Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Building A Hut - The Beginners' Guide PDF

Enviado por

Nelio CostaDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Building A Hut - The Beginners' Guide PDF

Enviado por

Nelio CostaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Building a hut the beginners guide

Keen to try your hand at building a hut from scratch? Experienced woodsman David Blair takes up a challenge to produce the ultimate how-to guide for beginners.

plan... then you can love it when the plan comes together. And work with others... a team is greater than the sum of its parts.

uilding with timber is not rocket science. Creating shelter is a simple, primal necessity demonstrated by children building dens at every opportunity. The same basic principles apply, whether you are building a hut, a home or a chicken coop. Give your hut a good hat, jacket and boots because it will be out there in all weathers! That means a completely waterproof roof covering that sheds water clear of the walls, external cladding that keeps out the rain, and foundations that keep the wood out of the mud and clear of splash. With good design, sitka can last longer than oak. It requires careful design and attention to detail, essentially avoiding anywhere that water can get trapped, particularly exposed end-grain wood. A mobile sawmill could cut all the timber for a modest hut in a day or so. Before you start building anything, have a good

Rules of thumb

1. Dont hit it with a hammer! 2. Measure twice, cut once 3. When building in Scotland, get it wind- and waterproof as soon as possible 4. There is more than one way to build a hut.

buildings work well with simple pad foundations allowing good airflow underneath and adapting easily to sloping sites. For small buildings like huts, paving slabs ideally the large, heavy duty ones (600x600mm) make good foundations and can often be reclaimed. For buildings no bigger than 4m in any dimension, a pad in each corner should be sufficient. Use a taut string line and pegs to mark out the external dimensions of the hut on the site. Do it carefully, checking the diagonal dimensions are equal. Once youre happy with it, lay a paving slab at each corner, leaving a 50mm gap to the string line. Using a spade, cut round all four edges of each slab. Lay the slabs aside and dig out a levelbottomed pad down to subsoil; if you are still in soft ground you can ram rocks into the earth. Use a bucket of sand for each pad, spread carefully and pack level. Lay the slab on top, protect it with a piece of wood and give it a gentle tamp down; check for level.

You will need

1. Hammer and nails (and/or screw gun and screws) 2. A crosscut saw 3. Spirit level 4. Tape measure and pencil 5. Staple gun and staples 6. Paving slabs, sawn timber, sheeting, membrane, windows and door 7. A plan 8. Patience!

Site selection and foundations

This page, top: The team working out a plan of action. Facing page: Erecting the wall panels. Photos: David Blair. p24 ISSUE 43

From the ground up, choose your site carefully, considering sun, wind, access, view and levelness. Timber

Reforesting Scotland

SPRING/SUMMER 2011

WOOdlAnd shelTer

Using a straight length of timber and a spirit level, work from the highest corner and set the four corners level by adding concrete blocks, bricks or pieces of broken slab. Lay a dampproof membrane on top of each foundation; then the foundation beams are laid on top, making sure they have 150mm clearance to the ground measure the distance between them and sight across them for parallel, adjusting the foundations if necessary. These beams are ideally fairly chunky, at least 150x100mm and preserved or durable, as they are closest to the ground. Nail a section of 150x25mm plank onto the ends to complete the foundation frame (A).

for 2.4m or less. The joists can then be cheek-nailed using 100mm nails (C). Nail a plank along the ends of all the joists, then pull the remaining breathable membrane tight onto the face of the plank and staple. Lay a temporary floor of sheet material or planks so you have a flat surface to build the wall panels on.

the outside of the whole frame and stapled on. Remember to start at the bottom so any overlaps keep the rain out and if insulating install, behind the sheet material before fitting the membrane. With Scotlands wet climate, get your building wind- and waterproof as soon as possible, giving you a dry space to work in.

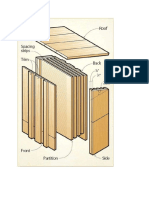

Creating the frame

Post and beam structures use substantial vertical posts and horizontal beams with diagonal triangulation to create a rigid structural frame. For huts and other small buildings, it may be easier to build lightweight timber frames, which rely on sheet material to give them rigidity (triangulation). These frames can be built flat on the floor (D) and then erected one by one and joined to create a rigid box with windows and door space built in (E). A timber frame consists of horizontal top and bottom rails with vertical sections (studs) between and intermediate horizontals (dwangs) and can be constructed from lengths of 100x50mm. In small buildings like huts, as long as there is a sheet of SterlingOSB or similar in each wall, the structure will be rigid; the remainder of the internal wall can be clad with sawn timber. Leave a 100mm space at the corner to receive the next wall panel by adding an extra stud (F). Once all four panels are erected, a breather membrane (Tyvek or similar) can be pulled tight around

Laying out the floor joists

A breathable membrane can be pulled tight and stapled across the foundation frame to stop draughts through the floor; this also creates a void for insulation. Staple along top surfaces and leave a metre of membrane beyond the foundation beams. Divide the length of the foundation beams by a whole number to get about 500-600mm between joists, mark out and set the floor joists, these should be long enough to cover the slabs. Insert an extra joist 25mm in from either end to support the wall frame and give a catch for the floor (B). Floor joists should be 150x50mm for a 4m span, but can be 100x50mm

ISSUE 43

Reforesting Scotland

SPRING/SUMMER 2011

p25

WOOdlAnd shelTer

Now for the roof

The simplest roof design is flat (all walls equal height). With a really good membrane a flat roof might work, but water drips off all edges and so its not really recommended. Next easiest is a single pitch roof where the roof deck is given about 15 degrees pitch across the building. The advantage is that all the water run-off is along a single edge and easily guttered clear of the building or collected. For a hut of 4m span or less, it can be achieved in a single span of 150x50mm at 600mm spacing; the roof joists should extend 150mm or more beyond the walls. Corrugated roof sheets (wiggly tin) are a simple and effective solution and are available in good lengths. It can often be reclaimed, but always use the same way up as previous. To avoid condensation dripping inside on frosty mornings, lay the roof joists with the pitch (G), cheek-nail them into the wall heads and fit dwangs between them along the wall heads, then stretch a breather membrane over the top and staple tight. Battens of 50x50mm can then be nailed perpendicular to the roof joists at 1m intervals onto which the roof sheets can be laid, making sure they extend beyond the walls by at least 150mm, and fixed with roofing nails. If you want a turf roof, you will need to keep the

p26 ISSUE 43

pitch shallow 15 degrees or less and will need to clad between the roof joists with 25mm thick boards or sheet material. If the surface is rough, lay an old carpet or underlay (checking carefully for tacks before laying the membrane). Use a good quality membrane (EPDM, Butyl Rubber or pond liner), spread another carefully checked carpet on top and then lay the turf at least 100mm thick; plant your spring bulbs in amongst it for a splash of extra colour.

vertical stud. Then counter battens are nailed horizontally at about 1m spacings through into each stud. The vertical cladding can then be nailed or screwed into the horizontal batons leaving a 50mm air space behind. The bottom edge of external timber cladding should be cut with a finetoothed saw with a back angle of about 20 degrees to create a drip edge (H) this can be achieved after the cladding is all fitted by scribing a line and cutting with a circular saw. When attaching cladding or decking, use

Laying the floor

If using sheet material for the floor, such as SterlingOSB or plywood, set the joists so that whole sheets meet on the centre of the joists (600mm between centres). If laying floorboards at 25mm thick, nail either side into each joist, make sure joins meet on joists and are staggered. If you are insulating, you will need to batten the membrane underneath and insulate between joists before laying the floor.

external-grade fixings and drive them carefully so the heads remain flush with the surface. So there you have it. Its dead easy, so go ahead and get building... you know you want to! David Blair is a Director of the Kilfinan Community Forest who lives and works at Dunbeag, www.dunbeag. org.uk, www.kilfinancommunityforest. com

Fitting the cladding

External cladding will last longer if it is allowed good airflow all round, so it can dry quickly when it gets wet. Double battening is recommended in which a vertical 50x25mm batten is first nailed onto the outside of each

Reforesting Scotland

SPRING/SUMMER 2011

WOOdlAnd shelTer

Inhabiting forests the rules and regulations

As more people gain access to woodlands, plantations and forests from individuals and small private groups and partnerships, to constituted community groups, big and small questions around building and living in the forest become more frequent. Here, Bernard Planterose and Peter Caunt look at the key legislation and regulations that currently affect such aspirations in Scotland.

aybe its quite a common dream the cabin in the woods. Perhaps its a subset of the bigger escape dream we all carry within us. Almost everyone who has ever owned, managed or even just spent a lot of time within a particular wood or forest has thought about building some form of cabin, whether to sleep over occasional nights or to escape forever into the sylvan dream. In areas of the world where the relationship with woodlands and their management is more intricate and ongoing, you will find cabin culture. Closest to us, it is particularly highly developed in Norway, Sweden and Finland, where cabins are a cultural expression of a certain closeness with nature or at least an aspiration to maintain that. Sweden has the biggest second home ownership in the world but these weekend or holiday homes (stuga) are most often very small to modest in size and serve to allow and encourage small-scale ownership and management of woodland. We dont have anything equivalent in Scotland... yet. Bothy remains a word redolent of meaning in our culture but is perhaps associated historically with itinerant farm workers and more recently with hillwalking and stalking. But a need is clearly growing for the woodland bothy, and a few pioneering individuals and community groups have already engaged in the process of making buildings to facilitate new relationships with the land and renewed forms of more intricate woodland management and habitation. In a country where timber cladding still meets with opposition from planning departments and trees

are required to be removed in the vicinity of buildings, it is perhaps not surprising that some have felt compelled to build beyond the legislation.

What the law says

So you are an occupier of a wood or part thereof, and you are carrying out woodland management or related activities on that land. You require some form of shed to perform a variety of functions including tool and equipment storage. What are the basic rules and regulations you need to be aware of? In the first place, it is important to understand that you must deal with both planning legislation and building standards, and that these present quite distinct sets of hurdles, even though they will most likely be administered from the same office at your Local Authority (LA). Note that this article only refers to Scotland and there are sometimes differences in interpretation of some rules and standards between different Local Authorities. Many of these have very helpful websites dealing with much or all of the points raised in this article, and may be the best starting point for anyone considering building anything in a woodland or forest. The main legislation to consult is the Town and Country Planning General Permitted Development (Scotland) Order 1992 (GPDO), Part 7 of which deals specifically with forestry buildings and operations. This planning legislation is currently under

ISSUE 43

A caravan treehouse, an ingenious solution to forest shelter. Photo: Jake Williams.

Reforesting Scotland

SPRING/SUMMER 2011

p27

WOOdlAnd shelTer

review, which is expected to result in some changes quite soon. Currently though, erecting, extending and altering a forestry-related building is a permitted work provided it is NOT (a) a dwelling and (b) within 25m of a public, metalled road. However a prior approval application has to be made to the LA planning department in order to verify that your proposal does not require planning permission. The LA may advise on colour or siting but can only refuse if they find reason to call in the application (i.e. where GPDO is deemed not to apply). So, in theory, any building in a woodland or forest other than a dwelling may be exempt from full planning permission and a wide variety of forestry-related building types are achieved legitimately under GPDO. But before you let your imagination go wild, building standards apply to almost all building types and this is where you will encounter most difficulties in constructing all but the simplest of unserviced sheds. There are a very small number of exemptions from Scottish building standards and these can be studied in section 0 of the Technical Guidance. Sadly, the more you look, the more you will discover that your options are very limited indeed. Schedule 1 of Regulation 3 defines the Exemptions to the Building (Scotland) Regulations Act 2004. No. 8 is the most important to forestry operations as it exempts singlestorey detached building(s) for all forestry related purposes up to an area of 280m2. Exceptions however are A dwelling, residential building, office, canteen or visitor centre. So this would preclude any form of sleeping accommodation though it doesnt specifically say it shouldnt be heated or serviced. But note all forms of waste systems are controlled by building regulations. No. 13 grants exemption to any detached and single storey building under 8m2 but NOT if it includes a fixed combustion appliance or sanitary facility. Does this leave room then for a very small bothy or not? Well, technically no, not if you are going to sleep in it because that would

p28 ISSUE 43

make it residential accommodation, which is an exception to the exemption. So, under this exemption you can build something at or under 8m2 that we might term a forestry day shelter, provided that it has no fixed heating or a toilet, either wet or dry. You could provide a portable gas heater or something powered by a portable electrical generator or solar panel, for instance. But thats about it. No wood-burning stove, no bed. Rather a bleak bothy. So, to

locations. Otherwise planning is required for a licensed caravan park and conditions will control numbers, landscaping, and opening times. The site will be run under licence issued by the local environmental health department and they will supply a set of rules covering densities, fire, refuse disposal etc. Crofters are allowed exemption for three caravans for summer lets and there is also exemption on land over 5 acres for a caravan to be sited for up to 28 days in any 12 month period. Of particular relevance, however, is Clause 8 in Schedule 1 which states that a site licence shall not be required for the use of land as a caravan site for the accommodation during a particular season of a person or persons employed on land in the same occupation, being land used for the purposes of forestry (including afforestation). Therefore, this would allow a mobile home to be parked up in woodland for some months at a time to facilitate a felling, coppicing or planting operation. There are British Standards determining how touring and static caravans are built, but the units themselves are exempt from planning or warrant. Anything meeting the criteria can be built on a park having permission, however planning conditions made in recent times attempt to control the nature of what is sited for example by stipulating wooden tents and not metal statics. Whether your mobile home is destined for seasonal occupation of a woodland under Clause 8 above or for a certified park, Standards require it to be not more than 60ft long, 20ft wide and 10ft high. It must be capable of arriving on site and being removed from site in one or two pieces. It is difficult to get anything wider than 12ft down the highway hence the popularity of two 10ft sections. This has allowed chalets with a low pitch roof to meet caravan legislation. Whilst wheeled bogies are used to get them onto the plot, these are removed, and other chalets are actually craned into place. Other British Standards ensure certain levels of insulation, dampness

the forest occupier, Exemption 13 doesnt actually offer anything that Exemption 8 doesnt offer. That is to say an equivalent building appears to be exempted up to 280m2, a grand bothy indeed but not a residential building, dont forget. There are exemptions for Buildings ancillary to houses (Types 17-19) but unless you happen to have an already existing house in your woodland then these exemptions are irrelevant to forest habitation. Before you either give up that snug bothy dream or decide to go down an illegal route, you should take a look at Exemption Type 12 A caravan or mobile home within the meaning of the Caravan Sites and Control of Development Act 1960, or a tent, van or shed within the meaning of section 73 of the Public Health (Scotland) Act 1897.

Keeping it mobile

The 1960 Caravan Act deals primarily with touring caravans, statics and residential park homes. A site for up to five tourers can be permitted by seeking the approval of an organisation like the Caravan Club. They ensure certain access, health and safety guidelines are met, and they make you one of their certified

Reforesting Scotland

SPRING/SUMMER 2011

WOOdlAnd shelTer

Facing page: A simple shelter for a variety of uses. Right: It can be difcult to get permission for simple accomodation in woodlands. Photos: David Blair and Karen Grant.

exclusion, escape provision etc. The mobile unit has to be tied down against uplift but foundations can be very cheap and simple. There is no limit on internal timber lining as is the case with housing, allowing more scope for woody interiors. It is assumed that waste arrangements are autonomous.

Implications for woodland life

So, in essence, the planning system allows for forestry-related sheds without much restriction on shape or form (but watch boundary restrictions), but building standards are only exempt for single storey buildings up to 280m2. In theory, these could be insulated to Passivhaus standards (requiring no space heating) or extensively glazed, but could NOT be used for sleeping or any form of residential occupation. If you require sanitary facilities of any kind a building warrant will be required, meaning youll need to embark on full drawings and specifications with all the cost that entails. Therefore, it may be best to build such facilities in a separate small building and submit this for warrant with your drainage proposals. As there is no residential type class in Scottish building standards other than house, there is no option for formal habitation but to follow the full planning and building warrant procedures. It is deeply regrettable that there is no scope for a less formal, less expensive, less materially and spatially extravagant form of living in Scotland than current dwelling standards encourage. In a global and even European context, this constraint appears anomalous and justifies challenge in our opinion. Informal forest living only appears possible with the invocation of the mobile homes legislation which has not in the past encouraged particularly environmentally sound forms of construction. There seems little option for would-be forest dwellers who do not want to live in a formal house to push the boundaries of this legislation inventively. There is an increasing volume of alternative, micro and extreme

It may be only a dream, but lets hope that someday building legislation will be sensitive to bio-regional differences within Scotland, facilitating both energy strategies and construction material choices appropriate to local climate and resources.

living literature available, and there must be many versions of the timber cabin on wheels yet to be devised. The folding-out caravan has already been pioneered and there is surely scope for a contemporary timber showmans caravan complete with wood burning stove and solar power. informal habitation patterns, along with modest scale and dependence on renewable energies and some local materials. This could help promote and reward off-grid strategies, genuine modesty of means and inventive use of locally sourced materials in construction none of which are currently promoted by either planning or building standards legislation. It may be only a dream, but lets hope that someday building legislation will be sensitive to bio-regional differences within Scotland, facilitating both energy strategies and construction material choices appropriate to local climate and resources. It might even differentiate between the material and spatial living requirements and aspirations of urban and suburban populations, and that of rural populations inhabiting a wide variety of managed natural environments who perhaps might be entrusted with the critical role of defining new and radical living relationships with a changing world. All legislation mentioned here may be searched and viewed on the website at www.legislation.gov.uk Bernard Planterose of NorthWoods Construction, based in Ullapool, specialises in timber design and build. Peter Caunt of Quercus Rural Building Design, based in the Borders, specialises in sustainable rural buildings with an emphasis on timber. Websites www.northwoodsdesign.co.uk and www.quercusrbd.co.uk

SPRING/SUMMER 2011 p29

What the future holds

The desire to inhabit our growing forests and develop new ways of economically and ecologically sustainable living with the land has been recognised to some extent by the Crofting Reform Act 2007 and the National Forest Land Scheme. However, neither of these specifically address the theme of how we might build more appropriately and economically using the immediately available forest resources and those that we are planning to develop. There is a real need to reduce the everincreasing material and cost burden of planning and building legislation that whilst responding to energy and climate change on the one hand simultaneously and ironically drives up scale and safety (and therefore costs and material demands) in a completely counter-productive trend. This deserves a more vocal critique. Perhaps Scotlands forest dwellers of the near future will be best placed to make this challenge, and to benefit from any changes that can be achieved. In the first place, a new building type class of bothy could be enacted within the building standards defined by changing and

ISSUE 43

Reforesting Scotland

WOOdlAnd shelTer

Instant huts

Timber is such a versatile material, it is an obvious choice for making shelters for forest dwellers, campers, bird watchers, rural workers and even horses. Here, architect Peter Caunt gives an overview of the ready-made huts on offer in Scotland.

n back gardens, in fields, on loch shores and not infrequently in woodland, prefabricated wooden shelters are becoming an ever more popular choice. These timber structures are manufactured, delivered whole or as a kit, erected with rudimentary foundations and, if you wish, completed for you. Your only responsibility is to pick up the tab. Or you need not even buy your own with glamping options on the rise in Scotland, you can settle into a camping hut just for the weekend.

lightweight studs, a similar floor and roof panels, typically with a mineral felt roof finish. Doors and fixed plastic glazing are included, though you should provide a foundation of paving slabs and the elbow grease to erect it. Cost from the likes of B&Q can be less than 100/m2.

The Horse Shelter

The Fishing Lodge

The Garden Shed

The ubiquitous garden shed is a kit formed with shiplap boarding on

Above: A Wolf Glen tipi. Right: Bird hide at Loch Leven. Facing page, left to right: Yurt skeleton; Pod and Wigwam camping huts. Photos: Peter Caunt and featured manufacturers. p30 ISSUE 43

What do you want in a hut by the river? If your bothy has a good aspect, then why not have a canopy covering your decked verandah? DIY interlocking plank chalets that cost around 350/m2 are available, and larger suppliers of summerhouses and cabins such as Forestcraft can add bespoke features. www.forestcraft.co.uk

Hardier breeds of horse can outwinter with a proper coat but nonetheless a roof over their heads and protection from the wind makes their lives a good deal more comfortable! With a steel ground frame, the double shelter purveyed by the likes of Redmire Stables from Sussex can be dragged around the field to the optimum location. There are many options, but typical construction will be

Reforesting Scotland

SPRING/SUMMER 2011

WOOdlAnd shelTer

corrugated felt roofing, treated timber studs with shiplap cladding and hardwood ply internal linings. Cost around 120/m2. www.redmire.co.uk

The Bird Hide

If you want to disguise your presence in the landscape, the birds are fooled at least by these ubiquitous structures. Gilleard Bros of Scunthorpe provide these to the likes of the RSPB in Scotland. Construction materials are the same as the horse shelter, indicating that they have done their homework in terms of driving down cost. Standard sections of imported softwood timber, when treated against rot, are difficult to beat. Cost around 250/m2, bespoke options using our own timber will cost a little more. www.bird-hides.co.uk

groundsheet make a comfortable floor, or for a more comfortable bed, sheepskin on a layer of reeds is a possibility. They are designed to take a central fireplace and the ridge smoke flaps and perimeter liner control the draughts and efficiency of the fire. Cost for a 6.4m diameter tipi is 90/ m2, or they are available for hire. www.wolfglentipis.co.uk

The Yurt

The Gypsy Caravan

You can tow a caravan into a wood and solve your accommodation problems in an instant. In the beginning there was a horse-drawn timber version, like the original 1930s Gypsy vardo now parked up and available for holiday let at the Roulotte Retreat near Melrose. www.canopyandstars.co.uk

Traditional yurt design is brought from Kyrgyzstan by the likes of Paul Millard of Red Kite Yurts in Stirlingshire. His yurts consist of steam-bent Scottish ash, oak, hazel, willow or maple and range from 2.4m to 9.1m in diameter. The lashed-together grid is structurally very efficient. Flame retardant canvas is used instead of felt and they are suitable for fitting a wood stove. Cost for 6m diameter is 6,350 or around 220/m2... or simply hire one. www.redkiteyurts.com

their valuables. The arch frame is 2.7m wide, in the standard model, and the special metal tiles provide wall and roof; there is sheep wool insulation behind the internal timber linings. Sleeping up to four folk, the french doors and wooden deck mean you remain in touch with your environment. The Pod is an attractive interloper that we will be seeing more of north of the Border. Cost to buy is around 600/m2, or book a break at one of five campsite locations in Scotland. www.thepoduk.co.uk

The Pod

The Tipi

By definition mobile and produced from natural products of cotton canvas and stripped pine, Wolf Glen Tipis by Johny Morris and Moy MacKay offer a magic shelter to drag into the woods. Rugs on a

The smallest camping huts can be usefully described as wooden tents, and The Pod by Newfoundland Lodges of Cumbria is a good example. Jude and Ian are finding a market where holiday sites can save people the trouble of pitching a tent, suffering the storm or worrying about

The Wigwam

Produced by Wigwam Cabins Ltd., this is a mobile wooden cabin in 2.7m or 3.4m widths. The larger sleeps three to five people and can

ISSUE 43

Reforesting Scotland

SPRING/SUMMER 2011

p31

WOOdlAnd shelTer

have light, a heater and a fridge. Since 2000, this building has been associated with Wigwam Holidays, which currently promotes 40 sites across the UK, from Shetland to Cornwall, with 23 of them in Scotland. Readers might be familiar with the owner of the company, Charles Gulland, who after a spell at Hooke Park in Devon, developed his ideas at Battleby with the Scottish Countryside Commission. His designs, developed over nearly 20 years, centre around a frame of freshly bent conifer poles and steam-bent larch, a cladding of feather-edged

Above left and right: The Hobbit; Pod Space home ofce. Below: Interior of the Armadilla. Photos courtesy of the manufacturers.

board from home-grown larch or Douglas fir, lined-over insulation and internal plasterboard finishing. Cost is 5,000 to 7,000 or around 400/m2 not including furnishings. Or book a break at one of 43 campsite locations around the UK. www.wigwamholidays.com

The Hobbit

A 2.4m diameter tube is the inspiration for this timber-clad shelter with a green ruberoid shingle roof. The 4.9m-long microlodge will sleep four and is built in Fife. It has all the facilities of a modern caravan with the exception of the loo, for which they have thoughtfully designed an outbuilding called the Wee Hobbit. Another outbuilding, the Hobbit Cascade, provides a shower. Perfect for glamping, they are coming to a site near you soon! Cost is around 850/m2. www.visionarymedia.co.uk

new office/studio is craned into your back garden. One such is Pod Space of Huddersfield, who are cheaper than a house extension due to simple foundations, factory prefabrication and the elimination of wet trades. The plan depth is 3.8m with typical lengths of 4.6, 5.6 or 6.8m, giving the areas within the permitted development ceilings. With a flat roof often covered in sedum, there are no height issues either, and Pod Space claims its super-insulation makes it highly energy efficient. Cost is around 1,000/m2. www.pod-space.co.uk

The Mobile Home

The Armadilla

This wooden tent is produced in Midlothian by Archie Hunter. A mobile building fully assembled from wood sourced in the Scottish Borders, its curvaceous shape is distinctly animal-like. The most popular size is 3m by 2.3m and will cost around 900/m2. www.armadilla.co.uk

The Home Office

A plethora of companies are in the market to help you realise dreams of working in a garden retreat; some are sophisticated turn-key operations where you only have to watch as a

p32 ISSUE 43

Heartland is one of a number of companies translating the caravan legislation (see page 27) into timber chalets that can be delivered in two parts, giving a building 6.1m wide by up to 18.3m long. At the bespoke design end of the market, the chalets are unique in being insulated for yearround occupancy, having underfloor heating, air source heat pumps, solar panels and untreated timber cladding. Because this is essentially a house, albeit a moveable one, the servicing is more complicated with water, electric and waste connections. These can be provided on any site, but for locations remote from the grid, viability may demand that several units share the expense. Cost is around 1333/m2. www.quercusrbd.co.uk

To conclude...

The recurring theme here is that there are plenty of mobile options, becoming more difficult to move as

Reforesting Scotland

SPRING/SUMMER 2011

WOOdlAnd shelTer

they get larger. Foundations can be very simple and the site returned to nature easily. Independent of size comes the question of quality and indeed sustainability. Using Scottish wood and more durable species is going to cost more than cheap imported and treated softwood. Using Scottish wool is going to cost more than fibreglass wool insulation. Having high performance windows and doors is going to save energy at higher first cost. To be mobile simplifies planning consent and building standards (see article about legislation on page 27) but if you are permitted or exempt, there is no third party to persuade you of the more sustainable, prettier but more costly option. The choice is yours, as is the moral responsibility that goes with it! Peter Caunt is an architect specialising in sustainable buildings and is based in the Scottish Borders. petercaunt@ lumison.co.uk

Bespoke mobile chalet by Heartland. Photo: Peter Caunt.

ISSUE 43

Reforesting Scotland

SPRING/SUMMER 2011

p33

ArTisT in wOOd

David Grant Round the world in a hut on wheels

Fi Martynoga meets a restless adventurer who, along with his family, spent seven years travelling the world in a wooden caravan.

orget visual artists, for this issue we are having a change! The most interesting and (appropriately) creative person I have come across in the last few months is a writer. He fits the bill for this issue dedicated to hutting because his first book describes the years he spent living in a hut with his entire family. It was a hut with a significant difference, as it had wheels and was drawn by a horse: a wooden caravan, in fact. From 1990 to 1997, David Grant and his family went round the world in it and he chronicled the journey in The Seven Year Hitch, an account of an extraordinary trip through Europe, Ukraine, Russia, Kazakstan, Mongolia, China, Japan and North America. The notion of a long journey was already with David when he spotted a magazine advertisement for Gypsy caravan holidays in Ireland. All thoughts of old buses were set aside as he began a process of trial and investigation into how a horse-drawn vehicle might serve them for the trek. From conception to approximate completion of the caravan took more than two years. At least in retrospect, David and his wife Kate saw this

as fortunate because it gave their children Torcuil, Eilidh and Fionn time to grow up a little. By the time they were ready to set off, they had reached the ripe ages of ten, nine and six respectively. Where did such restlessness spring from? Davids earlier career had never been dull or settled. He had already travelled the world, from the most remote of Scottish islands to Arctic Scandinavia, across most of the western Sahara Desert and to Australia. During that time he had worked as a jackaroo, a sheep-shearer, a fisherman, a member of a film crew, an expedition leader, an ecologist (his training he was taught at Edinburgh University by the famous Scottish ecologist James Lockie) and as a wildlife manager. Moreover, David had at one time kept his own horse, so when the family decided to set off, he was well-equipped to lead the expedition. The caravan, although modelled on a Gypsy vardo, was larger in floor area, as it was rectangular rather than bowed in towards the floor. The design was intended to yield as much space with as little weight as possible,

so the wooden walls and roof were of light construction. Initially, every person had a tiny personal space, achieved by several partitions. Quite quickly this layout was abandoned in favour of an open plan with canvas bunks for the children, as the individual spaces shrank the shared area too much. This meant that Davids writing space was the social one. He wrote his daily journal, the essential source of information for the book, right there, near the wood stove in winter, shoulder to shoulder with the others. The children would be playing board games or reading, and Kate working on something as he wrote. It was useful having them there, says David, They were able to remind me of the best bits of the day and to give me their own angle on events. Im a lazy writer, and it helped me to have this discipline of recording. The children saw to it that I made my entries almost every single day. The diary behind The Seven Year Hitch gives Davids writing a strong sense of time and place. The countries they passed through are presented as much by the human encounters as by

p34

ISSUE 43

Reforesting Scotland

SPRING/SUMMER 2011

ArTisT in wOOd

straight description. So many of the people they met showed themselves to be generous. Cautious requests for a field in which to turn loose Traceur, their French horse, frequently seemed to result in meals shared in farmhouses scattered through many countries. Even the poorest people in Ukraine and Mongolia appeared interested in the long-distance journey and proffered hay or potatoes or whatever they might be able to spare. This was fortunate indeed for the Grants, because they were making their trip on a very tight budget. And all was not plain sailing. The first potential breaking point was that Kate, who had felt in low spirits from the start in September, decided that she could no longer cope with feeling ill and claustrophobic in the caravan. She went home from Avignon station just before Christmas, only three months into the trip. Although she came back a few weeks later, she continued to be dogged by ill-health, and had to make repeated visits back to the UK. Not too long after she left for the first time, somewhere in Italy, Torcuil developed acute appendicitis and had to be rushed into hospital. Whilst he was there, Eilidh broke her ankle. Somehow, with the help of people they had only just met, David succoured all, and brought them back to the caravan to continue the journey. Worse travails were to greet them in Mongolia, giving David weeks of anxiety about a possible jail sentence. By good fortune (or timely negotiation!) it never happened, saving him from some sort of living hell. Mongolian jails have a very high death-rate.

Facing page: The caravan on a plain near Olgiy, Mongolia. This page: David and the children on the caravan in Italy; roadside home schooling. Photos: David Grant, Michele Cuttini.

All this is just to hint at the story. It takes you through all the difficulties of international borders, bureaucrats, vets certificates for the horses and dogs, winters setting in before rest quarters could be found, absence of stores, and all the literal hills to be climbed a real problem, even for a strong horse like Traceur. Yet the over-riding impression is not of drudgery but of excited engagement with people and places. It was probably the last moment we could have carried it off, says David. Bureaucracy and traffic have both got much worse since then. It seems like a different world. We first set eyes on mobile phones in the hands of the Chinese security police in 1995. And email only became available when we were halfway across the United States the next year. Its difficult to grasp the changes that have happened since. The Grants finally achieved Nova Scotia, always the intended destination, in October 1997, 2,570 days and 12,360 miles after they had started. From there they flew back to Scotland and set up home in Angus, from which Fionn finally went to school. When assessed for entry, the school pronounced him the best we have ever had. Just two years later, David was on the move again. The new expedition was a solo voyage in a folding kayak with a small sail. He travelled from the Baltic to the Black Sea, using the river and canal systems, following one of the less well-known of the routes used by Viking traders and mercenaries. Spirit of the Vikings charts new forms of hardship and fresh struggles with bureaucrats. On this journey he was greatly helped by Bahai communities along the way, for during the troubled

times he had experienced in Mongolia with the caravan, David had become a member of the Bahai Faith. In Latvia, Belarus and Ukraine, he was able to bring greetings and some good publicity to Bahai groups. In return he benefited from their immense hospitality and the wonderful way in which they were so often able to find free entry for him at lock gates, and smooth his passage from one country to another. David, now a singleton in his cottage high in the Angus hills, suspects he may end up living in the caravan again. If times get as hard as it appears they may, I could be reduced to that, even though the cottage itself is not much more than a shed. But it does have room for books. Storing them was always a problem in the caravan. Our only permanent volumes and main educational resource for the children was the World Book Encyclopaedia. Most other books had to be passed on as soon as they were read. There simply was no space for them to accumulate. For all their unorthodox education, those children are now practical, selfassured young people, either studying or with jobs. The seven-year family odyssey seems to have shaped them well, and David himself has no regrets about the experience. Copies of The Seven Year Hitch (7.99 plus p&p) and Spirit of the Vikings (14 plus p&p) by David Renwick Grant can be obtained from the author at david@renwickgrant.com or No 2 Balintore Cottage, Balintore, Kirriemuir, Angus, DD8 5JS Fi Martynoga is a freelance museum researcher and writer from the Scottish Borders.

ISSUE 43

Reforesting Scotland

SPRING/SUMMER 2011

p35

LETTER FROM ABROAD

A day in the life of a Finnish summer house

The sauna by the lake. Photo: Tuula Pardoe.

Finnish-born Tuula Pardoe reflects on the long summer holidays of her childhood, spent at the familys forest cabin with nature as a playground.

by the lake swimming, fishing for perch with hook and worms, and exploring by rowing boat. We made play-animals by pushing four twigs into the green bulbous seed-heads of yellow water-lilies and into pine cones. We collected baby frogs for pets. Large stone boulders scattered in the forest by the receding Ice Age became our fortresses and homes for roleplay; we pretended to cook plants and other forest materials. We played sports games, treasure hunts and hideand-seek. A large chest of old dresses and lengths of material were put to use for dressing up. We collected blueberries to eat with the pancakes our mum made. For wet-weather pastimes, we competed against each other in gymnastics, drew clothes for paper dolls, played with and made clothes for Barbie dolls, read books, played board games, drew and painted. During the day my father would carry enough water from the lake to fill up a large water-heater in the sauna (pictured above right). In the evening he then heated the sauna stove and the water-heater ready for bathing. We warmed ourselves in the sauna and swam in the lake, alternating the two for the best part of an hour. Late in the evenings after sauna, we sat in front of the crackling fire in the candle-lit living room, cooking sausages over the embers or simply reading and listening to the cries of red-throated divers and terns out on the lake. Late at night, such magic was often spoiled by rogue mosquitoes trapped inside the house. Just one tiny insect could keep us all awake until someone managed to hunt it down. As the house didnt have central heating, my family used it mostly in the summer. Over the winter it required an occasional check for too much heavy snow on the roof, storm damage and the potential of theft due to its isolated location. At the start of the summer, the first heating of the various fireplaces required burning small amounts of newspaper before a proper fire in order for the house to become safely lived in again. The house and its textiles had to be thoroughly aired after the damp months of the winter. Though my parents were keen gardeners, they were able to escape the need for gardening at the summer house since the land all around was untouched, middle-aged forest. The forest around provided opportunities for enjoying many birds including woodpeckers, chiffchaffs, chaffinches, greenfinches, wrens, redstarts, willow warblers, spotted flycatchers and redwings. As with many peoples childhood, my summers seemed very long all those decades ago. Much of Finland closed down for the month of July because most working people took off four weeks of their summer holiday in one go. This meant my parents and us four sisters could move out of our winter dwelling and spend long stretches of time in our summer house. According to the official statistics, at the end of 2009, there were 485,100 summer houses in Finland, a country of just under 200,000 lakes and an equal number of islands. There, a summer house is classed as a residential building that is permanently constructed or erected on its site to be used as a holiday or free-time dwelling. In the 1970s, life in most Finnish summer houses excluded practically all the modern electric conveniences. Many, if not most, summer houses are now equipped for use year-round with connections to mains water and electricity. Tuula Pardoe is a conservator of costume and textiles based in South Queensferry. She grew up in Pori on the west coast of Finland.

y father, equipped with a wide range of woodworking and other skills needed to build a timber-framed house, built our summer house towards the end of the 1960s with the help of friends. The house was built on a piece of land in a forest, bought from a local farmer, on a slight hill meters away from the shore of Lake Isojrvi on the west coast of Finland. A good number of pine, spruce, silver birche, mountains ash, aspen and juniper had to be cleared from the plot to make way for the foundations of the house. The house had a large, wood-panelled living room, a small kitchen, two bedrooms, a combined sauna and wet-room, a changing room and a veranda. Only candles, oil-burning storm-lanterns and fire in the natural stone fireplace of the living room provided light in the late-evenings. A brick-built wood-burning stove and oven combination was used for cooking. There was no running water in the house, so bucketfuls were carried from the lake for the sauna. An outside composting toilet slightly away from the house provided basic toileting facilities. The thought of coming across an elk or two on a journey to the loo at dusk made such visits nerve-wrecking. With the car loaded with four children, food, and all drinking water in large canisters, we headed an hours drive north for the summer house and stayed there for a week or two at a time. Although neighbours in the forest were relatively few and far between, one of the nearest neighbouring families had two daughters only a little older than the four of us. Weather permitting, the six of us spent hours out of doors. Wellies were our summer footwear for fear of coming across black adders amongst the dense undergrowth of the forest. We spent a lot of time

p36

ISSUE 43

Reforesting Scotland

SPRING/SUMMER 2011

BOOK REVIEWS

Ugly truths of land ownership

The Poor Had No Lawyers Who Owns Scotland (and how they got it), Andy Wightman. Birlinn, 2010. ISBN 978 184158 907 7. 20.00. Although the author doesnt once use that tired phrase, the stark lesson from this immensely detailed work is that possession is nine tenths of the law, and the glittering prizes went to those who had the leisure to spot the latest trend and the ingenuity to harness it to their own best interests. The biggest landowners have for centuries been a step ahead in the game, consolidating their holdings and concurrently laundering their image as they morphed from medieval warlord to pillar of society. The involvement of the landed classes in such seminal events as the Reformation (starving the Church of Scotland of its startup funds by appropriating most of the property of the Catholic Church) and the Covenanters (pressurising the clergy into this movement to avoid repossession of the aforementioned lands by the Restored Monarchy) displays a cynical self interest that seems startlingly modern for men in tights and lace. This book is so full of the results of detailed research that all I can do to give you a avour of its coverage is highlight the cases that grabbed my interest. Since the whole subject is of such import it was difcult to choose. For one with Skye connections, the revelation that 23,000 acres of the Cuillin range was put up for sale by John McLeod when his family had title to 1,600 acres at the most is a gob smacker. The myth that Queen Victoria fell in love with the Balmoral Estate and bought it is here unpicked. The wise old bird rst rented the land, then in 1852 her consort bought it. Conveniently, a law was passed to prevent this arrangement being questioned, and in 1862 the Crown Private Estates Act enabled Victoria to inherit it as private property, so it would not become part of the Crown Estates and be involved in the Civil List calculations. What was that bit about not taking private advantage of public ofce? Closer in time and geography is the example of Waverley Market and whether or not it forms part of Edinburghs Common Good Land. Since under proposed new legislation the tenant stands to become the owner of many millions of pounds worth of real estate in return for a handful of chicken feed, how can the council sit and let this happen, whether it is the peoples land or the councils land? The enormous amount of detailed knowledge required to become even acquainted with this subject, never mind expert, surely delays the achievement of critical mass awareness, without which I fear real land reform will not happen. This book is a great contribution to the cause. Sally Macpherson

ISSUE 43

Reforesting Scotland

SPRING/SUMMER 2011

p37

BOOK REVIEWS

Building and working in wood

where coppice woods are dominated by sweet chestnut, but this species doesnt grow well in northern Britain. He also has a soft spot for the black locust tree (Robinia pseudoacacia) which he lists among his top ten trees despite having very limited usage in the UK. He doesnt comment on the qualities of home-grown versus Canadian western red cedar for shingles. When we put up a green woodworking shelter at Wooplaw Community Woodland recently, we were advised that home-grown cedar isnt durable and that larch would be better. Roundwood Timber Framing Building Naturally Using Local Resources, Ben Law. Permanent Publications, 2010. ISBN 978 185623 041 4. 19.95. I think I really could do it... build my own roundwood framed house with a lot of help from friends, some good weather and Ben Laws book to consult. I reckon hes succeeded, turned a ham-sted DIY enthusiast into someone who feels he could build a lasting structure out of wood, or at least would like to try sometime. Ben Laws descriptions are unfussy and unpretentious. He calls a Japanese saw a Japanese saw. You can see what hes getting at and if you cant, he thoughtfully provides a photo or sketch of the very bit you were struggling to visualise. The book has a nice chunky feel to it, with glossy paper to shed the rain and show off the multitude of clear illustrations. And importantly, it sits open at the page you are interested in. Dont read this book for woodland management advice. Ben states that coppice can sustain more people per acre than any of the modern forestry alternatives. I would agree with this statement if only there were markets for coppice products. Maybe its different down in Sussex This isnt a woodland management book though, its a manual for putting up beautiful, functional roundwood framed buildings. The tools section is very engaging, really giving a feel for their functional beauty. Old tools and new tools, all t for purpose, like those Japanese saws. The core of the book is the section on construction, from simple foundations to the nal embellishments. This is a tour de force, with buildings growing before your eyes. And the completed houses, especially his own Woodland House as featured on Channel 4s Grand Designs, are so gorgeous theyre almost edible. Donald McPhillimy Shedworking The Alternative Workplace Revolution, Alex Johnson. Frances Lincoln, 2010. ISBN 978071123 082 8. 16.99. This handsome and comprehensively illustrated book sings the praises of working in a small space. It springs from a website www.shedworking. co.uk which the author runs from his own garden shed. He is keen to promote home working, but is clear that a home/ofce distinction is necessary. In his opinion the garden path provides just enough distance to make working in a shed ideal. Featured are buildings from demipalaces to huts. The most elaborate sheds are architect-designed, employ unsustainable materials such as aluminium and plastic, and look ashily urban. Even some of the prefabricated, module-based sheds fall into this category, with gimmicks such as electronically controlled dimming glass. Desirable as that may be for a fully-glazed building, a smarter design might utilise natural sunlight without creating more dependence on the outside world and clocking up electricity bills. At the other end of the scale there are ramshackle and homely shelters. Some are built entirely from recycled

SPECIAL OFFER

XXXxxXXXxxXXXxXX XXXx xXx x x x X xxxxx xxx xXxxXXX XXXXXxxxx xxx xxx XXXxxXXXxxXXXxXX XXXx xXx x x x X xxxxx xxx xXxxXXX XXXXXxxxx xxx xxx

p38

ISSUE 43

Reforesting Scotland

SPRING/SUMMER 2011

BOOK REVIEWS

materials: windows, doors and panels that came off scrap heaps. By and large they look t for purpose but not pretty. Among them are more sympathetic structures such as that of Chris Routledge, writer and editor of The Reader. He built his own rustic shed after attending a course at the Centre for Alternative Technology in mid-Wales. He is delighted with both the building process and with the result, which he says now shapes his writing. That rst week, listening to the rain pounding on the roof I had made, but not coming in, I felt connected with something very old and very human. That feeling is also there in the process of writing itself. Alex Johnson has been thorough in researching all shed possibilities. This is a wonderful source book if you want to purchase someone elses shed design, or commission any shed from a custom-built cob building to a renovated shepherds hut on wheels. If you dont have such resources at your disposal, then there is still plenty to inspire. The shed constructed on an old Ifor Williams trailer to be both site-hut and dwelling for someone renovating an ancient building is a good example. Having the shed mobile made its construction off-site and its removal to-site easy, and the owner was able to side-step planning regulations. As far as these are concerned, there is a chapter that claims to be Everything you need to know about Planning Permission and Building Regulations. It applies to England, but in Scotland you will have to do your own homework. Constructing a mobile shed seems like a wonderful way round the problem (see page 27). Fi Martynoga

Woodland life

Surges included activities of the 18th and 19th century planting lairds, like the Duke of Atholl, cultivating new species discovered by plant explorers like David Douglas. The great 20th century surge was a response to almost running out of timber during the two World Wars. The Forestry Commission (FC), set up in 1919 and led by war hero Lord Lovat and the bullish Australian Roy Robinson, was tasked with buying land of little use for agriculture; the early leaders went along with this to prove how commercial the new forestry could be. It was bound to be commercially viable when the average price paid for plantable land was 1 15s 4d per acre! Buying the rst land happened to coincide with a bad time for landowners, with a quarter of Britains land area changing hands between 1918 and 1922. After WW2, the FC was asked to redouble its efforts its trees had been too young to contribute much during the war. Chancellor of the Exchequer Hugh Dalton asked Robinson, still FC chair: What is the largest sum you could efciently spend over the next ve years? Robinson asked for and got 20 million. In return he gave Dalton an FC tie. The evolution of forestry from the building up of a timber resource to its current multiple objective status is clearly laid out in a very readable way. Reforesting Scotland even gets a mention near the end described as campaigning for a new forest culture and punching well above its weight. I think this is a compliment. And heres a compliment for the book: it is a good read, and an essential one if you want to understand how we came to have the forests and forestry we have today. Donald McPhillimy

Woods & People Putting Forests On The Map, David Foot. The History Press, 2010, ISBN 987 07524 5278 4. 18.99. Have you ever wondered why the UK has ended up with such a dislocated forest estate, pushed to the margins, and an almost complete loss of forest culture? This book tells you why. It explains how some of the biggest potential disasters, such as almost running out of timber during both World Wars, and the afforestation of the Flow Country, were narrowly averted. David Foot, a former Forestry Commissioner and trustee of the Woodland Trust, has produced a lucid account of the last 200 years of forests in this country. The history of our forests is very different to those of our European neighbours. There have been retreats and surges: retreats due to the ood of cheap imports, the two World Wars and the agricultural revolution that followed. During WW2, 46% of the UKs forests were felled to supply 75% of consumption, as imports were cut off.

SPECIAL OFFER

For members of tree and forestry bodies: 14.99 (includes free p&p) until 30 April 2011. Quote offer code HPWoods. Buy online at www. thehistorypress.co.uk or call Marston Book Services, tel. 01235 465577.

ISSUE 43

Reforesting Scotland

SPRING/SUMMER 2011

p39

DATes fOr yOur diAry

Dates for your diary

Regular events

The following organisations run events throughout the year: BTCV Scotland. Wide range of volunteer activities and environmental training courses. There are 16 Green Gyms throughout Scotland. Contact Helen Paul, tel. 01786 479 697, email scotland-training@btcv.org. uk or see www.btcv.org/scotland Oatridge College, West Lothian. Several short courses offered, from chainsaw and machinery operation to blacksmithing and livestock care. Some provide a qualication, and may attract ILA support (check your eligibility at www. ilascotland.org.uk). Tel. 01506 864 807 or see www.oatridge.ac.uk/ short_courses Scottish Native Woods meet on the rst Sunday of every month, 10am to 4pm, to restore and expand native woodlands. Tools, training and safety equipment provided. Contact Chris Childe, tel. 01337 832 619, email chris. childe@scottishnativewoods.org. uk or see www.scottishnativewoods.org.uk Trees for Life. Volunteer Work Weeks in the Scottish Highlands, many dates from March to September. Work includes planting trees, felling non-native trees, tree nursery work, wetland restoration, collecting seeds and berries, stock fencing and tree guards, tree fertilising. Tel. 0845 602 7386 or see www.treesforlife.org.uk

April

9 10: Pig Weekend make a willow pig for the garden. West Moss-side, Thornhill, Stirling, FK8 3QJ. Price 130 plus materials. Tutor: Anthea Naylor. Contact Kate Sankey on tel. 01786 850428 or kate@westmosside.com, special rates to stay in the new Trossachs Yurts. Details of more inspiring craft courses at www.westmossside.com 13 14: Institute of Chartered Foresters National Conference entitled Trees, People and the Built Environment, in Birmingham. Groundbreaking and highly relevant research from both the natural and social sciences will be presented. Call Allison Lock on 0131 240 1425 or see www. charteredforesters.org/conference 16: Ceilidh Collective Spring Ceilidh supporting Redhall Walled Garden at the Rudolf Steiner School, 60 Spylaw Rd, Edinburgh, EH10 5BR, 7pm - midnight. Tickets are 10, 6.50 (conc.) or 3.50 (under-12) available from www. thebooth.co.uk 22 24: South West Community Woodlands Easter Festival, Taliesin. Wood Carving with Richard Jones, Basket Making with Trevor Leat, kids Easter egg activities, wild food foray and Japanese knotweed fest. Courses 120 for 3 days or 45 per day. Contact Jools Cox on 01556 503 649, email joolscox@ tiscali.co.uk, or see www.swcwt.org Sustainable Scotland Network for details of their April Quarterly meeting see www.sustainablescotland.net

Oatridge College offers courses in livestock care. Photo: Karen Grant

Carrifran Wildwood, Moffatdale. Volunteer days every third Sunday of the month except July, August, December. Meet 10am at Carrifran car park on A708 Moffat to Selkirk road. No need to book; bring weatherproof clothing, boots and packed lunch; be prepared for a fairly strenuous day. Information from George Moffat, email george@bordersforesttrust.org, tel. 01835 830 750, mobile 07939 784 387 or www.carrifran.org.uk Falkland Centre for Stewardship. Events planned for 2011 include Woodland Summit, Introduction to Green Woodworking, Basket Making, Bush Craft, talks, childrens workshops, Summer and Autumn Schools. Dates known at time of going to press are listed below. For information about others, tel. 01337 858 838 or see www.centreforstewardship.org.uk Four Winds Inspiration Centre. This wonderful centre has sadly come to the end of its lease at Inverleith Park. Carole Fraser is now out on location, offering craft classes and training. www.four-winds.org.uk John Muir Trust. Free Conservation Work Parties of 1 to 7 days on JMT properties and those of partners, March to October. Contact Sandy Maxwell, tel. 0141 576 6663, email conservationactivities@jmt.org or see www.jmt.org/activitiesconservation-work-parties.asp

p40 ISSUE 43

March

17: Scotlands Independent Regeneration Network Annual Conference entitled Supporting Community Resilience. Roxburghe Hotel, Edinburgh. Tel. 0141 585 6879 or email derek@scotregen. co.uk 20: Carrifrans rst tree planting day of the year. See above for joining details, and if you would like to spend a Wednesday working in the Devils Beef Tub, contact ed@bordersforesttrust. org for more information or see www.bordersforesttrust.org 20: South West Community Woodlands Trust. Get involved with Orchards and Wild Harvest, a local project supported entirely from public donation and the donation of trees for local community areas. Contact project co-ordinator Jools Cox on 01556 503 649 or joolscox@tiscali.co.uk 29 31 May: Dog Agility classes (tness for you and the pooch) with Oatridge College and Broxburn Dog Training Club. Tuesdays 5.45-6.45pm. Tel. 01506 864800 or email info@oatridge. ac.uk

May

6 8: Tanera Mr, Summer Isles. Flora, fauna and foraging with Viv Halcrow. 180 full board including transport from Badentarbet Pier. Contact lizzie@summer-isles.com, tel. 01854 622 252 or see www. summer-isles.com 6 8: Arduaine Spring Festival, NTS Arduaine House, Argyll. Weekend programme of talks, garden tours and gourmet dining, booking essential. Open to public on afternoon of 8th with craft demonstrations, stalls and music. See www.nts.org.uk/Events/ Detail/525

Reforesting Scotland

SPRING/SUMMER 2011

DATes fOr yOur diAry 27 30: JMT conservation work party to Li & Coire Dhorrcail (Knoydart). Fence removal, path works and beach cleaning, see above for contacts. This involves walk in and wild camping. See above for contact information.

August

5 8: JMT Conservation Work Party at Strathaird, Skye. Woodland, beach cleaning and general tasks. See above for contact information. 15 19: Falkland Centre for Stewardship. Hut Building training in the art of hut building using only local wood. Email info@centreforstewardship.org.uk to register interest and for further details.

535 covers accommodation and materials. Contact katy@ galvelmore.co.uk, tel. 01764 655721 or see www.galvelmore. co.uk/event8.htm

June

Sustainable Scotland Network for details of their June Quarterly meeting see www.sustainablescotland.net 31 May 4 June: Falkland Centre for Stewardship. Field of Vision a rites of passage fiveday Summer School exploring the hows and whys of ceremony and celebration in a practical and experiential way. 295-350. See above for contact details.

September

2 9: Tanera Mr, Summer Isles. Creative Retreat with Mandy Haggith. 525 full board including transport from Badentarbet Pier. Email lizzie@summer-isles.com, tel. 01854 622 252 or see www. summer-isles.com 11 17: Tanera Mr, Summer Isles. Flora, fauna and foraging with Viv Halcrow. 180 full board including transport from Badentarbet Pier. Contact lizzie@ summer-isles.com, tel. 01854 622 252 or see www.summer-isles.com 19 23: Galvelmore House, Crieff. Residential course Words from the Woods with Jan Kilpatrick. Write, make and bind your own journal of the week.

July

9: Enjoy the roses at National Trust for Scotlands Drum Castle, 7-8pm. Advance booking essential, tel. 0844 4932161. 10 23: BTCV conservation holiday to Iceland, building and repairing mountain paths in Vatnajkull National Park. Other dates and venues available, tel. 01302 388 883 or email information@btcv.org.uk

In August Falkland Centre for Stewardship will run a course in hut building. Photo: Karen Grant

List an event!

To submit events or organisations for listing on this page, contact us on tel. 0131 220 2500, email journal@reforestingscotland.org or post to Reforesting Scotland, 58 Shandwick Place, Edinburgh, EH2 4RT. The next issue will cover dates from mid-September to March 2012.

Logging on to... huts

here is a wealth of material about huts on the internet, for casual browsing or more specic searching. For once I decided not to narrow the search, but to put huts into most of the options offered by Google. If youre looking at news about huts, you quickly learn that huts arent always happy places. Where crowds of people live in huts, re hazard comes with the territory. More cheerful is the news that huts built by a church group for residents of the Tent City in Lakewood, New Jersey, enabled all the unemployed who live there to survive the winter blizzards. Google Maps will show you mountain and walking routes all over the world with huts providing shelter and refreshment, and on You Tube you can watch the rst ever (1965) TV commercial for... Pizza Hut! Google Images displays everything from bathing huts in sleepy seaside towns now going for massive prices, luxury hutted accommodation on those notquite-back-to-nature holidays, the straw huts of the oating Uros islands on Lake Titicaca, stone-built beehive huts for Irish monks, refugee huts near Beledwyne in Somalia, slave huts on Bonaire in the Caribbean and the more recent barrack huts at Auschwitz. Closer to home, the page Huts & Cabins in Scotland on the social networking site Facebook, www. facebook.com/pages/Huts-Cabinsin-Scotland/164760157794, offers a good overview of all manner of camping huts and cabins available for hire in Scotland, from traditional shing bds in Shetland to a luxury, naturist friendly wooden chalet in Galloway. Sally Macpherson

ISSUE 43

Reforesting Scotland

SPRING/SUMMER 2011

p41

LAsT WOrd

The campaign for a Thousand Huts

Overwhelming interest from many quarters, not least Reforesting Scotlands membership, has indicated tremendous support for a resurgence of hut-building in Scotland. In response, RS is launching its campaign for a Thousand Huts, as Ninian Stuart explains.

eforesting Scotlands new campaign for a Thousand Huts will celebrate and encourage hut building in Scotland. Coordinated by land rights campaigner Andy Wightman alongside RS members and directors, a Thousand Huts hopes to inspire people with the simple beauty and usefulness of huts, places to dwell in the forest supporting the aspiration for simplicity and self-reliance giving space for thought and freedom from thought bringing a deeper acquaintance with silence and darkness. you in touch with other interested farmers and landowners who are considering this. 6. Tell a great hut story. Were keen to learn and tell the story of Scotlands huts and hutters. From the Carbeth clearances to the building of great huts and even great hut-building disasters. Please let us know if you have stories to tell or if you get a sniff of a story that one of our roving reporters can follow up. 7. Lay foundations for future huts. A Thousand Huts urgently seeks help from dynamic social entrepreneurs, skilled builders and ardent micro-living campaigners to help build our dream. Let us know if you can help here. 8. Attend RSs great celebration of forest culture and launch of a Thousand Huts being planned for June (date to be conrmed shortly). 9. Take part in Reforesting Scotlands hut-building summer school in partnership with Falkland Centre for Stewardship (provisional date 15 19 August 2011). See www. centreforstewardship.org.uk for more information. 10. Join our hut circle. If you are keen to contribute to the campaign, receive occasional briengs and be amongst the rst to hear of whats happening in the campaign for a Thousand Huts, email to huts@ reforestingscotland.org And three things to remember (if you forget everything else!): Spend time in a hut Build a hut from local wood Join the movement for a Thousand Huts. Ninian Stuart is co-founder of Falkland Centre for Stewardship and is a Director of Reforesting Scotland. Email ninian@ centreforstewardship.org.uk

Ten things you can do:

Illustration by Alastair Biard

and seed the idea of a thousand more at this time of transition. It will hopefully highlight the value of huts built in and from Scottish woods, and the need to overcome the main obstacles to building more of them, addressing both planning law and lack of opportunities to own or rent land in rural Scotland. The campaign will see RS collaborating with its members, local community groups and key organisations such as the Scottish Ecological Design Association, Community Woodland Association and Mountain Bothies Association to encourage and facilitate more local hut building using timber from Scottish woods. If our campaign is successful, we believe that a thousand huts will ourish in Scotland... allowing more people to reconnect with the natural world inspiring ordinary people to learn the craft of building providing refuge from speed and noise creating simple and beautiful

p42 ISSUE 43

1. Discover huts. Open your eyes and heart to huts. Whether in a wood or town, see what people have built: garden huts, beach huts, hidden huts, fancy huts and old ramshackle huts. Take photos or sketches and email us anything special. Were keen to enjoy and share the diversity of Scotlands huts and be inspired by huts beyond our borders. 2. Build a hut. Something you will never regret. It is one of the most constructive things you can do, especially using local wood. If youre not very practical, nd a skilled person to advise you. You may contact some of those whose stories we tell in this edition, or join a course. 3. Spend time in a hut. Go there regularly to slow down and get away from noise, clutter and busyness. A simple place to focus on what really matters. If you cant nd a real hut, you may need to make do with a hut-in-your-mind. Or rent one for a few days. 4. Discover a hut site. We know of hutters sites and communities at Carbeth near Glasgow, Clouch in Gourock, Soonhope and Eddlestone near Peebles, Lunga Estate in Argyll and Rascarrel Bay and Carrick on the Galloway coast. These are the remnants of a much wider Scottish hutting tradition. Many are still threatened. All need our support. Please let us know if you know of others. 5. Create a hut site. If you are (or know of) someone who owns land and may be interested in making land available, we are keen to hear from you. And we will put

Reforesting Scotland

SPRING/SUMMER 2011

Você também pode gostar

- Early American Wooden Ware & Other Kitchen UtensilsNo EverandEarly American Wooden Ware & Other Kitchen UtensilsAinda não há avaliações

- A Little Book of Vintage Designs and Instructions for Making Dainty Gifts from Wood. Including a Fitted Workbox, a Small Fretwork Hand Mirror and a Lady's Brush and Comb Box: Including a Fitted Workbox, a Small Fretwork Hand Mirror and a Lady's Brush and Comb Box.No EverandA Little Book of Vintage Designs and Instructions for Making Dainty Gifts from Wood. Including a Fitted Workbox, a Small Fretwork Hand Mirror and a Lady's Brush and Comb Box: Including a Fitted Workbox, a Small Fretwork Hand Mirror and a Lady's Brush and Comb Box.Ainda não há avaliações

- 05f1501ie PDFDocumento16 páginas05f1501ie PDFJosh Sam Rindai MhlangaAinda não há avaliações

- Panel JigDocumento16 páginasPanel JigfasdfAinda não há avaliações

- Crotch-Grained Chess Table: Walnut, PoplarDocumento5 páginasCrotch-Grained Chess Table: Walnut, Poplarkhunchaiyai100% (2)

- Army Engineer Carpentry IIIDocumento66 páginasArmy Engineer Carpentry IIIPlainNormalGuy2100% (1)

- Lock Rabbet Drawer JointsDocumento3 páginasLock Rabbet Drawer JointsSANTI90900% (1)

- Book Case - Barrister 1Documento6 páginasBook Case - Barrister 1Cris CondeAinda não há avaliações

- Çalışma Tezgahı PlanıDocumento14 páginasÇalışma Tezgahı PlanıÖmür Eryüksel50% (2)

- How To Build A House of Modern AdobeDocumento48 páginasHow To Build A House of Modern AdobeNaava BasiaAinda não há avaliações

- How To Make A Cornhole BoardDocumento4 páginasHow To Make A Cornhole BoardAndré VeigaAinda não há avaliações

- How To Make A Meat SafeDocumento5 páginasHow To Make A Meat SafeChristian Theriault100% (1)

- SOIL TEXTURE Science Page: No Matter How Much I Water, These Plants Keep Wilting!Documento2 páginasSOIL TEXTURE Science Page: No Matter How Much I Water, These Plants Keep Wilting!Duy Ngọc Lê100% (1)

- Home Building TipsDocumento245 páginasHome Building TipsoltaiyrxAinda não há avaliações

- Small Colonial Bench: Project 10297EZDocumento5 páginasSmall Colonial Bench: Project 10297EZmhein68Ainda não há avaliações

- How To: Build A Raised-Bed Garden: 2. Attach The EndsDocumento20 páginasHow To: Build A Raised-Bed Garden: 2. Attach The EndsAndre Duvaux100% (1)

- Workshop Assignment: By: Sneha Motghare Div: B Roll No:26 Batch:2 Taught By: Vilas SirDocumento15 páginasWorkshop Assignment: By: Sneha Motghare Div: B Roll No:26 Batch:2 Taught By: Vilas SirVinay MotghareAinda não há avaliações

- Jig Creation Instruction ManualDocumento14 páginasJig Creation Instruction ManualBig Deal VolumesAinda não há avaliações

- Carpentry III - Specialized CarpentryDocumento66 páginasCarpentry III - Specialized CarpentryChuck Achberger100% (1)

- UNIT - IV CarpentryDocumento14 páginasUNIT - IV CarpentryAjay SonkhlaAinda não há avaliações

- David de Lossy/Photodisc/Getty ImagesDocumento15 páginasDavid de Lossy/Photodisc/Getty ImagesasiasiAinda não há avaliações

- 80 - Cutting Diagrams - Heirloom Tool CabinetDocumento3 páginas80 - Cutting Diagrams - Heirloom Tool CabinetGsmHelpAinda não há avaliações

- Arbor - Lath Arch Rose ArborDocumento6 páginasArbor - Lath Arch Rose ArborDaniel LourençoAinda não há avaliações

- A Classic CaseDocumento6 páginasA Classic CaseTarek YoussefAinda não há avaliações

- Wall Mounted Shoe RackDocumento7 páginasWall Mounted Shoe RacksyafiqAinda não há avaliações

- Microfiche Reference Library: A Project of Volunteers in AsiaDocumento21 páginasMicrofiche Reference Library: A Project of Volunteers in AsialinteringAinda não há avaliações

- WJ099 Picnic Table PDFDocumento0 páginaWJ099 Picnic Table PDFCarlos A. Mendel100% (1)

- Build a Post-and-Plank Retaining WallDocumento13 páginasBuild a Post-and-Plank Retaining WallAnonymous 1TTYYaAinda não há avaliações

- Pine Desk Organizer: Project 13782EZDocumento6 páginasPine Desk Organizer: Project 13782EZBSulli100% (1)

- Box Joinery 4.25ver8Documento5 páginasBox Joinery 4.25ver8cajemarAinda não há avaliações

- GE6162-Engineering Practices Laboratory PDFDocumento167 páginasGE6162-Engineering Practices Laboratory PDFBala ChandarAinda não há avaliações

- Ts440s Repair FaqDocumento17 páginasTs440s Repair FaqboardstAinda não há avaliações

- Build Your Own French Doors - Popular Woodworking MagazineDocumento34 páginasBuild Your Own French Doors - Popular Woodworking Magazinekostas1977Ainda não há avaliações

- Woodworking Techinque - DoorsDocumento97 páginasWoodworking Techinque - Doors_Godfather100% (2)

- PostarA Bench Built To LastDocumento6 páginasPostarA Bench Built To Lastbonte01100% (2)

- Woodworking TipsDocumento13 páginasWoodworking TipsjahemscbdAinda não há avaliações

- Free 12 X 8 Shed Plan: MyshedplansDocumento24 páginasFree 12 X 8 Shed Plan: MyshedplansWoody Glenn DeJongAinda não há avaliações

- Rotating Barrel ComposterDocumento3 páginasRotating Barrel Compostertraction9261Ainda não há avaliações

- Ece Complete Book of Woodworking ToolsDocumento33 páginasEce Complete Book of Woodworking ToolsRutger Hermens100% (2)

- Recommended Reading ListDocumento16 páginasRecommended Reading ListCiciYabgu50% (2)

- Roll Around Kitchen Cart: MLCS Items UsedDocumento15 páginasRoll Around Kitchen Cart: MLCS Items UsedTETSUO111Ainda não há avaliações

- Red Wing Steel Works 3x5 Heavy Duty Welding Table Plans PDFDocumento7 páginasRed Wing Steel Works 3x5 Heavy Duty Welding Table Plans PDFDavid BondAinda não há avaliações

- Wood Working Plans 2aDocumento11 páginasWood Working Plans 2aNicusor Amihaesei100% (1)

- Mission Furniture 1Documento104 páginasMission Furniture 1cipripop100% (1)

- DIY Barn Door Baby GateDocumento17 páginasDIY Barn Door Baby GateJessicaMaskerAinda não há avaliações

- Make A Wheel Marking GaugeDocumento6 páginasMake A Wheel Marking Gaugeserkan ünlü100% (1)