Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Visual Poetry in The Avant Writing Collection

Enviado por

RobinTreadwellTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Visual Poetry in The Avant Writing Collection

Enviado por

RobinTreadwellDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

V

T

H

E

O

H

I

O

S

T

A

T

E

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

L

I

B

R

A

R

I

E

S

Visual Poetry in the

Avant Writing Collection

P

O

E

T

R

Y

is

u

al

Visual Poetry in the

Avant Writing Collection

V

T

H

E

O

H

I

O

S

T

A

T

E

U

N

I

V

E

R

S

I

T

Y

L

I

B

R

A

R

I

E

S

P

O

E

T

R

Y

is

u

al

Edited, with an Introduction, by John M. Bennett

With Additional Introductions by

Bob Grumman

and

Dr. Marvin A. Sackner

The Rare Books & Manuscripts Library

The Ohio State University Libraries

2008

T H E O H I O S T A T E U N I V E R S I T Y L I B R A R I E S

A V A N T G A R D E P O E T R Y C O L L E C T I O N

Introduction

by John M. Bennett

visual poetry

Como de costumbre, para ser futurista solo haba

que ir lo ms lejos possible al pasado.

Augusto Monterroso

All poetry is visual poetry. This idea, along with its corollary that all poetry is also

aural, has become clearer and clearer to me as I have worked with the extremely

varied materials in The Ohio State University Libraries Avant Writing Collection. Visuality in poetry starts with

the simple fact that there are blank spaces at the ends of lines, which is perhaps the most consistent factor that

distinguishes poetry from prose. (A prose poem is poetry in the fact that the blank spaces are present by implication;

present in their absence, you might say.) That blank space then extends to an almost innite variety of forms and

procedures, from typographic variance to three-dimensional constructions, from shaped poems to classical

concrete poems, from recognizable words and phrases arranged in patterns to asemic scrawls and letter-forms and

to purely graphic elements arranged in a poem-like manner. With respect to orality, it is safe to say that there is

not a poem in existence that could not be performed aloud in some way. Even the most illegible asemic scrawl can

be used as a script for the voice, and often is by many of the poets in this collection and in the traditions from which

the work in it has sprung. It may well be that poetry began before writing as a mnemonic social context for stories,

news, and myths and thus as an oral form, but as soon as it began to be written, it became a visual form as well.

1

T H E O H I O S T A T E U N I V E R S I T Y L I B R A R I E S 2 A V A N T G A R D E P O E T R Y C O L L E C T I O N 3

Visual poetry calls to mind doubts about the stability of meaning in languagethat is, the strict relationship

between language and reality. Visual poetry, perhaps more than normal textual poetry, presenting or suggesting

meaning on several levels and through several processes of consciousness simultaneously, mirrors that doubt. Or

perhaps it is an attempt to do what language has always tried to do: capture reality and make it conscious. The

difference is that visual poetry perceives realityor the worldas multiple, ambiguous, shifting, polyvalent, and

paradoxical. The opposites join into one total perception. The fact that different parts of the mind and/or mental

processes address visual experience and linguistic experience (and within linguistic experience itself there are

very different and separate processes for each functionality of language: speaking, thinking, writing, translating,

etc.) means that visual poetry is especially useful for dealing with and presenting this multivalent/multiconscious

experience of the world. I suspect that has something to do with why it is so often a eld of endeavor that is

ignored in the genre-categorizing institutions of our society: those genres (visual art, literature, music, and so on)

are not only socially constructed, but present a much simpler and therefore more comforting vision of what the

world is. I suggest that that simple vision is limited and illusory, however. Clemente Padn, the great Uruguayan

visual and experimental poet, has discussed at some length how visual and experimental poetry stand in direct

opposition to the dominant socioeconomic paradigms of our day (see his essay in Signos corrosivos, Mexico:

Ediciones Literarias de Factor, 1987; translated by Harry Polkinhorn as Corrosive Signs, 1990).

Almost all the poets and writers in the Avant Writing Collection have worked in visual media and genres, and

this catalog is an attempt to showcase some of the highlights of that vein of creativity in the collection. I wish to

emphasize, however, that these works do not exist in a completely separate category, a compartment in which

the artist/writer works in isolation from his or her other work, but function on a continuum with all that other work.

Many of these works, for example, have also been treated as performance texts. As Michael Basinski has stated,

A function of visuality is performancea visual poem should be interpreted as a literary scorevisual poets

should consider their pieces to be literary scores rather than purely literary, visual images (in CORE: A Symposium

on Contemporary Visual Poetry, ed. By John Byrum & Crag Hill, Mentor, OH/Mill Valley, CA: Generator Press, c1993).

It is always difcult to select what pieces to exhibit in a catalog like this, when there are so many excellent

possibilities. I have tried to show the immense variety of styles and approaches that exist in the collection and

to pay special attention to those individuals works whose larger collections of papers and archives are at the

heart of what we have here. Visual poetry is a eld of endeavor that is expanding exponentially just now, helped

immeasurably by the ease of distributing it through the Internet: web sites, blogs, e-mail, social networking sites,

and so on. I hope this sampling will inspire more such work.

Dr. John M. Bennett

August 2007

3

Sweeping aside the sweeping generality above, however, it would be of some use to discuss at least some of what

it is that distinguishes the work in this anthology from standard textual poetry. Perhaps it simply has to do with the

fact that all the work here includes strongly visual dimensions that one cannot avoid including as an important

part of the experience of reading/seeing the work in question. Whereas in the case of textual poetry, the visual

dimension is to a large extent unconsciously perceived, or that it is at least possible to experience the work paying

little attention to its visual qualities.

There is also the question of the long and varied history of visual literature, which to a large extent forms its own

tradition or subculture, to which the work in this anthology so often refers. That history is distinct in numerous ways

from the history or subculture of more strictly textual poetry, and therefore is a distinguishing characteristic from it.

Another issue is the relationship of visual poetry to visual art, and the use of linguistic elements in what is generally

considered to be visual art. At what point does such art become visual poetry? I think it is more useful and enriching

to think of it as either or both, depending on the context of ones discussion or appreciation. Just as, at the other

end of the continuum, it is most useful to think of poetry and visual poetry as either or both.

Underlying these considerations is the fact that inherent in Western Civilization, and probably in the human mind

itself (as in large part a creation of that civilization) is the need to categorize phenomena. This is certainly true

for visual poetry, which is generally regarded as a phenomenon separate in itself. In fact, however, as suggested

above, it is an aspect of all written language, and has been since written language came into existence. Being

inherently visual, written language must be seen to be apprehended (or, as in the case of Braille or other

technologies, in some way physically experiencedin the case of a blind person being read to, the reader must

see the text) and its very nature is founded on signs and symbols referring to things in the physical or mental world,

be they sounds, objects, or actions. In the case of poetry in particular, the usual modern poem, with its blank spaces

either at the ends of lines or surrounding the words, requires a visual experience to be fully known.

2

T H E O H I O S T A T E U N I V E R S I T Y L I B R A R I E S 4 A V A N T G A R D E P O E T R Y C O L L E C T I O N 55

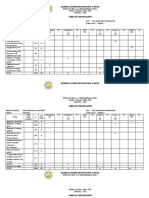

309 poems 11 countries 89 poets

Abstract markings subservient to texts and images are a common component of

visual poems that serve as ornament and are present in 107 out of a total of 309

poems (Kostritskii 151). Asemic writings, a specialized form of abstract markings,

are utilized in 26 poems (Leftwich 181, Dermisache 63). Asemic writing has no

semantic content. As Peter Gaze amplied, asemic texts, a term coined by

Jim Leftwich, have no writer-intended meaning. If you the viewer perceive

a meaning, youve created that meaning yourself. Text or marks formed by

handwriting is the second most common means (25% of the poems) to create

concrete (Beaulieu 12) or visual poems (Weiss 264).

Fragmented texts occur on 14% of the poems. Here, words are only partially

printed (Macleod 200, Ernst 73) or are separated by large spaces (aND 3).

pictures are poems in which letters alone (concrete poems) or combined with

images (visual poems) are present in 16% of the poems. Letter pictures are

rubber-stamped (Helmes 126), printed (Altemus 2, Morin 203), or hand

drawn (Quarles 220, Luis 191). Text over text poems constitute 9% of the 309

poems in the original selection for this book (Cobbing 44).

Made-up words appear in 6% of the poems (Basinski 10). Conventional (Cobbing

46, Nichol 214) or computer typings (Daniels 60) is one of the oldest forms of

contemporary concrete poetry (since the 1950s). Such typewriter poems amount

to 6% of the poems. There are 15 shaped poems in which words or letters outline

recognizable images (Daniels 59). They are the oldest form of concrete poems

in the literature and examples have been recovered from ancient Chinese,

Japanese, Persian, Malayan, Burmese, Tibetian, Indian, Urdu, Ethiopian,

Moroccan, Arabic, Turkish, Armenian, Hebrew, Greek, German, and Roman

sources. Poems in which the letters or words are smudged or distorted with

rubber-stamping (Helmes 115) or photocopying (Topel 258, Figueiredo 95)

processes constitute 4% of the poems.Cancelled texts are present in ve poems

(Huth 139). Mathematical poems that employ mathematical equations are used

in six poems (Grumman 110). Finally, Ficus strangulensis contributes the only

example of a transmorfation (Ficus 88) in this book, a term he coined (and

also a form used by other poets) of one word calligraphic poems that degenerate

to calligraphic markings and subsequently emerge as another word.

John M. Bennetts compilation of so many outstanding concrete and visual poems

attest to his curatorial skills, honed to perfection in a world he knows full well.

Letter

v i s u a l p o e t r y

Introduction

4

John M. Bennett, the editor/publisher/founder of the most important

and longest running contemporary experimental poetry magazine,

Lost and Found Times, 1975-2004, has put together an outstanding

collection of concrete and visual poems made from 1968 to 2006.

Eighty-nine poets from 11 countries were selected, with the majority

from the United States. The poems are diverse and follow no particular

theme. They reect Bennetts taste and experience, which is conditioned

by his reading and writing several thousand poems in his role with Lost and

Found Times. This book presents a wonderful selection of poetry on the same

level of Bel Canto arias.

Faced with 309 poems [these 309 poems, edited here down to 268, refer

to the original draft selection Dr. Sackner used to write his introduction

the percentages he gives in what follows are based on that original

selection of 309 images] to review for this introduction, I relied on a

classication technique for my own collection, Sackner Archive of

. This forced me to think about each poem and minimized

visual fatigue from merely looking without putting pen or keyboard strokes

to paper. Also, I was curious as to whether Bennetts selected poems for

publication were based upon personal preferences since his style is rooted

in calligraphic handwriting and markings as well as collaborations with

other poets. Only 9% of the 309 poems are collaborations and 25% involve

handwritten texts but these totally differ from Bennetts idiosyncratic style.

Thirty-nine percent of the poems are concrete (Kempton 149) and 61%

are visual (Dalachinsky 57) according to my denitions, although I

acknowledge that Bennett and his circle prefer to lump them together

as visual poems. I dene concrete poems as those in

and/or words are utilized to form a visual image whereas

visual poems constitute those in which images are integrated into the text

of the poem. I counted picture poems as visual poems although in my own

collection, they fall into a separate category.

in which an image and a related

caption are printed together. They are a single-page Livre dArtiste or an

illustrated book. The best contemporary examples are those composed

by Kenneth Patchen. Most picture poems in this book might be designated

quasi-picture poems since the captions are poems that do not strongly relate

to the accompanying images (Taylor 244) with rare exceptions (Ford 94).

by Dr. Marvin A. Sackner

Concrete and Visual Poetry

which only letters

Picture poems are

an evolution of Renaissance emblem poems

A V A N T G A R D E P O E T R Y C O L L E C T I O N 7

Probably everyone writing about this collections kind of

visio-textual art, or art that combines text and graphics, has a

different way of sorting the various forms it can take. I use what

I think is a simple continuum to do this. It starts an innitesimal

distance from pure poetry, or the wholly verbal, and ends an

innitesimal distance from the wholly graphic, or pure visual art.

Halfway in between are works that are more or less half textual

and half visualcollages and the like, for the most part.

First on my long list of works to treat is the comic, deadpanned

pin in High Arts sometimes pretentiousness provided by John

Furnival and Emmett Williams, Wallpaper for a Classical Passion-

Pit Atop Mount Parnassus (96), whose endlessly repeated text,

Basho bonks Sappho bonks Basho bonks Sappho needs no

elucidation. Few works in the collection are funnier (although

many are quite funny), and it is clearly about as close to the mainly

verbal end of the visio-textual continuum as visual poetry can be.

Perhaps even closer to it is Miekal Ands Automatic (3). In one

portion of it, a Knowing Wages Ways to Collage Lightor so

it plays out for me. It avoids being a conventional, wholly textual

poem due only to its (linear) spacing, and a few made-up words

like Mostra and Agrom. But the spacing of its words makes it

seem some sort of verbal abacus. This, for me, makes the poem

ever-so-slightly more than purely verbal.

A third poem that belongs close to the same end of my continuum

is K.S. Ernsts ROSE POEM (84), a variation on Steins rose

is a rose is a rose. Just three words in length, its about as

compact as a poem can be, but says three things (at least) in the

read-slowing game it plays through the use of unconventional

placement of letters: a rose arose, a rose, a rose and

because of the visual treatment of the vertical rose, a rose

sprung out into full being. Theres a simple rose on a stem in

the poem, too.

Another poem of Ernsts that consists of words only (if you

discount the fact that its page is a small wooden stage),

is the carpentered sculpture, The (66). Like the previous

poem, it goes back to a classical American modernist, this

one Wallace Stevens, grabbing his the the from The

Man on the Dump. Ernst makes the usually hardly noticed

denite article gloriously Important and accommodating,

sheltering (note its enclosures). A featureless bit of text is

given concreteness, identity, its place at the very hinge of

existence. . . .Words as the vital furniture of our minds, with

the a primary supporter of verbal expression, is a central

part of the poems metaphorical richness, as well. And note

how compressed the piece is, in spite of its being so many

repetitions of one word.

In Nude Stare (88), a specimen of what Crag Hill calls

transforms and its author Ficus strangulensis calls

transmorfations, a cursive nude descends through

quivers metaphorically suggestive of ekg readings to the

stare she is certain to causewhile we are reminded of

the famous Armory shows Nude Descending a Staircase

by Marcel Duchamp. Or, we can read the work as a stare

that enters into and becomes its object. This is a classical

visual poem, all words going through visual changes to

enact an image.

The by K.S. Ernst

T H E O H I O S T A T E U N I V E R S I T Y L I B R A R I E S 6

Who knows how he did it, but my pal, the multivariously-

nutto super-poet John M. Bennett, somehow wound his way

even unto the very bowels of the American cultural

establishment and there builded he a collection of

contemporary artworks amazingly counter to all that

the American literary establishment stands for.

Indeed, theres hardly a poem in it by anybody youd so much hear mentioned let alone seriously

discussed in any but a handful of American university English departments or whose work has ever gotten

onto the pages of such sophisticated venues as the New Yorker. To begin with, the works here do

not trade entirely on literary techniques in wide use 50 or more years ago, nor (usually) force some

socio-political agenda on us. Worse, for the word-centered professors of most English departments and

their counterparts in the publishing industry, they are pluraesthetic, which is to say each of them makes

signicant aesthetic use of more than one expressive modalitygenerally, the visual and verbal.

My hopes of providing a denitive overview of whats in the collection for this catalogue were killed when I

got copies of the pieces curator Bennett selected to reproduce in this catalogue. If only hed sent

them to me three centuries earlier! Even then, Im not sure I could have done a proper

overview of them. So many they are, and so various!

What follows will thus be a hodgepodge of my (very subjective) reactions to more or less randomly chosen

specimensmore accurately (in most cases), reproductions of specimens as they appear in this catalogue,

for Im writing this many states away from Ohio. I hope, however, that they are enough to give those who

come to this publication a reasonably thorough and interesting idea of whats here, and why it is of value.

Introduction

by Bob Grumman

T H E O H I O S T A T E U N I V E R S I T Y L I B R A R I E S 8 A V A N T G A R D E P O E T R Y C O L L E C T I O N 9

thirds letters, but it is xeroxially enlarged, with one letter tilted, and one larger

than the others and cut off, as well as over- or under-lapping the other letters. Thats enough to

make an engagent perceive the work as what I call illumagery, or visual art. The letters help us feel

at home, with something familiar, to ease us into an enjoyable, quite forceful non-representational

illumagea kind of variation on Franz Kline, the attachment of which to the verbal multiplies a freshness

into it. At the same time, it is (amusingly, among other things) a story about something that was on but

is now off. Something that is off that a huge n, you better believe, is going to knock aside, to produce a

powerful on. Or the reverse, a sinking on that offness is rising out of.

Then theres Julian Blaines point de poesie (35), which I nd somewhat taxonomically problematical.

It graphically denes poetry as a loop in boring straightness, with a literal point making it exclamatorily

valuable (and fun) with minimalistic deftness. No words, but enough of a word-fragment (when we have

the title) to make it impeccably a visual poem.

One nal piece within inches of the all-verbal end of my continuum that I want to bring up is Geof Huths

characteristically simple-seeming space (139). But what an eternity is back-and-forthed in this (implied)

excerpt from a description of the universe! But, wait: I want to mention Huths highly textual book, Dreams

of the Fishwife, as well, because of its demonstration of how much can be done to visually multiply a

text through simple small movements of letters. In his dis trusst of (140), one of his books pages, for

instance, he puts three es in an overlapping stack between a dr and an m to make drem not just

phonetically spell dream but become itself a dream under wayupward, out of the mundane, glaz-

ing the rest of its pages text dream-hued. The extra es also allowdrem to make a visual rhyme with

dseeem due to the latters overlapping es, although they are horizontally, not vertically, overlapping

(and rhymes, not overdone, are always magical). The font employed and medieval-seeming spellings add

a faerie long-ago quality to the dream the page holds, as doneedless to saythe Joyceanly-warped

spellings of its words.

Huths polylinguality, a forte of several visual poets such as Bennett and Luis, is evident in another

of his subtle concrete poems, AGA NEVER (also 139). This poem brings us into a new part of the

continuum, the one where we nd poetry with averbal graphic elements added to it. It nicely exemplies

the canceled poems Marvin Sackner mentions in his introductory essay. The cancellations are the (very

minor) graphic extras of the piece. But they are essential to making it a visual poem, for they disturb its

text into saying things it would not have said if left alone, as pure text.

Self-Portrait/Prole/

Poem by Marilyn R. Rosenberg

Portrait

by Lanny Quarles

One of American visual poetrys leading exponents, Richard

Kostelanetz, is represented in the collection with such

similarly only slightly visual works as no R CAVE (150),

which performs infraverbal tricks such as the division of

caveat into cave and at, and notables into no

and tables. The disregard for linear placement of the

texts words allows more than one message to form. The

message I like best here is, Notables: cave, at rest, rain.

This has a haiku simplicity and depth. Along with it, we

have: Warning: no tables.

Another leader in the eld as poet and publisher (of

Kaldron, which for many years was the only periodical

exclusively devoted to visio-textual art), Karl Kempton is

represented here by probably the

best collection of his work, Rune:

A Survey, among other things.

Charm (149), which is from the

aforementioned volume, is typical

of one of the many lines hes

taken as a poet: 3-D, vibratory,

employing just a single word,

symmetricaland happy.

A page from David Danielss

Years 1974 (61) is one more

completely verbal work whose

typography is altered to transform

it into something visual that can

stand by itself (but agrees with

its text too much not to be much

more than just visual). Its text reminds me for some reason

of John Bunyans Pilgrims Progressbecause, perhaps, of

its seriousness, and concern with the owering of the soul,

as shown with such grace by the pieces design, which is

(metaphorically) a sort of leaf (note the little stem at the

bottom) and much else, that expands globally but gently

outward at its center, with butterights in all directions in

the plane the rest of it inhabits. There is more than a hint of

ames, happy ames, in the piece, as well.

Annalisa Alloatti has a pair of visual poems (1) out of the

concrete poetry tradition here that depict a monument with

letters naming and describing it. ME and TU make up

its sides in the rigidly imposing rst version of the monu-

mentwith NON between them. A sterile monument in

which you and me are kept separate? Im not sure. In any

case, the monument in the companion version is coming

apart, whether shattering with joy or despair, Im not

sure, but equally exciting either way. And with

connotative small words or near-words infraverbally

anagramming out of monument such as muto.

Self-Portrait/Prole/Poem (224) by Marilyn R. Rosenberg

is a charmingly complete fusion of text and graphic whose

subject is self-reection. One wanders over it, its strands

of text pulling us into a much fuller physical examination of

the self that is drawn than a pure painting of it likely would,

while simultaneously carrying us along inside that self (as

it looks down and sees her feet in her shoes).

It is instructive to compare this to

Lanny Quarless Portrait (220),

which goes a good deal away

from just words to attain its

effect. About all one can say of

this piece is that it is clearly

a portrait, but a portrait that

portrays beyond the human

shape outlined in a wild

complexity of everywhere-going

connotativeness.

Ilse Garniers et 1 and et

2 (104), to get back to entirely

textual visual poetry, is about

rhythms (as I take rhythms

to mean) and silence. The

combination at once suggests being and nothingness,

difference and sameness (a rhythm having to have at least

two elements changing back and forth), motion and

motionlessness (because of the back-and-forth

movement a rhythm must have). Order and the void

(because the essence of order is predictable repetition).

At the same time, the two frames of the work express

union and separationalso the centrality of et, or

and as that from which all rhythm and silence issues.

And/or, et as ultimate unmoving fulcrum and unier of

Everything. In short, all kinds of metaphoricality are here.

Outside all this, we have two quite appealing pictures.

As the reader will have noticed, nearly all these poems

Ive been discussing are minimalist poems. Bob Cobbings

Off (45) certainly is. It consists of just three and

T H E O H I O S T A T E U N I V E R S I T Y L I B R A R I E S 8

Charm by Karl Kempton

T H E O H I O S T A T E U N I V E R S I T Y L I B R A R I E S 10 A V A N T G A R D E P O E T R Y C O L L E C T I O N 11

When I saw E (40), by Calleja, I immediately thought of our

planete for earth plus the drawing inside the e suggests

a continent. Ergo, the earth around a mind, the latter completely

imprisoning the formerbut only slightly larger than it. That is

just one possible interpretation. Another might make use of the

hook of the e, and consider the brain predatory. A simple work,

but a full visual poem, if one considers the e a near-word, with

the capability of traveling manywhere.

While many visual poets eschew the classic poems, Irving Weiss

has honored a bookload of them with visual manipulations on,

into, against, through, over, under, or beside them in his book,

Visual Voices, which is included in the collection. For instance,

in his Horror Poem (265), he reverses the message of Robert

Brownings dazzlingly positive poem, Pippas Song, with a

dynamically cruel X (to add a very small but consequential

graphic extra to the text of his work). How more devastatingly

(and hilariously) could one depict genuine horror?

A relatively large number of collaborations are in the collection

which is to be expected, considering what a prolic collaborator

curator Bennett is. One thats at this end of my continuum is

Thinking Zen (70) by Ernst and the late David Cole. Central to

it is a wondrous square aperture from which oats an oand

all an o can represent, as well asin my readingmaking

possible the 3-D (zen) thought it pivots, and the rains from which

issues . . . it. Probably more validly, its full text makes a haiku of

a person deepening through thought into something that is to

thought as thought is to reality (yes, Im peeling rather far beyond

whats there, but causing that is one of the principal values of this

kind of minimalism), while outside it is raining. Ordinary existence

persists. Even reduced to its most direct but least meaning, it

paints a Scrabble-ludic day extremely inside rain. And I keep

reading against in the set-up of rains and it because of the

ainst normal reading produces. A raining against zen thought,

or zen thought raining against . . . it. Murk of a grey day yet also

potential of rebirth. To sum up: a thought-centered thought-

producing serenely playful gadgetand something close to

conceptual art, as much visual poetry is.

Speaking of Bennett, Id like to turn to him nowbecause most

of his works in the collection are at this spot on my continuum.

But I want to treat a number of his works at once, somewhat

ignoring the continuum while I do so. It makes good sense to stick

with Bennett for a while for several reasons, aside from the fact

that his work is as certain to one day be considered major by the

estabniks (i.e., the professors and the like I mentioned before

who completely ignore visio-textual art) as any other poet

of his generation. One is that what he is as a curator has

a lot to do with what he is as a poet, so investigation of his

poetry should help illuminate the nature of all the pieces hes

gathered here. That would include a lot of his own poetry

here, too, since his oeuvre is one of some half dozen such

contemporary oeuvres held by the library, which makes it a

signicantly identifying element of said collection. A second

is that his work is interestingly multifarious. It may be that

it more that any other artists work exemplies the range of

visio-textual art.

Found My Sock (24) is fairly typical of one cartoony

strand of Bennetts work. He may be the inventor-for-

contemporary-poetry of the (expressively partnering)

framing found in this and many of his pieces. Within the

frame is the simple declaration, I found my sock. Due to its

Bennettian sub-demotic scrawl, this text by itself is a visual

poem, for that scrawl tells us loudly how much its speaker

struggled to nd his sockin the process (underconsciously)

nding his cock (repeated by the upward-pointing screws

above the text). And what a struggle it wasinside, it would

appear, a furnace. Surrounded by teeth, no, by fangs. A joke,

of course: some lout with a third of a brain, if that, has gotten

his quotidian day right (and exultantly regained his manhood).

Or, one of us, reduced by the agony of a missing sock to

such a lout (and I say that seriously remembering how trivial

things can genuinely upset one, make one think God or the

equivalent is not in his heaven), has become, through his

own efforts, whole again. Yow!

Found My Sock by John M. Bennett

The Farm (120), by Scott Helmes, has only one graphic

element, a rubber-stamped picture of a generic cow. Under it

are rubber-stamped captions for it, each absurd; it seems to

be an attempt to list the kinds of cows there are. I found it a

funny but silly dada exercise when I rst saw it, and several

times afterwards. The idea of a street cow versus a house cow

struck me as quite droll, though. The work succeeded as a

sort of satire on Sternly Serious Illustrated Instruction, but not

very much more. Until I attended rather than just allowed the

entrance of its title. The Farm. As happens to me boringly often,

I suddenly belatedly understood something obvious: we didnt

have a list of ve kinds of cowsor, better, we did have a list

of kinds of cows but it was an undermeaning; the foreburden

of the piece was a farm scene containing 10 nouns. A square

with a cow on it, a house with a cow next to it, the sky with a

cow in front of it. A swing with a cow behind it. A street with

a cow near it. (Oralso, I would put ita square house, blue

swing, and street plus cow, cow, cow, cow, cow.) A full scene

but with cows dominant: everything says cow. The technique

is close to that of Stein in rose is a rose is a rose, to return to

that: repetition where not expected, to almost drill an image of

cow to life. With this understanding, I saw how visual the piece

is. It presents a stack of cows, to begin witha manyness, that

is. It visually shows us the house in the square with the swing

and the street in front of it as numerically equal, and implicitly

equal in other ways, to the ve cows. The cows, too, are

rubber-stampedly prolic. Then theres the graphic image of

the cow, not just an illustration but an icon, high above a chant

in homage to it. Avenued up to it.

Portrait (204A), by Sheila E. Murphy, seems a simple design

in a box, a design whose elements resemble hieroglyphics,

with a label, portrait, announcing what the design is three

timesabove it, it would seem, and off to the right. With per-

sistence, one can nd English letters in the stack of hieroglyph-

icsin fact, SELF is spelled three times downward rather

than left to right. Ergo, the phrase, self portrait, occurs three

times. Simple seeming, with its background its only slightly

non-textual element once one deciphers the instances of

self, but so much is going on in it. The letters of self wave

like 12 ags on a pole, somewhat exhibitionistically. At the

same time, the word they spell withdraws into the difculty of

its decoding, and the modestly hand-drawn undressiness of its

letters. It also seems neurotically stretched. On the other

hand, it is paradingly repeating itself up the picture frame.

Contradictions. Each self is subtly different from the other

two; the person depicted is not consistent. Each, too, is

rectilinear, crudely logical, or trying for a kind of conformity.

In short, here is no mere word for self, but a patient for a

psychologist, while announcement of the record of it slips

sideways out of existence as the selves continue indenitely

alteringly ascending up and eventually out of the psychologists

viewing frame, which is capable of revealing only the minutest

portions of the full self on view.

Murphys Orchids (206) seems similarly simple: boxes with

words in some of them. Nice choice of colors. Beyond that,

though, note the greys framing my orchids (and consider the

choice of orchids as the owers in this poem) followed by the

downward plunge of nested boxes to a yellow onea plunge

that, for me, represents suffering. Inwardness is strongly

suggested. The orchids just about have to be code for me.

The rest of the text seems to me the outside worldits outside

the nested boxes, and in somewhat more cheerful colors,

and the attitude is fully outside the rest of the picture. Indeed,

it may be the cause of the rectangular prison the rest of the

poem is in.

What really grabbed me, however, was the way the plaintive,

yellow hopefulness of wont you touch me? drops from the

narrative (into a rectangle below the other rectangles holding

texts). The result is a wonderful psychological study, a genuine

poem and an appealing graphic design, all interacting. That is,

the text is not labeling but fullling the design, the design not

decorating the text but fullling the text.

Orchids by Sheila E. Murphy

T H E O H I O S T A T E U N I V E R S I T Y L I B R A R I E S 12 A V A N T G A R D E P O E T R Y C O L L E C T I O N 13

With Ilse Garniers Bee (102)

we come back to the portion of

my continuum for poems mainly

verbal but with graphics added. It

consists of texts inside something

laid out like a hopscotch game. What those texts say are similarly

playful. A capital B ascendantly occupies the highest of the

squares in the game. Meanwhile, a lower case b has own

from the alphabet in the lowest of the squares to the square

furthest to the right, uttering punfully into fullest life as a bee.

With, perhaps, a pause in the square to the left of that to create

a bloom (blume being German for bloom) having petals of

light (lume). Certainly the b as both upper and lower case

on the stem in the grey square support that reading. Im unclear

about the meaning of the word or words in the square furthest

to the left, but I know aime strongy suggests friendship and

love. Visually, of course, the me here rhymes with the three

instances of me in the square blume is in.

If one were to nd F.A. Nettelbecks book The Killer Elite left

behind in a library by someone, say, he would consider its

contents an odd collection of jottingspossibly a nutcases.

By simply presenting it as a work of art, though, Nettelbeck,

completely alters it into . . . Something Important. Something to

take seriously because it has been made public, not just as pages

in a notebook but as something we should pay special, sensitive

attention to. There are many points of interest in the pages shown

here (209). The spelling of civilization, for instance, makes the

notebook a glimpse into an outsider. A primitive, to an extent

as the writing is in a combination of upper- and lower-case print.

The correction of Denoted to denotingwhich means the

noise rst seeming to have denoted civilization is still denoting

it. This is all in a set-apart poem: ears soft tunnels/ (a noise

denoting civilazation)/ we stayed in the car. Safe from civilaza-

tion, I presume. Once we decide the texts are part of an artwork,

and attend sufciently to it, it begins to cohere into a unity con-

cerned with a decaying city. Note how the start, A caller,

is picked up late in the two pages by killer; kicking the

dead/ teacher is an image representative, in Wasteland-

jump-cut-style, of the decaying city.

The comic, comically emphasized YOU BET makes

consonances with eat, elite, street, and meat.

The last two rhyming words are part of another set-apart

poem, this one ending the piece.

That these two pages are from a notebook suggests copious

notes on the phenomenon discussed. Notebookness is what

makes the work a visual poembecause it is something

visual that adds signicant metaphorical imagery and feeling

to it. The writing helps make the work a visual poem, too, but

being jotting, or spontaneous responses to an environment.

The notebook is highly personal, toohandled.

Chapbooks form an important portion of the collection. A

representative one is by Michael Basinski whose proper title

consists of three occurrences of the astrological sign for

Aquarius with one instance of the astrological sign for Aries

under it. For reference books, its called [un nome]. Its

poems consist of words mildly jostled by graphics, or so

one might think on a rst encounter with it. The top line of

the sample poem (10) reproduced in this catalogue seems

an unconventional decoration, nothing more, though

somewhat appealing as sideways Us or backward cs

pointing, it would seem, to a rectangle, and further, to a circle

I take for the moon (because of its appearance, but also

because I am familiar with Basinski as a habitual poet of the

moon). The sideways Us are half rectangles, half circles,

so the line works as a tune of sorts, the half&halfs turning

to a thin perimetered rectanglethat in turn becomes its

arrestingly opposite, a circle. Meanwhile, abstractionsthe

half&halfs and the rectanglegain a kind of life as a moon

(high in the sky) above for ER fest rueor what infraver-

bally mainly says forest: to me. It also hints of forever,

for-ness, or state of being for someone, with fest explicit,

but rue, as well, slivering the experience, perhaps, like the

slight moon overhead. But rue is also the completion of the

word, true.

b ee

by IIse Garnier

In another crazy poem of Bennetts, Kok (30), the text is minimal, the graphic component entirely

fused with it (except for one word)and the penis back again, this time dominant. But it is far from

all that is in the poem. First of allor maybe last of all, who knowswe have a denite ok. Thats

afrmation, folks. If you look carefully at the piece, youll nd a scrawled b. That makes the letters

spell (and in infraverbal works like this, one is loosened into all sorts of extra spellings) bokks, for

there is also a scrawl that might well be an s. Or: box. Slang for vagina. The union of a kok

with a bokks is ok. And, behold, the thing says that that is just whats there: kok and bokks, incorpo-

rated. As a burning collision, I might add.

Needless to say, the INCORPORATED adds a tone of absurdity to the piecea fuck as a formal

commercial enterprise. I nd a lyrical metaphoricality in this, howeverof human joy and animality

glorixplosively triumphing over (and out of) Money-Making Enterprise.

Bugs and (19) is a completely typical Bennett framed visual poem. His frame this time acts as a

fence around a backyard with bugs and stool snapping in the wind, but the frame also speaks

of the windas a gust that tugs. Spelled in a rectangle with multiple repeated letters enfran-

chises the engagent to spell out August, too, to make the odd-looking thing a full lyric of a serene

if breezy super-normal midsummer day, with bugs scrawled windily, lazily askew through it.

An untitled collaboration (233) between Bennett and Rea Nikonova is another good example of his

collaborative efforts. Its text is visually framed, in a highly unconventional way. Lust and luster

become sets of musical notes due to the staff they are onwhile infraverbally disconcealing the

light that cometh from lustand the uster, if we notice the f scrawled against the left side

of the staff. An extra R providing the staffs right side allows err to be disconcealed, which ts

with lust. For moralists, but also for anyone holding that emotions usually work against reason.

bake my is close to warm my, and gland can loosely be, in this context, and in the drawing

with its dangling thing between two sort of round things, a testicle. sHip as an anagram for Hips

would support this reading. So, come to think of it, does bake, a form of creation, as well as part

of a slang term for getting a woman pregnant. The Blaze (168), a piece Bennett collaborated with

Jake Berry and Jim Leftwich on seemed at rst asemic to mebut turned out to be straightforward.

The rst line, for instance, spells, language. Lots of sophisticated chatter about poetry here, with

The Blaze coarsely and . . . blazingly summing it all up.

Cover of K (227), to nish with Bennett, brilliantly represents collaboration at its best, and a possi-

bly unique artform I would call infraverbal illumagery. The work, a collaboration between Bennett

and Serge Segay, has no semantic meaning that I can nd, but works comically/lyrically/seriously

with punctuation, which is where, besides the interior of words, that infraverbalism acts. The yow

here is produced by punctuation marks larger than the letters theyre among, the reverse of the

expected. I.e., commas are kings here, lording it over the Russian and English textual matter. Except

for two large burning or otherwise disintegrating Ks. Perhaps, Im wrong, now that I reect on the

presence of the Ks. This piece may be a poem saying, OK. It certainly feels to me okay and bet-

ter. From one point of view, its a pair of algebraic expressions, which always indicate, to me, some

problematic portion of life rendered orderly, or negotiablesafe, in the better sense of that term.

An important value of the over-sized commas is that they almost demand that one take the heart

as a second punctuation mark. That draws one into fertile reections on just what it would do as a

punctuation mark. The top comma seems part of an eyeball overseeing everything else thats going

on. All is plussed, all is adding up (in exuberant color, I need to add)!

12

T H E O H I O S T A T E U N I V E R S I T Y L I B R A R I E S 14 A V A N T G A R D E P O E T R Y C O L L E C T I O N 15

Some Things Never Change (225 and 226). The opener of

Some Things Never Change is a pure visual poemwords in

a trash heap/bonre that shout, rattle, growl in synch with their

colors that the world is a mess and will stay that way. A fascinat-

ing mix of bluntness and aesthetic sophistication, annoyance,

and beauty. Part two of the set shows the scene subsiding in a

sharp reversal of the rst, for this time the word SURE hugely

takes up the middle of the page to sarcastically sneer, Sure,

things never change, while at the bottom of the page, two

instances of NEVER from Part 1 sandwich the word SAY to

result in NEVER SAY NEVER. All seems much more stable, too.

The question is, what have things changed to?

Space time llers seems a scrap heap of the wood used to

make the letters of the set I just commented on. There may be

no intended relation between it and the set, but it struck me as

an image of all the hectic changes that lled time and space

dismantled of meaningwith a few skeletons of clock faces

mixed inand an embedded title at the top (about to break up,

too, Im certain). Apart from whatever it may be saying verbally,

or semi-verbally, the work is a masterpiece of designalmost an

arch-lesson in how to deploy simple small and large rectangles

and circles to give the eye substantially more than a glances

worth of adventure.

I nd my continuum to arrive in signicantly new territory with

works such as Ficus strangulensiss In a very real sense,

Dickens (87): collagic visio-textual art. Strangulensis weaves

fairly consecutive, carefully chosen short passages from a text

about Dickens through similarly close-to-consecutive, carefully

chosen passages from a text that seems about a hard-boiled

detective. The result is such drollery as Dickens bullet drilled

a neat hole through his forehead while giving a fresh direction

and a rie popularize many aspects of the vest, and lifted the

window drape to peer into seasonal drinks. I consider this work,

despite its use of a landscape of some sort with an evergreen in

it as a background, to be decoratively visual only. The strips of

texts, and the two kinds of font, jiggle the engagent appropriately

awry, and enhance ones sense of unreality, of being in two

books, and time periods, and styles, etc., but they second the text

rather than combine with it. (Which is what they are intended

to do, and in no way makes them inferior to cut-outs used more

graphically. Role players: necessary, effective role players.)

Another cut-out-text work by strangulensis is one (truth)

pretension (92). It consists of four-inch lines from John M.

Bennetts poetry, carefully pasted together to form a neat

rectangle. Here, the dark lines between the lines of text

remind us to expect abrupt, probably preposterous jump-

cutsto set up the thrill of their making a poetic kind of

sense (when they do) as with ockets bulge with summer/

inside my lunch with you/ dream jaguar. Its the thrill good

found poetry causesa sudden sense that the universe is

orderly however we fuck it up. But funny, tooin both main

senses of the term.

With the work of poets such as the inimitable Joel Lipman,

we move along the continuum from purely textual collages to

collages of text and graphicwitness his Chemistry (186),

from a program for a poetry reading. Lipman is a master at the

splicing together of supercially incongruous visual images

and texts that drolly and provocatively, but also insightfully

investigate society. Here he whirls us into the forwards

and backwards RATADATADATADATA (several of the Ds

getting sufciently truncated to suggest Rs) of the conict

confusion vigilance adventure sensuality . . . chemistry of the

poetry reading that is its subject.

Another important American visual poet represented in the

collection is the collagist, Guy R. Beining. His Plumb (13) is

characteristic of his most frequent forays into visual poetry,

the word-play of plumb/ plume/ Plumm-/ et leading (via at

as and) to voice/noice, all combining with cut-outs and

drawing dexterously, if more than semi-wackily, to form a

design that would work as a superior illumage even if it were

not also speech. (Is that a horn or mouth the noice is curving

out of?) Connotativeness at its most extreme.

Some visio-textual collages, such as Spencer Selbys If the

moon is not high in the sky (236), Id call resonatingly non-

sequitirical cartoons. In this one, a girl is depicted deeply

walled inbecause, it is my guess, of the worlds insufcient

supply of poetry, as represented by a moon high in the sky.

But the cartoon participates, with its use of a generic 50s

instruction-guide face for the girl, in the ambience of Serious

Manuals for schools or the patrons of government agencies,

so we have the drollery of such a manual being distributed

to help people like the girl depicted come to terms with exis-

tences sometimes lack of beauty. It may be a found poem

that is, Selby may have found the drawing with the text

already with it, but I assume he added the text. I cant see the

text as anything more than a (great) cartoon caption, so have

trouble taxonomizing it as a visual poetry. (As if that matters.)

15

The fourth line makes this poem, for me, a love poemdue to

the heart and the E, O, and V of love beginning it

nuttily, as love generally is; strangely/mysteriously, too, as

love can be. With oooing (which has to suggest coooing,

I should think), whose os unletter visually as a full moon.

The little er in between lines two and four repeat the er

in line two, emphasizing erring/errant, as forests and love are,

and this poem. But I now hear it, too, as her, the object of

this poem.

The graphics gradually ambiance the situation as a tremble in

and out of words, mere words not being able to hold it by them-

selves. But the nal four lines are all words. Actually, they are

as much sounds as words now, the work becoming fully a trio

of the verbal, the visual, and the auditory. We have a shipwreck,

normally a disaster, but here something highly romantic. In fact,

its not a shipwreck, but something a ship wreaks. Better, its

something a shipwreak wreaks, which I imagine to be treasure

spilling onto a shore, the wreack becoming a wreath reminding

us that we are in a fest. Flowing free of any kind of strict sense,

we may remember the moon in the shape of the wreathand

the ringlets and mushroom that moonroom brings to mind

as it vibrates into its near-opposite, making me conclude that

the love-object of the poem is the moon. And repeats the rue

of the second line, as had marooning.

The other poems in the book interact with this one the same

lyrically wonderful way its lines interact with each other, and

fuse the verbal, visual, and auditory. The books last words are

rking of mushrrruemoons.

Another book in the library is a copy of K.S. Ernsts

Sequencing. Time On My Hands (74), one of its

characteristic pieces, consists of block letters precisely laid

out on graph paper, all of which emphasize the rectinlinear,

methodical, irreversible, tiny-square-by-tiny-square sadism of

Time distributing signs of ageing. Meanwhile, it makes a game

of deciphering its message, which makes it a fun poem as it

also slows down the read to allow the wry sadness the poem

expresses to seep more deeply into the engagent, and the ne

lines of the hands depicted to show themselves more vividly.

The game it plays also condenses its text down to its absolute

essentials, always a primary goal of the best poetry. In short,

Time On My Hands is a minimalistic gem, and entirely

characteristic of Ernsts charming sequencings.

I want to mention my own chapbook, An April Poem (107),

which is at the library, more as an example of sequential poetry

than any other reason, such poetry being common among

visio-textual artists. Actually, An April Poem is an example of

what Id term hyper-sequential poetry because it advances in

frames that vary only slightly from the ones just before them.

Hence, they very decidedly say, this is a sequence. Each

of its 16 pages contains just the word rainexcept for an

ephemeral text in a tiny font that escapes like a scent or smoke

from the dot of the i in rain several frames into the sequence.

The dot had begun black, the way all the other letters of rain

are, but gradually lightened until it was entirely whiteor

open. That is where the text, our dry spot within forsythia,

years ago, then delicately curls out of it in a manner intended

to suggest a memory, with something of the tone of a haiku. It

is present only for a page, whereupon the o gradually closes,

the rain continuing.

That this poem is also a book whose story happens with

the turning of pages is worth mention, too. The engagent is

more physically on a trip with it than he would be if it were on

one page, or in 16 frames all hung on a wall. I consider this

consequential. Many other visual poetry sequences share this

feature; conventional poetry does not, however many pages

one turns in reading them, for the engagent reads through

the turn of pages, and is hardly aware of it. The engagent of

a poem like mine, however, looks, then turns the page. Each

page releases a step of the work discretely.

Marilyn R. Rosenberg, a master of sequencing, has three

pieces in the Ohio State collection that come close to summing

up the visio-textual art continuum. Two comprise a set called

[un nome] by Michael Basinski

T H E O H I O S T A T E U N I V E R S I T Y L I B R A R I E S 16 A V A N T G A R D E P O E T R Y C O L L E C T I O N 17

The works text seems part of one of the two trails the other

shapes in the picture make. It also hangs in about the same

direction of the rest of the picture mostly does. So: the black of

the graphic portion of the work achieving verbal expressiveness?

Theres something in it of text as quotidianjust something there

with a small worlds other sloppy arbitrary shapes. The thing

forces the engagentme, at any rateto read the text into the

graphics, and see the graphics into the text. A mystery that wont

nally declare itself, but avoids irritating by being utterly, serenely

all curves except where the tiny letters make their sharp angles,

and by being pleasantly balanced (note, for instance, the rhyme

the bottom of the vertical shape at the far

left makes with its top). Im not sure where

this piece should go on my continuum.

I nd it an A-1 illumage with a text that

prevents it from staying for long in the

visual cells of ones brain. Strictly

speaking, its not a collage, but close

enough to put among the other more

legitimate collages on the continuum.

Among the works from the master of

rubbings, David Baptiste Chirot, is a visio-

textual collage-like page from Xerolage 32

(42) that resonantly depicts a man, or an

identity. I think of the latter because the

head resembles a ngerprint, the standard

mark of identity. Hints of ID numbers form

part of the image and letters. The word

on the head, Openone wonders if it

describes and commands. The head also can be thought of as

radiating SOME EVIL, those words, or something like them,

being spelled down it. Is the gure victim or victimizer? An entity

to reckon with, no matter which.

While in this part of my continuum murkily inhabited by collages

and strange mixes of text and text, or text and graphic, Id like

to point out my own Frame 2 from Dividing Poetry (108). A

combination of text and graphic, it is unusual in being also

mathematicalnot for containing numbers or mathematical

symbols or terms but in carrying out a mathematical operation:

long division. In it, a version of the word, words, which is

wearing away, is divided into poetry. A quotient thats a

distorted upside-down version of words, with a remainder of

(port) is the result. Two of the terms are mildly manipulated

visually to by themselves make the poem as a whole mildly

a visual poem. But the product of those two terms is, here,

wholly visual. A squaring of words, to put it roughly, yields

something full of color and hints of words, but no words

(unless one views the piece in context, in which case

certain words like rain would become evident).

The remainder, by the way, is intended to suggest that the

scene under poetry, the subdivided product, needs a

port, or something for the engagent to harbor in, in order to

become poetry. But the port should be subtly, parenthetically,

in it. Moreover, the port ought to be

verbalto increase the verbality of

the graphic.

More mixing (or collaging) of

expressive modalities including

the mathematical occurs with Alan

Sondheims equilibrium-upsetting

graph (239). In this, a text (and its

author) are mathematically located

on a sheet of standard graph paper.

A pluraesthetic, and pluraconcep-

tual, adventure, for sure!

Prominent theorist of avant garde

poetry, Steve McCaffery has a

quietly cerebral piece called

Land (204) in the collection that

also seems mathematical to me.

I take it to be a tribute to Gertrude Stein, for its message

can be interpreted as land is land is land. But it goes

further than Steins rose is a rose is a rose with its graphic

elements: layers of what seem to be blueprints of houses.

Or of lots, on top of the piece, in unfaded black ink, seems

what all the layers hope to attaina plot of land manfully

bounded, set apart, owned. It is also an island for the implied

protagonist of the piece, the one saying, I land. I also see

the piece as a sort of ow chart starting in a long ago large-

ness of indistinct possible land, ending after many haltingly

remembered turns in the small plot of the topmost layer.

An intriguing piece. Explicit labels that form a narrative,

a text genuinely fused with the graphic accompanying it

on the page to form a visual poem. In short, many are the

expressive modalities these pieces employ to connote.

From Re by David Baptiste Chirot

His Wife (16), by Bennetts wife, Cathy, has only two wordsits title, in fact. Is it not

just a graphic, with an embedded title, as I believe the previous work I discussed is?

Not that what we categorize an artwork matters as much as point oh oh two percent

as much as how much we enjoy it, but my answer here, after quite a bit of thinking,

and blank-mindedly owing with the piece, is, no. That the two words are clearly

concrete things oating above the rest of the work is verbally importantfor giving

the work an extra layer, an extra layer that contrasts vividly with the layer under it

as symbolic/ethereal/explicit versus concrete/earth-bound/connotative. It is visually

highly effective, too, for aiming the engagent (or viewer) at the same center of focus

that visual elements of the picture do, and as crisp formality versus the uncivilized

nature of the averbal elements of the work, but also picking up the thick darkness of

the wiry things in the work.

Of much greater importance, Ive come to believe, is the way the placement of the

two words disconnects them, makes them two words each to be considered by itself.

Ergo, taken in a context of the junkyard the graphic elements can connote, one can

interpret his as that which is his on a collision course with wife. I see a stick of

dynamite right where theyll meet, too! Rubble. To the right, a scribble of barbed wire.

Some wife this is. But wait. I made the previous comments while viewing a black and

white reproduction of the picture. The delicate oranges, yellows, and greens looked

grimily, grimly unpleasant there. But after seeing the full-color version, with those

colors, the yellows hinting of roses, Ive decided that the collision may be a happy

one. Certainly, I learned how much color can change the connotational quality of a

work. Whatever interpretation one leaves the piece with, one has to agree that it is

visually gorgeous. Art reminiscent of Rothko and Motherwellwith maybe a touch

of Renoir!

The text of Gyorgy Kostritskiis (152) is of/, is of/ Has a/ And goes, is a conundrum.

Something that is of something, possesses something . . . and goes. Is of, or is part

of something else, makes up something larger than itself. Words shorn of connec-

tivity like this, and in a nothingness or confusedness, force an engagent to either

leave quickly or seep into thoughts like these. And perhaps the idea of And going,

or connections being made. The blots declare themselves an illustration of this text

but clearly at the same time connect in no way with it other than geographically (by

sharing a page with it). The scene is primordial: the most basic of words in black

and white. Geography? I keep wanting to take the scene as a beach. Whatever it is,

it seems to enclose the textbut has an entrance, or exit, for it or other texts, at its

top. The highmost blob is difcult not to take as the sun, which makes little sense, but

gives the work a feel of archetypality that I also get from similar works of Adolph

Gottlieb. Can the text be considered the color of this picture?

His Wife by C. Mehrl Bennett

T H E O H I O S T A T E U N I V E R S I T Y L I B R A R I E S 18 A V A N T G A R D E P O E T R Y C O L L E C T I O N 19

While most of the pieces reproduced in this book are recent, it includes a historic piece of

visual poetry from the 60s, by d.a.levy, Notice (183), which is likewise an example of what

Ive been calling overlappetry, something levy pioneered in. It beautifully connotes the see-

through fragility of the text of his life, and its nervousness, and fragmentariness, as well as his

surrealistic, lyrical undauntedness on behalf of its best aspects.

Helmess The Void Enters (119) has recognizable words. Its also highly, importantly, and

vibrantly visualillumagistic, in fact. But . . . is the broken-off text, the void enters without the

recognition or centering of, a comment on the proceedings or part of the proceedings?

Without the recognition or centering of what? A rational minds planning? Reason? Art? Love?

Whatever, I accept the text as part of the proceedings. My take on the work is that the strips of

illumagery represent the chaos of the cosmos, the white space the cracks opening up between

strips reveals is the voidlabeled. I have a problem here: this void is expressing itself, but a

void should be incapable of that. The illumagistic strips cant be the void because theyre

obviously material, complex, dense, inhabited, rich, etc. (The work is monochromatic,

incidentally.) I have to confess that I cant understand this piece. But something wonderfully

creative is occurringdeeply into the archementality which is the origin of art everywhere.

Seattle visual poet, Nico Vassilakis, is, among other things, a wizard who often works in the

region of my continuum were now in, the one moving consequentially out of verbality toward

pure graphics, commonly constructing sequences. An example is the latter in the group of

four pieces from his book The Remington Vispoems (261). Each consists of nothing but letters.

The smallest letters form intersecting roads or tracks or seams that meet at or near larger

letters that beg to be readthe W N T R, for instance, saying written to me (as well as

suggesting points of the compass. At another intersection is the more exact anagram of POV,

or point of view, with YES. POEM AX is almost at a third, with CODE slightly suggested at

the fourth. These interpretations may seem over-strained, but its hard not to nd something at

such zzily centering loci. Which connotativeness is the point of such works.

In an untitled piece (176) by Jim Leftwich, we have archetypality, in my view: the Styx, glaciers,

50 million something. The deepening of knowing. A background explosionfrom whence the

mushroom seems to have shot up. A shape that looks to me like, among other probably equal

possibilities, half a mushroom. Also a maw upchucking or about to swallow. Something of a

whale is in it, too. In any case, there are hints in the piece of Carroll, LSD, Jonah, expeditions

to the South Pole.

I forgot to mention that this piece is a specimen of treated page. The identity of the book its

from would no doubt help us interpret it. Treatment of a page (or book, which one has to consider

most treatments of individual pages whether the artist has treated other pages of the book,

or all of them) adds something of importance. Theres something destructive involved, even

sacrilegious. But, when successful, like an archeological excavation. Theres also the interest

of combining the new with the known, the latter being the text on the page treated. Compare to

the blotted page previously discussed which looks roughly like this one, but has (apparently) a

newly composed text rather than a previously published text in it.

19

Thomas L. Taylor, one of several visual poets with work in this

collection who is a rst-rate photographer, tends mostly to

do captioned illumages like Selbys If the moon. Two ne

examples are wheres foldate-tore and thus no outer

doubts (251 and 254) from his Hermetic Series. But in the rst

of these, the non-representationality of the caption is so

similar (for me) to the non-representationality of the graphic

it shares a page with, that I consider it, in effect, overlap-

ping it (or being overlapped by it). Two moods interfusing to

form a third mood. This sets up, or is set up by, thus no outer

doubts, which has a representational image of a very ordinary

backyard view of neighboring backyards. This image overlaps

the non-representational one of wheres foldate-tore that

the memory carries over, thus becoming much more vividly

representational. Or, if we view the two works in the opposite

order, it is the non-representational image that becomes more

chargedly what it is. In either case, the fact that each work is

part of a series is vitally important. The captions team up to

smash the realities out of the representational images in the

series. The aesthengagent is left ooler in your mists or/ musk

(where) no outer is, according to wheres foldate-tore. That

is, he is pleasurably (it would seem) deposited in a kind of pure

subjectivity, the kind the best non-representational texts and

illumages can deposit one in because they provide plenty of

clues to soothingly sufcient coherences. Note well the hand-

printed addition to the text just quoted of and. That there is

more than the musk and the absence of outer, and so forth,

should not be forgotten. Bottom line: another singular

example of connota-

tionality taken to the

limit from the collection.

But a connotationality

prevented from going

wholly bonkers by the

careful rectangles and

obviously good crafts-

manship of the printing,

photography, and design

of the series. That is,

the works connote like

crazy, but from an

orderly elegance.

Scott Macleod has a series of wryly illustrated coined words

such as Lucifection (196), which has to do, Im sure, with

Lucifers res coming up through some kind of grate. To infect?

I consider these dada captioned illustrations, so appropriate in

this region of my continuum although not collages . . . perhaps

under or over the continuum.

Selbys Now What (237) breaks into a form of collagic visual

poetry I call overlappetry, which is one of most fertile types of

visio-textual poetry. Whereas conventional poets are sensitive

to the effects of one words two-dimensional propinquity to

another, overlappetrists can exploit a third layer, as well as

weld two or more words fully together. Selby, probably our

countrys leading exponent of the form, generally works, as

here, with two layers, one graphic, one verbal. The graphic

is usually something banal from some kind of how-to booklet,

as the one in Now What seems to be. The text is usually

from who-knows-where, and has no (conventional) connec-

tion to the graphic. In this one, some obviously ambitious but

ineffective man wanting to be bright, more intelligent has

succeeded in turning on the light bulb that his life is. What he

will go on to do with it as a result provides the punch line to

what is surely intended as a satire on earnest mediocrity. On

conformity, as wellon conscientiously doing what our society

deems the right thing, and achieving the good job, and the

other things our society reveres.

Derek Whites Scales of Evolution (266) is another

indenitely connotational specimen of overlappetry.

A side caption says the work depicts the Scales of

Evolution. We see that it goes from DEAD to E, for

energy, I take it, the opposite of deadness. Archeologi-

cal layering, references to Ancient Egypt, most tellingly,

sarcophagus. Something of the periodic chart of

elements is in it, and a strong avor of science, the

two, and other forms of reason, doing their best to

pattern history into coherence.

Whites Hoof Product (267) is somehow similar,

although the patterning attempting to bound it (or,

maybe, peg it) is a sloppy/silly word game, with

one non-word (or very unconventional word, if lue

is a word, at all). Intriguingly hued, with all kinds of

connotations drawing one to explore it.

Hoof Product by Derek White

T H E O H I O S T A T E U N I V E R S I T Y L I B R A R I E S 20 A V A N T G A R D E P O E T R Y C O L L E C T I O N 21

One of Crag Hills most interesting recent mostly asemic works

is a sequence called, directions, two frames of which are

shown here (137). Each frame forms a square with four square

cut-outs from magazines and the like, with occasional addi-

tions such as the hand-printed fragment in the piece to the left

of this set. Readable text is presentbut seems to represent

language rather than act as language. Hills squares work the

way all (good) collages do: they combine unconnected images

into visually potent designs that are also full of textual/textual

or textual/graphic accidents or seeming accidents that expose

unexpected meanings from matter incongruously adjoining.

The transformationally fresh touch here, though, is the

scientizing of the collages: Hill has made each a map, and a

four-quadrant analytical geometry graph. So, we have the

vitality of the tension between abstract order and sensual

verbal and visual imagery wildly decontextualized and

mismatched. Each frame of Hills sequence thus acts as a

metaphor for science: the imposition of an abstract, wonderfully

revelatory scheme on life and the near-life that even stones

can be said to represent (due to all the chemistry and physics

going on within them) . . . that nonetheless leaves their mystery

ultimately untouched. What actually happens is what happens

in Hills squares: the Mystery is enriched and domesticated

enough to prevent our being overwhelmed by it, but endures.

Peter Ganicks ds mu (97) is a collage mainly of cut-up texts

and what appears to be black paper to form a fascinating

collection of partial understandings uniting in the shape of . . .

a tree? Cursive and print suggesting a variety of voices. Close

to asemic although much of it can be read.

Sonata I, (143) by the late Bill Keith is entirely averbal, which

is odd, for he made a point of being verbal in his visio-textual

art. I would call it a linguiconceptual-visiopoetic impression of

what visual poetry is: music, order (the score being ordered),

text, focus and magnication, visual drama. . . . On reection,

I suddenly wonder if the work be considered semantic. How?

Well, its musical notation species objects in the world

musical tones of a certain duration. The notation is thus in

effect verbal. I withdraw the idea, but dont delete it, for it

suggests, I think, the subtleties and adventures of the many-

wheres visio-textual art can enter.

Equally averbal, but linguiconceptual is an untitled piece

of resonant primitivism from Hartmut Andryczuk (4). That

it is white on black makes it seem especially interestingly

backward, out of nightalso blackboard writing out of child-

hood. For one not knowing the works language, it is entirely

averbalwith language making paths through some kind of

jungle swamp.

Similar to the Andryczuk work is an untitled piece (232) by Rea

Nikonova, an interesting design using the letter Pand E,

with the P also standing in for bs, ds, and qs. Under

all this, with something resembling a thought balloon coming

out of it and enclosing gland is a box containing the word

trueplus a possible r to make eeling into reeling.

The r looks somewhat like an f, too, feeling, especially

right after true, is implied. Heeling, or obeying (ones

lustful instincts) is there, too, of course, as is healing.

directions by Crag Hill

The still water in the pieces text seems to me the text on the

page treated. Theres something here of a page as a seed that

has blossomed into the treated page.

The thrill of an effective found text is here, too. To repeat one

of my standard ideas yet again, theres something reassuring

about nding some new orderliness in a text that has been in

an accidentintimations that the universe may make sense,

after all.

Needless to say, deletional disconcealments are frequent in

treated textsi.e., procedures that hide or remove parts of

words to free words inside themas a jut of black exposes the

we read in we dread. And the black graphic as a whole

isolates still water above it to allow, almost force, us to read,

still water we read. And narrows the text to rivers, glaciation,