Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Atypical Pneumonia in Children in Islamabad Clinical Features and Response To Macrolides

Enviado por

aqazamTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Atypical Pneumonia in Children in Islamabad Clinical Features and Response To Macrolides

Enviado por

aqazamDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Atypical Pneumonia in Children in Islamabad: Clinical Features and Response to Macrolides

Mumtaz Hassan and Noreen Faiz

Original Article

Atypical Pneumonia in Children in Islamabad: Clinical Features And Response to Macrolides

Objective: The main objective was to determine the frequency of atypical pneumonia in hospitalized children and to provide a clinical approach for diagnosis and management of atypical pneumonia in children. Methods: This descriptive prospective study was carried out at Childrens Hospital, Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences from 1st January 2002 to 31st December 2002. Ninety five children having age 2 months to 10 years admitted through outpatient clinics and emergency with diagnosis of non-severe and severe pneumonia were recruited. Macrolides were given to the patients who failed to respond to other antibiotics after 72 hours. Results: There were total 206 children admitted in childrens hospital with signs and symptoms suggestive of non-severe and severe pneumonia during the study period. Out of these 95 (46.1%) children were declared to have atypical pneumonia. Forty-nine children (51.6%) were less than one year of age and 20 (21%) children between 2 to 4 years of age. Out of 95 children 71 (74.7%) were male, 93 (97.9%) had history of cough, 89 (93.7%) children had history of fever and 94 (98.9%) history of breathing difficulty. Forty (42.1%) children showed response to macrolides within five days. and 31 (32.6%) showed response after 5 days of therapy with macrolides and all these children were declared as therapy success. In twenty-four (25.3%) children there was no response to macrolides. Conclusion: Macrolides are the drug of choice for the treatment of atypical pneumonia in children. Keywords: Pneumonia, children, macrolides

Mumtaz Hassan* Noreen Faiz** *Chief of Pediatrics, The Childrens Hospital,Pakistan Institutre of Medical Sciences(PIMS) Islamabad **Senior Registrar of Pediatrics, Shifa College of Medicine, Islamabad, Pakistan.

Address for Correspondence: Dr. Uzma Afzal MBBS, FCPS, MCPS, Pakistan Senior Registrar of Pediatrics, Shifa College of Medicine, Islamabad, Pakistan. E-mail, uzma484@hotmail.com

Introduction

Acute respiratory infections (ARI) are common in children all over the world but are of particular concern for the developing countries. About 500-900 million episodes of ARI and 5 million deaths occur in a 1 year in the developing countries. Pneumonia is a common cause of childhood morbidity. According to World Health Organization (WHO), incidence for 2 pneumonia is about 10/100 children/year. Atypical pneumonia is characterized by an insidious onset and interstitial inflammation of the lungs, showing less virulent course and is associated with 3 lesser mortality than patients with typical pneumonia. In India, the incidence of mycoplasma infection is 15.5% 4 and Legionella infection 9.7%. Diagnosis of atypical pneumonia is difficult in developing countries and these groups of organisms do not respond usually to antibiotics used for community acquired. The definite diagnosis may be confirmed through culture, PCR and ELISA, which are expensive

and not practical for routine use in developing countries. Macrolides are the drug of choice for atypical pneumonia in children.

Materials and Methods

The study was a prospective, descriptive study conducted in the Childrens Hospital, Pakistan Institute st of Medical Sciences (PIMS), Islamabad from 1 January st to 31 December 2002. All Children admitted to wards through OPD and emergency having age 2 months to 10 years with diagnosis of Pneumonia according to WHO criteria were enrolled. The standard WHO criterion 5 to classify children with pneumonia is as follows: Non-severe pneumonia was defined as cough or tachypnea (with respiratory rate >50 breaths per minute for children aged 2-11 months ;> 40 breaths per minute for children aged> 12 months). Severe pneumonia was defined as cough or breathing difficulty with lower chest in drawing (with or without tachypnea as defined above).

Ann. Pak. Inst. Med. Sci. 2009 5(2): 70-73

70

Atypical Pneumonia in Children in Islamabad: Clinical Features and Response to Macrolides

Mumtaz Hassan and Noreen Faiz

Very severe disease was defined as cough or breathing difficulty with one or more danger signs: convulsions, drowsiness (altered consciousness), and inability to drink; severe malnutrition (grade III) and stridor at rest. The clinical criteria for diagnosing atypical pneumonia was cough and fever lasted for one week, given antibiotics other than macrolides for 72 hours and chest radiograph showing bilateral hilar infiltrates. The expected sample size was 100 children or 12 months whichever comes earlier. It was calculated 22 using the formula X=z alpha/2P(1-p)/D As no previous data available so P=0.5.Confidence level 95% and d=0.10 then the sample size was 96. All children admitted to the Children Hospital having age 2 months to 10 years were included in the study having WHO defined non-severe and severe pneumonia with the chest radiographs showing bilateral hilar infiltrates, as reported by the senior radiologist and did not respond to antibiotics other than macrolides for 72 hours. Children having very severe disease, underlying congenital heart disease, congenital lung malformations, bronchial asthma and malnutrition were excluded. Case notes with incomplete record were also excluded. Verbal consent was taken from the parents. Clinical and radiographic features were recorded in a pretested questionnaire. Each child had a complete history and a physical examination. Data was collected on the age, sex, weight, history of cough, breathlessness, noisy respiration and fever. A chest radiograph was taken on admission, after five days and after ten days of the study. Radiographs were reported by the senior radiologist .Children were monitored in the ward for response and re-evaluated within a week at outpatient clinic. For the purpose of analysis we made two groups of children, one who showed response to macrolides therapy, either upto five days or more than five days and the other who showed no response to macrolides therapy. We compared the baseline characteristics of these two groups (therapy success and therapy failure) to identify the risk factors associated with therapy failure. Our univariate analysis showed that there were no single variable were present, which showed statistical significant with therapy failure in the two groups The main outcome measure was clinical cure after 3 days of treatment. Clinical cure was defined as respiratory rate < 40 breaths/minute in 12 months and < 50 breaths / minute in children between 2-11 months of age and absence of the following signs of therapy 5 failure.

Ann. Pak. Inst. Med. Sci. 2009 5(2): 70-73

Inpatient Therapy Failure was defined as one or more of: Oxygen saturation 87 or less for more than 30 minutes when the child was calm. Presence of any danger sign. No improvement after 48 hours of therapy or deterioration when therapy failed. Data Management and Analysis: Data was entered using the SPSS version 10.0 data base program. Frequency of different variables, with mean, median and mode was calculated. These variables which were significant in univariate analysis were then put in multivariate model to determine the risk factors for therapy failure.

Results

During the study period of one year, from 1 st January to 31 December, 2002, 206 children were admitted at the Childrens Hospital, Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences (PIMS), Islamabad, with signs and symptoms suggestive of pneumonia. Out of these 206, we enrolled 95 (46.1%) children, aged between 2 months to ten years who were declared to have atypical pneumonia. The majority of the children, 49(51.6%) were under one year age. There were ten (10.5%) children between 2 to 3 years of age group and ten (10.5%) children were between 3 to 4 years of age group. The study result showed that out of 95 children of atypical pneumonia, 71 (74.7%) were male. The mean age of all the children diagnosed with atypical pneumonia was 29.7 months.

st

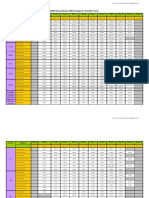

Table I: Demographic Indicators of atypical pneumonia children (n= 95)

Number Total no of children Children with atypical pneumonia Males Mean age <1 year 2-5 year >5 year 206 95 46.11 Percentage (%)

71 27.7 49 34 12

74.70

51.57 35.7 12.6

71

Atypical Pneumonia in Children in Islamabad: Clinical Features and Response to Macrolides

Mumtaz Hassan and Noreen Faiz

Table II: Frequency of clinical and radiographic features in atypical pneumonia in children (n= 95)

Total no of children Fever Cough Difficult Breathing Wheeze Lower chest indrawing Crackles Ronchi Chest X-ray Persistent Bilateral Infiltrate day 5 Bilateral Infiltrate day 10 95 89 93 94 44 70 79 70 92 63 93.70% 97.90% 98.90% 46.30% 73.70% 83.20% 73.70% 96.8% 66.31%

Table III: final outcome in atypical pneumonia children ( n= 95)

Variables Final Out come Response up to 5 days Response after 5 days No Response Number 40 31 24 Percentage 42.10% 32.60% 25.30%

Eighty-nine (93.7%) children had history of fever and 93(97.9%) had history of cough. Ninety four (98.9%) children had history of breathing difficulty while 44 (46.3%) children had history of wheeze during this illness. On examination, at the time of enrollment, 70(73.7%) children had lower chest indrawing. Seventynine (83.2%) children had crackles and 70 (73.7%) had ronchi. The mean respiratory rate at the time of enrolment was 56.5 breaths per minute (+10.25). The mean temperature at the time of o enrollment was 99.3 F (+1.26). At admission chest radiograph showed B/L infiltrate. At day five of treatment, in 75 (78.9%) children, bilateral infiltration still persisted while in 17 (17.9%) children the chest radiograph became worse. At day ten, 47 (49.5) children still had bilateral infiltration in the lung fields while in 16 (16.8%) children their radiograph became worse. In 32 (33.7%) children had clear chest radiograph on day ten of the therapy. Out of 95 children 40 (42.1%) children showed response to macrolides within five days and were declared as therapy success. However 31 (32.6%) children showed response after five days of therapy. With macrolides and these were also declared as therapy success. In 24 (25.3%) we observed no response to macrolides and were declared as therapy failures.

Table IV: Comparison of baseline characteristics of children with therapy success and therapy failure (n = 95)

Variables Male Age less than 3 years H/O Fever H/O Cough H/O Difficult breathing H/O Wheeze Lower chest indrawing Presence of crackles Presence of ronchi Therapy Success (n= 71) 53(74.6%) Therapy failure (n = 24) 18 (75.0 %) pValue 0.81

Discussion

Atypical organisms are responsible for sizeable number of cases of community acquired pneumonia in children. This study was based on the clinical approach for diagnosis and management of atypical pneumonia in children. There is limited data available in Pakistan. A study showed that 91% of children under five years 1 presented with acute respiratory infections. Analysis of one year record in this study showed the frequency of atypical pneumonia, defined on clinical criteria in Children Hospital and response to macrolides. In our study, a high incidence 68% of atypical pneumonia was found in hospitalized children less then four years of age. A similar study done by Clyde et al showed that atypical pneumonia may be severe enough to require hospital admission even in 6 relatively young patients. However the peak age for atypical pneumonia in majority of previous studies is 67 18 years, though all ages are affected. The reason for this difference is that 70% of admissions in children hospital are less than four years of age and We observed that higher frequency of atypical pneumonia in male children which may be due to bias. In our study, majority of children presented with fever, cough or breathing difficulty lasted for more than one week. Thom et al have reported majority of patients with atypical pneumonia were likely to present with 72

53(74.6%)

16 (66.7%)

0.62

67 (94.4 %) 70 (98.6%) 71 (100 %) 32 (45.1%) 54 (76.1%) 58 (81.7 %) 56 (78.9 %)

22 (91.7 %) 23 (95.8 %) 23 (95.8 %) 12 (50.0 %) 16 (66.7 %) 21 (87.5%) 14 (58.3%)

0.98 0.99 0.56 0.85 0.52 0.73 0.08

Against Male Against age more than 3 years

Ann. Pak. Inst. Med. Sci. 2009 5(2): 70-73

Atypical Pneumonia in Children in Islamabad: Clinical Features and Response to Macrolides

Mumtaz Hassan and Noreen Faiz

fever, cough or sore throat and the mean number of days from onset of symptoms until enrollment, was 8 longer suggesting a more gradual onset of disease. A child with wheezing is likely to have atypical organisms like Mycoplasma pneumoniae or Chlamydia 9 pneumoniae. In our study, wheezing was found in 46% of children which is higher as compared to another study Emre et al which showed 11% of children with 10 wheezing. This can be explained by the narrower airway in children less then one year of age. Majority of children had low grade fever and tachypnea mean temperature . These observations are consistent with the study which revealed patients with atypical pneumonia were less likely to have temperature 0 8 greater than 37.8 F and the examination of chest usually revealed tachypnea with crepitations and 3 wheeze. In many studies the patchy infiltrates on chest radiographs were the important feature of atypical pneumonia. The chest radiographs showed persistent homogenous infiltrates after ten days of therapy in 50% of our patients which is comparable to the study done in 11 Germany. One of the clinical criteria of atypical pneumonia in this study was the failure of antibiotics other then macrolides.Sometimes the diagnosis is not considered until after the child has failed to respond to 12 penicillin or cephalosporin. It was found that about three fourth of cases of atypical pneumonia had clinical cure with macrolides. Previous studies in Pakistan has shown the excellent 13 response of macrolides in atypical pneumonia. A similar study by Stahl showed that adding a macrolide for empiric coverage decrease the length of hospitalization or reduces mortality in atypical 14 pneumonia. Guidelines from the American Society and the Infectious Disease society of America suggested that the addition of a macrolide as an option if the 15 clinician suspected an atypical agent. Therapy failure in our study was 25.3% of patients and it is possible that these were cases with other bacterial or viral infection. The current study was based only on clinical features of atypical pneumonia and chest radiographs. However no laboratory tests were done. Culture is expensive and lacks sensitivity while PCR is not practical for routine use in developing countries. Because this study was done on a small scale in hospitalized patients, the hospital based data is

generally not adequate to assess the prevalence and presentation of the disease in a community, therefore large scale study is needed. There is needed to design more studies in pediatric patients with atypical pneumonia, to identify the practical approach for diagnosing atypical pneumonia. More emphasis should be given on newer laboratory serological tests to diagnose atypical pneumonia in children.

References

1. 2. Sarfraz T.Acute respiratory infections in children.Pak Armed Forces Med J 1996; 46:28-32. Selwyn BJ.The epidemiology of acute respiratory infection in young children. Comparison of findings from several developing countries. Rev Infect Dis 1990 ;( 8):S870-88. Salaria M, Singh M. Atypical pneumonia in children. Indian Pediatr 2002; 39:259-66. Chauhary R, Nazima N. Prevalence of mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydia pneumoniae in children with community acquired pneumonia. Indian J Pediatr 1998:65: 717-21. World Health Organization. Acute respiratory infections in children: case management in small hospitals in developing countries. WHO Geneva, 1990. Clyde WA .Clinical overview of typical mycoplasma pneumoniae infections. Clin Infect Dis 1993; 17: S32-36. Chugh K. Pneumonia due to unusual organisms in children. Indian J Pediatr 1999; 66:929-36. Thom DH, Grayston JT, Wang SP et al. Chlamydia pneumoniae strain TWAR, Mycoplasma pneumonia and viral infections in acute respiratory disease in a university student health clinic population. Am J Epidemiol 1990; 132-56. Turner RB, Land AE et al. Pneumonia in pediatric outpatients: cause and clinical manifestations. Pediatr 1987:11:194-200. Emre U, Robin PM,et al.The association of Chlamydia pneumoniae infection and reactive airway disease in children. Arch Pediatr Adolsc Med 1994; 148:723-32. Muller W,Bernsaw I,Hamann J,et al.Clinical and radiological findings findings in 78 children during the 1974/1975 mycoplasma pneumonia epidemia. Montatsschr K 1977;125: 634-3. Hammerschlag MR. Atypical pneumonias in children. Adv Pediatr Infect Dis 1995; 10:1-39. Tariq W, Yousaf M, Khattak AZ. Mycoplasma pneumonia. Pak Armed Med J 1994; 44:156-60. Stahl je, Barza M, et al. Effect of macrolides as part of initial empiric therapy on length of stay in patients hospitalized with community acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159:2576-80. Neidderman MS, Bass JB, Cambell Get al. Guidelines for initial management of adults with community acquired pneumonia: diagnosis, assessment of severity and initial antimicrobial therapy. Am Rev Respir Dis 1993; 148: 1418-26.

3. 4.

5.

6. 7. 8.

9. 10.

11.

12. 13. 14.

15.

Ann. Pak. Inst. Med. Sci. 2009 5(2): 70-73

73

Você também pode gostar

- Bald Eagle: by Taha Qayyum 5DDocumento11 páginasBald Eagle: by Taha Qayyum 5DaqazamAinda não há avaliações

- Guidelines Major Projects Aug-09 FinalDocumento16 páginasGuidelines Major Projects Aug-09 FinalaqazamAinda não há avaliações

- Quran Syllabus For Years 1-8Documento1 páginaQuran Syllabus For Years 1-8aqazamAinda não há avaliações

- External Calendar - Yr 1 To AL 2011-2012Documento2 páginasExternal Calendar - Yr 1 To AL 2011-2012aqazamAinda não há avaliações

- Dart PFL System Ds en v15Documento4 páginasDart PFL System Ds en v15aqazamAinda não há avaliações

- DEWA Regulations For Elect Insatallations 1997 EditionDocumento65 páginasDEWA Regulations For Elect Insatallations 1997 EditionaqazamAinda não há avaliações

- DartDocumento108 páginasDartaqazamAinda não há avaliações

- App Seba ReflectometreDocumento5 páginasApp Seba ReflectometreaqazamAinda não há avaliações

- Cable Fault Location Practical ExperienceDocumento59 páginasCable Fault Location Practical Experienceaqazam100% (5)

- Electrical Fault AnalysisDocumento44 páginasElectrical Fault AnalysisprotectionworkAinda não há avaliações

- Electrical Cable Fault LocatingDocumento42 páginasElectrical Cable Fault LocatingaqazamAinda não há avaliações

- Cable DiagnosticsDocumento42 páginasCable DiagnosticsaqazamAinda não há avaliações

- List of Doctor For ZurichDocumento5 páginasList of Doctor For ZurichaqazamAinda não há avaliações

- 1314 Ams Timetable t1 Updated 10.09.13Documento2 páginas1314 Ams Timetable t1 Updated 10.09.13aqazamAinda não há avaliações

- SCF Cable Annexure 2aDocumento1 páginaSCF Cable Annexure 2aaqazamAinda não há avaliações

- Technical Data SheetDocumento10 páginasTechnical Data SheetaqazamAinda não há avaliações

- Jeddah Cable Company, Industrial City 3rd Region, P.O. Box: 31248, Jeddah 21497, Saudi ArabiaDocumento1 páginaJeddah Cable Company, Industrial City 3rd Region, P.O. Box: 31248, Jeddah 21497, Saudi ArabiaaqazamAinda não há avaliações

- UAE Labour Law 2013 PDFDocumento61 páginasUAE Labour Law 2013 PDFAdarsh SvAinda não há avaliações

- Asad Waqar CVDocumento3 páginasAsad Waqar CVaqazamAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- 250 Watt Solar Panel SpecificationsDocumento2 páginas250 Watt Solar Panel Specificationsfopoku2k20% (1)

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocumento3 páginasNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentSunija SelvamAinda não há avaliações

- Pathophysiology of Rheumatic Heart DiseaseDocumento3 páginasPathophysiology of Rheumatic Heart DiseaseXtiaR85% (13)

- SCOPE OF PRACTICE FOR TCAM PRACTITONERS - V - 01Documento22 páginasSCOPE OF PRACTICE FOR TCAM PRACTITONERS - V - 01shakkiryousufAinda não há avaliações

- Program Thành TrungDocumento3 páginasProgram Thành TrungQuốc HuyAinda não há avaliações

- Hilti AnchorsDocumento202 páginasHilti AnchorsmwendaAinda não há avaliações

- TympanometerDocumento12 páginasTympanometerAli ImranAinda não há avaliações

- Whisper 500 Spec SheetDocumento1 páginaWhisper 500 Spec Sheetfranco cuaylaAinda não há avaliações

- Wind Energy Wind Is Generated As The Fluid and Gaseous Parts of The Atmosphere Move Across The Surface of The EarthDocumento3 páginasWind Energy Wind Is Generated As The Fluid and Gaseous Parts of The Atmosphere Move Across The Surface of The EarthEphraim TermuloAinda não há avaliações

- vdYoyHdeTKeL7EhJwoXE - Insomnia PH SlidesDocumento40 páginasvdYoyHdeTKeL7EhJwoXE - Insomnia PH SlidesKreshnik IdrizajAinda não há avaliações

- Imteyaz ResumeDocumento2 páginasImteyaz ResumeImteyaz AhmadAinda não há avaliações

- Collier v. Milliken & Company, 4th Cir. (2002)Documento3 páginasCollier v. Milliken & Company, 4th Cir. (2002)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Model CV QLDocumento6 páginasModel CV QLMircea GiugleaAinda não há avaliações

- Gazettes 1686290048232Documento2 páginasGazettes 1686290048232allumuraliAinda não há avaliações

- Brook Health Care Center Inc Has Three Clinics Servicing TheDocumento1 páginaBrook Health Care Center Inc Has Three Clinics Servicing Thetrilocksp SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Components of FitnessDocumento3 páginasComponents of Fitnessapi-3830277100% (1)

- Bcba CourseworkDocumento8 páginasBcba Courseworkafjwoamzdxwmct100% (2)

- Time ManagementDocumento1 páginaTime ManagementZaidi1Ainda não há avaliações

- Ielts TASK 1 ExerciseDocumento3 páginasIelts TASK 1 Exerciseanitha nathenAinda não há avaliações

- NPMHU, USPS Contract Arbitration AwardDocumento73 páginasNPMHU, USPS Contract Arbitration AwardPostalReporter.comAinda não há avaliações

- PROD - Section 1 PDFDocumento1 páginaPROD - Section 1 PDFsupportLSMAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To LubricantsDocumento12 páginasIntroduction To Lubricantsrk_gummaluri5334Ainda não há avaliações

- Design of Marina Structures and FacilitiesDocumento23 páginasDesign of Marina Structures and FacilitiesAhmed Balah0% (1)

- LeasingDocumento18 páginasLeasingsunithakravi0% (1)

- Contextual Marketing Based On Customer Buying Pattern In: Nesya Vanessa and Arnold JaputraDocumento12 páginasContextual Marketing Based On Customer Buying Pattern In: Nesya Vanessa and Arnold Japutraakshay kushAinda não há avaliações

- Aigen Zhao, PHD, Pe, Gse Environmental, LLC, Usa Mark Harris, Gse Environmental, LLC, UsaDocumento41 páginasAigen Zhao, PHD, Pe, Gse Environmental, LLC, Usa Mark Harris, Gse Environmental, LLC, UsaCarlos Ttito TorresAinda não há avaliações

- Employee Turnover ReportDocumento10 páginasEmployee Turnover ReportDon83% (6)

- Manoshe Street Takeaway MenuDocumento9 páginasManoshe Street Takeaway MenuimaddakrAinda não há avaliações

- RNA and Protein Synthesis Problem SetDocumento6 páginasRNA and Protein Synthesis Problem Setpalms thatshatterAinda não há avaliações

- Plumbing Specifications: Catch Basin PlanDocumento1 páginaPlumbing Specifications: Catch Basin PlanMark Allan RojoAinda não há avaliações