Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

The L2 Reader: Learning Outcome

Enviado por

Esther Ponmalar CharlesDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

The L2 Reader: Learning Outcome

Enviado por

Esther Ponmalar CharlesDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

CHAPTER

THE L2 READER

LEARNING OUTCOME Upon completion of this chapter, you should be able to: 1. 2. 3. 4. discuss the six factors that influence reading in L2 define Clarkes (1979) linguistic hypothesis; explain the role of metacognitive awareness in reading; and describe the differences between L1 and L2 readers in terms of their metacognitive awareness.

ERC411 READING IN SECOND LANGUAGE CONTEXTS

THE L2 READER

CHAPTER 5

INTRODUCTION

You have been introduced to reading and the different characteristics of reading in the previous chapters. This was followed by the different physical processes and mental processes involved in reading. Also, we have discussed about the different models of readings. These models provide different insights on how a reader reads which is important before a teacher can decide how best to teach them. However, as stated before, these models are based on L1 (first language) readers. Even though our target students are ESL, we still need to understand how an L1 reader reads because most of our knowledge about the L2 (second language) reader is based on what we know about the L1. We have started the discussion on L2 reading in Chapter 4, which discusses how reading comprehension is affected by different types of prior knowledge. If what one knows about the world i.e. prior knowledge affect the first language reader, what more the second language reader. To understand the challenges faced by the second language reader and the cognitive processes of an L2 reader better, this chapter addresses specifically on issues related to reading in the L2.

5.0

FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE READING IN L2

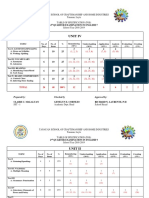

What can you conclude about reading in L1 and L2 from your experience? Actually, there are many similarities between reading in the L1 and reading in the L2. You know that the physical and mental processes of an L1 reader have been discussed before. There are, however, certain elements that differentiate reading in the L2 from L1 reading. For instance, some readers may already be literate in the L1 before beginning to read in the L2, some may start reading in the L2 with very little vocabulary knowledge of the target language (L1 children usually begin reading with a knowledge of several thousand words), and some may experience great differences in the writing systems between the two languages. To learn more of reading in L2, read on for this chapter to know the factors that influence reading in the L2. The factors that determine reading proficiency in L2 are shown in Figure 5.1.

CHAPTER 5

THE L2 READER

..........................

Figure 5.1: Factors that determine reading proficiency in L2 5.1.1 FACTOR 1: L2 LANGUAGE PROFICIENCY

One of the main factors that influence L2 reading is L2 language proficiency. Low reading proficiency can be due to low L2 proficiency. This is referred to as the Linguistic Threshold hypothesis. The linguistic threshold hypothesis is based on Clarkes (1979) short circuit hypothesis which asserts that low proficiency in the second language may result in a short circuit of efficient reading strategies where such efficient reading strategies are not transferred into the L2. Students must have a certain level of language proficiency before reading can be done effectively. This is referred to as the threshold level. The level of the threshold depends on the complexity of the text.

THE L2 READER

CHAPTER 5

Figure 5.2: The linguistic threshold hypothesis (a) Studies in L2 Language Proficiency and Reading Level Clarke (1979) hypothesis was based on the findings of two studies conducted, which compared students reading ability in L1 and L2. The first study involved 21 advanced and weak Spanish L1 adult readers studying at the English Language Institute, University of Michigan. These Spanish students had equivalent L2 reading proficiency. The instruments used in the first study were cloze tests written in both Spanish and English. Results indicate that in the L1, good readers relied on semantic rather than syntactic cues in contrast to poor readers who relied on syntactic rather than semantic cues. When reading in the L2, however, the use of semantic cues by the good readers was greatly reduced where they were not able to fully utilize their effective reading strategies. When reading L2 texts, the good readers tended to employ similar strategies to those used by the poor L1 readers.

Figure 5.3: Readers use of semantic cues in reading in L1 and L2 (Clarkes study)

CHAPTER 5

THE L2 READER

..........................

The second study compared the oral performance of a good and poor L1 reader using miscue analysis. The subjects were required to read two texts (one English and one Spanish). It was found that the good reader produced fewer miscues than the poor reader in both L1 and L2 reading and that the miscues were of higher quality. When reading in L1, the good reader tended to focus more on the meaning of the text and semantic cues rather than its syntactic acceptability. The poor reader, on the other hand, produced less semantically acceptable miscues but there was no difference between the two on the production of syntactically acceptable miscues. When reading in L2, however, the good reader was less able to use the semantic cues and also produced a higher level of syntactically acceptable miscues compared to the poor reader. The findings of Clarke (1979) seem to be supported by two studies conducted by Cziko (1980) who analyzed the relationship between language competence and the use of graphic and contextual information in reading. His subjects were 22 intermediate and 25 advanced French as a second language and 29 native French-speaking students. Miscue analysis was done on the oral reading of two French narrative texts which were of different levels of difficulty. Results seem to indicate that reading ability correlates with language proficiency. The more competent language learners, similar to the native French speakers, appeared to employ an interactive strategy where both the graphic and contextual information were utilized.

Figure 5.4: What should teachers do? In contrast, the intermediate learners tended to rely more on graphic information and employed fewer contextual clues. This seems to indicate that the advanced and native speakers were using more top-down strategies while the intermediate students were more bottom-up dominant. Horiba (1996) carried out a study which compared the reading performance of three groups of readers, L1 English readers (N=16), L2 Japanese readers from the intermediate and advanced Japanese course level (N=40) and L1 Japanese readers (N=20). The materials employed were two sets of Japanese short stories which had the same length and linguistic difficulty. Each set of stories was rewritten to produce a low coherence version where the number of causal links between the events in the text was reduced. All the texts were translated into English. Therefore, for each language there were four texts, two of high coherence (which employed the original structures) and two of low coherence (in which causal links were reduced).

THE L2 READER

CHAPTER 5

The subjects were then randomly assigned to read each text using the think aloud method or reading it silently and were then asked to write everything that they could recall. The same procedure was then repeated. The results of the think aloud data for the first reading indicate that Japanese L2 intermediate students employed strategies which focused on lower level processes in contrast to Japanese L2 advanced readers or both groups of L1 readers who employed strategies that focused on higher level processing. Both groups of L1 readers hardly ever employed lower level processes and their strategies were mostly on elaborative inferences and general knowledge associations. The advanced Japanese L2 students, like the L1 readers, utilized higher level processes such as elaborative and predictive inferences instead. During the second reading, L2 subjects produced more elaboration and were seen trying to link information from the sentences in the text. The L1 readers, in contrast, focused more on processing the text as a whole. When their performances on the high and low coherence texts were compared, L1 readers were also found to produce more elaborative inferences on texts with low coherence and were reverting to earlier parts of the text and to their background knowledge to make inferences. There was no difference in the performance of the L2 readers between the low and high coherence texts in the first reading. In the second reading, however, advanced L2 readers seemed to be more sensitive to higher levels of discourse structure. This seems to provide evidence that L2 subjects were bottom-up dominant and thus were satisfied as long as the texts were connected and made sense at the local level. As Horiba (1996:457) explains, L2 readers may have employed lower standards of coherence, compared with L1 readers who noticed that the message is distorted and therefore, inferences need to be drawn so that information in the text can be processed as a coherent whole. L2 language competence is an important factor in L2 reading especially at the beginning level. L2 learners seemed to employ lower level processing but with higher proficiency, the advanced L2 learners were found to be using higher level processes just like the L1 readers. This seems to support Clarkes short circuit hypothesis where lack of L2 proficiency causes readers to rely on graphic information rather than higher level processes. In other words, proficient L2 learners were also more competent readers in contrast to less proficient language learners. There seems to be a direct relationship between language proficiency and reading ability. (b) Implications of Clarkes Studies The studies discussed in previous sections seem to provide evidence that proficient L1 readers tend to switch to less effective reading strategies when reading L2 texts probably because limited control over the language short circuits the good readers system, causing them to revert to poor reader strategies when confronted with a difficult or confusing task in the second language (Clarke 1979:138). There seems to be a language competence ceiling that readers need to achieve before efficient reading can be achieved. Incompetence in the target language can lead to reading difficulty.

5

CHAPTER 5

THE L2 READER

..........................

Therefore, as teachers, we need to be aware of our students language proficiency before choosing texts of any appropriate complexity level. Teachers may want to choose texts, which are challenging to students so that they want to continue reading the texts but not too challenging that they end up feeling confused and frustrated. Teachers may also want to choose texts which are at a level lower than the students current linguistic level if they are to read on their own, at their own pace, rate and time. A discussion on assessing the readability of texts will be done in Chapter 7 of this module.

Can L1 reading skills influence L2 reading skills? Discuss.

5.1.2

FACTOR 2: L1 READING SKILLS

Other than readers language competency in the L2, readers reading proficiency in the L1 is also a significant factor in determining reading proficiency in the L2. Generally, proficient L1 readers also make proficient L2 readers and vice versa. L2 language competency alone is not enough. There are students who are well verse in the target language, but prove to be incompetent readers. One of the main reasons is because these students do not read proficiently in their L1. This is referred to as the linguistic interdependence hypothesis.

Figure 5.5: Linguistic interdependence hypothesis

THE L2 READER

CHAPTER 5

According to the linguistic interdependence hypothesis, or what is also referred to as the common underlying proficiency hypothesis, reading performance in the second language is dependent on reading ability in the first language. (a) Studies on Linguistic Interdependence Hypothesis The linguistic interdependence hypothesis was first proposed by Cummins (1979,1991) who carried out a survey which compared and re-interpreted data from various studies on bilingualism. According to Cummins (1979,1991), literacy skills can transfer, provided that there is adequate exposure to the target language and sufficient motivation to learn it. There is a common underlying proficiency that facilitates literacy development and assists language skills to transfer. Therefore, the development of literacy-related skills in L2 is partially a function of the type of competence the child has developed in L1. Cummins (1979:233) states, The initial high level of L1 development makes possible the development of similar levels of competence in L2. In addition, Coady (1967) asserted that some students transfer their poor L1 reading habits to L2 and thus, L2 classes need to provide instruction on effective reading skills which should have been taught in L1. Among many factors, readers need to learn to become flexible readers who are able to adjust their reading strategies and rate according to the text and their purpose of reading and monitor their comprehension or lack of it. L2 reading is not just a language problem; it is also a reading problem. This notion of reading problem is supported by Goodman (1988) who stated that, based on findings from miscue analysis, reading is a universal process where strategies employed are similar despite language background. Efficient reading strategies are similar across languages. So, to be able to read well in L2 also depends on how well the reader reads in L1. Wagner, Spratt and Ezzaki (1989) carried out a longitudinal study on the language acquisition of 166 primary school children from 5 schools beginning from when they were in grade 1 until grade 5. The subjects were children from 2 different linguistic communities (Moroccan Arabic and Berber) who lived in the same community in a Moroccan rural town. They studied Arabic as their first literacy language in school and French as their second language. The French language, however, was not introduced until year 3. Data for the study was collected through the use of different instruments: standard Arabic reading tests for grades 1 to 5, a letter knowledge test which was administered in year 1, a word decoding test administered in years 1 and 3, a word picture matching test, a sentence maze test, a paragraph comprehension test, French reading tests and cognitive ability assessment. To examine the factors influencing the second language acquisition of the students, hierarchical regression analysis was conducted at the end of year three and year five. For both years, there did not seem to be a difference in the performance of the Arabic and Berber speaking students. Results for year five French reading ability indicate that L1 reading ability for each year of study seemed to significantly contribute to a large portion of the variance in the French reading score. It was also found that year 1 Arabic decoding skills were the most important predictor for the beginning French reading ability.

CHAPTER 5

THE L2 READER

..........................

This indicates that there seemed to be a transfer of reading skills from first language to second. Although Arabic and French do not share the same orthographic system or reading direction, there seems to be a transfer of decoding skills over the two languages, supporting the notion of the transfer of alphabetic decoding across highly contrasting orthographies (Wagner et.al, 1989:43). This seems to provide evidence for the interdependence hypothesis that the ability to read is only learned once. When reading in another language, readers transfer their reading skills from L1 to L2. Hudson (1988), found that language proficiency can be overridden by inducing schema in a study which compares three types of schema reconciliation methods, such as, prereading, vocabulary input and read-test. The subjects were 93 international ESL preuniversity students in America who were beginning, intermediate and advanced readers as determined by their class reading level. Data was collected through the use of nine reading comprehension passages which employed each of the reconciliation methods. Results indicate that pre-reading activities produced significantly higher means for the beginning and intermediate students compared to vocabulary and read-test. None of the treatments produced significantly different results for the advanced readers. This means that the linguistic ceiling can be overridden by inducing content schema, which provides evidence that reading is more of a reading than a language problem. (b) Is it Language or Is it a Reading Problem?

As a teacher, you need to make informed decisions as to how reading should be taught to your students. Explain, what should be your course of action in the following situations: a) Your students are reading poorly in the second language because their reading skills in the native language are just as poor. b) Your students are reading poorly in English because their English proficiency is poor. c) Your students are competent L1 readers. However, when they read texts written in the L2, they seem to be using the skills of poor readers. d) Your students are not familiar with the writing system of the L2? Therefore, they face a lot of challenges trying to make sense of the new language.

It is very important for teachers to identify the challenges faced by their learners when reading in as second language. Is reading in the L2 the same as reading in the L1? Is there a transfer of reading ability from L1 to L2? Are good L1 readers also good L2 readers? The answers to these questions are pertinent so that accurate pedagogical considerations can be made. Such

THE L2 READER

CHAPTER 5

implications can be any or a combination of any of the following as suggested by Alderson (1984: 5-6): If poor first-language reading is the cause, we must improve first language reading. If poor foreign language knowledge is the cause, we need to improve FL competence. If first language ability is short circuited by low FL competence, we need to improve FL competence first, and then improve the reading strategies of poor L1 readers. If processing is different for different languages, then we need to teach reading of the foreign language, regardless of L1 ability. If transfer of reading ability takes place across the native/non-native language divide, then we can teach reading in either the first or foreign language to those readers who are poor in their L1 reading. Readers who are poor in their L1 are either logical impossibilities or merely in need of familiarization with the foreign language code. FACTOR 3: METACOGNITIVE STRATEGY AWARENESS

5.1.3

What is metacognitive? Metacognitive knowledge refers to knowledge about knowledge (Alexander, Schallert and Hare 1991:328). Metacognitive knowledge can be acquired formally and informally, deliberately or incidentally and learners can become conscious of and articulate what they know (Wenden 1998:516). Flavell (1987) classified metacognitive knowledge into three categories: 1. Self-knowledge Self knowledge refers to the learners conceptualization of the factors that facilitates or inhibits learning in general. It also refers to the subjects perception of themselves as learners, what they do best and worst (e.g. I am better at true/false questions than cloze tests) and their ability to achieve certain learning goals. Self-knowledge also includes knowledge about their effectiveness as learners compared to that of others (e.g. I can read this text better than him). 2. Task knowledge Task knowledge involves knowledge of the purpose of the task (e.g. to develop reading skills), and knowledge about the tasks demands such as how to learn and how to approach a task. It also involves recognizing those different types of task demand different learning. 3. Strategic knowledge Strategic knowledge refers to learners knowledge about strategies what they are, when and how to use them and why they are useful.

CHAPTER 5

THE L2 READER

..........................

Figure 5.6: Classification of metacognitive knowledge According to Monteiro (1992:35) It is only recently that some studies have begun to pay attention to metacognition, that is, the relationship between strategy awareness or perception of strategies, strategy use, and reading comprehension. Many studies seem to indicate that metacognitive awareness is also a variable that it is related to reading ability. Two studies of metacogniive awareness and reading are reviewed in the following section. (a) Studies of Metacognitive Awareness and Reading Comprehension Carrell (1989) carried out a study to investigate the relationship between metacognitive awareness and reading comprehension in L1 and L2. The study involved students from two language backgrounds Spanish L1 and English L1 university students. The Spanish L1 students were learning ESL while the English students were learning Spanish as a foreign language. To measure the students reading ability in L1 and L2, they answered two sets of multiple choice reading comprehension tests for each language. Then they completed a metacognitive questionnaire about reading in both languages. The metacognitive questionnaire comprised four sections: selfconfidence, repair strategies, effective reading strategies, and finally, reading difficulties. Results seemed to indicate that for both groups of readers, when readings in L1, top-down strategies were not significantly related to reading ability. Local strategies, however, seemed to be negatively correlated to reading ability. This meant that the less local strategies were perceived as effective reading strategies, the more proficient their reading ability. For L2 reading, some global strategies were found to be positively correlated with reading proficiency. Metacognitive awareness seemed to be related to reading ability in the target language. For the less proficient Spanish as a foreign language reader, there seemed to be a more bottom-up orientation to what were perceived as effective and difficulty causing reading strategies. In contrast, for the more proficient ESL readers, a more top-down perception of effective and problematic reading strategies were reported utilized by the readers.

10

THE L2 READER

CHAPTER 5

Barnett (1988) investigated the effects of metacognitive awareness and strategy use on reading comprehension. The subjects were 278 university students enrolled for a French course. They were required to complete a prior knowledge questionnaire and read an unfamiliar passage. They then wrote a recall on the passage. Then, they read another unfamiliar passage and complete a test, which assessed their ability in using contextual information. The test required the students to select the most appropriate phrase, sentence or paragraph to continue the passage. The students then completed a questionnaire on their perceived strategy use. Findings seemed to indicate that there was a linear relationship between strategy use and reading comprehension. Students who used better strategies at reading through context performed better than students who did not use effective strategies. Metacognitive awareness also seemed to be correlated with reading ability. Students who claimed to use effective reading strategies seemed to perform better on the reading comprehension tests compared to readers who did not. In other words, the relationships between perceived strategy use, actual strategy use and reading comprehension were positive. Students who claimed they used effective strategies seemed to use better strategies at understanding sentences in context and they also seemed to have higher reading ability.

Figure 5.7: Results of Metacognitive Awareness in Reading (b) Implications of Metacognitive Awareness on Reading Based on studies of metacognitive awareness, teachers should be sensitive to readers metacognitive awareness of themselves. Readers should know what and which strategies to use; when, how and why do they use the strategies in their reading. Another element that teachers need to keep in mind is that there is a big difference between adults metacognitive knowledge compared to younger learners. Learners understanding and

11

CHAPTER 5

THE L2 READER

..........................

ability to discuss their learning and thinking processes, that is, about self knowledge, task knowledge and strategic knowledgegenerally develop as they grow older, or as their level of learning increases.

*Concord: In grammar, concord is the relationship between words which determines whether they should be e.g. singular or plural (agreement). Figure 5.8: Complex linguistic terminology should not be used to younger learners Therefore, teachers may not want to provide lengthy grammatical explanations and complex linguistic terminology to younger learners. Adult ESL learners, with a more established schema and perhaps, a better knowledge of their L1 linguistic or grammatical structures, might be better at comprehending linguistic rules.

Think of your students. Based on metacognitive awareness, discuss what should the students know to become better readers?

5.1.4

FACTOR 4: DEGREE OF DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THE L1 AND L2 READER

The degree of difference between L1 and L2 is a major influencing factor in reading in L2. L1 and L2 readers may use completely different writing systems and cultural orientation towards reading. Some readers use different reading strategy, discourse and have different comprehension gap. These differences will be discussed in the following section. (a) Writing System The difference in the writing systems of the L1 and L2 is an important influencing factor. Such difference may involve learning a totally new set of system such as orthographic.

12

THE L2 READER

CHAPTER 5

Figure 5.9: Five aspects of differences involved between L1 and L2 reading

Can you still remember the eye movements involved in reading? What are they?

An L2 learner who learns Tamil, Jawi or Mandarin (refer to Figure 5.10) as their first languages may need to learn a new set of writing system when learning Bahasa Melayu or the English language and vice versa. They may also need to get used to reading with another set of eye movements. For instance, Jawi is not just a different set of writing code; it is read from right to left instead of left to right as in Bahasa Melayu and English.

Figure 5.10: Reading in different writing systems (Jawi and Mandarin)

13

CHAPTER 5

THE L2 READER

..........................

Readers who need to switch from one writing system to another will require more time to learn to read in the target language compared to readers who share a similar writing system. Readers who are used to logographic will need to learn the alphabets. Likewise, readers who are used to a limited number of alphabets may require even more time to learn the abundant characters or logographs. For the Malaysian situation, many of us are fortunate because Bahasa Melayu is the L1 for most of it and employs the Roman alphabets, just like the English language. Moreover, both Bahasa Melayu and English language are read from left to right and both languages are learned when readers are still young. Therefore, readers may not require as much time compared to others who may not share the same writing system or who may learn ESL as adults. (b) Different Cultural Conceptions of Reading Different cultures may have different conceptions about reading. Some may come from a culture, which accepts everything that is written as words of wisdom or the TRUTH. These are those who learn to read sacred scriptures such as the Quran or the Bible. Such reading may involve reading for aesthetic purposes or for the purpose of appreciation. Other cultures may encourage critical reading where readers are required to question, interpret and infer information. This usually involved reading for academic purposes. Children who learn to read by listening to stories read to them or who come from storytelling cultures may read using more imaginative and use the text as the basis for creative or playful expression. (Aebersold and Field 1997:29)

In your opinion, what kind of cultural conceptions do Malaysian children have toward reading?

(c) L1 Reading Strategies Different ESL students have different reading skills and strategies. This was supported by a study done by Pritchard (1990) involving 30 US and 30 Palauan of 11th graders, reading familiar and unfamiliar passages, regarding funeral ceremonies in their own languages. It was found that the Americans employed more top-down strategies when reading both texts. On the other hand, the Palauans were more bottom-up where some of them relied heavily on decoding skills. Generally, the American readers tended to be more global than the Palauans when trying to make sense of what seemed to be incomprehensible. This suggests that different ESL learners not only have different cultural orientation towards reading, they also employ different reading strategies.

14

THE L2 READER

CHAPTER 5

Even those who come from the same country or culture may also share different reading strategies due to their different experience. In the Malaysian context for example, there are several types of secondary schools. Among them are religious schools, technical schools, residential schools and non-residential secondary schools. In many of these schools, learners come from different fields. For instance, at Form Four, there are students who are taking the science stream, social science or the arts stream. These learners are exposed to different types of texts and will read for different purposes in their L1. For instance, those from the science stream will be more exposed to mathematics and scientific texts and have very little experience with literary texts. These students are probably very good at scanning for specific information, classifying and categorising.

Figure 5.11: Science stream students may be good in scanning and analysing texts On the other hand, those who are in the arts stream may be more experienced with literary works, which involved figurative language and creative expressions. They are probably good at predicting, interpreting and inferring. Teachers need to be aware of the different types of reading skills and strategies their students have developed in their L1 when making pedagogical decisions about reading the L2. An insight on the students strengths and weaknesses in reading can help teachers make more informed decisions on the texts to be used, the strategies to focus on, to transfer from the L1, or to develop in the L2. (d) Discourse Structures in the L1 Formal schemata represent knowledge of the discourse structures that readers develop through exposure to different discourse organisations, language conventions and literary devices. What is discourse structure? Discourse structure refers to the general rhetorical goal of a text.

15

CHAPTER 5

THE L2 READER

..........................

Examples of discourse structures are: a. b. c. d. narrative descriptive argumentative and procedural problem solution

Formal schemata, as discussed in Chapter 4 under schema theory, depend on a readers prior knowledge.

Figure 5.12: Discourse structure and formal schemata For instance, a scientist will be very familiar with the format of a research report while a childs most established textual schema might be of a folk tale. Discourse structures may not be universal. For instance, the discourse structure of a Japanese folktale is very different from that of a western one. Formal schemata serve as a form of outline, which facilitates readers to organise and comprehend the text in several ways. The schemata of a certain discourse structure may direct attention to certain aspects of the incoming material. This helps readers to organise information into different levels of importance such as main ideas and details. The schema also helps in constructing hypotheses on what is coming next. For instance, the setting of a certain narrative provides a lot of information for predicting later events. Textual schemata also help in making inferences and making connections between new sentences and sentences already read. According to Anderson, Pichert and Shirey (1983:272):The readers schema guides allocation of attention to the significant aspects of text, furnishes the ideational scaffolding for assimilating information, and/or enables inferential reconstruction where there are gaps in memory.

16

THE L2 READER

CHAPTER 5

The impact of formal schemata on reading comprehension has been reported in previous studies. One such study was carried out by Carrell (1984). She investigated the effects of four types of expository texts on the reading comprehension of ESL readers. The subjects were 80 ESL University students from different language backgroundsSpanish, Arabic, Asian (Korean and Chinese) and others (they were predominantly Malaysians). The texts employed were expository texts that were written in four rhetorical structures causation, problem/solution, comparison and collection of description. Each rhetorical structure had similar length and identical content. Each student was randomly assigned one text to read. They were then required to write everything they could recall about the passage. Two days later, they were again asked to write everything they could remember about the passage. They then completed a probe recall task, which required them to fill in the blanks using information common to all the four passages. The results showed that significantly more idea units were recalled immediately after reading the passage compared to two days after it. This result was consistent for all the four passages. Significant difference was also found in the number of idea units that were immediately recalled among the different rhetorical structures. Significantly, more idea units were recalled in the comparison, causation and problem/ solution structure compared to the collection of description structure. The probed recall task was also better for all these three structures compared to the collection of description although this result was not statistically significant. This suggests that the descriptive structure tended to be less facilitative to comprehension compared to argumentative discourse structures. It was also found that there was a significant relationship between recognising and using the rhetorical structures of the text and information remembered. ESL students who used the rhetorical structures of the original texts in their written recall were able to remember more idea units than those who did not. Rhetorical structure awareness and the ability to use discourse structures seemed to correlate positively with reading comprehension. This suggests that readers who have prior knowledge of the rhetorical structures employed will be able to read more successfully than those who did not. An interesting finding of this study was that performance on the recall tasks was significantly different among the four language groups. For all the language groups, except for the Asian students, more idea units were recalled in the immediate compared to the delayed task. For the Asian students, both tasks produced similar results. For all the language groups, except for the Arabic, there was a significant difference in performance on the collection of description text compared to the rest of the structures. The Spanish students had similar means for idea units recalled in the comparison, problem/solution and causation structures, but a much lower mean for the collection of description structure. The Asian students who comprise of Chinese and Korean, performed very well on the problem/solution and causation structures compared to the comparison and collection of description structures. Students from the others group performed best on the causation structure. This was followed by the comparison and problem/solution structures and finally, the

17

CHAPTER 5

THE L2 READER

..........................

collection of description structure. The Arabic students performed best on the comparison structure. This was followed by the problem/solution and the collection of description. Unlike the other language groups, they performed least well on the causation structure. L2 readers language background seemed to be a variable which influenced the comprehension of different types of rhetorical structures. This suggests that formal schemata are a significant factor in influencing reading.

List some of the discourse structures that you need to employ in your class.

Different ESL readers have different sets of formal schemata. Therefore, it is important for teachers to understand the structures that are more common to the students and employ this in their teaching. Teachers also need to develop an understanding of their students expectations when reading texts of certain structures. Most importantly, teachers need to be well informed of the types of discourse structures that the students need to learn in the L2. In the Malaysian context, other than the discourse structures mentioned above, students may need to learn to fill in forms, job applications and checkbooks. (e) Comprehension Gap Language is very much a part of culture. From our discussion on schema theory, we know that prior knowledge plays a big role in reading comprehension. Steffensen, Joag-Dev and Anderson (1979) carried out a study to find out if differences in background knowledge about the content of the text influence reading comprehension. The subjects were Indians and Americans and the materials used were two textsone on an Indian wedding and the other on an American wedding. Both texts were written in English. The two groups of subjects were Indian students for whom English was an L2 and the American students, for whom English was the L1, read and recalled the letters. The results indicated that the readers comprehended texts about their own cultures more accurately than the other. Johnsons (1982) study provides evidence that advanced ESL university students found information about familiar aspects of Halloween celebration easier to comprehend and elaborate in contrast to the unfamiliar aspects, that is, information about how Halloween was celebrated a 100 years ago. These students not only managed to recall more explicit and implicit information on the familiar aspects of the passage, they also elaborated their own knowledge into the subject. This suggests that knowledge of the content is very important in reading.

18

THE L2 READER

CHAPTER 5

Look at this cartoon:

Source: wwwbucklemyshoes.blogspot.com wwwbucklemyshoes.blogspot.com wwwbucklemyshoes.blogspot.com http://www.google.com.my/imglanding?q=kampung+boy+raya Balik Kampung is a Malaysian culture. When persons from different background, for example, different culture and languageread this cartoon can they translate Balik Kampung to their language? If the person is able to translate this literally, will the translation have the same cultural value? To learn to read also requires learning the target culture. For instance, the sentence I am going to a kenduri Unless, one is well versed in the Malaysian culture, one may think that a gathering such as a kenduri is like a party or other social gathering without a religious connotation to it. Another example is I went late night shopping at Harrods last winter and came home at 8.30p.m. For many Malaysians, 8.30pm is early, but for people in other cultures, it gets dark much earlier during winter and by the time it is 8.30p.m, it is really late at night. Moreover, in many places in the UK, many shops are closed at 5.00pm or 6.00p.m. The relationship between language, thought and culture are also discussed in the Language Learning and Language Use module. Therefore, it is generally found that Western ESL learners such as French, Italian or Spanish tend to learn English faster compared to Non Western learners. Japanese, Chinese and Malaysian students tend to take longer because they also need to learn about the new culture.

19

CHAPTER 5

THE L2 READER

..........................

Language learning is not just about grammatical competence; it also involves sociolinguistic competence, discourse competence and strategic competence (Canale and Swain 1980). Learning language without attending to these competencies will not help learners to achieve full bilingual and bicultural status. The lack of such competencies will also lead to low reading proficiency.

Figure 5.13: Learning language is more than having grammatical competence

How does the degree of difference between the L1 and L2 influence reading in the L2? Discuss.

A teachers task is to be aware of students prior knowledge and to utilise their prior knowledge in comprehending the texts. Teachers need to help students tap into the appropriate network of prior knowledge before reading a text. Teachers also need to be aware of the prior knowledge required by the reading texts. If students do not have the prior knowledge necessary, the prior knowledge need to be developed and this can be done at the pre-reading stage which we will discuss more in the next chapter.

20

THE L2 READER

CHAPTER 5

5.1.5

FACTOR 5: OVER-RELIANCE ON DECODING SKILLS

Another problem that ESL learner faces is over-relying on decoding skills. There is a tendency for ESL learners to read word by word and translate every word that is read. This is especially for beginning learners of any language. To prove this statement, try answering the following questions:

When you read the following phrase how would you interpret it? To throw the baby with bath water Imagine that the ESL beginning language learners read the phrase, if they rely on their decoding skills, what will they think of?

Over-reliance on decoding skills are not exception among Malaysians. There are many reasons for readers to over-rely on their decoding skills. One is the emphasis given to reading aloud. Many students (and teachers too) perceive reading as reading aloud. This can lead to many challenges in learning to read in ESL. The sound system and one-word-one meaning will be discussed in the following section. (a) Sound System One of the problems faced by the multi-cultural Malaysian beginner readers is the difference between the sound system that exists between the English language and their first languages. Certain sounds may not exist in the learners' L1 but exist in the L2 and vice versa.

Generally, the Chinese students have problems with the [r] pronunciation and say "flied lice" /flajd lajs/ instead of "fried rice" /frajd rajs/ while the Malays tend not to contrast voiceless "th" [] and voiced "th" [ ]. They also tend to confuse voiced "th" [ ] with "d" [d]. Therefore, the word "brother" / bra / becomes "brader" / brad /.

Moreover, the sound symbol relationship in the English language is not consistent. One of the reasons is because many of the words in the English language are loaned from other languages. What this has resulted in is that there are so many rules that need to be learned and there are so many exceptions to the rules. Some grammarians have argued for fewer rules, but they end up having more exceptions to their rules. Others believe in having more rules so that they can afford fewer exceptions. Because of the inconsistency in the sound symbol correspondence in the English language, the use of phonics in the teaching of English has gone through many debates.

21

CHAPTER 5

THE L2 READER

..........................

Below are some phonic generalisations for the English language: a) When the letter C is followed by O or A, the sound of [k] is likely to be heard. b) When the letter C is followed by E or I, the sound [s] is likely to be heard. c) When C and H are next to each other, they make only one sound. d) When a word ends in CK, it has the same sound as [k] in book. e) CH is usually pronounced as it is in kitchen, catch, and chair [ t ], not like [ ] in ship.

Beginning ESL learners may have many pronunciation problems due to such inconsistencies. Malaysians are fortunate because the sound and spelling system in Bahasa Melayu is consistent. It is quite easy to teach Bahasa Melayu using phonics. Learners can then transfer their knowledge to learning English as a second language and learn the exceptions required if one still decides to use the phonics approach for beginner readers.

"One of the problems faced by the multi cultural Malaysian beginner readers is the difference between the sound system that exist between the English language and their first languages". Do you agree with the above statement? Justify your answer by citing specific examples of your own students. How do you propose to overcome such a challenge in your ESL reading class?

(b) One Word One Meaning Another problem that is faced by readers who over rely on decoding skills is that they tend to translate or find the meaning of every word and assume that the meaning of a sentence is equal to the meaning of each and every word in the sentence. As we know, word may have many meanings. For example, the word "table." The dictionary may define table as the furniture where one use to write or eat on. However, if we have phrases such as "table the motion," "multiplication table," "chart and table," "turn the tables," or "under the table" the definition of table is no more the physical object. The meaning of a sentence does not consist of the total meaning of the individual words. Beginner learners, who try to translate every word in a sentence and attempt to derive the

22

THE L2 READER

CHAPTER 5

meaning from it, may easily end up in despair. Learning to use the dictionary, choosing the entry that matches with the intended meaning is a skill that learners need to develop. 5.1.6 FACTOR 6: CONFIDENCE PROBLEM

Many ESL readers also need to be encouraged to take risks in reading. Many are not confident enough to make guesses about the meaning of the text and find themselves turning to the dictionary whenever they are faced with a difficult word. Perhaps this also has got to do with their overreliance on decoding skills. Frequent trips to the dictionary not only make reading slower, it also disrupts comprehension. Previous studies provide evidence that relying on the dictionary do not necessarily improve comprehension. Readers who relied on dictionaries took longer to read compared to those who did not. Readers with dictionaries also did not comprehend better than those without. Moreover, in real life situation, many of us do not open the dictionary whenever we come across a word that we do not know. What should be encouraged is the willingness for students to take risks in reading and make guesses on the meaning of the text. Students should read ahead whenever they come across a new word instead of stopping and opening the dictionary. Chances are they will discover that the overall meaning of the text is not impeded by the specific word that they did not know. They may also be able to guess the meaning of the unknown word from the contextual clues.

Figure 5.14: We are in need of students who are confident readers and able to apply the information they gain from reading

23

CHAPTER 5

THE L2 READER

..........................

SUMMARY

This chapter is an introduction to the L2 reader. The L2 reader is an entity in his own right and thus should be studies as such. Apart from the personal idiosyncrasies, the L2 commonly have specific common problems, needs, solutions and strategies that are distinct from those of L1. However, the difference between the L1 and L2 readers are a matter of degree that ranges from near resemblance to clear distinctness. This chapter will hopefully teach the student to handle the L2 better when they go out into the pedagogical world.

Why is prior knowledge important to schema theory? What are the two kind of knowledge and explain them?

GLOSSARY

Implications what happens because of this.

Interdependence mutual linking. Proficiency Strategic Threshold mastery, fluency. plan to reach an objective. border, end of a section.

24

Você também pode gostar

- Fix 1 SDocumento128 páginasFix 1 Swaveol100% (7)

- Articles of Indian Constitution in Telugu LanguageDocumento3 páginasArticles of Indian Constitution in Telugu Languagefacebookcontactme46% (24)

- B1 UNIT 3 Test Answer Key HigherDocumento2 páginasB1 UNIT 3 Test Answer Key HigherNatasha Vition60% (5)

- Out of My Head: SincereDocumento6 páginasOut of My Head: SincereMargaret Hoeschele100% (1)

- Early Language, Literacy, and Numeracy (ELLN)Documento18 páginasEarly Language, Literacy, and Numeracy (ELLN)rafaela villanueva88% (8)

- Comparing L1 and L2 ReadingDocumento6 páginasComparing L1 and L2 ReadingPierro De Chivatoz50% (2)

- Early Approaches To Second Language Acquisition - Written ReportDocumento6 páginasEarly Approaches To Second Language Acquisition - Written ReportMark Andrew Fernandez90% (10)

- Okell John Burmese An Introduction To The ScriptDocumento448 páginasOkell John Burmese An Introduction To The ScriptArben Anthony Quitos SaavedraAinda não há avaliações

- (Review) William Grabe - Insights Into Second Language Reading by Keiko KodaDocumento6 páginas(Review) William Grabe - Insights Into Second Language Reading by Keiko KodacommwengAinda não há avaliações

- Shaw MC Million Clean April 9Documento36 páginasShaw MC Million Clean April 9Ma KếtAinda não há avaliações

- A Cross Linguistic Study On Vocabulary KDocumento8 páginasA Cross Linguistic Study On Vocabulary KAmazing HolidayAinda não há avaliações

- M5 Materials For Developing Reading and WritingDocumento31 páginasM5 Materials For Developing Reading and WritingCatherine GauranoAinda não há avaliações

- The Language Factors and Socio CulturalDocumento8 páginasThe Language Factors and Socio CulturalMandar PediaAinda não há avaliações

- Second Language Reading Issus 1220335810653658 8Documento14 páginasSecond Language Reading Issus 1220335810653658 8Henni HerawatiAinda não há avaliações

- The Impact of L1 Metaphorical Comprehension On L2 Metaphorical Comprehension of Iraqi EFL LearnersDocumento7 páginasThe Impact of L1 Metaphorical Comprehension On L2 Metaphorical Comprehension of Iraqi EFL LearnersSuzan ShanAinda não há avaliações

- Book Review: Introducing Second Language Acquisition: A. OverviewDocumento4 páginasBook Review: Introducing Second Language Acquisition: A. OverviewYamany DarkficationAinda não há avaliações

- Good Reader and Poor ReaderDocumento18 páginasGood Reader and Poor ReadermasthozhengAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 2 (Comparing L1 and L2 Reading)Documento4 páginasChapter 2 (Comparing L1 and L2 Reading)Andi MagfirahAinda não há avaliações

- Content ServerDocumento8 páginasContent Serverkeramatboy88Ainda não há avaliações

- Cohen Paper1Documento71 páginasCohen Paper1JessieRealistaAinda não há avaliações

- STORCH Et Al-2003-TESOL QuarterlyDocumento11 páginasSTORCH Et Al-2003-TESOL QuarterlyL.Ainda não há avaliações

- Early Approaches To Second Language AcquisitionDocumento22 páginasEarly Approaches To Second Language AcquisitionAmaaal Al-qAinda não há avaliações

- Summarizing by Spanish Beginner LearnersDocumento13 páginasSummarizing by Spanish Beginner LearnersLau AlbertiAinda não há avaliações

- Grabe (2010) Fluency in ReadingDocumento13 páginasGrabe (2010) Fluency in ReadingInayati FitriyahAinda não há avaliações

- Approaches To Language in The Classroom ContextDocumento89 páginasApproaches To Language in The Classroom ContextEduardo SchillerAinda não há avaliações

- An Analysis of The Influence and Interference of l1 in The Teaching and Learning of l2 in Malaysian ClassroomsDocumento58 páginasAn Analysis of The Influence and Interference of l1 in The Teaching and Learning of l2 in Malaysian ClassroomsShamshurizat Hashim100% (3)

- Early Approaches To Second Language AcquisitionDocumento22 páginasEarly Approaches To Second Language AcquisitionAmaaal Al-qAinda não há avaliações

- Meaning-Mapping in The Bilingual Cognition and The RHM ModelDocumento20 páginasMeaning-Mapping in The Bilingual Cognition and The RHM ModelKhuram ShahzadAinda não há avaliações

- SLA-G Week5 Lesson1 Role of The L1Documento18 páginasSLA-G Week5 Lesson1 Role of The L1tayyabijazAinda não há avaliações

- Extensive Reading and Development of Different Aspects of L2 ProficiencyDocumento2 páginasExtensive Reading and Development of Different Aspects of L2 ProficiencySergio Cerda LiraAinda não há avaliações

- SdarticleDocumento4 páginasSdarticlenicolaecrisAinda não há avaliações

- #Daniel V. McCaffrey, Reading Latin Efficiently and The Need For Cognitive StrategiesDocumento21 páginas#Daniel V. McCaffrey, Reading Latin Efficiently and The Need For Cognitive StrategiesRonaldo TeixeiraAinda não há avaliações

- Language Learning - 2015 - Vandergrift - Learner Variables in Second Language Listening Comprehension An Exploratory PathDocumento27 páginasLanguage Learning - 2015 - Vandergrift - Learner Variables in Second Language Listening Comprehension An Exploratory Pathyoujin LeeAinda não há avaliações

- The Reading Matrix Vol. 7, No. 1, April 2007Documento21 páginasThe Reading Matrix Vol. 7, No. 1, April 2007Lidya_Rismaya_6886Ainda não há avaliações

- Second Language Research-2002-Kroll-137-71Documento36 páginasSecond Language Research-2002-Kroll-137-71S AAinda não há avaliações

- English L@2reading PDFDocumento213 páginasEnglish L@2reading PDFJairo Alonso Ariza Villa0% (1)

- Literature Review About Learning Foreign LanguageDocumento6 páginasLiterature Review About Learning Foreign LanguagetdqmodcndAinda não há avaliações

- Second Language Acquisition Literature ReviewDocumento8 páginasSecond Language Acquisition Literature Reviewafdtzfutn100% (1)

- WrittenReport (Group6) ENG101Documento11 páginasWrittenReport (Group6) ENG101Umar MacarambonAinda não há avaliações

- 4.theories of Second 15Documento59 páginas4.theories of Second 15Lebiram MabzAinda não há avaliações

- Effects of L1 Writing Experiences On L2 Writing Perceptions: Evidence From An English As A Foreign Language ContextDocumento17 páginasEffects of L1 Writing Experiences On L2 Writing Perceptions: Evidence From An English As A Foreign Language ContextPourya HellAinda não há avaliações

- Crossley McNamara 2011Documento2 páginasCrossley McNamara 2011Ariezq AhmadAinda não há avaliações

- BhelaDocumento10 páginasBhelaPunitha MohanAinda não há avaliações

- Session 1 Unit 2.3Documento10 páginasSession 1 Unit 2.3Katherine MondaAinda não há avaliações

- Reading: 9 The Lexical Plight in Second LanguageDocumento15 páginasReading: 9 The Lexical Plight in Second LanguageYuli ZhelyazkovAinda não há avaliações

- An Analysis of Interlanguage Features and EnglishDocumento7 páginasAn Analysis of Interlanguage Features and EnglishAviram Dash AviAinda não há avaliações

- InstructionsDocumento2 páginasInstructionsClarissa PacatangAinda não há avaliações

- AssignmentDocumento2 páginasAssignmentJay Antay FaanAinda não há avaliações

- Linguistics: Second Language AcquisitionDocumento25 páginasLinguistics: Second Language AcquisitionchamilaAinda não há avaliações

- ONLINE PRONOUN RESOLUTION IN L2 DISCOURSE L1 Influence and General Learner EffectsDocumento25 páginasONLINE PRONOUN RESOLUTION IN L2 DISCOURSE L1 Influence and General Learner EffectsAbdelhamid HamoudaAinda não há avaliações

- Issues in SLAR - D NunanDocumento18 páginasIssues in SLAR - D NunanPatriciaFranco100% (1)

- First Language Transfer and Second LDocumento24 páginasFirst Language Transfer and Second LThat XXAinda não há avaliações

- 1 Anxiety About L2 ReadingDocumento19 páginas1 Anxiety About L2 ReadingMargarita Hidalgo AntequeraAinda não há avaliações

- Voca 8Documento5 páginasVoca 8Quynh HoaAinda não há avaliações

- Name/s: Aina Margaret C. Celino Section: 11 - HUMSS 1 DLP 1: Writing A Book Review DirectionDocumento2 páginasName/s: Aina Margaret C. Celino Section: 11 - HUMSS 1 DLP 1: Writing A Book Review Direction11 - HUMSS 1 - Aina Margaret CelinoAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 1 Aulas 2 e 3Documento6 páginasChapter 1 Aulas 2 e 3matheusmpsAinda não há avaliações

- Learner LanguageDocumento32 páginasLearner LanguageRatihPuspitasariAinda não há avaliações

- Contrastive AnalysisDocumento7 páginasContrastive AnalysisKow Asoku NkansahAinda não há avaliações

- Second Language AcquisitionDocumento41 páginasSecond Language AcquisitionJean Aireen Bonalos EspraAinda não há avaliações

- Contrastive Analysis - Error Analysis PresentationDocumento13 páginasContrastive Analysis - Error Analysis PresentationLano PavarottyAinda não há avaliações

- Reading in A Second LanguageDocumento483 páginasReading in A Second LanguageKarolina Ci100% (2)

- English L2 Reading Getting To The Bottom (Barbara M. Birch)Documento251 páginasEnglish L2 Reading Getting To The Bottom (Barbara M. Birch)Heng Wen Zhuo100% (1)

- Interlingual TransferDocumento12 páginasInterlingual TransferzeeezieeAinda não há avaliações

- Cook 1992-Evidence For MulticompetenceDocumento35 páginasCook 1992-Evidence For MulticompetencekaylaAinda não há avaliações

- Fundamentals of Learning/Teaching English As Second/Foreign LanguageDocumento38 páginasFundamentals of Learning/Teaching English As Second/Foreign Languagebassia NoureenAinda não há avaliações

- English as a Foreign or Second Language: Selected Topics in the Areas of Language Learning, Teaching, and TestingNo EverandEnglish as a Foreign or Second Language: Selected Topics in the Areas of Language Learning, Teaching, and TestingAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 2 - Paper 2 - Section CDocumento3 páginasUnit 2 - Paper 2 - Section CEsther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Question Pen Sec. A Set 3Documento2 páginasQuestion Pen Sec. A Set 3Esther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Tick ( ) The Correct Answer: UPSR SK Paper 1-Question 22Documento3 páginasTick ( ) The Correct Answer: UPSR SK Paper 1-Question 22Esther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Question Pen Sec. B Set 3Documento3 páginasQuestion Pen Sec. B Set 3Esther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 2 - Paper 1 - QNS 21Documento1 páginaUnit 2 - Paper 1 - QNS 21Esther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Question 12-15 Set 3Documento1 páginaQuestion 12-15 Set 3Esther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Question Pen Sec. A Set 1Documento1 páginaQuestion Pen Sec. A Set 1Esther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Question Pen Sec. B Set 1Documento2 páginasQuestion Pen Sec. B Set 1Esther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Question Pen Sec. B Set 1Documento2 páginasQuestion Pen Sec. B Set 1Esther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Question Pen Sec. B Set 1Documento2 páginasQuestion Pen Sec. B Set 1Esther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Baca Cerita Dan Jawab Soalan-Soalan Yang Berikutnya..: Questions 16 To 18Documento2 páginasBaca Cerita Dan Jawab Soalan-Soalan Yang Berikutnya..: Questions 16 To 18Esther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Look at The Picture and Choose The Best Answer. Lihat Gambar Dan Pilih Jawapan Yang TerbaikDocumento2 páginasLook at The Picture and Choose The Best Answer. Lihat Gambar Dan Pilih Jawapan Yang TerbaikEsther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Question Pen Sec. A Set 2Documento1 páginaQuestion Pen Sec. A Set 2Esther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Questions 24 and 25: Soalan Yang BerikutnyaDocumento3 páginasQuestions 24 and 25: Soalan Yang BerikutnyaEsther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Baca Surat Berikut Dan Jawab Soalan-Soalan BerikutDocumento2 páginasBaca Surat Berikut Dan Jawab Soalan-Soalan BerikutEsther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Clothes and Food Fest: Teliti Notis Dan Baca Dialog Yang Diberi. Kemudian, Jawab Soalan-Soalan Yang BerikutnyaDocumento2 páginasClothes and Food Fest: Teliti Notis Dan Baca Dialog Yang Diberi. Kemudian, Jawab Soalan-Soalan Yang BerikutnyaEsther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Baca Petikan Di Bawah Dan Jawab Soalan-Soalan Yang BerikutDocumento2 páginasBaca Petikan Di Bawah Dan Jawab Soalan-Soalan Yang BerikutEsther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Section C (25 Marks) This Section Consists of Two Questions. Answer One Question OnlyDocumento3 páginasSection C (25 Marks) This Section Consists of Two Questions. Answer One Question OnlyEsther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Question 1-6 Set 3Documento2 páginasQuestion 1-6 Set 3Esther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Question 7-11 Set 2Documento2 páginasQuestion 7-11 Set 2Esther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Question 12-15 Set 1Documento1 páginaQuestion 12-15 Set 1Esther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Question 7-11 Set 1Documento1 páginaQuestion 7-11 Set 1Esther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Master Thesis 2009 Social Media MagnusSørdalDocumento148 páginasMaster Thesis 2009 Social Media MagnusSørdalEsther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Read The Passage Below Carefully and Answer The Questions That Follow. Baca P Etik An Di Baw A H Dan Jaw Ab Soala N-S Oalan Yan G B Eri Kutn y ADocumento2 páginasRead The Passage Below Carefully and Answer The Questions That Follow. Baca P Etik An Di Baw A H Dan Jaw Ab Soala N-S Oalan Yan G B Eri Kutn y AEsther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Fedorov PavelDocumento41 páginasFedorov PavelEsther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Question 7-11 Set 3Documento2 páginasQuestion 7-11 Set 3Esther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Communicative Language TeachingDocumento7 páginasCommunicative Language TeachingEsther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Question 1-6 Set 2Documento2 páginasQuestion 1-6 Set 2Esther Ponmalar CharlesAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 1-Understanding Second Language Teaching and LearningDocumento31 páginasChapter 1-Understanding Second Language Teaching and LearningEsther Ponmalar Charles100% (2)

- Methodology of Arabic 2015Documento44 páginasMethodology of Arabic 2015ShahidRafiqueAinda não há avaliações

- FRE 113: Introduction To French Comprehension 1 Mr. Daouda Issiaka Lecture (C19:1)Documento3 páginasFRE 113: Introduction To French Comprehension 1 Mr. Daouda Issiaka Lecture (C19:1)KiaraAinda não há avaliações

- Shortcuts For Special Characters and Symbols in MS WordDocumento33 páginasShortcuts For Special Characters and Symbols in MS WordParameshAinda não há avaliações

- Factors Affecting Speaking Performance BC ThesisDocumento43 páginasFactors Affecting Speaking Performance BC Thesisdianamilenacelis100% (2)

- Palaeo GraphyDocumento25 páginasPalaeo GraphyAvinashKharatAinda não há avaliações

- Semitic Languages Outline Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta PDFDocumento754 páginasSemitic Languages Outline Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta PDFfabianhoks12Ainda não há avaliações

- Demonstrative S - Mg. Nancy Leon Pereyra - Ingles 01Documento3 páginasDemonstrative S - Mg. Nancy Leon Pereyra - Ingles 01Daniel EspirituAinda não há avaliações

- Fossilization and CPHDocumento9 páginasFossilization and CPHSalma Imran KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 3 Practice Test PDFDocumento6 páginasUnit 3 Practice Test PDFFahad Areeb100% (1)

- Proforma For Project Proposals of Aff. Colleges For Undergrade Degree ProgramDocumento7 páginasProforma For Project Proposals of Aff. Colleges For Undergrade Degree ProgramihsanAinda não há avaliações

- Tos 4TH English 7Documento3 páginasTos 4TH English 7Manel Remirp100% (1)

- Language Maintenance and ShiftDocumento9 páginasLanguage Maintenance and ShiftArifinAtmadja100% (1)

- Mat Ntse 2020 Stage 1 Paper Solutions Maharashtra PDFDocumento25 páginasMat Ntse 2020 Stage 1 Paper Solutions Maharashtra PDFvinod meneAinda não há avaliações

- Project Proposal For Sinhala Language ProcessingDocumento11 páginasProject Proposal For Sinhala Language ProcessingSuranga Premakumara100% (3)

- Phonics PPT For Parents 26 9Documento35 páginasPhonics PPT For Parents 26 9Yee Mon AungAinda não há avaliações

- Comparative Forms of Adjectives Rules Esl Classroom PosterDocumento1 páginaComparative Forms of Adjectives Rules Esl Classroom PosterMons. Juan Carlos OrtizAinda não há avaliações

- HSK 1 in A NutshellDocumento192 páginasHSK 1 in A NutshellChanAinda não há avaliações

- Why Study Ancient GreekDocumento2 páginasWhy Study Ancient GreekJose A. CastroAinda não há avaliações

- Les Mots D'emprunt D'origine Espagnole Dans Le Parler Oranais / Díaz Oti VirginiaDocumento19 páginasLes Mots D'emprunt D'origine Espagnole Dans Le Parler Oranais / Díaz Oti VirginiaALTRALANG JournalAinda não há avaliações

- Annual Plan 9th Cambridge IGCSE As A Second Language 5th EditionDocumento4 páginasAnnual Plan 9th Cambridge IGCSE As A Second Language 5th EditionJouda Ulan100% (1)

- CHP 1 - What Is LanguageDocumento37 páginasCHP 1 - What Is LanguageSYARMIMI YUSOFAinda não há avaliações

- ENG-113 Introduction To Linguistics-IDocumento4 páginasENG-113 Introduction To Linguistics-IAbdul Waheed100% (1)

- Lexical Variation PDFDocumento20 páginasLexical Variation PDFChingiAinda não há avaliações

- Analytic Scale B2Documento1 páginaAnalytic Scale B2Ana Luiza BernardesAinda não há avaliações