Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Captives and Cousins - Slavery - Kinship - and Community in The Southwest Borderlands.

Enviado por

geogarikiDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Captives and Cousins - Slavery - Kinship - and Community in The Southwest Borderlands.

Enviado por

geogarikiDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Volume LX, Number 2

William and Mary Quarterly

Reviews of Books

Captives and Cousins: Slavery, Kinship, and Community in the Southwest Borderlands. By James F. Brooks. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, published for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 2002. Pp. xii, 419. $55.00 cloth, $22.50 paper.) Reviewed by Claudio Saunt, University of Georgia In Captives and Cousins, James F. Brooks paints a rich and detailed portrait of the "intercultural exchange network" (p. 363) that characterized the American Southwest in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries. The network tied together Navajos, Comanches, Kiowas, Apaches, Utes, Pueblos, and New Mexico colonists in a regional economy based on trade, theft, kinship, and slavery. The economy resists simple description and defies familiar categories of analysis, yet Brooks skillfully elucidates its complexities to recover the history of this enormous region of early America. Brooks traces the origins of this social network system to Iberian and Native American traditions of violence, exchange, honor, and shame. In several fundamental ways, he suggests, Iberian and Southwestern societies echoed each other: the reputations of both Spanish and native men rested on their ability to protect and control their families, and success depended on social interactions with other groups; conventions of honor and shame in both Spain and the Southwest dictated the tenor of relations between groups; and social interactions with outsiders created interdependency and produced unresolved tensions in the maintenance of stable cultural identities. The cross-cultural resonance described by Brooks, however, is tenuous; it is difficult to speculate about the existence in the precontact Southwest of culturally constructed categories such as honor and shame, let alone to determine if they functioned in the same way as they did in early modern Spain. Nevertheless, Brooks asserts that the parallels between indigenous and Iberian traditions meant that men from both sides of the Atlantic "negotiated interdependency and maintained honor by acknowledging the exchangeability of their women and children" (p. 40). Even if Brooks does not sufficiently substantiate that honor and shame shaped the actions of Spanish and native men in the colonial Southwest, it is clear that the political economy he describes drew on both Iberian and indigenous traditions of kinship slavery. Brooks's description of this borderlands economy is nuanced and sophisticated. It begins with an important insight: although anthropologists have long believed that war and gift exchange are opposite and mutually exclusive actions, slave-raiding and trade were both part of a larger system of exchange relations in the Southwest. "The capture of 'enemy' women and children," he writes, was "one extreme expression along a continuum of exchange" (p. 17). Slavery and slave-raiding were central to the political economy of the borderlands. Slaves contributed not solely the surplus labor needed to tend livestock, but also reproductive labor, a scarce resource in many small native and New Mexican settlements. Proscriptions against endogamy forced men to look beyond their communities, leading to "mutualistic or competitive patriarchal exchanges of women" (p. 365). When men married their female slaves, the line between slavery and kinship, captives and cousins, dissolved. Brooks recognizes that kinship slavery involved its own form of exploitation and coercion. Nevertheless, even if they were still in subordinate positions, when slaves became kin, they contributed to the growth of families and communities. Slavery also helped build regional trading networks. Slave raids and counter-raids encouraged the development of an active regional market, where slaves could be ransomed from their captors. Moreover, New Mexico and native captives could be found in nearly every community in the Southwest, and through adoption or marriage, they established kinship ties between their captors and their natal communities. Several captives themselves became important go-betweens, brokering relations between their new and old communities. This was a system built on paradox. Ties between 2003, by the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture

Volume LX, Number 2

William and Mary Quarterly

Reviews of Books

communities were sustained through slave-raiding, creating a larger regional economy, yet slaveraiding encouraged communities to retain their distinct identities. The numbers of slaves were small, especially compared to the Southeast. Among the Navajos, for example, the enslaved population numbered between 300 and 500 in the midnineteenth century, or at most 5 percent of the total population of 10,000. In wealthy communities, the proportion of slaves may have risen to as much as 38 percent of the residents. By contrast, it is estimated that between 1700 and 1880, roughly 5,000 native peoples entered New Mexican society as slaves. Despite these small numbers, Brooks writes, "the slave system of the Southwest Borderlands provided the ideological and cultural fuel that fed the larger economy" (p. 363). Brooks is unusually attentive to stratification both in New Mexico and native communities, and he notes that the theft of livestock (most often sheep and horses) and the abduction of people provided a means for disadvantaged communities, native and New Mexican, to increase their wealth. Although frequently opposed by wealthy New Mexicans and Indians, the poor established "communities of interest" (p. 164) dedicated to creating a political economy of the borderlands. Genzaros (detribalized Indians living in colonial settlements) and poor New Mexicans, for example, migrated onto the Plains in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, where they established hybrid communities that were neither fully colonial nor fully indigenous. They lived in farming settlements, like other colonists, but traveled seasonally to hunt buffalo or trade with Indians. Although these kinds of communities differed in their particular subsistence practices and settlement patterns, they all shared the custom of assimilating outsiders through adoption. After the United States invasion in 1846, the incorporation of the region into larger capitalist markets brought a gradual end to the Southwestern exchange network of captives and cousins. Particularly during the Civil War, the United States government made a concerted effort to sponsor capitalist development, in Brooks's words, "replacing kin-based subjectivity with state-sponsored individual autonomy" (p. 331). Navajos became not captors and captives but dependents of the United States, a transformation that culminated in the imprisonment of 9,000 Navajos at Bosque Redondo in 1864. As late as 1909, one Navajo headman still held thirty-two Ute slaves, but market forces had for the most part eroded traditions of slavery and kinship. Brooks's bold interpretation can be compared fruitfully to Alan Gallay's recent publication on slavery in the Southeast.1 The contrasts between bondage in the Southwest and Southeast are striking. In the American slave colonies, slavery was solely a form of labor exploitation. In New Mexico and surrounding native communities, by contrast, it was primarily a form of communitybuilding. As a consequence, slavery in the Southeast was premised on race in order to exploit the subject population more efficiently. In the Southwest, although slavery exacerbated gender and class inequalities, it never assumed the racial patterns of its Southeastern counterpart. For native peoples, these differences had tremendous consequences. Southeastern slavery may have temporarily enriched some Indian communities, but as the demand for captives rose, it destabilized the entire region. The dehumanization of non-Europeans ultimately allowed white colonists to justify the killing of Southeastern Indians and the appropriation of their lands. In the Southwest, the relative tolerance of intermarriage lasted well into the nineteenth century, although it was slowly undermined after white Americans seized the region and brought with them their obsessive fear of race-mixing. James Brooks's broad and ambitious interpretation of the Southwest is carefully argued in its details and is based on exhaustive research in Spanish-language archives. It is further bolstered by an impressive use of anthropology, especially the well-developed literature on African kinship slavery.

1

Gallay, The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 16701717 (New Haven, 2002). 2003, by the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture

Volume LX, Number 2

William and Mary Quarterly

Reviews of Books

Because Brooks refuses to simplify the complex political economy of the Southwest, his book makes for demanding and at times difficult reading, but his insights and overall argument make Captives and Cousins an innovative and truly important work. It will inform scholarship on early America and on borderlands regions for many years to come.

2003, by the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture

Você também pode gostar

- This Content Downloaded From 132.248.9.8 On Fri, 04 Nov 2 Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTCDocumento26 páginasThis Content Downloaded From 132.248.9.8 On Fri, 04 Nov 2 Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTCMonjoCraft 333Ainda não há avaliações

- Brooks' Captives & Cousins Shows Role of Slavery in Colonial SouthwestDocumento2 páginasBrooks' Captives & Cousins Shows Role of Slavery in Colonial SouthwestannavincenziAinda não há avaliações

- Review Essay Brooks and GutierrezDocumento4 páginasReview Essay Brooks and GutierrezAndrew S. TerrellAinda não há avaliações

- Ned BlackhawkDocumento8 páginasNed BlackhawkSergio CaniuqueoAinda não há avaliações

- Racial Divides in Early California CitiesDocumento11 páginasRacial Divides in Early California CitiesDevon CashAinda não há avaliações

- Nuestra América: Latino History As United States History: Vicki L. RuizDocumento18 páginasNuestra América: Latino History As United States History: Vicki L. RuizbauemmvssAinda não há avaliações

- A Fate Worse Than Death: Life EnslavedDocumento13 páginasA Fate Worse Than Death: Life EnslavedAndrew KnoxAinda não há avaliações

- Remaking Identity, Unmaking Nation: Historical Recovery and The Reconstruction of Community in in The Time of The Butterflies and The Farming of BonesDocumento21 páginasRemaking Identity, Unmaking Nation: Historical Recovery and The Reconstruction of Community in in The Time of The Butterflies and The Farming of BonesDante NiponAinda não há avaliações

- From Interethnic Alliances To The "Magical Negro" - Afro-Asian Interactions in Asian Latin American Literature Ignacio Lopez CalvoDocumento10 páginasFrom Interethnic Alliances To The "Magical Negro" - Afro-Asian Interactions in Asian Latin American Literature Ignacio Lopez CalvoAna María RamírezAinda não há avaliações

- The Other SlaveryDocumento6 páginasThe Other SlaveryTHEE OCHIENGSAinda não há avaliações

- The Colored Regulars in The United States Army by T. G. StewardDocumento219 páginasThe Colored Regulars in The United States Army by T. G. StewardRenato Rojas100% (1)

- Miki, Y. Fleeing Into SlaveryDocumento34 páginasMiki, Y. Fleeing Into SlaveryhardboiledjuiceAinda não há avaliações

- Emmanuel C. Eze Explores Origins of Double ConsciousnessDocumento23 páginasEmmanuel C. Eze Explores Origins of Double ConsciousnessGray FisherAinda não há avaliações

- Foundations of PopulismDocumento25 páginasFoundations of Populismapi-407869112Ainda não há avaliações

- Assignment On Slave ResistanceDocumento6 páginasAssignment On Slave ResistanceJanhavi ShahAinda não há avaliações

- Analysis of SlaveryDocumento15 páginasAnalysis of SlaveryChad WhiteheadAinda não há avaliações

- Racism & Capitalism: Chapter 4, Australia's Racist History - Iggy KimDocumento17 páginasRacism & Capitalism: Chapter 4, Australia's Racist History - Iggy KimIggy KimAinda não há avaliações

- Historical Context AbsalomDocumento2 páginasHistorical Context AbsalomGeanina PopescuAinda não há avaliações

- Transatlantic Voyage Student PaperDocumento5 páginasTransatlantic Voyage Student PaperMIKEAinda não há avaliações

- The Deepest South: The United States, Brazil, and the African Slave TradeNo EverandThe Deepest South: The United States, Brazil, and the African Slave TradeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1)

- FINALDocumento9 páginasFINALHerodAinda não há avaliações

- The Negro Park Question - Land Labor and Leisure in Pitt CountDocumento31 páginasThe Negro Park Question - Land Labor and Leisure in Pitt Countapi-726721693Ainda não há avaliações

- Sold Down the River: Slavery in the Lower Chattahoochee Valley of Alabama and GeorgiaNo EverandSold Down the River: Slavery in the Lower Chattahoochee Valley of Alabama and GeorgiaAinda não há avaliações

- Graubart CreolizationNewWorld 2009 PDFDocumento30 páginasGraubart CreolizationNewWorld 2009 PDFFrancois G. RichardAinda não há avaliações

- Zainab Amadahy and Bonita Lawrence PDFDocumento32 páginasZainab Amadahy and Bonita Lawrence PDFMike WilliamsAinda não há avaliações

- Final Honors 230 B PaperDocumento7 páginasFinal Honors 230 B Paperapi-301263457Ainda não há avaliações

- George Catlin's CreedDocumento8 páginasGeorge Catlin's CreedJOSEPH100% (1)

- IzabelmissagiaoxfordDocumento32 páginasIzabelmissagiaoxfordTeVê BêAinda não há avaliações

- L1839 GillespieDocumento31 páginasL1839 GillespieMaki65Ainda não há avaliações

- Final Old Soth Paper Hist 4505Documento11 páginasFinal Old Soth Paper Hist 4505api-330206944Ainda não há avaliações

- Patterson, Orlando. Slavery and Social Death. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1982. (P. Vii)Documento11 páginasPatterson, Orlando. Slavery and Social Death. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1982. (P. Vii)Kelvin HowellAinda não há avaliações

- Dossier LLCEDocumento2 páginasDossier LLCEneal.coursAinda não há avaliações

- Arabs and Jews in Mexican CinemaDocumento21 páginasArabs and Jews in Mexican CinematzvitalAinda não há avaliações

- Blues PeopleDocumento8 páginasBlues PeoplePepaSilvaAinda não há avaliações

- Native NarrativesDocumento10 páginasNative NarrativeskkrossenAinda não há avaliações

- Essay On "A Different Mirror" Bernadette HarrisDocumento15 páginasEssay On "A Different Mirror" Bernadette HarrisBernadette Harris, UNF & USF Sarasota-Manatee Graduate School100% (2)

- The Underground Railroad: Authentic Narratives and First-Hand AccountsNo EverandThe Underground Railroad: Authentic Narratives and First-Hand AccountsNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (10)

- In Search of Liberty: African American Internationalism in the Nineteenth-Century Atlantic WorldNo EverandIn Search of Liberty: African American Internationalism in the Nineteenth-Century Atlantic WorldAinda não há avaliações

- Fantasies of The Master Race - Ward ChurchillDocumento282 páginasFantasies of The Master Race - Ward ChurchillDiego100% (1)

- Literary Countercultures on Both Sides of the US-Mexico BorderDocumento28 páginasLiterary Countercultures on Both Sides of the US-Mexico BorderHéctor BravoAinda não há avaliações

- Skidmore - A Milder Type of Bondage Brazilian Slavery and Race Relations in The Eyes of American Abolitionists 1812 1888Documento23 páginasSkidmore - A Milder Type of Bondage Brazilian Slavery and Race Relations in The Eyes of American Abolitionists 1812 1888André GiamberardinoAinda não há avaliações

- Rashaunajohnson 2017Documento17 páginasRashaunajohnson 2017Flávia PenélopeAinda não há avaliações

- Review of The Middle Ground by Richard Write - Andrew GroundDocumento2 páginasReview of The Middle Ground by Richard Write - Andrew GroundAndrew “Castaway” GroundAinda não há avaliações

- 53 2marezDocumento42 páginas53 2marezCurtis MarezAinda não há avaliações

- The Web of Cis-Atlantic History - A Review of Louisiana - Crossroads of The Atlantic WorldDocumento5 páginasThe Web of Cis-Atlantic History - A Review of Louisiana - Crossroads of The Atlantic WorldjfbagnatoAinda não há avaliações

- WomeninSpancoloncontexts1-14Documento28 páginasWomeninSpancoloncontexts1-14Jomar Panimdim BalamanAinda não há avaliações

- Returns To A Native Land?Documento16 páginasReturns To A Native Land?driftinghouse100% (1)

- Blues PeopleDocumento8 páginasBlues PeopleDanilo SiqueiraAinda não há avaliações

- Racial History Surrounding The Lynchings in DuluthDocumento23 páginasRacial History Surrounding The Lynchings in DulutholocesAinda não há avaliações

- Afro-American Writing: Establishing Black IdentityDocumento32 páginasAfro-American Writing: Establishing Black IdentityHEMANTH KUMAR KAinda não há avaliações

- In Dig en As NogalesDocumento23 páginasIn Dig en As NogalesHectorMan Pim-FerAinda não há avaliações

- Frederick Jackson ThesisDocumento6 páginasFrederick Jackson Thesispbfbkxgld100% (2)

- Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World SlaveryNo EverandLaboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World SlaveryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (11)

- Jackson Yans McLaughlinDocumento70 páginasJackson Yans McLaughlinogunsegunAinda não há avaliações

- Remaking Identity, Unmaking NationDocumento21 páginasRemaking Identity, Unmaking Nationfouladouservice23Ainda não há avaliações

- American LiteratureDocumento7 páginasAmerican LiteraturevviiiooAinda não há avaliações

- Slavery Unseen Sex Power and Violence in Brazilian History-12-39Documento28 páginasSlavery Unseen Sex Power and Violence in Brazilian History-12-39Kattya MichelleAinda não há avaliações

- Embodied Economies: Diaspora and Transcultural Capital in Latinx Caribbean Fiction and TheaterNo EverandEmbodied Economies: Diaspora and Transcultural Capital in Latinx Caribbean Fiction and TheaterAinda não há avaliações

- (1828) Mexico in 1827 (Volume 2)Documento756 páginas(1828) Mexico in 1827 (Volume 2)Herbert Hillary Booker 2nd100% (1)

- Mexicoin 1827 - 01Documento643 páginasMexicoin 1827 - 01geogarikiAinda não há avaliações

- Ejas 7834 y Laberge On Samuel Trett S Fugitive Landscapes The Forgotten History of The Us Mexico BorderlandDocumento3 páginasEjas 7834 y Laberge On Samuel Trett S Fugitive Landscapes The Forgotten History of The Us Mexico BorderlandgeogarikiAinda não há avaliações

- Water: An Ocean of Opportunity 10 CommentsDocumento4 páginasWater: An Ocean of Opportunity 10 CommentsgeogarikiAinda não há avaliações

- Desert Magazine 1952 JanuaryDocumento44 páginasDesert Magazine 1952 Januarydm1937Ainda não há avaliações

- DesertMagazine 1972 JanuaryDocumento44 páginasDesertMagazine 1972 Januarydm1937Ainda não há avaliações

- Desert Magazine 1953 SeptemberDocumento44 páginasDesert Magazine 1953 Septemberdm1937100% (2)

- LARR. Tlacuitapa I Review. 2009Documento13 páginasLARR. Tlacuitapa I Review. 2009geogarikiAinda não há avaliações

- When in Some Upcountries DesalinationDocumento5 páginasWhen in Some Upcountries DesalinationgeogarikiAinda não há avaliações

- Seawater Desaalination in CaliforniaDocumento4 páginasSeawater Desaalination in CaliforniageogarikiAinda não há avaliações

- Desert Magazine 1955 FebruaryDocumento48 páginasDesert Magazine 1955 FebruarygeogarikiAinda não há avaliações

- Desert Magazine 1956 JanuaryDocumento48 páginasDesert Magazine 1956 Januarydm1937Ainda não há avaliações

- 0712 Water DesalinationDocumento9 páginas0712 Water DesalinationCenk SarıkayaAinda não há avaliações

- Desert Magazine 1953 AprilDocumento44 páginasDesert Magazine 1953 Aprildm1937100% (6)

- Desert Magazine 1953 MayDocumento44 páginasDesert Magazine 1953 MaygeogarikiAinda não há avaliações

- Desert Magazine 1957 JuneDocumento44 páginasDesert Magazine 1957 Junedm1937100% (1)

- Desert Magazine 1958 SeptemberDocumento44 páginasDesert Magazine 1958 SeptembergeogarikiAinda não há avaliações

- Desert Magazine 1956 MarchDocumento48 páginasDesert Magazine 1956 Marchdm1937Ainda não há avaliações

- Desert Magazine 1957 JulyDocumento44 páginasDesert Magazine 1957 JulygeogarikiAinda não há avaliações

- Desert Magazine 1962 JulyDocumento40 páginasDesert Magazine 1962 JulygeogarikiAinda não há avaliações

- DesertMagazine 1961 SeptemberDocumento44 páginasDesertMagazine 1961 SeptembergeogarikiAinda não há avaliações

- Desert Magazine 1960 AugustDocumento44 páginasDesert Magazine 1960 Augustdm1937100% (3)

- Desert Magazine 1966 AprilDocumento38 páginasDesert Magazine 1966 Aprildm1937100% (4)

- Desert Magazine 1962 OctoberDocumento40 páginasDesert Magazine 1962 OctobergeogarikiAinda não há avaliações

- Desert Magazine 1950 MayDocumento48 páginasDesert Magazine 1950 MaygeogarikiAinda não há avaliações

- Desert Magazine 1950 JulyDocumento48 páginasDesert Magazine 1950 JulygeogarikiAinda não há avaliações

- Desert Magazine 1950 NovemberDocumento48 páginasDesert Magazine 1950 NovembergeogarikiAinda não há avaliações

- Desert Magazine 1950 SeptemberDocumento48 páginasDesert Magazine 1950 SeptembergeogarikiAinda não há avaliações

- Desert Magazine 1949 JuneDocumento48 páginasDesert Magazine 1949 JunegeogarikiAinda não há avaliações

- Accounting Multiple Choice Questions & Answers: Answer: CDocumento2 páginasAccounting Multiple Choice Questions & Answers: Answer: CVemu SaiAinda não há avaliações

- Applied Economics 2nd Periodic ExamDocumento4 páginasApplied Economics 2nd Periodic ExamKrisha FernandezAinda não há avaliações

- European Central BankDocumento51 páginasEuropean Central BankJunwil TorreonAinda não há avaliações

- Anthony Downs An Economic Theory of Democracy Harper and Row 1957Documento321 páginasAnthony Downs An Economic Theory of Democracy Harper and Row 1957muhammad afitAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 1 Exam - The Nature of EconomicsDocumento7 páginasChapter 1 Exam - The Nature of Economicshameem mohdAinda não há avaliações

- 5 LCDocumento2 páginas5 LCArlynSarsabaMendozaAinda não há avaliações

- International Pepper Community: Report of The 36 Peppertech MeetingDocumento26 páginasInternational Pepper Community: Report of The 36 Peppertech MeetingV Lotus Hbk0% (1)

- Determinants of Unemployment in PakistanDocumento19 páginasDeterminants of Unemployment in PakistanBurare HassanAinda não há avaliações

- Postgraduate Courses in Economics and Econometrics 2014 PDFDocumento20 páginasPostgraduate Courses in Economics and Econometrics 2014 PDFFaculty of Business and Economics, Monash UniversityAinda não há avaliações

- Brand AuthenticityDocumento17 páginasBrand AuthenticitySuryaWigunaAinda não há avaliações

- Contemporary World. Module 1 4Documento23 páginasContemporary World. Module 1 4Abegail BlancoAinda não há avaliações

- BAS Vs BSSDocumento2 páginasBAS Vs BSSGunjan ShahAinda não há avaliações

- Nicolas Colin Hedge - A Greater Safety NetDocumento163 páginasNicolas Colin Hedge - A Greater Safety NetTudorCrețu100% (1)

- SEC Accredited Asset Valuer As of February 29 2016Documento1 páginaSEC Accredited Asset Valuer As of February 29 2016Gean Pearl IcaoAinda não há avaliações

- Multiple Choice: Full File at Https://testbankuniv - eu/International-Economics-12th-Edition-Salvatore-Test-BankDocumento9 páginasMultiple Choice: Full File at Https://testbankuniv - eu/International-Economics-12th-Edition-Salvatore-Test-BankalliAinda não há avaliações

- BiofuelsDocumento20 páginasBiofuelsapi-376049455Ainda não há avaliações

- Learnt About The Trade Policy of Belgium, Its Trade Relations With India and Dominating Trade Sector Between India-Belgium TradeDocumento19 páginasLearnt About The Trade Policy of Belgium, Its Trade Relations With India and Dominating Trade Sector Between India-Belgium Tradesailesh chaudharyAinda não há avaliações

- American Victory The Real Story of Todays AmwayDocumento244 páginasAmerican Victory The Real Story of Todays AmwayAutodidático Aulas100% (1)

- Lesson 3 App EcoDocumento63 páginasLesson 3 App EcoTricxie DaneAinda não há avaliações

- Transformation of Organization The Strategy of Change ManagementDocumento23 páginasTransformation of Organization The Strategy of Change ManagementMohamad Nurreza RachmanAinda não há avaliações

- BTD Golf TournamentDocumento4 páginasBTD Golf TournamentJordanAinda não há avaliações

- World's Top Leading Public Companies ListDocumento20 páginasWorld's Top Leading Public Companies ListbharatAinda não há avaliações

- Section e - QuestionsDocumento4 páginasSection e - QuestionsAhmed Raza MirAinda não há avaliações

- The Finance Sector Reforms in India Economics EssayDocumento4 páginasThe Finance Sector Reforms in India Economics EssaySumant AlagawadiAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 13 - GlobalizationDocumento37 páginasChapter 13 - GlobalizationbawardiaAinda não há avaliações

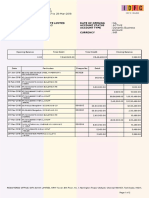

- IDFC Bank StatementDocumento2 páginasIDFC Bank StatementSURANA197367% (3)

- Role of Regional Rural BanksDocumento17 páginasRole of Regional Rural Banksvigneshkarthik23Ainda não há avaliações

- B E Billimoria Company Limited PDFDocumento1 páginaB E Billimoria Company Limited PDFmanishaAinda não há avaliações

- Design and Fabrication of Agricultural Waste Shredder MachineDocumento8 páginasDesign and Fabrication of Agricultural Waste Shredder MachineMahabub AlamAinda não há avaliações

- CV Khairul Dwiputro-2023Documento5 páginasCV Khairul Dwiputro-2023Rezki FahrezaAinda não há avaliações