Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Gifted Achievers and Underachievers

Gifted Achievers and Underachievers

Enviado por

veeinyDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Gifted Achievers and Underachievers

Gifted Achievers and Underachievers

Enviado por

veeinyDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Gifted achievers and underachievers: A comparison of patterns found in school files

This article by Jean Peterson and Nicholas Colangelo describes a study of gifted students who achieve and underachieve. School files were examined to try to find links and reasons for underachievment. The author sidentify a number of correlations, and suggestions are made for school counselors on how they might help with this problem. Underachievement in gifted students has perplexed educators and parents for decades. Researchers are continually looking for information about the nature and patterns of gifted underachievers that will enlighten those concerned. Counselors are particularly involved, because they often are asked to provide illumination and interventions. This study demonstrates how information in the cumulative school file, accessible to the school counselor, is a rich resource for understanding the patterns of achievement and underachievement among students identified as gifted and for use in planning interventions for students at risk for underachievement. Participants were gifted students (N = 153) who were determined to be either achievers or underachievers, based on their grade point average at graduation. High and moderate achievers and moderate and extreme underachievers were compared on information found in the school file, such as attendance, tardiness, course selection, and onset and duration of underachievement. Results indicate that there are differences between achievers and underachievers on a number of variables found in the school files. Profiles of these groups are presented with suggestions for actions by counselors. Much has been written during the past several decades about underachievement among students with high ability (e.g.. Fehrenbach, 1993; Gowan, 1955; Kirk, 1932; Mandel & Marcus, 1988; Raph, Goldberg, & Passow, 1966; Rimm, 1986; Shaw & McCuen, 1960; Thiel & Thiel, 1977; Whitmore, 1980). Some researchers have estimated that the percentage of students with high ability who do not achieve well is as high as 50% (e.g., Hoffman, Wasson, & Christianson, 1985; Richert, 1991; Rimm, 1987), and underachievers are among the groups of talented children who are neglected or underserved in programs for the gifted ("National excellence," 1993). Although no precise definition for "underachievement" has evolved, it has generally been seen as a discrepancy between expected and actual performance (e.g., Davis & Rimm, 1989; Dowdall & Colangelo, 1982). School-related and nonschool-related variables have been studied and discussed, and numerous causative or correlative factors have been suggested. Nevertheless, questions remain: Why do highly able students perform poorly academically when they have potential for high achievement? What characteristics distinguish these students from those who achieve? and What useful information might be available to counselors in order to plan effective interventions? Researchers in gifted education have not explored the wealth of pertinent information that can be found in student cumulative files. Counselors have ready access to these data, which, even in early school years, might show events or patterns that would be important clues to difficulties that are not yet obvious in classroom behavior. Baker and Shaw (1987) noted that school records are not used in any systematic way for identification of children who may be at risk. They advocated that this readily available information about behavior, achievement, and attendance be used to identify students early enough to be able to use primary prevention instead of remediation. This study began with the assumption that an examination of school flies must locate patterns among both students who achieve and those who underachieve. Indications regarding longterm versus short-term or intermittent underachievement might appear, and factors having an

impact on onset and improvement might also be apparent in the records. The following is a discussion pertinent to patterns of achievement and underachievement in general and in gifted students in particular. ATTENDANCE AND TARDINESS Although studies have documented the importance of school attendance to achievement in general (e.g.. Baker & Shaw, 1987; Easton & Engelhard, 1982; Monk & Ibrahim, 1984; Wiley & Harnischfeger, 1974). Baker and Shaw (1987) noted that although a decline in attendance may signal a child at risk, schools rarely investigate changes in attendance patterns. Researchers in gifted education have neglected to study attendance and tardiness as important factors regarding achievement and underachievement. Lists of characteristics of gifted underachievers usually do not include references to those areas (e.g., Clark, 1983; Davis & Rimm, 1989; Whitmore, 1980). ONSET OF UNDERACHIEVEMENT Easton and Engelhard (1982) reported the significance of the junior high years regarding attendance and changes in academic achievement. Scholastic underachievement is generally thought to be first obvious at the junior high level, increasing throughout high school (Pendarvis, 1990), although some researchers have found evidence of earlier onset (Barrett, 1957; Reis, 1987; Shaw & McCuen, 1960; Whitmore, 1980). Nash (1984) observed the significance of Grade 8 for underachievement. Adjustment problems increase as gifted children enter adolescence, according to Janos and Robinson (1985). There also is evidence that self-perceptions of competence decline dramatically during junior high (Benenson & Dweck, 1986; Stipek, 1981). In general, many students who are able to accept the "gifted" status in elementary grades choose to reject it in adolescence when the peer culture becomes the primary group (Bireley & Genshaft, 1991). Baum, Owen, and Dixon (1991) speculated that some gifted children, perhaps relying on oral verbal talent, may become careless and disorganized regarding written work as they progress through elementary grades. With the emphasis on long-term written work and independent reading during middle and junior high school, these students may find it more and more difficult to achieve. They may become depressed and confused about why, as gifted students, they are having difficulty. DURATION OF UNDERACHIEVEMENT Several researchers have connected family disruption to underachievement (e.g., Rimm, 1986; Terman, 1947), as well as parental discord (Laycock, 1979). These two factors are likely to produce episodic (i.e., short-term or intermittent) underachievement. By contrast, systemic factors, such as adverse socioeconomic conditions, which can include poverty, low motivation, language problems, and ethnic differences, and which have been noted by Khatena (1982) and Pendarvis (1990) as contributing to underachievement. are more likely to contribute to chronic (i.e., long-term) underachievement. Family attitudes toward school and jobs (Kahl, 1953) and aspirations either too low or too high (Laycock. 1979) also have been implicated as factors in underachievement and are likely to contribute to long-term, rather than short-term underachievement. GENDER DIFFERENCES Gender differences in underachievement have been cited in research. Gifted boys outnumber gifted girls in school underachievement (Colangelo, Kerr, Christensen, & Maxey, 1993; Gowan &. Damos, 1964; Raph et al., 1966; Stockard & Wood, 1984). Weiss (1972) found

that approximately half of all male students but only 25% of female students who are above average in ability may be considered underachievers. Although male students outnumber female students among underachievers, recent research has shown increased attention to female underachievers. Internal and societal ambivalence about achievement may cause more conflict for underachieving female than male students about realizing their intellectual potential (Butler-Por, 1987). Buescher and Higham (1989) and Silverman (1993) proposed that female students are more at risk than male students for avoiding their talent as they struggle with the force of belonging. They might underachieve intentionally as a trade-off for acceptance (Dowdall & Colangelo, 1982; Rakow, 1989). The fact that physical appearance and global self-worth components of self-esteem decline more for female than for male students after age 12 might have relevance to academic choices and aspirations in female students (Bucscher & Higham. 1989). Jacobs (1991) found that an interaction effect between parents' gender stereotypes and children's self-perception influenced performance. She speculated that girls might be adversely affected by that indirect influence. Benbow's (1992) findings about mathematics course choices for female students support this hypothesis. PURPOSE OF STUDY Although there have been a number of issues documented concerning achievement among gifted students, there are several important dimensions that have not been analyzed. Research has addressed onset of underachievement to some extent, but not duration and not incidence of periods of underachievement among achievers. It has addressed course selection as related to performance on scholastic aptitude and achievement tests, but not with attention to demanding versus undemanding courses or to sustained achievement in specific courses during periods of general underachievement. Attendance has been studied as it relates to achievement in general, but not as it relates to various categories of achievement, and attendance patterns of students identified as gifted have not been analyzed. Finally, researchers have not focused on absences as a risk factor or as an early warning of underachievement in gifted students. The areas that have not received attention are important for understanding differences between achievers and underachievers and for devising interventions in the school setting. This study focuses on those areas of omission, for both scholarly understanding and for practical benefit to teachers, counselors, and students themselves. Raising the awareness of counselors is crucial, within and outside of the school setting, regarding data that might be studied during screening for existing or emerging patterns of underachievement or for planning interventions for at-risk students. All schools maintain files on students. The information needed to address these critical issues can be found in the readily accessible data in those files. The purpose of this study was to examine the school records of a population of gifted students, during Grades 7 through 12, and make appropriate comparisons between those who achieved and those who underachieved. METHOD Participants Participants in this study were the entire population (N = 153; 68 male, 85 female) of those identified as gifted in the graduating classes of 1990, 1991, and 1992 in an urban midwestern high school of approximately 1,500 students. In this school, junior high consisted of Grades

7-9 and high school of Grades 10-12. The socioeconomic information indicated that these students were from an essentially middle-class background, and all were White. These students had been identified for the gifted program according to district standards, which included qualifying on any two of the following four standardized measures; (a) a Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children Revised (Wechsler, 1974) score at or above 130, with 130 being at the 98th percentile; (b) a composite Otis-Lennon School Ability Test (Otis & Lennon, 1989) score at or above 132, with 132 being at the 98th percentile; (c) a composite score on the Stanford Achievement Test (Psychological Corporation, 1988) at or above the 95th percentile; and (d) at least one subtest score on the Stanford Achievement Test at or above the 95th percentile in the areas of vocabulary, reading, concepts of numbers, science, social studies, or language. In this school district, gifted underachievers were not particularly identified for special support services, alternative curricula, or involvement in programming for gifted students during kindergarten through Grade 9, although several had met the criteria for identification as "gifted," and some of those had participated in the pullout gifted program in earlier grades. From 1985 to 1990, screening procedures were established at the high school level to find underachievers who qualified, according to the criteria, and invite them to participate in a non-pullout menu-type program, in which students voluntarily selected options for short- and long-term involvement and received no credit for participation. Various after-school activities and short courses were offered to accommodate and extend interests and talents in a number of academic and interest areas. Advanced courses in the curriculum and Advanced Placement courses were open to all students, including underachievers. Instruments School records. The following information, available in the school files, was examined: gender; attendance and tardiness records; required and selected courses; semester grades, 7l2; grade point average (GPA) at graduation; and score on the American College Testing (ACT) Program (1993). ACT scores. The ACT Program, the second-most widely used test for college admissions, is a curriculum-based standardized test that measures academic achievement (ACT Technical Manual, 1988). The ACT scores were available for 145 (95%) of the 153 students in this study and offer a criterion for comparison of achievement. Internal-consistency reliability coefficients for the ACT range from .84 to .93 for the four individual test scores and from .94 to .96 for composite scores. Alternate-form reliability coefficients for the individual test scores range from .72 to .85 (adjusted for standard deviations), and for the composite the values range from .86 to .90 (ACT Technical Manual, 1988). Extensive information is provided supporting content-related, criterion-related, and construct-related validity for the ACT (ACT Technical Manual, 1988). Procedure The school file for each of the 153 gifted students was reviewed, and basic information was recorded and tabulated. Before the review of each file, four achievement categories were defined. The gifted achievers were those students identified for the gifted program who graduated with a GPA 3.35 (on a 4-point scale). These achievers were subdivided, based on graduation GPA, into high achievers (HA), GPA 3.75, and moderate achievers (MA), GPA = 3.35-3.74. The gifted underachievers were those students selected for the gifted program and graduating with a GPA < 3.35. These underachievers were subdivided, based on graduation GPA, into moderate underachievers (MU), GPA = 2.75-3.34, and extreme

underachievers (EU), GPA < 2.75. In terms of approximate percentile ranks in their graduating class, based on GPA, the high achievers were ranked from 90 to 100, the moderate achievers from 75 to 89, the moderate underachievers from 50 to 74, and the extreme underachievers below 50. These four achievement categories (HA, MA, MU, EU) were used for most comparisons. In addition to required courses, there were a number of courses that could be selected by students. Elective courses were designated as either academically "demanding electives" (typically taken by college-bound students) or academically "undemanding electives" (typically not taken by college-bound students). There were a total of 12 semesters (2 semesters for each grade, 7-12) examined in the school files. Any student who earned a GPA below 3.35 was categorized as an underachiever for that semester. Underachievement by semester was organized into three types. Chronic underachievement was defined as 9 to 12 semesters of underachievement, sustained underachievement as 5 to 8 semesters, and episodic underachievement as 1 to 4 semesters. A category of "onset" of underachievement also was determined. For all participants who graduated as underachievers, onset was determined to be the first semester of underachievement (i.e., GPA < 3.35) recorded during Grades 7 to 12. The data gathered, categorized, and analyzed were used to answer the following research questions: 1. Among gifted underachievers, which type (chronic, sustained, or episodic) of underachievement is most prevalent? 2. Do gifted achievers experience semesters of underachievement? 3. Are there patterns regarding onset and improvement of underachievement? 4. Are there patterns regarding areas where achievement is maintained during periods of underachievement? 5. Are there differences between gifted achievers and underachievers regarding attendance and tardiness? 6. Are there differences between gifted achievers and underachievers regarding their selection of demanding and undemanding courses? 7. Are there differences between gifted achievers and underachievers regarding performance on a standard achievement test used for college entrance? The data that were used to answer these questions were readily accessible, available for almost all students, and appropriate for statistical analysis. It was decided that data concerning marital status of parents, birth order, blended families, and size of family, although collected, would not be statistically analyzed, because it was apparent that such information had not been consistently recorded in the files. Anecdotal disciplinary reports and psychological reports also were omitted from the study because they were not consistently included in the files of students who had moved into the district. A history of each student's scores on standardized achievement and ability tests was not included for comparative analysis because a wide variety of tests had been taken by students who had moved from district to district. In addition, the files of many students did not contain a complete collection of scores.

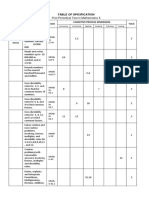

RESULTS Of the 153 gifted students, 85 (56%) were female and 68 (44%) male. An analysis of the school files indicated that 104 (68%) graduated as achievers (36 male, 68 female) and 49 (32%) as underachievers (32 male, 17 female). Male students were divided almost equally between achievers and underachievers (53% vs. 47%, respectively). Of female students, 80% were achievers. Like achievers and underachievers in general, the two extreme groups, HA (high achievers) and EU (extreme underachievers), were opposite in gender distribution, with HA 75% female and EU 75% male. The relatively large number of female HA (48 of 64) and the small number of female EU (4 of 16) placed a limitation on statistical analysis of gender differences. See Table I for comparisons by achievement category and gender. Most achievers had well above a 3.0 GPA, or B average, and most underachievers were well below 3.0, even though the cutoff for underachievement was 3.35. In fact, 94 achievers (91%) were at or above 3.5, and 26 underachievers (53%) were at 2.85 or below, with 4 below 2.0. Of the total population, 58% achieved below a 3.75 final GPA, the approximate 90th percentile, noteworthy when considering that all had met stringent criteria in the identification process. Female achievers (M = 3.82) were significantly higher, t(102) = -3.11, p < .01, than male achievers (M = 3.71) in GPA. Female underachievers (M = 2.93) were not significantly different from male underachievers (M = 2.75). In the total population, female students (M = 3.64) were significantly different from male students (M = 3.26) in GPA, t (151) = -4.84, p < .001. Duration of Underachievement There was evidence of uneven achievement in all achievement categories, that is, a pattern of one or more semesters of achievement followed by one or more semesters of underachievement. In the sample, 54% experienced at least one semester of underachievement, including 33% of those graduating as achievers. More female (n =15 or 18%) than male (n = 9, or 13%) students experienced episodic underachievement. More male (n = 27, or 40%) than female (n =16, or 19%) students experienced sustained or chronic underachievement. Most (69%) of the underachievers in the sample were chronic underachievers, and male students accounted for 76% of the chronic underachievers. In fact, 21 male students (31%) versus 2 female students (2%) underachieved for all 12 semesters. See Table 2 for a summary of duration of underachievement. Onset Junior high was a time of academic vulnerability, with Grade 7 showing the greatest number of students underachieving (n= 56, 37% of the study population, 75% of underachievers). Twenty-five (45%) of the 56 continued to underachieve for all subsequent semesters. Thirtytwo (57%) of the 56 were still underachieving in Grade 12, although some had experienced some periods of achievement. In addition to the 36 underachievers with low grades in Grade 7, 11 began to underachieve during Grades 8 and 9. Grade 7 was the only time of underachievement for 3 achievers. For 9 achievers, including those 3, underachievement occurred only during Grade 7 or 8 or both. During Grade 7, many more male (n = 44, or 65%) than female (n = 11, or 13%) students underachieved. A majority (91%) of male students graduating as underachievers were already underachieving during Grade 7, compared with 41% of female underachievers. Of the female

students graduating as underachievers, 39% began to underachieve during Grades 8 and 9, compared with 6% of male underachievers. Decline of Approximately One Grade Point or More After Grade 7 The evidence reported in Table 2 indicates that approximately one third (33%) of the achievers experienced semesters of underachievement. A question of concern was whether the decline in achievement was as dramatic for achievers as for underachievers. It was determined that a drop of one grade point or more (e.g., from A to B or A to C in overall GPA for a semester) would represent a dramatic decline and would be a standard for comparison. When there was underachievement, there was a decline of one grade point or more in more underachievers (47%) than achievers (32% of achievers who underachieved at least one semester). This indicates that although underachievers and some achievers both had semesters of underachievement, the degree of underachievement was greater for underachievers. For some underachievers, achievement was already below the 75th percentile, and then there was a marked further decline. However, 9 (18%) of the underachievers declined dramatically from all or mostly A grades during junior high. Nine chronic underachievers were A students at least 1 year during junior high. All grade levels carried the potential for at least momentary decline, even for achievers. Improvement in Achievement of Approximately One Grade Point or More No improvement in junior high was sustained for any underachiever. However, 27 who underachieved in Junior high became achievers at some time in high school. Eighteen students, 9 achievers (5 male, 4 female) and 9 underachievers (5 male, 4 female) made improvement of as much as one grade point or more after a period of underachievement. Sustained Achievement for Underachievers Of the 34 achievers who experienced underachievement, 19 continued to achieve in one or more academic areas during their decline. By contrast, 32 of 49 underachievers did not perform well in any academic area during periods of underachievement. However, 7 (14%) of the underachievers did continue to maintain an A average in one area. Science was the predominant subject area in which achievers maintained achievement during episodic underachievement. No particular area stands out for underachievers. Considering the total sample, more female than male students continued to achieve both in the humanities (29% vs. 8% of those who underachieved) and in math and science (20% vs. 13%). Attendance and Tardiness Achievers and underachievers differed significantly in average attendance, t(151) = -3.21, p < .01, and tardiness, t(151) = -6.36, p < .001, per year, with underachievers absent and tardy more often than achievers (see Table 3). EU were significantly different (p < .05) from all other groups and were the most variable. Among achievers, 17% had 10 or more absences per year, compared with 37% of underachievers. The difference in tardiness was even more clear: 5% of achievers had 5 or more reports of tardiness per year, compared with 35% of underachievers. Among underachievers only, female students were absent more often than male students, t(47) = -2.67, p < .01. For EU, female students were tardy more often than male students, t(14) = -2.38, p < .05. Course Selection "Demanding electives" were academic courses considered appropriate for college-bound

students in foreign language, language arts, social studies, mathematics, and science. "Undemanding electives" were typically not taken by the college-bound students, for example, Singles Living, Health Careers, Social Awareness, Personal Finance, basic art courses, Auto Mechanics, and Developmental Reading. There was a significant difference, t(151) = 7.68, p < .001. between achievers and underachievers in number of demanding electives chosen, with a wide range within each group. Achievers chose an average of 13.74 (range = 6-20) demanding electives during Grades 7 through 12, and underachievers chose an average of 9.20 (range = 3-17). In the total population, the mean of demanding electives chosen by female students (13.00) was significantly different, t(151) = -2.50, p < .05, from the mean for male students (11.40). The mean difference between the extreme groups, HA and EU, was striking, 14.41 versus 6.88. Thirty HA (47%) took 15 or more demanding electives, with 3 taking 20. None took 5 or fewer. Only 4 EU (25%) chose 10 demanding electives or more, and 7 EU (38%) chose 5 or fewer demanding electives. The difference between means for all achievers (1.19) and all underachievers (2.31) in number of undemanding electives chosen was relatively small but significant, t(15l) = -4.01, p < .001. There were no differences by gender within achiever and underachiever groups. However, in the total population, male students (M = 1.99) took significantly more, t(151) = 2.94, p < .01, undemanding electives than female students (M = 1.20). See Table 3 for comparisons regarding course selection. DISCUSSION Results of this study indicate that school records for students in Grades 7 through 12 do contain information that can assist counselors and others in understanding, and planning interventions for gifted students. The results point to clear differences between gifted achievers and gifted underachievers in regard to attendance and tardiness, course selection, and duration of underachievement. In addition, there were several instances of gender differences. The relatively high incidence of underachievement among male students and of high achievement among female students, as well as the significance of Grade 7 for male underachievers, was particularly noteworthy. Of the secondary school years analyzed in this study, it was evident that the junior high years, Grades 7 through 9, were the most critical regarding underachievement, and that patterns of achievement did not change when students entered high school in Grade 10. When GPA was used as the standard of achievement, gifted female students were higher than gifted male students across all four achievement categories (HA, MA, MU, and EU). However, when ACT percentiles were used as the standard, the opposite pattern emerged, with gifted male students higher across all four categories. This is consistent with current research (e.g., American College Testing, 1993). It seems that female students displayed the kinds of behaviors that are rewarded in classroom achievement, such as completion of assignments and studying for tests. Male students were more adept at showing mastery of the curriculum on standardized tests. It should be noted, however, that only among achievers were gender differences statistically significant. One stereotypic belief is that gifted students learn the curriculum whether or not they receive good grades. This study showed that those who achieved did better on the ACT than those who underachieved. Lower scores on tests used for college admission may represent one price underachievers pay for lower class performance and for taking fewer demanding

electives. Such tests may represent a formidable challenge to those with poor academic records, and lower scores may reflect their loss of faith in their academic competence, as suggested by Rimm (1986). However, it should be noted that, although underachievers here were below the 75th percentile in class rank and extreme underachievers were below the 50th percentile, the mean score of underachievers was still at the 87th percentile on the ACT, using national norms. The ACT may represent to the students a chance to prove themselves to a system in which they have not done well academically. Counselors might be heartened by the fact that indeed these students have learned the curriculum better than their grades indicate, and that ACT scores still allow them to compete adequately for admission to many colleges. Although there have been serious attacks on standardized testing in recent years, especially as to its potential bias regarding gender and ethnicity, such measurement appears to be a "savior" in documenting learning among gifted underachievers, especially male students. Even though every grade (7-12) represented the onset of underachievement for a number of students, it is evident from this study that junior high is the critical time at the secondary level for patterns of underachievement to become established. Because no letter grades were given before Grade 7 in this school district, it cannot be determined how significant the transition to junior high was to the decline in achievement. However, this study documents that the transition to high school generally did not contribute to either decline or improvement. Thus, for counselors, the focus on changing patterns of underachievement needs to be before high school and, probably, before junior high school. The data suggest that male students are more likely than female students to become extreme underachievers, and that most underachievers are chronic underachievers. The long duration of underachievement for so many may reflect complex systemic factors or student characteristics, rather than relatively short-term situations, particular teachers, or lack of skills or interest in particular courses. It also might reflect habit formation or cognitive style. For those students who underachieved early but became achievers by graduation, perhaps developmental issues, family conflict, or family transitions affected achievement negatively for a time during early adolescence, with improvement occurring when those issues were resolved. It is also important to note that even successful gifted students may have academic unevenness at the secondary level. However, the finding that one third of the achievers experienced, and recovered from, periods of underachievement suggests that established habits of achievement are sometimes able to withstand academic unevenness. Equally important, but not encouraging, is the fact that the majority of underachievers did not experience improvement during high school. Underachievement was well established during junior high for most of the underachievers. Given that the underachievers had met stringent ability requirements to qualify for this gifted program, it is important to recognize that, although they may have achieved even at C or D levels in the classroom, they were able to process information and grasp new material as nimbly as achievers, at least as measured by ability tests. When students underachieve, not only might they be missed when multiple measures are not used in identification procedures for gifted programs, but they also might be grouped in classes with students who have little in common with them intellectually, an occurrence that might contribute to negativity toward school. It is important as well for counselors and teachers to remember that grades, according to this study, may not reflect what has actually been learned: 20 underachievers, including 5

EU, had ACT composites at or above the 90th percentile. Low grades may be an indication of a problem but not a lack of intelligence. To "define" students by grades might not only misassess ability but might also affect their self-assessment negatively. Episodic underachievement also may lower the cumulative grade point enough for those who otherwise are achievers to be missed in identification for gifted programs. That so few underachievers maintained high achievement in a subject area suggests that, in most cases, the phenomenon of underachievement is global, with achievement level dropping in all academic work. Perhaps those who did continue to achieve in some course stayed open to being inspired by a specific teacher or to allowing high performance in an area of interest. They also may have had enough skills and resilience to sustain achievement in a certain area despite personal distress or a lack of concentration elsewhere. Students with either verbal or nonverbal deficiencies may have continued to achieve in the area of strength. The fact that so many of the achievers who underachieved at some point maintained high achievement in at least one area might reflect the literature about self-concept of ability being differentiated along subject lines (Marsh, 1992) and might have been critical to their regaining scholastic momentum later. This phenomenon of sustained achievement suggests that counselors might encourage teachers to be alert to the importance of their courses in maintaining equilibrium for underachieving students and to opportunities to offer emotional support. In addition, placement of at-risk gifted students with particular teachers or in areas in which they show special interest might help to sustain motivation enough to recapture general achievement. Absences and tardiness may represent passive resistance; Underachievers in this study averaged a much higher number of both absences and tardiness than did achievers. The gender differences for underachievers (i.e., female students were absent and tardy more often than were male students) suggest that female students may not have as many other options as male students do for expressing unhappiness, resistance to authority, or dissatisfaction with the school system in general. For female underachievers, noncompliance may be an important contributor to underachievement. The contrast between female HA and female EU in both attendance and tardiness suggests that these are distinguishing characteristics. Male HA and EU were not so discrepant. Parents, teachers, and counselors should be concerned about increases in absences and tardiness in both genders, but especially in female students. Frequent absences and tardiness may reflect personal problems, and absences may contribute to underachievement through lost instruction time and consequent negative interaction with teachers. McNabb and Grouse (1993) found that exposure to mathematics and science courses and good performance in those courses are associated with higher ACT scores in all subject areas. If underachievers generally do not take the most advanced courses available, their post-high school options may be limited. Whether because of poor self-concept, avoidance of challenge and competition, or fear of failure, they appear to avoid the demanding courses, beginning in junior high. The smaller achiever-underachiever difference regarding number of undemanding electives suggests that underachievers simply take fewer, not easier, courses compared with achievers, perhaps protecting an image of intelligence and guarding against boredom by avoiding undemanding courses. Their middle-class values also might have cautioned against taking courses beneath their ability (see Geen, Beatty, & Arkin, 1984, p. 248). The dilemma regarding undemanding electives for gifted students is that although the likelihood of success is greater in these courses, there is also potential for embarrassment if they do poorly. However, the fact that 4 EU took at least one advanced math course advocates for caution in making assumptions about underachievers. Perhaps the

underachievers who continued to choose demanding electives throughout school preferred to be around intellectual peers, even though they did not do what was required to earn high grades. Male and female students in each of the four achievement categories took a similar number of demanding and undemanding electives. However, it should be noted that female students took a slightly greater number of demanding courses and fewer undemanding courses compared with male students, not reflecting the literature regarding female students and course selection (e.g., Eccles & Harold, 1992). The earlier the improvement occurs, the better. When moderate levels of underachievement were altered during Grades 7 through 10, an uninterrupted achievement mode was eventually possible for 12 (35%) of the achievers who faltered early. The fact that 20% of those who graduated as underachievers improved dramatically during high school also supports the idea that later positive change can indeed happen, as it did for 2 chronic underachievers who experienced A-level work late in high school. As late as Grades 11 and 12, 10 students in the population made significant improvement. It is clear that underachievement may persist stubbornly, but school personnel and parents can have some optimism about change. Close monitoring of attendance and achievement patterns seems to be warranted in order to detect changes that might signal gifted children at risk, and in order that interventions can take place before habits of under-achievement are firmly established, perhaps even in late elementary grades, given the high incidence of underachievement, especially for male students, during Grade 7. The limitations of this study direct attention to two areas for future research. The fact that no letter grades were available for Grades 1 to 6 limited this study to achievement records from Grades 7 to 12. Research in school districts in which grades could be examined at all levels, kindergarten through Grade 12, could more certainly pinpoint time of onset of underachievement and could document other changes in level of achievement. The fact that the population of gifted students in this study was from a single high school with a relatively homogeneous population limits the generalizability of results. Future research in settings with more diverse populations, more reflective of national demographics, could determine whether the patterns found in this study are generalizable. Finally, concerning the incidence of improvement from patterns of underachievement to achievement, research might focus on the timing of problematic personal and family transitions, as evident in school records. CONCLUSION Gifted underachievers often do not fit the usual "at risk" categories, particularly if their grades are not extremely low, and therefore there may be little urgency about intervening. However, when highly intelligent adolescents are turned off by school or are struggling to stay involved during adolescent or family upheaval, their underachievement may represent great pain and frustration, not to mention loss of potential adult productivity. Continued research is needed to enhance the understanding of both contributing factors and possible interventions. Counselors and educators of the gifted may benefit greatly by insights into the complex phenomenon of underachievement, and they, in turn, might be able to offer and use strategies for nudging underachievers into productivity. Jean Sunde Peterson is an assistant professor of counselor preparation at Northeast Missouri State University. Nicholas Colangelo is a professor of counselor education at the University of Iowa. Correspondence regarding this article should be sent to Nicholas Colangelo. The Connie Belin and Jacqueline N. Blank International Center for Gifted Education and Talent Development, University of Iowa, 210 Lindquist Center, Iowa City, IA 52242.

Você também pode gostar

- The Epistle of Paul To The RomansDocumento25 páginasThe Epistle of Paul To The RomansjbfellowshipAinda não há avaliações

- Gifted StudentsDocumento15 páginasGifted StudentsAngélica MarquezAinda não há avaliações

- Interventions That Work With Special Populations in Gifted EducationNo EverandInterventions That Work With Special Populations in Gifted EducationAinda não há avaliações

- HIPPO 2022: HIPPO 5 / S15 Use of English TestDocumento2 páginasHIPPO 2022: HIPPO 5 / S15 Use of English Testadnen ferjani83% (6)

- The Problem and Its BackgroundDocumento20 páginasThe Problem and Its BackgroundRuth Sy100% (2)

- The Influence of Parental and Peer Attachment On College Students' Academic AchievementDocumento13 páginasThe Influence of Parental and Peer Attachment On College Students' Academic AchievementUyên BíchAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To Asset-Backed SecuritiesDocumento5 páginasIntroduction To Asset-Backed SecuritiesShai RabiAinda não há avaliações

- 1st Summative Test in Math 5Documento14 páginas1st Summative Test in Math 5Errol Rabe SolidariosAinda não há avaliações

- Q 5Documento3 páginasQ 5Hasani Hasan0% (1)

- I01 Macbeth Analysis 2023Documento6 páginasI01 Macbeth Analysis 2023Miranda BustosAinda não há avaliações

- Basic Principles of TaxationDocumento22 páginasBasic Principles of TaxationJacq CalaycayAinda não há avaliações

- Baumann Skin Type Indicator-A Novel Approach To Understanding Skin TypeDocumento13 páginasBaumann Skin Type Indicator-A Novel Approach To Understanding Skin TypeHendro Dan MithochanAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 2-Rrl and StudiesDocumento7 páginasChapter 2-Rrl and Studiesanon_25686725567% (3)

- 5 6334652320046907615 PDFDocumento267 páginas5 6334652320046907615 PDFchethan mahadevAinda não há avaliações

- AbsenteeismDocumento10 páginasAbsenteeismapi-341275251100% (2)

- Dissecting Anti-Terror Bill in The Philippines: A Swot AnalysisDocumento15 páginasDissecting Anti-Terror Bill in The Philippines: A Swot AnalysisAdie LadnamudAinda não há avaliações

- Classical Guitar - History - I.four Course GuitarDocumento3 páginasClassical Guitar - History - I.four Course GuitarPrasetyaJayaputraAinda não há avaliações

- Pr1-Chapter IiDocumento15 páginasPr1-Chapter IiArianne BenitoAinda não há avaliações

- Underachieving LearnersDocumento19 páginasUnderachieving LearnersDavid Barton0% (1)

- Derasin Final4Documento23 páginasDerasin Final4Valdez FeYnAinda não há avaliações

- Research MethodsDocumento17 páginasResearch MethodsJeny Calderon Bucog BacquialAinda não há avaliações

- International Journal of Educational Research: Richard Sheldrake, Tamjid Mujtaba, Michael J. ReissDocumento13 páginasInternational Journal of Educational Research: Richard Sheldrake, Tamjid Mujtaba, Michael J. ReissmahadbulabAinda não há avaliações

- "School Is So Boring": High-Stakes Testing and Boredom at An Urban Middle SchoolDocumento9 páginas"School Is So Boring": High-Stakes Testing and Boredom at An Urban Middle SchoolAaron SantosAinda não há avaliações

- Fourth Grade SlumpDocumento3 páginasFourth Grade Slumpapi-264199862Ainda não há avaliações

- Padilla, Et Al 2022Documento16 páginasPadilla, Et Al 2022Carmen Espinoza BarrigaAinda não há avaliações

- Promoting Reading Achievement and Countering The Fourth Grade Slump The Impact of Direct Instruction On Reading Achievement in Fifth GradeDocumento24 páginasPromoting Reading Achievement and Countering The Fourth Grade Slump The Impact of Direct Instruction On Reading Achievement in Fifth GradeAndres SanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Research PDFDocumento20 páginasResearch PDFZayn MendesAinda não há avaliações

- Children With LD Within The Family ContextDocumento9 páginasChildren With LD Within The Family ContextDimitris ParwnhsAinda não há avaliações

- RRLDocumento3 páginasRRLAaron AndradaAinda não há avaliações

- Implicit 20 Theories 20 of 20 Intelligence 20 Predict 20 Achievement 20 Across 20 An 20 Adolescent 20 TransitionDocumento19 páginasImplicit 20 Theories 20 of 20 Intelligence 20 Predict 20 Achievement 20 Across 20 An 20 Adolescent 20 Transitiondquartulliarchivos20 QAinda não há avaliações

- Cdev 12802Documento23 páginasCdev 12802andreadriansyahAinda não há avaliações

- AbsenteeismDocumento15 páginasAbsenteeismapi-353133426Ainda não há avaliações

- Effectiveness of Double Bubble Thinking Maps in Reading Comprehension: A 5th Grade Classroom Lesson StudyDocumento44 páginasEffectiveness of Double Bubble Thinking Maps in Reading Comprehension: A 5th Grade Classroom Lesson Studyapi-545086921Ainda não há avaliações

- Final Lesson Study Paper - DiazDocumento41 páginasFinal Lesson Study Paper - Diazapi-546411955Ainda não há avaliações

- Review of LiteratureDocumento3 páginasReview of LiteratureMarian AbaoagAinda não há avaliações

- Read 650 Literature ReviewDocumento9 páginasRead 650 Literature Reviewapi-400839736Ainda não há avaliações

- Implicit Theories of Intelligence Predict Achievement Across An Adolescent TransitionDocumento18 páginasImplicit Theories of Intelligence Predict Achievement Across An Adolescent TransitionClarissa NiciporciukasAinda não há avaliações

- Thesis ProposalDocumento13 páginasThesis ProposalUrsonal LalangAinda não há avaliações

- Afterschoolarticle 2Documento16 páginasAfterschoolarticle 2api-455217333Ainda não há avaliações

- Uas Abstract PGSDDocumento16 páginasUas Abstract PGSDhaerul padliAinda não há avaliações

- Academic Performance, Effects of Socio-Economic Status On Brandon L Carlisle and Carolyn B Murray, University of California Riverside, Riverside, CA, USAÓ2015 Elsevier Ltd. All Rights ReservedDocumento8 páginasAcademic Performance, Effects of Socio-Economic Status On Brandon L Carlisle and Carolyn B Murray, University of California Riverside, Riverside, CA, USAÓ2015 Elsevier Ltd. All Rights ReservedSarcia RafaelAinda não há avaliações

- Academic Trajectories of Newcomer Immigrant YouthDocumento17 páginasAcademic Trajectories of Newcomer Immigrant YouthEka CitraAinda não há avaliações

- AbsentisimDocumento9 páginasAbsentisimapi-343696057Ainda não há avaliações

- Weebly ArticleDocumento22 páginasWeebly Articleapi-315662328Ainda não há avaliações

- Not Just RoboStudents Conner Pope - PDF FinalDocumento17 páginasNot Just RoboStudents Conner Pope - PDF FinalKQED NewsAinda não há avaliações

- Setting by Ability - or Is It. A Quantitative Study of Determinants of Set Placement in English Secondary SchoolsDocumento18 páginasSetting by Ability - or Is It. A Quantitative Study of Determinants of Set Placement in English Secondary SchoolsAnonymous 09S4yJkAinda não há avaliações

- Self EsteemDocumento10 páginasSelf EsteemGiorgos Xalvantzis100% (1)

- Lane - Academic Achievement of K-12Documento16 páginasLane - Academic Achievement of K-12Nikko LimuaAinda não há avaliações

- Parental Influences On Academic Performance in African-American StudentsDocumento10 páginasParental Influences On Academic Performance in African-American Studentsزيدون صالحAinda não há avaliações

- 2019 - Psikopend - Relationships Between Positive Parenting GritDocumento15 páginas2019 - Psikopend - Relationships Between Positive Parenting GritMaria SutarjaAinda não há avaliações

- Review of Related LiteratureDocumento14 páginasReview of Related LiteratureMatthew OñasAinda não há avaliações

- Reinke 2008Documento12 páginasReinke 2008EmmanuelAinda não há avaliações

- Literature Review Foreign Literature Student PerformanceDocumento3 páginasLiterature Review Foreign Literature Student PerformanceCuasay, Vernelle Stephanie De guzmanAinda não há avaliações

- In This Issue: Child Development, July/August 2014, Volume 85, Number 4, Pages 1323 - 1329Documento7 páginasIn This Issue: Child Development, July/August 2014, Volume 85, Number 4, Pages 1323 - 1329hirsi200518Ainda não há avaliações

- Risk Factors and Levels of Risk For High School Dropouts: Suhyun Suh Is AnDocumento10 páginasRisk Factors and Levels of Risk For High School Dropouts: Suhyun Suh Is AnCristhian AndresAinda não há avaliações

- Learners' PerceptionsDocumento36 páginasLearners' PerceptionsAsh KeyAinda não há avaliações

- Late Talkers: A Population-Based Study of Risk Factors and School Readiness ConsequencesDocumento20 páginasLate Talkers: A Population-Based Study of Risk Factors and School Readiness ConsequencesEssa BagusAinda não há avaliações

- Giftedness and IclusionDocumento19 páginasGiftedness and Iclusionmauricio gómezAinda não há avaliações

- Intensive Remedial InstructionDocumento27 páginasIntensive Remedial InstructionRita NoitesAinda não há avaliações

- Retrospective Analyses of The Reading Development of Grade 4 Students With Reading DisabilitiesDocumento15 páginasRetrospective Analyses of The Reading Development of Grade 4 Students With Reading DisabilitiesAntónia MarinhoAinda não há avaliações

- Study Skills of Normal-Achieving and Academically-Struggling College StudentsDocumento16 páginasStudy Skills of Normal-Achieving and Academically-Struggling College StudentsSamAinda não há avaliações

- School Stab Lit RevDocumento9 páginasSchool Stab Lit RevGLADYS GADIANOAinda não há avaliações

- Research Paper On Students With DisabilitiesDocumento7 páginasResearch Paper On Students With Disabilitiesleukqyulg100% (1)

- Effects of Family Educational Background, Dwelling and Parenting Style On Students' Academic Achievement: The Case of Secondary Schools in Bahir DarDocumento11 páginasEffects of Family Educational Background, Dwelling and Parenting Style On Students' Academic Achievement: The Case of Secondary Schools in Bahir DarAristotle Manicane GabonAinda não há avaliações

- Skip To Main Content: CHAPTER 2 Review of Related Literature and Studies Foreign Literature Student Performance GaliherDocumento5 páginasSkip To Main Content: CHAPTER 2 Review of Related Literature and Studies Foreign Literature Student Performance GaliherEljoy AgsamosamAinda não há avaliações

- Turner2009 PDFDocumento11 páginasTurner2009 PDFZahira MahdalyAinda não há avaliações

- Student-School Bonding and Adolescent Problem BehaviorDocumento10 páginasStudent-School Bonding and Adolescent Problem BehaviorJohny VillanuevaAinda não há avaliações

- The Impact of Parental Occupation and SoDocumento22 páginasThe Impact of Parental Occupation and SoJustine DeñadoAinda não há avaliações

- Academic Success and Failure: Student Characteristics and Broader Implications For Research in Higher EducationDocumento12 páginasAcademic Success and Failure: Student Characteristics and Broader Implications For Research in Higher EducationKenelyn CuestaAinda não há avaliações

- Absenteeism 2003Documento15 páginasAbsenteeism 2003Ann Mae BolivarAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 2Documento6 páginasChapter 2Frustrated LearnerAinda não há avaliações

- Understanding The Mystery: Weighing Cessationist and Continuationist Debate of Prophecy in The Pauline EpistlesDocumento88 páginasUnderstanding The Mystery: Weighing Cessationist and Continuationist Debate of Prophecy in The Pauline EpistlesDidedla;,Ainda não há avaliações

- Rizqy Ramakrisna GustiartoDocumento9 páginasRizqy Ramakrisna GustiartoMoe Channel100% (1)

- I Need My MonsterDocumento3 páginasI Need My Monsterapi-299779330Ainda não há avaliações

- MangubhaiDocumento211 páginasMangubhaiVaishnavi JayakumarAinda não há avaliações

- CC Project - Tarik SulicDocumento16 páginasCC Project - Tarik SulicTarik SulicAinda não há avaliações

- A New Fracture Mechanics Theory of Wood Extended Second EditionDocumento253 páginasA New Fracture Mechanics Theory of Wood Extended Second EditionDerek FongAinda não há avaliações

- (Gary D. Rawnsley, Ming-Yeh T. Rawnsley) Global CHDocumento253 páginas(Gary D. Rawnsley, Ming-Yeh T. Rawnsley) Global CHmercegonzalez5073Ainda não há avaliações

- Management Review Datasheet - ComplianceQuestDocumento5 páginasManagement Review Datasheet - ComplianceQuestCompliance QuestAinda não há avaliações

- Cross Courses Feb 2024Documento1 páginaCross Courses Feb 2024larshhkAinda não há avaliações

- Personality Test Result - Free Personality Test Online at 123testDocumento15 páginasPersonality Test Result - Free Personality Test Online at 123testapi-650722264Ainda não há avaliações

- The Problem: Kuhliembo Festival Was Declared As The Official Festival of The Municipality BeingDocumento46 páginasThe Problem: Kuhliembo Festival Was Declared As The Official Festival of The Municipality BeingSamantha Angelica PerezAinda não há avaliações

- Sales Organization Structure and Sales Force Deployment: Module FourDocumento35 páginasSales Organization Structure and Sales Force Deployment: Module FourDeepankar MukherjeeAinda não há avaliações

- Eenadu EpaperDocumento1 páginaEenadu EpaperRamprasad AkshantulaAinda não há avaliações

- Forward Kelas Xi Kikd 2017-Unit 6Documento25 páginasForward Kelas Xi Kikd 2017-Unit 6agus mrAinda não há avaliações

- REVIEW hk2 Grade 3Documento9 páginasREVIEW hk2 Grade 3Minh PhamAinda não há avaliações

- Setting Notes - AP Short StoryDocumento2 páginasSetting Notes - AP Short StoryRyanGoldenAinda não há avaliações

- Curriculum and SyllabusDocumento107 páginasCurriculum and SyllabusfortunatesanjAinda não há avaliações

- Vaisnava - KeDocumento75 páginasVaisnava - KepriyankasabariAinda não há avaliações

- Thomas W.hungerford, AlgebraDocumento1 páginaThomas W.hungerford, AlgebraJoan Tamayo RiveraAinda não há avaliações