Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Uninvestigated Dyspepsia Versus Investigated Dyspepsia

Enviado por

Yuriko AndreDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Uninvestigated Dyspepsia Versus Investigated Dyspepsia

Enviado por

Yuriko AndreDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

C L I N I C A L P R A C T I C E

yspepsia versus Investigated

Ari Fahrial yam

INTRODUCTION

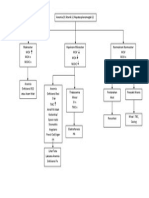

The term "dyspepsia" comes fi-om a Greek word meaning "bad digestion", or a collection of painful and uncomfortable feelings in the epigastric region.' In the latest consensus in 1999 in Rome, dyspepsia experts around the world agreed on the definition of dyspepsia as pain or disconlfort in the middle upper abdomen. The consequence of this definition is that pain on the left or right hypochondriac region is not considered as dyspepsia.' Symptoms that often accompany dyspepsiaother than pain or discomfort in the epigastrium are as follows: patients feel quickly satiated, and may complain of . ~ symptoms are gassiness, nausea, and ~ o m i t i n g Such often found in daily clinical practice, and patients generally recognize it as "nznng". The prevalence rate for dyspepsia in the United States is almost 26% while the prevalence rate in theunited Kingdom almost reaches 41%." Diagnostic evaluation of patients with dyspepsia is crucial. Therefore. the terms "uninvestigated dyspepsia" and "investigated dyspepsia" were conceived. By direct definition, uninvestigated dyspepsia relates to patients with dyspepsia that have not been further investigated by endoscopy, while iuvestigated dyspepsia refers to patients with known organic dyspepsia (including gastric or duodena! ulcer, cancer or gastroesophageal reflux disease) or functional dyspepsia (see Figure 1). Before we evaluate dyspeptic syndrome, we should make sure we are truly dealing with just dyspepsia. We should evaluate whether epigastric discomfort is related to heartbum in the chest and regurgitation, which would suggest Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). And also we should ask whether the pain is reduced by the use of antacids. We should find out whether we are

myodealing with billiaty colic or chest pain due to cardial infarction. We also should to look for about drugs that the patient often takes. This is important for furiher evaluation in dyspepsia management.

DYSPEPSIA SYMPTOMS

Symptoms often found in dyspepsia include: Epigastric pain, which is a subjective col~lplaint of uncomfortable sensations. Certain patients state that they feel something wrong in their stomach. Epigastric discomfort: a subjective feeling of discomfort, and not pain. Early satiety: a feeling of fullness at the beginning of a meal, unrelated to the portion of food intake. The patient is usually unable to finish hislher food. Fullness: an unpleasant sensation as if food were withheld in the stomach, which could occur after meals. Gassiness in the upper abdomen, stiffness must be differentiated from distention. Nausea: feeling that they are about to vomit. These complaints could be recent or might have taken place for several months or years prior to investigation. In general, a length of 4 weeks i s considered to rule out temporary symptoms from notmal physiologic processes due to an empty ~ t o m a c h . ~

CLINICAL APPROACH FOR DYSPEPSIA

The diagnostic approach for dyspepsia requires time and money. Thus, a precise approach should be taken to determine dyspepsia cases that require further investigation, or we could try giving medication beforehand, In dealing with dyspepsia cases, there are several things that could point to further investigation, such as age, symptoms, and helicobacter pylori ~ t a t u s . ~

The Patient's Age

D i v i s i o n of Gnsrrocrirri.ologr, Depoi.rmeut of Intliemal Mediciiie. Fmtd~ of ,medicine, U n i w r s i Q of h d o m s i o

Age is an important factor that requires first hand attention. The older patients have higher rate of organic

k r i Fahriai Syarn, eta1

Acta Med I n d o n e s - I n d o n e s I I n t e r n Med

disovde~ 4 study by Rani reported to PEGI-PGI-PPHI National Cong1-ess in the year 2001 demonstrated the same data, where duodenal ulcer and gastric ulcer were more colnn~only found in older patients, compared to organic disorders found in studies of uninvestigated dyspepsia.' The cut-off age is 45 years old. The national consensus for Helicobacter pylori infection eradication established 45 years as the cut-off age for investigation? Thus, dyspepsia cases in patients over the age of 45 ycars with dyspepsia cases require endoscopic examination to rule out possible organic disorclers.

HELICOBACTER PYLOWI STKfUS AND THE USE OF MOM-STEROIDAL ANTI-INFLAMMATORY DRUGS (NSAIDS)

Upper GI symptoms

\ , ,

Lower GI symptoms

I

I

II

,\

GERD

\4

Dyspepsia

-> IBS

Ulcer like

Dysrnotility like

~

L---

-~~~

GERD: Gastrocsaphagoal reflux disease

IBS: Irritable bowel syndrome

Figilre 1. The Heiationship Between Dyspepsia and2 Functionai Dyspepsia. lnvestigaied and Uninvestigated Dyspepsia

The presence of Helicobacter pylori is closely associated with the development of peptic ulcer. All patients infected by H. pylol-i in their gaster will suffer from chronic gastritis. This occurs bccanse the microorganism infiltuates cells of the gastl-icmucosa. In several patients, this occurs asyniptomatically, but the presence of Lhis microorganism increases the incidence of peptic ulcer and adenocarcinoma of the gastric anthrum and c o r p u ~ . ' ~ A case of peptic ulcer with H. pylori was reported by Syam, et. Al:" in a 52-year old woman with complaints of epigastric pain accompanied by nausea, vomiting.. anorexia, and gassiness. Endoscopic evaluation demonstrated a peptic ulcer and histopathologic evaluation found Helicobacter pylori." The latest study, by Japanese experts, on the relationship between H. pylori infection and the incidence of gastric cancer demonstrate gastric cancer in patients suffering from H. pylori infection, which did not occur in uninlected patients. In addition, patients with H. pylori infection and non-ulcer dyspepsia, gastric ulcer, as well as hyperplastic polip of the gaster also have a greater risk for gastric cancer compared to duodenal u l c e ~ . ' ~ Bearing in mind the con~plicationscaused by H. pylori, serologic screening for this infection is I-endered necessary. T h e national consensus on H. pylori infection eradication established H. pylori serologic tcsting as the initial step fol-dyspepsia patients in the conlnlunity as well as for dyspepsia patients undergoing endoscopy (see appendix). History of the use of drugs that could induce dyspepsia should be inqnired about. NSAIDs and aspirin are the main cause for dyspepsia, while steroids, teophyllin and calciun~antagonists are less frequent causes of dyspepsia.

The Role of Endoscopy in Dyspepsia

SYMPTOMS

Symptoms that warn us of the presence of an organic disorder include: dyspepsia symptoms accompanied by weight loss, bleeding in the form of liematemesis or melena: dysphagia and continuous vomiting. Other literature snggest alarm syn~ptoms are as follows: weight loss. anemia, vomiting, jaundice, and epigasiric mass? Additional symptoms indicate further exainination. Ulcer-like oi-dysmotility-like symptoms do not indicate further investigaiion.'"

As an investigative tool for dyspepsia, endoscopy is still the gold standard instrulnent and is superior to radiologic imaging. Endoscopy allows us to see the rnacros:opic structure of the gastrointestinal Lract. If abnormality is found, biopsy can be performed for l~istopathologic evaluation. In addition, biopsy allows us to obtain samples for rapid urease testing (CLO), Helicobacter pylori culture; and PCR."echnological developments of endoscopy allow us to take more opti~nal therapeutic action.

Você também pode gostar

- I. IntroductionDocumento11 páginasI. IntroductionnsgcareplannerAinda não há avaliações

- HelicobaterDocumento8 páginasHelicobaternainggolan Debora15Ainda não há avaliações

- Organic Versus Functional: DyspepsiaDocumento16 páginasOrganic Versus Functional: DyspepsiahelenaAinda não há avaliações

- Peptic Ulcer DiseaseDocumento6 páginasPeptic Ulcer DiseaseChino Paolo SamsonAinda não há avaliações

- Dysphagia, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo EverandDysphagia, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Treatment And Related ConditionsNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Functional Dyspepsia: Recent Advances in Pathophysiology: Update ArticleDocumento5 páginasFunctional Dyspepsia: Recent Advances in Pathophysiology: Update ArticleDen BollongAinda não há avaliações

- Abct Journal ReadingsDocumento9 páginasAbct Journal ReadingsJane Arian BerzabalAinda não há avaliações

- Case Study (Medical Ward)Documento5 páginasCase Study (Medical Ward)George Mikhail Labuguen100% (1)

- Hematemesis Melena Due To Helicobacter Pylori Infection in Duodenal Ulcer: A Case Report and Literature ReviewDocumento6 páginasHematemesis Melena Due To Helicobacter Pylori Infection in Duodenal Ulcer: A Case Report and Literature ReviewWahyu Agung PribadiAinda não há avaliações

- Review Article Helicobacter Pylori Infection: Dyspepsia: When and How To Test ForDocumento10 páginasReview Article Helicobacter Pylori Infection: Dyspepsia: When and How To Test ForAyu Trisna PutriAinda não há avaliações

- Dyspepsia PDFDocumento14 páginasDyspepsia PDFCdma Nastiti FatimahAinda não há avaliações

- Dispepsia 1Documento16 páginasDispepsia 1nainggolan Debora15Ainda não há avaliações

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Other Functional Gastrointestinal DisordersDocumento3 páginasIrritable Bowel Syndrome and Other Functional Gastrointestinal DisordersdavpierAinda não há avaliações

- Peptic UlcerDocumento14 páginasPeptic Ulcerlokoerik6660% (1)

- Nonerosive Reflux Disease As A Presentation of Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux DiseaseDocumento4 páginasNonerosive Reflux Disease As A Presentation of Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux DiseaseAlFi KamaliaAinda não há avaliações

- Hematemesis Melena Due To Helicobacter Pylori Infection in Duodenal Ulcer: A Case Report and Literature ReviewDocumento6 páginasHematemesis Melena Due To Helicobacter Pylori Infection in Duodenal Ulcer: A Case Report and Literature ReviewodiAinda não há avaliações

- Duodenal Ulcer-1Documento43 páginasDuodenal Ulcer-1Roshan GhimireAinda não há avaliações

- Abdominal TB Causing Intestinal ObstructionDocumento10 páginasAbdominal TB Causing Intestinal ObstructionCleoanne GallegosAinda não há avaliações

- Evaluation and Treatment of Dyspepsia: ReviewDocumento6 páginasEvaluation and Treatment of Dyspepsia: ReviewNurul Afifah MunayaAinda não há avaliações

- Dyspepsia in Children IFFGDDocumento2 páginasDyspepsia in Children IFFGDNorman Alexander TampubolonAinda não há avaliações

- Seminar: Albert J Bredenoord, John E Pandolfi No, André J P M SmoutDocumento10 páginasSeminar: Albert J Bredenoord, John E Pandolfi No, André J P M SmoutIsmael SaenzAinda não há avaliações

- Patient Scenario, Chapter 45, Nursing Care of A Family When A Child Has A Gastrointestinal DisorderDocumento93 páginasPatient Scenario, Chapter 45, Nursing Care of A Family When A Child Has A Gastrointestinal DisorderDay MedsAinda não há avaliações

- DispepsiaDocumento11 páginasDispepsiaPendikAinda não há avaliações

- Dental Management of Diseases of The Gastrointestinal SystemDocumento61 páginasDental Management of Diseases of The Gastrointestinal SystemkomalgorayaAinda não há avaliações

- Functional Dyspepsia: Advances in Diagnosis and Therapy: ReviewDocumento9 páginasFunctional Dyspepsia: Advances in Diagnosis and Therapy: Reviewjenny puentesAinda não há avaliações

- 4 U1.0 B978 1 4160 6189 2..00012 3..DOCPDFDocumento9 páginas4 U1.0 B978 1 4160 6189 2..00012 3..DOCPDFJuan HernandezAinda não há avaliações

- K-16 Peptic Ulcer DiseaseDocumento78 páginasK-16 Peptic Ulcer DiseasecarinasheliapAinda não há avaliações

- Robinson 2016Documento20 páginasRobinson 2016sadiqAinda não há avaliações

- Merec Briefing No32Documento8 páginasMerec Briefing No32Riefka Ananda ZulfaAinda não há avaliações

- NSAIDS PepticUlcers 508Documento12 páginasNSAIDS PepticUlcers 508razvanseicaru97Ainda não há avaliações

- Dyspepsia: Nausea and VomitingDocumento2 páginasDyspepsia: Nausea and VomitingNoeMedrAinda não há avaliações

- Lecture 1 & 2 Peptic Ulcer DiseaseDocumento26 páginasLecture 1 & 2 Peptic Ulcer DiseaseNovi ArthaAinda não há avaliações

- Epidemiology of Gastrointestinal Problems: M. Rum Rahim, MD., MSCDocumento34 páginasEpidemiology of Gastrointestinal Problems: M. Rum Rahim, MD., MSCNur FitriahAinda não há avaliações

- Esophageal StrictureDocumento6 páginasEsophageal StrictureŽäíñäb ÄljaÑabìAinda não há avaliações

- Dyspepsia Management Guidelines: PrefaceDocumento9 páginasDyspepsia Management Guidelines: PrefaceRiefka Ananda ZulfaAinda não há avaliações

- A Simple Guide to Gastritis and Related ConditionsNo EverandA Simple Guide to Gastritis and Related ConditionsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (3)

- Dolor Abdominal Basado en EvidenciaDocumento26 páginasDolor Abdominal Basado en EvidenciaElberAinda não há avaliações

- Patient With RIF Pain: Differentials & ManagementDocumento4 páginasPatient With RIF Pain: Differentials & ManagementgeotrophAinda não há avaliações

- Duodenal Ulcer - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocumento6 páginasDuodenal Ulcer - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelfimehap033Ainda não há avaliações

- Nejm 2015 Functional DyspepsiaDocumento12 páginasNejm 2015 Functional DyspepsiarisewfAinda não há avaliações

- 1998 19 337 Karen F. Murray and Dennis L. Christie: Pediatr. RevDocumento7 páginas1998 19 337 Karen F. Murray and Dennis L. Christie: Pediatr. RevMia Lesaca-MedinaAinda não há avaliações

- CTC Gerd FinalDocumento36 páginasCTC Gerd FinaljaipreyraAinda não há avaliações

- Gastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease ( GERD)Documento31 páginasGastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease ( GERD)Malueth AnguiAinda não há avaliações

- Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Pediatric Patients A Literature ReviewDocumento8 páginasManagement of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Pediatric Patients A Literature ReviewAndhika DAinda não há avaliações

- Some Causes of Upper Midline Abdominal PainDocumento2 páginasSome Causes of Upper Midline Abdominal PainChris RayAinda não há avaliações

- DyspepDocumento2 páginasDyspepGeorge WinchesterAinda não há avaliações

- Functional GI Disorder Rome IVDocumento10 páginasFunctional GI Disorder Rome IVDr Reza ModarresAinda não há avaliações

- Functional Dyspepsia: Review ArticleDocumento11 páginasFunctional Dyspepsia: Review Articlejenny puentesAinda não há avaliações

- New Articles in This Journal Are Licensed Under A Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 United States LicenseDocumento16 páginasNew Articles in This Journal Are Licensed Under A Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 United States Licenseandi hajrahAinda não há avaliações

- 2437 Chap01Documento5 páginas2437 Chap01Ahsan KabirAinda não há avaliações

- Update On The Evaluation and Management of Functional DyspepsiaDocumento7 páginasUpdate On The Evaluation and Management of Functional DyspepsiaDenuna EnjanaAinda não há avaliações

- Nejmcp 2114026Documento10 páginasNejmcp 2114026Engin AltınkayaAinda não há avaliações

- RTD Ard DR ErwinDocumento99 páginasRTD Ard DR ErwinMuhammad Taufiq Rustam AjiAinda não há avaliações

- Nejmcp 2114026Documento10 páginasNejmcp 2114026Cristina Adriana PopaAinda não há avaliações

- INTUSSUSCEPTIONDocumento3 páginasINTUSSUSCEPTIONS GAinda não há avaliações

- Research Article: Low Prevalence of Clinically Significant Endoscopic Findings in Outpatients With DyspepsiaDocumento7 páginasResearch Article: Low Prevalence of Clinically Significant Endoscopic Findings in Outpatients With DyspepsiaKurnia pralisaAinda não há avaliações

- Tinjauan PustakaDocumento25 páginasTinjauan PustakaShirota_senseiAinda não há avaliações

- Abdominal Pain - Royal Children HospitalDocumento4 páginasAbdominal Pain - Royal Children HospitalMehrdad IraniAinda não há avaliações

- Gastritis Bahasa InggrisDocumento7 páginasGastritis Bahasa InggrisNieq Cutex CelaluingindimandjaAinda não há avaliações

- Signs and Symptoms: AdultsDocumento15 páginasSigns and Symptoms: AdultsHelen McClintock100% (1)

- Midgut VolvulusDocumento2 páginasMidgut VolvulusYuriko AndreAinda não há avaliações

- Reseach Poster Handout PrintDocumento1 páginaReseach Poster Handout PrintYuriko AndreAinda não há avaliações

- EnchantmentanaDocumento50 páginasEnchantmentanamealecsandraAinda não há avaliações

- Lampiran A (IKA) PDFDocumento1 páginaLampiran A (IKA) PDFYuriko AndreAinda não há avaliações

- How Are We: PresentingDocumento44 páginasHow Are We: PresentingMuhammad Zufar Bin MarwahAinda não há avaliações

- Surat LaborDocumento2 páginasSurat LaborYuriko AndreAinda não há avaliações

- Apa (Ton) Broeders, Ma PHD University of Leiden NL Netherlands Forensic Institute, Rijswijk NLDocumento10 páginasApa (Ton) Broeders, Ma PHD University of Leiden NL Netherlands Forensic Institute, Rijswijk NLYuriko AndreAinda não há avaliações

- Encoded Evidence: Dna in Forensic Analysis: PerspectivesDocumento1 páginaEncoded Evidence: Dna in Forensic Analysis: PerspectivesYuriko AndreAinda não há avaliações

- TB Statistics and Key Facts Feb 2014Documento3 páginasTB Statistics and Key Facts Feb 2014Yuriko AndreAinda não há avaliações

- Review Of: Equivocal Child AbuseDocumento1 páginaReview Of: Equivocal Child AbuseYuriko AndreAinda não há avaliações

- Jfo 12275Documento4 páginasJfo 12275Yuriko AndreAinda não há avaliações

- Eviden BAsed Medicine For PBLDocumento33 páginasEviden BAsed Medicine For PBLamiruddin_smartAinda não há avaliações

- Midgut VolvulusDocumento2 páginasMidgut VolvulusYuriko AndreAinda não há avaliações

- Jfo 12273Documento2 páginasJfo 12273Yuriko AndreAinda não há avaliações

- Uillain Arré Yndrome: L A. M, MDDocumento4 páginasUillain Arré Yndrome: L A. M, MDYuriko AndreAinda não há avaliações

- Apa (Ton) Broeders, Ma PHD University of Leiden NL Netherlands Forensic Institute, Rijswijk NLDocumento10 páginasApa (Ton) Broeders, Ma PHD University of Leiden NL Netherlands Forensic Institute, Rijswijk NLYuriko AndreAinda não há avaliações

- Forensic Art Guidelines SGFAFI1 ST EdDocumento24 páginasForensic Art Guidelines SGFAFI1 ST EdYuriko AndreAinda não há avaliações

- Matriks KegiatanDocumento1 páginaMatriks KegiatanErni Yessyca SimamoraAinda não há avaliações

- Withholding or Withdrawing LifeDocumento5 páginasWithholding or Withdrawing LifeYuriko AndreAinda não há avaliações

- P ('t':'3', 'I':'669120784') D '' Var B Location Settimeout (Function ( If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') ( B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Documento14 páginasP ('t':'3', 'I':'669120784') D '' Var B Location Settimeout (Function ( If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') ( B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Yuriko AndreAinda não há avaliações

- 772980Documento14 páginas772980Yuriko AndreAinda não há avaliações

- Movement DisorderDocumento37 páginasMovement DisorderFalcon DarkAinda não há avaliações

- KP 1.1.15 Teknik Presentasi IlmiahDocumento21 páginasKP 1.1.15 Teknik Presentasi IlmiahfitriahendricoAinda não há avaliações

- Book Review Forensic Testimony: Science, Law and Expert EvidenceDocumento4 páginasBook Review Forensic Testimony: Science, Law and Expert EvidenceYuriko AndreAinda não há avaliações

- P ('t':'3', 'I':'669097626') D '' Var B Location Settimeout (Function ( If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') ( B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Documento5 páginasP ('t':'3', 'I':'669097626') D '' Var B Location Settimeout (Function ( If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') ( B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Yuriko AndreAinda não há avaliações

- 3 (Problem-Based Learning)Documento36 páginas3 (Problem-Based Learning)Ayu AzlinaAinda não há avaliações

- Leadership and Teamwork: Rahmatina B. Herman Bagian Pendidikan Kedokteran Fk-UnandDocumento22 páginasLeadership and Teamwork: Rahmatina B. Herman Bagian Pendidikan Kedokteran Fk-Unandsandurezu100% (1)

- Evaluation and Management of Dyspepia (1999)Documento14 páginasEvaluation and Management of Dyspepia (1999)Yuriko AndreAinda não há avaliações

- Functional Dyspepsia - Past, Present, and Future (2008)Documento6 páginasFunctional Dyspepsia - Past, Present, and Future (2008)Yuriko AndreAinda não há avaliações

- Uninvestigated Dyspepsia Versus Investigated DyspepsiaDocumento3 páginasUninvestigated Dyspepsia Versus Investigated DyspepsiaYuriko AndreAinda não há avaliações

- Colorectal Cancer Genetic SyndromesDocumento1 páginaColorectal Cancer Genetic SyndromesRyan GosserAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal Dian Syahna Nazella Reviisi-1Documento10 páginasJurnal Dian Syahna Nazella Reviisi-1Darwin AllAinda não há avaliações

- Liver TransplantationDocumento22 páginasLiver Transplantationrajan kumar100% (6)

- Upper Gastrointestinal BleedingDocumento24 páginasUpper Gastrointestinal BleedingDr.Sathaporn Kunnathum100% (1)

- Gastrointestinal: Bleeding in Infants and ChildrenDocumento16 páginasGastrointestinal: Bleeding in Infants and ChildrenAdelia AnggrainiAinda não há avaliações

- Atlas of Sailvary Gland DiseaseDocumento4 páginasAtlas of Sailvary Gland DiseaseMohammed FeroAinda não há avaliações

- Volvulus MedscapeDocumento7 páginasVolvulus MedscapeHanny Novia RiniAinda não há avaliações

- 7 - The Biliary TractDocumento48 páginas7 - The Biliary TractKim RamosAinda não há avaliações

- DiverticulitisDocumento34 páginasDiverticulitisSahirAinda não há avaliações

- Gastrointestinal Disease: Oral MedicineDocumento11 páginasGastrointestinal Disease: Oral Medicineحمزه التلاحمهAinda não há avaliações

- Paralytic Ileus: Prepared By: Laurence A. Adena, ManDocumento43 páginasParalytic Ileus: Prepared By: Laurence A. Adena, ManJanah Beado PagayAinda não há avaliações

- Gastroenterology An Illustrated Colour TextDocumento127 páginasGastroenterology An Illustrated Colour Textariana_moni1416100% (3)

- Acute Cholecystitis:: Etiological TypesDocumento5 páginasAcute Cholecystitis:: Etiological Typesvivek yadavAinda não há avaliações

- Insignis Surgery 2 Gallbladder and Extrahepatic Biliary SystemDocumento7 páginasInsignis Surgery 2 Gallbladder and Extrahepatic Biliary SystemPARADISE JanoAinda não há avaliações

- Stomach Assignment (1) - 1Documento22 páginasStomach Assignment (1) - 1Irfan UllahAinda não há avaliações

- History Taking For CholelithiasisDocumento6 páginasHistory Taking For CholelithiasisToria053Ainda não há avaliações

- Intestinal Obstruction in Paediatrics - James GathogoDocumento21 páginasIntestinal Obstruction in Paediatrics - James GathogoMalueth Angui100% (1)

- Barium Swallow: DR Akash Bhosale Jr1Documento66 páginasBarium Swallow: DR Akash Bhosale Jr1Aakash BhosaleAinda não há avaliações

- Recognizing Bowel Obstruction and IleusDocumento35 páginasRecognizing Bowel Obstruction and IleusmustikaAinda não há avaliações

- Sucrose IntoleranceDocumento4 páginasSucrose IntoleranceJill BertrandAinda não há avaliações

- Acute AbdomenDocumento43 páginasAcute AbdomenamerAinda não há avaliações

- Hirschsprung's Disease (Aganglionic Megacolon)Documento3 páginasHirschsprung's Disease (Aganglionic Megacolon)JOANMA_NEWAinda não há avaliações

- Pathophysiology of CholecystitisDocumento2 páginasPathophysiology of CholecystitisAnonymous gDp7y3Cl86% (21)

- Case Presentation by Sruthi TPDocumento13 páginasCase Presentation by Sruthi TPsruthi T PAinda não há avaliações

- Ulcerative Colitis Concept MapDocumento1 páginaUlcerative Colitis Concept MapIris MambuayAinda não há avaliações

- Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux in Elderly: Dr. Johanes Intandri Tjundawan SP - PDDocumento37 páginasManagement of Gastroesophageal Reflux in Elderly: Dr. Johanes Intandri Tjundawan SP - PDAditya NobelAinda não há avaliações

- Althazar Score: Grading of PancreatitisDocumento1 páginaAlthazar Score: Grading of PancreatitisJuan GomezAinda não há avaliações

- DISTURBANCES IN ABSORPTION AND ELIMINATION NotesDocumento7 páginasDISTURBANCES IN ABSORPTION AND ELIMINATION NotesHoneylette DarundayAinda não há avaliações

- Cholelithiasis RLDocumento29 páginasCholelithiasis RLPrincess Joanna Marie B DelfinoAinda não há avaliações

- Perforasi GasterDocumento22 páginasPerforasi GasterMyra MieraAinda não há avaliações