Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Bonsai in Three Years: A Beginner's Guide

Enviado por

alejandrorubilarDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Bonsai in Three Years: A Beginner's Guide

Enviado por

alejandrorubilarDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Bonsai in Three Years: A Beginner's Guide by Zach Smith Special to the Greater New Orleans Bonsai Society--Lecture-demonstration, September

11, 1990 (This article later appeared in Bonsai: Journal of The American Bonsai Society, Summer 1990, Volume 24, Number 2, Pages 8 - 10.) On January 1, 1987, I had fewer than five trees in training for bonsai. A youthful interest in bonsai had been rekindled by a Christmas present of a poorly designed (undesigned, actually) green mound juniper. Subsequently, I have collected or propagated several hundred trees, mostly for sale, which has allowed me to select a fair number of very nice specimens for inclusion in the collection I am building. I have no tree in my collection today which has been in training for more than three years. In a three-year span of time (often less), however, it is possible to reach a point of development with your bonsai so that what remains is only refinement--pinching and occasional light pruning. The secret to this is simple: acquire good-quality material and take the proper steps in its development. There is nothing facetious in such a recommendation because I have done it myself, and I possess no special talent or knowledge. Acquire good-quality material and take the proper steps in its development. I have had occasion to examine many bonsai, at club meetings and elsewhere, which have been in training for quite some time without getting very far. Sometimes the material is not very good, but more often the artist has not taken the proper steps in training his or her bonsai. Here are some of the most common mistakes that retard development of bonsai: 1. Immediate potting of small material. Placing a rooted cutting or small stock plant direclty into a bonsai container insures one thing--slow growth. I think this mistake most often originates from the mindset that bonsai are dwarfed tree which stay small and grow slowly. Fully developed bonsai are indeed dwarfed trees which stay small and grow quite slowly. Bonsai-in-training are not dwarfed trees, and they should not grow slowly. Trunk and branch development require vigorous growth. Also, when I see material potted too soon into bonsai containers, it almost invariably is potted in the wrong type of soil, most often potting soil from the local general-trade nursery. These soils are not suited to use in bonsai containers, as they compact quite rapidly under the frequent rate of watering required for bonsai. The result is gradual suffocation of the tree's roots and sluggish growth (or none at all). 2. Using refinement techniques on bonsai or stock plants that are not properly developed. Pinching growth on a piece of undeveloped raw material provides ramification, nothing more. When developing bonsai, pinching of new growth should only be used to redirect vigor--to "cool off" the growth in an area of the tree that is too strong relative to the rest. 3. Poor horticultural practice. Even if you have resisted the urge to pot your stock into a bonsai container, the use of a soil which does not drain cannot do much but slow the growth of your trees. Weakening them in this manner makes them more susceptible to pests and diseases, and an especially harsh winter will probably kill them. Inadequate sunlight causes leggy growth, and long weak shoots with huge internodes. Sunlight is essential to food manufacture--do not think that when you feed your trees they have had dinner. All you have provided is the building blocks with which the trees make their own food. 4. Doting on your trees. You study your trees daily, and it is not uncommon for even experienced artists to find little faults each time. The beginner, however, often makes the mistake of correcting those little faults each time. He wires a branch one day and bends it; next day, the angle is not quite right, so he bends it a little more; next day, he decides the original angle was best after all, so back it goes. Next day, the branch dies. In my experience, plants can only take so much love and attention. The one thing you can safely do to your bonsai each and every day is water them. You can pinch the vigorous growers every few days or so, fertilize every week, lightly prune/thin branches and wire every month or so, remove major branches

every half-year or so, and drastically prune once a year. More is not good for the trees, and it only makes you feel better temporarily, since ultimately it slows development of your bonsai. With these common mistakes explained, here are my few cardinal rules for bonsai stock development which, while not insuring success by the beginner, certainly will improve the odds: 1. Get lots of trees. This will virtually cure mistake Number 4 above, as it's hard to dote on a hundred plants--unless you're retired with lots of time to bother them. Why lots of trees? I have found that the amount you learn about bonsai, and speed at which you learn it, are direclty proportional to the number of trees you are working on. If you ruin or kill twenty out of a hundred trees, you have eighty left to benefit from what you have learned (and they will be scared to death, so will respond more willingly). If you start with five trees and ruin or kill them all, you have to start over, losing precious time in the process. Also, if you want a collection of fifty nice trees, the chances are infinitesimal that your starting off with fifty trees for training will give you the result you want. Some will die and others you will find are not good enough material after all. If you work on five hundred trees over a span of ten to fifteen years, I can almost guarantee you will end up with fifty trees to be proud of--but not five hundred. 2. Start with easy species, those which grow and develop vigorously. Do not try learning bonsai on such species as pine, beech, oak, dogwood, etc. I can almost guarantee frustration and disappointment. Try instead such wonderfully agreeable species as Chinese or oval-leaf privet, American elm, hackberry, Chinese sweetplum, water-elm, green mound juniper, Chinese elm, etc. Ask your local experts for recommendations. Except for the juniper, each of these species will backbud regardless of how drastically you prune it. 3. Try to buy as few finished bonsai as possible. Except for their sprucing up the back yard, you learn little by looking at someone else's work. 4. Learn how to collect trees. You will find eventually that the best, fastest way to grow bonsai with good trunk thickness is to start with trees that have good basal trunk thickness (one inch and more). Collected trees have an appeal all their own. They do not, however, save any time as far as bonsai development goes--it will still take about three years to get the branches properly developed. But a bigger trunk always looks better on a bonsai in whatever stage of training. It is a bit hard to explain in this short space how to collect trees, but I suggest that in the beginning you collect only in spring. Later, when your skills are more advanced, you can expand your collecting to most of the other months (depending, of course, on the species). Your success rate in the early stages will probably range from thirty to fifty percent. Later you should expect up to eighty percent. Remember that when you are collecting deciduous and most broadleaf evergreen trees, all you are interested in is the shape, quality and taper of the trunk. The rest can be grown later. 5. If you cannot collect or afford large stock, plant your small stock in the ground or in greatly oversized containers. This will give you the rapid growth necessary for trunk thickening. Drastically prune the tree each year and let it regrow without any additional pruning. You can wire the trunk initially if you like, but I believe you will discover a more original, less-contrived design in about three years just through your pruning and regrowth work. If you are able to plant your stock in the ground, I suggest root pruning it every second year just to keep the roots from getting too far out of bounds. Trees secure their survival by sending their roots far and wide in search of nutrients. Although you can in effect "collect" the stock from your growing area when it's reached suitable size, you will save some trouble by root pruning periodically. 6. Fertilize your trees. This is probably the most easily neglected task the bonsai artist faces. And do not skimp. Experiment with the fertilizer(s) you have chosen until you are giving just as much as the tree can

stand. Again, our mindset is to feed bonsai at reduced fertilizer strength, according to the conventional wisdom. Even most bonsai should be fed as much as other ornamentals, because of the rapid leaching of nutrients from necessarily porous bonsai soils. Your stock plants, which you are eager to develop just as quickly as you can, must have all the nutrients they will take. Which fertilizer should you use? There are hundreds of recipes to be found in the literature. I alternate organics such as blood and bone meal with liquids such as Miracle Gro patio plant food, a 20-20-20 fertilizer. The organics I usually spoon onto the soil surface until it looks like I have given enough; when they have pretty much disappeared from the soil surface, I give more. The liquid I use at full strength. Be sure to keep your soil pH in the acid range for those species which need an acid soil (most of them), since nutrients are "locked up" under alkaline conditions. If you are getting enough rainfall this will not be a problem; if you get into a drought of two weeks' duration or more, you will have to acidify your soil. I do this by mixing one to one and a half tablespoons of white vinegar per gallon of water, then watering the trees. This solution has a pH of about 4.5 to 5.0, which is sufficient to lower the soil pH without damaging the trees in the process. One other advantage of using vinegar, or acetic acid, is that it is an organic acid and will not cause salt build-up when used over time. 7. Read everything on the subject of bonsai you can manage to get your hands on. The only qualifier is, do not substitute reading for doing. Read the books and articles, and if you see a technique you would like to try by all means try it. This is the only sure way to learn. 8. Attend your club meetings. Often we get myopic, staying holed up in our own back yards and doing things to our trees without benefit of seeing the work of others. Think of club meetings as crosspollination. Do not be self-conscious about your trees--each of us has bonsai that are not very good. We tend to be a bit defensive about our prize creations, but in my experience bonsai people are not malicious, and almost to a person are eager to help you figure out the problem(s) with your bonsai. All you have to do is give them a chance. What about design? When most of us think of design in our early bonsai efforts we think of art (shudder). While many bonsai enthusiasts are indeed skilled artists in other fields, most of us are not. This is your bonsai. You must design it. Others will critically judge your work. With this sort of mindset, approaching that tangled mass of branches sitting in front of you would have to unnerve most anyone starting out. I would like to be able to say forget art and design, but that's a copout. What I would suggest, however, is that you try to put more of your efforts into learning technique when starting out. Learn how to thin branches by pruning. Learn how to wire and bend the trunk and branches. Learn what constitutes formal and informal upright, slanting style, broom style, cascade style. Study trees in nature and understand how they grow, then try to reproduce their structure on a smaller scale. When your trees are far enough along, learn how to prune and pinch for refinement. Repot your stock every second year so that you can learn root pruning and its effects. That said, here are a few suggestions for approaching bonsai design when you are getting started: 1. Stick with informal upright or slanting styles in the beginning. These are the easiest of the bonsai styles to execute. 2. Study trunk shapes in photos and in viewing others' bonsai; the trunk shape is the foundation for your design. Note that proper trunk design limits the number of directional changes in the lower half to twothirds of the trunk to three or four. More usually appears contrived. Also notice that movement of the trunk from front to back, as well as from side to side, is extremely important. By studying trunk shapes, you sharpen your skills when it comes time to pick stock at the nursery or choose trees to collect. 3. Let the tree do as much of the work as possible. Assuming your stock is of good size and quality, often a design will suggest itself to you as you study the tree. Take it. I have found that it is usually very difficult

to improve on nature's design gift. This is particularly true of collected material. Usually we collect trees because they have a certain something, a particular shape and character to the trunk. Why then take the tree home and try to manhandle it into something it is not? 4. With the trunk line understood and established, branch patterns become important to the best expression of your material. Starting at the one-quarter to four-tenths position up the trunk, begin your branching roughly on the outside of each curve, then alternate the branches around the trunk as you work your way to the apex of the tree. When you have wired and positioned each branch, put the tree on the floor and look at it from above; this will tell y ou immediately how good a job you've done on your branching arrangement (branches should not cover one another). What if you do not have the luxury of that perfect arrangement of branches? Ad lib. Seldom will you have a perfect arrangement of branches to work with anyway. The inexperienced artist compensates for this by worrying, the pro by adjusting the tree so that foliage masses end up roughly where we wanted branches to be (which is the real goal, after all). This is not cheating--in bonsai, the art of compromise is not the compromise of art. Often, perhaps even most of the time, the result is truly unique, and superior to what might have been a contrived-looking, perfectly branched tree. 5. Now prune your tree so that its lines conform roughly to the shape of a scalene cone, keeping the crown somewhat soft and rounded. 6. With all this done, leave the tree alone for awhile. Fertilize and water it, and let it grow out before doing any more trimming. Remember that trees must have periods of growth to build or rebuild their food reserves. This is especially critical as fall nears. This is hardly an exhaustive guide for creating bonsai when you just became interested last week, but perhaps it will help a bit. One thing to keep in mind is that mistakes, many terrible and some fatal (for the trees, not you), are the price of admission to the world of bonsai. Do not let fear of making a mistake stop you from doing anything at all, or nothing is just what the end result will be. The only bonsai growers who have never committed awful mistakes on any of their trees are the ones who have never grown any trees to begin with. These are the "going to be's." Going to go collecting. Going to be putting in that growing bed. Going to be working on those trees. Is patience a prerequisite for being able to create good bonsai? Contrary to popular belief, no one is all that patient when it comes to creating bonsai. I have never met anyone who said they wanted to wait twenty years for their bonsai to develop. Rather, everyone wants their trees to look great right away. We are patient out of necessity. The Japanese masters of old collected trees because they did not want to wait either. No, the most vital personal quality needed to create bonsai is perseverance. If you break a branch and give up, you'll never make good bonsai. If you style and pot twenty trees and do not like any of them, do twenty more--and twenty more, until you start to like them. Never give up. One day, I promise, you will style a tree, and when you are done you will stand back and feel an excitement about the tree; and the next day you will feel the same excitement about that tree, and the next as well. Artistry will have visited itself upon you. This is when all of the frustration and confusion will have been worth it. Finally, bonsai should not be regarded solely as a horticultural curiosity, or as a pleasant hobby, or even as an art. It is so much more, and I believe you will find, as you progress, that a kind of relationship develops between you and your trees. I hesitate to say that you understand one another, but perhaps on some crisp autumn evening, when the red, yellow and bronze leaves on your maples and elms and hornbeams begin to let go of their branchlets, the true wonder of bonsai will become a bit clearer.

Você também pode gostar

- 7 Biggest Mistakes Made When Growing A Bonsai TreeDocumento10 páginas7 Biggest Mistakes Made When Growing A Bonsai TreeStefanica M. Cazac0% (2)

- Bonsai: The Complete and Comprehensive Guide for BeginnersNo EverandBonsai: The Complete and Comprehensive Guide for BeginnersNota: 1 de 5 estrelas1/5 (1)

- Sunflower Production (Final) PPT - Compressed PDFDocumento27 páginasSunflower Production (Final) PPT - Compressed PDFMarijenLeaño86% (7)

- How To Make Organic Plant FoodDocumento6 páginasHow To Make Organic Plant Foodrajasekar_tceAinda não há avaliações

- Basic Bonsai CareDocumento2 páginasBasic Bonsai CareLuis Dias50% (2)

- 15 Best Profitable Plants 2016Documento56 páginas15 Best Profitable Plants 2016Jan Steinman100% (2)

- Bonsai Guide For The BeginnerDocumento21 páginasBonsai Guide For The BeginnerVidhyaa Saagar0% (1)

- Bonsai Tips PDFDocumento53 páginasBonsai Tips PDFtop20% (1)

- Types of Propagation and Classes of Plant PropagationDocumento20 páginasTypes of Propagation and Classes of Plant PropagationJuliet Cayao SajolAinda não há avaliações

- Beginner PackageDocumento30 páginasBeginner Packagespsubash4409100% (1)

- Bonsai Today Magazine Cont Ay Magazine Contents Fe - 5a2b72f71723ddfcdce1f15c PDFDocumento5 páginasBonsai Today Magazine Cont Ay Magazine Contents Fe - 5a2b72f71723ddfcdce1f15c PDFGiampaolo PastorinoAinda não há avaliações

- A Quick Fix BonsaiDocumento8 páginasA Quick Fix BonsaiNicolás Solano CondeAinda não há avaliações

- Bonsai for Beginners: The Essential Art and Guide of Growing and Taking Care of a Bonsai Tree. A Step-by-Step Guide from Basics to the Most Advanced Techniques to Make It Healthy and Long-LastingNo EverandBonsai for Beginners: The Essential Art and Guide of Growing and Taking Care of a Bonsai Tree. A Step-by-Step Guide from Basics to the Most Advanced Techniques to Make It Healthy and Long-LastingAinda não há avaliações

- Yamadori ARTS 344Documento5 páginasYamadori ARTS 344Ron GermanoAinda não há avaliações

- Selecting Containers For BonsaiDocumento9 páginasSelecting Containers For BonsaiAlessioMas100% (1)

- Ruth Morgans Beginners Guide To BonsaiDocumento24 páginasRuth Morgans Beginners Guide To BonsaiEalangi IonutAinda não há avaliações

- Byproducts From Sugarcane ProcessingDocumento72 páginasByproducts From Sugarcane ProcessingasokmithraAinda não há avaliações

- Bonsai: Complete Step by Step Guide on How to Cultivate, Grow, Care and Display your Bonsai TreeNo EverandBonsai: Complete Step by Step Guide on How to Cultivate, Grow, Care and Display your Bonsai TreeNota: 1 de 5 estrelas1/5 (1)

- Crop Rotation HandoutDocumento15 páginasCrop Rotation HandoutSolomon MbeweAinda não há avaliações

- VermicompostingDocumento47 páginasVermicompostingleolasty91% (11)

- JuniperDocumento4 páginasJuniperAndrei Voinea0% (1)

- Frankie Flowers Two-Book Bundle: Get Growing and Pot It UpNo EverandFrankie Flowers Two-Book Bundle: Get Growing and Pot It UpAinda não há avaliações

- Bonsai Serissa PDFDocumento1 páginaBonsai Serissa PDFDavid RiveraAinda não há avaliações

- A Beginner’s Guide to Planting a Garden: Gardening Tips, Techniques and Systems for planting the right herbs, Shrubs and Trees in Your Sustainable GardenNo EverandA Beginner’s Guide to Planting a Garden: Gardening Tips, Techniques and Systems for planting the right herbs, Shrubs and Trees in Your Sustainable GardenAinda não há avaliações

- 1 Jan 13 PDFDocumento8 páginas1 Jan 13 PDFAlejandroAinda não há avaliações

- How To Grow Miniature TreesDocumento20 páginasHow To Grow Miniature TreesLuis DiasAinda não há avaliações

- Bonsai: A Comprehensive Guide to Growing, Pruning, Wiring and Caring for Your Bonsai TreesNo EverandBonsai: A Comprehensive Guide to Growing, Pruning, Wiring and Caring for Your Bonsai TreesAinda não há avaliações

- Bonsai TipsDocumento12 páginasBonsai TipsAnonymous f4EtwSAinda não há avaliações

- National Geographic History MayJune 2017 VK Com StopthepressDocumento101 páginasNational Geographic History MayJune 2017 VK Com Stopthepresssumendapb100% (3)

- Maize Production AgronomyDocumento4 páginasMaize Production AgronomySsemwogerere Charles50% (2)

- Bonsai Carmona MicrophyllaDocumento6 páginasBonsai Carmona MicrophyllaslavkoAinda não há avaliações

- Miniature Bonsai: The Complete Guide to Super-Mini BonsaiNo EverandMiniature Bonsai: The Complete Guide to Super-Mini BonsaiNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (3)

- Bonsai Trees: The Ultimate "How To" Guide for BeginnersNo EverandBonsai Trees: The Ultimate "How To" Guide for BeginnersNota: 1.5 de 5 estrelas1.5/5 (2)

- Bonsai SecretsDocumento30 páginasBonsai SecretsKMCopelandAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction to Conifers: Growing Conifer Trees and Shrubs in Your GardenNo EverandIntroduction to Conifers: Growing Conifer Trees and Shrubs in Your GardenAinda não há avaliações

- Bonsai FicusDocumento1 páginaBonsai FicusAsif sheikhAinda não há avaliações

- Bonsai 101: Mimicking Nature with Bonsai Trees: Ultimate Guide to Creating Your Own BonsaiNo EverandBonsai 101: Mimicking Nature with Bonsai Trees: Ultimate Guide to Creating Your Own BonsaiNota: 1 de 5 estrelas1/5 (1)

- Reactor Kinetics of Urea FormationDocumento21 páginasReactor Kinetics of Urea Formationtitas5123100% (1)

- PDF PDFDocumento11 páginasPDF PDFshanika jayaweeraAinda não há avaliações

- Larch ArihatoDocumento43 páginasLarch Arihatofiddlersgreen100% (1)

- Elm Tree GuideDocumento6 páginasElm Tree GuidebojuranekAinda não há avaliações

- Bonsai 1Documento18 páginasBonsai 1newspiritAinda não há avaliações

- Bonsai Tree LessonDocumento2 páginasBonsai Tree Lessonapi-525048974Ainda não há avaliações

- Right MaterialsDocumento2 páginasRight MaterialsAlessioMasAinda não há avaliações

- Bonsai For Beginners FaqDocumento25 páginasBonsai For Beginners FaqTulong PinansiyalAinda não há avaliações

- Bonsai by Brent WaltsonDocumento5 páginasBonsai by Brent WaltsonartlinefoxAinda não há avaliações

- Articles BougainvilleaDevlopmentDocumento2 páginasArticles BougainvilleaDevlopmentJuan Manuel AguiarAinda não há avaliações

- Bonsai CabeDocumento72 páginasBonsai Cabelalu ahmad faisalAinda não há avaliações

- Avoid Impulse BuysDocumento7 páginasAvoid Impulse BuysRohailAinda não há avaliações

- CONTAINER, The Chinese Word For Bonsai Is PUN-JAI - The 1. How To Make A BonsaiDocumento4 páginasCONTAINER, The Chinese Word For Bonsai Is PUN-JAI - The 1. How To Make A BonsaiAshok ChittaragiAinda não há avaliações

- Indoor GardeningDocumento19 páginasIndoor GardeningcoreyojAinda não há avaliações

- Monterey Cypress - Macrocarpa Bonsai Care GuideDocumento10 páginasMonterey Cypress - Macrocarpa Bonsai Care GuideSergio LlorenteAinda não há avaliações

- Bonsai Culture: Growing LocationDocumento2 páginasBonsai Culture: Growing LocationNicolás Solano CondeAinda não há avaliações

- The Wise Old Gnome Speaks: How to Really, Really, Really Care About Your GardenNo EverandThe Wise Old Gnome Speaks: How to Really, Really, Really Care About Your GardenAinda não há avaliações

- WULC - 14 - 1100-C V Venugopal OMIFCO Failure Analysis of HP Ammonia Pumps Suction Line Weld JointDocumento42 páginasWULC - 14 - 1100-C V Venugopal OMIFCO Failure Analysis of HP Ammonia Pumps Suction Line Weld JointMohdHuzairiRusliAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 9 PDFDocumento16 páginasUnit 9 PDFswingbike100% (1)

- Thesis RefrencesDocumento15 páginasThesis RefrencesSupriya SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Organic Fertilizers From Farm Waste Adopted by Farmers in The PhilippinesDocumento16 páginasOrganic Fertilizers From Farm Waste Adopted by Farmers in The PhilippinesLando LandoAinda não há avaliações

- 2009 Minerals Yearbook: Zeolites (Advance Release)Documento4 páginas2009 Minerals Yearbook: Zeolites (Advance Release)mghaffarzadehAinda não há avaliações

- 2020 Final Exam Intro To OADocumento1 página2020 Final Exam Intro To OAjonardAinda não há avaliações

- Final Farm Listing Brochure 1Documento2 páginasFinal Farm Listing Brochure 1api-236349088Ainda não há avaliações

- Biofertilizers and Their Eco-Friendly Use in AgricultureDocumento12 páginasBiofertilizers and Their Eco-Friendly Use in AgricultureRishi SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Fertilizer Subsidieswhich Way Forward 2-21-2017Documento49 páginasFertilizer Subsidieswhich Way Forward 2-21-2017Shounak DuttaAinda não há avaliações

- Maize Production Ministy NARODocumento10 páginasMaize Production Ministy NAROSenkatuuka LukeAinda não há avaliações

- Improving The Efficiency of The Vetiver System in The Highway Slope Stabilization For Sustainability andDocumento33 páginasImproving The Efficiency of The Vetiver System in The Highway Slope Stabilization For Sustainability andapi-19745097Ainda não há avaliações

- Rice Innovations2015 PDFDocumento79 páginasRice Innovations2015 PDFSrinivas KolaAinda não há avaliações

- AE 101 M10 - Farm Power and MachineryDocumento35 páginasAE 101 M10 - Farm Power and Machinerygregorio roaAinda não há avaliações

- Facts About Phosphorus and LawnsDocumento5 páginasFacts About Phosphorus and LawnsboomissyAinda não há avaliações

- Iffco PresentationDocumento16 páginasIffco Presentationalok sahuAinda não há avaliações

- Mukesh Chahar AgronomistDocumento3 páginasMukesh Chahar AgronomistnarendraAinda não há avaliações

- Climate Start AgricultureDocumento12 páginasClimate Start Agriculturetango0385Ainda não há avaliações

- Induced Breeding 2Documento3 páginasInduced Breeding 2Narasimha MurthyAinda não há avaliações

- Banana IPM CultivationDocumento7 páginasBanana IPM CultivationFarmsons AgriAinda não há avaliações

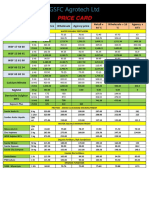

- Price CardDocumento2 páginasPrice Cardvim patelAinda não há avaliações

- A Sickle Is A HandDocumento11 páginasA Sickle Is A HandClark InovejasAinda não há avaliações

- Green MannureDocumento48 páginasGreen MannureHollywood movie worldAinda não há avaliações

- Teocuicatl Divine ExcrementDocumento9 páginasTeocuicatl Divine ExcrementVioleta Coyolxauhqui HagenAinda não há avaliações