onto LA, the city of angels,7 from above in order to meet their maker. The reversal of direction is necessary. Indeed, when Blake's angels finally land on American soil, they, too, descended/Headlong from out

AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES

21

their heav'nly heights, descending swift as fires/Over the land.8 Above the land hovers Urizen, who -- arguably -- is Blake's version of a dogma imposing reason and restraint,9 and resides in a holy shrine, over the hills, the vales, the cities and above all heavens, in thunders wrap'd.10 This figure finds its echo in Tyrell, head of the corporation that manufactures Nexus 6 replicants for off-shore exports, and who, from his temple above the city, also appears to control the human society that remains on earth. This controlling force in Blade Runner imposes its politics by way of a rhetoric of nature, and a subsidiary economic determinism intended to suppress both autonomous consciousness in labouring machines and independent critical thinking in their human counterparts. First, though, this imperialism is made possible by the authentication that comes with the act of production. As Marx and Engels proposed, production raises those who produce above that which they produce.11 In the case of Blade Runner, a similar logic ensures that the status quo not only remains anthropocentric but that it can also be manipulated to distinguish between origins, cultures, and, here, genetic codings. Scott's film retains the novel's system of establishing the difference between human and replicant: the Voigt-Kampff empathy test. The use of this mechanical empathy test to identify mechanical humans betrays a deep confusion about how humans are managing to identify themselves. To reduce this tenuousness in states of identity, and to create a zealous and vehement certainty about what constitutes the human, labouring humanoids are shipped to off-world colonies and programmed to expire after four years. Not only does their construction ensure that humans feel human, their subsequent status of virtual invisibility also protects humans from ever doubting their own humanity. The possibility that the human, normality, and nature have not actually been fathomed at all but are tentative is neutralized by way of both the construction and the subjugation of a genetically engineered doppelgnger . The governing body of Blade Runner's social universe, represented by the Tyrell Corporation (in charge not only of manufacturing androids, but of emigration to the New World and the commercial enterprises that either enable or disable one's means to re-settle), thus controls human self-perception to a repressive degree. Speaking of the motif of repression in the horror film of the seventies, Robin Wood also suggests that what is generally repressed in twentiethcentury Western culture is sexual energy, the source of creative energy. Its repression is usually enforced in the form of monogamous heterosexual union and non-creative, non-fulfilling labour. The ideal member of such a society, he claims, is as close as possible to an automaton in whom both sexual and intellectual energy has been reduced to a minimum.12 This

22

AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES

might be the crux of the films version of capitalism, that is, by giving humans a new class to oppress, they are easily controlled because they regulate their own repression. Taking his impetus from Barthes' Mythologies, Robin Wood goes on to give an apt example of self-repression through oppression. He suggests that if the other cannot be annihilated, a dominant norm, such as bourgeois ideology, renders it safe and assimilates it by converting it as far as possible into a replica of itself.13 By making replicas of itself to neutralize allogenous forces, Barthes further suggests, bourgeois ideology transmogrifies into an original, thereby producing the myth of an unchangeable nature. In so doing, the bourgeoisie transforms the reality of the world into an image of the world, History into Nature, thus emptying reality of history and filling it with the notion of nature.14 In the context of Blade Runner, we might say that by creating androids, the Tyrell Corporation has assimilated human diversity, and, with it, the possibility of social upheaval, into replications of human obedience. In a world and a reality seemingly without natural environments,15 this creation assures that the process of history is replaced by a contrived progress of nature, and, in turn, that only the natural (the human) can contain a history. This is the crux of human self-repression and android oppression in the film. But when Roy and his fellow-replicants fall to earth, they do not descend into humanity, but rather challenge its constitution by the mere fact that they embody all the elements of what has been repressed. Above all else, the replicants' increasing consciousness culminates in an autonomy their human superiors surrendered long ago, and which is embodied by Roy's misquotation of Blake's words. The fact that Roy utters them both as an ironic memorial to his mutiny and as a prelude to what's to come implies very strongly that he is exerting his autonomous will by appropriating an event in human history in order to shape his own history and future. Whoever directed him, in other words, would have programmed him to quote poetry correctly -- by affecting fallibility, Roy's misquoting suggests that he is willfully attempting to shed his status as a perfected mechanism manufactured to maintain the repressive mimicry of history as exclusively natural. In so doing, he alters an image of the world into a revision of nature based on personal history. Shapiro has noted that the utterance is an instance of Roy's subtle manipulations of the discursive spaces that control meanings.16 This underscores the suggestion that the discourse of an unchangeable nature can be used to legislate a particular history. Further, it suggests that Roy is very much aware of the paradigmatic construction he has been created to maintain.17

AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES

23

But the creative misquotation has a further resonance, because the narrative of Blade Runner itself is essentially about a point of transit, simply a moment in the regeneration from simulacrum to self-conscious individual, and from labouring property to autonomous subject. The assertion of such autonomy is highly evocative of the Fall of Adam and Eve, made more so, surely, by Batty's and thus the film's use of the word to fall itself. The Fall of the Old Testament has been linked, especially since the Romantic movement, to autonomous will and a rejection of an extraneous plan. As John A. Phillips reminds us, for writers such as Schiller and Kant, the Fall represents an enormously productive moment in the history of civilization -the felix culpa.18 The Fall is happy because with autonomy comes the capacity of causing and shaping one's existence, and because it engenders the democratic assignation of each individual's equality. This allusion to the Fall and the Old Testament may also imply that the return of the repressed is a confrontation with a mythical, perhaps even primeval, realm, as might be ascertained from the Directors Cut sequence of the unicorn. When Deckard dreams about the unicorn, he dreams of a fabled and rare nature based upon mythology. While this perplexing scene has been taken as a metaphor for Rachels uncertain future, and as a suggestion that Deckard is the sixth replicant19, it seems equally likely that Deckard recognizes his hunt for the replicants as a catalyst for the extinction of a species threatened with an already precarious existence. Yet by assuming this existence himself when he flees with Rachel, he not only forges new ground, he also embraces a mythological, even prelapsarian, aspiration for humanity. In Blade Runner, true to the counter-culture that informed much of Philip K. Dicks 1960s original, going forward entails going back. For all its futuristic imagery, and because of its transparent approach towards progress as regeneration, Blade Runner deals in conventional and archetypal configurations, which constitutes the second, and perhaps more substantial, of the two themes arising from the films motif of regeneration. Even though the film is radical to some degree in that it allows the replicants to form the foundation of Deckards eventual aspirations it fails to find an entirely new direction for its final couple to take. Instead, it seems to mirror the historical vacuum America appeared to inhabit during the 1980s. Despite the fact that the replicants transform the notion of a superior and regulative nature into their own personal history, the film seems to reinstate a foundational and utopian new world as the New Worlds telos. The retrogressive position of this utopian world (or, at least, the promise of it) somewhat undermines the films otherwise radical exploration of the possibility of an emerging fusion of nature and technology.

24

AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES

The utopian aspect of myths of regeneration seems to be at its most optimistic in late twentieth-century reconfigurations of the myth of the American Frontier, where both idealized origin and desired destination are interdependent and constantly on the threshold of attainment.20 As Richard Slotkin points out in Gunfighter Nation, [a]lthough myths are the product of human thought and labor, their identification with venerable tradition makes them appear to be products of nature rather than history.21 This goes some way to explaining why 1980s narratives so often evoke the frontier myth in response to the historical fact of Americas loss in Vietnam. The reality of Americas involvement in Vietnam and its aftermath has effectively been revised to correspond with how events should ideally have transpired. Americas image of itself is rooted in a myth of nature, within a framework of a venerable tradition of paradisiacal magnificence. In this sense, the myth of nature replaces the reality of past events by reclaiming Americas innocence and moral righteousness from the peril of depravity. Because the ideal state posited by the myth is never quite attained, the myth is reiterated in popular culture during the 1980s as an ongoing replay of Americas mythologisation of Vietnam, particularly, though by no means exclusively, in intergalactic utopian science fiction, such as Lucas original Star Wars trilogy, as well as the Star Trek movies of that decade. As Slotkin observes elsewhere in his book, the 1980s saw Ronald Reagan becoming the chief spokesman for a revisionist history of Vietnam, which was reflected by the concentration of Hollywood genre-films on the captivity formula that linked them to the most basic story-form of the Frontier Myth, while their obsessive repetition of the rescue fantasy makes them seem like rituals for transforming the trauma of defeat into symbolic victory.22 While it would be difficult to claim that Blade Runner is either a movie that consciously perpetuates Americas cult of Vietnam or even that it is a nostalgia film of the sort described by Fredric Jamesons 1982 essay Postmodernism and Consumer Society,23 it contains significant elements of the Frontier myth in its allusion to a New World in which, as one of the films many billboards advertises, to begin again. With its involvement in such mythology, it does share one aspect of the nostalgia film, in that it represents what Jameson calls an alarming and pathological symptom of a society that has become incapable of dealing with time and history.24 Thus, whether one chooses the Directors Cuts uncertain future, or the original release versions escape into ecological paradise, each represents a utopian aspect of the regenerative motif that is radically subversive of the elements

AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES

25

that constitute living beings and their rights and as conventional as Adam and Eve in the garden of Eden. With their escape, Rachel and Deckard leave behind the regulated programs for which they were destined, to enter the unknown, a new world in which to begin again. Reminiscent of Mary Shelleys monsters intention to leave for the vast wilds of South America,25 Deckards and Rachels flight represents the potential for the realization of a new beginning. The compound effect of Deckards union with Rachel in a new world and the original films departure into the American wilderness means that Deckard can easily be read as an allusion to the American Adam. America, as it has popularly been depicted, is both subject and host to the notion of a New World. As R.W.B. Lewis has claimed, America was not the end-product of a long historical processit was something entirely new.26 Thus, as Blakes poem has already suggested, America was not a climactic conclusion to a chapter in European history, but a new beginning altogether. As Lewis continues, [t]he new habits to be engendered on the new American scene were suggested by the image of a radically new personality, the hero of adventure: an individual emancipated from history.27 Blade Runner s ideal of creating an entirely new history (based on a merging of human and android existence) is particularly evocative if read as a reworking of the notion that America represented the possibility of becoming emancipated from previous (human) history. In this case, Deckard is this new historys first man. The pattern this reading refers to is an inherently contradictory one, that is, the idea that a new history can install an archetypal, Adamic figure is fraught with paradox. As Lewis has famously encapsulated the problem, the notion of primitive Adamic perfection and progress toward perfection were current, and they overlapped and intertwined. On the whole, however, we may settle for the paradox that the more intense the belief in progress toward perfection, the more it stimulated a belief in a present primal perfection.28 Although Lewis is speaking of the nineteenth century, his statement could equally be applied to the twentieth, at least where America and the perpetuation of its central national mythology were concerned. The dynamic created by the juxtaposition of the old with the new, of a New World that is also ancient, is why Blade Runners connection of Deckard with the first

26

AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES

man in a new world to Adam in the garden of Eden virtually guarantees that the original films utopian ending will transport its protagonists to a destination derived from origins. Yet even the Directors Cut of 1992, shorn of the pastoral ending and much more ambiguous than its predecessor, conveys elements of origin and destination myths, and, through them, alludes to the myth of the New World as the earthly paradise. The endings of the two versions are of equivocal significance insofar as, in each, Deckard and Rachel are still symbolic of the concept of a first man and woman, or rather, of a man and woman who will represent the first of their kind at their destined terminus. The inclusion in the Directors Cut of a scene picturing a wild and unbridled unicorn (and its echo in Gaff's origami figure) brings a further coherence to this, less conspicuous, aspect of the films Edenic motif. Ridley Scott has stated that the scene was filmed prior to Legend , his next film after Blade Runner,29 and it is useful, as Philip Strick has done, to take note of its unicorn theme. Legend's opening titles, Strick says, explain that light is harboured in the soul of unicorns... They can only be found in the purest of mortals.30 In an interview with Paul Sammon, Scott has claimed that what he finds interesting in Blade Runners unicorn scene is that while so much has been made by critics of the unicorn, they've actually missed the wider issue. It is not the unicorn itself which is important. It's the landscape around it - the green landscape - they should be noticing.31 Gaff's tinfoil unicorn origami, Scott elsewhere explains, visually links up with [Deckard's] previous vision of seeing a unicorn. Which tells us that [Gaff] A) has been to Deckard's apartment, and B) is giving Deckard a full blast of his own paranoia. Gaff's message there is, Listen, pal, I know your innermost thoughts. Therefore you're a replicant. How else would I know this? 32 What Scott seems to be saying is that unicorns are a type of electric sheep, and that the dream of unicorns is an android program. Both unicorns, Deckard's and Gaff's, are constructions, of either sub-conscious daydreams or tin-foil paranoia, yet if it is the landscape that should be heeded, then nature, not pre-determined genes, nor history, becomes the determining factor for the context of the unicorn. In other words, Deckard's and, to a lesser degree, Gaff's unicorns take on the function of the nature construct and its multiple meanings. Since the unicorn's mythological framework is built upon the symbolism of folklore and Christianity, its correspondence to

AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES

27

nature in Blade Runner implies that the concept of nature may be assigned a similar metaphorical implication. Given the motif of the inception of a new existence by two unprecedented living beings, the metaphor of nature (via the unicorn) clearly conveys a strong allusion to Adam and Eve in the garden of Eden, but also to the emergence of new frontiers, such as the discovery of America, which led Christopher Columbus to believe he had found the earthly paradise. While Columbus was convinced that America was the point of the earthly paradise, whither no one can go but by God's permission,33 he was also, according to Joseph E. Duncan, one of the last to hold the belief that paradise was an attainable geographic destination.34 Nevertheless, the idea of America and its inhabitants held sway in the Old World as proof of purity, of a first state. As Duncan says of the eighteenth century, to many, the American Indians seemed like figures from a prelapsarian age.35 Mention must at this point be made of Scott's 1992 release 1492: Conquest of Paradise, a telling indication of his recurring concern with the experience of new frontiers. The discovery and penetration of frontiers variously conceived is arguably one of Scott's more prominent concerns (e.g. Alien, Thelma and Louise, G.I. Jane), but it is most clearly represented by Blade Runner and 1492 . That is, both films deal with the confrontation of authoritarian orthodoxies and primitive simplicity, and with the shift that occurs in the existence of the former at the expense of the latter. It is interesting that Philip Strick, another commentator to have noticed the connection, claims that if Ridley Scott's Columbusis to be really understood, the clues, not surprisingly, are to be traced among his predecessors [such as] the space-traveled replicants of Blade Runner. He goes on, speaking for them all, Columbus identifies an unexplored Eden, the chance of a new beginning.36 Although I think that Strick is mistaken in his analogy of Scott's Columbus with Blade Runner's replicants, I concur that there is a startling similarity in the films' (meta-)physical geographies as means of transcendence and renewal. The parallel might thus be more accurately made between Columbus and Deckard, because the focus of new beginnings is on regenerating the old (recall, for instance, the electronic billboard's promise of giving humans the chance to begin again in the New World, and of enabling them to acquire their own Best Future). To become new, it is necessary to go back to a first state from whence to begin again, but it is also necessary to be confronted with a counterpoint, be it the Taino of 1492, or the replicants of Blade Runner. The confrontation with ones counterpart is a cathartic experience in American mythology; for instance, it can inspire, as Slotkin has famously elucidated it elsewhere,37 the belief in regeneration through violence.

28

AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES

Through violent combat with Roy and final acquisition of a replicant history, Deckard regenerates himself as a new man. By crossing over and merging with his counterpart, and by ultimately abandoning the violence that partly precipitated his regeneration, Deckard is reminiscent of much of the mythology surrounding the concept of the American Frontier and its archetypal hero. In Slotkins words, the hero must experience a regression to a more primitive and natural condition of life so that the false values of the metropolis can be purged and a new purified social contract enacted.38 In this sense, Deckards and Roys dueling combat in the final scenes can be read both as references to the Eurocentrically regenerative clash between settlers and Indians and to much of Hollywoods imagery of the US soldiers immersion in the customs of a primitive Indochina (such as those depicted in Apocalypse Now and First Blood). By submerging Deckard in replicant existence in order to purge him, and by including the painting of Roys body with blood and his war-hungry howls, the film engages with both of these American mythologies. That is, because they are roughly positioned as civilized and savage in the films final scenes, Deckard and Roy play out the drama of each of these mythologies. Further, because both the Indian and the Vietnam soldier are visually invoked,39 the Vietnam myth and the myth of the American frontier are collapsed into the basic principle that every American frontier presupposes the threat of Indians.40 Deckard, as well as Scotts Columbus, can thus truly be said to become regenerated by experiencing a regression to a more primitive and natural condition of life so that the false values of the metropolis can be purged.41 If the replicants of Blade Runner and the Taino of 1492 can be viewed on equal terms as being the transcending and regenerative counterpoints to the Europeans of the Old World, then, surely, it is possible to read the replicants as those American Indians [who] seemed like figures from a prelapsarian age.42 After all, it is the replicants who enable Deckards regenerated return to what can be described (in relation to both the 1982 and the 1992 versions of the film) as a frontier opening out onto a New World Garden. Yet because Blade Runner evokes such Edenic resonance, and because of its dynamic between radical change and the recrudescence of archetype, such a reading is inherently tenuous due to the tension that inheres in the notion of returning to Eden. With their escape, Rachel and Deckard represent that most fundamentally American project, the exploration of a New Frontier. As ever, while the possibility of an Edenic utopia is deeply revolutionary, it is also extremely conservative because it entails a reversion to a long-established archetypal

AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES

29

model. Yet key statements such as Roy's enigmatic misquotation strongly convey the implication of a radical change of perspective in experiencing precedents. For humans to experience regeneration, therefore, they must alienate themselves into replicating otherness. To reach Eden in Ridley Scott's Blade Runner it is clearly necessary to go off course. ENDNOTES

1

Geoffrey Keynes, ed., Blake, Complete Writings, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1972, p. 200, plate 11, lines 1-2. 2 William James Gibson, Warrior Dreams: Paramilitary Culture in Post-Vietnam America, Hill and Wang, USA, 1994, p. 26. 3 Ibid., p. 269. 4 Albert Auster and Leonard Quart, for instance, go on to detail the Reagan/Rambo connection thus: Reagan first referred to Rambo in an angry polemic against a group of Arab terrorists who had hijacked a U.S. passenger plane in the Middle East (Boy, I saw Rambo last night; now I know what to do next time). Later, in his drive to get Congress to enact tax-reform legislation, he said, In the spirit of Rambo, let me tell you were going to win this time, Albert Auster and Leonard Quart, How the War was Remembered: Hollywood and Vietnam, Praeger, New York, 1988, p. 107] 5 Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan, Columbia University Press, New York, 1986, p. 185. 6 The question of intentionality arises here. Screenwriter David Peoples recalls, I'd done a scene where Batty discovers that the Tyrell he kills isn't the real one (...) somewhere in that scene I'd slipped in a reference to a poem by Shelley called Ozymandias. Now, Ridley is a culturally alert guy. He said, That's good. There ought to be reference to Blake, too. Let's give that to Batty. But I'm not a Blake fan -- in fact, I'd never read him before. So I dutifully went out and purchased a book of Blake, came across that America poem, rewrote it a bit, and gave the lines to Roy as a piece of dialogue. Which seemed to work; Batty was certainly the type of person who could surprise you, Paul M. Sammon, Future Noir: The Making of Blade Runner, Orion Media, London, 1996, p. 134. Scott's reply that there ought to be a reference to Blake may not be sufficient grounds to conclude that the whole film hinges on its inclusion, yet Scott's cultural alertness suggests that he may well have been aware of the resonance of his reference. 7 Originally San Francisco in Dick's novel, the city named after Saint Francis of Assisi, protector of animals. 8 Blake, America, plate 12, ll. 4-6. 9 Frosch calls Urizen Reason self-absorbed, whose critical authority operates similarly as the dissector of our moral experience, as it accuses our senses and feelings of sin -- that is, departure from its own code -- as well as inadequacy and error. Thomas R. Frosch The Awakening of Albion: The Renovation of the Body in the Poetry of William Blake, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 1974, p. 35. 10 Blake, America, plate 16, ll. 4, 1, 3. 11 Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The German Ideology, C.J. Arthur, ed., International Publishers, New York, 1970. 12 Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan, p. 72. 13 Ibid.,p. 73. 14 Roland Barthes, Mythologies, Paladin, London, 1980, pp. 141-2. 15 Notwithstanding the nature ending of Blade Runner's original release version.

30

AUSTRALASIAN JOURNAL OF AMERICAN STUDIES

16

Michael J. Shapiro,Manning the Frontiers: The Politics of (Human) Nature in Blade Runner, in: Jane Bennett and William Chaloupka eds., In the Nature of Things: Language, Politics, and the Environment, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 1993, p. 81. 17 Indeed, Shapiro says as much when he claims that, of all the characters, Roy is the most mindful of the boundary issues involved in a world shared between humans and replicants Ibid. 18 John A. Phillips, Eve: The History of an Idea, Harper & Row, San Francisco, 1984. 19 See, for instance, Philip Stricks Blade Runner: Telling the Difference, Sight and Sound, vol. 2, issue 8, December 1992, pp. 8-9. 20 It was, of course, John F. Kennedy who most famously affirmed the idealistic correlation of Americas frontier past and its future. The phrase New Frontier was first pronounced in his 1960 acceptance speech as Democratic Party presidential candidate: I stand tonight facing west on what was once the last frontier. From the lands that stretch 3000 miles behind me, the pioneers of old gave up their safety, their comfort and sometimes their lives to build a new world here in the West...[But] the problems are not all solved and the battles are not all won, and we stand today on the edge of new frontier the frontier of the 1960s, a frontier of unknown opportunities and paths, a frontier of unfulfilled hopes and threatsFor the harsh facts of the matter are that we stand on this frontier at a turning point in history[quoted in Richard Slotkin, Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth-Century America, Atheneum, New York, 1992, p. 2] 21 Ibid., p. 6. 22 Ibid., p. 649. 23 Nostalgia films, according to Jameson, are films about the past, as well as films that are ostensibly films from the past [in John Belton, ed., Movies and Mass Culture, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, 1996, p. 193]. 24 Ibid. 25 Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, p. 141. 26 R.W.B. Lewis, The American Adam: Innocence, Tragedy and Tradition in the Nineteenth Century, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1955, p. 5. 27 Ibid. 28 Ibid. 29 See Sammon's interview with Scott in Appendix A of Future Noir, pp. 375-93. 30 Strick, "Blade Runner: Telling the Difference", p. 8. 31 Sammon, Future Noir, p. 377. 32 Ibid., p. 391. 33 Quoted in Joseph E. Duncan, Milton's Earthly Paradise: A Historical Study of Eden, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 1972, pp. 188-9. Delumeau points out that even as late as the eighteenth century, a certain Pedro de Rates Hanequim (...) claimed that the earthly paradise still existed (...) it was in America, therefore, that God created Adam. Jean Delumeau, History of Paradise: The Garden of Eden in Myth and Tradition , translated. Matthew O'Connell, The Continuum Publishing Company, New York, 1995, p. 55. 34 Ibid., p. 188. 35 Ibid., p. 270. 36 Review in Sight and Sound, November 1992, vol. 2, issue 7, p. 42. 37 Richard Slotkin, Regeneration through Violence: The Mythology of the American Frontier, 1600-1860, Wesleyan University Press, USA, 1973. 38 Ibid., p. 14. 39 Roy could here be seen as either the regressed US soldier (a kind of Colonel Kurtz, Captain Willard, or Rambo), or as the vilified Vietcong of films such as The Deer Hunter. 40 Slotkin, Gunfighter Nation, pp. 646-7. 41 Ibid., p. 14. 42 Duncan, Miltons Earthly Paradise, p. 270.

Você também pode gostar

- UntitledDocumento86 páginasUntitledapi-95713912100% (6)

- Complexity and CollapseDocumento8 páginasComplexity and CollapsecorradopasseraAinda não há avaliações

- TheBadWarTheTruthNeverTaughtAboutWorldWarIiversion2MikeKing PDFDocumento266 páginasTheBadWarTheTruthNeverTaughtAboutWorldWarIiversion2MikeKing PDFchema100% (1)

- Blade Runner InsightDocumento20 páginasBlade Runner InsightLouAinda não há avaliações

- Jean Baudrillard ExplainedDocumento4 páginasJean Baudrillard ExplainedRenata Reich100% (1)

- Blackjack Sets Out Illuminati PlanDocumento40 páginasBlackjack Sets Out Illuminati PlanJeremy JamesAinda não há avaliações

- The Sea of MercyDocumento124 páginasThe Sea of MercyMohammed Abdul Hafeez, B.Com., Hyderabad, India100% (1)

- Capitalist Realism: Imagining the End of CapitalismDocumento17 páginasCapitalist Realism: Imagining the End of CapitalismUsama AlshaibiAinda não há avaliações

- Decolonising James Cameron's PandoraDocumento19 páginasDecolonising James Cameron's Pandorageevarghese52Ainda não há avaliações

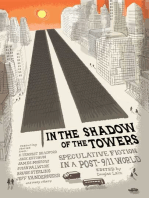

- In the Shadow of the Towers: Speculative Fiction in a Post-9/11 WorldNo EverandIn the Shadow of the Towers: Speculative Fiction in a Post-9/11 WorldAinda não há avaliações

- Dystopian Goodness and Fatherhood in Cormac McCarthy's The RoadDocumento18 páginasDystopian Goodness and Fatherhood in Cormac McCarthy's The RoadSimon DevramAinda não há avaliações

- Advanced Aerospace PropulsionDocumento57 páginasAdvanced Aerospace Propulsionsid676Ainda não há avaliações

- Andrew Wakefield (2009) Response To Dr. Ari Brown and The Immunization Action CoalitionDocumento18 páginasAndrew Wakefield (2009) Response To Dr. Ari Brown and The Immunization Action CoalitionEMFsafety100% (2)

- Chapter 01 Solutions - FMTDocumento7 páginasChapter 01 Solutions - FMTOscar Neira CuadraAinda não há avaliações

- Abundant Living 1Documento44 páginasAbundant Living 1Paul BuicaAinda não há avaliações

- RE-HMRM2121 Remedial Exam ResultsDocumento4 páginasRE-HMRM2121 Remedial Exam ResultsAlmirah Makalunas0% (1)

- Platinum Mathematics Grade 4 Lesson PlansDocumento56 páginasPlatinum Mathematics Grade 4 Lesson PlansPortia Mudalahothe79% (14)

- PM620 Unit 4 DBDocumento3 páginasPM620 Unit 4 DBmikeAinda não há avaliações

- Capitalist Realism - Is There No Alternat - Mark FisherDocumento86 páginasCapitalist Realism - Is There No Alternat - Mark FisherIon PopescuAinda não há avaliações

- Of Ants and Men - Them! and The Ambiguous Relations Between (Monstrous) Immigration and (Apocalyptic) EntomologyDocumento8 páginasOf Ants and Men - Them! and The Ambiguous Relations Between (Monstrous) Immigration and (Apocalyptic) EntomologyJuan Sebastián Mora BaqueroAinda não há avaliações

- Post-Apocalypse: Science Fiction (HI308) - Dave Reason Can Evrenol List 3 - Essay Question No.54Documento7 páginasPost-Apocalypse: Science Fiction (HI308) - Dave Reason Can Evrenol List 3 - Essay Question No.54Mehzabeen AshrafAinda não há avaliações

- HSC Advanced English Mod A EssayDocumento3 páginasHSC Advanced English Mod A EssaySW8573Ainda não há avaliações

- Even Zohar Polysystems Revisited 2005Documento11 páginasEven Zohar Polysystems Revisited 2005Carla Murad100% (2)

- The Role of The Serbian Orthodox Church in The Protection of Minorities and 'Minor' Religious Communities in The FR YugoslaviaDocumento8 páginasThe Role of The Serbian Orthodox Church in The Protection of Minorities and 'Minor' Religious Communities in The FR YugoslaviaDomagoj VolarevicAinda não há avaliações

- Encouraging Higher Level ThinkingDocumento9 páginasEncouraging Higher Level ThinkingArwina Syazwani Binti GhazaliAinda não há avaliações

- Eshel Ben-Jacob Ball 2014 Water As The Fabric of LifeDocumento4 páginasEshel Ben-Jacob Ball 2014 Water As The Fabric of LifelupocanutoAinda não há avaliações

- Detailed Lesson Plan in English: I. ObjectivesDocumento7 páginasDetailed Lesson Plan in English: I. ObjectivesnulllllAinda não há avaliações

- Naeyc StandardsDocumento5 páginasNaeyc Standardsapi-4695179940% (1)

- Not So Long Ago and Far Away Star Wars RDocumento10 páginasNot So Long Ago and Far Away Star Wars RCinderella RomaniaAinda não há avaliações

- As ST SpeechDocumento4 páginasAs ST Speechchristabelle_lamotteAinda não há avaliações

- Krause-Christopher NolanDocumento5 páginasKrause-Christopher NolanMiguel Ángel Cabrera AcostaAinda não há avaliações

- The State, Spectacle and September 11Documento17 páginasThe State, Spectacle and September 11Tanya SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Mann DISSERTATION-FINALDocumento347 páginasMann DISSERTATION-FINALkalayciaAinda não há avaliações

- Affective Picarelli LITERATURA 2008Documento13 páginasAffective Picarelli LITERATURA 2008Pedro OuroAinda não há avaliações

- Welcome To The Desert of The RealDocumento5 páginasWelcome To The Desert of The RealZuresh PathAinda não há avaliações

- Blade Runner A Diagnostic CritiqueDocumento22 páginasBlade Runner A Diagnostic CritiqueAquiles SalcedoAinda não há avaliações

- Imagining the End of Capitalism Through Disaster FilmsDocumento12 páginasImagining the End of Capitalism Through Disaster FilmsDean InksterAinda não há avaliações

- From Prophecy to Prediction: A Survey of IdeasDocumento3 páginasFrom Prophecy to Prediction: A Survey of Ideasmonja777Ainda não há avaliações

- The Evolution of Dystopian Literature and Why 1984 Still PertainsDocumento29 páginasThe Evolution of Dystopian Literature and Why 1984 Still PertainsNoor Al hudaAinda não há avaliações

- Sequence 3 LlceDocumento3 páginasSequence 3 Llcejabbiekadi1Ainda não há avaliações

- Article New York ReviseDocumento21 páginasArticle New York ReviseowazisAinda não há avaliações

- Cyborg Ontology in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas On The Road To Consciousness: The Red Shark, The White Whale & Reading The Textual BodyDocumento12 páginasCyborg Ontology in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas On The Road To Consciousness: The Red Shark, The White Whale & Reading The Textual BodyIbanezAinda não há avaliações

- A Hero Will Rise - Myth of The Fascist Man in Fight Club and GladiatorDocumento47 páginasA Hero Will Rise - Myth of The Fascist Man in Fight Club and GladiatorLouis Saint-Just100% (1)

- Campbell Libertarian 2Documento12 páginasCampbell Libertarian 2CurvionAinda não há avaliações

- Science Fiction in The Reagan EraDocumento9 páginasScience Fiction in The Reagan Eraapi-258949253Ainda não há avaliações

- CosmopolisDocumento6 páginasCosmopolisKASHISH AGARWALAinda não há avaliações

- Last and First Capitalisms The Future HiDocumento7 páginasLast and First Capitalisms The Future HiDimitris RoutosAinda não há avaliações

- Sic HerDocumento31 páginasSic HerNoor Al hudaAinda não há avaliações

- Flying Man Falling ManDocumento17 páginasFlying Man Falling ManRobin VeenmanAinda não há avaliações

- On Dystopia: Terminator Sequence (1984-2009) To The Matrix Trilogy (1999-2003)Documento16 páginasOn Dystopia: Terminator Sequence (1984-2009) To The Matrix Trilogy (1999-2003)api-215491864Ainda não há avaliações

- Spartacus Essay Mubarrat ChoudhuryDocumento4 páginasSpartacus Essay Mubarrat ChoudhuryMubarrat Mahdin ChoudhuryAinda não há avaliações

- Content ServerDocumento21 páginasContent ServerAgosAinda não há avaliações

- Territory, Terror and Torture: Dream-Reading The Apocalypse: End of The WorldDocumento21 páginasTerritory, Terror and Torture: Dream-Reading The Apocalypse: End of The WorldDiana M.Ainda não há avaliações

- Rise of Zombies in A Post-September 11th CultureDocumento12 páginasRise of Zombies in A Post-September 11th CultureLee GullicksonAinda não há avaliações

- Blindfolded and Backwards Promethean and Bemushroomed Heroism in One Flew OverDocumento10 páginasBlindfolded and Backwards Promethean and Bemushroomed Heroism in One Flew Over1 LobotomizerXAinda não há avaliações

- A - Matrix and SFDocumento19 páginasA - Matrix and SFDionis BodiuAinda não há avaliações

- Barbie CanDocumento3 páginasBarbie CanGeorgeAinda não há avaliações

- Nineteen Eighty-Four in 1984: How does the novel help our understanding of the yearDocumento5 páginasNineteen Eighty-Four in 1984: How does the novel help our understanding of the yearRobin DharmaratnamAinda não há avaliações

- The Great National DisasterDocumento30 páginasThe Great National Disasterlucas parenteAinda não há avaliações

- Reading Films, NorrisDocumento22 páginasReading Films, NorrisMaryam MuhammadAinda não há avaliações

- Challenging Conservative Thinking in Post-War TextsDocumento3 páginasChallenging Conservative Thinking in Post-War TextsmaanyaAinda não há avaliações

- Metamorphosis of the Anti-Hero in Simulated AmericaDocumento12 páginasMetamorphosis of the Anti-Hero in Simulated AmericaLalita HarshAinda não há avaliações

- New Yorker - Dystopian Article & Lit Circle Q'sDocumento7 páginasNew Yorker - Dystopian Article & Lit Circle Q'svictortengckAinda não há avaliações

- Wells Sleep DealerDocumento23 páginasWells Sleep DealerJosé R. Paredes DávilaAinda não há avaliações

- Science and Technology Confront RealityDocumento2 páginasScience and Technology Confront RealitygiovpAinda não há avaliações

- FinalArticle TheophanieN 19111091Documento4 páginasFinalArticle TheophanieN 19111091Theofanny NainggolanAinda não há avaliações

- Humans vs HumanityDocumento7 páginasHumans vs HumanityDakota SmithAinda não há avaliações

- Zizek, BLADE RUNNER 2049: A VIEW OF POST-HUMAN CAPITALISMDocumento10 páginasZizek, BLADE RUNNER 2049: A VIEW OF POST-HUMAN CAPITALISMRobin PagolaAinda não há avaliações

- Necsus2014 1 Mein PDFDocumento19 páginasNecsus2014 1 Mein PDFHospodar VibescuAinda não há avaliações

- Posthumanism as Speculative Aesthetics in Ballard and BrassierDocumento14 páginasPosthumanism as Speculative Aesthetics in Ballard and BrassiervoyameaAinda não há avaliações

- Baker Family of Secrets 2009 SynopsisDocumento5 páginasBaker Family of Secrets 2009 SynopsisBryan GraczykAinda não há avaliações

- Contaminants in Human Milk - Risks vs. Benefits of BreastfeedingDocumento9 páginasContaminants in Human Milk - Risks vs. Benefits of BreastfeedingBryan GraczykAinda não há avaliações

- Latent Viruses and Mutated Oncogenes - No Evidence For PathogenicityDocumento42 páginasLatent Viruses and Mutated Oncogenes - No Evidence For PathogenicityBryan GraczykAinda não há avaliações

- The Effect of A Cat's Purr On HealthDocumento7 páginasThe Effect of A Cat's Purr On HealthBryan GraczykAinda não há avaliações

- Alimentatia Copilului - OMSDocumento112 páginasAlimentatia Copilului - OMSshugyosha77Ainda não há avaliações

- DID Thru Jung's LensDocumento97 páginasDID Thru Jung's LensBryan GraczykAinda não há avaliações

- A Visit to Defkalion Green Technologies Laboratory Provides Insights Into New Energy ProcessDocumento4 páginasA Visit to Defkalion Green Technologies Laboratory Provides Insights Into New Energy ProcessBryan GraczykAinda não há avaliações

- The Seat of The Soul The Origins of The Autism EpidemicDocumento33 páginasThe Seat of The Soul The Origins of The Autism EpidemicBryan GraczykAinda não há avaliações

- A Systematic Review of How Homeopathy Is RepresentedDocumento4 páginasA Systematic Review of How Homeopathy Is RepresentedBryan GraczykAinda não há avaliações

- Congress TestimonyDocumento6 páginasCongress TestimonyBryan GraczykAinda não há avaliações

- A Gravity-Driven Electric Current in The Earth's IonosphereDocumento5 páginasA Gravity-Driven Electric Current in The Earth's IonosphereBryan GraczykAinda não há avaliações

- ACUPUNCTUREDocumento87 páginasACUPUNCTUREdremad1974Ainda não há avaliações

- 21st Sci TechDocumento60 páginas21st Sci TechBryan Graczyk100% (1)

- A Critical Review of Permaculture in The United StatesDocumento20 páginasA Critical Review of Permaculture in The United StatesBryan Graczyk0% (1)

- The Myth of Matriarchy: Why Men Rule in Primitive Society: Bachofen and Mother Right: Myth and HistoryDocumento18 páginasThe Myth of Matriarchy: Why Men Rule in Primitive Society: Bachofen and Mother Right: Myth and HistoryAdriana ScarpinAinda não há avaliações

- 2011 City Park FactsDocumento36 páginas2011 City Park FactsBryan GraczykAinda não há avaliações

- The Double Helix Theory of The Magnetic FieldDocumento17 páginasThe Double Helix Theory of The Magnetic FielddgabrijelAinda não há avaliações

- Quantum Holography and Neurocomputer ArchitecturesDocumento75 páginasQuantum Holography and Neurocomputer ArchitecturesBryan GraczykAinda não há avaliações

- Remembering The Past, Anticipating A Future p4Documento11 páginasRemembering The Past, Anticipating A Future p4Bryan GraczykAinda não há avaliações

- Richard L. Amoroso and J-P. Vigier - Can One Unify Gravity and Electromagnetic FieldsDocumento18 páginasRichard L. Amoroso and J-P. Vigier - Can One Unify Gravity and Electromagnetic FieldsKlim00Ainda não há avaliações

- The Fallacy of Generalizing From Egg Salad in False-Belief ResearchDocumento7 páginasThe Fallacy of Generalizing From Egg Salad in False-Belief ResearchBryan GraczykAinda não há avaliações

- What's in A Name For Memory ErrorsDocumento33 páginasWhat's in A Name For Memory ErrorsBryan GraczykAinda não há avaliações

- Cold Fusion Nuclear Reactions of H & NiDocumento8 páginasCold Fusion Nuclear Reactions of H & NiBryan GraczykAinda não há avaliações

- Engineering The Coupling Between Molecular Spin Qubits by Coordination ChemistryDocumento7 páginasEngineering The Coupling Between Molecular Spin Qubits by Coordination ChemistryBryan GraczykAinda não há avaliações

- Carmen Boulter ThesisDocumento0 páginaCarmen Boulter ThesisBryan GraczykAinda não há avaliações

- Competency 1Documento40 páginasCompetency 1api-370890757Ainda não há avaliações

- "Motivation": AssignmentDocumento22 páginas"Motivation": AssignmentNadim Rahman KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Ed 82-Facilitating Learning Midterm ExaminationDocumento3 páginasEd 82-Facilitating Learning Midterm ExaminationMarc Augustine Bello SunicoAinda não há avaliações

- PHYS 81 - QuestionsDocumento2 páginasPHYS 81 - QuestionsAlbertAinda não há avaliações

- The Weeds That Curtail The Bhakti CreeperDocumento3 páginasThe Weeds That Curtail The Bhakti Creeperscsmathphilippines - sri nama hatta centerAinda não há avaliações

- Rationalism ScriptDocumento2 páginasRationalism Scriptbobbyforteza92Ainda não há avaliações

- (Wafa Khan) (B19822120) HOI-1Documento18 páginas(Wafa Khan) (B19822120) HOI-1Warda KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Derrida of Spirit ParagraphDocumento1 páginaDerrida of Spirit Paragraphblackpetal1Ainda não há avaliações

- Shree Satya Narayan Kath ADocumento3 páginasShree Satya Narayan Kath Asomnathsingh_hydAinda não há avaliações

- Section 1.1 Matrix Multiplication, Flop Counts and Block (Partitioned) MatricesDocumento4 páginasSection 1.1 Matrix Multiplication, Flop Counts and Block (Partitioned) MatricesMococo CatAinda não há avaliações

- Nature of Technology: "Purposeful Intervention by Design"Documento2 páginasNature of Technology: "Purposeful Intervention by Design"Angeline ParfilesAinda não há avaliações

- Research Verb TenseDocumento2 páginasResearch Verb TensePretty KungkingAinda não há avaliações

- This Is Shaikh AlbaaniDocumento86 páginasThis Is Shaikh Albaaniمحمد تانزيم ابراهيمAinda não há avaliações

- Final Resume PDFDocumento2 páginasFinal Resume PDFapi-455336543Ainda não há avaliações

- Đề Luyện Số 9Documento10 páginasĐề Luyện Số 9Loan Vũ100% (1)

- Bishop Mallari Coat of Arms Prayer BrigadeDocumento5 páginasBishop Mallari Coat of Arms Prayer BrigadeHerschell Vergel De DiosAinda não há avaliações

- Journal Review - Philosophical Theories of Truth and NursingDocumento3 páginasJournal Review - Philosophical Theories of Truth and Nursingjulie annAinda não há avaliações

- Writing Gone Wilde - Ed CohenDocumento14 páginasWriting Gone Wilde - Ed CohenElisa Karbin100% (1)

- What Is Ethics?: and Why Is It Important?Documento17 páginasWhat Is Ethics?: and Why Is It Important?kaspar4Ainda não há avaliações