Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Public Pater

Enviado por

Sabrina AssisDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Public Pater

Enviado por

Sabrina AssisDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

The Emerald Research Register for this journal is available at http://www.emeraldinsight.

com/researchregister

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at http://www.emeraldinsight.com/0951-3574.htm

AAAJ 16,3

Public private partnerships: an introduction

Royal Holloway, University of London, Egham, UK, and King's College, London, University of London, London, UK

Keywords Public sector accounting, Public finance, Private Finance, Private sector organizations, Financial management, Partnership Abstract Public private partnerships (PPPs) are a recent extension of what has now become well known as the ``new public management'' agenda for changes in the way public services are provided. PPPs involve organisations whose affiliations lie in respectively the public and private sectors working together in partnership to provide public services. This special issue of the Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal explores this new development, which, in its most advanced form, is contained in the UK's Private Finance Initiative (PFI) but is now spreading across the world in multiple forms. This introduction provides an overview of this development as well as an outline of the seven papers that make up this special issue. These seven papers are divided into two parts the first four looking at different aspects of PFI and the latter three providing three country-based (from the USA, New Zealand and Australia) studies of PFI/ PPP. Many questions about the nature, regulation, pre-decision analysis and post-project evaluation are addressed in these papers but many research questions remain unanswered, as this Introduction makes plain.

Jane Broadbent

332

Richard Laughlin

Introduction As the Institute of Public Policy Research (IPPR) made clear in its, admittedly UK-biased, but still internationally relevant, report, Building Better Partnerships (IPPR, 2001, p. 15):

. . . people . . . demand better public services . . . However, . . . to win this fight the case for public services needs to be made in terms of values and outcomes rather than particular forms of service delivery.

Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal Vol. 16 No. 3, 2003 pp. 332-341 # MCB UP Limited 0951-3574 DOI 10.1108/09513570310482282

Public private partnerships (PPPs) are one form of this policy of liberalisation in the way public services are produced and delivered to the public. PPPs open up the possibilities for the provision of public services, not only to come exclusively from organisations owned and controlled by the public sector, but also from both public and private sectors in partnership. To accept that public services could be supplied by PPPs inevitably requires liberalisation in thought, since, as IPPR are at pains to point out, the ``public good, private bad'' (IPPR, 2001, p. 23) argument in the provision of public services is still very close to the surface. Like the IPPR, we too, are of the view that PPPs cannot be ruled out on the basis of prejudice but need to be analysed with an open mind

The authors wish to express their thanks for the comments on previous drafts of this Introduction by the Editors of the Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Lee Parker and James Guthrie.

as to whether they do provide a ``better'', however defined, way of providing public services. It is, therefore, these partnerships, the way that they are embarked upon and their ramifications for the provision of public services and the accounting, auditing and accountability implications of these relationships, that are the central concerns of this special issue of the Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal (AAAJ). The development of PPPs across the world has been less than uniform or unitary in nature (as is the case with most of the new public management reforms (Olson et al., 1998)). The three country-based papers in this special issue of AAAJ, by Richard Baker (Baker, 2003) (on the USA), by Sue Newberry and June Pallot (Newberry and Pallot, 2003) (on New Zealand) and by Linda English and James Guthrie (English and Guthrie, 2003) (on Australia) demonstrate this international diversity. The remaining four papers by David Heald (Heald, 2003), Brian Rutherford (Rutherford, 2003), Pam Edwards and Jean Shaoul (Edwards and Shaoul, 2003), and Jane Broadbent, Jas Gill and Richard Laughlin (Broadbent et al., 2003) take a UK focus, concentrating primarily on the different technical issues surrounding the most advanced and dominant form of PPPs Private Finance Initiatives (PFIs). Broadbent and Laughlin (1999, pp. 106-12) posed a research agenda a few years ago specifically in relation to PFIs. If we read this agenda as not totally applying just to either PFIs or the UK then it is surprising how many of the themes still stand and have been addressed in the papers in this special issue of AAAJ. In different ways all the papers are addressing the research questions: ``what is the nature of PFI (PPP) and who is regulating its application?'' and ``how are definitions of PFI (PPP) in terms of value for money and risk transfer derived and operationalised?'' In addition Edwards and Shaoul (2003) and Broadbent et al. (2003) start to address the vexed question of ``what is the merit and worth of PFI (PPP)?'' Before looking at these papers in a little more depth it is important to provide a few building blocks, starting with trying to be clear about what constitutes ``public services''. This is because a private sector supplier arguably becomes a PPP, rather than remaining a private supplier, when it supplies ``public services''. This, in turn, requires definition of the borderline that distinguishes public from private services. One neat, but unfortunately incomplete, way to do this would be on the basis of whether charges need to be made to secure the respective services. However, whilst some public services are free at the point of delivery, many, even in those countries with a longstanding and extensive welfare state, are increasingly making charges for the services that are supplied to the public. A key element in differentiating the two sectors, we will argue, is the existence of a regime of state price regulation. Broadbent and Guthrie (1992, p. 8) struggled with this same dilemma of demarcation when they were trying to define what constituted the ``public sector''. Their solution, which makes some important distinctions between ownership and control, provides a useful pragmatic vehicle for resolving this borderline problem. Their view is that if certain organisations, even though

Introduction

333

AAAJ 16,3

334

formally owned by private shareholders, are still the focus of ``ownership'' claims (over the outputs provided since they are in the ``public interest'') and control intentions (over input provision) by central and local governments, then these are still de facto part of the public sector and are delivering public services. Thus the provision of say utilities (gas, electricity, water) are public services, whether the organisations providing these services are now owned by private shareholders (as in the UK), having originally been part of the public sector, or are, and always have been, owned by private shareholders (as in the USA). A PPP is an approach to delivering public services that involves the private sector, but one that provides for a more direct control relationship between the public and private sector than would be achieved by a simple (legally-protected) market-based and arms-length purchase. The papers in this special issue show that this can take a number of forms and illustrates this variety in different jurisdictions. Beyond privately owned public service suppliers (such as utilities) are the PPPs that have been developed in a more proactive or collaborative mode and which, from the start, have been recognised and labelled as such. It is the development of these latter PPPs in the traditional public sectors throughout the world that have been the subject of considerable research interest. These PPPs are the most recent development of ``new public management'' (NPM) (Hood, 1991; 1995) the overall nature of which has become well-established in many countries. In the UK, New Zealand and Australia particularly, as well as in other nations around the world, large parts of the public sector were subject to aggressive privatisation in the 1970s and 1980s. Because of its existing tradition, the USA never had to engage in such an extensive privatisation programme a point Baker (2003) makes clear. Instead, the rest of the world simply caught up with the US model of provision of some key public services by turning to privatisation. Baker's consideration of the utilities companies in the USA argues these newly, or never privatised, organisations were the original PPPs. This argument rests on our earlier proposition that the nature of regulation and control is a crucial element in decisions about what might be seen as a PPP. In moving to provide public services, using private sector companies, it was essential that the various governments around the world could exercise some ownership rights and control over the nature, and, particularly, pricing, of the public services offered by these privatised companies. Hence, regulative regimes such as that described by Baker were developed. The early 1990s provides a turning point in the UK, Australia and New Zealand. At that point, in all three of these countries, the regulated privatisation of major parts of the public sector, that provided the basis for the nascent PPPs, ceased. In the UK and Australia this was probably because there was little else that could legitimately be sold off. In New Zealand, on the other hand, as Newberry and Pallot (2003) demonstrate, this cessation was probably due to the political and economic problems engendered by the privatisation programme that had been pursued. The move away from large scale

privatisations in the UK led to an explicit attempt to engage with the private sector in a different way. This became known as the Private Finance Initiative (PFI). PFI was launched in 1992. This was followed by something similar in Australia under the generic titles of ``privately financed projects'' as English and Guthrie (2003) indicate. The generic term PPP has, however, increasingly been adopted in the UK even though PFI still predominates. New Zealand, on the other hand, so often the leader in NPM reforms, has yet to see a serious launch of PPPs due, it seems, to the political and economic repercussions of their privatisation programme and the association of PPPs with these disasters (Newberry and Pallot, 2003). PFI as the exemplar PPP? Given the significance of PFI in the development of PPPs worldwide it is important to provide some brief background into the history and nature of this, primarily, UK-based initiative. The UK's PFI was launched in Autumn 1992 by the Conservative Chancellor of the Exchequer, Norman Lamont. The longstanding ideological stance of the Conservative government that the private sector would supply better public services than if they were supplied solely through the public sector was a driver. It was in this context that PFI was launched. The use of PFI was limited before the general election of May 1997, when the Conservative government was finally defeated after 18 years in power. PFI, up to this time, was primarily used to finance transport projects notably the Channel Tunnel joining the UK to mainland Europe. The stuttering progress of PFI could have stopped altogether had the incoming Labour government not had an about-turn on their original negative stance towards PFI. By bringing it in as a special case under the umbrella of their chosen ``third way'' approach and arguing that PFIs were only one form of PPPs the Labour government became ardent believers in its worth. They were determined to make PFI/PPP a success and also to expand its area of influence into all departments of central and local government. Now the driving force for PFI is HM Treasury in the heart of the government. As a result PFI is actively pursued with some 450 contracts worth over 50 billion underway or completed. The Labour government has taken PFI to new levels, both in terms of how and when to make PFI decisions as well as into areas where the Conservative government would have liked to go but were unsuccessful notably in hospitals, schools and universities. PFI, in its purest form, is a design build finance and operate (DBFO) system. It usually involves the provision, by a private sector consortium, of propertybased services for a period of a minimum 30, and, more usually, 60 years, to a public sector ``purchaser''. In exchange for these services over this 30/60 year time horizon the public sector pays a monthly, in effect, lease cost to the private sector supplier. This monthly cost is revised periodically as the contract progresses. The central characteristics of a DBFO system is that the private sector supplier is deemed to be the provider of a ``service package'' involving the design of any building and the accompanying operational management of

Introduction

335

AAAJ 16,3

336

the building and its aligned services (following an output specification from the public sector purchaser). The private sector partner also has to manage the overall financing of the entire project, particularly at the outset where high capital costs have to be incurred. PFI is clearly a PPP and is in marked contrast to how this ``service package'' would be supplied, if this supply came only from those employed by the public sector. To be fair the latter provision has rarely occurred. Even under normal public sector procurement the private sector may well be involved through definable sub-contracts where particular expertise may not be in the employment of the public sector. The real difference in the two forms of procurement lies in overall control of the service provision. There are various aspects to this. First, with PFI, the building is technically not owned by the public sector although who has the ``asset'' of the building is a major disagreement in PFI (see below for more about this). Second, the design of this building, along with the accompanying services, is the responsibility of the private sector. The public sector should not be actively involved in this specification all it specifies is the outputs it requires in terms of services. Third, the public sector is locked into a long-term relationship, specified as best as possible through a legal contract, with a private sector supplier who might have different values and interests. A genuine concern to many is that this private sector supplier, with its profit emphasis and necessity to give priority to its shareholders, may or may not share the same public service values that might be the case if provision was exclusively made by those in the employment of the public sector. In fact, some have gone further to suggest that the profit motive, which inevitably must drive the private sector supplier, is fundamentally different to, and likely to clash with, the values and ethos of the public sector. Accounting and auditing related issues in PFI Thus, the introduction of PFIs gives rise to an extensive set of technical research questions, many of which are accounting and auditing related. These are the central concern of the first four of the papers in this special issue of AAAJ. The paper by David Heald captures the key factor that has been put forward for why PFI should be pursued in the UK that it delivers value for money (VFM) for the public sector from the individual (micro) projects. Heald (2003) highlights the difficulties in operationalising this criteria and the way it has been interpreted in the UK situation. This involves a comparison of the net discounted costs (over the up to 60 years) of the PFI alternative with something called the public sector comparator (PSC) which is actually a ``surreal'' rather than a ``real'' viable alternative as Heald makes plain. Downside risks, assumed to be borne by the private sector, if the PFI alternative is pursued, are an important part of this calculation being added to the net discounted cost of the PSC so making, in most cases, the PSC more expensive than the PFI alternative. Who bears some of these downside risks is also key to the UK's

Accounting Standards Board's (ASB) fixation to decide on whose balance sheet (private or public sectors) the asset to the property part of the services should be situated. Which risks are and are not costed and taken into account in this financial accounting decision and in the VFM judgement is one of the key contributions of Heald's paper. The complex, and significant, financial accounting concerns surrounding PFI are developed further by Brian Rutherford. Rutherford (2003) probes into the reasons why the ASB are so sensitive about being clear as to who has the asset to the property part of any PFI deal. Using symbolic interactionism, Rutherford probes the meaning structure that lies behind the ASB's insistence that this be resolved following the ASB's rulings, despite the heated opposition to this strategy, as has been documented in a number of studies (cf. Hodges and Mellett, 2002; Broadbent and Laughlin, 2002). Rutherford traces this drive to a strong and consistent aversion to ``off balance sheet'' financing which, in turn, is driven by an almost fanatical need to be able to categorise financial transactions, as accounting ``assets'' and ``liabilities''. The paper by Pam Edwards and Jean Shaoul returns to the VFM theme but this time in relation to what they refer to as the ex post facto analysis once the decision to pursue the PFI option has been made. Edwards and Shaoul (2003) analyse two information technology PFI projects that have been very public failures as well as being subject to post-project investigations by the National Audit Office (NAO). By looking at these public documents they conclude that the risk transfer that was so important at the pre-decision stage to give the PFI alternative a positive advantage over the PSC did not occur. These downside risks were actually realised, with some considerable costs involved, yet, instead of being absorbed by the private sector, as anticipated, they had to be borne by the public sector, resulting in colossal losses and the consequent failure of the projects. They conclude with challenges to the NAO to be more active in redefining what criteria should drive the original PFI decision as well as for increased and more directed post-project auditing ex post facto. Jane Broadbent, Jas Gill and Richard Laughlin, in their paper, develop further this concern with post-project evaluation and the role of the NAO. Broadbent et al. (2003) propose a system that will allow a post-project evaluation judgement on VFM to occur, with a specific emphasis on the sensitive PFI projects in the National Health Service (NHS). They share the view of Edwards and Shaoul (2003) that the operation of this system should be the responsibility of primarily the NAO but also argue for the involvement of the Audit Commission (who share some responsibilities for the NHS). Both parties are already involved in auditing PFI projects, but Broadbent et al. (2003), supporting the view of Edwards and Shaoul (2003), argue that the nature of this current activity needs to be extended and developed. Broadbent et al. (2003) maintain that this development should reflect the VFM analytical system they are advancing. The system that they propose is drawn from an amalgamation of certain factors involved in the pre-decision VFM analyses,

Introduction

337

AAAJ 16,3

338

post-project evaluation intentions of NHS PFI projects that are underway and some recent developments in evaluation theory. Whilst these four papers are directed to PFI in the UK their relevance goes beyond some narrow country-specific or technical focus. They raise important questions concerning how it is possible to decide whether to proceed with a PPP, how to account for it once decided and how to evaluate the merit or worth of the decision. Whilst there may be differences of emphasis in other countries and other interpretations of PPPs these generic questions will always be relevant. In answering these questions accounting, auditing and accountability processes are centre stage. PFI/PPP across the globe The three country studies that end this special issue of AAAJ similarly transcend simple descriptions of what is happening in the USA, New Zealand and Australia. They provide unique and important insights into the working of PPPs in their respective countries but also highlight some further important general issues concerning PPPs. The paper by Richard Baker explores regulation failure in the USA, in relation to one of the most public of all scandals: Enron. Baker (2003) sees Enron as a PPP, being a regulated private sector supplier of gas and electric public service utilities. What Baker (2003) demonstrates is the dangers that can occur if the public regulator fails to exercise proper control over the supply of these public services, and PPPs more generally. When this is combined with the skilful reading and operation of the accounting rules by a supposedly respectable firm of accountants, who are meant to be part of the regulatory apparatus, disasters such as Enron occur. Enron with its ``off balance sheet'' financing and ``special purpose vehicles'' provides yet more reinforcement and justification for the meaning structure that guides the ASB and, in so doing, lends support to the thesis Rutherford (2003) is putting forward in this special issue. Whether this will be enough, as many in the UK claim, to prevent a similar Enron scandal occurring in the UK is, however, less clear. The paper by Sue Newberry and June Pallot traces the experiences of New Zealand with regard to PPPs. Their specific focus is the way it is possible to design accounting-related legislation to advance the cause of PPPs and allow this to wait on the statute books until the political climate is right to make use of such ``privileging''. Surprisingly, given New Zealand's centrality in NPM developments, there has been a remarkable lack of activity with regard to the development of PPPs. Newberry and Pallot (2003) trace this, as already indicated above, to the problems in the extensive privatisations that occurred in the 1980s. Yet what they show is that, in the design of the Financial Responsibility Act of 1994, there is clear evidence of a continuation of the privileging of private sector involvement in the provision of public services. As they argue, this is achieved by accounting means in relation to classifying future PFI-equivalent payments as ``commitments'' rather than ``liabilities'', with the former not counting on key national economic indicators and targets.

This act remains on the statute book, they argue, awaiting the politically correct time to make the move to encourage private sector involvement, which they see now as starting to occur. Finally, the paper by Linda English and James Guthrie explores the developments of PPPs (named privately financed projects (PFP) in Australia in the context of the question ``what is the nature of PFP and who is regulating its application?'' The debate as to whether the nature of PPPs has a primarily micro emphasis to improve the provision of public services (expressed in VFM terms) or is a way to solve a macro fiscal problem (expressed partly through ensuring PPPs are not on public sector balance sheets) has haunted the development of PFI in the UK. It has been resolved, to an extent, in the UK by making plain that it is the micro VFM argument that predominates, whilst, at the same time, the UK government would like, again supposedly for VFM reasons (as Heald (2003) makes plain), that any PFI/PPP project remains off the public sector balance sheet. In the UK-situation, therefore, the macro argument ``lurks'' in the background and is not seemingly as dominant. English and Guthrie (2003) argue that the evidence in favour of a macro or micro emphasis is even less in Australia which has in its states a more complex government structure than the UK. They draw from a range of ``steering mechanisms'' in the Australian context to make this judgement. As such, Australia falls somewhere in between New Zealand (more macro) and the UK (more micro) situations. Australia and New Zealand are probably closer than they are to the UK in relation to their more macro justification for the developments for PPP, although in the case of New Zealand the operational outworking of actual PPPs has hardly started, whereas, it is more widespread in Australia. Some concluding thoughts Whether it be a micro or macro nature of PFIs, PPPs or PFPs, what is accounted for in operationalising this nature is central. If there is one overall conclusion that comes from these papers it is a reinforcing of the theme which guides the whole ethos of the AAAJ that accounting, auditing and accountability systems are context-dependent and context-defined. Our task as researchers, as demonstrated in these papers, is to probe and expose these contexts and their connection to our technical accounting-related systems and raise questions and make suggestions about their redesign. But any redesign will also inevitably be context-dependent since that is the fundamental nature of accounting. The papers in this special issue demonstrate, in different ways, this fundamental contextual nature and role of accounting. Finally, with this more general point in mind, we need to end with some thoughts on what the seven papers have achieved in relation to research on PFIs and PPPs and what a future research agenda might include. As indicated in the introduction, Broadbent and Laughlin (1999) posed a research agenda for the UK's PFI in five questions. This agenda provides a useful pragmatic framework for exploring the contribution of the papers in this special issue of AAAJ as well as providing a starting point for clarifying a research agenda for

Introduction

339

AAAJ 16,3

340

the future. In different ways, as we suggested in the Introduction, the papers are addressing and answering the questions ``what is the nature of PFI (PPP) and who is regulating its application?'' and ``how are definitions of PFI (PPP) in terms of value for money and risk transfer derived and operationalised?'' In addition the papers by Edwards and Shaoul (2003) and Broadbent et al. (2003) start to look at the research question ``what is the merit and worth of PFI (PPP)?''. This important evaluation research question cannot be comprehensively answered in the immediate future and neither can the remaining questions as to ``how are PFI (PPP) decisions made in different areas of the public sector and what are the effects of these decisions?'' and ``is PFI (PPP) a form of privatisation?'' These questions, like the one on the ``merit and worth'' of PPPs, require detailed and, we would argue, theoretically-informed, empirical studies in specific areas over a period of time before meaningful insights will be forthcoming. This is the challenge for the future and one which will probably need to be undertaken in ``partnership'' with the National Audit Offices around the world, as Edwards and Shaoul (2003) and Broadbent et al. (2003) suggest. The other research question, which was not covered in Broadbent and Laughlin (1999) but the papers in the special issue highlight, is the importance of exploring the development of PPPs internationally. The move to PPPs is now a worldwide movement where there are marked differences in terms of levels of development and overall emphasis, all of which are in need of analysis and comparison. Some of the papers in this special issue make an excellent start in this regard. More research clearly needs to be done, since PPPs are likely to be the major vehicle for developments in the provision of public services for many years to come. Understanding how different countries adopt and adapt PPPs to their needs will be important to understand. More generally the papers in this special issue have hopefully highlighted the importance of PPPs in the provision of public services the world over as well as placed the issues surrounding this NPM development firmly on the research agenda for the future.

References Baker, C.R. (2003), ``Investigating Enron as a public private partnership'', Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 16 No. 3, pp. 446-66. Broadbent, J. and Guthrie, J. (1992), ``Changes in the public sector: a review of recent `alternative' accounting research'', Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 5 No. 2, pp. 3-31. Broadbent, J. and Laughlin, R. (1999), ``The Private Finance Initiative: clarification of a future research agenda'', Financial Accountability and Management, Vol. 15 No. 2, pp. 95-114. Broadbent, J. and Laughlin, R. (2002), ``Accounting choices: technical and political trade-offs and the UK's Private Finance Initiative'', Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 15 No. 5, pp. 622-54. Broadbent, J., Gill, J. and Laughlin, R. (2003), ``Evaluating the Private Finance Initiative in the National Health Service in the UK'', Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 16 No. 3, pp. 422-45.

Edwards, P. and Shaoul, J. (2003), ``Partnerships: for better, for worse?'', Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 16 No. 3, pp. 397-21. English, L. and Guthrie, J. (2003), ``Driving privately financed projects in Australia: what makes them tick?', Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 16 No. 3, pp. 493-511. Heald, D. (2003), ``Value for money tests and accounting treatment in PFI schemes'', Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 16 No. 3, pp. 342-71. Hodges, R. and Mellett, H. (2002), ``Investigating standard setting: accounting for the United Kingdom's Private Finance Initiative'', Accounting Forum, Vol. 26 No. 2, pp. 126-51. Hood, C. (1991), ``A public management for all seasons'', Public Administration, Vol. 69, Spring, pp. 3-19. Hood, C. (1995), ``The `new public management' in the 1980s: variations on a theme'', Accounting, Organizations and Society, Vol. 20 No. 2/3, pp. 93-119. IPPR (2001), Building Better Partnerships: The Final Report of the Commission on Public Private Partnerships, Institute of Public Policy Research, London. Newberry, S. and Pallot, J. (2003), ``Fiscal (ir)responsibility: privileging PPPs in New Zealand'', Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 16 No. 3, pp. 467-92. Olson, O., Guthrie, J. and Humphrey, C. (Eds) (1998), Global Warning! Debating International Developments in New Public Financial Management, Cappelen Akademisk Forlag, Oslo. Rutherford, B. (2003), ``The social construction of financial statement elements under Private Finance Initiative schemes'', Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 16 No. 3, pp. 372-96.

Introduction

341

Você também pode gostar

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Prescriptive AnalyticsDocumento7 páginasPrescriptive AnalyticsAlfredo Romero GAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Solaria Cuentas enDocumento71 páginasSolaria Cuentas enElizabeth Sánchez LeónAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Lecture 8 Metrics For Entrepreneurs and Startup Funding PDFDocumento28 páginasLecture 8 Metrics For Entrepreneurs and Startup Funding PDFBhagavan BangaloreAinda não há avaliações

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Alok Industries Final Report 2010-11.Documento117 páginasAlok Industries Final Report 2010-11.Ashish Navagamiya0% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Arts Club Membership ApplicationDocumento5 páginasThe Arts Club Membership ApplicationkerstinsaidlerAinda não há avaliações

- 5-1 ACC 345 Business Valuation Report TemplateDocumento6 páginas5-1 ACC 345 Business Valuation Report Templatezainab0% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Financial Feasibility Study For Investment Projects Case 2: The NCF and The Pay-Back Period of Project PE1 of CUCODocumento3 páginasFinancial Feasibility Study For Investment Projects Case 2: The NCF and The Pay-Back Period of Project PE1 of CUCOMariam YasserAinda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Accounts Imp Qns ListDocumento192 páginasAccounts Imp Qns ListRamiz SiddiquiAinda não há avaliações

- What Are The Four Basic Areas of FinanceDocumento1 páginaWhat Are The Four Basic Areas of FinanceHaris Hafeez100% (5)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Ratio of Sasbadi Holdings Berhad For Group 2016 1. Liquidity RatioDocumento7 páginasRatio of Sasbadi Holdings Berhad For Group 2016 1. Liquidity RatioizzhnsrAinda não há avaliações

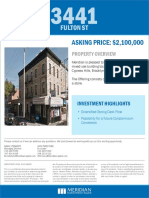

- 3441 Fulton ST TeaserDocumento1 página3441 Fulton ST TeaserZach FirestoneAinda não há avaliações

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- General AbilityDocumento14 páginasGeneral AbilityScribd ReaderAinda não há avaliações

- The Organizational Plan: Hisrich Peters ShepherdDocumento23 páginasThe Organizational Plan: Hisrich Peters ShepherdHamza HafeezAinda não há avaliações

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Indian Automobile Industry AnalysisDocumento41 páginasIndian Automobile Industry Analysismr.avdheshsharma85% (26)

- Exploring Corporate Strategy: Gerry Johnson, Kevan Scholes, Richard WhittingtonDocumento26 páginasExploring Corporate Strategy: Gerry Johnson, Kevan Scholes, Richard Whittingtonnazish143Ainda não há avaliações

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- 10 Illustration of Ledger 24.10.08Documento7 páginas10 Illustration of Ledger 24.10.08denish gandhi100% (1)

- CSR of ONGCDocumento12 páginasCSR of ONGCpriyanshiAinda não há avaliações

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Assessment of Operational BADocumento26 páginasAssessment of Operational BAFaruk HossainAinda não há avaliações

- Royal Cargo. ContradictDocumento4 páginasRoyal Cargo. ContradictRiffy OisinoidAinda não há avaliações

- Glossary Entrepreneurship Development: V+TeamDocumento8 páginasGlossary Entrepreneurship Development: V+TeamCorey PageAinda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Master Thesis 2021: Aakash Mishra URN 2021-M-10081997Documento48 páginasMaster Thesis 2021: Aakash Mishra URN 2021-M-10081997Akash MishraAinda não há avaliações

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Women and Banks Are Female Customers Facing Discrimination?Documento29 páginasWomen and Banks Are Female Customers Facing Discrimination?Joaquín Vicente Ramos RodríguezAinda não há avaliações

- NOV23 Nomura Class 6Documento54 páginasNOV23 Nomura Class 6JAYA BHARATHA REDDYAinda não há avaliações

- Acctba3 E2-1, E2-2, E2-3Documento13 páginasAcctba3 E2-1, E2-2, E2-3DennyseOrlido100% (2)

- Budget and Budgetary ControlDocumento17 páginasBudget and Budgetary ControlAshis karmakarAinda não há avaliações

- Glaski - Appellant's Reply Brief-1Documento22 páginasGlaski - Appellant's Reply Brief-183jjmackAinda não há avaliações

- 1 1 Do Not Keep Blank Signed DIS WTH DP or 2 Broker 2 Write To DP If CAS Is Not ReqdDocumento2 páginas1 1 Do Not Keep Blank Signed DIS WTH DP or 2 Broker 2 Write To DP If CAS Is Not ReqdSachin KNAinda não há avaliações

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Post Merger People Integration PDFDocumento28 páginasPost Merger People Integration PDFcincinatti159634Ainda não há avaliações

- Audit of The Capital Acquisition and Repayment CycleDocumento20 páginasAudit of The Capital Acquisition and Repayment Cycleputri retno100% (1)

- Ch1 FundamentalsDocumento45 páginasCh1 FundamentalsFebri RahadiAinda não há avaliações