Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Cooperative Education Interventions Aimed at Transferring New Technologies From A Developed To A Developing Economy: Germany/South African Collaboration in The Automotive Industry

Cooperative Education Interventions Aimed at Transferring New Technologies From A Developed To A Developing Economy: Germany/South African Collaboration in The Automotive Industry

Enviado por

Vivi Sabrina BaswedanDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Cooperative Education Interventions Aimed at Transferring New Technologies From A Developed To A Developing Economy: Germany/South African Collaboration in The Automotive Industry

Cooperative Education Interventions Aimed at Transferring New Technologies From A Developed To A Developing Economy: Germany/South African Collaboration in The Automotive Industry

Enviado por

Vivi Sabrina BaswedanDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Co-op Education

employer

Essay

AsiaPacific Journal of Cooperative Education

ca edu tor

Received 16 October 2001; accepted in revised from 19 March 2002

South Africa, like many other developing countries is facing the consequences of globalization. Globalization represents a significant challenge for the Republic. In this article three models of intervention that seek to transfer technologies from a developed to a developing country are described. The author suggests that these models provide a working infrastructure for the exchange of students between two countries and significantly advances students understanding for both technical and non-technical skills (Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 2002, 3(1), 13-17). Keywords: South Africa; Germany; globalization; international exchange

lobalization can be described as the increasing integration of various sectors in todays world resulting from the revolution in communication technology and progressive lowering of trade barriers (Globalization, 2001, June 7). Its most striking aspect is the way big companies have now become international rather than national role players within a global economy and seem to have more power than some governments in the countries they operate in. Big multi-national companies account for about a fifth of world output and 70 percent of global trade (Globalization, 2001, June 7). The economic gap between developed economies and developing economies has grown much wider as a result of globalization. In 1960, the average per capita gross domestic product in the 20 richest countries in the world was 15 times that of the poorest 20. Today with globalization the economic gap has widened to 30 times, because the richest countries have on average, grown much faster than the poorest ones. Much of this disparity is often blamed on large multinational companies (Globalization, 2001, June 7). With South Africas emergence from political and economic isolation since 1994, its economy has not remained immune from the effects of globalization (Department of Labour [DoL], 2000). The inability of certain industries to remain competitive in the worldwide market has resulted in their closure and increasing levels of unemployment in South Africa. This is particularly evident

stu den t

Cooperative Education Interventions Aimed at Transferring New Technologies from a Developed to a Developing Economy: Germany/South African Collaboration in the Automotive Industry

George De Lange Department of Cooperative Education, Port Elizabeth Technikon, Private Bag X6011, Port Elizabeth, South Africa

in the shoe, clothing and textile industries situated in the Eastern Cape and Western Cape Provinces of South Africa. Currently South Africa has a poor record in terms of international competitiveness. The World Competitiveness Yearbook (2000), ranks South Africa (the only African country to be included) at 42 out of 47 countries in terms of economic literacy, education, unemployment, skilled labor, and availability of information technology skills (DoL, 2000). Some of the challenges facing South Africa as a developing country are evident on examination of the education and employment statistics for the adult population: some 38% of which are unemployed, 30% are employed in unskilled work, 24% of adults are semi-literate and under-educated, and 22% are trained as technicians, management or professionals (Wood, 1999). Globalization has lead to a demand for higher-level skills and techniques. Technological developments and dramatic changes in the accessibility of information have led to a demand for these high level skills in the manufacturing sector of the South African economy. During the period 1970 1998 high skilled jobs have increased by nearly 20% in South Africa (Yadivalli, 1999). During the same period the number of unskilled jobs decreased by similar proportion and this trend is expected to continue. Structural changes to the South African economy have also led to less reliance being placed on industries based on agriculture and mining with growth taking place in the manufacturing and financial sectors (DoL, 2000).

Correspondence to: George De Lange, email: george@petech.ac.za

13

De Lange Cooperative Education Interventions Aimed at Transferring New Technologies

Collaborative Partners Academic partners Ingolstadt University of Applied Sciences (Germany) and the Port Elizabeth Technikon (South Africa). Industrial partners Audi (Ingolstadt) and Armstrong Hydraulics (Port Elizabeth, South Africa). Phase I (1999) First exchange of undergraduate South African Mechanical, Industrial and Electrical Engineering students to Ingolstadt University of Applied Sciences. Exchange of undergraduate German students in Business Engineering to Port Elizabeth Technikon. Tuning of courses and syllabi aimed at offering combined credits acknowledged. Start of multi-media activities.

Target of student exchange program (up to the year 2000 25 students in total) Phase II (2000) Phase III (2001) Phase IV (2002) Integration of local industry (Audi and Armstrong Hydraulics) for internships and industrial projects. Common supervision of final diploma- and master thesis agreed on between the Port Elizabeth Technikon and Ingolstadt University. Founding of Verein zur Unterstutzung von Studienaufenthalten in Ausland (VUS) in Germany. A society aimed at funding South African students studying in Germany. Carrying out of common research activities with emphasis on Computer Aided Draughting and Manufacturing Engineering. Exchange of academic staff (short term visiting lectureships). Exchanging postgraduate students and visiting lecturers. Planning of combined Masters degree program in manufacturing engineering with automotive industry based research projects. Introduction of a combined credit-point-system for exchange students at the two institutions. Implementation and start of Masters programs. Awarding of a combined international degree in automotive manufacturing engineering offered by the two educational institutions. Exchange of academic staff (long term visiting lectureship).

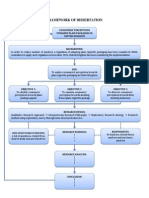

Figure 1 Model for academic/work exchange placement program

The Port Elizabeth Technikon is situated in the Eastern Cape Province, which is one of the poorest provinces in South Africa. With a population of 6.3 million in 1996, the illiteracy rate in the province is the highest in the country (57%). According to the Port Elizabeth-Uitenhage SocioEconomic Development Monitor [PEUSEDM] (1998), the total number of people who are unemployed and underemployed (i.e., people in the informal and marginal sectors) constitutes 55% of the possible labor force, with only 45% being employed in the formal sector such as factories, shops, services and state departments. In the context of this scenario, the effects of globalization are expected to further marginalize developing economies due to their lack of competitiveness. The intervention recommendation proposed by the South African Poverty and Inequality Report [SAPIR] (1999) highlighted the important role the transfer of technology can play towards

transforming South Africa into an internationally competitive country. This paper provides an outline of three cooperative education models (Figures 1 -3), which have been successful in transferring new technology to the automotive industry, which forms the backbone of the Eastern Cape economy. It provides employment to close to 380 000 people (PEUSEDM, 1998). It is estimated that 2.3 million people are dependent on the motor industry for a livelihood. Since 1998, huge foreign investments have been made into the automotive industry in the Eastern Cape, which has resulted in a number of export contracts being awarded to motorcar and component manufacturers situated in the region. These contracts were dependent on the local automotive industry meeting international quality standards, optimizing production processes with regard to their economy and consideration of the environmental impact.

Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 2002, 3(1), 13-17

14

De Lange Cooperative Education Interventions Aimed at Transferring New Technologies

Collaborative Partners (Consortium Members) Academic partners The South African partners are the Port Elizabeth Technikon, Eastern Cape Technikon, East London Technical College. The German partner is Fachhochschule Osnabrck University of Applied Sciences. Government partners German Federal Government, Lower Government of Saxony, the Provincial Government of the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa and Carl Duisberg Gessellschaft (CDG), a funding agency. Industrial partners Automotive and automotive component manufacturers in Germany and South Africa, which include amongst others Audi, Hella, Volkswagen and Daimler Chrysler. Recruitment and selection of electrical, mechanical and industrial engineering graduates and diplomandi and residing in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Selection panel consisting of representatives of the above collaborative partners. In order to qualify students must have completed at least one years industrial experience and be a graduate or diplomate from the Eastern Cape Province. Students attend 5 month German Language and culture course at Port Elizabeth Technikon, presented by lecturers appointed by the Carl Duisberg Gessellenschaft. Students leave for Germany and attend 1 month German Language Course at Saarbrcken Reception Centre, specifically aimed at orientating students to German culture and labor legislation. Students attend lectures in manufacturing engineering for a period of 4 months at the University of Osnabrck in Lower Saxony. The students are exposed to the automotive industry for 2 months in Germany. The students then return to University of Osnabrck 2 months of lectures on quality, technical and business management in industrial enterprises. The students then undertake project work and practical training using new technologies for a period of 2 months at University of Osnabrck. The students are then placed at participating automotive and automotive component manufacturers for a further two months of industrial exposure. The student return home to the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Presentation of projects and report back to South African Members of consortium. Students are assisted by the South African members of the Consortium to find permanent positions in automotive industries, situated in the Eastern Cape Province.

Figure 2 Consortium placement program

Cooperative education, with specific reference to experiential learning, has proved amongst a number of other strategies to be an effective method for the transfer of the technological expertise required to meet international manufacturing standards in the automotive industry. The experiential learning models that were chosen took cognizance of the successes and failures of previous experiences with international placements. The lack of success with previous attempts as described by Van der Schyff (2000), results from the following factors: 1. The ability of students to speak a foreign language. 2. The lack of placement opportunities available in English speaking countries. The countries that

3. 4.

5.

6.

were most approachable for exchanges were German, French, Dutch and Far East countries. South Africas geographically isolated position in relation to the developed economies. The high cost of South African students studying at foreign institutions as a result of a devalued currency. The South African Rand lost 35 percent of its value to the dollar in 2001 (Rand Plunges, 2001, Dec. 3). The lack of state and provincial funding to educational institutions for setting up the necessary support systems and infrastructure required for exchanges, f or example the services of an international office. Individual students placed with foreign employers often under-performed as a result homesickness

Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 2002, 3(1), 13-17

15

De Lange Cooperative Education Interventions Aimed at Transferring New Technologies

and a lack of understanding of for example foreign corporate culture. 7. Due to the short history of South African overseas placements, students could not follow in the footsteps of previous students. 8. The portability or acceptability and relevance of South African academic programs in developed countries made it difficult to combine programs and offer common credits. Cooperative Education Interventions In this section an outline is provided of three cooperative education models that have been used by the automotive industry (Figures 1-3). Specific attention is given to attendance patterns of experiential learning programs. Three GermanSouth African experiential learning programs have proven to be successful tools for the transfer of new technologies to the automotive industries in the Eastern Cape Province. As a result of collaboration amongst the Port Elizabeth Technikon, the Eastern Cape Technikon, German Educational Institutions, such as the Ingolstadt University of Applied Sciences, the German Government and the local automotive industry, support strategies for maintaining the experiential learning models were developed. The three models used are described by Reeve (1998) as: 1. Academic/Work Exchange Placement 2. Consortium Placement 3. Branch Location Placement. A brief outline of the structure and advantages of these models is now provided. The first model (Figure 1) falls into the Academic/Work Exchange Placement model of international placement models described by Reeve (1998). In addition to the model allowing for customization of academic programs and work-based experiential learning opportunities in the automotive industry, other advantages as explained by Reeve (1998) are that: 1. Tuition fees are wavered, which means that exchange students only pay registration fees at their home institution. 2. As a result of a supportive infrastructure and exchanges of groups of students, it reduces homesickness, assists with orientation, the understanding of organizational culture and the transition from academic institution to the workplace. 3. During their period of academic study, students are available for pre-placement activities and interviews. 4. Since the students status is established as an exchange student, work permits are easier to obtain. The students placed in industry are equipped to:

1. Assist in setting up and maintaining new technology in the automotive industry. 2. Analyze and optimize automotive manufacturing processes with regard to their economy, quality standards and eco-efficiency. 3. Develop as managers within the automotive industry. The advantages of using the Consortium Placement approach (Figure 2) were that: 1. The formalized structure, which consisted of a number of collaborative partners, was more successful in obtaining funding from foreign governments (Lower Government of Saxony) and funding organizations (Carl Duisberg Gessellschaft). 2. As a result of the team approach with a team leader, the students support each other during the program. 3. The 5 month German language and culture course in South Africa and the one month German course at the reception center in Germany allows for easier settling in of students in a foreign environment. 4. The consortiums networking and leverage ability has greater success in developing placement opportunities. 5. The employers deal with one placement officer at the University of Osnabrck. 6. Due to the strict selection criteria used for students on the program, employer participation is increased. The advantages of using the third, Branch Location Model (Figure 3) model are: 1. Students from South Africa are set technology transfer projects they have to present on their return. 2. Admission to the program, the placement, the monitoring and the reporting procedure are formalized which allows for better quality control. The students are channeled on a specific career path at Volkswagen. 3. It allows for better scheduling of trainees between the mother-plant and branch locations and students are assured of meaningful placements. 4. One clearing-house does the selection and placement of students ensuring that students meet standards set by Volkswagen South Africa and Germany. 5. Operational sections within both branches of Volkswagen can co-ordinate projects between themselves. 6. Students placed overseas already have an understanding of the organizational culture of Volkswagen and easily cope with the transition to the foreign workplace.

Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 2002, 3(1), 13-17

16

De Lange Cooperative Education Interventions Aimed at Transferring New Technologies

Collaborative Partners Academic partners Port Elizabeth Technikon and Fachhochschule Braunschweig / Wolfenbttel, Volkswagen Coaching Company (Wolfsburg). Industrial partners Volkswagen of South Africa (Uitenhage South Africa and Volkswagen Germany (Wolfsburg). South African students complete two-year theoretical component of a three-year course in Mechanical, Electrical and Industrial Engineering at the Port Elizabeth Technikon. German students complete a two-year theoretical component of four-year course in Business Engineering at Fachhochschule Braunschweig / Wolfenbttel. South African students are placed at Volkswagen South Africa for the first 6 months of the required year of experiential learning. Students with the potential of becoming permanent employees of Volkswagen are selected for a further 6 months training. Selected students are exchanged between Volkswagen South Africa and Volkswagen Germany, all expenses paid by Volkswagen. South African students are exposed to new technologies in automotive manufacturing at the motherplant in Wolfsburg and have to investigate specific projects that they have to report on when they return to South Africa. German students undertake course related project work for six months in South Africa. On return to Germany they continue with their final year of theoretical studies at Braunschweig Wolfenbttel. South African students returning to South Africa take up position in their area of specialization at Volkswagen South Africa.

Figure 3 Branch location placement program 7. Technology is transferred to the local branch without disruption to permanent staff. 8. Serves as a recruiting tool for the appointment of permanent staff. The three models have provided a working infrastructure for the exchange of students between South African and German educational institutions and participating employers. The experience gained by students participating in these exchanges has not only contributed to their technical skills but also to the acquisition of the nontechnical skills required by employers of entry-level engineering students. The students report that the experiential learning programs as applied in the three cooperative education models, contributed towards the development of their non-technical skills which include amongst others communication, teamwork, organizational effectiveness and leadership, information management and creative thinking and problem-solving skills. References Department of Labour. (2000). Towards a national skills development strategy: Skills for productive citizenship for all . Cape Town: Government Publisher. Globalization the effects on developing economies. (2001, June 7). Eastern Province Herald, p. 8. Poverty and Inequality in South Africa. )1998). Report prepared for the Office of the Executive Deputy President and the Inter-Ministerial Committee for Poverty and Inequality. Available from (http://www.undp.org.za/docs/ pubs/poverty.html) Port Elizabeth Uitenhage Socio-Economic Development Monitor (1998). Annual report. Port Elizabeth, South Africa: Vista University. Rand plunges against the dollar. (2001, Dec. 3). Eastern Province Herald, p. 11. Reeve, R. (1998). A guide for developing international cooperative education programmes. Boston, MA: World Association for Cooperative Education. United Nations Development Programme South Africa. (1998). Poverty and inequality in South Africa (URLhttp://www.undp.org.za/docs/pubs/poverty.html Van der Schyff, G. (2000, April). International linkages global training . Paper presented at the national conference of the South African Society for Cooperative Education, Durban, South Africa. Wood, G. (1999). Innovative job creation blueprint. Project report (pp. 7-19). Greville Wood Development. World Competitiveness Yearbook. (2000). Laussanne, Switzerland: International Management Development Center. Yadivalli, L. (1999). Global competitiveness: SA hangs in there. Productivity, July/August, 3.

Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 2002, 3(1), 13-17

17

Você também pode gostar

- SMU - MGMT 002 Technology and World Changes Notes - Neo Kok BengDocumento23 páginasSMU - MGMT 002 Technology and World Changes Notes - Neo Kok BengDesmond ChewAinda não há avaliações

- Land Patents by Jay Stewart Paragon Foundation PDFDocumento61 páginasLand Patents by Jay Stewart Paragon Foundation PDFBob100% (3)

- New Opportunities For African Manufacturing - African Economic OutlookDocumento9 páginasNew Opportunities For African Manufacturing - African Economic OutlookPaul MaposaAinda não há avaliações

- Form ASN 1-F - Declaration For American FederalDocumento1 páginaForm ASN 1-F - Declaration For American Federaltabiti khalfani100% (1)

- White Paper How Google Hires Their TalentDocumento21 páginasWhite Paper How Google Hires Their Talentsuyashasaha100% (1)

- HDFC Bank Application FormDocumento5 páginasHDFC Bank Application FormhimanshuAinda não há avaliações

- DevelapMe - How To Prepare For The Future of Sales Coaching To Drive PerformanceDocumento3 páginasDevelapMe - How To Prepare For The Future of Sales Coaching To Drive PerformanceMichael RiveraAinda não há avaliações

- Shouldice HospitalDocumento7 páginasShouldice HospitalGB GastecAinda não há avaliações

- Mainga Wise - Published Paper - 30-9-2020Documento34 páginasMainga Wise - Published Paper - 30-9-2020Wise MaingaAinda não há avaliações

- South Africa: Investment SectorsDocumento8 páginasSouth Africa: Investment SectorsBig Media100% (1)

- Sample Concept Paper 1Documento5 páginasSample Concept Paper 1nansambakuluthum7Ainda não há avaliações

- Fitchett TrainingDocumento27 páginasFitchett TrainingNdumiso NgubaneAinda não há avaliações

- NAtional Car ProjectDocumento27 páginasNAtional Car ProjectRazak RadityoAinda não há avaliações

- Discussion Paper Series: Entrepreneurship, Education and The Fourth Industrial Revolution in AfricaDocumento25 páginasDiscussion Paper Series: Entrepreneurship, Education and The Fourth Industrial Revolution in AfricaEdwine Jeremiah OAinda não há avaliações

- Global Value Chains Participation and PRDocumento21 páginasGlobal Value Chains Participation and PREndang EnditoAinda não há avaliações

- SMEs HEIs Automotive and South AfricaDocumento32 páginasSMEs HEIs Automotive and South Africachrissy2011Ainda não há avaliações

- MIDP TextDocumento38 páginasMIDP TextsadullahAinda não há avaliações

- Auto and Car Parts Production: Can The Philippines Catch Up With Asia?Documento38 páginasAuto and Car Parts Production: Can The Philippines Catch Up With Asia?ERIA: Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East AsiaAinda não há avaliações

- Manufacturing in AfricaDocumento6 páginasManufacturing in AfricaMohiuddin MuhammadAinda não há avaliações

- Foreign Direct Investment in Ows and The Industrialization of African CountriesDocumento15 páginasForeign Direct Investment in Ows and The Industrialization of African CountriesMuhammadShoaibAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment C ECIN01-7 DLO2 Marking GuidelinesDocumento8 páginasAssignment C ECIN01-7 DLO2 Marking GuidelinesMMASETSHABA LEHLOGONOLOAinda não há avaliações

- Park ANalysis To NepalDocumento11 páginasPark ANalysis To NepalSubham DahalAinda não há avaliações

- Aid4tradesupplychain13 Part1 eDocumento28 páginasAid4tradesupplychain13 Part1 ezubaAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 2Documento32 páginasChapter 2Nada ElDeebAinda não há avaliações

- Action Programme On Productivity ImprovementDocumento39 páginasAction Programme On Productivity ImprovementEnrique SilvaAinda não há avaliações

- Study Guide Undp by SDCTMDocumento18 páginasStudy Guide Undp by SDCTMakakakakaAinda não há avaliações

- Africa Youth EssayDocumento12 páginasAfrica Youth EssayChizzy56Ainda não há avaliações

- Internacionalización de I+D Países Europa Del EsteDocumento10 páginasInternacionalización de I+D Países Europa Del EsteJuan OkAinda não há avaliações

- Industrialisation in South AfricaDocumento11 páginasIndustrialisation in South Africaasemahlejoni1Ainda não há avaliações

- Research Paper On Globalization and TechnologyDocumento4 páginasResearch Paper On Globalization and Technologytigvxstlg100% (1)

- International Entrepreneurship and Technological Capabilities in The Middle East and North AfricaDocumento38 páginasInternational Entrepreneurship and Technological Capabilities in The Middle East and North AfricaHaddam SohaybAinda não há avaliações

- CSR Activities and Impacts of The Automotive Sector: André Martinuzzi, Robert Kudlak, Claus Faber, Adele WimanDocumento31 páginasCSR Activities and Impacts of The Automotive Sector: André Martinuzzi, Robert Kudlak, Claus Faber, Adele WimanMaha KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Contractor Development Models That Meet The Challenges of Globalisation - A Case For Developing Management Capability of Local ContractorsDocumento12 páginasContractor Development Models That Meet The Challenges of Globalisation - A Case For Developing Management Capability of Local ContractorsTatenda Maswedza100% (1)

- Eastern Europe ManufacturingDocumento14 páginasEastern Europe ManufacturingNB Thushara HarithasAinda não há avaliações

- Does Human Capital Affect Manufacturing Value-2018Documento24 páginasDoes Human Capital Affect Manufacturing Value-2018Toavina RASAMIHARILALAAinda não há avaliações

- The Economic and Social Benefits of Air Transportation To Tourism in NigeriaDocumento10 páginasThe Economic and Social Benefits of Air Transportation To Tourism in NigeriaGlobal Research and Development ServicesAinda não há avaliações

- Compare and Contrast Arrival's Prospects For Internationalisation Student's Name-Student's ID - Institute's NameDocumento16 páginasCompare and Contrast Arrival's Prospects For Internationalisation Student's Name-Student's ID - Institute's NameR AryaAinda não há avaliações

- 2019 Quality Function Deployment Knowledge Transfer To Ethiopian Industries PDFDocumento19 páginas2019 Quality Function Deployment Knowledge Transfer To Ethiopian Industries PDFkassuAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter Six: 6. Employment and Diffusion of Skills 6.1. BackgroundDocumento8 páginasChapter Six: 6. Employment and Diffusion of Skills 6.1. BackgroundParvesh GeerishAinda não há avaliações

- Car, Carriers of RegionalismDocumento399 páginasCar, Carriers of RegionalismmateoAinda não há avaliações

- Jua Kali Automobile Mechanics at Work: Challenges of Lifelong Training in The Technological Dynamic World.Documento17 páginasJua Kali Automobile Mechanics at Work: Challenges of Lifelong Training in The Technological Dynamic World.paul machocho wanyekiAinda não há avaliações

- Nidhish Balaga - Confronting Youth Unemployment in South AfricaDocumento8 páginasNidhish Balaga - Confronting Youth Unemployment in South Africanidhish101Ainda não há avaliações

- RIO10 IND Egypt EngDocumento40 páginasRIO10 IND Egypt EngSaad MotawéaAinda não há avaliações

- Auto and Car Parts Production Can The Philippines Catch Up With AsiaDocumento38 páginasAuto and Car Parts Production Can The Philippines Catch Up With Asiaxiaoqiang9527Ainda não há avaliações

- Impact of GlobalisationDocumento4 páginasImpact of GlobalisationSuman ChandaAinda não há avaliações

- Magyar SuzukiDocumento22 páginasMagyar SuzukiGáborAinda não há avaliações

- Ethiopia S Investment Prospects A SectorDocumento44 páginasEthiopia S Investment Prospects A SectorMehari MacAinda não há avaliações

- SWOT AnalysisDocumento13 páginasSWOT AnalysisOzair ShaukatAinda não há avaliações

- CitiesDocumento12 páginasCitiesnkemghaguivisAinda não há avaliações

- Conditions For The High Tech SectorDocumento14 páginasConditions For The High Tech Sectormustafaemir.bilgenAinda não há avaliações

- Science Technology Society 1996 Hill 51 71Documento22 páginasScience Technology Society 1996 Hill 51 71Leo AlvarezAinda não há avaliações

- IPP 2014 Appendix 1 Sectoral AnalysesDocumento63 páginasIPP 2014 Appendix 1 Sectoral AnalysesRose Ann AguilarAinda não há avaliações

- Globalisation Essay FinalDocumento8 páginasGlobalisation Essay FinalSahara Makeup AcademyAinda não há avaliações

- 115 231 1 SM PDFDocumento11 páginas115 231 1 SM PDFBinju SBAinda não há avaliações

- Economic DevelopmentDocumento18 páginasEconomic DevelopmentLBS17Ainda não há avaliações

- Marketing Construction Business ProblemsDocumento11 páginasMarketing Construction Business ProblemsAnıl ÖztürkAinda não há avaliações

- Automotive in Turkish Use SCSDocumento12 páginasAutomotive in Turkish Use SCSkrisAinda não há avaliações

- ZIMSEC O LEVEL GEOGRAPHY FORM 4 - IndustryDocumento30 páginasZIMSEC O LEVEL GEOGRAPHY FORM 4 - Industrycharles hofisiAinda não há avaliações

- SDG-9: Industry, Infrastructure, InnovationDocumento13 páginasSDG-9: Industry, Infrastructure, InnovationTahmid Hossain RafidAinda não há avaliações

- Japanese Automobile IndustryDocumento10 páginasJapanese Automobile IndustryEdi RaduAinda não há avaliações

- Misale - Commercial Vehicle Drivers School ProdocDocumento52 páginasMisale - Commercial Vehicle Drivers School ProdocPankaj MishraAinda não há avaliações

- Final Global EconDocumento14 páginasFinal Global EconMannat DuttAinda não há avaliações

- PEST ANALYSIS Automobile IndustryDocumento2 páginasPEST ANALYSIS Automobile IndustrySuraj Sharma67% (6)

- PestDocumento2 páginasPestHarish BansalAinda não há avaliações

- The future of the European space sector: How to leverage Europe's technological leadership and boost investments for space ventures - Executive SummaryNo EverandThe future of the European space sector: How to leverage Europe's technological leadership and boost investments for space ventures - Executive SummaryAinda não há avaliações

- Data Colected For JournalDocumento4 páginasData Colected For JournalVivi Sabrina BaswedanAinda não há avaliações

- 5 Porter Forces AnalysisDocumento9 páginas5 Porter Forces AnalysisVivi Sabrina Baswedan100% (2)

- Sharp Corporation: Company ProfileDocumento9 páginasSharp Corporation: Company ProfileVivi Sabrina BaswedanAinda não há avaliações

- The Knowledge Integration Strategy Analysis After Geely Acquisition of VolvoDocumento4 páginasThe Knowledge Integration Strategy Analysis After Geely Acquisition of VolvoVivi Sabrina BaswedanAinda não há avaliações

- 700words: Q.2b: Functional Strategies Including Product, Marketing & Operations DecisionsDocumento2 páginas700words: Q.2b: Functional Strategies Including Product, Marketing & Operations DecisionsVivi Sabrina BaswedanAinda não há avaliações

- 5 Porter Forces AnalysisDocumento9 páginas5 Porter Forces AnalysisVivi Sabrina Baswedan100% (2)

- ZukisDocumento1 páginaZukisVivi Sabrina BaswedanAinda não há avaliações

- Bulletpoints For Marketing and StrategyDocumento1 páginaBulletpoints For Marketing and StrategyVivi Sabrina BaswedanAinda não há avaliações

- JBJXBCJZGJCKGJKV P ('t':3) Var B Location Settimeout (Function (If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') (B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Documento1 páginaJBJXBCJZGJCKGJKV P ('t':3) Var B Location Settimeout (Function (If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') (B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Vivi Sabrina BaswedanAinda não há avaliações

- KDRT Finishhhhhh ViviDocumento37 páginasKDRT Finishhhhhh ViviVivi Sabrina BaswedanAinda não há avaliações

- Title Del Monte v. Saldivar G.R. No. 158620Documento3 páginasTitle Del Monte v. Saldivar G.R. No. 158620Rochelle Joy SolisAinda não há avaliações

- #656 DAC-Polaris HOT PresentationDocumento15 páginas#656 DAC-Polaris HOT PresentationDerrick HensonAinda não há avaliações

- Cover Letter ReDocumento6 páginasCover Letter Regvoimsvcf100% (2)

- Job Descriptions: Rakesh Patidar Vice-Principal, JCNDocumento26 páginasJob Descriptions: Rakesh Patidar Vice-Principal, JCNRakersh PatidarAinda não há avaliações

- ENGLRES Final PaperDocumento16 páginasENGLRES Final PaperMarvin Joshua ChanAinda não há avaliações

- Staar 02 Industrialization and The Gilded AgeDocumento44 páginasStaar 02 Industrialization and The Gilded AgeALEN AUGUSTINEAinda não há avaliações

- The Transformation of The Dutch Urban Block in Relation To The Public Realm Model, Rule and IdealDocumento16 páginasThe Transformation of The Dutch Urban Block in Relation To The Public Realm Model, Rule and IdealnajothanosAinda não há avaliações

- Form HDocumento6 páginasForm HVinay RankaAinda não há avaliações

- Motivation Chapter 6Documento26 páginasMotivation Chapter 6Anonymous HK3LyOqR2gAinda não há avaliações

- Post-Soviet Georgia in The Process of Transformation-Modernization Challenges in Public ServiceDocumento26 páginasPost-Soviet Georgia in The Process of Transformation-Modernization Challenges in Public ServiceCharkvianiAinda não há avaliações

- ADVENTURE II The Red-Headed LeagueDocumento18 páginasADVENTURE II The Red-Headed LeagueCsilla KecskésAinda não há avaliações

- Maliwat v. CA, 256 SCRA 718Documento3 páginasMaliwat v. CA, 256 SCRA 718Lorille LeonesAinda não há avaliações

- Consti Cases Article 3 Section 1Documento96 páginasConsti Cases Article 3 Section 1donyacarlottaAinda não há avaliações

- Burnout Syndrome in Hospital NursesDocumento10 páginasBurnout Syndrome in Hospital NurseskrizaricaAinda não há avaliações

- Speech Pathologists' Professional Identity in Response To Working With AssistantsDocumento1 páginaSpeech Pathologists' Professional Identity in Response To Working With AssistantsKaren DanielaAinda não há avaliações

- Toolbox Training HorseplayDocumento2 páginasToolbox Training HorseplayMugil ViswaAinda não há avaliações

- Agreement BCSS XYZ May2008Documento2 páginasAgreement BCSS XYZ May2008Rehan SiddiquiAinda não há avaliações

- Life Orientation ANNEXURE CDocumento5 páginasLife Orientation ANNEXURE ConamoruaphekoAinda não há avaliações

- Strauss e Thomas - 1998 - Health, Nutrition, and Economic DevelopmentDocumento53 páginasStrauss e Thomas - 1998 - Health, Nutrition, and Economic Developmentdayane.ufpr9872Ainda não há avaliações

- K-Medical Staffing: A Business PlanDocumento57 páginasK-Medical Staffing: A Business PlanPrabha GuptaAinda não há avaliações

- MarketingDocumento90 páginasMarketingPalak GuptaAinda não há avaliações

- The Important Roles of A ManagerDocumento2 páginasThe Important Roles of A ManagerBae MaxAinda não há avaliações

- HRM Project FinalDocumento14 páginasHRM Project Finalনাজমুস সাদাবAinda não há avaliações

- TBEM Application 2012 MytmlDocumento74 páginasTBEM Application 2012 Mytmlgagandeep89Ainda não há avaliações