Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Inclusion Through Care: An Analysis of How Long-Term Care Policies Can Promote Social Inclusion For People With Disabilities

Enviado por

RooseveltHousePPITítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Inclusion Through Care: An Analysis of How Long-Term Care Policies Can Promote Social Inclusion For People With Disabilities

Enviado por

RooseveltHousePPIDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

INCLUSION THROUGH CARE

AN ANALYSIS OF HOW LONG-TERM CARE POLICIES CAN PROMOTE SOCIAL INCLUSION FOR

PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES

Audrey Stienon

Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute at Hunter College

Public Policy Capstone

December 4, 2013

Stienon, 1

Table of Contents

Executive Summary !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! "

Disability, Inclusion, and Care !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! #

The Importance of Long-Term Care for the Disabled!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! #

Stakeholders of Long-Term Care Policies !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! $

Defining Disability!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! $

The Medical Model!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! %

The Social Model !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! %

The Capabilities Framework !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! %

Intersecting the Models !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! &

Policy Trends of Long-Term Disability Care !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! &

Trend #1: Segregation and Institutionalization!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! &

Trend #2: Deinstitutionalization !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! '

Deinstitutionalization of the Mentally Ill.................................................................................................. 9

Deinstitutionalization in New York......................................................................................................... 1u

Trend #3: Home and Community Based Care (HCBC) !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!((

Trend #4: Rights Based Policy!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!("

A New Focus for Future Policy!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! ("

Promoting Health !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!()

Promoting Social Integration!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!()

Spectrum of Care!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! (#

Institutions and Nursing Homes Care Apart From Society!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!(#

Home and Community Based Care The System As We Are Now Building It!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!(*

Integration!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!($

Case Study: Independence Care Systems!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! ($

Policy Recommendations !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! (&

Conclusion!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! ('

Bibliography !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! "+

Stienon, 2

Executive Summary

People with disabilities are unable to participate fully in our society. Demographically

speaking, the disabled are poorer, less healthy, less educated, less employed and less

paid.

1

Several laws exist protecting their right to be fully included in society, and yet our

policies for long-term care perpetuate their segregation. This paper will discuss ways in

which policies can be used to care for the disabled while allowing for and encouraging

their full participation in society.

There are two basic definitions of disability. The medical model describes disability as

being caused by a persons impairment, and therefore recommends policies to offer

treatment for these impairments. The social model defines disability as being caused by a

set of social barriers that put people with impairments at a disadvantage, and therefore

recommends policies to remove or these social barriers. The capabilities framework,

developed by Amartya Sen, offers a way to reconcile these two models, by measuring

equality based on peoples capabilities to achieve certain end goals.

2

Policies should

consider the intersection of these models of disability when considering ways to integrate

the disabled into society.

People with disabilities began to be explicitly segregated from society during the

industrial revolution, when they began to be placed into institutions. In the 1960s,

disability rights organizations began to advocate for the right of all individuals to

participate in society a movement that spurred a deinstitutionalization movement across

the country. Unfortunately, the poorly coordinated deinstitutionalization movement for

the mentally ill demonstrates the risks of closing institutions without ensuring that

communities have the proper resources to care for the medical needs of those leaving

these institutions. Home and community based care services offer an alternative to

institutions that allow the disabled to engage with society, and yet many of these care

providers continue to solely emphasize the medical needs of their clients. In other parts of

the world, rights based policies are being used to ensure that social barriers to the

inclusion of people with disabilities are removed.

When comparing alternative methods for providing long-term care for people with

disabilities, policymakers must consider how well they address the issues raised by both

models of disability, and must consider how well they promote both health and social

inclusion.

Alternative policies for providing care can also be compared on a spectrum that measures

how much each allows for integration in society. At one end of this spectrum lie

institutions, which promote full segregation. These might make the provision of medical

care easier, but they are difficult to hold accountable, and prevent people with disabilities

1

Biault, !"#$%&'() +%,- .%)'/%0%,%#) 12324 567)#-608 9&6(6"%& :,',7).

2

Sen, .#;#06<"#(, ') =$##86".

Stienon, S

from engaging with society. At the other end of the spectrum lie community-based

policies that also combat social barriers to people with disabilities, and which promote

full integration. These latter policies, although theoretical, would require a shift in the

default assumptions behind current care policies, and would require the greatest amount

of flexibility from care providers. However, these policies would hold the greatest benefit

for people with disabilities. The community-based care policies that currently exist make

up the middle of the spectrum, given that they allow for more community participation

that do institutions, but they still focus on providing for medical needs, rather than also

combating social barriers.

Independence Care Systems is a care coordinator in New York City that serves as a good

case-study for how an organization can simultaneously meet the medical needs of its

members, while helping them to integrate themselves into society. The organization goes

beyond the medically-focused services provided by Medicaid, and offers its members the

chance to live in and engage with communities. Furthermore, they work with service

providers to ensure that people with disabilities have access the same services as other

people do.

The ultimate, long-term goal of all policies should be to promote an integrated society in

which individual capabilities are equalized between disabled and non-disabled

individuals. Policymakers should consider such initiatives as:

Changing the assumed purpose of care to also consider the promotion of social

inclusion as part of its mandate

Increasing access to care coordinators

Providing support for family members who act as caretakers for individuals with

disabilities

Providing access to care coordinators for individuals with intellectual or

developmental disabilities

Increasing dialogue with disabled peoples organizations

Forming partnerships with care providers in order to promote socially-inclusive

practices

Promoting disability sensitivity training

Mainstreaming disability policy

Stienon, 4

Disability, Inclusion, and Care

Although several laws exist guaranteeing people with disabilities the right to be included

in society, the methods with which they are provided with long-term care continue to

perpetuate their segregation from the general population. This paper will discuss ways in

which policies can be used to care for the disabled while allowing for and encouraging

their full participation in society.

The Importance of Long-Term Care for the Disabled

According to the US Census Bureau, in 2010,

approximately 18.7 percent of the civilian, non-

institutionalized US population had a disability.

3

This constitutes a larger percentage of the

population than individuals over the age of 65,

even though the growth of the later group is more

often cited as a cause of rising healthcare costs.

4

Long-term care is expensive in and of itself, and it

constitutes 31.5 percent of Medicaids

expenditures nation-wide.

5

Nevertheless, although

people with disabilities often require similar

services to the elderly, they usually require greater

resources for a longer portion of their lives than

do other Medicaid recipients; in 2010, 42 percent,

or over $21 billion of New Yorks Medicaid

payments were made to people with disabilities,

whereas only 27 percent went to the elderly, and

19 percent went to other adults.

6

Furthermore,

given that disability prevalence increases with

age, the costs of disability care are likely to rise as

the Baby Boomer generation grows older.

7

If the

state government is to consider new ways in

which to reduce spending on healthcare, then it

must consider new strategies to provide care to its

disabled population.

8

S

Biault, !"#$%&'() +%,- .%)'/%0%,%#) 12324 567)#-608 9&6(6"%& :,',7).

4

Weinei, >-# ?08#$ @6<70',%6(4 1232.

S

Nina, "With Neuicaiu, Long-Teim Caie of Elueily Looms as a Rising Cost."

6

"Bistiibution of Neuicaiu Payments by Eniollment uioup, YF2u1u."

7

von Schiauei et al., .%)'/%0%,A B 9"<06A"#(, 1233 :,',7) C#<6$,.

8

"0thei Neuicaiu Beneficiaiies."

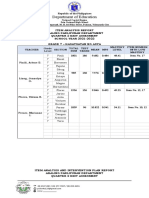

,-./01 +3 415-67-5 89:1;5-</01=> "++'

Souice3 Nina, "With Neuicaiu, Long-Teim Caie of

Elueily Looms as Rising Costs."

Stienon, S

People with disabilities face multiple barriers preventing them from participating in

society as easily as people without disabilities; People with disabilities are more likely to

be unemployed, more likely to earn lower wages, and more likely to live in poverty.

9

Disability in New York is also more prevalent among racial and ethnic minority groups,

as well as in less educated populations. This means that their concerns overlap with those

of many other underserved minority groups, and that care policies must consider ways to

consider the social barriers that these individuals would have to face regardless of their

disability, and must simultaneously serve the needs of these communities.

The demographics of disability are also changing, and new care policies will have to

reflect these shifts. There have been increasing efforts around the country to transition

people in need of long-term care, such as the developmentally disabled, out of institutions

and nursing homes, and back into their communities. However, it is unclear whether

communities have the resources necessary to provide these people with the constant care

services that they need.

Furthermore, over 25 percent of the primary caretakers of persons with developmental

disabilities, a large majority of whom still live with their family members, are over the

age of 65.

10

Given that modern medical advances make it increasingly likely that people

with disabilities will live past the age of 60, their current caretakers are unlikely to be

able to assist these disabled individuals throughout the full duration of their lives.

11

The

state must therefore simultaneously ensure that proper care is provided to those who are

exiting institutions, as well as to those who are living with family members who will no

longer be able to provide them with constant care. Furthermore, care providers will need

to increasingly focus on treating ailments that develop as individuals age, and that are

made more likely because of their previous disability; higher rates of survival must also

be matched with a better quality of life.

12

Nevertheless, it will not suffice to simply expand the existing care system, given that

adults with disabilities in New York State, are likely to report that their coverage is

inadequate.

13

The 2007 New York State Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

survey found that adults with disabilities are generally more likely than the rest of the

population to have chronic health conditions, more likely to have had not exercised the

previous month, more likely to rate their health status as fair or poor, less likely to get

9

Biault, !"#$%&'() +%,- .%)'/%0%,%#) 12324 567)#-608 9&6(6"%& :,',7).

1u

Bellei, "People with Intellectual anu Bevelopmental Bisabilities uiowing 0lu: An

0veiview."

11

Foi moie uetails about the costs - both monetaiy anu psychological - of being a

paient anu caietakei foi an auult chilu with an intellectual oi uevelopmental

uisability, see: Kiopf anu Kelly, "Stigmatizeu anu Peipetual Paients."

12

Bittles anu ulasson, "Clinical, Social, anu Ethical Implications of Changing Life

Expectancy in Bown Synuiome."

1S

Steele, D-'$,/66E 6( .%)'/%0%,A %( F#+ G6$E :,',#4 C#)70,) H$6" ,-# I#-';%6$'0 C%)E

='&,6$ :7$;#%00'(&# :A),#".

Stienon, 6

sufficient social and emotional support, and less likely to be satisfied with life.

14

Ultimately, the long-term care given to individuals with disabilities has large implications

on how easily they are able to live autonomously and independently, and therefore should

be seen as the foundation of how people with disabilities are integrated into society.

Stakeholders of Long-Term Care Policies

People with disabilities are the primary stakeholders in policies designed to provide them

with care. They are the group with the best understanding of their own needs, and will

have to rely on these policies to meet their medical needs, and to help them integrate

themselves into society. It should be noted that people with disabilities vary in their needs

and capabilities, and so they each favor a different combination of policies and care

options.

Caretakers and care providers are another important group to consider in these policies.

Those who were formerly employed in institutions tend to be opposed to the

deinstitutionalization movement, as are care providers who do not want to deal with the

extra costs of providing accessible services to the disabled. Managed care organizations,

on the other hand, are being contracted by Medicaid to help provide care services, and so

benefit directly from a shift to community-based care services. Similarly, care providers

with a more rights-based orientation are also more in favor of deinstitutionalization.

Families of people with disabilities, and especially of people with intellectual or

developmental disabilities, often take on the responsibility of providing care when

institutions are not available. They are interested in seeing adequate resources being

provided to communities, so that they do not suffer undue costs from this role.

Although discussions of disability polices are not often brought to the attention of the

general public, policies that promote social integration will indirectly affect everyone in

society, and might require that certain groups make accommodations in order to increase

accessibility for people with disabilities. While they will not engage in the debate of how

to design new policies, people in the public will oppose policies if they are poorly

managed, or if they force them to take on extra costs.

Defining Disability

Disability with respect to an individual is defined by the American Disabilities Act

(ADA) as a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major

life activities of such individual; record of such an impairment; or being regarded as

having such an impairment.

15

Beyond this strictly legal definition, however, there remain two main models that

14

Ibiu.

1S

!"#$%&'() +%,- .%)'/%0%,%#) !&, 6H 3JJ2.

Stienon, 7

contextualize disability, and demonstrate the different paradigms within which disability

policies are created.

The Medical Model

The medical model of disability defines disability as a problem located within an

individual that prevents them for leading a normal life. In effect, this model looks at an

individuals medically defined impairment be it any physical or mental loss of function

and attributes to it responsibility for this persons inability to participate fully in

society. People in a wheelchair are disabled because they cannot walk, and therefore

cannot climb steps, or reach certain spaces. The blind are disabled because they cannot

see, and therefore cannot read.

Policies based on the medical model focus on ways to either cure an individuals

impairment, or otherwise provide a treatment for their impairment. This approach implies

that, in order to participate in society, people with disabilities must be altered so that they

more closely resemble people who are deemed to be fully functional. Long-term care

policies based on this model are designed to effectively and efficiently meet the medical

needs of the disabled, and emphasize the provision of corrections (such as hearing aids),

mobility aids, assistive technology, and rehabilitation.

16

It should be noted that this has

been the predominant model throughout most of our history, and that opposition to this

model has only appeared recently.

The Social Model

The social model of disability defines disability as situation caused by exclusionary

societal barriers, which puts individuals with an impairment at a disadvantage. According

to this model, people are disabled because society does not accommodate their physical

or mental differences, causing them to be excluded from daily social activities. People in

wheelchairs are disabled because there are no ramps or elevators to allow them to reach

certain areas; the blind are disabled because texts are not provided in a Braille format.

Policies stemming from this model focus on the rights of people with disabilities to be

included as equals in society, and work to limit the social barriers facing the disabled. In

contrast to the medical model, disability is no longer seen as the intrinsic problem of the

individual, and it is a matter of social justice that social barriers be removed.

17

The Capabilities Framework

Although not a model that deals exclusively with disability, the capabilities framework

provides an alternative description complimentary to the social model of how

individual disadvantages stem from social or economic barriers.

18

According to this

framework, an individuals wellbeing should be measured using their capability to

participate in a range of activities, and inequality between people should be measured by

looking at when the environments around individuals limit their capabilities,

16

Lawson, "The E0 Rights Baseu Appioach to Bisability."

17

Buichaiut, "Capabilities anu Bisability," 7S2.

18

Ibiu., 7SS.

Stienon, 8

opportunities, or choices.

19

If we are to discuss disability using this framework, then we must assume that people

with disabilities should, in an ideal and perfectly equal society, have the same capabilities

or opportunities as non-disabled individuals. This does not mean that everyone should be

defined by their ability to partake in the same activities, but rather that people should

have the ability and freedom to engage in those that they wish to. Liberation from

disability is about having choices, not about living life in conformity to some pre-defined

notion of normality.

20

This framework is important in terms of disability policy because it defines equality

through peoples ability to participate in certain activities, without differentiating

between the different ways in which people participate. This means that three individuals

could be considered equally capable of communicating, even if one were speaking, the

second were using sign language, and the third using assistive technology; the end action

is all that matters. If we accept the social models premise that people are disabled by

societys inability to accommodate their impairments, then the capabilities framework

suggests that policies should focus on expanding the different ways in which people can

remain active in society, regardless of these impairments.

Intersecting the Models

Successful policies for providing long-term care to the disabled must take these models

into account, since each of them describe a different perspective of how the disabled are

excluded from society. The medical model recognizes that people with disabilities have

intrinsic medical needs that must be dealt with if they are to participate in society, and it

recognizes that there is much that science and technology can do to help individuals

overcome the limits of their impairments. However, the social model adds nuance to this

mindset, by explaining how social factors also limit people with disabilities, and how

policies can be used to mitigate these external barriers. Finally, the capabilities

framework provides a paradigm in which both of these models can work to increase the

capabilities of people with disabilities to engage with society.

Policy Trends of Long-Term Disability Care

The development of different models to describe disability has mirrored shifts in the

policies used to provide care to people with disabilities. If we look at the history of how

the United States and other Western countries have chosen to care for the disabled, we

can see four general trends in policy that allow for different balances between the

disability models.

Trend #1: Segregation and Institutionalization

People with disabilities were never highly regarded in society, and yet they were often

19

Ibiu., 7S9.

2u

Ibiu., 742.

Stienon, 9

allowed to contribute to the agricultural economy of pre-industrial Europe.

21

In 1601, the

British Poor Law began to push people who were unable to earn a living for themselves

into institutions a move which was exacerbated as the Industrial Revolution placed an

emphasis on a factory system wherein wages depended on a workers ability to complete

tasks in given amounts of time.

22

The disabled quickly got excluded from the labor force,

and were labeled as being the undeserving poor.

23

Meanwhile, the asylum movement

attempted to place people with mental health problems into therapeutic environments,

thereby segregating them from society.

24

By the eighteenth and nineteenth century,

people with disabilities were living within institutional settings, ranging from asylums,

hospitals, workhouses and prisons.

25

From the perspective of society, these institutions

were viewed as efficient ways to watch over and care for the disabled, while keeping

them out of the way from the general population.

Trend #2: Deinstitutionalization

A disability-rights movement began to emerge in the United States in the 1960s, and

began to push back against institutions. In tandem with the Civil Rights and womens

movement, the disability-rights movement advocated for the right to be allowed to live

with and participate in society. Institutions were increasingly seen as inhumane, and

conflicting with individuals right to autonomy over their lives. These arguments were

facilitated by advances in medical technology that allowed disabled individuals to receive

medical treatment in community settings.

Slowly, state and federal laws were changed to reflect these new expectations. With the

1981 Omnibus Reconciliation Act (OBRA), Congress allowed the federal government to

grant waivers to those using Medicaid who wish to receive home and community based

care; this marked an important shift in Medicaid policy, which had previously only

offered long-term services coverage for those entering institutional settings.

26

New York

State was unique in this regard, given that in 1977 it had already enacted its Long Term

Home Health Care Program (LTHHCP), after which the federal law was designed.

27

In

1999, the Supreme Court ruled in Olmstead v. LC that unnecessary institutionalization

violated the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), and therefore required that

states ensure that persons with disabilities receive services in the most integrated setting

appropriate to their needs.

28

Deinstitutionalization of the Mentally Ill

The dangers of poorly managed deinstitutionalization policies can clearly be seen in the

21

Nalhotia, "The Politics of the Bisability Rights Novement."

22

Picking, "Woiking in Paitneiship with Bisableu People: New Peispectives foi

Piofessionals Within the Social Nouel of Bisability," 11; Ibiu

2S

Nalhotia, "The Politics of the Bisability Rights Novement."

24

Picking, "Woiking in Paitneiship with Bisableu People," 12.

2S

Nalhotia, "The Politics of the Bisability Rights Novement."

26

"Neuicaiu Bome-anu-Community-Baseu Waivei Piogiams in New Yoik State -

New Yoik Bealth Access."

27

Ibiu.

28

"0lmsteau: Community Integiation foi Eveiyone."

Stienon, 1u

aftermath of the widespread closure of state institutions for the mentally ill.

The movement away from mental health institutions began as states funded small

community programs for individuals who could be treated by the new anti-psychotic

medications that were being developed.

29

In 1963, President Kennedy passed the

community mental health act, which aimed to build community-based mental health

centers that would allow people with mental illness to receive treatment while living at

home.

30

Similarly to the disability-rights groups, the mental health community argued

that deinstitutionalization would allow individuals to live higher quality and more

autonomous lives, and therefore welcomed this legislation. President Carters

Commission on Mental Health even lauded the "the objective of maintaining the greatest

degree of freedom, self-determination, autonomy, dignity, and integrity of body, mind,

and spirit for the individual while he or she participates in treatment or receives

services."

31

Unfortunately, even while there was a push to move people out of state public mental

hospitals, little was done to prepare communities to receive them. Only about half of the

community centers proposed under Kennedy were even built, and those that existed were

often understaffed and short on resources.

32

While certain individuals did experience the

increase in autonomy that the policy had promised, many others finding themselves

without access to their medications or medical services found themselves either

homeless, or, in the long run, in prisons.

33

Policymakers now have a greater understanding of how to properly design community-

based care programs, but the lessons learned from the mental health communitys

deinstitutionalization movement cannot be forgotten. Although community care might

promise to be more cost-effective for states, policymakers must still ensure that adequate

resource are provided to communities to meet the need of the people who live there, as

well as to make certain that these resources are easily accessible for those that need them.

Failure to do either of these things can result in individuals slipping through the cracks of

the system.

Deinstitutionalization in New York

New York State has been progressively deinstitutionalizing its long-term care for people

with disabilities, and under Governor Cuomo, is planning to transfer the remaining 1000

individuals with intellectual disabilities who remained in developmental centers as of

April 2013 into more integrated settings.

34

This decision follows a string of public

29

Koyanagi, K#'$(%(L H$6" 5%),6$A4 .#%(),%,7,%6('0%M',%6( 6H @#6<0# +%,- N#(,'0

O00(#)) ') @$#&7$)6$ ,6 K6(LP>#$" D'$# C#H6$", 1.

Su

"Community Nental Bealth Act: Kenneuy's vision Nevei Realizeu."

S1

"Beinstitutionalization: A Psychiatiic 'Titanic.'"

S2

"Community Nental Bealth Act: Kenneuy's vision Nevei Realizeu."

SS

Koyanagi, K#'$(%(L H$6" 5%),6$A4 .#%(),%,7,%6('0%M',%6( 6H @#6<0# +%,- N#(,'0

O00(#)) ') @$#&7$)6$ ,6 K6(LP>#$" D'$# C#H6$".

S4

Cuomo, C#<6$, '(8 C#&6""#(8',%6() 6H ,-# ?0"),#'8 D'/%(#,4 ! D6"<$#-#()%;#

@0'( H6$ :#$;%(L F#+ G6$E#$) +%,- .%)'/%0%,%#) %( ,-# N6), O(,#L$',#8 :#,,%(L.

Stienon, 11

criticism of the states treatment of the developmentally disabled, and of the widespread

abuse that existed across the system. The New York Times covered the debate in its

series Abused and Used, bringing the realities of the institutional system to the publics

attention.

35

The series described stories of accidental deaths in institutions, physical and

psychological abuse, lack of oversight, failed health inspections, and unqualified and

overworked staff, thereby increasing public pressure to revisit the management of the

system.

In the January of 2012, the Department of Health and Human Services issued a report

criticizing New York States oversight of care for the developmentally disabled, and

accusing the Commission on Quality Care and Advocacy for Persons with Disabilities

which was charged with this task for lacking independence from the governor, and for

breaking its obligations under federal law.

36

In June 2013, the Commission was

dissolved, and its responsibilities transferred to the New York State Justice Center for the

Protection of People with Special Needs.

Meanwhile, in November 2012, Governor Cuomo issued Executive Order Number 84 to

create the Olmstead Plan Development and Implementation Cabinet, with a mandate to

design policies to provide services to people with disabilities in the most integrated

settings possible.

37

Ultimately, New York State is moving away from institutionalization

as a solution for providing long-term care, and is instead choosing to promote home and

community based care.

Trend #3: Home and Community Based Care (HCBC)

As states move away from institutionalization, they are opting to provide HCBC to

people with disabilities, theoretically ensuring that medical needs are met while allowing

these individuals with greater autonomy and access to participate in society. These

policies have also become popular with states seeking to reduce the expenditures for

long-term care being spent on nursing homes and other institutions.

In order to prompt a transition towards HCBC, the Nursing Home Transition Program

was established from 1998 until 2000 to give grants to nursing home residents who

wished to relocate from institutions to community settings.

38

Similarly, the 2005 Deficit

Reduction Act included provisions to support state transition programs by expanding

home-based services and creating alternatives to nursing home placement.

39

This act

created the Money Follows the Person Program, which was designed to help individuals

SS

"Abuseu anu 0seu." http:www.nytimes.cominteiactivenyiegionabuseu-anu-

useu-seiies-page.html

S6

Bakim, "0.S. Repoit Ciiticizes New Yoik on Nonitoiing Caie of Bevelopmentally

Bisableu."

S7

Cuomo, C#<6$, '(8 C#&6""#(8',%6() 6H ,-# ?0"),#'8 D'/%(#,4 ! D6"<$#-#()%;#

@0'( H6$ :#$;%(L F#+ G6$E#$) +%,- .%)'/%0%,%#) %( ,-# N6), O(,#L$',#8 :#,,%(L.

S8

Fielus, Anueison, anu Babelko-Schoeny, "Reauy oi Not: Tiansitioning Fiom

Institutional Caie to Community Caie," 4.

S9

Ibiu.

Stienon, 12

funded by Medicaid transfer to HCBC while maintaining their Medicaid coverage.

As people move away from institutionalization, care can be provided in a variety of ways.

Many people with developmental disabilities are receiving care directly from their

families. Adult day services are also a possibility for caregivers who need assistance with

these constant responsibilities. A compromise between institutionalization and fully-

integrated community care are assisted living residences (ALR), which are housing

options that provide 24-hour on-site monitoring and care services in a home-like setting

for a group of five or more adults.

40

Finally, home health care services allow the disabled

to receive care services, depending on the needs of the individual, while living

independently at home.

Many states, including New York, are experimenting with managed care systems, in

which the state contracts out the task of providing care to community-based organizations

who are better able to meet the individual needs of their members.

Trend #4: Rights Based Policy

Although rights-based policies are more prevalent abroad than they are in the United

States, it is important to recognize their existence as a trend for long-term care provision.

These policies move beyond simply providing medical care to people with disabilities,

and instead attempt to use the process of providing HCBC to simultaneously combat

social barriers to disability.

In 2006, the United Nations passed the Convention on the Rights of Persons with

Disabilities (CRPD), which promotes the use of policy based on the rights-based social

model to help people with disabilities from around the world overcome the societal

barriers that prevent them from fully participating in their countrys progress and

development. This document, which has not yet been ratified by the United States, will

be the foundation for how the United Nations discusses disability in its post-2015

Agenda. The European Union has also begun to use rights-based policies in its regional

agreements and more specifically, its 2004-2010 Action Plan on disability, which

explicitly recognizes the validity of the social model, and which lays out a policy

framework that focuses on anti-discrimination, mainstreaming and accessibility.

41

A New Focus for Future Policy

Although the primary function of care policies is to ensure that the medical needs of

individuals are met, it is increasingly recognized that the method through which

individuals receive care plays a large role in how well they are integrated into society.

Therefore, when comparing alternative methods for providing long-term care for people

with disabilities, policymakers must consider how well they address the issues raised by

both models of disability, and how well they fulfill the following requirements:

4u

D6()7"#$ O(H6$"',%6( Q7%8#4 !))%),#8 K%;%(L C#)%8#(&#.

41

Lawson, "The E0 Rights Baseu Appioach to Bisability."

Stienon, 1S

Promoting Health

1. Meets the Medical Needs from Each Persons Impairment

As discussed in the medical model, policies that provide care for people with

disabilities must address any medical needs arising from an individuals

impairments. This would include treatments of impairments, as well as the

provision of corrective tools, assistive technology, mobility aids, rehabilitation, or

adaptations of a living environment. Ultimately, care policies should work to

increase a persons capabilities, regardless of their impairment, without

attempting to set a standard of what normal functions should look like.

2. Meets General Medical Needs

In addition to medical needs arising from impairments, people with disabilities

have the same basic health needs as people without disabilities. Therefore,

policies must ensure that they receive general healthcare coverage, and have

access to the same healthcare treatments that are recommended and provided to

individuals without disabilities.

3. Accessible Care

Accessibility has several meanings. Firstly, it assumes that people can physically

reach locations where services are provided with relative ease. Secondly, services

should be provided in ways that accommodate the physical or mental needs of

people with disabilities. Individuals should not be denied care because these

accommodations do not exist. For people with intellectual or developmental

disabilities, services should be available and constant, even if their guardians are

no longer able to monitor and provide them.

4. Affordable Care

Due to the high costs of their additional medical needs, people with disabilities

often need to spend more money to achieve the same living standard as someone

without a disability. Care policies should attempt to minimize the cost entailed in

providing services to people with disabilities, and individuals should not be

denied medical services because of the cost. Care services should also not come at

the expense of an individuals living standards.

5. Flexible Individualized Care

Policies should recognize the wide variation between people with disabilities

even between those with the same medical diagnosis and should allow

individuals to tailor their care services around the type of life that they would like

to live.

Promoting Social Integration

1. Promotes Autonomy and Independence

People with disabilities should have the ability to choose where and how they

live, without fearing a discrepancy in the services they receive, and they should

receive assistance to live their lives independently. This means that they should

Stienon, 14

not be required to depend on people who are unable or unwilling to ensure that

they receive proper care services. This is especially true for people with

developmental and intellectual disabilities, who continue to depend on their

family for long-term care.

2. Provides Opportunities to Engage with Society

People with disabilities should have the ability to engage in social activities of

their choice. This means that they should live in an environment where these

activities are accessible, and where they can reach transportation to go where they

wish. People with disabilities should have the capabilities to receive an education,

or enter the labor market, should they so wish. Their choices of what to do in life

should not affect the medical services they receive.

3. Promotes Respect

Care providers should treat people with disabilities in the same way, as they

would people without disabilities. Policies should recognize that people with

disabilities have the same desires in life as people without disabilities, and that

they should not be discriminated against because of their impairments. Policies

should seek to increase living standards.

4. Upholds Legal Rights of Persons with Disabilities

Policies should recall that laws already exist protecting the basic human rights of

people with disabilities, and should provide accountability measures to ensure that

these are upheld.

5. Safe Care

People with disabilities should be safe from abuse or exploitation.

Spectrum of Care

There exists a wide range of policy alternatives to provide long-term care for persons

with disabilities, which, for the sake of comparison, can be said to lie along a spectrum

based on how much each allows for integration in society. At one end of the spectrum

you have complete segregation, in which people with disabilities live apart from the

general population. At the other end of the spectrum, you have complete integration, in

which people with disabilities live within society, with equal capabilities as people

without disabilities.

Institutions and Nursing Homes Care Apart From Society

On one end of the spectrum, we find care policies in which people with disabilities live

apart from the general population in an institutionalized or nursing home setting.

The benefits of these policies stem largely from the medical model of disability. Within

these settings, it is easier to ensure that people with disabilities have access to the care

and medical services that they need for their daily activities, and to ensure that services

Stienon, 1S

are efficiently distributed between populations with similar needs. This is especially

useful for individuals who are unable to care for themselves, or for whom nobody else is

able or willing to provide care. Many of these homes do promote respect for those who

live within them, and allow them to participate in activities that they might not be able to

enjoy elsewhere.

These policies are problematic because they promote an inherent separation from society.

Institutionalization tends to emphasize medical benefits, at the expense of the more basic

rights of people with disabilities to actively participate in society. First of all, research has

shown that people who have lived in institutional settings have a very hard time learning

how to live independently once they leave again suggesting that people who enter these

homes will find it difficult to leave them, even if they should wish to do so.

42

Secondly, it

is difficult to ensure accountability in institutions, and history has shown that people with

disabilities who remain outside of the publics attention are vulnerable to abuse.

Although certain institutional settings might provide respectful and good quality care,

such standards cannot be ensured across the board. Finally, institutional care remains

expensive for state governments especially given that the federal government does help

cover the costs of individuals in state-run institutions and also because it removes most

possibilities for individuals to earn a living within the wider society.

Home and Community Based Care The System As We Are Now Building It

Moving along the spectrum, we find the myriad of different HCBC policies, which focus

on providing medical care to individuals with disabilities, while allowing them to live in

their homes or communities.

The value of these policies is that they allow people with disabilities to receive care in

more integrated settings in compliance with Olmstead while giving them a range of

choices on how much and what type of care they need to meet their medical needs.

People with disabilities who live in their communities have greater opportunities to

participate in the society around them.

Unfortunately, one of the biggest risks with HCBC is that communities can prove unable

to provide for the needs of people with disabilities, especially if policies are not put in

place to ensure that they have the necessary resources to provide care, and understanding

of how to use them effectively. Similarly, not all forms of HCBC ensure that people with

disabilities are able to integrate themselves in society, and all too often, they remain

segregated from social activities while living at home. This is in large part due to the fact

that current HCBC policies still focus predominantly on providing medical coverage to

the disabled, without considering what can be done to help these individuals expand their

capabilities.

42

Fielus, Anueison, anu Babelko-Schoeny, "Reauy oi Not: Tiansitioning Fiom

Institutional Caie to Community Caie," S-7.

Stienon, 16

Integration

The final end of the spectrum while still largely theoretical represents a set of care

policies that would allow individuals with disabilities to receive community-based care

that moves beyond providing for their medical needs, by including a mandate to help

them participate in society in the fullest way possible. This form of policy would be the

most beneficial to people with disabilities, in terms of ensuring that they are granted the

rights to fully engage with society.

This form of policy would be the most difficult to implement, as it would require

policymakers to reconsider the underlying purpose of care, and ask society in general to

shift its perception that its sole responsibility towards the disabled is the provision of

medical care. Furthermore, it would require care providers to remain flexible around the

needs of each individual a task that is difficult to accomplish in a large state

bureaucracy. On the other hand, an alternative integrated system that relies on smaller

managed care providers is difficult to coordinate or keep accountable.

Ultimately, it is towards this end of the spectrum to which we should be aiming. HCBC,

as we see it today, is a move in the right direct in relation to the alternative of

institutionalization, and yet the status quo continues to perpetuate segregated medical

systems and lifestyles for people with disabilities.

Case Study: Independence Care Systems

Independence Care System is dedicated to supporting adults with physical disabilities

and chronic conditions to live at home and participate fully in community life.

- Independence Care Systems Mission Statement

Independence Care Systems (ICS) is an important case study for how a community-based

organization that deals with long-term care for the disabled can simultaneously meet the

medical needs of its members, while helping them to integrate themselves into society.

ICS is a Medicaid-based disability care coordination organization in New York City that

bases its programs on three fundamental beliefs: that people with disabilities are capable

of taking a leading role in designing and managing their own healthcare and social

support; that people with disabilities deserve a services system that blends social support

with medical services; and that individuals with disabilities each have their own unique

needs and preferences.

43

As a disability care coordinator, ICS is a blend between a

managed care organization and a HCBC provider, and is characterized by offering

comprehensive psychological and social assessments of its members; self-directed

person-centered planning; support during health visits; a centralized medical-social

4S

Suipin, "Inuepenuence Caie System: A Bisability Caie Cooiuination 0iganization

in New Yoik City," SS.

Stienon, 17

record; engagement with community resources; and constant communication with

members.

44

Overall, they provide their members with access to a series of services and

programs several of which go above and beyond what is offered under Medicaid

programs and help them design a set of services tailored to their needs.

The organization was created in 2000 after its founders began recognizing flaws in

Medicaids fee-for-service programs, under which it is widely recognized that adults with

disabilities underutilize available services, and which is inflexible when it comes to

tailoring services to individual needs.

45

They found that the status quo failed to provide

adequate services to adults with disabilities in a multitudes of way, among them the fact

that primary care providers often lack training on how to deal with people with

disabilities, or that many preventative service providers, such as dentists, lack the

technology to make their services accessible to the disabled. The were also frustrated by

Medicaid regulations for rehabilitation that focus solely on restoring physical ability, and

will not reimburse maintenance therapy often required by people with physical

disabilities.

46

Moving beyond the basic medical services of Medicaid, ICS also works to help its

members actively engage with their communities. For example, they designed a

wheelchair repair service to ensure that their members remained unconstrained by a

breakdown in their primary means of transport, and they help their members select the

proper wheelchair for their choice of daily activities.

47

They also partner with home

health aide service providers to train new aides on how to go beyond acting as the

assistant to a person with a disability, and instead become the link between other care

providers, and the disabled person that they are assigned to assist.

48

ICS recognizes that its most successful initiatives have been to combine care

management with preferred provider relationships, in which they work directly with

service providers to design a set of services for their members.

49

For example, with its

new Womens Health Access Program, ICS worked with providers of breast cancer

screening and gynecological services to ensure that women with physical disabilities had

the ability to get the same general medical services as other women.

50

In creating this

program, ICS helped these service providers train their staff on disability sensitivity, and

ensured that they had the additional technology needed to give physically disabled

women these services.

Policymakers should look at ICS as an example of how care providers can use their role

44

Ibiu., S9-61.

4S

Ibiu., S4.

46

Ibiu., SS-S6.

47

Saviola, ICS Biookly Centei Toui.

48

Suipin, "Inuepenuence Caie System: A Bisability Caie Cooiuination 0iganization

in New Yoik City," S7.

49

Ibiu., 61.

Su

"Women's Bealth Access Piogiam."

Stienon, 18

to help individuals with disabilities actively participate in society. They are unique

because of the shift in focus in their mission statement and in their founding principles,

but their success towards their members proves that there is a demand for individualized,

socio-medial services that they provide.

Policy Recommendations

Future policies of long-term care for people with disabilities must continue to promote

HCBC and the ability for individuals to live in the least restrictive setting possible.

However, they must also move beyond the medical focus that continues to dominate the

implementation of current care policies, and instead use the provision of long-term care

as a means to help promote the inclusion of people with disabilities in society. The

ultimate, long-term goal of all policies should be to promote an integrated society in

which individual capabilities are equal between disabled and non-disabled individuals.

1. Changing the Purpose of Care

Policymakers must start by measuring the success of care providers based on their ability

to simultaneously provide for the medical needs of people with disabilities, while

providing them with the basic services and capabilities to help them engage with society.

Policies should be compared using measures that consider how well they promote both

the health and social inclusion of people with disabilities (see pg. 12). As long as care

policies are designed exclusively around the ideals of the medical model of disability,

then the social barriers around them will continue to keep them segregated from the rest

of society.

2. Increasing Access to Care Coordinators

ICS has proved to be able to link together the medical and social needs of its members

when designing new programs. Unfortunately, most existing care coordinators are for the

elderly, and not people with disabilities. Policymakers should either both provide support

to coordinators that already exist, and help in the creation of new organizations that could

fulfill this role.

3. Support for Family Caretakers

As the state closes institutions, families of people with disabilities are taking on the

burden of providing them care. Policymakers should provide assistance to these

caretakers either by allowing people to earn a wage from the state when taking on the

role of primary caretaker for a disabled family member, or by providing them with

assistance in the form of well-trained aides, or adult day care programs.

4. Care Coordinators for the Intellectually Disabled

Existing care coordinators only offer services to people with physical disabilities, and not

those with intellectual or developmental disabilities. Nevertheless, if individuals from this

later group are to live autonomously in society and not, as many now do, remain

dependent on family support then they will need assistance from well-trained

individuals who can help them navigate the long-term care bureaucracy, and design a set

Stienon, 19

of services to meet their needs. This service, which as of yet does not exist, would be of

incredible use to individuals who would like to remain in a community setting, but who

otherwise would not be able to take care themselves.

5. Cooperation with Disabled Peoples Organizations (DPOs)

People with disabilities are always the most knowledgeable about their own needs.

Organizations such as ICS are so successful in large part because they include people

with disabilities among their decision makers and staff. Policymakers should work with

these organizations when designing new care policies, and should remain available once

policies are implemented to receive feedback.

6. Partnerships with Care Providers

Many medical facilities are not equipped or welcoming to people with disabilities.

Policymakers should work directly in partnerships with care providers and medical

facilities in order to help them become more sensitive to the needs of people with

disabilities, and redesign their services in order to be accessible to the disabled.

7. Disability Sensitivity Training

Social barriers to the disabled exist outside of the realm of long-term care, and so

policymakers should promote disability sensitivity training for people working at all

levels of state programs.

8. Mainstreaming Disability

Social inclusion cannot occur by changing long-term care policies alone. Policymakers

must also consider ways of considering the needs of the disabled in all of their policy

decisions, and should continue to engage people with disabilities in discussions on ways

in which they could be better integrated.

Conclusion

As New York State shifts away from institutionalization, it is crucial that new policies to

provide long-term care for people with disabilities also be used as a tool to promote their

full social inclusion. A properly implemented care policy could act as the foundation that

would allows the disabled to engage with the rest of society as equals, by challenging the

assumptions from centuries of habits that state that the people with disabilities should be

fixed if they are to participate in society. Now is the time for social interactions with the

disabled that promote new habits of inclusion, accommodation, acceptance and respect.

Stienon, 2u

Bibliography

Abelson, Reeu. "A Chance to Pick Bospice, anu Still Bope to Live." >-# F#+ G6$E

>%"#), Febiuaiy 1u, 2uu7, sec. Business.

http:www.nytimes.com2uu7u21ubusiness1uhospice.html.

"Abuseu anu 0seu." The New Yoik Times. !/7)#8 '(8 R)#8, n.u.

http:www.nytimes.cominteiactivenyiegionabuseu-anu-useu-seiies-

page.html.

Ameiicans With Bisabilities Act of 199u, Pub. L. No. 1u1-SS6, 1u4 Stat. S28

(199u).

Bittles, A.B., anu E.}. ulasson. "Clinical, Social, anu Ethical Implications of Changing

Life Expectancy in Bown Synuiome." .#;#06<"#(,'0 N#8%&%(# B D-%08 F#7$606LA 46

(2uu4): 282-286.

Biault, Natthew. !"#$%&'() +%,- .%)'/%0%,%#) 12324 567)#-608 9&6(6"%& :,',7).

Cuiient Population Repoits. Washington, B.C.: 0.S. Census Buieau, }uly 2u12.

http:www.census.govpiou2u12pubsp7u-1S1.puf.

Buichaiut, Tania. "Capabilities anu Bisability: The Capabilities Fiamewoik anu the

Social Nouel of Bisability." .%)'/%0%,- B :6&%#,A 19, no. 7 (Becembei 2uu4):

72S-7S1. uoi:1u.1u8uu987S9u42uuu28421S.

"Community Nental Bealth Act: Kenneuy's vision Nevei Realizeu." !ID S F#+),

0ctobei 2u, 2u1S. http:www.wjla.comaiticles2u1S1ucommunity-

mental-health-act-kenneuy-s-vision-nevei-iealizeu-9S66S.html.

D6()7"#$ O(H6$"',%6( Q7%8#4 !))%),#8 K%;%(L C#)%8#(&#. New Yoik Bepaitment of

Bealth, n.u.

Cunningham, Petei, Kelly NcKenzie, anu Eiin Fiies Tayloi. "The Stiuggle to Pioviue

Community-Baseu Caie to Low-Income People with Seiious Nental Illness."

5#'0,- !HH'%$) 2S, no. S (2uu6): 694 - 7uS.

Cuomo, Anuiew N. C#<6$, '(8 C#&6""#(8',%6() 6H ,-# ?0"),#'8 D'/%(#,4 !

D6"<$#-#()%;# @0'( H6$ :#$;%(L F#+ G6$E#$) +%,- .%)'/%0%,%#) %( ,-# N6),

O(,#L$',#8 :#,,%(L, 0ctobei 2u1S.

"Beinstitutionalization: A Psychiatiic 'Titanic.'" =6(,0%(#, n.u.

https:www.pbs.oigwgbhpagesfiontlineshowsasylumsspecialexcei

pt.html#a8.

Stienon, 21

"Bistiibution of Neuicaiu Payments by Eniollment uioup, YF2u1u." The Beniy }.

Kaisei Family Founuation. >-# 5#($A TU V'%)#$ ='"%0A =67(8',%6(, 2u1u.

http:kff.oigmeuicaiustate-inuicatoipayments-by-eniollment-

gioup#table.

Eiickson, W., C. Lee, anu S. von Schiauei. .%)'/%0%,A :,',%),%&) H$6" ,-# 1233 !"#$%&'(

D6""7(%,A :7$;#A W!D:XU Ithaca, NY: Coinell 0niveisity Employment anu

Bisability Institute (EBI), n.u. www.uisabilitystatistics.oig.

Fielus, Noelle L., Keith A. Anueison, anu Bolly Babelko-Schoeny. "Reauy oi Not:

Tiansitioning Fiom Institutional Caie to Community Caie." T67$('0 6H

567)%(L H6$ ,-# 908#$0A 2S, no. S-17 (2u11): S-17.

Fischei, Pamela }., anu William R. Bieakey. "Bomelessness anu Nental Bealth: An

0veiview." O(,#$(',%6('0 T67$('0 6H N#(,'0 5#'0,- 14, no. 4 (198S): 6 - 41.

Bakim, Banny. "0.S. Repoit Ciiticizes New Yoik on Nonitoiing Caie of

Bevelopmentally Bisableu." >-# F#+ G6$E >%"#), }anuaiy 1u, 2u12.

Bellei, Tamai. "People with Intellectual anu Bevelopmental Bisabilities uiowing

0lu: An 0veiview." O"<'&, S2, no. 1 (Wintei 2u1u): 2-S.

Koyanagi, Chiis. K#'$(%(L H$6" 5%),6$A4 .#%(),%,7,%6('0%M',%6( 6H @#6<0# +%,- N#(,'0

O00(#)) ') @$#&7$)6$ ,6 K6(LP>#$" D'$# C#H6$". Kaisei Family Founuation, n.u.

Kiopf, Nancy P., anu Timothy B. Kelly. "Stigmatizeu anu Peipetual Paients: 0luei

Paients Caiing foi Auult Chiluien with Life-Long Bisabilities." :6&%'0 Y6$E

='&70,A @7/0%&',%6() no. Papei 7 (199S).

http:scholaiwoiks.gsu.euucgiviewcontent.cgi.aiticle=1u17&context=ss

w_facpub.

Lawson, Anna. "The E0 Rights Baseu Appioach to Bisability: Some Stiategies foi

Shaping an Inclusive Society" (n.u.).

Lawtheis, A.u., u.S. Piansky, L.E. Peteison, anu }.B. Bimmelstein. "Rethinking Quality

in the Context of Peisons with Bisability." O(,#$(',%6('0 T67$('0 H6$ Z7'0%,A

5#'0,- D'$# 1S, no. 4 (2uuS): 287 - 299.

Nalhotia, Ravi. "The Politics of the Bisability Rights Novement." F#+ @60%,%&) 8, no. S

(}uly 1, 2uu1): 81-1u1.

Nastei, Robeit }., anu Catheiine Eng. "Integiating Acute anu Long-Teim Caie foi

Bigh-Cost Populations." 5#'0,- !HH'%$) 2u, no. 6 (172 161AB): 2uu1.

Stienon, 22

"Neuicaiu Bome-anu-Community-Baseu Waivei Piogiams in New Yoik State - New

Yoik Bealth Access." Accesseu 0ctobei 4, 2u1S.

http:wnylc.comhealthentiy129.

Nina, Beinstein. "With Neuicaiu, Long-Teim Caie of Elueily Looms as a Rising Cost."

>-# F#+ G6$E >%"#). Septembei 6, 2u12.

"0lmsteau: Community Integiation foi Eveiyone." Accesseu 0ctobei 4, 2u1S.

http:www.aua.govolmsteau.

"0thei Neuicaiu Beneficiaiies." >-# F#+ G6$E >%"#). Septembei 6, 2u12.

http:www.nytimes.cominteiactive2u12u9u7usthe-othei-meuicaiu-

beneficiaiies.html.ief=policy.

"People Fiist Waivei: Questions anu Answeis." Accesseu 0ctobei 4, 2u1S.

http:www.opwuu.ny.govopwuu_seivices_suppoitspeople_fiist_waiveiq

uestions-anu-answeis.

Picking, Claie. "Woiking in Paitneiship with Bisableu People: New Peispectives foi

Piofessionals Within the Social Nouel of Bisability." In K'+[ C%L-,) '(8

.%)'/%0%,A, euiteu by }eiemy Coopei, 11-S2. Lonuon: }essica Kingsley, 2uuu.

Sauciei, Paul, }essica Kasten, Biian Buiwell, anu Lisa uolu. >-# Q$6+,- 6H N'('L#8

K6(LP>#$" :#$;%&#) '(8 :7<<6$,) WNK>::X @$6L$'")4 ! 1231 R<8',#. Centeis

foi Neuicaii & Neuicaiu Seivices (CNS), 2u12.

Saviola, Naiilyn E. ICS Biooklyn Centei Toui, 0ctobei 28, 2u1S.

Sen, Amaitya. .#;#06<"#(, ') =$##86". New Yoik: Anchoi Books, 1999.

Steele, Laiiy L. D-'$,/66E 6( .%)'/%0%,A %( F#+ G6$E :,',#4 C#)70,) H$6" ,-# I#-';%6$'0

C%)E ='&,6$ :7$;#%00'(&# :A),#". New Yoik Bepaitment of Bealth, 2uu7.

Steueinagel, Tiuuy. "Incieases in Iuentifieu Cases of Autism Spectium Bisoiueis:

Policy Implications." T67$('0 6H .%)'/%0%,A @60%&A :,78%#) 16, no. S (2uuS): 1S8

- 146.

Suipin, Rick. "Inuepenuence Caie System: A Bisability Caie Cooiuination

0iganization in New Yoik City." T !"/70',6$A D'$# N'('L# Su, no. 1 (2uu7):

S2-6S.

von Schiauei, Saiah, William Eiickson, Zafai Nazaiov, Thomas P. uoluen, anu Lais

vilhubei. .%)'/%0%,A B 9"<06A"#(, 1233 :,',7) C#<6$,. Coinell 0niveisity:

Employment anu Bisability Institute, 2u11.

Stienon, 2S

Weinei, Caiiie A. >-# ?08#$ @6<70',%6(4 1232. 2u1u Census Biiefs. 0S Census

Buieau, 2u1u.

"Women's Bealth Access Piogiam." O(8#<#(8#(&# D'$# :A),#"), n.u.

http:www.icsny.oigoui-caie-systemoui-specializeu-seiviceswomens-

health-piogiam.

Você também pode gostar

- ILMs 5 Asks For A Better Health and Social Care Integration August 2013Documento5 páginasILMs 5 Asks For A Better Health and Social Care Integration August 2013Priyadershi RakeshAinda não há avaliações

- Theoretical Model in Social Work PracticeDocumento4 páginasTheoretical Model in Social Work PracticeammumonuAinda não há avaliações

- Chcdis007 Facilitate The Empowerment of People With DisabilityDocumento19 páginasChcdis007 Facilitate The Empowerment of People With Disabilityamir abbasi83% (6)

- The Role of The Social Worker With Older PersonsDocumento15 páginasThe Role of The Social Worker With Older PersonsAaqibAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 5 Task 3Documento30 páginasUnit 5 Task 3Abigail Adjei A.HAinda não há avaliações

- Clinical & developmental models guide social workDocumento4 páginasClinical & developmental models guide social workammumonuAinda não há avaliações

- EXAM GPSGDocumento3 páginasEXAM GPSGPatricia GuerraAinda não há avaliações

- Collaborating To Support The Wellbeing of California S Seniors and Persons With Disabilities Through IntegrationDocumento34 páginasCollaborating To Support The Wellbeing of California S Seniors and Persons With Disabilities Through Integrationapi-79044486Ainda não há avaliações

- Providing Independent Living For Disabled People Social Work EssayDocumento3 páginasProviding Independent Living For Disabled People Social Work EssayHND Assignment HelpAinda não há avaliações

- EnglishDocumento22 páginasEnglishanshicaAinda não há avaliações

- Livelihoods Management Programme Finance CapsuleDocumento14 páginasLivelihoods Management Programme Finance CapsuleShoaib ShaikhAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter Eight: Principles, Objectives and General Ap-Proaches Relating To Community-Based RehabilitationDocumento5 páginasChapter Eight: Principles, Objectives and General Ap-Proaches Relating To Community-Based RehabilitationAnandhu GAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 1 SW 2206Documento5 páginasUnit 1 SW 2206Tebello Offney MabokaAinda não há avaliações

- Disability Jurisprudence - Jurisprudence II, Sem IVDocumento14 páginasDisability Jurisprudence - Jurisprudence II, Sem IVAbhay ChaudhuryAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 1 - (5) Social Justce & Social LegislationDocumento17 páginasUnit 1 - (5) Social Justce & Social Legislationriakumari2121Ainda não há avaliações

- Module 6 NRSG780Documento14 páginasModule 6 NRSG780justdoyourAinda não há avaliações

- Disability Work - FinalDocumento6 páginasDisability Work - FinalbabalolataiwotAinda não há avaliações

- Cle Esp 9 Quarter 3Documento15 páginasCle Esp 9 Quarter 3jonalyn obinaAinda não há avaliações

- Community AssessmentDocumento5 páginasCommunity Assessmentdenis edembaAinda não há avaliações

- Health Care Equity Tool Kit for Developing Winning PolicyDocumento25 páginasHealth Care Equity Tool Kit for Developing Winning PolicyDenden Alicias100% (1)

- Residual & Institutional ModelsDocumento6 páginasResidual & Institutional ModelsTendaiAinda não há avaliações

- Bolu Wife's WorkDocumento13 páginasBolu Wife's WorkOlorunoje Muhammed BolajiAinda não há avaliações

- When I'm 94Documento5 páginasWhen I'm 94IPPRAinda não há avaliações

- ETHICAL APPROACHES TO COMMUNITY HEALTHDocumento14 páginasETHICAL APPROACHES TO COMMUNITY HEALTHcamille nina jane navarroAinda não há avaliações

- Reflective JournalDocumento3 páginasReflective JournalArchi PrajapatiAinda não há avaliações

- Welfare ModelDocumento9 páginasWelfare ModelJananee Rajagopalan100% (4)

- Nas W Healthcare StandardsDocumento44 páginasNas W Healthcare StandardsAmira Abdul WahidAinda não há avaliações

- Community Health Nursing ProcessDocumento5 páginasCommunity Health Nursing ProcessAndee SalegonAinda não há avaliações

- BSWE-001/2019-20 Introduction To Social Work 1) Discuss Social Justice and Social Policy As Social Work Concepts. 20Documento13 páginasBSWE-001/2019-20 Introduction To Social Work 1) Discuss Social Justice and Social Policy As Social Work Concepts. 20ok okAinda não há avaliações

- Disability Task UpdatedDocumento6 páginasDisability Task Updatedimtiaz KhanAinda não há avaliações

- Sociology and Oral HealthDocumento27 páginasSociology and Oral HealthPrabhu Aypa100% (1)

- NDIS essay outlines support for vulnerable groupsDocumento5 páginasNDIS essay outlines support for vulnerable groupsBikash sharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Bioethics ReportDocumento8 páginasBioethics ReportIvy VenturaAinda não há avaliações

- Brief Summary of National Policy On Disability For Sri LankaDocumento8 páginasBrief Summary of National Policy On Disability For Sri LankaSivabalan Achchuthan100% (1)

- Care in Old Age in Southeast Asia and ChinaDocumento54 páginasCare in Old Age in Southeast Asia and ChinatassiahAinda não há avaliações

- ESC Module 6Documento19 páginasESC Module 6MHRED_UOLAinda não há avaliações

- LessonDocumento17 páginasLessonDenene GerzeyeAinda não há avaliações

- Dishant Tiwari-National And State Welfare Schemes And Policies For Senior Citizens- A Critical Analysis.Documento12 páginasDishant Tiwari-National And State Welfare Schemes And Policies For Senior Citizens- A Critical Analysis.joysoncgeorge2001Ainda não há avaliações

- Community Based RehabilitationDocumento11 páginasCommunity Based RehabilitationDebipriya Mistry75% (4)

- UcsptzyDocumento1 páginaUcsptzyGian Carlo Angelo PaduaAinda não há avaliações

- Empowering Persons With Physical Disabilities Healthcare Access and Support in Brgy. Libas Lavezares Northern SamarDocumento6 páginasEmpowering Persons With Physical Disabilities Healthcare Access and Support in Brgy. Libas Lavezares Northern SamarMatth N. ErejerAinda não há avaliações

- Characteristics, Needs, and Types of Social Work ClienteleDocumento47 páginasCharacteristics, Needs, and Types of Social Work ClientelesatomiAinda não há avaliações

- Community Diagnosis FPT - Chapter 1Documento19 páginasCommunity Diagnosis FPT - Chapter 1Katherine 'Chingboo' Leonico Laud100% (1)

- SWC14 Fields of Social Work ReviewerDocumento21 páginasSWC14 Fields of Social Work ReviewerJane D Vargas100% (1)

- Employee CoachingDocumento10 páginasEmployee CoachingDigantika MaityAinda não há avaliações

- Application of Principles of Sociology in Health CareDocumento85 páginasApplication of Principles of Sociology in Health Caresagar matada vidyaAinda não há avaliações

- DISABILITY AND DEVELOPMENT Robert Metts PDFDocumento45 páginasDISABILITY AND DEVELOPMENT Robert Metts PDFNafis Hasan khanAinda não há avaliações

- 1 Definition of Social Work PDFDocumento4 páginas1 Definition of Social Work PDFMireia HabboAinda não há avaliações

- English Counterarguments Final Paper AN20221204-889Documento6 páginasEnglish Counterarguments Final Paper AN20221204-889bdpmakhekhe5Ainda não há avaliações

- Domestic ViolenceDocumento10 páginasDomestic ViolenceShinsha SaleemAinda não há avaliações

- Application of Principles of Sociology in Health CareDocumento88 páginasApplication of Principles of Sociology in Health CareSagar matada vidyaAinda não há avaliações

- Flexibilise Care An Evaluation of Vision For Social Care 2010Documento6 páginasFlexibilise Care An Evaluation of Vision For Social Care 2010Malcolm PayneAinda não há avaliações

- Unit-Ii Psychology of DisabilityDocumento24 páginasUnit-Ii Psychology of DisabilityShubhashri AcharyaAinda não há avaliações

- The Impact of Community Care Policy On Older People in Britain. 1970s-1990s by Flourish Itulua-AbumereDocumento5 páginasThe Impact of Community Care Policy On Older People in Britain. 1970s-1990s by Flourish Itulua-AbumereFlourish Itulua-Abumere100% (3)

- A Proposal in Managing Homelessness in Society - EditedDocumento5 páginasA Proposal in Managing Homelessness in Society - EditedLeornard MukuruAinda não há avaliações

- Final DraftDocumento10 páginasFinal Draftapi-708917177Ainda não há avaliações

- Diass Week 8 ActivityDocumento2 páginasDiass Week 8 ActivityRv BlancoAinda não há avaliações

- 15 FACTSHEET Social Justice and HealthDocumento7 páginas15 FACTSHEET Social Justice and Healthjhean dabatosAinda não há avaliações

- Public Health Perspectives on Disability: Science, Social Justice, Ethics, and BeyondNo EverandPublic Health Perspectives on Disability: Science, Social Justice, Ethics, and BeyondAinda não há avaliações

- Nationalism in India - L1 - SST - Class - 10 - by - Ujjvala - MamDocumento22 páginasNationalism in India - L1 - SST - Class - 10 - by - Ujjvala - Mampriyanshu sharmaAinda não há avaliações

- How To Request New Charts in Navi Planner PDFDocumento7 páginasHow To Request New Charts in Navi Planner PDFМилен ДолапчиевAinda não há avaliações

- LCSD Use of Force PolicyDocumento4 páginasLCSD Use of Force PolicyWIS Digital News StaffAinda não há avaliações

- BIZ ADMIN INDUSTRIAL TRAINING REPORTDocumento14 páginasBIZ ADMIN INDUSTRIAL TRAINING REPORTghostbirdAinda não há avaliações

- FABM2 - Lesson 1Documento27 páginasFABM2 - Lesson 1wendell john mediana100% (1)

- DENR V DENR Region 12 EmployeesDocumento2 páginasDENR V DENR Region 12 EmployeesKara RichardsonAinda não há avaliações

- Cod 2023Documento1 páginaCod 2023honhon maeAinda não há avaliações

- Kursus Binaan Bangunan B-010: Struktur Yuran Latihan & Kemudahan AsramaDocumento4 páginasKursus Binaan Bangunan B-010: Struktur Yuran Latihan & Kemudahan AsramaAzman SyafriAinda não há avaliações

- Commercial Real Estate Case StudyDocumento2 páginasCommercial Real Estate Case StudyKirk SummaTime Henry100% (1)

- V32LN SpanishDocumento340 páginasV32LN SpanishEDDIN1960100% (4)

- NOMAC Health and Safety AcknowledgementDocumento3 páginasNOMAC Health and Safety AcknowledgementReynanAinda não há avaliações

- Ns Ow AMp GTB JFG BroDocumento9 páginasNs Ow AMp GTB JFG Broamit06sarkarAinda não há avaliações

- DPB50123 HR Case Study 1Documento7 páginasDPB50123 HR Case Study 1Muhd AzriAinda não há avaliações

- Uscca Armed Citizen SolutionDocumento34 páginasUscca Armed Citizen Solutionbambam42676030Ainda não há avaliações

- Lacson Vs Roque DigestDocumento1 páginaLacson Vs Roque DigestJestherin Baliton50% (2)

- Chem Office Enterprise 2006Documento402 páginasChem Office Enterprise 2006HalimatulJulkapliAinda não há avaliações

- Lc-2-5-Term ResultDocumento44 páginasLc-2-5-Term Resultnaveen balwanAinda não há avaliações

- 18th SCM New Points 1 JohxDocumento55 páginas18th SCM New Points 1 JohxAnujit Shweta KulshresthaAinda não há avaliações

- Tuanda vs. SandiganbayanDocumento2 páginasTuanda vs. SandiganbayanJelena SebastianAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment No 1. Pak 301Documento3 páginasAssignment No 1. Pak 301Muhammad KashifAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 3 Introduction To Taxation: Chapter Overview and ObjectivesDocumento34 páginasChapter 3 Introduction To Taxation: Chapter Overview and ObjectivesNoeme Lansang100% (1)

- The Elite and EugenicsDocumento16 páginasThe Elite and EugenicsTheDetailerAinda não há avaliações

- 15 09 Project-TimelineDocumento14 páginas15 09 Project-TimelineAULIA ANNAAinda não há avaliações

- Gorgeous Babe Skyy Black Enjoys Hardcore Outdoor Sex Big Black CockDocumento1 páginaGorgeous Babe Skyy Black Enjoys Hardcore Outdoor Sex Big Black CockLorena Sanchez 3Ainda não há avaliações

- The Revenue CycleDocumento8 páginasThe Revenue CycleLy LyAinda não há avaliações

- Item Analysis Repost Sy2022Documento4 páginasItem Analysis Repost Sy2022mjeduriaAinda não há avaliações

- Deuteronomy SBJT 18.3 Fall Complete v2Documento160 páginasDeuteronomy SBJT 18.3 Fall Complete v2James ShafferAinda não há avaliações

- Tanveer SethiDocumento13 páginasTanveer SethiRoshni SethiAinda não há avaliações

- Indian Air Force AFCAT Application Form: Personal InformationDocumento3 páginasIndian Air Force AFCAT Application Form: Personal InformationSagar SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Case Chapter 02Documento2 páginasCase Chapter 02Pandit PurnajuaraAinda não há avaliações