Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Why & How To Teach Art

Enviado por

Springville Museum of ArtTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Why & How To Teach Art

Enviado por

Springville Museum of ArtDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

i

Why & How

to Teach the Arts

ii

iii

Why & How to Teach the Arts

Contents

Artists & Artworks

Ten Lessons the Art Teach, by Elliot Eisner . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Posters of Quotes About Art) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4-8

(For more quotes, check the image CD

Art Lessons

The Nature of Art . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Art Is About Questions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

What An Artist Does . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

The Beginnings of Art . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Prehistoric Art: Timeline . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39

When to Start Teaching Art . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

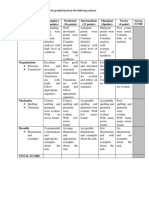

Why and How to Assess Art . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

From Art to Writing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

Art Therapy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53

Aesthetics: Painter or PachydermWho Can Make Art? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57

Quick Lessons

Art is a Kind of Thinking (4 drawing lessons) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

Blind Contour Drawing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69

Hand Design . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

Monogram . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77

Value Landscape . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

Art History Spotlights . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83

How to Integrate the Arts in other areas of the Curriculum . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93

Storytelling: Who, Where, How & Why . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95

The Why, What & How to Teach Dance Workshop . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101

Helpful Tips and Useful Information

Drawing Stages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 121

Why & How to Develop and Encourage Creativity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 125

Visual Art Tools . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 127

Word WallArt Related Words . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 129

iv

Copyright and Fair Use Guidelines for Teachers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 131

How to Legally Capture Images for Classroom Use . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 135

Free Programs for Editing Captured Materials . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 136

Utah Arts Council Grants and Free Resources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137

National and State Art Education websites . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 138

Key Art Education websites . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 139

POPS organization information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 141

On the CDS

A copy of the Utah State Office of Educations Rainbow Chart

Images for the Art History Lessons

Index of lessons from past Evening for Educator packets

v

Why & How to Teach Art

Artists & Artworks

Lee Udall Bennion, First Love

Lee Udall Bennion, Horses

Lee Udall Bennion, Photograph

Lee and Joe Bennion Rafting

bottom left, Lee Udall Bennion, Joe, at the Wheel

vi

Lee Udall Bennion, Self at 51

Lee Udall Bennion, Self in Studio (1985)

Lee Udall Bennion, Sketch of a Boy

Lee Udall Bennion, Snow Queen: Portrait of Adah

(1992)

Cyrus E. Dallin, Appeal to the Great Spirit

Cyrus E. Dallin, Don Quioxte de la Mancha

vii

Cyrus E. Dallin Elementary School, Arlington, MA

Cyrus E. Dallin, Portrait of John Hancock (1896)

Cyrus E. Dallin, Massasoit, Near Country Club

Plaza, Kansas City, Missouri, USA.

Cyrus E. Dallin with Massasoit

Cyrus Edwin Dallin, The statue of Moroni

Cyrus E. Dallin, Olympic Bowman League, National

Archery Association (1941)

viii

Cyrus E. Dallin, Paul Revere

Cyrus E. Dallin, Paul Revere in Boston

Cyrus E. Dallin Photograph

Photograph of Young Cyrus E. Dallin

Cyrus E. Dallin, Quote

Cyrus E. Dallin, Sacajewea from the back (1915)

ix

Lee Greene Richards, Sketch of Cyrus Dallin

Lee Greene Richards, Portrait of Cyrus Dallin

Louise Richards Farnsworth

Louise Richards Farnsworth, Capitol from North

Salt Lake

Louise Richards Farnsworth, Hay Stacks (1935)

Louise Richards Farnsworth, Mountain Landscape

(1940)

x

Louise Richards Farnsworth, Springtime (1935)

Louise Richards Farnsworth, Storm Clouds in the

Tetons (1950)

Lee Greene Richards, Lady with the Green Scarf

(Louise R. Farnsworth)

John Hafen, Indian Summer (1900)

John Hafen, Hollyhocks

John Hafen, Springville, My Mountain Home

xi

John Hafen, painting

John Hafen, photographed in his studio

John Hafen, Postcard

John Hafen, Quote

John Hafen, Sketch of the Valley

John Hafen, Springville Pasture

xii

John Hafen, The Mountain Stream (1903)

John Hafen, Teepees

John and Thora Hafen

Charles L. Smith, Portrait of John Hafen (1910)

Mahonri M. Young, Portrait of John Hafen

1

The arts teach children to make good judgments about qualitative

relationships.

Unlike much of the curriculum in which correct answers and rules prevail, in the arts, it is

judgment rather than rules that prevail. How qualities interact, whether in sight or sound,

whether through prose or poetry, whether in the choreographed movement we call dance or

in an actors lines and gestures-these relationships matter. They cannot be neglected, they are

the means through which the work becomes expressive.

School curriculum, however, is heavily weighted towards subject matter that gives students the illusion that rightness

depends upon following rules. Spelling, arithmetic and writing as they are usually taught are largely rule abiding subjects.

This is not so in the arts. The arts insist that understanding relationships is vital and that valuable relationships are

achieved when the mind works together with the childs feelings. It is when emotions connect

with thinking that lessons more fully impact the learner.

The arts teach children that problems can have more than one

solution and that questions can have more than one answer.

If they do anything, the arts embrace diversity of outcome. Standardization of solution and

uniformity of response is no virtue in the arts. While the teacher of spelling is not particularly

interested in promoting the students ingenuity, the arts teacher seeks it.

The arts celebrate multiple perspectives.

One important lesson is that there are many ways to see

and interpret the world. This too is a lesson that is seldom taught in our schools. For

example, the multiple-choice objective test celebrates the single correct answer. Thats

what makes the test objective. It is not objective because of the way the test items

were selected; it is objective because of the way they are scored. It makes no allow-

ance in scoring for the scorer to exercise judgment, which is why machines can do it.

The arts teach children that in complex forms of problem solving, purposes are seldom

fixed, but change with circumstances and opportunity. Learning in the arts requires the ability and a willingness to sur-

render to the unanticipated possibilities of the work as it unfolds.

At its best, work in the arts is not a monologue delivered by the artist to the work, but rather, a dialogue of sorts. It is a

conversation with materials, a conversation punctuated with all of the surprises and uncertainty that a stimulating con-

versation can make possible. In the arts, one hopes for surprise, surprise that redefines goals; and purposes are held with

flexibility. The aim is more than impressing into a material what you already know, but actually discovering what you dont.

Ten Lessons the Arts Teach

by Elliot Eisner

2

The arts make vivid the fact that neither words in their literal form nor numbers

exhaust what we can know.

Put simply, the limits of our language do not define the limits of our cognition. The reduction of knowing to the quan-

tifiable and the literal is too high a price to pay in defining the conditions of knowledge. What we come to know through

literature, poetry and the arts is not reducible to the literal and neither is the world in which we live.

The arts teach students that small differences can have

large effects.

The arts abound in subtleties. Paying attention to subtleties is not typically a

dominant mode of perception in the ordinary course of our lives. We typically

see things in order to recognize them rather than to explore the nuances of our

visual field. For example, how many of us here have really seen the faade of

our own house? I suspect few. One test is to try to draw it. We tend to look at our

house or for our house in order to know if we have arrived home, or to decide if

it needs to be painted, or to determine if anyones there. Seeing its visual quali-

ties and their relationships is much less common.

The arts teach students to think through and within a material.

All art forms employ some means through which ideas become real. In music it is patterned sound; in dance it is the move-

ment of a dancer; in the visual arts it is visual form, perhaps on a canvas, a block of granite, a sheet of steel or aluminum;

in theater its a combination of speech, movement and sometimes song. Each of these art forms uses materials that impose

certain demands on those who use them.

They also provide an array of distinctive opportunities. To realize such opportunities, the child must be able to convert a

material into a medium. For this to occur, the child must learn to think within both the possibilities and the constraints of a

material and then use techniques that make the conversion of a material into a medium possible. A material is not the same

as a medium and vice versa. Material is the stuff you work with and a medium is the form through which ideas are commu-

nicated using whatever materials have been chosen. A medium conveys choices, decisions, ideas and images that the indi-

vidual wants to express. The challenge for the child then is to take a materialbe it color, sound, texture or movementto

think within the limitations and possibilities of the given material and then to use the material(s) to shape their idea.

The arts help children learn to say what sometimes cannot be said.

When children are invited to describe what a work of art makes them feel, they must reach into

their poetic capacities to find the words that will convey their message accurately.

Talking about art makes some special demands on those discussing it. Think, for a moment,

about what is required to describe the qualities of a jazz trumpet solo by Louis Armstrong, the

surface of a painting by Vincent Van Gogh, the seemingly effortless movements of Mikhail Bary-

shnikov or the poetic theatrical language of William Shakespeare. The task is to express through

language the qualities that are oftentimes beyond words, hence the challenge is to say what can-

not be said. It is here that suggestion and association are among our strongest allies. It is here

that metaphor, the most powerful of language capacities, comes to the rescue.

The arts enable us to experience the world in ways we cannot through any other source.

The arts communicate meaning and it is through artistic experiences that we discover the expanse of what we are capable

of both perceiving and feeling. Some works of art have the capacity to put us into another world because the experience

is so powerful. The wish then in teaching literacy is not simply to help children learn how to read a book but to help them

use their reading skills to then imagine images while they read. In addition, literacy includes the ability to perceive our

world through many different senses: visual, tactile, kinesthetic and auditory. It is because of more diverse literacy that

children are able to understand the worlds artwork and subsequently, to access the joy, delight and insight those works of

art make possible. Ultimately, when a child can perceive and understand a work of artbe it a symphony, a play, a dance

or a paintingthey gain the skills to then perceive and understand the world in which they live.

3

The arts position in the school curriculum symbolizes to the young

what adults believe is important.

Without question, the curriculum of the school shapes childrens thinking. It symbolizes what

adults believe is important in order for the young to be competent in the world and tells chil-

dren which human aptitudes are valuable to possess.

The value of a subject of study determines both its presence in the curriculum as well

as the amount of time the school devotes to it. Indeed, the most telling indicator of the

importance of a field of study is not found in school district testimonies, but in the amount

of time it receives and when it is taught during both the school day and school week. Add

to these considerations the relationship between what is tested and what those test scores

mean to the overall evaluation of the student and you have a recipe for defining what

counts in schools.

Adapted from: Eisner, E. (2002). The Arts and the Creation of Mind, In Chapter 4, What the Arts Teach and How It Shows.

(pp.70-92). Yale University Press. Available from NAEA Publications.

Text abstracted from NAEAs pamphlet, Parents: Ten Lessons the Arts Teach. For more information call (703)

860-8000 or visit www.naea-reston.org.

4

5

6

|.crue- ~- .e|| ~- .cJ- ~e

.cr~:r rc |u~: e.:g- .:

r|e. ccu:.c~r.c:. e :eeJ

rc e~:J cu :~c. Jel.:.r.c:

cl |.re~cq rc .:c|uJe ..-u~|

J.e:-.c:-, ~:J .: -c Jc.:g

~:-.e r|e c~|| cl e-e~c|e-

lc r|e eccg:.r.c: cl u|r.-

|.re~c.e- ~:J .~q- r|e-e

|.re~c.e- c~: .c| rc

cc|ee:r e~c| cr|e.

~|u~J, _:-r. +;;-.

7

F

i

g

u

r

e

1

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

w

w

w

.

m

c

s

.

c

s

u

h

a

y

w

a

r

d

.

e

d

u

/

~

m

a

l

e

k

/

K

l

e

e

.

h

t

m

l

4

-

-

/

8

T

h

e

a

i

m

o

f

a

r

t

i

s

t

o

r

e

p

r

e

s

e

n

t

n

o

t

t

h

e

o

u

t

w

a

r

d

a

p

p

e

a

r

a

n

c

e

o

f

t

h

i

n

g

s

,

b

u

t

t

h

e

i

r

i

n

w

a

r

d

s

i

g

n

i

f

i

c

a

n

c

e

.

A

r

i

s

t

o

t

l

e

9

Why & How to Teach About

the Nature of Art

What is the Nature of Art?

Objective: Students will demonstrate an under-

standing of the Nature of Art by researching,

viewing videos, and discussing before writing

down a brief description of what they think art is

about.

State Core Links: Rainbow Chart, Elements &

PrinciplesThis lesson incorporates everything

the student knows about elements and principles

of art.

6th grade: Standard 4 ContextualizingObjective

2a, Explain how experiences, ideas, beliefs, and

cultural settings can influence the artists percep-

tion.

Materials: Video, Internet, handouts, paper and

pen, and a fiery imagination.

Process: Notice that we are not defining art. We

are writing a statement about the Nature of Art

and what the individual thinks art is about. I

usually start this process with a showing of a fine

video entitled What Is Art?, produced by Discov-

ery Education. This video attempts to make the

visual arts meaningful and accessible to young

students. It is an open-ended approach to the

elusive question, What Is Art? The video focuses

on how and why art is made and the role of visual

elements, artistic intention, mood and styles in

the creation of art. I have described this video in

case you have your own or find another that you

can use as well.

After viewing the video and talking about it, stu-

dents are asked to write down what they think

art is about. Have them address three ideas:

1. What do you think art is or what do you think is

art about?

2. What do you think is not art?

3. What do you think is the purpose of art?

Notice that anything they write is correct because

the question is what they think. We share these

ideas and then move on to what other artists and

writers have said about art. I pass out a paper

with some definitions and statements about art.

We read over these ideas and discuss them. A list

of quotations is included in the lesson. Students

are then given a chance to add to or change their

written ideas. A working understanding of the

nature of art is a life-long pursuit, so we need

room to change our minds.

After students have created a document stat-

ing what they think art is about or what art is

or what the nature of art is or all of the above, it

is time to turn the abstract concept into a work

of art. This can be done in any medium. I usu-

ally let students choose their medium with a due

date. It is also just fine to restrict the work to a

specific medium and incorporate the definition

into another objective lesson based on medium or

motif or historical style. As you know, an open-

ended assignment usually does not get finished.

To help students think of an example they want to

make, I suggest that they work in one of the four

motifs of Landscape, Portrait, Still Life or Design.

This work should be exhibited with their state-

ment about art clearly written and displayed with

their example of the statement. This can also be

done in class with each student having a chance

to share his or her work and statement with the

class. One of the ways I like to tweak this les

10

son is to have students share their statement in

class but assign the example to be done at home.

Those who return with a finished example can

display the work in the Hall Gallery.

Assessment: If a student starts his or her state-

ment about art, I think art is about then any-

thing they write is correct. If you want to be more

formal in grading this project, then you can grade

the spelling and grammar and creative construc-

tion of the document. You can also grade on the

depth of the students thinking about this subject.

Images: photo: a definition with an example.

Sources: I would like to recommend several

books about the nature of art. They dont particu-

larly agree with each other but the purpose of this

exercise or art for that matter, is not necessarily

to convince everyone of a singular, restricted idea.

What Is Art? by Leo Tolstoy the great Russian

novelist. This book was originally published

in 1898. It has been translated several times. I

recommend Richard Pevears translation because

it is currently in print and easy to find. This is a

must read on the nature of art. Tolstoy criticizes

the elitist nature of art in the 19th century and

rejects the idea that arts sole purpose should be

the creation of beauty arguing that true art must

work with religion and science as a force for the

advancement of mankind. He also explores what

he believes to be the spiritual role of the artist.

What Good Are The Arts? by John Carey. Carey is

a former English Professor at Oxford University.

His controversial thesis is that art is anything

that anyone has ever considered a work of art.

He puts forth an erudite and humorous argu-

ment that art is a social phenomenon and should

be treated, analyzed and valued as such. Art is

floundering in the abyss of relativism he writes,

Perhaps relativism is all we can hope for in a

world perceived by over 6 billion minds a day.

Provoking Democracy: Why We Need The Arts, by

Caroline Levine. Levine discusses the role of art

in a democratic culture and what roll art should,

could and does play. Yes democracies need art,

especially art they dont like or understandart

helps defend democracies from its worst excess-

es--the muting of marginal voices, the oppres-

sion of majority rule and the blind conformism of

consensus politics.

What Is Art For? by Ellen Dissanayake

But Is It Art? by Cynthia Freeland

Variations: In the original lesson we had stu-

dents in the 5th and 6th grade write what they

thought the nature of art was, what art was not,

and the purpose of art. A variation of this les-

son is simply to have students do just one of

these questions. At our school the students have

already become comfortable and confident in

writing about art. By the time they are in the 5th

grade, it is pretty easy to get them to do some

serious thinking and writing.

Another variation is to have students do some

research about what others think art is buy inter-

viewing other teachers, classmates (not in the art

class), parents, friends, and neighbors. Most stu-

dents are amazed that other teachers and school

workers wont even try to engage. We have been

doing this for some time, and it is only new hires

that wont play. Even if they cant get cooperation,

students can learn an important lesson about art.

Extensions: When defining art, most students

want to define visual art. They are in a visual

arts class, so it is obvious. There are at least 4

other genres in the arts and they each need some

defining also. Have students answer the same

questions, but specifically about Dance, Drama,

Music, and Electronic Media. Electronic Media

may or may not be its own genre of art. I think it

is, but we get to disagree in art without becoming

adversarial. OK?

Try having students write about the similarities

and differences in these different areas of art. You

will be amazed that the students understand how

similar all the different art forms are. This has

something to do with the fact that it is ALL ART.

Use Line, Shape, Color and Texture and see how

these concepts are used in each of the art genre.

11

This is Maddies fifth grade statement about the nature of art and her example.

12

Art isbeautiful, wonderful, amazing, its what you imagine and what you draw. Its not a pen

and a pencil, or watercolor with paper. Its what you see then write. Draw what you see its amazing.

If we didnt know about art or drawing, our life would be boring, we wouldnt be able to show our feel-

ings in different ways and it would be hard. I love art. I get to draw stories of my life and show how I

feel and that is art.

Some people might think art is a beautiful sunset but it isnt. Even if an artist is standing by it,

its not art. If the artist makes something about it or even says something about it, then thats art. Art

is something we do.

The purpose of art is to draw what you see in your mind so others can see it too. It is to draw

your feelings so others can feel them too.

This is Savanah Ps fifth

grade example of art and

her description of the

nature of art.

13

This is Zacharys statement about art and an example he choose to demonstrate

his statement. Sometimes we choose from other peoples artwork as a visual ex-

ample of what we think art is, isnt, and what is the purpose.

14

This is a decorated contour

drawing of Adison. It is an ex-

ample of Elizas statement.

This is the product of a lesson we

do on contour drawings and then

go in with textures and colors to

find tangent and adjacent spaces.

This is Elizas ffth grade

writing about art.

15

THE NATURE OF ART:

What is the nature of art? As redundant and

rhetorical as this issue may be, it becomes very

difficult to intentionally produce a thing that you

cant define or even discuss. If one does not know

what something isit is not possible to create it.

If your definition of art is anything you want it

to be, then there is nothing that is not art; there-

fore, there is no such thing as art because a thing

cannot exist without its antithesis. If you cannot

determine what is not art, you cannot rationally

know what is art. We are not trying to be exclu-

sive about art. We are trying to clarify a confus-

ing and nebulous idea that most people wont

pursue to a workable conclusion. Abdication,

what-ever, is never an empowering definition.

Remember that understanding the nature of art is

an ongoing, life-long pursuit. So, pursue it!

Rather than defending some didactic, arbitrary

definition of art that we have memorized, let us

engage in an ongoing dialogue on the nature and

meaning of art. Here are some starting points:

Art, n. 1. The quality, production, or ex-

pression of what is beautiful, appeal-

ing, or of more than ordinary significance.

RANDOM HOUSE DICTIONARY

To evoke in oneself a feeling one has experi-

enced, and having evoked it in oneself, then

by means of movement, line, color, sounds

or forms expressed in words, so to transmit

the same feelingthis is the activity of art.

LEO TOLSTOY

Art is the objectification of human feelings; and

the subjectification of nature.

SUZANNE LANGER in The Mind: An Essay.

Art is human intelligence playing over the

natural scene, ingeniously affecting it to-

ward the fulfillment of human purpose.

ARISTOTLE

the creative act is not performed by the artist

alone; the spectator brings the work in contact

with the external world by deciphering and in-

terpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds

his contribution to the creative act. This becomes

even more obvious when posterity gives its final

verdict and sometimes rehabilitates forgotten art-

ists. MARCEL DUCHAMP

you make something, anything, then you

show it to someone. If anyone notices that

they are looking at itthen that is art. Art

is a self-conscious social phenomenon de-

fined by the viewer as much as the artist.

KURT VONNEGUT

Art is a verb. It is an action, a process, and a

thing one does. Art is the physical, emotional,

spiritual, social and intellectual dance between

the artist and his medium. When the creation

dance is over, the phenomenon that the dance

produced is no longer art but becomes artifact;

evidence that art transpired in that place at one

time. The dance can be reengaged between the

viewer and the artifact and once again, art is hap-

pening, but it is difficult.

Art is a kind of thinking. Phenomenology is a

byproduct of the idea. A portentous idea poorly

executed is still a significant idea. A redundant,

meaningless idea, well executed is still meaning-

less. I reserve the right to change my mind with-

out telling you.

JOSEPH GERMAINE

16

17

Why & How to Teach That

Art is About Questions

Elementary Level

by Joseph Germaine

Objective: Students will demonstrate an under-

standing of the inquisitive nature of art by brain-

storming with the class to identify some thought-

provoking questions about art, the nature of art,

what part art plays in our real lives, where art

comes from, when we should start making art,

how to get ideas and how to get them out of our

heads and how you can tell a good idea when you

see it. These should be questions that the stu-

dents can then illustrate with images of their own

devising.

State Core Links: From the Rainbow Chart (5th

grade): Since this project is not directly about

the production of artworks, use the blue column

titled Explore, Contextualize: Discover, look at,

investigate, experience and form ideas.

From the State Core Curriculum in Visual

Art (5th grade), use Standard 2, (Perceiving): The

student will analyze, reflect on, and apply the

structures of art. Objective 1. Analyze and reflect

on works of art.

Materials: Groups of thinking humans, white

board to write on and then whatever medium the

students (or teacher) want to use for the illustra-

tion.

Activity: Life is about questions. It is the ques-

tions in life that drive our actions much more

than the answers. Answers come and answers go,

but the questions stay. Most questions are uni-

versal, but nearly all answers change over time,

geography, culture, age, gender, and inclination.

Significant questions cannot be answered quickly,

didactically, or simply. We want to practice creat-

ing that pointedly significant question that we can

spend a lifetime working on. Visual art is about

visual questions and visual answers as Music is

about sonic questions and sonic answers and so

on.

Have students discuss questions that they can ask

about art. Ask questions about the nature of art,

the meaning of art, the purpose of and the pro-

cess of art. Start with individuals writing down

questions and then cooperating in small groups

to get the best questions and then working as a

whole class to come up with no more than about

20 really good questions. My classes are from

Can blind people make art?

photo by Clara, 5th grade

Cat clay sculpture by Liz, 3rd grade.

Liz is completely blind

18

40 to 50 students at a time so

20 questions makes it possible

for several students to choose

the same question. If you have

smaller classes, make a shorter

list because we want to try to

get several students working on

the same question. These last

questions should be written on

the board. Notice that we have

not started trying to answer

the question. Each student will

choose the question he or she

wants to answer. They will group

together to discuss answers.

When they think they can answer

the question, they should gener-

ate a work of art. The artwork

will be an illustration of the an-

swer and probably also reference

the question.

Here is a list of questions about art generated in

class by 3rd thru 6th graders over many years of

doing the question project:

Is a beautiful flower art? What is art like? Can

art be ugly? What is the prettiest color? Can

something be beautiful and ugly at the same

time? Does art answer questions or ask ques-

tions or both? Can you have an answer without

a question? What is the best kind of art? Why

does everyone disagree about art? Is it ok to

disagree about art? Does art have be a picture of

something? Is it still art if it is not very good? Is

it ok to like someones art even if you think it isnt

really good? How do you know if you like some-

thing or not? Who gets to decide what art really

is? Who is the best artist in the world? What is

not art? Who invented art? Is photography art if

a machine makes it? If you trace something is it

still art? How old is art? Who was the first art-

ist? Why is it fun to make art, especially painting

and clay? Why doesnt everyone make art? Why

do old people quit making art? Is art just for fun?

How can an artist get money for making art? Why

is the art room so messy? Do you think God is an

artist?

When students are finished listing questions, give

them some time to discuss these questions in

small groups. Try to get everyone to participate.

The smaller the group the more participation

can be expected. Notice we did not say, have

students answer the questions. We are going to

discuss the questions. Maybe there is a better way

to ask the same question. Perhaps each question

reminds us of other questions.

We usually end this project here, without resolv-

ing many of these issues. The goal is to get stu-

dents to learn how to ask significant and insight-

ful questions. The well-crafted question lends

itself to the answer. This should be remembered

when crafting a test on any subject for your stu-

dents.

Assessment: All students who have participated

in the creation of making questions and then

discussing them have succeeded in this project.

For a more measurable assessment have students

write down what they think the best question

of the day was. Have them write it clearly and

succinctly. The question can then be graded on

grammar, punctuation, spelling, and insightful

content.

What is art about?

This is a watercolor stll life by Chandler, 5th grade

19

Sources:

DVD: Art Making and Meaning: Understanding

Through Questions, by Anne Coe and Michael Brol-

ly. This is a 143 minuet video, which is compiled

from 54 brief videos that address 17 significant

questions about art. There is also a companion

CD of interaction activities. This is an excellent

resource for older students. I use it for my 6th

grade classes and some of the more advanced 4th

and 5th graders.

BOOKS: The Art of Asking Questions, Get Better

Answers, by Terry J. Fadem; Open to Question: The

Art of Teaching and Learning by Inquiry, by Walter

L. Bateman; The Art Question, by Nigel Warbur-

ton; Smithsonian Q&A: American Art and Artists,

by Tricia Wright; Questions Kids Ask About Art &

Entertainment, by Grolier Limited; How to Talk

to Children About Art, by FranCoise Barbe-Gall;

Puzzles About Art, by Margret P Battin & John

Fisher; But Is It Art? by Cynthia Freeland; Letters

To Young Artists, by Peter Nesbett & Sarah An-

dress; Art and Fear: Observation On The Perils and

Rewards of Art Making, by David Bayles.

I know this is a lengthy reading list. They are all

good sources. Try the DVD, Letters To Young Art-

ists and Art and Fear. I know we are all busy but

my advice as a 33-year veteran in education and

a life-long learner is to find and make the time

and space to sit down with a book some time each

day. You will be amazed. Life is good!

Variations: A variation of this questioning

agenda is a game we play entitled, Question me

an Answer. In this game we take turns present-

ing an answer to the class and then see how many

questions we can invent that are compatible with

the answer. We also try to use humor, but it is not

expected that all questions will result in a funny.

Here is an example: Emily answered, Red. The

class asked, What is hot? What color is your

nose on a cold windy day? What does your Mom

see when you are naughty? What do you mix

with yellow to get orange? This could obviously

go on for a long time. The point here is to look at

the relationship between questions and answers.

Where can you

fnd art?

Pen and Ink and

Colored Pencil by

Caitlyn,

5th grade

20

This is a somewhat twisted, childish take off on

the ancient Geek style of debate know as the

Socratic method, which is a form of inquiry and

debate between individuals with opposing view-

points based on asking and answering questions

to stimulate rational thinking and to illuminate

ideas.

Extensions: To extend this project into the

production mode of art, we have students write

down the question they want to focus on and then

answer the question with an illustration. The me-

dium and motif of the illustrated answer can be

assigned or left up to the student. Some mediums

and styles lend themselves more easily to some

questions. Here are some examples:

Where do you get art ideas from?

Pen and Ink portrait by Walker, 5th grade

21

What is art about?

This is a watercolor

stll life by Morgan, 5th

grade

How can you see a picture of your thoughts in art?

Water color stll life by Megan, 5th grade

22

Can blind people make art? photos by Clara, 5th grade.

Self Portrait in clay by Liz, 3rd

grade. Liz is completely blind.

Dinosaur clay sculpture by Kailee, 9th grade.

Kailee is completely blind.

Dog clay sculpture by Paul, 5th grade.

Paul is partally blind.

Mr. Germaine teaches art to blind kids

who cant see. They come to our school at

night. I saw a table full of clay sculptures that

they were going to put in a show. My queston

was, Can blind people make art? because I

never heard of it before. This is my queston

and my answer. Now I know for sure.

Clara, 5th grade

23

Where can you fnd art?

Pen and Ink water color by Kate, 5th grade.

What does art sound like?

Colored pencil drawing by Max, 5th grade.

24

25

Why & How to Teach What

an Artist Does

Elementary Level

by Joseph Germaine

Objective: Students will demonstrate an un-

derstanding of the role of an artist in the real

world of art by looking at some media production

on What is an Artist? and engaging in a class

brainstorming process of listing and describing as

many artist jobs as possible.

State Core Links: Standard 3, Expressing,

Objective 2, Discuss, evaluate and choose

symbols, ideas, subject matter, meaning and

purposes for students own artworks and

Objective 3, Explore video, film, CD-ROM,

and computers as art tools and artworks.

Standard 4, Contextualizing, Objec-

tive 2-a, Collaborate in small groups to

describe and list examples of major uses or

functions and Objective 3, Recognize the

connection of visual arts to all learning and

Objective 3-a, Collaborate in small groups

to discover how works of art reveal the his-

tory and social conditions of a nation.

Materials: Video, I Want To Be An Artist by

CrystalProductions or any other similar produc-

tion on the nature of art in the real world. See

Bibliography. Writing materials and time.

Process: This lesson is oriented around the ques-

tion, What does an artist do in the real world?

We want to get past the idea that art is just for

artists. The thesis here is that everyone en-

gages in the world of aesthetic creation (art) all

of the time. We want to debunk the idea that only

cloistered-off tortured painters make art. The

traditional stereotype of an artist does a lot of se-

rious disservice to all of those who engage in the

world of art daily as part of their career or part of

their daily life.

We show the video I Want To Be An Artist to

the class. This is a short video production, which

highlights several types of jobs in the art world

that arent necessarily the traditional painting

and sculpting jobs. Art Gallery Owner, Restora-

tion Artist, Art Teacher, Computer Artist, Pho-

tographer, and Fashion Designer are a few of the

careers mentioned. After viewing this or a similar

video, students should discuss several terms like

career, art, artist, job, and hobby. At this point

students should be led in a brainstorming process

to list as many ways to be an artist as they can

imagine. They should also write down how a par-

ticular job uses art. For some classes, making it a

slightly competitive thinking process might help

motivate the students. I divide the class into four

workstations and have each engage in a discus-

sion about artists work. They choose a scribe to

write down the ideas, and then we make a master

26

list on the board. Sometimes we do this individu-

ally rather than making it a group process. But

we still end up with a master list on the board.

Some coaching might be needed to elicit some

out of the box thinking.

Years ago I was shown an article in School Arts

that said that at NASA (National Aeronautics and

Space Administration) there were nine artists for

every engineer. The article pointed out that the

real job of NASA was not to go to Mars but to get

money from Congress to finance NASAs research.

This means they produce a lot of advertising,

pamphlets, films, animations, and re-enactments.

This is an unexpected example of what artists do.

Here is a partial list of art careers thought of by

fifth graders:

Hair stylist, Grounds keeper, House painter, Tree

pruner, Sign painter, Janitor, Housewife, Chef,

Construction worker, Seamstress, Makeup art-

ist, Actors, People who announce the news on

TV, Dance teachers, Music teacher, Fifth grade art

teachers, All the Elementary teachers, Whoever

makes all that stuff the teachers decorate their

rooms with. People who make Christmas Tree or-

naments, Who make Christmas lights, Christmas

card makers, Anybody who decorates a Christmas

Tree, Movie set designer, T-shirt printer, advertis-

ers who make commercials, The guys who paint

the lines on the roads, Farmers who stack hay

neatly, Saddle makers, Jewelry makers, Rock and

roll stars, Guitar makers, Costume makers, People

who design labels on food, People who print the

art posters in our classroom, The guys who built

our school and put the tile floor designs in, The

people who design and invent flags for coun-

tries, The musicians who write national anthems,

Anybody who plays an instrument, Workers in an

Art Museum like the leaders and the ones who

walk around and tell you about the art and the

lady who says hello at the front desk, The people

who make the handouts and notes we take home

almost every day, People who make basketballs

and other sports equipment, The artist who

thought up the Nike design and put it on my shoe,

My mom when she curls my hair, Me when I brush

my teeth and wash my face, Guys who think up

wallpaper, Whoever makes new colors of paint,

The people who make those little pieces of paper

at the paint store with all the colors of paint and

the funny names, The artists who make toilets,

The car guys who figure out how to make fancy

letters in metal to put on cars, Font makers for

your computer, Gardeners who grow house plants

to decorate your house.

Well, the list is much longer and takes a full day

to compile. With 180 fifth graders we make a list

of over 300 jobs and careers that a person who

makes art can do. Of course this all depends on

how you want to define art and artist. Our defini-

tion is obviously an inclusive one rather than an

exclusive one. It always seems more reasonable

to define a thing by what it is rather than what it

is not.

Assessment: If you need to grade this project

on a graduated scale then the obvious way is to

give the group with the greatest number of con-

tributions the highest grade and the individual

students who contribute the most the highest

grade. Although, one cutting, insightful, poi-

gnantly poetic answer may be worth all the other

answers combined. Be careful of the quantitative

paradigm. An important part of assessment for

the lesson would be to identify and recognize any

27

Students having fun making the list.

The list in progress.

student who does not participate and develop a

strategy to recruit that student into the process.

It has been my experience that the best tools we

have for convincing students to engage in the

work of art are other students who are engaging.

Sources: I Want To Be An Artist, a VHS video by

CrystalProductions. This is an excellent starter for

a discussion on careers in art.

What Is Art? a VHS video by Clearvue & SVE. This

video does not answer the title question but it

does create a good starting point for discussion.

Art City 1, 2, & 3, a series of DVDs directed by

Chris Maybach. Each of these DVDs look into the

life and work of real contemporary artists and

discusses the hows, wheres and whys a person

pursues a life and career in the arts by going into

individual art studios of various artists in various

medium.

Art:21, in both VHS and DVD. This is a look at dif-

ferent types of art in the 21-century and how the

contemporary world of art is expanding to in-

clude many art forms that have traditionally been

excluded from the Fine Arts genre.

I Can Fly, Volumes 1-5, VHS video. This is an excel-

lent series for young students, which crosses over

between the disciplines of Dance, Music, Perfor-

mance, Drama, Literature, and the Visual Arts. It

also focuses on three different artists in each of

the volumes and two or more dance and music

performers.

Variations: This lesson can be as simple as hav-

ing students take notes (which they always do in

my class) or as complex as dividing into competi-

tive teams and keeping score on the number of

art career options that can be catalogued.

Extensions: Here are two other ways to use

this brainstorming process to discuss the nature

and application of art without it being a didactic

lecture.

WHO DOES ART?

1. List all the things you did today that were

some kind of art. Combed my hair, chose colorful

clothes, made my bed, whistled a tune, danced a

jig, wore a tie, chose a hat, planted a tree.

2. Follow Mr. Huntington our custodian around

for a day and write down everything he does that

looks like art. Swept the sidewalk, mowed the

grass, cleaned up a mess in the hall, straightened

a picture. Try this on your teacher, your parents,

and your principal.

There will be those who dont see these daily

activities as ART in any traditional way. There is

a sense that art is artifact, and that it is primarily

painting and sculpture. To see how this narrow-

28

ness prevails, make a list of the famous artists

who come to mind. Most folks will notice that

these famous artists are primarily white, Europe-

an, male painters with a sculptor thrown in there,

perhaps. Of course this is not true for everyone,

but then everyone does not concern his or her life

with these issues.

Student Examples:

Artsts design clothes like under ware. I dont really

want to design under ware when I grow up. I want to

be a basketball player like Michael Jordan. He de-

signed his own under ware and that is a kind of art

and a job in art so I guess if it is ok for Michael Jordon

it is ok for me. Fashion designer is a career in art.

Parker, 5th grade.

If there is an underlying sense of beautification

and focus on the visual world in these daily activi-

ties, then with just a little flexibility and inclusive-

ness, much of what we do will fall comfortably

within the greater aesthetic world of manipulat-

ing visual elements to express ones concern and

appreciation for others and oneself. Art is about

the way things look, the way things are, and the

way things might be.

29

A job in art is to design and make labels for food. When you buy something in the store it has a label and

artwork all over it. Somebody has to get the idea and design the wrapper for cookies. This is my idea for

a cookie wrapper. The two litle faces in the Os are the cartoon characters that I made up for the comic

strip project. I think it would be fun to be an advertsing type artst when I grow up but who knows. Im

stll kind of young. Paige, 5th grade.

A good job for an artst is to be a model. Mostly artsts take the picture or paint it but being a model is art

too. It is a kind of drama like actng. It seems like fun and sometmes I model for photographers. When I

grow up I would rather be the photographer. Emily, 5th grade

30

This is a logo for a worldwide telephone company. Some artsts design logos for compa-

nies. Thats what this is. Braden, 5th grade.

31

Jewelry designer. This was thought of and made by a jewelry

designer. People who design jewelry are artsts and they make

a lot of money. This is some jewelry that I designed and made.

Sometmes you can just design an idea but if its a good idea it

is fun to make it too. I want to make and design jewelry when I

grow up. Savanna, 5th grade.

32

WHERE DO YOU SEE ART?

1. List all the things in this classroom that were

made or designed or thought of by artists. Is it

good art or not? How does it help you? This

can be done individually or as a group or as a

graded quantitative process.

2. Lets pretend there isnt any art anywhere.

What would our school look like? What would

our town look like? What would our homes look

like? What would we look like? What would you

miss most? Make a list.

More Extension:

The obvious next step is to have students choose

You might not think it is art

when your Mom fxes your hair

but it is. Some artsts who do

hair make a lot of money doing

it. It is called a Hair Stylist. It

is not like paintng or drawing

but they use lines and shapes

and textures and sometmes

even color to make things more

beautful and interestng. To me

that is art. This is a hairdo that

my Mom gave me. Hair styl-

ists have to study at a school

to learn how to do their job. I

think it is a good career in art

one of the careers in art and create a work of art

that corresponds with that career. If this is some-

thing that cant be done in class, have students

document their project with photos.

33

Why Teach About the

Beginnings of Art

WHY BOTHER TEACHING ART?

In an effort to discuss why we bother with the

expensive and time-consuming discipline of ART

in the public schools we need to know first, some-

thing about the nature of art, second, what part

art plays in our real lives, third, where art came

from, fourth, when we should start sharing the

joy in the production of art with our children and

fifth, some strategies as to how we can go about

this awesome task.

Art is distinctively human. To study art is to study

what it means to be a human being. Art is a social

phenomenon. To study art is to study about our

relationship with our self and all other humans.

Art includes all aspects of human existence. To

learn about art is to learn about our human place

in the rest of the non-human universe. To be-

come aware of, comfortable with, coherent in,

and skilled at art is to become human, which is

significantly more than just existing. It is being

ALIVE! To engage in the aesthetic paradigm is

to engage in meaning. If aesthetics is about the

search for beauty, then aesthetics is the only place

in the educational world where we can discuss

what causes beauty, what to do about it when we

discover it, what it means, and why is it appropri-

ate that we dont all agree.

WHENCE ART?

Whence: From what place, source or cause.

Art is a part of the human condition. In fact it is

the definitive part of the human condition. It is

what makes us human. It is probably the only

thing that humans do exclusively. What do hu-

mans do that is distinctively human? Reproduce.

No! War and violence? No! Eat, travel, hunt,

hide, and horde things?no, no, no! How about

communicate by generating sounds? No! Again.

Perhaps the only thing that human beings do for

which there is no obvious counterpart in the rest

of the animal world is to find beauty and share

our responses to it with others. All academic

disciplines are narrow spin offs of the human

need to observe nature (by the way, we are part

of nature so observing nature includes ourselves

and others) and record our response. Art is the

oldest academic discipline and integrally inter-

twined with ancient religion. Art is the only pre-

literate academic study. Literacy is a form of

visual art, that is, it is an arbitrary symbol system

drawn with lines and shapes to covey a predeter-

mined meaning. We can use these squiggly lines

Close-up of horse heads from the Chauvet Cave

htp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Chauvethorses.jpg

public domain

34

and shapes to communicate novel and personal

ideas and feelings and descriptions of our world.

Sounds a lot like abstracted art to me.

The following is a brief and incomplete discussion

about where art comes from. We are focusing on

the visual arts because the record is available, but

there is very strong evidence that Music, Dance

and Drama (story telling and ritual) is at least as

old as visual art and perhaps older. It is just very

difficult to document the sound of prehistoric mu-

sic although some of the oldest rock art we have

from Spain shows figures that are either dancing,

hunting or fighting. Perhaps it is all part of the

same thing. Some of the oldest artifacts found are

musical instruments. We will start with written

language to demonstrate that visual communica-

tion is much older than literacy and is at the root

of all reading and writing. To ignore the legacy

of visual art is to deny the root source of all the

academic disciplines, which rely so exclusively on

literacy. Why do we start preschool children on

PICTURE BOOKS?

The earliest written language we know about is

Cuneiform from the Sumerian culture in Mesopo-

tamia, (or possibly early Egyptian) about 34,000

to 3200 BCE (5000 year ago). Cuneiform was

drawn with a wooden stylist on clay tablets (see

image, bottom left).

Bone and ivory tags, pottery vessels and clay seal

impressions bearing hieroglyphs unearthed at

Abydos, Egypt have been dated to between 3400

and 3200 BCE, making them the oldest know ex-

amples of Egyptian writing. The Tags, each mea-

sure 2 by centimeters and containing between

one and four glyphs were discovered by excava-

tors from the German Archaeological Institute in

Cairo in the pre-dynastic ruler Scorpion Is tomb.

For some great information about the earliest

hieroglyphs I recommend an online article by

Marsia Sfakianou.

Drawing of hieroglyphic ivory tle. Original can be

seen at

htp://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/235724.

stm

another tle is available at

htp://www.homepages.indiana.edu/041301/im-

ages/scorpion.jpg

Lef, Cuneiform tablet image htp://en.wikipedia.

org/wiki/File:Cuneiform_script2.jpg

Library of Congress, public domain

35

The Chauvet Cave is in southern France. It con-

tains mans earliest known cave paintings. It was

discovered in 1994. It is considered one of the

most significant prehistoric art sites in the world.

Cave paintings were being made about 32,000

years ago at Pont DArc, France.

htp://www.culture.gouv.fr/culture/arcnat/chauvet/

en/ source for images

Chauvet Horses, large

htp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Chauvet_cave,_paintngs.JPG

Charcoal and colored earth pigment paintngs and relief carving from Pont DArc, France.

Paintng from the Chauvet cave, replica in the Brno museum Anthropos. 31,000 years old art, probably Au-

rignacien. The group of horses probably does not picture a herd of them, but some kind of etological study,

showing, from lef to right, calmness, aggression, sleep and grazing.

(2009-05-22)Author, HTO 22 May 2009

Cave hyena paintng found in the Chauvet cave;

now known to be 32,000 year old

htp://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:20,000_

Year_Old_Cave_Paintngs_Hyena.gif

Author, Carla Hufstedler 27 September 2006, 15:25:51

36

Lion-headed fgure

htp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Lion_man_photo.

jpg Lion_man_photo

Author, Gaura, 2007(2007)

public domain

This lion headed figure, first called the lion man

and later called the lion lady of the Hohlenstein

Stadel Cave, is an ivory sculpture that is the oldest

known zoomorphic (animal-shaped) sculpture in

the world and one of the oldest known sculptures

in general. The sculpture has also been interpret-

ed as anthropomorphic, giving human character-

istics to an animal, although it may have been the

image of a deity. The figurine is determined to be

about 32,000 years old by carbon dating meth-

ods. It was first discovered in 1861 in a cave near

Swabian Alb, Germany.

The Lion Man, Water Bird and Horse Head

sculptures from the Swabia province of Germany

are dated between 35,000 and 40,000 years ago.

See images at http://www.ice-age-art.de/an-

faenge_der_kunst/fels.php

http://archaeology.about.com/od/upperpaleo-

lithic/ss/hohle_fels.htm has horse head, water

bird, and Venus

The 40,000 year old Venus of Hohle Fels, from

Schelklingen, Germany, was discovered in 2008.

(www.thelocal.de). This ivory carving was found

near Schelklingen Germany and is from the begin-

ning of the Upper Paleolithic, which is associated

with the assumed earliest presence of Homo sapi-

ens (Cro-Magnon) in Europe. It is the oldest un-

disputed example of Upper Paleolithic art and fig-

urative prehistoric art in general and is about 2

inches tall.. Near this area in Germany have been

found over 20 other carved artifacts including a

35,000 year old flute carved from a vulture bone.

Because these artifacts are made of organic mate-

rials (bone) they can be easily dated using carbon

dating processes. (largest image at http://john-

frederickwalker.files.wordpress.com/2009/05/

hf_06.jpg found November 4, 2009. If no longer

available, use Venus of Hohle Fels as search term

in image search such as google.com.

The oldest pottery found to date is about 18,000

years old found in a cave at Yuchanyan in Hunan

province in China. By determining the fraction

of a type, or isotope, of carbon in the bone frag-

ments of the site and residual carbon in the clay

body, the specimen were found to be 17,500 to

18,300 years old. The piece has incised decora-

tions on the surface. (tywkiwdbi.blogspot.com)

You can see (and get a personal copy for use in

37

your class) from http://www.hnmuseum.com/

hnmuseum/eng/whatson/exhibition/kg_2.jsp

The oldest art objects found so far are a series

tiny drilled snail shells about 75,000 years old--

that were discovered in a South African cave.

(http://images.livescience.com/images/060622_

jewelry_02.jpg )

This is pretty old and whether or not it is art is

a lively discussion. The age can only be pushed

back further. Long before what we would recog-

nize as culture or civilization our ancestors were

making art. This historical and chronological ap-

proach is intended to demonstrate to those who

resist Art Education as frivolous, non-academic

or just play that art is the basis of all we teach

and completely relevant to our real lives. Most

of what we know about whom we are and where

we came is documented in the arts. Try to imag-

ine history without artworks or literacy without

drawing lines and shapes to make letters and

words or science without visual diagrams to show

us what Science is trying to say.

The oldest writing we have is about 5,000 years

ago and it seems to be inventory lists and legal

documents. Who would have guessed that law-

yers invented literacy? Initially, literacy was a

secret and one had to hire a scribe to write a

document and then hire another one to read

it. Until the 19th century, universal literacy was

not an idea anyone espoused. It is irrational to

believe that the human experience started with

literacy. It is irrational to think that the academic

disciplines of literacy, math, science, history or

social studies can exist without the endemic hu-

man experience in visual communication. Art is

the only preliterate discipline in the school cur-

riculum. We dont have to read or write to do art

but we do have to do art to be able to write and

read. We learn by art, we teach by art, we work

by art, we play by art and we love by art. It there-

fore seems obvious that we need to include a

far-reaching, discipline based authentic art incre-

ment into all subjects at all times and at all levels.

We also need to secure a place in the curriculum

where the arts can be taught as primary and not

just an effective way to teach another subject. Art

is the educational glue that connects all things.

It is the historical and systemic glue of our lives.

The aesthetic life is life. We live by beauty, just

ask any Navajo or Polynesian.

Other examples of prehistoric art:

Egyptan Funerary Stele

htp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Egyptan_funer-

ary_stela.jpg

Graeco-Roman period hieroglyphs htp://upload.

wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/25/Egypt_Hi-

eroglyphe4.jpg

38

htp://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/na-

ture/235724.stm

One of the Earliest Known Realistc Representatons

of a Human Face Circa 23,000 BCE

Venus_de_Brassempouy

htp://upload.wikimedia.org/

wikipedia/commons/2/26/Ve-

nus_de_Brassempouy.jpg

Author, PHGCOM, 2009 pho-

tographed at the Musee

dArcheologie Natonale

Public domain

The Narmer Palete, shown below, also known as

the Great Hierakonpolis Palete or the Palete of

Narmer, is a signifcant Egyptan archeological fnd,

datng from about the 31st century BC, containing

some of the earliest hieroglyphic inscriptons ever

found.

htp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:NarmerPalete_

ROM-gamma.jpg

photo by Captmondo, gamma adjusted to bring out

more detail at lower resolutons

Public domain

Other Good Sources:

htp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prehistoric_art good

source for info and images

htp://www.spiegel.de/fotostrecke/fotost-

recke-22586.html 5 pieces small ivory sculptures

htp://www.spiegel.de/internatonal/zeit-

geist/0,1518,489776,00.html

35,000 year-old art

Timeline htp://www.historyofscience.com/G2I/

tmeline/index.php?category=Art+

39

Elementary Level

Prehistoric Timeline

Objective: Students will demonstrate an un-

derstanding of the long and ancient tradition of

visual art in the human experience by researching

and creating a Timeline that documents visual

arts prehistory and that ends with the introduc-

tion of the first codified written language.

State Core Links: From the 5th grade rainbow

chart use the orange column, Research/Create,

Study, explore, seek, be creative, imagine and

produce.

Materials: Lots of research materials, art sup-

plies to reproduce the preliterate images of our

ancestors.

Sources: Prehistoric Art: the symbolic Journey of

Humankind, by Randall White; The Cambridge

Illustrated History of Prehistoric Art, by Paul G.

Bahn; Prehistoric Art and Civilization, by Denis

Vialou; The Cave Painters: Probing the Mysteries

of the Worlds First Artists, by Gregory Curtis.

Activity: Students need to be introduced to the

long and glorious prehistory tradition in the arts.

Since it is prehistoric, it is only tangently covered

in a history curriculum. Students should organize

in groups based on the medium (cave paintings,

sculpture, and carvings, and pottery) and the time

period and culture. The body of information is

huge and most young students and their schools

do not have access to the full range of informa-

tion. This problem is exacerbated by the ongo-

ing nature of the research into the archeological

record. I was taught as a graduate student in Art

History that the cave paintings at Lascoux and

Altimira were the oldest and that the oldest sculp-

ture was the Venus of Willendorf. Subsequent

finds have made my education out dated and

inaccurate. Learning is a life-long endeavor.

To compensate for the abbreviated nature of the

time line we dont try to hit everything out there,

just a few of the high points. In my class we di-

vide up geographically. Africa, Europe, Asia (India

and China/Japan/Korea), Americas, and Austra-

lia/Oceania are the basic areas. We can divide

each area into smaller areas like North and South

America, Northern and Southern Africa, Mediter-

ranean and Northern Europe, Asia Minor, Eastern

and Western Asia, and all of Southeast Asia in-

cluding the Indonesian archipelago. Groups of 4

to 6 students seem optimal with my classes of 45

or so students 4 times a day. No shortage of bod-

ies here.

An introductory lesson at about third grade on

the nature of a timeline and the chronological

sequence of dates including things like BC and

AD and BCE and CE and why this Christmas will

be the 2009th one, theoretically, is a good way to

start this lesson. Time sequence and chronology

are a little evasive to most third graders but you

can get their attention by explaining that this is

the year 2009 because it is the 2009th Christmas.

A little discussion on the nature of Calendar is

appropriate and how dates get larger as they get

older after the Christian Era and that there are

other calendars used around the world like the

Hebrew, the Chinese, and the Arabic calendars.

Some mention of the Gregorian and Julian Calen-

dars might also be a good idea. The specifics of

How to Teach About

Prehistoric Art

40

dating are not the important thing in this lesson

as the accuracy of most dates is in some doubt.

The idea of pushing back the horizon of the art

world is the agenda.

Try starting with the oldest art your research can

discover and move forward to about 5000 years

ago when the earliest forms of written language

that we know of were introduced. Of course the

timeline doesnt end there, but that becomes a

historical lesson. This is a prehistory lesson. Use

the Internet. What a great library. We have sever-

al terminals in our art room and they are in nearly

constant use on one project or another. I refer to

my laptop as my portable library. The kids get it.

Look for images of ancient art from all of these

cultural and geographic areas because we want to

make our own version of these images. The best

way to actually see an image of anything is to try

to duplicate it in some art medium. We are in the

process of building this timeline but it will take

most of the school year, and we will rotate the

project between all the age groups at our school.

The bulk of the work will be done by 4th, 5th,

and 6th graders, but others will help. When the

images are ready we will write a short didactic

statement to be displayed with the images. The

statement should include approximate dates, lo-

cations, when discovered by whom, a short writ-

ten description of medium and proximity of the

work, and what it might actually look like today.

You may want to include some of the scientific

speculation as to the purpose and meaning of

the images. When this is completed, the images

should be prominently displayed in the class-

room, adding new work as it is finished with the

appropriate dates and in the appropriate position

relative to the other works.

Variations: Try music, dance, and drama time-

line. Try geographically and culturally specific

timelines. Try medium specific timelines (paint-

ing, sculpture, pottery).

Extensions: A wonderful way to extend this

lesson is to have students research and recreate

three-dimensional sculpture and artifacts, includ-

ing pottery, for the prehistoric record. There is

a wealth of artifacts from all over the world. It

might be interesting to see when pre-history

started in different places. Prehistoric means,

Before there was a written record, not before

existence. For example: There is no written lan-

guage in Hawaii. The Hawaiians occupied the is-

lands about 300 AD. The first European to arrive

in Hawaii was James Cook and his expedition on

Feb. 14, 1778. That means for about 1500 years,

Hawaii was a prehistoric culture.

These are the kind of illustratons we use in the

Prehistoric Art Timeline.

by Savannah, 5th grade

by Paige, 5th grade

41

When to Start Teaching Art

WHEN TO TEACH ART:

I have heard it said by skilled and dedicated

educators that art is a thing that cannot be taught

because it is a gift that you are either born with

or not. I believe that they mean that children

are hardwired to engage in personal expression

through body language (dance), sounds (music),

acting out (drama) and scribbling on the bath-

room floor with a red marker (visual art). It is

not that this cannot be taught; it is that the need

to express ourselves this way is already in place.

It is a biological imperative that cannot be taught

because it is already there. It can be untaught,

squelched, and degenerated, but it is difficult to

eradicate. There is always hiding deep within

us THE NEED. It is skill, poignancy, astuteness,

clarity, creative invention, technique, apprecia-

tion, observation, and inclusiveness in the arts

that can and need to be taught. Let us not forget

that TEACHING and LEARNING are not the same

things.

As a veteran of the Elementary Educational

process, I have observed that at about the same

time a childs brain is through growing (not to

be confused with learning or developing), about

9 years old, the childs focus in life moves from

the internal locus to the external locus. That is,

they become more stimulated and motivated by

social awareness and inhibited by social criticism.

Because there is no more brain to be grown, it is

the social animal that rears its beautiful head. If

at this transition in a childs life, the child is ridi-

culed or strongly criticized about his or her art,

the child will close down and frequently never

pick up the gauntlet again. In my workshops with

Elementary teachers I have heard this story many

times by the teachers themselves. Many actually

remember the name of the person who embar-

rassed or criticized them. It is frequently a third

or fourth grade story. They then determined that

they did not possess the gift in art. If we can get

to the students before this crisis in their lives, we

can arm them to persevere through the critical

time and not abandon their passion for artistic

communication.

Here are three strategies to help students with-

stand the negative external locus:

1. If someone says to you about your drawing or

painting, That doesnt look like a horse, then an-

swer, Horse? You got what I was trying to say. I

was trying to say horse with this picture, and you

got it so that makes me a successful artist. Thank

you very much.

2. If someone says about your painting or sculp-

ture, That doesnt look like a horse, then an-

swer, Horse? You thought I found a dead horse

on the road on the way to school and skinned it

and glued it to the paper? No, no, no! This is just

lines, shapes, values, colors, and textures that are