Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Consent Theory of Government 21

Enviado por

csandmDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Consent Theory of Government 21

Enviado por

csandmDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

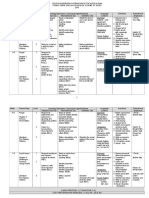

When I read articles, I alter the color of text and insert highlights to underscore portions of the text that

strike me as important, interesting, or confusing. I know that my inclination to colorize text is annoying to other readers, but it's important to the way I've come to think and analyze documents. More, I doubt that my various inserted comments would be as easily understood with my colorized highlights to indicate whichever words or phrases inspired my comments. I colorize text in red to indicate something that strikes me as significant and worth noting. I colorize text in pink to indicate something that I don't understand or disagree with. I add a yellow highlight to indicate something that strikes me as important. I add a green highlight to indicate something that strikes me as very important or even profound. I add a blue highlight to signify a subject that needs more research. The author s original text is in black. My own comments are inserted in a text that is [bracketed, bold and blue]. Alfred Adask ..............................................................................................................

POWER AND CONSENT REDUCTIONISM, DIALECTICS AND CONSENT THEORY

by DOUGLAS NEWDICK

[According to Wikipedia: Reductionism can mean either (a) an approach to understanding the nature of

complex things by reducing them to the interactions of their parts, or to simpler or more fundamental things or (b) a philosophical position that a complex system is nothing but the sum of its parts, and that an account of it can be reduced to accounts of individual constituents. I presume this definition corresponds to Mr. Newdick's use of the term reductionism.]

1.0 Introduction

Advocates of consent theory are aware that their theory is controversial to some degree and naturally enough this leads to a thorough defence of the theory in any exposition. This is not unusual. What is peculiar is the quality of that defence; the arguments that are countered are only those ones which offer the least challenge to the thesis. These advocates of consent theory defend their theory from counter-arguments that share the same fundamental presuppositions, ie objections from within the liberal democratic tradition, more radical criticisms are usually ignored or relegated to footnotes. While there is something to be said for not trying to defend one's theoretical basis all the time, much can be learned by defending particular explanations from criticisms based in different paradigms. In this essay I will explore some more radical arguments against consent theory than those it is usually defended from. Specifically I will attempt to show that the reductionistic and individualistic basis of consent theory is false and/or obscures more than it reveals and that a dialectical or non-reductionist picture can make sense of the problems that have persistently plagued consent theories.

2.0 Why Consent theory?

2.1 The basic appeal of consent theories of political obligation is that they are in harmony with the avowed ideals, aims and bases of liberal democratic theory. For a theory that places high value on freedom and the autonomous action of individuals the most obvious basis for legitimate political authority is some form of voluntary, self-assumed obligation. Consent theory fits the bill. More specifically, some consent theorists think that any other theory of political obligation is inconsistent with liberal democratic theory:liberalism assumes that normal adults have the capability for personal self-determination and that it is, therefore, appropriate to ascribe to them a right of personal self-determination. This right includes the right of political self-determination. From this it follows that no one can [impose] authority, including political authority, over any normal adult without the consent of those under such authority. (Beran, 1987, p 34) [But it's not consent every day, and every transaction, per say. There is one act of consent: a pledge of allegiance. Once that unilateral pledge is made, the pledgor is thereafter obligated to fullfill the terms of his pledge without further evidence of consent. That original pledge might be revoked by some formal procedure. But until that orignal pledge is revoked, the pledgor remains bound by his own pledge. In the case of government, I have repeatedly pledged allegiance to The United States of America. But I have never pledged allegiance to the United States. My single pledge of allegiance to The United States of

America expressed my consent to be bound by the laws of The United States of America. So long as my original pledge remains valid, no further consent to be bound by the laws of The United States of America should be required. Insofar as I have never pledged allegiance to any United States, I have never issued a blanket consent (pledge) to be bound by the laws of the United States. Therefore, if I'm approached by any agent of the United States attempting to subject me to the laws of the United States, they may require my consent to be so subject on a transaction-by-transaction basis. If so, an important addition to any line of defense might to 1) admit and declare my pledge of allegiance (consent) to be bound by the laws of The United States of America; 2) deny that I have ever pledge allegiance to the United States; and 3) declare that I have not consented to be bound by the laws of the United States in the particular transaction that is the subject matter of the case at hand. Under this analysis, once one had pledged allegiance to The United States of America, no further expression of consent to be bound by the laws of The United States of America would be required. So long as one had not pledge allegiance to the United States, blanket consent to the the laws of the United States could, at most, be presumed by the government of the United States--but that presumption could be refuted on a case-by-case basis. In theory, the cops' and/or courts' presumption that I've consented to be bound by the laws of the United States (this state) might be refuted by an an express declaration that I have pledged allegiance to The United States of America and that I have not pledged allegiance to United States. A similar declaration and denial might be devised relative to The State of Texas and this state. But the current Texas Pledge of Allegiance was adopted in A.D. 2001 and is almost certainly code for this state. The first Texas Pledge of Allegiance was adopted in A.D. 1933and even that is suspicious. I would not claim to made the government sanctioned Texas Pledge of Allegiance without some more research and consideration. I suspect that merely identifying myself as one of the people of The State of Texas might be sufficient to constitute my pledge of allegiance or at least my pledge to be bound by the laws of The State of Texas. One basis for presuming allegiance to this state may be the acceptance or use of the benefits of this state. i.e., if you pledge allegiance, you are entitled to the benefits of this state. If you accept the benefits of this state you might be presumed to have pledged allegiance to this state. But what happens if you take the benefits of this state and also deny allegiance to this state? Is that contradiction untenable? Must you return whatever benefits you've received in order to maintain your claim of no allegiance/consent? Or could you claim that you received the various advantages they claim to be be benefits as gifts and thus without attached liabilities? What if you claimed that you understood the alleged benefits of this state to be benefits (or gifts) of The United States of America?

(It's conceivable that an oath to support and defend the Constitution of the United States might be deemed a pledge of allegiance to that entity. But I doubt that any prosecutor or government employee would want to argue that point on the record.)]

2.2 Consent theorists appeal to consent to explain political obligation, because they think that the notion of political obligation is troublesome and highly contested, whereas the practice of promising giving rise to obligation is as uncontroversial a notion as one can hope to find. Therefore if we base our account of political obligation on consent, which is modeled on the practice of promising, [more probably, unilateral pledging] political obligation becomes non-problematic. Pitkin (1972, pp 74-75) argues that the reason consent theorists find political obligation troublesome and the practice of promising not so, springs from their liberal picture of human nature. Thus contractual theories of the state, including consent theories, flow naturally from the liberal conception of human nature or the state of nature. [The state of nature would arguably be subject to the laws of Nature and of Nature's God. Thus, the state of nature would be God's law. The liberal constructionmight be to give man the power to choose to be subject to some man-made laws other than the laws of Nature and Nature's God. Choose this day who you will serve: God or mammon. i.e., choose this day to whom you will pledge your servitude: Nature's God or mammon (civil law).]

[the liberal] picture of man in the abstract is of a man fully grown, complete with his own private needs, interests, feelings, desires, beliefs and values...Given man as such a separate, self-contained unit, it does indeed seem strange that he might have obligations not of his own choosing (ibid)1

2.3 Thus consent theory has strong ties with the methodology and ontology of reductionism and individualism, which are essential to liberalism.2 Reductionism is a methodology that attempts to give explanations of the properties of higher level entities, eg societies or cells, in terms of the units, eg individuals or molecules, of which they are composed. Reductionism is the thesis that parts are ontologically prior to the wholes that they make up, the parts and their properties exist before (either temporally or logically) the whole (Lewontin, et al, pp 5-6).3 Individualism is the manifestation of reductionism in the domain of politics and political philosophy. The properties of societies and states are to be explained by the properties of the individuals that make them up, and these individuals are ontologically prior to states and societies.

Consent theory is obviously an example of this methodology; a property of a complex whole, the state, is to be explained by properties, such as consent, of the units which make up the whole, ie individuals.4

3.0 Features of Consent Theory A consent theory of political obligation must have certain features if it is to be a plausible and consistent consent theory.

3.1 Firstly the theory must rely on actual consent rather than hypothetical [presumed] consent. An appeal to hypothetical consent as the basis for political obligation seems implausible. The intuitions that lead philosophers to consent theory (e.g. that political obligation must be self-assumed) are inconsistent with hypothetical consent. Hypothetical consent also requires some extremely implausible metaphysics or psychology. Instead of placing political obligation on an uncontroversial basis, hypothetical [presumed] consent derives it from a highly contentious one. [True. If the courts and/or system merely presume my consent, and they depend on that presumption, there will be contention over whether that consent is actual or hypothetical/presumed.]

3.2 A consent theory must make dissent possible. [That's axiomatic. If I have a right to consent, I must also have a right to not consent (dissent). This is the Achilles heel of any presumed consent: I have a right to refuse to consent.] If it comes out of a theory that all the people under a state's de facto authority have consented to a political obligation to that state, and there is no possible way of not consenting, we should be mighty suspicious. It would seem that in these cases we do not have consent, because consent is supposed to be the voluntary assumption of obligation and it seems odd to describe an action that it is impossible not to perform as being voluntary.

3.3 It should also be the case that political obligation is owed by an individual to the state if and only if that individual has consented. That is to say that it cannot be the case that individual X owes political obligation to the state in virtue of an action performed by individual Y, such as is the case in theories of original consent or majority consent. If this is not the case then we have abandoned one of the main reasons for choosing consent in the first

place, ie that political obligation be self-assumed.5 [By original consent I think the author is saying that even though the Founders consented to be bound by the laws of The United States of America, I am not also subsequently bound by their original consent. I, too, must somehow manifest my own consent in my own time and life. The issue of majority consent is less clear. What if 99% of the persons manifest their consent to be bound by the laws of this state? Is the other 1% necessary bound even if they don't consent? That probably depends on whether the 1% are also REGISTERED VOTERS. By registering to vote, you register to be one of the voters of this state. By registering to vote, you apparently register your consent to be bound by the decision of the majority of the voters of this state. That makes good sense to me. If I register to vote, and I vote with the majority, I expect the minority to be bound by the majority's vote. I implicitly expect that minority to consent to be bound by the will of the majority of the voters. Similarly, when I vote in the minority, it is nevertheless expected that I will consent to be bound by the will of the majority. One of the mechanisms by which I declare my membership in this state is by registering to vote. That's not news. But the possibility that, by registering to vote, I register my consent to be bound by the results of the elections is a new theory (at least to me). If I consent to be bound by the results of an election, I will also be at least presumed to be bound by whatever laws are passed by those who've been elected. So long as there's evidence that at least 51% of the people are registered to vote, the cops and judges can logically presume that anyone entering their court has registered to vote and therefore registered their consent to be bound by the laws of this state. I.e., so long as the system knows that over 50% of the people have expressed their consent to be bound by the laws of this state, it is more likely than not that any particular defendant has registered to vote. Therefore, the courts can reasonably presume that any particular defendant is probably a registered voter. Based on the reasonable presumption of voter registration, the court might also presume that the defendant has consented to be bound by the laws of this state. If this hypothesis were true, then it would follow that a man seeking to avoid the presumption that he had personally consented to be bound by the laws of this state would not only deny any pledge of allegiance to this state but would also expressly deny being a registered voter. Doing so might refute the presumption that he had consented to the laws of this state.]

3.4 A consent theorist should not assume that any or some states are legitimate, and build their theory upon

this assumption. To do this is to beg the question, because the point of the exercise is to see whether and to what extent existing states are legitimate.

3.5 Beran's (1987) membership version of consent theory appears to meet these conditions, and at the least comes closer to meeting them than any other consent theory I have encountered. Therefore I will use it as my model for purposes of discussion.

4.0 Problems for Consent Theory Traditionally there have been a family of related arguments that consent theories have had problems dealing with. They are all centrally concerned with the question: When does the form of consent not give rise to obligation? [The author may be asking if consent must be express or if it can also be presumed from mere conduct.] In Beran's language, what are the conditions that prevent consent from coming off?

4.1 In the most obvious and uncontroversial example, it is obvious that an action cannot count as consent if the consenter was threatened with physical violence if they did not comply. Similarly if you consent because I am likely (and able) to make life hell for you if you don't, then the consent does not "come off". [Consent cannot be compelled by force and/or involuntary.]

4.2 According to Beran (1987, p 6) "An attempt to promise [pledge?] comes off only if the attempted act is free, informed and competent." He then lists some defeating conditions that if present prevent a promise from coming off. The problematic examples come in here, firstly one might wonder whether these are all of the necessary conditions and secondly it is less than clear as to what counts as "free". [Similarly, what constitutes informed consent and competent consent ? Am I ever competent to waive my God-given, unalienable Rights? Does informed consent to be bound by the laws of this state require that I also know that that am waiving my rights and duties under The State and/or under the laws of Nature and Nature's God?]

4.3 A problem for consent theory is the case of the happy slave. We assume that a state that has the consent of its citizens is a legitimate political authority, yet what if the citizenry includes a class of slaves, and these slaves have apparently happily consented to be slaves? They have not been coerced into this position nor have they been coerced into consenting. Perhaps they have been brought up in the expectation of being slaves and are content with their lot. Is the fact of their consent (freely, fully informed and competently given) a sufficient condition for the legitimacy of their state? Many liberals (not to mention others) would like to say that it is not. How could consent theory deal with this problem?6

4.4 Beran (ibid) addresses criticism from Woozley, who argues that the high cost of emigration, both economic and personal, coupled with the likelihood that potential emigrants will have nowhere to go, makes people unfree to dissent, therefore the citizens are not consenting freely (quoted in ibid pp 95-108) [By high cost of emigration, the author argues that most of us are trapped in our particular country if only by the high cost of moving to another country. Thus, while some would say, If you don't like it here (consent to this state's laws), move to another country, the author recognizes that the high costs of emigration plus the political barriers to moving to another country force people to stay in their current country/jurisdiction. Thus, insofar as high costs prevent dissidents from leaving the country, the dissidents cannot be said to have consented to the country's laws simply because they remain resident in this state. Residency is compelled by the high costs of emigrating. Therefore, the presumed political implications of residency (being presumed to have consented to the laws of this state) might be challenged by expressly alleging that residency is compelled by the costs of relocating andbeing compelledcannot be presumed to be evidence of voluntary consent. Of course, other than enormous study, there is no cost (in the sense of transportation) in moving from this state back to The State. Nevertheless, I begin to see how residency in this state (as evidenced by the voluntary use of a Zip Code) could be deemed evidence that a person had voluntarily consented to enter into this state and thereby voluntarily consented to be bound by the laws of this state.]

Woozley's argument seems to take this form: 1. Consent must be free. 2. For an action to be free, one must be free to do X and free to do not-X. 3. The high cost of emigration means that one is not free to dissent. Therefore, 4. Membership does not count as consent. [True. But membership can justify the presumption that one has consented to be bound by the laws of this state. That presumption will stand unless it is expressly denied under oath and refuted with convincing evidence.]

Beran seems to be making two plausible replies to this argument, both involve a rejection of premise 2. Under one interpretation he is stating that for an action X to be free one merely needs to be free to do X, one does not need to be free to do not-X. Under another interpretation Beran's position is that freedom is not being prevented from satisfying one's desires. Thus if one does not desire to do X then being prevented from doing X does not make one unfree.7 Both of these replies are fraught with problems.

The first interpretation runs the risk of violating the constraint 3.2, but even if it does not there are other problems. The main point worth making here is that one should avoid conflating "free to choose X" with "choosing X freely". The first is compatible with a high degree of constraint, the second is not. The statement that "A is free to X" considers only A's relation to the action X, not to not-X or any other action. When talking about consent, we are interested in A's relation to other courses of action. The fact that consent is free in this sense is surely far less important than the fact that the citizens are unfree in respect to other actions. What becomes interesting then is the options which one is unfree to choose, why one is unfree to choose them and the source(s) of that unfreedom. [I suspect that the answer to this problem is that freedom to choose exists in layers. Once you make a blanket choice to be a voter, you may be subsequently unfree to choose to deny your consent to individual votes, individual politicians, and individuals laws. Once you choose to pledge your allegiance to one government, you become unfree to deny your consent to any of the laws or decisions of that government. By making one big choice to consent to the authority of one government, you become unfree to withhold or deny your consent to any of the multitude of that government's laws, regulations and policies. ]

With the second interpretation of Beran we run into the problem Berlin (1958) calls "the retreat to the inner citadel". If freedom is not having one's desires frustrated, then the best, surest, option is to reduce one's desires. [I'm not convinced that freedom can be defined as satisfying one's desires because one man's desires are often in conflict with the desires of other men. I may desire a Cadillac, but other men who make Cadillacs

may not desire to give me one. The fact that I desire but don't have a Cadillac is not proof that I am unfree. There are conditions prerequisite associated with the ownership of a Cadillac. You must earn a certain amount of money or have savings or credit sufficient to buy a Cadillac. You must be willing and able to spend that money to to buy the Cadillac. Thus, the freedom to own a Cadillac involves more than a mere desire--it involves the prelimary work required to buy a Cadillac. If you desire a Cadillac, you are not free to merely have onebut you are free to work, save and acquire enough money or credit to buy one. Freedom is not so simple as merely having a desire. Freedom can be far more complex. ] This is surely bizarre. Similarly, there are the problems of socialisation and/or brainwashing. We should say that someone who has been conditioned, whose desires have been tampered with (say by Skinnerian or Clockwork Orange style techniques), has had their freedom reduced, but we cannot if we identify freedom with the lack of frustration of desires. If we believe that such brainwashing interfere with freedom or consent, what are we to say about socialisation pressures that might bring about the same results?

5.0 Consent and Power

5.1 These problems are all getting at the same issue: How free does the act of consent have to be to count as an instance of consent? All commentators agree that if one is coerced into consenting by threat of sanctions, then the consent does not come off. These cases roughly follow this schema:

1. A wants B to do X. 2. A threatens B with harm unless B does X. 3. B does X because of the threat.

(Beran, 1987, p 100)

5.2 There is an interesting parallel here with the notion of power:

A causes B to do something that B would otherwise not do.

(Lukes, 1974) Therefore it is obvious that coercion is a case of the exercise of power (not surprisingly). Most of Beran's other defeating conditions (Beran, 1987, p 6) involve the successful exercise of power by someone over the consenter (eg "undue influence", "deception" (ibid)). We should note that in the cases that are problematic for Beran and other consent theorists (such as outlined in 4. above), it seems that what makes us unlikely to think that consent has come off is the exercise of power over the consenter. The question then becomes how prevalent is the exercise of power in society?

5.3 Lukes (1974) offers some analytical tools that might help us answer this question. His discussion of twodimensional power and three-dimensional power offer some insight as to how pervasive may be: is it not the...most insidious exercise of power to prevent people, to whatever degree, from having grievances by shaping their perceptions, cognitions, and preferences in such a way that they accept their role in the existing order of things...because they can see or imagine no alternative to it...? (Lukes, 1974, p 24) [Everyone is constantly trying to shape the perceptions of others. If I want a Cadillac, I do not necessarily agree to first price quoted by the seller. I barter as an attempt to persuade the seller to sell at a lower price; he barters as an attempt to persuade me to pay a higher price. We are both equally free to persuade each other to pay more or less. That persuasion frequently involves lying and deception. I might falsely claim I 'm too poor to afford the price asked by the seller. The seller might falsely claim that he has too much invested in the Cadillac to possibly sell at the price I've offered. The free market includes the freedom to lie. The freedom to lie includes the freedom to deceive and thereby shape the perceptions, cognitions, and preferences of others. But the freedom to lie does not include the obligation on the part of the hearer to be persuaded by the lie. The freedom to lie implies the correlative freedom and even duty to discover the truth. It's interesting that when we go to court and testify under oath, we consent to forfeit the freedom to lie. But when we are not under oath we are usually free to lie. There are exceptions. There are some laws that that compel telling the truth or allow the freedom to discover the truth.]

5.4 Herman and Chomsky (1988) give a concrete example of a structural arrangement that has these effects. They argue that the structure of the mass media in the USA results in a vast amount of political information never reaching the public, and a large number of political options are never presented to the public. Therefore the public are political actors who are largely acting from a position of ignorance.

5.5 Here I think the reductionism of liberalism defeats us because of its concentration upon the individual, and seeing consent as a property of the individual. The structural elements of power within which individuals make their decisions are invisible to individualism. Autonomy, freedom etc. are (reified) properties of individual agents, in the individualistic framework. However this ignores the power structures that constrain decision making (and belief/desire and knowledge formation) by agents. If the institutions of state and society are set up in such a way as to preclude certain options from ever being aired or taught in the public arena (as Herman and Chomsky (1988) have shown to be the case in the USA, at least), then those options are unavailable to the populace and we can no longer give an account of freedom or autonomy that looks to the individual alone.

6.0 Consent, Reductionism and Dialectics 6.1 In opposition to liberalism's reductionistic account of society, I think a dialectical account is inherently more plausible and gives a better understanding of the problems associated with consent theory. Reductionist explanation attempts to derive the properties of wholes from intrinsic properties of parts, properties that exist apart from and before the parts are assembled into complex structures...Dialectical explanations, on the contrary, do not abstract properties of parts in isolation from their associations in wholes but see the properties of parts as arising out of their associations. [Relationships? Fictions?] That is, according to the dialectical view, the properties of parts and wholes codetermine each other. (Lewontin, et al, 1984, p 11) [The reductionist explanation derives its force from the presumed independence of the individuals who combine into a society. Insofar as the dialectical explanations are based on the relationships (fictions) that exist between the component individuals, the dialectical force is based on dependence between the component individuals. ]

Therefore individuals and society codetermine each other in an ongoing process. [The society and

individuals are interdependent.] "The properties of individual human beings do not exist in isolation but arise as a consequence of social life, yet the nature of that social life is a consequence of our being human" (ibid).

6.2 Consent, as a behaviour, is an outcome of a dialectical process between individual and society. The process involves the wants, desires and beliefs of the individual, the power structures of society which restrict and shape their formation, and the power structures which restrict available options.

6.3 The liberal picture assumes that one can make a disjunctive list of the defeating conditions for promises, and that if none of the conditions on the list are present then the action is free. However as a three-dimensional account of power and/or a dialectic account shows, all such actions (decisions, promises, consent) are made within a power structure and are influenced by that structure. [But the fundamental consent is to be or not to be subject to a particular power structure. Once you manifest your fundamental consent to be subject to a particular power structure, you've waived or at least compromised all of your former freedoms to choose to be or not to be subject to the individual laws, rules, regulations, and policies of that power structure. The author's analysis of the dialectical explanation of consent does not appear to recognize a fundamental freedom to choose to consent or not consent to the power structure--it appears to treat any predominate power structure as something as innate and irresistible as gravity and not subject to one's consent. This analysis seems to see the earthly power structure as the fundamental and inescapable reality and thereby denies the existence of the Laws of Nature and Nature's God as primary. If the Laws of Nature and Nature's God do not exist, then there can't be an opportunity to choose to consent or not consent to the earthly power structure. I disagree with that analysis. More, it becomes increasingly clear that if there is a fundamental choice to be or not be subject to the earthly power structure (mammon), that choice presupposes the existence of God and the Laws of Nature and Nature's God. The fundamental choice is to consent to serve God or mammon. The option to choose to consent or not consent to the power structure is enshrined in the laws that guaranteed freedom of religion: The Declaration of Independence's unalienable Right to the pursuit of Happiness; the Constitution of the United States' 1 Amendment; Article 1.6 of the Constitution of the State of Texas.

st

It's not easy to escape the earthly power structure of mammon, but that escape may be possible by means of consenting to be subject to the Laws of Nature and Nature's God rather than consenting to be subject to the laws of the earthly power structure.]

6.4 Liberalism reifies consent, it is labelled as a unitary behaviour with a unitary cause. [To declare that liberalism reifies consent means that liberation gives consent some sort of tangible reality that it doesn't actually have. Thus, liberalism presumes that consent isn't real to begin with, but instead some sort of legal fiction. I believe that 'consent is innately real. If I'm wrong, freedom itself is merely an illusion. There can't be freedom without consent. If consent is not real, then neither is freedom. They can't call this the land of the free, they can't argue that we have freedom unless they admit that we have a right to consent or not consent to earthly government.] What a dialectic account shows us is that it is ridiculous to talk of a general cause of that behaviour, because the putative cause of that behaviour will depend upon where you look and your purposes in doing so. One's choosing X over Y is caused by the making of a decision, it could also be caused by someone obscuring option Z. Which of these causes gets called the cause of choosing X depends on one's viewpoint and one's purpose in searching for causes.8 A dialectic account sees consent as the result in an ongoing process. [The author appears to deny that behavior has a cause in the sense of a genuine choice. Instead, he seems to imply that consent is merely an appearance of individual choice that is actually the mechanical result of an ongoing process. If there is no individual cause for a particular act, then there is no individual responsibility for that act. If there is no individual choice/consent, then the whole idea of religion is false. If there is no individualism, there is no individual consent/choice, and we will not go to heaven or hell based on our acts and choices in this life because we are merely machines without a real capacity to choose/consent to be good or evil. Without individual choice there is no individual responsibility. ]

The consent of the happy slave and the consent of the brain-washed, can be seen as the result of a dialectic process where the power structures constrain and influence the decisions of the individual to an extreme. [The power structure itself is merely a collection of individual people. It is not a thing in itself so much as a kind of fiction that's useful for general discussions. The power structure is the label we affix to all the decisions we object to that are made by individuals who hold positions of power. Each of those individuals are not components of a machine so much as individuals who consent or do not consent to exercise some of their official powers in particular situations. What I'm trying to illustrate is that consent is even an element of each decision in the power structure. This presence of consent in the power structure is demonstrated by those instances when

government is expected to act in a particular way, but chooses not to. Individuals in government have denied their consent to be bound by the People's law (the Constitution) and instead consented to be bound by the laws of the New World Order or some other secular power structure. Consent is always present.]

6.5 From this discussion it can be seen that individualism is false or at least severely misleading. [I disagree.] A non-reductionistic, dialectical, account of society, power and consent is a more powerful and much more revealing way of looking at these issues. [I disagree.] Therefore the individualist consent theory can be seen to rest on a false presupposition. [I disagree with the premises of this argument. I disagree with the conclusion. The premises and conclusion sound like that of an atheist, satanist or Marxist.]

7.0 Conclusion

The consent theorists project fails because they do not realise the extent to which our decisions are influenced (or caused) by power structures, and because their reductionistic picture of the nature of society and the individual is false. If I am correct, then the entire liberal project of finding a basis or justification for legitimate political authority is untenable. The question then must be asked: Why do liberals attempt to derive authority in this way? [The liberals attempt to derive authority this way because they know from experience and history that consent is real and must be generally achieved in order for a society to function smoothly and efficiently. Once a significant percentage of the people withdraw their consent to be subject to a particular social-order/powerstructure, that society will at least destabilize and possibly disintegrate. This reality is born out in the Declaration of Independence which declares in part, That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it. The reductionist approach is not false and finding a basis of justification for legitimate political authority is not untenable but absolutely necessary. It may be that a particular basis for justification for legitimate political authority is itself false. For example, much political authority was gained and exercised by the events surrounding the attacks on Pearl Harbor or 9/11. Those events may have been portrayed in a false light. Nevertheless, the public generally accepted the official version of those events and therefore consented to allow the government to exercise new and expanded powers.

If public consent to go to war was not required, why did government bother with 9/11? Why didn't the power structure merely order all of its component machines get in line and start goose-stepping towards Iraq? The power structure cannot move without the consent of the people. The power structure would like to rule by pure fiat and without regard for public consent. It may be that those who comprise the power structure would prefer that the people are caused to forget their right and power of consent. The author's conclusion implies that individual consent and the existence of the Laws of Nature and Nature's God are all untenable fictions. As such, that conclusion would serve the interests of the power structure. I do not intend to serve the current, earthly power structure. I therefore reject the author's conclusion.]

BIBLIOGRAPHY Beran, H., 1987, The Consent Theory of Political Obligation, Croom Helm. Berlin, I., 1958, Two Concepts of Liberty, Oxford University Press. Cohen, G. A., 1979, "Capitalism, Freedom and the Proletariat" in Ryan, A. (ed.), The Idea of Freedom, Oxford University Press, Oxford. ----, 1988, History, Labour and Freedom, Clarendon Press, Oxford. Crosthwaite, J., 1987, "Feminist Criticisms of Liberalism", in Political Science, Vol 39(2). Greenawalt, K., 1987, "Promissory Obligation: The Theme of Social Contract", reprinted in Raz (1990). Herman, E., and Chomsky, N., 1988, Manufacturing Consent, Pantheon Books, New York. Herzog, D., 1989, Happy Slaves, University of Chicago Press. Hirschmann, N., 1989, "Freedom, Recognition, and Obligation: A Feminist Approach to Political Theory", in American Political Science Review, Vol 83(4). Horton, J., 1992, Political Obligation, Humanities Press International. Lewontin, R., et al, 1984, Not In Our Genes, Pantheon, New York. Lukes, S., 1973, Individualism, Basil Blackwell, Oxford. -----, 1974, Power: A Radical View, Macmillan Press.

Pitkin, H., 1972, "Obligation and Consent", in Laslett, P., et al, 1972, Philosophy, Politics and Society, Fourth Series, Basil Blackwell, Oxford. Raz, J. (ed), 1990, Authority, Basil Blackwell, Oxford. Simmons, A. J., 1979, Moral Principles and Political Obligations, Princeton University Press, Princeton. Wolff, R. P., 1976, In Defense of Anarchism, Harper & Row.

NOTES 1 Note also Greenawalt (1987, p 269): "social contract theory [including consent theory] is a reflection of a liberal conception of human nature that emphasizes freedom and autonomy." 2 A number of authors have argued this. See Crosthwaite (1987), Hirschmann (1989), Lukes (1973). Many Marxists regard reductionism and individualism as important components of bourgeois ideology, and they also regard liberalism as a manifestation of bourgeois ideology in the political/social domain. See, eg Lewontin, et al (1984), Cohen (1988). 3 Lewontin, et al, continue: "and there is a chain of causation that runs from the units to the whole." (ibid p 6) The discussion of reductionism is in the context of biology and psychology, but (and this is part of their point) could apply equally well to any part of bourgeois intellectual studies. With consent theory a "hypothetical" chain of causation runs from the individuals to society and the state (rather than a posited actual causation as in biological determinism) making the reductionist label even more accurate. 4 Similar to the case of biological determinism, consent theory involves the reification of certain behaviours of individuals, ie the behaviours are treated as objects located in the biology of individuals. Also the properties of the whole are also reified, such as authority. The fallacy in reification is in the assumption that if there is a term for a property, that property exists, or that what is measured exists. 5 See Simmons (1979:71). Note also Greenawalt (1987) "neither the unanimous agreement of those originally subject to the legal order nor the agreement of most of one's fellow citizens can obligate an individual who has not agreed." (p 275) 6 The consent theorist could of course Out Smart the objection by claiming that in this hypothetical case the happy slave has consented and the state is legitimate. They might add that, however, this hypothetical case is wildly implausible and thus is not a serious problem. 7 There is another response that Beran seems to make that relies upon a conflation of unfree with coerced. I regard this as highly implausible. 8 Compare the account of tuberculosis as caused by a bacillus, with the account of tuberculosis caused by

the appalling conditions of rampant capitalism. (Lewontin, et al, 1984)

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Five Ways To Handle A PresentmentDocumento9 páginasFive Ways To Handle A Presentmentmlo356Ainda não há avaliações

- Invisible Contracts PDFDocumento584 páginasInvisible Contracts PDFNETER432100% (16)

- Instructions For Discharging Public Debt With Private ChecksDocumento4 páginasInstructions For Discharging Public Debt With Private Checkssspikes93% (168)

- PC4900 Claim FormDocumento2 páginasPC4900 Claim FormcsandmAinda não há avaliações

- Oliver Wendell Holmes-The Common LawDocumento283 páginasOliver Wendell Holmes-The Common LawcsandmAinda não há avaliações

- Validity of AFV 2Documento24 páginasValidity of AFV 2csandmAinda não há avaliações

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Hippocrates - W.hs. Jones 2.ciltDocumento416 páginasHippocrates - W.hs. Jones 2.ciltmahmut sansalAinda não há avaliações

- Social Issues and Threats Affecting Filipino FamiliesDocumento24 páginasSocial Issues and Threats Affecting Filipino FamiliesKarlo Jayson AbilaAinda não há avaliações

- Grammar ComparisonAdjectives1 18823 PDFDocumento2 páginasGrammar ComparisonAdjectives1 18823 PDFmax guevaraAinda não há avaliações

- Unit III Chapter II Selection and Organization of ContentDocumento24 páginasUnit III Chapter II Selection and Organization of ContentOking Enofna50% (2)

- Love Is Fallacy Annotation PDFDocumento3 páginasLove Is Fallacy Annotation PDFJennyAinda não há avaliações

- Al MuhannadDocumento4 páginasAl Muhannadkang2010Ainda não há avaliações

- Frank Lloyd Wright On The Soviet UnionDocumento14 páginasFrank Lloyd Wright On The Soviet UnionJoey SmitheyAinda não há avaliações

- Literature - Marketing StrategyDocumento8 páginasLiterature - Marketing StrategyBadhon Khan0% (1)

- The Concept of GURU in Indian Philosophy, Its Interpretation in The Soul of The World' Concept in - The Alchemist - Paulo CoelhoDocumento8 páginasThe Concept of GURU in Indian Philosophy, Its Interpretation in The Soul of The World' Concept in - The Alchemist - Paulo Coelhon uma deviAinda não há avaliações

- p1 Visual Analysis HybridDocumento3 páginasp1 Visual Analysis Hybridapi-437844434Ainda não há avaliações

- Organizations As Obstacles To OrganizingDocumento31 páginasOrganizations As Obstacles To OrganizinghmarroAinda não há avaliações

- Gal-Dem Leeds Arts Uni SlidesDocumento37 páginasGal-Dem Leeds Arts Uni Slidesapi-330704138Ainda não há avaliações

- Daftar Nama Undangan AisyahDocumento8 páginasDaftar Nama Undangan AisyahroniridoAinda não há avaliações

- Mythic Ireland Mythic Ireland Mythic Ireland Mythic Ireland: John Briquelet John Briquelet John Briquelet John BriqueletDocumento30 páginasMythic Ireland Mythic Ireland Mythic Ireland Mythic Ireland: John Briquelet John Briquelet John Briquelet John Briqueletbz64m1100% (2)

- Studying Social Problems in The Twenty-First CenturyDocumento22 páginasStudying Social Problems in The Twenty-First CenturybobAinda não há avaliações

- How To Choose Your Life PartnerDocumento11 páginasHow To Choose Your Life PartnerAref Daneshzad100% (1)

- Trends M2Documento14 páginasTrends M2BUNTA, NASRAIDAAinda não há avaliações

- Michael Freeden - The Political Theory of Political Thinking - The Anatomy of A Practice-Oxford University Press (2013)Documento358 páginasMichael Freeden - The Political Theory of Political Thinking - The Anatomy of A Practice-Oxford University Press (2013)Mariano MonatAinda não há avaliações

- Felix Amante Senior High School: Division of San Pablo City San Pablo CityDocumento2 páginasFelix Amante Senior High School: Division of San Pablo City San Pablo CityKaye Ann CarelAinda não há avaliações

- Papademetriou - Performative Meaning of the Word παρρησία in Ancient Greek and in the Greek BibleDocumento26 páginasPapademetriou - Performative Meaning of the Word παρρησία in Ancient Greek and in the Greek BibleKernal StefanieAinda não há avaliações

- Equis Process Manual Annexes Jan 2012 FinalDocumento84 páginasEquis Process Manual Annexes Jan 2012 FinalVj ReddyAinda não há avaliações

- A Study On Learning and Competency Development of Employees at SRF LTDDocumento4 páginasA Study On Learning and Competency Development of Employees at SRF LTDLakshmiRengarajanAinda não há avaliações

- ILOG IBM CP Optimizer Webinar Slides PDFDocumento38 páginasILOG IBM CP Optimizer Webinar Slides PDFBrummerAinda não há avaliações

- Rhythm and Refrain PDFDocumento336 páginasRhythm and Refrain PDFtrademarcAinda não há avaliações

- Summary - LordshipDocumento3 páginasSummary - LordshipWisnu ArioAinda não há avaliações

- English Form 3 Scheme of Work 2016Documento8 páginasEnglish Form 3 Scheme of Work 2016jayavesovalingamAinda não há avaliações

- C. B. Muthamaa Case StudyDocumento9 páginasC. B. Muthamaa Case StudyNamrata AroraAinda não há avaliações

- Dna Mixture Interpretation: Effect of The Hypothesis On The Likelihood RatioDocumento4 páginasDna Mixture Interpretation: Effect of The Hypothesis On The Likelihood RatioIRJCS-INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH JOURNAL OF COMPUTER SCIENCEAinda não há avaliações

- St. Basil EssayDocumento13 páginasSt. Basil Essaykostastcm100% (1)

- Hegel and EmersonDocumento50 páginasHegel and EmersonNicoleta Florentina Ghencian67% (3)