Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Resilience in Children of Alcoholics Linked to Lower Internalizing Symptoms

Enviado por

efunctionDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Resilience in Children of Alcoholics Linked to Lower Internalizing Symptoms

Enviado por

efunctionDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Applied Developmental Psychology 25 (2004) 577 595

Resilience in a community sample of children of alcoholics: Its prevalence and relation to internalizing symptomatology and positive affect

Adam C. Carlea,b,*, Laurie Chassinb

a

Center for Survey Methods Research, Statistical Research Division, U.S. Bureau of the Census, United States b Adult and Family Development Project, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University, United States

Abstract Data from an ongoing longitudinal study examined resilience (competent performance under adverse conditions) in a community sample of children of alcoholics (COAs n = 216) and matched controls (n = 201). The study examined the prevalence of competence and whether the relation of competence to internalizing and positive affect differed for COAs and controls. COAs were less likely to be highly competent in the conduct/ruleabiding and academic domains and more likely to be low competent. Controlling for previous levels of internalizing, highly competent children in the conduct/rule-abiding and overall competence domains endorsed significantly lower levels of internalizing symptomatology. For the social, conduct/rule-abiding, and overall competence domains, competence was associated with increased positive affect. The relation between competence and internalizing, and competence and positive affect did not differ for COAs and controls. Results suggested that behavioral resilience is not associated with psychological costs but is associated with decreased internalizing and increased positive affect. Published by Elsevier Inc.

Keywords: Children of alcoholics; Resilience (psychological); Competence; At risk populations; Adjustment; Well-being

* Corresponding author. Center for Survey Methods Research, Statistical Research Division, U.S. Bureau of the Census, Washington, DC, 20233-9100, United States. Tel.: +1 301 763 1836; fax: +1 301 457 4931. E-mail address: adam.c.carle@census.gov (A.C. Carle). 0193-3973/$ - see front matter. Published by Elsevier Inc. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2004.08.005

578

A.C. Carle, L. Chassin / Applied Developmental Psychology 25 (2004) 577595

1. Introduction Developmental psychopathologists have identified a number of risks associated with the development and onset of psychological disorder (Cicchetti & Garmezy, 1993). However, not all children exposed to risk develop pathology (Cowen & Work, 1988; Garmezy, 1985; Masten, 1990; Rutter, 1979; Werner, 1993; Werner & Smith, 1982). These children are considered to be resilient and are those individuals who, despite high-risk status, manage to defeat the odds (Garmezy & Neuchterlein, 1972). Knowledge of why some children manage to escape the effects of risk factors, while others do not, can lead to effective prevention and intervention strategies designed to promote mental health (Cowen, 1991; Cowen & Work, 1988). For example, encouraging competent behavior in children at risk may lead to increased emotional adjustment and decreased internalizing symptomatology, providing clinicians a route to combat the effects of childrens negative life experiences. The current study examined the relation of resilience to internalizing symptomatology and positive affect in children of alcoholic parents (COAs), a relatively understudied risk group in the resilience field. Resilience has been defined a number of ways, but is often characterized as successful adaptation, despite risk (Masten, Best, & Garmezy, 1990), with successful adaptation defined as competent performance (Masten & Coatsworth, 1995). Masten et al. (1999) have described competence as ba pattern of effective performance in the environment, evaluated from the perspective of development in ecological and cultural contextQ (Masten & Coatsworth, 1995, p. 724). Within this perspective, successful resolution of culturally salient developmental tasks marks competence. Masten et al. (1995) identified three developmental tasks in late childhood/early adolescence corresponding to three domains of competence: academic achievement, conduct/rule-abiding behavior, and social relationships. Successful performance in these areas reflects competence. The concept of resilience also requires exposure to a risk factor. For children exposed to the risk factor, there is an increased probability of developing psychopathology (Kraemer et al., 1997). Resilience has been studied across a number of groups: children exposed to adverse socioeconomic disadvantage (Garmezy, 1981, 1985; Rutter, 1979; Werner & Smith, 1982), children of schizophrenic mothers (Garmezy, 1984), maltreated children (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1997), children exposed to urban poverty and violence (Luthar, 1999; Richters & Martinez, 1993), children with chronic illness (Wells & Schwebel, 1987), children of divorce (Hetherington & Stanley-Hagan, 1999), and children exposed to catastrophic life events (Wright, Masten, Northwood, & Hubbard, 1997). These studies have sought to identify whether positive outcomes exist for these children, as well as whether specific factors lead to resilient outcomes (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000). Although the focus of these studies has differed, they have consistently identified resilient children. Unfortunately, resilience has been relatively understudied in a number of important risk groups, among them, children of alcoholic parents. As compared to their peers in nonalcoholic families, children of alcoholic parents are reported to be at increased risk for a number of negative outcomes, including internalizing and externalizing symptomatology and substance abuse (Chassin, Rogosch, & Barrera, 1991; McGue, Sharma, & Benson, 1996; Moos & Billings, 1982; Roosa, Sandler, Beals, & Short, 1988; Tubman, 1993). Furthermore, parental alcoholism is a relatively prevalent risk factor, with estimates suggesting that one in four children in the United States is exposed to alcohol dependence or abuse in the family (Grant, 2000). The relatively high prevalence of parental alcoholism, combined with the associated negative impact, places a large number of children at risk (West & Prinz, 1987). Unfortunately, little research has examined resilience in children of alcoholic parents. A few studies have examined dprotectiveT factors leading to the

A.C. Carle, L. Chassin / Applied Developmental Psychology 25 (2004) 577595

579

absence or low levels of negative outcomes among children of alcoholic parents. Farrell, Barnes, and Banerjee (1995) noted that family cohesion was negatively related to psychological distress, deviant behavior, and heavy drinking in adolescents over a period of 1 year. Hussong and Chassin (1997) found that family organization, higher perceived control, and high levels of cognitive coping were associated with a decreased likelihood of substance use initiation, regardless of parental alcoholism status. Although these studies represent important findings examining protective factors in children of alcoholic parents, they are few in number, fail to address the possibility of positive outcomes in children of alcoholic parents, and do not address issues of mental health in relation to competent behavior. One debate in the study of competence is whether effective performance, defined by behavioral criteria (e.g., academic achievement, conduct/rule-abiding behavior), also predicts positive psychological adjustment (Luthar & Zigler, 1991). In a cross-sectional study of inner city children, Luthar (1991) found that resilient children displayed more depression and anxiety than did competent children at similar levels of behavioral competence but not experiencing risk. Luthar, Doernberger, and Zigler (1993) replicated this finding in a larger sample and included a prospective design. The authors suggested that, for children from stressful backgrounds, the costs of maintaining competent behavior in the face of stress may be too high and may result in internalizing symptoms. However, these findings have not been consistent within the field. For example, Masten et al. (1999) found that resilient children showed significantly less internalizing symptomatology and higher levels of positive affect than nonresilient children. They proposed a dpleasure in masteryT explanation, such that successful resolution of developmental tasks (i.e., competence) is pleasurable and encourages positive emotional outcomes in resilient children. The question of whether behavioral competence among children at risk promotes positive emotional adjustment has not been adequately examined among children of alcoholic parents. It is uncertain whether efforts to increase competent behavior in children of alcoholic parents would lead to similar positive changes in mental health. Clinical observations have hypothesized that there may be a relationship between resilience and internalizing symptoms for adult children of alcoholic parents. Sher (1991), in a review of the clinical literature, discussed the bheroQ child who is depressed and anxious despite outward evaluations of success, similar to the model proposed by Luthar (1991, 1995; Luthar et al., 1993). Empirical tests of this notion in adolescent children of alcoholic parents are lacking. Two studies tested the relation of positive outcomes to internalizing symptoms in adult children of alcoholic parents (Hinz, 1990; Tweed & Ryff, 1989) and found that positive outcomes in adult children of alcoholic parents were related to increased internalizing symptoms. However, results were based on retrospective report, did not include a comparison group of nonresilient adult children of alcoholic parents, and were cross-sectional in nature. In summary, resilience, as measured by manifest behavioral competence despite risk, has been associated with both higher levels of internalizing symptoms (Luthar, 1991; Luthar et al., 1993) and lower levels of internalizing symptoms (Masten et al., 1999), but the results are constrained by methodological considerations and are unexamined for adolescent children of alcoholic parents. Thus, it remains unclear whether prevention and intervention efforts to promote competent behavior among children at risk might be associated with negative mental health sequelae. The current study examined the relation of resilience to internalizing symptomatology and positive affect among children of alcoholic parents and makes several contributions both to the resilience literature and the literature on children of alcoholic parents. First, resilience has not been adequately studied in the children of alcoholic parents literature and little information exists regarding this group. Second, the study provides a replication and

580

A.C. Carle, L. Chassin / Applied Developmental Psychology 25 (2004) 577595

extension of the works of Luthar (1991), Luthar et al. (1993) and Masten et al. (1999). Third, the study provides several methodological advantages, including a relatively large sample, a prospective design, and three levels of competence (low, average, and high) to capture more heterogeneity in competent behavior. Specifically, the current study addressed the following questions: What is the prevalence of competence across social, conduct/rule-abiding, academic, and overall competence domains, and does this prevalence differ for children of alcoholic parents as compared with children of nonalcoholic parents? Does competence relate to internalizing symptomatology and positive affect, and does the relation differ for children of alcoholic parents and children of nonalcoholic parents?

2. Method 2.1. Participants Participants were a subset of a larger, longitudinal study of adolescents and their families (N = 454 families; 246 children of alcoholic parents and 208 children of nonalcoholic parents; Chassin et al., 1991; Chassin, Barrera, Bech, & Kossak-Fuller, 1992), in which participants were interviewed three times at annual intervals. To be included in the current analyses, a child and at least one parent in each family were required to have complete data from the second and third waves of measurement (positive affect and competence data were available only at these waves of measurement). In total, 216 alcoholic and 201 nonalcoholic families met these criteria (N = 417; 92% of the total sample). Selection biases were assessed by comparing adolescents included to adolescents not included in terms of their Time 1 measurements. No significant differences were found, except that alcoholic families were less likely to be included than were nonalcoholic families [v 2(1, N = 454) = 11.74; p b .05]. Participants in the subsample ranged in age from 11 to 17 years (M = 14.2) at Time 2 and were predominantly nonHispanic Caucasian (71% vs. 24% Hispanic for children of alcoholic parents and 70% vs. 29% Hispanic for children of nonalcoholic parents). Alcoholic and control families did not differ on ethnicity, age, gender, or socioeconomic status. 2.1.1. Recruitment methods Recruitment procedures are presented in detail elsewhere (Chassin et al., 1992). Children of alcoholic parent families were recruited using court records, health maintenance organization (HMO) wellness questionnaires, and community telephone surveys. Families chosen were either of non-Hispanic Caucasian or Hispanic ethnicity and lived in the state of Arizona. Direct verification of parental alcoholism was ascertained in a face-to-face interview using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Version III (DIS; Robins, Helzer, Croughan, & Ratcliff, 1981) to obtain a DSM-III diagnosis of lifetime alcohol abuse or dependence. Interviews were conducted with the alcoholic parent, unless they refused to participate, in which case, he or she was diagnosed alcoholic by spousal report using the Family HistoryResearch Diagnostic Criteria (FH-RDC, Endicott, Andreason, & Spitzer, 1975). Matched control families were recruited by telephone interviews. Reverse directories were used to find families living in the same demographic area as the COA families and were screened to match the COA participant in ethnicity, family composition, target childs age, and SES (using the property value code from the reverse directory). Direct interview data were used to confirm that neither the biological nor custodial parent met DSM-III or FH-RDC lifetime diagnosis of alcohol abuse or dependence.

A.C. Carle, L. Chassin / Applied Developmental Psychology 25 (2004) 577595

581

2.1.2. Potential recruitment biases Recruitment biases because of selective contact with participants and participant refusal are discussed elsewhere (Chassin et al., 1992). Although initial contact rates were low, participation rates were high (72.8% of eligible COA families and 77.3% of eligible control families). No participation biases were found with respect to alcoholism variables, and comorbidities were similar to those reported in the National Institute of Mental Health Epidemiological Catchment Area Program (ECA; Helzer & Pryzbeck, 1988). However, individuals who refused to participate were more likely to be Hispanic, and participants recruited through court records were more likely to be married at the time of their arrest (Chassin et al., 1992). 2.2. Procedures Three computer-assisted interviews were conducted at 1-year intervals. Each family member (mother, father, and adolescent) was interviewed separately to protect privacy. A Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the Department of Health and Human Services, and all participants were informed of its provisions. Interviews required 12 h to complete, and families were paid US$50 for their participation. 2.3. Measures 2.3.1. Parental alcoholism Lifetime alcoholism diagnoses were obtained from a computerized version of the DIS, Version III (Robins et al., 1981) administered by lay interviewers. Diagnoses were based on DSM-III criteria. A parent was considered alcoholic if they met criteria for either abuse or dependence diagnoses. 2.3.2. Adolescent self-report of internalizing symptomatology Adolescents reported their internalizing problems (over the past 3 months) at Times 2 and 3 based on seven Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL, Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983) items (e.g., I felt I had to be perfect ; I was too fearful or anxious ). The internalizing items were selected to represent those items that loaded highly on the internalizing factor described by Achenbach and Edelbrock (1983) for both boys and girls 1216 years old. The original response scale was altered to increase the variance of the adolescents scores and to remove the confounding of frequency and intensity in a single response scale. The modified response options ranged from 1 (almost always ) to 5 (almost never ). Alpha coefficients were 0.78, and 0.77 at Times 2 and 3, respectively. For the current analyses, scores were centered (l = 0) and recoded such that high scores reflected greater levels of internalizing symptomatology. 2.3.3. Adolescent self-report of positive affect Positive affect was assessed at the third wave of measurement using the full set of five items measuring positive affect from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). At Time 3, adolescents reported the degree to which they felt interested, strong, enthusiastic, inspired, and active within the last 3 months. Responses were based on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (very slightly or not at all ) to 5 (extremely ). In the current analyses, an internal consistency of 0.80 was found, scores were centered (l = 0), and high scores reflected greater levels of positive affect.

582

A.C. Carle, L. Chassin / Applied Developmental Psychology 25 (2004) 577595

2.3.4. Competence Competence scale construction followed the general method described by Masten et al. (1995). Based on face valid representation of a given competence domain definition, the authors independently drew items from the larger item domain of the study. Items common to both lists were included in the measure of competence for each domain. The remaining items were included based upon consensus decision. Because individual items were drawn from a variety of scales with a range of response options for each domain, item scores were transformed to a standardized metric (l = 0, r = 1), and individual scale scores were computed as the average item score for the items included in that scale. Where appropriate, exploratory factor analyses examined the construct validity of the item set for each competence domain. 2.3.5. Social competence At Times 2 and 3, adolescents reported the degree to which they endorsed 11 items related to social behaviors. Items were drawn from within the larger study. Six items were drawn from a peer involvement scale (e.g., gone over to a friends house or had a friend come over to your house ) and were reported on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost everyday ) to 4 (rarely or never ). One item (I make friends easily ) was from a temperament scale and was reported on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very unlike me ) to 5 (very like me ). Three items were from a social support scale that addressed the number of friends an adolescent had (e.g., how many female friends do you have ). Finally, one item (I didnt get along with other kids ) from the CBCL (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983) was reported on an adapted five-point scale ranging from 1 (almost always ) to 5 (almost never ). Parents also reported on the degree to which the child engaged in social behaviors on one item from a temperament scale (makes friends easily ). Where data were available from both parents, an average was computed for this item. As noted above, to create a scale score, item responses were transformed to a standardized metric (l = 0, r = 1), the scale score was computed as the average item score, and higher values reflected greater levels of social competence. Exploratory factor analyses supported the construct validity of the composite. An orthogonal rotation, allowing items to cross-load, suggested that the items represented two aspects of social behavior bengagement in social activitiesQ and the bability to make friends.Q Six items loaded primarily on the bengagement in social activitiesQ factor (range: 0.63 to 0.25) and had small loadings on the bability to make friendsQ factor (range: 0.02 to 0.21). The communalities for these items ranged from 0.63 to 0.25. Likewise, five items loaded most highly on the bability to make friendsQ factor (range: 0.46 to 0.41) and did not load highly on the bengagement in social activitiesQ factor (range: 0.06 to 0.11). For these five items, communalities ranged from 0.32 to 0.17. The alpha coefficient for the set of 11 items was 0.74 at Time 2. 2.3.6. Conduct/rule abiding competence At Times 2 and 3, adolescents reported the degree to which they endorsed 12 items selected from the CBCL (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983) describing conduct/rule-abiding related problems (e.g., I was suspended from school ). Responses were based on an adapted five-point scale ranging from 1 (very unlike me ) to 5 (very like me ). Consistent with the other competence scales, item responses were transformed to a standardized metric (l = 0, r = 1), the scale score was computed as the average item score, and higher values reflected greater levels of conduct/rule-abiding competence. Exploratory factor analyses generally supported the construct validity of the scale and suggested that the items represented two aspects of conduct/rule abiding competence: passive and aggressive conduct

A.C. Carle, L. Chassin / Applied Developmental Psychology 25 (2004) 577595

583

problems. Two of the initially selected 12 items did not load well on either factor and were eliminated from the scale. Following the elimination of these two items, communalities for the resulting two-factor, orthogonal rotation, allowing item cross loadings, ranged from 0.17 to 0.69. Six items loaded highly on the bpassiveQ factor (range: 0.69 to 0.30), while simultaneously having relatively small loadings on the baggressiveQ factor (range: 0.15 to 0.30). The remaining four items had relatively large loadings on the baggressiveQ factor (range: 0.83 to 0.41) and small loadings on the bpassiveQ factor (range: 0.07 to 0.31). The resulting 10-item scale had an alpha coefficient of 0.80 at Time 2. 2.3.7. Academic competence At Times 2 and 3, parents reported the grades a child received in school. Responses were based on a five-point scale, ranging from 1 (A = Excellent, 90% or better ) to 5 (F = Unsatisfactory, less than 60% ). At Times 2 and 3, adolescents were given the Wide Range Achievement Test-Revised (WRATR; Jastak & Wilkinson, 1984) to assess reading achievement. Acceptable levels of reliability have been reported for this test (Jastak & Wilkinson, 1984). A standardized WRAT-R score was used based on methods suggested by Jastak and Wilkinson (1984). Scores for the two measures were transformed to a standardized metric(l = 0, r = 1), and a participants academic competence score was computed as the average of the two scores. Higher values reflected greater levels of academic competence. Factor analyses were not performed for this domain given that only two scores made up the composite. 2.4. Defining competence groups For both Times 2 and 3, three competence groups (low competent, competent, and highly competent) were defined using standard deviation based cut scores for each domain.1 For the social and academic domains, children who scored one standard deviation below the estimated population average were considered low competent, children who scored between one standard deviation below and one standard deviation above the estimated sample average were considered competent, and those children who scored at least one standard deviation above the estimated population average were considered highly competent. For the conduct/rule-abiding competence domain, the distribution of scores was negatively skewed at both waves of measurement, and scores did not range greater than one standard deviation above the mean, hence, the procedure was modified. Children who fell at least one standard deviation below the mean were still classified as low competent. Those children who endorsed no conduct/ruleabiding behavior problems were considered highly competent, and the remaining children were considered competent. Consistent with Masten et al. (1999), an overall competence classification was included. Children were considered highly competent if they were classified as highly competent in at least two out of three domains. Children were classified as competent if they were performing competently in at least two of three competence domains, or if they were performing competently in one domain and were classified as

1

Because the original study oversampled for parental alcoholism, it was possible that behavior specific to children of alcoholic parents would bias sample-based estimates, disproportionately weighting the contribution of children of alcoholic parents. This was addressed by computing the weighted means and standard deviations as a function of the prevalence rate of alcoholism in the United States. Prevalence rates from two large epidemiological studies in four metropolitan cities across the United States were used to estimate the lifetime prevalence of alcohol dependence and abuse (see Karno et al., 1987; Robins et al., 1984).

584

A.C. Carle, L. Chassin / Applied Developmental Psychology 25 (2004) 577595

highly competent in another (but not highly competent in two others). All other children were classified as low competent.

3. Results 3.1. Descriptive statistics Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for Time 3 internalizing symptomatology and Time 3 positive affect across Time 2 competence groups and parental alcoholism status. On average, children classified

Table 1 Mean (and SD ) Time 3 internalizing symptomatology scores and Time 3 positive affect scores across Time 2 competence group and parental alcoholism status Time 2 competence and parental alcoholism status group M Highly competent Total sample COA Non-COA Competent group Total Sample COA Non-COA Low-competent group Total Sample COA Non-COA Time 2 competence and parental alcoholism status group M Highly competent group Total Sample COA Non-COA Competent group Total sample COA Non-COA Low-competent group Total sample COA Non-COA 0.44 0.50 0.37 0.06 0.07 0.20 0.66 0.91 0.39 0.46 0.51 0.41 0.01 0.30 0.29 0.32 0.29 0.35 Time 3 internalizing symptomatology score Social (SD ) (1.46) (1.46) (1.49) (1.50) (1.60) (1.33) (1.66) (1.60) (1.76) M 0.79 0.70 0.86 0.07 0.23 0.09 0.82 0.77 0.99 Conduct (SD ) (1.38) (1.35) (1.41) (1.43) (1.57) (1.27) (1.68) (1.60) (1.99) Academic M 0.17 0.10 0.37 0.06 0.29 0.20 0.04 0.01 0.08 (SD ) (1.41) (1.45) (1.37) (1.55) (1.63) (1.42) (1.58) (1.61) (1.56) M 1.02 0.92 1.09 0.06 0.26 0.14 0.41 0.46 0.30 Overall (SD ) (1.25) (1.22) (1.31) (1.50) (1.61) (1.34) (1.67) (1.51) (2.03)

Time 3 positive affect score Social (SD ) (1.28) (1.36) (1.22) (1.50) (1.49) (1.50) (1.45) (1.43) (1.44) M 0.38 0.52 0.28 0.01 0.08 0.11 0.61 0.72 0.25 Conduct (SD ) (1.59) (1.47) (1.67) (1.37) (1.40) (1.34) (1.70) (1.64) (1.91) Academic M 0.37 0.22 0.48 0.04 0.15 0.10 0.22 0.26 0.18 (SD ) (1.43) (1.37) (1.47) (1.49) (1.53) (1.44) (1.51) (1.51) (1.53) M 0.43 0.24 0.59 0.01 0.08 0.11 0.47 0.55 0.32 Overall (SD ) (1.46) (1.33) (1.56) (1.45) (1.50) (1.40) (1.70) (1.56) (2.01)

COA = children of alcoholics; non-COA = children of nonalcoholics.

A.C. Carle, L. Chassin / Applied Developmental Psychology 25 (2004) 577595

585

as highly competent generally endorsed the lowest levels of internalizing symptomatology and the highest levels of positive affect. Likewise, on average, children classified as low competent generally endorsed the highest levels of internalizing symptomatology and the lowest levels of positive affect. A similar pattern was evidenced within risk status (see Table 1). The possibility of a systematic relation among these variables is explored below. 3.2. Prevalence of competence Table 2 presents the competence distributions across parental alcoholism status. Because the alcoholic and control samples did not differ significantly on SES, ethnicity, age, or gender of child, these potential confounds were not examined for the current study. A review of Table 2 demonstrates that, despite apparent differences across parental alcoholism status for the highly competent and low competent domains, a substantial percentage of children of alcoholic parents were classified as competent in each of the domains. Chi-square estimates were used to examine whether the conditional distributions of competence were identical for children of alcoholic and of nonalcoholic parents. For social competence, there were no significant effects of parental alcoholism status at either wave of measurement. For conduct/rule-abiding competence, there was a significant effect of parental alcoholism at both waves of measurement [Time 2: v 2(2, N = 417) = 21.35; p b .05; Time 3: v 2(2, N = 417) = 14.38; p b .05]. Odds ratios suggested that, at Time 2, children of nonalcoholic parents were 5.31 times as likely as children of alcoholic parents to be classified as highly competent as opposed to low competent. Likewise, children of nonalcoholic parents were 3.56 times as likely as children of alcoholic parents to be classified competent as opposed to low competent. For behavioral competence, the same pattern was found at Time 3. Although no significant effects were found for academic competence at Time 2, there was a significant effect of parental alcoholism on academic competence at Time 3 [v 2(2, N = 417) = 7.11; p b .05]. At Time 3, children of nonalcoholic parents were 2.37 times as likely as children of alcoholic parents to be classified highly competent as opposed to low-competent. Likewise, children of nonalcoholic parents were 1.49 times as likely as children of alcoholic parents to be classified competent as opposed to low competent. In sum, for both

Table 2 Prevalence (% observed) of social competence, conduct/rule-abiding competence, academic competence, and overall competence at Times 2 and 3 Competence domain and parental alcoholism status groups Social COA Time 2 competence groups Highly competent 12.04 Competent 73.61 Low competent 14.35 Time 3 competence groups Highly competent 16.67 Competent 66.2 Low competent 17.13 Non-COA 12.44 73.13 14.43 11.44 73.13 15.42 COA 15.74 62.96 21.3 13.43 66.2 20.37 Conduct Non-COA 25.37 68.16 6.47 23.88 66.67 9.45 COA 13.89 64.81 21.3 15.74 62.96 21.3 Academic Non-COA 20.9 63.18 15.92 24.38 61.69 13.93 COA 7.87 77.78 14.35 7.87 78.7 13.43 Overall Non-COA 10.95 81.59 7.46 11.44 81.59 6.97

COA = children of alcoholics; non-COA = children of nonalcoholics.

586

A.C. Carle, L. Chassin / Applied Developmental Psychology 25 (2004) 577595

the conduct/rule-abiding and academic competence domains, parental alcoholism diminished the likelihood of highly competent performance for children of alcoholic parents and increased the likelihood of low-competent performance. No significant effects of parental alcoholism were found at either wave of measurement for social or overall competence. 3.3. Relation of internalizing symptomatology to competence across parental alcoholism status The relation of internalizing symptomatology to competence across parental alcoholism status was addressed using separate OLS regression equations for each competence domain. Time 3 internalizing symptomatology scores were initially regressed onto Time 2 competence, parental alcoholism, and three covariates (gender, age, and SES). Only a main effect for gender was significant in each of the models. The remaining covariates were trimmed, and the models were rerun. Table 3 presents the zero-order correlation coefficients for the variables included in the model. Effect coding, also called deviation coding, compared each groups average Time 3 internalizing to the Time 3 internalizing grand mean. Under the effect coding, a positive coefficient indicated that a group mean was higher than the grand mean, while a negative coefficient reflected a group mean lower than the grand mean. The interaction between competence group classification and parental alcoholism status examined the possibility that the relation between competence and Time 3 internalizing symptomatology differed for children of alcoholic parents as compared with children of nonalcoholic parents. Using the methods suggested by Tabachnick and Fidell (1996), no evidence of multicolinearity or influential observations was found. For the social and the academic competence regression models, Time 3 internalizing was not significantly related to Time 2 competence, parental alcoholism, or the parental alcoholism status by

Table 3 Zero-order correlations for regression model dependent variables (Time 3 internalizing symptomatology and Time 3 positive affect) and independent variables (gendera, competence classificationb, and parental alcoholism statusc) Time 3 internalizing symptomatology Gender Time 2 internalizing symptomatology Time 2 social competence group Time 2 conduct competence group Time 2 academic competence group Time 2 overall competence group Parental alcoholism Time 3 positive affect T3 social competence group T3 conduct competence group T3 academic competence group T3 overall competence group Parental alcoholism Females = 0, Males = 1. Low competent = 0; competent = 1; high competent = 2. c COA = 1; non-COA = 0. *p b .05. **p b .01.

b a

0.25** 0.60** 0.13** 0.31** 0.02 0.20** 0.13**

0.25** 0.25** 0.13** 0.11* 0.09

A.C. Carle, L. Chassin / Applied Developmental Psychology 25 (2004) 577595

587

competence interaction, controlling for other variables included in the model. In each of the models, levels of internalizing at Time 2 were significantly related to levels of internalizing at Time 3 such that lower levels of internalizing at Time 2 predicted lower levels of internalizing at Time 3, and girls reported significantly higher levels of internalizing symptoms than did boys. For both the conduct/rule-abiding and overall competence domains, there was a significant relation between Time 2 competence and Time 3 internalizing, controlling for other variables in the model. Classification as highly competent at Time 2 significantly predicted lower levels of Time 3 internalizing symptomatology over and above the contribution of Time 2 internalizing symptomatology and the remaining variables in the model. At Time 3, low-competent children reported the highest levels of internalizing symptomatology on average (conduct/rule-abiding competence model: M = 0.82; overall competence model: M = 0.41). There was no significant interaction between Time 2 competence and parental alcoholism. For both of these models, Time 2 internalizing symptomatology significantly predicted Time 3 internalizing symptomatology, and girls reported more internalizing symptoms than did boys. Table 4 summarizes these results. 3.4. Relation of positive affect to competence across parental alcoholism status This question also employed separate OLS regression equations for each competence domain. The study measured positive affect at Time 3 only. As such, Time 3 positive affect was initially regressed onto Time 3 competence, parental alcoholism, and three covariates (gender, age, and SES).2 No main effects or interactions were significant for these covariates; they were trimmed, and the models were rerun. Table 3 presents the zero-order correlation coefficients for the variables included in the model. Effect codes compared each competence groups average positive affect to the positive affect grand mean. The interaction between competence group classification and parental alcoholism status tested whether the relation between competence and positive affect differed for children of alcoholic parents as compared with children of nonalcoholic parents. No evidence of multicolinearity or influential observations was found. For the social and overall competence domains, results showed a significant relationship between parental alcoholism status and positive affect. Children without alcoholic parents reported significantly greater levels of positive affect than did children of alcoholic parents. This effect was not present in the conduct/rule-abiding or academic competence regression models. For the social, conduct/rule-abiding, and overall competence models, there was a significant relation between positive affect and competence, controlling for other variables in the model. Classification as highly competent was significantly related to greater levels of positive affect for the social and conduct/ rule-abiding competence models, as well as the overall competence model. Classification as lowcompetent was significantly related to lower levels of positive affect, such that highly competent children reported the most positive affect and low-competent children reported the lowest levels of positive affect. There was no significant interaction between competence and parental alcoholism. For academic competence, there were no significant effects for competence, parental alcoholism status, or the interaction between parental alcoholism and academic competence. Table 5 summarizes these results.

The analyses were cross-sectional because positive affect was not measured at Time 2.

588 A.C. Carle, L. Chassin / Applied Developmental Psychology 25 (2004) 577595 Table 4 Regression analyses predicting Time 3 internalizing symptomatology from Time 2 competence domains, including Time 2 internalizing symptomatology (N = 417) Variable Social B SD B t g2 B Gender 0.41 0.12 3.32** Time 2 internalizing 0.58 0.04 13.5** Highly competent group 0.30 0.18 1.69 Low-competent group 0.09 0.17 0.50 Parental alcoholism 0.00 0.16 0.01 status (PAS) PAS Highly competent 0.34 0.25 1.35 PAS Low competent 0.02 0.24 0.34 *p b .05. **p b .01. Regression statistics for Time 3 internalizing symptomatology Conduct SD B t g2 B 0.02 0.52 0.13 4.13** 0.28 0.55 0.05 11.78** 0.00 0.39 0.16 2.38* 0.00 0.13 0.15 0.89 0.00 0.07 0.16 0.41 0.00 0.00 0.11 0.23 0.02 0.27 0.51 0.09 Academic SD B t g2 B 0.03 0.41 0.12 3.35** 0.21 0.59 0.04 13.99** 0.01 0.16 0.16 0.94 0.00 0.15 0.15 1.02 0.00 0.2 0.14 1.39 0.00 0.28 0.22 1.28 0.00 0.20 0.22 0.94 Overall SD B t g2 0.02 0.26 0.01 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.02 0.44 0.12 3.64** 0.30 0.57 0.04 13.06** 0.00 0.47 0.22 2.16* 0.00 0.14 0.18 0.78 0.00 0.06 0.19 0.3 0.00 0.23 0.29 0.79 0.00 0.09 0.29 0.31

A.C. Carle, L. Chassin / Applied Developmental Psychology 25 (2004) 577595

Table 5 Regression analyses predicting Time 3 positive affect from Time 3 competence (N = 417) Variable Social B Highly competent group 0.61 Low-competent group 0.83 Parental alcoholism status (PAS) 0.37 PAS Highly competent 0.01 PAS Low competent 0.21 *p b .05. **p b .01. SD B t g2 B 0.18 3.35** 0.18 4.56** 0.18 2.03* 0.29 0.05 0.27 0.75 Regression statistics for Time 3 positive affect Conduct SD B t g2 B 0.03 0.69 0.20 3.48** 0.05 0.75 0.18 4.26** 0.01 0.27 0.18 1.45 0.00 0.17 0.27 0.63 0.00 0.41 0.29 1.40 Academic SD B t g2 B 0.03 0.31 0.19 1.65 0.04 0.30 0.17 1.72 0.00 0.14 0.17 0.82 0.00 0.07 0.26 0.26 0.00 0.09 0.27 0.32 0.01 0.51 0.01 0.83 0.00 0.59 0.00 0.16 0.00 0.40 Overall SD B t g2 0.01 0.03 0.02 0.00 0.00 0.25 2.02* 0.22 3.80** 0.23 2.59* 0.35 0.45 0.36 1.14

589

590

A.C. Carle, L. Chassin / Applied Developmental Psychology 25 (2004) 577595

4. Discussion The first goal of this study was to examine the prevalence of competence in a community sample of children of alcoholic parents and compare these rates to those of children of nonalcoholic parents. Competent children of alcoholic parents were identified in each of the three domains, demonstrating that substantial subgroups of children of alcoholic parents showed competent performance despite elevated risk. However, although subgroups of children of alcoholic parents were identified as resilient, there were also systematic effects of parental alcoholism on the prevalence of competent performance. As compared with children of nonalcoholic parents, children of alcoholic parents were less likely to perform in a highly competent manner in both the conduct/rule-abiding and academic domains and more likely to be performing in a low-competent manner. These findings suggest that the effects of parental alcoholism on competent performance reflect a general shift in the distribution of competent behavior in these domains, such that children of alcoholic parents are less likely to be highly competent and more likely to be low-competent in the academic and rule-abiding behavior. Several possible explanations exist for these findings. Alcoholic families are often characterized by increased dysfunctional interactions (Sher, 1991). These interactions may interfere with the ability children of alcoholic parents to observe and learn conduct/rule-abiding behavior. They may also interfere with the ability of children of alcoholic parents to devote time to academic study. Children of alcoholic parents are also less likely to receive parental monitoring and discipline. Alcoholic parents failure to monitor their childrens academic progress and conduct/rule-abiding behavior may also lead to decreased likelihood of highly competent performance. Other authors (Giancola & Mezzich, 2000; Shoal & Giancola, 2001) have noted that children with a positive family history of substance abuse suffer from cognitive deficits, e.g., impaired executive functioning. These impairments may also lead to decreased academic competence and difficulties in learning conduct/rule-abiding behavior. Finally, other authors have also noted genetic pathways for the negative effects of parental alcoholism (McGue, 1997) that may predispose children of alcoholic parents to poor self-regulation. In sum, a number of factors may lead to the decreased likelihood that children of alcoholic parents model, develop, and master highly competent rule-abiding and academic performance and similarly contribute to the increased likelihood of low-competent performance in these domains. Interestingly, no significant differences were found in the social competence domain. These data are consistent with previous research suggesting similar levels of sociability and extraversion between children of alcoholic parents and their peers (Sher, 1997). Although children of alcoholic parents generally demonstrate increased neuroticism, negative emotionality, impulsivity, and disinhibition, they are similar to their peers in levels of sociability and extraversion. Parental alcoholism may affect the development of highly competent conduct/rule-abiding behavior and academic performance in children of alcoholic parents, but it does not appear to affect the ability of children of alcoholic parents to develop and engage in friendships. However, while the social competence domain reflects peer and friendship development, it does not reflect the content of activities. Two children could endorse similarly high levels of peer involvement, while one engaged in positive social activities and the other engaged in deviant social activities. Both children would be considered socially competent. Likewise, the dpositiveT and dnegativeT aspects of friends are not assessed. Two children could endorse a similar number of friends, while one childs social network consisted almost entirely of deviant peers and the others did not. Again, both children

A.C. Carle, L. Chassin / Applied Developmental Psychology 25 (2004) 577595

591

would be considered socially competent. Given their low levels of rule-abiding behavior, children of alcoholic parents may be able to develop and engage in friendships, but the type of friendships and activities that children of alcoholic parents and children of nonalcoholic parents engage in may differ. Thus, parental alcoholism may not interfere with the development of a childs ability to make friends and engage in social activities while it may interfere with the development of the childs ability to follow rules and engage in nondeviant behaviors with their peers, a possibility consistent with the suggestion of Sher (1997) that sociability may lead to children of alcoholic parents involvement in deviant social activities. A second goal of this study was to examine the relation of resilience to internalizing symptomatology and positive affect, elucidating whether endeavors to encourage competent behavior in children might lead to comparable positive changes in mental health. For both the conduct/rule-abiding and overall competence domains, competent performance was significantly associated with decreased levels of internalizing symptomatology, over and above the effects of previous internalizing symptomatology for some domains. For other domains (social and academic competence), no prospective relationship was found. Similar findings occurred with respect to positive affect. Highly competent children in the social, conduct/rule-abiding, and overall competence domains endorsed higher levels of positive affect. Importantly, no significant interactions were found in any of the regression models. The relation between competence, internalizing symptomatology, and positive affect did not differ for children at risk as compared with controls. Resilience was not associated with negative emotional adjustment, in direct contrast to the findings reported by Luthar (1991) and Luthar et al., (1993), but similar to those of Masten et al. (1999). Several explanations for the divergence in findings are possible. First, differences may be, in part, due to methodological differences across the studies. Luthars studies (Luthar, 1991; Luthar et al., 1993) included a sample of inner-city children, risk was assessed using measures of life stress, and included different measures of competence. The current study utilized a community sample, and risk was assessed by parental alcoholism. Perhaps, for inner-city children experiencing increased levels of stress, competent behavior may be more deviant than normative, such that competence is associated with increased social stress on the child and increased internalizing symptomatology results. However, in a community sample of children of alcoholic parents, competent behavior may not be deviant and thus may not add to increased stress and costs for the child. Consistent with a pleasure in mastery explanation, Masten et al. (1999) found that resilient children more closely resembled their competent peers than they did maladaptive children. Incorporating a longitudinal design, data from the current study provide further empirical support for this theory. To the degree that children experience dpleasure in mastery,T one would expect competent performance to be associated with increased levels of positive affect and decreased levels of internalizing symptomatology. These findings are particularly relevant to the literature concerning children of alcoholic parents. Competent (i.e., resilient) children of alcoholic parents generally endorsed lower levels of internalizing symptomatology and higher levels of positive affect than did low-competent children of alcoholic parents, in direct contrast to the ideas suggested by the bhero childQ hypothesis, information that may help guide clinical work with children of alcoholic parents. Finally, it is important to note some of the studys limitations. First, the comparisons involving positive affect were examined cross-sectionally, limiting inference about the direction of effects. Second, the study characterized social competence mainly in terms of childrens ability to make

592

A.C. Carle, L. Chassin / Applied Developmental Psychology 25 (2004) 577595

friends and engage in social activities and was unable to explore the quality of those friendships. Third, although the regression models had adequate power to detect small effect sizes (Cohen & Cohen, 1983), there was only moderate power to detect the particularly small effect sizes associated with the interaction terms in the models. Fourth, the study measured competence with a different set of items than either the Luthar (Luthar, 1991; Luthar et al., 1993) or Masten et al. (1999) studies, limiting the ability to make comparisons across the studies. Finally, the current study did not explore the possible mechanisms leading to resilient outcomes in children of alcoholic parents. Identifying these mechanisms may help clinicians to develop potential prevention and intervention strategies for children of alcoholic parents. Future studies may benefit by addressing these concerns. In sum, the current study identified a subset of resilient children of alcoholic parents performing at both high and average competence levels in multiple domains and cautions against overpathologizing this heterogeneous group. However, for both the conduct/rule-abiding and academic competence domains, fewer children of alcoholic parents performed in a highly competent manner than did the controls, and greater numbers of children of alcoholic parents performed in a low-competent manner than controls did. No significant differences were found for social competence, suggesting that, while parental alcoholism interferes with the development of the ability to follow rules, engage in nondeviant behaviors, and perform well academically, it may not interfere with the development of childrens ability to make friends and engage in social activities when they have alcoholic parents. Results also suggested a relation between competent behavior, internalizing symptomatology, and positive affect. Generally, highly competent children demonstrated fewer internalizing symptoms and endorsed increased levels of positive affect. This relation did not differ for children of alcoholic parents (i.e., resilient children) and controls, providing further support that resilience may be associated with increased effects on positive mental health and is not associated with negative effects on mental health. This suggests that children of alcoholic parents may benefit from efforts to promote competent behavior and that prevention and intervention efforts aimed at increasing competent behavior in children of alcoholic parents may not come at a cost to the childs mental health. Rather, efforts to encourage competent performance in children of alcoholic parents should be associated with decreased internalizing symptomatology and increased positive affect, serving to increase positive mental health for children of alcoholic parents.

Acknowledgements This study was supported by Grant DA05227 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse awarded to Dr. Laurie Chassin. We would like to thank Tara J. Carle and Margaret Carle for their unending support.

References

Achenbach, T., & Edelbrock, C. (1983). Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and revised child behavior profile. Burlington, VT7 University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. Chassin, L., Barrera, M., Bech, K., & Kossak-Fuller, J. (1992). Recruiting a community sample of adolescent children of alcoholics: A comparison of three subject sources. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 53, 316 320.

A.C. Carle, L. Chassin / Applied Developmental Psychology 25 (2004) 577595

593

Chassin, L., Rogosch, F., & Barrera Jr., M. (1991). Substance use and symptomatology among adolescent children of alcoholics. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 1 15. Cicchetti, D., & Garmezy, N. (1993). Prospects and promises in the study of resilience. Development and Psychopathology, 5, 497 502. Cicchetti, D., & Rogosch, F. (1997). The role of self-organization in the promotion of resilience in maltreated children. Development and Psychopathology, 9(4), 797 815. Cohen, J., & Cohen, P. (1983). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ7 Erlbaum. Cowen, E. (1991). In pursuit of wellness. American Psychologist, 46(4), 404 408. Cowen, E., & Work, W. (1988). Resilient children, psychological wellness, and primary prevention. American Journal of Community Psychology, 16(4), 591 607. Endicott, J., Anderson, N., & Spitzer, R. L. (1975). Family history diagnostic criteria. New York7 New York Biometrics Research, New York Psychiatric Institute. Farrell, M., Barnes, G., & Banerjee, S. (1995). Family cohesion as a buffer against the effects of problem-drinking fathers on psychological distress, deviant behavior, and heavy drinking in adolescence. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36, 377 385. Garmezy, N. (1981). Children under stress: Perspectives on antecedents and correlates of vulnerability and resistance to psychopathology. In A. I. Robin, J. Aronoff, & R. A. Zucker (Eds.), Further exploration in personality (pp. 196 269). New York7 Wiley. Garmezy, N. (1984). Risk and protective factors in children vulnerable to major mental disorders. In L. Greenspoon (Ed.), Psychiatry 1983, Vol. 3. (pp. 91 104). Washington, DC7 American Psychiatric Press. Garmezy, N. (1985). Stress resistant children: The search for protective factors. In J. E. Stevenson (Ed.), Recent research in developmental psychopathology. Journal of Psychology and Psychiatry, Book Supplement (pp. 212 233). Oxford7 Pergamon. Garmezy, N., & Neuchterlein, K. (1972). Invulnerable children: The fact and fiction of competence and disadvantage. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 42, 328 329. Giancola, P. R., & Mezzich, A. C. (2000). Neurological deficits in female adolescents with a substance use disorder: Better accounted for by conduct disorder? Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 61(6), 809 817. Grant, B. (2000). Estimates of US children exposed to alcohol abuse and dependence in the family. American Journal of Public Health, 90, 112 115. Helzer, J. E., & Pryzbeck, T. R. (1988). The co-occurrence of alcoholism with other psychiatric disorders in the general population and its impact on treatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 49(3), 219 224. Hetherington, E. M., & Stanley-Hagan, M. (1999). The adjustment of children with divorced parents: A risk and resiliency perspective. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40(1), 129 140. Hinz, L. (1990). College student adult children of alcoholics: Psychological resilience or emotional distance? Journal of Substance Abuse, 2, 449 457. Hussong, A. M., & Chassin, L. (1997). Substance use initiation among adolescent children of alcoholics: Testing protective factors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 58(3), 272 279. Jastak, S., & Wilkinson, G. S. (1984). The wide range achievement testRevised: Administration manual. Wilmington, DL7 Jastak Associates. Karno, M., Hough, R., Burnam, A. M., Escobar, J. I., Timbers, D. M., Santana, F., et al. (1987). Lifetime prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders among Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic Whites in Los Angeles. Archives of General Psychiatry, 44(8), 695 701. Kraemer, H., Kazdin, A., Offord, D., Kessler, R., Jensen, P., & Kupfer, D. (1997). Coming to terms with the terms of risk. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54, 337 343. Luthar, S. (1991). Vulnerability and resilience: A study of high-risk adolescents. Child Development, 62, 613 616. Luthar, S. (1995). Annotation: Methodological and conceptual issues in research on childhood resilience. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 34(4), 441 453. Luthar, S. (1999). Poverty and childrens adjustment . Thousand Oaks, CA7 Sage Publications. Luthar, S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71, 543 562.

594

A.C. Carle, L. Chassin / Applied Developmental Psychology 25 (2004) 577595

Luthar, S., Doernberger, C. H., & Zigler, E. (1993). Resilience is not a unidimensional construct: Insights from a prospective study of inner-city adolescents. Development and Psychopathology, 5, 703 717. Luthar, S., & Zigler, E. (1991). Vulnerability and competence a review of research on resilience in childhood. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 61, 6 22. Masten, A., & Coatsworth, D. (1995). Competence, resilience, and psychopathology. In D. Cicchetti, & D. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology. Risk, disorder, and adaptation (Vol. 2, pp. 715 752). New York7 John Wiley and Sons. Masten, A. S. (1990). Resilience in development: Implications of the study of successful adaptation for developmental psychopathology. In D. Cicchetti (Ed.), The emergence of a discipline (pp. 261 294). Mahwah, NJ7 Erlbaum. Masten, A. S., Best, Karin M., & Garmezy, N. (1990). Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Development and Psychopathology, 2, 424 444. Masten, A. S., Coatsworth, J. D., Neemann, J., Gest, S. D., Tellegen, A., & Garmezy, N. (1995). The structure and coherence of competence from childhood through adolescence. Child Development, 66, 1635 1659. Masten, A. S., Hubbard, J. J., Gest, S. D., Tellegen, A., Garmezy, N., & Ramirez, M. L. (1999). Competence in the context of adversity: Pathways to resilience and maladaptation from childhood to late adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 11, 143 169. McGue, M. (1997). A behavioralgenetic perspective on children of alcoholics. Alcohol Health and Research World, 21, 210. McGue, M., Sharma, A., & Benson, P. (1996). Parent and sibling influences on adolescent alcohol use and misuse: Evidence from a U.S. adoption cohort. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 57, 8 18. Moos, R. H., & Billings, A. G. (1982). Children of alcoholics during the recovery process: Alcoholic and matched control families. Addictive Behaviors, 7, 155 163. Richters, J. E., & Martinez, P. E. (1993). Violent communities, family choices, and childrens chances: An algorithm for improving the odds. Development and Psychopathology, 5(4), 609 627. Robins, L. N., Helzer, J. E., Croughan, J., & Ratcliff, K. S. (1981). National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: Its history, characteristics, and validity. Archives of General Psychiatry, 38, 381 389. Robins, L. N., Helzer, J. E., Weissman, M. M., Orvaschel, H., Gruenberg, E., Burke Jr., J. D., et al. (1984). Lifetime prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders in three sites. Archives of General Psychiatry, 41(10), 949 958. Roosa, M. W., Sandler, I. N., Beals, J., & Short, J. T. (1988). Risk status of adolescent children of problem drinking parents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 16, 225 238. Rutter, M. (1979). Protective factors in childrens responses to stress and disadvantage. In M. W. Kent, & J. E. Rolf (Eds.), Primary prevention of psychopathology. Social competence in children (Vol. 3, pp. 49 74). Hanover, NH7 University Press of New England. Sher, K. J. (1991). Children of alcoholics: A critical appraisal of theory and research. Chicago7 University of Chicago Press. Sher, K. J. (1997). Psychological characteristics of children of alcoholics. Alcohol Research World, 21, 247. Shoal, G. D., & Giancola, P. R. (2001). Cognition, negative affectivity and substance use in adolescent boys with and without a family history of substance use disorder. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 62(5), 675 686. Tabachnick, B., & Fidell, L. (1996). Using multivariate statistics. New York7 HarperCollins College Publishers. Tubman, J. G. (1993). A pilot study of school-age children of men with moderate to severe alcohol dependence: Maternal distress and child outcomes. Journal of Child Psychiatry, 34, 729 741. Tweed, S., & Ryff, C. (1989). Adult children of alcoholics: Profiles of wellness amidst distress. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 52, 133 141. Watson, E., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063 1070. Wells, R. D., & Schwebel, A. I. (1987). Chronically ill children and their mothers: Predictors of resilience and vulnerability to hospitalization and surgical stress. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 8(2), 83 89. Werner, E. (1993). Risk, resilience, and recovery: Perspectives from the Kauai longitudinal study. Development and Psychopathology, 5, 503 515. Werner, E. E., & Smith, R. S. (1982). Vulnerable but invincible: A study of resilient children. New York7 McGraw-Hill.

A.C. Carle, L. Chassin / Applied Developmental Psychology 25 (2004) 577595

595

West, M. O., & Prinz, R. J. (1987). Parental alcoholism and childhood psychopathology. Psychological Bulletin, 102, 204 218. Wright, M. O., Masten, A. S., Northwood, A., & Hubbard, J. J. (1997). Long term effects of massive trauma: Developmental and psychobiological perspectives. In D. Cicchetti, & S. Toth (Eds.), Rochester symposium on developmental psychopathology (pp. 181 225). Rochester, NY7 Rochester University Press.

Você também pode gostar

- Resilience in Children of AlcoholicsDocumento6 páginasResilience in Children of Alcoholicsdoc_parkerAinda não há avaliações

- Risk and Protective Factors for Disruptive Behavior DisordersDocumento11 páginasRisk and Protective Factors for Disruptive Behavior DisordersAlex BoncuAinda não há avaliações

- Family Adaptation, Coping and Resources Parents of Children With Developmental Disabilities and Behaviour ProblemsDocumento16 páginasFamily Adaptation, Coping and Resources Parents of Children With Developmental Disabilities and Behaviour ProblemsVictor Hugo EsquivelAinda não há avaliações

- Associations Among The Perceived Parent-Child Relationship, Eating Behavior, and Body Weight in Preadolescents: Results From A Community-Based SampleDocumento11 páginasAssociations Among The Perceived Parent-Child Relationship, Eating Behavior, and Body Weight in Preadolescents: Results From A Community-Based SamplefpfoAinda não há avaliações

- ABAv EclecticDocumento31 páginasABAv EclecticIcaro De Almeida VieiraAinda não há avaliações

- Mullins 2015Documento14 páginasMullins 2015DeepaAinda não há avaliações

- Nelson 2003Documento16 páginasNelson 2003winxukaAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal Stunting 3 B.ingDocumento19 páginasJurnal Stunting 3 B.ingAmel afriAinda não há avaliações

- Psychological Effects of Chronic DiseaseDocumento15 páginasPsychological Effects of Chronic DiseaseYasmine GreenAinda não há avaliações

- Parenting Stress Among Caregivers of Children With Chronic IllnessDocumento21 páginasParenting Stress Among Caregivers of Children With Chronic IllnessZuluaga LlanedAinda não há avaliações

- CAPA - Parent Child Relationship ScaleDocumento9 páginasCAPA - Parent Child Relationship ScaleAJAinda não há avaliações

- Final Research ProposalDocumento18 páginasFinal Research Proposalapi-720370980Ainda não há avaliações

- Meta-Analysis of Comparative Studies of Depression in Mothers of Children With and Without Developmental DisabilitiesDocumento15 páginasMeta-Analysis of Comparative Studies of Depression in Mothers of Children With and Without Developmental DisabilitiesLudmila MenezesAinda não há avaliações

- Assessing Early Adverse Experiences in Home Visiting ProgramsDocumento20 páginasAssessing Early Adverse Experiences in Home Visiting Programsrosan quimcoAinda não há avaliações

- A Comparison Intensive Behavior Analytic Eclectic Treatments For Young Children AutismDocumento25 páginasA Comparison Intensive Behavior Analytic Eclectic Treatments For Young Children AutismRegina TorresAinda não há avaliações

- 2004 Psychosocial Determinants of Behaviour ProblemsDocumento10 páginas2004 Psychosocial Determinants of Behaviour ProblemsMariajosé CaroAinda não há avaliações

- Parentalidad PositivaDocumento17 páginasParentalidad PositivakatherineAinda não há avaliações

- An Investigation of Health Anxiety in FamiliesDocumento12 páginasAn Investigation of Health Anxiety in FamiliesAndreea NicolaeAinda não há avaliações

- Adams - 2018 - Well-Being in Mothers of Children With Rare Genetic SyndromesDocumento13 páginasAdams - 2018 - Well-Being in Mothers of Children With Rare Genetic SyndromesPetrutaAinda não há avaliações

- Content ServerDocumento13 páginasContent ServerMelindaDuciagAinda não há avaliações

- Behavioural, Emotional and Social Development of Children Who StutterDocumento10 páginasBehavioural, Emotional and Social Development of Children Who StutterMagaliAinda não há avaliações

- Psychological Aspects of Childhood Obesity: A Controlled Study in A Clinical and Nonclinical SampleDocumento14 páginasPsychological Aspects of Childhood Obesity: A Controlled Study in A Clinical and Nonclinical SampleKusuma JatiAinda não há avaliações

- Pergamon: Behat,. Res. TherDocumento11 páginasPergamon: Behat,. Res. TherSavio RebelloAinda não há avaliações

- Emotional Co-Regulation Mothers and ChildrenDocumento12 páginasEmotional Co-Regulation Mothers and ChildrenAidee NavaAinda não há avaliações

- Exer 1 Article 2Documento15 páginasExer 1 Article 2ameshia2010Ainda não há avaliações

- Parenting Stress TheoryDocumento9 páginasParenting Stress TheoryPija RamliAinda não há avaliações

- Support, Communication, and Hardiness in Families With Children With DisabilitiesDocumento17 páginasSupport, Communication, and Hardiness in Families With Children With DisabilitiesAnnisa Dwi NoviantyAinda não há avaliações

- Impact of Family Pathology On Behavioura PDFDocumento12 páginasImpact of Family Pathology On Behavioura PDFAshok KumarAinda não há avaliações

- The Swiss Teaching Style Questionnaire STSQ and AdDocumento9 páginasThe Swiss Teaching Style Questionnaire STSQ and AdBryan GarciaAinda não há avaliações

- Collishaw Et Al. (2007)Documento49 páginasCollishaw Et Al. (2007)voooAinda não há avaliações

- Incredible Years ProgramDocumento11 páginasIncredible Years ProgramKallia KoufakiAinda não há avaliações

- Clausen1998 Article MentalhealthproblemsofchildrenDocumento14 páginasClausen1998 Article Mentalhealthproblemsofchildrenapi-450136628Ainda não há avaliações

- Measures of Infant Behavioral and Physiological State Regulation Predict 54-Month Behavior Problems, 2011Documento14 páginasMeasures of Infant Behavioral and Physiological State Regulation Predict 54-Month Behavior Problems, 2011MacavvAinda não há avaliações

- The Role of Mental Health Factors and Program Engagement in The Effectiveness of A Preventive Parenting Program For Head Start MothersDocumento21 páginasThe Role of Mental Health Factors and Program Engagement in The Effectiveness of A Preventive Parenting Program For Head Start MothersAncuta InnaAinda não há avaliações

- Preventopn 2Documento9 páginasPreventopn 2Christine BlossomAinda não há avaliações

- Sandler 1994Documento21 páginasSandler 1994Raluca PopescuAinda não há avaliações

- 5 Dileo Et Al. - 2017 - Investigating The Neurodevelopmental Mediators ofDocumento24 páginas5 Dileo Et Al. - 2017 - Investigating The Neurodevelopmental Mediators ofSuzie Simone Mardones SilvaAinda não há avaliações

- RS, 5-7Documento33 páginasRS, 5-7Suzie Simone Mardones SilvaAinda não há avaliações

- Resilience and Vulnerability in Very Preterm 4-Year-Olds PDFDocumento22 páginasResilience and Vulnerability in Very Preterm 4-Year-Olds PDFjuan RamosAinda não há avaliações

- Protecting Children From The Consequences of Divorce: A Longitudinal Study of The Effects of Parenting On Children's Coping ProcessesDocumento15 páginasProtecting Children From The Consequences of Divorce: A Longitudinal Study of The Effects of Parenting On Children's Coping ProcessesAndreea BălanAinda não há avaliações

- Attachment and Emotion in School-Aged Children Borelli Emotion 2010Documento11 páginasAttachment and Emotion in School-Aged Children Borelli Emotion 2010LisaDarlingAinda não há avaliações

- Kaminski Clausse (2017)Documento24 páginasKaminski Clausse (2017)Nuria Moreno RománAinda não há avaliações

- Early Risk Factors and Developmental Pathways To Chronic High Inhibition and Social Anxiety Disorder in AdolescenceDocumento47 páginasEarly Risk Factors and Developmental Pathways To Chronic High Inhibition and Social Anxiety Disorder in AdolescenceValian IndrianyAinda não há avaliações

- Gray 1999Documento15 páginasGray 1999Arya PradiptaAinda não há avaliações

- Article Text 14431 1 10 20181015 PDFDocumento22 páginasArticle Text 14431 1 10 20181015 PDFAndreia SilvaAinda não há avaliações

- Equine-Assisted PsychotherapyDocumento8 páginasEquine-Assisted PsychotherapybhasiAinda não há avaliações

- CCP 743401 PDFDocumento15 páginasCCP 743401 PDFteretransproteAinda não há avaliações

- Parenting PaperDocumento7 páginasParenting Paperapi-371262556Ainda não há avaliações

- Positive Impact of ID On FamiliesDocumento19 páginasPositive Impact of ID On FamiliesSylvia PurnomoAinda não há avaliações

- Weisz 1989Documento15 páginasWeisz 1989Laura PalermoAinda não há avaliações

- LoehlinDocumento4 páginasLoehlinzutshidagarAinda não há avaliações

- Resilience in Welfare JournalDocumento12 páginasResilience in Welfare Journalselam abdisaAinda não há avaliações

- Factores Proximais Problemas Mentais MaesDocumento21 páginasFactores Proximais Problemas Mentais Maesminha amoraAinda não há avaliações

- Influence of Parenting Styles On Development ofDocumento6 páginasInfluence of Parenting Styles On Development ofMeta Dwi FitriyawatiAinda não há avaliações

- O24.22.02. Family Well Being and Disabled Children A Psychosocial Model ofDocumento13 páginasO24.22.02. Family Well Being and Disabled Children A Psychosocial Model ofLukas LeAinda não há avaliações

- Hardway2013 Article InfantReactivityAsAPredictorOfDocumento9 páginasHardway2013 Article InfantReactivityAsAPredictorOfJessica Vasquez SalazarAinda não há avaliações

- Positive Parenting Improves Multiple AspectsDocumento11 páginasPositive Parenting Improves Multiple Aspectsjuliana_farias_7Ainda não há avaliações

- Investigating The Relationship Between Teenage Childbearing and Psychological Distress Using Longitudinal EvidenceDocumento17 páginasInvestigating The Relationship Between Teenage Childbearing and Psychological Distress Using Longitudinal EvidenceDrobota MirunaAinda não há avaliações

- Over Medicating Our Youth: The Public Awareness Guide for Add, and Psychiatric MedicationsNo EverandOver Medicating Our Youth: The Public Awareness Guide for Add, and Psychiatric MedicationsAinda não há avaliações

- Children & Adolescents with Problematic Sexual BehaviorsNo EverandChildren & Adolescents with Problematic Sexual BehaviorsNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- 16472Documento11 páginas16472efunctionAinda não há avaliações

- The Use of Electroencephalography in Language Production Research: A ReviewDocumento1 páginaThe Use of Electroencephalography in Language Production Research: A ReviewefunctionAinda não há avaliações

- Germanfuture StevensonDocumento15 páginasGermanfuture StevensonefunctionAinda não há avaliações

- Berger 2007Documento37 páginasBerger 2007efunctionAinda não há avaliações

- Tove Skutnabb Kangas Bilingual Education and Sign Language As The Mother Tongue of Deaf ChildrenDocumento97 páginasTove Skutnabb Kangas Bilingual Education and Sign Language As The Mother Tongue of Deaf ChildrenefunctionAinda não há avaliações

- 21 Failer CivilDocumento10 páginas21 Failer CivilefunctionAinda não há avaliações

- 12 Parry HandbookDocumento18 páginas12 Parry HandbookefunctionAinda não há avaliações

- 1-2007 Schmidt OktataskellDocumento28 páginas1-2007 Schmidt OktataskellefunctionAinda não há avaliações

- Lakoff Johnson80Documento35 páginasLakoff Johnson80Lea VukusicAinda não há avaliações

- The Iconicity of Embodied MeaningDocumento22 páginasThe Iconicity of Embodied MeaningefunctionAinda não há avaliações

- What Is Deafhood'Documento5 páginasWhat Is Deafhood'efunction100% (1)

- Document 163Documento16 páginasDocument 163efunctionAinda não há avaliações

- 8 Clare MountainDocumento13 páginas8 Clare MountainefunctionAinda não há avaliações

- A First Language - Whose Choice Is ItDocumento33 páginasA First Language - Whose Choice Is ItefunctionAinda não há avaliações

- The Origins of Embodied Self: Measuring Parental Embodied MentalisingDocumento24 páginasThe Origins of Embodied Self: Measuring Parental Embodied MentalisingefunctionAinda não há avaliações

- Sheehart 0405Documento107 páginasSheehart 0405efunctionAinda não há avaliações

- Universal Bilingualism June, 99 FinalDocumento57 páginasUniversal Bilingualism June, 99 FinalefunctionAinda não há avaliações

- Patricia 1boyd - Final Formatted ProjectDocumento124 páginasPatricia 1boyd - Final Formatted ProjectefunctionAinda não há avaliações

- Elman MC Clelland 86 Exploiting Lawful VariaDocumento13 páginasElman MC Clelland 86 Exploiting Lawful VariaefunctionAinda não há avaliações

- How Disability Is Depicted in Literary NarrativesDocumento10 páginasHow Disability Is Depicted in Literary NarrativesAlejandro Jimenez ArevaloAinda não há avaliações

- Interaction Between Research ParticipentsDocumento20 páginasInteraction Between Research ParticipentshareeshdoctusAinda não há avaliações

- Pienemann 2005Documento73 páginasPienemann 2005Charles CorneliusAinda não há avaliações

- Bolt IntroductionDocumento6 páginasBolt IntroductionefunctionAinda não há avaliações

- Murray On Autistic Presence 2008Documento10 páginasMurray On Autistic Presence 2008efunctionAinda não há avaliações

- From The Mute God To The Lesser GodDocumento16 páginasFrom The Mute God To The Lesser GodefunctionAinda não há avaliações

- Town Waits and Their TunesDocumento34 páginasTown Waits and Their TunesefunctionAinda não há avaliações

- Gender and DisabilityDocumento14 páginasGender and DisabilityefunctionAinda não há avaliações

- Reactive DyeingDocumento23 páginasReactive Dyeingshivkalia8757100% (2)

- Science and Technology Study Material For UPSC IAS Civil Services and State PCS Examinations - WWW - Dhyeyaias.comDocumento28 páginasScience and Technology Study Material For UPSC IAS Civil Services and State PCS Examinations - WWW - Dhyeyaias.comdebjyoti sealAinda não há avaliações

- Sales & Distribution Management Presentation NewDocumento35 páginasSales & Distribution Management Presentation NewVivek Sinha0% (1)

- Business Ethics and Social ResponsibilityDocumento16 páginasBusiness Ethics and Social Responsibilitytitan abcdAinda não há avaliações

- The New York Times OppenheimerDocumento3 páginasThe New York Times Oppenheimer徐大头Ainda não há avaliações

- Astrolada - Astrology Elements in CompatibilityDocumento6 páginasAstrolada - Astrology Elements in CompatibilitySilviaAinda não há avaliações

- Verify File Integrity with MD5 ChecksumDocumento4 páginasVerify File Integrity with MD5 ChecksumSandra GilbertAinda não há avaliações

- Political Education and Voting Behaviour in Nigeria: A Case Study of Ogbadibo Local Government Area of Benue StateDocumento24 páginasPolitical Education and Voting Behaviour in Nigeria: A Case Study of Ogbadibo Local Government Area of Benue StateMohd Noor FakhrullahAinda não há avaliações

- Archana PriyadarshiniDocumento7 páginasArchana PriyadarshiniJagriti KumariAinda não há avaliações

- SF3300Documento2 páginasSF3300benoitAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 3 Lesson 2 Video Asa Aas HL NotesDocumento2 páginasUnit 3 Lesson 2 Video Asa Aas HL Notesapi-264764674Ainda não há avaliações

- 12soal Uas - K.99 - Raditya - Bahasa Inggris Hukum (1) - 1Documento3 páginas12soal Uas - K.99 - Raditya - Bahasa Inggris Hukum (1) - 1Brielle LavanyaAinda não há avaliações

- 4045CA550 PowerTech PSS 4 5L Atlas Copco OEM Engine Stage V IntroductionDocumento9 páginas4045CA550 PowerTech PSS 4 5L Atlas Copco OEM Engine Stage V IntroductionSolomonAinda não há avaliações

- Management of Chronic ITP: TPO-R Agonist Vs ImmunosuppressantDocumento29 páginasManagement of Chronic ITP: TPO-R Agonist Vs ImmunosuppressantNiken AmritaAinda não há avaliações

- Fracture Mechanics HandbookDocumento27 páginasFracture Mechanics Handbooksathya86online0% (1)

- W1 PPT ch01-ESNDocumento21 páginasW1 PPT ch01-ESNNadiyah ElmanAinda não há avaliações

- Interventional Radiology & AngiographyDocumento45 páginasInterventional Radiology & AngiographyRyBone95Ainda não há avaliações

- Wa0000.Documento6 páginasWa0000.Sanuri YasaraAinda não há avaliações

- DCIT 21 & ITECH 50 (John Zedrick Iglesia)Documento3 páginasDCIT 21 & ITECH 50 (John Zedrick Iglesia)Zed Deguzman100% (1)

- Dealing in Doubt 2013 - Greenpeace Report On Climate Change Denial Machine PDFDocumento66 páginasDealing in Doubt 2013 - Greenpeace Report On Climate Change Denial Machine PDFŦee BartonAinda não há avaliações

- Reading SkillsDocumento37 páginasReading SkillsShafinaz ZhumaAinda não há avaliações

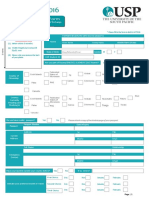

- Jene Sys 2016 ApplicationformDocumento4 páginasJene Sys 2016 ApplicationformReva WiratamaAinda não há avaliações

- Reviews On IC R 20Documento5 páginasReviews On IC R 20javie_65Ainda não há avaliações

- Preparedness of Interns For Hospital Practice Before and After An Orientation ProgrammeDocumento6 páginasPreparedness of Interns For Hospital Practice Before and After An Orientation ProgrammeTanjir 247Ainda não há avaliações

- CNS - Types of CiphersDocumento47 páginasCNS - Types of Ciphersmahesh palemAinda não há avaliações

- Teaching Position DescriptionDocumento9 páginasTeaching Position DescriptionBrige SimeonAinda não há avaliações

- Housekeeping ProcedureDocumento3 páginasHousekeeping ProcedureJeda Lyn100% (1)

- Pavement Design and Maintenance: Asset Management Guidance For Footways and Cycle RoutesDocumento60 páginasPavement Design and Maintenance: Asset Management Guidance For Footways and Cycle RoutesGaneshmohiteAinda não há avaliações

- Khurda 2Documento6 páginasKhurda 2papiraniAinda não há avaliações

- William Shakespeare PDFDocumento2 páginasWilliam Shakespeare PDFmr.alankoAinda não há avaliações